Planetary Radio • Jan 01, 2025

The Planetary Society’s 45th anniversary with Bill Nye

On This Episode

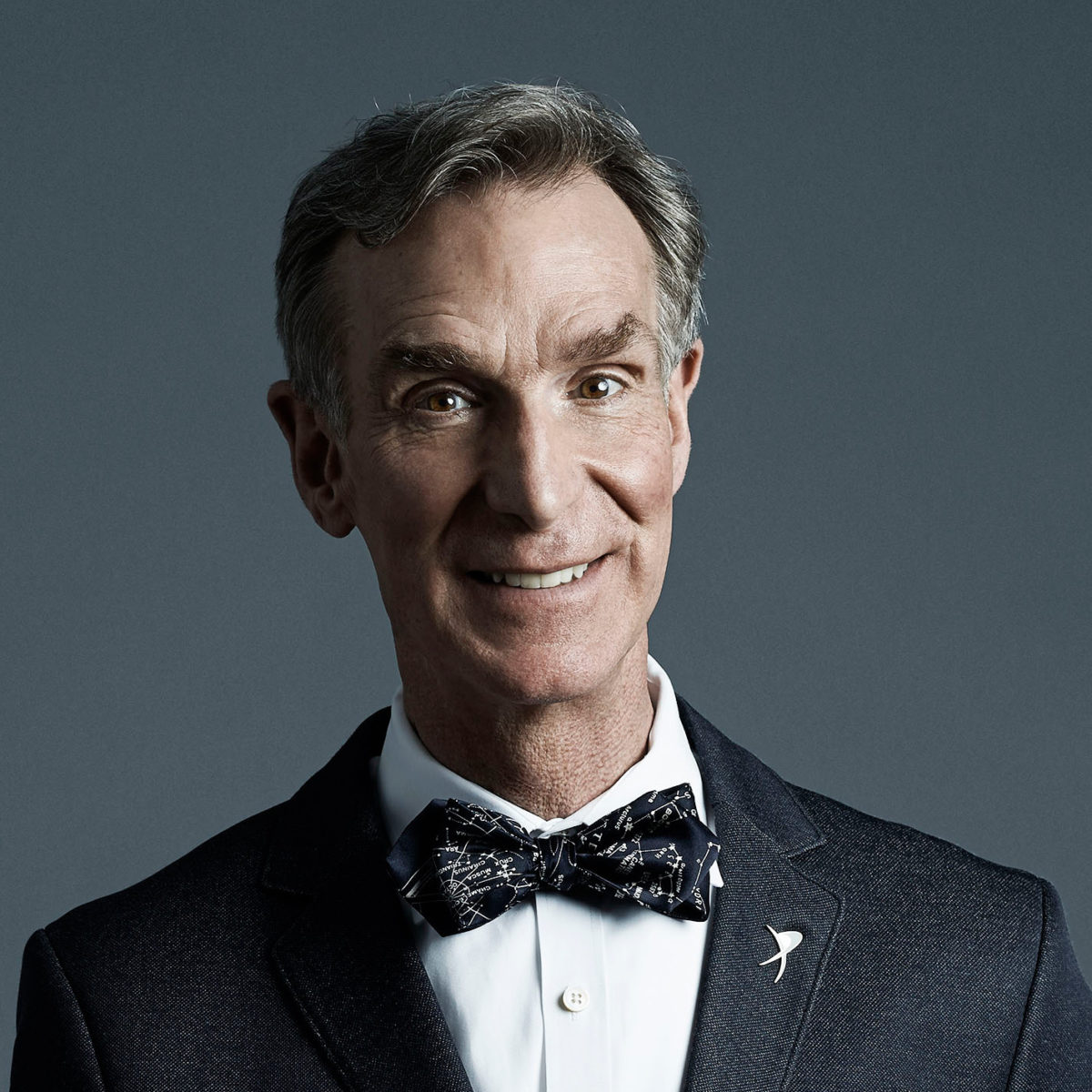

Bill Nye

Chief Executive Officer for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

Planetary Radio kicks off The Planetary Society's 45th anniversary year with CEO, Bill Nye. Bill reflects on the organization's first forty-five years and what humanity has learned about space in that time. Then, Chief Scientist Bruce Betts joins in for the first What's Up and Random Space Fact of 2025.

Sailing the Light Sailing the Light tells the story of the LightSail mission, a crowdfunded space science project from The Planetary Society.Video: The Planetary Society

Related Links

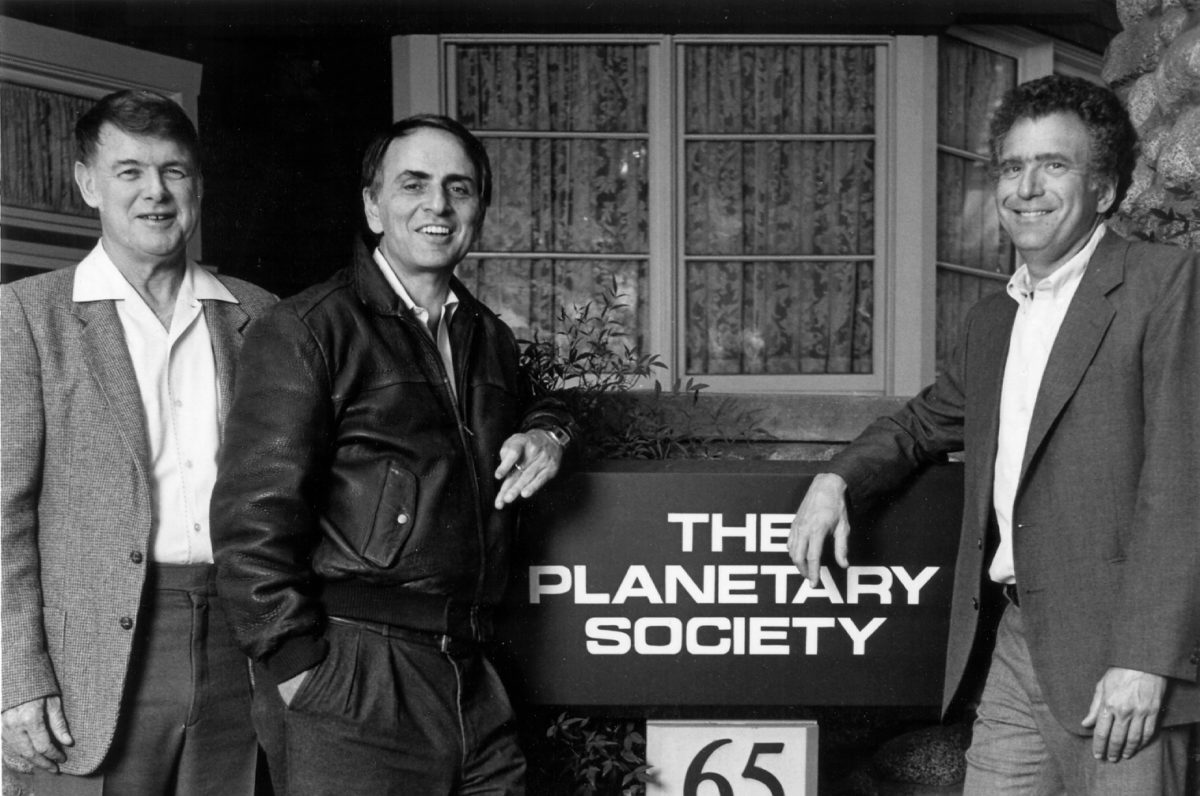

- Our Founders

- The Day of Action

- The Planetary Report

- Sagan on the Tonight Show

- LightSail

- New Horizons

- Asteroid Apophis: Will It Hit Earth? Your Questions Answered.

- Gene Shoemaker Near-Earth Object Grants

- Mars Sample Return, an international project to bring Mars to Earth

- The boy who named Bennu is now an aspiring astronaut

- Red Rover Goes to Mars

- A rare letter from Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- The night sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Happy New Year and happy 45th anniversary to The Planetary Society. This week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. The season has changed, a new year has begun, and we're kicking off The Planetary Society's 45th anniversary with our CEO Bill Nye. He'll reflect on our organization's first 45 years and what humanity has learned about space in that time. Then our chief scientist, Bruce Betts, joins me for What's Up and the first random space fact of 2025. If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it. We live in a time when space exploration has fundamentally changed the way we understand and interact with our universe.

Our modern technology relies on space exploration from weather forecasting to the global positioning satellites that enable navigation. Spinoff technologies have changed the way we build how we farm and eat, our medicine, and the ways that we communicate. Humans have had a permanent international presence in space for over two decades aboard our various space stations. Our robotic emissaries have visited every planet in our solar system that we know of so far, along with numerous moons, asteroids, and comets. Our spacecraft have even ventured into interstellar space. We've looked out into the vastness of the universe beyond and discovered thousands of worlds, deep mysteries, and a meaningful scientific connection to all that surrounds us but all of this could have been very different. In the years after humanity's first space adventures in the 1950s, '60s, and '70s, it was clear that there was enormous public interest in space exploration.

But as NASA's crewed lunar exploration program, Apollo ended so did much of the funding for space exploration in the United States. NASA's budget was cut over and over again, jeopardizing its programs and partnerships and the dreams of space fans all around the world. So in 1980, Carl Sagan, Louis Friedman, and Bruce Murray founded The Planetary Society, a nonprofit dedicated to giving people all over the world an active role in advancing space exploration. Today, our organization is the world's largest and most influential nonprofit space organization with a global community of more than two million space enthusiasts. For 45 years, we've been advocating together, shaping the future of space exploration, and supporting the missions that matter so we can explore worlds, search for life beyond Earth, and defend our planet from asteroid impacts. The Planetary Society is not solely responsible for pushing forward space science, but we've had such a profound impact that there's literally no way I could cram all of it into one show.

Thankfully, we have our whole anniversary year to share stories. I am now joined by The Planetary Society's CEO, Bill Nye. You may recognize him from his science education shows, including Bill Nye The Science Guy, Bill Nye Saves the World and The End is Nye. Under his leadership, The Planetary Society launched our LightSail program and created the first fully crowdfunded spacecraft in history. Bill is a mechanical engineer, an author, an advocate, and someone I've come to call a friend. Hey, Bill.

Bill Nye: Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Or I guess as Matt would say, "Hey boss."

Bill Nye: Yeah, sure, boss. Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: No, but really though I've been looking for a good reason to bring you onto Planetary Radio again for an age. I mean, as my first interview-

Bill Nye: One age, a full age.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Like two years, that counts as an age almost.

Bill Nye: Yeah. Well, so I'm a charter member, everybody.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How did that happen?

Bill Nye: So everybody understand. I took one class from Carl Sagan because I had finished my engineering requirements at Cornell University and I took Astronomy 102 to relax, to have fun-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Chill at that.

Bill Nye: ...and it was fun, and Sagan was a poet. People talk about him with reverential adjectives, but it's a worthy thing. The guy really was something else as a lecturer and of course, a visionary and people like to point out, he had quite a record of scientific accomplishment also. But that aside, after you take a class from Sagan in 1977 when he and his buddies start The Planetary Society, two years later, you end up on the mailing list. So I got a paper letter in the mail. I thought it sounded intriguing, and I joined and I was the member that we still cultivate, which was, I remained a member largely to subscribe to the magazine, The Planetary Report. But as it goes on, you get more and more involved. I bought Louis Friedman's book about solar sailing, which I'm going to say was from 1985. It's in the lobby here of The Planetary Society. We can look at the copyright.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I have a copy at home too.

Bill Nye: Yeah. And I was very much intrigued by that because coincidentally, my buddies and I in college would watch The Tonight Show quite regularly, and Sagan would be on there all the time because Johnny Carson was a fan of his as a guest, and I was intrigued, charmed, amazed. Then Sagan's kids by Andrea and Sam and Sasha Sagan watched the Science Guy show. So then I was asked to be vice president.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh, that's how that happened.

Bill Nye: I used to be on the board rather then vice president. Then as I like to say, you leave the room and they take a vote, and now I'm CEO. You got to watch out but I have been on this journey with the society since 1980.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But long before that, you already clearly had a passion for science. How did you initially fall in love with space?

Bill Nye: Falling in love with space. Well, let's say I fell in love with airplanes and mechanisms really early on, and the story I've told many times. My father had been a prisoner of war in World War II. Every time I think I have a problem, I'm just like, get over it. Okay. He was captured from Wake Island, middle of Pacific Ocean, nowhere on Christmas Eve, 1941. They were bombed on the same morning as Pearl Harbor, as part of the Japanese naval strategy take over the world, something or other. He became fascinated with the stars because they had no electric lights at night, and I guess they had very seldom had electricity, and he was the Astronomy Merit Badge counselor for the Boy Scouts.

And we had a telescope, and I've told this story a few times. It was made from the cardboard tube you use for casting pillars for a house foundation, and the scoutmaster mounted his own mirrors and an eyepiece and this and that, and it was a very nice reflector because those tubes are very stiff. I mean it's solid piece of stuff. And I remember looking at the moon for the first time, and I'm sure listeners to the show like the craters in the mountains, dude.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's insane. It's so cool.

Bill Nye: That's not a round thing. So these are classic, to me, astronomical experiences that I hope everybody who listens to this podcast has had. So then when I take a course from Sagan, I'm super transformed. Physics is cool. Mechanical engineering is all applied physics. I did well in electrical engineering, and I say all the time if everything had been different, I would've gone into antennas. Antennas fascinate me. Big mechanical things, controlling invisible fields it's very cool to me. Anyway, but things weren't different. I ended up at Boeing, which was a cool for a great first job, and I stayed connected. I was connected to The Planetary Society because I got this letter a few years after I started full-time work in the engineering workforce, and then I got just more and more connected to The Planetary Society to now we're doing this podcast.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I did not know The Planetary Society existed until I had already graduated from my university with a full degree in astrophysics. I'm sure I'd encountered many of the things The Planetary Society had done clearly, but it wasn't until I was at a star party and Geo Somoza one of our-

Bill Nye: Oh, Geo. Love Geo.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh my gosh. One of our best volunteers ever. He's a huge advocate for us and he was out there talking about The Planetary Society.

Bill Nye: Where were you? Here in Pasadena?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I was up at Griffith Observatory at a start party shortly after I started working there.

Bill Nye: So everybody, Griffith Observatory, I'm sure Sarah talks about it all the time, but yeah, it's a famous, famous place and it is spectacular. Where it is placed on the hill or mountain of Los Angeles is really spectacular. Carl Sagan and those guys put The Planetary Society here in Pasadena because of the Jet Propulsion Lab. And so when I was in class, he would come back and show these pictures of Mars that were fresh from the Viking mission the previous summer, 1976. And it was just astonishing, man. I mean, I know people talk about this, but really it was really something that no one had ever seen. And the thing about those pictures from Mars, even now, or maybe especially now, it's a place if you were dressed properly, the right space suit, you could walk around, have a picnic, take a meet, or play cards. It's just amazing that it's just an other world.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But now we live in a day and age where you can just hop on the internet and pull up the latest image from Mars. And maybe it's part of that access that has made it kind of... I don't know, people aren't amazed the same way that they should be, or at least so I feel until people who are deeply passionate about it sit down and they go, this isn't just a sweet image, dude. This is a picture of another world and here's what's going on.

Bill Nye: So I talk about climate change all the time. One of my claims or assertions or things for you all to think about is in the modern era, climate change was discovered on Venus trying to figure out what made Venus so hot. People trying to understand that realized it was carbon dioxide in the Venusian atmosphere, comparing the climates of Earth to Venus, to Mars, then Europa and Enceladus, and something that Sagan talked about all the time, or often enough, was the expression he famously used, "You and I are made of star stuff." I like stardust. Dust is pretty romantic, but it really is something to think about. Stars explode because you tell me that gravity gets overcome by the fusion energy flying out and they explode, and then these bigger atoms get created, bigger nuclei, and you and I are made of them. And the even numbers are more likely than the odd numbers. It's pretty wow.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's weird. And when you think about the fact that our sun isn't big enough to make most of those chemicals, it can make up to carbon, nitrogen, oxygen. Right? but-

Bill Nye: Oh yeah, right. We all know that, right, Sarah-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But to get the crazy stuff and the calcium, the iron, all of that. You literally need stars to be born and die big stars, which means that there were stars that were ancestors of our star even that blew up and lived out their lives and exploded and now you and I are here. We're deeply connected to these things in a way that makes me feel very important, but also very small and interconnected to something much larger than myself.

Bill Nye: Well, that's it. We're nothing. We're nobody.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right. But also in the scale of the universe, you and I are sitting here having a conversation about the complexity of all of this and the value of spending time and money to try to learn these things. How many rocks out there in the universe are thinking deeply about their state of being? We are so important.

Bill Nye: Oh, this is the thing, Sarah, you've hit the nail head-wise. I mean, it fills me with reverence every day. And as Sagan famously said, "We are, therefore, at least one of the ways that the universe knows itself." If that doesn't give you pause, people, what the heck does? That really is an amazing... It's just amazing. I get choked up thinking about it, how fortunate we are to live when these discoveries are being made. And along that line, Sarah, you are of a certain young age. I very much hope to be around, but you will almost certainly be around when we find evidence of life on another world and stranger still something alive on another world.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I hope so.

Bill Nye: And if we could find microbes under the sand of Mars or Europanian fish people swimming around under the ice on Europa, it would change the world. And we do it at a fraction of what it costs to do so many other things governments around the world are involved in. It's a cup of coffee per person every now and then. It's an amazing thing to be part of. So I know our listeners are all into these things, but I am part of the beginning of The Planetary Society, and I am honored to still be here.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, it speaks to both the value of this organization and all the advocacy we do for this, but also the side benefits of learning all of these things. I get asked pretty frequently, like why are we spending all this time and money exploring other worlds when there are so many big issues facing humanity? But then as soon as we go off in the universe and start exploring things, we encounter that idea. I think Bruce Murray came up with it, the unknown horizon. There are things that we're going to learn that are going to improve our lives, both because we understand ourselves and our place in the universe better, but also because of all the spin-off technologies and all of the jobs, there is so much value that comes out of this. So as an organization, I'm really glad we're fighting for this, not just that we can personally know more about the universe, which is what I'm curious about, but also because it has so much value for so many other reasons.

Bill Nye: It changes the world.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It really does.

Bill Nye: And so as Bruce said all the time, people would say, "Why are you sending these spacecraft? Why are you building these telescopes? What are you going to find?" We don't know what we're going to find. That's why we're looking. And so I'll claim, and this is I don't think is especially controversial, our ancestors who did not have a curiosity, who did not go over the hill to see what was in the next valley or what have you, they're not really our ancestors. They got outcompeted by the tribes that did have people that did want to go looking, that did want to explore and make discoveries. And so it's deep within us. And I'm not saying that justifies unlimited expense, but it does justify investments. And objectively the money you get out from space exploration overwhelms the money you put in, especially planetary exploration.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: There's still a degree of tribalism to the way that we go to space.

Bill Nye: Oh, man. Heck yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But I do value that we are not just an America-centric organization. We do most of the bulk of our advocacy in the United States because NASA is a behemoth. It's the largest space agency in the world, and most of our members are here, but we're not dedicated to only that-

Bill Nye: No. Heck no.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ...we've been working on collaborating between all these different space agencies for as long as we've existed. And I think that makes us pretty special.

Bill Nye: Yeah. Well, and people talk about LightSail, the success of LightSail. Understand we work closely with guys from JAXA, Japanese Aerospace who had given deep thought about the materials, how big it'd have to be, and especially how to fold it up. I'm not joking, you guys it is so cultural. You look at US-built spacecraft, a solar sail. It looks like we went to Home Depot or something and got everything square and this and that. When I was at JAXA, Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency, it's origami. They fold up their solar sail in these cool ways that we just don't grow up within the US. It's very enlightening. Enlightening, that's a pun when it comes to solar sails. And so we do our best to work with people, work around the world who are pursuing answers to the same questions.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Pluto is a great example of our contributions because the New Horizons mission to Pluto, I argue probably would not have happened without the advocacy of Planetary Society members.

Bill Nye: So we gave Alan Stern our Cosmos Award, the guy who he was with that thing from the 1980s advocating for that mission, that spacecraft going that fast and we were right there with him. Let's go, man. Everybody wants to know what's going on at Pluto. And when that thing launched, it was the fastest rocket to ever leave Earth. It was a very comparatively low-mass spacecraft on a comparatively huge thrust rocket. And it went out there and it got a slingshot from the planet Jupiter and was the fastest spacecraft ever shot and it went by Pluto and it changed the world. And I've heard those guys, the skeptics, the conspiracy theory people, why didn't they put it in orbit?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What? Sorry.

Bill Nye: Yeah. No, dude, it's going too fast. We didn't have the capability to slow it down and put it in orbit around Pluto and everybody, I remind you, Pluto is smaller than Earth's moon. It doesn't have a lot of gravity to capture a spacecraft going faster than ever launched and gotten slingshot from Jupiter. That was not possible. Cheer up. We did some cool things and we advocated strongly to get it redirected to Arrokoth and we did. We advocated strongly to get the Hubble Space Telescope to find that target, the Arrokoth target, another body way, way, way out there. And the reason Pluto in 1980 was supposed to be a traditional planet was because it's so shiny. It's covered with that you know more than I do frozen nitrogen. And so from Earth, a telescope on Earth, it looked like it was a big old thing. But it's actually as these things go pretty small, but big enough to be a ball. Has enough gravity to be a ball.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And then Arrokoth, this strange object is like a contact binary. We're finding these weird things out there.

Bill Nye: We sent that New Horizons mission out there for the cost of a cup of coffee per taxpayer once, and it's changed the way we think about everything. And practically, if you look, I'm going to say from memory episode four of the original Cosmos with Carl Sagan. He just says something along with traditional planets I refer to the ancient dinosaurs. I give it that adjective, ancient dinosaurs because we still have dinosaurs-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Birds.

Bill Nye: Birds, chickens, turkeys, they're dinosaurs, let alone pigeons and bluebirds and wherever else you got. Cardinals. So Carl Sagan just says roughly, "Well, they disappeared. Nobody knows why. Let's move on." So in 1980, nobody knew why the ancient dinosaurs disappeared. It was out when I was in the workforce as an engineer paying taxes and being a grown-up and driving a Volkswagen bug and living my life that people realized it was the Alvarez's realized that it was an asteroid almost certainly that finished them off. There may have been some volcanism in what is now India. There may have been a pair of asteroids... Whatever. It was an asteroid all event that finished them off and Sagan didn't know that. Nobody knew that in 1980.

But 1983, and now every school kid on Earth who's able has access to education knows this of course. We are learning about asteroids, and I can tell you as an Earthling do not want to get hit with an asteroid and we have to be ready to do something about it. And one of the changing it back to The Planetary Society, finally, one of the things we're working very hard to be involved in is Apophis named at least by one translation, named for the Greek God of anxiety, which is pretty good. That's pretty good.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I honestly hope that it terrifies everyone, not because I want to instill fear in people, but because this is a really important thing that we need to grapple with but it seems so disconnected from our everyday lives. It's like, yeah, okay, maybe the dinosaurs were killed by an impact 65 million years ago, but it's not going to happen to us. It is inevitable that Earth is going to get hit by something again at some point unless we take steps to prevent that.

Bill Nye: So we're pitching it as a global dress rehearsal for deflecting an asteroid. That's right. So everybody, if you haven't gotten the Apophis story if you haven't listened to every podcast, which is weird, the Greek God of anxiety will come closer to the Earth than the global positioning set... Closer than Sirius XM radio, let alone the moon on Friday the 13th of April, 2029. At The Planetary Society, we're working to get a mission to catch up with it, a spacecraft, or better yet, a pair of spacecraft to catch up with it on the way in. So for those of you out there who are listening to this podcast, please support The Planetary Society. We're working hard to have a global dress rehearsal for deflecting an asteroid to save humankind. That's a big deal saving humankind.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We have some lofty goals at The Planetary Society and-

Bill Nye: Lofty. See what she did there?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Lofty.

Bill Nye: Heavenly.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But I think that planetary defense is a problem that we can solve in a relatively short time span. Finding life in the universe maybe we'll do that in my lifetime. Maybe fingers crossed. But I think exploring worlds, that is a longer-term thing. And if we go out to our even crazier stretch goals, knowing the cosmos and our place within it, that is a journey for all of humanity and every living creature for at infinitum.

Bill Nye: Yes, there you go.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Whereas figuring out whether or not there's something near us, we're going to need to monitor and track and characterize all of these near-Earth asteroids. And we've done a pretty good job so far, but primarily because a lot of the work that we've done as an organization, we've been empowering people through the Shoemaker NEO Grant program, but also NEO Surveyor as a spacecraft, as an example, so that we can save humanity and all the life on this planet that might not have happened without us literally.

Bill Nye: And all life on the planet.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: No big deal.

Bill Nye: Yeah, exactly. Could there be higher stakes?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah.

Bill Nye: So, Sarah, you're doing this good work of raising awareness of this-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I had a wonderful time actually this year, finally getting to go to the Day of Action in person.

Bill Nye: Oh God, that's cool, isn't it? Everybody from around the world it's a US-based thing. But we had several or a few people from Canada who get a lot out of it and talk about the Canadian space program.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Being there in person and going with all of the people, seeing the impact that it had on the people in Congress was really motivational for me because I could see that these in-person conversations change their minds in ways that sending letters might not necessarily, even though we've still changed a lot with the letters. I think our members have sent, it's something like more than half a million letters to Congress.

Bill Nye: Oh yeah. So no, really over the years, Europa, I was there in 2013, the US Congress talking about that. And that was before we had as sophisticated a coordinated effort that we have now with Casey and Jack, our Washington, D.C., and political analyst guys. So everybody, this not getting hit with an asteroid is a big thing. We award grants for people who have specially sophisticated telescopes to look for asteroids.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: The things that we've learned, not just about like Earth-like worlds, but what's really been shocking to me in recent decades is water worlds, worlds like Europa and Enceladus with these under these subsurface liquid water oceans that are sustaining all the way until now. I mean, it is quite conceivable that most of the life in the universe-

Bill Nye: Conceivable, see what she did there? Conceivable.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's possible that most of the life in the universe doesn't exist on worlds like ours. It might be under the cracked-

Bill Nye: Ice.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ...icy surface on these. How would they even... They wouldn't even be able to know that there were stars beyond that ice. How many creatures are living on these worlds not knowing?

Bill Nye: Or are there Europanian fish explorers that have drilled a hole or gone to the fissures, the cracks in the ice, and seen the stars and they come back down from above the surface? You wouldn't believe. I don't believe you. You're crazy.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I just imagine a day where humanity actually walks on these other worlds and maybe we send humans to Mars someday. We'll be right back with the rest of my interview with Bill Nye after the short break.

Bill Nye: Greetings, Bill Nye here. 2024 was another great year for The Planetary Society, thanks to support from people like you. This year, we celebrated the natural wonders of space with our Eclipse-O-Rama event in the Texas Hill country. Hundreds of us, members from around the world gathered to witness totality. We also held a Search For Life Symposium at our headquarters here in Pasadena and had experts come together to share their research and ideas about life in the universe. And finally, after more than 10 years of advocacy efforts, the Europa Clipper mission is launched and on its way to the Jupiter system. With your continued support, we can keep our work going strong into 2025. When you make a gift today, it will be matched up to $100,000 thanks to a special match and challenge from a very generous Planetary Society member. Your contribution, especially when doubled is critical to expanding our mission. Now's the time to make a difference before year's end at Planetary.org/Planetary Fund. As a supporter of The Planetary Society, you make space exploration a reality. Thank you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We do have to go back to Mars and get the Mars sample return back, which is something we're super working on right now.

Bill Nye: Yeah, we are super working on. You guys here's an example of science crossing paths with politics. It was presumed that if you took these samples and put them in these cool tubes, somebody would show up and bring them back. But it turns out there wasn't really a plan to bring them back exactly. There wasn't exactly a plan exactly to exactly bring them back. And now NASA and these guys and gals are backtracking, well, what we're going to do is think out of the box and to come up with a whole new... You guys, it's going to cost reckoned in US dollars, billions. Just let's do it. Let's bring these things back and so I started to mumble about this. Martian rocks land here often enough. Mars gets hit with an asteroidal object. Stuff gets tossed into space, and it falls to Earth on these so-called Hohmann orbits.

Mars is orbiting the sun. So are we. And these rocks fall. Whoa, whoa [inaudible 00:28:27] space as I like to say, there's no sound. And they land on Earth, and the place we find them is Antarctica. I've never been, but I've seen the pictures. So you're walking along in the ice and there's rocks. Where did they come from? The only way they could get there is they came from the sky. It's really an amazing idea and the rocks that make this trip are tough. They've been whacked off the surface of Mars.

They've fallen all the way through outer freaking space, the vacuum of space, and they make it through Earth's atmosphere going at extraordinary speeds burning up, and a part of them still makes it here. It's amazing. But those rocks are different from the rocks that the geologists are collecting. In the Jezero crater on Mars, they are so-called mud rocks. This is a place on Mars that used to be wet. If that area gets hit with an asteroid, they don't get tossed into space. They're not tough enough. It's sand. And so that's where there could be Martian microbes, either at one time in the distant past or maybe under the sand, where it's salty and slushy salt slush, there's something still alive.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I mean, what's all that methane about? I mean all that methane as if it's not like a tiny fraction of parts per million. But still, we have detected things on Mars that really need answers that could be absolutely nothing or could be an indication of present-day extant life on Mars and its-

Bill Nye: Listen to what she's saying, people. Say it again, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's right there.

Bill Nye: Let them hear you outside.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What if we share a common ancestor with life on Mars or even beyond? If we send humans there too quickly before we actually do this science, we might corrupt our own ability to be able to answer these fundamental questions.

Bill Nye: So I am so old. How old are... I was there for survey... I was there. I was here on Earth for Surveyor. Surveyor. So first smash some spacecraft into the moon to get close-up pictures of the moon. Then had these surveyor spacecraft land with disk-like feet, circle feet to assess whether or not the lunar surface was this very feathery light, mass dust, and whatever you tried to land there would just sink like a swamp and disappear. So the surveyor spacecraft were put there. Then astronauts Earth years later drove up to these things in one of the rovers and brought a piece of the surveyor spacecraft back, and it had microbes still alive. And they presumed that these microbes had lived for years on the lunar surface, and perhaps there's something alive.

But then they realized it was just contamination in the Earth lab and so we just don't want to do that on Mars. This is what you're talking about, right? Don't want to go to the interesting places on Mars and contaminate the place in such a way that we couldn't distinguish what we're looking for from what we brought by accident. When you send people, man, it is a dirty business. It is microbes. What are there some million viruses on your face? There's some crazy statistic like that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh, I don't want to think about that.

Bill Nye: Yeah. But they don't kill you. They're part of the deal.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. They're part of me. I mean, honestly, there's some statistic thing. Most of us actually isn't even us. It's just the microorganisms that live inside of us.

Bill Nye: Yeah. More bacteria in your tummy than there are humans on Earth.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We're like a whole universe to those guys. That's wild. Really though. I mean, as we're getting more samples from outer space, we went with many missions at this point to try to recall things down to Earth. We haven't done it with Mars yet, but we totally nailed it with OSIRIS-REx recently. Another mission that we not only advocated for but also Asteroid Bennu was named in a contest because of us.

Bill Nye: I saw Mike Puzio. Did I tell you this?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: No.

Bill Nye: So I was at University of North Carolina. He comes up to me, he's weird with the beard now. He looks like a grad student and he's a mechanical engineer.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's amazing.

Bill Nye: And he said, University of North Carolina getting his degree. And this is the guy, everybody in third grade who thought deeply about Egyptian mythology and asteroids and the spacecraft, the artist's rendering of the spacecraft, and thought it looked like a bird. And this Egyptian bird, the mythic or theological mythological bird Bennu, he says is a pretty good name. So the asteroid is named by a guy in third grade who's now in college getting a degree because of The Planetary Society and support from listeners like you. So thank you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I've also spoken to other people like Abby Fraeman who are part of our-

Bill Nye: Abby Frae... Oh man, love. Who doesn't love her?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh my gosh. The Red Rover Goes to Mars program. There have been these moments throughout TPS history where we've helped out with programs, kids get involved, and then years later they're leading missions. They're doing that work because of that impact we had on them. It's wonderful to see that legacy and now that we have The Planetary Academy for kids, I'm really hoping that we have a whole new generation that's been inspired by that.

Bill Nye: So doing the Science Guy show a hundred years ago, back in the 1900s, we had this very compelling research that 10 years old is as old as you can be to get the so-called lifelong passion for science. And that's the idea of Planetary Academy. If it's not 10, it's 12 or it's eight, or it's one of these numbers.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Everyone's different.

Bill Nye: It's not 35 and so we want to get young people excited about space exploration or just as you and I were back, back, back in the day looking at Saturn through a telescope made of a concrete casting tube.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I was one of those kids. I watched your show religiously as a child.

Bill Nye: I love you man, woman.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But also my mom was a school teacher. And I think inadvertently, because I don't know how this happened, but your VHS tapes... I'll date myself here. Your VHS tapes were in every single elementary school and middle school across the United States. You were basically the substitute teacher for almost every tired teacher out there.

Bill Nye: Apparently, I still am, and it is an honor, and I try to get it you all. When I meet people... I was in Bayeuz, France, which is back east someplace. I think it's in another country. And this guy came up to me speaking French English, said he loved the show. He watched the show. He learned English from watching the show. What? Whoa, people from Portugal, people from Brazil have come up to me, let alone people from exotic places like Milwaukee or what have you. And so I put my heart and soul into that thing. And The Planetary Society had a tremendous influence on the scripting and performance of that show.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Really?

Bill Nye: Oh, man. Because of my tradition with The Planetary Society. Planetary science is the study of the cosmos, astronomy, and planets. So many of you listening may have taken Earth science in let's say US middle school or in UK middle school. And in Earth science, you might've studied the ancient dinosaurs. Well, I organized the show as the head writer. I organized the show, especially with a guy, he's still a dear friend, Ian Saunders. We organized the show so that study of ancient dinosaurs was life science. The study of astronomy and climate change and atmospheres and geology and geochemistry is all planetary science, but astronomy and Earth science, and atmospheric science were all grouped for me in planetary science, which would be the study of everything in the cosmos and then Earth. So three major topics: life science, physical science, planetary science, then each divided twice, general biology humans, chemistry, physics, all astronomical bodies, Earth. So it is The Planetary Society influenced the Science Guy show?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: See, that's one more example of the ways that The Planetary Society impacted my childhood and my life path without me even knowing it.

Bill Nye: Cue this Twilight Zone music, Twilight Zone, astronomical reference, Planetary Science reference.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: No really, we could be here for the next year just going over the things that The Planetary Society has done-

Bill Nye: Well, you should have a podcast, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I should have a podcast.

Bill Nye: You should get guests on, talk about stuff.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And thankfully, we are planning out a lot of content over the next year so we can celebrate this 45th anniversary. But it's also a moment for us, not just to reflect on what we've done, but to look at our goals going forward because we do this thing every few years. We come up with a new strategic framework, the things that we're going to be working on in the coming years. What are you hoping that we are going to try to do in this next little period?

Bill Nye: Well, so we're arguing, discussing the mission once again. And you guys, as I'll tell you, as the head writer of the Science Guy show, you got to agree... We must agree on every word. And people go, that's just wordsmithing. No, it's not just wordsmithing. It's the point. So when I say to people on the elevator before the door closes, we're the world's largest independent space interest organization advancing space, science, and exploration, [inaudible 00:38:03].

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Nailed it.

Bill Nye: Yeah, but it's a lot to take in. But what we want to do at The Planetary Society, we exist for the sake of humankind. We want to make the world better. We want the world for humans to be better. That really is the big thing and I'm not sure you get that from that long-winded elevator speech. Most independent space... Largest space interest organization advancing space, science, and exploration. Should it be making the world better through exploration of planets? Should it be we are dedicated to the scientific exploration of the cosmos? If you say scientific is that exclusive? Does that mean only scientists or scientifically inclined, or does it mean everybody? So this is a really important thing we're talking about for the next five years, but specifically for me, want to have some more missions, want to go back to Venus, see what the deal is at Venus.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh man, I really hope VERITAS and DAVINCI end up where they need to.

Bill Nye: Hope is not a plan. So we're working on it. Specifically, we want to go back to Venus, we want to go to the South Pole of the moon and see what the deal is with this ice. I presumed having taken chemistry and physics and just screwing around with dry ice myself as a kid, I presumed that if you had ice in the icy vacuum, the bitter cold vacuum of space, it would just evaporate. There wouldn't be any ice.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Or sublime, I guess.

Bill Nye: Yeah, sublime. Yeah. Change from a solid to a gas without being a liquid. But there's something going on with the regolith, the whatever the moon is made of, and ice that's somehow osculating with the rock. And then the other thing, I really want to be involved with Apophis. These are specific things over the next five years, but generally want to refine our mission, refine our purpose. Why do we come to work, Sarah? What is it we do here? We're trying to make the world better for all of humanity. It's not bad.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's not bad. Of all the topics that we could unite on as a human species.

Bill Nye: A group of tribes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: As a group of tribes, as citizens of Earth. Right?

Bill Nye: There you go.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: This is one of those things that we can work together on that is truly a peaceful endeavor that has nothing but benefits for us. I think what The Planetary Society does is very hope building because there are a few things that we can organize around that are just that fundamental and beautiful and meaningful to who we are as people.

Bill Nye: Right on. Right on. You should have a podcast. Yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well also thank you for enabling me to do this kind of work. It's the dream of almost every science educator to have a platform like this. And here I am stepping into this legacy, which you yourself stepped into. This thing that has been built from our founders all the way up through the work of so many dedicated people. And now I get to share what I love every day with people around the world listening to this show. And they get to share what they love with people because of what we do, and they feed back into it through their advocacy and their donations. It is a beautiful thing and I can't even imagine what the world would be like without The Planetary Society. There's some bizarro world in the multiverse where we never got formed and Starfleet's never going to happen. Well, we'll say that. But also we wouldn't know anything about what's going on with these worlds and our connection to them.

Bill Nye: So you just mentioned Starfleet, I got to say on our board of directors is Robert Picardo, who plays the doctor on the new Star Trek franchise, Starfleet Academy, and they're shooting it right now. I saw him this weekend. He was here for the board meeting.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's what he was doing. We're going to do an interview in the future. So that's what he was working on.

Bill Nye: But I mentioned this, it's not irrelevant everybody. Star Trek has affected you no matter where you are on Earth. This idea that Gene Roddenberry had and Gene Roddenberry and Sagan and Bruce Murray and Louis Friedman were all colleagues. Gene Roddenberry's a storyteller. The other guys were scientists and an engineer. This optimistic view of the future through science. That's what Star Trek is about and we have a letter here when you come to Planetary Society headquarters from Gene Roddenberry, it's in support. Love you, Carl, and so on and so on, it's because these guys shared this vision of a better future for humanity through science, planetary exploration. It's pretty cool. It really is something to be part of. Sarah, this has been a delight. Thank you so much.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: This has been so much fun and here's to the next 45 years.

Bill Nye: Right on. Let's change the worlds.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Let's do it.

Bill Nye: Happy 2025 as reckoned by the Gregorian calendar.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Thanks, Bill. We'll be celebrating our 45th anniversary all year, so keep an eye out for upcoming content and events. Thank you for coming on this journey with us and for all of the wonderful science technology and discoveries that you've helped enable. Now we turn to Dr. Bruce Betts, our chief scientist for What's Up. Hey Bruce. Happy New Year.

Bruce Betts: Happy New Year.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Happy New Year. Fireworks.

Bruce Betts: And happy anniversary.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know it feels so cool to be with an organization at this point in its history. I mean, 45 years is a long time, and fingers crossed I'll be here for the 50th.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, that seems like a good bet.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Maybe. Honestly, y'all are going to have to shoot me into the sun to get rid of me.

Bruce Betts: That turns out to be incredibly difficult. It is shockingly hard to get to the sun because of the velocity we'll have to get rid of that you currently have on Earth, so you're probably safe, but we'll talk about that over the next five years.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, hey, we invest the money in shooting Sarah into the sun to get rid of her, and now we know how to do it for other spacecraft. So knock-on effects.

Bruce Betts: Why am I the one that finds this a disturbing prospect?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I don't know. Maybe because you like me, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: No, I think it's a waste of resources. Oh yeah, I like you too. Oh yeah, 2025. The year of being nice. Okay.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Is that your New Year's resolution to be nice?

Bruce Betts: Yeah, I think I've already had a... I've strayed over the line a few times and it's barely begun.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But how long have you been working at The Planetary Society? You've seen a lot of the history of this organization.

Bruce Betts: Hey, have I seen a lot of history. Let's just say when I came here, we were sending out our random space facts by chiseling into stone. No, that is not true. I began working, so to speak, for The Planetary Society, doing slave labor when I was a graduate student at Caltech because my thesis advisor was Bruce Murray, one of the co-founders of The Planetary Society. So I did things. I did things, I can't talk about them. And then I went off and did a little science career in NASA headquarters tour, and then got the call from the gang and they said, "Hey, you want to come on out and do this?" And I said, "Yeah."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What was your original job title? Were you chief scientist to begin with or did that change?

Bruce Betts: Minion.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Minion.

Bruce Betts: My job title when I came to The Planetary Society was director of projects.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Director of projects.

Bruce Betts: And then at a later time, I became the director of science and technology, and then I became the chief scientist. And-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Those are all cool titles, man.

Bruce Betts: They are cool titles they make for a nice collection of business cards.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What would you say over the years that you've worked at Planetary Society is your favorite thing that changed about the organization?

Bruce Betts: I have to actually be thoughtful. Ow. It hurts.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Sorry.

Bruce Betts: I mean, I hate to say this because people might think I'm like them, but the team is really... The team as a whole it really functions smoothly now compared to some of the things that happened in the early years of big conflicting personalities that still accomplish things, but it was less pleasant to get there. And so it's nice just we have a lot of really enthusiastic, positive people like you, Sarah, and everyone's working together and pushing forward and doing great stuff. I think there also is a much greater sense of planning, coordination, all that stuff that you're supposed to do when you're a business that grows and gets older and it helps you work more efficiently. So as much as I may complain internally, just don't let anyone else listen to this podcast who works with The Planetary Society. It's a great team. Good planning, good management, good stuff.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's a weird thing to work at a job where I feel genuinely happy to see everyone every day. Even you, Bruce. But honestly, this is the best team I've ever worked with.

Bruce Betts: So anyway, it's been a long and wonderful voyage, and it's like any job, you get frustrated by the details and when I have to fight with other bureaucracies besides ours. But overall, it's what I... It's nice. I like it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right. We're so lucky to get to be here just-

Bruce Betts: And again, I will never say this again because officially I hate it. I hate everyone. Go away.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I promise I won't tell everyone that you love them, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Oh, oh, oh, oh, come on. Let's not go that far.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: All right. So it's-

Bruce Betts: All right. Onto the first of the new year, first of 2025. So I enjoy this. So Saturn with its gazillion moons, most of them tiny weirdos. They've broken them into different groups. And this Norse group named after Norse language, Norse mythology, and named... Well, we'll get back to the naming. It's a large group of... They're all regular irregular satellites. I'm sorry, retrograde irregular satellites, which is how I'm sometimes described. They go really far out. They're really all sorts of inclinations. They're wacky, they're tiny and they're crazy but what I find particularly amusing is the Norse group, which the naming convention set up by the IAU is named after Norse mythology, mostly giants, the largest of the Norse group, Phoebe.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Phoebe?

Bruce Betts: Which comes from Greek mythology.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, that's right out.

Bruce Betts: I mean, it makes sense because it was discovered long before the other tiny ones were, and they hadn't set up the convention, but it confused me. When I read and the largest of the Norse group is Phoebe. I was like, Phoebe, how can Phoebe possibly be Norse? They actually had a bunch of names suggested by the public not too long ago with more Norse giants. So there you go.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's cool and pertinent too, because now that it's the first of the year, the quasi-moon naming contest that I've been involved in is finally closed and that means a name shall be selected. I cannot wait.

Bruce Betts: That's cool.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Cannot wait to see who wins.

Bruce Betts: That's cool. Oh, speaking of names, I do want to tie it to last year I wanted a connective tissue between the ears. Ymir, that we talked about last year is the second-largest Norse group moon. Ymir. Norse mythology is an ancestor of all of Jotunns or oh, the frost giants. Yeah. Yeah. It's just a frost giant-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What is the word for that? Jotunn, Jotnar or something like that.

Bruce Betts: Jotnar there we go. Thank you. It's like I should remember that I live in various fantasy worlds.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, I learned that from a video game called Smite, which is also how I learned to pronounce Chang'e that mission from the Chinese Space Agency.

Bruce Betts: Well, you go along with what I say. Video games are very educational.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Really though. It's true.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody go out there and look up at night sky, and think about what your big video game obsession for 2025 is going to be or will there be multiple, as I'm sure Sarah and I will both have. Thank you and good night.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with Emily Calandrelli, the Space Gal, who recently became the 100th woman to go to space. If you love the show, you can get Planetary Radio T-shirts at Planetary.org/shop, along with lots of other cool spacey merchandise. Help others discover the passion, beauty, and joy of space science and exploration by leaving a review or a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day but helps other curious minds find their place in space through Planetary Radio. You can also send us your space thoughts, questions, and poetry at our email, at [email protected]. Or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the planetary radio space in our member community app.

Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by our members from all over the world. You can join us and help us shape the next 45 years of space exploration at Planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor, Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. And until next week, Ad Astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth