Planetary Radio • Jul 24, 2024

Victory for VERITAS

On This Episode

Darby Dyar

Professor of Astronomy at Mount Holyoke College, Deputy Principal Investigator for NASA’s VERITAS mission

Casey Dreier

Chief of Space Policy for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

Fans of Venus were saddened in late 2022 to learn that one of NASA's upcoming Venus missions, VERITAS, was defunded, but with the help of space advocates, the mission is now back on. Darby Dyar, the deputy principal investigator for VERITAS, returns triumphantly to Planetary Radio to share the story. We also take a look at the new U.S. House of Representatives budget request for NASA and how it will impact programs like Artemis and Mars Sample Return with Casey Dreier, our chief of space policy. We'll close out our show with Olympic cheer as Bruce Betts, our chief scientist, shares a new random space fact in What's Up.

Related Links

- The House's 2025 NASA Budget Creates Problems for Science, Artemis

- VERITAS, NASA's Venus mapper

- Why we need VERITAS

- The Planetary Society, American Geophysical Union, and Prominent Academic Institutions Call on Congress to Save VERITAS Mission to Venus

- Planetary Radio: The case for saving VERITAS

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed: VERITAS is back on, this week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our Solar System and beyond. Fans of the planet Venus were saddened in late 2022 to find out that one of NASA's upcoming Venus missions called VERITAS had been defunded. But what do we say when space missions we love get defunded? Not today. Darby Dyar, the deputy principal investigator for NASA's VERITAS mission, makes a triumphant return to Planetary Radio as we celebrate victory for VERITAS. But first, we'll take a look at the US House of Representatives' budget request for NASA and how it will impact programs like Artemis and Mars Sample Return with Casey Dreier, our chief of Space Policy here at The Planetary Society. We'll close out our show with a bit of Olympic cheer as Bruce Betts, our chief scientist, shares a new random space fact in What's Up? If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it. The US House of Representatives' Appropriations Committee has moved forward with a funding bill for NASA in the Fiscal Year 2025. That's one more step toward finalizing next year's budget for the agency. Of course, there's good and bad news to come out of it. This budget request departs from the US president's budget request in a few ways, prioritizing funding for some missions and programs over others. To get deeper into it, here's Casey Dreier, our chief of Space Policy, to explain. Hey, Casey.

Casey Dreier: Hey, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Your new article is all about the House's proposal for NASA's 2025 budget. Last week I was speaking with our director of Government Relations, Jack Kiraly, about the briefing that they had just had in Washington, DC. At that moment, it was actually just after the House Committee on Appropriations had taken the first step in their counterproposal to the president's budget request, which we might call PBR over the course of this conversation just to make it a little shorter. The president's budget request came out in March. Now we've got this new House proposal. I always want to take a hopeful tact with these subjects, but it looks like we might be facing some difficulties for both NASA's Science and Artemis programs. So starting right out the gate, what's going on with Artemis?

Casey Dreier: Well, this is all in the context of, as you said, the House budget, so one half of a conversation is what we're seeing. The House and the Senate both will release their own versions of NASA budget for next year. They will ultimately have to reconcile them, vote on the same budget, and then that's what moves forward. So this is the opening ante, in a sense, by the House of Representatives. What they do is they increase NASA's top line budget by about 1% from last year, which was expected. That's with these budget caps we have. But unlike what they have done with other times or past times where they've kind of applied those cuts evenly, we have seen them basically move a lot of money around within this small increase. In Artemis, the consequences of that are that, in this proposal, the House would restore about half a billion dollars of funding towards the SLS and Orion rocket and space capsule that is part of Artemis but is the big, kind of classic contractor projects, relatively expensive but very strong political support, and they don't add any extra money to put that money back into these programs. They don't say where to cut it. But if you look closely and do math, which is part of my job at The Planetary Society, you'll notice that the only place that it functionally could come out of is the Gateway Space Station that's going to the moon. Basically, they've created a half a billion dollar hole. There's only a handful of ways you can pay for that. If this passes, NASA would find itself in a relatively difficult position with that project.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How much funding would actually be pulled back from what we were expecting for the lunar Gateway?

Casey Dreier: Well, and this is the uncertainty part, right? So there's a couple of knobs NASA would have to turn in this situation, but the big picture is in this House budget, the Congress moves half a billion dollars into its preferred programs and does not backfill, so it just leaves this hole. So Gateway could either pay all of it, half a billion out of the Gateway program. There's a few other smaller technology development programs like Advanced Exploration Systems and some Mars planning projects within the same account that they could pull from, but it doesn't make up for that total amount. NASA can move money between accounts up to 10%, so a couple a hundred million maybe could be moved to backfill Gateway. But then the question becomes, where does that come from within NASA? It would have to come from something else. We haven't even talked about Science yet, but Science has it way worse than Exploration right now. So the question would be, where does this money come from? This is the situation we find ourselves in of what happens when you underfund our space program.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What would be the potential implications of a decision like that for the long-term viability of us progressing through our Artemis program because that could delay us quite a bit?

Casey Dreier: It could. Again, there's a lot going on with Artemis right now. Gateway is this lunar space station planned for, I forget, Artemis IV or V and the initial parts of it that then get built up by international partners. Of course, Artemis III already seems to be delayed with or without funding issues, but that's just the technology of landing on the moon again. Artemis II is becoming delayed as well as NASA tries to understand the heat shield problem with Orion. This would be one additional way that uncertainty and delay would be added to the project writ large, particularly again at the orbiting space station, which for all the ways that you can talk about that out there is the keystone of NASA's international partnerships with Artemis. Much easier to get to a space station on a frequent basis and much more straightforward than landing on the moon and safer. Gateway has significant contributions coming from the European Space Agency, from the Japanese, from United Arab Emirates. If that doesn't move forward, that has ripple effects through all of our international partnerships with a variety of other countries and organizations. So ideally, we don't want to see this happen.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Allocating that amount of money to the Human Landing System, I think, puts a lot of stress on the idea that we need SpaceX and potentially Blue Origin to really meet their milestones. That potentially means that we have this choke point going on if we're putting so much of it in this basket.

Casey Dreier: Well, yes, this opens up a whole critique of the Artemis structure, which has been put forward to varying degrees by observers, including Mike Griffin, who was on the Space Policy Edition a few months ago, but that's not what we talked with him about, former administrator of NASA. A lot of different components add up to Artemis. A lot of them are what's called critical path components, and any one of those go wrong, you don't land on the moon. You add into this the uncertainty, and I've said this a variety of times on Space Policy Edition and in other interviews, the commercial partnerships for lunar exploration, it's an experiment. We do not know how that's going to work out. We have one incredible example of SpaceX succeeding pretty much beyond anyone's wildest dreams in low Earth orbit with commercial crew and cargo, and then basically single-handedly creating this potential vast new market for private space exploration, or at least proving it out and inspiring a lot of other companies to join them. But we haven't seen any other companies like SpaceX in terms of the radical success that they've had. So if anyone can do it, SpaceX probably can, but there's still a chance that SpaceX might not be able to do it. Maybe Starship doesn't work. It's looking good. But this is the point. It's part of the critical path. If something like that gets delayed, the United States, NASA did not give Blue Origin, the other alternative for Human Landing System, funding until much later, so they're even further behind. So all of these things come together. Sarah, this is why no one's landed on the moon in half a century.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's complicated.

Casey Dreier: It turns out that it's really, really difficult. It's very complicated. It's very hard to do, and mixed into this is a lot of now budget uncertainty for various components, and of course, programmatic and technical uncertainty.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: As you said earlier, we've been talking about the Artemis program, but this House budget proposal impacts NASA's Science Mission Directorate much more heavily. Essentially what they're trying to do is meet the needs of the Mars Sample Return Mission, which is something that we've been advocating for for a long time. We want that mission to go forward. But in order to do that, they're going to have to pull that money from somewhere else. What specific programs might face setbacks or delays because they're reallocating this money?

Casey Dreier: Again, it's a very, as you said, similar problem with Artemis but worse because the House reduces funding for the Science Mission Directorate writ large relative to the president's request. It keeps it flat with last year, which last year was a half a billion dollar cut, almost all directed at Artemis. Since then, The Planetary Society and other groups, including the American Astronomical Society and the American Geophysical Union, we are pushing back and saying, "Look, we cannot do the slate of incredible science missions that NASA has been directed to do with these deficits in science funding." Because not just the cuts. It's inflation, of course, so a dollar from NASA buys less than it used to. We have to raise the ceiling in the Science Mission Directorate rather than shrink it. Obviously, that didn't happen this year because, again, we're still operating under these budget cuts or budget caps for the entire United States, and Artemis is clearly getting the political priority in a sense rather than science. This is not the first time and not the last time this is going to happen with big human space flight projects and science missions. But as a consequence, again, because Artemis grows and does better, something else has to pay for it. In this case, it was Science. Then within Science, you have a serious number of issues facing the project, including Mars Sample Return, which, as we saw, we've talked about, has lost hundreds of millions of dollars. That was all the cut last year. So the House wants to add back, and this is where MSR has its most political support is the House of Representatives. They added $650 million for MSR next year. NASA had requested 200. Now, look, $200 million is a bad number for Mars Sample Return. Even with this uncertainty around how we're going to move forward with it, with commercial partnerships or not, it's still going to be an expensive mission. It's still going to be billions of dollars. To ramp it down another a hundred million, that'd be another a hundred million cut from this year, you start losing a lot more workforce. We've seen layoffs at JPL and other places already as a consequence. So some money has to go back to MSR. 650 would be a great number. That allows the whole national apparatus of going to Mars to hit the ground running when NASA does choose a path forward. But because they didn't add any extra money, they took some from Earth Science and moved it to Planetary Science, $200 million out of a $450 million increase. That leaves a quarter billion-dollar hole in Planetary Science. That's a scary place right now because there is just no room in Planetary Science. Dragonfly was just confirmed to Titan. You do not want to cut funding to a confirmed mission because they've made the contracts, they've made the design, they have their launch plan, and that will cost everyone a lot more in the long term. Same with NEO Surveyor. That's a confirmed project. I worry for the future of our Venus missions that are both in formulation, easy to cut. But you cut something like both of them, $70 million, you're still not at a quarter billion, you're hacking at the bone here. You can go into fundamental research. You can go into fundamental technology around radioisotope powers, which enables us to access the Solar System and pays the Department of Energy to produce plutonium 238. I mean, you can, but you can't really do any of these. So it's a very, very tough position to be in. In a sense, this illustrates the exact reason why we need more funding for Science because you just literally cannot do the things that, again, NASA is being directed to do and in and of themselves are good things. But this is the imbalance, this is the political price that really is going to get more and more difficult unless this fundamental problem is addressed.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We're still waiting on the Senate to release their budget request. But it's also an election year, so there are some significant factors here that might make this a little less top of mind. What else is left that we can do to influence the final outcome of NASA's budget?

Casey Dreier: Yes, it's an election year. Look, most members of Congress know that they don't require the space vote to win their elections, unfortunately. But this is the thing, ongoing communication, what will happen is that... Our work at the Society hasn't stopped just because it's an election year. As you said, our colleague, Jack Kiraly, is out on DC almost every single day in person and then working and focusing on that strategy every other minute of his work life. We are working with our partners, we're talking about these issues, and we're talking about issues with people in Congress and their staff. So this is an ongoing issue that we're not going to let go. The Senate obviously is going to have their release. If it's anything like last year, the Senate will be much worse for... It's not going to be like a magic solution either. Neither the House nor the Senate has shown much interest in NASA Science, unfortunately. That's just the reality in the last couple years. It's not that everyone is against Science, obviously. It's just that it's a lower priority for them relative to these fundamental major political forces that NASA is awash in every year, and it's just particularly tough out there right now. So we will have more opportunities when we think the time is right for members to reach out to the members of Congress. For those who live in the United States, just keeping our program going and supporting us is an easy way and staying up to date and follow it with the Space Policy Edition on our website. We'll let you know when the time is right to act. You know what? If you are running into a member of Congress while they're running for reelection, and particularly if they're a member of Congress sitting on the Appropriations Committee, toss in a word about NASA Science. A lot of members do, but it's really people on the committee at this point that are the difficult hill to climb.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, it's not the happiest of updates, but thank you for sharing this with us. Honestly, it seems like a bummer, right? The United States and our space program is the largest one in the world, and so necessarily there are knock-on effects for space agencies all over our planet. But there are also many, many other space agencies that are trying to reach these goals as well. It heartens me to know that even if we might have to delay, say, our Venus mission, the European Space Agency has a Venus mission as well. This might create a space for other space agencies to try to excel and put that pressure on NASA funding in order to get what we all need to get to space and explore.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, that's certainly a great way to think about it, too. Let me, if you can't... Just give me another minute. There are good things about that. We talked about the bad things, and of course, that's our initial thing. This budget obviously could be a lot worse. There are some really nice bits and pieces, and that's the issue. There's a lot of good individual bits in this, and it's just how they add up or don't in this case is what causes the problem. But I just want to call out, there was support for NEO Surveyor, support for a range of funding for NEO Surveyor to keep that moving forward. They funded Dragonfly at the full request. They're funding a lot of other scientific needs. It's not specifically, I'd say, cutthroat going after some of these missions. It's just that here's the ones we care about and then we leave it up to NASA to figure out the mess for some of the budgeting. Another big picture thing, it still funds our... full funding for Human Landing System to land on the moon. When have we said this again recently in human history that Congress is fully funding a human landing system for the moon? That's a great thing to say, so let's not lose complete track of it. It's not the best budget. It has some serious problems, problems that I anticipate will probably be worked out with the Senate. Again, this is why I said at the beginning, this is one half of a conversation that we haven't heard the other bit yet, and they're setting up their positions. This is where they care about. You will see similar things from the Senate. We anticipate opportunities to resolve this going forward probably sometime after the election. So don't get too excited. We probably won't see a resolution to this until November or December

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Plus, hey, Mars Sample Return is something that I'm really looking forward to.

Casey Dreier: That's the thing. You look at the language, it says Mars Sample. We love Mars Sample Return. We saw a recent endorsement, alternate piece of legislation related to space called the NASA Authorization Bill that was just released by the House as well. So there's a lot of good things in there. We just got to make the numbers add up. By that, we need to make the numbers go up. That's my new slogan.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: At least we've got some numbers, and it's all just TBD at this point, so we're in a better place.

Casey Dreier: Yes. I can at least do math with the numbers we have.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks so much, Casey.

Casey Dreier: Anytime.

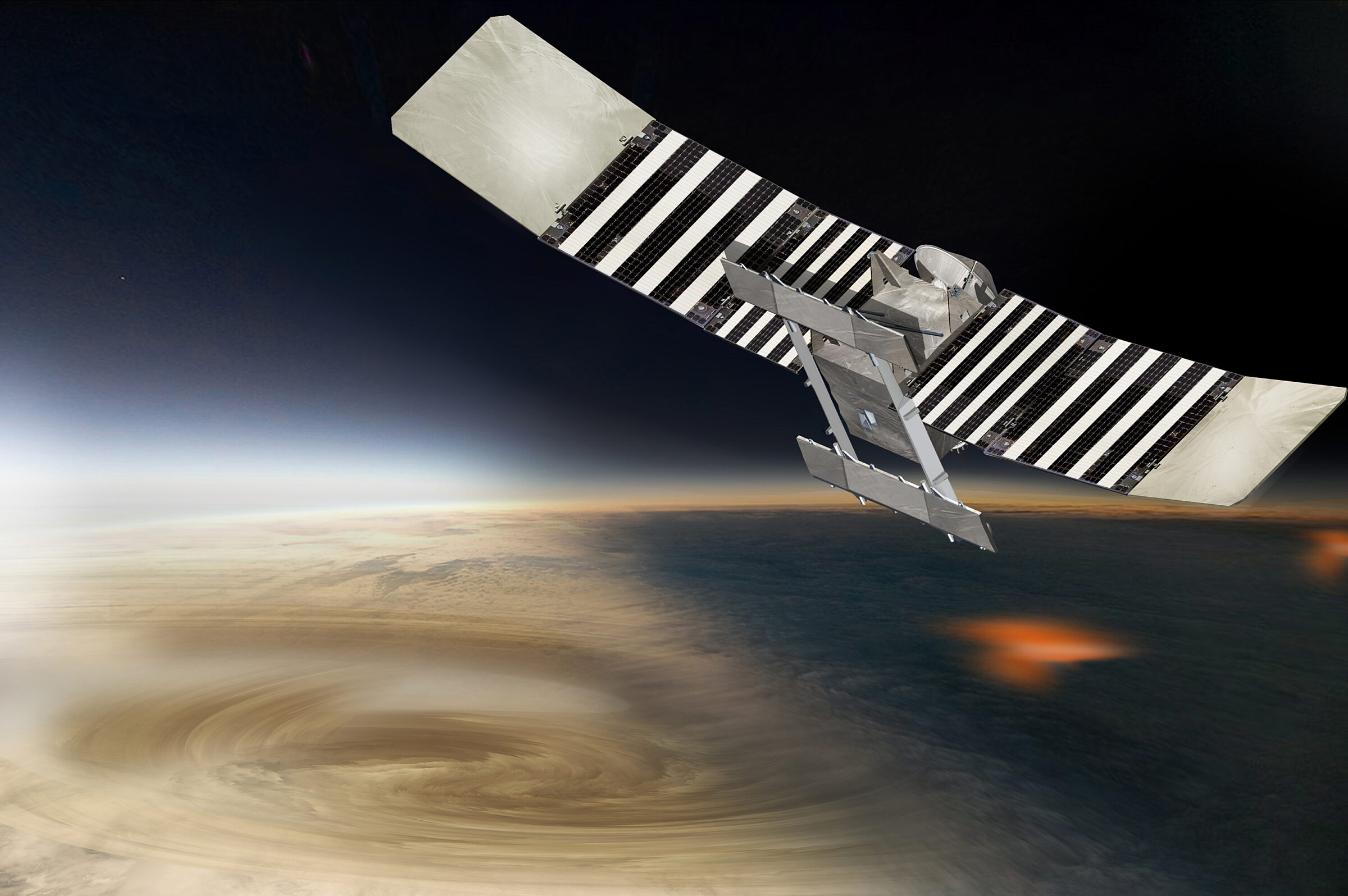

Sarah Al-Ahmed: There are so many complexities when it comes to funding space missions, and what's at stake is about more than just our ability to learn about the universe around us. Spacecraft are dreamed up, planned, and built by humans who have dedicated their careers to exploration and science. Each mission plays a crucial role in the broader plan, working in concert with missions and instruments from space agencies all around the world to achieve our scientific goals. Defunding missions and progress dramatically impacts the lives of scientists, engineers, and their friends and family. But it's important to remember that even in the face of adversity, when spacecrafts' futures seem uncertain, it's not necessarily the end of the road. Take VERITAS for example. Last year in May 2023, I invited Dr. Darby Dyar, the deputy principal investigator for NASA's VERITAS mission, onto Planetary Radio. The episode was called The Case for Saving VERITAS. At the time, things were not looking good for the mission. VERITAS, or the Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy mission, was designed to help us learn more about the geologic history of Venus. We want to understand why our sister planet evolved so differently from Earth. VERITAS would help us do that in a variety of ways. It would create a detailed map of the entire surface of Venus. It would also analyze the rock types and look for evidence of possible volcanic or even tectonic activity. It would also investigate the planet's gravitational field and analyze the atmosphere in a way that might help us clarify whether or not life could survive in the cloud tops. When the mission was defunded in October 2022, it was a huge blow to our aspirations to understand Venus. But happily, with the help of space fans and advocates, the mission is now back on. Today, we welcome Dr. Darby Dyar, the deputy principal investigator for the VERITAS mission to Venus, back onto the show. She's a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute and professor of astronomy at Mount Holyoke College. It's important to note that while Darby helps lead a NASA mission, she's not a NASA employee. People who work for NASA aren't allowed to go to Congress to advocate for space missions. It's a large part of why The Planetary Society's space advocacy matters. As an independent group with no financial stake in the selection or success of space missions, we can be the voice for space scientists and engineers who cannot advocate for themselves. With the full support of the institutions she works for, Darby Dyar did what a lot of her colleagues couldn't do and embarked on an adventure to the US Capitol to save VERITAS. Hi, Darby. Welcome back.

Darby Dyar: Oh, thank you for having me again. I'm so excited to be able to talk about our, what's the word, rebirth.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I mean, really though, VERITAS is back on. That's a huge thing. Congratulations.

Darby Dyar: Oh, it's amazing. A couple of weeks ago, we celebrated the three-year anniversary of being selected. Boy, we were just ruminating on the ups and downs we've already had in those three years. So hopefully, the future will be a little less dramatic.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Here's hoping. Because your mission in June 2022, just three years ago, got funded as part of NASA's Discovery Program, and then it was literally just a few months later in that October that cost overruns at NASA put the mission in this position of jeopardy. How did those budgetary constraints impact the VERITAS mission?

Darby Dyar: Oh, we were stood down. We were all but canceled. All of the engineering team was stood down. They gave us shoestring funding, $1.5 million to support the US scientists on the team. But $1.5 million in this day and age, literally people had a couple hours a week to work on the mission. It was enough to support a field campaign in Iceland, which turned out to be a really nice, unifying thing for the team members that were able to go, but didn't really make much forward progress on the mission. It was just basically trying to keep us alive.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How did it impact your international partners?

Darby Dyar: That was very bad. Because the international partners are all committed to and involved with the EnVision mission, they are on a very tight schedule. So they needed to get the things that they were going to do for VERITAS done tout suite because they then need to shift gears and move over to EnVision. So one of the things that we were able to do with the shoestring funding, and we hadn't quite spent all of our money from the first year when we got full funding, was we were able to continue to support the foreign partners to the best of our ability, which was awesome. They were all really good sports and acted in good faith. To their credit, NASA headquarters was very hopeful in continuing to assure the foreign partners that VERITAS was going to come back and that these investments that the foreign partners were making were not going to be in vain. So it was kind of a team effort, and it worked out pretty well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: This was a really hard thing for you and everyone involved with the mission. The buildup to it, any mission takes decades and decades of dedicated scientists. But how did the broader science and space community react to the defunding of VERITAS?

Darby Dyar: That was also really reassuring. One of the things that I still can't believe happened was that all of the analysis groups... As you probably know, in Planetary Science, we have these analysis groups. I think there are eight of them. There's a Venus Advisory Group, there's a Mars one, there's an Outer Planets one, there's a Mercury one, etc., etc. Those groups report on a biannual basis to the Planetary Advisory Committee, which then reports to NASA headquarters. Heartwarmingly, every single one of the AGs backed VERITAS, and all of the AGs wrote a cross-AG finding which said that NASA should fund and fly VERITAS before they even consider having another AO for new missions. That was an amazingly selfless act and kind of renews your faith in human nature and in the planetary science community. It was a really rare moment of everyone coming together and supporting us. That meant a lot in the dark days of working without funding. So it was amazing. Then I will also say that we all got support from certainly friends and family and colleagues outside of Planetary Science as well. So a lot of people are aware of what happens when a mission gets canceled, and it was heartwarming support we got.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'm one of the people that has been at The Planetary Society for a shorter amount of time compared to the rest of the people on our crew. So for me, this was like the first mission where I saw everything kick into gear, all the space advocates trying to come together, and that the massive campaigns we were trying to do together to help save this mission and watching it all come together and actually work was a huge thing for me. I know we have a long history of this, but it really did feel like mobilizing all these people together made a huge difference for this mission.

Darby Dyar: It really did. I can't express well enough how grateful the mission is to The Planetary Society. I'm not saying this because of this venue, but because you have to realize that a large percentage of planetary scientists now work for the government. They work for institutions like APL and JPL. Therefore, they are not allowed to lobby in any way for the mission with the government. So that leaves people feeling very helpless. So we were fortunate that I was not at a government institution and I was able to lobby on our behalf. But if The Planetary Society hadn't come to our aid, I have a feeling that we wouldn't be in the place we are right now. So we are eternally grateful to The Planetary Society just as having a voice for us when we couldn't have our own voice.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's so heartwarming to hear. I know that we can't take credit alone. It takes all of the advocates and people like you that work on the mission and the legislators and their staffers and all of the other institutions that came together. We can't take full credit for this just on our own. But being able to help and play a part in this is just so invigorating. It's part of why I decided this year to go to our Day of Action in Washington, DC, for the first time, and it was my first time going to Capitol Hill. That was in April. Going there and actually advocating in person was such a journey for me. Then I found out that it was literally just a month before in March you got to take your first journey to Capitol Hill with our director of government relations, Jack Kiraly. How was that, and how did that whole thing happen?

Darby Dyar: Well, let's see. When we first got asked to stand down, Sue Smrekar, who's the PI of VERITAS, put us in touch with The Planetary Society, and there were a lot of teleconferences. It was decided that a couple of things should happen. So The Planetary Society launched a petition, and we got some high-powered people to sign onto it, including presidents of universities. So that was one amazing thing that The Planetary Society did. But it was then concluded that we needed to have a policy statement about this and that I should go to DC accompanied by Jack Kiraly and go visit people that were on the Appropriations Committees to try to lobby for VERITAS. So off I went, Darby goes to Washington, and it was quite an experience.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How many offices did you end up going to? Because I think during the Day of Action we hit... I don't even know how many tens of different offices we went to. It was a lot.

Darby Dyar: Well, first of all, I actually did this twice in two different trips. The first trip was more of a targeted thing because I visited the representatives of the states in which I reside, so Massachusetts and Maine. Then later I went back and, with Jack, just did a quick canvas of as many offices as we could hit in two days. When I got to see Jack on the morning of the first day, he's like, "Are you ready?" I said, "Okay." He pulls out this long list, and it's 105 representatives that we're supposed to go to. I'm like, "Okay, Jack!" I came armed with... Let's see. I had a bunch of VERITAS swag on me. I think I had stickers and magnets with me. I also had my secret weapon. In one of my pockets, I had a Mars meteorite, which no one can resist holding a piece of Mars. Even though it has nothing to do with Venus, I thought it would get people out of their offices, out of their desks, and out talking about the space program. And it succeeded really well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Anytime you could put a meteorite in someone's hand is something else, but a Martian meteorite? It was just a few months ago, I came here to work, and I caught Bill Nye screwing a display of a Martian meteorite into the wall because he wanted people to be able to have that interaction with a meteorite if they came to our office. It was great.

Darby Dyar: Yeah. It's only better if you can give somebody a Martian meteorite and a lunar sample at the same time, or even better, Mars meteorite, lunar sample, and Earth sample. That's the most powerful feeling in the whole world, and probably not very many people have had a chance to do that. But because I work on all those kinds of things in my lab, I can do that with visitors very often, and it never ceases to give me a thrill, too. Planetary science is pretty cool.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How do the people in the offices that you met react to you being there?

Darby Dyar: Well, let's begin by saying that, although Jack is used to Capitol Hill, I, of course being a mere university scientist, am not. Let me set the stage. I'm dressed in uncomfortable clothing. My daughter used to work on the Hill, so she had to pre-advise me on what people wore on the Hill. This included what I would consider to be uncomfortable shoes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: My feet hurt so badly after my first day in Congress.

Darby Dyar: Oh, yeah!

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I was like, "Why do I choose heels?"

Darby Dyar: Jack says I need to just go in these offices and introduce myself, which is, again, something that professors are not very good at. Jack was smooth as silk when doing this. So we started out with a few offices together, and then we split up to divide and conquer. Even though I was extremely uncomfortable doing this, especially repeatedly, people seemed to show interest. And as we know, it did pay off in the end.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, it is a little nerve-racking being there. Trying to dress the part and talk to that many people, it's a whole thing. But by the end of the first day of me doing it, I felt a little more comfortable, and by the end of day two, I was ready to go at it again. Here's hoping we don't have to go back to advocate for this one again. We got the funding so [inaudible 00:30:36].

Darby Dyar: Yeah, exactly. On the other hand, you're right, it wasn't that horrible. I got used to it. I've never been on Capitol Hill, so there was a cool factor of, "This is the office that I've seen on TV, and this is where they do the interviews, and this is the cafeteria where they eat their sushi on Fridays." So that was actually pretty impressive to me.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll be right back after this short break.

Bruce Betts: The Planetary Society is strongly committed to defending our planet from an asteroid or comet impact. Thanks to the support from our members, we've become a respected, independent expert on the asteroid threat. So when you support us, you support planetary defense. We help observers find, track, and characterize near-Earth asteroids. We support the development of asteroid mitigation technology. And we collaborate with the space community and decision makers to develop international response strategies. It's a lot to do, and your support is critical to power all this work. That's why we're asking for your help as a planetary defender. When you make a gift today, your contribution will be matched up to $25,000 thanks to a generous member who also cares about protecting our planet. Together, we're advancing the global endeavor to protect the Earth from asteroid impact. Imagine the ability to prevent a large scale natural disaster. We can if we try. Visit planetary.org/defendearth to make your gift today. Thank you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What were some of the key messages that you were trying to get across to them so they'd support this mission?

Darby Dyar: Of course, the biggest message that I try to share with people is that the space program is not just about science. It's about aspiration. When we study space, we give people with imagination, and particularly little kids like K-6 kids, something to aim for because I feel like space never fails to capture the imagination of people, but especially little kids who have learned not to be jaundiced about things. So that was part of my message, that we go to space not just to get science, but also to inspire people to become scientists, which is a message that I think resonates across party lines in Washington. There's also with Venus the line that I feel like one of the most important questions of humankind is whether or not we are alone. Venus, at the present time, given what we now know, is probably the most likely place in our Solar System to find evidence for prior life. When you start talking about that, people get really interested because we've been talking with the Mars program for many years about following the water and hoping that water would lead us to the discovery of life on Mars. But in the process of the long march that we've had on Mars and the incredible amount of equipment that we've had in use there, we found out that Mars probably only had water for about 300 million years, which is a very, very short period of time for life to evolve. Meanwhile, research on Venus has shown that the planet probably had liquid water on it for about three billion years, so significantly longer than on Mars and much more parallel to what happened on Earth. Therefore, if we want to find an answer to that age-old question of "Are we alone?" the best way to look for that is to look in another place in our Solar System that had water and conditions that are Earth-like for a long duration of time. So when you start talking about that, people get really interested. It's an easy sell.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, and that's a good way to come at it. Because whenever I'm talking about space missions, it's always about gauging your audience, and when you're going to Congress, you never know what their level of understanding is. Some of these people in the offices are so into it that they know every single thing about every space mission. Then there were some who didn't know a whole lot but just the message of hope and exploration was enough to really capture them. So that's a smart way of going about it, I think.

Darby Dyar: Well, thank you. Well, I always remember, I was on the Curiosity Rover mission. When we were all together right before the launch, the teams were all doing social events. At one point the ChemCam team went to... I think it was the Hollywood Bowl for a concert, and we all rode on a bus to get to the venue. We were all wearing our team shirts, and we all sat together at the back of the bus. I was sitting sort of at the edge of our group. A family gets on, and it's got a little boy who's probably, I don't know, five or six. He looks at us and he sees the Curiosity Rovers on our T-shirts. He just breaks out in this big smile, and he says, "Wow, are you guys working on Mars?" He came over and he wanted to talk to us, and he asked for autographs. I just thought it was the greatest thing. But it reminded me that what we're doing is not just about a topographic map or a geologic map or understanding the size of the core on Venus. It's also, as I said, about inspiring the next generation to be scientists. As an educator, that's something that I care deeply about, as deeply as I feel about the need to advance the science.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know it would've worked on me as a kid. Back when I got into it, it was literally just the fact that we knew exoplanets existed that got me into it. I can't even imagine how it would've changed me as a kid knowing how many missions are going on right now and what potential there is for the future. There's so many opportunities for these young people to get into science and for people who are now currently getting their degrees to go into science. I'm so happy that we have so many of these positions out there. It makes me really hopeful for the future.

Darby Dyar: Me too. It's really heartwarming to look around at the VEXAG meeting and see undergraduates and first-year graduate students just sitting there open-jawed listening to all this information about Venus. I know what they're thinking in the back of their mind is, "All these old people are going to be gone, and this is going to be my planet. These people are going to provide me with the fundamental data I need so that I can go on and do amazing things on Venus."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It reminds me of that classic Isaac Newton quote, "If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants." That's just the legacy of all this space exploration. Right now, there's this next generation waiting to move on to the missions that you and your colleagues have built, which is why I'm so pleased not just for them, but for you that this mission is actually getting the funding that it needs. Because when last we spoke about it, you were so dejected about it, the Psyche Mission team felt horrible about the fact that it felt almost like their mission was preferentially being given money that then was taken from VERITAS. It's a very interwoven situation. I'm glad that we're in a much happier place now because that was tense.

Darby Dyar: Oh, yeah. Well, and in some ways the drama isn't over yet, right? Because, again, to their immense credit, headquarters is now saying that they will not fly another mission until they get VERITAS fully up and running, nor will they even have another AO, announcement of opportunity, for another call until at least 2026. So I'm enormously impressed with how careful and methodical NASA headquarters is being. This is sort of since the arrival of Lori Glaze, and now Nicky Fox is doing an amazing job. Both of them are an incredible team, and I quite respect the way... They'll tell us when we're going to know something, and then they stick to that. They don't break their silence, they don't yield to pressure, they stick to their schedule, and they deliver on the day they intended to deliver. I've been enormously impressed by that even though it's incredibly frustrating to be told, "Well, you have to wait six months, and then we'll have an answer for you."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: When did you actually find that the mission was going to get the funding that it needed?

Darby Dyar: They called us in the morning. Then Sue immediately called me. We waited about three hours, and then they announced it. We were actually all at the LPSC meeting in Houston last March when we found out about this. So it was pretty fun. We got to go out afterwards and celebrate.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: There's nothing better than getting good news like that when everyone's together, right?

Darby Dyar: Yes, exactly. I'm just beaming as I talk about this. It was an amazing thing. But also, once you've had the rug pulled out from under you, you never forget that. So I'm the one that will be measured in my enthusiasm until we get to Venus and start getting data back. Politically, who knows what will happen. So I'm still going to be holding part of my breath until we get this thing off the launch pad and safely on its way to Venus.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: As we speak about earlier in the show, we only just got the congressional budget request for NASA. It's looking like we're going to have to make some tough decisions about how we fund things. There are so many missions that need the funding and so much important work that's happening for both the Artemis program and Mars Sample Return. So I think it's good to be measured about it. But for just one hot second, man, to just be excited about it, look at what you and everybody else accomplished together. You saved the mission.

Darby Dyar: Well, I have to say that when the Appropriations Bill came out and it was the exact language that Jack and I had pitched going around to these 105 congressional offices, I had this moment of, "Oh, wow, a single person can actually make a difference." As a scientist, I prefer to be deep in the laboratory with my rocks and my equipment and making measurements and thinking about conclusions. I work really hard to write good proposals, and I get funded and I deliver really good science. But I've never taken the additional step of trying to go beyond the funding agencies that fund me into the bigger picture of Congress where the money ultimately comes from. It was an eye-opener for me. I really had to eat my words about whether or not this would make a difference because I think it really did.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: You've been so dedicated to this mission for quite a long time, and going forward, I'm sure this experience will change the way that you approach your work. What message would you give to aspiring scientists that want to become a part of these missions and are probably going to have to grapple with these funding issues in the future?

Darby Dyar: Here's my advice. If you don't have an outstanding mission to pitch in the first place, don't bother. So make sure that your mission is absolutely perfect, that you have left no road untraveled and no questions should remain. It's very important that the science always be of the absolute highest quality. Then you have to believe in your mission, and you have to believe in working on a team. That's not trivial for some scientists, but it's really important for everyone to pull in harness because that's another key to mission success, I think. Everyone bolsters everyone up. Many of the people on the team couldn't go to Washington to lobby, so I had to step up. There are other times when I haven't been able to go because I had to teach, and so they were able to do things at JPL that I wasn't able to do. So you really have to have the attitude of being a team player to get things going. Then, oh boy, passion and enthusiasm. I have elevator speeches for Venus that I've honed over the last 15 years. It's not hard because I'm so excited about what we can do at Venus. That's an easy thing to be enthusiastic about, but you have to be very measured and controlled in exactly how you express it. Other advice would be don't put other missions down to make your mission look good. Recognize that all science in our Solar System is interesting, that everyone believes in their project, everyone believes in their mission. You have to trust in the process that good missions will get selected, and you can do that without bashing other missions, which there's sometimes a temptation to do. Then finally for me, it is about considering the implications of this beyond just the data that you're going to get from this mission. It goes back to this question of, is this an aspirational mission? Is this going to inspire humans to think of something other than themselves? Is it going to allow them to put their lives in perspective? When I teach about planetary science, that's one of the things that's probably the most important outcome of my class is that the students walk out the class saying, "Gosh, I didn't think about my econ exam for 40 minutes because this lecture was so fascinating." On a larger scale, that's what planetary exploration does for us is it allows us to put aside our earthly cares and think about something bigger than we are in the sense of something really bigger than we are. I guess all of those things are my advice. Then, of course, the final one is persistence and resilience, so persistence in continuing to do something and propose a mission that you have the passion for, flexibility in changing the mission in response to feedback that you get, and then resilience when you get viciously knocked down to have the ability to just stand right back up again. The second time we proposed the VERITAS mission, we got declined. Four months later there was a New Frontiers called to, and a small core group of us pulled our bootstraps on and managed to revise the entire proposal in record time of four months. It was an amazing effort. But sometimes the circumstances just demand that. Of course, that experience and the closeness of that team, I think, are probably one of the big factors that allowed us the next time there was a Discovery call to propose a proposal that was going to get selected. So a whole range of things that you need to do, but it starts with fundamental science and ends with persistence.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Science takes a whole lot of persistence. Whether it's trying to get through the hard problem set when you're in school or trying to work out all the bugs in a mission, there's so much to it. But persistence through the trials of having your mission defunded is a whole extra level, and I have so much respect for you and everybody else who took that and didn't just think, "Well, I guess we're going to have to throw in the towel." Instead, you were like, "Well, I guess we're going to Washington."

Darby Dyar: Yes, exactly. I guess I have to do this. But once you make a commitment to something, at least in my book, you want to follow it through. And this is such a good mission. VERITAS had to get flown soon because VERITAS is all of the foundational data on which the subsequent Venus exploration, including DAVINCI, including EnVision, including the future landers on Venus depends. We need a good, decent topographic map. We need to know the distribution of rock types on the surface. So those two things are so fundamental that it had to get selected sooner or later. But why we had to wait 30 and it will end up being almost 40 years for this, I don't understand. But I didn't study politics in school. I studied geology. Sometimes I think I could have benefited from a few politics classes to help understand the process better, but I've had a learn-on-your-feet kind of experience.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Both of them are almost equally complex. Well, now that we have the funding given to this project, when do we actually think it's going to launch? You alluded to it a little bit earlier.

Darby Dyar: I wish I could tell you a launch date. Headquarters has not yet given us a launch date. All we know is this. In the period leading up to them making the decision, they asked us to give them what are called funding profiles, which are, how many dollars per year do you need to reach launch on various different launch dates? So we gave them several different funding profiles that would ultimately culminate in launching on specific dates. When they approved our funding, they gave us the funding profile, but they didn't specify the end date. However, it's not rocket science to match up the funding profile that we got with a launch date. So we are hopeful that we will launch in 2031.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That doesn't seem that far off anymore. That's right around the bend.

Darby Dyar: Well, that's easy for you to say.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know. What are the next steps for the mission and the lead up to that?

Darby Dyar: Right now, there's a lot of buying equipment. I did not understand until I got so deeply involved in the leadership of this mission how complicated it is to assemble pieces of the mission, all the parts of the spaceship. Some of them are really unique. They only make a certain number. So there was a lot of wheeling and dealing when we first got selected to make sure that we got certain items that we needed to get, and some of those contracts had to get put on hold. So the first thing that will happen when we get spun back up is we will be able to get the contracts for the equipment that we need in place as quickly as possible. That's absolutely important. Then after that, we can start to spin up the science team. We can eventually solicit for participating scientists. We're hoping to have another field campaign so that we can look at Venus analog rocks hopefully in California or maybe back in Iceland. So there's science that needs to be done, but mostly the early funding is to buy stuff and pay for engineers. Then as the money ramps up, the engineering team will expand as we go to actually assembling all the pieces and integrating the spacecraft. Eventually, of course, the science team will get spun up, and we'll be doing supporting research and writing the software. There's a lot of things you don't think about. For example, and I was surprised when I was involved with the Curiosity mission, too, I remember sitting through meetings where we argued over what the name of the line command was going to be for "Turn laser on." So there's a lot of things like that that are done amazingly by consensus in Planetary or in this business that people don't think about that. But just building the software and integrating everything is a very complicated process. So that's a software example of the larger picture, which is all of the engineering.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, now it's the fun but also complex part in the lead up. I've spoken with a lot of people on the show who've made second appearances during my time, but I was so excited to have you back on. Because I think of all the people I've spoken to-

Darby Dyar: Ah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... this arc is just such a heartwarming one. I'm so happy for you and everyone on the mission team and happy for everyone in the broader science community because we need this mission. This is going to be so cool.

Darby Dyar: Ah, well, I wish you could see me. I'm grinning from ear to ear. It's a pleasure that we got snatched from the jaws of defeat and are now effectively on our way to Venus. I still kind of think I have to pinch myself sometimes that we're actually going.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: As many times as it takes.

Darby Dyar: Yes, exactly. So I'll be happy to come back as many times as you want and talk enthusiastically about what we're going to do on Venus because it's just going to get better.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks so much for joining me, Darby, and good luck in the future months.

Darby Dyar: Oh, thank you so much, and thanks so much for having me.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Now let's check in with Dr. Bruce Betts, our chief scientist for What's Up? Hey, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hey, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I just spoke with Darby Dyar about the VERITAS mission, which thankfully is now hopefully going to get fully funded and end up at Venus. I wanted to ask, what are some of the biggest mysteries that we don't know the answers to yet on Venus, and how can VERITAS help us solve those mysteries?

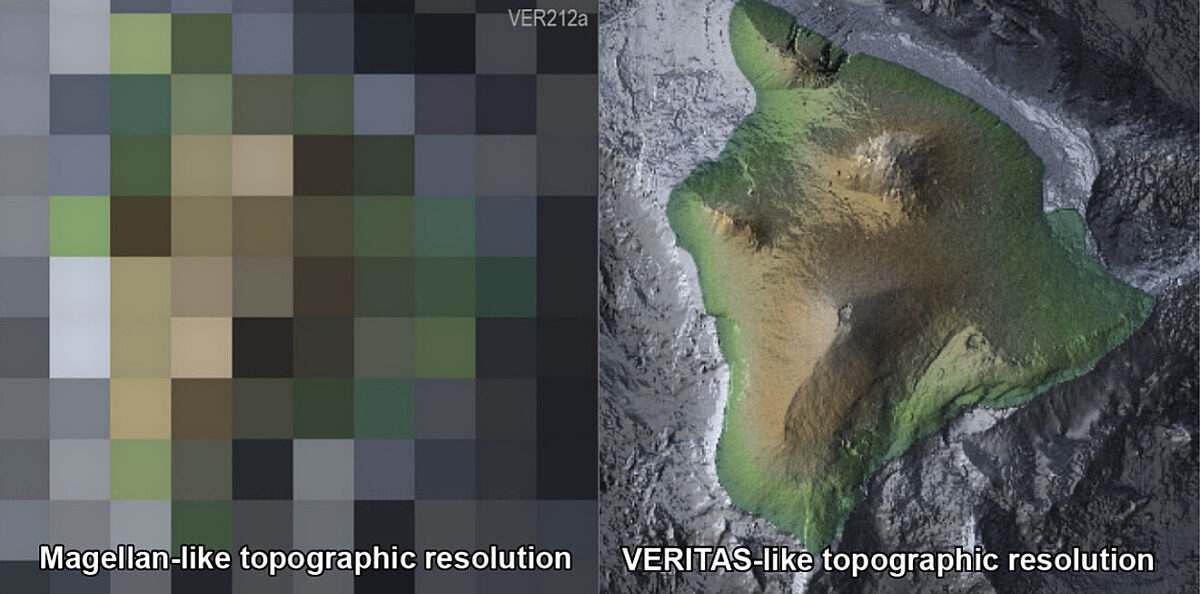

Bruce Betts: Nice, small question. The whole geologic history of Venus is intriguing and weird. Earth's got a variety of ages and continents and oceans and plate tectonics. Venus seems like everything kind of cut off most places a half billion years ago, which sounds like a long time, but compared to a four and a half billion-year-old place. So there was some giant overturn but then also subsequent geology. Then it seemed like the place was volcanically dead. But now it seems that there is some volcanism in some places. So personally, I think that's one of the most interesting things VERITAS will get us. Magellan radar mapping radically altered our understanding of Venus, and so getting higher resolution is going to take us much further. They've also got an infrared instrument that's designed to look through most of the clouds as much as they can and get a little information that way, spectral information. So learning what things are made of, what the volcanic history is, what the deal was with this, that basically you don't see a crater count that would indicate an older surface than half a billion-ish. So what's up with that? I know they're looking to figure out why it's such a hellhole. I think it's just in a bad neighborhood, but I don't know.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And hard to know what's lying underneath all of that atmosphere. I'm particularly curious about the history of habitability on that world. Did it actually have oceans? If it did, where did they go? There's so much there.

Bruce Betts: I do want to give cred to the missions that have been there in recent years, Akatsuki from the Japanese, and Venus Express from the European Space Agency, along with collaborations, both of them with other countries. But they were doing atmospheric stuff, by and large. So here we'll get a leap forward in radar looking at the surface and some ideas with instruments we haven't had before. Then DAVINCI's going, and we'll drop a probe, and the Europeans are playing. So Venus is going to be hot, hot, hot.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Plus, a couple of weeks ago you were telling me that there's actually a crater on Venus named Sarah. While I can find that in the Magellan data, now I can find it in high resolution once VERITAS gets there.

Bruce Betts: I should have said... I'm sorry, I meant to lead with that. The most important thing to study is Sarah Crater. Maybe we can send you there.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: If you could find some way for me to survive the acid rain on the way down and the crushing pressure and the melting of the face.

Bruce Betts: Ah, fine, fine, fine, whatever.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Whatever. I also wanted to share something that came into our comments recently, because a few weeks ago we had Newton Campbell, who's our new board member, on the show to talk about his career and all of that, but also about Australia's upcoming lunar rover called the Roo-ver. So many people in our comments wrote back that they need to create a smaller rover that goes with the Roo-ver to the moon and call it Joey.

Bruce Betts: Joey.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Anyway, yeah, I do like to bring up that we have that new lunar rover coming up because we did find out this last week that NASA's VIPER rover to the moon has been canceled. So there's a lot going on in the mix with the moon right now. Plans changing with the cost of Artemis and lunar Gateway, all of these things, but still some really cool things coming down the pipeline.

Bruce Betts: To look at things seriously, the Australians could really compete with the whole snake theme. I mean, my gosh, VIPER, they could go crazy with... Basically Australian animal-based rovers would be capable of killing all the other things on the moon.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And being adorable while they do it. I mean, platypi, those things are terrifying.

Bruce Betts: Something got scrambled when they got created.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Echidnas?

Bruce Betts: All right, now I'm going to think about the platypi.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Cassowaries-

Bruce Betts: Oh, and I don't-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... before we get any more random.

Bruce Betts: ... know why we're talking about that. No, we're supposed to be talking about the Olympics, right?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Wait, why? What's happening?

Bruce Betts: Random space fact, random space fact, rand, random fact, random space fact, random space fact. Well, the Summer Olympics are in Paris in-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know.

Bruce Betts: ... the next couple of weeks. Oh, but it also means that the random space facts will not be so random because I'm a huge Olympics fan, so we're going to tie things to the Olympics for the next little while. We're going to start with the highly insightful thing of everyone out there who's a Greco-Roman wrestling fan, which is most of you, I know. Imagine that the Earth was in the heavyweight category of Greco-Roman wrestling and you wanted to see where Venus would fit. If the Earth is a heavyweight, is Venus a middleweight which is the next one down? No, no, no. Venus would be two weight classes down, a low end of the welterweight scale because Venus, its mass is only about 81.5% of Earth's mass. So even though we could talk about it being a twin planet, when you start doing things like calculating volumes that work with mass and you're raising things to the third power, things get smaller. But more importantly, I think everyone probably on this listening can visualize the difference between a heavyweight Greco-Roman wrestler and a welterweight. So that's Earth relative to Venus. There you go. It's going to be good. Enjoy, enjoy being an Olympics fan there, Sarah? That's what people want to hear about, I know.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Funnily enough, my first tiny gig hosting anything ever was when I was in, what was it, in 10th grade, I hosted our class Olympics show, the little broadcast that you put out to your whole school.

Bruce Betts: Wow, Sarah trivia.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Sarah trivia. That was a lot of fun. Yeah, no, it's always really fun to watch all the nations of Earth come together and compete. It always makes me feel just, I don't know, strangely emotional every time it happens. But that's me.

Bruce Betts: I like watching weird sports every four years.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What's your favorite one?

Bruce Betts: Oh, I just enjoy anything that's weird. All right, everybody, go out there, look on the night sky and think about a platypus Greco-Roman wrestling with an echidna. Thank you and good night.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with even more space science and exploration. If you love the show, you can get Planetary Radio T-shirts, along with all kinds of other cool spacey merchandise at planetary.org/shop. Help others discover the passion, beauty, and joy of space science and exploration by leaving a review and a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day, but helps other curious minds find their place in space through Planetary Radio. You can also send us your space thoughts, questions, and poetry at our email, at [email protected]. Or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the Planetary Radio space in our member community app. Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by our dedicated members and space advocates. You can join us as we work together to support the missions that matter at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. And until next week, ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth