Chang'e-5: China's Moon sample return mission

Highlights

- China's Chang'e-5 spacecraft returned Moon samples to Earth in 2020.

- The samples are a relatively young 2 billion years old. They will help scientists understand what was happening late in the Moon’s history, as well as how Earth and the solar system evolved.

- Chang'e-5 is now on an extended mission to test technologies in an advanced lunar orbit.

Why do we need Chang'e-5?

The splotches and craters you see on the Moon are scars from the traumatic early days of our solar system. Asteroids and comets slammed into the early Earth and Moon, likely bringing here water that helped life take hold and flourish.

What happened when is still up for debate. Fortunately, scientists can piece together the Moon’s history by studying the age and composition of different lunar regions. While orbiting spacecraft can collect a wealth of valuable data, some scientific experiments can only be done on Earth with instruments that are too large and power-hungry to fly in space. Earth-based experiments can also be repeated in different labs and the samples can be stored for future generations to examine with more advanced technology.

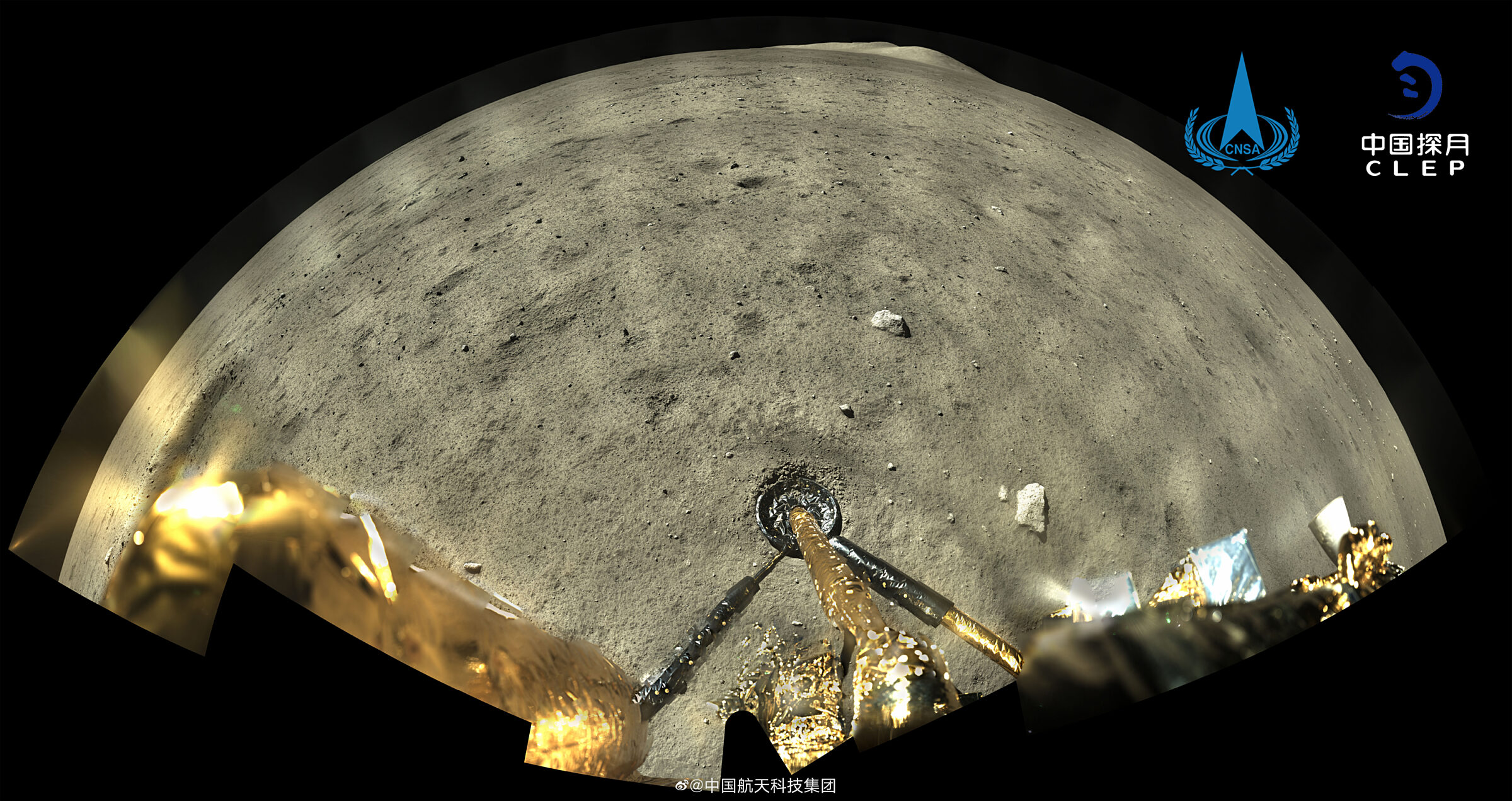

China’s Chang'e-5 (嫦娥五号) sample return mission landed in Oceanus Procellarum — the Ocean of Storms — a dark-grey region in the Moon’s northwest corner visible with the unaided eye from Earth. The specific landing site, near a 70-kilometer-wide mound named Mons Rümker, was believed to have young rocks and soil formed by a large volcanic event that covered up the underlying surface. An analysis of the samples back on Earth found they were roughly 2 billion years old — far younger than the samples NASA’s Apollo astronauts returned, which ranged between 3.1 and 4.4 billion years old.

By studying samples from rocks that formed relatively late in the Moon’s history, scientists will be able to better understand what was happening on the Moon at a time when multicellular organisms may have already been present on Earth. Knowing the Moon’s history also helps us understand how Earth and the other worlds in our solar system evolved.

How Chang’e-5 works

Prior to Chang'e-5, no spacecraft has returned a sample of the Moon to Earth since the Soviet Union’s Luna 24 mission in 1976. Chang’e-5 undertook this challenge using an architecture similar to NASA’s Apollo missions. The spacecraft consisted of 4 pieces: a service module, a lander, an ascent vehicle, and an Earth return module. In lunar orbit, the lander and ascent module descended to the surface while the service module and Earth return module remained in orbit. The lander collected 1.7 kilograms (3.7 pounds) of samples using a mechanical scoop and a drill that could burrow 2 meters underground.

The Chang'e-5 lander also carried three scientific payloads. A suite of cameras documented the landing site, a ground-penetrating radar mapped the subsurface, and a spectrometer studied the mineralogical composition of the landing site to calculate how much water is locked in the lunar soil. Scientists will be able to compare these readings with the samples they study back to Earth.

Relying only on solar power, Chang’e-5 landed in the lunar morning and blasted the ascent vehicle back into orbit before nightfall—a period of roughly 14 Earth days. The ascent vehicle rendezvoused with the service module and transferred the samples into an Earth-return capsule. The service module jettisoned the ascent vehicle, left lunar orbit for Earth, and released the Earth-return capsule shortly before arrival.

Vehicles reentering Earth’s atmosphere from the Moon travel much faster than those returning from low-Earth orbit: about 11 kilometers per second versus 8 kilometers per second. Whereas human-rated vehicles like NASA’s Apollo capsule relied solely on strong heat-shielding, Chang’e-5 performed a “skip reentry,” bouncing off the atmosphere once to slow down before plummeting to a landing in Inner Mongolia. The landing site was the same used for returning crewed Shenzhou spacecraft.

After dropping off its Moon samples at Earth, Chang'e-5 left for the Sun-Earth Lagrange point 1 (L1), where Earth and the Sun’s gravity balance in a way that spacecraft can remain stable for long periods of time. This location is particularly well-suited for solar observations; Chang'e-5 conducted technology tests to help engineers plan future missions there.

The spacecraft then moved from L1 back to the Moon, entering a fuel-saving Distant Retrograde Orbit (DRO) to test technologies for future Chinese missions.

Support missions like Chang'e-5

Whether it's advocating, teaching, inspiring, or learning, you can do something for space, right now. Let's get to work.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth