Planetary Radio • Jul 07, 2021

Visiting the James Webb Space Telescope

On This Episode

Bill Ochs

James Webb Space Telescope Project Manager, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Gregory Robinson

James Webb Space Telescope program director, NASA Science Mission Directorate

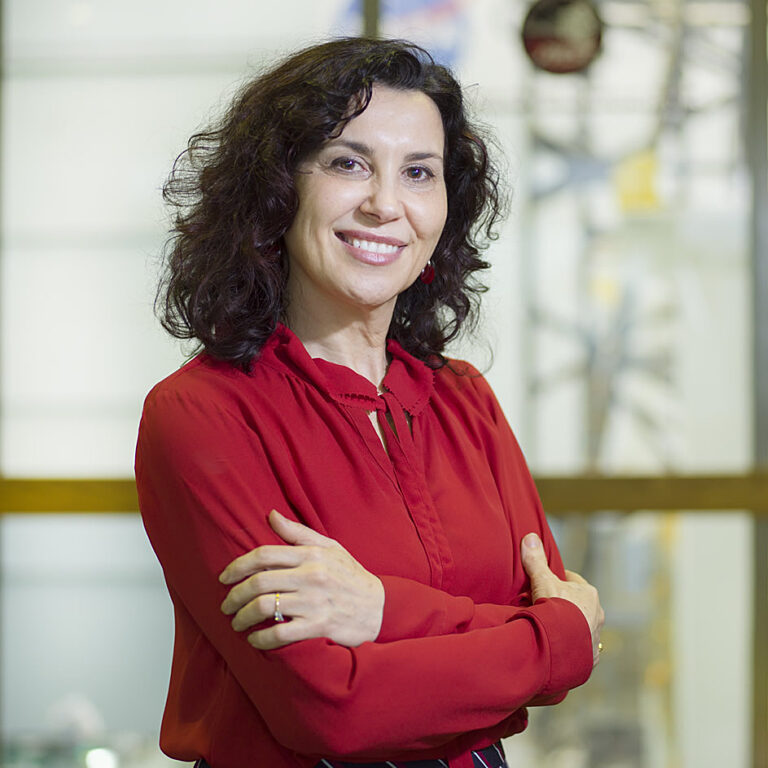

Begoña Vila

James Webb Space Telescope Instrument Systems Engineer, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope is expected to be 100 times as powerful as its predecessor, the Hubble Space Telescope. We talk with three leaders of the effort to build, launch and deploy it as soon as November of this year. These conversations were recorded on the other side of a window facing the Northrop Grumman clean room in which technicians were putting the finishing touches on the observatory. Bruce Betts salutes Webb with a special What’s Up Random Space Fact.

JWST Deployment Sequence Before JWST can do its job, it must first get to space and execute one of the most complex deployment sequences ever attempted. Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

Related Links

- James Webb Space Telescope, the world's next great observatory

- December 16, 2014 Planetary Radio: Sara Seager and the Search for Earth’s Twin (Recorded during a tour of the James Webb Space Telescope)

- James Webb Space Telescope Project Manager Bill Ochs

- James Webb Space Telescope Instrument Systems Engineer Dr. Begoña Vila

- James Webb Space Telescope Program Director in NASA’s Science Mission Directorate Gregory Robinson

- The Downlink

Trivia Contest

This week's prize:

This week's question:

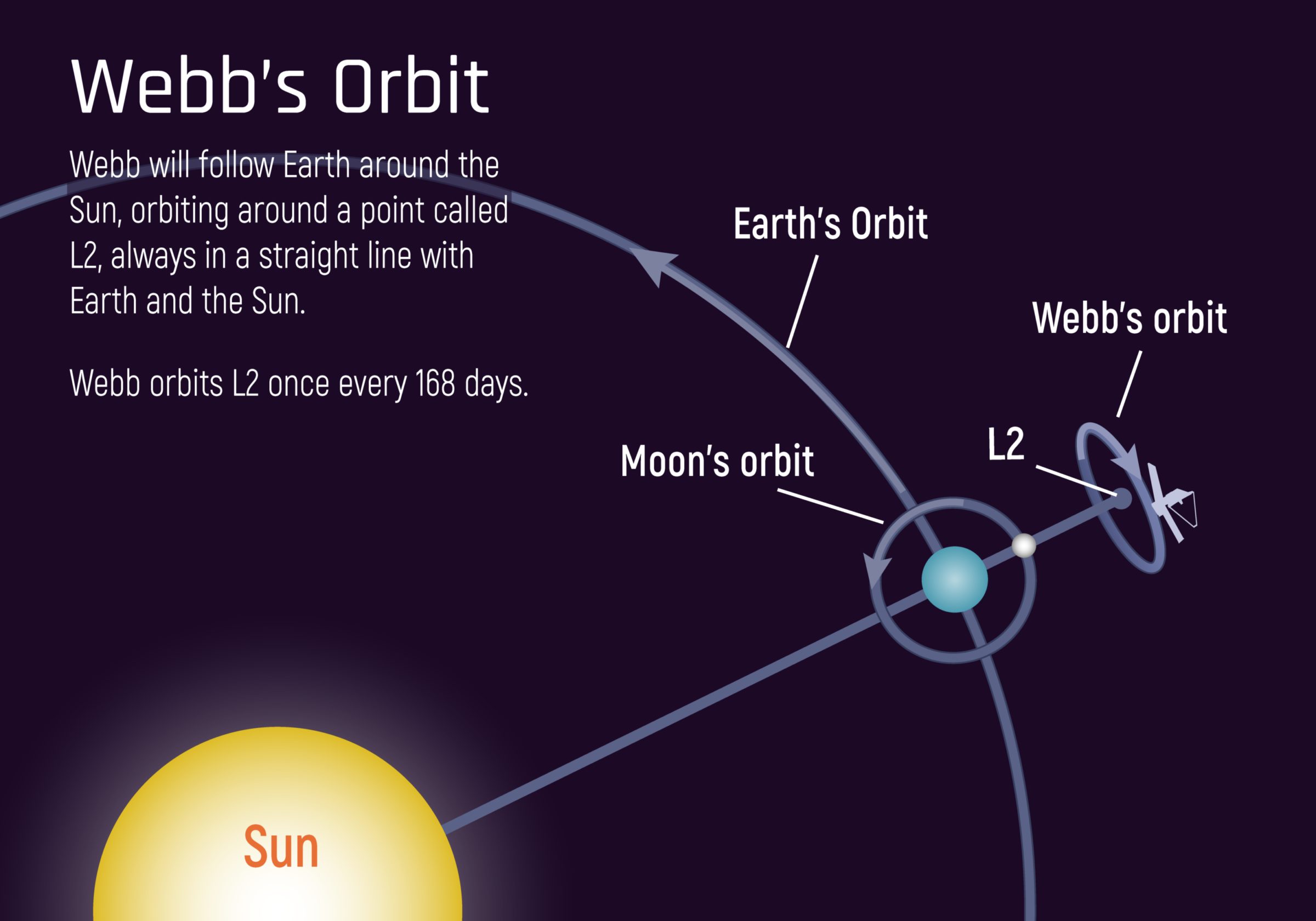

What was the first spacecraft stationed at Earth-Sun Lagrangian Point 2 (L2)?

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, July 14 at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

Who was the first married couple to fly in space together?

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the June 23, 2021 space trivia contest:

What is the only one of the 88 official IAU constellations that is named for an actual person?

Answer:

The only one of the 88 official IAU constellations that is named for an actual person is Coma Berenices, which means the hair of Berenice. Queen Berenice II of Egypt lived in the 3rd century BCE.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: Visiting the James Webb Space Telescope this week on Planetary Radio. Welcome. I'm Mat Kaplan of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond.

Mat Kaplan: Have you been to The Grand Canyon? Did the pictures you'd seen of it come close to viewing the real thing? No, they didn't. Did they? That's how it is with the James Webb Space Telescope. It's what I discovered a few days ago when I visited The Webb. You'll hear my conversations with three leaders of the effort to build the space observatory that will be 100 times as powerful as the Hubble.

Mat Kaplan: Bruce Betts will put the icing on this cake of science with a JWST random space fact that will have you buzzing. First up are these headlines from the July 2nd edition of The Downlink, our weekly newsletter, which is topped by the image that used to be on the back of my business card.

Mat Kaplan: It's our own pale blue dot seen by the Cassini orbiter and a picture that includes the rings of Saturn. Words cannot express its beauty or its profound impact. Our own Andrew Jones has shared video of China's Zhurong Rover descending to the marsian surface. You'll find it among these headlines at planetary.org/downlink.

Mat Kaplan: NASA's NEOWise has been given a two year mission extension by NASA. The new earth object hunting spacecraft has already observed nearly 2000 asteroids. We'll be talking with NEOWise and NEO Surveyor principal investigator, Amy Mainzer, in a couple of weeks.

Mat Kaplan: Aviation legend, Wally funk, will finally make it into space nearly 60 years after NASA said no to her and 12 other women. She will ride with Jeff Bezos aboard his New Shepard suborbital capsule on July 20th. Godspeed, Wally.

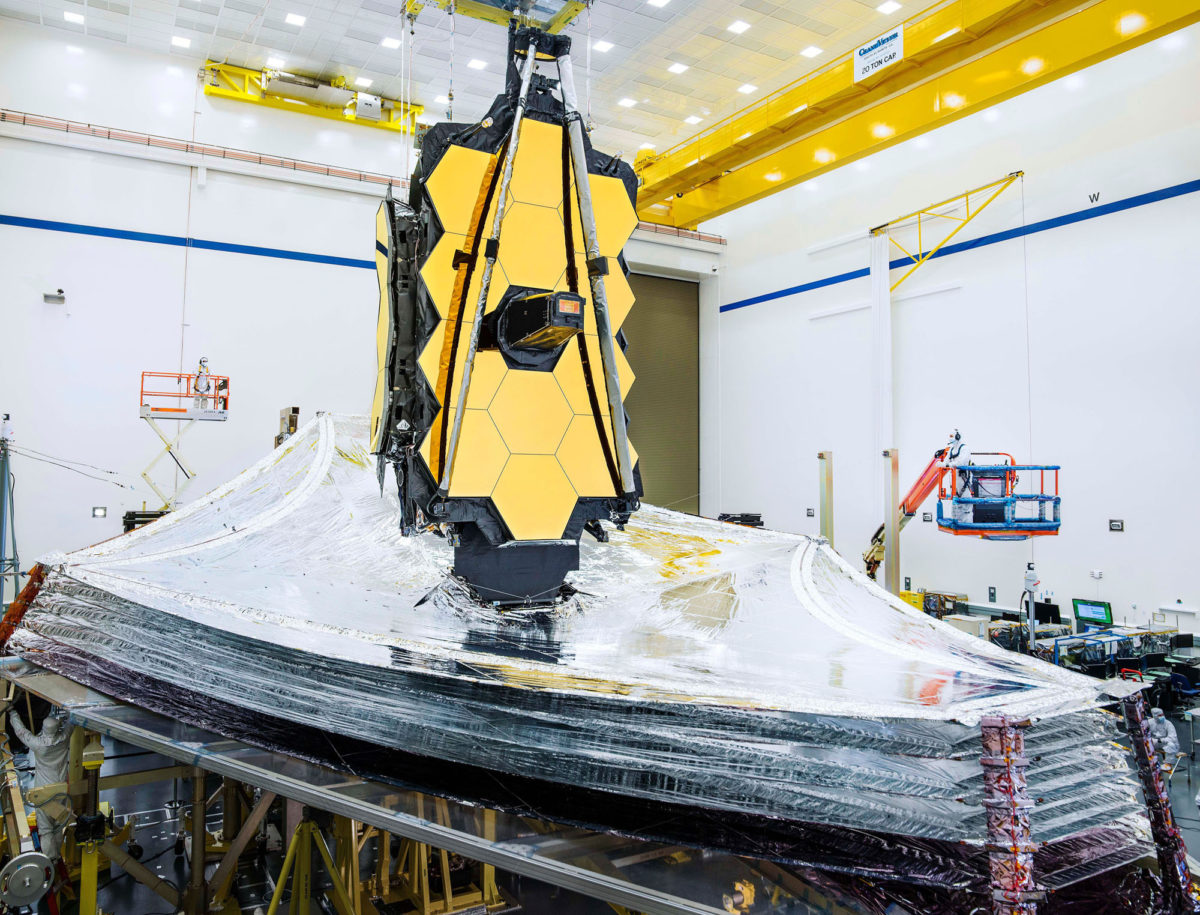

Mat Kaplan: I grew up not far from what used to be the headquarters of TRW here in Southern California. The sprawling campus is now a Northrop Grumman facility. One of the buildings hides a towering clean room. Inside that room, surrounded by Northrop and NASA technicians and dwarfs, is one of the most wonderful machines ever created.

Mat Kaplan: After years of development, construction and testing and after billions in cost overruns, a magnificent space observatory is nearly ready for a trip to French Guiana. That's where it will leap into space to top an Ariane 5 rocket headed for Sun-Earth Lagrangian point 2 often simply called L2.

Mat Kaplan: If all goes well, it will spend many years at that spot of balanced gravity that is one and a half million kilometers from earth. Scientists around the world trust that it will revolutionize our view of the universe and the way the Hubble space telescope started to do more than 31 years ago.

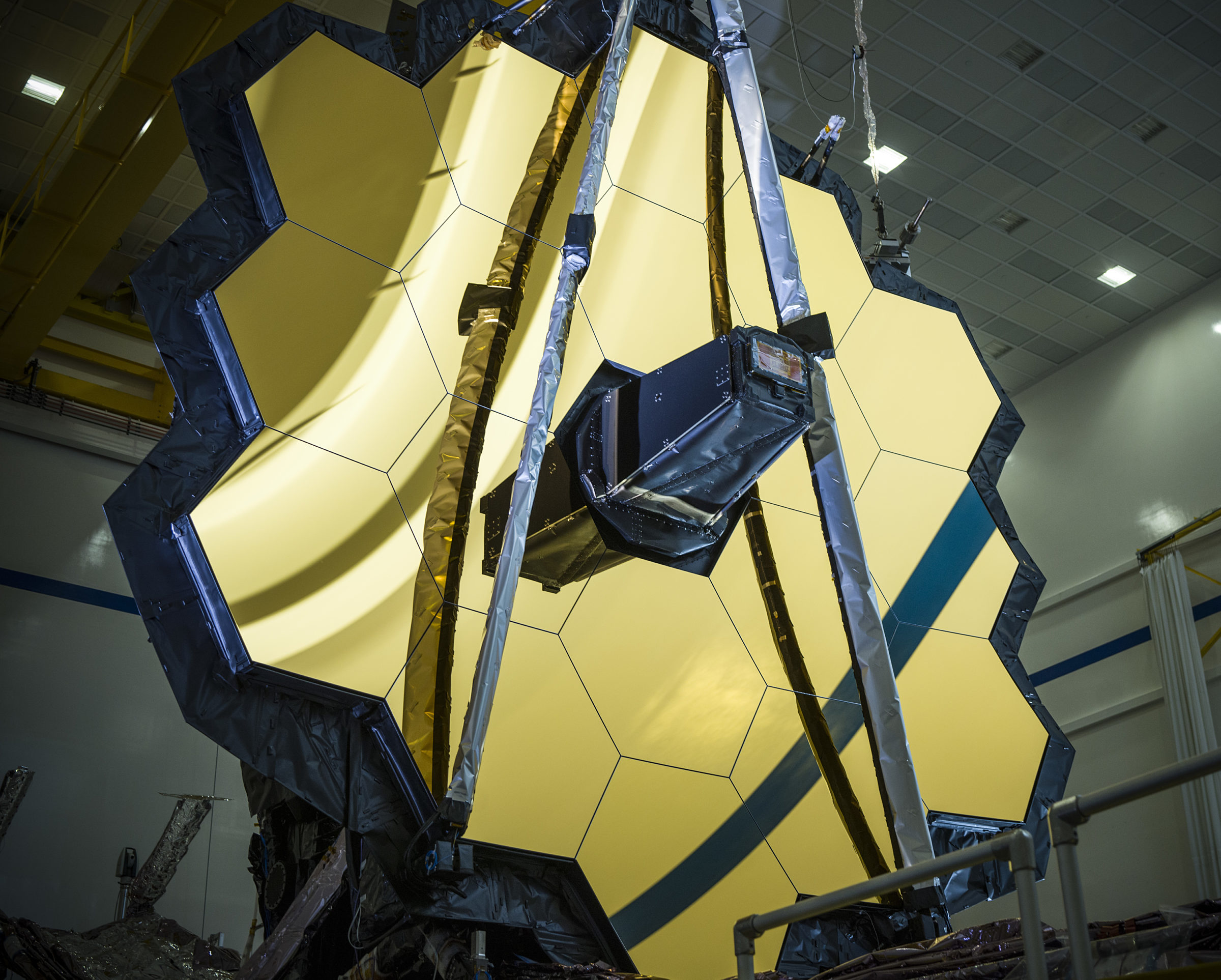

Mat Kaplan: Looking down on the clean room from an enclosed gallery near its ceiling, I see the bunny suited techs swarm around the giant spacecraft. I above them and nearly at my eye-level are 18 stunningly beautiful hexagonal mirrors each coated with gold.

Mat Kaplan: In front of these and leaning outward is the folded sunscreen that will enable the Webb to examine at infrared wavelengths, everything from planet circling nearby stars, to our universe in its infancy. Custom rigs and frames support the telescope, techs lying on their stomachs are inserted by forklifts deep into the guts of a great instrument.

Mat Kaplan: The narrow platforms they lie on look like what they're called, diving boards. With enthusiastic NASA and Northrop Grumman minders looking on, I welcome Bill Ochs. His service is the JWST Project Manager at NASA's Goddard space flight center is likely to be the climax of a decades' long aerospace career.

Mat Kaplan: We sit down on bar stools where we have a deeply distracting view of his observatory in front of us. Bill Ochs, welcome to Planetary Radio. I have seen you talking about this marvelous instrument that is right behind the glass outside our little viewing balcony here for so many years, but it is an enormous pleasure to actually welcome you to Planetary Radio.

Bill Ochs: Thank you. Thank you. Appreciate it. Yeah, it's quite amazing sitting here looking at the telescope now. I started on the project 10 and a half years ago when we were still just getting the pieces in. So, it's pretty exciting.

Mat Kaplan: That's when you became the project manager, right?

Bill Ochs: Yep. In December of 2010.

Mat Kaplan: You have seen so much happen with this spacecraft, because it is a spacecraft as well as being a telescope, of course.

Bill Ochs: Right. Yeah. We really refer to it as an observatory where the spacecraft is the bottom part of spacecraft element and the top part being the telescope in the instruments. It's been pretty amazing over the last, like I said, 10 and a half years just to watch it all start coming together, overcome the challenges and problems that we've had along the way to get to this point where we have about seven weeks of touch labor here left at Northrop Grumman.

Bill Ochs: At that point NASA will actually take ownership of it and we do a little bit more risk reduction work here for the launch site. And then we put it into the shipping container.

Mat Kaplan: Man, I know that there has been talk lately, no fault of the Webb, but that the launch may be delayed somewhat. Still looking at the end of this year?

Bill Ochs: Right now it's still looking like end of November. I think that came up at the press conference a few weeks ago with the European Space Agency with some of the issues that the rocket had. The return of the flight is still on for July 27th. There's two flights before us. So there's one July 27th, there's 60 days in between launches. So then you have another one at the end of September and then we're Thanksgiving weekend.

Mat Kaplan: It must be something of a relief to know that the Ariane Rocket, that this will be packed away into the payload, fair enough. It's a pretty reliable launcher.

Bill Ochs: Yeah, it's one of the most reliable launches out there. I mean, they had some issues last year with the fairing and they're working through those and they're very, very transparent to NASA as well as ISA. We have our friends from Kennedy Space Center working with them also and working with us. So, we're really working as one team, so we understand what the problem was and how they're correcting it. So we have confidence that when we launch on the third flight after the return to flight, that we have a hundred percent confidence that we'll be fine.

Mat Kaplan: That has to happen after that. And we'll get to that, but I want to go to your own experience in doing this kind of stuff, not your first ride around the block. Among the projects that you've worked on for NASA and elsewhere before that, the Hubble Space Telescope, which I will note as we speak is experiencing some, not unexpected troubles.

Mat Kaplan: I mean, that wonderful instrument has lasted so long and done such a great job. And of course, we hope that they are able to fix that computer problem they've got, but does it add a little bit more, any sense of urgency to you that at some point the Hubble is going to reach an end?

Bill Ochs: Well, I think at this point the urgency... We launch at the end of this year. We're not going to launch before that. One of the things I stress to our folks is, don't get too excited. We need to focus on the task each day that we have in front of us to complete that task in the safest, most successful way to get to the point where we launch.

Bill Ochs: And you don't want to rush through anything at this point because a mistake can then cost you even more time. So, it's important just to stay focused on the task at hand and then we'll get to launch it in November.

Mat Kaplan: You did spend, as I said, quite a bit of time working on the Hubble and its development and then went off and did other things. I just wonder how all of that experience has benefited you as the project manager for a tremendous project. One that integrates components that has an international involvement. I mean, just looking out at it, and I only wish that the listeners had this view, I get a better sense than I ever have before of just how complex a machine this is.

Bill Ochs: Yeah. I think, going back to the first part of your question, how things benefit me through my career. I mean, I spent almost 20 years on Hubble, not quite 20 years starting when it was still in manufacturing and testing. I worked for a contractor that's no longer around, Bendix Guidance Systems Division that was subcontracted to Lockheed Martin.

Bill Ochs: We developed a lot of the various added to control to components. I particularly worked on essentially the backup flight computer. Not the flight computer I'm having problems with now, that's the payload computer, but the actual flight computer that controls the observatory, they had a problem and it shut down. The one I worked on would take over.

Bill Ochs: And then I went down to Goddard, worked operations before we launched and then became a NASA employee in 1990. And then I ran the operations out of Goddard for the first two Hubble servicing missions before leaving Hubble and then went on to do project management.

Bill Ochs: So, all those experiences, like the experiences on the Huddle, it was a very large mission. JWST is very large mission. The challenges were very different because of the technologies and what we're trying to do, but the way you work together as a team, which is always a good, that's one of the big lessons you bring, that stays. It doesn't matter what the challenge is. You want that working together as a team.

Bill Ochs: When you have missions like JWST, like Hubble, one contractor can't go off and do it, NASA just can't go off and do it. It takes, in the case of JWST, a very large team of contractors and NASA and in the U.S, our partners in Canada, and our partners over in Europe to really pull this all together. One of us couldn't have done it by ourselves.

Bill Ochs: So, I think that's always a good sense that comes out of it. And then there's other lessons. And then when I left Hubble, I became a project manager and started with a very small mission. So, a very big contrast with a mission called the Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment working with the University of Colorado.

Bill Ochs: We launched that, then I moved on to what's now known as Landsat 8, which was at that point Landsat Data Continuity Mission. And was there for eight years until someone came knocking on my door saying, "Hey, we got another job for you."

Mat Kaplan: Somebody-

Bill Ochs: Which was a mistake.

Mat Kaplan: They obviously had a lot of confidence in what you were capable of doing to move into a project like this. A lot of what you're talking about, and I assume a lot of your job is a topic that comes up now and then on our show, but not often enough. And that is the importance of systems engineering. Is that one of the biggest challenges that you face because you've got so many moving parts?

Bill Ochs: Yes. System engineering has always been a big part of JVST. You look at it now. If we were to fully deploy JWST, it doesn't fit in any test chamber that's any place around. So, one of the big challenges, and this is a systems engineering challenge is, how do you test this telescope?

Bill Ochs: You can test it in two pieces, and that's what we've done. So, if you take the telescope and the science instrument that's integrated, and that component, we call it OTIS. It's a acronym of acronyms. It is a telescope and the four science from it's integrated together. We were able to take that, that was all integrated together at Goddard space flight center. We put it through its environmental testing that it will see inside the rocket, which is always the most violent it will see at Goddard.

Bill Ochs: So, vibration testing and acoustic testing. We'll just let the sound levels, you'll see inside the rocket. We did not have a chamber big enough at Goddard to actually do the cryogenic testing. So back, even before I came on the program, they made a deal with Johnson Space Center to take a chamber that was developed for the Apollo era, refurb it into the world's largest cryogenic chamber.

Bill Ochs: And that's where we're able to take the telescope instruments down there, deploy the mirrors and run through a battery of testing at cryogenic temperatures to prove that it works, to prove that we can focus the telescope, to prove that the instruments work at that range integrated into the telescope. That was a really big test. And right in the middle of it was Hurricane Harvey. So it became even more challenging because we basically kept the OTIS safe over a span of two or three days when it was really bad.

Bill Ochs: And we kept the people who were at Johnson there, we had cots brought in and stuff, and the folks who were in their hotels, you stay in your hotel. And once it passed and you were able to get out again, we were able to start the testing again. The thing there that I'm most proud of all the time, I tell folks, besides the fact that the test was a big success, was that the folks, when they rested up, they went back out into the community and volunteered in the community to help the community to recover from the program, which I just thought was outstanding.

Bill Ochs: But that's how we tested the OTIS. And then the OTIS came out here. Now you have the bottom piece, the lower part, we call the spacecraft element. That is the spacecraft bus, so it has all the electronics, the Solar Array, communications equipment and the sunshield that could go through testing here.

Bill Ochs: So, it went through its environment, same type of environmental testing vibe acoustics, and then into a thermal vac chamber to run its testing. But once you put those two pieces together, you can't test this in a chamber anymore. So, the way you overcome that, this project is very intensive in mathematical modeling.

Bill Ochs: So, starting that at a very low levels of components, we build mathematical models. Results of those models compared to the results of the testing. You get them to match and make your adjustments to the models. And now you start building up and you build your models up to the point that in the end you've got, there's about a dozen models we can use that can accurately predict the performance of JWST on orbit without having to go through a fully integrated telescope or observatory, environmental testing. Electrically, we could test. We tested the entire telescope electrically, but it was really the environmental testing.

Mat Kaplan: And we're going to talk a little bit later with your colleague Begoña Vila, who has been involved with a lot of that testing I'm told. You mentioned a hurricane, that may seem minor compared to what we hopefully are coming out of now, a pandemic. How did that affect the project?

Bill Ochs: That was very challenging. From my standpoint, my counterpart at Northrop Grumman, Scott Willoughby's standpoint, the most important resource on this program are the people. And you can say it's time, and you can say it's money, but none of those do any good if you don't have the people to do the job.

Bill Ochs: So, when the pandemic really started and things started shutting down in March of 2020, we see California shut down, I think on a Wednesday. So we suspended operations, told everybody to go home. We had to figure out what we were going to do. We wanted folks to go home and figure out how you're going to cope with this. We had about 30 to 40 folks from Goddard Space Flight Center out here. We got them home. A few of them volunteered to stay.

Bill Ochs: And through the weekend, what we decided to do at that point, we were running two 10 hour shifts a day, six days a week. We made a decision to cut that back to one 10 hour shift a day, five days a week. So we slowed things down to allow folks to really be able to cope with the issues they deal with at home.

Bill Ochs: We had to develop protocols to bring the folks back in here to work. I mean, when you're in the clean room like you have folks in there now, you're pretty safe. You're pretty low risk as far as ever.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. We're looking at people, mast, bunny suits and very clean air.

Bill Ochs: Yes. Yeah. But getting in there, they have to go through a gowning room and such. So we started limiting the number of people in the gowning room, going through the air showers one person at a time versus that, that also slowed the process down. Luckily, we're in Southern California so if people lined up to getting outside, most times it wasn't raining.

Bill Ochs: If it was raining, they could stay in their cars and then come in. So, it increased the amount of time they get in and the time to take breaks and go out. Because once you go in, you don't stay in there 10 hours. You can take breaks, you have lunch breaks, whatever. So that has slowed down the process. And we kept those protocols in place through the end of last year. And for the most part, they're still in place now. There are still some of those protocols in place.

Bill Ochs: That was really probably the biggest impact here at Northrop Grumman. The other big facility we have is the Space Telescope Science Institute, the campus at John Hopkins. They basically closed down and everybody worked from home. Last summer, we began to bring back not so much the folks that work there, except the ones that support operations, but letting our flight ops, some more folks back in, their flight ops team back in because we needed to start testing with the spacecraft from the control center last summer.

Bill Ochs: And that's going well. We have gotten better and better with the protocols there. As things have gotten better, the protocols get a little less to the point where now we're running a full-up mission rehearsals up there. We just completed an eight day one where we broke it up into the first day was a countdown from L minus six hours up through Solar Array deployment.

Mat Kaplan: Wow.

Bill Ochs: We did three days of sun shield deployments. And during these times, as much as we want them to run smooth, the team running their mission rehearsal throws anomalies at us, and you have to be able to respond to those anomalies and exercise, what I always call our toolbox, maybe think outside that toolbox and how you resolve some of these if we have an issue on orbit.

Bill Ochs: And then we spent a day, I think, deploying mirrors and then doing our wafer and sensing, which is focusing the mirror as well as doing some instrument commissioning exercises. And we have another one of those coming up in August. That's a full two weeks.

Mat Kaplan: To paraphrase the person who said, how do you get to Carnegie Hall? I guess I would say, how do you get to a Lagrange Point? Practice, practice, practice.

Bill Ochs: Practice, practice. Yes. Test, test, test. Rehearse, rehearse, rehearse.

Mat Kaplan: Any idea how big the team has been, how many people have contributed to this project? I mean, we're seeing some of them down there on the floor right now, largely Northrop Grumman technicians, of course, but not just the number of people, but the variety of skills that have gone into creating this observatory.

Bill Ochs: Well, a couple of things. One, when you actually look on the floor, that is an integrated Northrop Grumman NASA team that's out there. We are a fully integrated IMT team. So you almost always see a mix up. You may not know it, but there's always a mixture out there.

Bill Ochs: Over the years, and if you go back 20 years to develop this mission, we have taken a very rough guess at over 10,000 people have worked on. It's not all engineers and it's not all scientists. Right? We have our technicians, we have the machinists. You've got other support folks, such as contracts folks, lawyers. They're all part of that team that all worked together. So there's all different skill levels and talents that go into to constructing something like this.

Bill Ochs: When I go out to schools, I like talking to elementary school kids. So, at some point when we get back normal and you can do that again, I always tell them, "If you're really interested in space..." We tell everybody, right? Math, science, I emphasize English because you better be able to communicate your ideas to folks.

Bill Ochs: But that's not the only thing you can do if you can't get, not everybody's a mathematician, but there's lots of other things you can do. Everything from a machinist, to a graphic artist, to financial people and business folks, you have... I'm going to get people mad at me if I leave them.

Mat Kaplan: It's like the Academy Awards. Don't leave anybody out.

Bill Ochs: It's almost any kind of job you can think of, you can probably tailor it to be working in the aerospace industry and working on a satellite.

Mat Kaplan: I got one for you, which was absolutely delightful when I made that earlier visit here to Northrop Grumman. At that time, there were seamstresses sewing the sunshield.

Bill Ochs: Yep. We don't use that term, but it is like that. Anytime you want or need, whether it's the sunshield itself was manufactured by a company called NextSolve in Huntsville, Alabama. When you look at the sunshield and it's deployed, it's about the size of, we would say the size of a tennis court.

Bill Ochs: Each layer is made up of 50 individual pieces and they are thermally stitched together. But going back to what you mentioned about people just sewing things together, there's a lot of thermal blanketing on this satellite, almost on any satellite, but especially on this satellite.

Bill Ochs: And that is done in a shop where you literally are using sewing machines and such to stitch things together and piece of that and cut things out the patterns, and that all goes into installing all of our thermal insulation and it's all different shapes and sizes. Yeah, it's just another example of the type of career you can have that still gets you involved with aerospace.

Mat Kaplan: It has been, as we said, a long, hard road, some bumps along the way, so close now, and this is a question I'll probably ask your colleagues who will be coming in as well. What step in the deployment of this telescope is going to give you the greatest amount of relief once it's complete? Once it's in place.

Bill Ochs: Lots of times I just tell folks, have you seen the video? That should give you enough nightmares right there. But probably the most complex deployment is the sunshield. It's got, let's see if I get these numbers, 1300 feet of cable, has 107 different release devices. It's either 4 or 500 pulley assemblies, it is extraordinarily complex. And just watching when they deploy it here in the clean room, you can get that sense because also you have all these other ground support equipment to do 0G offloading because we designed it to operate in a 0G environment, not in a 1G environment. So you need to take that into account.

Mat Kaplan: Sure.

Bill Ochs: So, it is a very complex deployment. That's probably the one you worry about the most, but we tell folks, and I think it was one of the Mars Landers had the seven and a half minutes terror.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, I was going to bring that up.

Bill Ochs: We call it, our equivalent is two and a half weeks of high anxiety.

Mat Kaplan: You beat me to that comparison. Once it's up there, once you've seen first light and those hundreds and hundreds of scientists, many of whom I've had on this show talking about how much they're looking forward to this telescope beginning to do its work, can you make a comparison, and it's the sort of thing anybody can find easily on the Webb, of just how big a jump this is going to be over the Hubble space telescope, or for that matter any other telescope that we've put up there in space like the Spitzer?

Bill Ochs: We'll do the comparison with the Hubble, because that's the one everybody likes to do the comparison to. So, our primary mirror is about seven times the size of Hubble's primary mirror. So, right away you see a huge increase in collecting power. We also have detectors that are more sensitive. When you combine those things together, the number I hear from our science folks, because I'm not a scientist, is that we're probably going to be about a hundred times better than whole.

Bill Ochs: Now you combine that with the fact that we are an infrared telescope. That's like one of the really big differences is why you see the mirror coated in gold, because gold is more sensitive to infrared.

Mat Kaplan: With beryllium behind there.

Bill Ochs: With beryllium behind it, yeah.

Mat Kaplan: We could have done this whole conversation just talking about those mirrors.

Bill Ochs: Right. Right. Yeah. I mean, that was in one of our big technology developments. You combine all those things together and you look at what some of the science goals that we have. Whether it's going back and looking at the very beginnings of the universe and how the first galaxies and stars were formed. The one I get a big kick out of is looking at exoplanets. As a kid, I got a telescope, I maybe in the sixth grade.

Mat Kaplan: Me too.

Bill Ochs: And the first thing you look at is the moon. The next thing you start looking at is trying to look at Jupiter and Saturn and that kind of stuff. And I've always been fascinated by that. So now, with our spectrographs and the sensitivity that we have, we'll be able to look at some of these exoplanets and look if they have the basic elements for life. And I always put the caveat as we know it.

Mat Kaplan: Yes. Right.

Bill Ochs: We think we may know everything, but time and time again, we're proven wrong. All through history.

Mat Kaplan: Just last week on this show, we were talking to somebody about exactly this topic and how even remote telescopes like this may be able to help as we figure out ways to recognize even life as we don't know it.

Bill Ochs: Yes. Yeah. Yeah. I mean, I think it's going to be really cool. And that's what I'm really looking forward to as I'm sitting on a beach having a drink after all this.

Mat Kaplan: You obviously have to interact with, I mean, you've got a whole bunch of scientists who are project scientists on this project, but all those others around the world who you must be hearing from. And I just wonder about, if you thought about how it's going to feel to know the kind of science that you've enabled them to do once Webb is doing what it will.

Bill Ochs: From my personal standpoint, from my career, because after this, I'm going to probably retire. I started on Hubble 21 years old by a few weeks and I finishing my career managing JWST is just mind blowing. It's like I came full circle. And so, I get a tremendous amount of satisfaction out of that.

Bill Ochs: Looking back in my career after the first servicing mission and we got everything straightened out with the mirror, the type of science that Hubble has done, it's been amazing to look at how now JWST is going to go back and take those same books that Hubble rewrote with its science, we're going to be rewriting again. It's just amazing. It's very gratifying.

Mat Kaplan: There are people right now, I've talked to some of them, who are beginning to design and even propose the telescopes that will someday, could be 20 years from now, be the follow-on to this just as it is the follow-on to the Hubble. What's your advice to those people?

Bill Ochs: Be conservative when you're starting to try to figure out how much it costs and how long it's going to take the build. It's important not to be optimistic, or I like to consider myself I'm an optimistic-realist. And even then, there's the unknown unknowns that can happen and burn you along the way. I try to apply if a telescope has some of the technologies we have, for example, the segmented mirrors, try to apply lessons learned from JWST to that.

Bill Ochs: There's other things that they'll have different technologies that you just can't apply the lessons learned to it. Just like we couldn't apply lessons learned from Hubble to JWST. But it really is try making sure you think everything through. And it's very challenging. People come to me all the time and they talk about, "Well, it was originally a billion dollars and now it's $9 billion."

Bill Ochs: What you have to do is come out here and take a look at it, or look at pictures of it, then understand that it's, like I mentioned before, 10,000 people have worked on this over the years. You can't do the math to make a billion dollars work. The complexities of it, we developed 10 new technologies for this telescope. That takes time, effort, and money. So, you got to have the reserves in there to be able to do that because it may not go smooth the first time.

Bill Ochs: Typically, it's an iterative process, right? We're making progress, but it's not quite there yet to meet requirements. Got to do it again. That all takes time. The mirrors are a prime example of technology development what it took to go from a chunk of a beryllium to this mirror you see now is amazing.

Bill Ochs: The number of people that were involved in that. The analogy we like to use, if you took a one segment of the mirror, and a segment is about the size of a good sized coffee table. If you took that segment and before you polished it and then blew it up to the size of the continental U.S and had your imperfections as the Rocky Mountains, when we finished the polishing of that, the Rocky Mountains are about an inch high.

Bill Ochs: So, it shows you the level of the type of work we had to do. When they did their initial polishing, they then went down to, I think it was at maybe five segments at a time or four at a time, whatever, down to Marshall Space Flight Center. We went into a cryogenic chamber there. You bring them down the cryo chambers temperatures.

Bill Ochs: And when you do that, you're going to get imperfections in the mirror. You have to measure those imperfections. And let's say one of the infections turns into a peak. You take it back to the polishing factory. You take that peak you now make it a valley.

Mat Kaplan: The peak that's no longer there once you take it out of the cryo chamber.

Bill Ochs: Now you make a valley. Now when you go back into the chamber the second time around to test it, that peak is now flat, right? Because you compensated for that. And the same thing with the valleys that you may have seen. So that's an iterative process we had to go through and get developed. And it was very neat technology to go do that.

Bill Ochs: It sounds simple, but it really took a lot of effort and a lot of people a long time to figure out how we get these perfect mirrors. On the back of each mirror are six actuators. So we can make adjustments for focusing when we get on orbit. Because when we get on orbit, you basically start it with 18 images that you want to get down and focus it to one image.

Bill Ochs: But we can make all sorts of adjustments on this, even in orbit. You can move the mirrors up and down, back and forth, in and out. You can even change the shape a little bit. So, that allows us a tremendous amount of flexibility over time to make adjustments to that mirror when we need to.

Mat Kaplan: Great example. What's that saying? Do great things?

Bill Ochs: Do great things or keep it simple, stupid.

Mat Kaplan: Also applicable.

Bill Ochs: Yeah. Yeah. Keeping it simple and stupid is a hard one to apply here.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, sure.

Bill Ochs: That's right because there are all these complexities involved. We go out and we do great things, but to do great things, it takes time, energy, a lot of smart people.

Mat Kaplan: And you learn along the way.

Bill Ochs: Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: And some things happen that probably aren't going to pay off for future projects.

Bill Ochs: Yeah. I mean, there's always lessons learned just in the development of it that you can pay off. And there's very simple lessons learned that people all should be doing. There shouldn't even be a lessons learned. And that is something that's this complex. And I tell folks this all the time, you tend to want to focus on the really, really hard things because that's where you know your challenges are.

Bill Ochs: What can happen is you can miss a simple mistake. And so, you got to look across everything. You got to focus on the simple things just as much as you have to focus on the really hard, complex things. And the example I use all the time is when the spacecraft element came out of acoustics, everybody heard about you look on the floor and we found loose nuts and screws.

Bill Ochs: It was very simple. What happened, Northrop did the drawing?, sent it down to the manufacturer. Typically on a drawing, you'll always have a specification that says for a screw going into a lock nut, for that lock nut to engage, you have to have so many threads, basically proud, little lock nut.

Bill Ochs: That spec was inadvertently left off. So the manufacturer was more random that was done. And that was a result. And they started to back out over time. And then we went to the acoustics environment that was like the straw that broke the camel's back. And that cost us a lot of time to go back.

Bill Ochs: So, it's the simple things like that. And after that we went back, we audited thousands and thousands of drawings, all sorts of the checks that we went through to make sure we didn't have that issue any place else on the satellite.

Mat Kaplan: But this is exactly how the process is supposed to work. Because anything this complex, you're going to run into things like that, no matter how carefully you are. But it was caught here instead of discovering it out there.

Bill Ochs: Oh, yeah. Yeah. They always say the reason why you test is to find stuff. And that's what we did. The frustrating thing is, it was something that was simple. And I can understand why all the critics at JWST get frustrated because it was something that should have been caught.

Bill Ochs: And we take lessons learned from that all along the way as we've gone through and we found other things. We do very heavy auditing. Everything from going out and checking bolts to going and looking at drawings, to going back and double-checking test results and so on. We do a lot of auditing to make sure we never have any problems when we get on with it.

Mat Kaplan: I'm thinking of you as this is your crowning achievement and then going into retirement, and hopefully continuing to visit those elementary schools as you said. Yesterday I told my five-year-old grandson that I'm going to be going to see the James Webb Space Telescope. And he said, because he's already a space geek, "Can I come?"

Bill Ochs: Yeah, that's pretty cool. My grandson is not quite two yet, so he doesn't quite grasp it. But yeah, for the little kids, I mean, it's going to be amazing. This is the next generation's telescope. The five-year-old might actually get to work on the one after this, but the kids now that are middle school, high school and college that want to go into astrophysics, this is what they want to work with.

Mat Kaplan: Best of success, Bill, as this amazing telescope observatory is packed up, sent down to French Guiana, and counts down to its launch, to doing perhaps the greatest astronomical work that has ever been done by a telescope. Where will you be for the launch?

Bill Ochs: Launch will be in French Guiana, so I'll be on console down there. I'll get down there two weeks ahead of time because we have some reviews down there that we finish up. The day after launch, I'll then fly back up to Baltimore and head up to the institute for commissioning.

Bill Ochs: It takes us about 30 days to get out to L2. During that three 8 timeframes when we do all our deployments. Once we do that, we start the Wayfront sensing, we have to cool the telescope down, commissioning instruments. It is a jam packed full six months of commissioning, but the end result is going to be spectacular.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, Bill. Can't wait.

Bill Ochs: Yeah. Thank you. Thank you. Yeah, I can't wait either.

Mat Kaplan: Bill Ochs is the James Webb Space Telescope project manager at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. We'll meet Bill's colleague, Dr. Begoña Vila after this break. I hope you'll stay with us.

Mat Kaplan: Hi again, did you catch my big announcement a couple of weeks ago? Even if you didn't, you may have noticed the change. Planetary Radio is now commercial-free. We're very glad to have made this transition, but it does leave a short of the funds those ads used to bring in. You can tell where this is going.

Mat Kaplan: I hope you'll go to planetary.org/join. Becoming a member of The Planetary Society is the best way to support all of our great work. But did you know that you can also provide direct support for Planetary Radio? Go to planetary.org/donate and scroll down to the picture of Cassini project scientist, Linda Spilker and me touching the geysers emerging from a model of Saturn's moon Enceladus.

Mat Kaplan: My colleagues and I will be grateful for your gift in any amount. And we also look forward to welcoming you as a new member of the society Ad Astra. Spanish born Begoña Vila is a key instrument systems engineer for the James Webb Space Telescope.

Mat Kaplan: Like Bill Ochs, she was making another visit to the Webb from the Goddard Space Flight Center when she climbed the steps to the clean room gallery where I had also talked with Bill, Dr. Vila Begoña, thank you very much for joining us here with this absolutely thrilling view in front of us. Now, this is new for me being in the presence, you still, after all these years, feel that excitement?

Begoña Vila: Indeed. Thank you for having me. It's always an exciting moment. I have been with the project for quite a while. I remember delivering the flight instruments. That was exciting. Seeing them put together in the isomer structure, that was an awesome moment. Doing the cryo testing, then seeing the mirrors, each of the individual mirrors are assembled.

Begoña Vila: Seeing that first picture that a lot of us had gathered, so those mirrors open for the first time, super exciting. And then coming here to Northrop, seeing the sunshield, the integration together and now any phase is super exciting. And it's always a wonderful moment when we get to do what we're doing.

Mat Kaplan: This is as thrilling for me as when I've gone to JPL, put on the bunny suit, you stand in front of curiosity, you stand in front of perseverance. There's this bit of anxiousness as well, because until it's up there getting first-line so much still has to go just right. Right? And you've been a big part of making sure that it will go just right.

Begoña Vila: Yes. As you know, it's going to be very far away, four times the distance of the moon. So, we have had to do a lot of testing on the ground to make sure it will deploy and operate as expected. I think we are all feeling the excitement now because we are almost there.

Begoña Vila: I think this week here we are finishing two of the most important electrical tests that we have to do. In fact, today I am here supporting one event where we induce a fault and we show that everything saves and shuts down as it should. But anyway, we are very close to going to the French Guiana doing the testing there.

Begoña Vila: And then doing the launch will be exciting, but that's not the end of it. Of course then we have about six months of commissioning. We have to deploy all the components, align those 18 mirrors. The first time we take a picture of a star or orbit, we'll see 18 stars. Each of the mirrors behaves as a mirror.

Begoña Vila: So, a lot of work with the actuators on the back to make it behave as a single mirror. And then we have to turn each of the instruments, do the calibration. So, I think it's going to be so exciting even after the launch during all that time until we say we are ready here at James Webb go and use it. So very, very cool.

Mat Kaplan: Very much the same process that all big, new telescopes have to go through, the big difference, of course, being this is going to happen in the vacuum and cold of space with no human hands on it.

Begoña Vila: Correct. Yes. Every time you launch something into space, you follow certain processes. We all have to do it, right? You do some ambient functionality to make sure things work. You have to do vibration and acoustics testing to make sure what you're launching survives the worst part of the journey, which is that launch on the rocket where it will be shaken and hear this loud noises.

Begoña Vila: But then you have to duplicate the conditions that instrument will see on our way. In our case, an infrared telescope operating very cold. So that's why we had to do the testing in the cryo chamber at Goddard and the cryo chamber in Houston to duplicate the vacuum and the coldness.

Begoña Vila: This goes to 40 Kelvin, and that was a challenge in itself. A lot of cold telescopes go to 80 Kelvin with nitrogen. To go to 40 you have to add Helium and that's a more complicated process. And of course, every time you cool down these big instrument with so many components, you have to watch it very careful that everything is cooling down as it should. So, lots of work to do those tests and is something that we'll monitor on orbit as well. How does that cool down go and make sure everything behaves as we need it to, to get there.

Mat Kaplan: 40 degrees Kelvin, of course, 40 degrees on the Kelvin scale, much like centigrade, but we're talking about 40 degrees above absolute zero. Very, very cold. And in vacuum during that testing. Did that testing give you the confidence that once this big spacecraft, because it is a spacecraft, gets up there, it's going to do what we need it to do?

Begoña Vila: Yes, you have very good points there. Vacuum, which is different, and on the ground we have to do a special testing to simulate that vacuum, but then that coldness it's so cold. We cannot build a telescope at those temperatures. We have to build them at ambient temperatures.

Begoña Vila: And I think as everybody knows, when you put something in the freezer, its properties change. So, that's true for this telescope as well. The properties of the materials will change and things will shift a little bit. So you have to make sure I build it at ambient knowing when it gets cold, it's going to go there. And that's where it needs to be.

Begoña Vila: So, lots of team effort modeling and then demonstration and validation. Those cryo tests were critical. The one at Goddard did all the instruments. Of course, you have to simulate the sky. We have to have the stars, and we had to simulate the sunshield. We didn't have it. And the mirrors, we didn't have them.

Begoña Vila: And then the testing at Houston, a much bigger chamber that we needed because the mirrors are so big. And that allowed us to check everything a bit better together. And also validate the process we are going to use on orbit that we mentioned before of aligning those mirrors. We had the fake star and we could see how to do that process.

Begoña Vila: So, I think we have done as much as we can. We have done a very thorough test campaign on the James Webb to convince ourselves we are ready. We are ready when we launch it for it to behave as it should.

Mat Kaplan: Simulating the sky or simulating stars, which never occurred to me. Of course, you would want to do that. How is that done?

Begoña Vila: Right. That's something which is a science project in itself. You have to have another instrument that's going to make light of different stars. You have to have the focus of those star similar to what the James Webb will have. You have to think about the light of those stars.

Begoña Vila: So, the instruments are picking up light in the infrared. So, a big effort to generate that optical support equipment that also needs to be tested in that chamber before you do it for real, to make sure it behaves as expected. So, always you have all these secondary activities that you need to do to demonstrate what you need to. And I can mention, because we are looking at the window here-

Mat Kaplan: I wish listeners had the view that we have now as technicians surround the base of the telescope. And a couple of guys on forklifts who have been pushed into the gut, into the interior of the telescope, just below the mirrors, just amazing to see this happening. And I've only now noticed some of the tech sitting off to the side watching as this takes place.

Begoña Vila: In deed. This is a various skill team. You need different skills here. I wouldn't want to be the one responsible for going inside there because it's such a critical portion of the fly hard where they need to know exactly what they are doing. They cannot touch the electrical components. They have to be grounded. They have to keep the cleanliness level. It's a very detailed and careful operations that they do there.

Begoña Vila: We have obviously tested how to deploy the mirrors and how to deploy the sunshield at ambien too. But people think about it, we don't have the zero gravity, so I cannot really just open the mirrors and open the sunshield. That will damage it. So you have to do a very careful, again, ground, support equipment that will offload the weight of what you are deploying without affecting what you're trying to test to demonstrate you can open it safely and you can close it safely.

Begoña Vila: So, again, a lot of around work that's needed from the team to be able to demonstrate and validate all the operations for flight.

Mat Kaplan: I also think of what it must have taken to integrate all of these components. I mean, enough of a challenge developing each of them. But as we know from other spacecraft, other projects that we've talked about on this show, the integration until you actually install something and see the holes that bolts are supposed to go through actually line up. But maybe more importantly, that the electronics all work together. I mean, is this also something that you've been a part of?

Begoña Vila: Yes, I mainly work on the operations of the instruments. So yes, I have been involved throughout to either develop or support the testing when it happens. And what you're saying is totally correct. Each component is tested at its level. If we start at the beginning, an instrument was tested wherever it was built, in Canada, in Europe, here in the USA, each of those teams tested the instrument and did the testing we mentioned before.

Begoña Vila: They did functional testing, they did vibration, acoustics and cryo testing. And they deliver it saying, "This is good. We think it's good." Now, you're going to put them all together and it's what you say, "How do you know you put them together correctly? How do you know all the bolts and all the pointing is good?"

Begoña Vila: Well, you have to do the testing again. Functional, vibration, acoustics, cryo. And that happens all the way through. The sunshield had to do the same, the mirrors had to do the same. And now when we finally came to Northrop, putting everything together, which you can see videos, I'm sure, online and on the JWST website, how cool it is to put the mirrors with the instruments with the sunshield and the spacecraft bus.

Begoña Vila: But then we had to repeat it all over again. Vibrations, functional, acoustics, we couldn't go with cold, there is no chamber on the earth as big enough to fit this beautiful instrument. But we did as much as we could, we're still doing it at ambient to demonstrate that nothing is broken. We did put it together correctly and it functions as it should.

Mat Kaplan: Something that I've just remembered. I mean, I've talked to so many scientists who are waiting for the data to start flowing from this telescope. And of course, hundreds more around the world. One of them who's been deeply involved with the project who I won't identify, I asked her, "What are you most worried about when it has to be deployed?"

Mat Kaplan: And she said, "It's that secondary mirror that has to lock down into place high above that segmented primary mirror." And that once that happens, then she's going to feel so relieved. I wonder, I mean, what's the thing that's going to happen that will really give you that sense of, "Wow. Okay. This is all going to do exactly what we want?"

Begoña Vila: Yes. I think that is a very good point. I think we are all watching for sure, the sunshield. We know the sunshield has to open and deploy for us to cool down. There is some redundancy there. The sunshield has five layers, we can do with four. So there is redundancy built in, but then the second one is the one that was mentioned. We need that secondary mirror to go down. If it doesn't, the light is not going to get to the instrument.

Begoña Vila: And obviously, there are other events that are happening in parallel. Other deployments that we need, but if we get to that secondary sunshield, what's left after that are the two wings of the mirrors that are folding. But we have done analysis of what will happen if the wings don't deploy.

Begoña Vila: I think provided we can get light into the telescope and it's cold, we can see a path for whether not to get the data, turn the instruments and start working with it. So, it will be challenging if things don't work depending on what it is, but I do agree. Once we get to that secondary, we can see the path forward.

Mat Kaplan: You mentioned that you've been a part of the project for many years, beginning even before you came to NASA, when you worked for a Canadian company, right, that was doing some work with this.

Begoña Vila: Right.

Mat Kaplan: Which brings up the international nature of this project, Canadian Space Agency, European Space Agency, NASA, of course. Is that something, I mean, have you interacted with representatives from those other agencies who are also contributing to the telescope?

Begoña Vila: Yes, indeed. For me, it is one of the more pleasurable between many parts of this project. I was working with the Canadian Agency. I continue working with them when I came to work for NASA. And because of my role as an instrument overall coordinator and deputy for operations, I work with all the instrument teams and it's a relationship that has been wonderful from the first cryo that we did at Goddard.

Begoña Vila: We have three cryos at Goddard, lots of ambient functionality, the cryo at Houston, all the ambient functionals here I feel is like part of a big family is a pleasure. You get to know the different team members. We all have different personalities, of course. And I always joke a little bit. The stereotypes for the different how a German person is, or a Spanish, or a Canadian.

Begoña Vila: And it's obviously not true. There is a variety, but you always feel there is a little bit of that in all of us. And it's truly a pleasure to develop this friendship and this working relationship with this team. We still have the six months of commissioning together, but very good friendships made and great work together.

Begoña Vila: And I think it's a very important thing for science that teaches all of us that we can really work together for a common good independently of many other things that we put in the way sometimes.

Mat Kaplan: It's one of the things we like best about exploring space that has become something that in general nowadays, no one nation does entirely on its own.

Begoña Vila: In deed. These big projects that answer these critical questions for all of us, for humanity you cannot do them alone anymore, and it's not good to them alone. I mean, we're all looking for the same answers, the same knowledge. So, it's truly a pleasure. I think that's a wonderful thing on the James Webb to have this mixed team working together.

Mat Kaplan: I know that you also do a lot of STEM activities, outreach activities, in part relying on your fluency in both Spanish and English. And I just wonder how much a part of your mission in life it is to share what you do and to share the thrill that we get looking out there.

Begoña Vila: Yes, I love doing a STEM and outreach bands not only to share obviously James Webb, I think it's a telescope for everybody. And I think on any subject, astrophysics, anything that we work on is not a specialty. I think everybody can understand it, everybody can get excited about it.

Begoña Vila: So, I love having a little bit of a part in engaging everybody and not thinking, "Oh, I could not do that. I could not understand that," which is not correct. So, I really enjoyed on both, and it is different the Spanish and English, I love both. It gives you a different feeling and it's a great part of what I enjoy in my job.

Mat Kaplan: Where will you be when that launch takes place in French Guiana? Any chance you're going to be down there?

Begoña Vila: Well, I'm going to be in French Guiana for the functional testing. I am not sure yet if I'll be there for the very end, but then for sure, I know where I'm going to be for the next six months, which is in the Mission Control Center in Baltimore in the instruments control rooms. So, I'll get to experience a little bit of both. And yeah, I can't wait. I think it's a wonderful ending of a journey. So, very looking forward to it.

Mat Kaplan: In some ways, even though you've been at this for 15 years, the excitement, the best of it is still to come obviously. Thank you, Begoña, it's been delightful talking with you. Best of success with this big telescope.

Begoña Vila: Thank you. It has been my pleasure. Thank you for having me.

Mat Kaplan: NASA Goddard instrument systems engineer, Begoña Vila. Also in town during my Northrop Grumman visit was Greg Robinson. Greg directs the James Webb Space Telescope Program in the science mission directorate at NASA's Washington headquarters. Greg spent 11 years at Goddard earlier in his NASA career, as you'll hear, that was just one of his many assignments. Greg, welcome to Planetary Radio. Great to add you to this very talented group that I've been able to talk to today as we look down at the James Webb Space Telescope. Welcome.

Greg Robinson: Well, thank you. I'm really glad to be here. We certainly appreciate what you all do and what you do for NASA and the space business. So I'm looking forward to it.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Well, you're the guys who give us something to talk about. So, thank you as well. Speaking of NASA, you've been all over the place. Deputy chief engineer, deputy center director at the Glenn Research Center, deputy associate administrator for programs in the directorate that you're still part of, The Science Mission Directorate headed by Thomas Zurbuchen, who's been heard on this show. You seem to be sort of a utility player or utility leader.

Greg Robinson: Well, sometimes you have to get the base hit, sometimes you have to steal a base, and sometimes you have to get the home run. I've generally gone where they've asked me to go to make a contribution to the agency. And I hope/like to think I've made contributions in all those areas.

Greg Robinson: Of course, each experience builds on the next, right? And so that's made me the, what I like to call, the whole person in space. I haven't said this before, but probably the right person for this job at the right time.

Mat Kaplan: Well, that's good. I think you have a perfect right to say that. You know better than most people that The Science Mission Directorate, you folks deal with what, something like a hundred different projects, missions, and so on? This machine out here, the Webb, it's just one of those, but it's certainly one that has gotten a lot of attention.

Greg Robinson: Rightfully so. We have, depends on which day you count, 114, 115 missions in various stages of formulation development and operations on orbit. So, it's a huge portfolio crossing all of the science themes, but Webb is the mother of them all. And I often say Webb is our Apollo on the science side. It has that kind of cachet. The world knows about Hubble for 30 plus years, and this is a hundred times better than Hubble, if you could just wrap your brain around that. And I'm still trying.

Mat Kaplan: I'm still trying to wrap my brain around just actually being in its presence out there. Tell me about your job now, which is pretty much devoted to this telescope.

Greg Robinson: Both arms were twisted just a little over three years ago to take this job. I was happy with my last job, and this was around the time we'd just run into a few glitches on launch day and a few other issues. So, I'm the program director. I think you've talked to Bill Ochs, he's the project manager out of Goddard. And I often say that's where the heavy lifting takes place, right?

Greg Robinson: As you mentioned, utility player, my job is to ensure that the project is doing what it needs to do to be successful, to be the interface to SMD or the SMD lead in this case. And also to manage up, what, to the north floor, to the administrative suite and a lot of our stakeholder communications with the [inaudible 00:56:55], and OMB and others.

Mat Kaplan: A lot of interfacing between people with different interests, different skills, different jobs.

Greg Robinson: Absolutely. And that's what makes it tough. Because we are who we are personality-wise, right? And we have to deal with all of these different "interests", and I stress interests with quotes. But that's what makes it fun. And to do this for this mission makes it easy as well.

Mat Kaplan: We've talked a little bit with Begoña Vila and with Bill Ochs about how big this team has been from so many different agencies around the world as well. Sure, the engineering challenges are huge and the integration of all that engineering, but just that the people involved making all of them mesh so well, sounds like that is really a big part of what you do.

Greg Robinson: Well, it's certainly a big part of it. Again, the heavy lifting takes place from Goddard, from Bill's team. We've had several thousand people working on this over the years, engineers, technicians, hundreds of scientists across the globe. So, a huge supply chain with our contractors and sub-tier suppliers. It's kind of tiered, over certain times you deal with different pieces of that supply chain.

Greg Robinson: It's almost compartmentalized as it builds up. That helps a little bit. But certainly a large team, really, really smart people. And it's all about the people. And the key is learning how to make these people in these organizations work together in harmony. That's the key, but that's the hard part as well. And it can be fun when it's successful. And I think we're in that direction.

Mat Kaplan: Do you interact with the scientists on the project, and actually scientists who aren't on the project?

Greg Robinson: Yes, I do. On a day-to-day basis, the program scientist, Eric Smith, deals with the science community day-to-day, with interface with the Goddard Science team, with the project scientist. And of course, he works through the Space Telescope Science Institute, does a lot of the mission operations planning, and that's where a lot of scientists play into that. So, I deal with it on a gross level, top level. But day-to-day, Eric is that primary interface.

Mat Kaplan: Because you're at HQ, right?

Greg Robinson: Correct. And Eric is as well. I have a very small team there, rightfully so. So he does a lot of that heavy lifting on the science side. He is a scientist as well.

Mat Kaplan: Chief scientist, he's now chief scientist of NASA, of course, Jim Green. We got to know him when he was the head of the Planetary Science division. Is that also somebody who drops in now and then and has things to say about the development of the James Webb Space Telescope?

Greg Robinson: Absolutely. So, Jim stays engaged in everything that we're doing and the science mission directorate, and certainly for James Webb and the whole astrophysics side, he stays engaged in that. Because he helps set the vision for science across the agency and the interfaces across the different mission directorate, whether it's part of human space flight or aeronautics or space technology. So, he helps set a vision across those. He doesn't do any of the implementation execution. So yes, he's still heavily engaged in the science mission directorate and in astrophysics.

Mat Kaplan: How do you and others make sure that as this gigantic engineering project comes together, that your sites are kept on the science that it's going to be doing for all of those scientists?

Greg Robinson: So, it's easy to forget about the science, certainly in the early stages, after you get through all the requirements and everything of what the mission needs to do, then it really shifts to engineering, best practices and requirements and standards and so on. So for many years, in this case, the heavy focus is on engineering and development, as it should be. But we often like to keep the science in the forefront of what we're doing, because at the end of the day, it's all about the science.

Greg Robinson: It's interesting how, in a lot of engagements I do now, most of the engagement and questions are around science. Two years ago, they were all about what are you doing to get this thing ready? So as we get closer, the science interest is growing exponentially like it did prior to the actual build on this thing.

Mat Kaplan: Do you foresee a time, and we hear all the time about all kinds of projects, including Rovers on Mars, about the tension, friendly tension, if things are going properly, between the scientists and the engineers, because the scientists always want to push the envelope a little bit.

Greg Robinson: Yes, that's a good, healthy tension. You definitely want to push the envelope for science. You don't want to do the same old stuff. Otherwise, you're not exploring, right?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Greg Robinson: Engineers want to get it just right. The best system possible. And sometimes that costs more, it takes more time. And the scientist says, "I can give up that small, second or third level of requirement if we just get the thing done," right? So, as a good tension, to get it in space so they can start getting science versus taking more time to add a little more robustness to it. It's a delicate balance, but that's what we do. That's really at the heart of development versus the mission objectives.

Mat Kaplan: I'm going to make a wild guess here and say that once this telescope is up there doing its job, there may be more scientists trying to get their minutes or hours or days of time making use of it than possibly any other scientific instrument in history. I may be exaggerating, but it's probably not by much.

Mat Kaplan: I'm guessing that the Space Telescope Science Institute has to deal with that for the most part. But is that also something that you have involvement with, figuring out, okay, this is how we're going to make this equitable?

Greg Robinson: So, that's actually delegated to the Institute to manage. So, beyond the ERO, the early release and the guaranteed science observations, we have these the cycle, general observation. So, we compete that. And back in April, we'd just selected close to 300 proposals across the globe. And they'd touch in many areas of astrophysics. So nearly 300 in our first cycle. And we did this cycle every year. And the competition is pretty fierce.

Mat Kaplan: I assume, even though you're probably happy to let the institute handle a lot of this, one of the jobs of headquarters is to make sure that there is some kind of a fair process in place for making sure everybody gets a shot, or at least as many people who deserve it get a shot.

Greg Robinson: Absolutely. So the institute, they have a lot of history. They've done this before and not just for Webb, and they've done a great job. And they've actually instituted some fairness in the process themselves. They have a process that tries to reduce bias. They have these blind evaluations. You don't know exactly who's submitted the proposal as an example. So you don't know if it's a male or female. You don't know which country they're from. You don't know which institution, all of those things that can bring in bias. Right?

Greg Robinson: And I can tell you in this process, they really selected a really, really good group. So, they're always looking for ways to make it fairer. Normally they will present those ideas to us at NASA headquarters and tweak here or there, but they're pretty good at what they do.

Mat Kaplan: So, at three years in change, you're the newbie among the people that I've talked to today, Bill, who was on Hubble. And then now for 10 and a half years has been project manager, Begoña, who actually adds some exposure to this project before she came to NASA. But you've had experience on so many other teams working on so many other projects. What are your impressions about this one and the team behind it and just how well this is coming together?

Greg Robinson: Well, first of all, this is extremely complex. I've touched a lot of missions. We often talk about Webb as special, unique, and different, and it is. I can tell you that. We've never done anything this complex, this grand, so it is different. We have a really smart team. People dedicated, been on it for years, 20 years. Maybe approaching 30 when you go back to the concept stage.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Greg Robinson: So when I talk about people crying when it launches, they've cooked this baby, and they're going to see it go off to college, and it's going to be a lot of joy as we do as parents. But there are a few tears as well, and we will see a lot of that. So yes, I'm the new guy. I've been on just over three years. I may shed a tear as well, because I've also embraced it.

Mat Kaplan: I hope that those of you who shed those tears will be smiling through them. And looking forward to that first light. Because as we've heard, getting it up there to L2, that Lagrange point, there'll still be a lot of work to do as it deploys and gets ready to do astronomy.

Greg Robinson: We have six months of commissioning as you heard, so it's a lot of work after we launch. The next big phase is getting all of these deployments out and getting everything stable and getting those early images to help us refine the commissioning. And then those first, what we call releasable images, will really be the big day. And that's when the elation will overpower all of us. I think every day I come out of the house now, I'm going to look up to the heavens after this thing gives us the first images. And I think a lot of people would do that.

Mat Kaplan: I'm not inside the project like you are, but I cannot wait for that time to come. For those of you who are part of this team, I hope that you will be that proud and more, because it really is going to be, knocking on the table here, a tremendous accomplishment.

Greg Robinson: You want a long lot of people behind you and in front of you who will be really happy when this thing is launched and commissioned and start operations. People around the globe will be waiting for this. And they will be quite happy, I believe. We think that physics books will be rewritten based on James Webb. So, it's a really big deal. I'm looking forward to it.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, Greg.

Greg Robinson: Thank you.

Mat Kaplan: Greg Robinson is the James Webb Space Telescope program director for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. I'm grateful to him, Begoña Vila and Bill Ochs for taking time to talk with us. And I'm also grateful to Northrop Grumman and NASA Goddard for making my JWST visit possible. It is time once again for What's Up on Planetary Radio, here is the chief scientist of The Planetary Society. It's Dr. Bruce Betts. Welcome back. Was that a seal impression?

Bruce Betts: Sea lion technically, but yeah, I just felt pinniped today. I don't know why.

Mat Kaplan: Well, you may have trouble as a pinniped dealing with the gift that I got you, which I'm holding up to Bruce right now. We can see each other. I'm going to open up the bag that they-

Bruce Betts: Oh, this is very exciting.

Mat Kaplan: ... stapled shut at the Northrop Grumman gift shop, the official JWST patch.

Bruce Betts: Oh, that's so cool. Thank you, man.

Mat Kaplan: Ain't it pretty?

Bruce Betts: It is pretty.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. I'll get it to you someday.

Bruce Betts: Okay. Awesome. Thank you. The Mars-Venus snuggle I've been promising for weeks. It's happening July 12th, Mars and Venus low in the west shortly after sunset. So in the dusky time, you will see super bright Venus and over the days before and after July 12th, you'll see Mars moving from above Venus to below Venus looking reddish, more than a hundred times dimmer than Venus. But they'll be actually closer than the width of a full moon.

Bruce Betts: Ooh, it's going to be cool, but make sure you try to get a good view to the Western horizon. For an easier target coming up in the middle of the night, just about right in the middle of the night in the east, we've got really bright Jupiter with Saturn yellowish kind of to its upper right. And there'll be up high in the south in the pre-dawn.

Bruce Betts: Mercury, it's tough. Mercury has gone away, but you might still catch Mercury low in the pre-dawn east. That's our sky. Onto this week in space history. It's another hard to believe for you, Matt. 10 years ago was the final launch of the space shuttle STS-135 Atlantis.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, it is hard to believe. Because it was 10 and a half years ago that I tried to watch a shuttle launch and unsuccessfully, so I never did get to see one lift off of the pad there. But man, that's just crazy.

Bruce Betts: You never got to see one? I'll see if I can do something and get another one scheduled.

Mat Kaplan: Would you? Thank you. I think it's worth it. I think there were probably others out there at least three or four of us who never got to witness the launch.

Bruce Betts: And yank them out of museums. It'll be great.

Mat Kaplan: We'll just steal one. We'll steal one from, I don't know, maybe L.A's-

Bruce Betts: This is a part of a great movie. We're going to need Nicholas Cage.

Mat Kaplan: I know someone who knows someone who knows Nicholas Cage, so I'm on it.

Bruce Betts: I've seen movies with him in it. My son does a fire impersonation of him, but I don't think that's relevant right now. What is relevant right now is that in 1979, two interesting things happened this week. Probably more than two, but I'm going to tell you about two. Voyager 2 did its Jupiter fly by before it headed off to three more planets and Skylab re-entered in a fiery re-entry spreading material across the Indian ocean and a little bit into Australia.

Mat Kaplan: I remember that. Boy, that was a big deal too. Yeah.

Bruce Betts: Remember the people selling T-shirts with targets on them?

Mat Kaplan: Yes. Yes, I do as a matter of fact.

Bruce Betts: All right. We move on to the promised [inaudible 01:10:51]. So according to NASA, and I believe them, but I just say that because I haven't actually done the calculation myself and it is so amazing. The James Webb Space Telescope will be so sensitive.

Mat Kaplan: How sensitive will it be?

Bruce Betts: It will be so sensitive that it will be able to see the heat signature, the thermal signature of a bumblebee at the distance of the moon.

Mat Kaplan: That's good. Okay, lunar Bumble bees, your time is up. Oh, that's a good one. You're absolutely right. Let's go on to that contest.

Bruce Betts: So we hope there's no space apiary in the way. I just wanted to use the word apiary. All right. We go onto the contest and I ask you, which is the only one of the 88 official IAU constellations named for an actual historic person? How did we do, Matt?

Mat Kaplan: You tell me how we did. What's the answer here? What were you looking for?

Bruce Betts: Coma Barney says, apologize, pronunciation's off, this name means Berenice's hair in Latin. And she was the queen of Egypt, Queen Berenice's II of Egypt. Counts as actual person.

Mat Kaplan: Rob Cohan in Massachusetts, long time listener has been listening to the show or at least entering the contest for at least five years. First time winner. So, congratulations, Rob. We're going to send him another copy of that terrific book Carbon: One Atom's Odyssey by John Barnett that we've been talking about for a few weeks here. So, enjoy that, Rob, and see it paid off.

Mat Kaplan: This should be a good lesson to the rest of you who are still waiting for that first win. I have a fun story for you among other responses that we got from people. And this is from Kent Murley in Washington. And it starts with this astronomer who worked in the Egyptian court. Conon of Samos later apparently of TBS needed to, but seriously folks, needed to cement his job as astronomer at a seaside temple to Arsenault II of library of Alexandria [inaudible 01:13:19].

Mat Kaplan: When Berenice II became wary of the late return of her cousin/husband, there is a story, Ptolemy III from the third Syrian War, she pledged her tresses to Arsenault aligned with Aphrodite and protection from shipwrecks.

Mat Kaplan: After the vote of her tresses went missing and the return Ptolemy III was doubly angered, a shone queen and a PR mess. Conon of Samos, waging spin, declared Arsenault had placed the trusses in the heavens. Ptolemy III was appeased, Conon lived and Berenice II went up in history. And he closes with this. To baldly go where no woman has gone before.

Bruce Betts: That is quite a story.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, well done, Kent. Thank you very much. Here are some more stuff. Curtis Frank says that the constellation also contains our galactic north pole. I didn't know.

Bruce Betts: It's a Southern hemisphere thing.

Mat Kaplan: Mathew Walter in Louisiana, maybe Conan the astronomer regaled the cord of Ptolemy III with random space facts. And Dr. Bruce can trace his ancient lineage to this noble wise man.

Bruce Betts: Oh. I know I'm going on to ancestry.com shortly.

Mat Kaplan: There were a lot of comments about splitting hairs. And speaking of splitting hairs, a lot of responses about a different constellation. Scutum or Scutum, which was originally named Scutum Sobiescianum or the shield of Sobieski, which apparently was named to honor King Jan III Sobieski in the battle of Vienna. This is back in the 17th century. Not really because Bruce was looking for a person, not a person's shield. Am I correct there?

Bruce Betts: That is correct. We're going to go with a no on that, but interesting historical reference.

Mat Kaplan: And here's another one from Mark Bailey in California, who is under the impression that Hercules may in fact have been a real person also. I think I've heard speculation about this. That Hercules may have been based on a living person.

Mat Kaplan: Finally, Ian Gilroy in Australia. Alas, as a follicly challenged member of The Planetary Society, I'm with you Ian. Such sacrifices are beyond me, but I wonder what the amply coiffed Bruce would be willing to sacrifice his abundant locks for. A successful sample return from Mars perhaps.

Bruce Betts: I would gladly sacrifice my ample locks for such noble rocks.

Mat Kaplan: It's true. Your hair is magnificent.

Bruce Betts: Aww. Well, thank you. And your hair is-

Mat Kaplan: Non-existent.

Bruce Betts: Had a good run.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, it did. It did have a good run. Live hard, fall out early. That's what that was.