Planetary Radio • Jun 23, 2021

The Pearly Clouds of Mars

On This Episode

Mark Lemmon

Senior Research Scientist, Space Science Institute

Kate Howells

Public Education Specialist for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

Want to see wild colors on Mars? Look up! Planetary scientist Mark Lemmon studies planetary atmospheres at the Space Science Institute. He marvels at the images taken by Mastcam on the Curiosity rover of shimmering iridescent clouds high above the Martian surface. The Planetary Society’s Kate Howells looks back at the 1998 blockbuster movies that got a lot more people thinking about the near-Earth object threat. A few clouds won’t keep Bruce Betts from sharing his latest What’s Up look at the night sky.

Related Links

- NASA’s Curiosity Rover Captures Shining Clouds on Mars

- May 30, 2011 Planetary Radio: Scattered Clouds and Fog...On Mars

- "Just Nuke 'Em!" Planetary Defense in the Movies

- Risky business: will the world rise to the challenge of asteroid defense?

- LightSail

- The Downlink

Trivia Contest

This week's prize:

A hardcover copy of Carbon: One Atom’s Odyssey by John Barnett

This week's question:

What is the only one of the 88 official IAU constellations that is named for an actual person?

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, June 30 at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

After the Sun, what star has the largest angular diameter as seen from Earth?

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the June 9, 2021 space trivia contest:

Who holds the record for most launches from Earth (and only Earth) at seven?

Answer:

Franklin Chang-Diaz and Jerry Ross are tied for the greatest number of launches from Earth with seven each.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: I've looked at clouds from both sides now, on Mars, this week on Planetary Radio. Welcome. I'm Mat Kaplan of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. We'll do some Martian cloud watching with atmospheric scientists and solar system explorer Mark Lemmon. When we're done staring at the clouds, we'll ask Mark about dust, fog, and snow. Yeah, snow on the red planet. Snow falls, likely. Asteroids? Not so much.

Mat Kaplan: My colleague Kate Howells has written a belated review of the asteroid disaster movies Armageddon and Deep Impact, reviewing what they got right and what they got very, very wrong. Of course, Bruce Betts will also join me for this week's What's Up and his latest space trivia contest.

Mat Kaplan: File this under why didn't we think of that. There's an image of China's first Mars rover next to its landing platform at the top of the June 18 downlink newsletter. It's not a selfie. The rover dropped off a wireless camera and then backed up into the resulting image. Pretty cool. You can see it at planetary.org/downlink.

Mat Kaplan: Of course, there's also this helicopter on Mars. The headlines include very good news for everyone who wants to avoid a deep impact. NASA is moving forward with the infrared space telescope called NEO Surveyor. We'll soon welcome back the Asteroid Hunter's principal investigator Amy Mainzer.

Mat Kaplan: You've probably heard that China has astronauts back in space for the first time in several years. The three men are aboard the nation's first space station. Meanwhile, the first space launch system rocket is coming together in the Kennedy Space Center's Vehicle Assembly Building. The giant core stage has been made into the twin solid rocket boosters.

Mat Kaplan: Lastly comes word that a Finnish company is building the first nanosatellite made from wood, plywood actually. How long could it be until someone builds one out of Legos? Here's that conversation with Kate Howells.

Mat Kaplan: Kate, good to get you back on Planetary Radio. Thanks for this cute little piece about those two movies that came out weeks apart in 1998 that, frankly, I had such high hopes for. The results: mixed at best, would you say?

Kate Howells: Oh, absolutely. I mean I rarely have very high hopes of accuracy in Hollywood movies about space. It's a shame that they didn't do the topic justice, because planetary defense, as we know, is an intricate and fascinating field. But at least they made people, overall, aware that asteroids can hit Earth. You've got to give them credit for that.

Mat Kaplan: And you did give Armageddon credit for that, because it was basically the only thing that it got right. I share your opinion of that movie, but it's kind of fun.

Kate Howells: Oh, it's a good time. I enjoy the movie. It's very silly, especially when you know the truth of the topic. But it's a romp, that's for sure.

Mat Kaplan: The best thing I can say about it is that it got Bruce Willis, at least one mention in every planetary defense conference.

Kate Howells: Well, that's good.

Mat Kaplan: So let's move on to the other one, which, frankly, I thought was a great deal better. What did you think of Deep Impact?

Kate Howells: Oh, I love Deep Impact. I think it's the lesser known of the two movies. I'm often recommending it to people because the first time I saw it ... I mean spoiler alert, if you haven't watched Deep Impact, you might want to pause this and go quickly watch it ... the fact that this comet does damage the Earth, I mean they do not completely escape the consequences of the solar system throwing rocks at us, I thought that that was marvelous.

Kate Howells: I mean normally in a movie like Armageddon, the hero saves the day and disaster is averted completely. I liked that Deep Impact showed that sometimes you can't save the day completely. So just for that, I appreciated it more. But also it's a more satisfying movie if you are a bit of a space buff.

Mat Kaplan: I couldn't agree more. Anybody can see your piece. It is both in the current issue, that is the brand new June Solstice issue of The Planetary Report, but it can also be found separately at planetary.org. In fact, the whole magazine could be found there for free nowadays. Of course, our members get the beautiful print version.

Mat Kaplan: You close with the thing that hit home most with me, and that is that, yes, we are all about raising public awareness of this. And that's still what we're about. I guess there's still room for a better movie on this topic.

Kate Howells: Yeah, I mean especially given that, in this day and age, Hollywood just seems to be regurgitating old movies, just making remakes. I would love to see a remake of an asteroid movie. People have written in saying that just by focusing on Armageddon and Deep Impact, I ignored a whole host of other asteroid-related movies. And this is true. But in terms of sort of blockbusters, it's about time for another asteroid movie, and maybe they will consult a little more with the science community and create a scenario that is more realistic and depict some of the actual geopolitical and technological challenges that face us when we think about the possibility of an asteroid or a comet impacting the Earth. That would be interesting.

Mat Kaplan: That would be interesting and a great service, Kate.

Kate Howells: Indeed.

Mat Kaplan: As is your article. Thank you so much for giving us this little capsule movie review that dates back to material created 23 years ago.

Kate Howells: Well, thanks for having me.

Mat Kaplan: Kate Howells is the communication strategy and Canadian space policy advisor for The Planetary Society. My colleague Mark Lemmon has joined us a couple of times. He's now a senior research scientist at the Space Science Institute in College Station, Texas. But his work has put him, in a virtual sense, in the skies of Jupiter, Titan, and especially Mars. He studies aerosols, stuff suspended in the air of these worlds.

Mat Kaplan: Along the way, he has become one of Earth's most experienced and accomplished photographers on other worlds, including his work as imaging team lead for the Phoenix Mars Lander. He's also a co-investigator using Mastcam-Z on the Perseverance rover.

Mat Kaplan: Mark was quoted in a Jet Propulsion Lab media release that led me back to his door for a conversation that began with those clouds above Mars. Mark Lemmon, welcome back to Planetary Radio. Good to be talking about the clouds of Mars, although we have some other things that we may want to cover as well. Welcome.

Mark Lemmon: Well, hello. It's great to be here again.

Mat Kaplan: So when we talked 10 years ago, we were still mourning the loss of Mars exploration rover Spirit. We were looking forward to picking a landing spot for the Mars science laboratory Curiosity. I believe you're still working with Curiosity as it crawls up Mount Sharp. We'll talk about that, too.

Mat Kaplan: You're on the Mastcam-Z team for Perseverance. Phoenix has come and gone, InSight's still going strong, MAVEN, the UAE's hope, India's MOM, and others looking down from above. That's a lot of exploration in science. What has most excited and/or surprised you after 10 more years of observing Mars?

Mark Lemmon: Well, it's a great time to be trying to explore Mars because we've got all of these wonderful assets that are participating in the exploration. I love being on the rover teams, the lander teams as well, when there's that chance. It is just startling on maybe not a day-to-day basis, but certainly a month-to-month and a year-to-year basis that we can have this rover sitting there on Mars and find new things. We've intentionally set out to find new things and we're still doing it on purpose. Then we're also doing it because Mars decides to show us something. So it's just excellent.

Mat Kaplan: That is such a regular theme across almost every show we do, every person that I get to talk to that is no end to the surprises out there across our solar system and beyond. Do you still actually work with commands, right commands, that get sent to Curiosity to tell it what it should look at and image?

Mark Lemmon: Well, I've had a lot of different roles on the different missions as time goes by, and some of them have literally been writing the last human readable version of the command file before it gets translated into something that the rover can execute. What I do on Curiosity, on Perseverance is work with a very slightly higher level version of the commands and occasionally dabble in the actual command itself.

Mark Lemmon: But there are people who are responsible for that, who have lots of training in the system engineering of the protocols for ensuring safety and things like that. There are a lot of people to make sure that I don't go and point the camera in a way that it's going to cause damage, that sort of thing. They make sure that they follow all the rules.

Mark Lemmon: I worry about composing the pictures, making sure that they're going to achieve the science that I want and that level of manipulating the commands. But, yeah, I am sitting there saying, well, I want this rover to take a picture using these filters to see these wavelengths of light at that particular time, that I get the privilege of seeing this imaging sequence that I dreamed up happen, and play with the data when we get them back from Mars. It's great.

Mat Kaplan: That is a heck of a thing to be able to do and tell people, "Yeah, I take pictures on Mars for a living in part." I want to talk to maybe toward the end of this conversation about what it takes to get a good picture, a good snapshot on Mars.

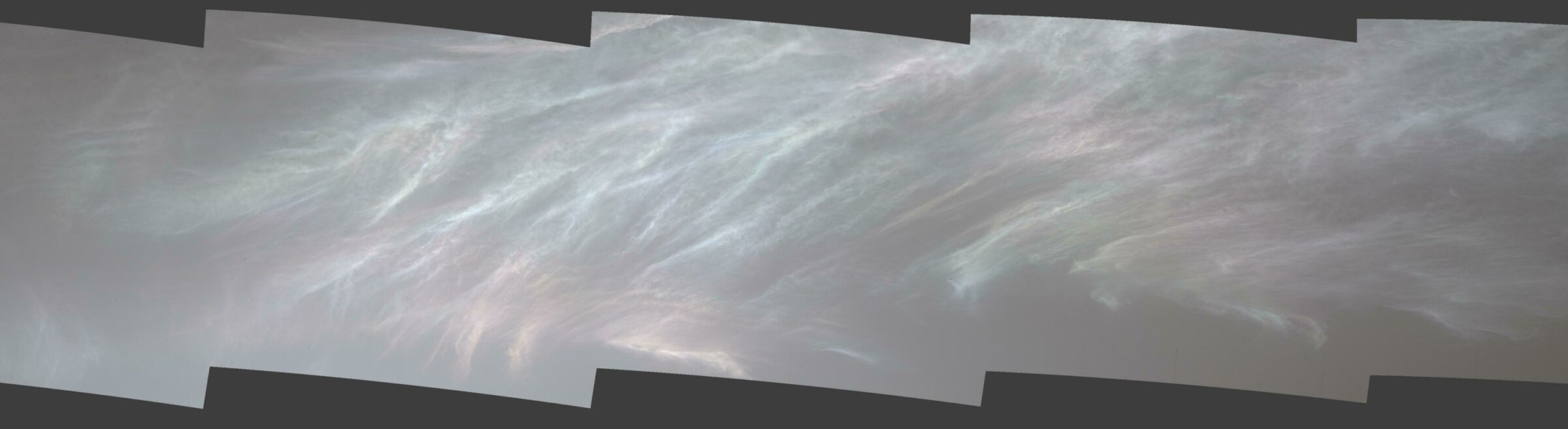

Mat Kaplan: Let's get to the story that caught my eye and made me think, "Shoot, I've got to bring Mark Lemmon back." This was a press release just recently about what we're learning about the clouds of Mars, which we've been seeing those for ages, but it was the beauty of some of these new images that really caught my eye quite literally. I knew I had to talk to you about it. Tell us about these, first of all. I mean what are these new clouds and what are they made of?

Mark Lemmon: Yeah, clouds on Mars and our observations of them go way back. We were observing them from Earth before we ever sent anything to Mars. So it's not a surprise that there are clouds. We get to Mars with some of the things to be able to characterize them, starting with the orbiters, the first landers, and now the rovers. We're able to see the clouds in different ways.

Mark Lemmon: We've known, again, for some time that there are a couple kinds of clouds. There are water-ice clouds. Depending on where you are on Mars, those water-ice clouds can form as low as the surface. They're fog in some places. And there are high-altitude clouds, 15 kilometers, 10 miles in other places.

Mark Lemmon: Then Mars also has carbon dioxide clouds, dry ice. These are frequently caused by gravity waves when basically a hot/cold section of atmosphere propagates itself upward with pressure changes. When the atmosphere cools, it's already very cold, you get the atmosphere itself below the freezing point of that atmosphere, which is carbon dioxide, and the carbon dioxide freezes out and you get clouds.

Mark Lemmon: We took pictures of those clouds with Pathfinder. We've seen them from orbit, we've seen them from time-to-time, but there's not a ton of information about all of the different kinds. In daytime images of Curiosity, we see clouds all the time ... Not all the time. We've seen them every year. There are seasons for them. We see these faint wavy patterns, these wave clouds, and have tried to characterize those.

Mark Lemmon: But we were shocked two years ago to see clouds during a time of year that we thought of as not cloudy for that particular site, which was right after the turn of the year, the northern spring equinox. We got a few pictures of them at the time, but that turned out to be a very limited cloud season. But we could use some old data that we had to show that this was not a one-time occurrence. This had actually been happening and we just didn't know about it.

Mark Lemmon: So we put a note on the calendar and this year came back to it, and it coincided essentially with Perseverance landing. So that was a very, very busy time, dealing with Perseverance on the one hand and then trying to characterize these clouds that we saw with Curiosity on the other.

Mark Lemmon: But we put together this great set of observations. You've seen some of the results in these pictures that came out.

Mat Kaplan: They're gorgeous. We will put up a link to the press release that has some of these photos. There are links from that as well. But we'll put that on this week's show page at planetary.org/radio.

Mat Kaplan: I was shocked to read that some of these carbon dioxide clouds are more than 60 kilometers up, or about 200,000 feet, more than 200,000 feet. I'm surprised to learn that there's enough atmosphere at that height, especially above Mars, that you could have clouds. Was this a surprise to any of you?

Mark Lemmon: It's a surprise in a bigger picture sense. We knew it before we took these pictures. But it's certainly stunning to think about an atmosphere that's already 1% of what we have on Earth at the surface. Then you go 70 kilometers above that and we're seeing clouds.

Mark Lemmon: But those clouds have been seen from orbit. There was actually even ... About the same time we saw these clouds for the first time with Curiosity, a paper came out from Todd Clancy using spectra taken from orbit to show that some particular high-altitude, 60-kilometer altitude, clouds that he was looking at were carbon dioxide. He could actually see the composition because he had spectra.

Mark Lemmon: Then with the spectra, he could tell that they were iridescent clouds. Iridescence shows up in spectroscopy differently than it does in the images and you get this nice wavy spectrum. He looks at that and he says, "What in the world is doing that? Oh, that's an iridescent cloud," which means that it's a cloud full of cloud particles that are all just about the same size. So they all scatter light in exactly the same way. It all adds up in a coherent way. You get what visually looks like this variation of pastel colors.

Mark Lemmon: They're spectacular clouds to look at on Earth. They're spectacular clouds to see on Mars. But that first indication was from the spectra from orbit that we actually had iridescence. As it happened, I had seen the iridescence in the pictures before I found out about that. The paper was being published at the time. So it's a way to see the same thing in two very different ways.

Mark Lemmon: So we know that there are these high-altitude clouds. The orbiters see them, even Mars Pathfinder, in some of the few images that it got in the twilight, saw clouds that were ... Because the sun was shining on them. When the sun was weighed down, they were demonstrated to be 50-plus kilometers high.

Mark Lemmon: That's essentially what we can see with these clouds is, with the images from Curiosity, we can't measure that they're carbon dioxide, we can't measure that they're water-ice. But because of the timing that we took the images, and especially some of the Navcam's images, the black and white ones that we released where you can see the sunset line move across the clouds, it's basically the shadow of Mars projecting onto the clouds, and that tells you what the altitude is.

Mark Lemmon: So we can use that and figure out that whatever these clouds are, we're looking at clouds that are up 50, 60, 70 kilometers, depending on the night and the season. From that, we start inferring that well, the orbiters that can measure the composition do see water-ice up to around 50 kilometers sometimes. But by the time you're above that, it's almost always CO2.

Mat Kaplan: I love that you could, in part, tell how high these clouds were by watching the sun crawl across them as it set. Pythagoras would be so proud. There was a word applied to these twilight or even nighttime clouds. I imagine a lot of us have seen them here on Earth, but I had not seen the word before: noctilucent.

Mark Lemmon: Yeah, there are a couple of words that I have used for these clouds that are not quite everyday conversation. These are noctilucent clouds, night-shining, noctilucent. That describes clouds that are so high that the sun is still shining on them after it has gone from the surface and they're bright.

Mark Lemmon: They might be in the sky in the daytime, but you might miss them because they're faint. They're thin. But at night, when they're the only things that the sun is shining on, you cannot miss them.

Mark Lemmon: And so, they're very commonly seen from high latitudes. They're clouds above the troposphere. The ones on the troposphere, the sun sets on, close enough at the same time that they never get outstandingly bright. They make for beautiful sunsets, but they're not noctilucent clouds. These ones that are up in the mesosphere, basically up at similar altitudes on Earth to where we see them on Mars, those clouds are the noctilucent clouds.

Mark Lemmon: Then among the noctilucent clouds, you can also see clouds that are iridescent. Iridescence is when you see the wavy colors across the clouds. You can see that in the daytime too, if you find clouds that have ... All the particles have the same formation history, so usually young clouds. Then you have a whole bunch of particles of the same or almost the same size. They scatter light the same way. This cloud that would otherwise be white suddenly has red and green and blue parts to it.

Mark Lemmon: It's still just water, typically, when you see it in the daytime on Earth. Well, when you see that iridescent cloud that is also noctilucent, the name that we have for that on Earth are nacreous clouds.

Mat Kaplan: Nacreous?

Mark Lemmon: Nacreous clouds.

Mat Kaplan: Okay.

Mark Lemmon: The less highfalutin name that we have for those on Earth is mother of pearl clouds.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, yes. Now that I saw. I have seen these. I hope all of you out there have seen them. Really, I'm not kidding, folks, you need to take a look at some of these images, at least one of them, of these iridescent or mother of pearl clouds in the high atmosphere of Mars. It is just sublimely beautiful. Really, science at its artistic best.

Mark Lemmon: Yeah, I'd never seen colors like that on Mars, except in colorful things that we took with us. To actually see Mars making colors like that was awesome.

Mat Kaplan: I got a question for you that I wasn't expecting to ask because it didn't occur to me. I was many, many years ago in the southwest, hot, dry day, and looked up at the sky with a whole bunch of other people who were there and we saw color in the sky. We couldn't see clouds, at least I don't remember seeing clouds, but there were the same sorts of faint color that we could see. Does that make any sense to you? Is that a phenomenon that you are familiar with?

Mark Lemmon: I've certainly seen ice clouds, sometimes colorful ones, in a similar environment, anywhere from Tucson to here, a more humid version of that, Texas. The clouds that do that would likely be very thin clouds with very uniform particle sizes. So you basically don't necessarily see the white of the cloud. Then you see the shimmering colors from it. That's just telling you that you have ice particles that are all about the same size. This is probably ... I'm just guessing here. I didn't see what you saw. Probably very close to the tropopause. So, again, about 10 kilometers.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you for helping to possibly solve a decades-old mystery, at least a mystery to me. If I was standing on Mars under some of these iridescent clouds, looking up at them through my helmet faceplate, would I with my naked eye be able to see some of these colors, or is that something that I need instrumentation for?

Mark Lemmon: I find it very difficult to predict the details of what you would see when you look at anything through a picture and then look at it with your own eyes. It's always surprising to go from one to the other. But in my experience, yeah, those are colors that you would see. It wouldn't look precisely like the picture because we would perceive things differently.

Mark Lemmon: But again we would be in a dark environment with a slightly bright sky and then have these shimmering colors above us. Those were not super processed to bring out things that we would not otherwise see. Those were calibrated images. Yeah, they're displayed a certain way, but you have that problem whenever you show an image on a monitor, that kind of issue, but there was no particular effort put into making those clouds look more spectacular than they are. They just are like that.

Mark Lemmon: When you get away from looking towards sunset, the pictures with the colors are looking above the area where the sunset previously. When you look away from there, you don't get the iridescence nearly as much. It fades off pretty quickly. Then you tend to see essentially the whitish clouds and the tannish and darkening sky. So the pictures taken in other directions don't have those shimmering colors.

Mat Kaplan: I've got to think that ... I've got to hope anyway ... that in some number of decades, there are going to be Martians on Mars, human Martians, who will be out on expeditions and maybe just love the thought that, hey, I got to see some mother of pearl clouds the other day.

Mat Kaplan: When you were on the show 10 years ago, we also talked about fog as it was seen apparently by Phoenix with its great surface STEREO imager that you were in charge of. You mentioned it again now. Is fog these clouds that are right down on the surface? Are we seeing this as a fairly common occurrence on Mars?

Mark Lemmon: Fog is not uncommon. It is common in some places. It is not likely at all around the Curiosity. That would be a major surprise if we saw the fog there someday. But at higher northern latitudes, we would not be surprised to see fog. If we were up near Viking 2, we would expect to see fog.

Mark Lemmon: Around Perseverance, I haven't looked at the details. I'm personally not expecting to see fog there, but I haven't proven that that is the right expectation. I don't think it's a high enough latitude yet to expect it. But the higher latitudes, yes, you would expect it.

Mat Kaplan: Another thing that happened 10 years ago, you couldn't say for sure that it snows on Mars, that there's snow fall. How about now?

Mark Lemmon: I'm pretty confident that it snows somewhere at a high enough latitude.

Mat Kaplan: I guess you could have the polar ice caps just forming, I mean just condensing out, reverse- sublimation, I suppose. But you're thinking that they're actually ... I mean water-ice snow or carbon dioxide snow, or some combination of the two.

Mark Lemmon: Just going from memory, I think that there has been some evidence for carbon dioxide snow at the south pole, but that happens in the polar night. Whether or not there is water-ice snow as opposed to just condensation, basically giant frost piles, maybe an open question, but I think that it's fairly likely that snow contributes.

Mat Kaplan: White Christmas on Mars, yeah.

Mark Lemmon: Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: One of the other things that we talked about in the past, and still I love to talk about, is how knowing that these familiar phenomena taking place on Mars makes that otherwise still very exotic world seem so much more Earth-like. There's a real emotional impact to this, isn't there?

Mark Lemmon: Oh, there is. I mean at a technical level, I spend my time studying usually dust on Mars, but stuff in the Martian atmosphere. There are a lot of technical things that I can do. But one of the things that I really enjoy doing going beyond the science of it and just talking to people, bringing it to people, that's why I write or contribute to press releases like the one at JPL, there are many things you can do to show Mars as this dynamic place.

Mark Lemmon: The familiar happens there. It's not just a bunch of rocks sitting there. I know a lot of people who are really excited about all those rocks sitting there, but those rocks going on around them, dust devils sweeping across and blowing things around, and dust storms coming across the entire landscape and clouds going overhead, now we know those clouds are even shining with cool colors sometimes, it's a cooler place than we sometimes give it credit for being.

Mat Kaplan: I'm glad you mentioned the dust devils because I still love to see them, of course, especially in movies. I guess Phoenix has not had enough of them, though. There was this story recently, I'd love to hear your comments about, where apparently somebody decided let's sprinkle some dirt, some sand on Phoenix's solar panels, and it actually ... They saw some of the dust that was collecting there swept away.

Mark Lemmon: So the InSight solar panels, yeah.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, I'm sorry. Yeah, of course. Of course, InSight.

Mark Lemmon: Yeah. Same engineering, but different problem.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Mark Lemmon: So, yeah, InSight has been sitting there getting dustier and dustier as we have gone along with this mission. With Spirit, we went for 400 days of the solar panels getting dustier every single day before all of a sudden they got cleaned off one day by wind gusts. With Opportunity, the wind gust came more often, but it got cleaned off pretty regularly. With Spirit, it got cleaned off almost every Mars year, though there was one exception and Spirit did not survive that winter.

Mark Lemmon: InSight has not been cleaned. The solar panels are a different design. They're even a different design from the Phoenix Lander. For whatever reason, the dust that has stuck to them has not come off again.

Mark Lemmon: There has been winds. There have been dust devils. We have a meteorology experiment. We can measure these big vortices. We can measure these strong winds. We can even see dust being picked up off of the surface and sand blow around on the surface, and almost nothing happens to the array.

Mark Lemmon: I mean there was one day early in the mission, like sol 50 or 60, where we saw a tiny part of the array get slightly cleaner with one particular wind gust. It was like, "Okay, cool. Wind gusts clean things. We're good." A year later, it hasn't happened again. A year after that, it hasn't happened again.

Mark Lemmon: So at this point, the engineers and the people in charge of the mission are a little desperate, because we have a fraction of the energy that we had before, which when we started was way more than we needed. Now it is restricting the science that can be done.

Mark Lemmon: So the idea is to do these little tests that if you think about winds cleaning things in a natural environment, yeah, you can blow dust off with something, but a lot of dust is sticky. So if you're doing it in your house, sometimes you want to use a rag or something. Well, we don't have access to that. If you look at natural environments that get cleaned, the thing that those environments frequently have in common, if it's not water, is sand.

Mark Lemmon: Because the dust is sticky, it is small, the wind goes right over it like it's not even there. So you blow on the surface, a lot of the dust never comes up. The sand moves across the surface and it bounces and bounces and bounces and every dust particle that gets hit never comes back. So that's the general idea with sand-cleaning something. I have no idea how far it'll go.

Mat Kaplan: All right. Well, best of luck to all of you on that mission, of course. Maybe a particularly strong dust devil, a wizard of Oz strength one, at least on a Mars scale, will help a little more. Let's talk a little bit more about dust since you do study it so carefully.

Mat Kaplan: Just two weeks ago, I was talking with Brian Keating about dust getting in the way of his examination of the origins of the universe. It doesn't really get in your way. I mean do you still find it as fascinating as ever? Do you think it's going to continue to be a problem, especially when humans get up to the Red Planet and decide to live there?

Mark Lemmon: Well, I think it will be a fact of life from ours. You will not go to Mars with a robot or with people without being concerned about dust and how you're going to deal with it. Some of the early efforts, the concern with dust was simply, well, that's going to be the limit to the mission. Spirit and Opportunity were only 90-day missions.

Mark Lemmon: So we learned that maybe we were a little pessimistic, but we also see that it is a threat. It has ended ... Well, everything, solar panels that we've sent that's mission is complete is because of that.

Mark Lemmon: We're going to have to deal with the dust in the sky, the dust on surfaces, the dust that people bring in. That's one of the motivations for finding out more about the physical nature of the dust. If you do anything outside and come in, you're going to bring in dust. The Apollo astronauts complained about that with the moon. That's going to be an issue with Mars as well. The Martian dust is magnetic. There'll probably be computers involved in Mars exploration. I'm just guessing here.

Mat Kaplan: You think?

Mark Lemmon: I am not trying to use a computer in an environment full of magnetic dust, but I'm not thinking that that's the best combination. I'm not trying to suggest that these are insoluble problems. I just think that this is going to be a big concern. And so, we're studying the physical nature of the dust, but we're also studying the meteorology.

Mark Lemmon: We're not worried about an event like in The Martian where the dust storm comes in and blows over giant structures, but the dust is still kicked up, the sand at the base of the dust devil is kicked up. And so, if you're out there, your piece of equipment is out there, whatever, it gets sandblasted. We know that things can have long lifetimes, but we also know that those lifetimes can be limited by the dust and the accumulation of things.

Mark Lemmon: I think it is necessary to understand it as a factor in the environment that we will face. Then beyond that, I think that it's just an interesting part of that environment, that being able to look at the weather instruments and see that there's a vortex, a dip in the pressure over time, and then that dip in the pressure goes away, and maybe you've also gotten a measurement that the wind was going to the left and then it went to the right and then it went back to the left.

Mark Lemmon: If you're a meteorologist, you can do a lot with that. But it's so much easier to visualize what happens on Mars when you can see that that vortex, that low pressure system, that tiny low pressure system has winds that move sand and pick up dust and blow them around. And so, we see these columns of dust moving across the landscape.

Mark Lemmon: Sometimes at the Curiosity site, there's not that much dust to pick up. So they're hard to see most of the time, but they're still there. At Spirit, we have wonderful pictures of these columns of dust moving across the landscape.

Mark Lemmon: Then at Perseverance, it's just been crazy that we were just starting to get into our attempts to monitor and track dust devils and see where they were and when they occurred. They just kept showing up in all the images that were taken for other reasons that we had years at InSight, where even though we see the signatures of a vortex in the meteorological data, we have not seen a dust devil.

Mat Kaplan: Wow!

Mark Lemmon: Perseverance, we just see dust devils all the time. Of course, it's a great season for that there right now.

Mat Kaplan: I got one other dusty question for you. Are we beginning to understand the forces behind those dust storms that come now and then, on a semi-regular basis at least, that completely envelop Mars?

Mark Lemmon: Well, until you got to the last part, the answer was pretty much yes, that we understand the development of dust storms reasonably well. There are lots of things that go into them. The cocktail of making a dust storm can be reproduced in the models pretty reliably, and the models can put the dust storms in the right places. Their frequencies in the models on Mars match where we actually see them on Mars.

Mark Lemmon: What makes a Martian dust storm decide to become a really large regional storm or to even merge regional storms and become this global event, I really don't think we're nearly there yet. That's something that we have to understand. If you're worried about whether there's going to be a global dust storm affecting your mission in the next year, that's not something we can predict right now.

Mat Kaplan: Wow! I want to go a little bit further out in the solar system. You've been around long enough that you've done work with Jupiter's clouds during the Galileo mission, the Galileo probe that plunged down through that atmosphere. Are you looking forward to the arrival of Dragonfly at Saturn's moon Titan? I know that you've had a lot of curiosity about that, that moon that has that atmosphere that is so much thicker, not only the thicker than what we have seen on Mars but then what we have here on Earth.

Mark Lemmon: Yeah, I'm loving the idea of Dragonfly. That is just going to be incredible to see from that kind of perspective what it's like on Titan. I got started as a scientist with looking at Titan even before I did some work with Jupiter, used Hubble Space Telescope trying to find clouds, and eventually we did find some clouds with Hubble. I did some other work related to that just as a graduate student and as a post-doc. So being able to go back and see it again and see new things, I mean imagine Huygens and what it did, and then think about how much [inaudible 00:35:44] Dragonfly can be.

Mat Kaplan: Very tantalizing. I got one other thing to ask you about. You wrote a great article for us some years ago, I think it was encouraged by my former beloved colleague Emily Lakdawalla, about what it takes to get great photos on another world. We've talked with your colleague, another famous planetary photographer, Jim Bell about this. What should I consider if I want to take the perfect snapshot on Mars, or elsewhere for that matter?

Mark Lemmon: Well, yeah, trying to take that picture is certainly something that Jim, I, a lot of other people put a lot of thought into the themes from some of the earlier work, because it takes a village. You don't just pick up your camera and take a picture. You have to consider that it's part of a very elaborate system that has lots of ways that that system can fail, whether it's trying to command a motor to move like the mast that your camera is on ... It has to be the right temperature or it's not going to move ... the electronics of your camera. Probably you don't want to warm up too abruptly. Electronics don't like large temperature changes. So you have to make sure that the heating there is right. So a lot of engineering involved.

Mark Lemmon: Then there's just the distribution of jobs across the mission, that I come up with an idea, I say, "Okay, I want to take a picture of the sunset." Here's where the sunset is. I can use some software to figure out exactly which direction the camera has to be pointed, or I can just look at a previous image, and I can compose it even. I can look at the mosaic that we took during the day and say, "Here's what we see. Here's where the sun will be. Here's the set of pictures that I want."

Mark Lemmon: Then we need someone to say, "Well, okay, if you want your pictures to fall there, then we need the command that moves the motor that's driving the camera here, there, and the other place." So we have these payload uplink leads that take these ideas and make them into real sequences.

Mark Lemmon: Then we basically go into a whole series of committee meetings with scientists from other groups. Well, I want the sunset picture, but Stephanie over there wants to get a picture of this rock. Probably not at sunset, but there's a finite amount of energy. There's a finite amount of time we can put into planning things.

Mark Lemmon: So sometimes you just don't have the mental band path, the mental resources available to fill up a rover day completely because some of the things are complex. Sometimes you don't have the power. Sometimes you have everything and it works.

Mark Lemmon: So we have to get through all of those committee meetings. Then finally this computer version of the command gets sent up to the rover and it will execute it. Hopefully the execution goes okay. Then the rover will wait for an orbiter to fly overhead.

Mark Lemmon: The result, the image in compressed form, will get beamed up to the orbiter. The orbiter will eventually turn around and send it to Earth, goes through lot of different places on Earth. Then finally I get my pictures and I can use software to manipulate them, make them into mosaics and things like that.

Mat Kaplan: Not point and shoot. I will keep this in mind every time I look at one of these beautiful images from Mars and elsewhere from you and others, and have some respect for the work that has gone into it.

Mark Lemmon: Take a look occasionally at that little photo credit down there. That doesn't even do anything justice, but it'll say NASA JPL, Caltech, ASU, SSI if I'm involved. That doesn't even give you a sense of the large number of people that it took to actually make that really happen. But, yeah, those pictures represent the work of a lot of people.

Mat Kaplan: I read that you were doing a lot of this work from home, even before the pandemic forced a whole lot of us to join you working from home. How does it feel to sit at your breakfast table or whatever and work with spacecraft on another world?

Mark Lemmon: Oh, it's great. The commute is excellent because the Martian day is different for ours and the rovers are in different places. Who knows what time of day we're going to get data that I'm interested in. I can wake up in the morning, start some coffee, and sit down and catch up on things right away.

Mark Lemmon: We've had the ability to do that from home for a long time. These missions have been developed. Ever since Spirit and Opportunity outlived their 90 days, we realized that people had to go home. They couldn't stay at JPL. When I was at Texas A&M, connecting from there was no different from connecting from home. So I frequently took advantage of working from home even then. Then I became someone who worked from home full time about three years ago.

Mark Lemmon: I have to do some things to try and keep my home life separate from my work life, that it is something to find a lot of time working. I think a lot of people fall into that naturally when home becomes work, and vice-versa.

Mat Kaplan: Tell me about it, yeah.

Mark Lemmon: Yeah. We power through and we find ways to balance our lives again.

Mat Kaplan: Mark, I like to say to astronomers clear skies. I guess that's not exactly what you want to hear in your line of business, in your arm of planetary science. But just the same. I hope that you'll be able to keep up this great work and sharing it with us for many more years to come and maybe for many other worlds. Thank you so much. It's been great talking to you and getting this update.

Mark Lemmon: Well, thank you.

Mat Kaplan: Space Science Institute senior research scientist Mark Lemmon. You'll find great images and much more on this week's episode page, planetary.org/radio. I'll be right back with Bruce.

Bill Nye: Bill Nye The Planetary Guy here. The threat of a deadly asteroid impact is real. The answer to preventing it? Science. You as a Planetary Society supporter, you're part of our mission to save humankind from the only large-scale natural disaster that could one day be prevented. I'm talking about potentially dangerous asteroids and comets. We call them near-earth objects or NEOs.

Bill Nye: The Planetary Society supports dedicated NEO finders and trackers through our Shoemaker Near-Earth Objects grant program. We're getting ready to award our next round of grants. We anticipate a stack of worthy requests from talented astronomers around the world.

Bill Nye: You can become part of this mission with a gift in any amount. Visit planetary.org/neo. When you give today, your contribution will be matched up to $25,000, thanks to a society member who cares deeply about planetary defense. Together, we can defend Earth. Join the search at planetary.org/neo today. We're just trying to save the world.

Mat Kaplan: It is time for What's Up on Planetary Radio. Here is the chief scientist of The Planetary Society, Bruce Betts, is with us once again. Hi there. Welcome. Good evening.

Bruce Betts: Hello. Hey there, hi there, and ho there.

Mat Kaplan: I figured good evening would be a good lead-in for giving us that tour of the night sky that you always provide.

Bruce Betts: It is a good evening, at least if it's not cloudy for you. There'll be a lot of good evenings coming up. If you look low in the west, certainly after sunset, you'll be able to see super bright Venus shining there. It's gotten fairly easy to see if you have any kind of decent view to the western horizon.

Bruce Betts: Above Venus is a much dimmer, reddish Mars, and they will be getting closer and closer together until July 12th, when we'll be snuggling with each other. In the middle of the night, Jupiter looking really bright and Saturn looking yellowish rising in the middle of the night in the east and off high in the south by pre-dawn.

Bruce Betts: To complete our naked eye planet visibility, we've even gotten Mercury making an apparition low in the pre-dawn east. So all five planets you can see without a telescope fairly easily.

Mat Kaplan: Very impressive.

Bruce Betts: I'll add a couple cute lineups as well. We've got Venus, Pollux, and Castor. The Gemini twin stars are kind of in a nice line on June 24th and then kind of align after that, and the moon hanging out with Jupiter and Saturn on June 28th.

Mat Kaplan: Do you remember the day that we spent at the Roman forum, when you were a shooting random space fact videos, and I helped and then I went off to look at the forum?

Bruce Betts: Yes, I do.

Mat Kaplan: You can still see what is left of the sculptures of Castor and Pollux in their, I assume, temple there in the forum. It was very exciting.

Bruce Betts: We shot a random space fact video with Castor and Pollock's temple, or what's left of it, in the background. In fact, it even involved my evil twin Ecurb. But alas, we digress.

Bruce Betts: We move on to do this week in space history. Hey, it was two years ago this week that LightSail 2 launched aboard of Falcon Heavy, and we're still up there solar sailing two years later. So that's exciting.

Mat Kaplan: And looking good. I mean things are still healthy. Is there any degradation?

Bruce Betts: There is. It's getting a little fuzzier in the brain. The sail has got more crinkles and it has a few spots that look like the aluminized part is delaminating. I've got an article coming out on the 25th on our website at planetary.org, a longer update about what we're doing on the extended mission.

Mat Kaplan: A little fuzzier in the brain. Aren't we all?

Bruce Betts: Huh?

Mat Kaplan: Exactly.

Bruce Betts: I'm going to darken the mood in remembering the passing of the Soyuz 11 crew, which occurred this week in 1971, when their cabin depressurized due to a faulty valve. Georgy Dobrovolsky, Vladislav Volkov, and Viktor Patsayev all perished and are the only three people to have perished above the Von Karman Line, to have died in space. We move on to Random Space Fact.

Bruce Betts: So that Soyuz 11 crew, I found out something I didn't realize. One, credit is due. They were the first to live on board a space station, Salyut 1, for 22 days. But they were actually the backup crew until just a couple of days before launch. Have you ever heard this?

Mat Kaplan: Wow! No.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. An x-ray of one of the primary crews' lungs showed what they thought was tuberculosis indications, a dark spot on the x-ray. So they actually chose to completely go with the backup crew and the primary crew, Leonov, Kubasov, and Kolodin, were sidelined. It turned out that Kubasov, who they thought had tuberculosis, just had a cold.

Mat Kaplan: Oh my gosh. There but for the grace of the Russian space agency, I guess, or the Soviet space agency at that time. That's quite a story.

Bruce Betts: One of those trippy stories. Two of the three primary crew went on to fly on Apollo-Soyuz. All right, we move on to happier times and the trivia contest. Who holds the record for the most launches to space from Earth at seven? How'd we do, Mat?

Mat Kaplan: Let me give you the rhyming answer to this, then we can talk a little bit more about it, because it's tripped up quite a few people actually. [Jean Lewin 00:47:25] in Washington submitted, "Jerry Ross reached his seventh space launch all from this marvel blue, but Franklin Chang-Diaz kept up that pace in seven, he completed two. Jerry Ross flew in three different craft. Chang-Diaz added Discovery. So though they are tied both with seven in trips, in ships, Diaz leads four to three."

Bruce Betts: Nice. Not only poetry, but an additional random space fact. I like it.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you very much, Jean. Here's our winner, first-time winner, Judy [Anglesberg 00:47:59] in New Jersey, the Garden State. It really is if you get out of Newark and places like that. Anyway, Judy got it right with Jerry Ross and Franklin Chang-Diaz. She adds to that, "Greetings Earthlings and astrophage," a little tip of the space helmet there to our friend Andy Ware and his new book.

Mat Kaplan: Congrats, Judy. You have one yourself both a Planetary Radio t-shirt and a copy of Brian Keating's book that we talked about a couple of weeks ago, Losing the Nobel Prize.

Mat Kaplan: There are several people who noted John Young's lunar launch. If you count that, it would have put him at seven as well. But then you did address that when you posed this question a couple of weeks ago.

Bruce Betts: Launches to space from Earth. But, yeah, show-offs also count their launches from the surface of the moon.

Mat Kaplan: Joe [Putray 00:48:53] also from New Jersey. "I expect they have more frequent flyer miles than most countries' entire populations." I suppose. I'll think about that, Joe.

Mat Kaplan: Ian Gilroy in Australia wants to know if I need to declare a conflict of interest because Franklin Chang-Diaz is, of course, also the founder of the Ad Astra Rocket company. He hears me give them a plug each time I sign off the show. No, conflict of interest. I love Ad Astra. I've been there, I love what they do. No, forget it, Ian. I'm not knuckling under.

Mat Kaplan: Edwin King in the UK. "Ross may or may not also jointly hold the US record for number of EVAs with Michael Lopez-Alegria. Lopez-Alegria definitely has 10. Ross has a confirmed nine, but one of his missions was for the Department of Defense and is still classified."

Bruce Betts: Ooh, spooky.

Mat Kaplan: It could be. It could be. Finally, this from our Poet Laureate Dave Fairchild. He didn't quite get it right, because like so many of you, he only identified Jerry Ross. But here was his submission. It's still a nice tribute to Jerry.

Mat Kaplan: "Seven times he flew to space and seven he came back. 60 hours EVA, he really had the knack of launching things and fixing things, and that includes the Hubble. I present you Jerry Ross of whom there is no double."

Bruce Betts: Yay! Unless it's Franklin Chang-Diaz.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, Dave.

Bruce Betts: We go to constellations land. What is the only one of the 88 official IAU constellations named for an actual historic person? Named for an actual person, what's the only constellation of the official constellations? Go to planetary.org/radiocontest.

Mat Kaplan: So that leaves out Betts and Doug, because you're not yet one of the official [crosstalk 00:50:52].

Bruce Betts: It's just unofficial, but important.

Mat Kaplan: You have this time until the 30th. That would be June 30th at 8:00 AM, Pacific time, to get us the answer. And I have another copy of that great book, the one I was raving about last week, Carbon: One Atom's Odyssey by John Barnett. It is published by No Starch Press. This will also go to the winner. It is gorgeous. I think whoever gets this, whether you win it from us or get it on your own, will probably display it very proudly and enjoy his wonderful drawings. We're done.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody. Go up there and look up the night sky and think about windy planets. Thank you. Good night.

Mat Kaplan: Windy planets. Yeah, of course there are some, but Bruce mentions this because just before we started, my grandson informed me that he's now going to call Uranus and Neptune the windy planets because they just look that way. I said, "Yeah, not bad." Do you agree, planetary scientist?

Bruce Betts: I do. I do. Neptune even has the fastest measured winds in the solar system. So, yeah, windy planets.

Mat Kaplan: There you go, the chief scientist of The Planetary Society, Bruce Betts, is in full agreement with the equally distinguished five-year-old Rowan as we close out this edition of What's Up.

Mat Kaplan: Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by its members who see all sorts of wonders in the sky. Share their vision at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Jason Davis are our associate producers. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Peter Schlosser. Ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth