Planetary Radio • Mar 27, 2024

Eclipse Tips: A guide to safe observing and astrophotography

On This Episode

Ronald Benner

President of the American Optometric Association

Andrew McCarthy

Astrophotographer and founder of Cosmic Background Photography

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

On April 8, 2024, a total solar eclipse will sweep across North America. Ron Benner, the President of the American Optometric Association, joins Planetary Radio to share safety tips to protect your eyes during partiality. Then, astrophotographer Andrew McCarthy gives helpful advice about observing solar eclipses using telescopes and cameras. We close the show with our chief scientist, Bruce Betts, as he discusses The Planetary Society's new eclipse book for kids, "Casting Shadows," and the upcoming Eclipse-O-Rama festival in Texas, U.S.A.

How to take pictures of space You can take spectacular space images with your DSLR camera. We're going to show you how to get breathtaking photos of the Moon, star trails, and the Milky Way galaxy.Video: The Planetary Society

- The American Optometric Association

- The AOA’s Guide to Solar Eclipses and Eye Safety

- The American Astronomical Society Suppliers of Safe Solar Viewers & Filters

- Cosmic Background Photography

- The total solar eclipse on April 8, 2024

- What Is a solar eclipse? Your questions answered.

- Are your solar eclipse glasses safe?: How to protect your eyes during a solar eclipse

- Total solar eclipse 2024: Why it’s worth getting into the path of totality

- A checklist for what to expect during the 2024 total solar eclipse

- How to find eclipse events in your area

- How to host an eclipse party

- Why partial eclipses are worth seeing

- Sharing an eclipse with kids

- The Planetary Report: Seizing upon syzygy

- What is an annular solar eclipse?

- A guide to eclipse vocabulary

- Want to experience the 2024 total solar eclipse? Here are some tips.

- Your guide to future total solar eclipses

- Eclipse Explorer Junior Ranger Booklet

- Member Community Course: Solar and lunar eclipses

- Casting Shadows: Solar and Lunar Eclipses with The Planetary Society

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- Register for Eclipse-o-rama

- Register for The Planetary Society Day of Action

- Night Sky Photography for Beginners

- The Planetary Society Eclipse Shop

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It is time for some eclipse tips this week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. As of the release of this show, in just 12 days on April 8th, 2024, the next total solar eclipse will sweep across North America. This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for many of us because it's going to be decades before such an awe-inspiring sight graces this part of our planet skies again. We want this mesmerizing moment to be etched into everyone's memory, but not into your retinas. When viewing solar eclipses, safety is so important. The last thing we want is for this breathtaking experience to be marred by preventable harm to your eyes. Ron Benner, who's the president of the American Optometric Association, will join us to teach you how to safely observe the sun during partiality. Then astrophotographer Andrew McCarthy will give you some tips and tricks on how to watch the event through your telescopes or capture it in your cameras. Make sure you stick around for What's Up with our chief scientist, Dr. Bruce Betts. We'll talk all about The Planetary Society's new eclipse book for kids and our upcoming Eclipse-O-Rama Festival in Fredericksburg, Texas. If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it. The upcoming total solar eclipse on Monday, April 8th is sure to be an unforgettable celestial spectacle. It's going to be visible to tens of millions of people across Mexico, the United States, and Canada. To ensure that people in North America have the best viewing experience, we collaborated with The Eclipse Company to create a comprehensive web map and mobile app. The tool is a guide to discovering optimal viewing locations and local events celebrating the eclipse. We've also teamed up with Tim Dodd, the Everyday Astronaut, for a live eclipse broadcast. No matter where you live, you'll be able to virtually join us at our Eclipse-O-Rama Festival in Fredericksburg, Texas. That's where Tim is going to be streaming live. We're also thrilled to announce that Bob Pflugfelder, who's more popularly known as Science Bob, and YouTuber Mark Rober are going to be joining us at Eclipse-O-Rama. They'll be there along with our CEO Bill Nye, The Science guy, a fantastic cast of scientists from our board of directors and many of my fellow Planetary Society employees. Of course, the pinnacle of the eclipse is the moment of totality. The moon completely obscures the sun, casting day into an eerie twilight. Stars and planets may become visible and the sun's corona, which is part of our stars' atmosphere, emerges with a stunning clarity that you can see with your naked eyes. It's a phenomenal sight but very brief, and it requires precise positioning within a specific path on earth. For those of you who won't be on this path of totality but are still in North America, you'll be able to view a partial solar eclipse. These have their own beauty, but observing safety is absolutely crucial. To kick off our eclipse safety tips, here's our CEO, the one and only Bill Nye, The Science Guy.

Bill Nye: Here's an eclipse tip. You want to see the eclipse, but you don't want to look at the sun even with a pair of sunglasses, not even two pairs of sunglasses, not even 10 pairs of sunglasses. You need a pair of special eclipse glasses like these. Ah, totality.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So why is it so important that we practice safety when we're viewing partial solar eclipses? You may be wondering to yourself, "How is staring at a partial solar eclipse in any way more dangerous than just staring at the sun?" To get to the crux of the issue, here's Dr. Ron Benner. Ron is the president of the American Optometric Association. He previously served on their board of trustees and was the past president of the Montana Optometric Association. He's held numerous roles in the Great Western Council of Optometry and he runs a private clinic in Laurel, Montana. Hi, Ron.

Ronald Benner: Good morning.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So we're just days away from a total solar eclipse here on earth, and it's going to be a beautiful moment for tens of millions of people to be able to observe a really moving celestial phenomenon, but that also means that it's a potential for many, many people to accidentally damage their eyes by incorrectly viewing this thing. So why is observing partial solar eclipses without proper eye protection particularly dangerous for your eyes?

Ronald Benner: Well, let's take a step back on that one just a little bit and talk about what's good about it. So seeing a eclipse is something that most of us only get to see once or twice in a lifetime, and it's a pretty cool phenomena because people, they want to experience it. They want to have the opportunity to say, "I saw it," and tell their kids about it, tell the rest of the family members. The problem with viewing an eclipse is it's a pretty narrow band where the full eclipse is going to happen. It's only going to be about 70 miles wide in the part of the US where it crosses. Outside of that, it's not going to be a full eclipse, and when it's not a full eclipse, the radiation, the infrared, and the thermal radiation from the sun is something that can cause damage to the ocular tissue. If you think about going out in the sun on a normal day, if it's a bright, sunny day and you don't have protection, it's easy to burn your skin, it's very easy to get a sunburn. If you're welding and you're using high energy welders, you can also get what's called a flash burn or a burn on the front of the eye from the radiation coming off the welding. Both of those are very painful, but you don't always notice them right away. With a solar eclipse, it's kind of like a sunburn but different. Solar eclipse, the thermal energy from the sun, normally when we look at it, it's too bright, it's too intense, it's very uncomfortable. So even little kids will look at the sun for a split second and they can't do it. It's very uncomfortable within the ocular tissues. But in a solar eclipse where we're walking half that, it becomes less uncomfortable, but just as damaging. With the solar radiation coming through, when it hits the back of the eye we don't get a burn on the front like you do with a welder, okay, or with the regular sun, but with the solar eclipse, when you look at it and you tend to stare at it, we get actually a thermal burn onto the rods and cones of the back of the eye. Now people say, "Oh my goodness, I can go blind from this." Well, technically no. You're not going to lose full vision if you goof up and do this, but you can impair your vision dramatically and those impairments can be permanent. So when you look at the sun and you look at the eclipse, we have to make sure we're using full protection eclipse glasses, and we'll go through some ratings on those. But if you don't do that, there is that theoretical possibility you could burn the eye, and you're going to say, "How much? How long can I look before it burns?" And the answer is, it's different with everyone. Again, think about the sun. Some people can be outside in the sun for three to four hours and they never get a burn. Other people will go out for just 20 minutes and their skin burns. We all have different sensitivity levels, whether we're talking about the skin or the retina of the eye. Now, let's go to there. Retina is an extension of the brain. So these are very delicate neural nets on the back of the eye, and the macular tissue is a pure neural net where basically all that you have are rods and cones, and that information is your facial recognition, your reading vision, all of those things that we use to function in the real world and to manipulate around. So if you thermal burn those, you're going to see funny for a little bit, but six to 12 hours later it may get dramatically worse. Think of someone taking your picture. When someone takes a flash of you and they shine that bright light, you see spots for a minute. That's the photopigments, the rhodopsins and the opsins basically recovering and regenerating themselves in the back of the eye. But if you put too much energy in there, you're going to damage that photochemical process and damage those cells. They may work temporarily for another four to six hours, but then over that evening they may suddenly start to say, "I can't do this anymore," and give out. At that point, that's when we have permanent damage going on. So people, like a sunburn, you'll go outside, you may not feel it for six to eight hours. With a solar retinopathy, it may be the same thing. You may notice some weird vision for a while and think, "Oh, I did fine." The next morning you wake up and suddenly there's holes or blotches in your vision where things are blurry, color vision is altered, and it could be in one eye, it could be in both eyes. We hope it's in neither eye. From an eye care professional and an optometry point of view, we don't ever want to see this, but we do see it, and it's important for people to really be careful about this because we want to experience that solar eclipse. It's so cool to say, "I was there and I saw it. I took my glasses off during the full annular." Only if you're in that center 70 miles and you have a full eclipse is that safe, but I still counsel my patients don't do that because you don't know when it's unsafe and you don't know when it becomes safe, and it can only be a second or two on either side where we can actually get damage to that tissue back there. So if you're going to go experience, go experience, and I hear people on the radio and in articles say, "No, during the annular you can do it," but are you directly and is it a full annular eclipse or are you off to the side and still getting some of that thermal radiation coming from the sun. It's hard to tell.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's hard to tell. And I really valued what I read that you said during the annular eclipse that we had back in October. I was looking through articles, reading up on eclipse safety during annular eclipses, and I was very glad to see that the American Optometric Association was going out and speaking on this subject. Thankfully, the upcoming eclipse is a total solar eclipse, but we still have to be very careful about it. I definitely encourage people to keep a little timer or something going during the eclipse so that they are aware of when it's going to come out because as soon as we come out of totality, you need to be putting those eclipse glasses back on.

Ronald Benner: Right. Well, the other portion's here is to make sure that you're in the path of the total because it's going to look pretty total for a lot of people, but it's not going to be total, and you got to make sure you're in that direct path, that center 70 miles because if you're outside of it, it's never going to be total and you're still going to get damage at that point. Let's talk about using eclipse glasses and making sure you're using the right ones. One of the things we recommend is if you go out to the websites, you can buy these things on the websites, you can buy them at the local gas station and drugstore, but you want to make sure you're getting something that really works. So we're going to look for the code words and it's going to say ISO 12312-2. Those are the approved eclipse glasses. Those are glasses that are going to be safe and actually protect. If you take them out and put them on around the house and you look at a light, you're not going to see the light. That's how dark these are going to be. When you go out to watch the solar eclipse, you're not going to see anything until you look up to the sun with them on. So we always recommend put them on first before you go out and looking up. Don't try to find the sun up in the sky and the eclipse and then put them on. Put them on first. Look down, put the glasses on, then look up at the eclipse, again, making sure that you have the right ones. Two pairs of sunglasses, polarized sunglasses, camera filters, none of those will actually protect your eyes. So use the approved eclipse glasses. Welders helmets may or may not be close enough to that coverage, so just don't take a chance. We want you to experience, we want you to have the enjoyment of saying, "I was there and I saw the eclipse," but what we don't want have is a permanent scar that says, "Yeah, this came from me watching the eclipse," because that's a lifetime of potential vision loss. So make sure you get the right glasses. If you're not sure if you're getting them from a reputable dealer, the American Astronomical Society will have on their website you can find a list of reputable dealers. Several years ago during one of our eclipses, we had people selling things that were labeled with the right label but they weren't. So make sure you're getting them from a reputable dealer so that you're protecting yourself. This goes especially for parents, and honestly adults can manage themselves and we hope that they make the right decisions, but if you're going to take your kids out and let your kids watch the eclipse, what we really want to do is make sure that you're paying attention to the kids. Kids, especially little ones, don't always realize permanent consequences. So make sure that while you're enjoying it, they're doing it safely too. Have them practice. We're going to go outside now. Now we're outside. Put your glasses on and now you can look, but don't let them go ahead and do that. Do the kids first, then do you. It's the opposite of flying and putting the masks on. Put the glasses on the kids first, and then when you take yours off, make sure that you're paying attention to what the kids are doing too because kids can reach up, just take the glass off and still look and think, "Oh, it's no big deal." In all of our offices, optometrists across the country, we see people who are 40, 50, 60, 80 years old who have what looked like solar retinopathy burns in the back of their eye, but they can't tell us for sure that that's what happened. Suspected that when they were kids, that's when it occurred, but they weren't able to tell their parents, "Oh, this eye got goofy after the eclipse," because it didn't happen right then. It happened 10 to 12 hours later. So as parents, you need to really be protecting of your kids, and if you don't think you can trust your kids, if you've got two or three of them and you don't know that they're going to do it, do the safe thing. Go inside, watch it on the internet, watch it on TV, experience it that way, but be safe with your children, and your children have to come first on this one. So make sure they're doing it properly before you do yours. Before you put your glasses on and look, make sure the kids are in place.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And I'm very glad to hear that many of the states along this eclipse path are actually taking steps to do education for their children and potentially even shutting down some schools because having that many children out at once is very hard to make sure that they're all observing the sky safely. So if you're concerned that your kid might be in one of those groups, maybe just have them out of school for the day for the eclipse and do it safely so they don't damage their eyes.

Ronald Benner: Watch it on TV. Watch it on the internet. There's some great views. You can see it. You'll still see it get dark outside, but just be safe. Be safe. Children's vision is precious. They've got a lifetime ahead of them, and if there is damage to that photo net back in the back of the eye, that retinal tissue, it's there permanently. There's no treatment. There's no therapy. Some people, if they get a burn, they may come back. That vision may return in four to six months but not at all, and it's not worth the risk of a permanent lifetime of blurred vision out of that eye or blotchy vision or distorted color vision. It's just not worth it. So be protective of your child's vision.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, a good option is to always make a pinhole projector or some other device like that that you can use at home. But if someone does inadvertently stare at the sun during this thing, how urgently should they try to seek out the care of an eyecare professional?

Ronald Benner: Well, as I said a little bit ago, it's hard to tell. It's hard to determine when the damage is going to show up. Just like that flash, bright flash, your vision is altered for a few minutes, but it comes back. The older we get, the longer it seems to take to recover. But when we have a solar retinopathy, it may come back within the next four to five minutes. You may have a little bit of a, wow, everything's kind of wonky right now, but after four to five minutes it may come back, but the next morning you may get up and suddenly you're saying, "I don't see very good out of this eye. Everything looks blurry, everything looks blotchy." I try to describe it, some of my patients too, it's like looking through a screen. When you look through a clear window, things are just there, but when you look through a screen in that window, something's wrong. If the wires on the screen get pretty big, you end up with holes of vision, and that's what people describe their vision like with a solar retinopathy. If it's not a complete blur in the center, then it's pockets of vision because that thermal radiation on these very, very small rods and cones actually damages the rod and cone. So you may have two damaged here and one damaged there and another one over here, but you may have a mosaic of those that's not all in one spot. So you may end up with a hole throughout your vision, like looking through a very large wired screen.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'll tell this story later on in the show, but I had a friend when we were young who stared directly at a partial eclipse and it did not turn out well. So please, please be safe, everyone out there. This is going to be a great moment, but there are consequences if you don't do it well.

Ronald Benner: If you do think that you have a problem and you wake up the next day or even that afternoon or evening and there's a problem, please call your local doctor of optometry, get in and be seen, because we want to make sure we're discriminating between solar retinopathy problems and other problems. Sometimes things happen coincidentally, and if it happens at the same and you just say, "I'll just see about where this is going to be in two to three days," you may be missing a problem that needs to be addressed right away. So if there's any question about the vision, get in and see your local doctor, and if you don't have one, go to aoa.org. That's American Optometric Association.org, and there's a doctor locator right there, and it will show you who's in your community and who you can look up with their names and addresses and phone numbers. So it's a quick find.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's really useful to know. I'm really glad that I have someone who is an eyecare professional on here to talk about it. As a science educator, I can shout don't stare at the sun from the mountaintops, but it's always really useful to have someone who works in this all the time to vouch for this.

Ronald Benner: Well, it's one of those things that we find important. Vision is precious no matter what age you are, and with Americans, when we talk about fears, they talk about fears of cancer, but always in that number two or number three spot is fear of losing vision. In this case, like I said, with the solar retinopathy you never go completely blind, but you do lose that center vision. If you can't see faces, you can't recognize and read words, that's a problem. That's going to be a problem that's going to haunt you for life, and it's just not worth the risk. So we see it all the time, and unfortunately people who have that, like your friend, will tell you, "Man, I messed up." It was 15, 20, maybe 30 seconds of, wow, this is cool, and now a lifetime of pain for that 30 seconds of cool.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yep. I also really encourage people if they can get more eclipse glasses than you personally need because you never know when people around you are going to be going out. I frequently during partial eclipses see my neighbors and other people just staring up at the sun, so I'm always out there with a bag full of eclipse glasses just in case.

Ronald Benner: Yeah, I mean, honestly, last time around I had people tell me, "Well, I'm just going to put my fingers together and make a pinhole and look through that," and it's like, no, no, that's not good. Don't do that. Do it the right way. We want you to experience it. We want you to enjoy it. We want you to be able to tell your friends and family years to come that you witnessed that, but do it the right way. It's always better to be safe than to be sorry.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Have you observed a total solar eclipse before?

Ronald Benner: Yeah, I'm old, so we've had a few of them in my lifetime. It is pretty cool to see, and we all are tempted when we get to that annular when it's full to take them off. But unless you're in that direct path where we know it's going to be complete, 70 miles wide is all, unless you're in that, it's never a complete annular eclipse. Even the corona around it, even that small crescent around, there's enough thermal energy to actually damage that retina, so don't take that chance. If you're not in that pathway, leave the glasses on. It's, again, better to be safe than be sorry. If you don't know if you're in that 70-mile path, just don't take them off. Watch them with the glasses on. It still looks cool. It'll just disappear for a minute. You'll see a small halo. Some people described the little diamonds around that they can see at the complete eclipse, but go ahead and experience with the glasses on. Have the experience but be safe.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And for anyone who is wondering whether or not they're actually in the path of totality, we have an eclipse map on our website that's really helpful for this. You can go to planetary.org/eclipse. We have an app for that, so that'll allow you to figure that out. Do you have any plans for this upcoming eclipse?

Ronald Benner: I live in Montana, so we're not going to get hardly anything. It's not going to affect me, and honestly, the day that it happens I'm going to be in an airplane. So I probably won't get to experience it. We may or may not see it get dim and dark depending on what part of the country I'm flying over at that time.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That could be cool. I've heard some people have some really great accounts of looking out the window at partial and total solar eclipses from airplanes.

Ronald Benner: I'm looking forward to it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But either way, at least you won't be cursing the weather.

Ronald Benner: Yeah, maybe. Maybe. We'll see. But it comes back to again, man, go experience it. This is for many people a once in a lifetime in that region to see that full eclipse. Go experience it, but get the glasses. Make sure they're from a reputable dealer. Make sure that the ISO 12312-2 marking on them, and then take the kids out, but be careful with the kids. Explain to them, and if you can't trust them, watch it on TV. It's better to miss that little bit than to risk that damage.

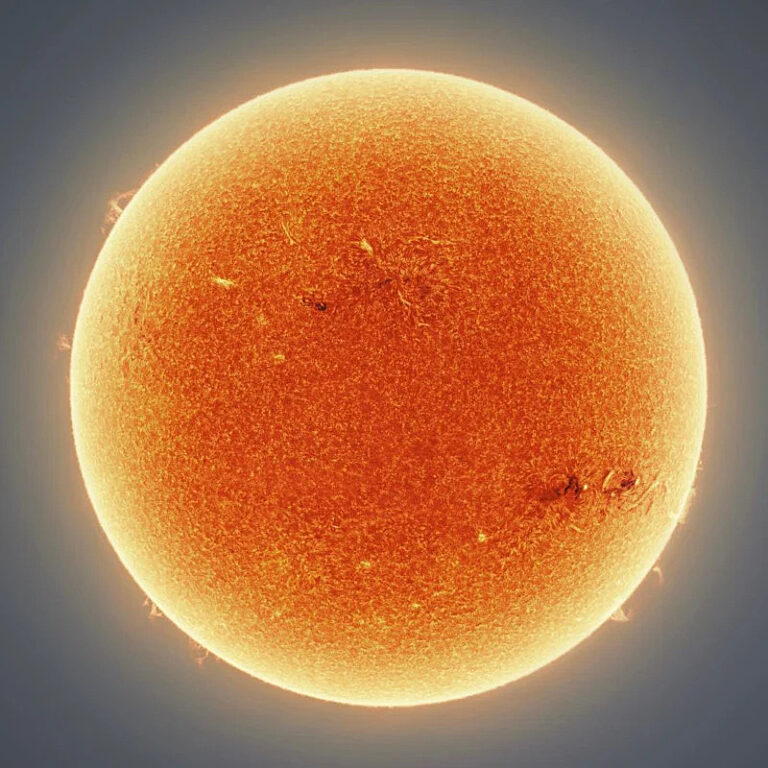

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks so much for helping share this information with everyone, Ron. Please, everyone, stay safe out there. Our next guest is Andrew McCarthy, the creator of Cosmic Background Photography and one of my personal favorite astrophotographers. His journey into the complex world of imaging space began when he viewed his first total solar eclipse in 2017. Since then, he's produced some of the highest resolution images of our sun ever taken from the surface of our planet. He's currently gearing up to capture the image of a lifetime, a super high resolution picture of the upcoming total solar eclipse. Whether you're hoping to view the eclipse through a telescope or through a camera, I'm sure his tips will help. Hi, Andrew.

Andrew McCarthy: Hi.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I've been such a fan of your astrophotography since I first started seeing it online. Your images of the sun and the International Space Station are absolutely startling.

Andrew McCarthy: Oh, thank you. I love capturing those photos, so it's always thrilling to hear people's reactions when they see them.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, your journey with telescopes and astrophotography is actually really tied to total solar eclipses. I hear that it was the summer of the 2017 total solar eclipse that you bought your first telescope and became interested in this. How did that moment impact you so deeply?

Andrew McCarthy: That's very true. My first telescope I bought right before the eclipse. I didn't bring it because I didn't know what I was doing with it yet, and I had to drive all the way across the country to see the eclipse. But seeing that total eclipse with my own eyes really kind of kicked off a lifestyle change for me where suddenly I felt like I had this mission to just share my love of space with the world, and it was kind of with that passion that led me down my astrophotography journey. Astronauts often talk about the overview effect they experience. They go up on the ISS, they're looking through the cupola, and they see the earth for the first time with no borders, nothing, and it gives them a unique perspective on our place in the universe, and I feel like I experienced maybe at some small degree of that when I saw the total eclipse. It wasn't looking at earth without borders, but when I saw the eclipse and I could see some of the inner planets around the sun and the corona, in that moment, I could really with my own eyes see the three-dimensional space of our solar system, like our little family, and I was seeing it in the context of the universe. That is such a profound thing to see with your own eyes. There's no photo that does it justice. I'm definitely going to try when I take the photo here in a month, but I've never experienced something that was so deeply profound, and it was only for like a minute and a half that I saw it. I wasn't quite in the center line of totality and it was a shorter eclipse. This one that we have coming up here is actually going to be significantly longer if you're in the center of the path. So I can only imagine just how much deeper this is going to impact some people out there. But it's one of the few experiences in my life that I can say definitely changed me and changed the trajectory of my life forever and only lasted for a minute.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's a really profound thing, that that one moment impacted you so deeply that it changed the arc of your life. But I think what you're saying about the physicality, the 3D nature of our solar system being something that you can really see and feel in that moment is so true because I've always known that the moon was a world all its own up there, but until that moment in 2017 that I saw it block out the sun, the physical presence of the moon as a rock never fully dawned on me. It was such a visceral and intense experience just seeing that, and I'm really glad that after all these years now you're going to be able to image it with everything you've learned since the first one.

Andrew McCarthy: Yeah, I'm looking forward to it because in 2017, like I said, I didn't bring the telescope. I did bring a DSLR. It was the original DSLR. It was something that I got forever ago secondhand. I didn't know how any of the settings worked on it. I had this cheap, like $20 tripod, set it up, took a photo with some cheap telephoto lens. That photo was one of my first astrophotos, and it was shot just point and shoot using basic settings, and I loved it. I was so happy with my photo. So that's, I think, a lesson to anybody that if you don't know anything about astrophotography, don't be afraid to try to take a photo of this eclipse because it could have a very profound impact on you just being able to document that moment, and you'll always look back on it fondly. But I would also say don't spend too much time playing around with your cameras because the visual experience is so important. One special thing about this upcoming eclipse is I'll hopefully be able to look at it through a telescope which there's, of course, no safe time to use a telescope that's unfiltered on the sun outside of during a total solar eclipse. So the moment of totality, you can take those solar filters off, the solar glasses off, and you can actually look at this thing with your naked eyes and see prominences dancing off the limb of the sun, see the depth of the corona. And then I'm going to have a lot of cameras going too, so hopefully I'll be able to resolve the corona at scale, how much of the sky it spans, and maybe even see some details on the moon as well since I plan on doing some HDR techniques to really bring this thing out. So I am so, so, so excited.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But you do bring up a very important point which is that imaging the sun, observing the sun is something that you have to do carefully, and we're all aware that staring at a partial solar eclipse or staring deeply into the sun can damage your eyes or even blind you, but what are the risks to your telescopes and camera equipment if you do this unsafely and unfiltered?

Andrew McCarthy: Well, I'll most likely find out on this trip. I've done some demonstrations on, I think I did a reel on my Instagram where a lot of people always ask me, "What happens without your solar filters when you're shooting the sun?" So I took them out and I took them out. I am a professional. Don't try this at home. So I took my telescope out of my observatory and I set it kind of in my backyard, and it was before I got landscaping on my backyard, so it was just dirt, there was nothing for it to hurt or catch on fire. I set my telescope up, pointed away from the sun, took the filters out of it, and then slewed it towards the sun, and then very carefully held up a stick of wood on the back end of that telescope, and the beam of light coming out of it was like a laser, and the piece of wood just instantly started smoking and burning like it was in a fire pit. So yeah, definitely just picture that on your eyeballs, and during a eclipse, what's interesting is the way our eyes actually evolved to detect pain and bright lights was because of the sun to kind of train you not to look at the sun. Well, the sun has to be at full brightness for that pain response. So when you're looking at the sun and it's partially eclipsed, you actually don't get the pain response, and because of that, these are so insanely dangerous because you look up in the sun and you're like, "Okay, it's not eclipsed yet, but it doesn't hurt my eyes so it's probably fine." Oh no, no. You are frying your retinas. Do not do that. You'll know when it's time to take the glasses off because it goes from feeling like an overcast day because the sun's only putting out 1% of the brightness right up to the edge of the totality. It'll go from feeling like that overcast day to just suddenly being nighttime, and it's a very obvious transition, and that point, you can take off the solar glasses and look at the spectacle with your naked eyes. There is a damage to your equipment as well because I will be having all these cameras set up. I'm going to be, I think, using eight cameras to document this event, and I'm going to very meticulously take off solar filters and lens caps right at the moment of totality, but I'm going to be shooting as long as possible to try to capture the diamond ring effect. That's when the sun starts to crest through the mountains and valleys on the moon, but is still partially occluded. So it's not like 1% visible. It's like 0.000001% visible. It's just through the tiniest cracks on the moon where the sun is peeking through, and that gives you this bright light on one edge of the moon and still darkness on the other to create a diamond ring type illusion. That only lasts a few seconds really. So I have a feeling I'm going to miss the mark on when to cover up some of my equipment, and I'm prepared to potentially sacrifice some cameras for this. I'm going to try my best not to because cameras are expensive, but I really want to get that diamond ring shot. So I fully plan on potentially having to write off some cameras because what will happen is the sun's focus light will focus on some of the pixels of that sensor and fry those pixels. They'll become oversaturated very quickly, then they'll overheat, and then those pixels will be dead. So when you go to take a photo again, you'll have some pixels on your camera not actually reading any light. They'll show up as hot or dead pixels. So it depends on the camera and the software how it interprets that signal from those dead pixels. But you could actually fry entire lines in your sensor as well, so you get these stripes that don't work right, or you could fry the sensor entirely to where the entire thing doesn't work. So yeah, it's a risk, definitely a risk. So be careful and better sacrifice a camera than your eyeballs. I'm only going to be looking at the eclipse dead center of totality through my telescope for the sake of not wanting to risk my eyesight.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Smart. It's funny you bring up the dead columns on the CCD because during my time using a telescope up at Lick Observatory, because people spend years using the same CCD chip on these telescopes, there are moments where one person accidentally oversaturates, just burns a whole line into the CCD, and forever after every research group has to avoid that specific section of the CCD when you're imaging. So this is something that can not only impact you but other people if you're using a communal telescope. But there are filters that we can put onto these telescopes to make it safe for solar observing even during partiality. What kind of filters do you recommend for this upcoming eclipse?

Andrew McCarthy: So there is a rating system for them, and forgive me, I don't know the number off the top of my head. You can google it, kind of like appropriate safety rating for solar glasses, and there's a certification process for them to tell you if they're safe or not. It's a fairly recent certification process, so even glasses purchased like five or six years ago might not have this certification associated with them. Essentially, it looks like a Mylar filter because it's silver, and if you hold it up to your eyes, you see nothing, like absolutely nothing. It's not like sunglasses where everything gets darker. You literally see nothing. And then if you look up at the sun, where the sun is, you will just see like a yellow or maybe a blue disc, depending on the filter. Some of them let in a little more blue light than others. So when you're looking through these filters, you should only see the sun, and if you only see the sun, that's probably a true solar filter, and you'll actually be able to see sun spots with it as well, sometimes with just your naked eyes. Oh, when I say naked eyes, I mean no telescope, no magnification, but still obviously with the solar filter. So yeah, make sure just for the safety of your eyes that it is a appropriately rated filter. You can buy them on Amazon. You can buy them pretty much every telescope shop, camera shop. They're everywhere.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll be right back with the rest of our eclipse tips after the short break.

Casey Dreier: This is Casey Dreier, the chief of space policy here at The Planetary Society, inviting you to join me, my colleagues, and other members of The Planetary Society this April 28th and 29th in Washington DC for our annual Day of Action. This is an opportunity for you to meet your members of Congress face-to-face and advocate for space science, for space exploration, and the search for life. Registration closes on April 15th so do not delay. I so much hope to see you there at our Day of Action in Washington DC this April 28th and 29th. Learn more at planetary.org/dayofaction.

Bill Nye: The total solar eclipse is almost here. Join me and The Planetary Society on April 7th and 8th for Eclipse-O-Rama 2024, our can't miss total solar eclipse camping festival in Fredericksburg, Texas. See this rare celestial event with us and experience a whopping four minutes and 24 seconds of totality. The next total solar eclipse like this won't be visible in North America until 2044, so don't miss this wonderful opportunity to experience the solar system as seen from Spaceship Earth. Get your Eclipse-O-Rama 2024 tickets today at eclipseorama2024.com.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: One of the most common types of filters that people use when solar observing is the hydrogen alpha filter. Is that the type of filter that you would recommend for these partial images?

Andrew McCarthy: Absolutely not. So a hydrogen alpha filter for astronomy is generally very broad. You'll find them, a very good one is maybe like seven nanometers wide. So if you visualize the electromagnetic spectrum, you look at the hydrogen alpha band, it's like 686.something. I don't remember the name for it now. That's the frequency of the electromagnetic emission and the filter covers kind this broad little section of it. Now, if you put that on a telescope, the sun would still be blinding you because you are blocking all but like a percent or two of visual light. But like I said earlier, even 1% of the sun's light getting through can still blind you. So yeah, a hydro alpha filter by itself is not safe. I do hydrogen alpha imaging with the sun, but it's actually a very, very precisely tuned system. It has a heat-tuned hydrogen alpha filter inside it that also has blocking filters and a barlow inside it that allows it to get that light down to a safe observing level. These are much more expensive than a simple hydrogen alpha filter. So yes, there is a way to do it, but it's not in a way that's going to be easy. It's not something you can slap onto the end of a DSLR and have it work. Every component from the telescope to the camera needs to be built around this specific filter because you do need to filter such a small amount of light. In fact, the one I use is about 0.5 angstroms wide. That's the band pass. An angstrom is a 10th of a nanometer. So it's about something like 20 times dimmer or something. I don't know. It's much, much, much fainter than just a regular hydrogen alpha filter.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Which is good. I want to make sure that even people who are comfortable with looking through a telescope with these common hydrogen alpha filters know that they still have to be safe. Imaging the sun and staring at the sun during eclipses is something you have to take very seriously, but when you actually get those images, they're absolutely spectacular. You have some really beautiful ways of stacking and combining images to get these closeup views of the sun. Do you have any types of software that you recommend for this kind of image processing?

Andrew McCarthy: Yeah, absolutely. So the technique is commonly called lucky imaging, and lucky imaging only really works where you're at very, very high magnifications because as we know, when you're looking through a very high-powered telescope, like let's say you're trying to look at Jupiter through a telescope, Jupiter is usually going to be wiggling around. It's going to be shaking. It's going to be kind of getting a little bit fuzzy and then a little bit sharp. That is the atmospheric seeing. It's layers within the atmosphere that have different refractive indexes because thinner air refracts air differently than thicker air, and as those layers mix, you end up with very inconsistent focus. Now, what the lucky imaging does is it analyzes images. If you say take a thousand images, it'll look at them and say, "Okay, these images have more contrast than these images." Images with higher contrast tend to be sharper, and it can do that by looking at the histogram of the image. So it can then sort those and say, "Let's only save 20% of these thousand images and we'll save those and stack them together." And then when you do that, you end up with a much more clean data wise image. It'll be a little bit sharper and it'll have almost no noise and it averages out the atmospheric noise. So there's a few different types of noise, one of them is atmospheric where you get that turbulence. You can average out that turbulence to a smooth gradient, and then you can use processing software to pinch that together. So the software I use to stack is called AutoStakkert!. It's the thing, it's pc. It really only works for smaller images, like I use a two megapixel sensor when I shoot my sun photos. What makes them huge is I build them as a mosaic. I shoot maybe two to 3,000 photos in a little tiny square of the sun, and then I move the telescope a little bit and do that again, and then I repeat that process until I cover the entire solar disc which is usually like maybe 40 to 50 panels. That's why if you ever see my work you'd say, "I don't understand. How do you take 150,000 photos to make one photo?" It's because you almost have to think of the photo in three dimensions where I'm shooting from left to right, top to bottom, and then vertically with stacking like 3,000 photos, and when you think of it like that, the numbers can get very high very quickly. So yes, I do take a lot of photos for some of these shots, and I plan on doing that during the eclipse as well to get a very, very high resolution shot of the final product.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, it's a meticulous way of doing it, but when you actually get the images out at the end, they are so beautiful and so crisp. But as you point out, the atmosphere can cause objects within your view of your telescope to wiggle around, and even just the motion of the earth, moon, and sun over time is going to change the position of the sun and this eclipse on the sky. So what are some things that people can do to make sure that their telescope and cameras and other instruments are fully focused on the sun during this so that they're not constantly having to move things around?

Andrew McCarthy: Well, having an equatorial tracking mount would probably be the first step. An equatorial tracking mount does exactly what you described. It reverses earth's motion, and you can adjust the speed of most of them to track based on lunar or solar movement which is of course slightly different. The moon moves much faster than the sun. So if you're staying locked on the sun, you actually probably don't have to adjust for its drift. In fact, you're more likely to have an error from not aligning it properly with polar coordinates called polar aligning than you are to have drift from the sun just because it does take so long for the sun to drift positions relative to sidereal rate which is the rate the stars move across the sky. So I wouldn't worry too much about setting those tracking rates just so long as you get a very good polar alignment on your equatorial mount. Now if you have a wide enough field of view, you probably don't have to worry about that too much. In 2017, I shot the eclipse with a 300 millimeter lens, and that was more than enough focal length. The diameter of the sun was maybe a quarter of the height of the image with my crop sensor. So it was small, but that was okay because the corona fills that image really nicely. I didn't use any kind of tracking. I just had it on a tripod, and I just, in the moment of totality, just made sure it was centered which just took a quick adjustment on the tripod. During that minute and a half or however long that eclipse was, the sun did not move out of frame enough due to the Earth's motion for me to worry about it. It drifted slightly, but not a lot. I believe it moves, was it 15 degrees per hour, and it's about a half a degree wide. So visualize it, it moves about 30 times its length in an hour, so maybe double its length in a minute. So throughout the course of a four-minute-long eclipse, you may have to adjust it a little bit at a 300 millimeter lens. So just keep an eye on it. Check on it halfway through and see how it's doing, but try to experience it visually, of course.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Are there any other pieces of gear that you recommend people purchase prior to trying to attempt any of this? Because we've gone through telescopes and filters and mounting. Anything else you recommend?

Andrew McCarthy: I would recommend not overcomplicating it because if you're heading to some event, it's going to be stressful, you're not going to have a lot of time to worry about it. So I would only use what you know. If you know your DSLR like the back of your hand and know how to use it, I wouldn't stress about adding some kind of complicated bracketing system or anything beyond what you feel like you can comfortably do. You're not going to be thinking correctly when you have to rush out these shots while simultaneously having the most incredible visual experience of your life. So keep it simple. I do recommend getting an intervalometer. If you're shooting at a long focal length, an intervalometer keeps you from touching your camera which shakes it. If you're trying to take a longer exposure especially, you don't want that camera to shake it all. It'll also allow you to basically let the shutter just keep working. Keep taking photos throughout that three, four minutes, however long you have, and then you can spend more time just looking at the eclipse and less time worrying about your equipment. So if there's one piece of gear to get, it's an intervalometer, but I just, I recommend practicing with it beforehand so you don't have to stress about using it in the moment.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Because this is really a moment that people are going to want to focus on. You really are going to want to have it in like a set- it-and-forget-it mode so you don't have to be staring at your camera the whole time while you are experiencing this potentially life-changing moment. What are your plans for the upcoming April 8th eclipse? Do you know where you're going yet?

Andrew McCarthy: I don't know where I'm going because I'm going to be shooting it at such a long focal length, atmospheric seeing will play a huge role in how good my final image is. So in that forecast, it's very hard to predict. In fact, you can give a rough forecast maybe a day before, like a day in advance of that event. So on April 7th, I will know where I'm going to be going, but until then I don't. It will probably be somewhere in Texas. Texas is known for better seeing conditions due to the Gulf of Mexico stabilizing that upper atmosphere, and that is what I hope to be taking advantage of. But cloud cover, historically, there is about 50% chance of clouds, so my final location could be anywhere. I'm going to look at that forecast, look at clouds, look at seeing, and then make my best guess based on there. I have a few spots reserved. I have a few cancelable hotels booked. Obviously, as you can see, I'm just very, very, very invested in making sure I see this event. So I'm going to find a way no matter what.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Plans within plans, and I hope that the weather treats you and everybody else trying to see this thing kindly because it's not like a moment like this comes by every day. People in the United States are going to have to wait at least another 20 years plus in order to see anything like this again, unless they want to go somewhere else in the world. So I know there are going to be some people that are absolutely devastated by the weather, but we can't control everything. So I'm glad you have contingencies.

Andrew McCarthy: I certainly do. Yep.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Do you have any other bits of advice for people who are just beginning on their astrophotography journey?

Andrew McCarthy: Absolutely. The biggest one I can say is just stick with it. Don't invest in new equipment if you haven't mastered existing equipment. It's a challenge to give advice to people starting out because I think about what I did and my journey. My journey was particularly hard in astrophotography because I didn't know how to ask for help, and the first maybe two years I did this, I didn't know what I was doing. I was buying equipment and I didn't know how to use it, and my images were terrible, and I kind of Frankensteined together an astrophotography rig in my backyard because I didn't know which telescopes were ideal for astrophotography. I was just like, "Oh, there must be just one kind of telescope and the bigger, the better." So I got too big of telescope for my little mount, and my pictures were just terrible. Meanwhile, I have a little tiny 70 millimeter telescope that produces incredible images of galaxies and nebulas that I never thought would be possible with anything short of a space telescope. So don't get discouraged. It's a hard, hard, hard journey. There's a huge learning curve to it. Ask for help. Join forums. There's a lot of people out there that just love talking about this, myself included. So don't be afraid to ask for help. A lot of times, the advice might not be what you want because people are looking for a way to make this easy, and it's just not easy. It's a difficult hobby to get into, but it's more feasible than you think, and usually the limit is not your equipment, your telescope, your camera. Usually the limit is yourself and how far you're pushing your own experience with that equipment. So do your best to master your equipment and you'll produce some incredible images.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: As with anything, you're never going to get it right the first time, and we just have to be kind to ourselves because I look at your first images and how far you have come is absolutely startling in the last seven years. The first ones were beautiful, but where you're at now, they do look as if you would need some kind of space telescope in order to accomplish them. So I think there's a lot of hope for people who are just starting out. If you can accomplish it, they can too.

Andrew McCarthy: I believe that space is truly for everybody. I am not special. I'm a college dropout. I didn't study this stuff. I had all these ambitions in my life for all kinds of different things and started this on a whim and didn't realize just how much it would take over my life, and now I'm a professional astrophotographer. I'm talking with scientists regularly and making contributions to astronomy, and I'm just some guy. I don't have a particularly fantastic set up for this, or at least I didn't when I started. I'm competing with streetlights, so it's not like my backyard's really that dark. It's darker than it was when I was doing it in Sacramento. But people have a tendency, I think, to look at their circumstances and say, "I can't do this with my circumstances," but I can tell you that's not true. There's many people out there that produce better images than me with circumstances much harder than me, including tighter budgets. Maybe countries where it's more difficult to source telescopes and cameras, maybe they have not only a full-time job but a family and children they're juggling, and they produce incredible images because they just put in the time when they can and they chip away at this passionately. So your circumstances might be difficult, but don't let it hold you back from pursuing something that you're genuinely interested in.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well said. Space is for everyone, and I want to make everyone feel empowered to chase their space dreams, whether or not it's becoming an astrophotographer or just learning more about the universe around us. We live in a beautiful place in a beautiful time, and everyone deserves to understand what a beautiful world we live on and the beauty of the universe around us, and I think your images do a really great job of capturing that and sharing it with people. I'll leave a link for your website on this episode page for Planetary Radio. You've got some really useful blogs on there, as well as some really cool merchandise made out of your images which I know I've always wanted to purchase, so I'll share that with everyone. But thanks for sharing your expertise with us. I hope that this starts people on their astrophotography journey and hopefully prevents people from accidentally damaging their telescopes, cameras, and eyes during this event because this is something we want to remember fondly for the rest of our lives.

Andrew McCarthy: Absolutely. If there's one thing you heard from me this entire conversation, let it be don't stare at the sun without protection. No matter how safe you think it is, it's just not a good idea.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yep. Well, I hope the weather treats you well, and I'm looking forward to seeing what you capture on April 8th.

Andrew McCarthy: Well, thank you so much.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know that there's so much to prep before the eclipse for everyone who's going to be trying to observe, but we're definitely here to help. All of the resources mentioned in this show and our expansive collection of eclipse articles will be linked on the webpage for this episode of Planetary Radio. You'll find that at planetary.org/radio. Two things that you might want to look for are our safety guide for viewing and a video on how to begin your astrophotography journey with a DSLR camera. We're also working on an upcoming article that highlights organizations that are working to make the eclipse accessible to people with low or no vision. Everyone deserves to enjoy the eclipse. Now let's check in with Dr. Bruce Betts, our chief scientist for What's Up. Hey, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hello, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We are so close to this total solar eclipse, I can almost taste it.

Bruce Betts: That's the one thing that as far as I know does not happen during a total solar eclipse.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Taste?

Bruce Betts: Tasting it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Hmm.

Bruce Betts: But I look forward to hearing whether you do. Now have you seen one?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, just the one in 2017.

Bruce Betts: It was pretty impressive.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It was such a formative moment in my life. There are those moments where you know that you're passionate about something, but then you go through a life experience that just makes you feel like I am on the right path, and I remember thinking that staring up at the eclipse in 2017.

Bruce Betts: Wow. Cool. Like, this is definitely what I want to do with the rest of my life, and I hope by the next eclipse I'm in a better place and a career path that really makes me feel I did the right thing. And here we are. Winner. Good job.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But I encourage everyone to make their eclipse wish. Unfortunately in the United States and Mexico and Canada, we're going to have to wait over another 20 years before we see one of these again.

Bruce Betts: Oh, unless you road trip.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh man. You want to go on a trip with me somewhere in the world, Bruce? Let's go watch more eclipses.

Bruce Betts: No. Oh, sorry. Yes, of course, I would love that, Sarah. It would be great.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Bruce doesn't want to travel with me.

Bruce Betts: We already, that was our strange beginning working with you was traveling together in Florida to not watch a rocket launch.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's true. You should see what Bruce is like when he hasn't had coffee at 3:00 AM on the way to KSC.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. Especially when he finds out that there's coffee that Sarah's locked in the trunk.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I really didn't think that one through. But get your coffee ready for the eclipse or for whatever rocket launch you're going to, you're going to need it.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. Well, you can always wake yourself up by staring at the sun. Isn't that right?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I was really happy to have Ronald Benner to talk about this because I mean, everyone says you shouldn't stare at the sun during solar eclipses, right? Or just in general, don't stare at the sun. But there was an actual incident in my formative years when I was in high school.

Bruce Betts: Oh my gosh.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We were on a Girl Scout trip. We were going to go see this partial solar eclipse. We had all of our safety gear. We had had the talk with everyone, don't stare at the sun, and then one of my really, really good friends was like, "Well, what could possibly happen?" She stared straight at that partial solar eclipse for quite a while and ended up damaging her retina. She gave herself retinal burns, and I had to help her with her homework for a month after that because she literally could not read.

Bruce Betts: Wow. That is a dark reminder to not do something stupid like staring at the sun.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, don't do it. Thankfully, her eyes recovered and I didn't have to help her with her homework forever after. But man, seriously, don't stare at the sun, y'all. Don't stare at the sun.

Bruce Betts: Well, I love a story with a happy ending. It's a warning story with a happy ending, but not all will have happy endings. So no staring at the sun except during totality, in which case you're really mostly staring at the moon with the sun around it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But these are some nuances that have to be taught to people through education which is why we're trying so hard to make sure that people hear this message. But I'm sure that there are a lot of young people out there who are also going to be observing the eclipse, and thankfully you've written this really beautiful book for young people who are trying to learn more about eclipses called Casting Shadows. Would you like to share a little bit more about that?

Bruce Betts: Sure. It's a book that's directed at elementary school, age seven to 10 age group type kids, but really is good for anyone, including adults if you want some pretty pictures and a quick review of eclipses and what they are and why they occur and both lunar and solar eclipses. And so, I don't know. I like it. It's pretty.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Very eloquent, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: The good news is I had editors so it's much more eloquent than I just was.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: See, this is why teamwork makes the dream work. But I know I say this every single episode that it really helps Planetary Radio anytime someone leaves us a review or a rating, and I know it would help a lot of people find your book, Casting Shadows, if people could leave ratings for your book.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, on Amazon or elsewhere, that'd be great. So if you do pick up Casting Shadows, a product of The Planetary Society in partnership with Learner Books, then please go ahead and leave a review, hopefully positive, but review nonetheless.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'll leave you a review, Bruce. I'll leave you a review.

Bruce Betts: Of the book, not me, right?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Bruce is kind of weird, but this book is excellent. Love, Sarah.

Bruce Betts: That works for me.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, before we move on to our random space fact, I wanted to share a poem that one of our members sent in about a recent episode. It was our episode called Tales of Totality that was about eclipse chasing with Jim Bell, and this is a poem by Jean Lewin says, "Why Chase eclipses, you may ask, I'll not keep you in the dark. You become a part of syzygy, orbs aligning in their arc. On average every 18 months, the moon centered perfectly, blocking out the sun's rays in the path of totality. You can't experience this anywhere, you have to be in the right place. It moves around our Planet Earth on a geometric pace, and this orbital alignment will leave viewers in awe all four minutes in darkness with the crowds wishing for more."

Bruce Betts: Oh, cool. Very nice.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I can't believe we're going to get such a long totality this time. I'm excited because the first one, it felt like I looked up, it blew my mind, and then it was gone.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, I forgot, that was a couple, two minutes, something.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I want to say two minutes, yeah. So almost four minutes is going to be nice.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, I mean, if it's not cloudy.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Don't curse us, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Okay. I still say, as awesome as I am, I'm not powerful enough to affect the clouds and in what they do on the day of the eclipse and the weather.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I once had a lady yell at me because I couldn't reschedule the sunset at an observatory.

Bruce Betts: I assume now you can.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yes, clearly, I am a wizard and I could do whatever I want with the celestial orbs moving around us.

Bruce Betts: Where's the hat and the robe? Oh, and the wand, or is that... Not a staff, you went with the staff. Okay.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, I'm definitely a staves kind of girl.

Bruce Betts: Ooh, stave, even better.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: All right, what is our random space fact this week?

Bruce Betts: Random space fact.

Bruce Betts: This week we're headed to Pluto and a little understanding, if you weren't aware, of why it was a planet for so long, was thought to be a planet. People thought based upon it's really hard, not surprisingly, to calculate the mass of something really, really, really far away if you don't have something to help you, like a moon where you can start using physics to figure it out. So after it was discovered, it was thought for almost 50 years that Pluto was as massive as Mars and in some early on as massive as Earth, so like an actual planet. And then with better observations and shortly thereafter with the discovery of Charon, the moon, calculations were made and found that instead of 1/10th of the earth mass, it's more like rounding off 1/500th the earth mass. So a little less seeming like the other planets. So anyway, that's your random space fact. I thought it was interesting to keep track of one of the reasons it seemed more like the rest of the planets for much of its early history.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I love Pluto so much. Let's take this out.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody, go out there, look up at the night sky, and think about your favorite kind of cheese. Thank you and goodnight.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with even more space science and exploration. If you love the show, you can get Planetary Radio T-shirts at planetary.org/shop, along with lots of other cool spacey merchandise, including safe eclipse glasses and Eclipse-O-Rama gear. Help others discover the passion, beauty, and joy of space science and exploration by leaving your review and a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day, but helps other curious minds find their place in space through Planetary Radio. You can also send us your space thoughts, questions, and poetry at our email, at [email protected], or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in our Planetary Radio space in our member community app. Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California and is made possible by our members who are living their best life in their eclipse era. You can join us and help share the beauty of our place in space at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor, Josh Doyle composed our theme which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. And until next week, don't stare at the sun and ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth