Planetary Radio • Dec 04, 2024

A hundred weeks in space exploration

On This Episode

Olivier Witasse

Project Scientist for ESA’s Juice mission

Daniel Glavin

Astrobiologist and sample integrity scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, co-investigator for OSIRIS-REx

Lindy Elkins-Tanton

Foundation and Regents Professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration at ASU

Bob Pappalardo

Europa Clipper Mission Project Scientist for Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed, the host of Planetary Radio, marks her 100th episode with a look back at the defining moments of the past 100 weeks of space exploration. We'll revisit previous Planetary Radio interviews, including the launch of ESA's Juice mission to the icy moons of Jupiter with project scientist Olivier Witasse. Danny Glavin, the co-investigator for NASA's OSIRIS-REx, shares his thoughts after the triumphant return of samples from asteroid Bennu. Lindy Elkins-Tanton, principal investigator for NASA's Psyche mission, reflects on her team's mission to explore a metallic asteroid. Then, Bob Pappalardo, project scientist for Europa Clipper, discusses the mission's intense brush with Hurricane Milton before blasting off to unlock the secrets of a potentially habitable ocean world. We close out the show with Bruce Betts, the chief scientist of The Planetary Society, for What's Up.

Related Links

- Planetary Radio: Juice mission liftoff: A new era in icy moon exploration begins

- Juice, exploring Jupiter’s icy moons

- Planetary Radio: Europa Clipper blasts off: How the mission team weathered Hurricane Milton

- OSIRIS-REx returns sample from asteroid Bennu to Earth

- The boy who named Bennu is now an aspiring astronaut

- OSIRIS-REx, NASA's sample return mission to asteroid Bennu

- Planetary Radio: A Deep Dive into Asteroid Bennu With Dante Lauretta

- Find your OSIRIS-REx Messages from Earth Certificate

- Cost of OSIRIS-REx

- Planetary Radio: Psyche and Eclipse Company blast off

- Psyche mission successfully launches

- Psyche, exploring a metal world

- The Psyche launch and its journey to a metal world: What to expect

- Psyche Inspired Program

- Planetary Radio: Portrait of a Scientist: A Conversation with Psyche mission leader Lindy Elkins-Tanton

- Planetary Radio: Getting psyched for Psyche

- Planetary Radio: Heavy Metal: An encounter with the Psyche spacecraft

- The Cost of NASA's Psyche Mission to a Metallic Asteroid

- What happened with Psyche? A first-hand account from JPL Director Laurie Leshin

- Planetary Radio: Celebrating the OSIRIS-REx sample return

- Europa Clipper launches on its journey to Jupiter’s icy moon

- Europa Clipper, a mission to Jupiter's icy moon

- Could Europa Clipper find life?

- Europa Clipper: A mission backed by advocates

- Planetary Radio: Europa in reflection: A compilation of two decades

- Planetary Radio: Clipper’s champions: Space advocates and the fight for a mission to Europa

- Planetary Radio: Europa Clipper's message in a bottle

- Year-end giving: Donate to The Planetary Society

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It is my 100th episode this week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society, with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. Today we'll take a moment to celebrate this milestone for our show with a look back at some of the defining moments of the past 100 weeks of space exploration. We'll revisit ESA's Juice mission as it sets out for Jupiter's icy moons, OSIRIS-REx returning precious samples from asteroid Bennu to Earth, the launch of NASA's Psyche mission to explore a metallic asteroid, and the beginnings of Europa Clipper's journey to unlock the secrets of a potentially habitable ocean world. We'll share parts of my previous conversations with members of the mission teams, including Juice project scientist, Olivier Witasse, Danny Glavin, the co-investigator of OSIRIS-REx, the Psyche mission's principal investigator, Lindy Elkins-Tanton, and Bob Pappalardo, project scientist for Europa Clipper.

If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it. I planned to share a different episode this week, but as I was reflecting on the discussions that I've had during my time as host of Planetary Radio, it occurred to me that I've been given the same advice from many people. When you accomplish something great, take a break. You can only appreciate what you've done if you pause and reflect. I've had the privilege of speaking to scientists and engineers during powerful points in their lives, moments of discovery and loss, the culmination of years of work, triumphant launches, and successful sample returns. We'll begin by flashing back to April 2023 and the launch of the European Space Agency's Juice mission.

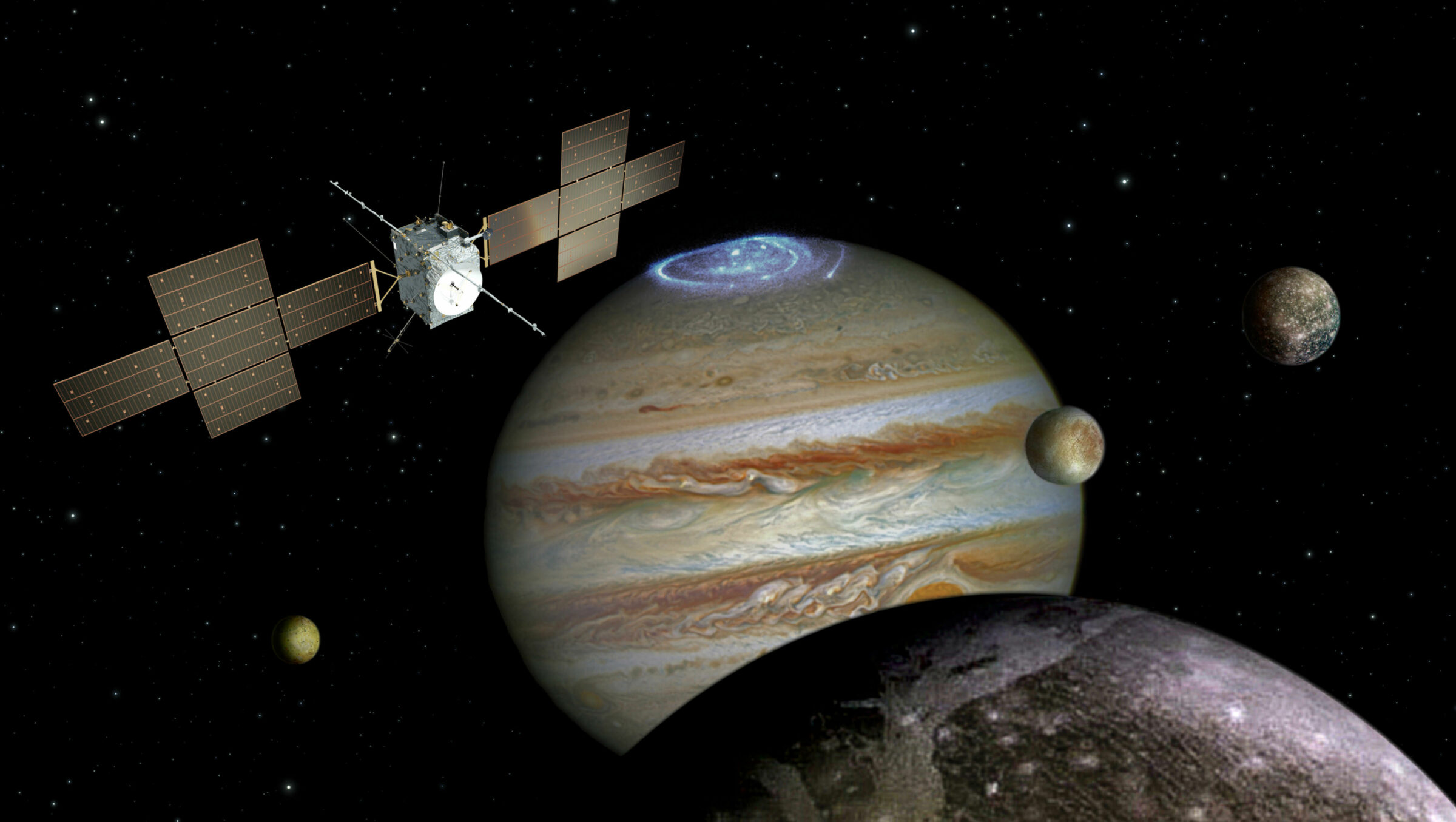

The European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer mission or Juice launched from French Guiana on April 14th. This begins the mission's eight-year journey to Jupiter where it'll study the moons Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede. Jupiter's three largest icy moons may host liquid water oceans beneath their icy crusts. This has prompted decades of speculation about these moons, how they formed and evolved over time, how they interact with Jupiter, and about the potential for life on these worlds. ESA's Juice mission aims to investigate their habitability and expand our understanding of potentially life-harboring locations in the universe. Dr. Olivier Witasse is a planetary scientist and a project scientist for the Juice mission. He joined the European Space Agency in 2003 and has worked on a number of missions, including the Huygens Probe to Titan, Venus Express, Chandrayaan-1, Mars Express, and the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter. That's an impressive resume. In 2015, he joined the Juice mission team and turned his sights to Jupiter. Hi Olivier.

Olivier Witasse: Hi. Hello, Sarah. How are you doing?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'm doing really well. And it's been a really exciting week. I want to congratulate you and everyone on your team for the successful launch of the Juice mission.

Olivier Witasse: Yeah, thank you very much. It was a big week last week. And that's the start of the new phase on the start of the journey to Jupiter.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How are you and the rest of the team feeling? Did you celebrate afterwards?

Olivier Witasse: Yes, of course. Of course we had a few celebrations. I was in our operation center in Germany. So people were split between our operation center in Germany and of course the main site in Kourou in French Guiana. So on both sides there were a lot of celebration. And in the operation center now people are working very hard for the first phase of the mission. So I can relax a little bit from my side, but there are people who are still working very hard on this project.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know that you guys had about a one-second launch window in order to achieve the correct orbit. What's the status of the mission? Is everything on track right now?

Olivier Witasse: As you have seen, so we launched with one day delay. There was some bad weather and lightning activity at the time of the launch on the 13th of April. So we postponed to the 14th. It launched on time. I mean, we had one second to launch, so we did it. And then the launch sequence went absolutely perfectly. All the parameters were nominal, everything was on schedule, so the separation, the injection to space. I mean it could not have been better than that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's good to hear.

Olivier Witasse: The James Webb Telescope, you know their injection was perfect. There was a lot of discussion about that. So for Juice, it's the same. So we don't need any correction maneuver in the next week, so that's good. Then after the separation, there was the acquisition of the first signal from Juice. Here there was a little bit of delay, so people got a bit nervous, but then it went well. And the deployment of the solar panels happened a little bit earlier than expected. So all in all, it went very, very well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's perfect because I know just like the James Webb Space Telescope, making sure that you do the perfect launch and that you don't have to use that fuel means that you can do a whole lot more when you get to your target, which is perfect because you're going to need that fuel to get this mission into orbit around Ganymede at some point.

Olivier Witasse: Now we need a lot of fuel. In fact, more than half of the spacecraft mass is fuel because we have a lot of maneuvers. We have a few maneuvers during the cruise phase. Then we have a big maneuver when we arrive at Jupiter, another major up-sized maneuver when we arrive at Ganymede to enter in orbit around Ganymede, and in between we have 34 flybys of the moons of Jupiter where every time we do a flyby, we need a little bit of fuel to correct if needed. So we need a lot of propellant. So it's good that the launch was perfect, then we can keep a little bit of margins for the future milestones.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And for people who are just now learning about this Juice mission, what is this mission going to do and why is it so important?

Olivier Witasse: Everything is in the title. Juice means Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer. So that means we'll explore Jupiter and the icy moons, which are Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede. And one of the big question for our mission is to understand whether there are habitable places within the icy moons of Jupiter around a planet like Jupiter. The main question is to explore then the liquid water, because when we talk about habitability, the first thing to check is the presence of liquid water. And there is liquid water inside the icy moon. It's kind of strange to think about it, but underneath the surface of Europa, Ganymede, and maybe Callisto, there is more liquid water than on Earth, and Juice will explore that. And because we want to understand habitable places around Jupiter, we will explore Jupiter as well. So the atmosphere, the magnetosphere, and also the full system, so the other moons, Io, a very interesting moon, the dust, and how everything is connected to each other. For example, how the moons are connected to Jupiter via the gravitational force. As a result, there is tides on the surfaces of the moons. So we'll explore that. And they're also linked to Jupiter via the magnetic field line. So there is a lot of magnetic things to discuss, to explore. So it's very a rich mission and very broad. And yeah, we are very excited by it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And this is the first dedicated Jupiter mission by the European Space Agency. Right? What kind of sparked the creation of this mission?

Olivier Witasse: Yeah. So that's the first time we go to Jupiter, so that's a very challenging mission. It's one of our biggest mission in ESA, at least in the solar system exploration as a follow-up of the Rosetta mission for example, this kind of big mission. So a lot of challenges. First we have to have a mission which lasts 10 to 15 years. So there is a lifetime. We go to Jupiter, which is a very hard radiation environment, very difficult to resist for the electronics, the spacecraft, the instrument. We go there where it's cold around Jupiter. While doing the cruise to Jupiter, we go via Venus. Venus, it's a warm environment, so we have to design a spacecraft which can work in the cold environment, in the warm environment. Plus we'll do a lot of very sensitive measurement of electric and magnetic field. That's one of the measurement, very useful to detect the liquid water underneath the surfaces.

And then we need to have a very clean spacecraft from the electromagnetic point of view. We don't want to measure what is coming out of the spacecraft. So the design was extremely challenging for this, and because we are far from the sun, little power, little solar illumination. That means we had to embark huge solar panels. So if you see how the spacecraft look like, you see the big solar panel with a cross shaped, 85 square meter of solar panels, so huge. So we need to find the right solar panels which can work in the cold environment with low illumination conditions, in the radiation environment. So all in all, it's a very challenging mission.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. With NASA's Juno mission, they put it on an orbit that took it very far away from Jupiter and then back in. And the readings of the radiation coming off this thing are unreal. So how is the spacecraft grappling with that level of radiation?

Olivier Witasse: That's one of the big issue of any mission to Jupiter. So that means you have to check what you can do. That depends on your science objective. For example, the Juno science objective are to study Jupiter in detail, the interior, the atmosphere, the gravity field, the magnetic field. So they have a polar orbit and they go very, very close to Jupiter, and then they go very, very far not to be in the radiation belt all the time. So they designed the trajectory depending on their science goal. For Juice, we are mainly interested in the icy moon, so we need to orbit in the equatorial plane of Jupiter, so different orbit than Juno because Juno is a polar orbit. Juice is an equatorial orbit because we want to fly by the moon, so we need to stay in this equatorial plane where there is a lot of radiation environment.

So we need to stay at reasonable distance from Jupiter. So that's why we don't go to Io because Io is very close. We go only twice to Europa because also Europa is very interesting but relatively close. And we focus on Ganymede because it's at a reasonable distance from Jupiter. Ganymede is a very unique moon, very, very interesting. So we made Ganymede as our prime target. So the first thing to cope with the radiation environment is to make sure that your trajectory is fine with that, so not too close to Jupiter for example. And then in the design of the spacecraft, we protect the very sensitive electronics of the instrument and the spacecraft inside the satellite in the core, in the middle of the satellite in what we call vault.

So we have two big cavities in which we put all the sensitive element of Juice, so such they are protected from the radiation environment. And we have more than one hundred of shielding, a bit everywhere in the spacecraft to shield the particular sensitive area. And on the solar panels, which are outside the spacecraft, we put a layer of cover glass to protect again from the radiation environment. So you see we have thought a lot about the design and that was the main requirement is to protect the spacecraft as much as possible from the radiation environment.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And you need to keep all of those scientific instruments able to do their job, and there's a lot of them on the spacecraft. What are the most important instruments on board Juice to help it do its mission?

Olivier Witasse: Well, we have 10 instrument and they have been selected at the same time of course, and each of them to achieve specific objectives of the mission, and they have been selected such that they can work also together to address all the big question of Juice. So there is no one instrument particularly more important than the other. They're all very important because they have selected all together to fit the science objective of the Juice mission. We have three big packages. So we have the remote sensing instruments or the eyes of Juice, so all the cameras, the spectrometers. So we have four of them because we want to take images and to study the geology of the moons and the atmosphere of Jupiter. And then we have spectrometers covering radio, near-infrared, visible, and UV for the atmospheres and for the surface. So that's how Juice will see everything around the spacecraft.

Then we have a package which is called geophysics. That's a very interesting one because that's the first time we fly this kind of instrument to the moons of Jupiter. Here we have a radar to study the first 10 kilometers of the crust, so to penetrate the ice. So we'll see the first 10 kilometers, how is the structure. So that's the first time we will do that. And we have also a laser altimeter, which is very, very interesting because we measure the topography of the moon. So we send laser shots, and then from that we can see the topography, so if you have small hills, craters, and so on. But what is very interesting is we'll come back to the same point many, many times and we'll see the tides of the moon, so how the height of the moon change with time. And that is a way to study the interior and the liquid water.

We have a radio science experiment to study the gravity field and then we have what we can call the nose of the spacecraft is an in-situ measurement of particles, electric field, magnetic field, radio wave to study in-situ what is around the spacecraft in term of particles in particular for the magnetosphere. And that's a way also to detect subsurface oceans. Each of them are very useful and they will be all providing a small piece of the puzzle.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Jupiter has, what, 92 moons I think at this point. But these ones have the potential for subsurface oceans and therefore the potential for being habitable. Juice isn't going to be directly detecting life, but what can it teach us about the potential for habitability on these moons?

Olivier Witasse: Well, first it's to really confirm that there are liquid water. We are pretty sure there is liquid water at Europa, relatively sure that there is liquid water on Ganymede. Callisto there is a question mark, so Callisto is also quite interesting. And the first thing when you want to discuss habitability is to really understand the properties of liquid water. So because we don't know where it is, so at which step. We have some ideas of course, some indication. But for example, the subsurface ocean at Ganymede could be at 100 kilometers underneath the surface, but it can be 110, 20, 120, 150. So we need to know, it's important. We don't know exactly the depth of those oceans. So is it 100 kilometers, 50, 80? We need to know, because we want to know the amount of water that you have there.

And also the composition, we know they are salty because we detect them with the magnetometer, so we know they are salty. That's an interesting piece of physics and detection by the way. But we don't know how much salt do they have there. And the composition is quite important to characterize liquid water. Is it an interesting water for life, et cetera? We'll also be studying the radiation environment because it's good to know the radiation environment. I mean, on Earth we are happy to have the magnetic field, then we have less radiation coming from the sun. So what is the case at Europa when there is no internal magnetic field and Europa is close to Jupiter? What is the case at Ganymede, which is a bit further away, I mean much further away, with an internal magnetic field? That's the only moon to generate its own magnetic field, so very, very special. So what is the role of this magnetic field? Does that help to protect? Not at all? How this interaction between the magnetic field of Ganymede and the magnetic field of Jupiter?

And what is the case at Callisto, the moon which is the much further away with the Galilean moons? So in principle it's better for the radiation environment at Callisto. But at the same time, the moon is far from Jupiter, so the tidal activity is very weak. The moon has probably not evolved since its formation. When you look at the surface of Callisto, it's plenty of craters. So that means the moon, the surface is very young. Probably there is not much geological activity. So is there a liquid water underneath the surface or not? That's an interesting question. And the finding, either a yes or no will be interesting. And then we can compare the three moons. So Europa, which is active with possible geysers, very interesting ocean, but close to Jupiter. Then you have on the other hand, you have Callisto, which is dead. We don't know if there is an ocean. In principle it's not very interesting for habitability and life, but who knows. And then you have Ganymede in between. So a big question mark. So that will be very interesting to know more about those three moons and then to compare them and to understand better the question of habitability and whether around Jupiter there is interesting place to study life. And then to study life, we need another mission.

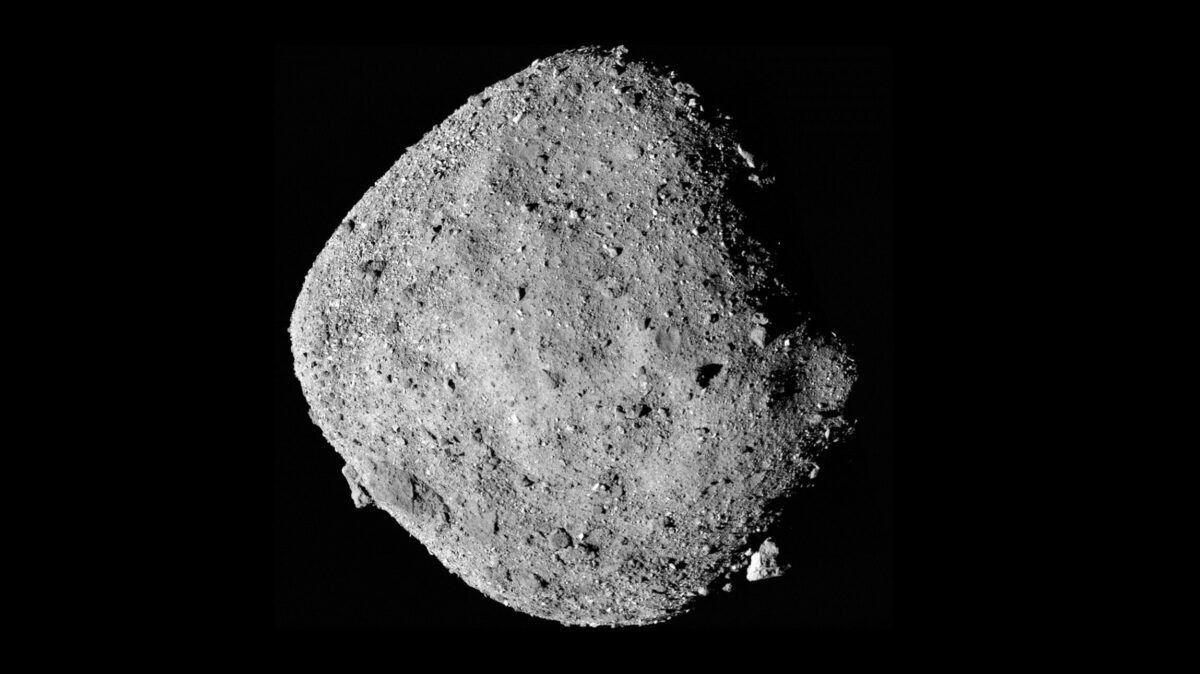

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Juice is still out there on its way to Jupiter, soon to be joined by NASA's Europa Clipper mission. But a year before the launch of Clipper, we were treated to another triumph. On September 24th, after traveling 7.1 billion kilometers over seven years, NASA's OSIRIS-REx spacecraft delivered material from asteroid Bennu to Earth. NASA's OSIRIS-REx mission launched in September 2016 with a primary goal, to retrieve a sample from asteroid Bennu. Samples of asteroids like Bennu can teach us a lot about the early solar system and potentially about the origins of life on Earth. These primordial relics have remained largely unchanged since the early days of our solar system over 4.5 billion years ago. The tricky part is snagging the samples from the asteroid and then bringing them back to Earth for analysis. After reaching Bennu in December 2018, OSIRIS-REx faced the challenge of collecting a sample from a terrain that was far rockier than anticipated.

Of course, in October 2020, the spacecraft team succeeded in high-fiving the asteroid with its TAGSAM device, gathering pristine material from the asteroid, and then preparing to make its way back to Earth with the precious cargo. And now after an intense journey through space and the Earth's atmosphere, the sample return capsule bearing bits of Bennu touched down in the Utah desert on September 24th, 2023. So what's next for the samples from Bennu and the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft? We turn next to Dr. Daniel or Danny Glavin, the co-investigator of NASA's OSIRIS-REx mission. He's an astrobiologist and a sample integrity scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. He's leading the team that will unravel the mysteries contained within the samples returned from Bennu. He's delved into samples from the moon and meteorites, and he's also involved in the Mars sample return mission. I spoke with him just a few days after his return from Utah. Hi, Danny. Thanks for joining me.

Daniel Glavin: Hey, it's great to be here. Thank you for inviting me.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I have to say huge congratulations to you and everyone that's been working on OSIRIS-REx. This is for me, I feel like the biggest space moment of the year.

Daniel Glavin: Yeah, I mean it was incredible. I mean, I was out at Dugway at UTTR for the landing and like everyone, it was just like, please work, I want this parachute to open. This precious sample, please come back safely and uncontaminated. And after putting close to 15 years into this mission, it was really very emotional and stressful until that chute opened and then I was able to relax for a second. But yeah, it's just incredible that we can do these things. I mean going all the way out to an asteroid, collecting a sample over 200 million miles away from Earth, fully autonomously, pick up a sample from the surface, stow it, and then bring it back to Earth, survive atmospheric entry and landing, and now the sample's going to be literally distributed to labs around the Earth to analyze. So it's really a very exciting time for planetary science.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It is. And that just puts it all in context. Working on this mission for 15 years, that's got to be just so satisfying to see how successfully it came down.

Daniel Glavin: Yeah, no doubt. I mean, I'm actually honestly still in disbelief about this whole thing. I was telling people it felt like I was a cast member in a science fiction film. We're really doing this. But now samples are back, we've confirmed, everybody's seen the images of the sample container open. There's clearly Bennu dust in there. And we're getting ready to open it up further here over this next week. But there's sample there. And so this is real. We have this pristine four and a half billion year old asteroid fossil from the early solar system to analyze. It's just incredible.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: This mission has had to leap over so many interesting hurdles just because we're beginning to understand things about asteroids and sample return that we've never really had to encounter before. There was that moment where it was actually trying to grab that sample, the touch and go maneuver. And when I read how close that spacecraft got to literally almost being engulfed by this rubble pile, I was really amazed.

Daniel Glavin: Yeah. I mean, it was scary. And of course because of the time delay, it was I think 18 and a half minutes or something before the signal could come back to let us know that everything worked, everything had already happened by the time we're looking at it. But yeah, I mean we went down and we thought it would be more like a pogo stick kind of thing off a hard surface, and it was more akin to literally like jumping into a plastic ball pit. We sunk into the asteroid and none of the mechanisms, we had a spring that was going to activate, so that would trigger the back away thrusters, none of that went off. So there was no resistance of the asteroid as we plunged the sampler in. And fortunately the code, there was a timer that triggered the back away thrusters and we were able to back away and get out of there. But if that hadn't have gone off, if the thrusters didn't work, like you said, we would've been swallowed up by Bennu. It would've been end of mission. But fortunately, these engineers are incredible, they plan for every contingency and they made it happen.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. And then immediately after that, you get the samples into the actual sample container and it was so much sample, it couldn't even close its mouth. I keep trying to liken it to a game of Chubby Bunny. It ate too many marshmallows and just couldn't keep its mouth shut.

Daniel Glavin: Yeah, we swallowed a lot of Bennu, which was exciting because we got deep and we packed the, we call it the TAGSAM collector full. And that was another really kind of frightening, exciting, I don't know what moment of the mission where we're taking images of the sampler head before it was stowed away and there were particles, Bennu particles coming out. As you mentioned, one of the flaps was jammed open by a small stone. And I think the PI of the mission, Dante Lauretta, said at the time, every single particle coming out is somebody's PhD thesis. And he was right. He kind of put it in perspective, like this is opportunity loss. So that initiated a very accelerated kind of stowage. Originally we had planned to basically extend the arm with a sample in it and spin the spacecraft around like a merry-go-round to make a moment of inertia basically measurement to really precisely determine the mass of the sample in the head. But you don't do that if it's leaking sample.

And so it was within days that we were able to get the thing tucked away, accelerated schedule to get it stowed and safely sealed in the sample return capsule. So good news is we know we didn't lose everything, we know that. We've got, I think the mass estimates were something like 250 grams with an error of like a hundred grams, but we were convinced we met our requirement of 60 grams. Yeah, we'll know soon here, hopefully in the next this week or so what the actual mass was, but there's definitely a sample in this collector.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's got to be really cool for you because I understand that you've just been gearing up to check out these samples for a while. This is your bread and butter. So what are you most excited about finding in these samples?

Daniel Glavin: Yeah, so I mean for my career over the last, I would say 20 years or so, I've been studying organics, organic compounds, the building blocks of life in meteorites, so amino acids that make up all of our proteins and enzymes, nucleobases, these are the components that make up the genetic code in DNA and RNA. And so we've been searching for these building blocks of life in meteorites, basically trying to test this hypothesis that meteorites from asteroids like Bennu could have delivered the seeds of life to the early Earth and maybe other planets which then helped give rise to life. So we're going to be testing that hypothesis in full swing with Bennu for sure. And one of the frustrating things analyzing meteorites is that they've been contaminated. As soon as they hit the atmosphere, they're heated, they're exposed to the atmosphere, they hit dirt or ice or wherever they land on the Earth and immediately start being contaminated by terrestrial organics.

And we don't have that problem with Bennu, especially now after the successful soft landing of the sample return capsule. These samples are going to be very clean. And what that means is if you did start detecting organic compounds, you can really trust the results that these are organics that were formed in space on this asteroid, and it isn't contamination that came into the sample later. So I'm really excited about that, testing again this hypothesis that the prebiotic organic compounds that led to life on Earth and maybe elsewhere like Mars could have come from asteroids like Bennu.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Some of the sample return results have been made public, but I've been told that the really juicy stuff is coming out soon. Danny Glavin will return to the show when he's ready to divulge what they've learned. We'll be right back after this short break.

Bill Nye: Greetings. Bill Nye here. 2024 was another great year for The Planetary Society thanks to support from people like you. This year, we celebrated the natural wonders of space with our Eclipse-O-Rama event in the Texas Hill Country. Hundreds of us, members from around the world gathered to witness totality. We also held a Search for Life Symposium at our headquarters here in Pasadena and had experts come together to share their research and ideas about life in the universe. And finally, after more than 10 years of advocacy efforts, the Europa Clipper mission is launched and on its way to the Jupiter system. With your continued support, we can keep our work going strong into 2025. When you make a gift today, it will be matched up to $100,000 thanks to a special matching challenge from a very generous Planetary Society member. Your contribution, especially when doubled, is critical to expanding our mission. Now is the time to make a difference before years end at planetary.org/planetaryfund. As a supporter of The Planetary Society, you make space exploration a reality. Thank you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: As the OSIRIS-REx team was working to free the samples from the spacecraft, which turned out to be way more complicated than expected, another mission team watched their beloved spacecraft blast off. The Psyche mission left Earth on a course to rendezvous with a potentially metallic asteroid. If you've been a fan of Planetary Radio for a while, you'll probably remember our next guest, Lindy Elkins-Tanton. She's a foundation and regents professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University. She's also the principal investigator for NASA's Psyche mission, which launched on October 13th, 2023. Lindy has shared so much of herself with us over the years, not just detailing the Psyche mission, but about her own life. Her conversation with Planetary Radio's previous host Mat Kaplan about her book, which is called A Portrait of the Scientist as a Young Woman, makes me emotional every time I hear it. But today she's back for a very special reason. After years of tireless effort and passion from her and her team, NASA's Psyche mission is finally in space. It's on its way to explore the metallic asteroid also called Psyche, which might just be the exposed core of a protoplanet from the early solar system. But for Lindy, it's the culmination of so much more. It's the realization of a dream hard won through perseverance and teamwork. Hey, Lindy.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Hey, good to see you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Good to see you again, and thanks for coming back on the show.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Thanks. I really appreciate it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, the last time we talked, I remember saying near the end, after this launch, I wanted to invite you back on because what a moment. You've been working on this for so many years.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Oh my gosh.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How does it feel to finally have your spacecraft out into space?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Beginning to feel like it's a new normal. I had a countdown clock running on my desktop and now it's a count-up clock because it did work that way. I'm beginning to feel like I'm catching up on sleep a bit. The spacecraft is performing so well and we had such a roller coaster of challenges to overcome, including at the last minute before launch. And so this feels like some surreal new kind of world. Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right? What happened on launch day that made that so complicated?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Launch day itself was the most perfect and beautiful launch day ever. But two weeks before launch, we discovered we had a problem with our coal gas thrusters, that they were going to overheat. And this was just a couple of geniuses who I'm indebted to forever at JPL, who just thought, I don't feel totally comfortable with this, let's look into it. And it turned out we had been given the wrong data, which we based all of our operations on for years. And when they took their own data, it was a different story. So suddenly, and this was the day I arrived in Florida thinking I had kind of let my guard down, which is always a mistake. I'd was like, okay, we're just going to coast into launch. It's going to be a series of parties and this amazing experience. And then suddenly it was just like red alert because this could be mission ending. If they overheated, we would no longer be able to turn our spacecraft and we probably would never have known what failed on the thrusters.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What a nightmare.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: A nightmare. So suddenly a hundred, 150 people, all hands on deck, every kind of blaring you could imagine. 2:00 AM I am on WebEx calls with 70 people. And I've just never, honest to God, this was a masterclass in how teams work best because it just could not have been handled better. And found a solution, and we did have to move the launch seven days. Incredible, really solved it, and that was amazing. And then we thought, great, okay, we're going to launch on the 12th. And we get on the weather call, by we, I mean Henry Stone, the project manager and Ben Weiss, the deputy PI, and myself standing outside under the eaves of this building where we're having our team party. We had to go outside to take this call.

The heavens open, its pouring rain, and we're listening on the call and it's the super expert weather person from the Space Force side saying, "It's not looking good for the 12th. We're expecting tornadoes." And we're like, "Of course, of course we're expecting tornadoes. Of course we are." Actually Ben Weiss and I just started cracking up because it just could not have been more perfect. So we were just fated from the beginning to launch on Friday the 13th, and that day was the most perfect launch day ever. So you can imagine the kind of exhaustion and hilarity we were entering into that launch day with.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I hope you still got to have some of your parties though.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: We had the parties anyway because you can't really reorganize. You have whatever, five or 600 people coming and it's just, you're going to have the party anyway, so it's like a prelaunch party. So on launch morning, I got up really early because I got to sit on console. And the console that I got to sit on, there were 10 different rooms of people doing operations for the spacecraft. A bunch of them were at Kennedy Space Center, and then there's the big operations room at Jet Propulsion Laboratory. And we're all on headsets listening to the voice net and we're all watching the consoles. And so my console was in Hangar AE on the Space Force side.

So I get up long before dawn, it's totally pitch black. And come up to the gate to go into the Space Force side and I've got my badge and I'm ready to go in. And there were so many people coming on for launch that they had actually opened two lanes so that we could get onto the base and they're checking all the badges. And then the base and Kennedy are both just miles and miles of swampy Florida wilderness jungle interspersed with occasional gigantic launch complexes, and there's no streetlights. Driving up this two lane road in the absolute pitch dark, and then there's a little lighted sign by the side of the road that just says, go Psyche. There were these wonderful moments. It was a big, big deal. So many people making this happen. And then, I don't know, 10 or 11,000 people came to see the launch as well. So sitting in that console at Hangar AE and listening to the countdown, following it in my launch book, and that was just an amazing experience.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's going to be so cool to see the people locally cheering for your mission. Because I got that sense, I've only been to one launch or rather attempted launch at Kennedy Space Center, but just seeing all of the shop windows with their signs for the missions and all the people showing up, there's something really cool about the community around that space center.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: I love that. And we had so much support for this mission from around the world too. That was just a thrill to know that so many people were participating. So we're going through, and this is a big deal launch for SpaceX because it's their first NASA Deep Space mission launch and just the eighth Falcon Heavy. So they really wanted it to go well. And we had a great working relationship with SpaceX. And so all these teams from different organizations came together into one. And the countdown is going so smoothly and the big higher ups from NASA who were in the room with me were like, this feels good, this is going to happen. And we're going through the book and for a while there's just periods of silence because there's actually no problems and nothing to work and everything's working. And then at 10 minutes before launch after doing the countdown now for hours, suddenly there's a problem. And I wasn't sure, I knew it wasn't good, but I didn't know how bad it was. So I turned to one of the JPL leadership, who was sitting to my left, and he just swore, which he never does. And then I thought, oh my gosh. And so we all had collective, like 500 people had a heart attack for two minutes until it was resolved at launch minus eight minutes. And then it proceeded.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What a rollercoaster.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Oh my gosh. Right. I mean, it was good to just be afraid for a minute because things were going very smoothly. And then the rocket worked perfectly. And as soon as it was launched, we all ran out of the building and just watched it with our eyes. And we looked up in the sky and we saw the rocket and we watched the boosters separate, and then we watched them land. And they're very close to us over there at Hangar AE, and the sonic booms and the rumbling crackling sonic booms that are just, I love that. People get excited about Formula One race cars, but let me tell you, go to a Falcon Heavy launch and then there's no going back.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I would love to.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: It's just amazing. And then had to figure out how to drive myself over to the press center because I and some of the JPL management and our project manager, our deputy principal investigator, all these people were, like 10 of us are supposed to meet at this conference room in the press center because they don't want us to meet any press until we've reached mission success, which is that we've got telemetry and we're locked on and the solar panels are power positive and we're thermally stable. These are a bunch of things that are, we don't even separate from the rocket till 62 minutes after launch. And it could be even another two hours before those things are accomplished. So we don't want any confusing partial messages. And so I had to figure out how to drive over there through the 500 cars that were leaving from all the people watching on the causeway and stuff, but it was very well done. And I just took out my cell phone and hit record for one of these voice memos and just kind of poured out everything that I was feeling at that moment, which I haven't listened to again yet. I got to figure, I don't know what I said. So that'll be interesting.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's a beautiful thing to record and keep. You'll get to reflect on that moment in the future. And our listeners have been on this journey with you for literally years, not just about the Psyche mission, but about your personal life, your personal journey, everything you've overcome. So seeing you in this moment and knowing that you have that record, I feel like that's so special and you're going to have to listen to it at some point.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: No, I am. And I've been also keeping a notebook because I knew I wouldn't remember all the incredible things that happened during the super intense insane month that I was living in Florida. And my husband moved down with me. He's like, "You're going to need me to grocery shop. This is going to be great." And so we supported each other. We were each having work stuff going on. And we had a little Airbnb with a pond behind it, and we could kayak through the mangroves. I mean, it was just so many things. I wrote almost like 70 pages of all of these experiences because I do, I feel that. And also like I wrote about in my memoir, there was a moment right during step one where I had cancer and I had to go through chemotherapy and I had a huge amount of nerve damage, and for a while I was even having trouble walking and I huge muscle spasms and my body not working. And so now, not only has my rocket launched, which is amazing, but in the past year, I've actually totally regained my health. And so I now am pain-free and I can jog and it's amazing. So it's like this stellar moment. I just turned 58, which I fricking can't believe, but I'm feeling like, this is a really good moment, so I can't forget about it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: This seems like a book all on its own.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: I feel like it could be. I don't know. It's an intense emotional experience, that's for sure. Yeah, so we show up at the press center and we had to sneak around the back and come in this secret door so we could end up in this closed conference room and not run into all the press in the front. And so we're all in there and a couple of the guys have hooked into the Psyche ops and they're getting the data down and they're like, wait, we're power positive. We're like, wait a minute. We all watch, first we all watched the separation on the screen and everybody could see that. It was broadcast via SpaceX's onboard cameras to everybody in the world, and you can watch it on the replay of the launch commentary. And we'd ask them to give us no angular momentum, no spin at tip-off. We wanted the spacecraft to be going absolutely straight with no spin so that we could right away get down to opening the solar arrays.

And we all watched and we're like, our heads are tipping, "Is it spinning? Is it rotating?" But it wasn't. It was just perfect. It just soared away. And we knew there was some chances that the low gain antennas would get picked up by the Deep Space Network. And suddenly we're like, "Oh my gosh, that was a little bit of telemetry. Wait a minute, what are we getting?" And then the solar arrays deployed. We're getting power. The spacecraft detumbles, it uses those coal gas thrusters, it all works. The coal gas thrusters are not overheating. We couldn't even believe it. They were so cool and perfect. And so then the head of the press group, this wonderful woman from JPL, she's used to there being contingencies like anomalies and issues after launch, and she didn't want us to have to be solving them well hangry after being on console for like five, six hours.

And so she went out to get us sandwiches thinking it was going to be hours more. And while she was gone, we hit all of the things needed for mission success. And so we locked on, we had telemetry, the spacecraft was healthy, it was thermally stable, it was power positive. She came back with the sandwiches and we're like, yay.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Victory sandwich.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Yeah. We couldn't even believe. We kept looking at each other and going like, pinch me, I can't believe how well this is going. And then we took a million loopy pictures. And that was launch day. It was amazing.

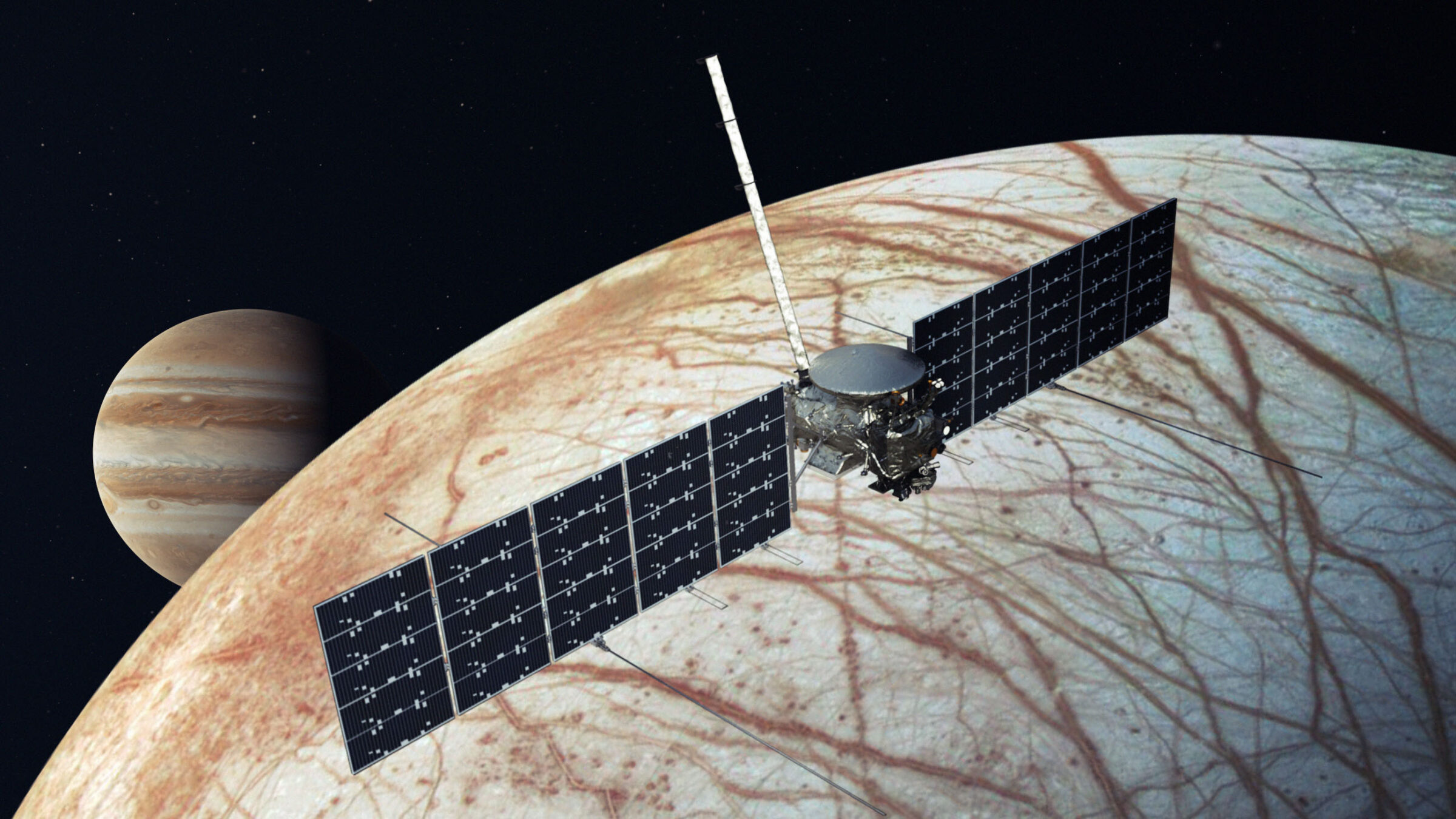

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I hope so much that the Psyche mission images are as weird and beautiful as I imagine. If anything were to inspire the next generation of people who want to empower human space exploration by gathering resources on asteroids, it would be those pictures. Well, that and NASA's Lucy mission, which is on its way to Jupiter's Trojan asteroids, and the United Arab Emirates' upcoming mission to the asteroid belt. But of all of the fantastic missions to launch in the past years, the one that I was most looking forward to was the launch of Europa Clipper. I want to know whether or not there's life off of Earth, and Europa Clipper might be key to that journey. The spacecraft blasted off on October 14th, 2024 after a nail-biting brush with Hurricane Milton in Florida.

Europa Clipper is the first dedicated mission to explore a world with a global ocean other than Earth. While it won't be detecting life directly, it's going to perform a bunch of close flybys of Europa. That'll teach us more about its icy shell, its ocean, the composition, and its geology. It's the largest spacecraft that NASA has ever built for a planetary mission, and it was produced as a partnership between the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. It has been a colossal effort on the part of thousands of people to make this mission possible, from the planetary scientists who made it a priority in the Planetary Science Decadal Survey not once, but twice, to the advocates who got the mission, the funding it deserves, and of course the scientists and engineers that had to do the hard work to actually put together this beloved spacecraft.

After all of this effort, the mission team and space fans gathered in Florida to see the spacecraft off. Unfortunately, all of that got waylaid by Mother Nature herself. Hurricane Milton, which was a massive category five hurricane at one point, had Kennedy Space Center and all of its launch facilities in its sights. Bob Pappalardo, who's a great friend of the show and project scientist for Europa Clipper at JPL, joined me over the weekend. He told me all about how his team weathered the storm and launched this historic mission to Europa. Hey, Bob. Congratulations.

Bob Pappalardo: Thank you. Thank you. Quite a week it was.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Really though. And not just a week, it has been a saga since we last spoke a few months back. And then so many things happened that put this launch in this kind of limbo for a while. So I'm sure it's really relieving now that it's out there in space on its way to Jupiter.

Bob Pappalardo: Yeah. It seemed like our spacecraft didn't want to leave us.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How long have you been working on the spacecraft? It's been so long.

Bob Pappalardo: Well, the mission got started in 2015. Building of the spacecraft itself and integration of the instruments, probably a few years now.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've kind of covered the saga over the last few weeks. First there was the issue with the SpaceX launch vehicle. You ended up going up on a Falcon Heavy, but the Falcon 9 had an issue right off the bat. So right there, we had to wait for the FAA. And then here comes Hurricane Milton to make it even more intense. I know that you and a lot of your colleagues planned to be out there. What was that like when you heard the hurricane was oncoming? And did you guys all have to leave?

Bob Pappalardo: Well, it was pretty tough. At first, everything seemed fine. I first got out there for a flight readiness review, and I got to see the encapsulated Clipper in its fairing roll out of the clean room where it had been worked on and the solar arrays were incorporated. That was quite celebratory. And I remember getting an email or something from a team member, it said, "Oh, it's supposed to be rainy next week." I'm like, "Rainy?" Because we hadn't heard that at our flight readiness review. And then, yeah, people started talking about this storm brewing in the Gulf or the conditions being right for a storm to brew in the Gulf and possibly hurricane. And as time went by, yeah, that became a hurricane that was targeting KSC. And we had a team meeting planned, science team meeting, most of the week as well. So we had planned alternate versions of our science team meeting if the launch didn't come off on the day planned. We didn't plan for a hurricane, but we had the flexibility to move things around.

And then as the forecasts were getting worse and worse, we had discussion of what to do about the science team meeting. There were already a lot of people there. We said, okay, we're going to assume people aren't going to continue to come to our meeting and said so to folks. But the people who were there, I said, yeah, we'd still like to, even if this is a hybrid meeting, we'd still like to be in person. We met the first day and everything was fine on Tuesday of last week. But then it was clearly going to be a big storm the next day and we canceled. And then the storm was slowing down, so we canceled for Thursday. And a lot of people were just gathering and having a good time in the hotel. We showed movies on the screen because there are a lot of kids there, a lot of families.

I like to put everything in terms of Star Trek analogies. So I wasn't used to being on the Enterprise D at our team meeting where we had the families there as well. So it was actually I think prior day where a colleague called and said, "You know there's a chance you're going to be in the front right quadrant of a hurricane." I'm like, "Yeah." "Well, that's the quadrant that spawns tornadoes." And there was no talk of tornadoes on the news. I was watching very carefully and keeping up with all of the emergency info. And then Wednesday afternoon, the tornado warnings started coming and creeping up from the south toward us. So I went downstairs, make sure everything's good, and again, people are playing games and talking and watching movies in the ballroom. And I asked the hotel staff, "Where's the right place to be in case of tornadoes? Is it the ballroom, is it inner building or a stairwell?" And so then when all the warnings went off on people's phones, calmly asked people to please come into the ballroom. And everyone was now in there who was downstairs. And then the palm trees outside started blowing sideways and it was getting darker and darker. The hotel staff's like, "Inside, inside." And we learned that evening that the bank building across the street had its roof blown off.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh my gosh.

Bob Pappalardo: And part of the parking garage metal between our building and the next was tossed around and light poles. And it wasn't until a couple of days later, I learned that indeed our hotel had been nipped and had some damage as well. So that was nerve-racking. Power went out that night and we ended up moving everyone to another hotel, same brand, not far away on Thursday when things quieted down. And our whole meeting moved as well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. Oh my gosh.

Bob Pappalardo: We picked up again on Friday and had some good conversations, but it was pretty nerve-racking. And then the weather cleared and the reviews picked up again. And our project manager mentioned, yeah, sometimes after, most of the time after a hurricane, the weather can be really clear and beautiful, and it was. And we ended up with a perfect launch day on Monday.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That is such an emotional whirlwind right there. I mean, you already had so much on your plate just with this mission, and now you're in this scenario where you're responsible for making sure all these families are okay in this scenario, trying to keep it together in the middle of tornadoes and hurricanes. My gosh, it must have been such a weird kind of whiplash moment to finally have the clear skies and have that catharsis of actually seeing it launch after all of this tension.

Bob Pappalardo: Yeah, yeah, it was incredible. I'd seen a couple of small launches. Well, I saw a small launch and then I felt a small launch up here at Vandenberg because it launched in the fog, and this was different. Yeah, we gathered in kind of VIP area and much of the team was out in the stands there watching the event. And it was more than I had imagined. Things quieted down as the final countdown occurred. And we watched and people cheered. And then when the roar, the shock wave hit, and the light was as bright as burning magnesium, you couldn't even look at it, it changed my impression of this. There was so much power in that launch, it just became something different. It was almost as much of a spectacle as seeing a solar eclipse where it's like, oh my God, what is happening here? We are tossing this thing off of our planet with this enormous Falcon Heavy rocket. It was just more than I can express. And people were quiet and just mouthing, oh my God, all around. It was something to experience.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: There are some moments that you can try to prepare yourself for emotionally, but until you're standing in it, there's really no way to convey what that's like. And I've never seen a Falcon Heavy myself, but after speaking with my co-workers about their impressions of it during the LightSail 2 launch, I mean, you can tell that it changed them and their entire perception of what we're doing here trying to do space exploration. It really gets to the visceral nature. We're literally strapping some of the greatest hopes of humanity onto a controlled bomb and firing it off of our planet.

Bob Pappalardo: And of course leading up to that and seeing the rocket the prior day, there was a feeling of pride and excitement. And that night, the night before the launch, we had a big family and friends event. And Ada Limon, the US Poet Laureate, read her poem for Europa, and it was wonderful. She was there at the launch as well. But yeah, I feel like nothing could have really prepared me, but not just for the emotion of seeing this craft that we had spent years and years and had concepts going back 25 or more years actually launch, but the power involved in that launch being just so overwhelming. Yeah, it was something

Sarah Al-Ahmed: After a lifetime of loving and studying space, I do not have words to describe what it's like to meet all of these amazing space people. When I became the host of Planetary Radio, Mat Kaplan, who is the creator and former host of this show, told me that this was my chance to meet my space heroes, and it turned out to be true. I've met so many people that I looked up to, and there are a bunch of adventures left to come. Of course, despite my almost two years on this show, there is another person who wins the award for the most appearances on Planetary Radio. I'm not even number two, that award goes to Mat. But number one is held by our chief scientist, Dr. Bruce Betts. Bruce has been featured in every show for the last 22 years. We turn to him next for What's Up. Hey, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Happy 100, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Thank you. Although it's an interesting thing coming from you. You've been at this so much longer than me. You've been on over 1,100 episodes at this point.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. That's really, really, really odd.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Isn't it?

Bruce Betts: And wonderful.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What was your experience in the first days doing What's Up with Mat back in the day?

Bruce Betts: I was pleased to be doing a show and doing it with Mat, who I didn't know very well at the time. Now we both know each other better than we want to. And basically what I was presenting, particularly at that time and ever since, were things that I had done from before I joined The Planetary Society, these random space facts and I used to do trivia and what's going on in the sky. So I had the concept, but I'd done it on a phone answering machine, yes, that's how far back my idea goes, where people could call in for weekly things. But the ability to get it on out and to radio was the main focus at that time. Starting on the UC Irvine campus radio station is where it all started, Mat being an alum, later one of my sons being an alum, but unrelated. Anyway, that's when I first started babbling, and obviously I continued to babble. How was your hundred episodes? It doesn't seem like we've done a hundred episodes, but then I have a bad perception of time.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, it's not the weird thing. I mean, I know I keep making all these jokes in my personal life about time being relative. And I've gone on some weird adventures since I started this. And as I was kind of putting together this episode and trying to reflect on two years of doing this show almost.

Bruce Betts: Earth years, I mean.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Earth years, fair.

Bruce Betts: Okay.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. When I hit one year on Saturn, then we know it's big time. But really though, the wacky adventures that I'd almost forgotten I got to go on because there's just been so much continuous awesome doing this job, it's been really cool having a moment to just kind of sit down and look back on all of that.

Bruce Betts: That's neat.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. I've done some wacky things, although less so recently, I've lulled in my middle age. Although Mat did get me run over by a rover at one time.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What do you mean you got run over by a rover? What does that even mean?

Bruce Betts: We were at a convention conference thing and they had some models, small rovers that they were driving. And they drove them over Mat and I lying on the ground was some classic images.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I mean, as long as you didn't get hurt, it's all fun and games until someone gets destroyed by a rover wheel.

Bruce Betts: It's all fun and games till you get crushed by a rover wheel.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right? Yeah. None of those adventures just yet, but I mean I've gotten to go to JPL, I've gotten to see cool rocket launches, I've spoken with some scientists in these intense moments in their lives where they've just seen their spacecraft return or just launch. It is just such a privilege to be in a space where I can talk to people at these moments. And I'm sure years later, we'll be able to look back on all this and it'll be cool to have.

Bruce Betts: It's been a privilege working with you and you've done fine job bringing that sense of excitement and thrills and enthusiasm to the world and about other worlds.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Happy to be the sunflower to your Eeyore.

Bruce Betts: You know, if people like Mat and you in your own different ways weren't such sunflowers, I wouldn't have to be Eeyore so much.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Truth. Well, here's to our next 100 episodes, Bruce. Hopefully we'll be doing this for a while.

Bruce Betts: Party on.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Party on.

Bruce Betts: Well, unless you're cutting me off in the next hundred, let me go ahead and present something.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Let's do it.

Bruce Betts: All right. Random space fact for Sarah. This is for everyone, but I dedicate this one to you, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Thank you.

Bruce Betts: I was thinking, I was thinking where is the hottest place in the solar system if you ignore that sun thing? And then things tightly influenced up close and personal, corona of the sun. Some people, the usual question you get like, oh, surface of Venus. But no, it's the cores of those pesky planets. And the bigger your planet, the more you can heat up that core. So Jupiter, hottest place in the solar system. You're never going to get there. Besides the sun and related things. I mean the estimates are pretty broad because oddly enough, it's hard to measure, but ballpark 25,000 Kelvins, 44, 45,000 Fahrenheit, 25, and basically the same Celsius because no one cares about 273 degrees once you reach the 25,000. But it's hot down there. A lot of it also very weird left over from in original formation and gravitational collapse of the planet and converting to heat energy and also from other things. But we at least think, the models say it's hot down there. Jupiter does give off I think like one and a half times more energy than it receives from the sun.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That is a wild number.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, it's-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But really cool. I mean, it makes sense, especially in the context of all those conversations I've had with people studying data about the moons of Jupiter. Just the idea that Jupiter itself was so bright it might've impacted the way that some of these moons formed is so cool.

Bruce Betts: It's a big one. I don't know whether you know that, but I'm a professional. Trust me, it's big.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But trying to do that kind of calculation where you're trying to figure out how warm the inside of a planet or a star is, knowing that we're never going to be able to drill down in there, there is so much that goes into that calculation.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, it's cool. I mean, yeah, I guess so.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Or I guess technically it's hot. Ba dum tss.

Bruce Betts: Ba dum tss. Okay. That was so great. We should finish with that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know, right? A hundred episodes, I'm out of jokes. Let's do this.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody, go out there and look up in the night sky and think about your favorite joke you've heard Sarah tell on Planetary Radio. Thank you. Good night.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with a special collaboration. We'll share Neil deGrasse Tyson's StarTalk interview with The Planetary Society's CEO, Bill Nye the Science Guy. Thank you so much for coming on this journey with us to learn more about the cosmos and our place within it. We can only do this show and all of our advocacy work because of your support and passion for space exploration. Thanks for making my first 100 episodes so special. If you love the show, you can get Planetary Radio T-shirts at planetary.org/shop, along with lots of other cool spacey merchandise. Help others discover the passion, beauty, and joy of space science and exploration by leaving a review or a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day, but helps other curious minds find their place in space through Planetary Radio.

You can also send us your space thoughts, questions, and poetry at our email at [email protected]. Or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the Planetary Radio space in our member community app. Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by our members from all over this beautiful planet. You can join us and help support space missions all around the world at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor. Special thanks to Andy for everything he's done to make this show sparkle. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. And until next week, ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth