The European Space Agency (ESA)

What does ESA do?

ESA brings European countries together to explore and use space peacefully for the benefit of the wider world. The agency performs scientific research, operates satellites, and organizes space projects like probes, rockets, and human spaceflight.

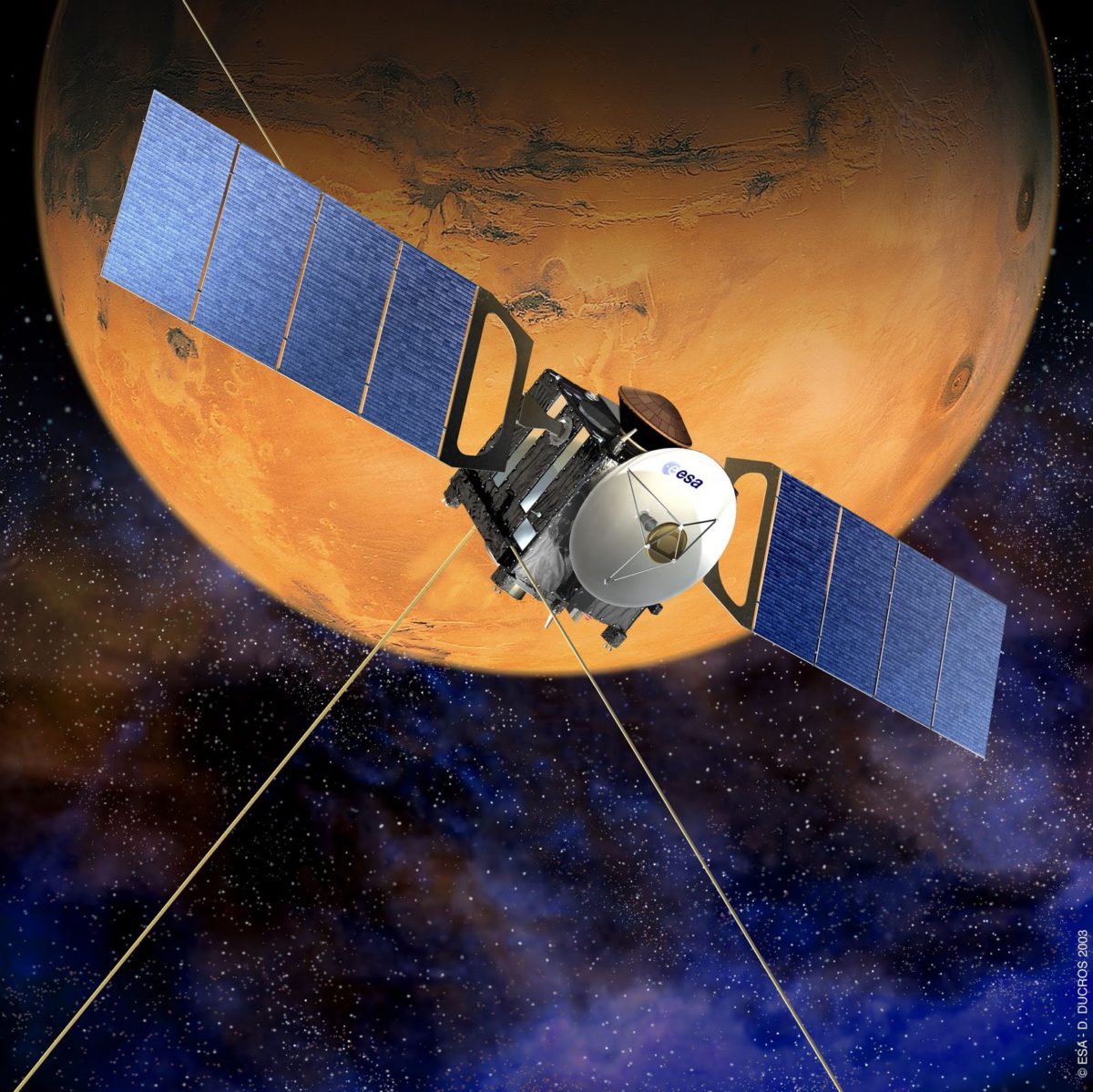

ESA launches missions dedicated to studying our planet and exploring the Universe beyond it. The agency has an orbiter around Mars as well as probes on their way to Mercury and Jupiter. Its space telescopes investigate the history of the Universe and our galaxy, its satellites monitor Earth’s geology and ecosystems, and its astronauts fly aboard the International Space Station (ISS), which ESA also helped build.

In the near future, ESA will soft-land its first spacecraft on the Moon as part of its Argonaut program. The agency will work to better understand Mars’ past — and perhaps look for signs of past life — with its Rosalind Franklin rover. In 2026, it will launch the PLATO mission to discover new worlds around other stars.

Beyond exploration, ESA works to build Europe’s capabilities in space through basic research and by supporting private industry. ESA contracts enable powerful launch vehicles like Ariane 6 and Vega-C, and its engineers develop new satellite communication and navigation technologies.

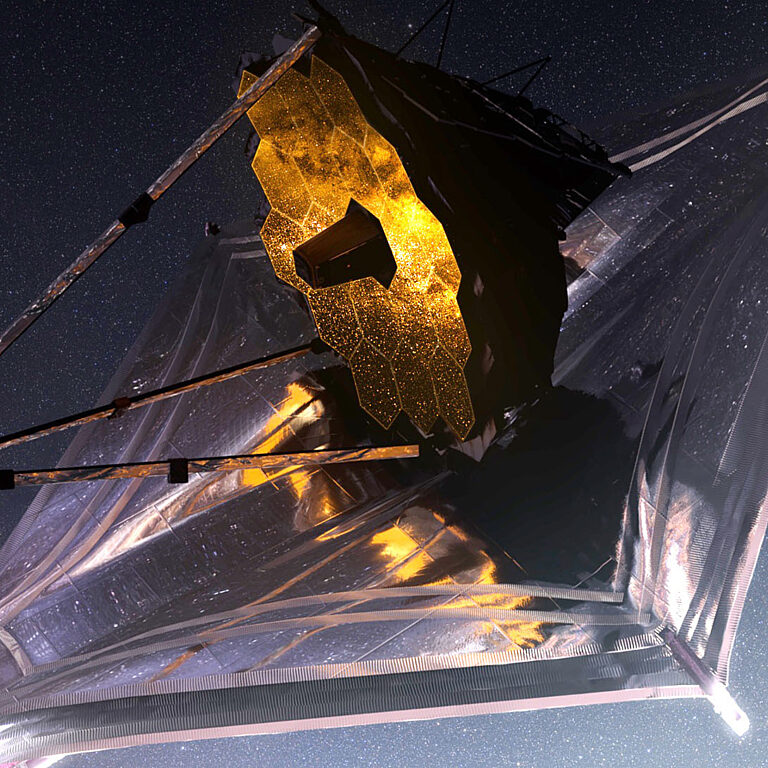

ESA collaborates with other space agencies like NASA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). It jointly operates the BepiColombo Mercury mission with JAXA, works with NASA on the Hubble Space Telescope, and collaborates with both NASA and the Canadian Space Agency on the James Webb Space Telescope. As NASA’s largest international partner on the Artemis program, ESA provides the Orion crew capsule’s service module and major contributions to the Gateway lunar space station. ESA also used to collaborate with Roscosmos, but that has mostly been suspended since the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

What has ESA accomplished?

ESA has:

- Landed the first-ever probe on a comet as part of the Rosetta mission

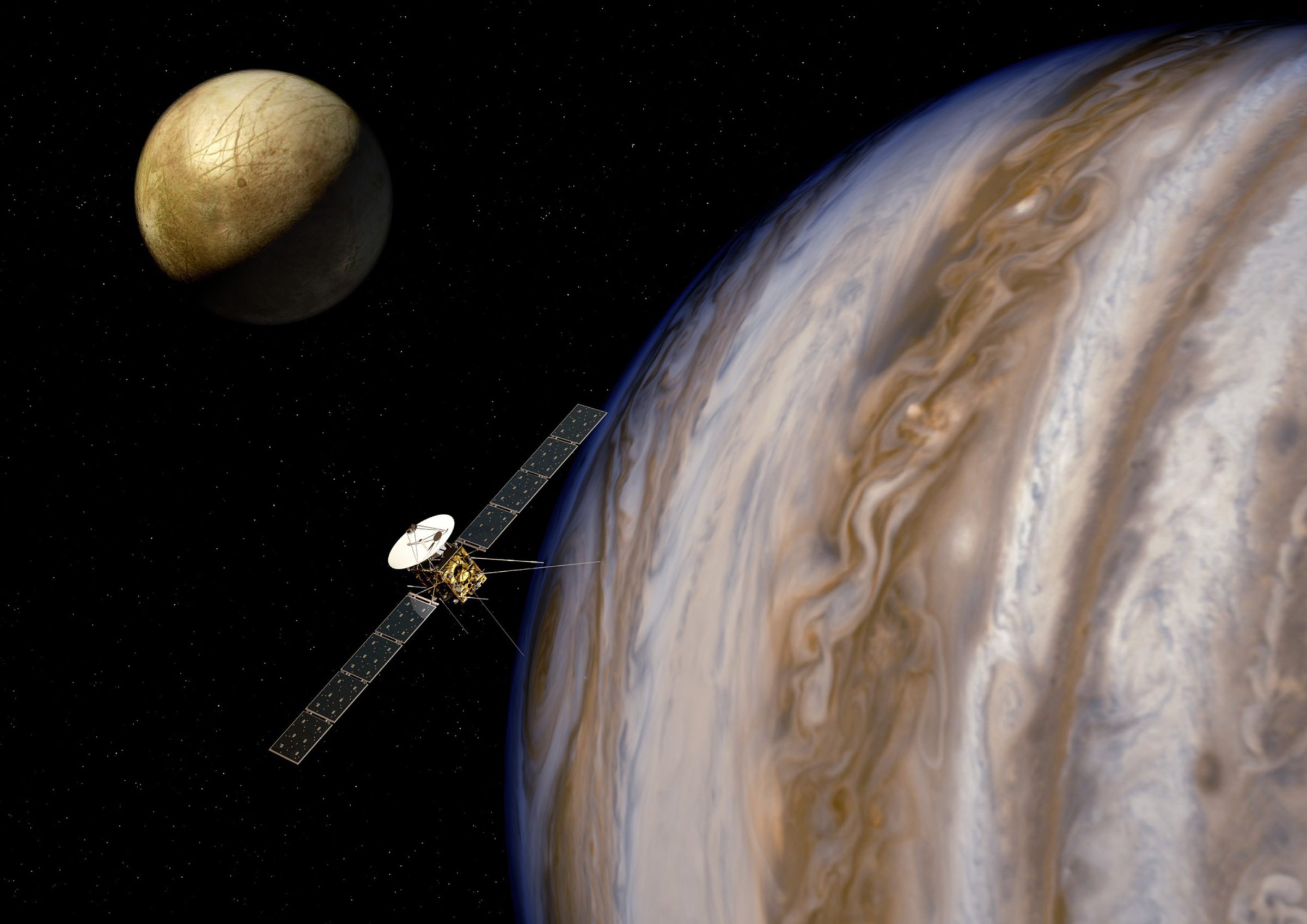

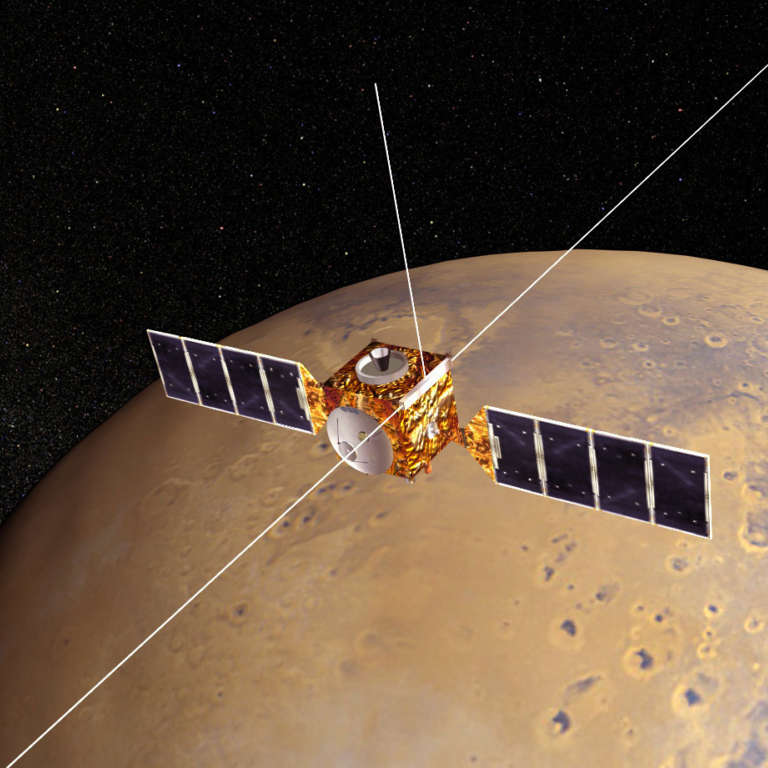

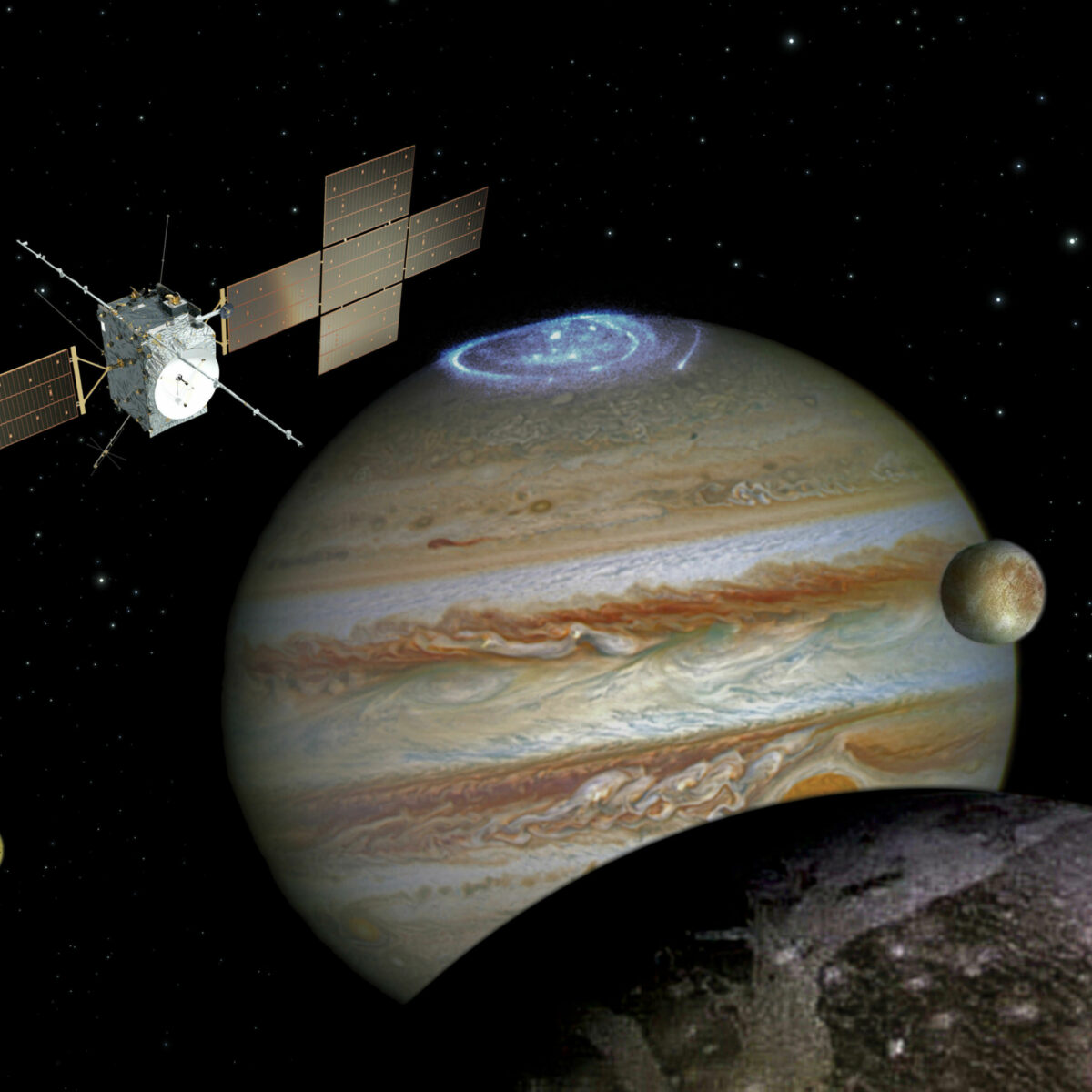

- Sent missions to Mercury, Venus, Mars, the Jupiter system, the Sun, and the Moon

- Landed on a potentially habitable moon of Saturn, in collaboration with NASA

- Built the Cupola and Columbus modules of the International Space Station

- Flown multiple cargo missions to the ISS

- Launched space telescopes that have opened new views into the Universe, and collaborated with NASA on observatories like the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope

- Become the first ever to study a comet up close with its Giotto spacecraft

- Launched multiple orbiters to uncover Mars’ past, as well as over 50 satellites to observe the Earth and its climate

- Trained and flown astronauts on NASA’s Space Shuttle

How does ESA work?

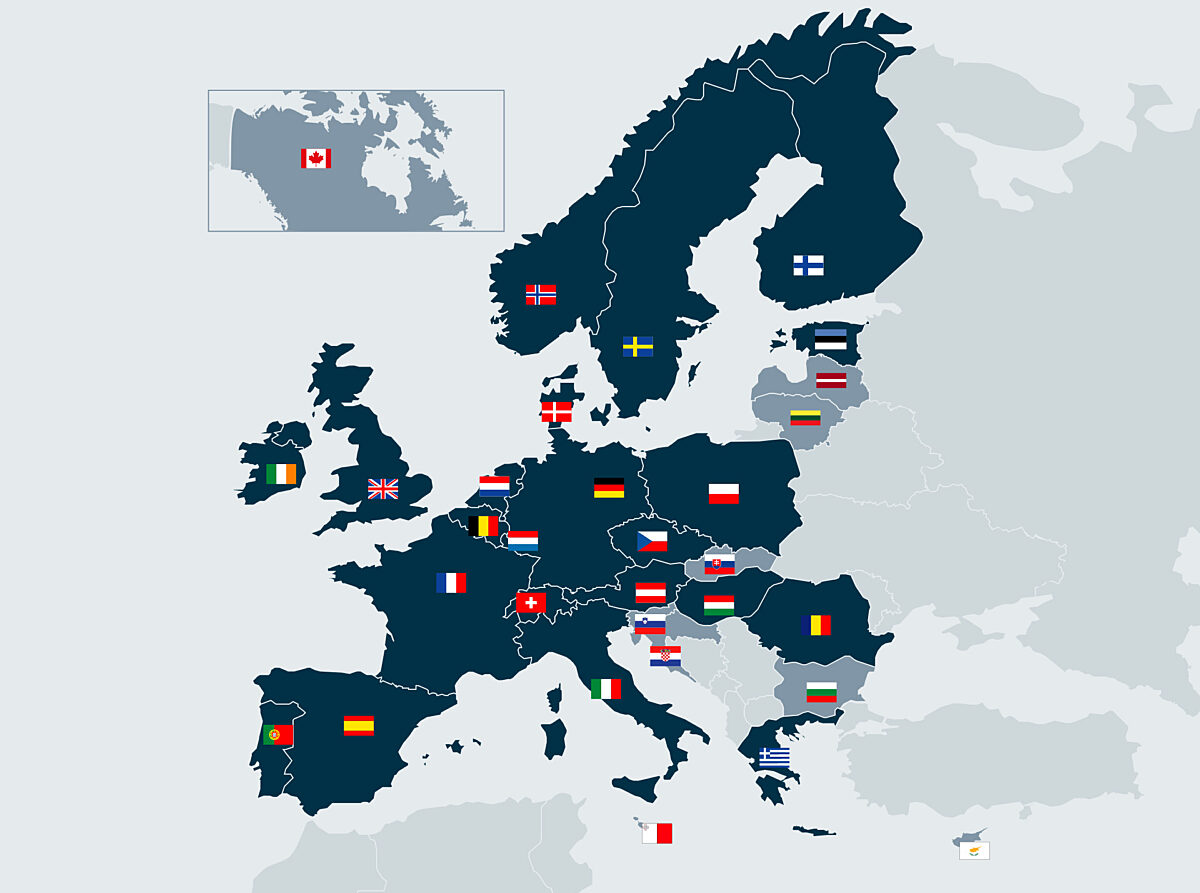

ESA is a democratic collaboration between many different countries. Currently, ESA hosts 22 members from all over Europe (plus four associate members and Canada, which is technically a “Cooperating State”). Each of these countries gets one vote on ESA’s governing Council to decide the agency’s priorities, budget, and director.

How big is ESA? ESA is the largest purely civilian space agency after NASA, in terms of resources. Its budget is about one-third that of NASA, but several times larger than the budgets of organizations like JAXA or Roscosmos.

Every ESA member has to contribute a minimum amount of money to the agency’s budget in proportion to their GDP, and members can also go beyond that level to fund particular ESA projects. Each country’s contributions guarantee ESA contracts with local companies.

ESA is not the only public space agency in Europe, but it is by far the largest. Many of ESA’s members have their own national space organizations. There’s also the European Union Agency for the Space Programme (EUSPA), the dedicated space agency of the European Union (EU). It focuses more on operations, like managing European navigation satellite systems, while ESA focuses more on space infrastructure design and development.

ESA is distinct from the EU. There are some countries that are in the EU but not in ESA, and some countries are in ESA but not the EU. The EU does provide about 20% of ESA’s budget, though, and there were once plans to make ESA an agency of the EU.

ESA’s headquarters are in Paris, France. The agency also has several other centers around Europe, as well as a launch base in French Guiana.

ESA can:

- Build and operate its own satellites

- Build its own launch vehicles

- Build human-rated spacecraft

- Provide commercial launch services

- Perform space science missions

How did ESA get started?

The European Space Agency was officially formed on May 30, 1975, when its 10 founding countries signed the ESA Convention. But its history also goes back further.

ESA was created by merging two European space organizations that were founded in the 1960s. The first, the European Launcher Development Organisation (ELDO), was a collective effort by six European countries to build a rocket capable of launching heavy satellites. The second, the European Space Research Organisation (ESRO), was focused less on launches and more on space science. It was established in part through the work of the same scientific leaders who helped found the European Organization for Nuclear Research (known as CERN), the European physics collaboration that famously discovered the Higgs Boson in 2012.

When ELDO failed to get its rocket project off the ground, its funding dried up, and ESRO and ELDO were merged to create ESA. Since then, ESA has had a long record of success in launching its own satellites, observatories, and space missions, as well as collaborating with other space agencies like NASA, Roscosmos, and JAXA.

ESA's budget by major program. Source: ESA.

The European Space Agency (ESA) is launching the EnVision spacecraft to study Venus and its past.

Mars Express was the European Space Agency’s first planetary mission when it launched in 2003.

The European Space Agency (ESA) is launching the Juice spacecraft to study Jupiter and its three largest icy moons — Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

JWST is observing galaxies that formed just after the Big Bang and determining whether planets orbiting other stars could support life.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth