Planetary Radio • Mar 23, 2022

Legendary space physics pioneer Margaret Kivelson

On This Episode

Margaret Kivelson

Distinguished Professor of Space Physics, Emerita in the Department of Earth and Space Sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

At 93, Margaret Kivelson is still at the center of space science and policy. In this charming conversation she shares anecdotes about her early life, how she entered the new field of space physics and some of her groundbreaking work, including discovery of convincing evidence for a saltwater ocean under the ice on Jupiter’s moon Europa. Bruce and Mat offer another great prize from Chop Shop in this week’s What’s Up space trivia contest.

Related Links

- “The rest of the solar system” by Margaret Kivelson (PDF)

- AIP oral history interview with Margaret Kivelson

- Margaret Kivelson’s “Introduction to space physics”

- “The Planetary Report” March Equinox 2022: Ocean Worlds

- The Downlink

- Subscribe to the monthly Planetary Radio newsletter

Trivia Contest

This Week’s Question:

What was the first European Space Agency to use ion (electric) propulsion?

This Week’s Prize:

A chic Planetary Society Your Place in Space t-shirt from Chop Shop.

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, March 30 at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

What were the first words spoken from the Moon? Who said them? These were the words spoken when any portion of the Lunar Module made contact with the surface.

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the Mar. 9, 2022 space trivia contest:

What is the approximate ratio of the Mars surface escape velocity to Earth’s surface escape velocity?

Answer:

The ratio of Mars surface escape velocity to Earth’s surface escape velocity is about .45.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: Legendary space physicist, Margaret Kivelson, this week on Planetary Radio.

Mat Kaplan: Welcome. I'm Mat Kaplan of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond.

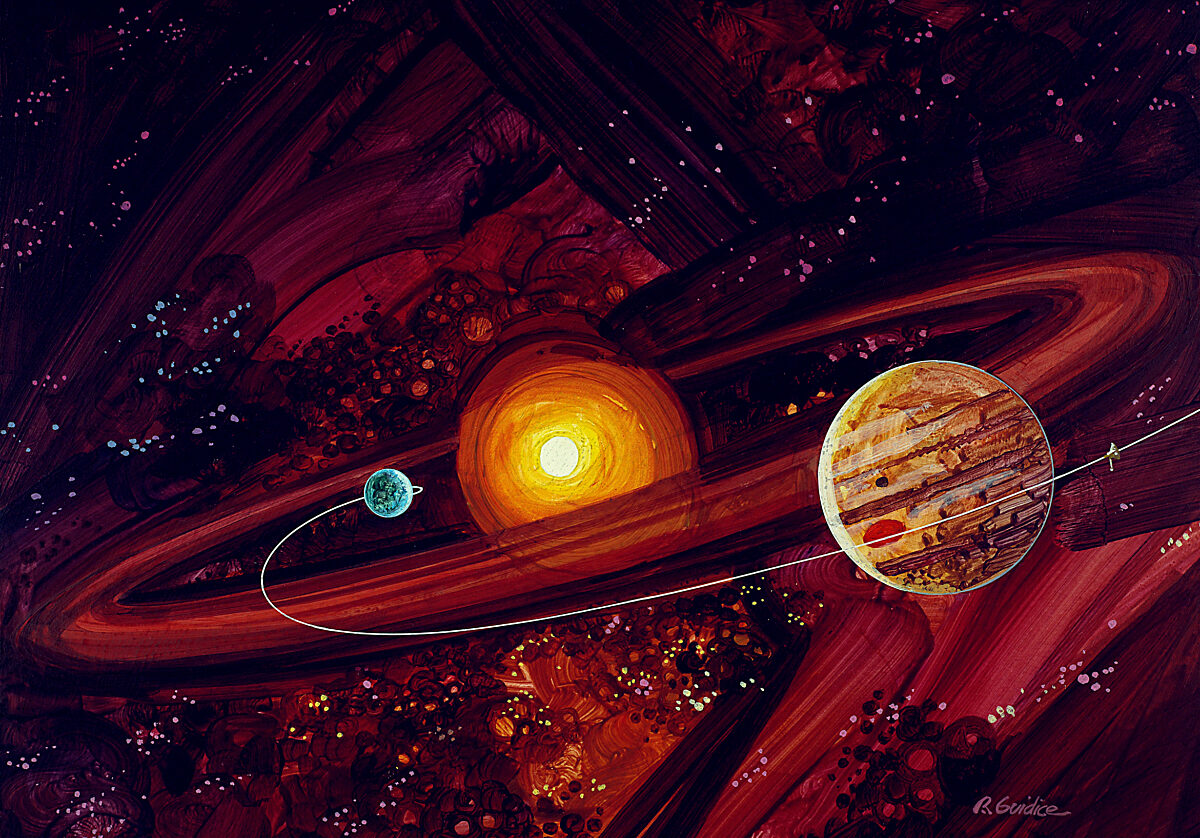

Mat Kaplan: Do you know why we're nearly sure there's a vast ocean under the thick ice that surrounds Jupiter's moon, Europa? It's because Margaret Kivelson and a handful of her colleagues convince NASA that there should be a magnetometer on the Galileo orbiter. And that just begins to capture the contributions made by this 93-year-old pioneer. Oh, yeah, she also worked on Pioneer 10 and 11.

Mat Kaplan: You're going to love my conversation with her. I guarantee it. Down at the other end of the show waits The Planetary Society's chief scientist, Bruce Betts, will tell us about the night sky, review a couple of this weekend's space history milestones, drop a random space fact on us and give you the chance to win another great prize from The Planetary Society and Chop Shop in this week's space trivia contest.

Mat Kaplan: Who doesn't love a tiny flying machine on Mars? Would you believe Ingenuity has now completed 21 flights? It's still in great condition. And it's just been given a big mission extension, providing overhead reconnaissance Perseverance rover. That's the lead story in the March 18 edition of the downlink, The Planetary Society's free weekly newsletter.

Mat Kaplan: Make that five, five asteroids that have impacted Earth after tracking predicted their fiery ends. That's planetary defense progress, right? And by the way, no earthlings were harmed by the arrival. Not this time. There's much more waiting for you at planetary.org/downlink including a beautiful image of our moon's far side taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Mat Kaplan: You can also meet all of our new STEP grant winners, including the two awardees I talked with last week on Planetary Radio.

Mat Kaplan: A magnetometer does exactly what its name implies. It measures the strength of a magnetic field. Margaret Kivelson fought to have one included on the Galileo spacecraft before it's October 1989 ride into space aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis.

Mat Kaplan: The spacecraft reached Jupiter six years later where, in spite of not fully deployed main antenna, it began delivering magnificent data from the planet and its moons. To the surprise of scientists, that tiny magnetometer detected a magnetic field surrounding Europa where none was expected.

Mat Kaplan: The celebration came when a later measurement found the field had inverted. It fit thinking that the moon had no intrinsic magnetic field of its own, but that one was being induced by Jupiter's mighty field. How is this possible? Because as nearly all planetary scientists now believe, there is a deep, salty ocean hidden by a thick layer of surface ice.

Mat Kaplan: Margaret most definitely did not stop there. As you'll hear, she is preparing to return to Europa as the science team leader for the magnetometer that will be carried by the Europa Clipper. And she's part of the European Space Agency's JUICE mission to Jupiter's icy moons, Cassini, Pioneers 10 and 11, Themis, and other missions have benefited from her participation. She chairs the Space Studies Board for the National Academies in the United States, and is a member of NASA's Advisory Board.

Mat Kaplan: The American Geophysical Union, the American Physical Society, the Royal Astronomical Society, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science have all made her one of their fellows. And she is the recipient of the American Astronomical Society's Division of Planetary Sciences Kuiper Prize.

Mat Kaplan: I could go on, but you'll have an even better time listening to my recent conversation with Margaret. She spoke to me from her Southern California home, not far from UCLA, where she is distinguished professor of Space Physics Emerita in the Department of Earth and Space Sciences.

Mat Kaplan: Margaret Kivelson, it is indeed a great honor to be able to speak to you on Planetary Radio. And I so look forward to talking to about this marvelous career that you have led and are still leading. Still very busy here well into the 21st century. Thank you for joining us.

Margaret Kivelson: Well, pleasure to be with you.

Mat Kaplan: There's a fascinating 2020 American Institute of Physics Oral History Interview with you by Joanna Behrman or Behrman, which is quite good. But even more highly, I recommend reading your own delightful contribution to it. Well, I guess it was first published in advance and then was picked up by the annual review of Earth and Planetary Sciences.

Mat Kaplan: So bear with me, I normally wouldn't read anything this long, but I'm so charmed by it. In it, you say, "I did not choose to be a space physicist. However, I was lucky enough to stumble into the field during its scientific infancy when the many fundamental processes that link different plasma regimes accelerate particles to relativistic energies, and produce natural phenomena such as Aurora and geomagnetic activity were first being explored in situ. I can take credit only for saying yes when offered opportunities to contribute to space science. Involvement in spacecraft missions, interactions with colleagues, well versed in the fundamentals of the field, and exposure to clever students provided stimulation and challenges that gave me remarkable opportunities to participate in unraveling some of the mysteries of space."

Mat Kaplan: Beautifully written, first of all. My impression is that you gave as good as you got, that you are as prized by your collaborators, your colleagues, and your students as you apparently treasure them.

Margaret Kivelson: Well, of course, that's one of the wonderful things about being in science is the people you interact with. And I've certainly enjoyed that part of my career immensely.

Mat Kaplan: Let me give people one more, much shorter quote from that paper. It may seem ironic for me, a space plasma physicist, to be asked to write an introductory review article for a journal on earth and planetary sciences. I tried to understand the properties of systems filled with almost nothing.

Margaret Kivelson: Right, the plasmas, the charged particle gases that I study have densities that are orders of magnitude smaller than the density of laboratory vacuums.

Mat Kaplan: I don't know of anybody who has made more out of nothing than you.

Margaret Kivelson: Well, that's a strong statement. But I've made some contributions. And that's been a lot of fun.

Mat Kaplan: If you don't mind, going back to the start, your childhood seems to have been a fairly happy one, full of intellectual and cultural stimulation. Am I right? And if so, did this help to set you on your course?

Margaret Kivelson: Well, I'm sure that growing up in a community and a family that valued intellectual pursuits had considerable effect on me. And of course, I lived in New York City in the middle of Manhattan. So I was exposed to all sorts of things while growing up. So, yeah, there was a lot of childhood influence and going into intellectual endeavors.

Mat Kaplan: There's so much we'll have to skip over in this relatively brief conversation. I'm just going to say again, I hope people will read the oral history and that paper that you wrote as well to fill in some of the gaps.

Mat Kaplan: I'm going to jump forward. You had your choice of colleges, so long as they were women's colleges, because after all, that's what was available, I guess, at the time. Why did you choose Radcliffe? Apparently, you were impressed with some other campuses?

Margaret Kivelson: Yeah, I was impressed with some other campuses. I didn't like the idea of sororities and fraternities. And my father was a Cornell graduate, he wanted me to go to Cornell. I didn't want to be in a school that was dominated, in any way, by sororities.

Margaret Kivelson: So my choice ended up between Radcliffe and Wellesley. And I actually looked at the course catalogs of both institutions. And Radcliffe, all of the classes were Harvard classes. So Harvard went on and on in sciences and had a much richer set of offerings. And that actually was what led me to choose Radcliffe. There's some people that suspect that it was because there was better access to the Harvard undergraduates, but that was my reason.

Mat Kaplan: I believe it, especially since I read that wasn't an uncle who said in light of what he expected your opportunities to be as a woman, he said, "Well, it's great you like this stuff, but you should become a dietitian."

Margaret Kivelson: Exactly. And that was one of the reasons I wound up to go to Cornell because they had a very good department in that area.

Mat Kaplan: So along came the war, World War II, and afterward, whereas you had been in these entirely segregated classes, I assume the only man in the room was the instructor, the professor, down front. Now you were in integrated courses, but you must have felt a little bit like a stranger in a strange land.

Margaret Kivelson: Well, I don't remember. I mean, there were too many men in the classes, but I never felt like a stranger.

Mat Kaplan: What led you to physics?

Margaret Kivelson: Well, first, I like math. I like to go through school. I never took physics in high school. I did take chemistry in high school and I found it very appealing. So I knew I was going to go in that direction. I'm not quite sure. I just like the fact that physics was a very mathematical subject, but it didn't require the obscure elements of mathematics. It was pretty straightforward. And I like that.

Mat Kaplan: I guess I should mention, there were some steps between academia and your own university experience. I mean, you spent some time at RAND, didn't you?

Margaret Kivelson: I was there for at least a decade, a little over a decade, yeah. And it was a great place to work but my husband took a sabbatical leave after we've been in California for a while. And we went back to Cambridge, Massachusetts. And I was interacting with people who were working with students. I just decided I liked the atmosphere of the university. And so I looked for work at UCLA. That was how I stumbled into space physics.

Mat Kaplan: We expand on that because this was a brand new field, space physics. I mean, for example, I didn't realize that you ... I knew about your involvement with Galileo that we will get to and some of your work since then. But you were involved in some of the first efforts to do good science, great physics in space. I'm thinking of like OGO, the Orbital Geophysical Observatory.

Margaret Kivelson: Right. Well, I started on the UCLA campus just by looking for any faculty member who had an opening for a physicist, and actually almost ended up going to work with somebody who was doing condensed matter physics. But then along came and offered to work with a couple of students who were doing a thesis in space physics. And I knew nothing about it, but I managed to get the job and tried to stay a little bit ahead of the students I was advising.

Margaret Kivelson: And one of them was actually working on Jupiter. And the issues related to why its radiofrequency emissions were modulated by the position of the moon Io in its orbit. And so I started getting interested in the dynamics of the Jovian system, which was a good beginning to get ready for what became the Galileo mission. But it was all just saying yes when opportunities came, even though I didn't feel I was fully qualified to do the jobs that I was asked to do.

Mat Kaplan: Apparently, weren't you told by someone at UCLA that he offered you the job but he said, "If you take this job, you're going to have almost no time for the rest of your life for at least a year?"

Margaret Kivelson: That's right. That was Paul Coleman, who I think was a member of The Planetary Society.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, good.

Margaret Kivelson: Might want to check that.

Mat Kaplan: I will look it up. I'll skip forward not to Galileo yet but those first truly pioneering spacecraft that went out to the outer solar system, Pioneers 10 and 11, which you did get to work on. And right from that point, I mean, the magnetometer work, investigating these magnetic fields became so important, and we had a lot to learn, didn't we?

Margaret Kivelson: We sure did. I mean, we really hadn't understood how a large, rapidly rotating planet would change the dynamics of a magnetosphere surrounding it. Every measurement that was made by Pioneer 10 and 11 was revealing something that we hadn't seen before. There were lots of great things to look at.

Margaret Kivelson: And it might be amusing for you to know that right now, I'm going back to Pioneer 11 data on the paper I'm writing right now with a new interpretation of an old observation that's based on what we've learned in the decades since I first published it.

Mat Kaplan: No kidding. That is fantastic. I mean, it's also evidence that we love to present on how these missions across the solar system just keep on giving, working with that data that's now, what, 60 years old, I'm trying to remember.

Margaret Kivelson: The data were acquired in '74. Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: Wow. And here's just a shot in the dark, you know that we, The Planetary Society, we help support uncovering the rediscovery of some Pioneer data because we had someone at JPL, Slava Turyshev, I believe, who was working on the so-called Pioneer anomaly, which ...

Margaret Kivelson: Oh, yeah.

Mat Kaplan: You know about that?

Margaret Kivelson: Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: Could that'd be some of the same data or was the data you're working with was that much better preserved?

Margaret Kivelson: That's available from the Planetary Data System, the data I'm working with. Yeah. I think the data that relate to the Pioneer anomaly are from the cruise period after the encounters with Jupiter and Saturn.

Mat Kaplan: That's correct. Of course. Yes. Did Pioneer 10 and 11 simply whet your and a lot of other people's appetites to go back to Jupiter and orbit?

Margaret Kivelson: Oh, absolutely. I mean, they were both flybys so there was very limited data. But it was rich and allowed us to see that there was a lot more going on than we had ever imagined.

Mat Kaplan: Would you describe it as a fight getting the magnetometer added to the Galileo spacecraft suite of instruments? Or was it just general persuasion? I know it was a lower priority than some of the other instruments.

Margaret Kivelson: Yeah, it continues to be a problem to people. Magnetometer is a small instrument. So the impact on the critical issues of a spacecraft, mass, cost, power, those impacts are rather small compared with many of the other instruments. But in order to operate a magnetometer, you have to get it away from spacecraft sources of magnetism. So then you have to have a boom and it gets more and more complicated.

Margaret Kivelson: And I think that's why there's a reluctance to add a magnetometer. But I think that since Galileo discovered compelling evidence of oceans in the moons of Jupiter using a magnetometer, it's become a lot less difficult to get a magnetometer onto a planetary mission.

Mat Kaplan: We'll just remind people that when they see those wonderful images of like the Voyager spacecraft or Galileo or Cassini, that thing that's way out there on that boom, that's the magnetometer, that little box usually out on the end.

Mat Kaplan: You stole my next question there because, of course, had it not been for that magnetometer on Galileo, I have to wonder, would we now be seeing the Europa Clipper spacecraft coming together, another mission that you're involved with, to investigate that ocean?

Margaret Kivelson: Right? I don't think there was any other way to have provided such a compelling argument to go back to Europa and indeed to the JUICE mission to Ganymede. Those are really, I think, very much motivated by the Galileo evidence that there are oceans.

Mat Kaplan: I'll put in a little plug here for our quarterly magazine, The Planetary Report, because the issue that just came out as we speak is devoted to the ocean worlds of our solar system. Did anyone suspect that we would find these oceans, vast amounts of liquid water? It seems all across the solar system.

Margaret Kivelson: Actually, there are several papers speculating on oceans beneath the surface that antedate the evidence that Galileo found. It was not a total ... It should not have been a surprise. But I think that it was very surprising, but it shouldn't have been.

Mat Kaplan: You've been involved in so many missions since. I mentioned Europa Clipper or since I did, what is your involvement there?

Margaret Kivelson: Well, right now, I'm leading, what they call, the science team for the magnetometer investigation. There's a lot of work that goes into planning for a mission years before launch. Let me just say that the Europa Clipper mission will not go into orbit around Europa. That's because the radiation in the environment of Europa is extremely punishing.

Margaret Kivelson: But what has been worked out is that if the spacecraft is in orbit around Jupiter and makes multiple close passes, just dipping into the inner magnetosphere and getting out very quickly, making a pass by Europa each time that we can extract the signal of magnetic induction with very good precision.

Margaret Kivelson: And Krishan Khurana, who's one of my colleagues, has worked out the analysis of that, and there's no question we're going to be able to find out a great deal about the properties of the subsurface ocean. We have to analyze proposed tours and see if they are adequate to support the kind of investigation that we want to do. And right now, we have tours that really work very, very well.

Mat Kaplan: Here's a question that I've also asked Bob Pappalardo, leader of the Europa Clipper mission. And so I'll ask you as well, you must be finding some reassurance in the success of the Juno mission. I mean, certainly, it's fascinating science but just the fact that it has done such a good job of surviving in that awful environment near Jupiter.

Margaret Kivelson: Right. And they used the same principle, dip into the dangerous area briefly and then get out as quickly as you can. And that's enabled them to last for years now and do really good science.

Mat Kaplan: I'm reading a prepublication copy of a really terrific new book by Lindy Elkins-Tanton, who is the principal investigator for the upcoming Psyche mission, as I'm sure you know. I bet you're looking forward to that one, too. And her spacecraft will, of course, carry a magnetometer.

Mat Kaplan: And I wonder if you want to say anything about that mission in this first one ever to an asteroid that we think, anyway, is made of metal and may very well have a magnetic field.

Margaret Kivelson: Absolutely. Well, you know that Galileo passed close to asteroids on its extended tour of the solar system on route to Jupiter. Both times, the magnetometer picked up a signal as we pass the asteroid. For one of them, if the signal that we measured was actually not just fortuitously appearing at the encounter with the asteroid but actually due to the asteroid, we thought it might have a magnetic moment.

Margaret Kivelson: So I'm particularly interested in finding out what Psyche is finding because it seemed tightly improbable but not impossible. So if Psyche finds a big magnetic signature, that would be very comforting to me.

Mat Kaplan: There's another reason I brought up Lindy Elkins-Tanton. And I'll say, by the way, her new book, which is excellent, won't actually be published until June. She is the principal investigator for this mission, which has a budget of nearly a billion dollars. I think of other women who have now been achieving this level. And scientists like Linda Spilker of the Cassini mission, who's been on our show more than any other guests, project scientist for Cassini. And now back on the Voyager mission as well.

Mat Kaplan: I know a lot of these women look to the pioneers like you for opening the doors that they have now walked through, and you seem to still be right there with them.

Margaret Kivelson: Well, I'm glad to hear that in a way. They're all very impressive scientists and I'm sure they would have made it without my preceding them. But I'm always delighted to see my female colleagues take charge. They do a good job.

Mat Kaplan: Margaret has much more to share in a minute. I want to recommend a podcast to you. It's called Our Opinions Are Correct. And it's hosted by Charlie Jane Anders and Annalee Newitz.

Mat Kaplan: Every other week, Our Opinions Are Correct, a different topic related to science fiction, science, and so much in between. They've talked about everything from how to write a good fight scene to the death of the universe. Charlie Jane Anders is an award-winning author of several science fiction novels, including the recently released, Victories Greater Than Death.

Mat Kaplan: And Annalee Newitz is an award-winning science journalist who writes for The New York Times and the Atlantic. She is also the author of my favorite science fiction story written in the last few years. It's called When Robot and Crow Saved East St. Louis. Google it, you won't be sorry. But hey, I also truly love their very entertaining podcasts. Together, they befriend cosmic monsters. Subscribe to Our Opinions Are Correct on Apple Podcasts and all the other places where a great podcast can be heard.

Mat Kaplan: Did you face any particularly great challenges just because at that time, certainly even well into the '70s and '80s, you were often the only woman in the room?

Margaret Kivelson: Right. I always like to point out, that has some upsides and some downsides. And people like to talk about the downsides. They rarely talk about the upside.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Margaret Kivelson: I mean, everybody knew me. And that's a very useful thing in a professional career to be recognized. And I never had to appear twice for people to remember who I was. So I think that one has to see that there are good sides and bad sides of being an anomaly. And I guess I have a pretty positive outlook on life so I like to look at the positive things.

Margaret Kivelson: But I would say probably in terms of advancing a career as a woman, the best thing I did was to marry a man who thought I could do anything and manage to help me in every way possible to achieve my goals. So that was important.

Mat Kaplan: That's wonderful. You've had so many other collaborators, colleagues along the way, some of whom you still have relationships with, many of whom. Who stands out? Who are the people who either helped to shape your career or who you really look to as the partners who helped you do the work that you've accomplished?

Margaret Kivelson: So I'll try to address that in chronological order. I would say Paul Coleman, who was the man you were quoting who said that if I said yes about Pioneer 10 and 11, I would no longer have any free time. He was an amazing man. He really founded the space physics group at UCLA. He liked to start projects and then turn them over to colleagues, and go on and start something new. So I was the beneficiary of that. So he had an immense influence on me.

Margaret Kivelson: Then my collaborators at that time were Chris Russell and Bob McFerrin, also both at UCLA. And without them, I wouldn't have been able to do the work I did with the OGO 5 satellite that you mentioned. They were really very deeply engaged and very knowledgeable, and I learned a lot from them.

Margaret Kivelson: And then I met David Southwood, whom I mentioned before, and he is unusual and being able to do both theory and data analysis at a very high level. And that was what I wanted to do. So we started collaborating. And as I said, we've written more than 60 papers together over a lifetime, and we're still collaborating. You mentioned a Russian colleague.

Mat Kaplan: Yes, yeah, before we started recording. Actually, it was during Soviet times, right?

Margaret Kivelson: During Soviet times, her name was Valery Troitskaya. And she was the most remarkable scientist with an interest in what you could learn by looking at signals, magnetic signals on the ground, what you could learn about what's going on in space. And she taught me a new tool that I had not really appreciated. And she was also more fun than almost anybody I've ever worked with. She was a total delight. We became very good friends.

Margaret Kivelson: And more recently, Krishan Khurana and Ray Walker at UCLA have been very close colleagues with whom I've worked on many problems. And Xianzhe Jia of University of Michigan, who started as a UCLA graduate student and got interested in the interaction of magnetospheric plasmas with moons. And I've done a lot of very nice work mainly on Saturn with him, but he's the deputy team leader for the Europa Clipper magnetometer. So I continue to work very closely with him. So I've had really good colleagues.

Mat Kaplan: How does it feel to look around your profession now, to look around space science and see so many young people who you work with when they were students or graduate assistants or something like that, and see them now helping to lead the field?

Margaret Kivelson: Yeah, well, that's ... And they're no longer young ones. But they are leaders in the fields. And it's nice to think that I made a contribution to getting them going. But young and old, I keep in touch with many of them.

Margaret Kivelson: In the days, in the years, when there was no COVID, we used to meet every year at the annual December meeting of the American Geophysical Union. Krishan usually arranges a luncheon and we have 25, 28 people coming for lunch with [Markey 00:31:41]. And we do this every year and really keep in touch. It's great.

Mat Kaplan: That's wonderful. There is one more topic that I want to get to, which we could have devoted probably a half hour, an hour or two all on its own. And that is another part of what you currently stay busy with. You are the chair of the Space Studies Board in the National Academies. It comes up every now and then on our show, particularly in the space policy edition monthly version of our show. But I wonder if you could talk a little bit about the Space Studies Board, what it does and how it contributes to the advancement of space science.

Margaret Kivelson: It's something of a mystery to me how it contributes to space science because-

Mat Kaplan: I didn't expect to hear that.

Margaret Kivelson: It really does ... So let me just say that it is the senior committee of the National Academy of Sciences dealing with space physics. The functional elements are largely the committees that are formed and reported to the Space Studies Board. So there are committees on astronomy, on space, on various subcommittees that are planetary science.

Margaret Kivelson: So the Space Studies Board is responsible for setting up these standing committees that do the detailed research on what's going on in the field and what would be desirable next steps advising NASA, advising NOAA, advising the National Science Foundation on where the science is leading. So the Space Studies Board operates largely through these discipline committees.

Margaret Kivelson: But I would say the other thing that the Space Studies Board does is it convenes leaders in the field at its semiannual meetings and has a chance to interact in person with leaders in the government, in particular at NASA, in order to alert them to things that are going on that should attract attention from them. So we often suggest studies that are needed, trying to keep track of what's going on in the field, what are the opportunities, what are the problems.

Margaret Kivelson: So it's largely, as I said, through the committees but also through direct dialogue with leaders in the government that we managed to bring up potential issues to people who can do something better. We can't do anything ourselves, but we can keep an eye on what's going on in the field and where there are places, where new policies, new directions are desirable.

Mat Kaplan: In this role, the Space Studies Board sounds like it is at least complementary to the decadal studies, astrophysics, planetary science, and so on. Is there a relationship there? Or are they just-

Margaret Kivelson: Oh, yeah, we established the decadal committees. And these committees are really very influential. And we're the ones who decide who should be on the committees, who should serve on the committees, work hard to make sure that all aspects of the field are well represented by people who can be both knowledgeable and willing to put in the work, that's an immense amount of work, the decadal studies.

Margaret Kivelson: So yes, and the Space Studies Board is organized as that entire activity.

Mat Kaplan: Doesn't sound to me like there's any mystery to the influence of the Space Studies Board. It sounds very influential, actually. But ...

Margaret Kivelson: Yeah, but it's indirect.

Mat Kaplan: A gentle hand behind the scenes perhaps?

Margaret Kivelson: Well, I hope so.

Mat Kaplan: What about the international role? Isn't the Space Studies Board basically the US representative to that international group, COSPAR?

Margaret Kivelson: COSPAR, yes. The Space Studies Board is the organization that works through COSPAR on international issues, which now have some really significant disruptions through the Ukrainian war. I've just heard that Mars expresses and terminated or-

Mat Kaplan: ExoMars, right?

Margaret Kivelson: ExoMars, I mean, yeah. ExoMars.

Mat Kaplan: Very sad.

Margaret Kivelson: Very sad.

Mat Kaplan: Is it because you are chair of the Space Studies Board that you are also at least an ex officio member of the NASA Advisory Board?

Margaret Kivelson: Yes, that's right. And I should mention that the effectiveness of these national academy boards is really the result of a lot of work by the National Academy staff, in particular, the directors, at Space Studies Board directors, Colleen Hartman. And her wisdom and energy are just fundamental to the influence of the Space Studies Board. It's really been a pleasure working with her.

Mat Kaplan: Do you know that your book, Introduction to Space Physics, that you wrote quite some time ago, is still available from Amazon as an e-textbook, 3,859 to rent, 7,449 to buy?

Margaret Kivelson: Well, good, I don't have to buy it.

Mat Kaplan: Right. Well, apparently, it's still making an impression on students and others. I just have to think what I've talked to other people who've been involved with these kinds of general survey textbooks, which take on a life of their own. Is this a particular pride?

Margaret Kivelson: Oh, it's been a joy because I meet young people in the field who tell me, "I studied space physics from your textbook." And they are from all over the world. I mean, it was translated almost immediately into Chinese and I have a copy but I don't know if they got it right.

Mat Kaplan: Do you provide advice to the young people that you still cross paths with? You still have an office at UCLA where you are professor emerita. Do you have any wisdom to share with them?

Margaret Kivelson: Well, I think saying that I have wisdom is a strong statement because the world that they're approaching is very different from the world that I encountered when I was starting. I think it's a tough time to be a young scientist. There are lots of opportunities in computer science and machine learning. But in pure science, it's a much harder time than when I started, it's much more competitive.

Margaret Kivelson: But I guess I tell my students, give it your all, try to do what you want to do, but be prepared. The world is not as open and there are not as many jobs as there used to be. So that is one thing. You have to be prepared to change direction, which is what I did. I mean, I didn't start as a space physicist. So you do have to see where the world is going and be prepared to change direction. It's a very gratifying field to be in if you can make it.

Mat Kaplan: Why should a society place a lot of emphasis on pure scientific research that may never have an application that makes money?

Margaret Kivelson: Yeah. Well, that's a complicated question. I think that there are always things that society does that fundamentally raise the human spirit. And whether it be pursuing pure science or building the Cathedral of Notre Dame, it's something that takes the spirit beyond what is happening on a day-to-day basis. And I think there's a desire in humans to do something that will last. And pure science is something that is, to me, a very fundamental enhancement of the human mind that is worth doing.

Margaret Kivelson: I know a lot of people would answer, well, there's the fallout to get, I don't know Sarah and rep from what was developed for space. But I think that's nice. But I think it's actually important to seek beauty. And I find science is one way in which you can enhance the beauty of your time.

Mat Kaplan: Hear, hear. I like to quote our CEO, Bill Nye, the science guy, who talks about the PB&J of science, the passion, beauty, and joy of science.

Margaret Kivelson: Yeah, well, he expresses things so well. So give him my greetings.

Mat Kaplan: We, not long ago, lost the great Don Gurnett, a physicist who worked for so many years. And it's only been a few days since we learned that Eugene Parker passed away, after whom the Parker Solar Probe is named. I mentioned them because I know you worked with Don Burnett at some point but also because they seem to retain that that PB&J, that sense of passion and beauty and joy of science right to the end.

Mat Kaplan: I certainly sense that from you. Do you still get a kick out of new data?

Margaret Kivelson: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. New data and new opportunities, new interpretations. Yes. Wonderful.

Mat Kaplan: Margaret, it has been an absolute joy to talk to you and just to learn about your career. Again, I recommend that listeners read that paper that you wrote, which we will provide a link to on this week's show page of planetary.org/radio.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, not just for this conversation but for many decades of leadership and great science. And I hope that you're able to enjoy many more.

Margaret Kivelson: Well, thank you so much. And it's been a pleasure talking with you. You really asked great questions to make this fun.

Mat Kaplan: Time yet again for what's up with the chief scientist of The Planetary Society. It's Bruce Betts who's back with us to load us with all kinds of cosmic information. And we have another Chop Shop item to give away, the fourth in our series of six. I will keep it a secret for a few more minutes anyway of what we're doing this time. But it's anybody's Planetary Society fan or a member should be pleased by this one.

Bruce Betts: I don't even know, I'm very excited and I'm looking forward to this.

Mat Kaplan: I know, I wanted to keep you and the rest of the universe in suspense.

Bruce Betts: Well, then, let's get through it. I'm just going to keep talking about that predawn planet party. It's happening over there in the east. That's right, the predawn, that's right, planets. We've got three nicely bright planets very close together. We've got super-bright Venus that you can't miss. If you look to its upper right, you'll see reddish Mars much dimmer and then yellowish Saturn is below Venus, and over the next few weeks, it'll snuggle up by Venus, then do as close snuggle by Mars on April 4th and 5th, as it heads up above the other two. So they'll be dancing, they'll be snuggling. Well, it's going to be nice. Don't miss it, man.

Mat Kaplan: I won't. Or I might. I forgot to mention something that I was going to say at the top of the show. It's to say aloha to Don Allen, our listener in Hawaii, who says he enjoys our podcasts and our jokes make his dad jokes seem okay.

Bruce Betts: Thanks. Yeah, we can go with thank you. We will just go with thank you.

Bruce Betts: All right, let us go on to this weekend space history. Aloha. Mariner 10, it happened 1974, its first flyby of Mercury giving us our first-ever close-up view of the mercurial planet of Mercury. And going a little farther back, 1655, Christiaan Huygens discovered Titan, the large moon of Saturn this week.

Mat Kaplan: So here's another non sequitur, which I thought of because of aloha and tropical islands. Do you ever see the episode of Gilligan's Island where a probe lands on the island? I may have mentioned this before. A probe lands on the island and the scientists at, I assume, JPL think it's on Mars. Castaways are trying to figure out what to do. And they end up getting tarred and feathered. And so the scientists all think these are weird feather Mars creatures until Gilligan trips over and falls over and breaks it. Very sad actually.

Bruce Betts: Spoiler alert. All those that I watch ... I love that show but, boy, they are sad.

Mat Kaplan: As the alien said in the classic movie, Galaxy Quest, those poor people. Please go on.

Bruce Betts: Random Space Fact.

Mat Kaplan: Gee, Skipper.

Bruce Betts: Venus, you probably think of, but I think of it as having no magnetic field because it has no internally driven magnetic field, possibly due to less convection and other stuff going on inside the planet than the Earth. But it has a weak global field that is induced by interactions of the solar wind with the very upper atmosphere of Venus. So it has this induced weak magnetosphere.

Mat Kaplan: That is so perfect, considering the conversation we just had with Margaret Kivelson, talking about these induced magnetic fields and the things you can discover because of that. So thank you.

Bruce Betts: Wow, I knew that she was your guest, which is why I went magnetic fields, but I had no idea of what you were talking about.

Mat Kaplan: Serendipitous.

Bruce Betts: Speaking of serendipity and [inaudible 00:47:16] nonsequiturs, we're going to go on to the trivia contest. I asked you approximately what is the ratio of the surface escape velocity on Mars compared to Earth. And what is that answer, approximately there?

Mat Kaplan: Well, let me let, as we often do, our Poet Laureate, Dave Fairchild in Kansas provide what he believes is the answer. Escape velocity is used to roughly get a grip how fast you need to move ahead to break a planet's grip. Kilometers per second is the way we ought to go. And Mars compared to Earth is 0.45 in ratio.

Bruce Betts: Wow, that was some impressive rhyming. I mean, wow. Yes, that is correct. You have to go about half as fast leaving Mars as you do leaving Earth.

Mat Kaplan: Well, thanks again, Dave. And congratulations, Frank Buckingham. Actually, Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, Frank Buckingham, in Illinois. Frank, you're our winner, a first-timer, from everything I could tell who said, yep, that ratio is 0.45. So Frank, we're going to send you that Better Know an Asteroid t-shirt from Chop Shop, chopshopstore.com, I'll say it again, where all of The Planetary Society merch is. We have our own story there.

Mat Kaplan: This is that great t-shirt that has a little tiny image of OSIRIS REx approaching asteroid Bennu. And man, do they have great design. So congratulations, Frank.

Mat Kaplan: Harry Rao in Texas, regular contributor, is as coincidentally, this is very close to the ratio of escape velocity from moon to escape velocity from Mars, which he lists as 0.480. Does that sound about right?

Bruce Betts: Sure. I mean, it certainly makes sense the very ballpark that would be similar but I don't have enough of a gut feel nor have I done the calculation. But I'm going to believe our trusted listener and go wow, that is a random space fact worthy of being on Planetary Radio. Oh, wait, it just was. Yay.

Mat Kaplan: So Harry, there's the scientific consensus for you. Here's a poem from Ian Lewin in Washington.

Bruce Betts: I am the scientific consensus.

Mat Kaplan: Consensus of one. Gravitational influence must be overcome. And there is also a need for speed. Celestial mechanics are here then employed to determine just how much we need comparing the numbers between Mars and Earth, the ratio is around five/11. So Mars being smaller is easier to escape. Oh, John Carter used astral projection. I think I got the meter wrong about that, but you get the idea.

Bruce Betts: Ah, you and meter.

Mat Kaplan: There's just one more. It's from Krux Orban, Colorado. He says, "Love the show. This answer almost escaped me."

Bruce Betts: Do we get to find out the prize yet or did you actually want me to provide a question?

Mat Kaplan: No prize revealed until you give us the question because after all, if it's like a lousy question, maybe I won't award a prize. How do you like that?

Bruce Betts: So if I do something wrong, everyone suffers.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, everyone is punished. That's right.

Bruce Betts: I never liked that strategy. Well, hopefully, you won't hate the question. Here it is. It's nice and short so we can get right to the prize. What was the first European Space Agency mission to use ion propulsion? Go to planetary.org/galaxyquest. No, planetary.org/radiocontest.

Mat Kaplan: Never surrender. You have until the 30th. That'd be March 30th at 8:00 a.m. Pacific Time. And that fourth prize from Chop Shop, it is a Your Place in Space t-shirt, chopshopstore.com. Take a look at it and you'll see how cool it is. Basically says Your Place in Space. And it's got this great hand pointing upward toward the sky.

Bruce Betts: Worth it.

Mat Kaplan: We're done.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody, go up there. Look up in the night sky and think about the first magnet you can ever remember. Thank you and good night.

Mat Kaplan: You know something, I might still have it. I'm telling the truth. It is this little bag in a container I have. And it has a variety of magnets and iron filings I picked up on Torrance Beach here in California. And I don't know how old I was.

Bruce Betts: Wow, cool. I can remember buying these old disc magnets of RadioShack and playing with them.

Mat Kaplan: I was there with you. I have some of those in there as well. We'll have to share our magnet collections sometimes.

Bruce Betts: Oh, that sounds fun. I mean, oh, okay, maybe we can do some professional experiments, Mat. You should probably sign off now.

Mat Kaplan: He's right, of course, because he's the chief scientist of The Planetary Society, Bruce Betts, who joins us every week here with his magnetic personality. And what's a Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California and is made possible by its legendary members. You can become part of their legacy when you visit planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta, our associate producers, Josh Doyle who composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. Ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth