Cassini, the mission that revealed Saturn

Highlights

- NASA’s Cassini mission orbited Saturn from 2004 to 2017, circling the planet 294 times and teaching us almost everything we know about our ringed neighbor.

- The spacecraft measured the structure of Saturn’s atmosphere and rings as well as how they interact with the planet’s moons.

- Cassini also discovered six named moons of Saturn, and revealed the moons Enceladus and Titan as potentially promising locations to search for extraterrestrial life.

What was Cassini?

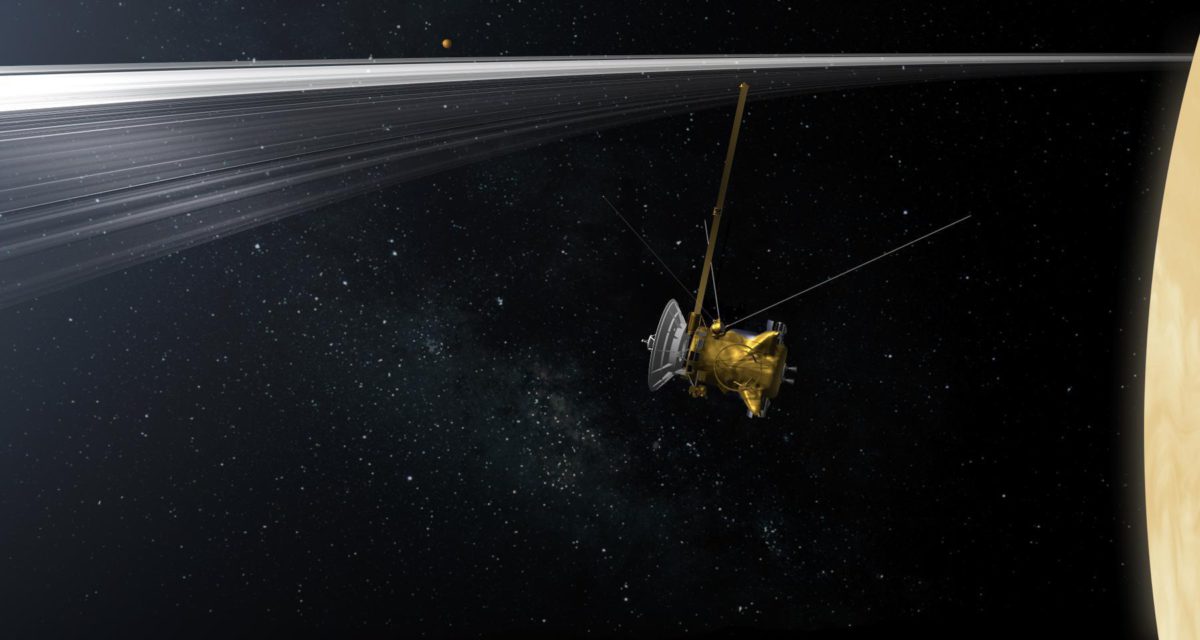

The Cassini spacecraft orbited Saturn for more than a decade, giving us unprecedented insights into the planet’s inner and outer workings. It was primarily a NASA mission, although it also included a craft called Huygens, built by the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency, that landed on the surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan.

The mission launched in 1997, flying past Venus and Jupiter on its way to Saturn. It arrived in orbit in 2004, and thanks to three mission extensions it spent 13 years revolutionizing our understanding of the system. It took more than 450,000 images, discovered six named moons, and taught us about not only the Saturn system but the possibilities for planets and moons everywhere.

At the end of its mission, Cassini executed a maneuver called the “Grand Finale.” It circled closer and closer to Saturn’s cloud tops, between the planet and the rings. Then, on September 15, 2017, it plunged into the planet’s atmosphere — this was the only way to ensure that it would never smash into any of Saturn’s moons and contaminate them with any Earth microbes that managed to cling on to it. It continued transmitting data for 30 seconds longer than expected, but eventually, it burned up.

How Cassini worked

Cassini was one of the largest and most complex interplanetary spacecraft ever, weighing in at 5,600 kilograms (12,300 pounds) at launch. That included 32.7 kilograms (72 pounds) of plutonium to power the spacecraft and its instruments. Cassini had 12 scientific instruments divided into three sets of tools.

The first of these was the optical remote sensing suite, which included cameras to observe the Saturn system in infrared, visible and ultraviolet light. This allowed researchers to create maps of the composition and textures of the planet’s atmosphere, rings and moons.

The second set of instruments was concerned with fields, particles and waves. Most of these measured the medium through which the spacecraft traveled, including charged particles and dust from the atmospheres of Saturn and Titan. There were also two instruments to measure and map Saturn’s magnetic field and how it interacts with other fields in the area, and one to measure radio signals coming from Saturn.

The third and smallest set included radar to pierce through Titan’s hazy atmosphere, as well as a radio science system. The spacecraft’s communication antennae would send radio waves through objects in the Saturn system to Earth and examine how they changed.

Cassini also carried with it the Huygens probe, which had its own set of six scientific instruments to examine Titan’s atmosphere as it fell to the surface.

Major discoveries at Saturn

Cassini provided a wealth of data on Saturn, enough for researchers to analyze for decades to come. It measured the rotation rate of the planet — which proved to be more complicated than anyone had suspected — using several different mechanisms, as well as the difference between the overall rotation and atmospheric motion.

That atmospheric motion included enormous storms and jet streams that we’d never seen up close before, in addition to colossal hurricanes at the planet’s poles. The craft also found lightning, taking the first videos of lightning on any planet beyond Earth. It also greatly deepened our understanding of the atmospheric makeup of the planet.

Moons and rings

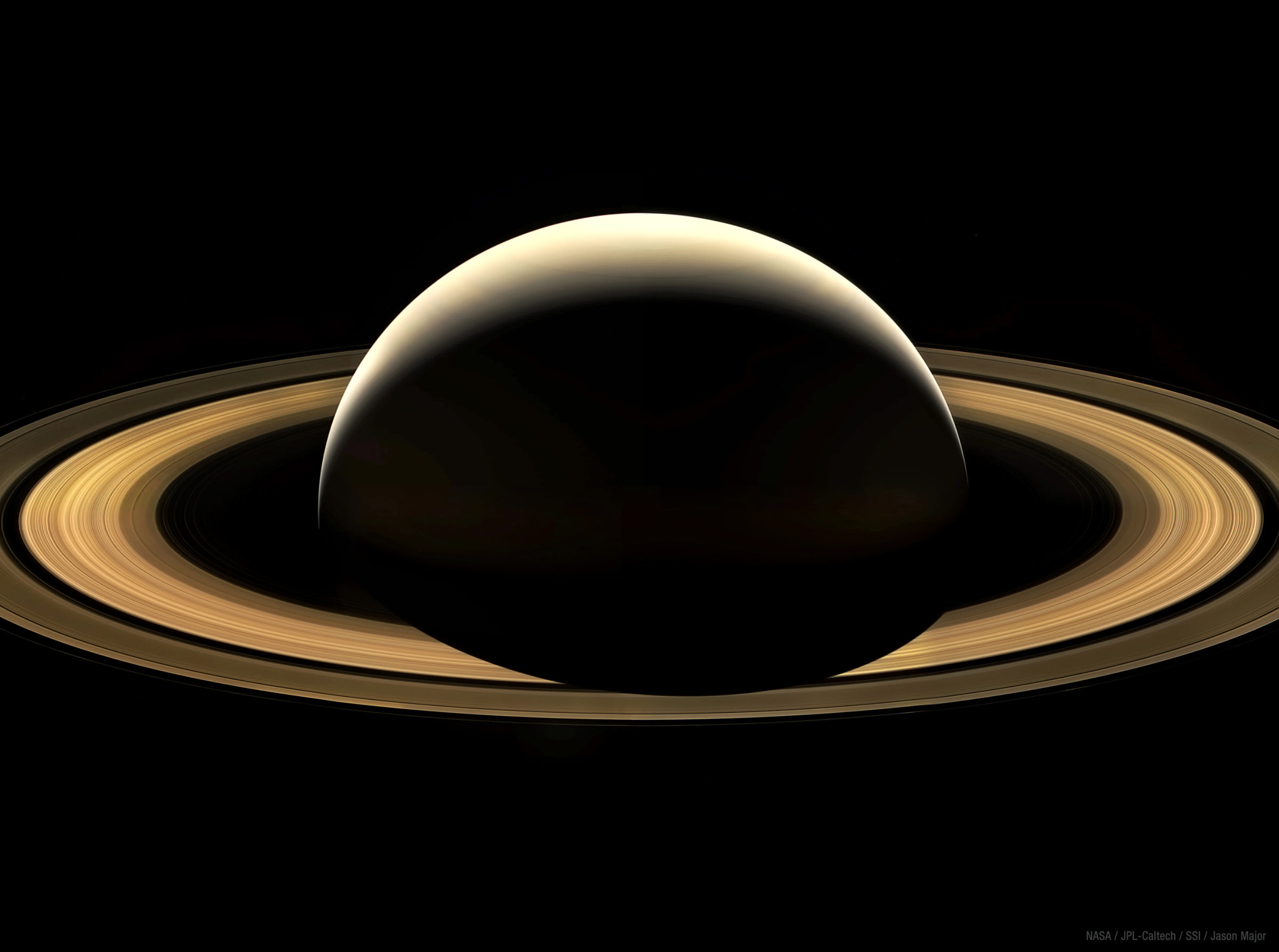

Many of Cassini’s most exciting findings were not about Saturn itself, but the rest of its system. Some of these regard Saturn’s majestic rings.

Cassini found that the rings are made up of chunks of ice and rocks ranging in size from smaller than a grain of sand to the “propeller” moonlets that cut gaps through the smaller particles. It measured waves in the rings that revealed some of the interior structure of Saturn itself, and also found that much of the material in the outermost ring comes from the water jets that spout from the moon Enceladus.

The discovery of these jets was one of the mission’s most dramatic findings. When Cassini flew directly through them in 2008, it found a surprisingly large concentration of organic compounds — chemicals containing carbon — in the water. These compounds are thought to be important for the development of living organisms, so they made Enceladus a particularly tantalizing destination for the hunt for extraterrestrial life.

Likewise, Cassini discovered tantalizing hints about the nature of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. The spacecraft made 127 flybys of Titan, peering through the moon’s dense, hazy atmosphere. The Huygens probe also took crucial atmospheric data as it fell through the haze, and sent back pictures from Titan’s surface once it landed. These measurements revealed an atmosphere full of complex molecules, clouds of liquid hydrocarbons, and seas of liquid methane and ethane — the only liquid seas we’ve found on the surface of any world beyond Earth. They also provided evidence for a liquid water ocean beneath the huge moon’s surface. All of this together makes Titan a good place to search for alien life as well.

Support missions like Cassini

Whether it's advocating, teaching, inspiring, or learning, you can do something for space, right now. Let's get to work.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth