Planetary Radio • Jan 29, 2025

The Edward Stone Voyager Exploration Trail

On This Episode

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

Jack Kiraly

Director of Government Relations for The Planetary Society

Laurie Leshin

Jet Propulsion Lab Director and Planetary Scientist

Charles Elachi

Director Emeritus of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Glenn Cunningham

Retired Engineer for NASA

Linda Spilker

Voyager Mission Project Scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Suzanne Dodd

Director for the Interplanetary Network at JPL and Project Manager for the Voyager Interstellar Mission

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

Also featured:

- Janet Stone, Daughter of Ed Stone

- Susan Stone, Daughter of Ed Stone

This week on Planetary Radio, we celebrate the enduring legacy of Ed Stone, the longtime project scientist for NASA’s Voyager mission and former director of JPL. Mat Kaplan, senior communications advisor at The Planetary Society, takes us to the unveiling of the Dr. Edward Stone Voyager Exploration Trail at JPL, where we hear from past and present JPL leaders, Voyager mission team members, and Ed Stone’s family. Plus, we kick off the episode with the much-anticipated launch of Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket and wrap up with What’s Up, as Bruce Betts explores the rare planetary configuration that made Voyager’s Grand Tour possible.

Tribute to Ed Stone

Ed Stone, the former director of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the longtime project scientist of the Voyager mission, passed away in early June 2024. Here are some of the memories shared with us by Ed’s friends and colleagues.

Mat Kaplan, Planetary Society Senior Communications Advisor

Jim Bell, Past President (2008-2020), Board of Directors of The Planetary Society

Eberhard Mobius, Professor Emeritus at the University of New Hampshire Space Science Center and Department of Physics and Astronomy

Alan Cummings, Senior Research Scientist at Caltech

Allan Labrador, Staff Scientist, Caltech Space Radiation Laboratory

Related Links

- The Planetary Society remembers Ed Stone

- The Stories Behind the Voyager Mission: Ed Stone

- NASA JPL Unveils the Dr. Edward Stone Exploration Trail

- Edward Stone Voyager Exploration Trail | NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL)

- NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory unscathed by Eaton fire, but not its workforce - Los Angeles Times

- The Caltech and JPL Disaster Relief Fund - Advancement and Alumni Relations

- Planetary Radio: Ed Stone and Forty Years of Voyager in Space | The Planetary Society

- Planetary Radio: Looking back on Voyager's 45th Anniversary | The Planetary Society

- Planetary Radio: Voyager 1 at the Edge of the Solar System, With Ed Stone

- Planetary Radio: A big year for heliophysics and Parker Solar Probe

- The Voyager missions | The Planetary Society

- The best space pictures from the Voyager 1 and 2 missions

- Tour NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- A Pale Blue Dot | The Planetary Society

- Europa Clipper, a mission to Jupiter's icy moon - The Planetary Society

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

Let's take a hike on the Dr. Edward Stone Memorial Trail this week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our Solar System and beyond. Some people have lasting impact on the space science community long after they're gone. Like Ed Stone, he was the director of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory for a decade, and the longtime project scientist of the beloved Voyager mission.

Ed Stone passed away last year, but his legacy lives on in the missions he championed and the lives he touched. This week, Mat Kaplan, our Chief Communications Officer, shares the unveiling of the Dr. Edward Stone Exploration Trail at JPL, which honors his career and the Voyager mission. You'll hear from past and present directors of JPL, leaders on the Voyager Mission team and members of Ed Stone's family. But we begin with the much-anticipated launch of Blue Origin's New Glenn Rocket.

Eyes up SpaceX. A new orbital commercial rocket has entered the chat. And stick around for What's Up? with Dr. Bruce Betts as we talk about the rare planetary configuration that allowed Voyager to tour our solar system in the 1970s and '80s.

If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure that you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it.

As promised, we begin with a launch. Blue Origin's New Glenn Rocket achieved orbit on its first attempt on January 16th, 2025. It took off from Cape Canaveral Space Force Station marking a significant milestone for the company. The NG-1 launch was the first from Space Launch Complex 36 in 20 years. While the primary goal of reaching orbit was accomplished, the booster was lost during the descent. Still, the success of New Glenn is a major step for Blue Origin, a commercial space company that had previously only launched its suborbital New Shepard vehicle. Our senior communications advisor and the creator of Planetary Radio, Mat Kaplan joins me now to discuss. Hey, Mat, thanks for joining me.

Mat Kaplan: Always a pleasure, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And in a little bit we're going to be hearing more about your adventure to JPL for the dedication of the Voyager Trail, but before we get into that, there is a moment in commercial space history that we've all been looking forward to for quite a while. The launch of New Glenn Rocket.

Mat Kaplan: I'm imagining no one has looked forward to this more or maybe longer than Jeff Bezos, who of course is the main power behind Blue Origin. And it has been years and this rocket is years over date, but they pulled it off. January 16th, a reasonably successful first launch, got payload into orbit even though they lost the booster, which had this great name. So You're Telling Me There's A Chance, that's the name.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I didn't know they named that. That's so funny.

Mat Kaplan: Pretty clever. But they considered it a success and I'm inclined to agree. It's a darn big rocket.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, it didn't really occur to me how large this rocket was until I went to go actually visit the Blue Origin Rocket Factory.

Mat Kaplan: Yes. I was so envious even though I was there on the Cape while you were doing your tour.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, and I'm sure listeners of the show have heard part of this story because we had a large number of people from our team that were in Florida to go see the launch of the Artemis I Rocket, which didn't actually launch, but in the days after Bruce Betts and I actually got to go to this Blue Origin rocket factory. And in the Rotunda they have a New Shepard Rocket and right next to it they have this little display of the size of New Shepard versus their dreams for what New Glenn was going to be like. And after seeing all those giant rocket parts down on the factory floor, it kind of clicked with me how large this rocket is in comparison to what they had tried before.

Mat Kaplan: And in comparison even to a lot of the other rockets, the Atlases, the Deltas, and a lot of the other boosters from around the world. It occurred to me while I was looking into all of this, if it weren't for the SpaceX Super Heavy slash Starship, everybody would be just all over the New Glenn because it is huge at over 320 feet. And a 7-meter fairing, which is gigantic, but it has to now compete with Super Heavy-Starship, which is of course substantially larger. I mean a 9-meter fairing among other things, but still very impressive. And when you compare it to the Falcon 9, which as I said, that's really where its main competition is as Blue Origin sees it. It is quite a large rocket, and it's capable getting a lot of stuff up to space. And it has a lot of payloads waiting for it to be fully operational.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, they've been waiting quite a while because it took a little bit to get this rocket going, but it's wonderful to know that they already have business so they can keep going with this rocket and see what its capabilities actually are. We've had SpaceX kind of monopolizing for better or worse this commercial space launch space because they were the only ones capable of doing it. And in this time they've succeeded hundreds of times in launching things into orbit. But now we have a competitor, which means not only will they have to jockey against each other for being the best launch system, but also it means there's more opportunity for even more people to launch things into space. And we're going to need those rockets in this coming space age.

Mat Kaplan: Yes, I think you're right there, and the need is, you can already see it when you look at the launch manifest for New Glenn. The very next launch, which is still a test launch, is going to carry components that Blue Origin is working on for their Human Landing System, Human Lander that's going to carry astronauts to the moon someday as contracted by NASA. And it's going to carry life support systems that they want to test out on orbit, and then the one after that will be starting the ESCAPADE twin spacecraft on their way to Mars. So there's a whole lot of stuff coming up and a lot of need for these new launch vehicles.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I've been looking forward to ESCAPADE, but probably just because so much of it was built at my alma mater, UC Berkeley, their Blue and Gold. This is a wonderful moment and a good time to remember that Blue Origin was the company that managed to land first successfully land or a rocket on earth after launching and then coming back. Of course SpaceX managed to accomplish it again with an orbital rocket just a month later. But it's really wonderful seeing them have this moment where they finally succeeded and launched this rocket because it's been a long time coming.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely. And that New Shepard, I don't really know what the future is for New Shepard, whether they're going to continue those orbital flights above the von Karman line, but I hadn't really thought about that. That you were absolutely right, first rocket to make it past that von Karman line with the arbitrary edge of space and come back down and land on its tail in one very safe piece.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I remember that night someone sitting next to me who didn't know what was going on but was watching this live stream with all of us turned around and was like, "Are they running that video backwards?" Nope. They're just making history.

Mat Kaplan: Science fiction stuff, man. That's stuff I grew up on.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So in a moment we're going to be hearing your trip to JPL and all of the wonderful things that happened there, but listeners of the show in the last few weeks will know that we had to postpone this segment for a little bit because we were impacted by the Eaton Fires in this area. And the people over at JPL have had some significant losses because of this fire. So before we go into this segment, I wanted to take a moment to talk about that and the difficulty that the people over at JPL are facing right now.

Mat Kaplan:

It's absolutely awful. And of course the number of people affected who are members of the JPL staff, which is now about 5,500 people after the recent reductions in staff. So real double whammy for them, that's a tiny fraction of everyone who has been displaced or affected by the Eaton Fire. The fire that destroyed the community of Altadena and touched so many others nearby. But over 200 staff members at JPL lost their homes, which is just so tragic and mind-boggling.

I guess the good news, it is good news is that I've been told by the folks at JPL, no fire damage on the JPL campus. Only wind damage because of the winds were to a hundred miles an hour during that horrible, horrible 24 hours or so. But our hearts go out to all of those people who now are looking for a home as they try to advance our plans in space exploration.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It was really difficult watching that go down over the course of a week because it wasn't just JPL that was under threat, it was also Griffith Observatory, it was also Mount Wilson. It was so many of the beloved space science institutions in our area. And I'm really glad to report that they all made it through the fire, but the space science community in this area is really hurting as we try to figure out where people are going to find their new homes and how we're going to get back to our new normal. So I'm really glad that their institutions like Caltech that are organizing fundraisers specifically to help this community.

Mat Kaplan: This is so great. I had heard about this, but you sent me the link, and I'm sure you're going to share it on this week's episode page. It is a great way to support these people from JPL who are now in dire straits, and it is really wonderful to see Caltech reaching out and giving us the opportunity to help out this way.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, if it's any indication, I know our team is very small and a few people on our team did lose their homes. And seeing the outpouring of love that we've gotten from the space community and everyone trying to bolster each other, I know that there are so many people out there that want to help support the people over at JPL because they've made so many of the missions that we care so deeply about. So I will, I'll share that link online, and if there's any way that you can help or reach out to the people in your life that have been impacted by these fires. I know they would really appreciate hearing from you and having that support.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, here, here.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well thank you for all of this, Mat, and I'm excited to hear the rest of your journey to JPL. And I'm so glad that the Voyager Trail is still there.

Mat Kaplan: It is still there. And folks, if you get a chance to take a tour of JPL, go there during the open house, you can have your shot, and we'll have information about that too. But, Sarah, as always, great talking to you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Great talking to you too, Mat. Thank you so much. In December 2024, Mat was invited to attend a very special event at NASA's Jet Propulsion Lab, which is not that far away from our headquarters here in Pasadena, California. The devastating Eaton Fire that affected our area caused us to delay sharing this with you, but with JPL's encouragement and the happy news that the facility is still standing, we present you now with the unveiling of the Dr. Ed Stone Exploration Trail.

Mat Kaplan:

Planetary science and exploration are still relatively new fields, but they've been around long enough for us to suffer the loss of many pioneers. We lost one of the greatest when Dr. Edward Stone passed away in June of 2024. It was the flight of Sputnik 1 in 1957 that turned this budding physicist toward planetary science. Ed was the only project scientist on the Voyager Mission for 50 years. His decade as director of the Jet Propulsion Lab began in the middle of that service.

I interviewed him for Planetary Radio several times. I always left these sessions with the same admiration for Ed that thousands of others shared. So I was delighted when I received an invitation in December for the dedication of the Edward Stone Voyager Trail at JPL. I wasn't alone. Many of Ed's colleagues, friends and family members also gathered on the lab's beautiful mall for a brief ceremony. They included Planetary Society co-founder and former leader of Mars Exploration at JPL, Louis Friedman.

Later in our coverage, you'll hear me walk a bit of the trail with two old and very distinguished friends, but we'll start with a relatively new friend representing The Planetary Society with me that morning was our great director of government relations, Jack Kiraly. I wish this was your first trip to JPL, but I guess you're still a newbie, Jack?

Jack Kiraly: Yeah, it's only my second time on labs, so it's really exciting to be here and for such a momentous occasion.

Mat Kaplan: And to be surrounded by such an amazing crowd.

Jack Kiraly: I mean, I think I quipped to you when we got here, this really is the who's who of planetary science and space exploration. It's really exciting to be here with the luminaries of this field.

Mat Kaplan: And these are the people who are doing the work that you do your work on behalf of in a sense, right?

Jack Kiraly:

Yes, absolutely. I mean, this is what we strive for, right? With these amazing missions, whether it's Voyager, the tour through the Solar System, or Cassini, Galileo, Magellan, these amazing missions that have a legacy here on lab and across the country. It's really an honor of a lifetime for me to be able to advocate for more of these in the future so that we can continue to expand our knowledge of the solar system and worlds beyond.

I remember being in elementary school and seeing the first, well, humanity's only images [inaudible 00:13:55] of Uranus and Neptune thanks to the work of Dr. Stone. And being some of those early images and memories I have of what humanity is capable of in space. So to be here to be part of this dedication is really kind of a homecoming I think for a lot of people. But this is really empowering for me and is going to be some energy that I'll bring back when I return to DC next week to talk to legislators and staff and folks part of the incoming administration to advance science.

Mat Kaplan: Laurie Leshin has led JPL since May of 2022, the first woman to take on that responsibility. She was a young researcher during Ed Stone's time as director, and she was one of several speakers who honored Ed.

Laurie Leshin:

It's a special moment for the laboratory to celebrate and commemorate the incredible life and legacy of Ed Stone with the official unveiling of the Ed Stone Voyager Exploration Trail. So today we'll get to travel a path similar to the Twin Voyager spacecraft. Don't worry, it is not billions of miles long, and we'll get to experience the mission's exciting milestones, launch dates, encounters with the giant planets and transition to interstellar space.

And interspersed with the spacecraft accomplishments as it was in real life, Ed's achievements are marked along the path of the spacecraft. Won't spoil them all for you, I'm not going to give you the full list and there are many. But a few are being awarded the National Medal of Science, receiving the Carl Sagan Memorial Award. And we know one of Ed's proudest achievements having a middle school in his hometown of Burlington, Iowa named in his honor.

So when I speak about JPL's storied history, I often talk about the pioneers who first launched our great nation into space. From the JPL founders to the human computers who calculated the early rocket and mission trajectories by hand. Ed was also a pioneer whose achievements stand shoulder to shoulder with those earliest JPLers. And speaking of shoulders, as a planetary scientist myself, I can definitely say that we all stand on Ed's shoulders as we look to an exciting future in deep space exploration. Much of which, and this is really true, much of which was built on the extraordinary success and legacy of Voyager. It set the tone not only scientifically, but in terms of boldness for so many of the deep space missions that we fly today.

Over the course of his career at Caltech and JPL, Ed did nothing short of transform humanity's understanding of our Solar System and beyond.

He has the distinction of being one of the few scientists to be involved with the mission that came closest to the Sun, NASA's Parker Solar Probe and the one that has traveled farthest from it, Voyager. These missions and many others that Ed supported have literally rewritten the textbooks and impacted people's view of themselves as travelers on the pale blue dot we call Earth.

In 1991, about two years after Voyager completed its incredible grand tour with a spectacular visit to Neptune, and by the way, Voyager 2 is still the only spacecraft to have visited Uranus and Neptune. So after in 1991, Ed was named the seventh director of JPL. During his decade-long tenure, he oversaw more than two dozen successful missions and instruments, many of which represented the next giant leaps for planetary science, for NASA's Earth Observing System and for astrophysics. These included such missions as Mars Pathfinder with its memorable Mars Rover Sojourner, the first wheeled vehicle on another planet and the foundation of today's extraordinary series of Mars Rovers.

Also, of course, a co-star of the movie The Martian with Matt Damon. Also, there was the prime mission of Galileo to Jupiter, first mission to orbit Jupiter and the development and launch of the collaborative NASA ESA Cassini-Huygens mission to Saturn. Both of these missions further explored the incredible scientific questions raised by Voyager and paved the way for missions flying today like our own Europa Clipper honored over there on the big board, which is doing great by the way, Europa Clipper flying incredibly well.

So Ed was director at a time of change for NASA. Feels familiar. He restructured several missions so they could fly under stringent cost constraints brought on by NASA's focus on faster, better, cheaper development. Despite cuts to NASA's budget at the time, JPL reached its highest flight rate to date during Ed's time as director. He oversaw initiatives that reformed JPL's proposal process, flight project practices and design principles that enabled more missions to be formulated and flown while at the same time improving quality.

He established the groundbreaking concurrent engineering group or Team X as we call it, to rapidly develop mission and spacecraft concepts and cost them. This is a vital capability to support the proposal process and produce less expensive missions. And that idea of Team X has now been duplicated at almost every other NASA center and lots of other organizations as well.

Speaking personally, I can very much relate to some of the challenges that Ed faced as director. During his time we underwent a significant downsizing of the laboratory, for example, and Ed even oversaw a couple of very difficult mission failures, one of which I was a young team member on actually standing right about there live on CNN when we did not successfully land on Mars. Can very much relate to some of the challenges that he faced during his tenure, but through all of it, through the highs and the lows, he continued to serve as project scientists for Voyager 50 years. And that I believe is an accomplishment we will never see again.

It is perhaps his crowning achievement among so many monumental successes that made up his life's work, and the impact of Voyager is continuing. I don't know if you all saw maybe three weeks ago in the New York Times, they covered a new nature paper led by JPLers, JPL scientists that reinterpreted Voyager's observations of the unusually oblique and off-centered magnetic field at Uranus. So we flew by, we saw Uranus's magnetic field. It's very weird and that has been an open question since that time. And this new paper reinterpreted in the context of rare solar wind conditions that were present right at the time of the flyby. So 40 years later, we're still trying to understand what Voyager is teaching us about the outer solar system. And we will seek to test those results as we did with Galileo and now Europa Clipper and then Cassini at Saturn.

The next big mission to the outer Solar System will be at Uranus where we'll follow up on Voyager's very interesting and strange observations. The trail we're unveiling today will be a testament to his bold curiosity, his visionary leadership and passion for science that enabled us to explore further into the cosmos than ever before. To follow in the footsteps of Ed Stone as to walk in the path of a giant. We're thrilled to honor his legacy and impact today with the Ed Stone Voyager Exploration Trail. Thank you again for being here and joining us to honor his legacy.

Mat Kaplan: Laurie Leshin, thank you so much. You talked about Ed Stone as a pioneer, but also as a mentor.

Laurie Leshin: Yeah, Ed was an amazing leader in every aspect. He led the laboratory with so much energy and vibrance, but he also mentored individuals and helped them see their paths to the future. Just like the incredible Voyager path through the solar system, he helped people see their own path.

Mat Kaplan: It's been my honor to talk to I think five different JPL directors over the years. I think every one of you has had big decisions to make and maybe terrible decisions to have to make. And you alluded to that as you were talking today, and how Ed faced some of those same challenges. It's part of the job, sadly, isn't it?

Laurie Leshin: Well, Ed definitely led the lab in a time of great change. A lot of NASA aficionados will remember the faster, better, cheaper era as a time of great upheaval, but also a time of great innovation and when things are challenging, and we certainly have had a challenging year at JPL. That's what I try to think about. How do we actually leverage this moment to think differently, to innovate and to drive to a brighter future?

Mat Kaplan: How does his example, and perhaps other directors as well, but specifically Ed, does that play a part, and does it guide you to any degree in how you keep this place ticking?

Laurie Leshin: I absolutely think about what would Ed Stone do? What would Charles Elachi do? I absolutely think about those things.

Mat Kaplan: It could be a little rubber bracelet.

Laurie Leshin: Yes, exactly. And luckily I was able to consult with them, with Ed during his life and certainly with Charles and Mike as predecessors. We walk in great footsteps here, and they have a lot of knowledge and experience and also wisdom, so I always like to take advantage of that.

Mat Kaplan: We could talk about all sorts of individual magic tricks underway here, but I can't let you go without getting a report on Europa Clipper. All going well, right?

Laurie Leshin: Europa Clipper is rocking it. They are doing great. The spacecraft is flying beautifully. Obviously, we had it here for many years and then when you launch it, you still got to kind of learn how to fly it. It's been incredible. So we've done all of the major deployments including the magnetometer boom and the radar antennas, and just this week we moved to reaction wheel control of the spacecraft, which was really the last big event before our Mars flyby on March 1st, 2025. Be there.

Mat Kaplan: I can tell you now because by the time people hear this, I think it'll be public, that we do our regular best of 2024 in space survey of our members and people at large, space fans at large and far and away number one in several categories this year, you got it. Europa Clipper.

Laurie Leshin: Europa Clipper rocks. I'm so proud of the team, and I think Ed Stone would've been thrilled with the science that we're going to get. Really following up on those first Voyager flybys of Jupiter. What an incredible legacy it lives on.

Mat Kaplan: As we stand here, people may be hearing a forklift behind us getting ready for the next event here on this beautiful plaza. The Innovation Challenge.

Laurie Leshin: Yes.

Mat Kaplan: Talk about what that represents as part of JPL's role in the world.

Laurie Leshin: The Innovation Challenge is all about bringing innovations forward from the next generation, and to me, again, that perfectly reflects who we are as a laboratory. We are proud of what we've currently achieved, launching Europa Clipper in 2024, amazing, but we're always looking to what's next. We always want to spark imaginations to come up with that next innovation and we'll celebrate that today with The Innovation Challenge.

Mat Kaplan: Laurie, I hope I get to see you before then, but I sure hope I'm around to help celebrate the 50th anniversary of the two Voyagers in space. It's not far off.

Laurie Leshin: It's not. It's less than three years away now. Voyagers at 50, and I'll tell you they're the little spacecraft that could, although not that little. And there's a challenge to fly them at this age. It's non-trivial and the teams are working incredibly hard to make sure we've got two great Voyager spacecraft at 50.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, Laurie.

Laurie Leshin: Thank you.

Mat Kaplan: Current JPL director, Laurie Leshin. Also saluting Ed Stone that day was JPL director emeritus Charles Elachi. He took over running the lab after Ed left the job. I asked Charles about the difficult times JPL has gone through repeatedly over its long history.

Charles Elachi:

That's normal that you go through tough period and sometime you go through great period because when you do exploration, it's tough technically. It's tough communicating it to the public. It's tough convincing people in Washington to do these things because the funding organization, I mean NASA and Congress, they have so many different priorities. And you have to come and show them the critical importance of discovery and exploration.

The founder of Planetary Society were superb example of that, Carl Sagan and Bruce Murray were superb examples of trying to convince the public, Congress that exploration should be a high priority for our country. I know JPL is going through some tough time today, but I'm sure it will be overcome over the years, I've seen it. I worked at JPL for 50 years, almost all my career, so I've seen things going up and down over this period. And the critical thing is to keep being positive and proactive even in tough times, and keep a smile all the time about it. And I'm sure things will work well because fundamentally, the public does support exploration, and Congress does support exploration, but you have to keep communicating it regularly.

Mat Kaplan: We'll keep trying to do our part at The Planetary Society. Thank you, Charles.

Charles Elachi: Yeah, thank you very much, and thank you for all what you do.

Mat Kaplan: I could have gone up to almost anyone at the dedication ceremony and known I was about to talk with someone who had made invaluable contributions to robotic and other exploration of the Solar System and the cosmos beyond. As you'll hear, I had a special reason for asking retired engineer and project manager Glenn Cunningham, if I could spend a few minutes with him.

Glenn Cunningham: The long time I've been here at the laboratory, I had many jobs starting in the Voyager project as a system engineer and then team chief for the Voyager spacecraft team between the flights from launch to the two Jupiter encounters. Then I kind of moved into the Mars missions for a long time. I was the deputy project manager of Mars Observer for a while, and then the project manager. And then I was the project manager of Mars Global Surveyor, and after that I worked in the directorate that managed the Mars missions as deputy director of the Mars projects.

Mat Kaplan: They kept you busy.

Glenn Cunningham: Very busy, a really varied career, which was fabulous.

Mat Kaplan: And during a lot of that time, you were working with and under the leadership of the man that we are honoring today, Ed Stone.

Glenn Cunningham: Absolutely.

Mat Kaplan: Did you cross paths a lot?

Glenn Cunningham:

Frequently. Early on when he was the project scientist for Voyager, I was just a lowly system engineer, and I would admire him in meetings. We didn't interact very often. When I got to be in the flight operations, we interacted frequently because we had to keep the spacecraft operating so well so that his science teams could be making all of the wonderful discoveries they made. Then when I was in the Mars missions and doing the project management jobs and Ed was the director of the laboratory at that time, we interacted a lot. Especially on the Mars Server project, which came to a kind of bad demise. We didn't quite make it to Mars, but there was a big press event, many press events as we tried to restore the spacecraft operation. And Ed always led ahead of us. It was so wonderful. We would work very hard here. The press would be knocking at the door, wanting to know what was going on all the time.

Ed always took the ball and led us and spoke to the press and was reassuring to the public and it was just a great interaction. I really appreciated the pad that he gave us. He was an excellent leader from the standpoint that he lets you do the work. He wasn't a guy that told you what to do every day, couldn't ask for better leadership.

Mat Kaplan: One of the reasons I wanted to talk to you in particular is just the selfish self-interest of The Planetary Society because you did and do so much for us. I mean among other things, I saw you listed as project manager for that wonderful old project we did, Red Rover Goes to Mars aimed at young people, which was just a terrific success.

Glenn Cunningham: And it was a really fun and challenging opportunity to bring Mars operations, Mars spacecraft, science stuff to kids all around the world. And we had the contest to select members from around the world to come and participate, and we ended up having several kids participate with the missions, with the 98 missions. It was really a very challenging and enjoyable time.

Mat Kaplan: I'm glad you feel that way about it. We look back on it very fondly, and thank you very much for what you've done for the society, but also for JPL. And for all of the missions that you've worked on, and for joining us for a couple of minutes.

Glenn Cunningham: Well, thank you very much, Mat. It was a pleasure to do it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll be right back after the short break.

Jack Kiraly:

I'm Jack Kiraly, Director of Government Relations for The Planetary Society. I'm thrilled to announce that registration is now open for The Planetary Society's flagship advocacy event, the Day of Action. Each year we empower Planetary Society members from across the United States to directly champion planetary exploration, planetary defense, and the search for life beyond Earth. Attendees meet face-to-face with legislators and their staff in Washington DC to make the case for space exploration and show them why it matters.

Research shows that in-person constituent meetings are the most effective way to influence our elected officials, and we need your voice. If you believe in our mission to explore the cosmos, this is your chance to take action. You'll receive comprehensive advocacy training from our expert space policy team, both online and in person. We'll handle the logistics of scheduling your meetings with your representatives and you'll also gain access to exclusive events and social gatherings with fellow space advocates. This year's Day of Action takes place on Monday, March 24th, 2025. Don't miss your opportunity to help shape the future of space exploration. Register now at planetary.org/dayofaction.

Mat Kaplan: Ed Stone was also a devoted father and husband as we heard from his daughter, Janet Stone. Here's a brief portion of what she shared with Ed's friends.

Janet Stone: Dad would love simply the fact that the walkway is here where many of the thousands of Voyager family members have lived because he would have been the first to acknowledge the success of this whole vast and talented team. And he would love that it can continue to be added to, just like humankind's knowledge. Just like humankind's understanding and just like humankind's story in the cosmos. On behalf of the Stone families and on behalf of Dad, thank you for this extraordinary installation. Dad would express out loud wonder at the ideas it acknowledges and the ideas it will spark and quietly and privately it would touch his heart. A perfect celebration. Cheers to all of you for it.

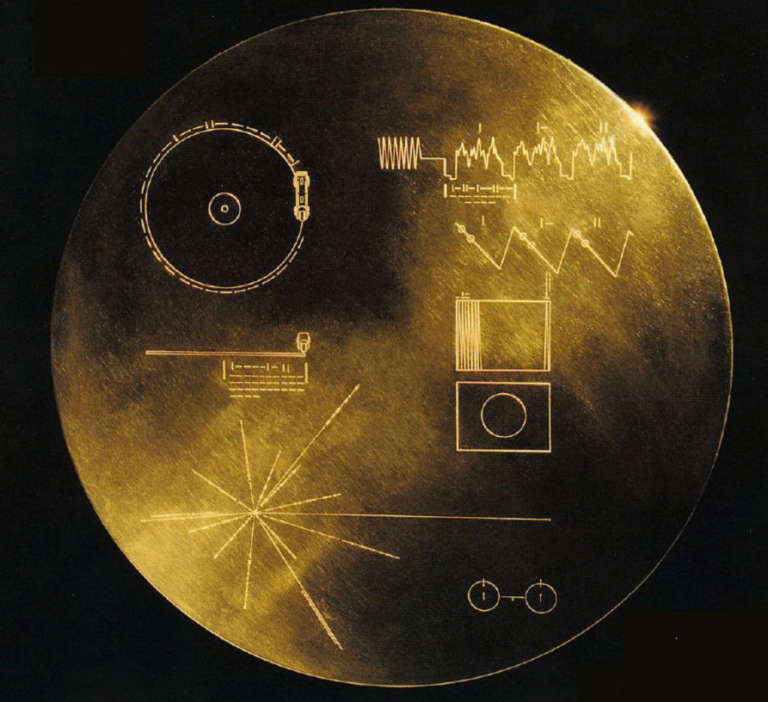

Mat Kaplan: Janet Stone and her family also had a very special gift they presented to JPL. For many years Ed had proudly displayed in his home an original flight spare of the cover for the famed golden record, the magnificent collection of images, voices, and music that even now heads further into interstellar space aboard the Twin Voyager spacecraft. I asked Janet and her sister Susan about this gift and more when they joined me after the ceremony.

Janet Stone: Hearing all these other people sharing our admiration touches our hearts because it's dad. It also touches our minds. There is so much learning and so much passion for continued exploration of all kinds, not just space here that it's a very inspiring place to be and very inspiring people to hear from.

Mat Kaplan: I'm not sure that I could have parted with that lovely gift that you gave to JPL or returned to JPL. That flight spare of the beautiful cover of the Voyager golden record. Was it at all hard to part with? I mean, that's a lovely thought.

Susan Stone: It meant a lot to him and it means a lot to our family. We always knew that when our parents passed, it would go to a public home of some type because it's just too important a space history memorabilia item, and to have it come back to JPL just seems very fitting.

Mat Kaplan: This is only the latest of many honors that your father has received over the years. I loved when Linda Spilker said, "He's still very much a part of the Voyager mission. Basically, his fingerprints are all over those interstellar travelers."

Janet Stone: So dad's fingerprints, so to speak, are not only all over Voyager, but they're also all over many scientific endeavors, not just space exploration, but through a lot of different disciplines. People who grew up listening to the Voyager news conferences and that sort of thing were inspired to pursue science of any kind, not just space science, so anything from research into Messenger RNA to the Voyager spacecraft, there's a little bit of Ed Stone in a lot of that.

Susan Stone: I think one of the things that has become more evident to me through the process of celebrating his life is all of the things that he did touch, and it wasn't really even just a touch. It was like the firm grab and a big contribution. He provided a foundation of a lot of things like the telescopes and Voyager and JPL and space exploration. And it's been very humbling to see the great impact he had.

Mat Kaplan: It was finally time to hit the trail, and who could have been better trail mates than the current leaders of the Voyager Interstellar mission? You'll hear us enjoy just a few of the many plaques embedded in the Ed Stone Voyager Trail that turn it into a timeline of the mission's stellar accomplishments along with other milestones in Ed's long career.

Linda Spilker:

Ed and I first met in 1977 when I began working on Voyager right out of college. I remember watching in awe as Ed skillfully ran the Voyager team meetings and organized the press conferences. He coordinated the science activities and each of the six Voyager flybys.

Ed was always patient and calm as he led the science discussions and sometimes they got quite contentious. He asked penetrating questions, weighed the science justification, and then made very thoughtful decisions. Observing Ed's unique leadership skills for 12 years through the four planetary flybys was like watching an accomplished conductor lead an orchestra scientist as they composed a new symphony of discovery for each of the planets that Voyager visited. Each flyby has its unique plaque along the Voyager Trail.

Mat Kaplan: Going to close out today talking to two of the people, maybe the two people who are still most involved and most responsible for the Voyager Interstellar mission. We have talked many times before. Linda Spilker, project scientist, Suzy Dodd, project manager. Welcome to both of you.

Linda Spilker: It's a pleasure to be here, Mat. Thank you.

Suzanne Dodd: Yeah, thank you very much. I'm glad you could make this event.

Mat Kaplan: Let's walk. Tell me about this very... Well, it's not the first stop, but it's the first one we're looking at, means a lot to us at The Planetary Society as well as I'm sure to the two of you.

Linda Spilker: This plaque commemorates the pictures that Voyager 1 took for the family portrait of the Solar System on Valentine's Day in 1990. And in particular, that very special picture of the pale blue dot, which was Earth captured in a sunbeam, and it really provided perspective of just how tiny our very precious world is.

Mat Kaplan: Suzy, that's, I don't know how much you were involved, but I know that was a big deal, right? Getting the spacecraft turned around to look back toward the sun.

Suzanne Dodd: It was a big deal. It took a lot of negotiations I think with NASA. A great idea that has served over time and is certainly what people think about when they think about Voyager. They think of that pale blue dot picture and puts the perspective of how big space is and how small we really are in the universe.

Mat Kaplan: Well, I think about a lot more than the pale blue dot, but it's right up there near the top of the list, if not at the top. What do we got here, Linda?

Linda Spilker: This is Pathfinder and Sojourner land on Mars, and this was during the time that Ed Stone was director of JPL, so this happened in 1997. So it's commemorating events that happened during his tenure as director. And for the pale blue image I would add that Carl Sagan was really instrumental in helping convince NASA that it was worth doing, spending the resources to turn Voyager 1 back and take these images before the cameras were turned off.

Mat Kaplan: We're about to walk over Sojourner and Pathfinder, sorry guys. I think back. I mean that was during the, I always get them in the wrong order, the faster, better, cheaper era, which was, I guess it was a real challenge, right?

Linda Spilker: It was. It was. It was a new era where NASA was trying to balance the costs of the mission and the schedule as well. This plaque is really a nice one for Voyager 1.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, I forgot we didn't talk about this one. Okay.

Linda Spilker: This next plaque commemorates when Voyager 1 passed the distance of Pioneer 10 when it had stopped operating and became the furthest human-made object in the Solar System.

Mat Kaplan: And there is Pioneer 10 shown on this plaque along with Voyagers 1 and 2. All right, let's walk a little bit further. We heard several times today about Ed Stone being a very fast walker, probably much faster than the pace that we're taking along this path that honors him. Did either of you do any of those walks?

Suzanne Dodd: Well, it was hard to keep up with him, yes.

Linda Spilker: He was very good at, I remember a cartoon that someone drew on Voyager. It was a cartoon of Ed Stone and he had on this hat with wings. It showed that the wings sort of lifted him off the ground and he could go very, very quickly.

Suzanne Dodd: A man with a purpose.

Mat Kaplan: We'll probably stop here, but the path, actually two paths following roughly Voyager 1 and Voyager 2's path through the Solar System. Tell us about this one, Suzie?

Suzanne Dodd: Well, this plaque is here where Voyager 1 crossed the termination shock, and the termination shock is where the particles from the sun go from supersonic to subsonic. What it tells you is that you're getting close, okay, we're getting close to crossing the Heliopause and getting close to getting into interstellar space. Even though when you look down the road, you won't see the other plaque yet because it took several more years from the termination shock crossing to get down into interstellar space. But this is what really wet people's whistle, right? Got people really excited that we were getting close to crossing into interstellar space with the Voyager spacecraft.

Linda Spilker: Right, it took actually 23 years past the Neptune flyby before in 2012, Voyager 1 crossed the Heliopause. We didn't know where the Heliopause was. There were so many models, so many theories, and every time we crossed a model's distant point, they had re-evaluated and said, "Oh, no, we've added another five or 10 AU to our number." And so it kept getting further and further away, but we didn't know until we crossed it.

Mat Kaplan: And the two Voyager spacecraft, they've certainly had their challenges lately, but I'm thinking of how they are still delivering great science. This recent Uranus story as we speak, it was only what, a couple of weeks ago, I think the announcement came out, based on Voyager data, and it's told us very important unsuspected stuff about Uranus.

Linda Spilker: Right? It turns out that some scientists here at JPL looked once again at the Voyager Uranus data. The magnetosphere was highly compressed and very unusual because all of the plasma was gone. They didn't see any plasma, and so they looked more carefully and realized if they could track it back to what was happening on the sun. A huge solar event had compressed the Uranus magnetosphere, very unusual, happens only about 4% of the time. That allowed all the plasma to flow out the tail. It also populated the radiation belt, so they look stronger than usual. And what's really significant is we now think there could be plasma in the Uranian magnetosphere, and if that plasma is there, it might point to possible ocean worlds.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, my.

Linda Spilker: Moons with global oceans beneath them. Some of Voyager's images of the moon ariel are especially tantalizing, so reminiscent of what we've seen on other ocean worlds.

Mat Kaplan: Water, water everywhere. It just keeps going. Suzy, about those challenges, how's the health of the spacecraft?

Suzanne Dodd: Well, today they're both very healthy. What we like to say, "Anomaly-free today," but there's many challenges. They are the senior citizens of spacecraft and have far outlived their original four-year design. And honestly, it's remarkable that both two spacecraft and they're both operating after 47 years. We have to manage the power very carefully because our power from our radioisotope thermal electric generators, the nuclear power source is degrading. Also it's very cold in space, and so we're finding some issues thermally that we also have to manage. So it's a challenge to keep them both healthy, but to date, we've been able to do it. And we're focused on continuing to do that to get these spacecraft out to 50 years so we can have a much bigger party than we did today.

Mat Kaplan: I really look forward to that. I told Laurie Leshin I sure hope I'm around to help you celebrate the 50th. As we celebrated the 45th not too long ago. Linda, I also said to Laurie, Ed Stone's fingerprints and much more are still very much a part of this mission.

Linda Spilker: That's right. In fact, for me, Ed Stone's fingerprints are on both Voyager spacecraft with his keen intellect and just his devotion to Voyager. Part of Ed lives on in those two Voyager spacecraft.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you both for walking this tiny portion of this brand new path or paths at JPL. I hope that more people will have a chance to do these at least during the JPL open houses. And I can't wait to talk to the two of you again the next time we need an update on the Voyager Interstellar mission.

Suzanne Dodd: Great. Thank you very much, Mat.

Linda Spilker: Thanks, Mat. It's been a pleasure.

Mat Kaplan: Voyager project manager Suzie Dodd, who is also director for the Interplanetary Network Directorate at JPL and Voyager project scientist Linda Spilker. I'll close with this bit of tourist advice. Don't miss the chance to visit the Jet Propulsion Lab for either a group tour with 20 or more of your friends or classmates, or for one of the lab's immensely popular visitor days. And when you do, be sure to follow in the rapid footsteps of Dr. Edward Stone. For Planetary Radio, I'm Mat Kaplan of The Planetary Society.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

Thank you, Mat. I am so relieved that the Ed Stone Voyager Trail and the rest of the lab suffered no fire damage. As we mentioned earlier in the show, more than 200 members of the JPL team tragically lost their homes in the Eaton Fire. Our hearts go out to them and everyone else who's suffered in the aftermath of these devastating fires in LA. We dedicate this week's episode to them.

I'll provide resources on this episode's Planetary Radio webpage so you can find ways to help support the fantastic workers of JPL and Caltech. And if you'd like to honor Ed Stone in person by walking his new trail, we'll also share the link for information on public tours of JPL. Now let's check in with Dr. Bruce Betts, our chief scientist for What's Up. Hey, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hi, Sarah. How you doing?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Doing all right. So this week we got to listen to Mat's grand adventure to go to JPL to talk about Ed Stone and his legacy and the dedication of this memorial trail for both Ed Stone and Voyager. And during the conversation, they got to bring up one of the most important things that Voyager did, which is this grand tour of the Solar System.

Bruce Betts: Road trip.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Road trip. I mean, it's kind of like the biggest planetary road trip that's ever existed, at least as far as we know as humans.

Bruce Betts: Yes. Wow. Profound caveat I'm going to move past.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I've been asked in the past a few connected questions. One, how is it that Voyager is the only spacecraft that's managed to go to Neptune and Uranus? So there's that right off the bat. And also how did it manage to go to so many planets with only two spacecraft? What happened here that allowed Voyager to actually accomplish this?

Bruce Betts:

Luck, man, they sent it to Jupiter and it's like, I think we can get to Saturn. I think we can get to... That is so not true. It was the development of the so-called Grand Tour. Basically once every, I think 175 years, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune line up, so to speak. They're not lined up, but they're such that if you get a gravity assist from Jupiter, you can head to Saturn. From Saturn you can head to Uranus, from Uranus to Neptune. So each of them bends your trajectory and imparts more energy and gets you there faster, despite the fact that it took 12 years to get to Neptune. So this is something that was recognized, I believe you told me, from by a Caltech grad student, go Caltech, and then was developed later. So it's interesting though, being the government and funded by the government, they wouldn't commit to Uranus and Neptune.

So when they were launched, they were Jupiter and Saturn, and then it was spectacular. So they got funded to go out and do Uranus and Neptune. They made the choice with Voyager 1, they wanted to check out Titan because it's freaky interesting, not really knowing at the time that they would only be able to see an orange ball of haze.

And to do Titan, this is more than you asked for as usual, to do Titan that took them on a trajectory that they couldn't go to Uranus with Voyager 1. Which they knew, but they had Voyager 2. So Voyager 2 was put on the grand tour trajectory to do Uranus and Neptune. Basically let's keep track of Uranus and Neptune are way the heck out there. So it's very challenging to go out there, as is Pluto, of course, even farther out most of the time.

And so being able to get the gravity assist from the giant planets, you get out there and you get out there more efficiently. And it was just super cool. I mean, there was our reconnaissance, our only reconnaissance of Uranus and Neptune, and not our first reconnaissance of Jupiter or Saturn, but our first serious nice instruments, pretty pictures, views of it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's so cool. And I'm now thinking about the fact that they decided to go to Titan with Voyager 1 instead of going out to those other worlds. I'm really glad that they recognized that Titan was such an interesting world, but kind of tragic that all they could see was the haze, right? We could have gotten two flybys of Neptune and Uranus.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. I agree with you, but there's also another trade off, which is by doing that they then use Saturn's gravity to send them up out of the plane of the planets, out of the Ecliptic plane where all the planets are basically revolving around the Sun. And so therefore they have been able to sample, especially when they get out to the edge of the Heliosphere, the magnetic field into interstellar space. You've got Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 doing it at two very different parts of the Heliosphere. So there's also for those who party with particles and fields and love such quirky things, that also is an advantage that way.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's funny that they wouldn't even commit to Neptune and Uranus and now thinking about it all these years later, what an asset to have those in different locations so we can actually measure all the particles going on in interstellar space at different locations relative to the sun. That's a whole knock on that they really did not plan. And one more reason why the Voyager spacecraft are still just, I don't know-

Bruce Betts: They're amazing.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: They're amazing. I don't know if I can ever think of them as not my favorite spacecrafts because the images that came out of that mission really, really impacted me and everybody else. And to this day, it's still, still all we have of Uranus and Neptune, apart from our long range observations with telescopes.

Bruce Betts: Right. Which just got a lot better with JWST. But still, again, they're really far out there. Neptune, 30 times the Sun-Earth distance. It's way out there. I don't know that I mentioned that. So anyway, I do want to say Ed Stone was amazing and his Voyager role, director of observatories, Caltech professor, and he has a wonderful family as well. So he is missed, and apparently the entire world has said that already. So I'm not new, but I wanted to add that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'll also link on this episode page to our previous episode where we had some people send in their beautiful audio messages about what Ed Stone meant to them because clearly he not only had a huge impact on the space community, but on the people in his lives. So I'll share that as well, so we can all pay tribute to him and all the wonderful work that people at JPL did.

Bruce Betts: Nice.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: All right.

Bruce Betts: You ready to move on to some random space fact.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That one sounded painful.

Bruce Betts: That one was painful. That was a mistake. Speaking of mistakes, I wanted to talk about the Buran Soviet shuttle and note that many things about it, but mostly that it only flew one mission and it was without humans on board, but also there are a lot of other interesting things. Flew once in '88, and then with the Soviet Union in the following years and money going away, it did not fly again. It looks like the US space shuttle, and apparently not surprisingly, that's not coincidental since it was one of the first real examples of using the internet for espionage.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Really.

Bruce Betts: There was a lot of unclassified documents online and they could be accessed that the KGB assembled all sorts of information, apparently. I mean this what I've read, and that's why I mean it looks almost identical. And I mean, they use tiles. It's very, very, very similar. They did have their successful autonomously controlled mission, or at least it went up. It went down, it survived, but it's just a weird story. And then it was in some type of hangar or a building in Kazakhstan, which collapsed in 2002, I think. So it's under rubble and debris in Kazakhstan.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's tragic. Someone needs to unearth that and put it inside a museum or something.

Bruce Betts: Thanks, Cindy. That belongs in a museum.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I mean it does though. Oh, man. And NASA not knowing that you got to secure your files in the early age of the internet. Man, we've come a long way. Now I'm constantly reporting phishing emails.

Bruce Betts: Okay, Sarah, I want you to go out there, look up the night sky and think happy thoughts with smiley faces and flowers and party poppers everywhere. Thank you. Good night.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with a surprising look at new modeling on the formation of Pluto's largest Moon, Charon or Kairon, depending on how you'd like to pronounce it. If you love the show, you can get Planetary Radio T-shirts at planetary.org/shop, along with lots of other cool spacey merchandise.

Help others discover the passion, beauty and joy of space science and exploration by leaving a review or a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day, but helps other curious minds find their place in space through Planetary Radio.

You can also send us your space thoughts, questions and poetry at our email at [email protected]. Or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the Planetary Radio space in our member community app. Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by our dedicated members, Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. And until next week, ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth