Planetary Radio • Nov 04, 2022

Space Policy Edition Bonus: Q&A with Casey Dreier and Bill Nye

On This Episode

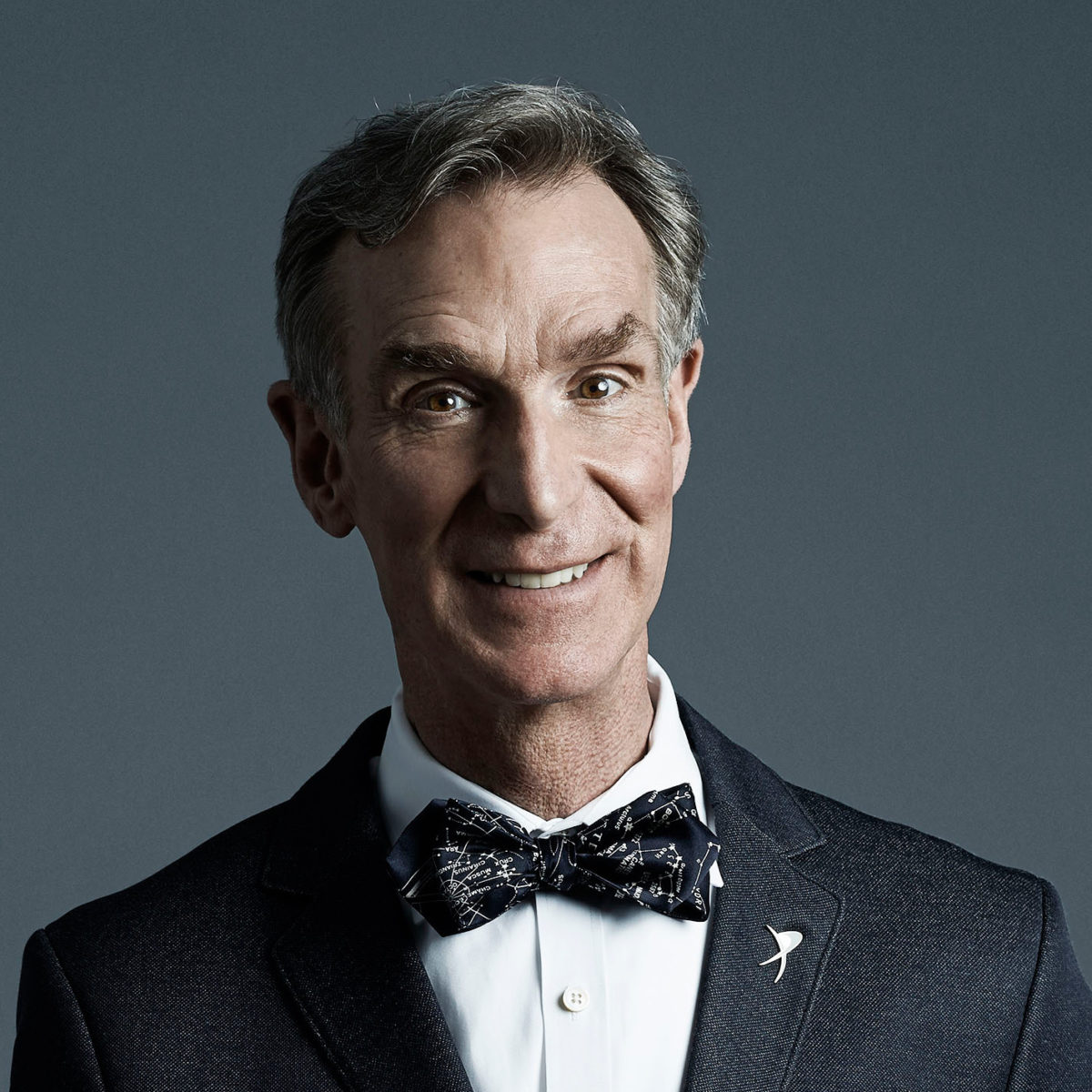

Bill Nye

Chief Executive Officer for The Planetary Society

Casey Dreier

Chief of Space Policy for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

While we wait for the result of the upcoming U.S. midterm elections, enjoy this special bonus episode of Space Policy Edition featuring The Planetary Society's Chief Advocate and CEO answering dozens of space policy questions submitted by our members. These twice-annual policy briefings are moderated by Mat Kaplan, and are an exclusive benefit for Planetary Society members. Want to submit questions next time? Join us at planetary.org/join Our regular Space Policy Edition episode will be published next Friday, November 11, after the U.S. midterm elections.

October 2022 Space Policy and Advocacy Update The Planetary Society's semi-annual space policy and advocacy webcast returned on October 28, 2022 with live reports from Society CEO Bill Nye and our chief advocate Casey Dreier. Moderator Mat Kaplan of Planetary Radio shared the penetrating questions of members and donors throughout the show. You'll get the latest on the challenges and opportunities ahead for the exploration of our Solar System and beyond. You'll also hear how we continue to make your voice heard in Washington D.C.

Transcript

Casey Dreier: Hi, this is Casey Dreier, the chief advocate here at The Planetary Society. This is a special bonus episode of Space Policy Edition. We are doing the regular episode delayed until next week after the upcoming U.S. midterm elections that will determine the control of both the House and Senate. Next week, we will have opportunities to react to the outcome of those elections and to really dive into the implications for space science and exploration. Until then, we have a special treat for you. I recently hosted along with my colleagues, Mat Kaplan, and my boss, Bill Nye, a special members only webinar that was briefing and answering questions on all manner of space policy issues asked by Planetary Society members. This is a special treat for members of The Planetary Society that we do twice a year. If you want to ask me questions and my boss questions and really challenge us and dive down onto all sorts of space policy issues, you can join us by being a member of The Planetary Society. Join us at planetary.org/join to be able to participate in these with us. But for anyone here who's listening or for members who may have missed it, we will replay the entire question and answer period with me, Bill Nye, and Mat Kaplan right now. So enjoy these and we will see you next week to examine the outcome of the recent congressional elections here in the United States.

Mat Kaplan: Welcome, everyone, to this latest edition of the update on space policy that we provide to all of you, our loyal members and supporters. We are so glad that you were able to join us here once again. Of course, we welcome those of you who aren't able to join us live. We heard from a lot of you who can't actually be here with as we speak on... What is this? Friday? Friday, October 28th, but are catching us sometime after the fact. We welcome and we thank all of you. I'm Mat Kaplan, the host for another couple of months of Planetary Radio before my wonderful colleague Sarah Al-Ahmed takes over. I am thrilled about that and I'm also thrilled that I'll be continuing my work with The Planetary Society. Joining me, of course, the two most important people in the cosmos about space policy and advocacy, the CEO of The Planetary Society, our boss, Bill Nye, the space and science guy, you see him there on your screen, I hope, and the chief advocate and space policy advisor for The Planetary Society, that's Casey Dreier in his... Oh my goodness, I just realized, Casey, he's wearing his formula. I love that shirt.

Casey Dreier: Drake equation T-shirt, my new favorite T-shirt.

Mat Kaplan: There it is. You make it from one end to the other and you find out we're not alone in the universe. Bill, I'm going to go to you in a moment for some introductory comments, but we already have received a ton of terrific questions from those of you who submitted them before the show started. Now, those of you who want to get into question during the show, we're going to save as much time as possible for this, get through everything else up front very quickly, we hope. Be sure to submit those in the Q&A area that you see in GoTo Meeting. If you see a chat area, that's fine, but don't put your questions there, and we will try to get to as many of these as possible. I'm going to start with not questions, but a couple of lovely comments that we got from some folks. Rosemary Hileman in Illinois is a charter member, "So proud of all this organization has done and continues to do since its founding." Thank you so much, Rosemary, for your many years of support. This one from Vicki Goin in Arizona, "I was very young when I joined Sagan's space group. Now, at 63, many years later, LOL, I have had the chance to join up again with The Planetary Society. Now I get to share it with my grandkids and I'm very excited about that. Keep up the amazing work." Bill, take it away.

Bill Nye: Greetings, everyone. Thank you so much for taking the time on a Friday. We really appreciate it. Now, of course, you're joining because you're passionate about The Planetary Society and planetary exploration and so are we, but something that we can do is advocate and we are the... I'll claim that's not extraordinary, we're the best in the world at advocating for planetary science missions. We are focused and effective, and that's because of your support. So, thank you all very much. We can hire people like Casey, who's let's go with passionate, some might say nerdish, nerdy about space policy and he can answer questions that any of you may have in a very thoughtful way because unlike the rest of us, as I understand it, he's read all the bills. Now, we are living at another extraordinary time and that's why I'm really glad you all are managed to tune in today because the midterm elections are coming up here in the United States. Whether or not you live in the United States or anywhere else in the world, these elections are going to create change in the US Congress, which will create change in space exploration around the world, not just because of the leadership of NASA. NASA is the biggest space agency in the world, at least right now, but also because of all the investments in launches and spacecraft that affect everyone everywhere. So, thank you all for taking the time today and thank you yet again, thank you so much for your support. Back to you, Mat.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, Bill. Casey, we're going to jump to you for one of the questions that was asked most frequently by the folks who got them in ahead of time. But even before I get to that question, here's one that just came in from Mel Powell, member and regular Planetary Radio listener, most important question we'll get today, "Where did Casey get the Drake T-shirt?"

Bill Nye: Oh, man. Hey. Hey, Casey, take it.

Casey Dreier: That's a wonderful question. I've had multiple people ask me about this shirt. I'm happy to say you can find it on Chop Shop, which is by Thomas Romer, who I remember designed The Planetary Society's member T-shirt. His website's online. You can buy this. This just came out of a few months ago and it's a wonderful shirt. Great conversation starter, but I believe chopshop.com. We can send a link out.

Mat Kaplan: Chopshopstore.com.

Casey Dreier: Chopshopstore.com.

Bill Nye: It leads to planetary.org, you guys. We have a great deal with Thomas. He's our guy. I, as I've often said, do not need any more T-shirts, but I also bought the Drake equation T-shirt.

Casey Dreier: My wife encourages me to expand my T-shirt repertoire beyond that of space as a topic, but I could not pass up the Drake equation here. The funny thing is, this is an interesting reminder, Bill, to your point about maybe my well-read aspect of space policy and history and opinionated aspects of it, I thought this would be a great conversation starter and most people, I think, just blanket out. I keep going to parties expecting people to say, "Hey, what's that equation on your shirt?" And then I can go into the Drake equation and like, "Oh, what's L?" We can debate some of the terms. What's the role of how many basic lab examples of the genesis of life lead to intelligent life and civilization? We're measuring it the right way. But I think people just see the equation and it's the last thing they ever want to talk about. I think math is not a common party discussion unfortunately, but I tried.

Bill Nye: That is so weird.

Casey Dreier: Maybe I'm going to the wrong parties.

Bill Nye: What parties are you going to?

Casey Dreier: Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: Mel says he looked at Chop Shop. Mel, you got to look harder because I know that's where that shirt is, but-

Bill Nye: Oh yeah, he just issued it though, or Thomas just issued it. Everybody, this really is an extraordinary idea. As I like to say, I'm so old. How old are you? I was in school when Frank Drake was walking around. I saw him in the hallway. We interviewed him last year not too long before his death. He has just a great guy. As I have said for many years as science educator, it has been shown that algebra is the single most reliable indicator of whether or not somebody pursues a career in technical field. It is very reasonable that it is also cause and effect. That is to say people who learn to think abstractly about numbers, algebra, learned to think abstractly about all sorts of things. So Frank Drake had this cool idea, let us use algebra to address this deep, deep question, are we alone in the universe? Back to you, Mat.

Mat Kaplan: Let's save a couple of minutes at the end for what this has reminded me of and that is how much we're looking forward to The Planetary Academy, but we'll do that a little bit later. Casey, back to you. Like I said, I'm going to start with something that it was maybe number two or three in the topics that were brought up by people ahead of time. It's the Day of Action. We have a lot of people out there watching right now who have participated in the past or want to participate next time. Got a couple of young people to read to you. Heidi Jacobs, she's 13 years old, she goes to Westfield Friends School in New Jersey. She's curious to know what kinds of policies around mining on asteroids or on Mars, how that's going to be done. But the one I really want to get to now is will the Day of Action be in person, or virtual, or undecided? Before you answer that one from Carolyn Condit, who is 17 years old in Washington, state of Washington, is there an age requirement for the Day of Action? She has dreamed of attending since becoming a member. So, Casey, what's ahead of us?

Casey Dreier: Great questions. Yes, it's been a little longer from our announcement of the Day of Action for next year. One of the things we've had to work with is that we have two uncertainties that have impacted what we consider to be the quality of your experience for an in-person Day of Action. The first is ongoing COVID restrictions. It's not so much a mandated top-down restriction anymore as it is that many offices are still voluntarily not doing in-person meetings, up to a quarter of them, and will only do in virtual meetings even if you are right outside the door. So that has been a consideration. And then after January 6th, there's been a severe change in security conditions in the Capitol buildings. For those of you who've been to the congressional offices in the past, that prior to January 6th had been this beautifully open accessible place. You go through a metal detector and then you can wander around the congressional offices, drop into any office, say hello, meet with your representatives, meet with their staff. But since January 6th, you need an actual escort by a staff member or security officer to move between every office. From the people that we've talked to who've been trying to do in-person events, frequently staff members forget or don't show up. They leave you stranded at security lines which are much, much longer, then mixed with the COVID concerns. You're just packed into these little security areas waiting for people who may or may not come. So both of those have really degraded the quality of in-person experience. So that's why we didn't do it this year in-person. We did virtual. For next year, because we're still not sure, what we ended up deciding and an email just went out this morning to every past participant of the Day of Action is that we're going to do an in-person Day of Action, but in September of next year, so later than usual, after Congress returns from their summer break. That's a great time to come and help focus on getting the budget across the finish line. This is exactly when they start wrapping that up. The fiscal year deadline will be looming in October. So that will be a wonderful time to come and really focus on that. The other opportunity that this gives us is we have, as Bill mentioned, midterm elections, where very likely or at least toss up, there's a significant possibility that there'll be a party change in control of Congress. That means that there'll be new people in leadership positions of the key science committees that we're really going to be focused on and there's going to be new people entering and people leaving and departing from Congress either retiring or losing their reelections. That means there's going to be a shuffle in the first couple of months before we really know who are the key people on the science committees to really be engaging with, that plus more time to allow the security situation to return to normal, and we think September is a really good time to do that. So we haven't decided on an exact date. It will be after Labor Day and we're working to probably some time between that and the prior to the 15th, but we'll send you an email as soon as we have an exact date, once we have a congressional calendar published by the leadership in January of next year. In the meantime-

Bill Nye: The most beautiful time of the year in Washington D.C.

Casey Dreier: Yes, it snows a lot less in September than March or February, so we have that.

Bill Nye: Also, it's just so pleasant, so with that aside.

Casey Dreier: And so, in the meantime, in the spring, we're going to do a Day of Action Lite. So we're going to have a focused couple of days is centered around member actions communicating with Congress, specifically tied to the appropriations letters and request period that a lot of you are familiar with, where you can go and ask your member of Congress to submit a formal letter to appropriations committee for key NASA items and issues. So this is a great time. This probably be late February, early March, where we'll organize. We'll have some online discussions like this. It won't be person-to-person meetings, but we will be doing phone calls, training letter writing campaigns and an organized multi-day effort around that, so kind of a Day of Action Lite. So for people who can't travel, are worried about affording travel, we have options that we're really going to push in terms of a positive virtual experience. So we're going to try a new system next year and we'll see if that works. It's likely we'll probably switch back to an in-person Day of Action in 2025 or 2024, I should say, earlier in the year, but we'll see once the both security and COVID situation normalize. Because at the end of the day, the long way of answering this is that we want your experience in Washington D.C., if you're going to go all the way out there on your own funding and spend the time, take time off of work and do the work, you want to have a positive experience. You want to walk out of there or fly back or drive back knowing you had that face-to-face time, knowing that you made that real difference. Until we really feel confident about that, we did not want to have an in-person Day of Action. So, September next year.

Bill Nye: Everybody on the call, imagine a large fraction if you've been to a Day of Action, it's so satisfying when you look your representatives in the eye and give them an earful.

Mat Kaplan: I've been out there. I've been in offices with you Bill, and it is a wonderful experience and it gives you an increased sense of respect for what they are trying to do in Washington, which is-

Bill Nye: Even if you leave, even if you don't like the people, you get respect for what they're trying to do.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. We can move on from there. At midterms, already mentioned a couple of times during the conversation, and we did get a few questions about that. Here's one that came from Mark Saxby in Florida. "What impacts do you folks think that the midterm elections will have on space policy moving forward?" And then he adds, "NASA talked up planetary defense in the wake of the dark success, but NEO Surveyor was reduced in both the FY22 and FY23 budgets. What's next for NEO Surveyor? Did the CHIPS and Science Act help enough to keep it on track?" A lot of ground to cover there, Casey.

Casey Dreier: Indeed. Well, let's talk about the midterm elections first because that's obviously a big near-term thing. In terms of space parlance, we can consider this the event a political event horizon, where the projecting off into the future just disappears into this black hole of uncertainty. We have a very close looking by using poll. So I've actually put together a internal tracking document here, where we're pulling data from the website FiveThirtyEight, which is an aggregator and analysis tool for integrating national and local polling and other historical trends. They're predicting, very unhelpfully in a way, basically a 50/50 toss up for the Senate based on Republican or democratic control and an 80/20 likelihood of Republican control of the House of Representatives come next year. So then we also use their race by race polling conglomerate data and we look at every member who is sitting in the key committees that we care about. Those committees are the two appropriations committees and one in the House, one in the Senate. That's what funds NASA, the CJSF subcommittee. And then we also look at the members of the space subcommittees, the authorization and oversight committees, one in the House, one in the Senate, and we can look at which of those members are likely to be replaced or lose their elections, which ones are retiring and which ones are going to be potentially moving on to other areas. So as a quick reminder, the entire House of Representatives, all 435 members, is up for reelection come November 8th. Only one-third of the Senate is at any given election. So we have about 33 races. Based on that, we are looking at of the key committees that we really care about, that looks to be very likely to be minimum of six seat changes, particularly Charlie Crist, who is actually retired and running for governor of Florida is likely to be replaced by a Republican, Anna Paulina Luna. We have a couple retirements on the House space subcommittee that are being retired and probably replaced by members of the same party. The two biggest changes that may have the broadest impact will be the two leaders of the full of Senate Appropriations Committee, Patrick Leahy and Richard Shelby. Richard Shelby, of course from, Alabama, longtime powerful broker and appropriator of Marshall Space Flight Center, the SLS and other key programs coming through Alabama. He's retiring and he will be replaced almost certainly by Katie Brit, who's a fellow Republican. Patrick Leahy, not as strong of a supporter of space, will be retiring and almost certainly be replaced by a fellow Democrat, Peter Welch. The problem is when these people are replaced, they don't just assume the prior leadership role of those committees, right? The new people come in at the bottom of the proverbial hierarchy and start working their way up. And so, the people who leave as leadership will be replaced by the leaders. That's called the Committee Chair Shuffle. And so, we don't exactly know who's going to be coming in at these levels. In the terms of the Senate Appropriations, no major changes there. People look to be winning their reelections. We don't expect any major changes. The one change on Senate space committee is Raphael Warnock from Georgia, who's running a very close race there and may or may not win. Like I said, everyone else is pretty solid to be replaced to win their reelections. So again, we're looking at six for sure changes based on polling and retirements. And then based on close races, we may see some mix up. But again, the space subcommittee tends to be an area where even incoming people may or may not choose to participate in, right? If Warnock loses and the Republican comes in to replace him, he may choose not to serve on the space subcommitte, right? So we won't really know until usually the end of February by the time all of this sorts out. Again, the fundamental change though, of course, will be if leadership changes the party of controlled changes of either the House or Senate or both, we'll have obviously different political dynamic, right? We'll be flipping from a situation where the presidency is supported by members controlling the Congress of his own party to a much more politically contentious division and dynamic, where the incoming, if the Republicans win, House or Senate or both, they will be politically motivated and consider themselves to have a political mandate to oppose the political goals of Joe Biden more forcefully and stronger than they were able to do as the minority. That could express itself in many, many ways. We don't exactly know how it's going to work out, but if we go back to a period of comparison, I'd say 2010, with the tea party control of Congress under Obama, I expect it very difficult to even get the fundamental budgeting passed on a timely period, at least for a few years. So I would expect a relatively contentious and relatively uncertain period of politicking even based on past comparisons. And that's something that for NASA fans like us, we're going to have to fundamentally just ride the wave, make the best case that we can. Usually, again, NASA is not the deciding part. No one is against NASA for the most part, but will it rise to the top? Will it be enough to broker compromise? Will it be enough to create outcomes that help NASA or just will there be bad outcomes that inadvertently hurt it? We'll just have to do the best case that we can. It's going to be a relatively, again, dynamic and probably somewhat divisive, at least at first political dynamic that probably will even bid out over time if indeed Republicans capture one or both houses of Congress.

Mat Kaplan: Casey, that is right at the core of what we worked with, what you work with in particular at The Planetary Society. Man, we won't get any more focused on what this little webcast is supposed to be about. You addressed this back. You very much addressed it. Bob Weir in North Carolina has the concern that you've implied about. If we see Congress become more conservative and let's say that the Republicans also gain control of the Senate and we see Republicans following through on concern about the national debt, how much danger would there be that NASA's budget could end up being cut?

Casey Dreier: Yeah. I mean, obviously, that's a big concern. Domestic discretionary spending where NASA's pot of money comes from classically under Republican control has been under more scrutiny. I should note though that NASA generally does very well, all things considered under Republican control in Congress. Last year, under Democratic control, NASA saw it's first decrease from draft bill language to final appropriations in 10 years in terms of its over... It lost a few percent shaved off at the end and that was because of-

Mat Kaplan: Is that-

Casey Dreier: Sorry, Bill?

Bill Nye: No. Well, go ahead and finish. I have a follow-up, as they say.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. So it's not a guarantee, just because the-

Bill Nye: They say.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. So it's not a guarantee. Just because the government overall spends more money, NASA generally does better, but not always a guarantee. Trump budgets were relatively good to NASA compared to other domestic agencies and in their proposals. So it's a bit more of a complicated situation. The problem would come if we have a sequester like situation where there is some forced agreement of across the board budget cuts in discretionary spending. That's a possibility. We haven't seen that stated as a policy priority to note. Most of the discussion that we've seen has focused around mandatory spending, ie, the very big things, social security, Medicare, and things like funding for the support for Ukraine, which is actually what was the real cause between NASA's haircut last appropriation cycle as Congress was pulling money from other domestic issues to support Ukrainians. So again, we have a number of dynamic situations, and so it's not necessarily that we would see worse support for NASA. And in general, I'd say the incoming Republican party has been more supportive of spending in the past, but of course all's fair in politics. And so that may dramatically change or NASA again just may get caught up in it. So the key again I think for us is to keep making that case to everybody. And again, we've seen some very strong support from key Republicans in Congress, particularly on issues like planetary defense, human space flight and planetary exploration that we think are really great opportunities to keep educating an outreach to the new people who will be coming in next year.

Bill Nye: Now, Casey, is it a situation where let's say Republicans take over? Are they more inclined to focus on human exploration than planetary exploration?

Casey Dreier: I'd say it's hard to make that pure distinction. A lot of it has been in the past that we would take historical analogs from. There's a lot of idiosyncrasies based on individual interests wrapped up in that. The broad politics are that states that are generally represented by Republicans, particularly in the south, tend to have NASA centers that focus on human space flight, and therefore human space flight becomes a priority as a parochial interest. There's a lot of, I think we've seen historical symbolic national pride aspect of human space flight wrapped up into that. But also obviously a lot of Democrats share that too. And then a lot of NASA sciences are going to be at places that classically aren't represented by Republicans. They're represent by Democrats. So JPL in California, Goddard in Maryland. And so you have a slight political difference. It doesn't necessarily align with a partisan approach. It just happens to be what is represented by the party in control of those states. However, again, I think the transit align along that anyway. But again, we saw key members like John [inaudible 00:28:13] who was a Republican congressman from Texas, not with JPL in his district, was one of the most stellar and important supporters of planetary exploration probably ever. So I think the key is can you find people? The wonderful thing about what we do and when we go and talk to people is we're a break. We're a breath of fresh air. We're a highlight of their day when we come in to talk about exploration and what's under the ice in Europa, and what's out there and these grand opportunities to explore and unite people and to discover new things. No one's against that. And we come in offering solutions for these, not just presenting them as problems. And these are things that we can do, and that's the message that people can really buy into. And that's what we really try to educate people about, that these aren't partisan. It doesn't even make sense. It's almost a category error to describe planetary exploration as a partisan endeavor because there's no electoral votes to be won on Mars. You don't win them by going to Saturn. It's just a fundamental activity of a great nation, and I think that's something that really resonates with a lot of people.

Mat Kaplan: We can smoothly segue from this topic to another one, which was very near the top of the list among the concerns and questions that all of you sent to us ahead of the program. And this one comes from Jared Bieber in Delaware. By the way, I saw people from at least five continents who signed up for today's update. So welcome to all of you around the planet as well. Here's what Jared had to say. Are policy makers aware of the DART mission, of course the brilliantly successful double asteroid redirection test? How have they reacted to it? What is the planetary society's message to Congress in light of DART's success?

Casey Dreier: That's again a wonderful question, a great strategic way to think about this, which is exactly how we use these opportunities of a Mars landing or striking back against an asteroid to leverage that awareness, to engage and get people aware of there's so many more opportunities to do these types of things. So that's exactly the type of strategic thinking that we use. So for DART, yes, I think broadly there was a lot of great attention about it. I saw that the DART team was at the White House visiting the Office of Science and Technology policy, and you saw obviously the launch of the JWST. The scientific leadership of that team was at the White House briefing the president and the vice president directly about it. We saw a ton of interest, the president called JPL after Perseverance landed. So these are great opportunities to leverage interest. I'd say generally NASA has done a great job getting the word out about DART, and what we've been trying to do, and this is what we've been doing particularly in the media and key media partnerships for people who read the Washington Post and places like in POLITICO and Bloomberg News where we say, Look, we've done DART. DART is, my favorite analogy here is we just went through this pandemic, and pandemics are actually very similar in a very basic structural way to an asteroid strike. Both are rapidly geometrically growing levels of threat the less time that you have, depending orbital mechanics. Both of them are things that you can predict in advance or identify early and suppress saving you a ton of problems. Both are disasters that you can theoretically prevent by doing the research and technology development in advance. So DART's like the vaccine, DART is an example of how we stop an immediate threat coming toward us. But we need something like a testing regimen out there to look for and identify early threats so we have the vaccine ready to go. And that's how we talk about DART in terms of neo surveyor, where we need a spacecraft out there specifically designed to look for a lot of these things very quickly, very precisely, and give us a fuller understanding of what we're facing out there in order to leverage what we just learned with DART to protect the planet better. And it's a very clear message that we're able to draw between the two of them. And I think the ability, again, to slam something into an asteroid to change its orbit by as much as they did gave people a lot of confidence that hey, this is not something we have to live as this fatalistic approach to anymore. This is something that we can solve a problem, but we have to know it's out there in order to have a DART or equivalent ready to go in case we need it.

Bill Nye: We need a much bigger thing than a DART. But everybody, they got it going, literally shooting a bullet with a bullet. And it had to be autonomous because it was too far away to guide the speed of light. It had to separate the big one from the little one and then hit the little one. I was at APL you guys. I was in the fish ball they call it, they have a glass enclosure in the control room. And whom was I sitting right behind? My best buddy whom I'd never met before, Cal Ripkin Jr. And he's a famous baseball player, he's a loyal Marylander and he's a space enthusiast. And he was there supporting the mission, everybody was very happy to meet him. And there was an extraordinary success. And it goes to show you what you can do with the right team and the right leadership. And this mission I claim goes back as far as Barbara Mikulski who was a very space-pro senator, she recently retired. And she delivered a video message to the meeting or to the large assembly of people there. Leland Melvin was there, the astronaut, former head of NASA education. And everybody was very excited about it because it worked. The team was well led and they did it, if I can use the term, Casey, for only $325 million.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, that's a great term.

Bill Nye: Yeah, that's very inexpensive.

Casey Dreier: 300 for over six years, so it was a very affordable mission as those go. And one of the key things because there's no extended mission in DART if they succeed. You slam into it, that's the end of your spacecraft. So you don't have these ongoing costs extending out over time. And interesting, [inaudible 00:35:13], it's like throwing a pitch at another pitch and trying to hit the baseball in midair to move this into the baseball.

Bill Nye: Yeah, exactly. He said to me, "This mission doesn't have Eddie Murray at first base." For you baseball fans. Eddie Murray was just, he still is, this extraordinary player for the Orioles who played first base. And Cal Ripkin said he'd catch it no matter where you threw it. But back to you for crying out loud.

Mat Kaplan: Well, let me take us in a direction that I think you were headed in Casey anyway because it is another one that a lot of folks, we already heard Mark Saxby is concerned about neo surveyor. Because if we want to hit these things, baseball hitting a baseball or a bullet hitting a bullet, we got to find them and characterize them and track them. By the way, in that fishbowl with you at APL, Bill, I think were also Lilly Johnson, the planetary defense officer for NASA, and Kelly Fast who works with him there at the PDCO, the Planetary Defense Coordination Office. They'll be my guests on next week's planetary radio, and we will talk about all of this stuff. Casey, wither neo surveyor, I mean it has been a real rollercoaster, hasn't it?

Casey Dreier: It really has. Truly unfortunate decision by NASA and the White House to gut the mission the way that they propose to do this year, and there's just no coming back from that. In addition to the proposal to cut 75% of the funding for this fiscal year 23 that we're in now, they also what they call reprogrammed away roughly a quarter of its budget that it got from Congress in 2022. And so you can't design and build a mission that way. You can't just flick it on and off like a light switch. And so the mission is experiencing severe disruption, they'll have to lose chunks of their team and then think about how to hire them back. They've already procured flight hardware that is not rated to sit around for years and that they'll have to reprocure again. So it was just a truly boneheaded I think is the technical term move that we're pretty all frustrated by. And unfortunately NASA never gave, and through multiple media inquiries, not just from us but from Washington Post, Bloomberg News, POLITICO and other outlets and New York Times, there's just been no explanation. There's no good explanation of why they did it, which probably says that there is no good explanation. They just were the easiest thing to cut in terms of other missions facing some sort of arbitrary cost ceiling imposed on them most likely by the Office of Management and Budget. Okay, so that's the bad news. So what have we done? Well, we've done in a lot of ways a very good progress, made some very good progress on this mission. And we have stuck in the uncertainties of the congressional appropriations process now. We have two NASA appropriations bills, one from the Senate, one from the House, that's how it works. And then they have to merge them together, work out their differences, and then vote on them ideally in time for the new fiscal year. We're in the new fiscal year, we don't have a budget that's again, not uncommon in recent years. We're currently extended through December 16th, which hopefully will be enough time. And hopefully we'll be able to find some kind of common ground by then to pass a budget in December.

Bill Nye: Casey, when you say recent years, are you talking about the last 20 years?

Casey Dreier: Yeah, recent years being most of my adult lifetime or all of my [inaudible 00:38:58]. What's called regular order, it actually would be an interesting question about when regular order last happened for budgetary process, it's been a couple of decades.

Bill Nye: Couple of decades?

Casey Dreier: Yeah.

Bill Nye: Your tax [inaudible 00:39:11].

Casey Dreier: A couple of decades in a 250 year country. But in the Senate bill and in the house bill, both of those bills restore some money. And we're talking about some, we're talking in the order of $50 million, which doesn't get you all the way back to where they were, but it's substantial, it puts it close to a hundred million dollar mission down from where before it was, that 40 originally. The house gives more, the house gives 95 million, the Senate would give 80 million. We just submitted support letters to the congressional committees this last week, really pushing for that house number as they do this compromise discussion to really go with that one. And if that happens, that would be pretty much the only NASA science division, planetary science, which would see an increase from the original proposal to the final congressional outcome. So it's not everything we wanted, but in the context, the Congress has not been super generous this year about adding a lot of extra money to science missions. And so it's a really good progress given that context. It's been a very tough uphill battle this year for NASA science because there's so many, particularly in human space flight, Artemis, so many other areas that are really needing funding this year as well. Not to mention in the mega projects [inaudible 00:40:31] return, which is now this year larger than the entire heliophysics division at NASA, and then Europa Clipper, both of them are facing some COVID related cost delays. And of course Psyche, which is now going to be delayed and face cost overruns as well. So we're really hoping that that gets through. That'll help. One of the listeners, I forget your name already, very aptly incorrectly mentioned that there was the NASA authorization bill that came out as part of this larger infrastructure and CHIPS semiconductor bill, the CHIPS and science bill, that directed NASA to never do this again, to not cut neo surveyor if there are overruns in other planetary missions again, that they expect NASA to launch this as soon as possible by 2027 if possible. And that this is legislatively directed now, that NASA shall do this mission. That's a huge step forward that hadn't had that before. And again, the money needs to be there, but at the same time you have significant support from multiple congressional committees, multiple members of Congress on both sides of the political divide. And so we have great support, it's just really getting it over that finish line. And Amy Mainzer and her team have just done an extraordinary job through ongoing, completely unfair and frustrating up and down rollercoaster circumstances. And we just really want this to succeed. And that's one of the things we've been trying to do is just emphasize that this mission, neo surveyor, is probably the most supported mission in NASA history. You can go to the National Academies, you have multiple reports to [inaudible 00:42:14] Survey and a special report saying do this mission. You have Congress saying do this mission, we support it. You have appropriation saying here's extra money, do this mission. You have public poll after public poll after public poll. More than four of these consistent over the last five years saying neo observations and neo and planetary defense should be NASA's number two or number one priority for what they do. So you have the public, you've got scientific expertise, specialists, you've got Congress, you've got everybody saying we should do this, so no one's against this. And it's just the fact that we're hitting this buzz saw of internal bureaucratic politics within NASA and the fact that it's a small mission, it's flexible, and it's not really a high priority of any major NASA center. That somehow yet undermines it. So it's a really, in a way, fascinating case study of how these things come together. But we have a lot of really good things going for it and we've been really proud and happy with the progress that we've made this year. And a lot of that's been coming from members who've really stepped up and sent thousands of messages to Congress about this in this last year and really making a big difference, including the people who did the day of action back in March.

Mat Kaplan: So thank you everybody. You got that thumbs up from Bill a moment ago. Here's a question that came in just minutes ago from William West. And it broadens what we've been talking about. And I'll paraphrase slightly with apologies, William and others. He is wondering how is the planetary society prioritizing what it advocates for given budget constraints overall? And in particular, he's interested in contrasting the recommendations of the Decadal, the planetary science and astrobiology Decadal that you've referred to, but also against what's actually been in the president's budgets.

Casey Dreier: Really good, again, very thoughtful and excellent question. And something we're going... So we go through an annual exercise internally at the society, a board of directors. We have a policy committee made up of a lot of really great experienced individuals, scientists, space policy experts, people who worked at NASA.

Bill Nye: So I'll say this again, you guys, our board of directors is comprised of the real deal. These are people who really know the science of space exploration, planetary science especially, and the politics and the economics of space exploration. Back to you, Casey.

Casey Dreier: Yes, and so we use them, and we work internally to really yearly, on a yearly basis to evaluate our priorities. We use the Decadal survey as our starting point, that's our bedrock because we've committed to support it. We have their recommended program, which is very ambitious and a great thing to aspire toward. But then we have to look at the political realities and say when push comes to shove, what are the ones that we're really going to go to the mat for? Because we can't go to the mat for everything. Neo surveyor is one of those, so that's just a core thing of what we do at the planetary. So it's one of the three major things that we do. Neo surveyor is a way to defend the earth from threatening asteroids. So I think even though it's more of a midway between in the Decadal survey, that's always going to be one of our top priorities to support. [inaudible 00:45:54] return is getting a lot of support, it's the top recommendation of the Planetary Science Decadal survey. And it's something that The Planetary Society has pushed for for nearly its entire existence. So that's at the moment one of our top priorities, and I anticipate it being a top priority going forward. And then we go from there and say, we try to, I think, really focus on three major priorities. And again, a lot then based on what's under threat, what's getting a lot of support, and what's the consequences for not pursuing one thing or another? So it's a great question and it's something we do evaluate on an annual basis, and we really do generally try to follow the Decadal because that's the easiest, that's the best way to build a coalition of support behind these things. But you're right, at the end of the day, we have to have our top, top, top priorities to say this is what we spend our time and money on. Because again, it's very finite and we can't do everything everywhere all at once. And so I think we really look to our core goals, our strategic plan, our members' interest and commitments to really help guide us on that.

Mat Kaplan: We are already halfway through this fall or autumn space policy update for you, our members and donors who support the great work by the guys that you're looking at up here, Bill Nye and Casey Dreier.

Bill Nye: Autumn in the northern hemisphere, autumn in the northern Hemisphere.

Mat Kaplan: That's right. Yeah, sorry about that. Hey Southern hemisphere folks, because we know you're out there. We've heard from you. Happy spring. We're going to keep this up for another 45 minutes, and we have tons of terrific questions coming in. Also many more that were submitted ahead of time. I know some of you have just joined us in the last few minutes and we're going to keep trying to get through as many of these as we can. Casey.

Casey Dreier: I remember you had mentioned a question about space minerals and mining asked by a member at the very beginning that I realized we didn't get to. So I want to make sure that we [inaudible 00:47:54] question.

Mat Kaplan: I was going to bring that up a little bit later, but that came from [inaudible 00:47:57]. We can do it now. That came from 13 year old [inaudible 00:48:02] Jacobs, who is also interested in the day of action. But if you want to say something about that and maybe beyond that to the whole topic of international space law.

Casey Dreier: That little thing? Can you remind me the exact question again?

Mat Kaplan: Sure. She said, here it is verbatim, wants to know what kinds of policies we might be promoting, I'm paraphrasing slightly, around the interest in mining asteroids, or perhaps finding resources we could make use of here on Earth on the moon or on Mars.

Casey Dreier: So we actually just went through, there's a couple ways to answer this. First, this isn't one of those things we have a huge part of what we do because we tend to focus more on science and exploration and less on commercial utilization. But we did just publish a commercial policy, our attitude, our internal policy of the planetary society about commercial space exploration and activities. And they're laying out our principles, one of which is that we're just fundamentally excited about new things happening where we want to see them move forward. And then we also want to have a reasonable and fair public interest represented in a regulatory system to make sure that we do it responsibly in how we approach this. So space mining is one of those really fascinating questions that's just on the edge of viability right now. And we have all these laws that have been developed in theory but have never actually been tested into practice. And we're seeing the development and establishment of precedent, of ways of doing business. Like NASA offering to buy lunar samples that are collected by a commercial company helps establish that commercial companies can collect things and then privately sell them to another person. That creates a legal precedent behind that. That's all new. We're inventing this as this is happening. One of my good friends in the space community is Elizabeth Frank, who was the first planetary scientist.

Casey Dreier: ... the space community is Elizabeth Frank, who was the first planetary scientist hired at ... or the chief planetary scientist at the first asteroid mining company and planetary resources. And I've talked with her and she's in a new company now called Quantum Space, and she talks about that there's all sorts of interesting challenges of actually doing the mining when you get down and dirty with it. Right? Like the fact that there's tons of dust, that the fact that a lot of the ore and things that you're interested in are all mixed in with rocks and stuff that you don't want, and it's really hard to bring it back. There's lots of practical problems that we're trying to figure out. And so I think the most interesting aspects of this are going to be along this resource utilization, like can we get water made on the moon, made on Mars? Oxygen. We're seeing this in perseverance. We have MOXIE generating breathable oxygen out of the Martian atmosphere for the first time on Mars, and using that to make it easier, so we bring less stuff with us. And I think the moon is going to be a really promising place to explore with this in the next 10 years because we have so much activity about to happen there. We have, not just with Artemis, but with this commercial lunar payload delivery services where we have multiple companies building the ability to just FedEx your instrument or your resource utilization system to the surface of the moon. [inaudible 00:51:19]-

Bill Nye: Does FedEx ... FedEx?

Casey Dreier: Yeah, so you can ... What would it be, a three-day delivery to the moon I think, roughly?

Mat Kaplan: Right, yeah.

Casey Dreier: And you have lots of opportunities coming up, but again, we have to do it in a way ... I also ... A colleague and I wrote a paper to the Decadal survey just kind of for fun on the ethical implications of commercial ... how commercial mining and exploitation on these planetary bodies alter the potential scientific return. Anytime you do something on the surface of the moon, you kick a bunch of dust into its exosphere, you fundamentally change the pure potential of scientific discovery from the original untouched land. Right? And if you take as the highest form of motivation that you want to learn about the cosmos as that information, that science itself has this inherent value or intrinsic value, you degrade that by exploiting or utilizing things. That doesn't mean you should never do it, but it does provide maybe an ethical motivation to say, "We better explore these places for a scientific ... We better get their scientific value out of them as fast as we can, as soon as we can, before we modify what those environments are through our resource utilization or through even human exploration." So it's an interesting way to think about as we start to do things out in space, that'll change the types of science that we can get back from them, and that can help us inform what we do prioritize in the short term in order to seek those out. Again, that was kind of a fun thing that we did to challenge us to how to think about why and where we go, and how we classically try to prioritize one destination over another.

Bill Nye: So how do you claim an asteroid? Whose asteroid is it, you know? To get-

Casey Dreier: Yeah, you can't. Right? And that's the other ... You can claim this resources. The US in the Space Act that passed about seven years ago now, at 2015 under Obama, stated that you can own the stuff that you gather, but you can't make territorial claims around it. So you're trying to walk this line between what the UN charter on this is, the Outer Space Act, which says no nation can claim space or claim land on a celestial body, but still incentivize people to say that what you own, what you collect. So the classic comparison that we all know of course is commercial fishing where no one owns international waters, but you can keep the fish that you collect out of it. And so I think there's an interesting way to find compromises.

Bill Nye: What if you could collect the whole asteroid?

Casey Dreier: Exactly.

Bill Nye: The whole ocean. There's no asteroid left. You've used it all up. There's no territory anymore.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. That'll be one of those things that'll be an interesting theoretical question until we get to it. But eventually, we're going to get to a situation like that, right?

Mat Kaplan: Fascinating, yeah.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, it's a lot of unknowns.

Mat Kaplan: I'm going to go onto another topic, and Bill, it's one that I think you predicted we would hear about from some people, and we are. A question that came in related to this just as we've been talking from Thaddeus Jeznak, I hope I have that right: with the Artemis launch scheduled for next week, roughly. I think it's a couple weeks.

Bill Nye: It started ... They'll roll it out on the fourth and then the launch window's the 12th, right?

Mat Kaplan: I think so. 12th, 14th. I think they have three possible days.

Bill Nye: [inaudible 00:54:59], yeah.

Mat Kaplan: Anyway, Thaddeus is wondering what is The Planetary Society's plan or what's our policy position going forward regarding missions to the moon? I'll widen that and say Artemis and I'll even go to Mel Powell here, who wants your shirt still, Casey. He talks about November 14. He calls it the SLS, the Someday Launch System. Joke aside, how anxious are lawmakers going to start feeling if our one new rocket thing continues with bumps?

Bill Nye: Oh, Mat, you locked up on me. Mat, come back. Can't hear you, man.

Casey Dreier: Well, Bill, I think we got enough of that question that we can continue going here.

Mat Kaplan: [inaudible 00:55:46] speed bumps and delays. He worries that Congress will ... I don't [inaudible 00:55:54] audio [inaudible 00:55:56] in and out. I may be having some problems. Can you hear me now?

Casey Dreier: Yeah, barely. We got the gist of your question, so we can pick it up from here.

Mat Kaplan: Well, shoot.

Casey Dreier: Bill, do you want to pick up on that?

Bill Nye: Well, I don't want to get in trouble, but the Space Launch System is putting a lot of eggs in one basket where you have to leave earth, go around the moon and come back and then the second flight, you put astronauts on board and go around the moon. Okay. Okay. Because what has caused these delays, which are frustrating Thaddeus among others, is this need to have it synchronized or the orbital mechanics coordinated with the orbit of the moon. And so I have pondered without reconciliation ... By that, I mean we haven't reached a decision on the policy committee. Are we going to end up advocating for more flights of SLS to make sure this thing is wrung out before people start flying it? And also this week will be the ... You guys, also this week will be the second launch in three, or I guess it's the third launch overall in three years of the space of the Falcon Heavy. And the Falcon Heavy is almost as big as Space Launch System. So, we wish everybody the best. But the reason these delays are happening is because of, I believe, not just a kooky hydrogen leak. And just more about me, when I had a regular job ... Oh this is a regular job. When I had an engineering job, I'll just tell you guys, O-rings are magical. When you get the right O-ring system assembled, what makes them work so well is the groove, the gland it's called that the O-ring sits in. It works so well almost always. But when you're talking about hydrogen, it just leaks so easily in the space shuttle mess with this. But if we can get or they, or it can get the hydrogen systems working, this could be a great advancement in space exploration. So, part of the reason these delays have happened is because coordinate with the moon. And another thing that Casey and I discussed mostly by email that will not happen is this kooky frustrating thing where the batteries on the flight termination system, there's a fishing boat, comes out in the middle of the ... off the coast, rather. Off the coast of Florida and they got a delay while they get the fishing boat out of the way. If that battery goes down, then they have to wheel the whole thing back to the vertical assembly building. But they're going to avoid that. This is good. Back to you, Casey.

Mat Kaplan: Before you jump in, Casey, the other thing I'm worried about is all these wonderful CubeSats that are on the SLS to be released as it sends Orion to the moon, including NEA Scout, the solar sail.

Bill Nye: [inaudible 00:59:12] NEA Scout [inaudible 00:59:15].

Mat Kaplan: Right? That The Planetary Society has worked so closely with the people at Marshall Space Flight Center developing that sail. It would be so sad to see these delays end up interfering with any of those CubeSat missions. But Casey?

Casey Dreier: Yeah. And obviously a chunky topic here. Maybe the biggest job creator of the SLS is people giving their hot takes and space policy opinions on it at writ large. Because everyone ... I had probably more media interviews and discussions leading up to the first launch attempt on the SLS than any other subject in me tenure.

Bill Nye: You went down there, Casey. You went down there. I mean-

Casey Dreier: I was there for the aborted launch with Mat, which was still great because it's cool to still go there and see all of our colleagues and friends in the space community and NASA. Standing in the shadow of the colossus of the VAB is always a wonderful experience for me. So I wrote a whole article on this, which I'll just keep plugging because I think it makes the case how to interpret the SLS as ... the way that there's a good ... The SLS is like an extended phenotype, like where its implications go [inaudible 01:00:24]-

Bill Nye: Yeah, my grandmother used to say that. It's like an extended phenotype. What?

Casey Dreier: The idea that it's not just optimizing in some internal sense; that its output and consequences extend beyond the concept of building a rocket. It's answering a political problem that has existed since 1972-ish, which is what do you do with the shuttle workforce? And you cannot like ... I think people are fair to be frustrated about that as inefficiencies of a public space program. But I kind of argue and I believe that as a public program, you have a range of needs to fill when politicians give you money for free. It's kind of the cost of doing business in a public system, and it needs to solve for ... It needs to give members of Congress and others a reason to vote for these things that have an immediate parochial value to them, including keeping people in their districts employed. And so the SLS answers this in a relatively frustrating way if you were purely optimizing for best rocket heavy launch technology. Right? But at the same time, it's proven to be profoundly durable through all of this. For the last 10 years, I put together in my article, there's not one year that the SLS has existed where Congress has not thrown more money at it than was requested by the White House. Every single year, they added money to it. And it's also profoundly supported in the authorization committees and others, and it spends money everywhere. That there's a reason for this. Now, can it work? Can this continue if it explodes or doesn't launch at all? That becomes really challenging. And I mean, you're hitting into ... And I wrote this in one of my recent Space Advocate newsletters, which I hope everyone subscribes to here, that at the end of the day, you can have all the beautiful or clever policy solutions and political parochialism answers that you want. But if it doesn't work, you really can't sustain that over time. It has to work eventually.

Bill Nye: Would you say that's what happened to the space shuttle? [inaudible 01:02:49]-

Casey Dreier: Well, yeah. I mean, the space shuttle only ended because it stopped working, right? Like with Columbia was the death knell. And it still took eight years after Columbia to finally wind the program down. And you had people like Bill Nelson advocating at the end of that to keep it going even longer. It took real political will to stop it. And really, it was only stopped because they shifted the workforce and the contracts from the shuttle to Constellation and then to the SLS and Orion. So all of that moved into something else. And the shuttle was a 40-year program. Space Station is rapidly approaching a 40 year program. And if the SLS can launch and do its fundamental job, I think it could easily be a 40 year program too, because these things build really powerful inertia because you're not solely judging it on the technological capability. You have to see it from this extended viewpoint of the political coalition and problems that it's solving too. And that was what I tell people. It's not that I'm out there that I love every aspect of the SLS. I find the program profoundly frustrating and challenging to support or to even find a way to really honestly support it. But I have not seen someone propose a solution that solves the political problem that the SLS is solving. And if people want that to stop, they need to think of it in that sense. Cutting a bunch of money and giving it to SpaceX in Hawthorne, California ... that's why I always say go into Shelby's office in Alabama and say, "Hey, I've got this great political proposal for you. We're going to take the two billion a year that's flowing into Marshall. Let's take that, cut that, fire 30,000 people in Northern Alabama, and take all that money and give it to Los Angeles instead." [inaudible 01:04:40].

Bill Nye: That's great. That's a great idea.

Casey Dreier: And just think of all the stuff that [inaudible 01:04:44].

Bill Nye: [inaudible 01:04:44] everybody, I'm being ironic.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. It won't be happening in Alabama. It won't be happening in your district. Your people will be laid off. Your constituents will be angry. But think of how great Los Angeles will be with it. It's just not a convincing ... That's not a political situation that's going to be feasible. And in a representative democracy where we have representatives represent discrete, separate geographical districts, that's just not how that's going to work. And so the SLS ... This is a long political thing about, but it's got to work though. And I think we're seeing a lot of growing pains and a lot of frustrations. And fundamentally, to even step back from the kind of argument whether it's good or bad, you're seeing a really fascinating comparison between this low flight rate kind of bespoke, delicately made handmade rocket that you build one a year of and all the problems that brings you, because that cannot fail. You can't test that and blow it up like SpaceX does, because they're printing rockets out of their facilities. They can blow their stuff up and then they'll have another one ready to go a couple weeks later to keep testing it. We can't do that with the SLS because it'll take you another year to build one. And so you're stuck in this profoundly conservative engineering environment where you cannot take risks, where you have to succeed. And so any little thing that throws you off, like what we saw in the first launch attempt, will cause these big delays. And so it's an interesting comparison of this rapid iteration that SpaceX does and the slow kind of I would say CAD based modeling engineering approach to rockets that that Boeing is doing with the SLS. So anyway, yeah, we could easily make a two three hour discussion on this. And I have, I'm sure on the podcast before, but broadly, here's how I leave this, right? And I can toss this ... Bill, you can see how you react to my analogy or metaphor here. The SLS, imagine riding an elephant through a jungle and you're trying in vain to direct where it's going and maybe you can get it to go one way or another, but it's just tromping through the jungle on a clipped pace, and you'll eventually maybe get where you're going for, but it's going to take a lot of time and it's going to be really messy as you do that. But what you've done, if you look behind, you've created a path that all of these other things can follow you. You've created them the path to where you're going that all of these other organizations and individuals and people can follow you to. So the elephant clears the brush and then you have a new road to the moon. And so this is where I see the SLS is doing its thing, but we also have the commercial lunar payload delivery. We have SpaceX sending people around the moon. You have companies setting up to provide communication services. We're investing in surface nuclear fission power because we've going to have people there. SpaceX is building a lunar lander, for goodness sakes. Then you have private companies like Blue Origin and others trying to build their versions of this lunar highway or access to lunar highway. And it's all because the US has put the moon as its top policy destination, has bought into it at a deep way with the SLS that for them has to work. And then everyone else gets to kind of follow in that pathway. So whatever else is happening-

Bill Nye: [inaudible 01:08:16] jungle.

Casey Dreier: ... this broad system, that this broad movement is in an unprecedented way, very unlike Apollo where it was only ever Apollo, we're seeing so much excitement, energy, and new ideas coming into this that I think it's worth it even if it doesn't fundamentally deliver on its promises.

Mat Kaplan: And with that, Casey, I think you touched on a question that came from Guy Nedor before the program began, which I'll get to in a moment. I love your elephant metaphor. I've told you that before, that path through the jungle that's been carved by the elephant. But you know what also has to happen if you follow an elephant, right? What, and leave show biz?

Bill Nye: It's a good joke. It's a solid joke.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, sir. Coming from you, that means a lot. The rise of non-governmental space flight companies, some of the ones you've just talked about, Blue Origin, they're going to get that New Glenn to fly, and Vulcan is going to fly on those engines from the same company and all the other efforts out there. How is this affecting The Planetary Society's concerns about space policy? I mean, how do we feel about these proliferating commercial developments?

Casey Dreier: Right. Well, again, I'll plug our commercial space flight policy principles that we released. It's on our policy page or principles page that we can send out after this. But also you can find it there.

Bill Nye: It's on the electric web, right? You just click.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, sorry. Page on our webpage, on the space policy page. And I mean, again, fundamentally we're excited about it, right? This is an ahistorical moment where we do not have historical analogy to turn towards to see how this is going to turn out. This is a vast experiment, frankly, that's happening before us; that NASA's taking a radical approach based on completely unproven outcomes. But it may work. I talk about this a lot where we're basically ... NASA and a lot of other places now are starting to do policy by outlier where we have SpaceX, which is this profoundly successful company that we assume will be the average outcome, the median outcome or whatever you want to define it, of these types of new companies coming in. But so far, it's really only been SpaceX, but we're acting like every company is going to be another SpaceX. That may or may not work. We don't know. We don't know where the domain of commercial services is going to apply towards, if it's just going to be in lower earth orbit or if it's going to be at the moon or geo or who knows?

Bill Nye: Casey, when you say we are expecting, who's we? The public or the editorial pages or something?

Casey Dreier: That we are doing this? We-

Bill Nye: We are expecting every startup to become SpaceX.

Casey Dreier: Oh, the policy ... So NASA policy, US policy that does commercial partnerships is expecting ... It basically is written as if ... So again, clips is a great example of this. We're investing in ... We're basically providing seed funding and startup funding for companies to develop, again, those payload delivery services. There's no precedent for this. We use SpaceX as the example of success from the commercial orbital transportation services contract, but it's only ever been SpaceX. Right? We don't have a lot of examples of success beyond that. And so we expect them all to succeed and provide lower cost and to increase reliability when in fact, we only have one example of a company really doing that. Orbital, which is now Northrop, which has the Antares rocket, is an interesting kind of counterpoint where you didn't see them attempt to completely restructure the launched vehicle industry. They're not building Starlinks. They're not even selling that vehicle or even marketing it to other people. They're just building it for NASA. They do exactly what they're asked for and they do nothing more. There was no innovations in reusability. There was no huge ... There was cost savings, but there was no fundamental transformation of the market.

Bill Nye: Off the top of your head, can you compare payload size, Antares versus ...

Casey Dreier: I can't off the top of my head. I think they're a little less, but they're both designed to be kind of mid capability rockets and they deliver ... They're large payloads, but they just don't come back. There's no return capability and there's no obviously reusability of the first stage.

Mat Kaplan: Unlike Dragon, which comes back.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. Yeah.

Bill Nye: Falcon. Falcon.

Casey Dreier: Well, Falcon comes back and then the Dragon capsule itself comes back.

Bill Nye: Yeah, because there's people in it, sometimes.

Casey Dreier: People or even cargo come back. Yeah, they start with cargo and then-

Bill Nye: Okay, fair enough.

Casey Dreier: So I think that's just interesting that we're in this big moment of experimentation. And again, what I think is the important part ... I don't want to sound down on this. I think we just have to be realistic that we don't know how this is going to turn out. But at the same time, we know how the other way works. Again, we can look at the SLS. Cost plus contracting has not done itself any favors in the last 10 years about results of performance.

Bill Nye: Describe cost plus contracting.

Casey Dreier: Cost plus being as opposed to paying a fixed price for goods and services or development. Cost plus is that the government is on the hook for the full cost of development plus any overruns, plus some performance fee. And so it doesn't incentivize companies to cut costs because they're going to get paid by the government no matter what. There are times when that's appropriate. When you're building Apollo or a lunar lander for the first time ever and you didn't even know if you could do it, you don't want to bankrupt a company by telling them to build a lunar lander for this fixed price when you literally have no idea what you're doing. And a lot of defense procurement contracts are based on that. But the concept was for launching into low earth orbit, that was a known enough problem that you could set a price on it. We're giving you this much. If you need any more, you can raise it from private investors, and then you were incentivized to lower your costs. Because the less you spend on it, because we're fixed, the less you spend, the more your profits are. But we're not going to pay you. This has actually saved NASA a ton of money with Boeing's Starliner, which we just saw now has gone up to ... Boeing has taken a write-off of almost a billion dollars now on that mission for their own delays that prior to this would've been paid for by the taxpayer. And it kind of is, because all of Boeing's income on that side of the business comes from taxpayer money anyway. But let's not split hairs about it, but it's an interesting ... It's protected NASA from those cost overruns from the delays of Starliner. So anyway, I think that's a really exciting thing that's happening. And at the same time, we need to remind ourselves-

Casey Dreier: It's happening. At the same time, we need to remind ourselves too that there's a role for... That this is not a blanket approach and this is what we talk about in our principles. Is that for a lot of the things that The Planetary Society really cares about, space science, pure exploration, planetary defense, the search for life, those aren't activities that are classically commercialized or even commercializable. There can be overlap between them. There can be opportunistic science done on commercial payloads and rides. There are ways to maybe lower costs through certain clever, again, fixed price procurements and rocket... The way that the lowering cost of launch has really helped for missions like Psyche, which is launching on a Falcon Heavy when it does launch. But you need the public sector to fill its role as performing this basic research and development exploration that just by definition is not a money making entity. That's what we're generally really interested in. So we see commercial as a way, as a tool, as an enabler for some of the exploration that we want to do. And it lets NASA focus on these, again, highly designed, carefully thought through, once in a lifetime exquisite instruments like the James Webb Space telescope or the Perseverance Rover that you're not making, you're not printing off of a production line. You're making one, maybe you're making two. And it's designed to answer some of the most challenging questions that we have about the nature of the cosmos that is not going to result in anyone getting rich, but could result in a fundamental enrichment of our self-awareness and knowledge.

Bill Nye: Change the world.

Mat Kaplan: Casey, we have less than 15 minutes left now before we hit the top of the hour and the end of this update, which we will continue to do on a semi-annual basis on your behalf, our members and donors who make all of this possible. We have so far not addressed the number one topic that was brought up by many people who submitted questions ahead of time. And so I'm hoping we can talk some trash before we run out of time here. Here's a good question about this. Oh, let get to another one first. Daniel Blake says, "How are we getting our trash back from space? Please don't tell me we send stuff out without a plan to get it back." Well actually, Daniel, some of it comes back on Dragon capsules and some of it just gets burned up inside one of those-

Bill Nye: And some of it is still up there and won't come down for decades.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. But here is the more significant question from Ken Gokin representing a lot of other people, Ken's in New Jersey. The proliferation of space junk in low earth orbit, Leo, is on the verge of becoming a threat to all space activities. Although the focus of TPS is generally beyond Leo, everything that goes out has to get through Leo. Human exploration will be staged in Leo. Do we have at the society a position on maybe not just junk in space, debris, sometimes debris generated on purpose, but also the thousands, tens of thousands of satellites that are going into lower earth orbit?

Casey Dreier: We don't have a specific position on it. We kind of infer some of that based on our other policy principles that are really drived to our focus, particularly the responsible use of outer space, the responsible regulatory oversight of commercial entities, and having access to space and a responsible, preserving the space itself for future generations. It's all in our policies. The one good thing about this. So I'm going to just jump back and say just from a philosophical perspective for The Planetary Society, something that we like to do is really focus on things that we think are underserved in terms of space policy. Exploration, search for live planetary defense, planetary exploration, robotic and civil space. There are our core areas. There tends to be not very much money, not as much interest because there're just not big money making areas. And with that way we have a really big impact on them because we can spend a lot of our time, we can get our members engaged, and we fill I think a really important need there. Fortunately for things like space situational awareness and space debris, that is probably the biggest topic among the broad space policy community, including National Defense in on a global thing. I was just at the Secure World Foundation's workshop in London about this earlier this year where this is something we pay attention to and engage on, but there are really great people working really hard on this. The White House's National Space Council is working on this. The Office of Science and Technology Policy is working on this. And then you have, again, a global consortium of people working on this. You just saw rules proposed by the White House lowering the maximum lifetime of any unused debris to five years to help address this. And also really thinking about how we're going to be as we deploy, as people deploy, mega constellations, making sure those have deorbit plans baked into them so you don't just pollute our local environment to make it unusable. It's a hard problem fundamentally for a number of legal and basic physics issues. But the good news is that there's a lot of great people working on it. You saw Marie [inaudible 01:20:43] who is really well known for this just won a genius grant from the MacArthur Foundation for his work on this. There's private companies like the Private Tier Foundation, which is funded by Steve Wozniak from Apple working on this. And then you have a number of NGOs and others around the world. So I feel like the topic is in really good hands. This is something we pay attention to, but again, based on our core motivations as an organization, we're going to focus our work on those underserved areas. Knowing that this isn't...

Mat Kaplan: There are a couple more areas that we should definitely try to cover before we run out of time here. And one of those I told you guys about, it takes us back to Thaddius, Thaddius [inaudible 01:21:27] in Connecticut. Don't think I said before. And it also turns us inward a little bit. Bill, I think be great to start with you on this. What advances, if any, have we as The Planetary Society directly contributed to?

Bill Nye: Oh, where to begin? Well search for extraterrestrial intelligence started out as a screen saver. Many of the older members were probably doing that and we hived that off to the City Institute. That's definitely-

Mat Kaplan: City at Home. Yeah.