Asteroids, comets, and other small worlds

Highlights

- Most asteroids and comets are leftovers from the birth of the Solar System. They provide a window into how the planets — including Earth — formed and evolved.

- Asteroids and comets can contain water and organic molecules. By impacting the early Earth, some may have helped deliver the ingredients for life to our planet.

- Large asteroids or comets can impact Earth and cause massive damage, so it’s important we find any that might hit us in the future.

Why does the Solar System have asteroids and comets?

Four and a half billion years ago, a giant cloud of gas and dust collapsed to form the Sun. Afterward, some material was left over in a disk that swirled around our star and came together into rocks, boulders, and eventually planets and moons. The bits of rock and ice that survived all this — or that were born out of collisions between other Solar System bodies — became the asteroids, comets, and other small worlds that still orbit the Sun to this day.

What makes an asteroid different from a comet?

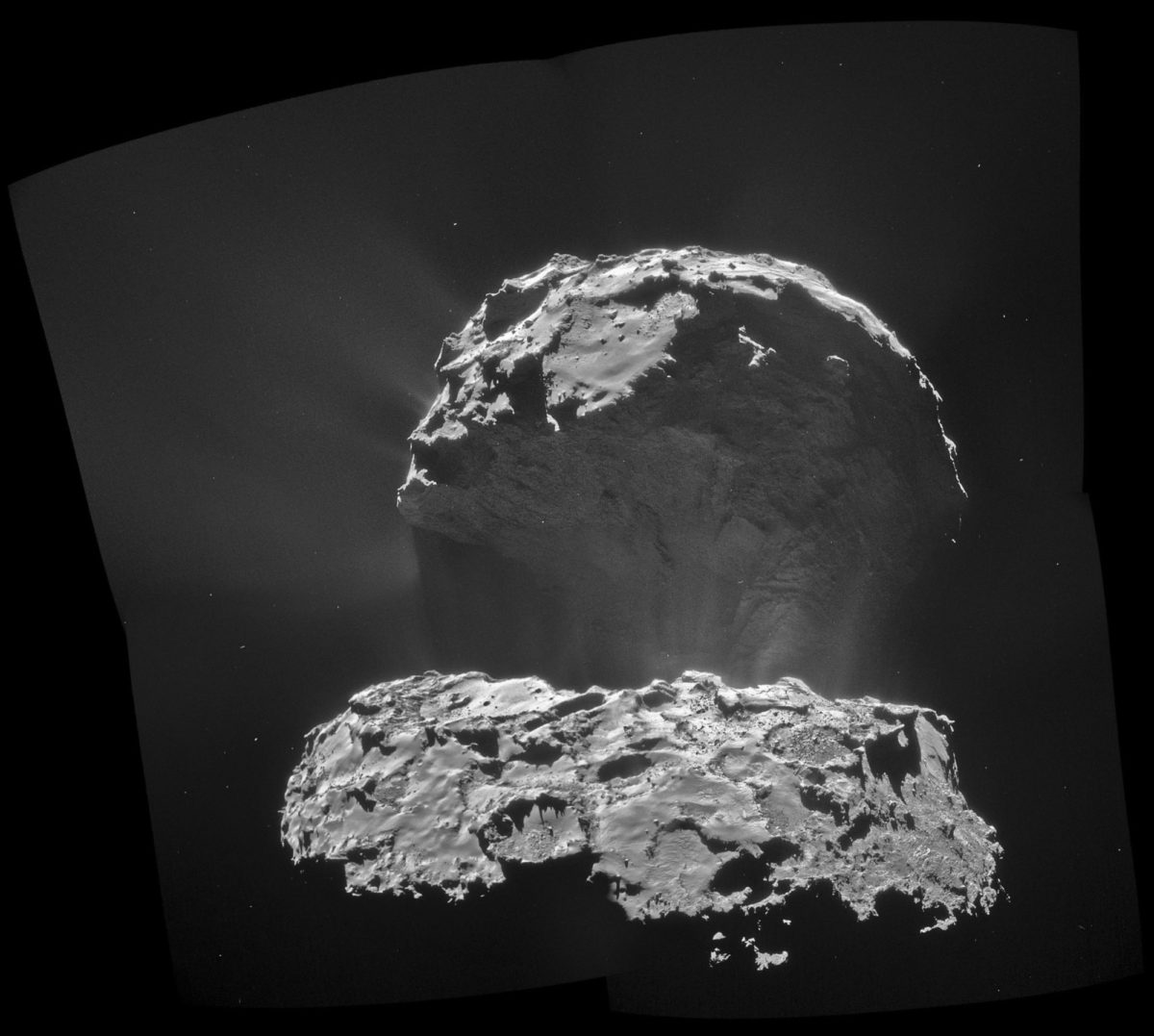

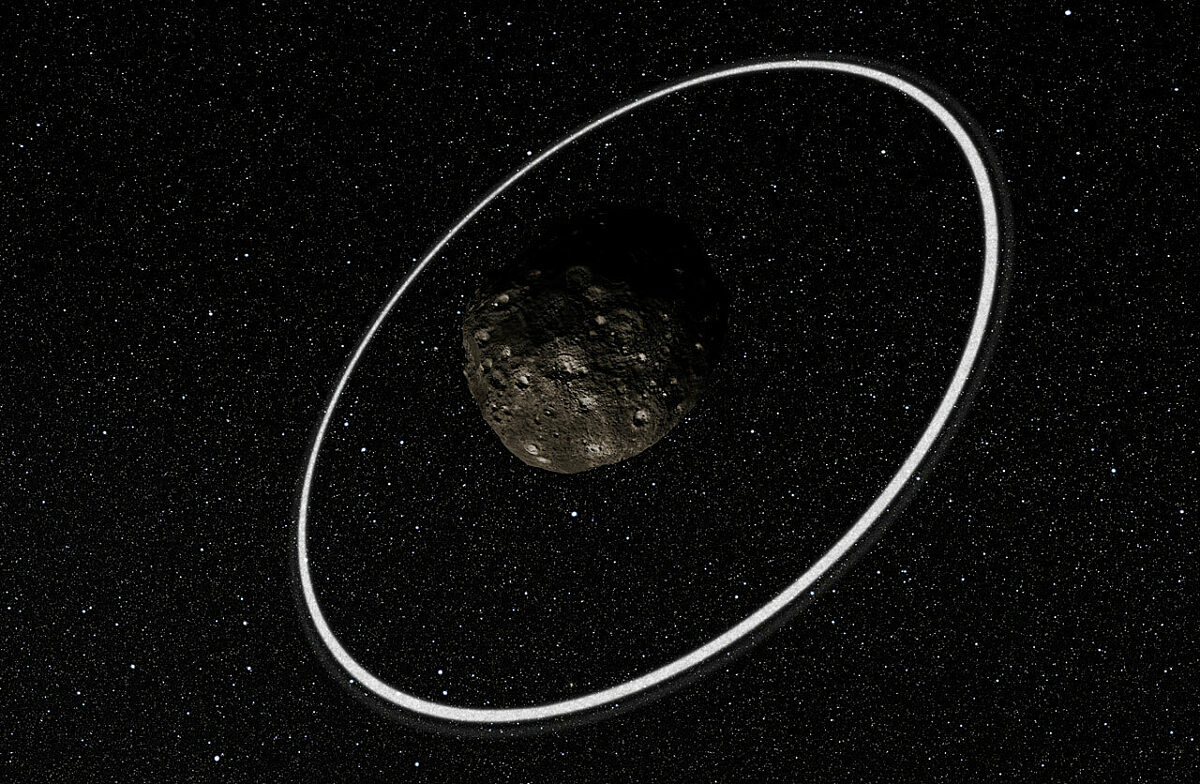

An asteroid is a small rocky object, usually irregularly shaped, that orbits the Sun. Comets are similar to asteroids, but more icy because they formed farther from the Sun and continue to spend most of their time there. Comets pass most of their orbits beyond Jupiter and Neptune. When they do come closer to the Sun, comets warm up and throw off gas and dust, giving them tails.

By contrast, most asteroids are located in the main asteroid belt between the orbit of Mars and the orbit of Jupiter. Some asteroids and comets stray close enough to Earth’s orbit — within 50 million kilometers (30 million miles) — that they are labeled “near-Earth objects” and studied to find out whether they might eventually pose a risk of hitting our planet.

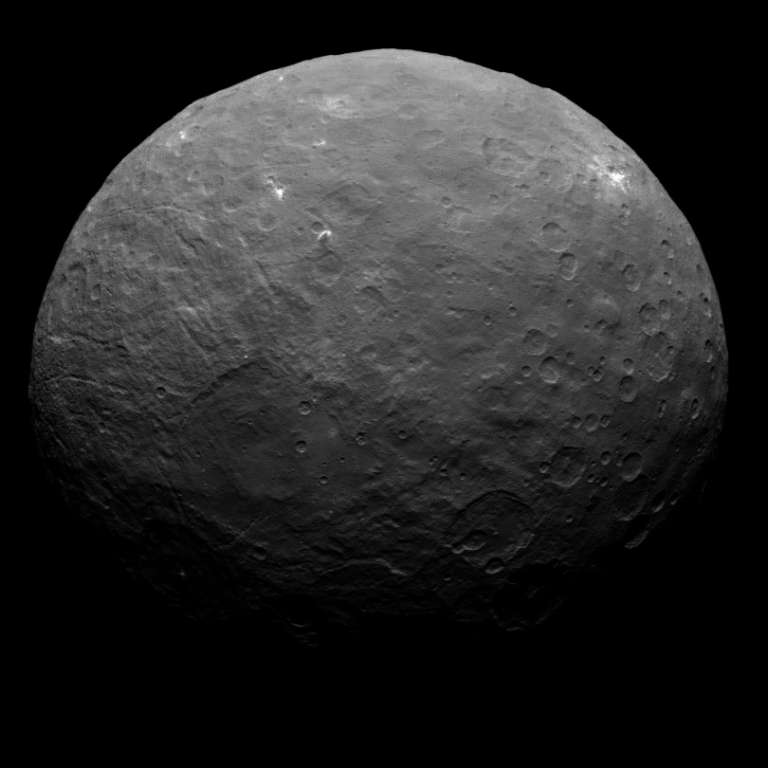

In general, asteroids range between about one meter and 1,000 kilometers in size. The largest asteroid is Ceres, named after the Greek goddess of agriculture and grain. At 952 kilometers (592 miles) wide, Ceres is massive enough that gravity has molded it into a spherical shape. This makes Ceres not just an asteroid, but also technically a dwarf planet, like Pluto. On the other end of the size spectrum are meteoroids, objects similar to asteroids but smaller than one meter. Extremely tiny meteoroids, with masses less than 1 gram or so, are called micrometeoroids or simply “space dust”.

What about meteors and meteorites?

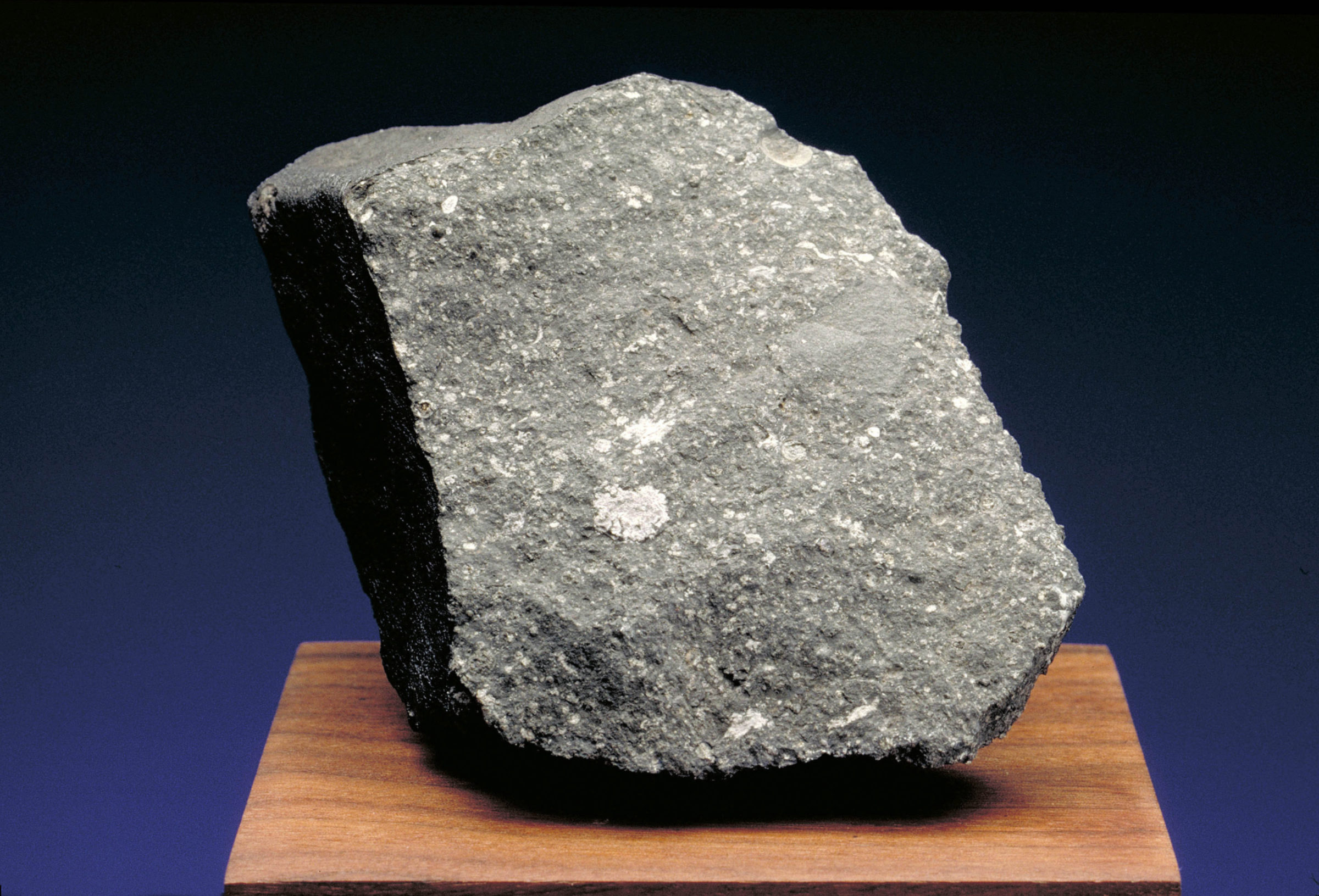

A meteor is the streak of light that occurs when an object (like an asteroid or meteoroid) hits Earth’s atmosphere at high speed, heats up, and glows. If part of a meteoroid, asteroid, or comet makes it to Earth’s surface, it is called a meteorite.

Will a large asteroid ever hit Earth?

Maybe. But as far as we know, it won’t be anytime soon. The closest call heading our way is the asteroid Apophis, which will pass so near to Earth in 2029 that it will travel below the orbits of geosynchronous satellites. There are over 30,000 other known asteroids that come close enough to Earth’s orbit to be considered near-Earth asteroids, and of these, about 2,000 are “potentially hazardous objects”. This means they are bigger than 140 meters (460 feet) and projected to one day cross Earth’s orbit.

If one of these asteroids impacted our planet, it could cause major regional — if not global — damage. To prevent this, we search for objects that might impact Earth, characterize asteroid orbits, and devise strategies to deflect them.

Once an asteroid is found, amateur and professional astronomers all around the world track its location over time. They submit their observations to the Minor Planet Center, and then two groups of scientists, one at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in the U.S. and the other in Italy, compute orbits from the data. They use their models to run simulations predicting whether the asteroid will one day hit Earth.

Can you see asteroids and comets from Earth?

Most asteroids are too small and faint to be visible to the naked eye, but the biggest, like Vesta and Ceres, can sometimes be spotted. When Apophis almost hits Earth in 2029, it will be briefly visible to the naked eye from darker skies.

Since comets tend to spend most of their time in the outer Solar System, they are rarely bright enough to be visible from Earth to the unaided eye. But every several years or so, a comet will swing near enough to the Sun or Earth — and throw off enough material as it passes by — that it becomes so bright in the night sky that it is apparent to the naked eye.

You can also see comets indirectly, by the trail of dust they leave behind as they pass through the inner Solar System. If Earth orbits through one of these trails, the particles slam into our atmosphere and create a meteor shower. The annual Perseid meteor shower, for example, is caused by debris from comet Swift-Tuttle. This comet last passed through the inner Solar System in 1992 and won't return for 133 years.

What we can learn from asteroids and comets

The Solar System’s rocky planets have not stayed the same since they formed. Their surfaces have been dramatically reshaped by processes like volcanism, erosion, and tectonics. Asteroids and comets, by contrast, can offer pristine records of the early Solar System. Their orbits and compositions preserve information on how the planets formed, how the dynamics of the Solar System have changed over time, and how certain substances — like water and organic molecules essential to life as we know it — were distributed among the planets.

It’s possible that Earth was born relatively dry, and that asteroid impacts delivered most of the water that would eventually make life possible on our planet. Or, Earth may have started off wetter, with asteroids playing a smaller role. Figuring out which of these situations is closer to the truth will not only help us answer one of humanity’s most fundamental questions — “How did we get here?” — but also provide insight into how common the conditions for life might be on planets around other stars. This is an active field of astrophysics research, and some of the most important discoveries driving it forward come from space missions that visit asteroids and comets.

We also study asteroids to prevent Earth from being hit by one. Predicting asteroid orbits requires a detailed understanding of all the forces affecting them, even very small ones, which scientists continue to research. Our ability to deflect any incoming asteroids also depends on astronomers being able to tell what an asteroid is made of from afar. Some can be more like loose piles of rubble, while others are more like solid rocks. Knowing which is coming toward Earth could make a big difference to any plans to head off danger, and that means having a strong grasp of the different kinds of asteroids, what they’re made of, and why.

Meet the Asteroids (5 Space Rocks to Watch) In this video, get to know five of the most important asteroids out there. Find out what they can teach us about our place in the universe, and whether you need to worry about an impact.

Exploring asteroids

Many asteroids are near enough for scientists to image with Earth-based radar, which helps trace their shapes. But to get a complete picture of what asteroids are, what information they carry about the Solar System’s past, and what risk they might pose to Earth, it’s necessary to send spacecraft to study asteroids up close.

The first spacecraft to ever fly by an asteroid was Galileo, NASA’s Jupiter-bound mission that came within 1,600 kilometers of Gaspra in 1991. Galileo’s pictures revealed an irregularly shaped world formed out of a relatively recent collision. Two years later, Galileo made a close approach to another main belt asteroid, Ida, which turned out to have a tiny moon now named Dactyl. The next major milestones in asteroid exploration came with NASA’s NEAR Shoemaker probe, which entered orbit around near-Earth asteroid Eros in 2000 and, a year later, touched down on its surface — both firsts for any spacecraft.

In 2010, the Hayabusa spacecraft, developed by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), became the first mission to successfully bring back samples from an asteroid. Water found in material from the asteroid, called Itokawa, was remarkably similar to that of Earth’s oceans. This discovery supported the possibility that much of Earth’s water could have come from similar asteroids.

A year later, NASA’s Dawn spacecraft arrived at the asteroid Vesta, one of the largest asteroids in the Solar System. Vesta is a confirmed “planetesimal”, meaning it is a direct leftover of the formation of the planets. After orbiting the asteroid for a little over a year, Dawn traveled on to Ceres, which it studied until running out of fuel in 2018 (the spacecraft remains in orbit around Ceres to this day).

Dawn found an unexpectedly high amount of water-bearing minerals on Vesta’s surface and abundant water ice and organics on Ceres. These chemicals would not have survived if either asteroid formed where they orbit now — in the asteroid belt — which could mean that both Ceres and Vesta formed farther away from the Sun and later drifted inward. If true, understanding that migration could provide hints into how water and organics ended up on Earth.

More recently, the Japanese Hayabusa2 mission brought back samples of asteroid Ryugu to Earth, NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) successfully changed the orbit of asteroid Dimorphos by crashing into it, and NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft safely delivered samples from the asteroid Bennu before continuing on to a future rendezvous with Apophis.

Finally, NASA’s Lucy mission is currently on a tour of eight different asteroids, while the agency’s Psyche spacecraft is headed to just one special target. Lucy will eventually arrive near Jupiter to study the gas giant’s Trojan asteroids, which have never before been visited by a spacecraft. These small bodies travel in groups ahead of and behind Jupiter in its orbit around the Sun. They are thought to offer especially pristine remnants of the Solar System’s formation. Psyche’s destination, although in the main asteroid belt, will present another first: it will be the first metallic asteroid ever visited by a spacecraft. The asteroid, which is also named Psyche, is called an M-type asteroid because it shows strong signs of being rich in metals like iron and nickel. These metals are the principal components of planetary cores, so studying Psyche will help scientists gain insight into how the interiors of planets form and develop.

Exploring comets

In 1985, NASA’s International Cometary Explorer, ICE, became the first spacecraft to fly past a comet. It traveled within 7,900 kilometers (4,900 miles) of the nucleus of comet Giacobini-Zinner. Although the spacecraft had no cameras, ICE helped confirm the theory that comets have tails because they are throwing off dust and gas.

A year later, ICE joined a fleet of international spacecraft observing Halley’s comet. Europe’s Giotto spacecraft flew through the comet’s tail and captured images of its nucleus, revealing a potato-shaped world 15 kilometers (9 miles) long. It tumbled through space spewing jets of dust, gas, and ice.

In 2004, the European Space Agency's Rosetta mission launched toward comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. It orbited and dropped a lander on the comet as it flew through the inner Solar System. Rosetta ultimately found comet 67P’s water to be different from water on Earth, hinting that comets like it likely did not deliver much water to our planet.

The first samples ever taken from a comet were brought back to Earth in 2006 by NASA’s Stardust probe, which visited the comet Wild 2 in 2004. Scientists found a wide array of organic compounds in material from Wild 2, including amino acids.

Every previous mission to a comet has targeted what are called “short-period comets,” meaning their orbits around the Sun take less than about 200 years. ESA’s Comet Interceptor mission, planned for launch in 2029, hopes to take the first close look at a long-period comet. Such comets ought to provide more pristine records of the early Solar System since they spend less time near the Sun, having their surfaces bombarded by heat and radiation. But by the time astronomers discover them, long-period comets tend to be too far along in their journey through the inner Solar System for a mission to be charted their way. This is why Comet Interceptor will stay in a holding orbit and wait for astronomers to discover an interesting long-period comet on its way toward the Sun. Only then will the mission head off, splitting into three separate spacecraft on its way to the comet.

Asteroids, comets, and The Planetary Society

Space missions to asteroids and comets don’t just happen — they require years of smart policy and stable funding. Visit our space policy program page to learn more about how we support missions, influence legislation, and empower our members to become effective space advocates.

The Planetary Society also works to prevent Earth from being struck by asteroids and comets. Find out more about how we organize the space community around planetary defense, support relevant technology, and help observers find, track, and characterize near-Earth asteroids.

Action Center

Whether it's advocating, teaching, inspiring, or learning, you can do something for space, right now. Let's get to work.

Acknowledgements: This page was initially written by Jatan Mehta in 2020. It was revised by Asa Stahl in May 2024.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth