Planetary Radio • Mar 03, 2023

Space Policy Edition: The Tricky Ethics of Space Settlement

On This Episode

Erika Nesvold

Astrophysicist and author of Off-Earth: Ethical Questions and Quandaries for Living in Outer Space

Jack Kiraly

Director of Government Relations for The Planetary Society

Casey Dreier

Chief of Space Policy for The Planetary Society

Humanity is on the cusp of attempting permanent settlement on other worlds. But who gets to go? How will we govern ourselves or enforce laws off Earth? How can you have property rights, labor rights, or even individual rights when the very air you breathe is limited and potentially controlled by your employer? Dr. Erika Nesvold, astrophysicist and author of the new book “Off-Earth: Ethical Questions and Quandaries for Living in Outer Space” explores the ethical challenges facing our species as it dips its toe into living beyond our home planet.

Transcript

Casey Dreier: Welcome to this month's Space Policy Edition. I'm Casey Dreier, the chief of Space Policy here at The Planetary Society. You may notice the absence of my colleague, Sarah, who is unfortunately sick and unable to join us. But really excited to have with me this month my new colleague who we teased last month, Jack Kiraly, the director of government relations here at The Planetary Society. Jack.

Jack Kiraly: Hi, Casey. It's very nice to be here today.

Casey Dreier: Hey, Jack. Really excited to have you. We'll talk with you just a second about what you've been up to in Washington DC. But first I have to tease our episode this month. I'm really excited to introduce Erika Nesvold, a PhD astrophysicist and author of the new book Off-Earth: Ethical Questions and Quandaries for Living in Outer Space. Will be joining us here in just a few minutes to talk about the variety of ethical implications of space settlement and space exploration. These are really fascinating topics to me, and we've had space philosophers here on the show in the past. Erica's book is super accessible, really provocative, really interesting, and goes on sale this next week in the United States and around the world. She'll be joining us here in just a few minutes. Do not miss out on that interview. In the meantime, Jack, you already started working for us here at The Planetary Society. How's your first weeks been?

Jack Kiraly: So the first few weeks have been great. I'm not sure if this is what every month has going to be like, but being out in Pasadena with our communication staff for the staff retreat was great. Getting to know everybody on staff at The Planetary Society and folks on the board has been fantastic, a great opportunity. And I'm really looking forward to hitting the ground running here in DC.

Casey Dreier: And I think you really are, and I don't just say that as someone who is nominally kind of helping to tell you what to do. But you've been meeting a lot of offices, you've been out in the ground already, getting to know people, representing The Planetary Society. What are some of the big topics just in your introductory meetings, you've been having people that have been coming up? And what kinds of interactions have you been having with members of The Hill already this year?

Jack Kiraly: So far, just in the last week, I've visited approximately 70 offices on the House of Representatives side of the Capitol Building, members of the House Science Committee, the Space Subcommittee, very particular there. But the whole Science Committee is a very important group of people I've been engaging with. Members of the Commerce, Science and Justice Subcommittee within the Appropriations Committee who control the purse strings. Right? Control the budget for NASA. Been meeting with those folks. As well as some folks that we've had in the pipeline for a long time that we know are strong advocates for space science and exploration, but may not sit on a relevant committee, but nonetheless are important stakeholders in these decisions. So that's how I've been starting my days, meeting with those folks. These preliminary conversations have just been reiterating our priorities, the search for life, exploring worlds and defending the planet. Which has been shared with everyone that I've been able to meet with so far, who have welcomed me warmly in this very politically contentious time in Washington. Space is a great thing that brings people together and is a point of light for a lot of folks on The Hill.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, really glad to hear that. I mean, there are times when I'm just so grateful we get to talk about space all the time. And even this upcoming interview with Erika where we talk about space ethics, which becomes all these thorny issues start to just emerge from this [inaudible 00:03:42] of the concept of how you live in space together as a society. When it boils down to it, it's just such an amazing way to get people thinking about topics and considering and working together in ways they wouldn't normally do in other contexts. Right? And so it's just like this opportunity to bring that and share that excitement and that passion, and our members' excitement and passion. I'm very grateful to do it and it must be fun for you to kind of... Your background is in electoral politics, a different type of interactions with people. But that energy must be kind of similar, right? Where you're motivating people and getting people to engage in our democracy.

Jack Kiraly: I mean, it all comes down to motivating people to action, right? Whether that's getting them to the polls to vote for a preferred candidate or for a particular initiative, or getting your member of Congress to really engage on an important topic like space science and exploration. And you're absolutely right, it's an inspiring area of policy. Inherently, space exploration is cool. It's not something that you get to talk about every day, but we're lucky that we do. That it is our day-to-day existence and I bring that enthusiasm to The Hill. It is something that when I walk in and say I'm with The Planetary Society, the tone of the room changes dramatically when I get in there. Space exploration's the one thing I think everybody on The Hill can agree on.

Casey Dreier: Jack, really excited to have you working now for us full-time. Something is coming up in our near future, and for listeners of this show, you know what time of year it is, right? This is the start, the little shoots, the robins are in the air, the worms are coming up out of the ground, little buds on the trees. That can mean nothing else but the President's budget request is nigh facing us.

Jack Kiraly: The PBR.

Casey Dreier: The PBR. And at the time we're recording this, we have not seen it. We expect it to come out March 9th. And we don't actually know if that's going to be a full, completely detailed dive that shows everything that we're used to seeing or an initial, what they call a light budget. But the details will be coming out here in the next few weeks that fundamentally set the stage for the entire political discussion about spending in this upcoming fiscal year, fiscal year 2024. What are you able to do, Jack, as we're waiting for this to happen? Are people just kind of sitting back or what can we do to prepare? Or is it fundamentally, we have to kind of wait to see what this opening ante is before we can really take some concrete actions?

Jack Kiraly: Well, on the budget in particular, it is kind of a big hurry up and wait moment right now. The conversations, preliminary conversations I've had on The Hill have generally all pointed to the same answer of we're, "Waiting for the PBR." Democrat, Republican, Independent, everyone's just sitting with baited breath for what the President's budget request will contain. In the interim, there is another facet of the Congress that we can focus on, and that's the authorization process, the actual thing that tells the various administration entities what it is they're allowed to do. And the authorizing legislation for NASA, we got a small authorization last year, as you've talked about in last month's episode, I believe, or in a previous month's episode, within the CHIPS and Science Act. This sort of mini authorization got us through to this year. Didn't authorize a lot of new programs, did reauthorize it for this year. But this new authorization, the rumors I guess that we've heard of a new authorization is the thing that we can be working on continuously now, before the President's budget request. Kind of on a completely different track than the budget, this authorization legislation really sets the stage for what NASA is able to do, and potentially sets up what it's going to be doing 5, 10, 15 years out from now. So authorizing legislation is sort of more forward looking. It's not just looking at the next fiscal year, but looking at fiscal years further down the line. And can really be sort of the thing that sets the stage for planetary science exploration for the next decade or longer.

Casey Dreier: Right. It's setting congressional... It's policy at the end of the day. It's telling this is what NASA does, and by implication, doesn't do. And yeah, I was just thinking is if only someone had done a big research project recently tracking NASA authorizations through history.

Jack Kiraly: There was a great article in The Space Review, that I believe a link might be in the show notes, right?

Casey Dreier: I literally actually did as we were prepping the show, forget to talk about this, but we're going to talk about this now. But yes, NASA authorizations are an, I don't know if they're underappreciated, but less frequent opportunity, but can have very significant consequences to what NASA does. It was the NASA authorization of 2010 that mandated the space launch system that continued Orion. That set this kind of goal of building this heavy lift capability for NASA, that obviously now we're seeing the fruits of 10 years later. But they happen relatively and frequently in the modern era. And this was at a project I did with a volunteer intern of ours at Alex Eastman, who came to the society in January and did some really great work with me. And we published this article in the Space Review, which yes, is linked on the show notes, looking at trends about how this NASA authorization has changed over time. And it used to be like clockwork. Every single year you would have an authorization, authorization, authorization. This is all part of this concept of regular order, where you would have these authorizing committees reestablish and reauthorize the behavior functions of both the program itself, the agency itself, and authorize overall spending. So they used to be much more spending focused. And then appropriators, knowing what these rough authorizations of functionally spending caps were, could appropriate up to those levels. And starting in the mid '80s, these authorizations started to get more and more and more, we described it as prescriptive, but longer and longer. And then starting in '94, the rapidity, the frequency of them dropped precipitously. And we used to have an authorization every year, but since 1994, we've only had six total in the last 25, 30 years. And so it would actually be unprecedented in the modern era to have an authorization this year after passing a mini authorization last year. That doesn't mean it can't happen. It gives you a sense for how these aren't guaranteed things. They don't have to happen the way appropriations do, right? NASA can obviously operate without an authorization. But yeah, it was a fun project to put together. And authorizations can be really powerful when deployed correctly. And particularly for, we saw this last year, like the authorization which stated that NEO Surveyor is a mandated program for NASA. That is an authorized specific program that has an author... Like stated a launch date. This is not an option for NASA to do anymore. This is passed by congressional legislation, signed by the President, NEO Surveyor is in law. Right? So there can be, even though funding then comes later, this is very influential and powerful pieces of legislation. And great point, this is something that we can work on now while we're waiting for the actual money to show up or the discussion of the money, which itself has, as we talked about in earlier episodes, a challenging path ahead, let's say, in the current political environment to have an appropriations cycle succeed successfully. If that's the right [inaudible 00:11:19] in the technical terminology later this year.

Jack Kiraly: Right. And the other thing about that is the PBR is going to kick off this process, but this is a process that's going to last six months or longer. Because the federal fiscal year ends in September, right? September 30th is the last day of the federal fiscal year. October 1 begins FY 2024. So in that interim period, Congress is still at work, Congress is still passing legislation. And as you've noted before, as we've seen in the past, there's not a lot of space legislation, and specifically when it comes to planetary science and planetary exploration. There is not a definitive outside of the authorization process, another piece of legislation. Maybe that's a direction that the Congress heads in the future. But as it stands, the precedent is that the NASA authorization bill is going to prescribe what NASA will be working on. As well as keeping it vague enough that within certain programs they can sort of be a little bit more nimble in responding to needs of the scientific community. But the NASA authorization is going to set policy for the space administration, not just for this year, but likely, based on your research, for the next five, maybe even longer years.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. So again, this is something you'll be hearing from us about in the next few months, particularly with the budget, about opportunities for you to take action to support some of our priorities. Really keeping an eye on Mars sample return, really keeping an eye on Artemis, really keeping an eye on planetary defense. So these big core issues of the planetary society and why people are members, right? Why you're joining us as a member. We need to keep those priorities moving forward. And so we will be really watching this closely. We will have the whole next episode focused on what was in this 2024 budget. But until then, Jack, I think this is an opportunity for us to think about these long-term commitments about how we get to where we're going. One of these ways in which we can do that is what our guest today, Erika Nesvold, is going to be talking about. And something that she's studied over the years, which is the ethics about how we go, why we go, and how we're going to live together and how we can live together ethically and responsibly. What lessons can we learn from the past. And how we can apply those, going forward into the future. I think space is always interesting to me, because it's so much how we talk about it. Is based on this kind of utopian ideals of betterment and evolution. And rarely though do we think about how we apply those ideals to the structure of societies themselves, versus just happening naturally. And so, Dr. Erika Nesvold, she had a whole podcast series on this, which I really recommend. Very nicely produced and put together, called Making New Worlds. She's also the co-founder of the JustSpace Alliance. And she wrote a brand new book, which is coming out this month, called Off-Earth: Ethical Questions and Quandaries for Living in Outer Space. Erika joins me now. Dr. Nesvold, thank you so much for joining me on this month's Space Policy Edition.

Erika Nesvold: Thanks for having me.

Casey Dreier: So I have to say, really enjoyed reading the book. I was very delighted that it's a super readable and very accessible book on space ethics, which not all of them are. Although they all tend to be interesting. So just want to compliment you there. And I really do recommend our listeners today, check out the book. It's really engaging, provocative, and if nothing else, you wrote an interesting book, which also is not always the case. So very much enjoyed it.

Erika Nesvold: Thank you.

Casey Dreier: I have a million questions and topics based on this though, but let's kind of start big picture with this book. This is about ethical questions, right? And how we start to think about that as we go, particularly in the context of space settlement. So after reading the book, and I'm curious to feel like where you ended up with this, do you think it's ethical now to begin to settle space with humans?

Erika Nesvold: That's a great question, and of course it's the one that I keep coming back to whenever I do this work. I actually, I have a whole chapter about whether we should settle space. And it's funny, I kept moving that between the start of the book and the end of the book, because I think you need to think about it at both places, right? When you start thinking about whether we should be doing activities in space at all, you have to consider what you're doing. And then as you start thinking through the details of the challenges we'll face, you have to keep coming back to that question. So I definitely cite people in the book and I've talked to people, like colleagues, who don't think we should settle space. Or at the very least that we are not ready as a species, as a society, and that we should wait until we've matured somehow. At this point I don't agree with that kind of strong statement, partly because I am concerned about the existential risk of just keeping all of our eggs in one basket and on one planet. And I think that spreading out to different planets will help us survive in the long term. But also because I don't think there's a way for all of us to get together and agree what counts as being mature enough to deserve to go out into space. But I think that it's not a binary yes, no question, right? There's such a spectrum of how we do it and how we take our time, how we have these kinds of conversations about what we should be doing in space. And I think that's what's important, is that we do things thoughtfully, deliberately, with a lot of conversations all over the planet amongst humans.

Casey Dreier: I recalled from your podcast, which kind of kickstarted this book, you went out right ahead and said that you are for, you want to see space settlement. And I guess when reading your book, I didn't detect quite as strong of a clear statement. Did that evolve over time, from when you did the podcast five years ago, to the book?

Erika Nesvold: I think that intuitively, I still feel just as strongly, but I think it's always important to recognize emotional motivations within ourselves, right? There's still the 10-year-old inside me who just thinks it's neat. In between doing the podcast and the book, what happened is I read more diverse opinions on this. And while they didn't fully change my mind, I think it's really critical that even if you think 100% humans should be settling space, we should be doing it right now, I still think it's important to read these other viewpoints, to talk to these people, figure out where they're coming from and consider what they have to say about the details of your plants, the motivations you have. Questioning on motivations is a big theme throughout this book.

Casey Dreier: And speaking of motivations, you have these big themes, as you said, just in your book, who gets to go? Why do we go? And what's life when we're there? Do you feel like we haven't yet solidified again this why we're going question enough or is this the time to really be asking it as we start to feasibly do it?

Erika Nesvold: This is absolutely the time that we should be asking why we're doing this. I mean, should've been doing that from the start, although I think a lot of people spend time thinking about why we should settle space because they're trying to craft a message to advocate for space settlement. And those narratives tend to be, in my opinion, over exaggerated or at least not well examined. Because they're marketing pictures, right? They're trying to convince everyone that this is a good idea. And that's what's been taking up most of the airtime, most of the conversational space in the public, is people who are either trying to get investments or trying to get popular support for more human activity in space. Has that solidified? No. And in fact, I think it's diversified over recent years. Certainly with the growth of the private space industry, so we've got this profit motive in there, that some people are just in it to make money. Other people think that they are trying to save the human race from extinction, the motive I mentioned before about not keeping your eggs in one basket. Some people are motivated by the science, I mean, as a scientist myself, that's certainly why a lot of people have been working on space flight throughout their whole careers. And other people have loftier and/or vaguer motivations about human destiny or what they see as the nature of humanity is to explore, et cetera. And so I don't think we'll ever solidify on one reason, because I think every individual person has multiple reasons themselves. And so I think more conversation, more people with different opinions and different motivations coming together and discussing them is what we need. More than certainly a unified motivation.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. And you make a really great point in the book, and you alluded to it just now about the types of people talking about space settlement are not a random selection of all of humanity generally, right? They tend to be space settlement advocates and they have an agenda to push. And it just really reminds me, and I think what struck me from your book itself was this realization and acknowledgement, and you have a nice line in here, your utopia is not necessarily everyone's utopia, or I'm paraphrasing. And that we're bringing and have brought a lot of cultural assumptions about what motivation is and what resonates with people as this kind of assuming some kind of foundational belief. And that's what I found really refreshing in your book, that there's this classic, say Western, you alluded to, they're kind of manifest destiny American style, we're God-given right to expand wherever we go, and it's a disappointment if not. And you have a lot of great quotes from early, mid 20th century space authors and sci-fi authors that kind of connect this ethos. And of course that's really present in the early discussions. Even von Braun and early space advocates, it's this idea of endless expansionism. But of course, you talk to other types of people who've been on the receiving end of that expansionism, that's not seen as some universal good to say the least. And this idea of what assumptions we have that we need to examine or at least be aware of, that the word we is an inappropriate term for. Are there things that can be claimed as universal or near universal that can act as fundamental motivators? Or are we always going to be a pastiche of motivations depending on the culture that we've inherited or born into?

Erika Nesvold: Oh, I think we'll always be a mix. You'd have to ask anthropologists and sociologists for their expert opinions on whether they're unified motivating factors for humans. I think you could talk at a really biological level perhaps. But even there, people advocating for space colonization try to argue that there's a biological, even genetic urge to explore, and I'm not convinced by that either. I think there'll always be a mix. And in particular, just the fact that there are people who don't think we should settle space indicates that there's always going to be a diversity of opinion, which I think is fine. That's great. The problem is when people try to take this grand plan that we're all talking about, that humanity would have to do on a global scale in order to be successful, big problems, big questions long into the future, involving lots of people. And so it's very easy to slip into using we to mean all of humanity. And you end up finding yourself speaking on behalf of all of humanity, and none of us are qualified to do that. In particular, most of the people in the space industry are not qualified to do that because we're not social scientists. Right? We're very, very poorly trained, based on our educational backgrounds, very poorly trained on things like history, international relations, political science, psychology, anthropology, things like that, that would make us even slightly qualified to speak about humanity as a whole and what humanity as a whole wants. And yet people do it anyway. And that's what I'm trying to draw attention to is slow down when you're making these grand statements about our destiny lying in the stars and everybody must want this because it's our human nature, question that assumption.

Casey Dreier: Right. Well, it's also easy to romanticize it after the fact as well. And this is a huge theme that I kept resonating with in your book, reminding everyone that the actual activity of settling space, at least in the beginning, is neither romantic nor easy, nor even fundamentally comfortable or maybe even desirable for most people. The intense deprivation that will be omnipresent, at least at the beginning, fundamentally seems to change and challenge this very notion of this romantic exploration ideal.

Erika Nesvold: Certainly. And part of the problem is likely that we, by we in this case, I mean Americans working in space in particular, were raised on stories of the wild, wild west, with the mythology of settler colonialism being a great thing and manifest testing and such. And all of those rough and tumble western towns where people are building a grand future. So we're raised on that view of what actual colonization was like on earth, and all of the science fiction that shows the challenges and conflicts of living together in space, but mostly in a shiny, laser-gun fun sort of way. And neither really dig too far into the hard scrabble life, the ethical challenges and tough decisions you have to make, the likelihood of failure, the ease of which the environment can force you into dystopian political systems, things like that. We're starting to get more science fiction like that, which is great. But we need to recognize when we're being influenced by fiction and by cultural mythology in general.

Casey Dreier: I'll jump forward a little bit on this theme. I was fascinated by this idea, again, reading through your book, that is ethics itself a luxury good, in the sense that the modern aspect of ethics, and this kind of goes back to the concept of we and where we draw our cultural expectations and demands for behavior, what society owes us and so forth, comes from a perspective of abundance now. But a space settlement, as we were just talking about, is almost this throwback to this, I don't know, maybe pre-history is too far, but pre-modern era of deprivation, struggle, where even the air you breathe is a luxury good. And so can ethics, an ethical system derive from the expectation of equity and equality and fairness and compassion, coexist in what will be a highly dangerous and under abundant environment to exist in? Are we applying expectations here that are impossible to meet?

Erika Nesvold: Well, two things give me hope about that question. I mean, aside from the fact that I'm just an optimist by nature.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. I don't mean to sound so dreary in that question, but it was kept...

Erika Nesvold: It's a question worth asking. One is that in contrast to the people who have struggled to make good ethical decisions in colony settings here on earth in the past, we have the benefit of all of history to learn from, we just need to make the effort to learn from it, to recognize what's gone wrong. What cultural value changes could prevent us from repeating those mistakes, those horrific mistakes of the past in the future, and passing that down to our descendants who will one day be having to make these decisions in a rough environment in space. So I think that having access to that knowledge and all of the discussion around the facts and history, I think will benefit from that. And number two, this might be the optimist in me again, but humans are better than our current culture assumes when it comes to a dangerous and risky environment. There have been studies demonstrating that after disasters, in particular natural disasters, humans tend to come together, they tend to help each other. They protect their families and friends and also their neighbors. And so that gives me hope for the really difficult lives and environments that people will be living in in space, in the future. So I think it could go either way, honestly. But I think that if what one thing history has taught us is that we're capable of horrific things, but we're also capable of pulling ourselves together and getting better over time. And that's what I really hope is that not only can we learn from the mistakes of our past, but that we'll continue to learn from any mistakes that we will inevitably make in the future in space.

Casey Dreier: That's a very good answer to my otherwise despairing question. But I mean, your point is well made, that to act as if it's impossible and then to give up in advance seems like a failure in some way of our modern selves, if nothing else. And so in that sense, I think it's ethically imperative that we try to consider this. Even if the actual application may be difficult and challenged, at least try to bring that in to this discussion, which you're doing here. I want to highlight just a couple of major areas that you talk about, and I'd like if we can summarize some of the challenges and some of the research that you found in these areas. And then we can keep talking about some of these bigger questions that I'm just endlessly fascinated by. But again, you start with this idea of, we talked on a little bit who gets to go, but let's expand on that, in that process.

Erika Nesvold: Yeah, this is one of these ethical questions in the book that I think is the most urgent, because it's questions that we have to make today, and have been since we started setting people into space. Is how do we decide who gets to go to space and who gets to make those decisions at all. So for a long time on earth, that decision has been up to the space agencies, the government-run space agencies who tended to be selecting initially military test pilots, which were very narrow demographic due to the time that it was, and hasn't grown much beyond that. They've opened up a little bit, NASA and such, they've sent civilians into space, but they still have very strict medical requirements, physical requirements in particular that shut a lot of people out of the space program. And it's just extremely competitive. Now, with the private space industry, the answer to the question who gets to go is expanding in interesting ways. Because now if you have enough money, then you can buy a ticket into space. Or if you could convince someone else with enough money to buy you a ticket into space, that'll get you there too. And so there's this extra new category of people and a new decision-making process, which is still providing us with a very filtered version of humanity that's getting to go into space. This is going to continue to be an interesting question. Every time we launch people into space, someone has to decide, "Well, who are we launching into space?" And this will become a really fascinating question when we get to the point where we're asking who gets to go live permanently in space. I think the answers will depend on why we're going. So I talk in the book a bit about, okay, well, there's going to be a different answer if we're all fleeing from the earth in lifeboats because the planet's about to explode, versus we're just trying to start the first settlement on Mars, for example, and we're trying to make it as likely as possible that it's going to succeed. You'll get different sets of people, different decision makers involved. And this question is just endlessly fascinating to me because even people today who are otherwise very similar working in the space industry, have very different opinions about how we should be making these decisions today. Whether it's a good thing that billionaires can now diversify the space traveler population through their choices, versus should we continue to let governments make the decisions. I think it'll continue to reflect all of these big questions about why we're going into space at all.

Casey Dreier: I find it really interesting, there was a discussion about ableism and whether people have fully physical disabled or completely kind of normatively abled in terms of how they're able to act in a space settlement. But you had experts point out that it doesn't matter if everyone is fully ambulatory and can use all their limbs, because there're accidents will happen or people can be born with different abilities. And suddenly, even though you didn't select people with the anticipation that you had to adapt to their needs, you're going to have to deal with it eventually if you are really serious about long-term existence. There'll be people with a variety of physical differences that you have to accommodate, unless you take a harsh Draconian level of dissonance to human life that I don't think anyone is prepared to do anymore.

Erika Nesvold: It's certainly understandable why NASA and other space agencies have strict medical rules. Particularly that exclude people with risky medical conditions, because they have their own set of ethics and they don't want to put someone into space that then may have a medical problem that they can't help them with while they're in space. So that's been part of their motivation. But another part of their argument for these strict medical screenings is that the person has to be physically able to do the job of being an astronaut. And there's probably a much bigger diversity of body size and shape and ability that can accomplish these tasks in space than NASA currently accommodates. The European Space Agency is starting a new program to test whether space travelers with a certain specific set of disabilities can accomplish these astronaut tasks, like lower limb differences and short statures and things like that, which I think is a step in the right direction. But when you extend your timeframe and think, "Okay, well, what if it's not an astronaut on a one-year mission who gets to go back to earth afterwards? What if someone's living in space permanently?" At some point, disability comes for us all if we live long enough. And, as has been pointed out to me by various disability rights activists, in space, we're all disabled. It's not an environment that we evolved to exist in. And so we design our technology for living in space to be accessible to us, to improve the accessibility of the environment. It just makes sense to keep thinking about accessibility in our design for space habitats. Because the more accessible we make it for specific disabilities, the more accessible it is for all of us. And that way you don't have to worry about, well, what if someone is born into the space settlement with a disability, because you're already thinking about how to make your space settlement more accessible.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, a wonderful point. And this idea that who's going to be perfectly adapted by prior existence to living on Mars? No one really, by definition. Though, again, this raises that issue though of resources that are then required for this, right? Where we are coming from this, I was thinking a lot about the Americans with Disabilities Act passed in, I think '91 or 1990, that requires accessibility ramps, certain sizes of doors, access to restroom facilities, all these very reasonable compassionate things, but takes a lot of resources, space, extra construction requirements, extra planning to implement. And we can do that in a wealthy society. We can do that in most modern societies. But if you start imposing that on a settlement struggling to survive, I can see how there will be this... This is where tensions like this start to arise, this conflict between resources and what we owe as a society to everyone living within it to have equal access to participate within it. And that brings me to this other aspect, and when we're talking about who gets to go, this difference between, in a sense, of public concern versus a private concern. And I think this idea, and so much of what we talk about in terms of society, we expect that society is this kind of consent of the governed. We owe it to ourselves. And government, public government by definition can be inefficient because it has a responsibility to have to include everybody. This idea that everyone should be represented at some level. And this then comes down to who gets to go. If there's a private company going, they nominally have no responsibility to be representative or compassionate. Maybe compassionate, but you know what I'm saying, right? They don't have any social responsibility beyond their own goals, because they're inherently different than a public concern. And this theme came up over and over again. So I'd like you to expand a little bit about this role of how do we start to accommodate private enterprise, private organizations, private individuals being on the vanguard of space settlement, when these expectations don't apply or at least are hard to enforce?

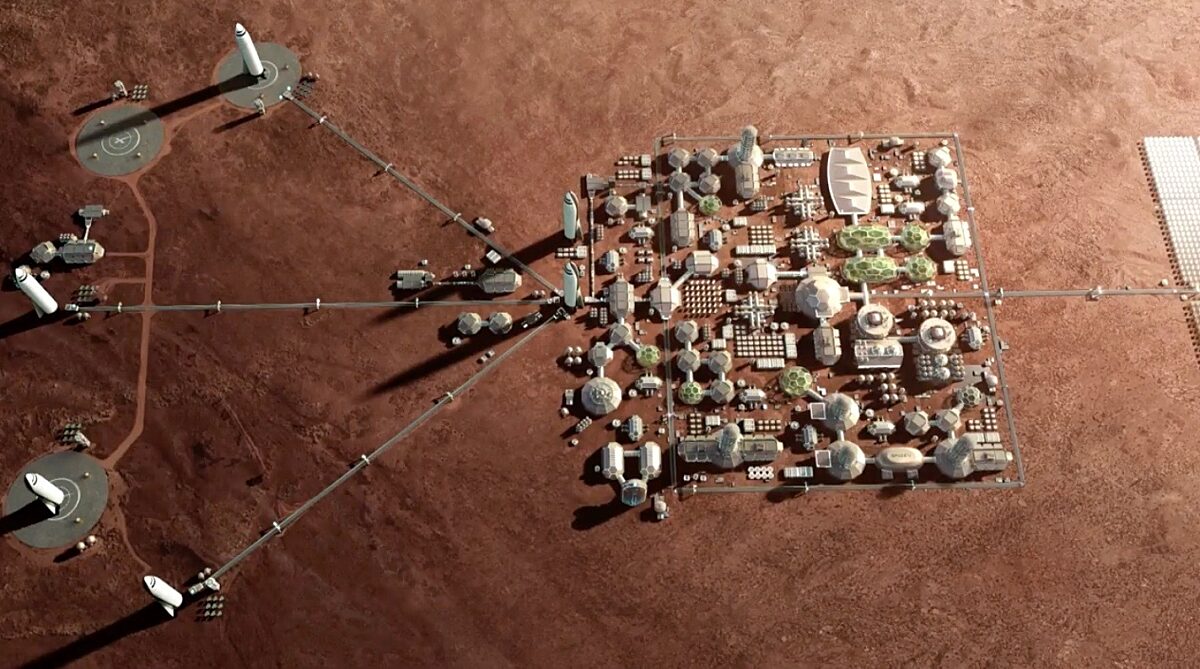

Erika Nesvold: Yeah. This is a question that starts to get into space law and regulation, right? Now that we have these new players that didn't sign The Outer Space Treaty, the international treaties about this. How do we regulate their behavior so that they're not running off and doing horrific things in space, because it makes a profit for example? And part of the answer is, well, we have The Outer Space Treaty. And while it doesn't specifically cover private companies or individuals, because it was signed in 1967, when mostly everyone was worried about the Cold War in nations. It does say that anyone launching into space needs to have continuing supervision by the launching state, wherever you launched your rocket from. It remains to be seen what that's going to look like. And I've talked to several space lawyers who argue about how continuing the supervision needs to be and how exactly you would monitor a private company's activity out in space, literally, farther away from the planet than potentially your regulating bodies. And how you would enforce any regulations. All of this is untested in court. And these are all big questions that a lot of very smart people in space policy are working on, which is great. Aside from that, just the big question of public versus private entities and how they'll behave differently in space, I don't have an answer for. This is going to continue to be a struggle, especially now that we have a lot of people arguing that space settlement is only achievable through capitalism. You have to incentivize people to spend all this money. Space is expensive. Governments have decided it's too expensive to try to build base on the moon and Mars, for example, and so we need private industry to do it. I'm not convinced by that, but there's a lot of people making that case right now. And so I think we're just going to have to keep going and try to think ahead as much as possible and address problems when we get to them. A big problem that regulators have pointed out to me is that the pace of the growing space industry is going so much faster than regulation can keep up with it, which is frightening. But the people are working hard to try to anticipate these problems.

Casey Dreier: I think, to me, this whole difference between public and private enterprises or concerns, however you want to group them, going in for settlement, this is such a core element to me. And just from what we're talking about, again, that the public institutions have a responsibility and an expectation built in to have some kind of ethical responsibility to the public by definition. And that kind of implies to me that we should really, this is almost an imperative, that we need to be advocating for public institutions to think about settlement, not just exploration. And what, again, struck me over and over again reading your book, was that the vanguard of settlement right now is all private organizations and individuals. And public institutions have maybe initially talked about it back in the '60s or '70s or maybe even the '50s, but it functionally run away from that very idea for decades. Because it seems ill-conceived or unjustifiable with public funds. And there's a fundamental irony then, that the ones that then go out there in absence of, in a sense, let's say that the public good, are the ones that can only marshal that type of effort, energy, and focus, because it's essentially unjustifiable within the public good discussion. Right? We don't see Norway pushing the vanguard for space settlement in terms of its pseudo socialist system, right? We see more individual companies/individuals trying to fill that gap. And again, this strikes me as then a really challenging aspect, because those systems are not set up for this type of ethical input. It's only by their personal interest or graces that they have to listen to this.

Erika Nesvold: That's a really interesting point. I will point out though that we haven't entirely shifted from all public to all private. At this point, space is a public-private partnership endeavor. And even things that we think of as being clearly the face of the private space flight industry, like SpaceX for example, heavily government funded. And the US government in particular is trying to step farther along in the regulation and policy game, things like the Artemis Accords. Although, so far, the goal of those is at least partly to protect and incentivize their own private space industry, so it's a circular goal.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. Well, and just to clarify though, yeah, I mean, I think the space exploration is still very much a government game. But space settlement, and that's where I kept going is settlement. SpaceX is really the one company really talking about this. And after seeing Elon Musk's run of Twitter, maybe not the most equitable democratic society will be as a consequence of that. But again, I think or other companies that there's very few... I don't know if there's any nations, any nation states talking about settlement. And that's what really struck me reading your book. And these systems that are the ones set up for generally this kind of input.

Erika Nesvold: So I spend a lot of time talking to people, I have friends within the private space flight industry. And so sometimes talking about the dangers of the private space settlement model can sound like we're saying, "Oh, well, anyone doing it within a capital system, it's going to automatically be a dystopia because they're evil." But that's not, of course, what we're saying. At least not what I'm saying. There are plenty of people who work within the private space flight industry, who are trying to build towards a better future in space. To protect humanity, to experiment with newer, better ways of being a society. The problem is that the structure of the model itself, the incentive is to make a profit. The legal obligations are to the shareholders to make a profit. And that will inevitably conflict with how do we make a life better for the people living and working in space. And yeah, that's where regulation comes in and I just hope we can keep up.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. Bernie Sanders needs to start talking about space settlement to balance that out, I think would be the appropriate thing. But, I mean, I think that's really the core of it. If, let's say, just to balance this, to just draw very simplistic dichotomy here, if socialist systems are incapable or uninterested in space settlement, then it's going to be a reflection of more unequal, more hierarchical social organizations. And even in these private ones, hyper inequal, right? Because it's definitely not a democracy. And so then if those are the only ones interested of doing something, then that by default tends to be the system that gets pushed forward into the solar system. So there's a real problem there if public institutions are unwilling to talk about space settlement in a serious way.

Erika Nesvold: Yeah. And talk about in particular. I'm not saying for example, that Norway needs to go off and start a space settlement.

Casey Dreier: I am. I mean, absolutely Norway needs to.

Erika Nesvold: It sounds like you were. But certainly people who are coming from a more socialist mindset or even a fully anti-capitalist mindset, they could at least be thinking and talking about space settlement. Even in terms of, "Well, I don't think I want to put my money in space settlement right now, but here's how I would structure a society in space. Here are models that we can come up with. Here are arguments we can have about human rights now, before anyone's up there." And just join the conversation.

Speaker 4: We'll be right back with the rest of Casey's interview after this short break.

George Takei: Hello, I'm George Takei. And as you know, I'm very proud of my association with Star Trek. Star Trek was a show that looked to the future with optimism. Boldly going where no one had gone before. I want you to know about a very special organization called The Planetary Society. They are working to make the future that Star Trek represents a reality. When you become a member of The Planetary Society, you join their mission to increase discoveries in our solar system, to elevate the search for life outside our planet, and decrease the risk of earth being hit by an asteroid. Co-founded by Carl Sagan, and led today by CEO, Bill Nye, The Planetary Society exists for those who believe in space exploration to take action together. So join The Planetary society and boldly go together to build our future.

Casey Dreier: Speaking of socialist and capitalist systems, let's talk about property rights a little bit. That's another big section of your book. What are some of the sticky issues here with property and space. Particularly if you are a settler in a settlement, how would things like that work out and potentially not in your favor?

Erika Nesvold: Yeah. Speaking of capitalism, one of the big arguments within economics is that capitalism requires private property rights to be a thing in the system too. In order to incentivize people to work the land, whether that's mining ice out of it or growing crops or whatnot, they have to know that they have the rights to whatever goods they can get out of that land. So that's sort of very simplified description of capitalism. And the problem is that at the moment we don't have a system for private property rights in space. And it's unclear, in fact, I would say it's not a good idea whether we even should have private property rights in space. At the moment, The Outer Space Treaty says nations can't appropriate territory in space. So Russia or China or the US can't go up there and say, "This is our territory." But people are still arguing about whether that means a company can go up there and say, "This is our land for mining rights. We have the right to mine ice out of this part of the moon, and no one else can." The Artemis Accords are being aimed to try to address this to say, "Okay, no one's appropriating any land here. But if you mine ice out of it, you can sell that ice." It's sort of like international waters, you don't own the ocean, you can fish, you can sell the fish. That's the model that people seem to be aiming at right now, but that can easily still lead to conflict. All of this is about what are we going to have conflict over patches of land in space. And because so many people think of space and the valuable resources in space as being infinite, and yet the amount of resources that we can actually reach and make it worth mining or extracting are finite and located in very small patches in the solar system. So we're going to have to find out what happens when two companies, for example, get to the same place on the lunar poles and both want to mine ice there. And of course, this would be a big question for anyone who wants to live in space as well. If you're coming from somewhere, like the US, say you've sold your home, you're benefited from property rights there, you've bought a ticket on a SpaceX space liner, and you've gone to space, suddenly you're living in a place with no property rights here, having to adapt to a new economic system. Which also leads to other questions like, okay, well what does that mean about if you don't have a job? Or the ability to pay for housing if you have to do that in space settlement? Because the fact that you can't strike out on your own and make a homestead, means that you also can't get evicted from a habitat and be able to just make do, camp in the woods or live under a bridge or some such. Housing is going to be a major issue. Poverty will be a major issue as well.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. Eviction is a death sentence on a space settlement.

Erika Nesvold: Yeah.

Casey Dreier: This book I've read last year, which I found very provocative and fascinating, was called The Dawn of Everything by David Wengrow and David Graeber. And they were looking at examinations of different ways in which human societies have organized in the past. And they had this really fascinating definition of freedom, what they called a primordial freedoms. And they defined them with three primordial freedoms, that all humans that they claim took for granted, it didn't even have to be stated until the modern agriculture basically hit. What really hit me, it was the freedom to move was their first definition of what being free was. Then they also had the freedom to disobey and the freedom to create one's own social relationships. And in a space settlement, I kept thinking about this definition of freedom. And to what your point, in that there is a lot of some pseudo libertarian utopianism talking about independent, self-sufficient, self-organizing groups of people or individuals. But you cannot leave when you're in a space settlement. You are stuck there. You have no freedom of movement. Because you, as an individual, cannot mine and then filter out the ore and then push into metal and then develop plastics from earth and then create air from nothing, and then move into your own bubble the next valley over on Mars. You are fundamentally limited there. And I just feel like these space settlements will be anything but free as long as, again, as they're in this resource scarcity mode. And just, again, fundamentally unable to just strike out and move anywhere else. And that's where, again, these historical analogies seem to completely crumble in a lot of these analyses of you can't just strike out west and claim, and this is, again, romantic idea, claim your own land and live how you want to live because the air's not free. You don't even have that with you, much less everything else. Some of these places may actually not be very nice places to live, at least at first.

Erika Nesvold: Yeah, that's certainly a risk. And an astrobiologist named Charles Cockle has edited three, I think, different volumes that relate to this idea of dissent and liberty in space, and what that would look like. And a lot of those chapters point out exactly what you're talking about. If the air that you breathe is centrally controlled by, worst case, your employer in a privatized space settlement, how do you go on strike or protest against your employer? Conversely, how do you make sure that people striking or protesting aren't sabotaging and damaging vital systems? So there's just so many more threats because everyone will be so dependent on each other. On the other hand, I, optimist, remember, I think it'll be interesting to see, because humans are social creatures, we're good at forming communities, and possibly we'll find ways to evolve our cultures such that interdependence is strengthened and strengthens our social bonds. But it certainly could go either way. And some people have suggested we specifically designed for that. That we emphasize and prioritize travel between habitats, for example. That we make sure everyone has a fundamental right to a space suit and a rover, for example, so that you can just get up and leave. Because, yeah, a lot of people are worried about that exact lack of freedom.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. This is where we have to point out that to really examine these issues of who controls air and labor relations is to review the ultimate movie and space ethics, Total Recall.

Erika Nesvold: I've watched Total Recall because I was doing this work and people kept mentioning it. Yeah.

Casey Dreier: Yes. It's the subtle and nuanced depiction of this very issue. Highly recommend it.

Erika Nesvold: That'll give you Nightmares.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. Another chapter I found really fascinating, it was just on crime and punishment, and the challenges of how we enforce laws. What are some of those challenges about enforcement and law in a space settlement?

Erika Nesvold: This chapter and working on this chapter has definitely had the most impact on me and was the most educational for me. Because the first question is, "How would you build a carbon copy of America's prison system in space, and how practical would that be?" Because a lot of Americans, I say this from experience, tend to think we have the best system. That's just what we're taught growing up. And so obviously we'd want to use the best system in space, and that's a system with prisons and cops. So let's think about how that would work in space. And the answer is, it would be terrible. First you have to build the prison. And as you've been mentioning, there's a lot of, not just resource scarcity, but labor scarcity. So you need someone who's not too busy, recycling the water and growing crops to build this extra facility that's got to have its own heat and air and pressure and such. And then you're going to have to have some kind of criminal justice system that identifies and then judges somehow and convicts people. And then you're going to put them into this facility. Someone perhaps needs to guard them that's more labor lost. You've lost the labor of the people you've put in prison, unless you decide you want to force them to work, and then that's a whole other set of problems that we're also struggling with here on earth today of unpaid prison labor.

Casey Dreier: I liked your line, "Congratulations, you've just reinvented slavery for the top [inaudible 00:51:55]."

Erika Nesvold: So yeah, it would be extremely impractical and inhumane, frankly. And that made me start to think, well wait, well, how different is that from our prison system on earth today? And it turns out not too different. There's a ton of criticisms on earth. All of those things will just be exacerbated in space. And so this is where you need to question your assumptions. And my basic assumption was, "Well, prison system, that's how you deal with crime, right?" There's so many other ways to deal with crime, especially in smaller communities, like the ones that will be starting within a space settlement. Plenty of other cultures or other countries have addressed crime and deviant behavior, I don't love the word deviant, but antisocial kind of behavior in ways that don't require a police system and a carceral system. And this really changed my view, talking prison abolitionists about other ways we could handle this. Because there's a lot of ideas out there, there's a whole field of transformative justice that works on alternatives to the prison system in the US and around the world today. And it made me realize that we don't have any police or prisons in space today. And so if we do at some point in the future, it will be because we decided to take them there. And we don't have to decide that way, we can figure out some other way to handle violent or otherwise antisocial behavior.

Casey Dreier: This is what I find so fascinating about this topic of space ethics. Sometimes space is so crystallizing about reevaluating our own assumptions and what we inherit culturally and socially and our expectations here on earth. That to see them through a space lens provides us or enables us to challenge the assumptions that we do have or to reevaluate them. And even if we go back to where we started or if we come to place somewhere new, space really gave us the ability to sit back and analyze them in a way that we never would've had. The whole concept and consequences of whether you have a restorative justice system or the fact that you take a person out of the labor pool or that consequences for the most minor infraction or the functional equivalent of the death penalty, you are in a really tough situation in these places. I mean, in that case, is there an analog anywhere on earth? I mean, what happens with is there petty theft in Antarctica? I mean, they don't throw people outside at the Antarctic base stations. But again, those are a highly selected, rotating group of people, right? Did you find anything even useful for this? This is so out of the league of what we're used to here.

Erika Nesvold: So I did include a story about Antarctica. There was a stabbing in Antarctica in the early days, in a Russian or Soviet program, I think. One worker stabbed another worker. And they ended up having to send the assailant back to St. Petersburg in order to stand trial, because they didn't have a system down there. And I'm not sure whether it happened in winter or not, but it takes time to do that. And in the meantime, they had to put him somewhere. I'm pretty sure he surrendered in that case and said there wasn't an issue of determining guilt. There's also another slight analog here is the way that these things are handled on ships. Because again, you can't just banish someone from a ship without kicking them overboard. Historically, the captain has been the one who's responsible for determining how justice is going to be done, which is also not necessarily the best system and-

Casey Dreier: Not famously restorative.

Erika Nesvold: Yes. Precisely. And very much at the whim of the captain. I think it's possible that if we're not thinking things out ahead of time, we'll probably end up evolving space settlement justice systems from a ship based system in some way, because the space settlers will get to their settlement on a ship. They'll spend potentially years on a ship getting there and they'll be operating in a different hierarchy and structure on the ship potentially than they will on the space settlement. And maybe they'll just keep that system around. Captain's in charge, captain makes a decision. We have a brig. I think if we don't think things out ahead of time, we could end up just repeating a lot of those issues from the past.

Casey Dreier: And you make a point that a lot of the decisions we start with can really influence the long-term culture of a place. Particularly in highly isolated, remote cultures and institutions, you can have a strong initial conditions. Will really echo down the line for that. I want to touch on one more area in the time that we have left. And this is another big one that, again, we'll emphasize you talking much greater length about all these topics in your book. But that's the issue of families and reproduction. And again, really touched on things I hadn't had the opportunity to think about or hadn't gone into the depths. And again, really difficult issues here. Starting with the idea if you're going to a space settlement, do you even let infertile people participate in that system?

Erika Nesvold: Yeah. So this is another case where we're really going to have to balance the needs of the society against the rights of an individual, which is already issues we're dealing with in reproductive rights today. And so many tough questions come out of the idea that space settlements might be living at such... so much on the razor-thin edge of survivability that they might need to very carefully control their population. And population control, notoriously and historically leads to a lot of terrible practices. And in the first place, yeah, it could certainly affect the sort of selection issues that we were talking about in the first place. Suppose that you're going to need a certain reproductive rate in the space settlement that you're planning. Is that going to affect how you choose your initial set of settlers or your initial population? Are you going to, for example, exclude people who are unable or uninterested in basic heterosexual reproduction? Again, maybe you make those decisions in your first generation, but then at some point you have a second generation, you can't necessarily make the same decision. So eventually you have to figure out what you're going to do to either encourage people to have more children or to encourage them to have fewer children. And we've seen both on earth, historically try to be addressed by governments and lead to things like forced sterilizations, forced abortions, illegal abortions, or in France and Russia after World War I, when they had a lot of a really lowered population from the war. They both did things like outlaw, not just abortions, but even contraception, even just talking about contraception. And so you can end up in these situations where the community as a whole, the leadership just really drills down into people's individual bodily autonomy. And if you're talking about the existence of the community itself, it can lead people to make really horrific decisions.

Casey Dreier: Well, and you bring up this really important point of coercion. If you're a woman who is part of this space settlement, are you pressured or expected to procreate constantly? How often? By whom? And will that change over time? And there's the really kind of unpleasant implications with-

Erika Nesvold: Even in the absence of legal requirements to reproduce, there's such a spectrum of cultural pressure. Looking the other way and do we want to live in a society like that?

Casey Dreier: Yeah, that really struck me. That really changed some of my... Not that I thought about it too much, but that was a really important part about how do you make sure people are still... Again, this goes back to these essence of freedom, right? And this will being able to disobey and to feel like you're comfortable or not participate in that system. I would also note too, that the delicacy of having to precisely plan for population growth is so difficult, because again, of can you have enough space to accommodate growing human population? If it grows too fast, you're going to have nowhere to put people. If it doesn't grow fast enough, you don't have the resources, the labor to put in to maintain what you have. And who is controlling this? And then is everyone biologically considered machines by whatever system is in place? And then again, you get into these really challenging situations that are not, again, very pleasant to exist in from an individual standpoint. And again, the opposite of this libertarian ideal of total freedom.

Erika Nesvold: And these are the sort of questions that make you step back and go, "Why are we even doing this?" Right? I mean, is the point to just churn out as many human baby making machines in space as possible? Because we could make some really terrible decisions in order to achieve that goal. Or is this point to create communities that are going to thrive where people are going to be happy, and perhaps have a higher risk of failure? And that's, oh man, that is big ethics type questions that we need to figure out before we start making these decisions.

Casey Dreier: Well, and one more point that you also touch on in the book is what about the choice of the children born into a space settlement? Because it's very unlikely they would maybe even ever get to go back to earth. And they're born into what is essentially a prison in the fact that they cannot go outside ever. They'll never feel a breeze. Maybe they'll see some hydroponic plants. But they have no fundamental freedom. But again, particularly if they can't go back to earth, they're born into this constraints. And no one ever asked them if that's the life that they wanted for themselves. And so there is, to me, that's a big ethical quandary as well.

Erika Nesvold: And potentially, initially, the ones that are born first will be part of medical research that they never consented to be a part of. Because we don't yet know whether it's even possible to reproduce healthy children in space.

Casey Dreier: Excellent point too. It has not yet been a test that NASA has done on the internet [inaudible 01:01:27].

Erika Nesvold: For good ethical reasons, yeah.

Casey Dreier: For very good ethical reasons. All right. So again, Erika, I go back to this at the beginning. Is it still... Can I just ask you this question again? Is it ethical just at all to settle space? I start getting tied around in knots once we start drilling down into this, and I just don't know how to resolve this.

Erika Nesvold: The thing is that all of these questions, the fact that we keep referring to parallel issues on earth, means that all of these questions are worth asking whether we go to space or not. Because the goal of all of them is to figure out how to make the future better for our descendants than it is today. And so I think that we have to think about these issues no matter what. And if we figure out good solutions to them, then yeah, why not go to space? So I think that we should, while other people or even the same people are working out the technical and economical challenges of going to space, they're going to be doing that anyway. Let's spend time, this time, the conversations we're having right now, thinking about these problems, initially being really intimidated by them, and then finding experts in their terrestrial parallels and coming up with solutions in this sci-fi setting that we would not otherwise consider on earth. Like you were saying before, it really lets you have this psychological flexibility to imagine possibilities that we couldn't when we were just thinking about earth.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, it strikes me, just coming back to maybe the solution has to be to some degree abundance. Can we find a way that if there's going to be a settlement, that we have to have some way to maintain standards of living, physical resources? Which is somewhat ironic, because then the answer goes all the way back from an ethics to a technological question. But reading your book struck me, it's like the technology challenge, that's the easy one.

Erika Nesvold: That's the easy part.

Casey Dreier: Compared to some of these. And so maybe that helped. I mean, all of these things that they're, a lot of them are constrained by limitations. Maybe lifting that constraint or finding ways to do that in advance. But at the same time, we're starting to see people pushing forward and doing this anyway. So I guess as humans generally do, we muddle through it. But again, I think the opportunity to think about it now and maybe here at the end for listeners or people who are more interested in this, besides reading your book, what are the things that we can do as individuals but also as a society in the near term, to kind of help make sure this is a part of the thought going forward as we plan this next step in human exploration and existence?

Erika Nesvold: Number one, as an industry and a field of both private space flight industry and the space science field, which is where I come from, we need to recognize our lack of expertise in a lot of these, the social science side of things. It's very easy for us to fall into the trap of thinking we're the smartest people in the room. We're not. We need to have conversations across disciplines, I think that's extremely important. And enjoyable. I mean, just learning about all these issues was fantastic for me. And then we also need to diversify our conversations cross culturally. So we need to be talking to people around the world about space, about how they think we should live in space, about whether they think that we as humanity should go into space. And I think all of those conversations will lead to both questions and solutions that you and I can't come up with just sitting here for an hour, as much as we try.

Casey Dreier: But we're on a podcast. As long as we speak confidently about this. But well, again, Dr. Erika Nesvold, really appreciate you being here. You are an astrophysicist and author of the book that I really enjoyed Off-Earth: Ethical Questions and Quandaries for Living in Outer Space. Which is available as of March 7th on all major publication outlets, from the look of it. Highly recommend you pick up the book. You've also produced, and I have recommend people listen to this too, and hosted the limited podcast series, Making New Worlds. And are the co-founder of the JustSpace Alliance, a nonprofit with a mission to advocate for a more inclusive and ethical future in space. Dr. Nesvold, thank you for being here today.

Erika Nesvold: Thank you very much, Casey.

Casey Dreier: That was my interview with Erika Nesvold. Again, you can find her book. We linked to it on the show notes, Off-Earth: Ethical Questions and Quandaries for Living in Outer Space. Really enjoyed reading it. I recommend anyone who really thinks about the future of space settlement and exploration, it's something to think about and grapple with yourself. So it's a great book. Jack, I don't know if you've ever had the chance to talk about space philosophy or space ethics, not necessarily in the realm of what we do directly, but certainly part of the discussion broadly for space. Was that any part of your formal education when you were focusing on space in your master's work or anything undergrad work like that?

Jack Kiraly: Yes. Actually in my grad program, which I'm a graduate of American University, yes, it's a real school here in Washington DC. I had a class on commercial space flight and the future of the human space flight industry. And this was with Dr. Howard McCurdy, out of American University. And one of the things that we actually talked often about, both in discussions about the research that we were doing and sort of off the cuff conversations with Dr. McCurdy, was in sort of the intentionality that we need to bring to settle space one peacefully. Right? We have the Outer Space Treaty, signed 1967, that really governs a lot of our activities in space still. And that peaceful use of outer space is, as you said, one of those baseline expectations of the way that we explore space. But it's something that we need to revisit every time that we do anything new in space, is make sure that we're coming at it from the place of peace. But even outside of that, as the use of space grows, and specifically within the commercial space flight industry, utilizing space in a open and transparent way, taking a look at the ethics of the use of space is something that the US government, the international governments, the international bodies of governments are constantly talking about. So it's something that is sort of intrinsic in the discussion of space policy, is how you use space to the betterment of humankind more broadly. As well as your nation or your stakeholders or your people, or whatever perspective you're coming at it from. That ethical question, how you use space to the best benefit of all who want to use space is an important part of space policy.

Casey Dreier: That's good to hear. I mean, I'm happy to hear as someone who never had necessarily a lot of formal training. Studying space, you get to evaluate and analyze aspects of the human condition through these unique prisms. And it's something, and that again, I think is really important and valuable, but also just reminds me why the technology then becomes the simple part in some of these discussions. Right? Once you open up the discussions of ethics and being an self-organization and society, those become, to me, much thornier, more difficult to resolve, ongoing issues. And the tech stuff becomes more straightforward as it comes.

Jack Kiraly: Well, there's no rocket equation for human interaction.

Casey Dreier: Right. Yeah.

Jack Kiraly: Right? So it takes that intentionality, it takes coming to the table with the best intentions. It comes from a place of wanting to use space for the betterment of all who want to use space, not just who can get there first and who can get there fastest and who can get there cheapest. It's how you can utilize space not just as a platform, but as a medium to achieve your goals.

Casey Dreier: Well, if you want to see space as a medium to achieve your goals, I highly recommend joining The Planetary Society to find fellow space advocates like me, like Jack, and tens of thousands of members around the world who pool their resources together to allow us to work together to make the future in space something aligned with what we want to see. To be science driven, curiosity driven, open to everybody, and fundamentally, I'd say stirring to the human soul. And so if you're interested, if you like the show, if you like what The Planetary Society does and you haven't joined us as a membership, I can't emphasize enough, everything we do at the organization depends on individuals. We don't have huge corporate donors, we don't take government money, we exist, we literally live and die as an organization on the generosity and commitment of our members. So if you want to be one of them, please go to planetary.org/membership and consider joining us today. And making that commitment and helping us do shows like this, helping us talk about issues like this. And helping me and Jack do that kind of advocacy work and be in the room when these decisions are being made about the future of space exploration. Or if you just like the show and you can't commit financially, totally fine. Please though, consider rating us positively. Sharing this show with others. Review us on Apple Podcast or wherever you get your podcast. Just help get the word out about this show. We'd really appreciate it. It helps us be found by others. And where we can begin build this broad social engagement and fascination and excitement about our future in space. So until next month, Jack, thank you for joining me, we will check in with the budget in April episode. And until then everybody, ad astra.

Jack Kiraly: Thank you, Casey. Ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth