Highlights

- Dragonfly is a NASA mission to Saturn’s largest moon Titan scheduled to launch in 2028.

- The spacecraft is an eight-bladed drone-like craft called a rotorcraft that will make short flights around the surface.

- Titan’s atmosphere is similar to Earth’s when life arose here 3.5 billion years ago. By studying chemicals in Titan’s atmosphere and on the surface, Dragonfly will help us understand possible starting ingredients for life on Earth and elsewhere.

Why We Need Dragonfly

Life as we know it needs three things: an energy source like sunlight, a liquid solvent like water, and organics — a wide variety of carbon-based compounds that build the proteins for life as we know it. That’s a pretty vague recipe; it’s like saying you make soup using a stove, a pot of water, and some food.

Before life arose on Earth, our atmosphere was a lot different. There was hardly any oxygen and a lot more methane. In sunlight, these molecules formed organic chemicals that rained down on our planet. We don’t know exactly what those chemicals were, but when combined with water and energy they probably formed the primordial soup from which life arose.

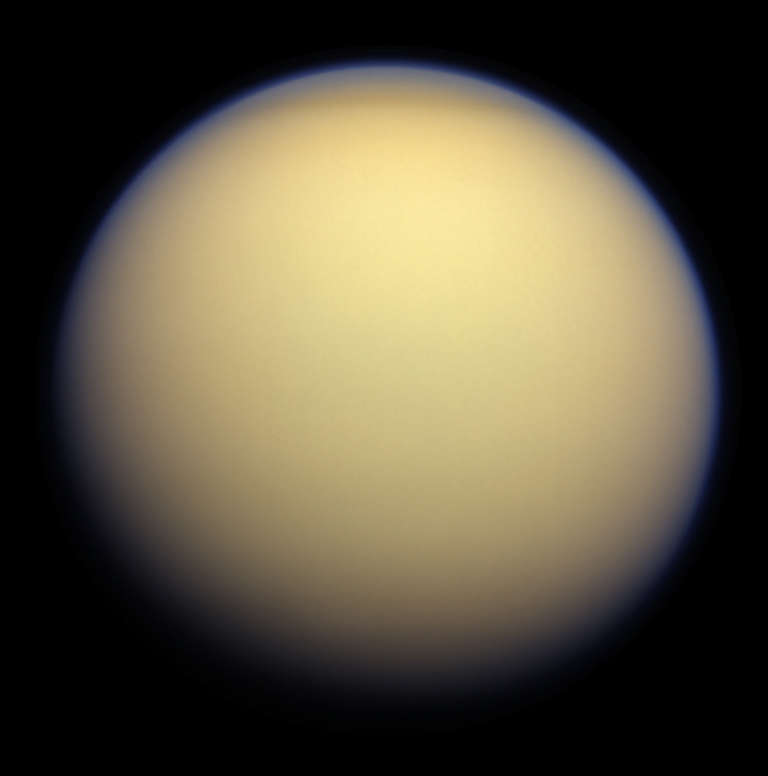

We can’t travel back in time and see exactly what happened, but fortunately, there’s a present-day location with a similar atmosphere: Saturn’s moon Titan. Like early Earth, Titan’s skies are clouded with methane that forms organic molecules — the building blocks of life as we know it. These molecules should be abundant on Titan’s surface, offering us a unique opportunity to study the possible starting ingredients for life.

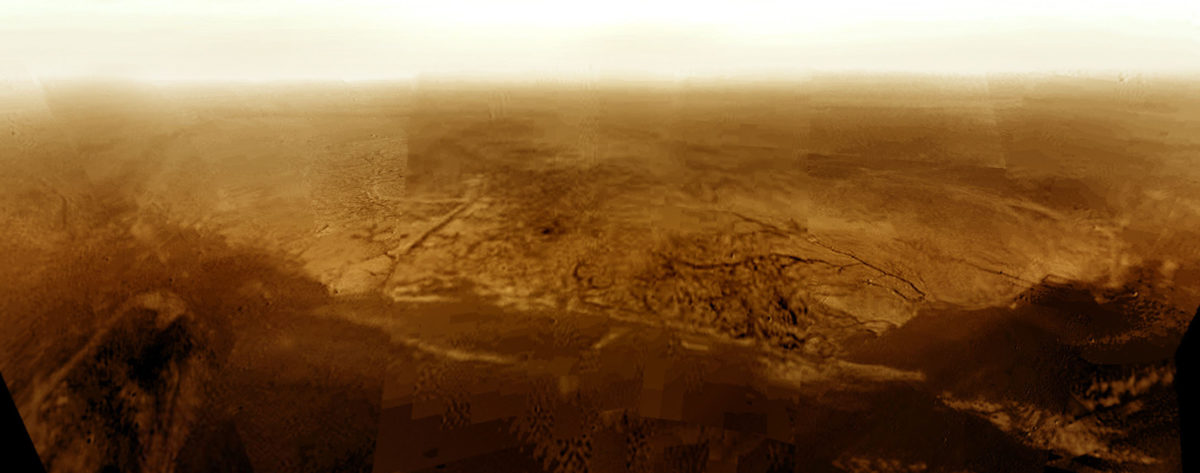

NASA’s Dragonfly spacecraft is our next step in Titan exploration. Scheduled to launch in 2028, Dragonfly builds on the legacy of NASA and the European Space Agency’s legendary Cassini-Huygens mission. Cassini orbited Saturn and buzzed the ringed planet’s moons from 2004 to 2017, while Huygens landed on Titan in 2005. Together, the spacecraft mapped the moon, studied the composition of Titan’s atmosphere, and discovered evidence for a water ocean beneath the surface.

In addition to revealing new clues about the recipe for life on Earth, Dragonfly will help us explore possibilities for decidedly un-Earth-like life. Like Earth, Titan has mountains, rocks, dunes, rivers, lakes, and seas, and a plentiful supply of organic chemicals. Unlike Earth, Titan’s mountains, rocks, and sand are made mostly of water ice, and its rivers, lakes, and seas are filled with liquid methane and ethane instead of water. Dragonfly will study this bizarro version of Earth to see what chemical processes are happening, and how that relates to both life as we know it and forms of life that might be unlike anything we’ve ever dreamed.

How does Dragonfly work?

Usually, planetary landers can only explore one small region of the worlds they visit, but Titan’s low gravity and dense atmosphere will allow Dragonfly to take flight. The spacecraft, about the size of a small car, has four arms that each hold two helicopter rotors stacked atop one another. This will allow it to make short flights around the surface. Each flight will be meticulously planned, but must happen autonomously, since the one-way light-travel time to Titan is more than an hour.

Titan’s gravity is about one-seventh that of Earth’s — a little weaker than our Moon’s gravity. With an atmosphere four times denser than Earth’s — roughly the pressure you feel a meter underwater — the conditions are prime for flight. If you strapped on a pair of wings and flapped your arms, you’d be able to fly!

Dragonfly will initially land near Titan’s equator in Shangri-La, a field of dunes that are similar to the dunes found in Namibia here on Earth. The spacecraft will also visit the Selk impact crater, where the energy of the impact may have created a temporary liquid-water lake.

Everywhere it goes, Dragonfly will study Titan’s surface, which should have collected organic chemicals raining out of the atmosphere. Mounted to each of the probe’s two sled-like rails is a drill that will grind up materials so they can be sucked into an instrument called a mass spectrometer. The mass spectrometer will be able to measure the masses of molecules in each sample, including heavier organic compounds that are the building blocks of life as we know it.

At Saturn’s distance from the Sun, sunlight is only 1% as strong as it is on Earth. Titan’s haze blocks most of the rest. Therefore, Dragonfly can’t rely on solar power — it will operate on batteries during the day and recharge at night from a nuclear power source similar to the ones used on NASA’s Curiosity and Perseverance rovers. Days and nights on Titan are each about 8 Earth days long, and Dragonfly will be able to fly once per Titan day.

Dragonfly also carries a suite of instruments that will directly analyze Titan’s atmosphere, allowing scientists to see how it changes with the days and seasons. This could help us understand how Earth’s atmosphere formed. The spacecraft will also measure any Titanquakes with a seismometer. And, of course, Dragonfly has cameras to take aerial images as it soars through Titan’s skies. These photos will help the mission team scout for Dragonfly’s next destinations, and will also give the public awe-inspiring panoramic views of this mysterious moon.

Support missions like Dragonfly

Whether it's advocating, teaching, inspiring, or learning, you can do something for space, right now. Let's get to work.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth