Planetary Radio • Oct 07, 2022

Space Policy Edition: The Geopolitics of a Successful SETI Detection

On This Episode

Jason Wright

Professor, Departement of Astronomy and Astrophysics for Penn State University

Casey Dreier

Chief of Space Policy for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

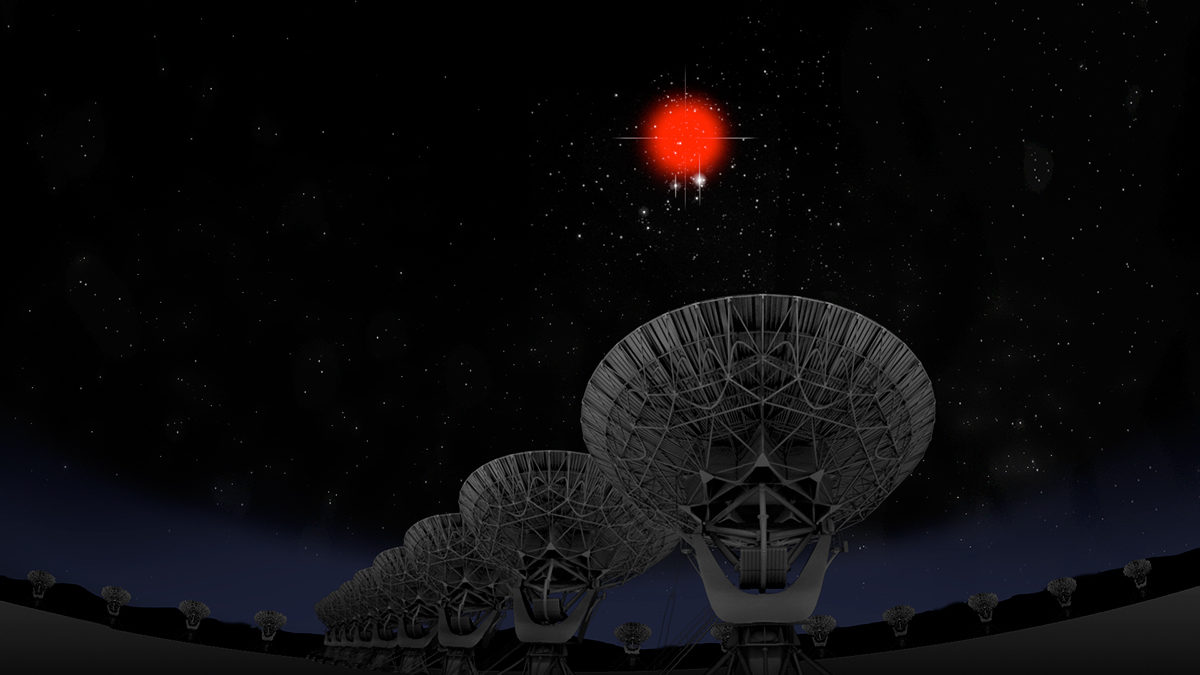

What would nation-states do in response to a signal from an alien intelligence? Would they compete for status and control of the message, or hope to gain some technological advantage from its contents? Or would the world shrug its shoulders and move on? Professor Jason Wright, director of the Penn State Extraterrestrial Intelligence Center, joins the show to discuss a new paper proposing a more nuanced and positive view of world behavior given a potential SETI detection, and how the most likely message we receive may be more ambiguous than we imagine.

Related Reading and References:

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: Welcome everyone to the October 2022 space policy edition of Planetary Radio. I am Mat Kaplan, the host of the Weekly Show, Joined as always by the Chief Advocate and Senior Space policy advisor to The Planetary Society, and my senior partner in the space policy edition, that's Casey Dreier. Casey, welcome, and happy continuing resolution season.

Casey Dreier: Yes, and happy fiscal New Year to all those who celebrate, October 1st is now the fiscal 2023 started. And like it's been, as long as I've been doing this, we do not have congressional appropriations yet. We have a continuing resolution. We've extended fiscal year 2022 through December 16th. It will cover obviously the period upcoming with the US midterm elections, the congressional elections, and they will reconvene right before Christmas to hopefully wrap up that legislation before the new Congress begins on January 3rd.

Mat Kaplan: There is so much more that we could say about this and we will maybe next month when we know more. Right?

Casey Dreier: Well, next month I believe our show comes out before the midterm elections. It's always the second Tuesday of November. Our show comes out in the first Friday, and so we will proceed that. We will take a look at some of the close races at the time. As usual space as not a big defining topic for most elections coming up in the US Congress, but we will highlight a couple of competitive races and try to see what consequences they may or may not have for Congress next year. And of course, which party controls Congress will make an impact as well.

Mat Kaplan: And apologies, that's what I meant to refer to for next months show, it'll be our election preview. Is there anything you want to say though now about how things are shaping up? I'm thinking in particular of the bills that were passed by Congress and the Biden administration, which did have some impact for NASA and space exploration and science at large.

Casey Dreier: Well, the biggest bill was the NASA authorization bill that passed within chips and science bill, this is a very large industrial science policy. And we've talked a bit about that. We'll dive into that in a future space policy edition episode. But just really in general, good things for planetary defense. I should acknowledge since we recorded our last episode, we saw, all of us hopefully who's listening to this, the first demonstration of a planetary defense mission where DART successfully... I think the only spacecraft, well not, I don't think so actually. One of the few spacecraft designed to smash into something on purpose, that was the known end of the mission and succeeded in smashing itself into that small moonlit of an asteroid Dimorphos. The opportunity to talk about planetary defense was great because it really raised the issue of what's next. And of course what's next is Neo Surveyor, this deep space infrared planetary defense telescope that is suffering from some pretty significant budget cut proposals in this 2023 fiscal year budget.

Casey Dreier: The two congressional bills that we have seen, one in the house, one in the Senate, that have been proposed but not yet signed into law, this is what was just delayed. Both of them restores some funding to Neo Surveyor. The Senate restores more, it's on the order of $90 million. The house restores less, it's on the order of 40 million, again off of a baseline of what we expected and needed for the project of 170. So there's progress in both of those and the Senate has the better number and overall the better number for planetary science. But of course this all needs to be worked out yet and passed into law and melded together by December.

Casey Dreier: And of course, that's far from certain considering that the post lame duck session, the post session of the elections, really will depend on what the future of politics is going to be to see whether or not it makes sense to drive consensus or to have one party or another try to slow things down to wait until a perceived advantage in January when the new Congress convenes. So lots of uncertainty still unfortunately for this great mission.

Mat Kaplan: One that The Planetary Society has been throwing its support behind right from the start. And everybody that we ever talk to on this program recognizes the vital importance of having an infrared telescope in space to help us with this search. In fact, it will do wonders for this search for these objects that threaten us, of course. I do want to mention DART, the double asteroid redirection test, that great success. Congratulations again to the DART team. And of course, I had on last week's show as we speak, Nancy Shabo came on right after the impact, hours afterward, to help us celebrate that tremendous success. And I hope people have seen some of the truly incredible, they're not incredible, they're almost incredible images taken by ground-based telescopes and by LICIACube, that little Italian cube sat that was following along and really got some spectacular images.

Mat Kaplan: We have not mentioned yet you're terrific guest and the topic for this week, and it is one of the reasons I became a member of The Planetary Society many, many, many years ag. It's SETI, search for extraterrestrial intelligence. Before you tell us about that guest and introduce him and the work that he has just been part of completing, I'm a member, I know you're a member, Casey. Planetary.org/join is the place to go if you want to continue to hear this kind of reporting, a planetary radio and the space policy edition, and everything else that we do at the society, particularly all the advocacy work that Casey leads for us in Washington, DC, and elsewhere across the world, it all is made possible by our members. So again, we hope you'll check it out at planetary.org/join. Tell us about this fascinating guest and a fascinating paper that he has led the creation of.

Casey Dreier: Our guest is Jason Wright. He's a professor at Penn State, astrophysicist and astronomer and also the director of the Penn State Extra Terrestrial Intelligence Center. And so really has a lot of interesting focus on SETI. The paper was released just this week, it's called The Geopolitical Implications of a Successful SETI Program, and he's the lead author along with Chelsea Haramia and Gabriel Swiney. What really struck me about this paper was it's an actual reaction to another paper, and we'll talk about that in the course of the interview, but it tries to take a somewhat thoughtful approach to what the geopolitical consequences of what it would be like to detect a SETI signal. And we're really used to thinking about this in a cultural sense. And we've seen that in the movie contact and other things where it's like, "What does the culture do when presented with a new intelligence speaking to us?"

Casey Dreier: But the real question is, I think in terms of policy and the subject of this show is, what would nation states do? What would the consequences be? And would there be, in this case, a drive to monopolize inform and contact information about the message? Or is there alternative pathways? How would these states react to the potential or perceived advantage of maintaining a monopoly in this? And so it's a really interesting broad question. They have a really nice thoughtful response, there's a broad range of input here, and we'll really get into it on the idea of how we react as a globe to potential SETI contact.

Mat Kaplan: So we're actually recording this opening for the show just before Casey's conversation with his guest so I cannot wait to hear this. Like I said, it is topic that has always fascinated me. And the paper also addresses not just Seti the search, but METI, the active messaging of an extraterrestrial intelligence. That's also addressed... Right now I'm reading David Grinspoon's 2016 book, Earth in Human Hands. He approaches this also from the cultural standpoint for the most part. So yeah, looking at it from the viewpoint of states, after all, let's say that the country of Cameroon was the first to establish contact with an extraterrestrial intelligence and was given the secret to warp drive, Casey, I can't wait to hear this. And of course, you and I will be back on the other side to close this month's space policy edition.

Casey Dreier: Dr. Wright, thank you for joining us today on the space policy edition.

Jason Wright: It's my pleasure.

Casey Dreier: You and two co-authors just published a paper that I'm quite fond of, which is why I invited you on the show today, it's called The Geopolitical Implications of a Successful Study Program. And your co-authors were Chelsea Haramia and Gabriel Swiney. It's a response paper, which I think is itself an interesting example of the scientific process or the policy process working as it should. But it takes a relatively nuanced and detailed assessment of various proposals of how nation states might react to a SETI signal being received. But before we really go into your paper, I'd like you to characterize the paper you're responding to, which was called originally, and we'll link to this in our show notes, called The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, A realpolitik Consideration by Ken Wisan and John Traphagan. So what's the proposal in that paper and what caused you and your co-authors to write this one in response?

Jason Wright: Yeah. Wisan is a military officer or retired military officer, and John Traphagan is a philosopher who thinks a lot about the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. And they put this paper together to put on people's radars the potential for real problems when a SETI program succeeds. And we always want to plan for success. Your plan has to be more than just where you keep the champagne. It needs to be what you're going to do next, and that has to include how people are going to react. And they proposed that people who work in this field, were not ready for the potential big negative fallout geopolitically from nation, state level actors getting involved. It's not surprising that they wanted to highlight this particular potential fallout. It tracks the plots of movies like Contact or Arrival, where as soon as contact is made, the military shows up and they're armed guards in contact literally right there in the control room at the very large array, and they're concerned about national security and whether there needs to be military intervention to deal with this whole thing.

Jason Wright: We understand why they have that. And so what they're concerned about is that there will be some information when we make contact in the message that we can decode that there will be something about how physics works or something. And that whoever sent the signal will almost certainly have been around with technology much longer than humanity. And so there might be morsels of physics or engineering in that signal that would potentially give one nation state a huge military advantage, maybe something like you could build a weapon. And so this was one of the big concerns of contact for instance. And so they were concerned that one nation state, using a big radio telescope, would monopolize conversations with the aliens and be able to control what they think they know about us, control the information flow, get that information, and then turn it into a strategic advantage globally.

Jason Wright: Importantly, they didn't say this is likely going to happen, they said that the possibility that it could happen means that we need to prepare for that, we need to be ready so that when a signal does come down and nation states potentially do that, our telescope facilities are hardened with their security and SETI researchers involved have personal security so that bad things don't happen to them in the telescopes.

Casey Dreier: When I read their paper, it actually struck me as plausible upon my first reading of it. This idea, and I think it's playing upon historical analogy and the idea that there's a competitive, and their whole definition of realpolitik is, they admit is somewhat vague as I think most people acknowledge it is, but roughly that means the exercise of power as the transcendent motive for state actions over morality or anything else.

Jason Wright: Right. That at the top level, if you just ignore the details, that nation states basically pursue power, they act in the interest of their own power, and that they only respect other nation states power ultimately. And so if these signals give whoever is in communication power, military power, then that would be something to compete over. And then you would have espionage and you would have competition over that, and SETI practitioners and radio telescopes would be stuck in the middle.

Casey Dreier: The key point I think what I liked in their paper was that they admit it's not even that it would necessarily actually confer a competitive advantage, that there would just be a perception.

Jason Wright: That's all it takes.

Casey Dreier: That's the key thing. So regardless of what the signal in this case would actually be. What did you find incorrect with that assessment? And you and your co-authors, I should say to you, this is not just you.

Jason Wright: Off the bat, I felt like it misunderstood how radio astronomy and SETI work. I thought that the nature of contact that they were imagining was actually impossible, even optimistically. And I thought that their solutions, the things they thought nation states would do, go get the radio telescopes, wouldn't work. And so it wouldn't be something you'd want to do. And I thought that their solution was counterproductive. And so I thought their paper would've been better if they had talked to or had as a co-author, a SETI person, a radio astronomer who could've corrected some of those misconceptions. But I didn't want to just come back and write as a radio astronomer with no background in geopolitics, no connection to the military, no background in philosophy, and argue with these people who are experts in those fields about things I don't know much about.

Jason Wright: And so that's why I went and I got some co-authors. One of my co-authors, Chelsea Haramia is philosopher who specializes in the ethics of astrobiology, especially SETI. And Gabriel Swiney was at the State Department for a long time doing space law and was an architect of the Artemis Accords. And so really understands how nation states actually handle sensitive topics with potential military applications like going to space and things like that. So the three of us crafted a response, pointing out the problems with their paper, but then also suggested what we think we should do because we agree that nation state's misunderstanding SETI might overreact in silly ways that are irrational, and we should think about that, but we don't think that the right solution is to act like it's foregone and start hardening security and preparing for that. That might actually imply that we found something or imply that reaction is appropriate from nation states if we go first.

Jason Wright: And so we didn't think we should start that arms race now. Another reason is that if you were to try and treat radio telescopes the way we treat nuclear facilities, for instance, which have a lot of security for good reason, it just wouldn't work. Radio astronomy as we know it would not survive that sort of treatment. These radio facilities are open to the whole world. It's very transparent. It would make astronomy much less efficient and much more expensive to do that. And so you need a good reason, and we don't think this is a good enough reason to do that.

Casey Dreier: I'd like to unpack some of the technical issues first because it's actually really fascinating for me. So I will admit that SETI is an area that I am still learning about. I've been reading a lot of papers in the last few years and coming up to speed, but this discussion between these two papers really illuminated to me the gap, I think in, I'll just say it, generalist understanding of SETI versus the advancements that have really been made in analysis and thinking about the potential topic and what a signal might even be. What really struck me, I'd like to talk about just a couple of the critiques that you make about what a signal might actually look like and the assumptions being made, I think not just by these authors, but actually I'd say most people when they think of what a signal, it's going to be really defined by popular narratives of what we've seen in Contact or Arrival or any number of things.

Casey Dreier: And I think it's a function of our brains really seeding or latching onto the idea of an event like a discrete event where something happens and it's really clear and it's a message that wants to be decoded. So at first, I'll start with this critique that you talk about how the scenario presented is very unlikely given the range of possible scenarios. And one of those is the idea that they will be a single message that is meant to be decoded, being received, that's very, very obvious. And you talk about this idea that the actual process of detecting or even confirming a signal could actually be an ongoing and continuous process. So step back and let's explain what type of signal in terms of likelihood in the SETI community now, what are we actually expecting to find or what would even be argued as most likely scenario that we would face, and how do we then make the decisions based on that in terms of policy preparation?

Jason Wright: Yeah, people's view of what SETI is and how it works really goes back to the beginning to the Frank Drake and Project Ozma at Green Bank Observatory. And back in the 60s when radio SETI tarted, it was only just barely possible for humanity to be able to send a signal that humanity might be able to detect at interstellar distances. And so when they talked about what kind of signal you'd have to detect, it would have to be something really powerful and probably almost certainly directed at Earth specifically. Anything else would be too weak. So they wrote in their early papers, they would love to try and eavesdrop on their equivalent of cell phone transmissions on their planet. But over interstellar distances, those are just so weak you have no hope of detecting them. So what they were looking for were powerful radio transmissions deliberately pointed at earth to get our attention because those were the only signals that the telescopes at the time could detect given their sensitivity.

Jason Wright: And so if you're thinking, "Oh, they're sending us a powerful signal," then you've already ascribed all these different motivations to them that they want our attention, they're going to do something that we can understand. In the film Contact, they sent it back using our modulation techniques so that they knew that we would quickly be able to decode it. If they've already received our radio transmissions, then they might know the languages we use, they might know our mathematics. And so it was possible that there'd be this strong signal that we would immediately decode and would have all sorts of useful information in it, which is what happens in Contact.

Jason Wright: But aliens don't have to be doing that. At the time that was the only thing you could look for, and so the stories were, "If we find it, it'll be amazing." But if aliens are out there just doing their things, sending out radio aids, maybe their weaker signals or talking to each other, not to us, and we pick that up, there's no reason to think we could decode it. If it's a totally alien modulation scheme and they're talking in their own computer language, it might be impossible to figure out what's going on there, especially if it's encrypted, at that point you're done. The road to discovery has changed as we've gotten more sensitive and thought about these other ways to find things. We also don't only look for radio waves now, we might look for the waste heat of alien industry on another planet, or we might be looking for laser signals, or we might be looking for probes in the solar system or something.

Jason Wright: And so that scenario that's in Contact, that Project Ozma was imagining, is now just one possibility in a big wide range of things that we might find. Now that said, their argument that, that is what we'd find, it's what we might find. And it's in Contact, it is something we talk about as a possibility. And so it's not unreasonable to prepare for that outcome, that after all is the most exciting possible outcome of a SETI search. But yeah, I think the more likely thing is we'll find something weird, we'll wonder if it's aliens, we'll argue about it. We'll slowly settle in, "Yeah, that really can't be natural. We really think we keep seeing radio waves there." And then it's like, "Okay, there's an alien civilization there," but it's not like we're in contact with them.

Casey Dreier: This is the essence of a techno signature in the sense that we have a bio signature doesn't mean we found a little organism zipping around that we can study. We've seen a hint of something theoretically, right?

Jason Wright: Jill Tarter, who's one of the founders of the field of radio SETI, coined the term techno signature to make the analogy to biosignatures explicit and to remind us of the huge range of ways we might detect technology. And so that beacon that we were talking about, that loud signal that has the information, that would be an example of a techno signature, but we're looking for a much broader range of techno signatures than just that. Only in that situation, that's step one of a lot of things that have to happen for their concerns to be valid.

Casey Dreier: And thinking about this, just the range of techno signatures are so much broader than a directed intentional signal than you're just reasoning by statistics that there's probably many more ways in which we'll find... There's more techno signatures than there are directed signals probably.

Jason Wright: I don't know what the probability is. If they were writing this paper in 1965 then yeah, that might be the only thing you could discover. But there's many more options now and success has a lot of different faces now.

Casey Dreier: Do you think the SETI field internally has moved beyond the intentional signal as the driving force of discussion at this point? As you were describing this from the historical, and it's not just I wonder if the historical sense of what was detectable, but it certainly seems like... I wrote about the 25th anniversary of Contact just the other month and I was really struck revisiting the book and the movie about this pseudo religious projection that's being placed into that whole context of wanting something external to come down and save us from ourselves and represent this utopia that is so far denied to us. And it's a projection of faith that we would look out and it's a signal that wants to be detected, that wants to help us, that has all this possibility. But it really again seems like a projection of different desires.

Jason Wright: Sagan is pretty explicit about the religious nature of that. And look, it's an explicit theme now.

Casey Dreier: And that's so seductive and desirable to think about, it dominates the conversation. So is that a productive aspect to keep focusing on, or like in this paper, you almost see it as a misstep that they focus solely on that scenario based on these broader range of things?

Jason Wright: Yeah. I can only speculate on this, I haven't studied this stuff from a social sciences perspective, but I imagine that one of Carl Sagan's purposes in writing it that way was a corrective to a lot of science fiction where the aliens want to eat us. Ever since War of The World's, contact in science fiction has involved often evil aliens coming to go get us. And there's some good ones, there's Close Encounters of The Third Kind, there's ET, and those are nice. But for the most parts, the soldiers come with guns and we try and shoot down the UFOs. And so emphasizing that we don't know what contact will happen, and you might worry it'll be bad, but it might also be incredibly good. It might be the best thing that ever happened to humanity. And we just don't know. You can't rationally make a decision when you just have no idea what's going to happen.

Jason Wright: But we also wanted to emphasize that it doesn't have to be dramatic. The more likely outcome is that we'll just know they're there. Physical contact means that they're here in the solar system. That's one kind of SETI that people do. But for the most part, the stars we're targeting are hundreds or thousands of lightyears away. And so even if it is a communicative signal, even if that signal is intended for us to decode, we can't respond. We can send the signal back, but if the thing is 200 lightyears away, then we say, "Oh great, we got your message. Tell us about X, Y, Z." And 400 years later we get the answer. So this is not going to be the sustained contact where we ask questions, "How do your laser beams work? How do we put them on our tanks?" That's not going to happen. And that's I think one of the misunderstandings they had in the Wisan and Traphagan paper.

Casey Dreier: Another thing you identify is the idea of monopolizing. So I want to put communication off to the side just for a minute because that's a a whole other aspect of this. But even in terms of receiving, they make this argument that radio telescope observatories, they're big, they're expensive, there's a handful of them around the world capable of detecting a signal like this. But you point out that, I liked what you said, once a signal is received, the requirements to detect it shrink considerably. So is it ever possible to have a monopoly on the reception of such a signal? Again, giving this range of what a signal would look like, but in terms of just radio astronomy in general, you're receiving a signal, it's used as a analogy here. Why can't that work?

Jason Wright: That's right. So the radio waves from space are hitting the whole planet. They're not going to be targeted at a specific observatory. That's just physics, they're going to hit the whole planet at once. And so the question is, who can receive it? So when we build these giant radio telescopes for radio astronomy, you have to understand there's not just one frequency we look at, those observatories have over a factor of a hundred in frequency that they can search at often. And they have a lot of different kind of spectrographs and other things on them to do different kinds of radio astronomy. And so they're general purpose instruments. They have many backends, many receivers. And so they're really expensive because they can look anywhere in the sky and they can do any radio astronomy. But once you know it's at this frequency coming from this place and this is the bandwidth of the signal, then it's easy. Then you just need one instrument to do that. And it doesn't have to be general purpose.

Jason Wright: So the analogy I use is that our modern observatories are like toolboxes that you can build a house with. But once all you have to do is turn a screw, then you just need the screwdriver and that's a lot cheaper than a toolbox. Our point is that once the information and where it is and what frequency it's at, is out, then you don't need those general giant observatories. Now, there is one case where you could do it, and if it's a very weak signal. So there's this narrow range of strengths where it's weak enough that only the largest telescopes in the world can decode it, but it's strong enough that you can still decode it with those telescopes because detecting it is much easier than decoding it. I suppose that could happen.

Jason Wright: That's a very specific signal strength that seems unlikely to me. But also you can combine radio telescopes together and by radio telescopes, I mean satellite dishes. And so any information monopoly you could establish by controlling the radio observatory that's looking at it would be pretty short lived because someone's just going to rig all their satellite dishes up together and get the same collecting area and now they've got it too.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, they do that in the deep space network all the time, use their 34 meters, phase them together to help augment or replace the 70 meter.

Jason Wright: Although in this case you don't even need to face them up, you could just do an [inaudible 00:28:49] and add it up. It's a pretty straightforward task, I think.

Casey Dreier: This is why I think it's so interesting combined with your argument about this time domain aspect where even if you are able to communicate, you could build a new facility in 10 years if you wanted, faster probably if you wanted to. And so any competitive advantage a nation would have from its existing infrastructure as you point out would last very short amount of time.

Jason Wright: Very short. Think about how many radio dishes there are on earth, all those satellite dishes, and how do you know which ones are doing that and which ones are just doing life. So yeah, it doesn't seem feasible.

Casey Dreier: Is there any opportunity then for a monopoly? Physically it sounds like no, just in terms of how the physical world works for something like this. Beyond what you just identified as this really weak but strong enough signal, but even then there's still like the fast... China has these big telescopes.

Jason Wright: They have their own telescopes and we can link them together. And so the only way is if somehow the signal were detected and no one knew where it was or what frequency it was at, and they had to find it themselves. Now, knowing it's out there, you're going to put a lot effort in finding it. And so that might be shortlived anyway. But the SETI community is extremely transparent about what stars they're going to be looking at and posting their data out for everyone to see. And the protocols that we have are that you let everyone know the frequency and position as soon as you're sure it's real. And so the only hope you have of a monopoly is right when it's detected, no one talks and that's just not how we work.

Casey Dreier: I suppose to give credence to this realpolitik attitude, if it was this perceived advantage, even if it wasn't wrong, that you could gain a monopoly by, if your nation detects it first and then, to the point of this original paper, you could sabotage other large astronomy facilities right away. But all that does is delay it. Obviously that's a provocative action to take globally. It depends how much perceived advantage is conferred there. But that's, to your argument of this entire paper, a relatively extreme scenario. Probably not the most likely thing. You mentioned in the study, it's not code of conduct, it's the protocols. Those exist. That's important to acknowledge that those are out there. What generally do the SETI protocols say?

Jason Wright: For decades, the International Academy of Astronautics has had a committee, a permit committee on SETI. And this is where stronger working in the field from all over the world get together to talk about these issues, in particular post detection protocols, which is what do you do after a discovery. In 1989, they put forth the declaration of principles on how to do SETI and they tell us how we're supposed to act. And so the first thing you're supposed to do is confirm it's real, we don't want false alarms. And that's proved a little impractical. We're so transparent about this stuff, it tends to leak out that we found something cool. I remember the Proxima signal and Tabby Star, and the recent FASP signal, and we always check, we never say it until for sure. But it leaks out and so that one feels maybe not like it works very well.

Jason Wright: So you have to check and make sure it's real and get it confirmed by another group with different equipment at a different site, because what you're really worried about is that you've actually just detected local radio transmitters or even it could be spoofed, which would be bad. So once another group has independently confirmed it, then you tell everybody, you tell the United Nations, you tell your governments, you tell other scientists, you put it out on the astronomers telegram, so it'll go out within an hour. And you don't respond, is the last one. You let the world figure out how it's going to respond to the signal.

Casey Dreier: Rapid and open sharing, and then no action taken.

Jason Wright: Well, no response taken.

Casey Dreier: No response taken before some global consensus can be met. That's an important point that this has been considered and thought about for decades and the conclusion was the opposite of hunkering down and monopolizing the idea.

Jason Wright: Yeah, absolutely. And keep in mind this is 1989 and so Carl Sagan and others are thinking about this, and I think these heavily influenced things like Contact, that once the cat's out of the bag, there's not very much a government can actually do to even try an information monopoly, even if it were possible.

Casey Dreier: It's one of those things I think where I was thinking an analogy, this is very similar to how we've set up early detection of potentially threatening asteroids through the neo detection networks. You can almost make a similar reasoning analogy to the monopoly of knowing that an asteroid's going to come our way and that could confer some power. But the problem is that all this stuff is open and immediately shared. All this data is published raw to these centralized databases as soon as they find them. There's no attempt, it's actually the opposite, there's an attempt to openly share this as much as possible to remove that right distrust created by monopolizing information. So I thought that was an interesting comparison that this is a trend in terms of actual implementation in these scientific fields has been open transparency, not the opposite.

Jason Wright: That's right.

Casey Dreier: Do you find that applies globally or is that generally a...

Jason Wright: In general, yeah. In general, it's pretty open. With the asteroids, the point is the raw data go out before you know have found something interesting. And so anybody looking at the data could come to the same conclusion. It's already gone. Once it's out there you can't bring it back. The protocols are pretty widely well known in the SETI community. Wisan and Traphagan can point out, they have no legal force. This is not a treaty. There's no call on governments to force SETI practitioners who abide by them. It's completely voluntary. State department's not involved. It's just this document that we know about. And so we don't have to do it, but we all know about it and they all make sense. And more importantly, we all have buy-in because the ongoing conversation for the post detection protocols are happening alongside all the other work.

Jason Wright: We just had a symposium here where we were talking about all the new SETI things, and right in the middle of the symposium we had this really nice long days long session about the post detection protocols and what you should do if you find something. And a lot of those are actually mostly concerned with how is humanity going to react, not just at the nation state level, but just in general. Will there be apocalyptic cults? Are you going to be getting harassed online and in real life? And what's what's going to happen afterwards? And so that's where the Wisan and Traphagan paper is interesting because it's really interested in the nation state level.

Mat Kaplan: More SETI and even some METI when Casey and his guest, Jason Wright, return in one minute.

George Takei: Hello, I'm George Takei and as you know, I'm very proud of my association with Star Trek. Star Trek was a show that looked to the future with optimism, boldly going where no one had gone before. I want you to know about a very special organization called The Planetary Society. They are working to make the future that Star Trek represents a reality. When you become a member of The Planetary Society, you join their mission to increase discoveries in our solar system, to elevate the search for life outside our planet, and decrease the risk of earth being hit by an asteroid. Co-founded by Carl Sagan and led today by CEO Bill Nye, The Planetary Society exists for those who believe in space exploration to take action together. So join the planetary society and boldly go together to build our future.

Casey Dreier: There's one more thing I just want to mention and then really moving on to the political analysis here, which is something again that is obvious in retrospect, but something we take for granted I think, this idea that you would get a technological benefit from communication with a...

Jason Wright: Yeah, we really dug into this.

Casey Dreier: And I loved that. I thought that was a really just excellent point. So summarize again, why should we not expect to be given some Encyclopedia Galactica, or even having it be relevant?

Jason Wright: So let's grant all their premise. It's a beacon, it's meant for us, we immediately decode it. It can only be gotten by one telescope, which your soldiers are in control of and you're getting this stuff and you can't respond but they just sent you everything you want to know. They're just like, "Here's the Encyclopedia Galactica, go to town." And then all of a suddenly imagine it's like one of these time travel movies or something, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, and suddenly we've got 27th century technology and out of the observatory come all these laser tanks and hovercrafts that perfectly cloak or whatever, and you've got a super army. Technology just doesn't work that way. And so the example we gave is, let's say we gave a textbook on nuclear warhead design and delivery engineering and physics to European medieval scholars and translated it for them. It'd be totally useless to them. There's nothing they could do with this.

Casey Dreier: They would invent electricity or invent calculus.

Jason Wright: Well first understand that there are atoms.

Casey Dreier: Right.

Jason Wright: Understand how to separate plutonium. The amount of time it would take you to... To hurry things up a little bit, you'd have the book, you wouldn't have to just figure it out, but the amount of... So much of science and technology, it's nonlinear and it's cumulative and it's networked. You need do this thing before you can do this thing. And they all come together. Until everything's working, you can't make that next step.

Casey Dreier: It assumes that to concede the idea that you can get some technological advantage right away from an alien signal would be that their technology is just right above.

Jason Wright: If it's seven centuries above, it's useless. It's got to be something that you're on the threshold of that you can understand and go, "Ah, okay, we can build that." And that's the next step. And our point is, if you're that close that just one little more or nudge pushes you over, everyone's pretty close. This is not this enormous advantage. This is something everyone's working on. And them seeing you do it, they're going to go, "Oh, that's possible and that's going to nudge them as well." And so even if there were some morsel that were super useful militarily, it's something that we're close to working on anyway and the advantage is going to be short lived. Again, there are probably edge cases, maybe there is just that one light bulb idea and suddenly we get our laser tanks.

Casey Dreier: I mean like what even you said that even if it does grant you say, "Oh, it shaves off 500 years of development," it's still maybe 500 years into the future, maybe just, we were originally going to do it in 1000 years, now we do it in 500. Has no immediate impact. And what I like about this discussion that you had in the paper, and even the paper that predicated this, is it really illuminates I think how fallible our brains are in terms of presentism where we really are seeing everything through the immediate existence. All of this is predicated on something being immediately relevant through the political dynamics we have roughly right now and only through our cultural lens. And again, it's humbling when you start to think about even if you did have a directed signal, it's still maybe likely to be completely meaningless because of the insane range of possibilities that we just ignore because we're so hopelessly steeped and stewing in our own human centric and cultural morph.

Jason Wright: Yeah, the way that they got around this in Contact is that it was our signals that went out that were the template of what came back. And then at the end it's her memories and her consciousness that they're using as the interface to talk to her. So it's all completely relevant, but again that's really contract.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. And to your point, for this scenario to happen the way it was outlaid to really have this realpolitik competition scenario, the whole point of your technological or your analysis here was that it's one unlikely thing piled onto another unlikely thing and then unlikely, unlikely that you're getting a directed signal meant to be decoded, has relevant technology just [inaudible 00:41:52] and so forth. And so it seems just, it's an unlikely scenario. And so again, I might just flip this around and say, before again we even move on to the political stuff, do you think, and just a gut, and obviously we're all speculating, but you can speculate as an expert in this field, what would be the most likely SETI scenario in your personal opinion that we would have? And then we can build off of that just as a thought experiment.

Jason Wright: I can make an educated guess, but again, I don't know likelihood. [inaudible 00:42:22] very agnostic about whether there's anything to find or what it might be like. But my guess is that it'll look a lot bio signature life detection, that we're going to see something odd, someone's going to say, "Hey, maybe that's what we've been looking for," but it's not going to be obvious. And people will come up with very clever scenarios that would've produced that and it'll be a long road of excluding everything else until aliens are the only thing left. And then, okay we know they're there. And so this is something Milan Ćirković calls bear contact. Bear contact is just, we know they're there. They're over there, they do something weird with radio. That's it. And there's not much contact there. And I think most people will end up being very bored with that. It'll be this gee whiz thing. The New York Times be very excited and everybody will go, "Gosh, they're out there. They're really out there. Wow. Okay, cool." And life goes on.

Casey Dreier: Maybe in the sense that we know quasars are out there, they're an amazing thing when you think about it, but it's so remote and distant.

Jason Wright: Yeah. It'll have this big impact on the intellectual history of earth. It'll be a watershed moment, but it won't change day to day life. Now, I need to be mindful of social scientist colleagues that work on these post detection protocol issues have repeatedly reminded us that these sorts of ideas of whether we're alone in the universe, they matter to a lot of people in a lot of ways. And it's not really clear how a lot of different groups who will respond. People have thought about, "Oh, what will the Catholic church think about there being other aliens? Do they have souls?" And it turns out the Catholic church is cool with that, it doesn't really matter. But there are a lot of other people that might react badly to that sort of thing and there's going to be repercussions for such a big idea.

Jason Wright: The scientists themselves will also become the focus of a lot of irrational stuff. They'll probably be targeted for harassment, and who knows? And so even if it's not state level actors that we have to be afraid of, we do have to be cognizant of the world we live in when you do something really big that people really care about. And so we try to work a lot with them to understand that and be more cognizant of the things that will happen when we succeed.

Casey Dreier: That's a really good point. I think obviously COVID was probably a really good example of the range of responses possible given a really unambiguous signal. So considering an ambiguous signal of that magnitude could really have a broad swath of things too, including, I think that's a really good point, consequences for individuals as part of this. I'd like to move on to some of the political critiques in particular, and we'll hit on just a few of these because I think they're just good counterpoint and I'd like to bring up some of the stuff that's been happening broadly and how you integrate this with your paper. But one of the political critiques is that realpolitik is not a correct way to really think about the motivations and interactions between modern nation states.

Casey Dreier: And I think as an alternative was really given prestige and influence seeking as with not more powerful. And you point out in your paper and your colleagues that receiving a steady signal would be one of the highest prestige events you could think of as a state. You would sing that to the rooftops, you wouldn't hide it, you would use it to show off how great your technology is or scientific capability is. Is that really the core of the political response and that this is a more likely scenario than a realpolitik one?

Jason Wright: We do make that argument, but to phrase it that way, it's not exactly rebuttal because Wisan and Traphagan aren't saying that the realpolitik analysis is correct, but they're saying that it is sufficiently plausible that that somewhat discredited worldview of how geopolitics works, it will still has some explanatory power. And if it has any that comes into play there, then you need to worry about it. That it's a low probability event, but it's a sufficiently severe one that you have to protect against it. We do point out that's probably not a good description of what will happen. We do point out that, just as you say, far from trying to keep it a secret nation states will want to monopolize the press they get for it and as you say, sing it from the rooftops, and that there are many more likely scenarios. The point we make though is that given there are all those other scenarios, some of which point in exactly the opposite direction, the question is which one of those should be action guiding?

Jason Wright: You can look at one bad thing that might happen and defend against it, but you can't do that to the exclusion of every other thing that could happen. What they failed to argue is that all other responses should be pushed to the side for that one. And given that these other responses also have tremendous benefits to states and that there are so many other things that can happen, we think that that's not the right response to just go and even precipitate that and just take it as a foregone conclusion and defend against it now is the wrong step to take.

Casey Dreier: I think that's a really good point to make, that really it's not that they're completely flat out wrong., it's what drives our policy going forward. And this is where I think you really push back against this idea of hardening radio facilities and SETI facilities, which you argue could precipitate the exact reaction they're afraid of happening. If you take a preemptive paranoid approach to it, you may instigate the type of behavior you're paranoid about happening.

Jason Wright: If the US government suddenly hardens down the radio telescopes whenever SETI people are there, and I have all this personal security, any rational person is going to think we found something and that it's really important, and immediately the espionage starts. And it's become a self-fulfilling prophecy. We argue that instead of taking it as forgone, we should prevent it in the first place because after all, it's going to be based on misunderstanding. And so let's make better standing instead.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, I think you have really interesting comparative analogies between a lot of the unidentified aerial phenomenon studies that are happening in the Pentagon, which are secret and therefore gain so much more attention for being secret and protective that people just assume that there's something there, whereas if it was more open, it probably wouldn't.

Jason Wright: Right. Those stories just drive me nuts. We know that the military is really secretive. That's not a secret. They'll be the first to tell you that. And it's very, very reasonable that they study the things in their airspace. I hope they do, that's their job. And so when this big government report comes out that was secretly studying unknown things in our airspace, there should be a lot of these. But instead it's, "Aliens are real. It's a cover up of aliens." Oh my God.

Casey Dreier: It's to the point, it's not a productive approach to these. Suppressing information is really hard. And you even mentioned that in the paper, that information itself is just leaks. It's a leaky thing. It's worse than molecular hydrogen when filling in a rocket. It just goes everywhere.

Jason Wright: And that's something that we say that the analogy Wisan and Traphagan one, is that hard and security like you do at a nuclear facility. Well, at a nuclear facility you have physical material that can't get out. That's what you're hardening it against. At the observatory, it's the coordinates of the target. You can't protect that with guns.

Casey Dreier: This all changes a bit when we're looking at METI, messaging or an active SETI scenario. So there you have a potentially monopolistic situation of who is sending the message or you just send a bunch of messages. Theoretically, if you're going through even a global coalition, what about the nation states that don't agree with the outcome of that? And you have a functional monopoly through the coalition decision. You kind of put that to the side and obviously this becomes a very unlikely scenario based on a lot of the conversation we've just had, but do you see a messaging scenario as to be a more likely competitive or antagonistic situation than just a passive setting?

Jason Wright: Yeah, I think so. There's a lot to unpack with METI and sending signals out, but it depends a lot on what we're sending signals to. If this thing is 1000 lightyears away, there's going to be a lot of messages sent in a light travel time. But this presumes that we know how to communicate back. It presumes that the signal we get tells us how to respond and that that response will be interesting. So the worst case scenario for METI for is we find something in the solar system communicating with us because suddenly you can actually have communication and handshakes, I mean electronic handshakes, and actually exchange information meaningfully. In that situation I think it does become important who sends what. If you need an extremely powerful transmission to be heard, like it's at the nearest star or something, then there really are only a few facilities that can do that.

Jason Wright: You can't do that with satellite dishes. You need a big megawatt transmitter on the back of an enormous telescope. And so that really could be monopolized. I agree with you that sending those signals, that is a case where you're talking about nation states making decisions and potentially monopolizing things. On the other hand, anyone can send the signal and the length of the monopoly could be short lived. Radio telescopes, once you know what you're doing with them, they don't have to be that expensive to build, millions of dollars, tens of millions of dollars. And so there's a lot of actors that could do that. But at least then in principle, yeah you can compete.

Casey Dreier: This is bringing my last topic here, which was, this paper I felt was mostly written probably before the war in Ukraine, the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Jason Wright: That's fair. Yeah, that's right. That's totally right.

Casey Dreier: I was really thinking about some of the arguments in terms of motivations of nation states and monopolizing information or even perceived advantage given what we've seen in Russia has been an anti influential or anti prestige action. They've lost so much global prestige. They've removed themselves from global cooperation as a consequence of that. And it hasn't mattered because it was a function of... And you even have a discussion with this in your paper, that the meaning of a collective interest of the nation state and who they represent. But at the end of the day, the cadre that controls the nation state takes action. And it almost was turning back to almost more of a realpolitik type of interpretation based on what we've seen recently.

Casey Dreier: And so that was really fascinating to me to think about what... And maybe realpolitik is not the right term for this, but I can see a problem with autocratic states in a situation like this where the perception may not be based in reality, but based in Putin resentment or delusion or puffed up ideas of national destiny or even a domestic audience that they want to retain influence and power over. It kind of goes back to this idea of, do you almost trust? So if there's an open sharing and an open presentation of data that's being received from a potential signal, you still have to have the trust that all that data is actually being put out there. And if there are motivated autocratic nations that want to define themselves against that collaborative global order, I could see that breaking down. So you're hearing my perspective, but I was curious, has anything challenged your approach to this based on what we've seen in Russia and also to some degree in China just in the last year in terms of how the behaviors of those states are impacting the globe?

Jason Wright: Just to riff first on our paper, one of the critiques we have about realpolitik is how do you define the nation state? As you say, it's typically a small cadre of people making those decisions, and it's really those people that control all of the power. You're not talking about the collective nation, you're talking about the small number of people in power. We also ask why is the nation state the right collective to point to? Why not giant corporations? Why not the planet as a whole? Just philosophically, how do you draw that line and why as a critique of realpolitik overall. As for what we've learned from the war in Ukraine, I'm just so out of my wheelhouse on this one. But I do my armchair amateur political analysis on all of that. But I think it's a good point.

Jason Wright: I do appreciate how you point out that Russia has destroyed its international prestige and that that's not the only motivation. I can also imagine if we make contact, there are going to be states that put themselves on the map by decoding the message or sending a message. You can imagine rogue signals from North Korea or Australia launches this huge program to be the premier detector of these signals or something like that. Or corporations. Elon Musk becomes the big player, who knows? So I do imagine, it's all about who has the resources and power to do something.

Casey Dreier: And this is where I think the messaging aspect to me really resonates more with the original competitive monopolistic fear or worried scenario, which again, we should emphasize, seems more unlikely. You laid out probably a more likely SETI scenario. And I don't really have an answer either, so it was interesting to me, again, reading this paper in the context of the war in Ukraine and thinking about motivations of states. And at the end of the day, I don't think Putin cares whether he represents all of the Russian people, he gains to do it and therefore acts in it. And so it's almost regardless of whether that's true or not, he has the power in that scenario. Which goes back again, unfortunately to this realpolitik kind of a structure of interpreting actions.

Casey Dreier: I could see a scenario in whether various nations refuse to accept the good intentions of a Western alliance dominated scientific system releasing information, whether they trust that or decide to trust it or not. Or what you said about North Korea is really interesting scenario as well. And how do you gain a jockey for influence through there. So to me, the story has become a bit more complicated unfortunately. This is all an unfortunate development, but really fascinating again, to read this paper in that context and maybe it could be an interesting area of future discussion.

Jason Wright: Well, the interesting thing about these post detection papers is that they really are focusing after a detection's been made. And a big point we make at the end of our paper is, until we detect it, we don't really know what we're doing. The nature of the signal, how far away it is, whether we can respond, whether we can decode it, those are all huge decision points that totally change the reactions of governments and people on earth. And we just don't know. And so for now, questions of should we transmit just seem so hypothetical that no one cares? People get upset about it, but governments don't care. People will sometimes ask us, "Does the government follow what you're doing in case you find anything so they can send the troops in?" And Jill Tarter likes to joke, "We wish the government paid that much attention to us because then maybe they'd give us some money."

Jason Wright: But the fact is, no one cares. And until there's a detection, it's just not going to rise to the level that the governments should even bother spending any resources worrying about it. And so what we have are small privately funded groups that occasionally make a big show of sending a message out, but they're not targeting anyone we know of. They're just, "Here's an nearby star, and for 30 minutes we sent a bunch of bits with a pretty weak transmission. If they just happen to have a giant telescope pointed at Earth right then at the right frequency, they'd get a bunch of bits. And do they already know we're here? Do they care that we sent the bits?" It seems so unlikely to matter that nobody with any authority cares. But that all changes as soon as we have a real signal.

Casey Dreier: To some degree, this is the modern angels dancing on the head of a pin debate at that level, let's get to the first detection. But again, I think what's valuable about your paper, and again, what I really did draw from it, and I think the real benefit here is, regardless of all these potentials, the least bad option going forward I the openness aspect. Given what little we know, the least destructive thing we can do is to just default to open sharing and then deal with it versus preemptive paranoia or consolidation or it's really leading into that openness. And I did take that away as a really strong argument from the paper itself.

Jason Wright: Right. Because I would hate for the scenario they outlined to actually happen, that would be bad. And if we aren't thinking about it, if they hadn't brought it up and no one ever worried about that, I guess it could happen. So now that we've thought about it and we've worried about it, I think we'd lean harder into transparency and more important educating people. The generals need to understand what SETI is so they don't have this reaction when it happens. They need to go, "Oh, it's not going to be anything that we can turn into a weapon, don't worry about it. It's not a national security threat, whatever it is." Or at least they'll stop and listen before sending in the troops.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, I'll direct them to write at all 2022 to help guide that thinking at the time. Jason, thank you so much for joining us today. This is a really interesting discussion. Thanks for you and your colleagues for publishing this really interesting paper. I wanted to give our audience, if they wanted to find out more about you or read your blog, what's a great way for them to find your writings?

Jason Wright: Yeah, I'm Astro_Wright on Twitter. There's an underscore in between. And I have a blog at Penn State, which you can easily find. Jason Wright Penn State will probably get you there. We also have the PSETI Center, which is the Penn State Center for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, where we do a lot of thinking about this stuff. And if you're interested in how you can support it because the government doesn't support this stuff generally, or you just want to follow along our research that we do there, you can go to pseti.psu.edu.

Casey Dreier: Wonderful. Thank you again.

Jason Wright: Thanks Casey.

Mat Kaplan: Planetary Society Chief advocate, Casey Dreier, talking to his guest, Penn State professor, Jason Wright. Casey, fascinating as expected. I look forward to talking again when we have yet another terrific conversation next month just prior to the midterm elections here in the United States on the Space policy edition.

Casey Dreier: Thankfully the geopolitical consequences of our conversations are less fraught than the ones we just were talking about. So it's something to look forward to unambiguously with optimism and opportunity.

Mat Kaplan: And if you look forward to things with optimism, well, join a whole bunch of other optimists by becoming part of The Planetary Society, planetary.org/join. I think optimism is one of the primary adjectives that could be used to describe our merry band, and we would love to have you on board with us. We have been talking, of course, with the Chief advocate for The Planetary Society, our Senior Space policy advisor, Casey Dreier. Casey, I will look forward to having another long conversation with you next month and hope to run into you before then as well. Thanks again.

Casey Dreier: Always happy to be here, Mat.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth