Planetary Radio • Nov 27, 2024

Seven worlds, one mission: The United Arab Emirates aims for the asteroid belt

On This Episode

Mohsen Al Awadhi

Director of the Space Missions Department at the United Arab Emirates Space Agency

Hoor Al Hazmi

Senior Space Science Researcher at the UAE Space Agency and Science Team Lead for the Emirates mission to the Asteroid Belt

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

The United Arab Emirates Space Agency is working on its next ambitious spacecraft, the Emirates Mission to the Asteroid Belt. It will visit seven asteroids, ultimately rendezvousing with Justitia, the reddest object in the main asteroid belt. We'll get an update on their team's progress from Mohsen Al Awadhi and Hoor Al Hazmi, the director and science team lead for the Emirates Mission to the Asteroid Belt. Then, our chief scientist at The Planetary Society, Bruce Betts, joins host Sarah Al-Ahmed for What's Up and a new random space fact.

Related Links

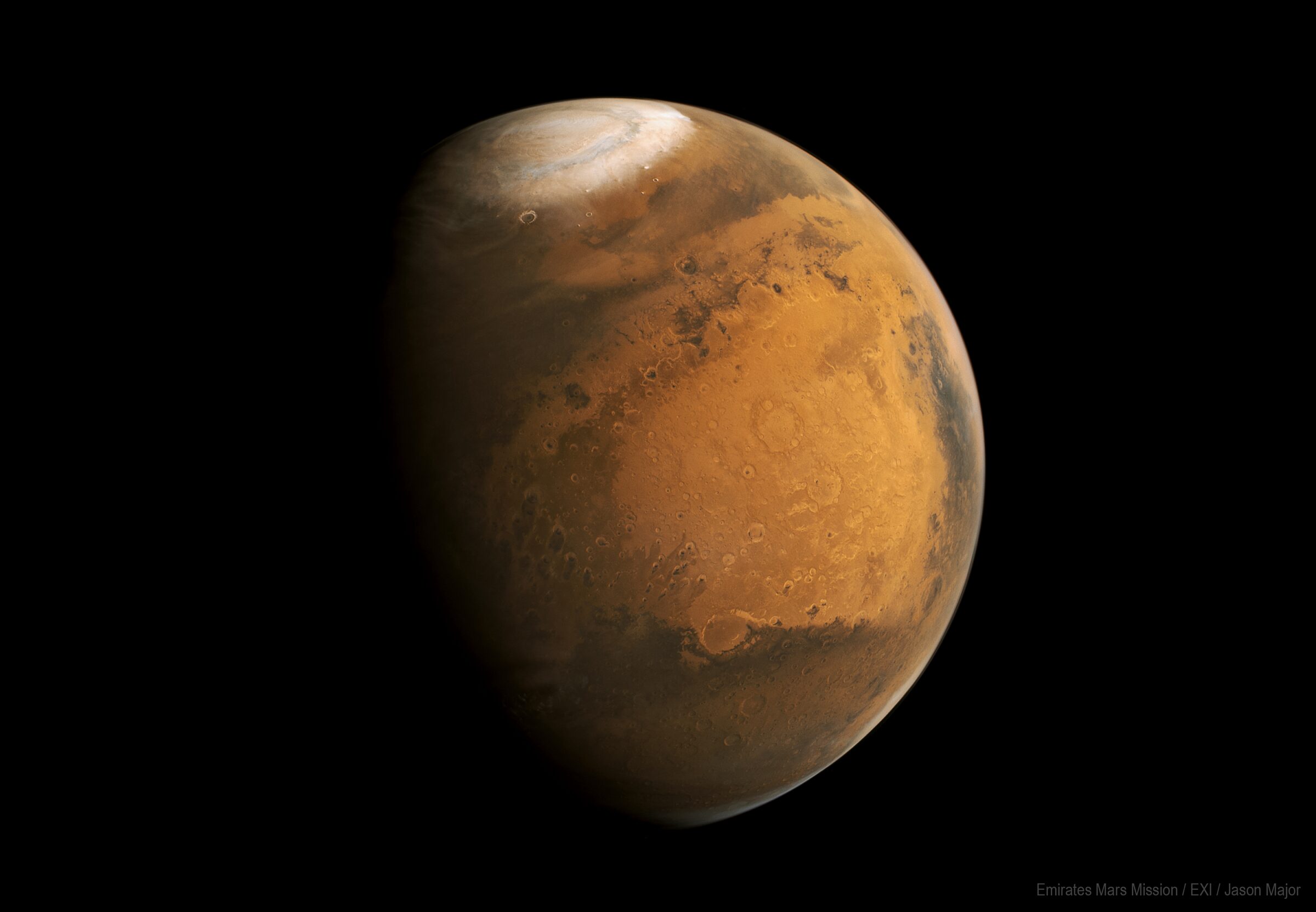

- Hope, the United Arab Emirates' Mars mission

- Japan's H3 to launch Emirati asteroid mission | Space News

- Planetary Radio: Sarah Al Amiri and the new UAE mission to the asteroid belt

- Planetary Radio: Two Years of Hope: Celebrating the Emirates Mars Mission

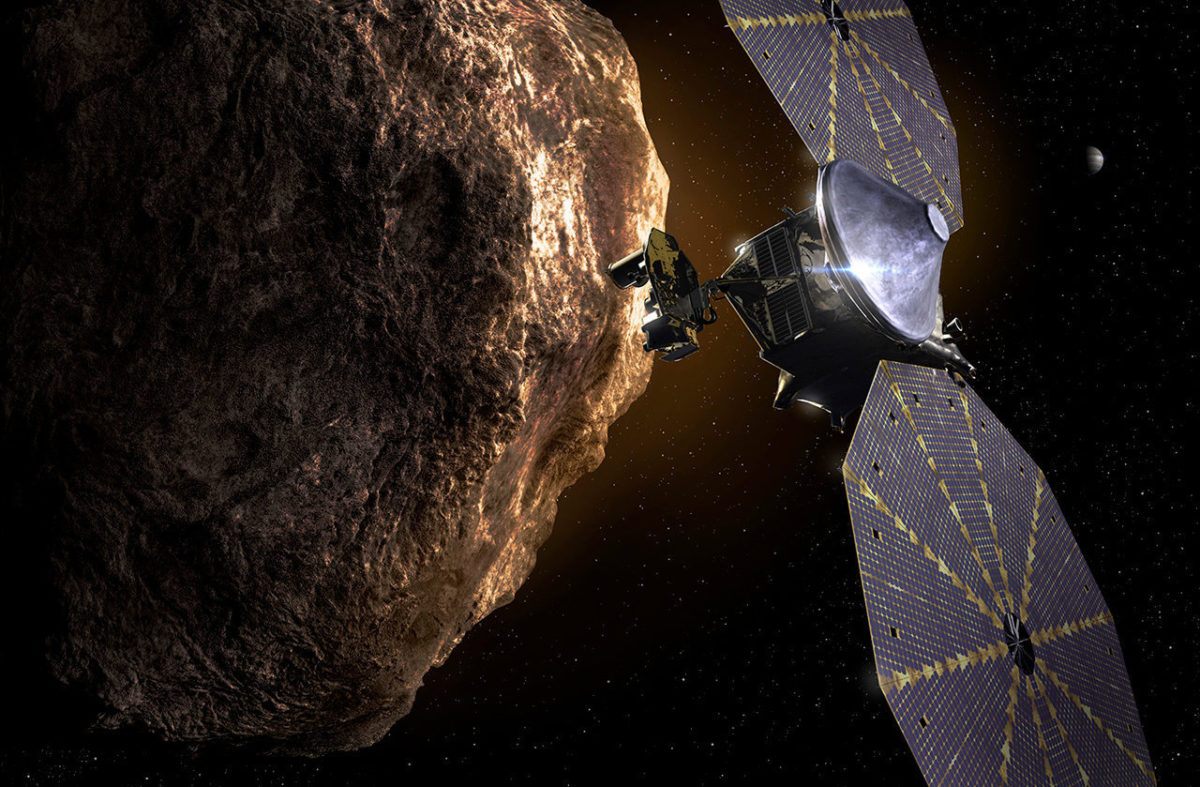

- Lucy, exploring Jupiter's Trojan asteroids

- Lucy’s flyby of Dinkinesh: Everything you need to know

- CLPS: NASA's commercial Moon landing missions

- What are asteroids made of?

- Hayabusa2, Japan's mission to Ryugu and other asteroids

- OSIRIS-REx, NASA's sample return mission to asteroid Bennu

- Psyche, exploring a metal world | The Planetary Society

- Gene Shoemaker Near-Earth Object Grants

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

The United Arab Emirates aims for the asteroid belt, this week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond.

In 2020, the United Arab Emirates Space Agency launched its first interplanetary mission, the Emirates Mars Mission they dubbed Hope. The Space Agency is now working on its next ambitious mission, the Emirates Mission to the Asteroid Belt. It's going to visit seven asteroids culminating in a strange world known as Justitia. We'll get an update on their progress from Mohsen Al Awadhi and Hoor Al Maazmi, the director and science team lead for the Emirates Mission to the Asteroid Belt. Then our chief scientist at The Planetary Society, Bruce Betts, joins me for What's Up and a new Random Space Fact.

If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it.

Here in the United States, we're coming up on Thanksgiving. It's a holiday where we reflect on gratitude, and I'm so grateful for everyone listening. Next week is going to be my 100th episode as host of Planetary Radio. That's a massive milestone in my life, so if you have any ideas on how I should celebrate, let me know. I'm still trying to figure it out.

In other celebratory news, November 27th, which is the air date for this episode, is our CEO Bill Nye's birthday. I hope you'll join me in wishing one of our favorite science guys another happy trip around the sun. The Planetary Society will share some posts on Facebook and Instagram and in our member community if you want to leave him some well wishes.

And a few days later on November 30th, The Planetary Society marks its 45th Incorporation Day. That's the day that our founders, Carl Sagan, Louis Friedman, and Bruce Murray sat down and signed the paperwork that officially began our organization. Fun Fact, the desk that they used to sign that paperwork still sits in Bill Nye's office all of these years later. Sometimes I'd like to sit at that table and think about how different the history of space exploration would've been without the signing of that document, but that's a story for another day.

We'll officially kick off our year-long 45th anniversary celebration in January. Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, the United Arab Emirates Space Agency, which celebrated its 10th anniversary this year, is gearing up for its next big adventure, a mission to the asteroid belt. Their first interplanetary mission, the Hope orbiter, is still out there studying the Martian climate and helping us understand what Mars was like when it had an atmosphere and could have supported life.

Hope was the first interplanetary mission from an Arab or Muslim-majority country. The UAE used it as an opportunity to team up with universities and space agencies around the world, and that gave them the skills that they needed to succeed as an agency and reach Mars. And now they're working on their next big project, the Emirates Mission to the Asteroid Belt. Much like NASA's Lucy mission, which is going to investigate multiple asteroids, the Emirates Mission to the Asteroid Belt is designed to fly by various targets, but instead of visiting Jupiter's Trojan asteroids as Lucy will, the UAE's mission is going to focus on seven bodies in the main asteroid belt. That's the belt of objects that's located between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter.

The Emirates Mission to the Asteroid Belt is going to investigate a few different types of asteroids before it rendezvous with its final target, Justitia. It's been three years since we got a chance to discuss this mission on Planetary Radio, so it's definitely time for an update.

Now, Mohsen Al Awadhi, the director of the Space Missions Department at the UAE Space Agency and director of the Emirates Mission to the Asteroid Belt, returns. He'll be joined by Hoor Al Maazmi. She is a senior space science researcher at the UAE Space Agency and the science team lead on the Emirates Mission to the Asteroid Belt.

Thanks for joining me. Hoor and Mohsen.

Hoor Al Maazmi: Thanks for having us.

Mohsen Al Awadhi: Thanks having having us.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And it's good to speak with you again, Mohsen. It's been a couple years since we spoke about the Hope Mission.

Mohsen Al Awadhi: Yeah, it does feel a while ago with so much action happening.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Especially with this whole new mission you guys are spinning up. I mean, I know that you began working on this quite a while ago, but I'm sure there's been a lot of developments in the meantime and there's so much going on at the UAE Space Agency. It's been really wonderful to see the planning for these upcoming missions, but just the interactions between the space agency and this growing commercial industry around it.

Mohsen Al Awadhi: Exactly. The essence of every single program that we have is the international collaboration is definitely one of the main aspects that we are building through these space missions, given that we're looking into collaboration from the science point of view, from technology point of view, knowledge transfer point of view. And these are, to us, the pivotal tools, space missions to create that ecosystem not only on the UAE but internationally. And we've been successful with all of our missions by following that methodology, and we continue to build that and we continue to build future programs based on that methodology as well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, for people who aren't familiar with this mission or didn't get a chance to hear the last time we spoke about it, can you give a general overview of what this mission is going to accomplish and where you hope it'll visit?

Mohsen Al Awadhi:

Sure. I'll talk about the overall objectives of the mission, and I'll let Hoor Al Maazmi here too to dig deep into the science that is behind the mission and a driver of the mission as well.

So this mission, the Asteroid Belt mission, the Emirates Mission to the Asteroid Belt was initiated after the successful launch and achievement of the Emirates Mars Mission. That was our first deep space mission, visiting Mars. And the growth that was seen in the UAE from the academy point of view, from the state sector in general as well and from being able to attract entities that previously did not think the UAE might be a hub for future missions, all of that was created by EMM. And it was obvious, we need a follow-up mission that can continue attracting these individuals. And also the youth that was inspired through the EMM, we wanted now to give them an opportunity to be able to be part of new mission, the Emirates Mission to the Asteroid Belt.

And that is the mechanism that the whole mission was built on. It's not dedicated to one entity to develop this machine. We created a concept called the national team where we have different individuals coming from different sectors in the UAE and are creating what we're calling the national team. So we have individuals from the space agency itself that are allocated working full-time on the mission. We have individuals and team members from TII, we have from UAESA that were part of the mission. We have universities, maybe four universities that are officially with us. So this concept was really needed to be able to give this opportunity to more than one entity.

And not only that, we did not stop by only creating the national team, but we are also supporting startup companies to have an opportunity to take a part on this mission. Taking a huge risk by introducing this opportunity, but the goal of the mission and a mission objective that we have, that 50% of the mission has to be developed in the UAE.

So to be able to do that, we needed to create that ecosystem in the UAE. At the same time, be sure that they're ready to be part of this mission and also for it to be successful. And we know not all of these adds up, especially if you're trying to do all of this at once. So we took the approach of, "Okay, if you are a startup company, you don't have enough knowledge, but you have the passion to be such a program. You come with us, we have another program that was initiated called the Space Academy that will give you, let's call it, the basics and things you need to be able to know so that you have a successful journey in the mission," giving an equal opportunity to the sector that is established and then giving another opportunity to the startup companies at the same time looking at more collaboration internationally.

So one of the mission objectives, again, to build this relationship, the international relationship. So we took the approach of having this mission accepting contributed payloads. We have contributions from the Italian Space Agency on this mission. Universities in the US will contribute to the mission.

And then the last part that I also want to talk about is there's an opportunity for a UAE team to develop a lander on the mission. Two years ago, three years ago, we called it the Lander. Today we are changing that. It'll probably be an impactor. It will not survive the impact that it will has to go through. But again, we're building our capabilities through this opportunity that is the lander opportunity/impactor. So the risk tolerance on that is quite high from our side. But the essential goal again here is to build capabilities of the UAE on a complicated piece of the mission as well, which is the lander/impactor part.

Today we have an entity selected, so startup companies provided us this concept. They got it from a pre-phase AD to a mission-concept review phase successfully. And now that concept has been adapted by an entity in the UAE. We have not finalized it yet, but we will be announcing it soon as well. And that part will be developed in the UAE.

And then maybe one last update, at least from my side, is looking at the launch vehicle that's been selected as well as of a month ago now. So we chose the Mitsubishi Heavy Industry, the H3, the new launch vehicle, for it to be the launch vehicle for this mission as well, which will be launching in 2028, the first quarter of that year. So that's in summary, I think, what we've been doing and details on the science. And the payloads, we can go into that.

Hoor Al Maazmi:

Yeah, we were all very excited for this mission and we're excited to go further in the solar system with this mission and to achieve these big objectives that we have, not just for science, but for the country and the UAE globally.

But the science for me is very exciting as well. We have really exciting science that is going to be useful for the global science community that are interested in learning about asteroids and interested in understanding more about the formation of our solar system.

So we're visiting seven asteroids. We have six flybys on this mission and we'll rendezvous with a seventh asteroid. That's very exciting because it's the reddest object in the main asteroid belt, and we're curious to know why it's the reddest object. We don't really know what is causing that redness, which is why we're getting a closer look at it.

Our mission has two sides to it in terms of what we're studying. We're looking at science objectives of understanding the origin and evolution of water-rich asteroids, and we're also interested in paving the way for future missions to utilize resources that are found on asteroids. So this is a longer term ambitious goal for future missions as well to support space resources objectives, as we call them, where we're trying to see how many resources can we find on the asteroids that we're visiting and how usable are they or how easy are they to extract for future missions?

Going back to the science, asteroids in the main belt are very interesting because the main belt acts as a historic remnant for when the solar system was forming. So by going to the main belt, we're going to be learning more about that period when the solar system was forming. And by looking at water-rich asteroids, we'll get to know where water came from on the planets that exist in the solar system today and on Earth.

So we're getting a closer look with our instruments that Mohsen mentioned that some of them are contributed from the Italian Space Agency, some of them are from the US. Each instrument is looking at different aspects of the asteroids so we're trying to get information on the composition of those asteroids. We're trying to get geological context with our cameras and we're trying to get thermophysical and thermodynamic properties of these asteroids that we're visiting. And our final asteroid, 269 Justitia, is the reddest asteroid in the main belt, and it looks like the redness indicates water richness and organic material on the surface so we're really excited to get there and to see those details with our instruments.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Why do we think that indicates that it's a water-rich asteroid?

Hoor Al Maazmi: So the redness of the asteroid indicates organic material on the surface, and that tells us that there might be water below the surface, so subsurface water. And these asteroids generally that have a similar spectra of signature are typically found in the outer asteroid belt in the Kuiper Belt. So it does also have signs of it being a asteroid that migrated from that outer belt in the solar system and moved to the main belt. But we're still curious about why it maintains its redness and how it hasn't lost its redness during its migration, and what are the causes of that, whether it's space weathering that's causing this redness or the water richness or any other aspects that we're going to be figuring out with our mission.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

Yeah. Justitia is a really strange asteroid, and I was so excited to hear that was going to be the final target for this mission because there's so much we can learn there. The fact that we think most of the water on Earth came from asteroid bombardment is one thing, but also just the prevalence of organic materials we're finding in these objects in the samples that we're retrieving from other asteroids, it's kind of mind-blowing and the more we can know about it, the better I think. And getting a look at seven different asteroids is going to give us a much better idea, especially when we can combine them with other data.

Are you working with any other teams from other countries that have done this kind of asteroid sampling or upcoming missions to asteroids to collaborate on this kind of thing?

Hoor Al Maazmi:

Yeah, so we're currently working with team members that have experienced or are also team members from the Lucy mission, from the Southwest Research Institute, so SwRI. We have a few members that are from that team and they've also been supporting a lot with the Earth-based observations.

We recently had, last year in August, a stellar occultation campaign. These campaigns were mastered basically by the Lucy mission team because they had so many campaigns where they try to better understand the asteroids that they're going to. So they helped us out with their experience, as being part of the science team of this mission, set up a stellar occultation campaign for just a rendezvous target, and it was wonderful.

These stellar occultation campaigns typically are a group of telescopes that are distributed across the shadow of the asteroid when we know it's going to pass over Earth. So by distributing these telescopes across the shadow of Justitia, we can better understand the shape of the asteroid. It will increase our understanding of the shape model basically of the asteroid, and it'll help us with our planning for getting to Justitia. So that was really exciting. And it also helps us with trying to see if it has a secondary asteroid and getting albedo information on the asteroid. So we had that campaign last year and we got really amazing results that are very useful for our mission, and we're planning a lot more for our other fly-by targets and for Justitia as well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But you have so many targets. How are you going to be navigating between these asteroids as you're out there?

Mohsen Al Awadhi:

For the navigation aspect, specifically on the Emirates Mars Mission, we definitely have heavy dependence on and team that can provide the service, the navigation specifically when we go to a deep space program.

One of the knowledge transfer aspect of the Emirates Mission to the Asteroid Belt was to start developing things in-house. So the full navigation system of the asteroid belt mission is now being co-developed with the university in Colorado specifically because it was one of the items that we selected as a team and as a space agency saying, "Okay, now that we are upgrading and going even further, what are one of the areas that we should be developing or co-developing that builds the knowledge and capabilities?" And when you're developing in yourself, the amount of knowledge that you need is a lot more than being able to depend on an entity who does that for a living.

So that's when it comes to the mission design. Definitely it's a complex process, but we're making it even more complicated by designing and developing our own navigation system. So we continue working with that relationship that was built on the Emirates Mars Mission, and we are making it even a stronger partnership that we are getting out of the asteroid belt mission.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So you're going to be doing flybys of most of these bodies, but when it comes to Justitia, you're going to try to actually either land or impact this object. Is the larger spacecraft going to be attempting to go into orbit around this object, or are you just going to kind of flyby and drop off this lander?

Mohsen Al Awadhi: No, so from the science point of view, we will be rendezvousing it for, I think... What was the timeline for... Is it nine months?

Hoor Al Maazmi: Seven months.

Mohsen Al Awadhi:

Seven months. So seven months we will be orbiting the last with close prox operations as well on Justitia. And the last operation of that, once we're done with the science and we collect the information that we're looking forward to having, that's when we'll be attempting the lander opportunity, the landing of the impactor today on Justitia.

We still have not defined how close we will be getting, but out of the current stage and the mission design that we have, that's why we moved from calling it a soft landing into probably it will impact and probably not survive as well once it touches the surface. But again, those details have not been finalized yet, but we are still working on getting it closer. But the whole goal of the landing opportunity is to take as less risk as possible on the mothership, on the NBR Explorer just so that if we can again continue doing more science, then we can continue doing that as well. But again, those details have not been finalized yet. But soon enough, a year timeline from today, we will have a more solid plan that this is what we will be looking at because that's when we enter the AIT phase, the assembly, integration, and testing phase where we freeze as much as possible of the design so we can start testing the different scenarios and the spacecraft itself as well, plus of the mission scenarios that we have put in place.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, there's a few things that I think the impactor does for your team that is actually quite an asset. I mean, first off, impacting it means you might be able to excavate some of the material and get a better understanding of what's going on under the surface, but we've also seen in the United States this difficulty with the commercial lunar payload services program that NASA is doing. The collaborations with these new startup companies and other companies that have been going on for a while are wonderful, but anytime you try to land something, it's always really difficult. Space is hard, right? And I'm never upset when these companies don't nail it the first time because that's a really complex thing. But I was concerned when I heard that you had startup companies attempting this, not because I thought they were going to fail, but because that is a really complex task. And when a company hasn't had that opportunity before, there's a high likelihood it might not work. So having an impactor instead of a lander actually sounds like it's a really good decision, if it goes that way.

Mohsen Al Awadhi:

Exactly. And as you mentioned, I mean this whole concept of introducing startups to a flagship mission, we understood what risk we need to be tolerant with. It was obvious. But at the same time, this mission is trying to achieve so many different things on the national objective level that we want to make sure that everyone understands today in the UAE. You get an opportunity even on a flagship mission. I mean if some other countries might treat these missions as zero-risk tolerance as much as possible, there is no zero, but reduce it as much as possible. We're actively doing something the opposite, that we are willing to take more risk as long as we're able to move and create job opportunities, create an ecosystem or an environment in the UAE that makes anyone that is thinking about this, having an entity in the UAE or startup confident that the UAE space agency or the space sector in the UAE will give them some opportunities here and there.

We created something called the Space Means Campaign, and we have a specific one called the Space Means Business campaign, where we go out and let people know about the different opportunities that exist on the mission. And again, this whole thing is a risk management that we look at who's able to provide what, can we accept this risk, is it too risky, is it the risk that we can deal with and so on.

And then back to the lander opportunity, yes, that's what we have done. We were able to bring on two startup companies, have them work together, get us to the mission concept review phase, which on itself as an achievement that was successful. And also what we did to help them be guided. We had a collaboration with JAXA, the Japanese Space Agency because they have a lot of experience in this field as well. And that's, again, parts of the international collaboration that we are trying to create out of this mission where we have them part of the review board and they give their guidance and feedback to the lander team as well on what is a good idea, what is to be avoided, simplifying the system versus making it too complex.

So all of that collaboration is always beneficial, and that's again, that's the motto that we have that whenever there's something we're introducing to the mission that we don't have information or knowledge about, we are the first one to raise our hands and say, "Okay, we need help. Who can help us?" So a closed relationship with Japan here specifically was needed, and they were part of that review process and they give their guidance to the team for it to be a successful mission concept review.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, that's a really great tactic, honestly. The collaboration with all of these existing teams gives you that safety net that you need, but I think it's really important to be able to take the risks to give these opportunities to people in the Middle East. And as someone whose family comes from the Middle East, and my father lived in Dubai for a long time, when my little sister learned about the Hope Mission, it lit her imagination on fire, as I'm sure it did for people all across the UAE and the Middle East. If I still lived there, I would be trying to join this team. That is an opportunity that you've granted everyone. So even if it doesn't go the way that you want it, I think it will pay dividends in the people that you've given opportunities to and what it might be able to build in the future.

Mohsen Al Awadhi:

No, exactly. And it's not only the technical aspect that we want people to be aware that you have an opportunity on. It's the whole spectrum. So whatever you think you can do for a space mission, we are opening that opportunity up.

So we're glad that this is having that impact. We continue to work towards having that impact as well because, again, Hope Mission was to create that hope. Today I think that hope, we see it, a lot of people have that ambition. A lot of individuals in the UAE are now focusing on knowing that space is absolutely a career path not only from space missions, but also on a human side, human space flight side as well, being an astronaut, which again, 10 years ago probably that's not anyone that thought that, "Okay, my career path would be being an astronaut" within that 10 years or even less than that. Today it's actually a real job that you can apply for or train for.

So we continue to establish an infrastructure that is going to be taken over by the next generation. And whatever opportunities that we can give for anyone to be able to be part of this today, then that's the goal that I personally take pride and I hope that I'm able to achieve it through these missions.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What's really beautiful about these kinds of missions is that it's not even just building opportunities in the moment, but once you actually have that data, it can pay off for decades after and create all kinds of jobs. We've seen that with so many missions from around the world, people who were not even born when spacecraft went out later becoming part of the teams that then digest that data. So what kind of data are you going to be collecting from these asteroids as you're going along?

Hoor Al Maazmi:

So as mentioned, we have five instruments on board the spacecraft. We have the Emirates Main Belt InfraRed Spectrometer, EMBIRS, and it has heritage from the Emirates Mars Mission where we had a very similar, the exact same instrument actually, called EMIRS that's currently orbiting Mars. But this one will be for the main belt on our mission.

And then we also have EMACS, which are the EMA camera systems. We have an infrared camera and a visible camera, visible narrow-angle camera. So to start-off, the infrared spectrometer is going to be there to give us infrared data, so temperature and thermophysical properties. The camera systems with the visible narrow-angle camera will give us geological context for the thermophysical properties and the composition and information that we're going to be seeing with our other instruments. And then the infrared camera is also going to be giving us information about temperatures and the subsurface layers and the rock abundance and porosity of the asteroids that we're going to be seeing.

And then we also have the mid-wave infrared spectrometer called MIST-A, and this is the Italian Space Agency-contributed instrument. And this spectrometer is going to give us compositional information about the asteroids that we're going to be flying by and Justitita.

And then finally, along the way, while we're traveling from Earth, the entire cruising time will be collecting data with the REPTile-3 instrument, which is a Relativistic Electron and Proton Telescope, and it's going to be collecting information about the solar energetic particle environment and space weather environment along the way. And this is really exciting because it's going to be collecting data about the solar environment in places that data hasn't been collected before by traveling to the distance that we'll be traveling with our mission

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

And in some happy fashion, it'll be a few years after solar maximum, so you won't be getting completely bombarded. But that data is really important. We're going to need that.

We'll be right back with the rest of my interview with the team behind the Emirates Mission to the Asteroid Belt after this short break.

Asa Stahl: Hi, I'm Asa Stahl, science editor from The Planetary Society. Stargazing is our everyday window onto the universe, but only if you know how to explore the night sky. Join me in a new online course from The Planetary Society where we'll discover the wonders waiting to be seen overhead. No matter where you live or whether you want a telescope, this how-to guide will transform the stars into a clear view of the universe. You'll learn practical skills for parsing the night sky, get tips on how to see the best possible views, and hear the latest from professional astronomy communicators on how to help others fall in love with stargazing. Everyone from newbies to space nerds are welcome. Remember, this exclusive course is available only to Planetary society members in our member community. So join us today at planetary.org/membership. That's planetary.org/membership.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It sounds like Justitia is a target that we at least know a good amount about, but what do you think are the most interesting things about the other six targets that you're going to be visiting, at least that we know so far?

Hoor Al Maazmi:

Yeah, so I was really excited to see that when we share this mission at conferences and with people, that people aren't as excited about Justitia as we are, but they're more excited about the fact that we're visiting asteroids that are within asteroid families.

So the asteroids that we're visiting, five of them are within asteroid families with one of them being the largest remnant of the asteroid family that it's in. So Chimaera, so named after the Chimaera family. Chimaera is an asteroid that we're visiting and we're going to be getting more information about. And we're also visiting different types of asteroids. So we're getting the diversity aspect of the asteroids and the asteroid belt also ticked off. So one of the asteroids that we're visiting is a mixture of asteroid types, so it's a mixture of carbonaceous and ordinary chondrites mixed together. So that's going to be really interesting to see that asteroid and why... So it's probably because of an impact that caused these two types to be mixed together, so that'll be really exciting to see.

And then we'll be visiting five carbonaceous asteroids and two of these asteroids are C-types, one is a K-type. And our ultra-red asteroid, 269 Justitia, is also really exciting.

So we're excited about the fact that we're visiting asteroid families and the context that these asteroid family members are going to give us for their entire family as well, and what state will find them in when we get to them and the story behind those impacts.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's going to be so valuable to get data on all these different classes of asteroids because there is so much we don't know. Every time we approach one of these asteroids, there's some kind of thing we did not anticipate, right? It's a rubble pile, it's a binary, it's got organic compounds on it. I think there might be some surprises along the way. And then how cool is that going to be? What are you personally most excited to learn about these asteroids?

Hoor Al Maazmi: For me, I think the long-term, I would be really excited to learn that one of them is a binary and that maybe we get to name an asteroid that we see with our cameras. That would be really exciting. But I think just getting context for the larger picture of the main belt and the asteroids that are within the main belt would be the best-case scenario is something that will serve the entire small bodies community and will give us answers to big questions. So that's what I'm really excited about, is it might not be the obvious things that we're looking at with our main objectives, but just accidentally uncovering something that we didn't expect to uncover is something that I'm really excited about and I'm sure is going to happen with our mission because there's a lot that we don't know about these asteroids, and just by getting there, we're going to be learning something new.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I still use images from Hope as my background on my computer all the time, so it's going to be really cool to have a whole new catalog of imagery of these asteroids because we only have so many bodies of these small bodies that we've visited. This is going to massively expand our database. So I think this is going to be really cool. Are you going to be putting all of the images out online as they come out? Are you going to be curating them?

Hoor Al Maazmi: They're definitely going to be shared with the public at one point. We'll have a public database for sharing this data to the public. I don't know what the timeline will be for that, whether it's when we immediately get them or before we get to ingest them and understand what's going on with our data and then sharing it with the public. But it'll definitely be publicly available.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: This is just such a massive undertaking, but I've been really impressed with the way the UAE Space Agency has just kind of stepped into this world of space exploration over the last decade or so and completely blown everything away. Everything has been really successful so far, so I've been very impressed and I'm really looking forward to the way that this turns out. And the way that you've done this is by leveraging your partnerships with other universities and other space agencies around the world. But I remember reading, I think both of you spent time at the University of Colorado Boulder. Is that university a part of this collaboration as well? And what other universities are participating?

Mohsen Al Awadhi:

Yes, specifically the University of Colorado as a main university that we're working with, specifically their laboratory [inaudible 00:34:16], that's our direct relationship. And both me and Hoor, we both actually studied together for our master's degree. That opportunity came in, I mean, when we both started working on the mission in the 2015 PAMELA with the beginning of the mission. And then closer to the end of it, we were also given an opportunity by the space agency to see if anyone is interested in continuing their education. So me, Hoor, plus a couple of other guys applied. I mean a lot of us applied and us got accepted. And it just happened to be we were at the right time in the right place. Maybe not the right time because it was a really heady time to be working full-time on the mission and at the same time trying to get our higher education done, getting a massive degree. So that's what happened, at least, with us being graduates from the university.

And then back to the EMM specifically, the collaboration was again with the Arizona State University, Berkeley, University of California. And on this mission, so again, Northern Arizona University and also the Arizona State University and UC Boulder. Again, we are working with them as the main team that is working on the knowledge transfer aspect of the mission. And this time even on EMM, we had UAE or local universities. On this mission we wanted it to be a little bit more involved than being a high-level participant on the mission. So we have, as of today, Khalifa University in the UAE is part of the mission. UAE University is also part of the mission. Recently, Hoor and her team have been adding new universities and we almost finalized, but NYUAD, New York University in Abu Dhabi, is also now an official team member of the science team that's working with us.

Hoor Al Maazmi: Also at Colorado School of Mines, who's responsible for the [inaudible 00:36:17] space resources objectives of our mission. So they're going to be helping us achieve them with our payloads currently.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

It's going to be really cool to see how all these collaborations come together, but I'm just so excited for everyone at universities in the UAE that are going to get to work on this because I'm sure there are so many people that had all these space dreams, didn't know what they were going to do with them, and now they can stay in their country and put their space goals toward this mission and toward whatever UAE Space Agency does next. It's going to create a whole new generation of people who decide to go into this career rather than pursuing other forms of engineering, even if they don't stick with it, right? I think that's a powerful thing to do for people and could, in the long run, really change the economics of the UAE with the people coming through this program, but also all of the industry that builds up around it.

Have you seen a broad interest from these universities and companies to join this? Or is it something that they're a little reticent to do because it's unfamiliar?

Mohsen Al Awadhi:

In general, me personally, when I started visiting universities at the early stage of the mission, every single university said, "We missed the opportunity on the Emirates Mars Mission, and we want to see what would it take for us to be able to be part of this." Now, that's the beauty of it, that yes, the passion is there, but now when they know, "Okay, what will it take for you to be part of the mission, the challenges, the complexity," some people change their minds. Some university were like, "Okay, this is maybe too much for us. Can we do something different? Then maybe a CubeSat program with them or something that is more within the scope of work that they have that we continue doing that with them as well, is not only this opportunity.

But having such a thing as we mentioned, I mean people in general, when you say space, everyone has your attention. But when you go to the detail of what would it take and reality kicks in, and sometimes also the budget needed and knowing that the space agency really operates on a highly limited budget and no one believes that until we actually start working together and they're like, "Oh, okay, you meant it. The budget is really limited," then things change as well. But again, we make sure that we are finding opportunities through the Space Academy, for example, from CubeSat Educational, CubeSat programs as well, as long as you are interested.

And then we end up with also university that no, they see the benefit of this and the approach that we have that if you're finding an interest on this mission, take this opportunity and you need to be self-financed as well. Because again, as I mentioned, all of the budgets that we have are truly limited, and that's why we always work towards the contributed collaboration methodology that we want more teams to be working on the same goal and the space agency will de-risk it as much as possible. But for us to create an ecosystem that becomes so sustained as well, we need the ecosystem to understand the importance of it.

So we're able to successfully do that with so many different team members that we have. The creation of national team is based on that methodology as well, and it's becoming a really successful story that I would not repeat it knowing the complexity that it goes into it and managing team members from different entities with different cultures. It's definitely a challenging task, but when you look at the end goal and what you will be creating out of this dynamic team, that's exactly what the space sector needs here in the UAE.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And then perhaps one day as more nations within the Middle East form their own space capabilities, they'll come to you and you'll be the advisors that help them through their beginning journeys as well.

Mohsen Al Awadhi: We have some success stories in that as well. So the Bahrain Space Agency's equivalent, that is a program called Light-1 that was purely based on that collaboration methodology as well, where we had the team from Bahrain come to the UAE and work with the Space Agency and Khalifa University and NYUAD, New York University in Abu Dhabi, and we were the knowledge transfer team that provided the knowledge to the Bahrain team. And today that mission was successful. It's, again, it's a CubeSat level. But whatever we're learning, that's the goal that we have. As soon as we learn it, we want to pass on the knowledge to showcase the importance of why is it the UAE is looking for this knowledge and how can the UAE give back as well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: See, that's the magic of space exploration right there. The power of international collaboration, all of us working together towards self-betterment. Even if these missions don't succeed, the technologies that they build, the knowledge base that they build up is so powerful. But given the complexity of what you guys are building right now, what do you hope the UAE Space Agency is going to be able to accomplish after you've achieved this? Because I know it's a little too early to say what your next mission is going to be probably, but you can probably get a pretty good idea of where you're heading.

Mohsen Al Awadhi:

Of course. So this mission is specifically, I mean, it's a long-term mission. As of today we have 12 more years before this mission is decommissioned, which is in 2035 approximately. That's when we will be done with the science phase and we're done with a landing opportunity. So it's definitely a long-term program that has been built to support the ecosystem.

And of course, before we get to the end of that program, we need to know, "Okay, what is the next?" It'll be the same methodology that we follow whenever we create any new program. What are the objectives we're trying to fulfill? It'll always be built on supporting the international science community. We always start with there. If we are going to invest into a program and the UAE space agencies to fund the program, what questions are there that is hindering that no one is answering yet or no program is able to answer it yet can the UAE support with? So that's what who and their team comes, that this is what they start with.

Once we understand that, okay, we put a program together that, "Okay, for this to be achieved, this is the mission that we would need." And then we also try to be selfish, "Okay, what are we going to need for the UAE? What does the UAE want to create to develop? What ecosystem we will be having, let's say five years from today?" And it'll be obvious to us, "Okay, this is what we want to strengthen." So these are the basis of any program that we have, capability development, science aspect, and also what opportunities can this mission or program give, if a commercial entity, for example, to be able to utilize this opportunity to learn things that in the future they can become their own standing up entity that they can actually sell products. And we have successful stories on that as well.

Hoor Al Maazmi: I mean, yeah, I'm really excited to see where we'll be with universities, with the people that are going to be participating on the science team of this mission and how they'll develop the capabilities locally. Because with the Emirates Mars Mission, after launch, we saw a huge difference. And after we got data and we had people work on the data, we saw a huge difference between that time and before the mission even existed in terms of space science. People are interested in going into planetary science as a career and astrophysics locally, and I'm really excited to see what that's going to look like after this mission.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

Yeah, I just want to know more about these asteroids and what they could mean for future resource utilization and humanity's ability to travel out there into space. There's so much we don't know. And if we want to go beyond our world, we're going to need the resources to do it. So this could be a pivotal mission in the history of human space exploration. We just don't know yet.

Have so much luck in building this. I hope it brings so many opportunities and so much joy to so many people. I really appreciate your time and good luck going forward. Can't wait to speak with you in the future.

Mohsen Al Awadhi: Likewise. Thank you so much.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

And now it's time for What's Up with our chief scientist, Dr. Bruce Betts.

Hey, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hey, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Happy almost Thanksgiving.

Bruce Betts: Happy almost US Thanksgiving Day thing. I am thankful for you, this show, our listeners, and space, and a bunch of other stuff, but that's not what the show's about.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Truth. We talked about asteroids this week, one of your favorite topics.

Bruce Betts: Yay.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's interesting seeing these missions that are trying to target multiple asteroids at once. That's pretty ambitious, even in the case of NASA's Lucy mission, but we'll see how the UAE does. They've kind of crushed it with previous missions, so I believe in them.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, they've been very impressive with their Hope mission particularly. It's good stuff. So I'm looking forward to this. And yeah, Lucy's got a whole pile of, and they even found an extra one when they flew by and found a little moonlet friend.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Dinkinesh? Although I don't think the moonlet has a name.

Bruce Betts: What would you name it?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: No, I shouldn't call it Dinky.

Bruce Betts: No, you should. It is now called Dinky. I will use the bat phone, the IAU phone to get an instant approval of Dinky.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Some listeners of the show will know that we're in the midst of trying to help name a quasi moon of Earth, and those adventures with the IAU have been really fun.

Bruce Betts: They have a challenge to monitor, particularly with the small objects, to monitor all those names.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And as we're finding, there are kind of complex objects. You think it's one thing, and then it turns out it's a binary asteroid. I didn't even anticipate there'd be so many binary asteroids. And we've learned so much about the general population of asteroids over the years that we didn't know before, and I'm sure we're going to learn a lot more now that we've got missions going to multiple bodies at once. The amount of comparative, I guess I can't call it planetology, right? Comparative asteroidology is that what you would call that?

Bruce Betts: I kind of come from the school, which is subjective, that it's planetary science when you're studying anything solar system-related that's not the sun pretty much, although you can argue about the space between objects.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I don't know. Has there been anything that we've learned about asteroids in the last two decades that actually kind of surprised you?

Bruce Betts:

The variety, which is weird because you look at pictures first to look and it's like, "Oh, there's a bunch of gray stuff." But you get into the density and how that varies. And we had some idea of this because of meteorites. You've got like 4 or 5% of meteorites are iron meteorites and are much denser, heavier, therefore for the same size.

But we found what people kind of expected, but it was surprising as the pile of boulders like we see at OSIRIS-REx's target, Bennu, and a big surprise when it shed material off of it at one point. That definitely surprised a lot of people. I don't know about surprises, but DART and how efficient it was, was encouraging from a planetary defense protecting Earth from asteroid impact perspective.

The binary thing has really come to the fore, as you said, in the last 20 years. I mean, you've got roughly 15% of what look like an asteroid when they're discovered, turn out to be binary asteroids, several of our Shoemaker NEO grant winners that do asteroid studies, that's one of the things that a lot of them participate in because you need to look at the light curve over time, the brightness with time, and you can actually see the effect of the little friend, or not little friend, they're similar sized objects as well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How would you tell the difference between two objects and a binary versus one really weird shaped object like a contact binary?

Bruce Betts: You go and you talk to the experts who stare at light curves and they tell you, "Look, this is a light curve of a binary, and this is the light curve of a contact binary." You raise a valid point. Unless we get lucky and an asteroid flies close enough that we can hit it with planetary radar or we actually go to an asteroid, then the main way determined binaries is indeed by just looking at the light curve. And that could look weird and wacky for a contact binary where two asteroids are loosely stuck together, or if you went up and spray-painted half of it to look like something. But you see a repetition in the light curve that is best explained by binary. As with transit method or anything, there's noise and you don't get a perfect line and you take more and more data and you add to it and you can start to see things happen. So it's not usually a, "Oh, boom, that's a binary." It's like, "Hey, let's get more and more data."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's going to be really cool to see all these images and be able to compare all of them. And I'm sure there are some surprises in there that are going to change our understanding of asteroids all over again, just like those rubble pile asteroids. Space ball pits was not on my bingo card.

Bruce Betts: You know what also surprised me? I was just thinking back, was Hayabusa and going to Itokawa was the look of that asteroid looking like it had cornflakes on both ends and someone had licked them off the middle. That's a pretty standard analogy straight out of the scientific literature. No, it's not. But even just that cornflake look, which is kind of popular amongst the cooler asteroids because of the boulders sitting around and the fine material. Anyway, it's amazing what differs they be seeing. Basically, most of them would float around, to use poor terminology. They occasionally slam into each other, and yet you actually have interesting dynamic things going on. It's fascinating. And they also represent a window into the beginning of our solar system as primitive objects. And of course those wacky and metal asteroids.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Man, that's psyche mission. I mean, of all the weird outliers, what we think of as a metallic asteroid, that I'm so excited for.

Bruce Betts: Metallic asteroid, band name, I call it right now.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: You got it, Bruce. We need to start like 50 Planetary Society bands, just cover all these band names.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. Hey, I got something for you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah?

Bruce Betts: It's a Random Space Fact.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: All right. What you got?

Bruce Betts: Well, you're going to the archives, which I try not to do, but don't worry, I'll add to an old Random Space Fact. So out of our Random Space Fact videos that you can find online, we did one in honor of US Thanksgiving. And we had the Random Space Fact that if Mercury were the size of a cranberry, then Jupiter would be the size of a Turkey. But now I'm going to add in there that Earth would be about the size of a walnut. Now still in the shell, which is not the ideal way to include it in stuffing. And frankly, I don't think that should be included in anything, but that's just a personal opinion. And that would be your Thanksgiving analogy for the day.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'll be thinking about that while I'm making food.

Bruce Betts: Well, I was thinking about the amazing creation of the turducken, chicken inside a duck, inside a turkey. And so I was thinking, what if you took the giant planets and you put Uranus inside Saturn inside Jupiter, and you'd end up with something like a Jupisaturanus. Jupisaturanus. There we go.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Jupisaturanus. Definitely weirder than the piecaking I was thinking about making.

Bruce Betts: What's that?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: You put a pie inside of a cake.

Bruce Betts: Oh, now we're talking.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right?

Bruce Betts:

Totally. You can put cookies inside of that and coat the whole thing in chocolate. Let's party.

Hey everybody, go out there, look up at night sky and think about yummy foods that you combine into magical, weird sounding things and have a wonderful Thanksgiving. Whether you're here, elsewhere, we're all grateful for your listening. Thank you and good night.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week to discuss the formation of araneiforms or what some people like to call the spiders on Mars. Don't worry, they're not actual spiders. Just really strange bits of terrain.

If you love the show, you can get Planetary Radio t-shirts at planetary.org/shop, along with lots of other cool spacey merchandise. Help others discover the passion, beauty, and joy of space science and exploration by leaving your review or a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day, but helps other curious minds find their place in space through Planetary Radio.

You can also send us your space thoughts, questions, and your poetry at [email protected]. Or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the Planetary Radio space in our member community app. And please, let me know what I should do to celebrate my 100th episode.

Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California and is made possible by our members, some of which have been with us for 45 years. Shout out to the charter members.

You can join us as we celebrate space missions from all around the world at Planetary.org/join.

Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. And until next week, I'm thankful for you and ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth