Planetary Radio • Apr 10, 2024

Radiolab helps name a quasi-moon of Venus

On This Episode

Latif Nasser

Co-host of Radiolab

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

Sometimes, misunderstandings can spark beautiful adventures. This week on Planetary Radio, we explore the story behind the naming of Zoozve, a quasi-moon of Venus, with Latif Nasser, co-host of Radiolab. He shares how a typo on a space poster led the Radiolab team on an epic quest to convince the International Astronomical Union to name this quirky space object. Then, Bruce Betts, our chief scientist, pops in for What's Up and a discussion of some of the things asteroid hunters have found lurking in our Solar System.

- Radiolab

- Radiolab: Zoozve

- Radiolab: Breaking Newsve About Zoozve

- What is Venus' quasi-moon Zoozve?

- Venus, Earth's twin sister

- Every mission to Venus ever

- Every picture from Venus' surface, ever

- Why is Venus called Earth’s twin?

- Lowell Observatory

- NEO Surveyor, Protecting Earth from Dangerous Asteroids

- Demystifying near-Earth asteroids

- Sizing Up the Threat from Near-Earth Objects (NEOs)

- Why we need the NEO Surveyor space telescope

- Defend Earth

- Gene Shoemaker Near-Earth Object Grants

- Asteroid Apophis: Will It Hit Earth? Your Questions Answered.

- OSIRIS-REx returns sample from asteroid Bennu to Earth

- What was the Chelyabinsk meteor event?

- Planetary Radio: Geothermal activity on the icy dwarf planets Eris and Makemake

- Planetary Radio: Lucy's first asteroid flyby reveals a surprise moon

- Planetary Radio: Celebrating the OSIRIS-REx sample return

- Planetary Radio: The asteroid hunter

- Planetary Radio: OSIRIS-REx becomes APEX

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- Register for The Planetary Society Day of Action

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Radiolab helps name a quasi-moon of Venus. This week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our Solar System and beyond. Sometimes misunderstandings can spark beautiful adventures. Today, we'll dive into a mix of serendipity and science as we explore the story behind the naming of Zoozve, a quasi-moon of Venus. Joining us is Latif Nasser, the co-host of Radiolab. He'll share how a typo on a space poster led the Radiolab team on an epic quest to convince the International Astronomical Union to name a space object. Then, the great Bruce Betts, our chief scientist, will pop in for What's Up and a discussion of some of the things that asteroid hunters have found working in our Solar System. If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it. The motions of objects in our Solar System, like any group of things that are dancing under the influence of gravity, are complicated. Our understanding of celestial movement has evolved dramatically since the early days of. At the heart of this evolution is Johannes Kepler. He was a 17th-century German astronomer whose work fundamentally changed our understanding of how celestial bodies orbit. Kepler's first law revealed that orbits are not perfect circles, but are actually ellipses. This concept seems simple, but at the time it was truly revolutionary. Of course, the cosmic dance floor is far more complicated and crowded than Kepler ever knew. Beyond planets orbiting their stars in elliptical paths, our Solar System is a place. We have moons and rings and asteroids and comets, and they're all interacting under this dynamic ballet that's governed by gravity. This brings us to one of the more interesting performers in this dance: quasi-moons. Unlike moons that directly orbit their planets, or even mini moons that are sometimes captured by a planet's gravity and orbit them temporarily, quasi-moons follow a seemingly more complex path. At first glance, they appear to orbit the planets themselves, but really they orbit the Sun. Quasi-moons are asteroids that share a very similar orbital path and period to the planets that they're associated with. The gravitational interactions between the quasi-moon, the Sun, and the planet that they hang out with lead to this situation where the quasi-moon sometimes speeds up, pulling ahead of the planet in its path around the star, and sometimes slows down, which causes it to lag behind that world. From the planet's perspective, a quasi-moon seems to trace this really weird path, often described as a horseshoe orbit. But from the broader view, its path around the Sun is precisely the kind of ellipse that Kepler described. I know it's a hard thing to visualize, so I'll put some resources on the web page for this episode of Planetary Radio. That'll help. You can find those at planetary.org/radio. Venus has no moons. But in 2002, an astronomer named Brian Skiff at Lowell Observatory in Arizona, USA discovered an object that would later be understood as the first known of Venus. This object was initially given the temporary title 2002 VE68. But on February 5th, 2024, it got a much snappier name: Zoozve. That's all thanks to our friends at Radiolab, the scientists that they met along the way, and of course the International Astronomical Union, or the IAU. Part of what the IAU does is give official names to objects in space. Radiolab is a podcast and radio show from WNYC, New York Public Radio. It's hosted by Lulu Miller and our next guest, Latif Nasser. Their show asks some really profound questions about everything from science to legal history and uses investigative journalism to share the answers with their audience. Latif Nasser met me at Planetary Society Headquarters to share this totally wacky but awesome story. Hi, Latif.

Latif Nasser: Hi.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Thanks for joining me at Planetary Society Headquarters.

Latif Nasser: Are you kidding me? This is such a treat. It's an honor to be here.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We're such fans of your show here. It's wonderful to have a podcast buddy in the house.

Latif Nasser: Oh, I feel like I'm totally starstruck being here, so thanks for having me.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: When we heard your show about the Zoozve saga, we knew that we had to write an article about it. People loved it, so I'm really happy to have you on the show to talk about it because clearly this is one of the coolest, cute little space stories to come out in a while.

Latif Nasser: It's my honor. Did not see that coming when we were making it. Yeah, it's only after it came out that I'm like, "Oh, wow. Huh. This is more people than just me care about this."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How did this whole Zoozve naming saga begin?

Latif Nasser: Yeah, so it started a little over a year ago? Something like that. I was putting my kid, my then two-year-old, to bed. I was putting them right in the crib, and I noticed sort of out of the corner of my eye that we had a Solar System poster we had bought off of the internet. I noticed out of the corner of my eye that Venus had a moon, and I was like, "That's weird. I didn't remember learning about that in school or anything." I put my kid to bed, and then I was going to my bedroom and I just Googled on my phone, "Does Venus have a moon?" The first result that came up was from NASA saying, "No, Venus has no moons." I was like, "That's weird." And then the next morning when I got my kid up, I looked again. I was like, "Yeah, there is. It's true. There's a moon on Venus on this poster." And the thing I hadn't noticed night before, it had a name, and the name was this name Z-O-O-Z-V-E or Z-O-O-Z-V-E. I was like, "That's even a weirder," because I never heard of that name. So then I Googled that, and then there was nothing in English. Nothing. How often do you Google something and there's nothing in English? At first, I almost was mad at first where I was like, "Who's giving my kid this? Who's lying to my kid?" Is this a prank? What kind of weird prank is this? The thought I had, I was like either this is a Pluto type situation where there was a thing and then it got demoted, or is this poster out of date in some way? Or the website that I saw from NASA, maybe that's out of date? Or the other thought I had was this is clearly a prank. This is the artist's dog's name or something, and they just sneaked it in and they thought no one would notice. All of this was weird enough and mysterious enough that I was like, "Okay, now I have to find the answer."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Most people when Google failed them, they'd probably just "Go, okay, it's a prank or whatever." But you had to take it to the next level and then did the logical thing, I guess, and called up one of your friends that worked at NASA.

Latif Nasser: Yeah, because I was like, who else would I call? When did I buy this poster? Where did I buy this poster from? I couldn't even find that. I was like, "Okay, it's just easier to call my friend Liz." Having worked in the media department at NASA for a long time, and having been a reporter even before that, she's used to fielding calls from reporters. I'm like, "Clearly, if this is a thing, she'll know what it is." Clearly, she would have gotten this question before somewhere from someone, which turned out not to be true.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But ultimately she did figure out the answer.

Latif Nasser: She did. She did. She was so good. At first she said, "No, no, no. I have no idea what you're talking about. I've never heard of the Zoozve. Venus doesn't have any moons. What are you talking about?" And then she texted me and she was like, "No, no, no, I figured it out. It's not Zoozve or Zoozve. It's 2002 VE." Which is the format for how these near-Earth objects and how these objects in general, all these asteroids in our Solar System get named. It's like an auto-generated date stamp or something. It got discovered in 2002. At first I was like, "Oh, VE like Venus." It's, no, not even that. V corresponds to a two-week chunk of the year, like [inaudible 00:08:24] I don't know, forget it was, maybe it's in November something, and then E... It's actually 2002 VE68. It was the E and the 68 referred to the order in which in that two-week window of 2002 that it was discovered. Anyway, very obscure naming protocol there. But when I talked to the illustrator, I asked him, I was like, "Is this what, it's 2002 VE? Is this your dog's name, or what is this?" He was like, "No, no, no," so he outlined his process for. He has multiple steps, including one where he writes it out in pencil before he then transfers it to ink or whatever it is. It's in one of those intermediary steps of his process. In his head he had written 2002 VE, but then in his head he was like, "No, no, no. It's clearly Zoozve. That makes more sense than it being 2002 VE." It was a sort of a transcription error, but it was almost like a typo kind of a thing. It was almost as I was saying it, he was like, "Oh, that's the mistake I made."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It takes me right back to the early days of the internet where we used to use leetspeak to talk to each other with numbers.

Latif Nasser: Oh yeah, that's right.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I think if I had stared at it long enough, I might've thought of that. But that is so funny and a weird moment that this accidental typo that ended up on a poster ends up ultimately contributing to the real name of this body. But you took it to a step even further. You called up the person Brian Skiff at Lowell Observatory that originally discovered this object to see if you could work with him to actually name this object Zoozve.

Latif Nasser: Yeah. Well, the funny thing about that is, so when I first heard from Liz when she cracked the case, and she was like, "Okay, it's 2002 VE68," I was like, "Great, tell me about 2002 VE68." Liz was like, "How would I know? I don't know anything about this thing." She just gave me the briefest outline of what it is. And so I was like, "Okay, so now I need someone to explain what the heck this thing is." And in my head I was like, "Okay, I'm going to go to the person who discovered it, obviously. Obviously that person will know everything about it." And then when I tracked him down, Brian Skiff, who what a nice guy. Talk about someone who's like a star-crossed lover, someone who just loves observing more than anything, and who's been doing it every night and every weekend for decades. This guy Brian Skiff at Lowell Observatory. I asked him. When my producer Katie, she emailed him, and when I first talked to him, I can't even tell you how anti-climactic it was. I was like, "Okay, 2002 VE68, what is this thing?" He's like, "I have no idea what you're talking about. I don't think I've ever heard of this." I'm like, "I never heard of it. You discovered it." He was like, "Oh. Yeah, I guess maybe." But what a flex, right? How great a scientist do you have to be that someone finds something you discovered and you don't even remember it? Yeah, he was part of this LONEOS mission, which is I guess one of many of these missions that were funded by Congress to survey. They had some kind of a quota. It was like 90%, or 95% or something like that, of all the near-Earth objects around the time that Deep Impact and Armageddon came out, basically. But they would be discovering so many things in a single night that any one object he just didn't know. They just found it. They would learn enough of it from either that first sighting or a second sighting to know that whether it was heading for Earth, and that was the only thing they were interested in. Once they found out that it wasn't coming to hit us, it was like, okay, move on to the next thing, move on to the next thing, move on to the next thing. But for me, I mean it was such a weird thing because I was obsessed with this object and I found the person who discovered it. It felt like the meeting The Wizard of Oz or something. Getting all the way to the wizard, and then the wizard being like, "I have no idea what you're talking about." It was very, very funny. But then so having even gone all that way, then I had to go a few steps even further to find someone who actually did know what this thing was, who could tell me a little bit more about it. That's when I met these two people. One is named Seppo Mikola in Finland, and one is named Paul Weigert in Canada, and they also have other co-authors who worked with them. But both of them really knocked my socks off. They were the ones who really made me fall in love with this thing.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's what's so interesting about space. It's like any subject you pick, literally any subject, you dive in a little deeper and it gets weirder and weirder and more interesting. And then you end up learning things like this is a quasi-moon. And not just a quasi-moon: the first quasi-moon ever discovered.

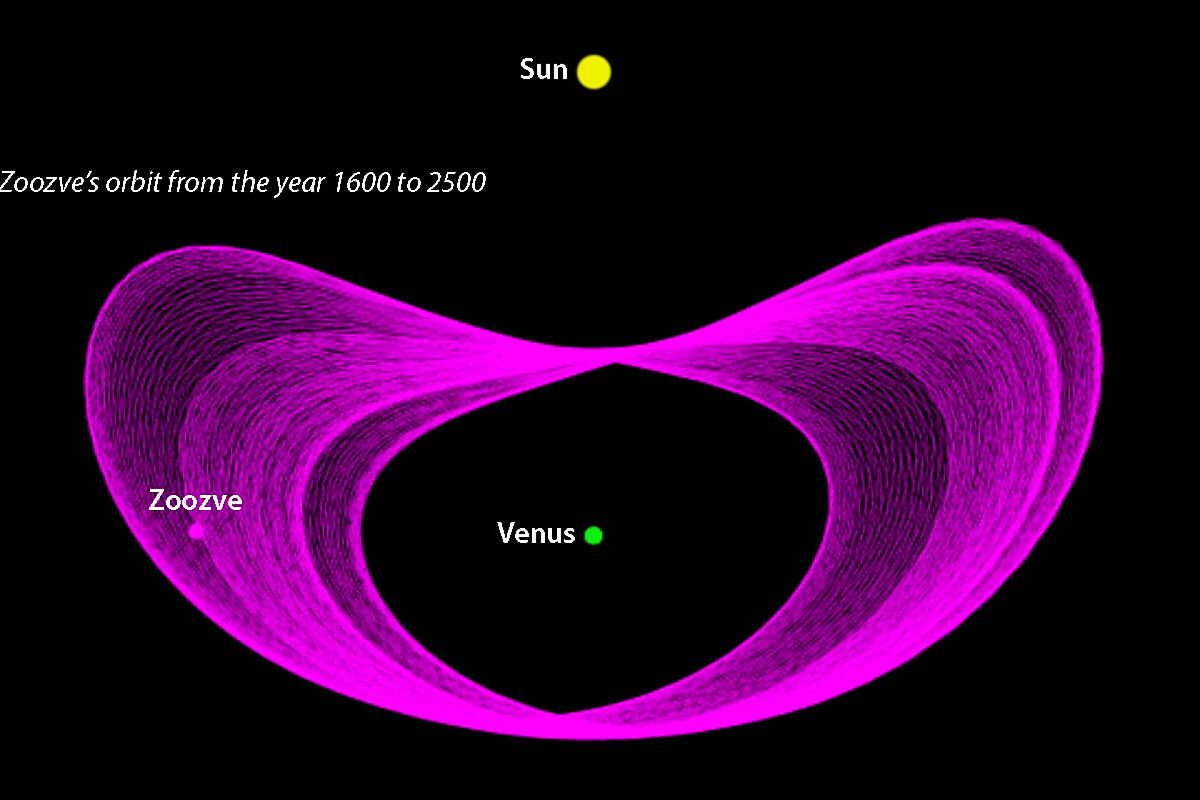

Latif Nasser: That's right. That's right. That's exactly right. I was like, "What even is this?" But Paul Weigert in particular, he was the first one of them I talked to. He just sort of laid it out so clearly, and he was like, "Look, okay. Everything in our Solar System basically dances with one other thing. Now this thing, this thing is doing a a different dance, and it's doing it further away than a regular moon would. It's not just doing it with planet, it's also doing the same it's orbiting at the same time the star that the planet is orbiting. It's doing these two things simultaneously and that it's even orbiting Venus. It's outside its sphere of influence. It's outside where a normal moon would be. It's further away." That this was a thing that had been hypothesized, that had been dreamt up over a hundred years ago. That this was the first one anyone had ever found, that was so... I was like, "Whoa, huh. This is a whole new kind of thing."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, it's one of those things that you know conceptually exists, but trying to find an object like a quasi-moon establish what it's going around takes quite a bit of observation. Finding one like this just opens the doors for everyone to find more. Since then we've found several quasi-moons out around the Solar System, including I think seven of earth.

Latif Nasser: That's it. That's so astonishing to me that I don't know a lot, but I know enough about the history of astronomy to know that people have been looking up for a long time. Way longer than we've been alive, way longer than any of the fancy toys that we now have been around. You wonder the question, which how did people not even see this until now, until the 2000s? To me, part of it is a technological story. It's a story that it's like technology and the political will and whatever, the money, to say, "Okay, let's actually look. What is actually around us?" It's like, "Oh, look, there's a whole new thing that we didn't know whether it could actually exist or not. Now we know for sure and now let's actually look for them. And oh, hold on. Now we're finding them, and we found another and we found another, and we found another." That's really cool.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So much has changed in the last few decades in our field. It's just going so incredibly fast, and I feel like we'll probably find a lot more quasi-moons in the coming years because although the NEO Surveyor mission, the near-Earth object Surveyor spacecraft, has been delayed several times, the budget includes it. NASA's budget does include this spacecraft going up, and we're going to get so much more information about what's going on up there. This is just a Sarah prediction. I would say we'd probably find several more quasi-moons in the next coming decades.

Latif Nasser: Wow. Amazing.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Who even knows what's out there.

Latif Nasser: Yeah. So much of why this is meaningful to me goes back to that map, that Solar System poster that is on my kid's bedroom. That's the one we all learn about when we're in school. In that poster, there's a lot of blank space. There's a lot where it's a very lonely place. This neighborhood we live in it only has, I don't know what, eight houses or something. It's a lonely place. And then to be like, "Oh, wait a second. There's all these other things here that are just not on the map." They're weird and they have their own strange logic and they're just doing their own weird dance. There's all kinds of other stuff here.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, and every time you get closer to understanding more about them, the weirder they get. The closer you get to asteroids, the more you realize there's rubble pile asteroids and metallic asteroids that do things you can't even predict. They might have these weird little extra moonlets you didn't think were going to be there. Or even in the outer Solar System. We recently learned that the dwarf planets Eris and Makemake actually potentially have geothermal, hydrothermal processes going on them. They're way out there in the Solar System. Once we identify and find these things, then we take a closer look. Each time it reveals something new about the way that the universe works that we really weren't aware of.

Latif Nasser: It's so cool. I think especially, again, from the little I've learned about the history of astronomy, it's so cool that we get to live in a time where all these blockbuster discoveries are getting made where you get to learn in real time as we're all learning them. They're not things you're learning in a textbook because someone figured it out 500 years ago. This is a thing that's like you're getting a push alert on your phone. It's pretty exciting.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll be right back with the rest of my interview with Latif Nasser after the short break.

Kate Howells: Hi, this is Kate from The Planetary Society. How does space spark your creativity? We want to hear from you, whether you make cosmic art, take photos through a telescope, write haikus about the planets, or invent space games for your family. Really any creative activity that's space related, we invite you to share it with us. You can add your work to our collection by emailing it to us at [email protected]. That's [email protected]. Thanks.

Casey Dreier: This is Casey Dreier, the chief of space policy here at The Planetary Society, inviting you to join me, my colleagues, and other members of The Planetary Society this April 28th and 29th in Washington, DC for our annual day of action. This is an opportunity for you to meet your members of Congress face-to-face and advocate for space science, for space exploration, and the search for life. Registration closes on April 15th so do not delay. I so much hope to see you there at our day of action in Washington, DC this April 28th and 29th. Learn more at planetary.org/dayofaction.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's cool though that people way back in the day had all of the basic understanding of the math and things like that that could have ultimately led them to this conclusion. As an example in your shows, you were talking about the three-body problem, which was proposed fairly early on in physics. This idea that you can use two bodies orbiting each other, you can calculate out how that situation is going to go down. But if you put one more object in there gravitationally bound to the others and just let it play out, there's no way to predict how that thing is going to fall out. The entirety of space is going through this strange dance. They could have intuited that from the math back then, but it's not until we have all these people staring at the sky, finding this data looking for these objects that we can really go, "Oh my gosh, there it is." Here's this quasi-moon playing out this beautiful intricate dance with all the other things in the universe around us that too are undergoing this strange dance with each other.

Latif Nasser: Yeah, and even at a timescale that seems very minute for everything else. But even within a few hundred years, we don't know where this thing came from or where it's going. We can't tell you. In my imagination, everything is just, again, from that map. From that poster, everything's just doing its regular laps around. They're speed skating around the rink over and over and over again, and that's sort of how you just picture everything. They're like, "No, there's just weirdos who are doing their own weird improvised figure skating routine." It's so cool to be like, "Huh, didn't even think that was happening on this same ice rink."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, we don't have perfect understanding of everything. So maybe if you understood every object in the entire universe and had a supercomputer capable of calculating it, maybe then you could figure these things out. But this whole story just takes me right back to college my first astrophysics class. I told you this story a little bit earlier-

Latif Nasser: No, I love it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But in my class, one of my teachers actually for the first homework assignment assigned us a problem to solve the three-body problem. I spent four days trying to solve this thing only to come back to class. A third of the class had dropped out at this point because it was impossible. And then we learned from the teacher, yes, in fact it is impossible to solve this. I was just testing you.

Latif Nasser: Epic troll.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Although I will say if I had just read a couple of pages further into the textbook, I would've found out that it was impossible to solve. If you're studying you hit an impossible problem, please just read the textbook a little further. It'll save you some days of angst. Now, we know that there's this quasi-moon. We've solved the mystery why it was named that on your poster, but why did you then take it to the next level? You wanted to see if you could go to the International Astronomical Union and make this an actual name.

Latif Nasser: Yeah, it just felt like this is the dumbest name. Why would anything be called 2002 VE68? It was like, "Oh, this was this auto-generated name. It's almost like a license plate number or something." I was like, "Oh, okay." But things do get named, but this thing isn't. But it has to be a Requisite amount of studied and documented to earn the right to have a name. It met that threshold, so it's nameable. But it just hasn't been named yet. The person who theoretically has the naming privilege, they call it, is the guy who discovered it. The guy when I talked to him, Brian Skiff, not only has he already named dozens of things, he didn't even know he discovered this thing. I was like, "Okay, I don't think he cares what it's going to be named." And then I had this funny vision. If I was able to name this thing or if we were able to name this thing and if we were able to name this thing Zoozve, that retroactively makes the poster correct, actually. I don't know. I thought that was so funny that I could somehow through this whole journey retcon, fix, the poster on my kid's wall. I got to do it. We got to do this. And then that was the vision I had. A whole bunch of the Radiolabers who I was working with, Sarah Qari, Becca Bressler, Ekedi Fausther-Keeys, Soren Wheeler, Pat Walters, Lulu Miller obviously, a bunch of the other people I was working with, we all drank the same Kool-Aid basically. We're like, "Zoozve. It's got to be Zoozve. We got to name this thing Zoozve." We enlisted Brian Skiff and we enlisted the illustrator as well, and we put in an official proposal.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, it's a beautiful example of how even a group of people who aren't just steeped in space all the time you get this moment to feel connected to the universe and feel like you can do something. It mobilized the whole group of you to try to go in on this.

Latif Nasser: Oh, yeah. And then also when we were putting out the episode, we had scheduled it such that we were like, "Okay, the name will definitely be in by the time we've aired this episode." We'd put in this proposal and we were like, "Okay, it's going to take a couple months." We budgeted a couple months, and then we had booked an interview with the secretary of this group, the Working Group for Small Body Nomenclature, to be like, "Okay, what's the final verdict?" That's what we were going to put right at the end of the episode. We were just waiting for that last puzzle piece to finish the whole thing and hit publish on the episode. And then he came back and he was like, "Jury's still out. We don't have enough votes. Sorry, I can't tell you yet." And so we were really bummed. We thought that everyone was going to hate the episode because it was like a non-ending.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: No, it's a cliffhanger.

Latif Nasser: It's a cliffhanger. But that's what ended up happening. It flipped itself into a cliffhanger. And then I wrote about it on Twitter and did some TikToks and stuff, and people got really, really... And through the podcast itself. People got really, really invested in it. Millions and millions of people just lost their minds over it. There were people who were naming their pets Zoozve, there were people who were like... Yeah, there were just all kinds of people who just... I was hearing about in classrooms all over the world kids were talking to their classrooms about it and trying to get their classrooms excited about naming it and stuff like that. And so it was one of those things where I was like, "Oh, wow. Everybody got behind this absurd..." I mean, it's internet logic, right? I guess in a way. It's a version of Boaty McBoatface or something. But it was just one of those things where I was like, "Oh." It felt like the whole world wanted this typo to be like bronzed, etched in the heavens. And then that's what happened. Then we finally heard a few weeks later that was it, that it was for real, that Zoozve was going to be the name now and forever.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Congratulations, excellent work. But also, how did the artist of this poster react when you let them know that this actually ended up and you had fixed the problem with the poster?

Latif Nasser: Yeah, his name's Alex Foster and he's from the UK. When I first called him, I didn't tell him what even... I was like, "There's something on one of your posters that I think is really interesting, and I'd love to... I'm not going to tell you what, but let's get in the studio." He was like, "It's my New York City poster, right?" I'm like, "No, it's not your map of New York City." So then finally we got to the bottom of that it was Zoozve. He was amused and he was like, "I don't know about astronomy. I just make posters. I didn't make it up, but I don't have citations for it. I don't know. You figure it out." And then by the time when we actually named it and I went back to him, I told him before it went public and everything, he was totally dumbfounded and stupefied. He was so excited. He then told me that even as an illustrator, he had never ever considered getting a tattoo before of his work or anything like that because he's an illustrator. I'm very critical of images and stuff. He's like, "There's nothing, no image, that I would ever love long enough that it would justify a tattoo." He was like, "I think I'm going to get a Zoozve tattoo." I haven't heard from him. He was really seriously considering it. I don't know if he for sure got it or not, but he was really seriously considering it. Which was I found a very high tribute, but also it was the journey he started so it's his tattoo to get more than anyone.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I hope he does because opportunities to name bodies in our Solar System do not come by that often. I understand that because of this adventure you've been through with the IAU that you're working on a new project now to help more people name a new quasi-moon of Earth.

Latif Nasser: Yeah, because it was so fun and it was so strange this little journey we went on and where we got obsessed with quasi-moons. Just nobody knew that quasi-moons what they were, that they existed. I mean, I didn't before this whole little saga. Because we had just met all the people on... We met the secretary of this naming committee. I looked up because Earth has all these quasi-moons, so I got interested in the earth quasi-moons, and some of them have been named, but I was like, "Oh, but there's some here again that are in this funny category of they are nameable but not yet named." They're up for grabs. The people who discovered them discovered them as part of these similar big survey programs where it's not really any one person who feels like they discovered it, and so you're not taking those rights away from somebody. Besides those objects have been sitting there and they could have been named until now and nobody named them. They're just sitting there. We broached the idea with Gareth Williams, who's that secretary of that nomenclature group, and he was like, "Yeah, maybe we could do that." They partnered. They've done maybe even with you all before naming contests. I was like, "Yeah, I think we should do that. We should do that." There are enough Radiolab fans all over the world, and it is also a public radio show, so it's free. It's open to everybody. There's a lot of people who listen to our show in a lot of different places. Yeah, so we're like, "This would be great." This was so fun that we got to do it, but in ours, we knew what the name was going to be. But let's do one where we don't know what the name is going to be. We're going to solicit from anybody. Anybody listening to this, if you have an idea for what you think an Earth quasi-moon should be called that has mythological origins or connotations, send it to us. We really, really want to hear it. There's going to be some sort of way for people to vote on those naming proposals, and then eventually we're going to have one. That's going to be the name of this Earth quasi-moon, which feels even more proximate to us and even more special to who we are in our neighbors in this hood.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've helped name a lot of spacecraft and places on other worlds and some worlds themselves over here at The Planetary Society, so I'm sure a lot of our listeners would love to participate in this. How should they propose a name to your team?

Latif Nasser: I don't know yet to be honest because we're taking our time. In the next few weeks to months, we will announce on the Radiolab feed. Obviously, we'll share with our friends like you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's so exciting, and I'm really glad that you're taking it to this next step. Because what a funny, hilarious, and ultimately very meaningful arc for this story to go, from a typo all the way to an opportunity for people to help us name a new world in our Solar System. There's so much of this story that we can't even get to in the show right now. If people want to learn more about this, I'm going to put the links to all of the Radiolab episodes about Zoozve on this page of Planetary Radio so you can learn more about it. Hopefully in the future when this naming contest actually becomes a real thing, I would love to have you back on so that everybody knows that now is the time and we can rally together to name this new world in our Solar System.

Latif Nasser: My pleasure, Sarah. I live just around the corner. I'm happy. I'll come anytime.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Seriously, thank you for joining me and for sharing this story, and for going totally extra and getting this name put on this world.

Latif Nasser: What's life for if not going extra?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Thanks, Latif.

Latif Nasser: Thank you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know that we have a lot of Radiolab fans in our audience. When I told Planetary Society members in our member community app that I had spoken with Latif Nasser, the outpouring of love for Radiolab was truly beautiful. I promise we'll keep you updated on their upcoming contest to help name a quasi-moon of Earth. Now let's check in with Dr. Bruce Betts, our chief scientist for What's Up. Hey, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hey, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I love this story because it's a hilarious example of one of those moments when people just accidentally try to mispronounce one of our crazy number letter space names and then inadvertently end up naming an object in space. It's so funny.

Bruce Betts: No, it's very funny. I don't think there's a lot of precedent for it, but I'm not sure.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, I don't think so. This is probably the first example of that. It's a really funny consequence of the fact that we give these really obscure names to space objects.

Bruce Betts: True. They sound obscure, but they're just cataloging numbers. Because so many objects are found that they just use a sequential system with the year and letters to designate the half month that it's found in, and then which object in that month. It ends up sounding weird like 2002 VE68, but there's a very practical reason since literally millions of objects have been found. And so having some way to name them before you know what the heck they are is useful.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What I love about this too is that this is actually related to planetary defense because they found this because they were looking for near-Earth objects. Ultimately after looking at where it was going, they figured out that it was one of these quasi-moons in orbit around Venus. Or rather a quasi-moon that's an orbit around the Sun but appears to orbit around Venus because it's a quasi-moon and a horseshoe-shaped orbit. None of that would've happened without all these efforts to protect our planet from near-Earth objects.

Bruce Betts: This is true, which is something that as you know and listeners know, The Planetary Society finds very important. One of our three things that we focus on is planetary defense, meaning protecting the Earth from asteroid impact. And so yeah, there are people looking thankfully, and we need more looking and more other stuff. We're working on it, and the world is working on it. We're getting there slowly but surely.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, part of the way that we help out with this effort is something that you've championed really hard, which is our Shoemaker Near-Earth Object grant program. What are some other cool discoveries that have been made through this grant program?

Bruce Betts: The grant program started in 1997, and at the time there wasn't much in terms of professional surveys looking for these objects so there were a lot of discoveries. But really what we funded through the last couple decades were a lot of things focused to support the professional surveys that now exist. And so they do. Instead of finding something, they may help determine that it's not one object, but it's a binary. Or figure out exactly what its orbit is and whether it'll contribute to whether it'll hit earth rather than the initial discovery. But we haven't picked up more discoveries from our winners in the last two or three years because we've got some great Southern Hemisphere locations that right now there's no consistent professional survey down there. If you go way back, they were in one of the three discoveries of Apophis, which briefly held the highest probability of impact in a long time. But then with more observations was not and will come by in 2029 closer than our communication satellites. Apophis, one of its discoverers was a Shoemaker NEO grant winner. We had over one kilometer object discovered in the last two or three years by some of our winners in Brazil, and that's just unusual because those are the particularly terrifying global disaster objects, which fortunately we found over 90% of. But he still found one. And then also there was in 2013, there was an asteroid that eventually was named Duende that was found by a Spanish Shoemaker NEO grant winner that we were watching it come by closer than our geostationary satellites. Then within the same 24-hour period, completely unrelated Chelyabinsk happened. There was an impact of an object that no one saw coming out of the Sun over Chelyabinsk, Russia. And so those are just a few that pop to mind, but I mean, there have been many hundreds discovered by our winners and many ens of thousands measured for their locations and their physical properties, thanks to the great work of these amateurs. That they don't get paid for it, but they have amazing observatories. We help them upgrade the observatories to get higher sensitivity, or to have it robotic remote control operated. Basically, do a great job supporting the professional surveys.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We were actually talking about that situation with Chelyabinsk and the other object coming in at the same time on a recent show with Dante Lauretta. Which I love that story because he was literally on the news his first time as a NASA official scientist talking to news agencies and telling them that they were totally safe only to realize Chelyabinsk had happened that same day. He kept reiterating like, "No, we're totally fine." They're like, "No, we just saw it on the news."

Bruce Betts: No, we know it's not going to hit. Yeah, no. We had a video conference putting it out over the internet with the guy in Spain who discovered it. All were scrambling to figure out what the heck just happened with Chelyabinsk. Then of course there were the questions. Were they related? You'd think they would be statistically, but no, it was the statistical improbability because they were on totally different orbits unrelated to each other.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: This brings up another question for me that you just kind of pointed out earlier. We definitely have more coverage in the Northern Hemisphere looking for these objects than we do in the South. Why is that?

Bruce Betts: I mean, it's where they've built observatories that are dedicated to this. Well, also the fact that you have something like 90% of the world's population is in the Northern Hemisphere, and so there's just less down there. But we've had Australia used to have some survey, but then they had issues, got closed down. Anyway, it's coming with what was LSST, the Vera Rubin Telescope that'll be built down there and start being really operational in the next couple of years. One of the things that we'll do will be finding objects looking for NEOs as well as a lot of other objects. But it's because that's where the observatories were is the simple answer. The US had observatories built largely in the US, and the US has been the one funding the major surveys, although European Space Agency has been getting more and more up to speed with European sites. You have to put your site somewhere else. It was using the existing telescopes is the very long answer to your very short question.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But this just shows even more so the value of this grant program. I love everything that we do with all of our grants to people, but there is a real need for more coverage on this subject. It makes me happy to know that we can help bolster people in the Southern Hemisphere that are trying to do this really important work.

Bruce Betts: Yeah no, it's been great. Over the course of the program, we've awarded 70 grants, but they've been spread out in something like I believe it's 21 countries. On every continent but Antarctica. We're still working on that. It's been very successful. There are some really talented people willing to devote a lot of time and a lot of their own money. We're able to give them that extra push to take what's already good observations and make them great observations that can try to keep up with the surveys, or participate in things like studying binary asteroids.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Not all heroes wear capes, man. Some of them just use telescopes.

Bruce Betts: Actually, most of them wear capes also, but that's just a strange quirk.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We should start giving capes out to people who win our grants that say planetary defender on them or something.

Bruce Betts: Oh, my gosh.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We should totally do that.

Bruce Betts: Well, we're getting you a cape first and you've tried out and wear it around, and then we'll see where we go.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Happy to help. Most of this episode we talked about Zoozve, this quasi-moon. As we said earlier, it's not like this object is actually orbiting Venus. It appears to do so, but it's actually orbiting the Sun. But that means it's in this really unstable situation. What makes these quasi-moon orbits so unstable, and why do they eventually just go flying off?

Bruce Betts: Rough family life growing up, usually.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Relatable.

Bruce Betts: Yeah no, they're unstable because they don't have something that they're locked into a stable orbit. And so they get gravitational tugs from the other planets, from Earth depending on where they are, even from Jupiter. But just other tugs that eventually will tweak their orbit and send them into a different orbit. And so if you're going around one thing, you're doing pretty well. But if you're in this awkward orbit going in and out in the Solar System, yeah, you'll get by for a while. But I think these quasi-moons can be quite unstable in astronomical time sense, meaning tens, hundreds, or thousands of years doing that. I just wanted to point out, maybe it was discussed in your interview, but they often show plots of these objects. They look like they have these bizarre orbits because they put it in the frame of reference like a Venus in this case, so it bounces back and forth on the sky. But if you actually look at its orbit, it's much less weird. It's a standard ellipse going around the Sun and coming out past Venus. But it's got a period that's the same as it goes around the Sun in the same period as Venus's much more circular orbit. And so it always hangs out in the neighborhood of Venus because it's orbiting faster and slower because the elliptical orbit, but in the end coming back around on the same amount of time. I don't know. That just helped me because sometimes I look at these and it's like, that's so bizarre. I don't do well with shifts and frame of reference despite the physics major background.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, it trips your brain out when you see it. I didn't really understand either until I literally watched videos on YouTube. Hopefully I can find some good examples of that to put on this page for this episode of Planetary Radio to get people understanding a little bit because I know for me these visual representations really help. Well, before we move on to your random space fact, I wanted to share this hilarious poem that came in on our member community by Jean Lewin, who's been submitting some really wonderful stuff recently. But in order to understand this poem, I have to share this story first. This is one of the silliest space stories I've ever heard. Back in 1965 during the Gemini Three mission, there are a few astronauts on there. John Young was one of them, and he smuggled a corned beef sandwich on board the spacecraft in his pocket. I think it was given to him by Wally Schirra, who is another astronaut but who thought this was particularly hilarious. He gave him this sandwich. And then while in space, he offered a bite of this sandwich to Gus Grissom. I don't know if people have really thought about this, but you take a bite of something in zero-G, just crumbs fly everywhere. When this sandwich incident happened, it ended up leading to a whole incident review from the United States House of Representatives Committee on Appropriations. Seriously, they had to make rules saying you cannot bring this kind of bread into space. You'll notice people on the International Space Station still mostly use tortillas and stuff like that for this reason. This is "The Corned Beef Sandwich" by Jean Lewin. The Gemini program's hot cuisine with entrees deemed quite bland gave Wally Schirra the bright idea to provide delicious contraband. He had a special sandwich made by a deli near the site, but crumbs went flying all around once Grissom took a bite. This nosh raised quite a ruckus, a scandal it was called, resulting in preventative steps to keep control of what was hauled. Space travelers of the future may mimic the crew's style and try to eat a sandwich too, but it would have to be worthwhile. A cat's corned beef sandwich, now that would do the trick. But it would be really tough to hide because that thing's one-foot thick.

Bruce Betts: You just never know what will inspire great poetry.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But now I'm wondering what are the weirdest things people have snuck into space? I only recently learned that someone took wine with them to the moon during the Apollo era.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, Buzz did communion during his travels, so I assume it was him. He certainly brought the communion wafers.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Wow, that makes that story even more interesting. I'm going to be diving into that a little bit more in the future because we have someone who made a documentary about alcohol and space and all the things that happen with brewing and tasting and all those things. I'm going to be learning a lot more about this. Anyway-

Bruce Betts: Excellent.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... that was my side mission.

Bruce Betts: Well, that's pretty awesome. Did you want to hear a random space fact?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Man, that was a menacing one.

Bruce Betts: Anyway, so I often try to point out to people, whether it be the asteroid belt or space in general, that it's really, really empty. We focus on the really cool stuff that we find that's not the emptiness, or at least most scientists do. But I found on Mike Brown's website, Mike Brown, the discoverer of Eris and various other objects in the outer Solar System, as well as other things, that he had a nice image for this. Which is if you take everything from the center of the Solar System out to the Kuiper belt, it would be 99.999999% empty if you had a top down map view. 99% of that non-empty fraction is taken up by the Sun, so just a whole lot of empty out there in space, which is why I always balk at asteroid fields and sci-fi movies.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I was literally just going to say that. Because there are some really wonderful, very accurate space games out there, but consistently they get the asteroid belts all wrong. Every time I see one, I'm like, "Why are all these objects so close together? Are they perhaps in a ring system that just shredded something?"

Bruce Betts: Shredded.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Shredded. I mean, I know it's more exciting to get to dodge around the asteroids, but that's just not how it is.

Bruce Betts: But that's how the games show it, so it must be true.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yes, an extra nebulae for everyone.

Bruce Betts: And you get a nebulae and you get a nebulae. All right, are we're done?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yep.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody go out there look on the night sky and think about the inside of an orange. Is it dark in there? Thank you and good night.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with even more space science and exploration. If you love the show, you can get Planetary Radio T-shirts at planetary.org/shop along with a lot of other cool spacey merchandise. Help others discover the passion, beauty, and joy of space science and exploration by leaving a review or rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day but helps other curious minds find their place in space through Planetary Radio. You can also send us your space thoughts, questions, and poetry at our email at [email protected]. Or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the Planetary Radio Space in our member community app. Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California. It is made possible by our members from all over the world. You can join us as we marvel at the weird and beautiful story of our Solar System at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. And until next week, ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth