Planetary Radio • Feb 12, 2025

Near-Earth Asteroid 2024 YR4 and NASA under a new administration

On This Episode

Finn Burridge

Science Communicator at Royal Observatory Greenwich

Kate Howells

Public Education Specialist for The Planetary Society

Casey Dreier

Chief of Space Policy for The Planetary Society

Jack Kiraly

Director of Government Relations for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

The internet is buzzing about Asteroid 2024 YR4, currently ranked as the highest-threat asteroid in our skies. But is it really cause for concern? Our Public Education Specialist, Kate Howells, breaks down the facts. Then, we shift from potential impacts to stunning space imagery as Finn Burridge from the Royal Observatory Greenwich shares how astrophotographers worldwide can participate in the Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition. Finally, our space policy experts, Casey Dreier and Jack Kiraly, discuss how the new Trump administration has impacted NASA in its first weeks. Stick around for What’s Up with Bruce Betts, as he explains how we assess asteroid threats using the Torino Impact Hazard Scale.

This is how we work for space in Washington D.C. Participants share their experiences from the 2023 Day of Action.

Related Links

- Should you be worried about Asteroid 2024 YR4?

- An Asteroid Has a 1-in-63 Chance of Hitting Earth in 2032—Here’s What That Means

- Astronomy Photographer of the Year | Royal Museums Greenwich

- Astronomy Photographer of the Year past winners | Royal Museums Greenwich

- Royal Observatory Greenwich

- Planetary Radio: The Royal Observatory, Greenwich and the Quest for Longitude

- Space Recommendations for the Second Trump Administration

- The Day of Action

- Fighting for VIPER on Capitol Hill

- Subscribe to the monthly Space Advocate newsletter

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

We've got a potentially hazardous asteroid, a beautiful astrophotography contest, and a new U.S. presidential administration, this week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society, with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. The internet is all in a tizzy over the newly discovered Asteroid 2024 YR4. It's currently the highest threat level posed by an asteroid, but should you worry? Our public education specialist, Kate Howells, gives us the details. Then Finn Burridge, science communicator at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, joins us to share how space imagers worldwide can participate in their Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition. From the skies, we turn our eyes to the changing political winds in the United States, as Casey Dreier and Jack Kiraly, our space policy team here at The Planetary Society, discuss how the first weeks of the new Trump administration have impacted NASA.

We'll close out with What's Up with Bruce Betts, as he discusses the Torino impact hazard scale and how we determine the threat level posed by near-Earth objects. If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it.

We begin with Asteroid 2024 YR4, a recently discovered near-Earth asteroid that's making the headlines. Don't panic, but there is a small chance that it could hit Earth on December 22nd, 2032. Kate Howells, our public education specialist, joins us from Canada to discuss her new article, should you be worried about Asteroid 2024 YR4? Hey, Kate.

Kate Howells: Hi, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, this is a fun topic to bring you on for. I don't want anyone to panic, but we do have a really interesting asteroid that's just been detected. So, you got the opportunity to write about this as quickly as possible, because I know it really worried people. So, should we be worried about Asteroid 2024 YR4?

Kate Howells:

So, the short answer is no. The longer answer is just a little bit more than you worry about asteroids generally, which shouldn't be very much. So, the thing that's different about 2024 YR4, the very snappily named asteroid, is that it has about a 1% chance of colliding with Earth, and that is a lot higher than we usually get. Most asteroids that we detect have a 0% chance of colliding with Earth. So, this one is unusual in that there's even a slight possibility that it'll hit us. Now again, this is specifically talking about asteroids in this sort of size, like little meteorites obviously hit the Earth and we see those as shooting stars, but asteroids that are bigger than that, very, very, very infrequently are found to be on a collision course with us.

So this one is unusual, but I still say don't worry because we are going to be tracking it, we are going to be refining our understanding of its trajectory through space and where exactly it will be in space when it comes close to the Earth. And it's extremely likely that as we get more data we will discover that no, it is not going to hit us. It'll just pass close to us.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What's its expected date of closest approach to Earth?

Kate Howells: It is expected to pass close to Earth on December 22nd, 2032. So, we've got a fair bit of time ahead of us to track it, and if in the worst case scenario we find that it is going to be on a collision course with Earth, we've got a lot of time to prepare something to deflect it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How big is this object?

Kate Howells: Right now it looks like it's about somewhere between 40 to 100 meters in diameter, so that's about 130 to 330 feet. But again, follow up measurements are going to help get that number a little bit more precise.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But either way, we're not talking about a world destroying, like Chicxulub dinosaur event. It's probably something smaller but could still create some devastation locally if it did hit.

Kate Howells: Yeah, absolutely. You don't want something this big hitting the Earth. If it hit in water, it could create tsunamis. If it exploded over the air, like the Chelyabinsk event where that was in Russia in the 2010s, and all these windows exploded in buildings throughout the whole city, that kind of thing could happen. Or if it did actually strike the ground, it would create an impact crater and an explosion. So, none of these are things that you want. It's not going to wipe out the entire planet or kill 90% of the species that exist on the Earth like previous impacts may have, but it's still something you really want to avoid. So, what is important here is to continue observing this object and get all of those follow-up measurements to really know its trajectory and its size.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We only detected this because of its last close approach by Earth, so it's actually swinging by us pretty regularly.

Kate Howells: Yeah, I mean, space is very full of asteroids. I mean, as much as technically it's very empty and everything's very far apart, there are a lot of asteroids out there and they swing past Earth as they go around the sun or they are on the opposite side of the sun from Earth as they swing past the plane of our orbit. So, we do get a lot of close passes, but things that are looking to pass this closely are very rare.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How does this compare to something like Apophis that's going to be flying by in 2029? So, we've got everyone gearing up for that big moment and this object is coming closer to us than our geostationary satellites, but now we've got another one we've got to worry about.

Kate Howells: Well, yeah, Apophis, when we first discovered it, we weren't sure if it was going to hit Earth or not. So, it actually is the only asteroid that's ever had a higher rating on the Torino impact hazard scale, which is what scientists used to rank how likely something is to hit Earth and be devastatingly destructive. So Apophis, when it was discovered in 2004, had a rating of 4, whereas 2024 YR4 has a rating that could be as high as 3. So, both of those are significant, keep an eye on these things kind of ratings, but then Apophis, as we studied it more, it went down to zero. So, we now know that it's not going to hit us. It's going to come really close, which is actually great for asteroid science because we can study it as it passes close to us. We don't have to go all the way out to deep space where we often go visit asteroids, we'll actually have one coming close by. So, perhaps 2024 YR4 will have a similar outcome where we'll find out that it's going to pass close enough that we can study it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And that's cool because we already have so many missions that are gearing up between the United States and European Space Agency to try to check out Apophis, perhaps we could repurpose some of that for 2024 YR4 if it gets that close. Fingers crossed it doesn't though, but-

Kate Howells: Yeah, absolutely. The more we do this kind of thing, the more we develop the technology to be able to go study an asteroid up close, that kind of thing, the better prepared we are to do it again if we get another opportunity. So, it's our job to put these things into context and explain how people should actually interpret this news, and what they should think about it and whether they should be worried. And in this case, it is this middle ground of don't ignore this, we don't want the world scientists to ignore this, but average people, don't let this disrupt your life. Don't lose any sleep over it. We interviewed Heidi Hammel, the vice president of our board of directors, who's also a planetary scientist, we asked her about this asteroid because she and her colleagues are involved in tracking it, conducting observations to better understand it. And she said very clearly, "Your danger is far higher to have a car crash, so wear your seatbelt. That's something you should actually worry about, this is not."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, it's good news and a good opportunity for science. And one more example of just how wonderfully our system right now of people around the world trying to track and detect asteroids is working, and it's about to get so much better with instruments like NEO Surveyor in space. So, it's making me feel a lot safer knowing just how many of these objects we found and that in all of that, all that space, all those rocks, this is the one that we have to be the most worried about and we don't really have to worry that much.

Kate Howells: Exactly. Yeah, it's always good to keep an eye on the skies and make sure that we're prepared to find things that could be dangerous, and deal with them if they are dangerous. So, it's so important to continue funding planetary defense efforts around the world, and supporting things like the International Asteroid Warning Network that helped coordinate all of that. But yes, I'm not going to be freaking out yet about this one.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, not a don't look up situation yet.

Kate Howells: Not yet, thank goodness.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks for sharing this with us, Kate, and hopefully we've made some people feel a little less scared about space rocks.

Kate Howells: Yes. If you ever hear anything on the news that frightens you about asteroids, just go to Planetary.org and if it's a real threat we'll have information on it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, we have your back. Thanks, Kate.

Kate Howells: Thanks, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Some people image the sky to protect us from near-Earth objects, but others do it strictly for the pretty pictures. There are many ways to share and enjoy astrophotography, but one of my favorite ways is through the Royal Observatory Greenwich's Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition. As the name suggests, the Royal Observatory Greenwich is located in Greenwich Park in London, UK. It's the home of Greenwich Mean Time, it's a great spot if you want to get a selfie standing on the Prime Meridian, right before you go into London's only planetarium. The images that come out of this competition every year absolutely blow my mind, and entries are now open. Whether you like taking space pictures or simply marveling at the beauty of space, you'll want to keep this one on your radar. Finn Burridge, science communicator at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, joins us now to share how you can participate. Hey, Finn. Thanks for joining me-

Finn Burridge: Hello. Hi, no worries. It's great to join you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'm so glad to speak with you, because there are so many wonderful astrophotographers around the world and so many wonderful ways to get out that imagery. But each year, the contest I look forward to the most is the one that you guys hold. How did this all begin?

Finn Burridge: Well, it's a long-running competition and it began way back in 2009, so we have been running it for a long time now. And we wanted to celebrate this, what was a hobby, and this passion that many people have to photograph the nice sky. Of course, back 2009, technology is not what it was today, and people had to go the drive out right into the sticks and were really, really dark trying to get these fantastic images of galaxies back when the best images were space telescopes. You had to wait for Hubble or another space telescope to come out and publish some of the best. And we wanted to celebrate that people could really take images that could rival some of these space telescopes if you put in the time, if you put in the hours. And now, here we are 16 years later, and some of the images coming out of the competitions now are just absolutely incredible. And I think it's just a really joyful way of celebrating astronomy.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I agree, and I love that you break it out into so many different topics of different things that you can take images of, because there's so much different technical skill depending on whether or not you're imaging the sun versus imaging a nebulae. There's a wide skill variety there.

Finn Burridge: Yeah. I mean, we thought it was right really to break it into different categories to respect the different techniques, skills that people have. It's very, very different to go out and take a picture of a deep sky galaxy somewhere where it does have to be dark, you've got to have a big telescope, lots of collecting power, over let's say the aurora, where you need to go somewhere really far north. It's not necessarily about a big telescope, and it's more about your artistic expression. You get a greater [inaudible 00:12:18] have you got a good foreground? And there are lots of different categories now which celebrate all these different kind of techniques, genres, if you like, of astrophotography. My personal favorite is probably galaxies, it's an area I studied and I think it's amazing now the kind of images that we get from galaxies. But yeah, lots of talent in all the categories today.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And the contest is open to people from all around the world. How far-reaching have your submissions been?

Finn Burridge: Well, last year we had 58 countries, people from 58 countries submit. So, we get people from all around the world. It's a real international call out, more and more people getting submissions every year. We had well over 3,000 entries this year, and we're hoping for more this year. And I think that brings a real joy to the competition, because you get places, different cultures you get different people celebrate in parts of the sky that mean a lot to them. And it's wonderful to see from around the world how people change their taste, if you like. This year, interestingly, a lot of our submissions from China, they were very bright. It's the theme this year to have very, very bright, very foregrounds, really colorful images, whereas in different places around the world they prefer more muted tones, shall we say. And it's really interesting to see how different places have different tastes for the sky.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It'd be really interesting to look through all the images based on where they come from and see those commonalities, and try to pick out themes. That's really cool.

Finn Burridge: Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What is the process of trying to whittle down these images to find your final winners? Because that's a lot of images.

Finn Burridge:

It's tricky, it's tricky. So, we have a team of real expert judges, and they do the final cut, if you like. And then inside the museum, myself included, we have a larger team of astronomers who shortlist. So, we might get, for some of the categories like stars and Nebula, hundreds and hundreds of submissions, and we have to get it down to around about 15 to 20 before we take it to final judges. And it really is a process of have they got the technical skill? Is the image beautifully crafted? Has it got the wow factors? Is it something we haven't seen before? All of these things can contribute to whether an image will make the shortlist or not. And it is tricky, it takes two or three weeks to get the shortlist complete as we all pull our minds together, all of us looking at a category each, and then we come together and cross-reference each other to make sure that we're not missing a brilliant image, or one's person's taste hasn't dominated one of the categories.

And then once the shortlist is complete, we'll pass that to the final judges who will decide on the winner. And I don't envy that position, because by the time you get to 12 images you're splitting hairs, because some of these images that we get now are such high quality it's really, really tough to pick the final image, unless you get a brilliant one that just stands out above the rest. But that's sort of the process. We have a shortlisting process, weeks and weeks of going through these hundreds of submissions, and then a final judging panel to do the winners.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, I was recently on a naming panel to try to help name a quasi-moon of Earth, very similar process. And I tell you, it is so hard to pick a winner in the end, but eventually you do. What happens when a person wins this contest?

Finn Burridge: The overall winner obviously wins the grand prize. So, they get a bit of a monetary reward, and they have the joy and pride of having it displayed in our gallery alongside each category winner as well. So every year, once the winners are announced, we'll have an award ceremony. So, the winner will be invited to accept the prize. We have a short film made about, if we can, about them and their process, and how they created their masterpiece. And then, all the winners will have their photo on display for the rest of the year in our APY Gallery in London in the National Maritime Museum for members of the public to come and see. So, you have your photo displayed publicly.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And I want to share as well, if people want to have a little bit of this in their own home, you do produce a full calendar of all the winning images as well. And that's one of my favorite ways to have that in my home.

Finn Burridge: Yeah, we do. It's great. At the museum, obviously we have every edition of the book that has been made, and that has all the shortlists in as well. So, even if you didn't make runner up, if you're on the shortlist you get into the book, and it's a great way to see how the competition has evolved over time.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's beautiful. So, how do people actually submit their images to you?

Finn Burridge:

So, if you head to our website, Royal Museums Greenwich Astrophotographer of the Year 2025, you'll find on there a link to submit your images alongside the rule set. So, each category has its own rule sets. Some for example, like the Annie Maunder Prize, we've opened it up this year and we've made it even more creative. We've relaxed some of the tools that we have previously not allowed, now we want as much creativity as possible. So for example, this year we're allowing AI editing, we have to use real data. So, this is a really interesting category actually, I should probably speak about it. And we want people to take real astronomy data and make something amazing out of it. So be as artistic, be as creative as you like.

This year's winner was fantastic actually. We had a person who took weather satellite data of the Earth from space, and flipped the colors on it to make it look like an exoplanet, and it was how would an alien see our world? And using the real weather data that shows our changing climate, he created a exoplanet under threat to raise awareness of our challenges that we face on Earth. That was a really interesting submission, and we want more like that. It's a really interesting category, so we want people to head on over to the website, read those rules, see what you're allowed to submit, and then submit your images.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's going to be fascinating to see what people come up with with these new tools. Things are changing so rapidly, but that is also one of my favorite categories, turning astrophotography into, it's already an art, but this more profound, more artistic way of trying to interpret the data. It's beautiful. When do people actually find out whether they win? When can we see the winning images?

Finn Burridge: So, this year it will be towards the end of September when we'll announce the winner publicly, the winner themselves may find out just before then if they are invited. If you get an overall winning category, you'll find out slightly before so that you can come to the award ceremony of course, but it's only a few days before the actual public announcement at the end of September.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh, wow. Oh, and I didn't ask, when's the deadline? I think we only have a little bit left.

Finn Burridge: So yeah, the deadline for this year is the 3rd of March, so we don't have too long, less than a month if you want to submit your images. So, if you do have any, or if you want to go out and take any in the next few days, I mean, we've still got a planetary parade in the sky at the minute, which is really, really cool so there's still time. Get your images in by the 3rd of March.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Beautiful. Well, I know that this year's images are going to blow my mind all over again. I can't wait for all of our listeners to have an opportunity to look at these. If you haven't been checking out this contest, I highly encourage it because I've been doing it for over a decade, and every year it brings me such joy. So, thank you for putting this on. I know it is a massive undertaking, but from me to you it's a beautiful contest, and I think it is absolutely one of my favorites of the year.

Finn Burridge: Thank you very much, and it brings us joy as well. It's a really fun project to be involved with, seeing what people can come up with. And to be honest, it's a joy going through all of the hundreds of images that get submitted. So many of them could make the final short list, it is a lot of fun for us to put on.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks so much and good luck on the judging-

Finn Burridge: Thank you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... and good luck to everyone submitting your images.

Finn Burridge: Yeah, good luck to everybody.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: As always, I'll drop a link for the contest on the webpage for this episode of Planetary Radio. Our perspective on space isn't just about what we see, it's about the policies that determine what and how we explore next. There's much to discuss in space politics as the Trump administration returns to the White House. The Planetary Society is a nonprofit, non-partisan organization with members all around the world. For 45 years, we've worked with U.S. legislators and presidents to help shape the future of space exploration. Casey Dreier, our chief of space policy, and Jack Kiraly, our director of government relations, join us now to discuss this moment in space policy and what you can do to help support NASA's programs and workers. Hi, Jack and Casey.

Jack Kiraly: Hey, Sarah.

Casey Dreier: Hi, Sarah. How's it going?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: All right, there's been a lot going on in space policy recently so I wanted to make sure that we took a moment to really talk about what was going on, because I know a lot of people are curious about how things have been going at NASA since Trump and the administration came in recently. So, what have you guys been seeing? What has your week been like?

Casey Dreier: Pretty quiet. Jack, you've been working at all? I've really just been taking it easy.

Jack Kiraly: Yeah, no, really not much to follow on the news.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, Sarah, it's been crazy. I mean, we need to separate out two things I think to talk about space policy in particular, which is there's no distinct new space policy yet. And what we're seeing happen at NASA and within the science agencies, the U.S. government more broadly, is more of a function of these broad sweeping executive orders that the president issued on the first day and then subsequent days. We'll talk about one that was rescinded, but functionally I think it's important to keep in mind that NASA is executing what the White House is directing it to do, and we're seeing the impacts of it pretty quickly. And it's hitting pretty bluntly in terms of how these are being applied, that probably intentional, but it's happening very fast. And that's in this case, somewhat unusual for how government acts and this is what Jack and I have been trying to keep up on.

Jack Kiraly: Yeah, I mean, it's a evolving situation and it's something that is part of why we have organizations like The Planetary Society to keep track of how these things evolve over time and what impacts that might have on space policy. And so yeah, Casey and I have been actively keeping track of all the new information and implementation of that information as it comes out.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. And we can just mention, I mean, so the things that's really hitting NASA that we're seeing, so there's executive directives regarding the concept of DEIA regarding gender, very strong, I think it's fair to say cultural war related issues. And part of those executive orders basically say that federal agencies cannot participate or generally even acknowledge even the terms. And they set very strict and immediate deadlines for when these things had to be taken off of public activities, and also from public websites. And so, what that's actually resulted in, and I'll add too, that they were somewhat vaguely written. Within the orders themselves there's not a clear definition, nor is there a clear bar to clear. And so, I'd say the fairest understanding of what's happening within organizations like NASA is that you have their legal counsel saying, "Okay, these orders say this, we need to err on the side of extra caution." And if there's any doubt, NASA has been essentially just taking down. And what do I mean by taking it down? Well, we've seen websites, some of the Solar System Exploration Virtual Institute has gone down, we've seen the policy directives, NASA's internal policy directives, which included probably statements about diversity and inclusion that the website was gone. We're seeing some grant reporting, grants had been actually encouraged and required to engage on a broader and diverse consequences when they would execute them. NASA has erred on the side of just removing them in total in order to theoretically scrub some of those words out of there. And they claim this is temporary. We have no reason not to believe them yet, this is at the NASA level, but it is hard to say. We don't know, because we don't have that transparency about what needs to be done. And NASA itself may not fully even know that. We just don't know when a lot of these pieces of content will come back.

Jack Kiraly:

Well, it's a good thing to remember that the federal government is very large. NASA itself is of the discretionary budget, not counting mandatory spending, 0.39% of that budget. So, that means that there is still 100% of the budget that needs to implement these executive orders. And so, obviously certain policy decisions that the administration and Congress will be working on in the coming months affect one agency more than another. These are sweeping, and so it's up to those individual agencies to implement what they see as the best definition of that executive action that is requested. And so that is, I think maybe the source of a lot of the confusion that has come out of these is that the implementation is varied based on agency, and as we've seen the White House has gotten involved in clarifying over time what these executive actions mean.

And so, it's the messy nature of government is it is a large institution, multiple large institutions trying to get them all to do one thing is very difficult. It's people. And so, at the end of the day that implementation is taking different forms in different parts of the government, with NASA we're seeing it take this form.

Casey Dreier:

Additionally, I'd say the other things that we've noticed are the NASA has shut down all scientific input panels. These things are called analysis groups and various other technical information groups, and these usually feed into what's called the NASA Advisory Council. They got notices the other week that these were all to suspend meetings until, and this is the standard language, right Jack? Until we can assure compliance with the executive orders. So, these executive orders keep getting issued and keep getting clarified. So, I think that's part of the ongoing uncertainty, to put it nicely about what's going on. But at the end of the day also, NASA is a public agency, and what makes a public agency distinct from a private agency, or a private organization, or private company is that it answers to the public, it has an accountability. So, from a legal point of view the executive has the right in a sense to direct these types of activities broadly. What we need to see regardless though is explanations from NASA, transparency from NASA, standards, communication from NASA, and we're not seeing that much of that.

And I think that's in a sense the more troubling aspect at a very fundamental level for me as an old institutionalist democracy guy, constitutionalist democracy guy, is that at the end of the day they need to be at minimum committing to transparency. And Jack, you were there, that was one of our core recommendations to both the transition team and to the administration itself, is that lean into NASA's unique status as a public agency. And again, what does that mean? It's not just doing things that the private industry won't do, it's doing things that has a fundamental responsibility to the public that private industry just does not by its definition. And so, the lack of transparency, the lack of openness, that to me is the real core of this. I mean, we're only at, as we record this, what two and a half weeks? This could resolve once they settle down. But again, there's other issues out there that we may address here as well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I imagine it's really difficult to be transparent about what your actions are if you're not clear on what actions you should be taking. So, maybe they're trying to take a more measured approach and not be very open about what's happening until they're more clear on what steps they need to take.

Jack Kiraly: Well, and that's, I think, evident from the fact that so much of the notice that has been put out publicly in compliance with the executive orders has been boilerplate. It's taken from the orders themselves or from instruction from the Office of Management and Budget, or from the acting administrator of NASA, Janet Petro. And so, they're keeping the line of communication pretty clear where they can where the information's coming from, and reusing that language so that everyone seems to be as much as possible on the same page about the direction.

Casey Dreier:

Jack, you mentioned something that's important to emphasize is that we still don't have a NASA administrator confirmed by the Senate. And as we record this in early February, Jared Isaacman still doesn't have a schedule on the Senate confirmation process and calendar. Maybe in the next few months is I believe what we're hearing. And so, all of this is happening with an acting a temporary leadership at NASA. And so, there's at the same time a leadership void, there's no confirmed leadership staff there. And so again, they have to be there to execute what the White House says because they are, at the end of the day, as we've always said, an executive agency that is directed by the president. And so, that adds this extra layer of caution I would guess, from their perspective that they are not empowered with any leadership in a sense of they're there as a caretaker.

And so, beyond that there's not a lot of individualistic leadership goals being executed there. We should note a few other things that we've seen that particularly fit into the transparency and openness. One is that apparently there's a new NASA senior advisor to the administrator that has very close ties with Elon Musk, had led human spaceflight activities at SpaceX for many years, and we didn't learn about that except for a report by Eric Berger on Ars Technica. The path forward is similarly uncertain, and this is where I think it's, despite everything I just said, NASA relative to some federal agencies is doing relatively well in the case that they're not being actively dismantled.

Now, we have no idea that will eventually happen to NASA. There's this whole broad talk of cuts and the range of potential outcomes here are very large, and at the moment, because this is happening quickly, this is the hack that's happening. This is moving faster than the speed of bureaucracy to respond to it, but there is response. And I think at the end of the day, despite not vocally saying much at the moment, Congress does have an opportunity to weigh in and that will be coming up. I think we'll see more and more of that in the next few weeks and months.

Jack Kiraly:

And that's, I think you said the key word there, Congress. Three branches of government, and Congress has a very active role to play in both oversight and authorization of the activities of the federal government, and then also the other key function of Congress, appropriation. And so, how the Congress appropriates funds for the remainder of this current fiscal year, we're currently in fiscal year 2025 up through September 30th, we have a deadline coming up March 14th for a continuing resolution, whether the Congress decides to go forward with a full year stopgap funding measure, which would be an unprecedented move in the first year of an administration, or if they are able to put together a full budget for the remaining six months. And then they're going to have to turn right around and start deliberating on fiscal year 2026.

And so, the funding conversation, Congress appropriates these funds a lot of times for very specific purposes, they're going to have a huge say. And both the appropriations committees in the House and the Senate have a very strong voice when it comes to federal spending and oversight, and as do the authorizing committees. We've seen letters from, I believe both chambers to that effect looking for, as Casey, you were describing the improved transparency for what is currently happening across all of government, but then specifically at NASA why certain decisions are being made and if there is any through line directly to the executive orders.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll be right back after the short break.

Jack Kiraly: I'm Jack Kiraly, director of government relations for The Planetary Society. I'm thrilled to announce that registration is now open for The Planetary Society's flagship advocacy event, the Day of Action. Each year we empower Planetary Society members from across the United States to directly champion planetary exploration, planetary defense, and the search for life beyond Earth. Attendees meet face-to-face with legislators and their staff in Washington D.C., to make the case for space exploration and show them why it matters. Research shows that in-person constituent meetings are the most effective way to influence our elected officials, and we need your voice. If you believe in our mission to explore the cosmos, this is your chance to take action. You'll receive comprehensive advocacy training from our expert space policy team, both online and in-person. We'll handle the logistics of scheduling your meetings with your representatives, and you'll also gain access to exclusive events and social gatherings with fellow space advocates. This year's Day of Action takes place on Monday, March 24th, 2025. Don't miss your opportunity to help shape the future of space exploration. Register now at planetary.org/dayofaction.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We can hope that they resolve the budget and figure that out, because we did see what happened last year when it was delayed. It had dire consequences for many of the NASA facilities, they had to have massive layoffs in places like JPL. So, we're really hoping that they do find the funding to do this, but clearly there is a will to try to cut back on funding for many of these grant programs. And you did allude to that earlier, Casey, there was a moment in the first week where the Trump administration proposed to freeze funding for federal programs. It was ultimately retracted, but a lot of science teams were impacted. How did that resolve?

Casey Dreier:

So, they proposed to pause, and at this point this is old news, even though it basically took up two or three full days of Jack and I's life as it was happening. But yeah, I mean, that was a very blunt force proposal. I mean, I guess it was ruled by a judge, it was stayed by a judge as not having the legal authority to do that ultimately, but it caused a lot of disruption, because you pause all grant and federal assistance, just in the NASA world what does that mean? That means science grants to individual scientists who pay their students, who pay their postdocs. It pays the income of National Science Foundation postdocs out of university trying to get their degrees. It funds various research institutions, it funds mission operations, lots of things that are quite useful, and there's a role in our democracy to debate proper levels of funding, but it's not set up to have basically to pull the plug in the middle of it. And that's where the disruption was coming from.

So part of that, Jack was out all day on The Hill, but I was putting together, we analyzed NASA's 40,000 some contracts, and we very quickly were able to put together, in a conservative estimate, that it would impact every state in the country. Some funding goes to every ... And this is just the science and technical grants side of NASA. Over 250 different congressional districts, hundreds and hundreds of millions of dollars of funding were temporarily held up. Thankfully, that got unfrozen. And people, for the moment, assume that that's coming down. Now, there are other issues regarding grant funding for DEA activities, which is now forbidden, and there's issues that people have to stop doing that right away. And then there's potential issues with money, how that was distributed. Again, a lot's happening that we're trying to keep up with.

So Sarah, I think we've touched on all the bad stuff. Can we talk a little about what we're doing? Because we are doing things, and I think that's the ... When it happens very fast like this it can be hard both from the inside to get our message out, and also from if you're sitting on the outside to peer in and see what we're doing. And that's an understandable frustration I think, is that when it's Jack and I are trying to keep up as well and understand what's happening. And Jack, I think it's fair to say we're not the only ones.

Jack Kiraly: It's the entire policy community in D.C. I'm in a number of group chats trying to figure it out. It's the nature of the beast right now. And I will just say, as someone who does this professionally, just an exacerbation of the normal day to day. It's a lot of information, a lot of people involved, a lot of organizations, and this is just an extreme case of a lot of information really quickly. But yeah, we're all operating I think on the same set of information that everyone else is.

Casey Dreier:

Well, part of what makes this unusual, and again, we're trying to stay away from the ... Because we're not a partisan organization, and maybe this is a good time to just mention that we worked really well with the first Trump administration on their space policy, and they had a very smart space policy program. So, this isn't a partisan thing, but I think what's unique this time that makes this more challenging from a policy perspective is that there's no clear policy decision apparatus at work here. It's very centralized, and so very hard to ... You can model systems, when you can do an N equals one million model system you can look at overall impacts much easier than if you had to model one thing very precisely because of all the idiosyncrasies of that one thing and this being a person. So, because the decisions are coming from such a small group of people, the processes of policy in terms of how we set agendas, and discuss, and define things aren't functioning in the same way right now.

And in a sense, that's the rapid adjustment that we and other groups are trying to make to say, "Is there even an input process for these things?" Now again, we're talking about administration here. Congress is still Congress, and Congress is going to act on its schedule. It's just going to be slower. And so, that is still the avenue for public engagement, because at the end of the day the executive only has to go up for election once every four years, and Congress is the check on executive power, executive checks Congress and judicial check, this is our structure of government. And so, if there's this kind of broad frustration, and then I think understandably it's that the system itself is in a strange superposition right now because of this. And so, one of the things that we're going to be doing at the society is more things like this, Sarah, and also for those of you who are members in our member community, part of this is just communication frankly.

And so, we're going to really be trying to up our frequency and access so we can, at minimum, Jack and I can be here to share what are we seeing and how do we interpret this? And we're trying to do the same with other organizations to try to bring information into us, and we can at least talk about what is happening, and give you as listeners and members of The Planetary Society as much information as we can about what we're seeing. The second thing we're going to be doing is really leaning into our values as an organization, and this actually is the strategy we identified last year, which is that we believe that space exploration, and we're just going to focus on space exploration because that's our job as The Planetary Society, space exploration almost requires a broad coalition of people who share a fundamental set of values, curiosity, exploration, ambition, excitement, challenge.

These are nonpartisan and nonpolitical shared values. And so, leaning into and appealing to values, and this is where I keep talking about openness, and transparency, and inclusion, and optimism, we list our values at the organization and that's what we're going to abide by, that we get to represent these values to the people making decisions, and the people in Congress, and our policy makers that we are going to be a voice for those. The next thing we're going to be doing is engaging with other scientists and other organizations as much as we can to both share information and work on shared interests and shared projects. So all of these things are, it's like what we've been doing but more so. And Jack, do you want to add onto that at all in terms of your day-to-day, what you see happening in D.C. for yourself?

Jack Kiraly: Yeah. Well, I'll be returning probably more frequently than before to the hallowed halls of Congress, and working very closely with our partner organizations on shared interests, and also utilizing the groundwork that we laid in the past few years with the Planetary Science Caucus. And that is a great way for us to activate our members, but also activate members of Congress, people that have stood up and said that this is important, and where decisions and opportunities arise where we can advance those key policy priorities and recommendations that align with our values, the caucus is a great mechanism. And so, I guess I can say this on air now that it's official-official, but the caucus is formally refiled with the 119th Congress, we are hitting the ground running already here in D.C. And so, being willing, open and able to accept these opportunities, and to use the platforms that we have to advance that shared vision for the exploration of the cosmos.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: No matter who you are or what your political preference is, space is something that brings all of us together, and this isn't just about us personally and what we do at The Planetary Society, but us facilitating what everybody else who loves space can do to help NASA get the funding that it needs, and to make sure that we can do all these wonderful planetary exploration missions. Thankfully, we've got some wonderful opportunities for people online to help write their members of Congress and hopefully encourage them to join the caucus, but we also have our Day of Action coming up, and I'm happy to announce that all three of us are going to be there. So, how can people who are excited about this join us in Washington, D.C.? Because I'm hearing from you that we're already seeing a record number of people signing up.

Jack Kiraly:

Yeah, it is amazing to see that so many people have signed up so far. I'm looking through the list every day basically, and it's old friends, people that it's their fourth or fifth time doing a Day of Action, but then for about half of them it's their first time ever, which is truly exciting to see. And so, you just have to go to planetary.org/dayofaction and sign up. We take care of organizing your schedule, of getting you to the places where your voice is needed most, providing you with those details and a comprehensive training so that you can turn your passion into legislative action on the Day of Action, March 24th. Planetary.org/dayofaction, it truly is the most impactful thing that our advocacy program has done.

And I hear it every day, literally as of recording this three days ago, an office I have never met with before said, "I remember you from the office I worked in prior to this one because of the Day of Action." And so, this is things that stick around that is part of the institutional memory on Capitol Hill, and really makes an impact that people from all walks of life of all partisan persuasions and ideologies can come together under this common banner of space science and exploration truly makes a difference.

Casey Dreier:

Well said, Jack. And our member community, the only politics at The Planetary Society are space politics, all are welcome if you share these values of wanting to see more space and more space exploration, and execute it efficiently. I think that's the thing when you can look at, and Sarah, I've neglected to mention at the beginning, we do have official recommendations to the new administration now, and one of the things the society emphasizes, that we're not afraid of change. I think change is necessary in a lot of things that NASA is doing, but, but, we have the but, it has to be strategic and it has to be consensus driven. And maybe that's worth mentioning here at the end of the day, orbital mechanics is a merciless, unforgiving entity in that you do not get to choose what congressional term or presidential term that your launch windows, and traverse times, and landing opportunities occur.

Space is big. As our boss Bill says, "There's a lot of space in space," and if you want to do anything functionally, when you start building something new to finding the time to launch it, to getting where it's going, to the time your data gets back or whoever, if it's people going, it usually takes certainly more than two years and almost always more than four years. Space is a relay, and you're handing this, I like this visual now, the space baton from one congressional and White House administration to the next, because you just can't move that fast. And it's not that NASA's inefficient and private industry can move faster, no. This is the alignment of planets that limit this. And so, consensus that this is again, one of our key values that we've talked about, and this is the opportunity to change this ...

Space doesn't have to be another partisan area of fighting, and it so far hasn't been. Space can be this one area of unification, or shared values, or shared exploration because it has to be, and this is what the first Trump administration knew exceedingly well when they designed the Artemis program. They knew that it would be finished by a different administration, and it was the first return to the moon program ever in U.S. history to survive a transition to not just the next presidential administration, but one of the opposite party. And that says a lot about the consensus building that they did in that first term. This has to be part of this. So, wind change does come to NASA. If they want it to last, if they want it to succeed beyond four years, beyond the two-year congressional cycle, there has to be some consensus building.

And that'll be one of the key messages that we're going to bring, and that's the opposite of a divisive message. By definition, that is a unifying message. And then leaning into this idea of it's a public agency and it owes us accountability, and transparency, and openness. These are the types of things we're going to be there to talk about a lot this year, not just numbers and funding, these are broad philosophical opportunities we have to remind people that space does bring out the best in us and can bring out the best in us. And it's still a huge opportunity despite the trouble that NASA as an institution is going through now, that's what we're going to be focusing on.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks for trying to navigate these complex times and keep all of us, including me, updated on everything. And I really look forward to seeing you all in Washington, D.C., and thank you to everyone who's going to be joining us and adding their voices to try to support space exploration, because it really does bring us together and now is the time that we need all of our voices to help support all of these scientists and our wonderful programs.

Casey Dreier: Can I add one more thing, Sarah?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah.

Casey Dreier: Because anyone who listens to my show knows I get amped up about talking about space, so I'll go on. Two things I just want to mention, emphasize, if you're listening. The Space Advocate newsletter, it's coming back this February. We will have the link in the show notes, that's another way in which you can follow along what's going on. And then if you're not a member, become a member because on the community, on our online digital community, Jack and I are on that too, and we have a whole space policy section. So, we're trying to do a lot more communication there and engagement there, and you can ask us questions, and we have online briefings and other types of things as news is developing. So, we want to talk to you and we want to give you as many tools as you can. So, if you want newsletters or online communities or so forth, you have your options. And of course, this wonderful podcast, Sarah, that you host so well. Lots of ways to engage, and we hope you will engage with us.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks so much, and good luck with everything in the coming months. I know it's going to be a lot, but I don't trust any two people on Earth to do it better and more fair, and with as much kindness as you two do. So, thank you.

Casey Dreier: Thank you, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: The Planetary Society's space recommendations for the second Trump administration are available on our website if you'd like to learn more. And while I'm in Washington, D.C. for our Day of Action, I'm going to be hosting a Planetary Radio live show at the Library of Congress. If you're in the area, please consider joining us. Now it's time for What's Up with Dr. Bruce Betts, our chief scientist. I have more questions about hazardous asteroids, and he's exactly the person to ask. Hey, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hey, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So, earlier in this episode I got to talk to Kate about the new hot topic Asteroid 2024 YR4. Glad to hear that it's probably not going to hit us, but a 1%, 2% chance is pretty high.

Bruce Betts: We haven't had this much excitement since Apophis seemed like it might hit, and fortunately Apophis, which is even significantly bigger, is not hitting but doing a flyby in 2029. So this one, yeah, the odds are both now the percentage is low, but odds are the percentage of probability of hitting will drop to zero at some point, but you need to get more and more observations over time to figure out the orbit precisely enough to know that for sure.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: In the article you were quoted saying that the odds of impact could go up before they drop to zero. Why is that?

Bruce Betts: Yeah, it's very counterintuitive, but you want the baseball analogy or the asteroid discussion?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I just watched a sport ball yesterday, so let's go with sports.

Bruce Betts:

Okay, sports for 100. So, you got a pitcher and they're going to throw at the catcher, and the catcher's got the catcher's mitt right where they want it, and they're not going to move that catcher's mitt. That's Earth, pitcher's throwing an asteroid. What happens is as soon as it leaves his hand, you've got an uncertain region. Think of an area around the catcher's mitt where you don't know when it first comes off his fingers where it's going. And so, it's very uncertain. It's a very big could hit the batter, it could go over here, it could go over there. Then as you get more measurements of it moving towards the things, you start to reduce the uncertainty that area around the catcher's mitt, and does it move? When it shrinks, the probability of hitting the catcher's mitt, Earth, actually goes up first if the catcher's mitt stays in that uncertain area.

And then as it gets smaller and smaller, you'd hope that the uncertainty, if it's Earth, not a catcher's mitt, it goes off of the catcher's mitt or Earth, sorry for the possibly strained metaphor, and once the uncertain area goes off the catcher's mitt it drops to zero, but as long as the catcher's mitt stays in it, that keeps going up. So, your uncertain area of where the asteroid is going to fly through relative to Earth in 2032 is big enough to include Earth now, but it's starting to get smaller. And the first thing that happens, as long as Earth stays in the uncertain area, is it goes up, and then suddenly that uncertain area will drop suddenly, using the term loosely, will drop off the edge of the Earth, and you'll be like, "Yes, the worst we've got is a really close path."

And then it gets smaller and smaller, and it's farther away and you're good. But it causes a situation that leads to freaking out of like, "Oh my gosh, the percentage is going up," which makes you think we're in trouble. But I mean, we may be, we have a 2% chance of that, but we'll see as the uncertainty changes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And that's actually what happened over the weekend. I was hanging out, scrolling my phone when I saw an article come in through CNN. It's like, "The chance of this thing hitting us just went up to 2%." So, that makes a lot of sense and makes it hopefully less scary for people.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. No, it was good because even though everyone in the planetary defense field knows this, I looked really smart by having a quote saying, "Hey, it might go up first." Of course, I'll look bad if it ends up hitting, but I don't think anyone will remember by then.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's true. Kate said that the way that we classify these objects and their danger level is on something called the Torino impact hazard scale, and this one categorizes at a one. But can you describe what that scale is like? What range of numbers we're looking at?

Bruce Betts:

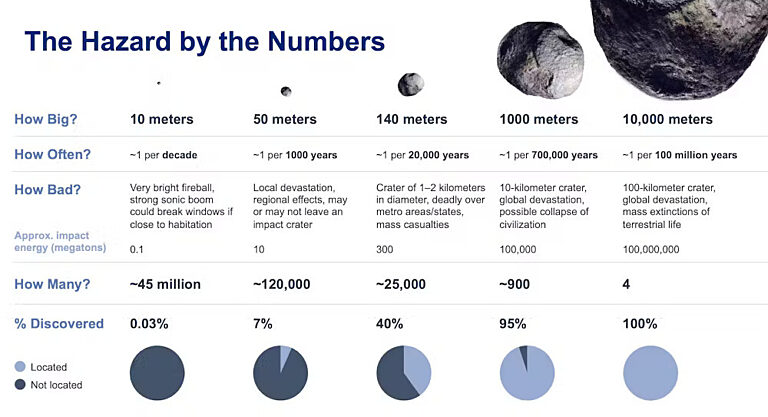

0 to 10, 10 is extremely bad, like dinosaur killer kind of thing that's going to hit, 0 is it's going to miss. And the lower numbers represent, it's a combination scale. It defines the probability of impact at that time, like measured today, and you would get the probability of impact and then the size of the object, which will determine as well as its velocity, how much damage it would do if it did hit. So, bigger numbers or higher probabilities and bigger objects. So this is a, to use the term used often in the community, a city killer. So, if it comes in over a city it destroys the city, but that's disturbingly on the small scale of things that could really cause damage. But on the really small scale, you've got a Chelyabinsk where you do an air burst and you do some damage, and then you've got something like this that's more like a Tunguska in 1908 that leveled 2,000 square kilometers of forest.

So, that's one and a half times the size of City of Los Angeles for reference, and we don't know the exact size, but basically what it's telling you is, "Hey, you've got a 1%, 2% somewhere, you've got a very few percent chance of hitting, and you've got an object that's in the 50 to 100 meter-ish type range." And so, we give it this such and such a number. If the probability goes up above a certain point, they'll increase that. The size shouldn't change, even though we're uncertain by a factor of two on the size, which is not at all uncommon because we basically just have a brightness and we don't know how bright or dark the object is. So, that's what right now the size is calculated from. So anyway, it was developed in what's sometimes called Turin in Italy at a conference, which is referred to as Torino. And so, it became the Torino Scale.

What it really is, is not for the scientists but more a threat level, combined threat level to communicate to the public. But depending on how much time you have to explain it, it may communicate it or it may just confuse it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Fair.

Bruce Betts: But we're in the low range, but no, Sarah, this is the highest anything's gotten since Apophis, which made it to a four. This can only make it to a three because it's not as big.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's remarkable that in all of the near-Earth objects we found, and it's like 37,000 at this point, that this one happens to have the highest rate, at least for now, of its chance to hit us. And even then it's still very low, so this makes me feel a lot safer and I'll feel even better when NEO Surveyor is up there checking everything out for us.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, I can make you feel less safe if you want, but ...

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Plenty of things.

Bruce Betts:

It's still a low probability of impact, and that's why we have trouble getting people to take it seriously. So that's why, in that respect, if it's not going to hit, we obviously don't want it to hit, but if it's not going to hit it's like Apophis, it's a good educational moment to say, "Hey, don't forget about these. This is a natural disaster that could be really huge, and it's different than a hurricane and Earthquake." We can actually prevent this with enough work over time, or at least seriously mitigate the amount of damage, and we're getting there. But we found 35,000-ish of the so-called near-Earth objects, which measures how close they come to Earth in their orbit. There are about a million that are capable of causing damage on the surface of the Earth.

So, we have a ways to go. Now, some of those are Chelyabinsk sized, which still injured over 1,000 people and broke glass, so not a fun toy, but on the smaller end you've got those. And the good news, besides the fact that these don't happen very often, is there's a lot more little stuff than big stuff, which is why we have 50, 100 tons of material hit the Earth every day. But it's lots of little tiny stuff that burns up, makes pretty little meteors, and it's only occasionally you get the kind of big stuff, and then it's really only occasionally you get the really, really big stuff.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Man, that's a lot of stuff falling to Earth every single day. I don't know if I've ever heard how much stuff in bulk actually hits us. That's cool.

Bruce Betts: Well, let's go ahead and make that the random space fact. No, I'll give you something else, but that's kind of wild.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That is wild. Well, all right, what is our actual random space fact?

Bruce Betts:

Random space fact. I'm getting a little crazy in my interpretations of random space fact, but this is something I think is neat. When you're looking at James Webb Space Telescope images, JWST, of the planets, you'll notice that the planets often, the ones they release, the planets often appear dark. So, like Saturn looks dark, the rings look bright, it gets even stranger when you look at Neptune where Neptune looks dark and little Triton, which is big for a moon but not the ... It looks super bright, and that's because they're showing you a methane band is dominating what they're doing. So, methane sits there in the atmosphere and makes it look blue, but it also loves to absorb near infrared light.

And so, when we're looking in the near infrared, there's not much coming back from the sunlight to see from those. Whereas Triton's covered with nitrogen ice and the like, and Saturn's rings are mostly water ice. And so, at these particular wavelengths, often the two micron land, they don't. So, it causes very different look than when we look normally, and can be rather surprising in the result. So, that's a little something if you look up your JWST planetary images of the giant planets.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: They're some of the most beautiful images. I mean, you can't really beat things like Voyager going right up to the planets and taking full color images that we can see in the visual spectrum. But you get to reveal some really cool details with these other band passes. And I love those images of Uranus and Neptune so much, because we haven't had an opportunity to see them in that level of detail in decades.

Bruce Betts: Yep. And for example, the rings. I mean, the rings of Neptune are very, very hard to see from Earth, and that shows them very clearly. And so, it's opening up a whole new world, even in our solar system. Not to mention the things they're doing in the distant universe. No, really, we're not going to mention the things they do in the distant universe.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh, really though, there's so much wacky science going on with JWST right now, but I love it. Every new discovery is mind-blowing and weird, and changing our paradigms, and it's so cool-

Bruce Betts: Yeah, it's wild. And it's such an engineering marvel, it's certainly one of the ones that I fortunately and correctly predicted. There's no way they can make that work, it's so complicated, but it's magnificent. They did it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: They absolutely did.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody go out there, look on the night sky. Think about lemons, and oranges, and other citrus. I don't know why. Thank you, and good night.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with Hayley Arceneaux, the first pediatric cancer survivor in space. She'll talk about her books, Wild Ride, and her new Kid's book, Astronaut Hayley's Brave Adventure. If you love the show, you can get Planetary Radio T-shirts at planetary.org/shop, along with lots of other cool spacey merchandise. Help others discover the passion, beauty and joy of space science and exploration by leaving your review and a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day, but helps other curious minds find their place in space through Planetary Radio.

You can also send us your space thoughts, questions, and poetry at our email at [email protected]. Or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the Planetary Radio space in our member community app. Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by our dedicated members from all around the world. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. And until next week, ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth