Planetary Radio • Jun 12, 2024

The nova and the naming contest

On This Episode

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

Asa Stahl

Science Editor for The Planetary Society

Latif Nasser

Co-host of Radiolab

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

Last week was a big one for commercial space. Our senior communications advisor, Mat Kaplan, discusses the first crewed Boeing Starliner test and SpaceX Starship launch. Then Asa Stahl, our science editor, lets you know how to observe the upcoming nova in Corona Borealis. RadioLab's Latif Nasser returns to Planetary Radio with a new public naming contest for a quasi-moon of Earth. Then, we dive into some naming conventions for space objects in What's Up with our chief scientist, Bruce Betts.

Related Links

- NASA Broadcast: NASA’s Boeing Starliner Crew Flight Test Launch

- Everyday Astronaut: Starship Flight 4

- How to see the nova (“new star”) in Corona Borealis

- Earth’s quasi-moons, minimoons, and ghost moons

- What is Venus' quasi-moon Zoozve?

- Planetary Radio: Radiolab helps name a quasi-moon of Venus

- Radiolab’s naming contest for a quasi-moon of Earth

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Starship, Starliner, a nova, and a naming contest, this week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society, with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. Last week was a big one for commercial space. Our senior communications advisor, Mat Kaplan, kicks off this week's show with the successful launches of the Boeing Starliner and SpaceX's Starship. Then Asa Stahl, our science editor, lets you know how you can observe the upcoming nova in Corona Borealis. You may remember a few months ago when Radiolab's Latif Nasser joined us to discuss the hilarious tale of the naming of Venus's quasi-moon Zoozve. He's back with a new public naming contest for a quirky quasi-moon of Earth. Then we'll dive into some of the weird naming conventions for space objects in What's Up with our chief scientist, Bruce Betts. If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit the subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it. Speaking of knowing our place in space, one of the greatest mysteries facing humanity is whether there's life beyond our planet. Next week, The Planetary Society is launching a new class for our members in our community app on the search for life. I'm looking forward to taking that class myself. Also, Accidental Astronomy by our guest last week, Chris Lintott, just came out. If you read the book, I'd love to hear about your favorite accidental space discovery. Now let's get into it. Last week we witnessed the first crewed flight test mission launch of the Boeing Starliner, and the fourth launch of SpaceX's Starship, this time without any explosions. The Starliner safely carried NASA astronauts, Sunita Williams and Butch Wilmore, to the International Space Station. A day later, SpaceX's Starship, which is the most powerful rocket ever built, completed its test. We also have an update on the dearMoon mission, a privately funded space project led by Japanese entrepreneur Yusaku Maezawa. It aimed to take artists and other influencers on a trip around the moon aboard SpaceX's Starship. But the mission has now been canceled. Here's our senior communications advisor and the creator of Planetary Radio, Mat Kaplan, with the details. Hey, Mat, welcome back onto the show.

Mat Kaplan: Always a pleasure, Sarah, especially after a day like we had yesterday in space development.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, it has been an exciting and harrowing week for space flights.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But let's start with the first crewed flight test mission for the Boeing Starliner. That happened on Wednesday, June 5th. Gosh, we crammed so much into this week. But it's been a long road for Starliner. It took a lot longer to develop than we anticipated, and now we're finally seeing people launch to the ISS on that. How did the launch go?

Mat Kaplan: Beautiful. Really good to watch. A little scary because I kind of thought there ought to be... If it was me, I'll do one more uncrewed test. But what the heck? They had confidence, and their confidence was proven out. I could not believe... Have you seen the video of Suni Williams, Sunita Williams, coming through the hatch into the International Space Station? She does the greatest space dance ever just after coming through the hatch, and you know why? It's because these two people, she and Butch Wilmore, they've been waiting years for this, training and training and working with Boeing and others, and finally they get to do the mission. And it was looking a little hairy right up to the end there. I mean, they were like 200 yards or 200 meters away from Space Station and they ran into these problems with thrusters, five different thrusters, and on top of that, helium leaks, which they'd already been having trouble with. They were able to get four of the five funky thrusters working properly, and it looks like maybe it was a software problem. But listen, it worked out and they're there, and they're going to be there for a week.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Anytime there's an occasion to dance on the ISS is good. But after that kind of ride, that kind of nail-biting situation, it took them several extra hours to actually dock with the ISS because of these issues. I mean, just imagine if something went horribly wrong. We are so lucky that no one has gotten lost in space yet.

Mat Kaplan: Not yet. Not yet. Now the big chest, of course, is reentry. That's where we do sometimes run into tragedies. But we'll trust that they've got that all worked out as well, I hope. Anyway, it was fun to see the homecoming because both of them have spent so much time in the International Space Station, and it looked like they were pretty happy to be back.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, let's listen to a little bit of their joy as they got onto the Space Station. We've got these wonderful clips that you pulled for us. Thanks, Mat.

Speaker 3: Lots of cheering here in the room. Big hugs. Suni Williams coming through in her blue flight suit, and followed surely behind by Commander of Starliner Butch Wilmore, now back on the Space Station, the third visit for both astronauts and the first crewed flight test of the Starliner spacecraft. Everyone looking very happy, like they had a great ride.

Speaker 4: Congratulations to all of the NASA and Boeing teams on this incredible milestone. Butch and Suni, the ISS Flight Control Team is thrilled to see you back on the ISS. Station, please begin your remarks.

Oleg Kononenko: Butch and Suni, we are glad to see them all here in the International Space Station. And we want to congratulate the whole team in different mission control center for launch, for docking, and [inaudible 00:06:02]. We are very happy.

Butch Wilmore: Yes. Indeed. Yeah, we are thrilled as well. I'm not sure we could have gotten a better welcome. I mean, we had music, we had... Matt was dancing. It was great. What a wonderful place to be. Great to be back here. It feels like... I mean, obviously, Suni and I have been gone for a little while, but it's very familiar. There's only one problem. Matt is in my crew quarters. So I don't know what we're going to do about that. But hey, thank you all for the great welcome. And thanks to ULA, got us going. Boeing kept us going. Mission control MO kept us going and got us here. What a great, wonderful team effort. I mean, team, team, team. These organizations are the epitome of teamwork, and it is a blessing and it's a privilege to be a part of it. It's just amazing.

Sunita Williams: Yeah. And I just want to say a big thanks to family and friends who've lived this for a long time. I think you're glad we're not with you anymore. And we have another family up here, which is just awesome. Like Butch said, it was such a great welcome, little dance party, and that's the way to get things going. We are just happy as can be to be up in space, one in Starliner on an Atlas V, and then here on the International Space Station. It just doesn't get much better.

Butch Wilmore: Hear, hear. Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So because of this moment of tension, I actually tuned in to the docking. I don't always actually watch the live streams of the dockings because they take a little while to do. But this was actually a fully automated docking, although the people operating Starliner actually did take manual control of parts of this journey. But this was an interesting thing to watch.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Butch Wilmore got to do a planned manual test before they docked. But the docking itself, it was absolutely fascinating to watch because you could see the AI basically doing pattern matching with the ISS to align the Starliner, the CST-100, properly with that hatch, and it appeared to work perfectly. So kudos to Boeing and their subcontractors in NASA for that as well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It was cool to watch for parts of it in darkness. There were moments that I think a human would have trouble as that spacecraft was in darkness before it came back into light. It takes the ISS about 90 minutes to go around the Earth, so you get about 45 minutes a daylight, about 45 minutes of nighttime. And in this case, they had some sensors that were looking in parts of the spectrum that humans can't actually see. So giving that data to an autonomous system I think is a great way for us to, in the future, make sure that these docking attempts are a lot more safe and a lot more speedy.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely. Self-driving space capsules today, maybe they'll get self-driving cars right someday.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I mean, unfortunately, there's a lot of things to crash into down here on Earth. A little more space out there in space.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But all right, so Starliner went really well. Really glad to see that finally going on. Do we know what's going to be coming up next for Starliner?

Mat Kaplan: Well, more testing, a few more wrinkles to get out. But Boeing has this contract much as SpaceX has had for years for the Dragon to carry crews, quite a few people. Stuff them all into that Starliner and bring them up for a nice long stay on the International Space Station. That's what it was designed for. Interesting sidelight, they were bringing cargo up on this mission as well, and they had to leave behind some of Butch and Suni's luggage because there was a plumbing problem on the ISS. So there was a last minute substitution of more parts for the toilet, I believe, and that is the great advantage of being close by and having this easily available transportation up to the ISS. That's going to be a little more difficult if the toilet breaks on the way to Mars.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh my gosh, can you even imagine? I remember them putting that out in A City on Mars, that book, what happens when the toilet breaks on the way to Mars?

Mat Kaplan: Everybody dies.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Everybody dies. Well, all right, let's move on to SpaceX's Starship. We've seen several attempts at these launch tests, many of them ending up in some really spectacular explosions. But this one actually went really well.

Mat Kaplan: Oh man, it was so spectacular. I mean, I'm sorry to make the Starliner take the second seat to Starship. But you have to say, biggest, most powerful rocket ever, and it did pretty much everything they wanted it to do. You could just share in the enthusiasm, the excitement from the SpaceX team and Hawthorne. It was such a pleasure to hear them cheering at every little thing that went right, and just about everything went right, and there were so many wonderful moments. I mean, as the Starliner was returning, and of course, superheating through the atmosphere, and you could see the plasma forming around Starship. You started to see that fin that the camera was mounted just above, start to melt and fall apart. And finally, the lens breaks on the camera. You watch it go snap. And they still had a picture all the way down to the ocean and were able to slow themselves. They were never planning to recover these either the super heavy booster or this Starliner. They were supposed to come down in the ocean. And they did, right over the Indian Ocean, which, by the way, that's where the docking took place at the ISS for Starliner right over the Indian Ocean. So hot place to be if you were a space fan yesterday. There were such great moments. Whatever you think of Elon, it was absolutely charming to see him sitting in mission control with one of his kids, one of his small children in his lap, and then to see the little boy clapping when they made it. I was also very touched that they ran, when the anchor people weren't talking during the lulls and the mission narration, they played The Blue Danube, which of course, anybody who's ever seen 2001, A Space Odyssey, that made The Blue Danube always one of my favorite pieces of music. And what a great commercial for Starlink since they had four Starlink transceivers mounted on the outside of Starship, and that's how we were able to get this amazing video. I got to tell you, there's one more that was just so great. I had this book club, Planetary Society member community book club, conversation with Bob Zubrin, Robert Zubrin, who is very excited about Starship. It's all over his new book. And he said yes, he was watching. I said, "Did you catch the line from one of the anchors? We designed Starship to land on Mars where there are no runways." So there it is. That's the ultimate dream of SpaceX and a lot of the rest of us as well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Honestly, I'm surprised I couldn't hear the people over in Hawthorne partying from here, because watching that live stream was wild.

Mat Kaplan: It really was. Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Here, let's listen to a little bit of the audio from what happened over there at SpaceX that day.

Speaker 9: All right. 30 seconds into flight, the rumbles are still building here in the Raptors Nest. We're seeing 32 out 33 engines lit on the super heavy right now. Kate, we've got a booster on the way back to the Gulf at a ship on the way to space.

Speaker 10: These views have been looking incredible, super heavy, has been performing beautifully today, and you can hear the crowd is very excited about it. As a reminder for booster, the primary goal today is to do a landing burn and a splash down in the water. And you can see those grid fins on your left hand screen rotating and turning to guide the booster. And there's that landing burn. That landing burn has begun and you can see the water below. And we have splash down. What an incredible sight. Congratulations to the SpaceX team.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's really fascinating to see this new dawn of the age of commercial spacecraft. And of course, commercial partnerships have been a part of efforts to go to space since the very beginning. But it feels like we're at the beginning of something very new. And I think about that child sitting on Elon's lap, what this must be like for this new generation. So many rockets going to space. We've had some successes, and I'm happy for that. But there is one sad SpaceX related story I do want to give an update on, which is the dearMoon mission.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Isn't that sad? I mean, especially for that group of regular folks, more or less regular folks, who were expecting to make a trip around the moon, thanks to Yusaku Maezawa's plans to basically buy a Starship mission and make that loop around the moon. I mean, they even included our good friend, Tim Dodd, the Everyday Astronaut. These folks were not given any clue ahead of time by Maezawa that he decided to cancel. I mean, I can kind of understand his thinking. He was hoping to do it by 2023. He said he didn't want to leave everybody hanging, but still. I mean, what a missed opportunity. And wouldn't this have been a terrific thing just culturally for those of us who believe in space exploration to see these folks, including artists and people in other professions, make this trip that, in the past, only 12 human beings have ever made and they were all highly trained astronauts? I hope that this is something that will happen again sometime. I don't think I said Tim Dodd actually said afterward he was extremely disappointed. I slowly allowed myself to envision a trip to the moon one little bit by little bit. Hey, Tim, I hope you get another opportunity, and frankly, I hope I do too.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Same. I mean, I know that commercial space is complicated for a lot of people. Just think about the fact that for a moment there, these artists and other luminaries were given this potential opportunity, and that just speaks to the future of what might be coming up for us. This opportunity might be extended to so many more people because of these commercial space flights. So I'm really hoping one of these days we get a new dearMoon iteration because it would be a really beautiful thing for humanity, not just to have missions to the moon for the scientific opportunity, but just for our own betterment and the art and the beauty and the overview effect that comes from it.

Mat Kaplan: As our boss, the science guy says, space brings out the best in us and it brings us together. I think it's a safe bet, Sarah. We're going to get there. I certainly hope I get there, and at least as a witness, if not a participant. And I suspect you'll be up there someday too.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh, let's go toast together around the moon, Mat.

Mat Kaplan: Please, yeah. Some of that... How about toasting a marshmallow like they did at the end of the Starship flight using a torch in the shape of a Starship? Classy move.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I actually made s'mores last night because of that.

Mat Kaplan: Excellent.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks so much for the update, Mat, and I'm looking forward to seeing what happens with both of these spacecraft in the future.

Mat Kaplan: You bet, Sarah. Me too, and great talking to you as always.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Sometime between now and the end of the year, a giant stellar explosion will probably pop off in the night sky. This nova in the star system T. Coronae Borealis is suspected to shine so brightly that it'll be visible even in major cities. It doesn't pose a danger to us, so no worries, but the observing is going to be fantastic. Our science editor, Dr. Asa Stahl, recently wrote an article on this subject that's available on The Planetary Society's website. Here's how you can look for the nova too. Hey, Asa.

Asa Stahl: Hey, how's it going? Happy to be here.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Good to have you back on. I've been seeing so many articles coming through my feed, including yours, about the upcoming nova in Corona Borealis. Why is the astronomical community so excited about this?

Asa Stahl: Oh, a bunch of different reasons. I think it's a relatively rare opportunity when you have an astronomical event that is dramatic in itself and then also directly accessible to almost everyone on Earth. I mean, this thing is going to be visible from the hearts of major cities that are heavily light polluted, and it's going to be visible from all the Northern Hemisphere and most of the Southern Hemisphere. So everyone is going to look up and be able to see this, what looks like a new star in the night sky. So it helps to look beforehand and be like, "There wasn't a star there before and now there is." But even if you don't do that, you'll still be able to look up and see a light and know that that is the effect of a giant stellar explosion happening hundreds of light years away, that these sorts of huge concepts of astrophysics, these crazy mind-boggling scale of physics, and then have it just be visible to know that you can look up and see that right now. And then also, scientifically, it's a buffet, right? It's like a smorgasbord of cool stuff that we can see. The last time that this nova went off was in 1946. And at that point, we didn't have any gamma-ray telescopes. And now James Webb is going to be able to look at it, Hubble is going to be able to look at it, lots of ground-based telescopes going to be looking at it, and the amateur astronomers are going to be able to look at it. Amateur astronomers are part of how we even knew that it was going to be erupting soon. So there's going to be a lot of cool science that comes out of it, and hopefully a lot of cool science communication.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And to be clear, this isn't a supernova. This isn't the death of a giant star, this is a nova. How are they fundamentally different?

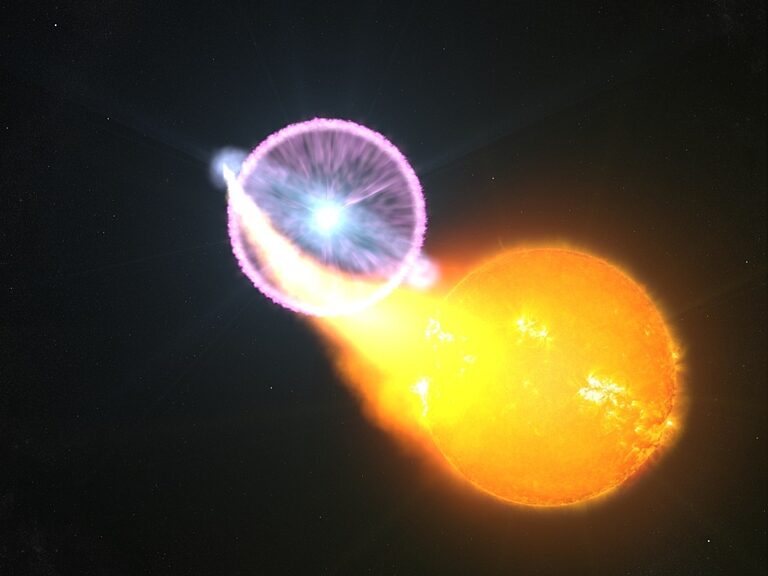

Asa Stahl: Yes, that's an excellent point. It is not a supernova. A nova is kind of like a mini supernova, but there are some key distinctions to draw. A nova happens in a binary star system where you have one star, which is a white dwarf. A white dwarf is a stellar remnant. The Sun will eventually become a white dwarf when it runs out of most of its hydrogen fuel and collapses under its own gravity. Instead of being supported by the pressure from nuclear fusion, it will be supported by electron degeneracy pressure, which is the quantum mechanical effect. If you have a white dwarf orbiting around another star, in this case with T. Coronae Borealis, it's a white dwarf, and the red giant, which is also an evolutionary stage that the Sun would go through on its way to becoming a white dwarf. Then this red giant and white dwarf orbiting relatively close to each other. The red giant is huge, and material from the outer atmosphere of that red giant is being siphoned off onto the white dwarf. And eventually, enough hydrogen fuel piles onto the white dwarf and gets hot enough that suddenly ignites all at once and burns up in this huge flash. That's essentially the same physics as like a hydrogen bomb. And that will release about as much energy as the Sun releases over an entire year, times like 10,000 in days. Whereas a supernova would unleash potentially the entire amount of energy that the Sun will release in its main sequence lifetime, in its sort of bulk lifetime. When it is fusing hydrogen, a supernova releases all that energy at once. So a supernova is even 10,000 times more energetic than your typical nova. It's even crazy bigger. And also, supernovas are a lot more rare. The last supernova happened in the galaxy was hundreds of years ago, whereas novas happened in the galaxy, not infrequently, but a really bright nova like this one is rare. The last nova that was this bright visible from Earth was about 50 years ago. So it's still a rare opportunity. This system also in particular is pretty bright even when it's not nova. So it's the most observed nova in the night sky. On average, it's been observed once every six hours since it's outburst in 1946, which is crazy. You can think of the huge crowd of amateur astronomers all around the world who have looked up and observed this at one point or another to sort of contribute to our understanding of it. It's pretty cool.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How do we know that it's supposed to be going off by the end of this year? How do you predict something like that?

Asa Stahl: It's largely in part to how well it's been observed previously that the sort of pattern of brightness changes before the outburst. And about eight years before the outburst in 1946, that brightness changed. And about eight years ago in 2014, 2015, astronomers noticed, using a mix of professional and citizen science astronomy data, that it was entering into the same sort of behavior and brightness. And then we're predicting that sometime in 2020s it would burst. And now as we're getting closer and closer, they're narrowing down that time range better and better. So it seems like the forecast now is about a 70% chance of an explosion by September and about a 95% chance of it happening by the end of the year. But nothing's for sure, those are just probabilities, and that's just essentially one study. Not too many people look at these things in this much detail and actually make quantitative predictions about it. So there's still some chance it could happen next year. Or we could be totally wrong. I mean, there's a small chance that it could not happen at all, which would be... Well, I mean, stargazers would be disappointed, but scientists would be extremely excited if it completely defied expectations. But yeah, chances are it's going to happen, and it's going to happen soon.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So if people want to actually see this thing, where should they look in the sky and what kind of tools do they need?

Asa Stahl: So you don't need any tools. For the first few days after the nova goes off, it'll be the brightest. So that's your time to go out and look and see with your naked eye. After that, it'll quickly decline in brightness. And you'll still be able to see it with binoculars or a telescope, but it'll decline pretty fast. And then as for where you should look, the constellation is called Corona Borealis. It looks like a C. It's small. It's not very recognizable. It's kind a hard one to spot if you don't know it already. But it is between Hercules and Bootes, which are much more recognizable constellations. And probably the easiest way to find it is to look for the Big Dipper and then just follow the handle, and it'll point to a place near Hercules where there's a C shape, and that's where it'll be.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I guess I'm going to have pull the binoculars for the after days. I mean, honestly, I guess the whole astronomical community is going to be looking up at this thing. They're already doing it.

Asa Stahl: Yeah, yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's going to be really cool to see the up close images when it finally happens. But before I let you go, we're about to hear from Latif Nasser from Radiolab about their new naming contest for a quasi-moon of Earth. And you also recently wrote an article about the quasi-moons of Earth and how they're different from other things like mini moons and ghost moons. So while I have you here, what is a quasi-moon?

Asa Stahl: Yeah, I saw that naming contest. I'm super excited. I'm going to apply to it. I don't know what I'm going to come up with yet, but it would be incredible to have named the quasi-moon of Earth.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right.

Asa Stahl: So quasi-moon is a weird sort of quirky category of object that defies typical expectations for how things are in space. A quasi-moon is an object that shares its orbit with something else in a particular way that makes it look like, from the point of view of that other object, that's orbiting like a moon. But it's not. It's a trick of perspective. For example, this quasi-moon of Earth that is being hopefully named, that orbits the sun along a path that is almost identical to Earth's path around the sun. But as it goes around, it drifts alternately ahead of and behind the Earth in a way that, if you just look at it from Earth's perspective, it looks like it's actually circling around it. But it's not. So it's a very small gravitational effect. It's not like moon in the Earth, the real moon in the Earth. If you took away the Earth, the moon's orbit would be completely different. It would stop circling where the Earth was. Whereas if you took away the Earth, the quasi-moons would hardly change their movement. It's a very small effect. So those are quasi-moons. But also quasi-moons... Earth has several quasi-moons. We've mostly just begun to be able to discover them because they're usually quite small and dim. But there's also, Venus has Zoozve. That was the first quasi-moon ever discovered. Neptune has a quasi-moon, Pluto has a quasi-moon. Asteroids, big asteroids like Ceres and Vesta, have quasi-moons. Jupiter and Saturn have quasi-moons. A lot of different quasi-moons join the party. And also, these quasi-moons tend to be temporary. So for example, the quasi-moon that is going to be named, which right now is called 2004 GU9, one estimate is that it'll stop being a quasi-moon in the year 2600. When it does, it'll switch to a different kind of orbit where it's still sharing its orbit with earth, but it's no longer looks like it's going around us. And in the meanwhile, other ones will get new quasi-moons that shifted from one orbit to another. So they are kind of all these little asteroids that are on sorts of intimate dances with Earth. And they change exactly the steps of the dance, but broad category of dance remains the same. Hopefully we get to keep naming them all with Radiolab. That's awesome.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know. I mean, what a fun collaboration. And hearing their stories of them connecting with the IAU and the intricacies of that whole process, it was such a saga. I'm glad they managed to pull it off the first time and now opening it up to the public. Whoever wins this contest is going to feel so good that they named this quasi-moon, and for hundreds of years people are going to get to call it by that name. That's awesome.

Asa Stahl: Yeah. And there's one more thing that would be particularly cool is, quasi-moons, because they have these orbits that stay continuously near the Earth, they could be potentially ideal platforms for making observations from. So if you put a telescope or a probe onto one of these things, have it land on it or stay near it, then it could be a really good way to monitor something. I don't know if that would happen with this 2004 GU9 one that Radiolab is going to name, but in the future, other quasi-moons may be around other planets. We could potentially use them as monitoring platforms, and that would be pretty awesome.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's a great idea, honestly, because we can't just keep stashing everything at the Lagrange points. We're going to need some other options. Well, thanks so much, Asa. I'm going to put links to both of these articles on this Planetary Radio page at planetary.org/radio so people can read your work. And if anybody out there is listening and you see Corona Borealis before any of the rest of us do, let us know so we can all check it out.

Asa Stahl: And also that's just quasi-moons, there's still mini moons and ghost moons. So if you want to find that more, check out the article.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Awesome. Thank you. Asa's newest articles on how to see the nova or new star in Corona Borealis and Earth's quasi-moons mini moons and ghost moons are on The Planetary Society's website. I'll link to both of Asa's articles on the webpage for this episode of Planetary Radio at planetary.org/radio. We'll be right back after this short break.

LeVar Burton: Hi, y'all. LeVar Burton here. Through my roles on Star Trek and Reading Rainbow, I have seen generations of curious minds inspired by the strange new worlds explored in books and on television. I know how important it is to encourage that curiosity in a young explorer's life, and that's why I'm excited to share with you a new program from my friends at The Planetary Society. It's called the Planetary Academy, and anyone can join. Designed for ages five through nine by Bill Nye and the curriculum experts at The Planetary Society, the Planetary Academy is a special membership subscription for kids and families who love space. Members get quarterly mailed packages that take them on learning adventures through the many worlds of our solar system and beyond. Each package includes images and factoids, hands-on activities, experiments and games, and special surprises. A lifelong passion for space, science and discovery starts when we're young. Give the gift of the cosmos to the explorer in your life.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: On our April 10th, 2024 episode of Planetary Radio, we invited Latif Nasser, who is one of the co-hosts of Radiolab's podcast and radio show onto Planetary Radio. He told us the tale of the naming of Venus's quasi-moon Zoozve. What began as an error on a solar system poster in Latif's child's bedroom led to a wacky adventure and the naming of a small world. So far, Earth has seven known quasi-moons, some of which haven't been granted official names yet. Radiolab is now collaborating with the International Astronomical Union, or the IAU, to extend the opportunity to name one of Earth's quasi-moons to everyone around the world. There are a few rules and phases to the contest though. Here's Latif Nasser to explain. Hi, Latif.

Latif Nasser: Hi, thanks for having me back.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, it's great to have you on. And lovely to see that this saga of naming quasi-moons is continuing onward.

Latif Nasser: You know, why stop a good thing?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, when last we left our heroes at Radiolab, your team had just successfully named this quasi-moon of Venus, Zoozve. Now you're back at it again with a contest to name a quasi-moon of Earth. What was it about your experience the first time around that made you want to do it again and then open up the contest to everyone?

Latif Nasser: It was just so fun. It was just so fun. And two things. On the one hand, just for me, it was just a fun thing. It was just a fun thing to walk around and think about all the time to be like, "Huh, what should this rock that's zipping around our solar system, what should that be called?" That was just a fun thing to think about. But then also there was part of it where it was like, Yeah, I kind of fell in love with quasi-moons as a category. I was like, "I never heard of these things before. Nobody ever told me about these things." And they seem so cool and weird, and they have names like 2004 GU9. Why are they named so unremarkably for something that's kind of remarkable? Why would they be named in such a plain, boring way? It's like a license plate, auto-generated social security number or something. It's like, "Why would we give them something that's kind of cool and feels like..." Maybe I'm projecting their personalities, but it almost feels like it has a personality but we've named it this supremely boring thing. I had so much fun helping to name Zoozve. How much fun would it be if everybody got in on this? And what kind of weird names are people going to come up with?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'm really looking forward to that part. And I guess it totally makes sense. You pointed this out in our first conversation that the person that discovered Zoozve the first time didn't even know they had done it because it was part of a larger sky survey they were doing. So I'm guessing that's probably why they all have these really boring names. The people that discover them don't even know what they discovered until someone figures it out that it was a quasi-moon.

Latif Nasser: That's right. It's someone coming on the back end and calculating, and after multiple observations trying to connect those dots, figure out that orbit and how exactly it's moving. And then once you do that, you can say that it is a quasi-moon. But by that point, the people who are doing these surveys, the most important mission of which is like, "Is this going to hit Earth? No. Okay, fine. Then don't worry about it. Is this going to hit earth? No. Okay, fine. Then don't worry about it." So that's what they're worried about. And then once they're past it, a few years later when they figure out this thing actually is a quasi-moon, yeah, by that time, it's off their radar literally.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, you guys actually managed to convince the IAU to name this thing last time. And I'm curious because your show isn't always about scientific topics. So I imagine your audience is a little more eclectic and they might not be as tuned into this. What was their reaction when you guys actually managed to name this thing? Was there a lot of hype?

Latif Nasser: Oh man, people were so... It's funny. I can't think of a single other time where we ran an update a week later. We update stories after like, it's like, "Okay, it's been 10 years since this episode came out." This we updated it a week later because people were so excited to hear about what was going to happen. And it's funny, I think I told you last time, we thought it was going to be a real downer for people that we... Because we were trying to get it named so we could say that at the end of the episode, and we weren't able to do it. And we thought it was going to be a downer and people were going to be upset. And then it turned out to be more like a cliffhanger. Everybody wanted to know. And so then we had to do an episode again the very next week.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And that was all because of the intricacies of the IAU and their deliberation process, right?

Latif Nasser: Yeah. It's almost like it felt like a secret society with its own kind of funny rules that I didn't understand. I mean, the rules aren't secret or anything. But trying to figure them out and trying to understand their rhythm, and so I feel like I've gotten to know them a lot more since.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How did they react when you came back at them? Like, "Let's collaborate on a new naming contest."

Latif Nasser: Well, what's funny is, if I'm being honest, I had raised the possibility with them before the naming of Zoozve because I thought they were not... I was like, "There's no way they're going to actually let it be called Zoozve." So I was like, "And then we're going to need something else. For the listeners, it's going to be such a downer when they don't call it Zoozve. So what else could we do? What else could we name, or what else could we..." And then I had this kind of vision of like, "Oh, huh. Well, there are a bunch of earth quasi-moons that don't have names. Maybe there's something there." So I had raised it with them before, and then once Zoozve got named, it was like, "Oh, game on. This was fun. Let's do it again."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, there are a few quasi-moons of Earth. Not all of them are up for grabs for naming. But which one did you guys choose, and why?

Latif Nasser: So Gareth, who's the secretary of the working group on small bodies naming, we met the two of us and he basically was like, "Okay, look, there are this many quasi-moons of Earth. This many are eligible for naming." And he was like, "Okay, look, here are these..." Three or four. He was like, "Here, these are the options." And then he kind of showed me their different orbits and I was like, "Huh, that one's kind of interesting. That one's kind of interesting." And then there was one, I was like, "Oh, that is weird." There's one that I was like, "I don't even know how to describe this shape." He was sort of showing me this animation of it. It's kind of dynamic, three-dimensional thing that he could... It felt like you were swiveling around it in space. And I was looking at it from all these different angles, and I'm like, "Oh, from this angle it looks like a butterfly, from this angle it looks like a saddle, from this angle it looks like this thing, from this angle it looks like..." I was like, "This is a weird shape that I don't even know how to exactly describe." And in a way, that was the thing that was so interesting to me about quasi-moons in the first place because I was like, "How do things move like this in space? I didn't think it was possible to move like this in space." So I picked the weirdest one, and we together picked the weirdest one and we were like, "Okay, this is the one." And its name is a very standard boring name. 164207 is the name. And then the other kind of name, the more Zoozve-ish name is 2004 GU9. Yeah, that's the one.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's the on. Of course a weird orbit like that. Do you know how stable that orbit is? Do they have any idea how long it's going to be around?

Latif Nasser: It's going to be around at least until 2600.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's a good run.

Latif Nasser: And then I think it's kind of like after... And it has almost the exact same. So it takes us 365.25 days to go around the Sun, more or less, and it takes this thing 365.95 days to go around the Sun. So it's a little bit fraction faster than us, but it's basically has the same orbit as us around the Sun. So I don't know what that means, what's going to happen after 2600, but at least it's going to be with us for about another 600 years.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, that's a good enough time to have this name lasts.

Latif Nasser: Yeah, yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But of course, the naming rights, the initial opportunity to name these usually goes to the discoverers or the people that worked on the survey. Did you have to actually reach out to them to see if they were interested in naming it first?

Latif Nasser: So we didn't. That was done by the IAU and by Gareth. And basically what happened was it's almost exactly what happened with Zoozve, where this was discovered as part of this giant survey through this organization called Linear, which is a kind of a partnership between MIT, NASA and the Air Force. They discovered it, but it's kind of one of a kajillion things they've discovered. They discovered it in 2004. They had a long time to name it, which they didn't do it. And then when Gareth asked them, "Hey, do you mind if we... Could we maybe name this thing?" They were like, "Yeah, of course. Sure. Great." And not only did they say that, we offered them, we were like, "Look, you can be on the committee that helps narrow down the names, and you can help be one of the decision makers of which names." And they were like, "No, we trust you." They didn't even want to do that. So it was like, "Cool, cool. Thank you. We appreciate that trust and we will not abuse it." It didn't seem like naming was a huge priority for them. So yeah, it's like, "Okay, I think maybe the rest of the world probably cares about it, so we could do it."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, the naming contest is officially open as of June 1st, is that right?

Latif Nasser: Yep, yep, that's right. So it's only been open a few days. We already have something like 200 submissions, something like that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh, wow.

Latif Nasser: Yeah, just in a few days. But a lot of them are duplicates or repeats or whatever, and we haven't looked exactly how many sort of fulfilled. There's one main criterion, which is important, which is that the name needs to be mythological. And so some of them don't quite fit that. But if you, talking to people out there, if you're into mythology or are interested in trying to name this thing, go find a really cool mythological name. It could be from any culture, even from mythology within literature. So Sarah, you probably know this better than I do, they've named some things after Lord of the Rings and stuff, I guess, in the past. Any kind of mythology that you can imagine that's ripe for a name.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That really opens it up, right? Because a lot of the objects in space are named for mythological things. A lot of those names are claimed. But if you're pulling from all kinds of intellectual properties, you could get some really wacky names.

Latif Nasser: Yeah, yeah, yeah. And beautiful names too. We were talking with Salman Hameed, who's this Pakistani-American astronomer who was involved in the last IAU naming contest which was for exoplanets, and he was one of the jurors, I guess. And he told us this beautiful, now I've forgotten it, but this beautiful Pakistani name for... There was a star and then an exoplanet going around it, and they named it, I guess there's this traditional Urdu name for... It's like a candle and like a bug that's going around the candle, and that's the star and the planet. And he was describing it and how it kind of has this sort of, I don't know, cultural resonance. And it was so beautiful. I was like, "That's such a great name." And just kind of... Yeah, I don't know, I think those names are out there, and if you find one, submit it. Please. You can submit as many names as you want. I'm really excited to see what names come in.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Are there any restrictions on who can actually enter?

Latif Nasser: So there are restrictions because in order to get the submission, we need to get your email address to be able to correspond with you and tell you what happens to it. And to collect email addresses, we can't collect email addresses from minors, I guess. It's like some kind of sensitivity legal thing. So we still really desperately want people under the age of 18 to submit ideas, but you have to do so through a parent or a teacher or somebody else. I did learn, maybe you know more about this story than I did, that Pluto was named by a little girl, by a student. Did you know that story?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I didn't actually know that.

Latif Nasser: Yeah. An 11-year-old school girl, Venetia Burney from Oxford, England, who was interested in classical mythology, she suggested the name to her grandfather, and then her grandfather passed it to an astronomy professor. The astronomy professor cabled it to colleagues, and then they named Pluto. And that was before Walt Disney used Pluto. It's just amazing. It's just amazing that that's possible. We're creating the conditions for that again. If there is a kid out there who wants to name something in space, here's your shot.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Is that the only restriction on what kind of names can be put in, they just have to be mythological? Or is there anything else we have to consider?

Latif Nasser: There's some other ones. You can't name it after a business or a product or anything. But I mean, if they're mythological, then you're not doing that. I don't know. There are a few other rules, but they're all kind of common sense rules. You can't name it after yourself or after a politician or after a business or a product, things like that. If it's mythological, you'll probably take care of all the other requirements.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, you already have several hundred entries, and it's just like a week in.

Latif Nasser: Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I imagine that there's going to be a lot of entries over time. And I read online that there are some phases to this contest. How is this plan going to fall out?

Latif Nasser: So we're getting all these entries, and we really want them from all over the world. We really are, especially because there's mythologies all over the world. And so there's something kind of cool about that that we're all trying to name it together as the world. Okay. So from now, so June until September, the end of September, we're accepting name submissions, and people can submit as many names as they want. The end of September, the name submissions close. Then for the month of October, a bunch of Radiolabers and a bunch of IAU members are going to whittle the names down to 10 or so. Then from there, those 10 will be put up for a fan vote. And whatever of the 10 wins, that'll be the one. That'll be the name. So in November, December, the same website, it'll be open up for voting. And early in January, we are going to announce. The kind of feeling we had was New Year, new moon kind of thing. So we'll announce it early in January.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I would throw such a party when that whole thing was over and just invite all the 10 contestants that finally made it to the top, and invite the IAU members if they can make it.

Latif Nasser: Oh, yeah. We're brainstorming right now, should there be a trophy? Or what should we make? There is a kind of a cool thing that someone requested and that we made, which is actually quite cool. There's a certificate. So if you submit a name, you'll get a certificate. I don't know. It's cool to be a part of this whole thing. And it's cool to submit a name and maybe you'll have a shot. And even if your name doesn't get picked or if you can't come up with a name, you can still vote. So you can still be part of it. It's funny. My wife is like, "You already did this story. Why are you keeping going with this? The story's done, why are you still going?" And to me, part of the fun is like, I don't know, it's just like I had so much fun and I want to open it up to everybody else. But also part of it is, right now, the news is so bleak. There's so much war and politics and everything. It's like it's just bad news around every corner. And I was like, "Oh, this feels like..." And in a way, kind of harkens back to the early internet or something. It's like, "Here is something a big, fun, sweet, nerdy mission we can all go on together, the whole world, especially people who are interested and want to learn a little bit more about astronomy, people who are interested, want to learn a little bit more about mythology. Let's just nerd out together. We need a break and need something to think about and get excited about. And to remind us how small we are and how there's other things going on outside our little planet that are worth paying attention to." And to me, that's it. That's the point. Let's just have some fun.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's such a beautiful reason. And honestly, I think it's the thing that drew me to space even as a kid. You go through these hard things and it really helps you contextualize your place, but also-

Latif Nasser: Completely.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... makes me feel connected to everyone on this planet. Despite our differences, despite all of our hardships, we're all here on this rock soaring through the universe together. And sometimes we just get to look up and do something like name a moon together. I mean, that's part of the best parts of being human.

Latif Nasser: Totally. I completely agree.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Do we know enough about this object to know what shape it is? Because I'm envisioning 3D printing it and sticking on the top of a trophy.

Latif Nasser: Oh, that would've been so cool, Sarah. I would've loved to do that. I think no one knows. No one's ever taken a kind of a close-up picture of it or anything like that. The best guess is it's kind of like potato-shaped, like a gray pockmarked potato, kind of like Zoozve, around the same size as Zoozve. So kind of maybe Eiffel Tower sized or a few football fields kind of thing. But yeah, we don't really know too much more about it. And in a way, to be fair, the thing that interests us about it is less the thing itself and more kind of how it moves. It's kind of in our sidecar, you know what I mean? It's planet Earth, it's our bud. It's like a hanger on. And it's our fellow traveler. It's exactly our fellow traveler.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I've got it now. You need a trophy that has the orbit of this object on it so when you turn it, you can see the butterfly and the-

Latif Nasser: I love it. I love it. If we 3D printed the orbit and put that on a trophy, oh, that would be great. I don't even know if we could physically do that, but we could probably try to find someone to help us. That's a great idea.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: If anybody out there is listening wants to give a help on this one, just let us know because we'll connect you.

Latif Nasser: Yeah. And people have been sending me... There was a listener who sent me this really beautiful laser-etched in wood kind of like a notebook that had Zoozve and the orbit and everything, and I was like, "Oh my God, this is gorgeous." Just someone just made it just to be nice and to be appreciative. And also people have been naming pets Zoozve, and I know there's at least one goat named Zoozve. So if you suggest a name and it gets picked, there'll probably be animals all over the world named whatever this is. There was someone who wrote to me and said that they... It was very beautiful note saying that if their kid was 10 years younger, if their kid was born after this episode came out, they would've named their kids Zoozve.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, it's a cool name.

Latif Nasser: Oh, perfectly fits.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. I know you can't tell me any of the names that are coming into this contest yet, but have you gotten any of that are particularly funny? Because I know in the past, my colleagues, whenever we do these naming contests, just have a really good time looking through all the name options.

Latif Nasser: Oh, they're pretty fun. I've already been looking through them. And they're also coming from so many different countries, which is so cool.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's beautiful.

Latif Nasser: About a quarter of them are from outside Canada and the US. Yeah. So there's one that actually we have gotten this submitted, and this was actually one that Lulu, my co-host. This was her... I think she might've even said it in the episode. She was like, "Oh, of course we got a call it Quasimundo." And so Quasimundo has been submitted a bunch of times already, but there's kind of now a textual question of should that count as mythology? It's a literary figure, Quasimodo, which is French, from the Victor Hugo novel, I think. And so does that count as mythology, or is it literature? Anyway, so we're bringing in some big literary guns to tell us if that counts as mythology or not, but that's one name that has been submitted already multiple times.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, time will tell.

Latif Nasser: Quasimundo. Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Quasimundo. Well, everyone get your submissions ready. I'm going to put a link on this page of Planetary Radio at planetary.org/radio so you can get to their website and submit your entry. And I'm sure when this whole thing falls out, I would love to have you back on so we can actually hear what the result is.

Latif Nasser: Oh yeah, that would be great. We could even tell you, and then you could announce it at the same time as us.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Perfect.

Latif Nasser: Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks so much Latif, and I hope you have a really fun time going through all these entries.

Latif Nasser: Thank you so much, Sarah. I'm so glad. You've been really like a champion throughout this whole time, and I'm so excited and I feel your excitement. And I can't wait to see what comes up, and I can't wait to share it with you and your listeners.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Heck, yeah. All right, well, we'll talk to you in a few months then.

Latif Nasser: Okay. See you soon. Thank you, thank you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I've got a whole list of names I'd like to submit. It's kind of hard to choose. Good luck to everyone who's going to be participating in the contest. Now we turn to Dr. Bruce Betts, our chief scientist, for a look at how we name things on other worlds in What's Up. Hey, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hi, Sarah. How are you doing this wonderful and glorious day?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Doing well. Trying to consider what names I might put on a quasi-moon of Earth. I got to join this naming contest.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, I look forward to hearing your entries as well as the winners.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I think it just has to be something mythical in this case, but there are so many interesting naming conventions for all the different worlds. And strangely, I've been thinking about it a lot recently, not for space reasons, but because I've been playing a game called Hades II, which is all about Greek mythology. So it's funny thinking about all the different family relationships between all the Greek gods and the Titans, and how that just kind of falls out in the English naming for all of our planets, at least for some of them.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, it was seriously messed up. The family relationships, not the naming of the planets. I don't know if you mentioned, Planetary Society has done various naming contests, and it's always fascinating to see what people submit. So we did Bennu, the asteroid that OSIRIS-REx pulled samples from, and going back Magellan spacecraft and Braille asteroid that was visited. And then, of course, Spirit and Opportunity.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What are the naming conventions for asteroids? I don't really know what the rules are.

Bruce Betts: Actually, asteroids are pretty flexible. Very flexible. Basically you need to name it something that nothing else is named out there in space land. You need to keep it a certain length with a certain number of characters, and you need to have a description of why it's named that. And then you need the discoverer proposes those names, and then the International Astronomical Union determines if they make sense. It is very broad, and there are a million of them. So not only tens of thousands are named, but that's why they have to be more flexible, whereas comets are named after the discoverer or multiple discoverers. Usually that gets tricky when you have the surveys now, so there are multiple comets named after certain surveys. And we'll discuss some other stuff. When should we discuss the other things that get named?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right now.

Bruce Betts: How about random space fact? Yay.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yay.

Bruce Betts: Indeed, there are naming conventions, as I'm sure you discussed. But there are ones that I find particularly entertaining when you go. I mean, most of the moons out there are mythological, but then you get to Uranus and they're named after Shakespearean characters. But that would be just too consistent. It's Shakespearean. Or from one particular book by Alexander Pope, and some of them have the same characters. So one, I forgot which one, you'd think would be a Shakespearean character if you're a Shakespeare fan, but it's actually from the Alexander Pope version. Yeah, there you go. So I've mentioned way back when on the show, but I'll mention again, that the asteroid Gaspra craters are named after spas of the world.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Spas?

Bruce Betts: Famous spas, yes. Spas.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Are there spas famous enough? Maybe I just don't go to the spa enough. That shows me.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, I don't think it's like little businesses. It's like places where there was mineral water, and people thought it made them all nifty and cool as well as feeling good, but they often had some religious context. Yeah, anyway. But we got more. You also probably haven't thought a lot about caverns and grottoes of the world, but the craters on the asteroid Ida are named after caverns and grottoes of the world.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: You'd think we would reserve that for other caverns and grottoes of the worlds, maybe some of those lunar lava tubes or something.

Bruce Betts: Again, I just read these. I didn't make them up.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I just work here.

Bruce Betts: I mean, there's a lot. I'm skipping all the very logical things that are tied to discoverers and Mercury artists of various kinds, and Venus' all women, except for one. Actually three. Anyway, that's a detail. But if you think you want to name stuff after pretty things. So on Matilda, the asteroid, craters are named after coal fields and basins of the world.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Man, who came up with these? They're kind of awesome, but also very weird.

Bruce Betts: I mean, they're maintained and overseen by the IAU. And then the USGS, US Geological Survey, has their planetary gazette here online where you can find where these things are and look up whether anyone named a crater after you and things like that. But they're often craters named after scientists or this, that, or the other thing. And usually then they have other restrictions. So it'll be dead scientists. But they're funny things. On Mars you have the very kind of logical, the large valleys and outflow channels are named after the word Mars in various languages.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Love that.

Bruce Betts: There's a lot of stuff to name.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I remember after New Horizons flew by Pluto, there was a while when I was working at the Griffith Observatory where we had this Pluto globe that we could hold up. It had the new image with Tom Bob Raggio and everything on it, and we could show it to people. And it wasn't until I was staring at that thing for too long that I realized how many objects on Pluto are. I'm not even sure if they're official names, but named for things out of Lovecraftian lore or Lord of the Rings lore. That's got to be my favorite.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, yeah. No, they did fun stuff. But tying it again to the Pluto being God of the Underworld, and so you ended up with monsters and creatures and with other things mixed in.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's awesome. I wonder if there's anything out there named Persephone so he can have his lady with him.

Bruce Betts: Well, I'm glad you asked. I just happened to know, or I just looked it up, that Persephone Corona on Venus is named after your buddy Persephone.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's a nice place to retire from the underworld. Just go hang out on Venus where it is Flaming Hot, like Asphodel. Anyway.

Bruce Betts: She's going to feel right at home, I'm sure.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Perfect.

Bruce Betts: She spends half the Venus year on top of Maxwell Montes. That was my attempt to connect it to mythology. I only vaguely know. How about half of some year on Mount Olympus? Olympus Mons on Mars. Huh? Huh?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I was actually reading a book about that by Dan Simmons. Anyway.

Bruce Betts: About Persephone on Olympus Mons?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: No, about the Greek gods living on Olympus Mons. It's a whole thing.

Bruce Betts: Oh wow. It's a thing I didn't know. All right, everybody go out there, look at the night sky and think about where Sarah spends half of each year and where she spends the other half of the year. Thank you and good night.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with even more space science and exploration. If you love the show, you can get Planetary Radio T-shirts at planetary.org/shop, along with lots of other cool spacey merchandise. Help others discover the passion, beauty and joy of space science and exploration by leaving a review and a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day, but helps other curious minds find their place in space through Planetary Radio. You can also send us your space thoughts, questions and poetry at our email at [email protected]. Or if you're a Planetary society member, leave a comment in the Planetary Radio space and our member community app. Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by our dedicated members who have helped name worlds and space missions for decades. You can join us as we keep looking up at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. And until next week, ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth