Venus, Earth's twin sister

Highlights

- Venus hosts brutal conditions today, but the planet may have once been more hospitable to life.

- The surface of Venus features searing temperatures and crushing pressures.

- Understanding the history of Venus could help reveal how common planets like Earth are.

What is Venus like?

Standing on the surface of Venus would be worse than standing inside a literal oven. With average surface temperatures of 470 degrees Celsius (878 degrees Fahrenheit) — hot enough to melt lead — Venus has the hottest surface of any planet in the Solar System. And beyond the sweltering heat, Venus has an atmosphere so dense that the pressure on its surface would be strong enough to crumple a nuclear submarine. Above the surface, clouds of sulfuric acid hang overhead.

Why explore Venus?

We explore Venus to search for life and better understand how hospitable planets evolve. The intense conditions on Venus might sound inhabitable, but it's possible that microbes might still live within its atmosphere today. It's also possible that life thrived on Venus a long time ago. There is evidence that water, which is essential to life as we know it, may have existed in vast oceans on the planet's surface. But whether or not Venus hosts life today or had it billions of years ago all depends on the planet's history, and how it transitioned into its current state.

By studying Venus, we can learn how Earth-like planets evolve and what shapes planets throughout the galaxy into temperate, lush worlds instead of sweltering hothouses. Venus also helps scientists model Earth’s climate, and may serve as a cautionary tale on how dramatically a planet’s climate can change.

How to spot Venus

Venus is typically the brightest object in the night sky after the Moon and the Sun. You can spot planets like Venus with a simple trick: while stars twinkle, planets usually don’t. That means if you see a bright, steady, unmoving light in the night sky, it might be one of the Solar System’s more visible planets — probably Venus or Jupiter, if it looks brighter than every star in the sky. If a few stars do outshine your planet, then it’s probably Saturn or Mars instead. Venus is also called the "morning star" and "evening star" because it appears relatively close to the Sun in the sky, shortly after sunset or before sunrise.

Since Venus is the brightest planet as seen from Earth's surface, it has been observed and incorporated into human culture since ancient times. Its English name comes the Roman goddess of love, named Aphrodite to the Greeks and Ishtar to the Babylonians.

Venus Facts

Surface temperature: 440°C (820°F) to 480°C (900°F)

Average distance from Sun: 108 million kilometers (67 million miles), or 38% closer to the Sun than Earth

Diameter: 12,104 kilometers (7,521 miles), just 5% smaller than Earth

Volume: 928 billion km3 (223 billion mi3), Venus could fit inside Earth about 1.1 times

Gravity: 8.9 m/s², or 90% that of Earth’s

Solar day: 117 Earth days

Solar year: 225 Earth days

Atmosphere: 96% carbon dioxide, 3% nitrogen, 1% other gases

How we explore Venus

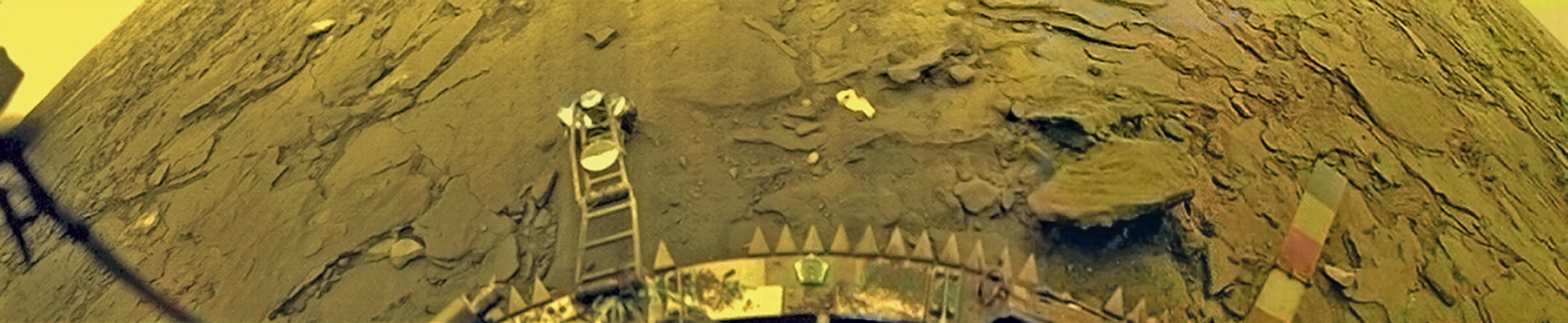

Venus was the first planet to be visited by a spacecraft. In 1962, NASA’s Mariner 2 flew by the planet and discovered it was a hot world without a strong magnetic field. The Soviet Union later overtook the United States as the world leader in early Venus exploration, sending multiple atmospheric probes and nearly a dozen landers to the planet. To this day, the Soviet Union remains the only nation to have landed spacecraft on the Venusian surface and transmitted both data and images back to Earth.

Because of its thick clouds, it is impossible to see Venus’ surface features in visible light. Instead, NASA’s Magellan spacecraft, launched in 1990, used radar to map Venus’ surface at the highest resolution to date. Magellan revealed that all of the planet’s impact craters were formed within the last several hundred million years. This implies that Venus’ surface was completely reshaped by a worldwide volcanic event in its recent geologic past, but exactly what happened is still up for debate.

In 2005, The European Space Agency launched the Venus Express orbiter. By observing hotspots on the surface and changing sulfur dioxide levels in the atmosphere, the spacecraft collected the best evidence yet of active volcanism on Venus. Venus Express also discovered granite-like rocks across the planet that would likely require abundant liquid water to form, further hinting toward the planet having once had oceans.

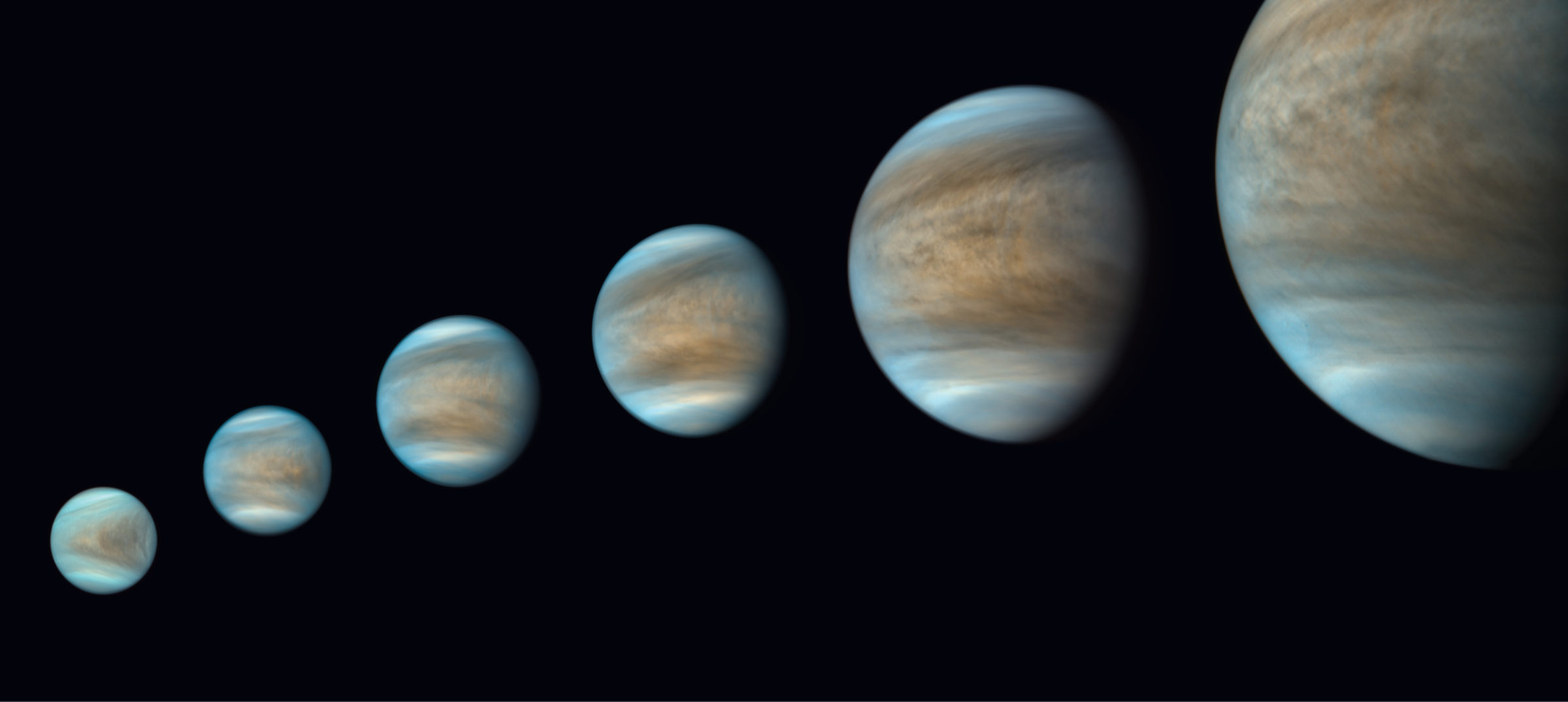

Japan’s Akatsuki spacecraft is the only probe currently orbiting Venus. It studies Venus’ atmosphere and has made several discoveries about the planet's cloud physics and weather. The mission's images are often processed to create beautiful enhanced-color pictures of the planet.

Upcoming Venus missions

The India Space Research Organisation's Venus Orbiter Mission (VOM) is the next spacecraft slated for Venus, aiming to launch in 2028. VOM will study the Venusian surface and investigate its atmosphere makeup.

Then, around 2031, several missions will all launch to Venus around the same time: NASA's DAVINCI and VERITAS missions, as well as the European Space Agency's Envision mission. DAVINCI will orbit Venus and send a probe to descend through the planet's atmosphere, while Envision and VERITAS will solely be orbiters. Together, these missions will help us understand the history of Venus — especially its water — and whether it could potentially have hosted life in the past, or even today.

Acknowledgements: This page was initially written by Jatan Mehta in 2020. It has been updated by Asa Stahl.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth