Planetary Radio • Oct 02, 2024

Return to Dimorphos: Looking forward to the Hera launch

On This Episode

Michael Küppers

Hera Project Scientist at ESA

Ambre Trujillo

Digital Community Manager for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

We look forward to the Oct. 7 launch of the European Space Agency's Hera spacecraft with Michael Küppers, project scientist for the mission. Then Ambre Trujillo, our digital community manager at The Planetary Society, lets you know how to celebrate Europa Clipper by joining NASA's Runway to Jupiter style challenge. We'll close out with Bruce Betts, our chief scientist, and a discussion of the potential future meteor shower caused by the DART impact in What's Up.

Related Links

- Hera, ESA’s asteroid investigator

- The Hera launch: What to expect

- DART, NASA's test to stop an asteroid from hitting Earth

- China targets its first planetary defense test mission

- Rosetta’s Ancient Comet | The Planetary Society

- ESA - Rosetta

- Runway to Jupiter

- Europa Clipper, a mission to Jupiter's icy moon

- The Europa Clipper launch: What to expect

- Europa Clipper: A mission backed by advocates

- Could Europa Clipper find life?

- Planetary Radio: Europa in reflection: A compilation of two decades

- Planetary Radio: Europa Clipper's message in a bottle

- How to spot Comet Tsuchinshan-Atlas

- SpaceX grounds its Falcon rocket fleet after upper stage misfire – Spaceflight Now

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

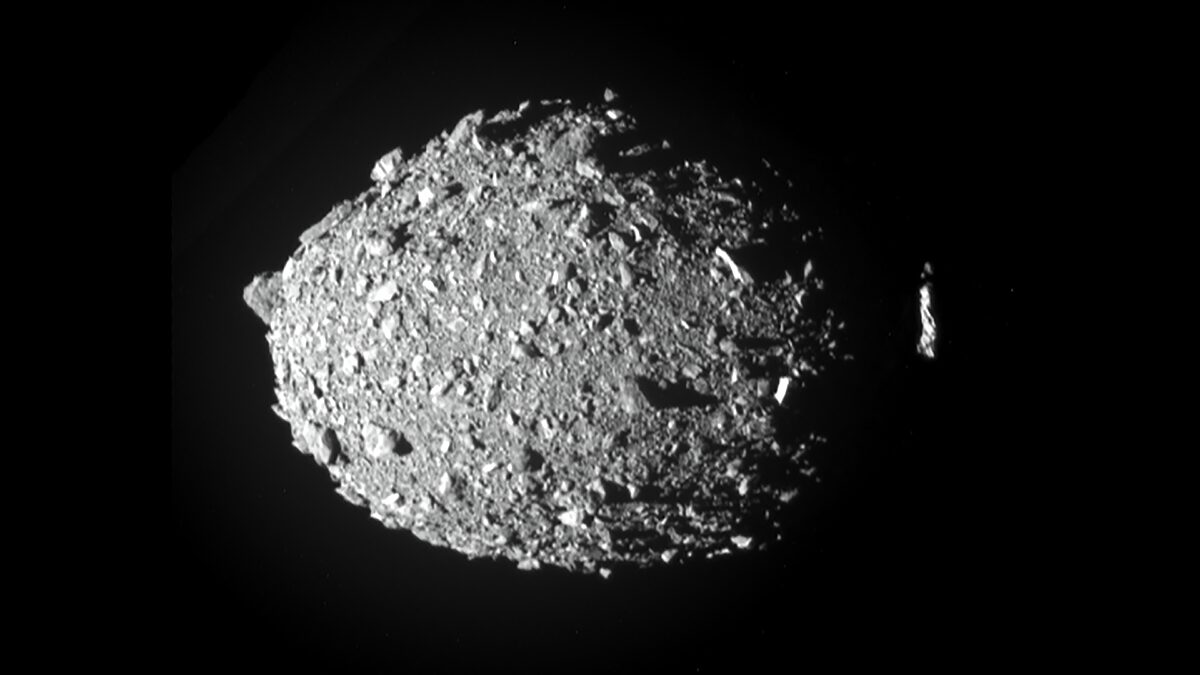

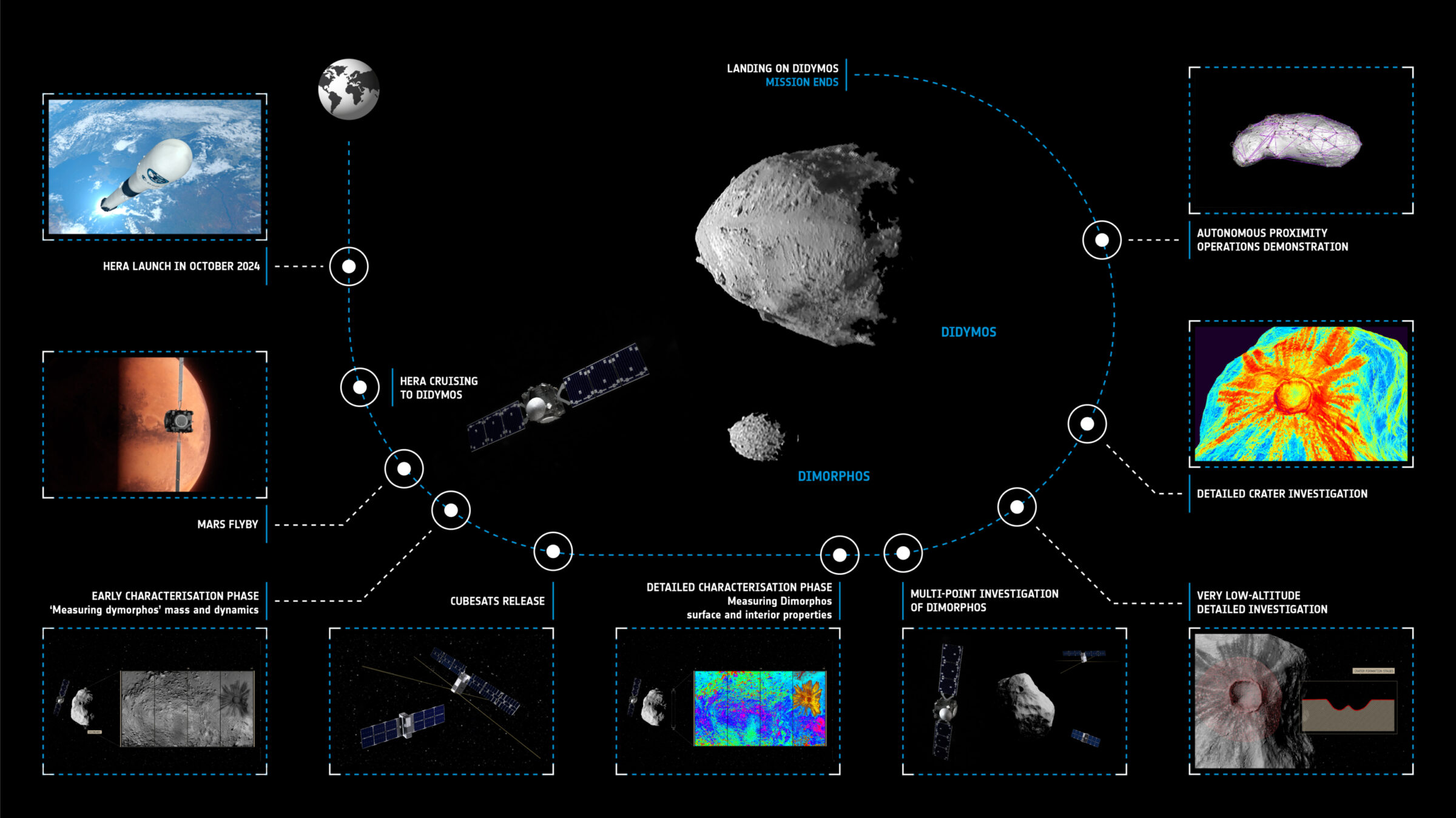

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We are looking forward to the launch of Hera this week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our Solar System and beyond. Happy Launch-Tober, everyone, and Happy World Space Week. Over the next few weeks we'll be covering the highly anticipated launches of the European Space Agency's Hera mission and NASA's Europa Clipper mission. We have so much to look forward to in the coming weeks in space. We'll start today with a conversation about all things Hera with Michael Kuppers, Hera project scientist. Then, Ambre Trujillo, our digital community manager at The Planetary Society, will let you know how you can celebrate Europa Clipper by joining NASA's Runway to Jupiter Style Challenge. We'll close out with Bruce Betts, our chief scientist, as we discuss the potential future meteor shower caused by the DART impact in What's Up. It's also the first week of the month and you know what that means. It's time for our monthly Space Policy Edition of Planetary Radio. As the United States approaches the upcoming presidential election, Casey Dreier, our chief of space policy, delves into what the election could mean for space. Last month, he spoke with Greg Autry, who served on Trump's NASA transition team in 2016. This month, Casey interviews Lori Garver who served on NASA's presidential transition teams for Clinton and Obama. She'll let us know what a potential Harris administration would mean for space exploration. You can catch our upcoming Space Policy Edition on Friday, February 4th. If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it. I can't believe it's time. It is officially Launch-Tober. Space fans all over the world have been eagerly anticipating the launch of the European Space Agency's Hera mission to the Didymos Dimorphos asteroid system and NASA's Europa Clipper mission to investigate an ocean moon of Jupiter. Coming up first on October 7th is the launch of ESA's Hera mission. It's a direct follow-up to NASA's Double Asteroid Redirection Test or DART mission. The DART spacecraft, which launched in 2021, had a relatively straightforward but critical goal to test the kinetic impact or method for deflecting asteroids. Essentially, they slammed a spacecraft into an asteroid to see if they could change the object's trajectory, and it was a smashing success. DART's target was Dimorphos, a small moonlit orbiting an asteroid called Didymos. In September 2022, DART made a dramatic impact successfully altering Dimorphos's orbital period around Didymos and making history. And now that the debris from the blast is mostly cleared, ESA's Hera mission is set to head back to the system to investigate. On October 7th, 2024, Hera will blast off from Cape Canaveral, Florida on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. Hera is equipped with a comprehensive array of high-resolution visual laser and radio mapping instruments. These tools will let the spacecraft do a thorough investigation of the impact's aftermath, including a careful analysis of the DART impact crater measurements of Dimorphos's mass and tracking of the orbital changes. Fans of the DART mission may remember that it released a CubeSat before the impact the Italian Space Agency's LICIACube. The upcoming Hera mission is going to build on that success by deploying two CubeSats named Milani and Juventas. Part of what we do here at The Planetary Society is advocate for and support planetary defense missions. While the threat of an asteroid impact is statistically small, it's still serious. Our intelligence, as a species, has given us many gifts, but one of them is that humanity actually has the chance to prevent that kind of large-scale disaster and save all of the creatures on Earth. All we have to do is take steps to track, characterize, and deflect incoming near-Earth objects. Missions like DART and Hera are crucial in helping us make this happen. Our guest today is Dr. Michael Kuppers, project scientist for ESA's Hera mission. Michael is a planetary scientist who focuses primarily on researching the physics of small bodies in our Solar System that includes comets and asteroids. He spent more than a decade working on ESA's Rosetta mission. That was the first spacecraft to rendezvous with a comet and follow it in its orbit around the sun. Now, Michael is applying that expertise to Hera and to planetary defense. With less than a week to go until the big day, Michael and the rest of the Hera team are preparing for the launch. Hi Michael, thanks for joining us.

Michael Küppers: Hi, good afternoon.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Congratulations on this upcoming launch. This has got to be really exciting.

Michael Küppers: Wait, was the congratulations for afterwards?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know, right. And I should mention too that this launch is scheduled for some time between October 7th and the 27th, but we're in the middle, as we record this, of a hurricane in Florida, Hurricane Helene. So, I want to send my well wishes to everyone who's impacted as well as any members of your team that might be on the ground right now setting up for the mission.

Michael Küppers: Yes, indeed. We have to hope, and there seems to be some indication that the hurricane is moving away, so we are still in good spirit for the launch.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: For those who are unfamiliar with Hera, we've spoken a lot about the DART launch in the past, but this is the follow-on mission. Can you tell us a little bit about the primary goals for Hera?

Michael Küppers: Yeah, indeed. So, that has successfully impacted the Dimorphos, the moon of asteroid Didymos, two years ago. And now, we are launching Hera, which will need another year to get there to then, in late 26th and 27th, investigate what exactly has happened during the DART impact. One goal is to measure the mass of Dimorphos, which we need to understand how efficient the impact was. Another goal is to look at the exact outcome of the impact. There was a crater formed or was the impact stronger that really it became so big that the whole moon, the whole Dimorphos was deformed by the impact? And the third goal is to generally investigate the two asteroids to essentially be able to extrapolate results to another asteroid that we needed one day to save us.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: The papers I've read so far and the previous conversations I've had with people from DART seem to indicate that this last impact completely changed the shape of this object. So, getting a close-up look at what actually happened here is going to be just fundamental.

Michael Küppers: Indeed. We do have some evidence that the shape of Dimorphos may have changed, and it's indeed now essential to see what exactly happened.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So, when the DART impact actually happened, we monitored it not only up close with the Italian Space Agency's LICIACube, but also with space telescopes and telescopes all over the world. What is it about getting up close with the system with Hera that we can't learn from the ground?

Michael Küppers: One thing we can't learn from the ground is what happened to Dimorphos itself. From the ground, Didymos, the main asteroid, and the Dimorphos, moon, are just one point of light. So, a change in the shape or in the rotation state of Dimorphos is not possible to derive from the ground-based observations in a unique way. This is where we needed another mission.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And as with so many wonderful missions, this evolved out of an earlier mission concept. In this case, the Don Quijote kinetic impactor from the early 2000s, how did that become Hera and how did that end up as a collaboration between the United States and ESA?

Michael Küppers: Actually, Don Quijote was before my time, but around 2000, the idea started of a planetary defense demonstration, which is quite similar to what now happened with DART and Hera in the sense there was one impacting spacecraft and one observing spacecraft. At the time, it was foreseen to slightly modify the heliocentric orbit of an asteroid. Then, Don Quijote didn't really receive funding. It was in a sense a little bit ahead of its time. At the time, there was no planetary defense office in ESA, and it didn't really fit in the existing program. At the end, there was really no funding for it, so it didn't materialize. And then, a couple of years later, APL came up with a specific idea to do the same but on binary asteroid. So, the advantage is mainly that you need a smaller impact, let's say, to measurably change the orbit of an asteroid moon around the main asteroids, and it would need to change the heliocentric orbit of an asteroid. And when this idea came up, the colleagues contacted ESA for possible collaboration and from this came first DART and AIM. So, at the time, the asteroid impact mission was proposed to arrive before the DART impact and to monitor what's going on there. In the ESA Ministerial Conference in 2016, AIM raised a lot of interest but not sufficient funding, but because of the interest, the study was continued. And in the slightly modified form of Hera, it was then approved in 2019 and will now be launched in October this year.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I love too that in tribute to Professor Milani who came up with this idea from the University of Pisa in Italy, you named one of the CubeSats after this professor. That's such a sweet thing to do.

Michael Küppers: Yeah, that's right indeed. As you said, one of the, let's say, founding fathers of [inaudible 00:09:57] was Professor Andrea Milani at University of Pisa, who unfortunately passed away in an accident a few years ago, and so the Hera team decided to name, yes, one of the CubeSats after him.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's beautiful seeing the legacy there. I wanted to mention too that we're coming up on the 10th anniversary of ESA's Rosetta mission to comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko, and you worked on that mission for... What? Almost 15 years?

Michael Küppers: Yeah, I was involved in that mission for a long time, yes, yeah, around 15 years or so.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What's interesting about this is that we have so few examples of these small bodies that we've ever been able to go up to, let alone land on. I'm sure there's a lot of lessons we can take from the Philae lander and Rosetta's landing on Chury that we can then apply to this new mission.

Michael Küppers: That's true. Indeed, the concept of the operations around the asteroids with Hera is essentially borrowed from Rosetta. So, the whole concept of the hyperbolic arcs with first and early... What you call? Early characterization phase from some distance to get the global properties of the asteroids and then getting closer and closer and to finish up with a close flybys and then landing. This whole concept is pretty much taken over from what was done on Rosetta.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Although we've seen with other missions that have tried to not even land on asteroids but just touch the surface that it creates all kinds of ejecta or, in the case of OSIRIS-REx, it almost swallowed the whole spacecraft. So, it's going to be a really interesting challenge to try to land something on this.

Michael Küppers: Absolutely, and I have to say our success criteria would also not be the usual success criteria because you also have to consider our CubeSats are essentially just small boxes. They are not dedicated landers. So, if they land and bounce back and go away into space, I think it would still be a success. We would learn a lot from the fact and also from the way they interact with the surface. So, in this sense, our success criteria, I mean, if they stay and continue operating, it would be absolutely marvelous, but we cannot necessarily expect that it's going to happen.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I really hope it does though because each of these CubeSats are on separate missions, but Juventas, specifically I think, is supposed to be mapping the interior of Dimorphos. I want to know what's going on there, what's going on in the interior, how that was changed by the impact. That's some science I'd really like to see done.

Michael Küppers: Now Juventas, indeed, it's the first time that we carry a radar to an asteroid. Actually, from orbit, Juventas will investigate the interior. It's different from the Rosetta radar, which was essentially a ping-pong between orbiter and lander. It is a monostatic radar that essentially measures reflected signal from the asteroid. So, this will be done while Juventas is in orbit.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What is Milani, the other CubeSat, going to be doing?

Michael Küppers: The main instrument of Milani is visible in the infrared imaging spectrometer. So, the main goal there is the surface composition and the surface properties you can get from spectroscopy and from imaging also at various space angles.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's going to take a little while for the Hera mission to actually reach the system. What kind of orbit is it going to be taking on once it gets there?

Michael Küppers: Once it gets at the asteroid, because the asteroids are so small, Kepler orbits would not be stable and would need lots of corrections. So, what is done are hyperbolic arcs. Essentially, you are continuously above the escape velocity, which is 40 centimeters per second for the system at the closest and make a maneuver every three to four days to get back to the asteroid. And you fly these arcs to get some global coverage of the asteroids. And once you have the shape, the mass and so on, you then first repeat [inaudible 00:14:01] same nearby. In that process, also the CubeSats are released, and then to see spacecraft are operating there independently. And, at some point, we switch from these arcs to flybys, which are essentially straight lines, and they get closer and closer to the surface. You want to go down to less than a kilometer from Dimorphos. And similar to flybys of course, with the spacecraft maneuvers, they are inverted to stay in the environment of the asteroids.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And then, once the spacecraft actually reaches there, it goes into orbital insertion. How long is the mission going to be in operation?

Michael Küppers: Nominally, the mission will be in operation for six months.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's not a whole lot of time, but at the same time it's probably enough to see what happened there considering... I hope.

Michael Küppers: It's hopefully enough to see what happens there if everything goes well, yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What kind of data are we going to be getting back from the spacecraft?

Michael Küppers: For being relatively small missions, we have a lot of payloads there. The main spacecraft carries cameras, the what we call asteroid framing cameras, who are getting images both from the autonomous navigation and for signs of a planetary defense. We also have an imaging spectrometer that works in the range, roughly 650 to 950 nanometers, a thermal infrared imager in the 10 micron regions, that is contributed by the Japanese Aerospace Agency JAXA and a laser that is also both used for scientific measurements of the surface and for navigation.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What kind of resolution are we going to get on the surface features of this thing?

Michael Küppers: From the characterization orbit at 10 kilometers, we get about one meter per pixel resolution. And correspondingly, when we have a close flyby at one kilometer, we go down to 10 centimeters.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: In the case of OSIRIS-REx at Bennu, we ended up with a beautiful 3D rendering of that object. Are we going to get something similar for Dimorphos?

Michael Küppers: I hope so, yes. Yes, I mean, we will of course, of the images that are being taken from essentially all three spacecraft, we will create shape models of the asteroids since this can also be then used for 3D renderings.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I hope so. 3D print it and add it to my collection of small bodies I have on my desk. I actually have one of a comet, Churyumov-Gerasimenko, on my desk that was I think leftover from the time that Emily Lakdawalla worked at The Planetary Society.

Michael Küppers: Oh, yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We're going to end up with a spacecraft looking at this object. Do you think we're actually going to be able to see fresh unweathered material from this DART impact?

Michael Küppers: Possibly, yes. Especially, I could imagine that we see fresh unweathered material on Didymos, the material essentially that left Dimorphos that landed on Didymos and also even of Dimorphos itself, if you get material from the subsurface, it could be or should be somewhat different from the user surface material.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I hope so. I mean...

Michael Küppers: I hope so, yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... a lot of this is about learning more about planetary defense, but I think part of the mission that a lot of people aren't giving it credit for is that this is an opportunity for us to learn a lot about the foundational building blocks of our Solar System essentially by looking at this material.

Michael Küppers: Absolutely, absolutely, yes. Absolutely. Asteroids and comets as the building blocks of the Solar System, essentially, the small bodies that the planets are made of or they're the leftovers, those that haven't found a planet in the origin of the Solar System and now are still around and tell us exactly how the conditions of the formation was. And also, it's the first mission to a binary asteroid. We also hope that we will learn a lot about how those binaries formed.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That is a really interesting thing because we've seen this system. We saw during one of the earlier Lucy mission tests, they flew by an object that turned out to be a binary asteroid. We only have so many examples, but I think if I'm remembering correctly, it was something like 15% of all small body systems are binary asteroids, is that right?

Michael Küppers: Yeah. That's right, and I would consider that maybe a lower limit in the sense that not all those binary systems are detected from ground. At least both the old days, the very first one, EDA, the satellite of EDA was detected by a spacecraft. And now, Dinkinesh also was identified as a binary from ground-based observations, so you can speculate that there may even be significantly more than 15% that are actually binary asteroids.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's pretty funny that we keep being surprised by these, but given the difficulty, all you really have is light curves and things like that to try to tell you what these things are like or maybe radar.

Michael Küppers: Yes. Nowadays, a lot of them is light curves with radar and also now with Gaia, also with astrometry, but it's still the case that those techniques are not sensitive to all types of possible binaries.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How does this system compare and mass to those other binaries? And will it actually allow us to extrapolate out what we can know about other binary systems?

Michael Küppers: I would say that the Didymos system is a typical binary in terms of the separation and size ratio and so on for binaries of small nearest asteroids. So, in that sense, I would say we could probably learn something more globally from understanding how that system form.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: A lot of what I've read online suggests that we think. The reason we end up with these binaries could be because of this Yarkovsky effect, right? A larger object gets spun up by the light of the sun and then-

Michael Küppers: The YORP effect, yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah.

Michael Küppers: This is one thing, that exactly that the YORP effect spins it up, and then material is shed and forms the binary. Another possibility are impact, either directly from the impact ejector or the other option is that the impact leads to spin up above the highest faster than the cohesion limit, and that the formation of the binary comes from that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: This system spends about, I think it was like one-third of its time in the asteroid belt where it's-

Michael Küppers: Indeed.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... more dense. So, what are the odds that this thing has been hit by objects the size of DART before?

Michael Küppers: It has been hit by objects the size of DART before. With DART, it was difficult to identify craters or a couple of potentially identified craters, but this may be indeed because we are also not sure if the DART impact created a crater or more deformed the object. But just taking the statistics of impact rates and cratering and the lifetime of Didymos and Dimorphos, it's highly likely that DART-size impacts have happened before.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: By comparing the cratering on not just Dimorphos but also Didymos, I bet we can get a better understanding of how this impacts these things over time. I'm really curious to figure out how we can disentangle the YORP effect from it being pummeled by objects in the asteroid belt to actually figure out the history of this thing.

Michael Küppers: Yeah, this is indeed true. There's now a newer publication that says that in the case of Didymos, as you said, spends a third of the time in the main belt, impacts are probably more important than the YORP effect, also because of the possible spin-up due to impacts. And one other aspect of this is all the edge determination because one point is also to find out how long the object has been in this orbit. And for the edge determination, we use a cratering record. And here, we have also the unique opportunities that we investigate. Okay, a crater or the impact outcome, let's say, for something where we exactly know the impact of this DART, we know exactly the impact, its size, its mass, its velocity, which helps us a lot to improve our crater scaling, so essentially to say which impact on such an object it creates, which kind of impact outcome, and therefore also to improve all those models that are connected to the impact.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: When we hit it with DART, the ejecta was just, at least personally, so much more than I expected. That thing was beautiful indeed.

Michael Küppers: Yes, indeed. Yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How big of a cloud did we create and how long did it hang around after the actual impact?

Michael Küppers: Okay. It hung around for several months. Also, the extended cloud was seen by ground-based observers and HST for several months after the impact. Size, I don't like yet to specify size because it's a cloud that is expanding into interspace. It doesn't really have a boundary in that sense.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Is there any concern that any of the subjected material is still close enough around that it might, in some way, harm the spacecraft?

Michael Küppers: Any small material by the time it arrives will have been pushed away by radiation pressure. It is possible that a small fraction of larger blocks maybe get into stable orbits for years and may also still be present when Hera arrives. I'm personally not worried about that simply from scaling from Rosetta. Rosetta operated for two years around an active comet, and collision with things was never a problem that Rosetta had to back away for some time was essentially because of dust confusing the [inaudible 00:23:43]. So, about some boulders being around with here, I'm not worried, and I think the background is that, in such a situation, we intuitively tend to overestimate the collision probability.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, fingers crossed.

Michael Küppers: Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh, man. I did read too that we hit that thing so hard that there's a chance that we might actually see meteor showers caused by this object either on Mars but also potentially on Earth. Were you one of the people that created that? If I'm remembering-

Michael Küppers: Yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... correctly, you were on that research.

Michael Küppers: Yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: If that does happen, how would we determine whether or not the meteor shower that we see is caused by the DART impact?

Michael Küppers: From the model, from the numerical model, we can relatively precisely say from which directions the meteors would be coming. In time, they are much more distributed. We cannot predict a specific date. We can just provide it some time spent where we could see some enhancement. Now, to limit expectations, I wouldn't expect a meteor shower like the Perseids. We would really be looking from an enhancement in that direction of the sky at certain times.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It occurs to me that between DART and all of these other objects that have hit these things in the past, that there is a potential that Dimorphos might not last forever. If it keeps getting blown apart by these things, at least if it's a rubble pile enough, is that possible that it might get blown apart over time?

Michael Küppers: Absolutely. At some point in time, either Dimorphos or Didymos, I'm not sure which is a higher lifetime statistically, will be hit by something that's destroyed it. Those kind of impacts were also that led to the formation of what's now Didymos and Dimorphos from some larger objects. Basically, all asteroids smaller than a hundred kilometers or so are as a result of fragmentation and re-accumulation, and they're not original objects in that sense.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But who knows, maybe it'll create a new one after it gets blown apart or...

Michael Küppers: Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely, yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... maybe the material might just fall back onto Didymos.

Michael Küppers: Yeah, I guess if now Dimorphos is destroyed by an impact, probably part of the material will escape and part will fall back on Didymos. And if in case Didymos is hit by something large, maybe it'll form another moon.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That would be cool.

Michael Küppers: Several decades ago, the general opinion was that asteroids cannot have moons.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's funny how wrong we've gotten so much at this. It's just the beginning of understanding this, which is a really interesting thing to think. I feel like so many people want to believe that we have a good handle on what's going on with asteroids and planetary defense, but we're just taking our first baby steps.

Michael Küppers: Yeah, planetary defense, DART and Hera are really the first technology demonstration for planetary defense. In that sense, we are at the beginning.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. The DART mission was actually my first rocket launch that I got to go see. If I'm back to-

Michael Küppers: My mine as well. It was also-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Really?

Michael Küppers: ... the first launch that I saw. Yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's amazing. Are you going to be in Florida to see Hera go up?

Michael Küppers: Yes, yes, I will also be. That will be the second one for me, and I'm flying next Friday to Florida for that. Yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Do you get to stick around to try to see Europa Clipper launch afterwards?

Michael Küppers: Yes, I'm going to try to see Europa Clipper as well. Yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh, I'm jealous. That's going to be so cool. So many of my colleagues get to be there for Europa Clipper, and I hope so much that both of these missions go well. That's going to be such an adventure. So, we're potentially going to get 3D models out of this thing, but are there any onboard cameras that are going to give us some really spectacular imagery that we'll be able to look at online?

Michael Küppers: Yes, of course. The images will be distributed. We have an open data policy, so you can see. Will be relatively soon to see the images of the asteroids, and we also have the cameras on the CubeSats, and we have the so-called small monitoring cameras on Hera that will image the release of the CubeSats.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's going to be really cool. Will the CubeSats be able to image Hera back and actually see the spacecraft?

Michael Küppers: That's a good question. I'm not sure at which distances could be done and what puts the resolution be, but we should definitely try it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It'd be so cool because anytime we get an image of a spacecraft in space from the CubeSats, it's always one of the most iconic images I've ever seen. The fact that we're doing this at all is just absolutely mind-blowing.

Michael Küppers: Yeah, and actually, there's one reason also for the small monitoring cameras the other way around. It may be difficult well after release because the CubeSats are so small.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So, something that I'm really looking forward to in this case, I guess, is actually seeing the images of the impact site. What are some of the things that you are most looking forward to?

Michael Küppers: Indeed. Seeing how Dimorphos looks like now, essentially how the side of that looks like now and also how the other side looks now that DART and LICIACube could not see.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, because we zoomed up on that thing and then literally crashed into it, so it's not like we've got a lot of time to see both sides. I mean, we're going to try to discern how this thing was changed just from the front side of Dimorphos, but there's so much we don't know about what this thing looks like.

Michael Küppers: Yeah. We don't really know how the back side, so to speak, look before the impact but already seeing the changes on the front side will be interesting.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll be right back with the rest of my interview with Michael Kuppers, project scientist for ESA's Hera mission, after this short break.

Bill Nye: Greetings, Bill Nye here. NASA's budget just had the largest downturn in 15 years, which means we need your help. The US Congress approves NASA's annual budget and, with your support, we promote missions to space by keeping every member of Congress and their staff informed about the benefits of a robust space program. We want Congress to know that space exploration ensures our nation's goals and workforce technology, international relations, and space science. Unfortunately, because of decreases in the NASA budget, layoffs have begun. Important missions are being delayed, some indefinitely. That's where you come in. Join our mission as a space advocate by making a gift today. Right now, when you donate, your gift will be matched up to $75,000. Thanks to a generous Planetary Society member. With your support, we can make sure every representative and senator in DC understands why NASA is a critical part of US national policy. With the challenges NASA is facing, we need to make this investment today, so make your gift at planetary.org/takeaction. Thank you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Did you get to go to a party or anything to actually watch the DART impact? Because I know some of my colleagues did.

Michael Küppers: Yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah?

Michael Küppers: Actually, yes. I was at APL for the DART impact. It's the events there.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh, that's wonderful. You were probably there with some of my coworkers. That's so funny.

Michael Küppers: Yeah, probably.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What was that like? For me, watching it online it was a...

Michael Küppers: What was really spectacular for DART is that it was transferred practically in real time. Essentially, the data was streamed as it came from the spacecraft, and you could, in that sense, see the impact. I mean, not the impact itself, but the images when DART started to approach the impact, that was really spectacular.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, that moment when the screen tried to give us an image, but it was like half an image, the other half was all red and messed up, that was-

Michael Küppers: Yes, yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... that was such a moment.

Michael Küppers: And also before this extreme detail, and you knew that... I mean, you knew of course it would end, but it was really... Oh, yeah. It was a whole time from actually seeing the asteroids and seeing Dimorphos for the first time to getting closer, and then it was really spectacular to be able to see this in real time.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I was such a party to witness online. And from afar, is your team doing anything? I mean, fingers crossed, hopefully everything goes well with the launch of this mission. What is your team going to do to celebrate after the mission successfully launches?

Michael Küppers: Okay. I have to say to first give credit to my colleagues in the operation center who have to work after the mission successfully launched.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah.

Michael Küppers: But we will have the celebration with a dinner party at Kennedy Space Center, which those who do not have to work on the operations.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh, you're going to have such a treat. I only got to go there-

Michael Küppers: I can imagine, yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... once, but it was for the Artemis I launch that didn't happen. And despite the fact that the launch didn't happen, that place was so cool. It was absolutely worth doing, anyway. So, this thing actually, it hasn't gone up yet. What are the last steps that everyone has to take for preparation for this launch?

Michael Küppers: So, the very last step, I think fueling of the spacecraft is finishing today, and then I don't know the exact setup, but then essentially it is fixed to the rocket and rolled out to the launch pad, where it now has to wait first of the Crew-9 launch going into space.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What would you say that this mission could do for the future of planetary defense?

Michael Küppers: I think it is the first time that we start. We have demonstrated the method. And with Hera, we know the quantitative outcome, which helps us really for the future to not only to repeat it, but also to scale what size of impact you need for a given target.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How did you originally get into this field? I mean, given your history, you went and worked on the Rosetta mission and now this, how did you become so passionate about small bodies and planetary defense?

Michael Küppers: I'm planetary scientist by education, and I relatively early on, among other things, I did start working on asteroids and comets both observationally and also a bit modeling. And in 2003, I started working on the science camera team of the Rosetta missions. And a couple of years later, I moved to ESA and became involved there. And so, yeah, this brought me really close to the space machine, and this is a fascinating topic, and I stick with that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I just imagine one of these days if we actually save the world using the science that was created from this, you'll be able to look back and think to yourself, "Well, I helped save the planet."

Michael Küppers: Yeah, that's true. I saved the planet.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh, man. Especially, of the missions that are out there, I think the Rosetta mission, it's definitely one of my favorites just for the imagery that came out of it. This kind of alien world, the way that the kind of dust and the sand, it was beautiful.

Michael Küppers: Yeah. For me, okay, I'm biased because I've worked on the mission for a long time. But yes, for me also, Rosetta was really maybe the most fascinating missions we see. Also, seeing more and more detail when you arrive, and then this long time at the comet, and the comet even better than an asteroid, you can see the changes in "real time," how the comet changes due to its activity and feel a landing. And yes, it was really spectacular.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I got really emotional near the end of that mission when Rosetta found Philae again. I remember that situation, which who knows if there'll be a similar situation with one of the CubeSats here where it tried to land and then bounce, and we couldn't find it.

Michael Küppers: Yes, could be, yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But is there a similarity there as well in that at the end of the Rosetta mission, the spacecraft tried to land on the comet? Is that what we're planning for the end of the Hera mission as well?

Michael Küppers: Possibly, yes. Definitively, we are trying to land Juventas on Dimorphos. And most likely, we are going to land Milani either on Dimorphos or on Didymos. For Hera itself, it's not yet finally decided, but an option is also landing at the end of mission.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But what's going to dictate which of the two objects Milani tries to land on?

Michael Küppers: Okay. The argument for Dimorphos would be that if you want Dimorphos as a planetary defense target and Hera as a planetary defense mission, and the other thing is of course the instrumentation is complementary. So, for Juventas, the main thing would be after landing to use a gravimeter to get the exact, essentially the three-dimensional accelerations, and an exact grab on the gravimetry may be also on the mass distribution of the object. For Milani, the interest would be more on the dust detector to get maybe more material essentially, more information about the dust from the dust that would be moved up at landing.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Are there any difficulties in trying to orbit a binary system specifically that we don't really have to deal with in other cases?

Michael Küppers: It's more complex to orbit a binary system than orbiting a single asteroid. At the same time, I think this difficulty kicks in relatively close to the object, because, globally, more than 99% of the mass of the binary asteroid is in Didymos. So, if you are significantly further away than the separation between the two, it shouldn't matter that much that it's a binary. But I think the other aspect is that most binary asteroids have been detected relatively recently, which is the reason that more... I mean, for example, the near mission went to EROS in 2000, one thing is that EROS is a relatively large asteroid and in near space, we don't have a binary at that site. But also, when this mission was planned, not many binary asteroids were known. So, what the other reason is that the binary asteroids themselves are relatively recent discovery.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I think you're probably right that we're going to learn that this is actually the lower bound of how many of these there are. Given that we keep stumbling upon them, I wouldn't be surprised if there are a lot more than we anticipate.

Michael Küppers: Yes, I also would personally expect that we will be somewhat beyond the 15% currently. That is what we get from the ground-based observations.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Have you been able to go to the Planetary Defense Conference before?

Michael Küppers: Yes, I have been there twice, I think, yes. It's an interesting thing, this exercise, this impact exercise that's happening there usually, and yes, it's something good to do. Also, the planning, what would you do if it happens essentially?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. This is a truly international problem. It affects every single one of us. Even though it's a rare thing, it's something that could potentially harm everyone on Earth. And so, seeing the interplay between NASA and the DART mission and ESA and the Hera mission and the international friendship and collaboration that comes along with that, I think, is really exemplary of this idea that it's something that impacts all of us. And that's part of what's so special about space exploration is that it creates these bonds across nations that allows us to really collaborate in a meaningful way.

Michael Küppers: Absolutely. It's an international site, this one, and also it's an international endeavor with most international space agencies involved in the planetary defense activities.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'm so grateful because, as a child, I know it was movies like Armageddon and Deep Impact that scared me, but I was very, very concerned that humanity wasn't doing enough to protect the people of Earth and all the creatures from this inevitable potential that we're going to be hit by something at some point, and it feels like we're finally being able to get a handle on this. This is the beginning of us being able to save the world.

Michael Küppers: Yeah, I agree with that. Personally, I'm not really worried simply because I know within the next, I know, several decades, I will die at some point. And then, asteroid impact is an extremely unlikely reason to be the reason for that. But it's true. It's a dangerous that as humankind, we can now or we think we are now on the way that we will be able to prevent it. And I think we should prepare, and we should be able to prevent it to be prepared for the next time it happens. And those things that are outside our, let's say, our experience, it's sometimes difficult to really consider and to really, really convince also that this needs prevention or that it is useful to do planetary defense. In this respect, I like to compare to the pandemic, which is another thing that is not happening, that's frequently outside our experience. And also, I've been talking like this about planetary defense for years now. I also wasn't prepared or aware of that I should be prepared for a pandemic. I think for those things, it's a bit in human nature that we don't worry about things that are outside our everyday experience.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But in the event that that rare occasion happens, we have scientists all around the world that are laying the plans in order to deal with something like this.

Michael Küppers: Absolutely. Absolutely, yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What do you think you're going to feel when it actually gets off the ground after all of this effort?

Michael Küppers: I don't know. I would probably be a bit nervous, but also very happy to see it actually going into space.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I know I'll be watching. Are there any live streams online where people can watch Hera launch?

Michael Küppers: Yes. I believe Hera launch should be live-streamed by both SpaceX and also by ESA TV.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Wonderful. Well, we'll share that live stream online at planetary.org/live so people can watch, but if there are any Planetary Society members listening, please join us for a watch party inside of our member community because there's nothing like sharing these moments in space with other space fans that have been anticipating them for years. So, I'm looking forward to watching that with everyone online.

Michael Küppers: Yeah, that's great.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, good luck to you and to all of the members of the team, and I hope you have a really fun time in Florida just watching these launches. There's nothing like being there at Cape Canaveral for this-

Michael Küppers: It's good, yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... with this huge audience around you. You're going to have the best time ever. Well, good luck to you and everyone on the team, and I'm hoping in the future that after the launch happens, fingers crossed, everything goes great. I'd love to bring a member of the team back on to talk about reflections of how it went and how it felt to see this.

Michael Küppers: Yeah, sure, sure, sure. Again, we're happy to talk about that, yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Awesome.

Michael Küppers: And how it goes with the first observations after launch-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh, absolutely.

Michael Küppers: ... of the mission.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Definitely bringing everyone back on once we get those first images. That's going to be a huge moment.

Michael Küppers: Yes.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Awesome. Well, thank you so much, Michael. Good luck.

Michael Küppers: Okay. Thanks to you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: As I said in the interview, The Planetary Society is holding an online watch party for the Hera launch in our member community app. The launch is scheduled for October 7th at 10:45 AM Eastern Time. That's 7:45 AM Pacific Time or 1445 UTC. We'll share the launch live stream at planetary.org/live so anyone can watch. If you're a Planetary Society member, you can join me and my colleagues in the watch party chat in the rocket launch space in our community. We're also going to be holding a watch party for Europa Clipper just a few days later. That's on October 10th at 12:31 PM Eastern Time, which of course is 9:30 AM Pacific Time or 1631 UTC. Keep in mind that all of these times may change. Rocket launch times vary depending on what's happening with the rocket or what's going down with the weather at the launch site, but this situation is a little more complex than usual. As I'm recording this, the US Federal Aviation administration has confirmed that SpaceX's Falcon 9 rockets are grounded because of issues during the Crew-9 launch over the weekend. We're hoping all is well and that the FAA will clear the missions for launch in the coming days. I'll leave a link with more information on that story on the show page for this episode, Planetary Radio, if you want to learn more. But, one of my friend's and my favorite ways of celebrating launches is to dress for the occasion. Between Hera and Europa Clipper, it's time to pull out all those cool space ties and dresses. If you'd like to join in and show your space flair, you can consider joining NASA's Runway to Jupiter Style Challenge celebrating the Europa Clipper launch. Here's Ambre Trujillo, our digital community manager with the details. Hi, Ambre.

Ambre Trujillo: Hey, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: The Europa Clipper launch is so soon, and I'm in this mode where I'm just all nervous and excited. Are you feeling that too?

Ambre Trujillo: Oh, my gosh, I am getting butterflies in my stomach just thinking about the launch. I'm so ready. I'm so ready to see this be on its way.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right. And you're actually going to be in Florida for the launch, right?

Ambre Trujillo: Correct. Yeah, I'll be at Cape Canaveral. I'm gearing up with a couple other staff here at The Planetary Society and some members, so we're turning it into a little bit of a member meet and greet and, yeah, it'll be a lot of fun.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's great because my guest just now, Michael Kuppers from the Hera mission, is also going to be there for the Europa Clipper launch. So, who knows if you'll bump into each other, but either way, I feel like this is going to be one of those moments that all the space community around the world should be celebrating. And whenever I get really excited about one of these things or I'm at a space event, something that I like to do, and I know you like to do too, is theme your outfits around space. Why do you feel like that's such a fun thing to do in those moments?

Ambre Trujillo: Oh, gosh. So, it's not only a fun thing, but it's a productive thing for me. Sometimes I just don't know what to wear at conferences or these space events, and it really helps me creatively to be like, "Okay, what is the theme of this event or this conference?" You know what I mean? So, if it's about the Artemis program, I'll be like, "Okay, what grays do I have? What layers can I put into this in order to make this fun?" And nobody else really knows that I'm doing that. It's just something that I do because it helps my brain just be like, "Pick an outfit."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: People can't see it because these are audio only recordings. But whenever I'm doing interviews with people, I'm always wearing some jewelry or piece of clothing that kind of matches the theme. So, I got a whole bunch of different space necklaces for all the different events, and I'll definitely be probably wearing my JWST Jupiter for this one.

Ambre Trujillo: Oh, wait, I love that. I had no idea, and I wish I was better with jewelry. I don't have really any jewelry at all, and there's so many cool jewelry options out there, so maybe that's my next endeavor.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, something I did was I got magnetic swappable jewelry, I believe I got my necklace, my two necklace sets from STARtorialist. They have this great necklace that you can just swap out the space image, so I just change them.

Ambre Trujillo: Oh, my gosh, that is brilliant. I have to look into that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right? So smart.

Ambre Trujillo: Yeah, that's not something that is definitely for me.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, it sounds like NASA's caught onto the fact that this is a really popular thing in the space community, which is why they're launching this Runway to Jupiter Style Challenge in honor of Europa Clipper. What is this challenge and how can people participate?

Ambre Trujillo: The challenge for anybody that goes onto social media often, they know that there's trends and there's challenges that people just do on social media. So, NASA is doing their own style challenge, and what it is is in order to inspire people and get people in the spirit of the Europa Clipper launch, they want people to express their creativity through style. So, it could be through makeup, accessories, clothes, your nails, whatever it is. You can bring in different elements. It's not just the colors of Jupiter and Europa that are different ways that you can bring in these elements into your style, but it's also the features of Jupiter and Europa, the icy kind of like ragged surface of Europa and the flowy atmosphere of Jupiter, you can bring that into your style. You can bring the weather conditions. It's really cold, so how can you do that? And it's just a really, really fun way to be able to bridge that art in with this launch, and that's something that I really love to do. I love to find different ways to bridge the two together. So, this is just a really fun challenge, and there's different ways for people to participate. The best way is to probably go on their website. They have a really great creative brief, basically just letting people know exactly the colors and a mood board to get you inspired. But yeah, it's a super simple challenge. All you have to do is use your creativity and see what you can build.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And then, how do people actually submit their images?

Ambre Trujillo: So, you do this through social media, any social media platform, and by doing the #RunwayToJupiter, NASA can find it. Once, you do that hashtag, you're just included with all these other submissions, and you have the opportunity. NASA might share your image on their social media channels or even during the Europa Clipper launch program, they might even share it there. So, it's just a really cool, fun way to get in the spirit of the Europa Clipper launch.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, whenever I think of space-inspired outfits, I always think of you because I know on your social media you like to share these videos of you dressing up as certain moons and that kind of thing so-

Ambre Trujillo: No, oh.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... I know that you made one for this occasion. What was your take on this runway challenge?

Ambre Trujillo: Yeah, so I looked for some of my favorite images of Europa and Jupiter, and I found three of each. And what I did is, I personally took the colors, and I looked at my wardrobe. One thing that NASA does encourage people, which I think is really great, is using what you have, right? Instead of going out and buying things, one of the best things that you can do to be creative is look at what you have and how can you create these looks. Luckily, for me, my wardrobe is mostly fall colors, and Europa and Jupiter both give fall vibes, like the autumn vibes. So, it was fairly easy for me to do it, but I just brought the main colors in from Jupiter and Europa, and I incorporated different pieces, skirts and shirts, and if I had a jacket or a belt, and it was really fun. I really enjoy figuring out outfits according to planets and moons and even spacecraft.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: This is a nerdy thing for me to say. Not that everything out of my mouth isn't nerdy, but I like designing space press-on nails. That way I can reuse them for other things. So, I've got a whole JWST series of them, but I was thinking of trying to replicate those cracks on Europa because I feel like that's a really cool texture.

Ambre Trujillo: Oh, yeah, for sure. I have to say, you are one of the most creative people that I know. You're really good at just like, even your glasses, if you've never seen Sarah in person, she always has fun glasses on. And your jewelry and everything else, you're just very, very creative. So, I have to see these press-on nails because that sounds so fun. I don't know if I have the art capabilities to be able to draw something like that, but that sounds like something that would be fun to experiment with.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'm very lucky. My mom was an art teacher for a long time, so I learned from her wonderful painting skills, but I also like to do something where sometimes it's really hard to convey the complexity of a space look and just makeup. So, sometimes I use face painting to try to get those finer details-

Ambre Trujillo: Oh, wow.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... so I was thinking before, the Europa Clipper launch should be really cool to, I don't know, just practice around with maybe some Jupiter swirls or something Europa inspired, but we'll see. I'll pull out all my glitters and my paints this weekend.

Ambre Trujillo: Yeah, that's so fun. Yeah, as I mentioned on the NASA website, they really encourage the different colors. They have the palette that you can use, and there's a lot of metallics and shimmeries and stuff like that, so I wish I knew makeup more because that would be really, really fun. So, if you do it, I'm very excited to see what you create.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'll take a whole bunch of pictures and share them and participate because I feel like... I mean, we've been waiting for this mission for so long, and the people working on this spacecraft to dedicate decades of their lives to it, and we're at me working on that mission, I think it would mean a lot to me to see how much it inspired people just to be there and to love this thing but also to go that extra step and dress up and celebrate because, come on, this is something we've been working to as a species for ages.

Ambre Trujillo: A lot of people, the reason that they get into these things is because they want to inspire people. So, to see people emulate that into their own creativity is really beautiful to see. And I've seen a couple images where people have crocheted their own outfits with a little bit of a Europa or Jupiter. Yeah, it's beautiful to see when people get excited because this is such an amazing, groundbreaking mission that we're about to embark on. And if anything, if people don't know what it is, if they see you and they're like, "Hey, why are you wearing these colors? Why are you wearing this thing?" It sparks a conversation, and that's what NASA wants to do as well, I'm assuming, with this challenge is if people don't know what Europa Clipper is, it's an opportunity to spark a conversation about how humans are trying to find themselves in the Solar System, and it's just so beautiful. So, I love this challenge. It was a great idea by NASA, and I keep checking the hashtag to see what other people have uploaded because it's just fun to see.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. Well, if anybody listening participates, we're going to be looking online at this hashtag, but also feel free to put those images in our member community if you're a Planetary Society member or you can just straight email them to us at our Planetary Radio email. We'd love to share them on the website for the Europa Clipper launch because it's a really cool and fun moment. So, what is the deadline for submission on this challenge?

Ambre Trujillo: So, it's launch day for Europa Clipper, which is October 10th. So, get your outfits together, your jewelry together, put it all together, get it on social media before October 10th, and possibly NASA might share it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks so much, Ambre. I'm looking forward to seeing your video online, and I'll share all my images when I'm done doing my crazy look.

Ambre Trujillo: I'm so excited. I look forward to it. Thank you, Sarah, for having me.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Before we move on to What's Up, I want to give everyone a heads-up that there's currently an opportunity to observe C/2023 A3. That's Comet Tsuchinshan-Atlas. We forgot to mention it in What's Up, so I'm going to add The Planetary Society's new article on how you can catch that comment on the show page for this episode. And now, it's time for What's Up with Dr. Bruce Betts, our chief scientist at The Planetary Society. He'll have more on the possible meteor shower created by the DART impact. Hey, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hey, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How you doing?

Bruce Betts: Oh, spiffy-keen wonderful, hunky-dory as well, I don't know.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I don't know.

Bruce Betts: [inaudible 00:55:32]?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Anytime we're in one of those months where it's like a bunch of space missions that I really care about are all going up, it's that tension in the air but also that excitement. You know?

Bruce Betts: Yes. Yes, I do know.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So many of our board members and our team members are going to be at the Europa Clipper launch. But in the meantime, by the time people are listening to this episode, we're going to be right out just a couple days from the launch of this Hera mission that we've been talking about. The DART, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test, DART mission was my first rocket launch, so I'm hoping the second rocket launch of this kind of saga does really well.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, we're all hoping that for Europa Clipper and Hera. They're good stuff.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I've spoken to so many people that have worked on this entire mission arc, both from the United States and from Europe, and we always knew that we hit Dimorphos really, really, really hard, but the fact that we hit it so hard that there might actually be the first human-caused meteor shower in history is a little bonkers to me. I know that you're a little skeptical whether or not we'll see it, but at the same time, that's a cool idea.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, it is. And I'm skeptical of everything, so you always have to take that into account. It's a scientist's crankiness.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Are you saying I should be skeptical of your skepticism?

Bruce Betts: Yes. Strangely, I guess I was saying that. Well, how the layers of skepticalicity are just incredible. Ooh, that'll be an album name.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Skepticalicity.

Bruce Betts: Okay, I'm getting distracted. Yes, that is quite fascinating that we might cause the first human-caused meteor shower. Now, we have caused plenty of stuff to re-enter the atmosphere as our artificial meteors, but this would be the first time we have rocky stuff that we blasted off something to do that, at least as far as I know. I can't think what else it would be. Yeah. So apparently, look, says we might get a meteor shower in 2034.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Where and when do you think we might be able to see it, if we actually get to see it?

Bruce Betts: If it's visible? Well, if it happens, then it's mostly in the Southern Hemisphere. It's a good Southern Hemisphere thing hitting that part of the planet, and the prediction is you'd have mostly small stuff. We might have things as big as the size of a softball, which would cause one heck of a bright meteor, but then not make it to the surface presumably.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I remember when I was a child, I was watching the Geminid meteor shower, and there was a meteor that was so bright it streaked across the sky, and it literally kind of temporarily burnt my retina. All I could see was that streak through my vision.

Bruce Betts: Oh, that's so cool.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's what I'm imagining here, something the size of a softball.

Bruce Betts: Oh, I never had my retina burned by a meteor. I've tried so many times.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Just got to watch more of them. You got to be there in the Southern Hemisphere in May 2034 is What's Up.

Bruce Betts: That's a fireball.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It was so cool, man. And I've seen some cool bolide explosions, things like that but, I mean, to be clear, on average, you're not getting softball-size objects during meteor showers, right? I mean, it can happen, but what is the average size of these objects?

Bruce Betts: Right. Now, typical is kind of sand size, dust size, even dust sand, maybe up to the size of a pea to use our standard vegetable measuring system.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Are there any other meteor showers in May that people should be aware of? I don't want people to confuse these two things because it feels like it would be really special to know.

Bruce Betts: I've got a few years to work it out. Yes, the Eta Aquariids, so I try to make sure I pronounce all these perfectly, is a pretty strong shower for, interestingly, the Southern Hemisphere. So that usually peaks in very early May, kind of fourth, fifth type time. I mean, it's an average-ish, I said strong but it's average-ish, so maybe 10 to 30 meteors per hour from a DART site. So, I'm not sure what they're predicting with this or if they made a prediction.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I love meteor showers. It's probably just... She's my childhood time, but I imagine as we get better at planetary defense, there's going to be more and more of these human-caused meteor showers, and we'll have even more to look forward to, that and all of the satellites crashing into our atmosphere to someday.

Bruce Betts: Well, yeah, that's starting. And thanks to certain groups, there are lots more that will be crashing into the atmosphere.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh, really?

Bruce Betts: They make some very nice meteors.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, you and me, Bruce, Southern Hemisphere, 2034, let's go.

Bruce Betts: Road trip.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Road trip. That would be wonderful. I got to hit every continent on Earth before I kick the bucket. So, I feel like most of the reason I'll end up in other countries to plan out my life plans is around these cool space events.

Bruce Betts: Well, I'm sure everyone wants to know. How many have you taken down, so far?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I've been to every continent except for South America and Antarctica.

Bruce Betts: Oh, well, you're good.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. No, I'm making pretty good progress. I got to get down there, like visit Brazil or something, and then head on down to Antarctica and look for some meteorites or something.

Bruce Betts: Ooh, that would be cold.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It'd be cold but totally worth it.

Bruce Betts: Worth it. Yeah, that'd be neat. If you're interested, I've got a little bit of a fact for you. In fact, it's a [inaudible 01:01:14]. Did I surprise you?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So surprised. Didn't see it coming.

Bruce Betts: So, Hera and DART, well, DART in the past and Hera in the future, are visiting the system with Didymos and Dimorphos. Dimorphos is the one that the asteroid impacted by DART and causing this future meteor shower. Dimorphos is also the smallest asteroid that we have visited with a spacecraft, and it's about the length of the height of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Wow.

Bruce Betts: About 150 meters-ish. So yeah, it's not shaped like a pyramid, but it's shaped like a potato with cornflakes on it, which is a pretty standard description in the technical literature, I'm sure.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's a good way to think about it, though. In my travels of the world, I've been to see the great pyramids in Egypt, so that does actually give me a good mental image, and that's pretty small. Well, knowing your passion for identifying places around the world, I know you like to do a lot of international trivia of that sort.

Bruce Betts: I do. And I'm a little behind, but I'm a big fan of GeoGuessr and figuring out where you are when you plop down in a Google Street View and figuring out where you are from the clues.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Just in case you ever fall out of orbit and need to immediately figure out where you are based on context clues.

Bruce Betts: Exactly.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right?

Bruce Betts: It's important.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: You never know.

Bruce Betts: Hey, it actually comes up. You'll see pictures on the news or something, and you're like, "Oh, wait. Look at that crosswalk sign. It's got eight stripes. That must be from Spain. We're going to hear about Spain." It's practical kind of information that you learn.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: One of these days, people will have to have a GeoGuessr for Mars or something. People in this crater love to use five stripes in order to signify danger, but people over here in the canyon system, man, they're all about pentagons.

Bruce Betts: I mean, you could do it now. It'd be a lot of red dirt and rocks, but we really haven't been in that many places on the ground, so...

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's true. I could tell by this sort of tracks that this is Jezero Crater versus Gale Crater.

Bruce Betts: Look, it's dragging a wheel. Ah, spirit.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's awesome. We need to make this. Right now, I would play that.

Bruce Betts: I would too. Hey, everybody. Gone through looking up the night sky and think about how many stripes you would put on your crosswalk sign. Yeah? Yeah, sure. Thank you and good night.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with The Planetary Society team as we update you on how the Hera launch went. And take a moment to reflect on the role The Planetary Society and Space Advocates have played in supporting the Europa Clipper mission. If you love the show, you can get Planetary Radio t-shirts at planetary.org/shop along with lots of other cool spacey merchandise. Help others discover the passion, beauty, and joy of space science and exploration by leaving your review or a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day but helps other curious minds find their place in space through Planetary Radio. You can also send us your space, thoughts, questions, and poetry at our email at [email protected]. Or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the Planetary Radio space in our member community app. I would love to see your Europa Clipper or Hera-themed outfits. Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California and is made possible by our asteroid-loving members. You can join us and help support missions like Hera and Europa Clipper at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor, Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. And until next week, ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth