Planetary Radio • Oct 09, 2024

Clipper’s champions: Space advocates and the fight for a mission to Europa

On This Episode

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

Casey Dreier

Chief of Space Policy for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

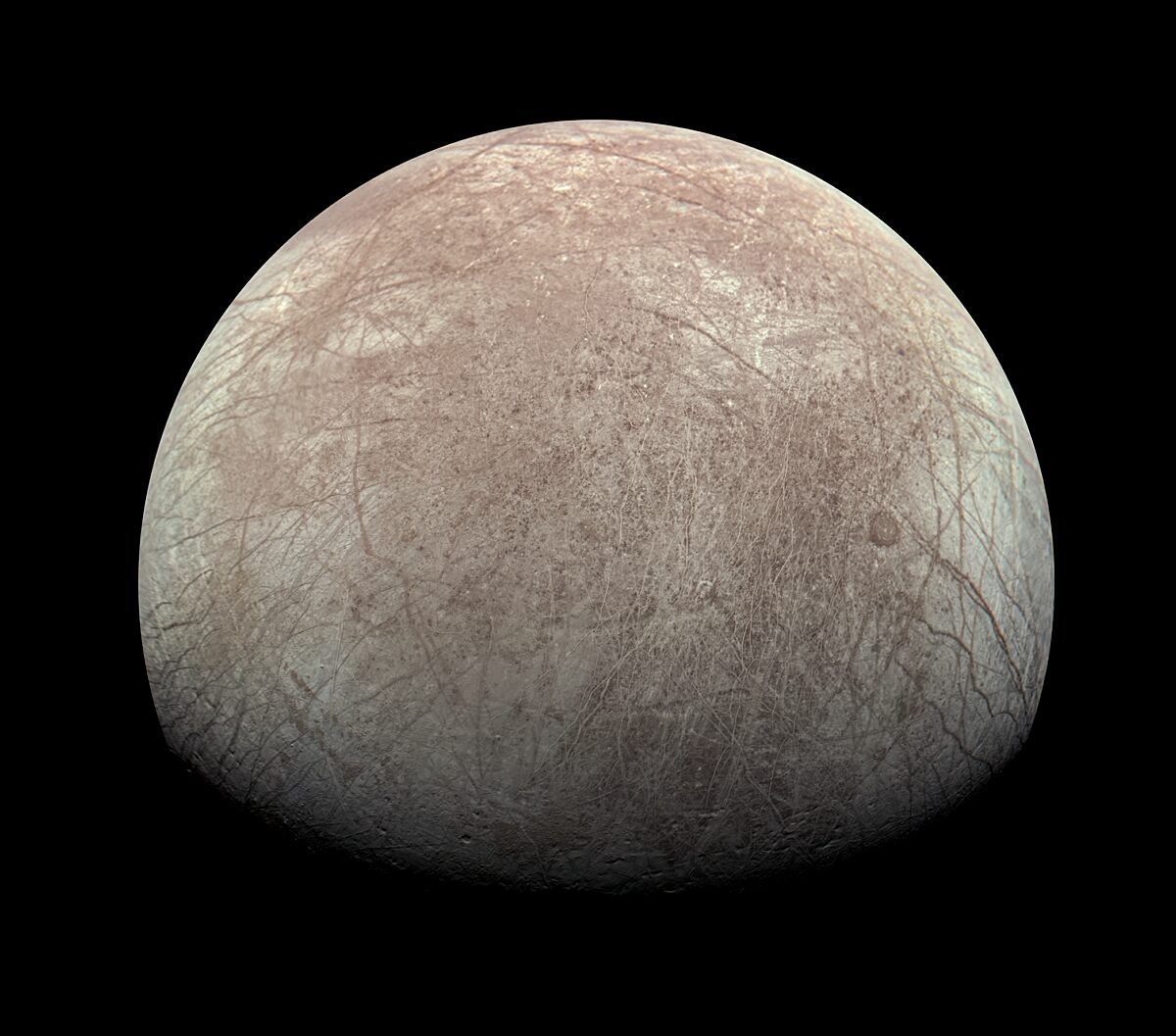

Jupiter's moon Europa is one of the most promising targets in the search for life. The Planetary Society and space advocates around the world fought to make Europa Clipper a reality. This week, we learn more about the tumultuous history of the mission with Casey Dreier, our chief of space policy. Mat Kaplan, senior communications adviser, gives an update on the successful launch of the European Space Agency's Hera mission and the delayed launch of Europa Clipper due to Hurricane Milton. Then, Bruce Betts, chief scientist at The Planetary Society, discusses two opportunities to view comets in the October sky in What's Up.

Related Links

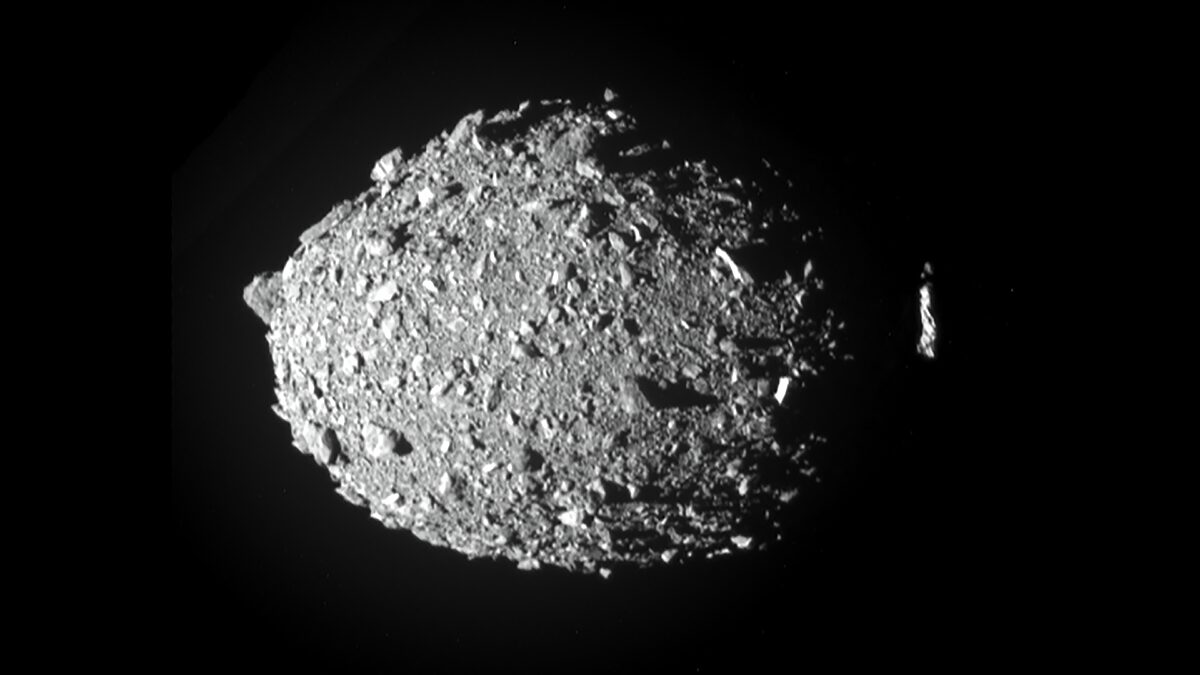

- Hera, ESA's asteroid investigator

- Hera launches to study the aftermath of an asteroid deflection test

- The Hera launch: What to expect

- Planetary Radio: Return to Dimorphos: Looking forward to the Hera launch

- DART, NASA's test to stop an asteroid from hitting Earth

- Europa Clipper, a mission to Jupiter's icy moon

- The Europa Clipper launch: What to expect

- Europa Clipper: A mission backed by advocates

- Could Europa Clipper find life?

- Planetary Radio: Europa Clipper's message in a bottle

- Europa, Jupiter's possible watery moon

- Enceladus, Saturn's moon with a hidden ocean

- Cassini, the mission that revealed Saturn

- What Is the Decadal Survey?

- Planetary Science Decadal Survey: After the Red Planet, an Ice Giant

- A billion dollars short: A progress report on the Planetary Decadal Survey

- Your Guide to the 2020 Astrophysics Decadal Survey

- How to spot Comet Tsuchinshan-Atlas

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

Europa Clipper would not have been possible without space advocates, this week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society. With more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond, Jupiter's moon Europa is one of the most promising targets in the search for life beyond earth, but the mission probably wouldn't have existed without the space fans who advocated for it.

Today we'll learn more about the tumultuous history of the mission with Casey Dreier, our Chief of Space Policy. But first, Mat Kaplan, our Senior Communications Advisor, will give us an update on the successful launch of the European Space Agency's Hera mission and the delay to the launch of Europa Clipper. Before we go, Bruce Betts, the Chief Scientist here at The Planetary Society will tell you more about two upcoming opportunities to view comets in the October sky and what's up. If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform by subscribing you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it.

On Monday, October 7th, 2024, the European Space Agency or ESA's Hera mission blasted off from Cape Canaveral, Florida, it's on its way back to the Didymos and Dimorphous asteroid system, the target of NASA's previous double asteroid redirection test or DART mission. You may remember that it purposefully smashed into Dimorphos in 2022. It was humanity's first test of the kinetic impactor technique, which we are going to use hopefully to redirect asteroids someday. You can learn more about the Hera mission in last week's episode. At the time that that episode came out, we weren't yet sure whether or not Hera was going to launch on time. That was due to the grounding of SpaceX's Falcon 9 Rockets. Thankfully, Hera launched as planned, but the incoming Hurricane Milton has caused an unfortunate delay to the Europa Clipper launch. With more details on what's going on in launches in Florida, we're joined by Mat Kaplan, our Senior Communications Advisor. Good morning, Mat.

Mat Kaplan: Good morning, Sarah. It's still a good morning and a good week for exploration of the solar system, even though we won't be seeing everything happened that we had hoped.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, it's definitely a good news/bad news kind of situation right now, and we don't know what it's going to be like later on this week, but as of right now, we know that Hera is on its way to the Jovian system, so we have that good news at least.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely, and that is so exciting. Just reading more about this mission largely on our website, planetary.org, some great articles by our colleague Kate Howells and then checking out other stuff that's going on with the mission, there's much more to this Hera mission following up the DART mission than I thought. It's really going to tell us a lot about both Dimorphos, the one that got slammed by DART, and Didymos itself, the sort of big sister asteroid.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: As we will learn later in this episode, it is sometimes really hard to get the funding that you need in order to do even amazing missions like Europa Clipper, and in the case of the Hera and DART missions, it's really cool seeing that one space agency could take on one part of it, a different space agency could take on another part, and splitting those responsibilities I think makes it a little easier to justify the cost of doing something like this and also really strengthens our international partnerships.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely. I mean, these are not cheap missions. Some of them are relatively inexpensive, but that value that you just pointed to there of seeing this kind of international collaboration is why Bill Nye likes to say space brings out the best in us and brings us together. It is so true for international missions like this.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'm really glad that this mission actually got to launch, but the FAA managed to clear this specific mission. This goes back to a lot of the previous conversations we've had over recent months regarding the two astronauts that are still up on the International Space Station, Sunita Williams and Butch Wilmore. Finally, we've got this SpaceX mission to go up there and rescue them, and then an issue with that rocket is the thing that almost caused Hera to not launch.

Mat Kaplan:

Yeah, and the FAA says they're going to proceed very carefully. I mean, they allowed Hera to launch because, boy, those people breathing a sigh of relief, they had planned from the start that this Falcon 9, if you want to get the most out of the Falcon 9, you're going to use that fuel that the first stage needs to make the soft return back down to Earth to the landing pad. They needed that extra velocity that Delta V to begin the trip out there to the asteroids, so they never planned to recover that first stage booster.

And because of that, since the accident that took place, the anomaly that took place was during the return of a booster, a previous Falcon 9 booster, the FAA said, "Well, you're not coming back anyway, so I guess you can go." Not true though, sadly, for the Europa Clipper mission launching on a Falcon Heavy, which of course is basically three Falcon 9 first stages and one upper stage for a Falcon 9, so there we are still on hold with that mission, which we were all hoping would be launching on Thursday as we speak, the day after this show is published.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, from a space fan perspective, it's a sad thing that we're not going to see this thing launch and all the members of our team that were looking forward to going are going to have to put all of those plans on hold, but there are larger things going on here. Hurricane Milton as we speak is on its way to Florida and it's supposed to make landfall relatively soon, I think tomorrow morning as this episode comes out.

Mat Kaplan:

Yeah, I feel so badly for so many people there in Florida, particularly on the West Coast around the Tampa area. This thing is just a monster with all that warm water in the Gulf. I mean, I guess it's back down as we speak to a category four, but it was a category five, 180 mile an hour winds went from category one to five in 18 hours, almost unheard of. As I looked at the storm path, the last time I looked, by the time it gets to the East Coast of Florida and the Space Coast, which it basically is projected to make a direct hit on, it's going to be a category one, maybe a category two, but people say, "Oh, category one or two," I guess those of us who don't live in Hurricane alley, that may not sound so bad, but that is still a storm that can do a tremendous amount of damage.

It's good to know that Europa Clipper is going to be hiding away inside that SpaceX facility. Cape Canaveral and Kennedy Space Center have had significant damage in the past from hurricanes, and it would not be surprising to see that happen again, and it would be an awful shame if that Falcon Heavy sustained any real damage, or for that matter, the launch complex because that's as important as the rocket if we're going to see this thing launch. Thank goodness they have about a month into basically the end of the first week of November to launch within the window that's going to get them out there to Jupiter.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: After all this time, all of this work advocating for Europa Clipper, I'm really glad that they're being careful about this decision-making here. I mean, whether or not you got to delay it because you have to investigate what happened with previous rockets or because of a hurricane, we want to make sure that the spacecraft is safe, but also everyone who's on the ground trying to launch these missions. I know a lot of the Hera team was hoping to stay in Florida longer so they could also watch Europa Clipper launch, and I hope they as well as everyone working on Europa Clipper managed to get out of there safely.

Mat Kaplan:

NASA did put the stress on the safety of the ground crews, the people who make these launches happen. We certainly can't fault them there. I bet though these people are so dedicated that if the decision had made to go ahead with the launch, they would've said, "Damn the hurricane we're going ahead," but NASA made the right decision in this case. And yeah, we're going to have other opportunities.

But I want to go back to what you said about this being a long time coming. You really can look back more than two decades to the first decadal survey, Planetary Science decadal survey by the National Academies that said a mission to Europa should be a really high priority, and it just wasn't happening for years. Even in the 2012, 10 years later, decadal study, they made the same recommendation, not much going on. And so our colleagues at The Planetary Society made the decision in 2013 that this was going to be a major priority for us, and I am so proud to be part of this organization that people within the mission, you know them, you've met them, look to us as having been a major player in making sure that this spacecraft has reached the launch pad.

I will be online and we're going to have a little launch party in the member community I know, which I look forward to being part of. It's just great to see this starting and go Europa Clipper and go Hera. We're looking forward to this close-up look at this moon of Jupiter and you can see the animations that show it flying through a plume just as Cassini did at Enceladus. Let's keep fingers crossed that it's going to be able to taste that stuff coming out of that moon. And I know they say, they always say it's not a life detection mission, but if we find some really huge organic molecules spewing out of that little body, it's certainly going to make us want to get out there again, perhaps with a lander to look even closer.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I mean, after what Cassini found with the evidence of hydrothermal vents and organic compounds coming out of Enceladus at Saturn, I would not be surprised if we saw something similar at Europa.

Mat Kaplan: Not at all.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But fingers crossed, we need to get this thing off the ground and launched first.

Mat Kaplan: Hey, and while we're at it, let's give some kudos again to ESA for the Juice mission, which is already well on its way and is also going to be exploring icy moons. Finally, more going on in the outer solar system. Now, if we could just get out there a little bit further to Uranus and Neptune, which are now high priorities in the current Planetary Science decadal survey.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, if history is any instructor on this, it'll be another 20 or 30 years before we see that happen.

Mat Kaplan: I can't wait that long.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But I'm heartened to know that it'll probably happen because of the advocacy of people all around the world who want to make this happen. We're just going to have to be patient unfortunately.

Mat Kaplan: It's going to be years before we see Europa Clipper reach its destination, and it's going to be two years, late 2026, before Hera enters the Didymos Dimorphos system and starts to do its work. And in the meantime, it's going to make a pass by Mars to pick up a little speed and redirect itself early next year. I'm looking forward to some nice snapshots of Mars as it passes by.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We have so much to look forward to so we can, I'm sure, distract ourselves in the years in between as we're waiting for Europa Clipper to get there, but oh man, I am so excited.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, I think there'll be enough to keep us busy, but I sure look forward to these arrivals.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I hope by the next time we have a conversation on the show, it will be a celebration for Europa Clipper and for Hera. We have so much to be grateful for in the space community right now, and I think we're all going to have a lot of fun, fingers crossed, celebrating later this month.

Mat Kaplan: Fingers crossed. I'm looking forward to a very, very happy celebratory conversation with you not too long from now.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks, Mat.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you again, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

Matt will host our upcoming space policy and advocacy biannual update on October 17th at 4:00 PM Eastern Time. He'll be joined by Jack Curie, our Director of Government Relations, and our next guest, Casey Dreier, our Chief of Space Policy. Planetary Society members can become a part of that event in our member community app, but we're also going to post it to our YouTube channel and our website a couple days afterward.

And while you're at it, keep an eye out for our most recent community event. It took place at Mount Wilson, one of the most historic observatories in the world. Mat was joined by Geo Samosa, who is our top volunteer, and Tim Russ, who you may know as Tuvok from Star Trek, Voyager and Placard. They did an excellent live stream from the 60-inch Telescope Dome, and I highly recommend it. You can find that on our YouTube channel as well as Planetary.org/Live.

That's also the place where you could find the link to the upcoming Europa Clipper launch. If you're a Planetary Society member and you want to join in the fun, Mat, Bruce Betts and I are all going to be in the rocket launch chat in our member community app on the day of Europa Clipper's launch. We all want to be together as we cheer on this mission on its well-deserved Voyage to Europa. This is such a huge moment not just for planetary scientists, but for the broader community of people that want to know more about life in the universe.

When we discuss the quest for life beyond earth, the common perception is that we're most likely to encounter beings on planets orbiting distant stars. We imagine the creatures from science fiction, strange beings that make contact across the vast space between us. As exciting as that sounds, it is possible that that profound discovery may occur closer to home on an ocean moon, like Jupiter's Europa. Beneath its frozen exterior, Europa has a liquid water ocean that has more water in it than all of Earth's oceans combined. In the dark depths below that ice, Europa contains all of the necessary conditions for life as we know it.

This knowledge has lit a fire under space fans worldwide for decades. It began with the Voyager flybys with the Jovian system in 1979. They revealed Europa's unexpectedly uncratered, icy surface. Then we returned in the 1990s with NASA's Galileo mission. It conducted multiple flybys of Europa and confirmed the existence of the global ocean beneath its crust. In this context, a dedicated Europa mission became one of the top priorities in the first Planetary Science decadal survey in 2002. Despite knowing that this was such a crucial target in the search for life, it took years of space fans shouting Europa from the mountaintops, and one of the most successful advocacy campaigns in the history of The Planetary Society to make it happen. Today we look back at the long road to Europa with Casey Dreier, our Chief of Space Policy. His newest article on The Planetary Society's website is called Europa Clipper: A Mission Backed by Advocates. Hey, Casey.

Casey Dreier: Hey, Sarah. Happy to be here.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Man, we're just a few days away from Europa Clipper launching.

Casey Dreier: I've got a 14-month old at home, so travel is not easy for me, but this is something that I've said for years I will not miss this launch. I want to see this thing go off into space and begin its journey. It will be a very important moment for me, but also for humanity too. We're going to such an amazing place. You know what? It will be the best thing that happens this fall, seeing this thing launch.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I think you're right, and of all the people that could be there. I mean, definitely the mission team and everyone that's worked on it, they deserve to be there. But of the people at The Planetary Society, you have done so much to try to mobilize people to advocate for this mission. All the way back in 2013, we started advocating for this, but you were there even before that. How long have you been working at The Planetary Society?

Casey Dreier: Would you believe that I've been here for over 12 years?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's amazing.

Casey Dreier: I think a quarter of the organization's existence. Summer of 2012 is when I first started working at The Planetary Society.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And it was only just a few months after that that you were in meetings discussing how we could try to support this mission.

Casey Dreier:

It was. It was an interesting time of transition. Bill Nye had taken over as CEO roughly a year before. We had a new CEOO and a lot of staff was kind of turning over, so a lot of new option space was opening up. I snuck my way into the society, I don't know how or who I had convinced, but they took the risk and hired me at the time, and I just always wanted to do advocacy because to me, that was why the society exists, it's the unique thing that we offer as an organization to our members. You want to help missions go to Mars, to the outer solar system to the planets to discover not for money, not for glory, but for curiosity, to inquire about why the worlds are the way they are. That is a really unique thing that we offer.

And so to start working at the society and then we didn't have anyone else working on advocacy at that time, and so I just started moving into that role. And yeah, January of 2013 we were talking with Bill and Jen, our COO, and other leaders at the organization at the time talking about, "Well, we're firing up our advocacy program this year. What do we really start to work on?" And Europa was the thing that we hit on and we talked to other people in the planetary science community, that's what needed the most help.

This was at a very rough time for planetary science. Planetary science was losing money, NASA was proposing cuts to planetary science, NASA was getting cut by Congress during the sequester, very contentious time in Congress with the Tea Party taking over under Barack Obama, so just lots of gridlock, and there was this fade to black of planetary science that was being seen that we were going down to this minimal survivable level. You had the NASA administrator at the time saying, "We're not going to do any new flagships for planetary science." And we at the time had not only wanted just to go to Europa, but we wanted to start the top priority of the decadal survey at the time was going to Mars to start Mars sample return.

So there was a lot to work on, but Europa was the one that was in a sense tied for the second priority mission for that decade to start. And it has this foundational motivation, we get it. Europa, it's an ocean world, it has liquid water. That's where living life could be right now. Why are we not there already? People get it. You don't have to spend too much time explaining the motivation for this mission. And yes, the society decided to really go all in on Europa in 2013, and we basically spent the next three years hitting that every opportunity that we could.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And it makes sense considering that at this point it had already been one of the top priorities of the previous decadal survey, the first decadal survey in 2002, and it didn't come to fruition back then. So what stood in its way for the first decade that it was kind of our top priority as a community?

Casey Dreier:

It's the same story, there just was not enough money to go around and there were other priorities at NASA. So in 2002, the very first planetary science decadal survey, yes, Europa was the top non-Mars flagship mission recommendation, but Mars was the priority for NASA at the time. They were spinning up the whole Follow the Water initiative at Mars, and so this is what brought us these great missions like Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Phoenix and MSL, the Curiosity Rover. Those were all big missions. And Curiosity was the big flagship mission of that decade.

At the same time, this was after the Columbia disaster, so this was the reformulation of NASA for human spaceflight starting at the time, George W Bush's returned to the moon program, Constellation. And then the United States invaded Iraq, funding for NASA that was promised never showed up because the war started costing so much money, the War on Terror at the time. And you had these big ambitious plans originally for a mission to Europa, like, "What if we don't just go to Europa? What if we create a fission powered spacecraft that will go to all the moons of Jupiter called JIMO," like the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer. I forget exactly what it was.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That would've been cool.

Casey Dreier: It turned out to be a $27 billion estimated project, which obviously then just never happened. So it kind of got caught up in various design stages that there just wasn't the money at the time to do it, given all the other, again, pressures. And again, the priority of NASA at the time ultimately was Constellation, even though that didn't work out, and then Mars for the science side.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thankfully we're now in a position where Europe Clipper is going to launch and the European Space Agency kind of took that idea with the Jupiter Icy§ Moons Explorer with the Juice mission, and so we'll get these two missions working in tandem to actually accomplish that dream of exploring all the Galilean moons. But I mean, my gosh, trying to get through the hurdles in Congress is one thing, but also just trying to go to Europa, the situation with all the radiation around Jupiter was a really huge hurdle, and we had to sort that out for other reasons with Cassini. So I can see how both this situation in Congress and the situation with just our lack of understanding on how to build a mission that did that kind of coalesced into a situation where it just didn't happen even though it was a top priority.

Casey Dreier:

Well, I mean, at the end of the day, it's hard to do more than one flagship planetary science mission at a time. Flagships are billions of dollars, and you don't want to just do one or two flagships in your project area, right? You want to do a number of them, you want to do small missions, mid-sized missions, you want to fund scientific research. At the time also, NASA was struggling to restart production of plutonium 238, the power source for some of these deep space missions or Mars surface missions that need to last for years at a time.

So you just had all these competing polls on the budget, and with Mars taking up a big chunk of it, there just wasn't enough left for mission to Europa. And you just can't do that cheaper, exactly for what you were saying, the radiation environment around particularly Europa is just brutal. And so you need to design something novel, completely new that can withstand that level of radiation. Also, if you wanted, originally this was a Europa orbiter, the amount of fuel you need to carry in order to slow yourself down enough to stop orbiting Jupiter and to start orbiting Europa also made it really expensive and complex.

And ultimately through these various stops and starts, you had these core mission designers and scientists, particularly at JPL, but also at APL and other places around NASA, trying to think about how can we lower the cost of this project and simplify and reduce some of these real big challenges? And this is where, as you said from Cassini, the Cassini team had gotten really good over the years about using flybys of all of the various moons of Saturn, but particularly Enceladus, right? That little moon that shoots out geysers of ice water to really map and have a lot of flybys, basically giving you almost the equivalent coverage of an orbiter. That allowed the spacecraft to dip in and out of this radiation environment, it allowed the fuel consumption or fuel needs to drop dramatically because you just orbit Jupiter instead of Europa.

And a lot started to fall into place, again, just from the experience and lessons of doing these other missions elsewhere in the Solar System, which at the end of the day, we talk about how important building a workforce is and building experience in these missions and fields, you don't have a mission like Europa Clipper if you didn't invest in a mission like Cassini and you gain that experience from these incredibly capable workforces throughout NASA and throughout the country that then allow you to tackle these other problems. I think that's a really important lesson from a managerial and national investment perspective of why you don't just cut your budget every time you finish a mission, you're investing in these people to carry you through and figure out how to solve all these problems going forward using the experience that they gain exploring the solar system.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I actually think I kind of internalized this for the first time in a conversation we had shortly after I started working Hera about SLS actually and about the value of propping up that program because it meant that we could support the broader community of people that had dedicated their lives to this. As soon as you cut funding for a huge program like that, whether it's at JPL or with our rocket systems, you brain drain everyone out of that field, they all flee to other places because it's not secure for them to be there. And that changes the entire arc of whether or not people decide to go into these fields in the future.

Casey Dreier:

We're going to have a future Space Policy episode about this concept. There was just this National Academies report that came out from Norm Augustine who used to be the head of Lockheed Martin, and it's a very chilling report. It's all about this issue of NASA's workforce being lost to attrition, being lost to competition, and not investing in the types of people and technologies that we need to enable efficient, cost-effective, well-managed projects to continue.

And that's exactly where you're going, you don't turn these workforces on and off like a light switch, it just does not work that way. And we need to be very strategic, if this is a national asset, which I would describe it as, we need to be very strategic and thoughtful about how we maintain, cultivate, and improve the national asset of our aerospace workforce to go and explore the solar system. That is literally a whole lot, we could talk about that for an hour and a half, which we will in a future episode. But yeah, to your point, it's critical and the essence of missions like this, we are successful and succeed and can happen because of that very point that you're making,

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Which is part of why I'm so glad to work at a place like The Planetary Society that can allow us to advocate for these kinds of missions and for the people that work on them. Because a lot of the people that work at NASA, because they work at these NASA facilities, are barred from advocating for themselves on these missions, which is why we play such a special role. But in this scenario, we saw Europa Clipper become a priority of the first decadal survey, didn't turn out. Then 2012 came around and Congress was in this kind of stalemate. I remember very vividly this time where no one could get anything done in Congress. Is that why we made the decision as an organization to really double down on this and make Europa Clipper our top priority of advocacy at the time?

Casey Dreier:

It was a mix of a number of things. What happened was in 2012, this multiple flyby proposal was released. And so you had the decadal survey come out for that decade and so it once again stated Europa is a really, really high up there, effectively tied maybe number two, depending exactly how you parse it, Mars Rover and Europa Orbiter the two top flagships to pursue. So that was part of it, so we had the scientific community backing. You had a new proposal to do a multiple flyby mission which would again, what we just talked about, reduce the cost and complexity, make it theoretically more achievable. You had these cuts coming down to planetary science, and so when you go to Congress to say, "I don't want these projects to be cut," you're not just saying, "Give money and then we'll figure out what to do with it," you say, "Give money in order to do this."

And so Europa was really that natural thing. And then it was just this, why are we an organization, The Planetary Society, if we don't love a mission to Europa? I mean, that I think is one of our core, if that doesn't get us going, then we should just close up shop right there. And so it was just a number of timings there is basically what it was, there's a viable pathway, and that's an easy way to think about it. That's actually kind of the difference right now as we're talking with the struggles of Mars sample return where we want Mars sample return to happen, but that's actually right as of the time we're recording that there's no real realistic pathway to achieving it at a lower cost point.

And so what do you get behind to advocate for besides just dumping money into the project? We need a realistic, achievable successful path that we can then support and make happen and that's what we had with Europa at that point in 2012 and 2013. And so it was just at that point, it was a no-brainer. It's like, "Look what we can do." And also, we knew there were various members of Congress who were open to this and were open to planetary science on both sides of the aisle, which was really important as well. And so that gave us, I think, the confidence to start talking about it.

But at the end of the day too, we as an organization, we want to find life beyond earth if it exists. And to do that, we should look at the most promising places beyond earth. So one aspect of looking for life is through SETI or looking through telescopes, but solar system, we can actually go to a place and interrogate it directly. I mean, you can go and look ourselves, we don't have to wait passively for a signal to come to us. And this is the huge opportunity, this is why we're doing this. And so you go to Mars and look for life there. And then we can go to an ocean world where there's liquid water in contact with rocks that has minerals, all the ingredients of life as we know it, plus billions of years to sit around and mix it all together. No-brainer.

And that was really at the time, I think, really an opportunity for a renewed effort to tie our advocacy efforts around, and maybe I'm jumping ahead, but it resonated with our members. And that's the important thing too, we live and die by our members, as you well know. And our members really came and supported this idea as well and resonated with it, donated to support it, advocated for it, reached out to their elected officials for it. It was really impressive and actually remains our most successful advocacy campaign that we've done in my time at the Society.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll be right back after the short break.

Bill Nye: Greetings, Bill Nye here. NASA's budget just had the largest downturn in 15 years, which means we need your help. The US Congress approves NASA's annual budget, and with your support, we promote missions to space by keeping every member of Congress and their staff informed about the benefits of a robust space program. We want Congress to know that space exploration ensures our nation's goals in workforce technology, international relations, and space science. Unfortunately, because of decreases in the NASA budget, layoffs have begun. Important missions are being delayed, some indefinitely. That's where you come in. Join our mission as a space advocate by making a gift today. Right now, when you donate, your gift will be matched up to $75,000 thanks to a generous Planetary Society member. With your support, we can make sure every representative and senator in DC understands why NASA is a critical part of US national policy. With the challenges NASA is facing, we need to make this investment today. So make your gift at planetary.org/takeaction. Thank you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, reading your article, I went in knowing that clearly our members are passionate about that just as we are, right? This is a huge opportunity for us to learn something about not just our solar system, but by extension life and the broader universe. But I had no idea just how deeply people cared about this and how much they went out of their way to advocate for this, because the number of people that wrote their representatives in Congress was so startling, I actually had to take a moment and look at that number and be like, "Is that right?"

Casey Dreier:

Yeah, we sent nearly 400,000 messages over four years to elected officials, and it kind of varied year to year, but yeah, it's around 100,000 messages a year. That's a lot. And again, that's why I said that the concept in a sense sells itself, people get it, particularly members of The Planetary Society, they get it. They're members, we don't have to convince them that a mission to Europa is exciting.

Plus you have all this built in. I mean, we haven't really touched on it, but you had this kind of built in fictionalized cultural base of Europa from Arthur C. Clarke with 2010 and subsequent books in that series that took the idea and ran with it, obviously in a fantastical way, but was based in some form of reality that there really could be something to this. And that helped all of this as well. And by the way, people are like, "Arthur C. Clarke?" He actually wrote to people at JPL and said, "I grant thee permission to land on Europa," like, we're good.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So many people many jokes about that.

Casey Dreier: I know the monolith aliens said, "All these worlds of yours except for Europa," but Arthur C. Clarke gave us an exception for that, so we're good to go.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I can't wait to see how many new bits of science fiction get rolled out after we go to explore Europa, because we've seen that every time I'm looking at a new science movie these days, I'm like, "I recognize that data from Cassini. I recognize those images from Juno." I cannot wait to recognize a picture of Europa from this mission.

Casey Dreier: I think wasn't there a bad horror movie set on Europa that came out in 2016?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Euro Reports?

Casey Dreier: Yeah, Europa Report.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I watched that, yeah.

Casey Dreier: Maybe I'm being unfair to the filmmakers.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, as we're approaching this launch, I'm trying to do all things Europa. I'm trying to get together my outfit for the launch day, I'm trying to watch bits of media so I can hype myself up because when it takes so many years for something like this to come to fruition, it can be really easy to feel like you're inundated, you're already in it. But then the moment happens, and I think it's really important for us to take these steps to really appreciate the journey that it took to get here, not just the scientific journey for everyone working at APL and JPL and all of the other facilities, but as an organization, we've been trying to get this thing, the funding it needs for over a decade. And here we are, we're going to have members of The Planetary Society gathering in Florida to celebrate. This is a moment for all of us, and I really want us to take the time to appreciate what we've done collectively as a planetary science community.

Casey Dreier:

That's exactly right. And I think the lesson from this, and this is what I've said for a long time, but this encapsulates it, is that if you're just a random member of the public, you'll see that this mission launched in some sub headline in whatever newspaper, so it just feels like these will just kind of happen, but they don't just happen. This took literally decades of thoughtful advocacy.

So I mean, the society did really step into it in 2012 and 2013, and then for the years afterwards to help get it over that final hump that we had to push it into finally NASA accepting this, NASA didn't want this mission for years, they rejected the mission year after year. There is language in the fiscal year 2014, president's budget request for NASA that is purely a negation of an idea, which is that we do not have the money for any missions to icy moons. I forget the exact names, but it literally went out this way, it's like, "Stop bugging us about this Europa stuff." Yeah, and exactly right, two years later, they asked for the money for the first time.

And so it took this push, but as I said before, it required so many people working to figure out how do you reduce the cost? How do you do an alternate mission architecture to reduce costs and complexity? You had to first go. I mean, the first hints we got that Europa was worth going to was in the 1979 Voyager flybys of Jupiter, particularly Voyager 2 that kind of had this, "Wow, what's this weird bright surface that isn't well cratered, and so it must be really young and fresh?" And then ultimately getting Galileo, which itself was a huge turning point, and briefly JPL faced the abyss and was almost closed down and almost lost its last planetary mission in 1982 with Galileo, that got to Jupiter and then revealed this incredible surface of Europa and detected that induced magnetic field, which is indicative of this liquid water ocean. So it's the late '90s and '99 basically had these first papers come out saying like, "There's probably a lot of water here, people," and then it took 15 years after that to secure NASA to start building it, right?

And then we had to design and build it. This is what's so wild, right? This is why advocacy, I'm always so impressed with Planetary Society members and their patience and vision for the long game because we're always asking you to advocate for something that in the best case will happen within a decade. And the advocating part happens usually, unless we're preventing something from being canceled, but if you're advocating for something to happen, you are working for years to get something over that hump just to kick off this whole design and build phase, which takes years to do. And then you launch and depending where you're going, it can take anywhere from a year to, in this case, six years to get where you're going.

So we had people, again, all of these messages to Congress, these nearly 400,000 messages to Congress were sent for something that will pay off for the people who wrote those messages 15 years later when that mission gets to Jupiter. And that's actually extraordinary. And particularly when you think about the cycles of politics and the cycles of interest and paying attention, that takes real vision to do, which is why it's hard, why a lot of people don't do this. And this is why you take the moment for the launch, this is in a sense your kid is going to college, they're walking out the door or whatever, you're pushing them out of the nest, this is the big moment where everything has been leading to this, and then everything really starts and you have this incredible thing to look forward to.

But at that same time, this is why I think it's important the society played this part, but I also just want to make sure, as you've already mentioned, and I'll emphasize that it's really the engineers and the scientists and the technicians are why we have this mission ultimately, right? And the people who came up with the alternative architectures and kept pushing it and established the scientific base, argued for it, and the decadal surveys. They ultimately are why this is happening. And the society was able to come in kind of of at this particular moment, and this is why, complementary, what we do best is like we will help make this case to Congress and make it not just so... Ultimately there's this patron saint of Europa, right? John Culberson who ultimately became the Chair of the Commerce Justice and Science subcommittee in the House of Representatives, the Republican from Texas who just loved the mission and was one of the key individuals in Congress.

But he lost his re-election in 2018, and the mission didn't end with him because I think we had helped build this broad base of support. He was the key individual, but it went beyond him. Adam Schiff was a really important person in this conversation. Lamar Smith was a really important person. Judy Chu was a really important member of Congress. All of these people helped establish this broad base of support so that you can't just build a project around one elected official because, as we know, every two years, all of the House is up for reelection and one-third of the Senate's up for reelection, and of course, presidents change.

So you need to build a broader political base. And that's what we were really trying to do, and so you can see some of these events. So we did so many events in Washington DC during that period, we would bring Bill out, we would have members of Congress, some of the ones that I just named, come together and do special briefings, have other staff, and really raise the profile of this to show that, because, again, at the time, I was really trying to convince NASA, look, we have Democrats and Republicans on Appropriations committees and the Authorizations Committee saying, "Request this mission, we will give you the money, we are here to support this mission." And NASA just refused to do it.

But this is the whole thing was just building this space. So when they did, of course the money came. We'd always argued, that was always my argument, they said, "We don't have the money to do this mission because it'll take money from other stuff." It's like, "The money will show up, look at the people on both sides of the aisle who are ready to support you." And it's like, "Eh, I don't know." But they were wrong. Ultimately, they were wrong. The money was added and NASA could still do all these other things, we still did all these other things in planetary science. We still went to Mars, we started missions. Psyche happened at this time, we had other missions to the moon happen at this time. All this other stuff happened.

And so it was just really trying to lay this groundwork, which again, I think we helped do that was this critical thing of pushing NASA officially, and NASA and the Office of Management Budget, which the White House's budgeting authority help them finally say, "Congress can give me money every year," that's great. But spacecrafts take 10 years to build, you can't make long-term contracts unless you have the government, the federal agency committing to it formally saying, "We will make multi-year commitments to you. We will dedicate ourselves to securing funding and fulfilling our commitments." And that does not happen without NASA deciding to do it. So we could get money through Congress every year, but it wasn't until NASA formally requested the project and it got a new start as that terminology that you could really start building the project.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It was interesting seeing that even when NASA took that step, they were still pretty reticent. They were still down in this space where they're requesting these kind of pithy amounts of money, and here comes the people from Congress, like, "No, let's just multiply that by 10."

Casey Dreier:

Yeah, and this is why at the time, it is funny going and revisiting this, a lot of my old pulling my hair out of frustration moments, when we came back, I kind of felt this, because again, you're right, it's like finally NASA requested to start what called Phase A of the project so initial formulation and design. And then you get to what's called KDPC, you move from formulation into implementation, NASA makes a formal cost commitment and you've designed it, you know how to build it, and we're going to build it. And then the project has become basically as secure as the project gets. So just getting into Phase A was a big step though because then you can start treating it like a mission. And that's what we were really pushing for, get into this Phase A design stage.

And so yes, the first year that NASA requested $15 million for what would be a multi-billion dollar, just nothing, literally NASA that year would spend more on travel costs for all of its employees than it would spend on designing it if they had their way. And Congress, I think I forget exactly what the number was that year, it was like 150 or 185 million they gave NASA instead. And again, John Culbertson was in that position to really bring the money. And so what did NASA do is like, "Wow, we asked for 15, we got 10 times that? Oh, 30?" It felt like we had their arm behind their backs and there was like reluctantly, "Fine, we'll ask for some money, whatever, just get off our backs." But they weren't fully committing to it. And again, it went on for years.

And it frankly wasn't until it was both the administration switched over, but also they finally hit confirmation point because they kept getting way more than they were asking for as long as John Culbertson was there. And so it was frustrating even after that so there was still some modicum of, "Come on, you can ask for this," but there was just this fundamental reluctance of like, "No, we don't want to do this." That thankfully ended up passing a long time ago.

But that, again, just shows you institutionally when you're advocating for a mission. You have to get so many different institutions aligned and you can build a ton of support in Congress, but if you have resistance in the bureaucracy, whether it's at NASA or the Office of Management of Budget or at the White House, it is just so much friction. And so if you can just ultimately align everything and the friction goes away, things can happen in a much more straightforward manner, which eventually they got there. But that's why, again, advocacy, we'd have to keep going back to our members year after year after year saying, "We still need your help." And this is why, again, I find Planetary Society members so amazing and inspiring is that they kept showing up and kept getting it, and were able to kind of say, "We understand this is a big complex process." And so yes, it was a big long thing. And it really, again, it wasn't I think until 2018 or 2019 that the request started to match actually what needed to launch in the early 2020s.

Then there was this whole drama, right? Originally was supposed to launch in the SLS, which particularly now in retrospect, would've been a disaster for the project. Very, very expensive and also there wouldn't have been an SLS probably ready to go but they needed to move that off. All of these other things had to happen. So it was a long journey. And again, this is just a complex big thing, this is not necessarily unusual, democracies are messy, but this is why we have organizations like The Planetary Society, and all these other people dedicated to pushing these stones uphill over the years. And then again, the actual people who have to design, build, and think about these missions to enable to make this work at all.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

Now listening to the saga, it's almost like hearing about the way that NASA as an organization has dealt with the trauma of having the rug pulled out from underneath them for years, right? I understand why they would be reticent to ask for something as wild as a Europa mission in the context of all of these other moments that they wanted as an organization to accomplish something and weren't given the resources.

Which is why I really, I hope deeply in my heart that at some point we can build this system where NASA always knows that at least they're not going to have that funding pulled out from underneath them in the middle of a mission. Because once we can get to that point, then they can really feel comfortable, they can feel safe in their international ties and with their workforce, but also maybe then they'll be ready to ask for those pie in the sky kinds of missions like a Uranus orbiter, or let's send some solar sails out to Proxima Centauri. There are some crazy things that we could be doing if we could get them into a place where they know that they're comfortable and safe to do so.

Casey Dreier:

You don't get anything you don't ask for, and that was always our bit. Just try asking for it. And then obviously, I mean the smart thing is you try to build the support in advance of you asking for it. Europa was somewhat unique, again, in the sense that you had so much congressional interest that predated NASA asking for it. It's rare to have, and this is always the challenge. Europa, again, is this inherently compelling concept. Uranus Orbiter does not have that same innate that you don't just hear it and say, "Oh boy," because you just don't have that potential for life factor built into it. And so every mission project has a different of conditions.

But this is why I think the more our space program feels not just comfortable but wants to do the bold thing, this is why we have a public program now to do the bold things. And this is always the pitch for the last few years is that we turn over the mundane, the regular, the well-known stuff to industry, to partners, to others to do, and then we let NASA do the crazy stuff, the wild stuff, the bold stuff, the experimental stuff, because no one else is going to do it. And if we can't build the political and institutional systems that enable that, then we start running into, you'll have a lot of political, it's like, "Why are we doing this then if we're not doing something that inspires people?" Because that's one of the fundamental returns of a space program is, what are we giving back to the public? It's like we can do great things if we want to.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But it also means that we have to make the case to the public, which is why we do so much public outreach and so much education. In the case of Europa, it's an easy sell. We've been to that system so many times, we have all the evidence in place. For something like a Uranus orbiter, we've only flown by Uranus once in the history of humanity. We have a few images from before I was born. So once you get the ball rolling on a world like Mars or Jupiter or even Saturn, then you can really get more public mobilization to make these dreams come true. And here we are all this time later finally seeing Europa Clipper go up, it just feels surreal and so triumphant for everyone involved.

Casey Dreier:

Absolutely. It's going to be a wonderful moment. And for anyone who's been listening to my show for the last year or so, there's been a, not stated, but I think the theme has been really understanding that motivations and how we talk about what we do and exploring this aspect of the hard to describe, the nonverbal experiential benefits of what we do that are hard to quantify and not necessarily discussed or even appropriate really for discussion in a public policy context, but nonetheless as important of a value and a return that we tend to dismiss or not talk about because it's inherently hard to verbalize, which is this kind of aspect of the sublime, this aspect of doing something that has deep meaning and will outlive you and is so much bigger than any one individual but represents something grand and beautiful. And being able to say that and talk about it and acknowledge it because it's part of being alive as a human, that we have these feelings.

So going to a rocket launch for me is a spiritual experience to see something, in particular a science mission launching because you sit there and you realize so much work and so much effort, and you see the thousands and thousands of people who have worked their lives and given their lives to put this piece of metal, complex piece of metal at the top of this really large bomb basically, a 40-story tall building that will go off into space and then you just see it leave the earth and it never comes back. And all for what? Because we wanted to know what that dot is, what's the deal with it?

And what a beautiful expression of the best angels of our nature to say that so many people have dedicated and given so much, and that we choose at some level in our society to enable this to happen, as we've talked about, because it doesn't just happen all for the idea of seeking out something unknown. And that's a beautiful thing. And I think that I always feel, it literally pulls us up and out where everything else in our culture these days tends to pull us down and in with our cell phones being kind of the visual metaphor of that, it cranes our neck and back out to look up into the sky and it's like, "We're going to learn something new." It will confront us, it'll challenge our ideas of what reality is. We'll have to integrate this new data that we learn from this into our preexisting concepts of how the world and the universe works and what is possible, and we don't know what that's going to be and what a wonderful thing to experience.

And so this aspect of the sublime, that is the ultimate reward in the sense of watching this happen and the visceral nature of watching a rocket launch with this on top of it I think is a perfect kind of experiential metaphor for what we're trying to do.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks Casey. Have a beautiful time at the launch. I cannot wait to hear your stories afterward.

Casey Dreier: I am very much, I don't know if anyone can tell, I am looking forward to it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Have a great time and I'll talk to you afterwards.

Casey Dreier: Thank you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'll leave you with these thoughts from The Planetary Society's CEO, Bill Nye, The Science Guy. This came from one of his addresses to Congress on the subject of Europa Clipper back in 2015.

Bill Nye: I just want you to understand what is at stake. If we could launch a mission to Europa, it would change the world. We have an opportunity, we are the first generation of humans who could send a mission to these extraordinary places and look for signs of life. Because they're robotic missions, the cost of these missions is relatively low. If we found evidence of life on these other worlds, you would be part of it. You would be part of this extraordinary human adventure. All the taxpayers and voters in the US and the people around the world who will contribute to this mission, it will be a human endeavor. It will bring out the best in humankind, and we will change the world. Thank you very much.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Now it's time for What's Up with Dr. Bruce Betts, our Chief Scientist. He'll let you know how to observe not one, but potentially two comets in the night sky. Hey Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hey, Sarah. How you doing?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I mean, I am currently doing fine, but as we're recording this the week before Hera and Europa Clipper potentially launch, I have no idea how I'm going to be doing next week. I still don't know what's going on with SpaceX, but I'm sure we'll find out in the next few days.

Bruce Betts: I mean, we'll see.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll see.

Bruce Betts: It is what it is. That's the rocket and space business.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Each one of these things has such a long legacy, which is why it was really cool to talk to about just how long it took for Europa Clipper to become a real thing and how much advocacy and love it took in order to make it a real mission. And part of reading his article and his analysis of it, something that I didn't really know was that early on the issue of radiation around Jupiter was so big for them in the early 2000s that they weren't really sure how they were going to deal with that with the spacecraft, and they had to wait for Cassini to do its thing and test those systems out. But I mean, I didn't personally fully understand how radiative Jupiter was until Juno got there and completely blew my mind.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, it's a nasty, nasty environment when you get inwards. And around Europa, and then Io's just a bear, they zip by Io and get the heck out of there whenever missions go there, and Io interacts with it and gets particles caught up. Anyway, yeah, it's a wild place because you got this huge magnetic field from Jupiter and you got charged particles that get into that magnetic field and it just whips them around with its 10-hour-ish day, and you're just slamming a bunch of particles and nasty, nasty, nasty particle radiation environment.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What do we do to our spacecraft to make sure that they can survive something like that?

Bruce Betts: You put a bunch of radiation shielding, put things that don't let as much radiation through. I mean, lead's the classic that you use to block radiation and they were hoping to do an orbiter, and then I think part of the decision to do flybys was you spend less time in the highly radiative environment. That's the key and the way they've solved that, you dip in, you get out, you dip in, you get out, and you may take some hits along the way in your electronics certainly, and you may lose some data, but hopefully you don't lose the spacecraft by doing it that way. Then they hope, a lot of hope, and then getting radiation-hardened electronics that are expected to last a long time or not if things don't go quite right, but that's what you want to get.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, there's the one issue of trying to make sure the spacecraft actually lasts long enough, but I just keep thinking about what happens if a really powerful cosmic ray just flies through one of your really important computer chips and suddenly you're messing things up.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. Well, they build in a lot of, especially in the big flagship missions, as much redundancy as they can afford, and then they build both in hardware and software and then you try to build in intelligent software and timers and things like that, which we even did with LightSail because it can still take radiation hits and it can upset the system. And so we had timers that would automatically reboot after a certain amount of time just in case something had gotten screwed up. That's a rather simplistic but effective way to do it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's really smart. I didn't know that we did that.

Bruce Betts: We did. We learned, LightSail 1 got stuck in a bad situation and happened to come out of it possibly due to a cosmic ray, but for whatever reason, but that's why we're very, very obsessive with timers. We had software and we had hardware timers, so if the software completely flaked out after some number of days that I don't recall thankfully anymore because I don't have to worry about it, the whole system reboots. But enough about LightSail 2, although I can talk about it a lot more if you wanted to.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: In the future, I'm planning some good solar sailing content because ACS3 deployed its boom successfully, we've got some really cool other solar sailing projects that people have been working on. So we'll get into it, I'm sure. Hopefully by the time this makes it into the show, Hera will have launched and then we got Europa Clipper to look forward to. But in the meantime, there is something that I brought up in last week's show in the bits between all of the interviews because we forgot to bring this up in What's Up, but there's an upcoming opportunity for people to see a comet. That's Comet A3 or Tsuchinshan-Atlas.

Bruce Betts: Maybe.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Maybe, potentially. And that's always the iffy thing with comets, right?

Bruce Betts:

It depends on how you define really cool. Yeah, comets are very unpredictable, so I don't know, this one's looking good. They're almost giving me hope, but it's definitely been people tend to overstate comets and then they break up or they're disappointed. But this one could be cool. It was kind of cool, certainly for telescopic and good photographic viewers as it was heading down towards the sun in the pre-dawn, and by the time this is airing, it'll be about to come up in the evening low to the western horizon and look soon after sunset, and it should ramp up. If it did survive the trip around the sun, it should have tails, probably two, one dust tail white and one ion tail that's blue or green or some such thing.

But in any case, 10th through the 12th is supposed to be kind of the sweet spot balancing all the factors because it's going away from the sun, but it's closer to earth. It's not right next to the sun, but it's close. So the 12th is my impression, is the ideal sweet spot. Probably hit a few days around that, but soon after sunset, look over there, look to the west after five days... Wait, no, that's look to the east and that's the writers of Rohan.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Gandalf?

Bruce Betts: Yeah, no, sorry. He looked to the west certainly after sunset and do it in the 10th of the 12th preferably, but look anytime around that. And I'm sure if it is super super duper bright, the news will be reporting it. Will it be the comet of the century? I don't know, we'll see. Maybe, maybe not. There's another one, there's another one coming later this month late in October that may be great or may not exist.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Really? I haven't heard of this one yet.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, I mean, it's pretty dim at the moment, so we'll see. There's promise for it, but who is it, David Levy who said they're like cats, they both have tails and they do whatever they want. Hey, but when we see the comet, remember the tail is actually in front of the comet because it always points away from the sun. So even though we think of it behind based upon earthly experience, but the tail will actually be leading at that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, that actually kind of weirded me out when I first learned it when I was younger.

Bruce Betts: It's weird.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's weird.

Bruce Betts: But I love it compared to our mundane terrestrial experience.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, we just passed the 10-year anniversary of Rosetta's Philae Lander touching down on that comet, so I think that was the moment I really kind of got into learning more about the mechanics of comets. I already knew this tail thing, but there's so much complexity to the way that stuff flies off of these bodies and just I loved that mission so much.

Bruce Betts: You've never met a mission you didn't love, but yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: There's got to be one out there somewhere.

Bruce Betts: Well, no. If they work, we're happy with them. And if we're not, we feel badly. Europa Clipper Juice is also headed out there, and of course Hera going to check out the crater that Dark made in an asteroid.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Come on, that many cool missions at once. We haven't had a moment like this since three missions went to Mars all at the same time.

Bruce Betts: Wow. You almost have me excited about this.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: You should be Bruce. Let the joy in.

Bruce Betts: Did you know there are missions coming? There are a bunch of them. They're planetary, they're awesome, I can hardly wait.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Okay, yeah, maybe take it down a notch.

Bruce Betts: Okay.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: All right. What is our random space fact this week?

Bruce Betts: Random space fact.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh no, I turned you into Eeyore, I'm sorry.

Bruce Betts: Guest appearance by Eeyore. I wish I were still talking about tails, that would've been so much more appropriate for Eeyore.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Perfect.

Bruce Betts: But instead I'm talking about Europa because we're thinking about Europa. Europa we think of as this icy world. It's very bright, it has a liquid water ocean, but it's the third-densest moon in the Solar System after the Earth's moon, number two, and Io, number one. They're also similarly ranked in terms of diameter. Europa, despite the outer shell is mostly rocky and Io is mostly rocky and they're not icy, and so they have a higher density, and that's just something that keep mind. It's part of what makes Europa so interesting is that it's got that rock core that's in contact with the ocean and could be providing energy for all sorts of swimming Sarah creatures that she imagines at any given time. There's a story. And the Earth's moon, except in Moonfall, is not hollow and so also rocky. Party on everyone, go check out a comet, go check out some launches. Sarah says so.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Sarah approved.

Bruce Betts: Everybody go out there looking at the night sky and think about, I know it's boring, but comets and launches. Thank you and goodnight.

Sarah Al-Ahmed:

We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with a look at the lives of students pursuing careers in space science. We'll give you some advice on how to survive grad school and support the students in your life. If you love the show, you can get Planetary Radio t-shirts at planetary.org/shop, along with lots of other cool spacey merchandise. Help others discover the passion, beauty and joy of space, science and exploration by leaving your view or a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day, but helps other curious minds find their place in space through Planetary Radio. You can also send us your space thoughts, questions and poetry at our email at [email protected]. Or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the Planetary Radio space in our member community app.

Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California and is made possible by our dedicated members who sent almost 400,000 letters to Congress. In support of Europa Clipper. I am in awe. You can join us and help many more amazing space missions launch to success at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. And until next week, ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth