Planetary Radio • Oct 23, 2024

Europa Clipper blasts off: How the mission team weathered Hurricane Milton

On This Episode

Bob Pappalardo

Europa Clipper Mission Project Scientist for Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Neil deGrasse Tyson

Astrophysicist and Director, Hayden Planetarium

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

NASA's Europa Clipper mission launched on Monday, Oct. 14, 2024, embarking on a journey to explore Jupiter's icy moon, Europa. This week, Planetary Radio welcomes Bob Pappalardo, the mission's project scientist, who recounts the team's dramatic encounter with Hurricane Milton before their triumphant launch. Plus, get a sneak peek at The Planetary Society's upcoming collaboration with StarTalk as Neil deGrasse Tyson, astrophysicist and director of the Hayden Planetarium, visits The Planetary Society's headquarters. As always, Bruce Betts wraps up with What's Up, featuring a beautiful member-submitted poem and an intriguing random space fact.

Related Links

- Europa Clipper launches on its journey to Jupiter’s icy moon

- Europa Clipper, a mission to Jupiter's icy moon

- Could Europa Clipper find life?

- Europa Clipper: A mission backed by advocates

- Planetary Radio: Europa in reflection: A compilation of two decades

- Planetary Radio: Clipper’s champions: Space advocates and the fight for a mission to Europa

- Planetary Radio: Europa Clipper's message in a bottle

- The music of Abby Travis

- StarTalk Radio

- Planetary Radio: Radiolab helps name a quasi-moon of Venus

- Planetary Radio: The nova and the naming contest

- Earth’s quasi-moons, minimoons, and ghost moons

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Europa Clipper is on its way to Jupiter this week on Planetary Radio.

I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. NASA's Europa Clipper mission blasted off on Monday, October 14th, 2024, on an epic mission to investigate Europa. It's a moon of Jupiter with a potentially habitable subsurface ocean. This week, we hear the harrowing and triumphant tale of the launch from Bob Pappalardo, the mission's project scientist. He'll share how their team navigated some technical issues and Hurricane Milton.

Then we look forward to The Planetary Society's upcoming collaboration with StarTalk as Neil deGrasse Tyson, the director of the Hayden Planetarium in New York, visits our headquarters in Pasadena, California.

Finally, Bruce Betts joins me for What's Up, a beautiful member-submitted poem, and a new Random Space Fact.

If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it.

Before we jump into the Europa Clipper team's heroic tale, I've got a fun update from a story that we've been covering for the past few months. In April, we invited Latif Nasser onto our show. He's one of the co-hosts of Radiolab podcast. He told us the story of how a typo on a space poster in his kid's bedroom led to the official naming of a quasi-moon of Venus called Zoozve. He returned in June to share the new collaboration between Radiolab and the International Astronomical Union, or the IAU. They created a public naming contest for a quasi-moon of Earth that I know a lot of our listeners participated in. Quasi-moons are these really interesting objects that appear to orbit a planet much like a moon does, but they actually orbit the sun. It's a really complicated scenario, and I'll leave some resources on the website for this episode of Planetary Radio in case you want to learn more. Those will be at planetary.org/radio.

But people all over the world have submitted their mythological name suggestions for this quasi-moon of Earth. And now that the submissions are closed, I'm happy to announce that Bill Nye, our CEO, and I will both be on the panel to help whittle down the names for the public final vote. I'm really looking forward to getting into some of these names and learning more about their beautiful mythologies. I'll update you in the coming weeks that you can participate in the final vote and help name one of our planet's temporary moon friends.

And now for the moment space fans have been waiting years for, the launch of Europa Clipper. On Monday, October 14th, 2024, NASA's Europa Clipper spacecraft blasted off from Cape Canaveral, Florida. This compilation of moments from the launch was produced by our friends over at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Speaker 2: Live at NASA's Kennedy Space Center for NASA's Europa Clipper Mission, a nearly two-billion-mile five-and-a-half-year journey to Jupiter's icy ocean moon.

Speaker 3: And liftoff. Liftoff from Falcon Heavy with Europa Clipper, unveiling the mysteries of an enormous ocean lurking beneath the icy crust of Jupiter's moon Europa.

Speaker 4: Side booster separation confirmed.

Speaker 5: Faring is separated and those will be recovered by SpaceX's own recovery ship, GO Cosmos.

Speaker 3: This is a big moment for the program, for NASA, APL, and JPL. Let's watch.

Speaker 6: Europa Clipper separation confirmed.

Speaker 3: And there you go. NASA's Europa Clipper probe embarking on a long-awaited mission to study Jupiter's icy moon Europa. And what a sight.

Speaker 2: And now they wait for acquisition of signal.

Speaker 3: And I believe we have it. There it is. Confirmation of signal from the spacecraft Europa Clipper.

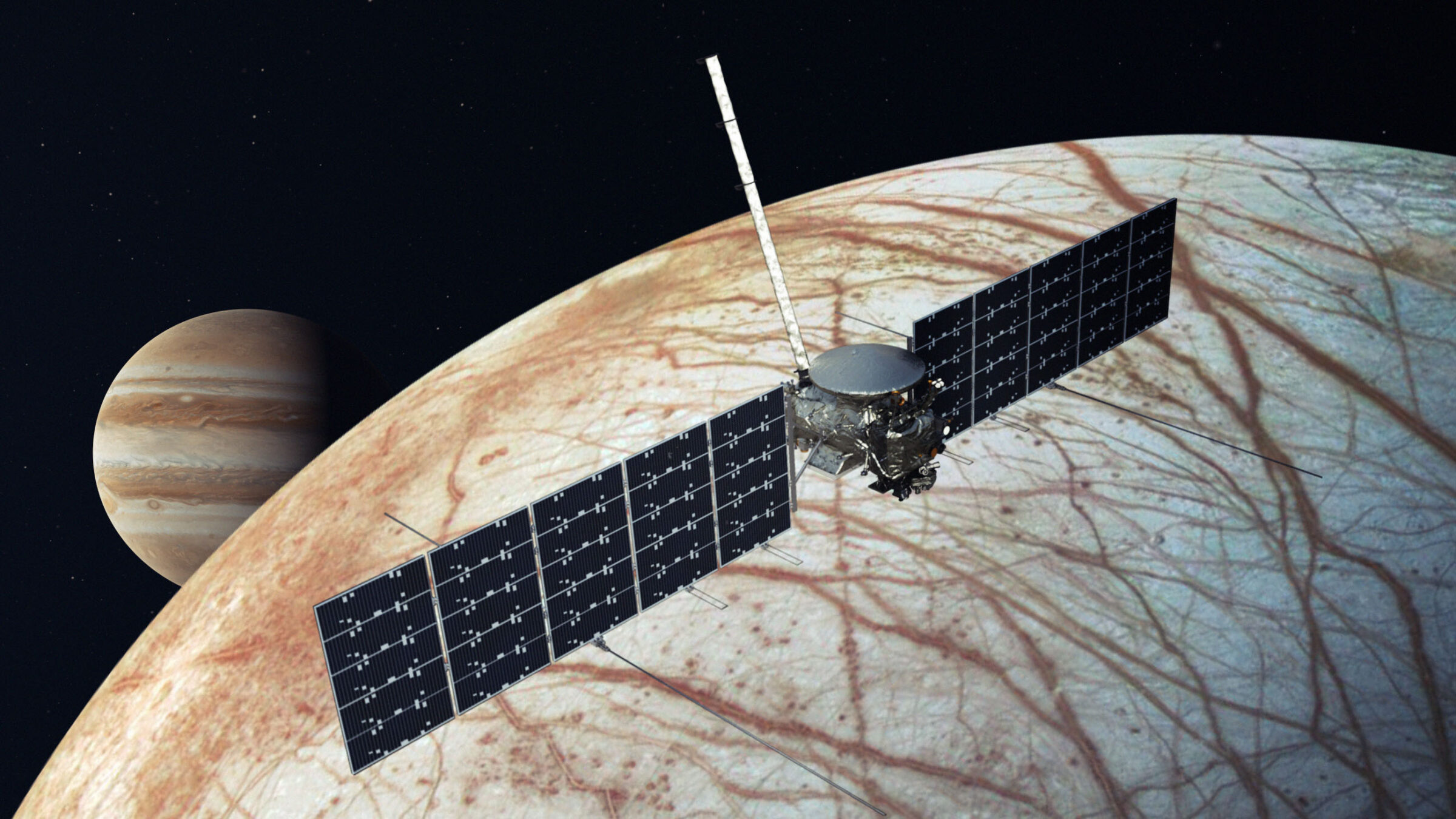

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Europa Clipper is the first dedicated mission to explore a world with a global ocean other than Earth. While it won't be detecting life directly, it's going to perform a bunch of close flybys of Europa. They'll teach us more about its icy shell, its ocean, the composition, and its geology. It's the largest spacecraft that NASA has ever built for a planetary mission, and it was produced as a partnership between the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. It has been a colossal effort on the part of thousands of people to make this mission possible, from the planetary scientists who made it a priority in the Planetary Science Decadal Survey, not once, but twice, to the advocates who got the mission the funding it deserves, and of course the scientists and engineers that had to do the hard work to actually put together this beloved spacecraft.

After all of this effort, the mission team and space fans gathered in Florida to see the spacecraft off. Unfortunately, all of that got waylaid by Mother Nature herself. Hurricane Milton, which was a massive Category 5 hurricane at one point, had Kennedy Space Center and all of its launch facilities in its sights. Bob Pappalardo, who is a great friend of the show and project scientist for Europa Clipper at JPL, joined me over the weekend. He told me all about how his team weathered this storm and launched this historic mission to Europa.

Hey, Bob. Congratulations.

Bob Pappalardo: Thank you. Thank you. Quite a week it was.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Really though, and not just a week. It has been a saga since we last spoke a few months back and then so many things happened that put this launch in this kind of limbo for a while, so I'm sure it's really relieving now that it's out there in space on its way to Jupiter.

Bob Pappalardo: Yeah, it seemed like our spacecraft didn't want to leave us.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How long have you been working on this spacecraft? It's been so long.

Bob Pappalardo: Well, the mission got started in 2015. Building of the spacecraft itself and integration of the instruments, probably a few years now.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. Well, we've kind of covered the saga over the last few weeks of first there was the issue with the SpaceX launch vehicle. You ended up going up on a Falcon Heavy, but the Falcon 9 had an issue right off the bat. So right there we had to wait for the FAA. And then here comes Hurricane Milton to make it even more intense. I know that you and a lot of your colleagues planned to be out there. What was that like when you heard the hurricane was oncoming? And did you guys all have to leave?

Bob Pappalardo: Well, it was pretty tough. At first, everything seemed fine. First got out there for a flight readiness review, and I got to see the encapsulated Clipper in its faring roll out of the clean room where it had been worked on and the solar arrays were incorporated. That was quite celebratory. Then I remember getting an email or something from team member and said, "Oh yeah, it's supposed to be rainy next week." Like, rainy? Yes, we hadn't heard that at our flight readiness review. And then yeah, people started talking about this storm brewing in the Gulf, or the conditions being right for a storm to brew in the Gulf, and possibly hurricane.

And as time went by, yeah, that became a hurricane that was targeting KSC. And we had a team meeting planned, science team meeting, most of the week as well. So we had planned alternate versions of our science team meeting if the launch didn't come off on the day planned. We didn't plan for a hurricane, but we had the flexibility to move things around.

And then as the forecasts were getting worse and worse, we had discussion of what to do about the science team meeting. There were already a lot of people there. We said, "Okay, we're going to assume people aren't going to continue to come to our meeting," and said so to folks, but the people who were there, I said, "Yeah, we'd still like to... Even if this is a hybrid meeting, we'd still like to be in person." We met the first day and everything was fine, on Tuesday of last week. But then it was clearly going to be a big storm the next day and we canceled. And then the storm was slowing down, so we canceled for Thursday.

And a lot of people were just gathering and having a good time in the hotel. We showed movies on the screen. Because there's a lot of kids there, a lot of families. I like to put everything in terms of Star Trek analogies, so I wasn't used to being on the Enterprise-D at our team meeting, where we had the families there as well.

So it was actually, I think, prior day where a colleague called and said, "You know, there's a chance you're going to be in the front right quadrant of a hurricane." Like, "Yeah." "Well, that's the quadrant that spawns tornadoes." And there was no talk of tornadoes on the news. I was watching very carefully and keeping up with all of the emergency info. And then Wednesday afternoon the tornado warnings started coming and creeping up from the south toward us. So I went downstairs, make sure everything's good. And again, people are playing games and talking and watching movies in the ballroom. And I asked the hotel staff, "Where's the right place to be in case of tornadoes? Is it the ballroom, is it inner building, or a stairwell?" And so then when all the warnings went off on people's phones, calmly asked people to please come into the ballroom and everyone was now in there who was downstairs. And then the palm trees outside started blowing sideways and it was getting darker and darker. The hotel staff's like, "Inside. Inside." And we learned that evening that the bank building across the street had its roof blown off.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh my gosh.

Bob Pappalardo: And part of the parking garage metal between our building and the next was tossed around and light poles. It wasn't until a couple of days later I learned that indeed our hotel had been nipped and had some damage as well.

So that was nerve-racking. Power went out that night and we ended up moving everyone to another hotel, same brand, not far away, on Thursday when things quieted down, and our whole meeting moved as well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. Oh my gosh.

Bob Pappalardo: We picked up again on Friday and had some good conversations, but it was pretty nerve-racking. And then the weather cleared and the reviews picked up again, and our project manager mentioned, yeah, sometimes after... most of the time after a hurricane, the weather can be really clear and beautiful, and it was. And we ended up with a perfect launch day on Monday.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That is such an emotional whirlwind right there. I mean, you already had so much on your plate just with this mission and now you're in this scenario where you're responsible for making sure all these families are okay in this scenario, trying to keep it together in the middle of tornadoes and hurricanes. My gosh, it must have been such a weird kind of whiplash moment to finally have the clear skies and have that catharsis of actually seeing it launch after all of this tension.

Bob Pappalardo: Yeah, yeah. It was incredible. I'd seen a couple of small launches. Well, I saw a small launch and then I felt a small launch up here at Vandenberg, because it launched in the fog, and this was different. We gathered in kind of VIP area and much of the team was out in the stands there, watching the event. And it was more than I had imagined. Things quieted down as the final countdown occurred and we watched and people cheered, and then when the roar, the shockwave hit and the light was as bright as burning magnesium, couldn't even look at it, it changed my impression of this. There was so much power in that launch, it just became something different. It was almost as much of a spectacle as seeing a solar eclipse, where it's like, oh my God, what is happening here? We are tossing this thing off of our planet with this enormous Falcon Heavy rocket. It was just more than I can express. People were quiet and just mouthing, "Oh my God," all around. It was something to experience.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: There are some moments that you can try to prepare yourself for emotionally, but until you're standing in it, there's really no way to convey what that's like. I've never seen a Falcon Heavy myself, but after speaking with my co-workers about their impressions of it during the LightSail 2 launch, you can tell that it changed them and their entire perception of what we're doing here, trying to do space exploration. It really gets to the visceral nature. We're literally strapping some of the greatest hopes of humanity onto a controlled bomb and firing it off of our planet.

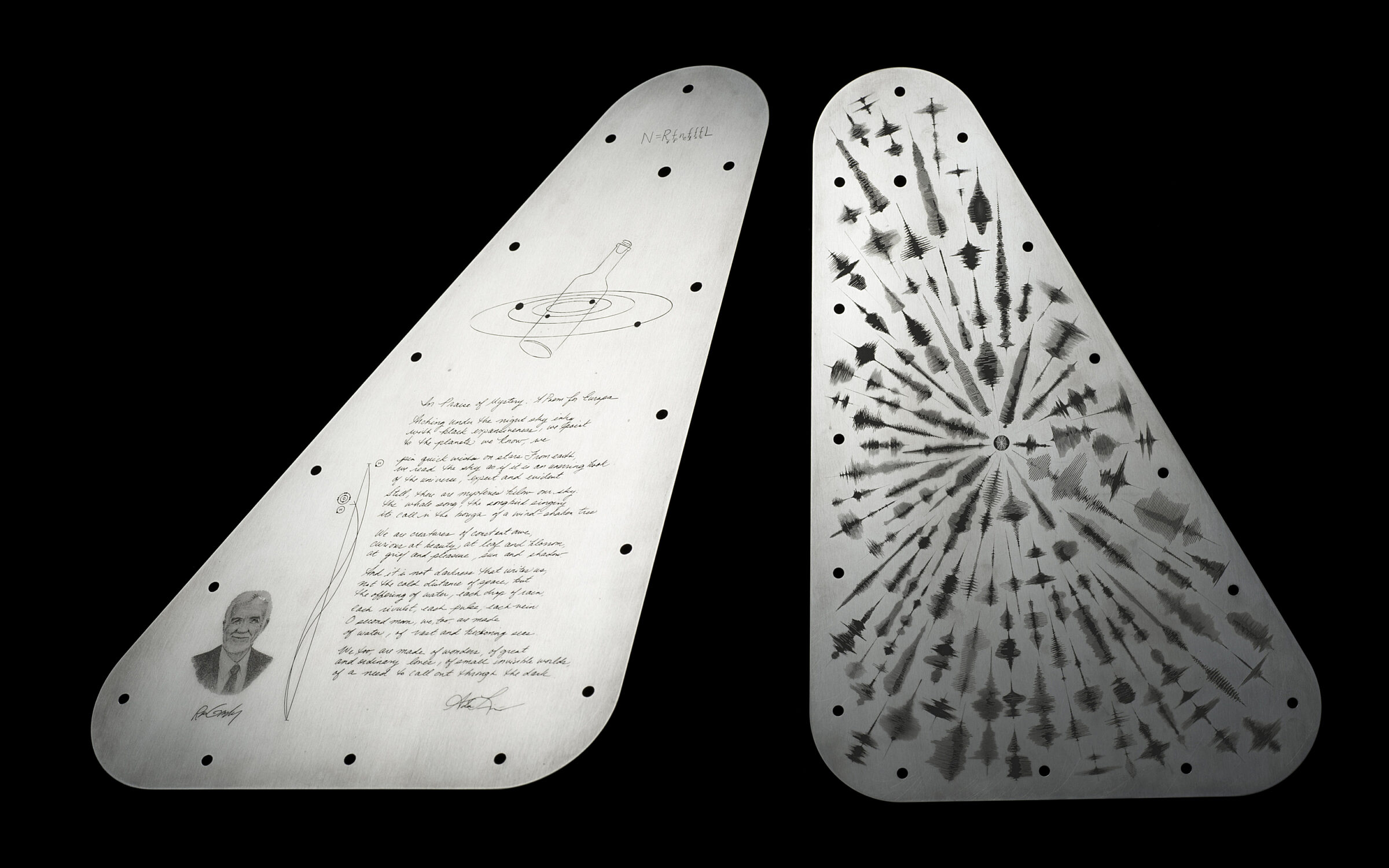

Bob Pappalardo: And of course, leading up to that and seeing the rocket the prior day, there was a feeling of pride and excitement. And that night, the night before the launch, we had a big family and friends event, and Ada Limón, the US Poet Laureate, read her poem for Europa, and it was wonderful. She was there at the launch as well. But yeah, I feel like nothing could have really prepared me, not just for the emotion of seeing this craft that we had spent years and years and had concepts going back 25 or more years actually launch, but the power involved in that launch being just so overwhelming. Yeah, it was something.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. Because of the quick notification that we were just a day later going to be seeing this launch, we had all hoped at The Planetary Society that those of us who live near headquarters could get together in headquarters and actually watch it together. And instead, we still had our live event in our member community. We all got to chat about it together. But I was just at home watching it on the screen, and even then, seeing Ada Limón on screen during that, give her feelings on reading the poem, I got emotional all over again and I wasn't even there.

What did you do for the rest of the day after that? I personally think I would have zero capacity to do anything else except maybe stare at the ocean and have tea or something.

Bob Pappalardo: Yeah. Well, I had a brief appearance on the live NASA feed, which was nice. And kind of recover. And it had been so exhausting for a week in the hurricane and the tornado. A bunch of us did gather in a local park and just talked and celebrated and it was a chance to meet people on the project who you didn't necessarily know and chat. But yeah, then it was go back and have some dinner and collapse asleep.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Although I know there are several members of the team that I hope to bring onto the show this week, but a lot of them immediately had to go to the International Astronautical Conference over in Milan. So a bunch of team members already had to go straight from this harrowing emotional ride right into trying to keep it together at a conference.

Bob Pappalardo: No, I would not have been able to do that. So the launch was Monday, we're recording on Saturday. I'm just coming back to where I can have this kind of conversation, and then I give a presentation to the Committee on Astrobiology and Planetary Science on Monday and talk about the launch a little bit, and then I'm off to vacation for a week because it's just got to clear out all of the stress and all the excitement. Oh, and it was wonderful last couple of days slowly catching up with the social media and wonderful articles that have come out and team members being interviewed on Radiolab and Science Friday and in The New Yorker. It's just fantastic to see all the excitement about Europa.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've been getting it on our side as well. There's just such a realization of the magnitude of this mission that our media team and everyone involved has just been getting called in to do all these media spots. I think it's easy for us as the scientific community who are aware of these missions to feel that buildup, but a lot of people in the public don't hear about these missions until literally the day that they're launching, and suddenly just the flurry of understanding of the magnitude of what this mission really means just hits the public. I'm sure that in the midst of all of this, that's one extra thing you've got to wrap your brain around. How do I then present myself in this scenario to the world as a representative of this mission?

Bob Pappalardo: It's nice to be just out at the store yesterday and someone saw my T-shirt and said, "Oh, you work on Europa Clipper?" "Yeah." Their relative did to, given that we're not far from JPL here. But yeah, it's really nice that people now know it. It's becoming part of the vocabulary. What we've been living with for years is now out there and the public saying, "Oh, great. This is something we're looking forward to."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Is the rest of the team also going to take some vacations after this?

Bob Pappalardo: Oh, yeah. I went in... What day was it? I forget. Wednesday or Thursday this week, and the halls were pretty empty, and I was glad to see that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. After this whole thing. And thinking about it too, since last we spoke, there were some other issues that you guys had with the spacecraft, particularly with the transistors on board. You realized that there were some issues there. How did that scenario play out?

Bob Pappalardo: Yeah, that was an enormous effort. We learned in early May that some of the transistors, a lot of the transistors, might not be as radiation hard as we expected. And spacecraft was built, right? Taking it apart would be an enormous effort and an expensive effort and cause delay, and delays are money. And there began a round the clock test program at four different locations around the country, and even people internationally, looking for spare parts that we could test in radiation facilities. Every circuit that could have been affected was examined and every spare part we could get a hold of was tested, and we found that it came down to only a few subsystems and instruments would potentially be affected, and those we could address mostly by targeting some heating to those areas, which will allow those parts to make it through the nominal mission.

So it was quite a relief. And we didn't know until just the last week going into a big NASA review how that was going to turn out. And as part of this, I was instrumental in an effort to look at what science we would get if we had to shorten the mission and essentially do two thirds of the length of the mission. Could we take more data faster? Could we put together a trajectory that experienced less radiation? Could we use the instruments in smart ways to conserve, if you'd like, against the radiation environment? Boy, that was tough, and that was months of effort and intense work that was not expected. And fortunately, we came out in a good place, and there'll be continued testing and modeling to make sure that things are going to work out okay.

And one other piece of this is that our flight system manager had the idea that we need to know exactly how these parts were acting in flight to make sure they matched our predictions. And he started designing with his team what became called the canary box, a box that would carry many of these parts, duplicates of parts that are elsewhere in the spacecraft and experience the same radiation environment, but now we could monitor this subset of parts to understand are they degrading and at what rate? So that we'll know when we're flying what the parts in the spacecraft are doing. So that was brilliant. And three months from conception to being installed and tested on the spacecraft, it was amazing.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That is amazing. Oh my gosh. I'm so impressed with you and your team. It's ridiculous what you guys have been through. And I think, if I'm correct, ESA's Juice Mission also is using the same transistors, so I'm sure that that knowledge and that kind of research you put into trying to figure out this issue for Europa Clipper could be very useful for their team as well.

Bob Pappalardo: I believe they're using some of the same. I don't know that, because we were so focused on the Clipper problem. And the challenge here is that there are export control regulations. We can't just go talk to Juice and say, "Here's what we found." So those conversations are happening behind the scenes at the NASA level to understand what information can be conveyed about these parts.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, it's going to be a few years until you reach Jupiter, so there's time to take a breath and share that knowledge as both missions get there. And the original plan was for Europa Clipper to go up on an SLS rocket back in the day. It had to be changed to a Falcon Heavy, which necessarily changed the timeline for actually reaching Jupiter. Is it still the case that we're going to be reaching Jupiter with Europa Clipper before Juice arrives?

Bob Pappalardo: Yes, because the Falcon Heavy with such powerful rocket and because we're using a Mars and then Earth gravity assist that we actually get there first. And we're meeting regularly with the Juice folks. We have a group that is composed of Europa Clipper scientists and Juice scientists who are talking in a grassroots effort of what can be gained by having two spacecraft in the Jupiter system at the same time. There's a lot of wonderful science that we can do together by just communicating.

So for example, Juice ultimately ends up in Ganymede orbit, and then we're out there making flybys of Europa. So we are recording the Jupiter magnetosphere while they are examining the Ganymede magnetosphere. Remember, because Ganymede has its own dynamo and its own little magnetospheric bubble inside of Jupiter's. If Juice records some fluctuations that they think might relate to the Jovian magnetosphere, well, we're in the Jovian magnetosphere and then we can convey what we found, and that's going to make some wonderful joint science.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That would be really useful considering that they've been trying to figure out that interaction between the magnetosphere of Jupiter and Ganymede through Juno data and other things. But combining this all together is going to give us such a wonderful picture of all of these moons together. It's going to be really interesting to see because the only other world I can think of where we have this many missions and coordination is Mars, and seeing all of those missions work together has been ridiculous over the past 20 years. We're going to have this new age of Jupiter science.

Bob Pappalardo: Yeah. Yeah. It's just fantastic. And yeah, there's a real bond between the two missions, which is great and something we want to carry forward.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Wow. Well, after all of this, I hope that you have just the best vacation ever. And what are you and the team going to be doing in these next few years as you wait for it to actually reach the Jovian system?

Bob Pappalardo: Well, right now, so I said, "Oh, the halls were kind of empty when I went the other day." But we're now spread in two buildings, and I know in the other building there's a lot of people over there because that's the ops team. And there are daily meetings. There's one this morning. It's a Saturday but it doesn't matter. Spacecraft's flying. So we're essentially learning how to fly this spacecraft. What are its characteristics, it's thermal aspects? They tested rotating the solar arrays the other day. And then the team is gearing up for the Mars flyby. And we have a calibration there, so that'll be some of the first interesting data we see. Not specifically science data, but data that will be used to calibrate the thermal instrument. And an end-to-end test of the radar system. And then Mars is just about four months from now. And then the Earth flyby is about a year and a half after that. The Mars flyby is March 1st, 2025, and then the Earth flyby is in December of '26.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Are we going to get any cool images during those flybys? Because I know you're going to be testing systems. Is the camera system something you're going to be using for that?

Bob Pappalardo: We won't have the covers off the cameras yet, and for the infrared spectrometer, it's too warm, but we will test the thermal imager because there's a calibration issue with one of its bands. And this will help ensure that we can properly calibrate it by using it at Mars, a known target, a well-known target, so that we can properly have it calibrated when we get out to Europa.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I don't even work on the mission and I'm in the space of deep relief knowing it's out there after all of this. I recently had a conversation on the show with our Chief of Space Policy, Casey Dreier, all about how much advocacy it took, and the long saga of a dedicated Europa mission being at the top of the Planetary Science Decadal Survey twice before it ever actually got the funding that it needed. This has been just decades and decades in the coming from the moment that we first flew by and did all those Voyager images and Galileo. This is such a moment in human history and I don't know what I'm going to feel when we finally get there. And the data is going to be absolutely bonkers. Who knows what we're going to find at Europa? I mean, I know that this isn't a dedicated life-finding mission. We have to say that. But what it could teach us about the potential for life in the universe is just beyond anything I've seen since Cassini going and flying through those plumes at Enceladus.

Bob Pappalardo: The launch is such a huge deal and a catharsis and such a milestone. But of course, the big news happens when we get to Europa, ultimately Jupiter in 2030, and the first Europa flybys in 2031. And yeah, it's going to be incredible. It's going to change the way we think, not just of Europa, but ocean worlds in general, outer planet satellites that may have oceans within, and the process of tidal heating, and their composition, and their geology. It's going to open so many doors. And then, if we understand that Europa may have locations that could potentially support life, I sure hope that we will then in the future go there with a lander and literally search for signs of life.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I'm sure if we find that evidence there that people all over the world are going to be willing to rally to that cause, because even without that data, even without fully understanding Europa, even just The Planetary Society by itself, let alone all the rest of the scientific community, peppered Congress with almost 400,000 letters. Imagine what we could all do together if we had some evidence that there's some indication this could be a habitable moon. I can't even imagine the way that's going to light everyone across the world just on fire.

Bob Pappalardo: Yes. All I can say is yes, absolutely. That's the assumption, is that missions bring new questions and new missions, and we're getting closer to answering some of the biggest questions, including is there life elsewhere beyond Earth?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And even if there isn't, what a cool moon to go check out. I want to know what's going on with all those cracks. There's so much to be had there, even if it's not a living moon.

Bob Pappalardo: And sure, it's going to take five and a half years to get to Jupiter, but it'll go by.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Come on. On the scale of the universe, that's not even a blink.

Well, thanks so much for sharing this harrowing story and for everything you've done in service of this mission, but also for Planetary Radio. You've been coming onto the show for over a decade talking about this mission, and it's been really cool to see that entire arc, and wonderful to have this... not conclusion, but a moment of celebration in the middle of this saga with you. I really appreciate you spending time on a weekend to speak with me.

Bob Pappalardo: Well, thank you. I always enjoy the chance. And The Planetary Society members have been so supportive through the years, and the leadership of the group has as well. So just thank you and thanks to all out there.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Godspeed, Europa Clipper. Thanks so much, Bob.

Bob Pappalardo: Thank you. I appreciate it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I hope everyone on the Europa Clipper team gets the rest that they need to appreciate what they just accomplished. It's been a really wild few months, and years, honestly. So please join me in a small musical moment of celebration for everyone around the world that made Europa Clipper possible.

This song was sent to us by American musician and Planetary Society member Abby Travis. She's worked with many bands including The Go-Go's, The Bangles, Beck, and KMFDM, which was one of my favorite industrial bands when I was in college. She's a huge space fan and released a single called Europa to celebrate the mission's launch.

MUSIC: Europa, closer to mystery.

What treasures do you have in store?

Now I need you so much more.

Europa, waiting patiently.

When I was so sure of time.

And baby, your past is all that I can see.

Giddyup, the bulls are rough and they're filling my cup.

Watching you.

Now the skies will crystallize when the lightning has struck.

From the moon.

Giddyup, the bulls are rough and they're filling my cup.

Watching you.

Good sparks, you don't stop. You don't stop.

(singing).

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That takes me right back to the space rock of the seventies. I'll leave a link on this Planetary Radio page so you can listen to the whole song. Thanks so much for letting us share, Abby. We'll be right back after this short break.

Bill Nye: Greetings. Bill Nye here. NASA's budget just had the largest downturn in 15 years, which means we need your help. The US Congress approves NASA's annual budget, and with your support, we promote missions to space by keeping every member of Congress and their staff informed about the benefits of a robust space program. We want Congress to know that space exploration ensures our nation's goals in workforce technology, international relations, and space science.

Unfortunately, because of decreases in the NASA budget, layoffs have begun. Important missions are being delayed, some indefinitely. That's where you come in. Join our mission as a space advocate by making a gift today. Right now, when you donate, your gift will be matched up to $75,000 thanks to a generous Planetary Society member. With your support, we can make sure every representative and senator in D.C. understands why NASA is a critical part of US national policy. With the challenges NASA is facing, we need to make this investment today, so make your gift at planetary.org/takeaction. Thank you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Man, what a month. But the space party never stops here at The Planetary Society. With the European Space Agency's Hera and NASA Europa Clipper spacecraft launches in the rearview mirror, our communications team got to take a moment to hang out with our friends over at StarTalk. Their podcasts and shows are hosted by astrophysicist and Hayden Planetarium director Neil deGrasse Tyson. Along with his comic co-hosts, they talk all about astronomy and physics with their celebrity and scientist guests, including our CEO, Bill Nye the Science Guy. Neil used to be on our board of directors back in the day, and he and Bill are pretty good friends. I got a moment to speak with Neil about the only time we'd met prior to this, which was at the legendary San Diego Comic-Con.

Hey, Neil. Thanks for joining me.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Thanks for having me. Good to be at HQ in Pasadena for TPS.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, you used to be one of our board members. It's probably an interesting thing to come back here and be in this building again.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: When I was on the board, I was there primarily when the headquarters was still in grandma's house. There was some home on some side street of somewhere in Pasadena, and I was there during the transition to acquiring this building, to renting this building. But right around then is when I pulled off the board because I had other obligations.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I've only been able to drive by that building. It's really pretty from the outside, but there's a whole era of history in there that I haven't gotten to experience.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: It still looks like grandma's house, so it doesn't look like planetary future society space exploration. This facility has much more of that feeling, especially with the artifacts that don the walls. I mean, this is the right place, doing the right thing.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, this is a conversation I've wanted to have with you for about 12 years, because that was the last time and the only time we've met prior to this moment. It was at Comic-Con 2012. I met you at the Starship Smackdown panel.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Oh, I'd never heard of this. I'm not... I know about Comic-Con, and I've been a couple of times, but I'm not crazy Comic-Con person. And I was invited to this Smackdown, Starship Smackdown. It's the last thing scheduled over the entire Comic-Con. So people just, whatever energy they have left, they spend it there arguing the case for their favorite starship. And what I had not appreciated is you can make a poster, which they've done, of every single sci-fi starship that there's ever been in movies and... So it has the Millennium Falcon. It's got multiple Starship Enterprises from Star Trek. It's got the Death Star. Anything people were in in space is on this poster. And you can look at it and say, "Well, I remember that. Well, what did that do?" Or, "Was that good or bad?" Or, "Did that travel fast or slow? Was that susceptible or not? Did this one have good weaponry to defend itself or to attack?" So in the Smackdown, all of that gets argued. And in any given year, some new ship, not new necessarily, but newly argued ship rises up to win the day.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: The wild bit is that I stepped in there. I was actually hanging out with your daughter Miranda that day. Didn't know that she was your daughter until that exact day, which was insane. And I still have that exact poster, which was yours that you gave to me and signed when I went into that panel.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: The poster of all the ships?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Oh yeah. Oh, do you still have it? Excellent. Now, I don't know why I signed it because I had nothing to do with it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, you were just there. There was this moment where they asked, it was the original Enterprise versus the new refit Enterprise. They asked if anybody had anything to say about it, and here comes Neil deGrasse Tyson.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: I did make a point. I remember defending it. Do you think that carried the vote?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I honestly think it did. And then weeks later, friends of mine brought it up. They're like, "Did you see Neil deGrasse Tyson make this speech?" People posted it on YouTube.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Okay. Because I just stood up. I was in the audience. I wasn't on stage. They have people arguing on stage, because those are the pro and con or whatever. So then it goes to the audience, and then we all put in our two cents. But the only point I made, and I think this is true, that the original Starship Enterprise was the first ever spaceship to not have a destination. Think about that. Every other ship, you're building it to go there or to come back from here or it's a mission to that place. The Starship Enterprise was a mission to everywhere, not just a place. And that turned space into not a place with a destination. Space itself was the destination. And I thought that was transformative in our hearts and minds and our dreams, thereby elevating the Starship Enterprise to the status it deserves.

There was some fun arguments. People were wondering, which was faster, the original Starship Enterprise or that newly modeled one in the later movies, with the same crew. And someone argued, "Yeah, it's got better rockets. It's got better engines, of course. However, this is 20 years later, 30 years later. The entire crew is much heavier. So the same thrust is not going to create the acceleration." And the whole room is saying, "Yeah, you got a point." The fact that that could live as an authentic legitimate argument, I think is a sign of just how playfully geeky that session turned out to be.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'm never going to forget it because right immediately after that, I remember we were trying to get you out of there, get to your airplane, and I turned to you and I said, "I want to be a science communicator when I get through all this." I had just gotten my degree in astrophysics. I was working at a grocery store and I was trying to figure out my path through life. And I said, "Neil, I want to let you know that I think you're amazing." And you looked at me, you said, "No, Sarah, the universe is amazing."

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Right. I'm just a conduit to the cosmos for who... So is Bill Nye. We're just offering the universe to whoever has the bandwidth to receive the messages. And I'm not beating anybody on the head. I'm not twisting your arm. I'm just offering you things that I find to be particularly enchanting about the cosmos. So yeah, I don't take credit for things that are inherently amazing.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I wanted to thank you because that was one of those moments in my life where I had a dream. I didn't know how it was all going to pan out. But you told me to keep pursuing it. And now 12 years later, I'm now the new host of Planetary Radio. So, speaking to the host of StarTalk, this is a moment for me, Neil.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: Oh yeah. And plus, it's an honor to inherit something that already has legacy, and now there's a responsibility that you carry to bring that forward.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks for being one of the people that bolstered me through this, and I'm looking forward to hearing your episode of StarTalk with our Bill Nye.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: It's StarTalk about The Planetary Society. We're going to let the public know, at least through our channels, what's it about and where's it come from and where is it headed.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks so much, Neil. Let's go record this thing.

Neil deGrasse Tyson: All right. Let's do it now.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'll let you all know when that episode of StarTalk with Bill Nye is available. Before we close out this week's show with What's Up, I wanted to take a moment to thank everyone who wrote Casey and me to rewatch the 2013 movie Europa Report. Casey Dreier is our Chief of Space Policy, and a couple of weeks ago we had a passing chat about our hopes that this mission to Europa would create a bunch of new Europa-related science fiction. We honestly didn't remember much about the movie Europa Report at the time, and I got flooded with emails asking that we rewatch it and give it the credit that it deserves. So as requested, I rewatched the movie.

The film tells the fictional story of the first crewed mission to Europa. Unlike other classic science fiction films where the first explorers to deep space head to a place like Mars, these people head to Europa hoping that they can discover signs of life. The film is constructed from footage from the onboard cameras as the crew deals with the intense hardships of space exploration.

I won't critique the film's construction or give away the plot, but what I will say is that it's a movie about the commitment to exploration and the heroism of human space travelers. It asks us what we would be willing to give to discover life off of Earth. Sure, there are some wacky things in there, but I appreciate any movie that takes the time to semi-realistically depict space exploration, especially in the search for life. Thanks for the recommendation.

Now let's check in with Dr. Bruce Betts, the Chief Scientist of The Planetary Society, for What's Up. Hey, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hey, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know we kind of celebrated this last week, but we could finally, finally actually do our little dance. Europa Clipper's in space.

Bruce Betts: It's not only in space, it's where it's supposed to be, is my impression. It's super exciting. Do the super dance for me.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: You can't see it. I'm doing a little dance. But really though, I mean, ugh, the saga, the entire experience that Bob Pappalardo and all the people working on this mission.

Bruce Betts: Yes, Bob has spent a lot of years and a lot of stress and a lot of work as well as hundreds and hundreds if not thousands of other people to make this work. And it works so far, so that's awesome.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. Now we just got to wait all those years until it gets to Europa, but in the meantime, we've got plenty of other things we've got to advocate for, plenty of other space missions that we can be excited about.

Bruce Betts: There are a lot of space missions out there doing groovy stuff right now. Mars is nasty with them. The moon's getting nasty with them. Venus will be getting stuff and asteroids, asteroids, asteroids. So there's good stuff going on out there, and I've missed a number of things, not to mention space telescopes. Okay, back to you in the booth.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: This was one of those missions that we had to advocate for for quite a while. I mean, it was even one of the priorities of the Decadal Survey twice before we ever actually got that thing up there. And now we've got a dedicated mission. But now that we've done that, what's next? What worlds do you think deserve a dedicated mission after we've gone through this?

Bruce Betts: Well, of course the answer is all of them.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: All of them.

Bruce Betts: But what do you mean by dedicated mission? As opposed to an undedicated mission?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: As in like they're going to one target to focus on it, right? Juice, as an example, is going to the Jovian system, but it's going to be checking out multiple moons. It's not like they're dedicated to just one world.

Bruce Betts: No, but they're focused on just one world, which is Ganymede.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I guess that's true. Ganymede.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, no, they plan on doing an orbiter of Ganymede, I believe eventually. Correct me if I'm wrong.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. That's going to be really cool.

Bruce Betts: Ganymede is big, by the way. I never really knew that. Big. Bigger than-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's the biggest moon in the solar system, is that right?

Bruce Betts: Biggest moon in the solar system. It along with Titan or both bigger than Mercury. And it's got a lot of complex stuff going on. Anyways, neat place. Places that deserve missions. Well, Enceladus and the Saturn system in general. I mean, we had a lot of great stuff with Cassini-Huygens, unbelievable amount of wonderful data returned. But it also teased us, particularly with... They were focused on Titan, and they knew that was awesome, and it was, and it has Dragonfly headed out to it eventually.

But Enceladus turned out to be the surprise world that hey, there are plumes of ice and there could be... There's a subsurface ocean and there's probably rocky stuff. And so, like Europa, it's intriguing for the same reasons. And so, getting out to focus more on Enceladus will be a priority at some point. The Decadal Survey has Uranus out there. Uranus and Neptune are both kind of lonely since Voyager went by, and their outrageously wonderful moons are weird. Mostly Triton. Triton that we've discussed before is a super weird. Intriguing large object, probably captured Kuiper Belt object, with cantaloupe terrain. So I'm digging that. The atmospheres and the magnetic fields are weird. You can tell what I like to explore. Weird.

Venus, there's stuff going there in the coming years, so that's good. Asteroids have a lot going on. Go back to comets and then space telescopes. As I say, everything. But I think... Well, we'll see. I'm not good at predicting the future. I've learned that. And so, this is all good stuff and we'll see what works out.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I wish we could fund missions to every single one of them. Because if you asked me, send a mission to Enceladus versus send a mission to Triton, that would be a really hard call. But knowing the potential for life on Enceladus, I'd probably go that way just because we've got enough data to begin preparing for that mission, given what we know about it.

Bruce Betts: Well, there definitely have been Europa and Enceladus camps set up, and Europa was in the queue long ago and Enceladus joined it. So people will be pushing for Enceladus. Everything takes a while, especially when you're going to the outer solar system.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Seriously though, it's so far out there. Including Far-Out.

Bruce Betts: Far out.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That weirdo object.

Well, before we go onto our Random Space Fact, I wanted to share this poem that made me and a few members of the comms team a little teary-eyed. We had several people throughout-

Bruce Betts: I'm not going to cry.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'm not going to cry, man. Every so often, and you experienced this when you were doing the trivia contest with Mat and What's Up, but we have a lot of people who really love writing poems about our trivia contest. And we still hold the trivia contest in our member community each week. So a few weeks back, our question was actually a reference to a question I think you asked on the show almost 20 years ago, which is, Alan Bean left two silver astronaut lapel pins on the moon during the Apollo 12 mission. One was his own. Whose was the other? And the answer was Clifton Williams, who unfortunately died in a plane crash before they got to go to the moon.

So one of our members, Gene Lewin, who is a fantastic poet, wrote in this poem that definitely... I'm going to try not to cry this time, I promise. So here's Gene Lewin's poem.

Wish you could have been here, friend. It's lonely out in space. But I feel your spirit by my side in this barren lunar place. I stand here looking back at Earth, having traveled in your stead. The times we shared, the words we spoke, you had so much life ahead. The mission patch that bears four stars, a clipper ship below. One of the stars is you, my friend, the crew of Apollo. You left us doing what you loved. Not all can be so blessed. A silver pin you wore with pride. On Luna, it now rests.

Beautiful.

Bruce Betts: That's nice.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right?

Bruce Betts: It is beautiful. Well played, Gene.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Gene's poetry is great always, but this one...

Bruce Betts: No, it's very touching. That was one of the sad stories of exploration and one the nice compassionate things that Alan Bean did in putting those there. So yeah, good stuff. Well, I really don't want to compete with that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: The Random Space Fact is that was beautiful.

Bruce Betts: I'm not actually going to compete. This is where... Okay, everyone think wacky thoughts now. We're moving on to the Random Space Fact. So we're talking about Hera. I'm catching up with all these missions that are flying out there. So Hera is going back to Didymos and Dimorphos that were the subject of the DART mission. And so I was curious, what do they name features after on those bodies? Because they have themes for features, and the themes for features there are percussion instruments.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Seriously?

Bruce Betts: Seriously.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How... Who... I love this. Okay, continue.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, I mean, there aren't a whole lot of... There are no identified features as far as I can tell on Didymos because it was a rocky weird thing, but on Dimorphos they've got about 12, both craters and then saxum, which are big boulders, basically. And they've got percussion instruments from various cultures. Bala, Bongo, Marimba, Msondo, Naqqara, Tamboril. That's your craters. Just so you know.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's-

Bruce Betts: I assume you've played all of them. And your saxum, I'm sure you want to know, and I'll mispronounce all of them, Atabaque, Bodhran, Caccavella. Where is that from? Italian. I don't know how to do that. Dhol and Pūniu. Anyway, there you go. Percussion instruments. And also that means that as Hera it goes there, then when they take a much slower view of the system without just slamming into one of the objects, you'll get more percussion instruments.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, that's the exciting thing. I mean, at this point, all we know of the surface features of these worlds is literally just what we got in the moments before DART smash rallied into that thing. So man, that's going to be really fun. And then we'll have to come up with cool names for all of them. I'm sure there are enough percussion instruments on Earth to name plenty of features.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, no, I'm pretty sure that's why they would pick a category like that. They had no problem picking out those. They've got so many cultures with drums of one... Or not drums. There's percussion instruments of one kind or another. Not a problem.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: This actually connects to something that was kind of a big moment for me this last week. On the show, we've spoken about our team-up with the Radiolab team because they're trying to name a quasi-moon of Earth, and I officially get to be a member of their crew trying to help sort out all of the names that people have sent in. So we're going to be working together, me and Bill Nye and everybody else, to try to name that. So you've gotten to be a part of this before. This is going to be my first time actually helping to name an object in space.

Bruce Betts: Well, coolness. I mean, I've been in the narrow things down and it always has gotten to higher powers, usually tied to the mission and the space agency. And then all of these have to be approved by the IAU before they become official, International Astronomical Union, who's the referee, and make sure things are following the rules. But that's what you'll be doing. Making sure they follow the rules and judging them.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Judging them.

Bruce Betts: So, I look forward to it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: This is going to be hard. I'm going to need quite a spreadsheet.

Bruce Betts: We're going to need a bigger spreadsheet.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. I'll get your advice when I need it, Bruce. It's going to be awesome.

Bruce Betts: You're going to do great. All right, everybody go out there, look up the night sky and think (singing). Thank you and good night.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week to learn more about the origins of the heart on Pluto.

If you love the show, you can get Planetary Radio, T-shirts at planetary.org/shop, along with lots of other cool spacey merchandise.

Help others discover the passion, beauty, and joy of space, science, and exploration by leaving your review and a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day, but helps other curious minds find their place in space through Planetary Radio. You can also send us your space thoughts, movie recommendations, questions, and poetry at our email at [email protected]. Or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the Planetary Radio space in our member community app.

Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by our ocean moon loving members. You can join us as we work together to shape the future of space exploration at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. And until next week, ad astra and go Europa Clipper.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth