Planetary Radio • Dec 11, 2024

StarTalk with Bill Nye and Neil deGrasse Tyson

On This Episode

Neil deGrasse Tyson

Astrophysicist and Director, Hayden Planetarium

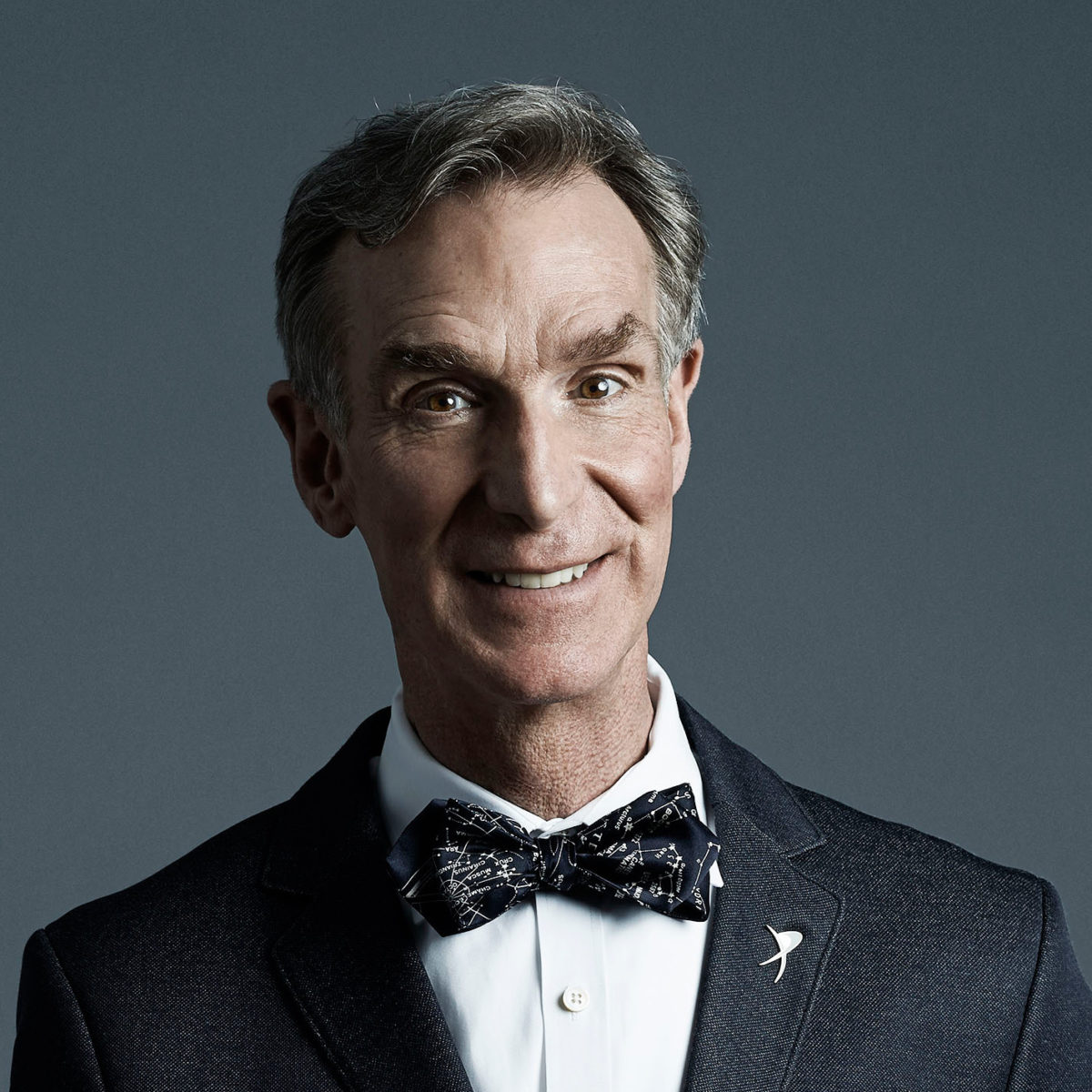

Bill Nye

Chief Executive Officer for The Planetary Society

Jack Kiraly

Director of Government Relations for The Planetary Society

Casey Dreier

Chief of Space Policy for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

We take you to Planetary Society headquarters, where Neil deGrasse Tyson, astrophysicist and host of StarTalk, interviews Planetary Society CEO Bill Nye about the organization's 45-year history of empowering the world's citizens to advance space science and exploration. Then, we share an update on the incoming Trump administration's proposed pick for the next NASA Administrator, Jared Isaacman. Planetary Society Chief of Space Policy, Casey Dreier, and Director of Government Relations, Jack Kiraly, give us the details. We close out with Bruce Betts as he discusses the Van Allen belts and shares a new random space fact in What's Up.

Related Links

- StarTalk

- StarTalk: Journey to the Stars with Bill Nye

- Who is Jared Isaacman, Trump’s proposed NASA Administrator?

- Planetary Report

- SPE: Human Spaceflight as a Religion

- The Day of Action

- Countdown: Inspiration4 Mission to Space

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Bill Nye and Neil deGrasse Tyson reunite this week on Planetary Radio.

I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. What happens when you put a beloved science educator in a room with one of the greatest astrophysicist communicators in history? Friendship, that's what.

This week, we share part of The Planetary Society's CEO Bill Nye's conversation with Neil deGrasse Tyson, the director of Hayden Planetarium and co-host of StarTalk, the podcast where science, pop culture, and comedy collide.

Then we'll get an update on the Trump administration's proposed pick for the next NASA administrator, Jared Isaacman. Our chief of space policy, Casey Dreier, and our director of government relations, Jack Kiraly, will give you the details, then Bruce Betts will join us for What's Up? and a new random space fact.

If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it.

A couple of months ago in October, Dr. Neil deGrasse Tyson and the StarTalk podcast crew joined our team at Planetary Society HQ in Pasadena, California. Neil is the co-host of StarTalk and the director of Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. You may also have seen Neil on TV over the years, especially if you're a fan of our co-founder, Carl Sagan's 1980 series, Cosmos: A Personal Voyage. Neil hosted that show's successors, Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey and Cosmos: Possible Worlds. If you're curious about how that happened, you can learn more about Neil's personal connection with Carl Sagan in the first show.

StarTalk is a podcast where Neil and his comic co-host discuss space, pop culture, and everything in between. There was also a spinoff TV version on National Geographic for a while, and as a bonus treat, the full video version of this conversation is going to be available on StarTalk's website and YouTube channel. Our CEO, Bill Nye, met Neil during Neil's time on The Planetary Society's board of directors. They've gotten into some sciencey shenanigans over the years, but they haven't had the time to reunite in quite a while. We take you now to Bill Nye's office, where Neil and Bill sit among the various science knickknacks, spacecraft models, and images to discuss The Planetary Society's 45-year legacy of advancing space science and exploration.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: We got with me in studio, Bill Nye.

Bill Nye: Greetings, Doctor.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: How you doing, man? Got a bow tie on and everything. You're just completely that guy.

Bill Nye: I am that guy.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: The science guy.

Bill Nye: What you see is what you get.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: And did you tie your own bow tie today?

Bill Nye: Yeah. Can you imagine? Bill Nye wears clip-on tie.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: That would be a funny skit.

Bill Nye: [inaudible 00:02:58]. Bill Nye decided to end his career and lose respect from all his fans.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I want you to know if I ever see anybody with a bow tie, I ask them if it's real, and if they say not, which is about two-thirds of people, I-

Bill Nye: Not. See what he did there?

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I say, "I'm going to tell Bill Nye on you," and then they'd shudder because they...

Bill Nye: They can wear a clip-on bow ties. That's fine. I mean, I just think it's not in, as we say, the spirit of the game.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: We are now in your office of The Planetary Society, Pasadena, California, the same town where this society was birthed.

Bill Nye: A true fact. Not a false fact.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Give me a fast birther story on this.

Bill Nye: Carl Sagan had been very influential in getting the Viking landing on Mars and the two Voyager spacecraft launched.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: And just for historical completeness, there were two missions of Viking lander and a Viking orbiter-

Bill Nye: Yes.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: ... so it could photograph the surface.

Bill Nye: Yes. Really amazing visionary ideas. He noticed that public interest in space exploration, especially planetary exploration, was very high, but government support of it was waning. He had this big idea for a solar sail spacecraft

Neil deGrasse Tyson: It's in 1970s now.

Bill Nye: 1976.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah.

Bill Nye: The disco era. That was set aside for more human missions, including the famous handshake in space so that the Soviet Union and the United States would have no more conflict. That worked out great.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: It was an Apollo capsule in orbit around Earth, a Soyuz capsule, and they were configured so that their collars could join. They opened the hatch and they're all weightless, so they're just floating through, and they would shake hands. I was told that the Americans were trained to only speak Russian and the Russians were trained to only speak English.

Bill Nye: And US astronauts still speak Russian. It's still a thing they do. We flew on Soyuz rockets for a zillion years, all that inclusive. Bruce Murray, who was head of the Jet Propulsion Lab during these famous missions, Viking, Voyager, and-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Jet Propulsion Lab right here in Pasadena.

Bill Nye: Yes. Right at [inaudible 00:05:15] up the street. And then Lou Friedman, who was an orbital mechanics guy-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Engineer.

Bill Nye: Yes. Both a PhD, which you like, they decided that there was enough interest in space exploration that they could start The Planetary Society.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: And of grassroots interest.

Bill Nye: Grassroots.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah.

Bill Nye: The Planetary Society had tens of thousands of members by the end of, pick a number, 1982. It was started in the winter of '79, 1980. I'm a charter member.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Now, I remember getting the letter.

Bill Nye: Anyway, The Planetary Society has been around now that we'll have our 45th anniversary this spring. What we do is promote planetary exploration. Just notably, just last week as we're recording this, the Europa Clipper mission left for the moon of Jupiter with twice as much ocean water as Earth. That is in part... Let's say entirely, because of The Planetary society, our members, 40,000 people around the world think space exploration of planets is very important. Wrote letters and emails to US Congress especially, got this mission funded 11 years ago, and now it's flying.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: And it was delayed because of Hurricane Milton.

Bill Nye: Hurricane Milton.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Has the mission statement changed over the decades?

Bill Nye: Very little but it's succinct now.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Okay.

Bill Nye: We're the world's largest independent space interest organization, advancing space science and exploration so that citizens of Earth will be empowered to know the cosmos and our place within it.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: That's really catchy.

Bill Nye: Well, here's what it is. It's succinct. We empower citizens.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I agree. I'm just saying it doesn't roll off the tongue.

Bill Nye: Well, it does if you're the CEO. Yeah, before the elevator doors close.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: You are CEO and president.

Bill Nye: No, no, no. There's a bylaw rule. I'm not president.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: What are you?

Bill Nye: We have a separate... I'm CEO.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Just CEO.

Bill Nye: Yeah.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I thought you were important.

Bill Nye: Exactly. The president is an unpaid position.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Did not know that.

Bill Nye: Yeah, that's a great tradition here to nonprofit in California.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: You used to be president.

Bill Nye: I used to be vice president.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Vice president, okay.

Bill Nye: Yeah. Oh, I was equally unpaid as vice president. The board of directors is committed and just notice everybody. Our board is the real deal bunch of people. Our president's Bethy Elman. Dr. Elman is a professor at Caltech. She has a couple missions that she's a principal investigator, a PI on. And our vice president, Heidi Hammel, is one of the 20 most influential women astronomers in history. Britney Schmidt is driving around submarines under the ice in Antarctica to prepare to go under the ice on Europa and Enceladus and-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: One of the moons of Saturn.

Bill Nye: Of Saturn.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Another icy moon.

Bill Nye: Icy moon.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah. Yeah.

Bill Nye: Everybody, if you have ocean water for four and a half billion years, is there something alive?

Neil deGrasse Tyson: It happened here on Earth.

Bill Nye: Yeah.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: One of the defining missions of the 1970s was the Voyager.

Bill Nye: Oh, it still defines people. Here's the-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: The Voyager.

Bill Nye: I don't know if it's wide enough to see, but there's a replica of the record.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: This defined a generation of hope for the future of space exploration. Carl Sagan was particularly visible and known over that time.

Bill Nye: Yes.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah. Has it changed over the decades? I asked that, because if I remember correctly... Because I used to serve on the board of The Planetary Society and I cherish those years because it's where I met you.

Bill Nye: Lucky you.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: And it's where I met Ann Druyan, Sagan's widow.

Bill Nye: Yes. Yes.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I did not know either. I might've met her once or something, but we didn't know each other until we were both on the board. These are important connections to be made.

Bill Nye: Yes. This is what we do. We connect people with the passion, beauty, and joy, the PB&J.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: PB&J, loving it. I remembered there was a resistance to people in space relative to robots. Some of that might've just been the sphere of influence of Carl Sagan where he just... He's a robot guy.

Bill Nye: From an engineering or scientific or science fiction critic of astrophysical observer such as-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Which I count myself among the ranks of.

Bill Nye: Yes. Yes. Premier astrophysical observer know it well. You can't get people to Europa. It's too flipping far away and too cold and there's nowhere to walk and everybody's going to die.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: In that order.

Bill Nye: So you build the spacecraft to go there as our proxies. We designed the instruments to give us both a scientific perspective and a human perspective.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: But in the day, robots were nothing compared to today. In the day, I mean 50 years ago.

Bill Nye: 50 years ago.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Comparing robots then to today, [inaudible 00:10:14].

Bill Nye: Yes, that's what I'm saying.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: What do you got here?

Bill Nye: This is the Spirit rover. A picture of the Spirit Rover and the cameras-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: And its solar panels.

Bill Nye: Yes, the cameras were set up to be, this is the expression, as high as a 10-year-old's eye. These cameras were put there so that humankind could imagine ourselves walking around, driving around on Mars, and talking about the planetary side. The lore that we promote, and I think you alluded to this earlier, is that Bruce Murray was a young guy in the 1960s, co-founder working on the Mariner program.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Mariner to Mars.

Bill Nye: Mars, which was the Ranger spacecraft repurposed to go...

Neil deGrasse Tyson: The Ranger went to the Moon to map the Moon for Apollo.

Bill Nye: And as a kid, I would be in class, and we watched the moon come up. Yeah. Kept in space, no sound.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah. Some of the Ranger's crash-landed.

Bill Nye: Yeah. On purpose. Purposefully to see what the lunar surface was like up close.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I forgot all about Mariner, because Mariner, I think, took the first pictures of Mars that revealed there were no canals at some [inaudible 00:11:23].

Bill Nye: Yeah. This Bruce Murray gets credit when you're talking to us at The Planetary Society for being the guy who insisted that spacecraft have cameras.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Because people think scientists love pictures, but-

Bill Nye: Well, it depends on the picture.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: No, what I mean is there's much less science in a photo than the public is led to believe. We get chart recorders, we get magnetometer-

Bill Nye: Geiger counters, magnetometers.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Geiger counter, magnetometers...

Bill Nye: A spectra. We got a lot of optical.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: We got a spectra. Give me spectra over a photo any day. But if people get doe-eyed about how beautiful the universe is...

Bill Nye: Well, it'd change the world.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: It'd change the world.

Bill Nye: Pictures from space change the world.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: They can change the world. Right. We all, at some point, must confess to ourselves that that is the fact.

Bill Nye: Go and confess your brains up.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: If we want to credit back to some of these founding fathers, I think Carl Sagan was the first scientist in his writings and in his appearances on television to put you, just a regular person-

Bill Nye: A regular person, citizen of Earth.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: You became a participant on that frontier. It was no longer, "Let them go do their thing and they'll report back later." No.

Bill Nye: Or spend some tax dollars on this. It probably doesn't have anything to do with you. That's not his-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Right. Right. Right. It all has something to do with you.

Bill Nye: Everything. You are part of this great process of discovery, this adventure. Bruce Murray used to talk about the unknown horizon. Why are you guys sending spacecraft out to these extraordinary distant places? What are you going to find? We don't know what we're going to find. That's why we're sending the spacecraft.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I think it's Einstein that's famously said, "Research is what I'm doing when I don't know what I'm doing."

Bill Nye: That sounds good.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah. Yeah. That's completely the case.

Bill Nye: And Isaac Asimov, "Science doesn't begin with a hypothesis. It begins with, 'Oh, that's funny.'"

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Oh, no, you got that wrong.

Bill Nye: Oh, help me out.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah. He said very few scientific discoveries, if any, ever begin with Eureka. That's funny.

Bill Nye: That's funny. What is that?

Neil deGrasse Tyson: We explore the planets. Another thing I credit The Planetary society for and its philosophies and its outlook is turning objects in space into worlds.

Bill Nye: Worlds is a great word.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: When you use the word world, it's no longer a detached object from your imagination. It really gets you here.

Bill Nye: You got it, man. You hit the... No, Neil, that's absolutely right.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I don't know anyone else who... Any other-

Bill Nye: Organization.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Organization or worldview that made that such an important point.

Bill Nye: Right on, man.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Another thing that I credit the enthusiasm of The Planetary society for is when I was growing up, the moons of planets like, "Why wouldn't anyone give a rat's (beep)? It's the moon. Look at the planet, not the moons." And then Voyager goes out there, gets pictures of the moons, and the moons are more interesting than the planets.

Bill Nye: A lot going on.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: A lot. They're all different.

Bill Nye: Io, Europa, Ganymede.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Our moon is like the least interesting in the solar system. Planets become more interesting, moons become places to go and revisit, but there was a whole other goal, and that was a search for intelligent life-

Bill Nye: It still is.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: ... in the universe.

Bill Nye: Oh, man.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I'm remembering how big a part of that was in my couple of years when I served on the board, but then when I came off the board, it's less tangible, right? Because we don't know if the aliens are out there. And are they hearing, are they listening to us? Where is TPS, The Planetary Society, relative to the search for intelligence?

Bill Nye: Well, we've let that go to this SETI Institute.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: SETI Institute, of course.

Bill Nye: Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence Institute.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: And they're based up in Northern California.

Bill Nye: Yeah. Yeah.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Right.

Bill Nye: And then they're very well-endowed and they chip away at this problem.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: They just got a boatload of money just recently.

Bill Nye: Well, I went with well-endowed, you can go boatload of money. Spacecraft full of money.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah.

Bill Nye: They will carry on that research in their enabled best way possible.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: They have a whole suite of telescopes originally funded by Paul Allen with the Allen Array.

Bill Nye: Paul Allen. Allen Array, yeah.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: So these are telescopes that are sensitive to radio waves on the assumption that, if anyone's going to talk to us, they're going to use radio waves because radio waves penetrate clouds.

Bill Nye: Carl Sagan was very well-spoken about this logical place where water molecules would not absorb radio wa-... Logical place, logical frequency, or radio waves would not be absorbed by water vapor. And so if an alien civilization were-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Because water vapor is across the universe as well.

Bill Nye: Yes, hydrogen's everywhere.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah.

Bill Nye: You could aim your intergalactic or interplanetary, interstellar message to go through the water hole as he called it. Very cool term. But all that aside, it's very reasonable that maybe in my lifetime, but in your kid's lifetime, somebody's going to find evidence of life on another world. The logical places are going to be under the sands of Mars.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Okay, but this would be microbial life. This is not-

Bill Nye: Well, yeah, but still it would change the world.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: [inaudible 00:16:49].

Bill Nye: Then you would say to Mr. Microbe, Ms. Microbe, they Microbe, "Do you have DNA? Are you a whole another different-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I get that but that wasn't what SETI was about.

Bill Nye: No, no, it's still not.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Right. SETI finding microbes, that's not their-

Bill Nye: That's fine. Knock yourselves out.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: That's not their thing.

Bill Nye: Because if we found such a signal, it would, dare I say it, change the world.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Change the world.

Bill Nye: SETI Institute keeps listening.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: We had an exhibit at the Hayden Planetarium before we rebuilt that was narrated by William Shatner. It was about the search for life. And I remembered the quote because I thought it was a brilliant sentence. He said it in his pause, acting way, "On the day we discover life will signal a change in the human condition that we cannot foresee or imagine."

Bill Nye: Du, du, du, du, du, du, du. That's pretty good. No, I say all the time, everybody will feel differently about being a living thing.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yes. Whether or not it's what we call intelligent. Oh, yeah, it would transform biology.

Bill Nye: The logical question from the sands of Mars... There's another hypothesis that once life starts, you can't stop it. So if life started on Mars-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Life finds a way.

Bill Nye: Yes, there's salty slush near the equator of Mars kept almost warm by the sun. Are there microbes living under the sand? And if we found them, do they have DNA to wit? Was Mars hit with an impactor, which happens all the time-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Long ago.

Bill Nye: ... knocked a living thing on a rock off into space, it fell, except in space, no sound.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: These would be microbes stowing away in the nooks and crannies. Yeah.

Bill Nye: Stowing away, trapped, stowing away, land on Earth, and you and I are descendants of Martians. That is an extraordinary hypothesis.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I think you more so than me because [inaudible 00:18:39]

Bill Nye: Yeah. Well... It's an extraordinary hypothesis, but if it proved to be true, it would change the world. It is worth...

Neil deGrasse Tyson: That would be panspermia, I think was the word. Yeah.

Bill Nye: Panspermia, it's worth investigating.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Right there.

Bill Nye: In the Viking missions, famously the rocks came back... Those pictures depicted the Martian sky as blue and the rocks were too pink. I was at the 30th anniversary of this thing and these guys were talking about... It took them about a day and a half to realize that the cameras had been calibrated on Earth and the pictures needed to be re-calibrated. They found intuitively that if you look at the shadow, you can infer the color of the sky. Those of you out there who haven't sat through this, go outside on a sunny day. If you're in Ithaca, New York, where I went to college-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: There's no sun.

Bill Nye: There is a sunny day scheduled in the next 10 years, then you make a shadow in something white, like my shirt would be good, and you'll see the shadow is gray to be sure, but it's also ever so slightly light blue. That's because the sun is not the only source of light here on Earth's surface.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Blue sky. [inaudible 00:19:54].

Bill Nye: The sky is the source of light. Looking at me, nothing but orange skies on the other planet.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Blue sky. Blue sky.

Bill Nye: Yeah. On Mars, the sky is orange or salmon colored or what have you. They found that by looking at the shadow, they could infer the color of the sky and then how much the colors of the rocks had been influenced on the camera, on the images by the color of the sky.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: That's very clever. What you're saying is, to summarize, whatever's going on in the shadow is not directly influenced by the sun.

Bill Nye: It's directly influenced, but it's not the only influence.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: No, no, no. Sorry. You get an authentic background lighting from the rest of the sky.

Bill Nye: Yeah.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah.

Bill Nye: The idea was to send this post, a stick, to Mars to cast a shadow. I was in the meeting and I said, "Aren't there many, many things to cast a shadow?" "No. We need it to fall on something precisely calibrated or well-known colors or gray scale." I was in the meeting. Now, my dad had the misfortune of being a prisoner of war in World War II for almost four years and he told the story often of walking-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Is this in Japan?

Bill Nye: In China at first and then Japan at the end of the war. As Japanese influence shrunk, they got moved to the south island of Japan for the last year of the war. But he would, by all accounts, stick a shovel handle in the soil and watch the shadow and reckon when it was lunchtime kind of thing. He came back-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: The very sundial of him.

Bill Nye: That's right. He wrote a book about sundials. He was the astronomy merit badge counselor. He made a sundial-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: That would be for the Boy Scouts.

Bill Nye: For the Boy Scouts.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yes.

Bill Nye: I was in the meeting. They're going to send a metal stick to Mars to cast a shadow.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: So you have genetic [inaudible 00:21:42].

Bill Nye: I'm just jumping out of my chair. "You guys, we got to make that into a sundial."

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Okay. I'm glad you didn't put a shovel here for this.

Bill Nye: They were all looking at me like, "Dude, it's the space program. Bill, I see you're wearing a watch." "No, come on." It'll be like people who speak Klingon, except it'll be real.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Mars, 2004. Two worlds, one sun.

Bill Nye: Yeah. Lou Friedman, one of our founders, came up with that. We were having dinner. He said, "One sun, two worlds." And in a few seconds we all went, "Oh, no, no. Two worlds, one sun." That's really inspirational. Light shadows on Mars are cast by the same life-giving star as shadows on Earth. Now, wait, wait, there's more. On the edge around the dial is a message to the future. We built this instrument in 2003. It arrived here in 2004 to study the Martian environment to look for what? Signs of water and life. On the last of the four panels-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I can't read this. What is it? Is it in Braille? What is it?

Bill Nye: It's in a younger person's font. Yeah.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Okay. That's what it is.

Bill Nye: On the last of the four, it says, "To those who visit here, we wish a safe journey and the joy of discovery."

Neil deGrasse Tyson: And that's written in English, because of course aliens read English.

Bill Nye: Well, English would... No, no, It's written for humans.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Oh, other humans who arrive.

Bill Nye: Yeah. English is the language of aerospace even now.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: And of aviation, too.

Bill Nye: Yeah, aviation. Yeah. It's optimistic. People are going to be there and they're going to go up to that thing and look at it and think about the people-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: The way we go up to the Plymouth Rock up in Massachusetts.

Bill Nye: The way we go up to what have you, yes.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Right.

Bill Nye: A pyramid, a Machu Picchu, we go up and go, "Wow, that's an extraordinary thing humans before us did." It's optimistic and it has the joy of discovery. That has become PB&J, passion, beauty, and joy. JOD, joy of discovery.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Tell me about political advocacy, because it's one thing to just celebrate it, but at some point somebody's got to show up in Washington.

Bill Nye: This is what we do. We-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Have you been asked to testify?

Bill Nye: Oh, heck yes. What we have been able to do is hire two guys who are just really into this and are excellent at it. We have one guy who studies policies-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Wait. Wait. This sounds like you're talking about lobbyists.

Bill Nye: No. A lobbyist is a paid person and he has to have a license and this and that. We are advocates. What we do is get our members. We send letters and emails to members of Congress and the Senate advocating for space missions that we believe are in the best interest of humankind and the best interest of making discoveries on these other worlds that will affect our world. The one that we're all talking about this week is the Europa Clipper, a replica shown here.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Right. Because it launched, right?

Bill Nye: I testified in front of Congress in 2013 about the importance of this mission, where we're looking for signs of life on another world and/or organic material on another world to learn more about our own world. We do it for inspirational, wonderful joy of discoveries reasons, but it's also... If you want to be the world leader in technology, you invest in space exploration.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I testified once, but I wasn't representing a whole organization as you are.

Bill Nye: Well, that's what I say.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: That's a different force operating.

Bill Nye: Plus, I'm one voice and my voice is not irrelevant. To be sure, it's relevant, but when these congressmen and senators get thousands, tens of thousands of 10Ks of letters and emails, it affects them.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll be back after the short break.

Bill Nye: Greetings, Bill Nye here. 2024 was another great year for The Planetary Society. Thanks to support from people like you. This year, we celebrated the natural wonders of space with our Eclipse-O-Rama event in the Texas Hill Country. Hundreds of us, members from around the world, gathered to witness totality. We also held a search for life symposium at our headquarters here in Pasadena and had experts come together to share their research and ideas about life in the universe.

Finally, after more than 10 years of advocacy efforts, the Europa Clipper mission is launched and on its way to the Jupiter system. With your continued support, we can keep our work going strong into 2025. When you make a gift today, it will be matched up to $100,000 thanks to a special matching challenge from a very generous Planetary Society member. Your contribution, especially when doubled, is critical to expanding our mission. Now is the time to make a difference before years end at planetary.org/planetaryfund. As a supporter of The Planetary Society, you make space exploration a reality. Thank you.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: With the helm of this ship that has influence. When I testified, I'm just Neil talking to the Congress and I've... "What am I doing here? What do they want?"

Bill Nye: That's what everybody said to me, Neil, behind your back. No. So-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I look at this list here, because it's not just Europa Clipper, which is successfully-

Bill Nye: No, that's the most recent one.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Oh, it's just most recent. Hubble, Mars Sample Return, the new Horizons to Pluto, the Europa Clipper, of course. I got two other missions here, VERITAS, which means truth but that's all I know about it, and Viper. What are those?

Bill Nye: VERITAS is a mission to Venus. Haven't had a mission to Venus in four years.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: It's not entirely hospitable.

Bill Nye: Oh, well, but you want to have a look and see what happened on Venus.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Have a look, see.

Bill Nye: Yeah. What happened on Venus, we don't want to happen on Earth. In fact, people talk about climate change now regularly. As you know, I've been whining about it for-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: You got a whole book.

Bill Nye: On climate, yes.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: What's the name of that book?

Bill Nye: Undeniable.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Undeniable, yes. A whole book talking about the reality of climate change and how to spread that information against misinformation.

Bill Nye: Misinformation largely from the fossil fuel industry who's worked hard to make scientific uncertainty the same as doubt about the whole thing.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah.

Bill Nye: But that aside, you can argue that climate change on Earth was discovered by studying the atmosphere of Venus in 1984 or so. This is really an extraordinary thing. It's this classic Bruce Murray. "What are you going to find when you go exploring these other worlds?" "We don't know. That's why we go exploring."

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Bill, what you just said reminds me of that quote from T. S. Eliot, where he says... I'm going to mangle it, but the essence of it will be there. "You explore the world, see new places-

Bill Nye: Travel.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: ... travel and then you come back home, and only then will you know that place for the very first time."

Bill Nye: As I say, the more we explore these other worlds, the more we know about our own.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: That's that. Is it a new field, comparative planetology?

Bill Nye: Carl Sagan used to toss that phrase around like it was a real phrase.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: It's not like we're here and everything else is something else. Another big part of The Planetary Society's identity was the successful appeal funding and launch and deployment of the solar sail, which was the dream of so many people. One of your founders, Lou Friedman, wrote a book.

Bill Nye: Yes.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: This was a very big... Ann Druyan was a big proponent of this.

Bill Nye: Oh, yes.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Ann Druyan, Carl Sagan's widow and board member. Would you count that as among the bigger achievements?

Bill Nye: Oh, yeah, especially under my watch. No, really, we had a solar sail launch funded largely by Ann Druyan and some people associated with the Discovery Channel. It crashed in the ocean and it was okay, game over, done, boom. So then it took many years, nine more years, to get it together, to build another spacecraft. In that interim, this thing called the CubeSat emerged, cubicle satellite, which are 10 centimeters by 10 centimeters by 10 centimeters. And then variations of that have been... You can go online and buy parts for a satellite.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: And they're cheap to launch.

Bill Nye: Very inexpensive.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: It's like your science project.

Bill Nye: Yeah, it is. A lot of students, a lot of universities and high schools participate in CubeSat programs. The other thing is electronics have gotten increasingly smaller, more miniaturized.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: One can argue that the miniaturization of electronics was stimulated by space.

Bill Nye: Yes. Well, it's, how to say, symbiotic.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah.

Bill Nye: We were able to get funding. 50,000 people around the world just think it's great. We launched spacecraft in 2014 to prove that it would work. By the way, I've done very little as CEO. The place is run by Jennifer Vaughn, our chief operating officer. We have a chief financial officer, Jim Suh. We have chief of communications, Danielle Gunn. We got a development officer, Rich Chute. We got all these people, but once in a while, somebody's got to decide to do something, so it was my decision. Should we take this launch in 2014 with a spacecraft that wasn't as capable as we hoped one day would be but had cameras? We launched in 2014, we got these pictures down, and that enabled us to get funding to launch LightSail 2.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: There it is. You could see the LightSail 2 unfurling. Am I remembering this? It's very real.

Bill Nye: Yes. And so by the way, right there is a boom. That golden looking thing is beryllium copper. What's cool about it or remarkable... This is the same material in much shorter length. Just notice how stiff it is if you try to bend it and notice how compact it is if you try to roll it or bend it in the other axis.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Okay.

Bill Nye: This is what enables-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: You fold it up to get into the fairing.

Bill Nye: Well rolled up.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah.

Bill Nye: Yeah. And if you look at it, there's these tiny dots. These are laser stitch-welded at the US Air Force Research Lab. Anyway, I mentioned all this because there's a lot of cool technology that we perfected and flew in 2017.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: As any good space mission does.

Bill Nye: Yes.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Because you're doing something that's never been done before.

Bill Nye: Never been done.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Somebody's got to innovate.

Bill Nye: Yep. Had to innovate the control laws, how you steer it, and the rolling it up and getting it robust enough to tolerate cosmic rays without being too heavy to fly. We did all that and so very proud of that. People ask us, "What's next?" I'll just say stay tuned.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I want to remind people, unless they've been living under a rock, many people, you taught them science growing up as Bill Nye the Science Guy.

Bill Nye: It's amazing. It really is amazing.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: And now they're full-grown adults with kids and some of them have kids and you're like Papa Science here.

Bill Nye: Yeah.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: You were the heir apparent to what maybe was in our generation... Who's the guy on TV? Mr-

Bill Nye: Oh, Don Herbert.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah, Mr. Wizard.

Bill Nye: I had lunch with him.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: You did?

Bill Nye: I looked like nobody. I had lunch with him.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Don Herbert and he was Mr... What was he?

Bill Nye: Mr. Wizard.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Mr. Wizard, yeah.

Bill Nye: "Are you fooling with me, Mr. Wizard?" I went to his memorial service and, you guys, I was just crying. I just couldn't get over it, man. The guy was so influential. I can tell you with the technical aspects of everything, but his show was done intuitively. The Science Guy show, we had all this research. That 10 years old is as old as you can be to get the so-called lifelong passion for science.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Oh, yeah, to get it in you.

Bill Nye: So it was dialed in.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I was nine. I was nine.

Bill Nye: I love you, man.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah.

Bill Nye: It was dialed in for people 10 years old. That's part of why the show was so successful.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: And then you would... I don't want to say transition out of that, but you added to your-

Bill Nye: Let's go with that.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: ... professional profile.

Bill Nye: Added, yes.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yes. To be a space advocate for adults and for the nation and for the president-

Bill Nye: For the world.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: ... this sort of thing. Yeah. And did you ride in Air Force One one time?

Bill Nye: Yeah.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: [inaudible 00:34:18] excuse me.

Bill Nye: Barack Obama got to meet me and spent some time.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Did you chill in with Barack?

Bill Nye: Oh, well, yeah.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: There you go.

Bill Nye: But he is a very thoughtful and frankly charming guy-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: And smart, yeah.

Bill Nye: Well, he's brilliant. We talked about space exploration on Marine One.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: The helicopter.

Bill Nye: I know you've hung out with him, but it was-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Not on his airplanes, though.

Bill Nye: ... quite cool and he was very receptive to addressing climate change. He was very interested in that. His policies led to this, the beginning of the start of a beginning of climate policies involved in the Inflation Reduction Act, AKA the clean power approach.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Right. Which had some elements to it. Yeah.

Bill Nye: Yeah.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Yeah. Yeah. So, Bill.

Bill Nye: Neil.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Planetary Society.

Bill Nye: Great to see you.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Where do we find it? You got a website for it?

Bill Nye: planetary.org. It's your homepage.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Planteray.org.

Bill Nye: Planteray.org.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Okay.

Bill Nye: And we have a podcast.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Is there something, a button there that you can join?

Bill Nye: Yes. On every page, if you guys want to run a nonprofit, you put a donate button on every page.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Right, that's what it is.

Bill Nye: We thank everybody out there who is a member, encourage those of you who, for some reason, are not members to join us. We have now The Planetary Academy aimed at families.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: And the monthly Planetary Report.

Bill Nye: Planetary... We have four times a year now, because people get their space information on the electric internet. We have longer form articles in the printed magazine-

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Rather than journalistic articles, which wouldn't make any sense.

Bill Nye: Which we have some of each. I claim we have the world's premier long form planetary science journalism.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Nice. But I myself have referenced it to catch up on certain elements of certain missions.

Bill Nye: Yes, thank you. Yes, we have the best reporters going.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Because mission information is very fragmented.

Bill Nye: It is everywhere.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: There's a little bit there and a little bit there and it comes into a coherent, sensible pedagogical delivery.

Bill Nye: Thank you, all. planetary.org, turn it up loud.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: This has been my exclusive conversation with the one and only Bill Nye the Science Guy.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I had so much fun helping to produce that episode of StarTalk. I'll leave a link to the full conversation and the video version on the web page for this episode of Planetary Radio. You can find that at planetary.org/radio. But before we let you go, we've got a huge space news announcement.

On December 4th, US President-elect Donald Trump announced his proposed choice for the next NASA administrator, Jared Isaacman. The nomination won't be official until Trump takes office in January, but Jared has publicly accepted the nomination in a post on X, formerly known as Twitter.

Jared Isaacman is the billionaire founder and CEO of Shift4, a payments processing company that he started at age 16. He's also a huge space fan as evidenced by his ongoing series of self-funded SpaceX Dragon flights. The first was called Inspiration4 and happened in 2021. It was the first all civilian crewed orbital spaceflight. Their adventure was documented in the Netflix series called Countdown: Inspiration4 Mission to Space.

The subsequent Polaris Dawn mission launched just earlier this year in September 2024. It carried its crew farther from Earth than any humans had been since Apollo 17. That was 52 years ago. Polaris Dawn also marked the first private spacewalk. Jared Isaacman flew on both of those missions.

Before we get into this conversation, I want to note that The Planetary Society is a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization. We don't endorse candidates, but we are committed to working with NASA leaders to help shape our collective space goals. I'm now joined by Casey Dreier, our chief of space policy, and Jack Kiraly, our director of government relations. Hey, Jack and Casey, thanks for joining me again.

Jack Kiraly: Good to see you.

Casey Dreier: Hey, Sarah, it's great to be here.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I've got Jack here in the office and Casey up in Washington and we all just got word that the next NASA administrator has just been selected. Who wants to break the news? Who is it?

Casey Dreier: I guess I'll do it. Why not? Jared Isaacman, who... I mean, by the time everyone's listening to this probably knows, but Jared Isaacman is a billionaire-owner of a payments processing company, but, for us, notable for purchasing a number of private space flights through SpaceX and has orbited in space twice. With the last one, Polaris Dawn, taking him further from the Earth than any astronaut had been since Apollo 17. It's an outside the box pick in a way, but obviously a big fan of space and someone who... It's interesting. It's a first person who's been to space who might lead NASA who is not an astronaut.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. I was really into their first mission, the Inspiration4 crew, the first all-civilian mission that went to space. I'm not personally surprised that Jared Isaacman is the choice here, but at the same time a little bit of a departure from the classic NASA administrators. How are you feeling about it, Jack?

Jack Kiraly: I'm feeling pretty good about it. In previous administrations, including the outgoing administration now, we've had folks who have been a part of the agency either for a long time or who have overseen the agency in political roles, whether in the House or Senate. In the case of Jim Bridenstine, in the first Trump administration from the House side, and then Senator Bill Nelson on the Senate side. It's kind of a... Maybe we'll say breath of fresh air, right? It's new person in the room who has a vested interest in the success of the agency, but who has done things, extraordinary things in a private capacity as well and starts to build that bridge between the commercial side of space and the civil side of space. I think it's bringing a lot of fresh new ideas and has a lot of, I think, goodwill from the public as well as policymakers,

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But we don't have any idea of how he's going to fit into this political role. Now that we know this is the choice... I know it's fresh on both of your minds because we just found out, but does this tell us anything about where we think NASA funding and funding for programs like Mars Sample Return or Artemis might be going?

Casey Dreier: I think it's important to really reinforce that the NASA administrator has influence and they obviously run the agency, but they execute what Congress allows them to do ultimately. Congress provides the funding and can change the law and compel NASA to do various things or not. He has to go and actually build coalitions. I think that may be the biggest unknown here. It's very different. We talk about folks who want to come in and run government like a business. I think, in the best case scenario, what they mean by that is can we make things more efficient, make people accountable, and have the ability to really be answerable and dynamic?

Public agencies, just for a number of reasons, they're just fundamentally different creatures than a private business. It's all about coalition building. I can see, if you are coming from the private sector, the difficult thing of trying to go to a senator's office and cajole, beg, ask, whatever you can do to get your priorities funded. You have to put in that legwork.

Bridenstine was very good at that and he put in a lot of effort doing that. It takes a lot of patience and you have to know how politics work. I'm not saying Jared can't do that. It's just a very different skill set and this is always why when businessmen do come into government, they tend not to run it like a business because you can't without fundamentally changing the law.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: When we learned about who was going to be the upcoming president, we speculated a lot about what this was going to mean for the difference for funding for human spaceflight versus the science mission directorate and all of the space missions to other worlds that we love. Do we have any clue what Isaacman might feel about these? I mean, clearly he isn't the one that controls the budget, but at the same time he's going to be shaping some of these priorities.

Jack Kiraly: Well, I think that, for Isaacman, there was a period of time in the last couple years in which he was advocating for a private mission to boost the Hubble Space Telescope to a higher orbit. And so I think has a lot of reverence and respect for the work that NASA has done in the past to expand our understanding of the universe and to provide these platforms that scientists around the world have used to do just that. I think that there is a lot of opportunities here for out-of-the-box thinking for missions like Mars Sample Return, for future missions like Habitable Worlds Observatory, these really big flagship and even smaller New Frontiers and Discovery class within planetary science missions that will be the Hubbles of 20 years from now, potentially.

I think that there is a lot of hope here. We don't know a lot about how he feels about maybe specific program lines in the current NASA budget, but he has that, I think, sense of awe that we all feel when we see a new image from the James Webb Space Telescope or see a new picture from the surface of Mars. I think it's great to have someone who shares that reverence for those things that we do in space and who has taken it upon himself to be an advocate for those missions and for expanding capabilities of the commercial sector.

Casey Dreier: At the same time, I think it is clear he's a commercial space guy. I mean, let's not beat around that aspect of it. He released a statement after. It's always funny to say. Trump didn't technically nominate him because Trump isn't president yet and he's not actually nominated. It's his intent to nominate him. Regardless, after the news came out, he did release a statement on Twitter and he called out the things that he seems personally excited about in space. I'll name a few: manufacturing, biotechnology, mining, perhaps new sources of energy, thriving space economy.

This is a commercial space guy and he's friends with Elon Musk, so he shares a personal and has worked really closely with SpaceX over the past years to do his private space flights. That will be his incoming position is that SpaceX is the ideal, I would hazard to guess, and he sees space much more through this economic development, human progress. For those of you who've listened to my episode with Roger Launius on human spaceflight as a religion, he's kind of that technocratic salvation theology of getting people out into space as a means to improve the human race.

I share a lot of those feelings and I would like to see him mention science, but he notably didn't in his public statements. This'll be one of the things, as Jack said, we'll look forward to hearing more about and also do a lot of outreach to talk about. He says, "Americans will walk on the Moon and Mars, and in doing so we'll make life better here on Earth." Notable call out to humans to Mars, too. I think that's an important statement.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I am curious what this might mean for the SLS rocket given his history with SpaceX, but it's hard to speculate at this point.

Casey Dreier: He said on Twitter, "A program like the SLS," and I'm quoting here, "outrageously expensive, tolerable because, hey, everyone wins." He says, "As a result, our children don't get to see many moon landings and the dream of an enduring lunar presence fades away." He's not a fan. What's interesting is given his... As Jack said, he's not a political person. He wasn't a politician. I think, in a lot of ways, he will be more palatable to the Senate Democrats and that may be enough to overcome any sort of SLS adjacent coalition of Republican senators where most of the SLS money is spent in ensuring his nomination. That'll be the really interesting dynamic to see.

Jack Kiraly: Yeah. I mean, I think this just demonstrates a opportunity that space advocates like listening to this episode can have in the coming years. We have an opportunity with the incoming administration to shape some of these areas where all we can do is speculate. We have statements like Casey just had statements on SLS and on these sort of larger visions, but there's so much that NASA works on that isn't enumerated in these statements that we have currently.

I think this offers a great opportunity to work with the incoming administration, incoming Congress, because they're also a big part of this. They hold the purse strings, set a lot of these big policies in authorizing legislation to build that future that we want of expanding human activity, both robotic and crude, beyond Earth to expand human knowledge and embrace this moment that we have to have a strong space program, both leveraging that commercial side, but also having a strong civil space agency, which is pushing the boundaries of human knowledge as it has the last 60-plus years.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: You both have been in a really interesting situation for the last few weeks, trying figure out who to connect with as this new incoming administration takes power in January. And now we know who the next NASA administrator is going to be. What are the next steps in trying to shape the narrative going forward? How are we going to be connecting with him and all the people that he's going to be working with in order to try to make sure that our priorities in space that include exploring other worlds are actually met?

Jack Kiraly: Well, at this point, it's a lot of coffee conversations, right? It's meeting with folks on the Hill and in these incoming offices. A lot of email conversation at this point. I think hitting the ground running in January is going to be important. I mean, I will say just my own stance here is I was not expecting a pick for NASA administrator this early in the transition. If I remember correctly last time, it didn't take place before January 20th in the previous Trump administration. Really exciting to see that someone has been named and gives us a lot of runway leading up to what is likely going to be the first big budget fight of 2025, assuming that the continuing resolution does get extended into March as has been reported from D.C.

These first few months are going to be critical. There's going to be a lot of opportunities to engage the incoming Congress on funding priorities and other pieces of legislation. The administration, just by virtue of it being a new administration, has going to have a lot of energy in its first 100 days to get things done and a Congress that seems also willing to work with them on some of these big issues, including the federal budget.

It's going to take a lot of legwork and great that we have our day of action planned for within those first 100 days of the new Congress and new administration. March 24th, 2025 is going to be a great day to be advocating for that future of space exploration that we want.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Registration for our Day of Action is open. I just want to mention, if you register early, you do get a discount on coming with us to Washington D.C. to do this kind of advocacy work. But rest assured whether or not you can join us in Washington D.C., there'll still be many opportunities for you to advocate and participate in this. I am tentatively optimistic. This wasn't a pick that I anticipated, but it's not one that gives me a bunch of trepidation either.

Casey Dreier: Honestly, space does bring out the best in us. We should just clarify, The Planetary Society doesn't endorse nominations and we'll pledge to work with whoever is confirmed. But I think having somebody at the end of the day who clearly loves space and is personally familiar with the risks of sending humans into space, who wants space exploration to be something that we do here at the Society, which is to inspire people, to motivate people, to have these shared values of curiosity and tenacity, that is not a bad thing.

I mean, that's a lot of reasons to be optimistic, right? I think there's questions obviously to understand and notably also business conflicts of interest and conflicts of interest with SpaceX. I mean, these are all things that we look forward to hearing about and should be discussed. That's why we have a Senate confirmation process to work through a lot of these and to put those in order. But yes, at the end of the day, someone who loves space running NASA is a good place to be.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, I'm just envisioning that image of him sticking his head out of the little pod in space, looking down at the Earth, hung up on his wall in his new NASA administrator office.

Jack Kiraly: Little did we know that, at that time, we were watching the potentially next NASA administrator take his first private steps into space. Again, setting new boundaries, breaking barriers seems to be his MO, so let's wish him the best in this process and look forward to whoever the next NASA administrator is and the other key personnel that'll be selected as part of the incoming administration. Really looking forward to working with them on achieving these big dreams.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks for the update, Jack and Casey, and good luck in the coming year. This is going to be an interesting time.

Jack Kiraly: Thank you, Sarah.

Casey Dreier: You'll be hearing from us for sure.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll keep you updated in the new year as the Trump administration's plans for NASA take shape. Casey also wrote a new article on the subject, it's called Who is Jared Isaacman, Trump's proposed NASA administrator, and what would he do with NASA? It's available on The Planetary Society's website, but I'll also link it to this episode of Planetary Radio. But in the meantime, we'll check in with Dr. Bruce Betts, our chief scientist for What's Up? Hey, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hey, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: There's a lot crammed into the show this week, because as we were preparing, we got the news that we have potentially the next NASA administrator selected, and that's Jared Isaacman who we talked about earlier on in this show. One of the things that Jared did more recently was he went up with a crew on the Polaris Dawn mission. They took a group of people further away from Earth than anyone has been since the Apollo program. As part of this, they passed into a lower portion of one of the Van Allen belts. So I wanted to ask you, what are the Van Allen belts and how do they impact space travelers?

Bruce Betts: They are particle radiation trapped in the Earth's magnetosphere and zipping around and [inaudible 00:52:45] to do Taurus donuts, a couple of donuts, and sometimes more. But there's one lower donut, which Polaris Dawn would've just dipped into the lower variable part of it. Over 1,000 kilometers altitude, but it really gets going up higher, 3,000 up, several thousand more kilometers. Then there's usually a gap and then you go out to... They move around, which is why it's hard to nail them down. But 15, 20,000 kilometers all the way out, sometimes to 60,000, but it's more concentrated in certain areas. But they were formed by particles, mostly electrons and protons, getting trapped in the Earth's magnetosphere. The upper belt comes primarily from solar wind, basically solar radiation, where it comes in. And electrons preferentially get trapped and scurry around until eventually they had enough atmosphere to chill out.

And then the lower belt is primarily from interactions of cosmic rays, high energy particles coming from beyond the solar system with the Earth's atmosphere. That tends to throw off protons and they get trapped down below. There's a higher concentration of these fast moving subatomic particles that come under the term particle radiation, which, if they hit you, will over time cause damage. But it's one of those, how much do you absorb and going through them and not staying in them? You're fine. I mean, it's a relatively low dose.

Also, we know they're there, so they design the orbit as much as possible to avoid the highest energy parts. They have radiation shielding, so it's not like the ones going through the denser parts, they didn't already around without shielding and such. So they're good. They were discovered by a dude named Van Allen, a famous physicists, scientists of the early particle radiation [inaudible 00:54:54] and, interestingly, discovered in the first ever American satellite, Explorer 1. Carried a Geiger counter and they'd have a very elliptical orbit and they discovered these things.

Even very recently, we discovered a temporary belt in between the other two belts. There's not only variability in those, but there's variability in that. It's because there's variability in the Sun and the Sun's activity and where we are. Van Allen belts.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'm really looking forward to seeing the data they get from the dummy that they put on the Artemis I mission, because they were trying to test more about this radiation, but also how radiation from the Van Allen belts and from space in general impacts women's bodies since we want to send people to space and people of all different walks of life. I've actually connected with the Artemis team to get someone onto the show to talk about that now that we know a little bit more. That'll be interesting. But in the meantime, I think it's time for our random space.

Bruce Betts: Random space fact.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: One of these days, we're going to do one that's cat-themed. Just wait for it.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, we'll see. The Van Allen radiation belts before Polaris Dawn and still in terms of all people who have gone all the way through the Van Allen belts from one side to the other, there are 24. There are 27 slots on nine Apollo missions that went to the area of the Moon and then three astronauts who went twice, Gene Cernan, Gene Cernan, and Jim Lovell.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That'd be so cool. Not that I want to be irradiated by space, but the only thing I'd be willing to put up at that level of radiation for is going to the Moon. Man, that'd be so cool.

Bruce Betts: All right. Everybody, go out there, look in the night sky, and think about dog food. Thank you and good night.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with one of the people recreating Mars' araneiforms, colloquially known as Mars Spiders in the lab at JPL.

If you love the show, you can get Planetary Radio t-shirts at planetary.org/shop, along with lots of other cool spacey merchandise. Help others discover the passion, beauty, and joy of space science and exploration by leaving a review and a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. And see, after listening to this interview, you now know that the PB&J came from our CEO. You can also send us your space thoughts, questions, and poetry at our email at [email protected]. Or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the Planetary Radio space in our member community app.

Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California and is made possible by our wonderful members. You can join us and help shape the next 45 years of space exploration at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Ray Pauletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. And until next week, ad astra and keep looking up.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth