Planetary Radio • Jan 31, 2024

The 20th landing anniversary of Spirit and Opportunity

On This Episode

Matt Golombek

Mars Exploration Rover project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Mars Exploration Program Landing Site Scientist

Kate Howells

Public Education Specialist for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

January marks 20 years since NASA’s twin Mars rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, touched down on the surface of the red planet. Matt Golombek, project scientist for the Mars Exploration Rover Project, joins Planetary Radio to celebrate. But first, the countdown to the next great American total solar eclipse continues. Kate Howells, The Planetary Society’s public education specialist, explains why this periodic alignment of our Earth, Moon, and Sun is more rare on the scale of the Universe than you might think. Stick around for What’s Up with Bruce Betts, our chief scientist, as we honor the Ingenuity Mars Helicopter and the Mars missions that made it possible.

Related Links

- Mars Exploration Rovers

- Cost of the Mars Exploration Rovers

- Red Rover Goes to Mars

- Planetary Radio: A fond farewell to Spirit and Opportunity

- Planetary Radio: 20 Years on Mars with Matt Golombek

- Planetary Radio: Landing On Mars With JPL's Matt Golombek

- Your guide to water on Mars

- The total solar eclipse on April 8, 2024

- Total solar eclipse 2024: Why it’s worth getting into the path of totality

- A checklist for what to expect during the 2024 total solar eclipse

- What is an annular solar eclipse?

- A guide to eclipse vocabulary

- Want to experience the 2024 total solar eclipse? Here are some tips.

- Buy a Planetary Radio T-Shirt

- The Planetary Society shop

- Register for Eclipse-o-rama

- Experience the total solar eclipse with Bill Nye

- Register for The Planetary Society Day of Action

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We're celebrating the 20th landiversary of Spirit and Opportunity on Mars this week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our Solar System and beyond. This month marks 20 years since NASA's twin Mars Rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, touched down on the surface of the Red Planet. Matt Golombek, who was the project scientist for the Mars Exploration Rover Project, joins us to celebrate. But first, the countdown to the next great American total solar eclipse continues. As of the release of this show, we are now 68 days away from an astronomical event that will blow the minds of millions as it passes over Mexico, the United States and Canada. In a moment, we'll be joined by one of my favorite humans, Kate Howells. She's our public education specialist and Canadian space policy advisor. She'll explain why this periodic alignment of the Earth, moon and sun is more rare on the scale of the universe than you might think. Stick around for what's up with Bruce Betts, our chief scientist, as we honor the Ingenuity Mars Helicopter and the Mars missions that made it possible. If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed about the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it. I alluded to this a moment ago, but it is with a heavy and happy heart that we say goodbye to the Ingenuity Mars Helicopter. After three years on Mars and 72 amazing flights, NASA announced last week that Ingenuity would soar no more. It traveled to Mars in the belly of the Perseverance rover, and when it took to the martian air on April 19th, 2021, it became the first craft to prove that powered controlled flight on another world was possible. The helicopter itself is still communicating with us. It's sitting upright on the martian surface, but it is now forever grounded because of damage to its rotor blades. But before you get too sad, remember that this tech demo was only expected to operate for 30 days. Like the Spirit and Opportunity Rovers that we're about to celebrate, this Mars helicopter lived way beyond our expectations and changed history. We'll hear more about it in future weeks, but for now, please join me in applauding the little helicopter that could. The Ingenuity team should really be so proud, and Ginny, you will be missed. And speaking of space moments that'll make you emotional, have you ever seen a total solar eclipse? Over the next few months, you're going to hear a whole lot more about this as space fans from around the world gear up for April 8th. If you've never experienced an event like this, it is absolutely worth traveling to go see. For some, it might feel excessive to go through all the effort to travel around the planet just to see the moon block out the sun, but after this next conversation, you might think twice about that sentiment. You don't get a chance like this in every star system. In fact, you might have to travel a long ways into the cosmic deep before you ever see anything like it. Here's Kate Howells, our public education specialist and Canadian space policy advisor to explain. Hey, Kate.

Kate Howells: Hi, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We're just a few months away from this total solar eclipse in Mexico, the United States and Canada, and I feel like it's coming up so fast.

Kate Howells: I agree. I remember when we just started planning all the stuff The Planetary Society was going to do around the eclipse, and it was a year out, and now all of a sudden it's right around the corner.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know, we've got so much to plan before Eclipse-O-Rama, but, oh, it's coming together; it's going to be so much fun. I don't know if you've had this similar struggle, but as a science communicator, when I'm trying to explain to people why they should go see a total solar eclipse, I usually fall back on what the experience itself is like, but I feel like there's something deeper going on for me that's hard to explain to people, which is that this opportunity is so rare on the scale of the universe, and I don't think people really understand that.

Kate Howells: I completely agree. I didn't even fully understand it until I started writing more about eclipses and learning in the process more about eclipses and really discovered how fluke-ish it is that we get the kind of eclipses we get here on Earth.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: There's just so much that has to be right for a total solar eclipse to happen, and it all depends on the angular size of the moon and the sun in our sky. What's so unique about our situation on Earth?

Kate Howells: Here on Earth, we have this marvelous coincidence that the moon and the sun appear the same size in the sky. The sun is 400 times larger in diameter than the moon, and it just so happens to also be 400 times farther away from the Earth than the moon is. That is a coincidence. That's not like some inevitable outcome of orbital mechanics or anything like that, that is just pure coincidence. And as a result, you get this thing where when an eclipse happens, the moon is perfectly centered over the sun and perfectly covers it, so you get to see the corona around the edge, but the actual disc of the sun is covered. And that does not happen anywhere else in the Solar System, and it doesn't even happen every single time the sun and the moon and the Earth align. I'm sure listeners have heard at this point about annular eclipses. If you haven't, they're very cool. It's where an eclipse happens when the moon is a little bit further away from Earth then at other times in its orbit. The moon goes around the Earth in an elliptical orbit, meaning it's not perfectly circular, so sometimes it's farther away and sometimes it's closer. And when an eclipse happens when it's farther away and the moon doesn't perfectly cover the sun anymore and you get this ring of fire, you're getting this really perfect demonstration of how fine-tuned these size similarities have to be for a perfect total solar eclipse to happen. Even on Earth, we're not getting that all the time. And Earth is the only place that we know of where this exact alignment happens.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And annular eclipses are still really spectacular, but it is not the same. We had one recently just in October, and it was cool, but it was not the same as my experience in 2017 looking up at that total solar eclipse.

Kate Howells: Also, annular eclipses, you don't even necessarily know it's happening unless you have eclipse glasses because that little bit of sunlight that peaks around the edges of the moon during an annular eclipse is enough to keep the sky bright, keep everything looking pretty normal. And so if you're just walking down the street and you don't know an eclipse is happening at that time and you don't have eclipse glasses to look up at it with, you don't even necessarily find out that an eclipse is happening in that moment. You can be completely unaware of it, and that's just crazy to think about.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I literally was walking down the street, and someone was like, "What's going on? It's a little dark." And I was like, "There's an eclipse going on." They had no idea.

Kate Howells: Yeah. It's wild.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What I think is also really cool about this situation is that even on Earth, this opportunity to see these total solar eclipses is actually limited in time. It wasn't always the case that we could have these total solar eclipses, and it won't be the case in the future because of the moon moving away from the Earth over time.

Kate Howells: Yeah, that is another amazing thing to think about is that, yes, the moon is slowly getting farther away from us. And so I don't know how many millions of years it'll take before this happens, but eventually the moon will be far enough away that you'll only get annular eclipses, you'll never get that perfect blotting out of the sun that we see during total eclipses.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: You mentioned the eccentricity of the moon's orbit around the Earth, how it's fairly circular, but imagine you lived on a world where it was even more elliptical. You might get that one total solar eclipse in an age, but it would be forever before you ever saw one again.

Kate Howells: It's true. It's so amazing to think about the different types of eclipses or the different frequency of eclipses or just what the eclipse experience, or I should say, what the syzygy experience would be on other worlds. Because syzygy, that's the term for when the sun and the Earth and the moon line up or basically when any objects in space line up like that. If you're on Mars, for example, you can have syzygy between Mars, it's moon, Phobos, and the sun. But Phobos is so small that that just produces a transit, not an eclipse. You just see Phobos moving in front of the sun. And of course you'd have to have a solar telescope to see that and not just get blinded by the sun, but still you have syzygy, but it doesn't produce the same effect. And then when you think about all the exoplanets and all the exo moons out there, there've got to be so many other variations of what we'd experience here. You might have planets where there are multiple moons that can pass in front of the sun at the same time. I'm sure there must be other worlds that have the same kind of coincidence that we have on Earth with the moon and the sun being the same apparent size, but it certainly must be rare. It really does give you that deep appreciation of how lucky we are here that we get such an amazing coincidence when we get to experience these kinds of eclipses.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I was thinking too about the fact that we only have one star in our stellar system, just the sun, but in most star systems, we see binary star systems, even multiple star systems together. Imagine that scenario where you get that perfect total solar eclipse on one of your stars, but you can't really appreciate the effects of it because the other sun hasn't set yet.

Kate Howells: It's too hard to even wrap my head around what that would be like. And that's part of what's so wonderful about knowing these things about other places in the cosmos. But you really have to use your imagination and really crunch your imagination to picture what it would actually be like to experience it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And worlds are so different. Even if you could be on a terrestrial world and see something like this, what if it didn't have an atmosphere?

Kate Howells: Yeah, true.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That would totally change the way that... You wouldn't get that surrounding rainbow sunset situation you get on Earth.

Kate Howells: Yeah, that's true. It would be a much more black and white situation, I guess. Yeah, yeah. Interesting.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, there's so many different ways that this scenario could play out. And I just remember thinking in 2017 as I was staring up at that ridiculous moment that this would be my thing. If I was a creature roaming through the universe looking for another world, the thing that would most blow my mind would be a total solar eclipse, a terrestrial world with total solar eclipses where there are creatures living to stare up and actually see it. That's got to make us one of the luckiest creatures or one of the luckiest species in literally the cosmos.

Kate Howells: Yeah, that's a really good way of looking at it. And I really appreciate how studying space and understanding what happens in all different worlds, it really does drive home how lucky we are, how unique our situation is. And it's great food for thought, fodder for appreciation of life and all that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, I like too that this is one of those things that really brings us together across nations. We'll be watching. A lot of us are going to be watching it at our Eclipse-O-Rama event in Texas, but you're going to be watching it up in Canada, right?

Kate Howells: Yeah, I'm already praying for clear skies because April in Canada, it gets cloudy, I think. This winter has been extraordinarily cloudy. I think we've gotten something like 30 hours of actual sunlight since the beginning of December, which is not good, so I'm really hoping it clears up in April so we can actually see it. But even if there's cloud cover, you'll still get that darkening effect. It'll still be cool, but I'm really hoping that we have the right weather to fully appreciate it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, we're going to be very lucky to see it. Hopefully the weather pans out, but even then, I know that we've made this case that everybody should try to go see one of these, but I understand that being able to go see a total solar eclipse is a privilege that everyone might not be able to go see so I'm really happy to share that we're going to be live streaming our eclipse event and our view of the solar eclipse from Texas. And it's going to be really cool because we're collaborating with Tim Dodd, the everyday astronaut, to bring that stream to everyone. We're hoping that even if you can't join us in person, even if it's not close enough to you that you can see it, you'll still be able to experience this eclipse with other people from around the world.

Kate Howells: Yeah, absolutely. And I think part of what's great about this eclipse is, yes, the path of totality stretches across three very large, populated countries, but the path of partiality where you can see a partial eclipse encompasses the entire continent of North America, so hundreds of millions of people are going to be able to see this to some degree. And I love the idea of being in a place where you can look up with eclipse glasses and see a bite being taken out of the sun with the partial eclipse and then tune into the live stream and see the total eclipse happen, see everybody's reactions to it, and feel like you're participating in this appreciation of this really very special cosmic event.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We're very lucky. Something that we don't always reflect on, but it's one of those ways that space really can make us understand just how lucky we all are to be here.

Kate Howells: Absolutely.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks for sharing, Kate. And I hope you just blew some people's minds and we got some more people to go see that eclipse.

Kate Howells: I hope so too. Thanks, Sarah.

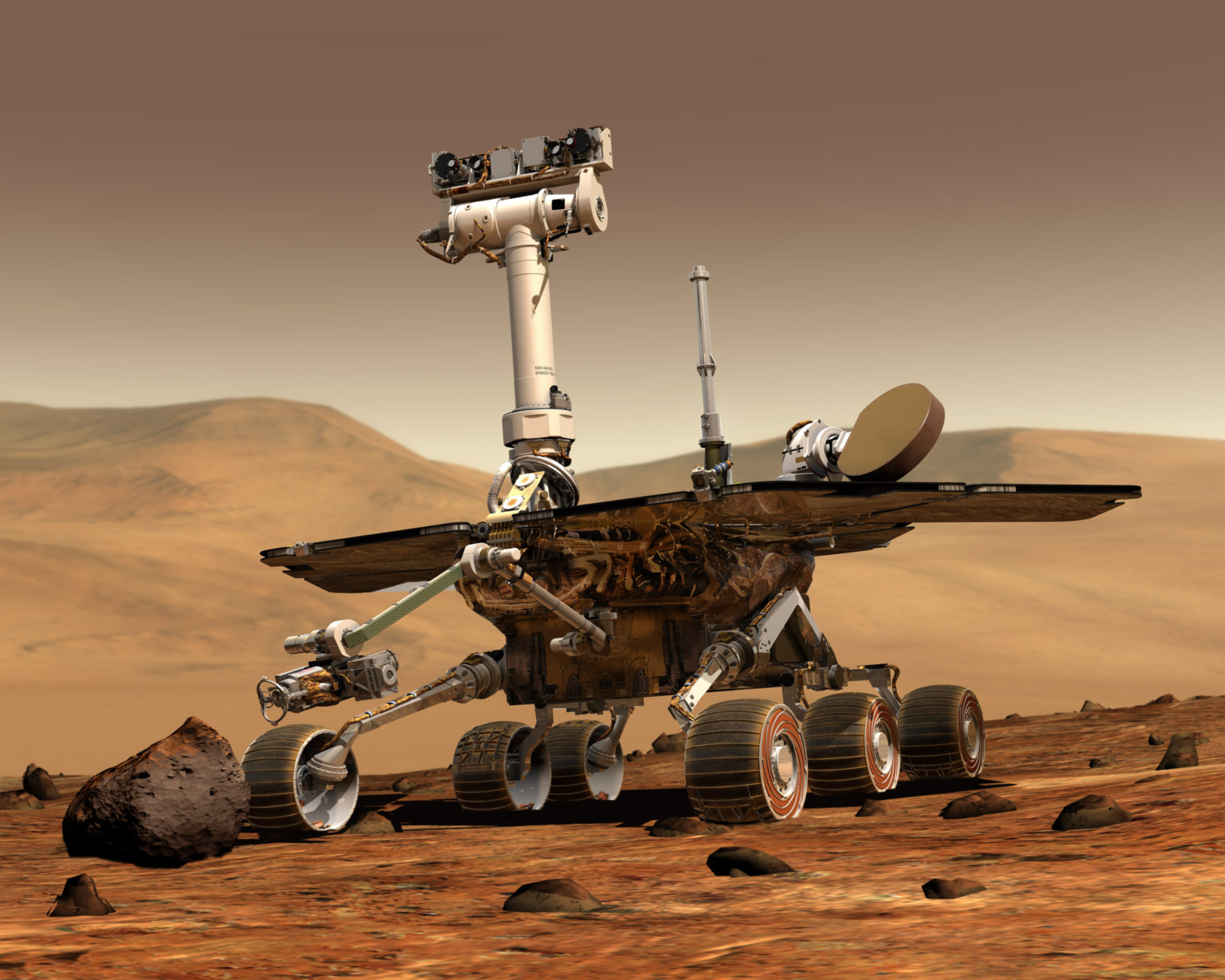

Sarah Al-Ahmed: From the awe-inspiring dance of celestial bodies in our skies, we transition to another marvel; one that lies millions of kilometers away on the rugged reddish terrain of Mars. It's been 20 years since the remarkable landing of the Spirit and Opportunity rovers on the martian surface. These twin Mars rovers far exceeded their expected lifetime and straight up redefined our understanding of the Red Planet. The Mars Exploration Rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, landed on January 3rd and 24th, 2024. These robotic field geologists captured the hearts and imaginations of the scientific community. And for the first time, they confirmed that there was once liquid water flowing on the surface of Mars. Both of the rovers outlasted their expected 90 day lifetimes by so much it's not even funny. Spirit's Adventure ended on March 2010, but the unstoppable Opportunity rover persevered, roving on until a global Martian dust storm covered its solar panels. Opportunity stopped responding in June 2018, and the mission was officially declared over on February 13th, 2019. And what a wild ride. We have a lot to celebrate, from the way that they landed on Mars, the clever ways that the teams kept them in operation and everything they discovered. Today's guest is Matt Golombek, project scientist for the Mars Exploration Rovers, what you'll hear him refer to as the MER program. Matt's involvement with Mars missions has gone on for decades. Before Spirit and Oppy, he was the Mars Pathfinder project scientist. He's played a role in multiple Mars missions, everything from global surveyor to Insight and even the Ingenuity Mars Helicopter. Hi, Matt.

Matt Golombek: Hi. Greetings.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's been many years since we last spoke, and I believe at the time you were in the middle of site selection for Perseverance. And I was really rooting for Jezero crater, so I got my wish. Thank you. But-

Matt Golombek: Everybody had a favorite.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know. It was a really challenging decision, but I think it panned out pretty well. But we're here today to celebrate the 20th anniversary of The landing of the Spirit and Opportunity Rovers on Mars. And those rovers had such a profound impact, not just on the history of Mars exploration, planetary exploration, but also on the people around the world that were following along with their adventures. And some people actually submitted questions to me that they wanted to ask you along the way, so I'll be posing some of those to you as we go.

Matt Golombek: All right.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: This has to be a really satisfying but also nostalgic moment for you and the Mars Exploration Rover team. How's it been?

Matt Golombek: There'll never be another mission like the MERs. 15, maybe 20 years of my life were wrapped up in the selection of the landing sites and then the subsequent operations. And just too much fun.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. You've been in it from the beginning with Pathfinder all the way on through to Perseverance, so I feel like of all the people on this planet, you probably have a really interesting perspective on what those rovers meant in the context of planetary exploration.

Matt Golombek: Yeah, I always think of myself as the oldest martian because I started working only on Mars in about '93. And there had been quite a hiatus from Viking to Pathfinder where there were people that were just doing that. And anyway, since Pathfinder, I've only worked on Mars. If it's not on Mars, I don't do it; just Mars.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: There's so much to explore there. And what Opportunity and Spirit and all of the subsequent Mars rovers have discovered, it just continues to open up these really intense questions and just begs for even more exploration.

Matt Golombek: Yeah, absolutely.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I think that Spirit and Opportunity have a very special place in my heart personally. Although the previous Mars missions were amazing and clearly had a deep impact on the way that the world engaged with Mars. I was a little too young to appreciate those earlier ones, but Spirit and Opportunity were like my first real rovers. We got to follow along with their adventures and see their trials and tribulations and beautiful discoveries. And I wanted to ask you, from your perspective, how did the world react differently to Spirit and Opportunity from the previous missions?

Matt Golombek: I have to go back to Pathfinder because I don't think there has ever been a mission to Mars that captured the imagination quite like that. At the time, that was the largest internet event in history. And the way news was back then, it was whether it was on the front page of the newspaper. And for a week, full week, Pathfinder was on the front page of every major newspaper in the country. And that has never happened before or since. I think I'd argue that without that reaction... And there's a whole bunch of reasons for that reaction, but without that reaction to Pathfinder, there wouldn't have been a MER. There may not have even been a Planetary Exploration program because that really brought Mars into the forefront of people's imaginations for the first time in 20 years since Viking. And the way it was done, it was a bunch of us in our garage, basically, as much as JPL's like somebody's garage. But it was done by a really small team for not a lot of money in a very short period of time. And so that, to me, that was the biggest revelation in terms of people's reaction. If you fast forward to MER, the part about MER that I was always most amazed at is that I would show up for a talk in eastern Washington state and somebody would ask me about, "What happened on the..." They had looked at the images because the images, when they came down, went right on the web. And they said, "Well, what are you guys thinking of that last image?" People were with us; they were watching the operations as they occurred. It was so seamless in terms of everything we'd done showed up almost immediately on the web. And people could follow along; and people did.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, I did.

Matt Golombek: And then there was this one period where it really came to the forefront when there was a change in the administration at NASA. And the associate administrator for space science had proposed turning off the rovers to save the operation money to be used for, at that time, sample return because that was what everyone was clamoring for. And the public reaction to that was so swift and so strong that the administrator for NASA fired the associate administrator and put somebody else and says, We can't do that. You can't turn off a rover that influences and that is watched by so many people." That brought forward how strongly people were... They were everybody's baby, right?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. And just goes to show that whether or not you work in the space industry, if you fall in love with a spacecraft and you make it known and you advocate for it, those things really matter because it literally saved these rovers.

Matt Golombek: Yeah, that's right. And it's probably a little bit different for those of us that worked on a day in and day out. I argue that we were all martians because when we were working on those rovers, our brains were on Mars. They were, where did the rover get to? What's the next step? What do we do? I need an astronaut for that. We had people on Mars. And we acted like we were on Mars, not just the scientists, but the engineers, the ops team; everyone was on Mars. Our collective brains were on Mars. We were martians. And I'm not sure that the same could be said for someone whose real job was something completely different.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's so true.

Matt Golombek: It's always worry about that a little bit because we were so close to it and so involved in it, it had to have been a degree of separation somehow to the public. Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. What portion of your life would you say you've been on Mars time?

Matt Golombek: I hated it. God, continue to hate it. It's just horrible. It's just you feel like yuck. We did it for about a month on Pathfinder. And at the end of that month, we were all dead. We were. In fact, I remember flying from JPL to Washington to meet with the president for Pathfinder, and I got on the plane and I literally passed out and did not wake up until we landed. Now, I don't usually sleep on planes was how exhausted we all were. Yeah. No, Mars time sucks. It's not sustainable. You can't do it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Maybe one of these days in the far flung future, people who grew up on Mars will be used to it, but in the meantime it's just-

Matt Golombek: Yeah, you'd have to live there with the daily... It's just long enough, 36, 40 minutes longer. In two, weeks your schedule's moved around the clock. You can't live like that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But I wanted to go back to those days during the landing of these rovers on Mars and even the days before that. One of our listeners wrote in, his name was Kevin Rush from Illinois, USA, wanted to know what the biggest challenges to getting the rovers to actually get to the launch phase was. And I think you've already touched on quite a bit of it there, but-

Matt Golombek: MER was really challenging from an engineering side. There were two spacecraft being built in about 36 months. It was even a little bit shorter than what Pathfinder was. I think we had a bunch of months. And we only had one spacecraft, so two of them at the same time. Now, it turned out the engineers actually argued that that was in some ways better than just having one spacecraft because you could test things on one and you wouldn't necessarily had to do exactly the same test on the other. AS it worked its way through ATLO, simply test launch, some argued, at least some of the engineers did that having two of them was better. But it was still a herculean task to do it. There's always problems when you're building spacecraft and you're testing things. And you wind up doing things differently than whatever you thought you were going to do when you started. And some of those were really important. The airbags became a number one topic because they started just shredding with the extra mass from MER based on what we had done with Pathfinder. I still remember going to the largest vacuum chamber in the world where we'd set up a test bed where we attached a full scale lander with a bungee cord and a 60 degree dipping platform with the worst, gnarliest rocks you ever saw and just kept pulling the thing down. And they kept ripping and the outer. And we kept sewing on additional abrasion resistant layers to where I think we had four of them in the end. It was just no other way to keep them from just deflating too soon. There were a lot of challenges with MERs that happened in a really sharp period of time.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's really intense to think about the fact that we didn't even have sky cranes back then. It was like we were practically bubble wrapping rovers and chucking them at Mars.

Matt Golombek: Yeah, that's one way to put it. I never thought about bubble wrap, but yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But that must've been really intense during the actual days surrounding the landing. What was that moment in time like for you and the team?

Matt Golombek: Yeah, I was actually in the CNN tent with Miles O'Brien, who was the science lead at CNN back then. I don't think they've had a science lead since he left. I guess that shows you about science and TV. For me, it was all about what the scene would look like after we landed. I'd spent three years during the development working on the landing site selection for the two rovers. And it was still fairly early in Mars science, I would say. To broaden it out even from the period from Pathfinder to now, there's been a constant presence at Mars. And just about every launch opportunity, we have sent something up to Mars. And I call it the renaissance of Mars exploration because we have orbital information and surface information unprecedented in a mountain scope that has led together to a much more sophisticated understanding about the planet. But now, let's take us back 20 years ago. And we had had Pathfinder, but that was only the third lander of Mars. And site selection for that was using no new information other than what we had from Viking. Maybe [inaudible 00:27:47].

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And that must've been so stressful.

Matt Golombek: That was stressful. But then-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, you landed in a boulder field.

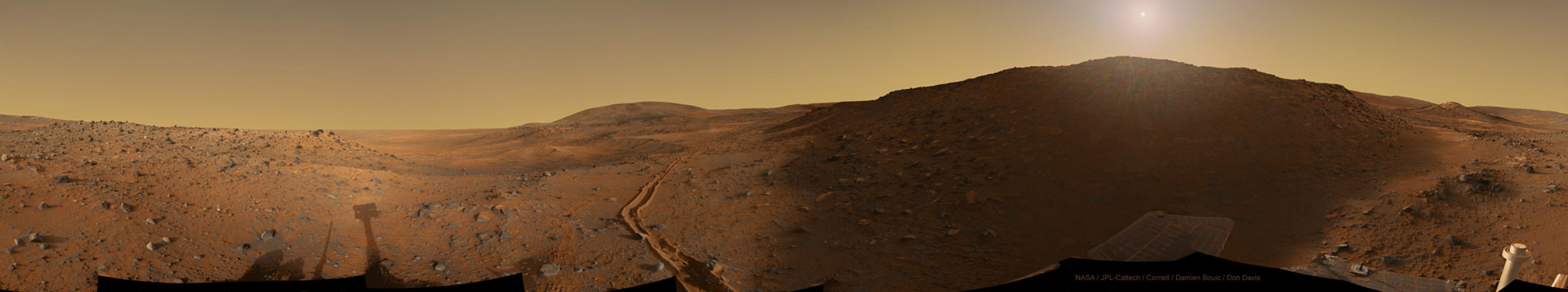

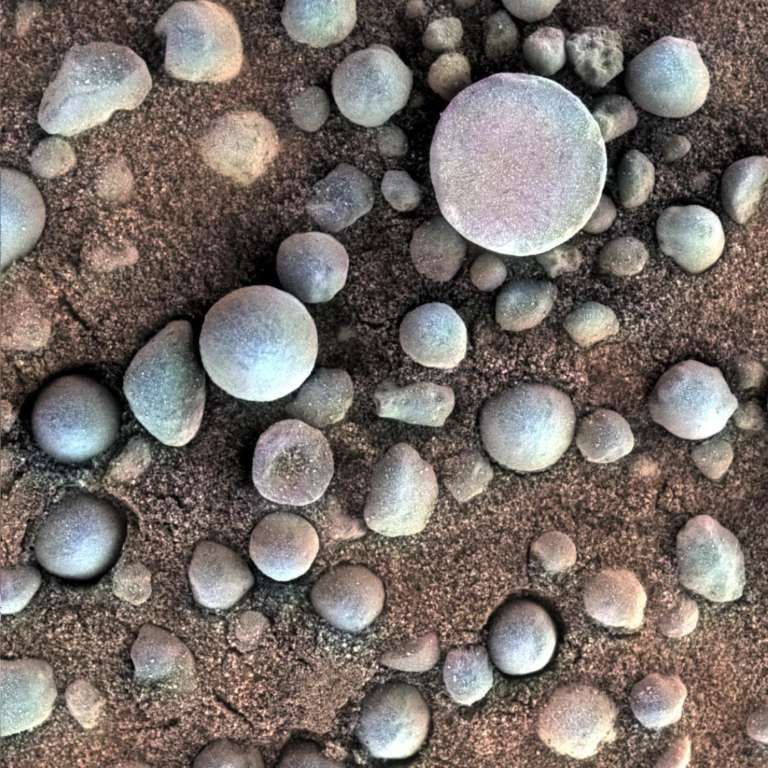

Matt Golombek: Well, we actually thought we were going to land in a boulder fear for Pathfinder because the airbags were incredibly capable of dealing with boulders for Pathfinder. The additional mass on MER made them not so capable of dealing with boulders, and so we had to go to much safer places with much lower rock abundance and the health of the landing of the spacecraft depending upon our interpretation of remote sensing data. We did not have images that were high enough for resolution to see the rocks. We had Pathfinder data, which was a third spot on Mars, and we had Mars global surveyor data and mock images, which were at about three meters per pixel, but you could not see rocks. The rocks weren't big enough and the signal to noise wasn't good enough, so we were inferring rock abundance from thermal inertia, thermal differencing, all sorts of other things, but we didn't know. And the interpretation of the sites depended upon how accurately those remote sensing data were pointing us to a smooth, flat and safe place. Nobody was more invested in the landings than me. Now, a lot of people were very invested for sure, but I felt like that was my life's work, that I had to find safe places to land and certify that they were safe. And they better be safe. And so what I wanted to see was the first images that came back from landing both Spirit and Opportunity. Spirit went to a place that we thought would be not all that different from Viking 1, 2 or Pathfinder, the relatively flat rock strewn place. And that's pretty much what we found. We landed a place, it did have low rock abundance, but it was just as red and just as dusty as other locations that we'd been on Mars. But we knew from the data that Meridiani, where Opportunity was going, would be completely different. The data indicated there was no dust. It would not be bright red; it was going to be a darker shade. It was going to have very few, if any rocks at all. And our data implied that there's a concentration of a mineral called hematite, which typically forms in the presence of liquid water. And that's what led us to land in Meridiani. The first images from Opportunity of this dark basalt sand surface was pretty much what we... Not red, no rocks. And then it was a scientific bonanza as well because it was in Eagle crater, and on the rim of the crater was outcrops of sedimentary rocks that we had not seen as well on Mars.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We actually have a picture of the rover and that giant crater up in our kitchen at Planetary Society headquarters because that was just such a moment. And what a beautiful place to go explore.

Matt Golombek: Yeah. And again, we could have never predicted it would look exactly like that. We knew it would be different. And boy, it was the most different place we'd ever seen on Mars.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll be right back with the rest of my interview with Matt Golombek, the project scientist for the Mars Exploration rovers, after this short break.

CaLisa: Hi, I'm CaLisa with The Planetary Society. We've joined with the US National Park Service to make sure everyone is ready for the 2024 North American total solar eclipse. Together, we've created the new Junior Ranger Eclipse Explorer activity book, and it helps kids learn the science history and fun of eclipses. If you live in the United States, call your nearest national park and ask if they have the Eclipse Explorer book. You can learn more at planetary.org/eclipse.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We actually had some people write in to say that that discovery of the hematite, or what most people I think remember as the blueberries on Mars, was one of the things that was definitely their favorite. And they wanted to know if we've discovered anything more about that since. But I feel like we learned what we needed to learn about that, which is that it definitely indicated the presence of water on Mars and its history.

Matt Golombek: Yeah. And not only that, but the whole way that geographic Meridiani [inaudible 00:32:32] formed was key. Those blueberries became a lag on the surface. And that's what helped produce the ripples and the ripple field and the smooth, sandy surface that we saw. And they're very interesting feedback between the winds that produced the sandy ripples that we drove over for most of the way and the fact that many of them were fossil ripples. They had formed hundreds of thousands of years before, and they were frozen in by those blueberries that effectively slowed down or almost stopped the aeolian motion that produced the ripples in the first place. But yeah, going from seeing those blueberries in the outcrop and then climbing out of the crater and seeing them strewn as this lag on the surface, this little one millimeter balls just across all... That was for us geologists that were worried about how the geomorphology developed, how did you produce that surface, that the light bulbs started going on.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And then Spirit found what appeared to be some evidence of ancient hot springs. I can so clearly imagine what might've been Mars' past. And the fact that that seems like such a beautiful place to potentially create microbial life is just so awesome.

Matt Golombek: To put it into even the broadest perspective of Mars science, at the time that the MERs went, we had remote sensing data images and some spectra that seemed to suggest that Mars might've been warmer and wetter in the past. But I think the scientific community was not convinced that it actually was; that there were alternative explanations for a lot of the things that we saw, things that hinted at a wetter past but didn't really prove it. And the MERs landed, and when we started looking at the sedimentary rocks at Meridiani, this was prior to Spirit getting to anything that indicated a really watery past, there was no question that we found sedimentary deposits that were evaporates. We knew the environment. We seen them on Earth. It involve liquid water in both the deposition and the subsequent alteration. But the thing that was truly interesting was the water was like battery acid. It was incredibly acidic. And generally, people don't look at battery acid as good things to start life in. Okay, Meridiani and our views there said there's no question that things were wet, but it was still a hostile environment with regard to life. And it wasn't until Spirit got over to the Columbia Hills and found the silica deposits that we found other environments that were much more conducive. And on Earth, hot spring environments teaming with life, and even more than that, the kind of life that live in those hot springs are chemists. They live off the interaction between the water and the rocks. No photosynthesis, none of that kind of stuff. And we think those are the most primitive organisms that exist on our Earth. The very bottom of the RNA tree are hydro thermophilic organisms like that. We found this place that on Earth would've been teaming with life. We had no way to know whether that happened at that site. But that produced a real change. Now we'd seen battery acid wet and water sloshing over the surface at Meridiani. We saw hot springs coming up to the surface at Spirit. And then to complete the whole pathway here, Opportunity getting to Endeavor crater and finding a different watery pass where there were clay minerals that form in neutral pH. And that's the kind of environment we usually think of as a nice place for life to get started. That's water you could drink if you wanted to. Maybe a little muddy, but still. And all of this happened before there was other information from orbit or on the surface that really argued unequivocally that Mars' early history was a lot more like the Earth and a lot less like the moon and only broadened and made more important the question of was it a habitable environment? Were all the things you needed to support life there? Were organics produced? Those are the things that came along later. Without those discoveries, you could argue that you wouldn't have had the subsequent MSL rover or maybe even sample return with Perseverance.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Honestly, though, it just told this story about the history of Mars that is just so beautiful and also so tragic, a world that was one so much like our own but is now just this desolate rock, but still a very beautiful desolate rock.

Matt Golombek: Even is that desolate rock the closest to the human habitation of any place else. If you ever think people are going to go someplace and actually live and be there, that's the other planet.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. Unless we want to build cloud cities on Venus. But that just sounds intense.

Matt Golombek: hat sounds tough. And on the moon, you definitely have to be in the hermetically sealed, no atmosphere. Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yep. Lunar lava caves or something. You'd never even get to see the Earth in the sky. It would be a whole other thing. But one of our listeners, Albert Heggy from Oregon, USA, wanted me to ask what's one thing that we had no idea we were going to learn from this mission before we arrived?

Matt Golombek: There were so many serendipitous discoveries that you could have never, ever predicted. Going in, when we landed, we thought this mission was going to last 90 sols. And we thought it would be out of battery power by sol 80 something. And we'd have a quadriplegic rover that had enough energy to maybe take some pictures, but it couldn't move around. And to go from that to one rover lasting, what, 15 years or... And the other one eight or something, I've forgotten, was amazing. You can trace it back to what we'd seen solar power on Pathfinder. We'd seen the dust falling on the panels and decreasing the power. But Pathfinder only lasted three months, so we didn't know what happened long term. To get dust devils that would clean the surfaces off the solar panels and make them as good as new, amazing that no one could have ever predicted that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, those martian dust storms are no joke. And it's very serendipitous that they'd come along every once in a while and brush Opportunity's solar panels clean. But I think the longevity of those missions, in most part, was because of the ingenuity of your team. We saw what happened with Spirit's broken wheel and everything you guys did to figure out how to actually continue on with that mission. That was amazing.

Matt Golombek: Yeah. And even more so an Opportunity, I forgot one of the switches, one that wasn't operating, we actually had to turn the spacecraft off completely at night because we couldn't survive, and then you had to wake it up from dead each morning. The first time we did that, we were hysterical that it wouldn't wake up. Well, we did that for years. Almost the entire time we had to operate the spacecraft like that. At one point we lost flash memory, so when we turned the spacecraft off, the spacecraft would forget everything that it did. And up to then, we had loaded up flash with a gigabyte of information that we had gathered, and we were going to send it back whenever we got the opportunity to send it back. Well, when we lost memory, it was zero, so anything you took one day was lost the second day. And you wound up making the same observations two or three times because if they didn't make it in the downlink for that sol, you had to do it again. It was 1,000 things like that. The arm wouldn't tuck back up underneath the spacecraft so we had to drive around with the arm hovering in front. One of the actuators for turning the wheel for steering on Opportunity wasn't working so we drove backwards most of the time. Well, the spacecraft was never designed to drive backwards. Yeah, 1,000 times we fixed things that broke on the spacecraft and managed to continue on. Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's funny because all of these things happened over the course of years, but it wasn't until I was sitting in a theater watching the documentary Good Night Oppy and seeing all of those things in the span of an hour that it really hit me just what an amazing challenge that was and how cool it was that you guys all figured out how to do that. And then an entire segment about the wake up songs really warmed my heart.

Matt Golombek: Yep. We did that pretty much every day.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Beautiful. Did you get a chance to pick some of those wake up songs?

Matt Golombek: I never did. I think the engineers kept that up to themselves.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'd put you on the spot and ask you what song you would use, but that might take a long time to think of. Spirit's Journey ended long before Opportunity's did, but we still had Oppy, so we were still very happy and invested. But then came the day that we lost contact with Opportunity. And I wish I could take you back in time with me to those days because at the time, I was working at Griffith Observatory, interfacing with people from around the world, and the beautiful and kind things that people said to me and my colleagues in those days about what these rovers meant to them is something that I wish I could have recorded and shared with you and the rest of the MER team because it was so heartwarming.

Matt Golombek: Yeah. And I don't get the impression that the subsequent rovers have quite captured the general mass' involvement in the same way. I'm not sure I know why. Part of it is probably that MER was... They were simpler rovers, and a lot more of what we did was explore. They were exploration rovers and finding new places. And that's what they were about. And the subsequent missions had complex laboratories that I don't know if most people really understand the details of that, and so they wound up sitting a lot more doing very important science, but not as much exploration. And then maybe even Perseverance, whose job it is to collect samples, there that's so important that it can't explore in the same fashion that we did with MERs. And maybe it was that exploration of finding something new, what's different, maybe that's what made the MER rover so much more accessible to everyone. I certainly remember with Pathfinder that every day people always say, "Well, what's the rover do today? And where's the picture?" Because we always took a picture of the rover after it had done its things from the lander. It was that same kind of excitement. Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I actually noted that the difference in the way that people viewed these different kinds of missions, when I was operating social media at The Planetary Society, you post up a picture from perseverance, people think that's cool, but then the difference between how people reacted to that versus Ingenuity, the Mars helicopter, was palpable. People were like, "We've never done this before. This is so amazing. Look at it do one hop." They lost their minds. It was really cool to see but very confusing.

Matt Golombek: Yeah. And it's funny because Ingenuity, I work on Ingenuity tremendous. And people were really interested in the first couple hops, but then I haven't seen people following along with it quite the same way. I don't know what was unique about MER, but maybe long lasting and really going and seeing completely different terrain that was unlike anything that it looked like when they started the mission. Columbia Hills really looked different than the plains, the Gusev Plains. And the rim of Endeavor crater looked so much different from what we had seen when... And even Victoria crater. Maybe that was part of it; it was like a whole new place to explore and see. Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But that's a great point too, which is that these rovers went an amazing distance on Mars. I think even to this day, they hold the record for how far we've traveled on another world.

Matt Golombek: Oh yeah, yeah. And even though their distance, I think... One day, I think Opportunity went almost 300 meters. That's not quite the record now, maybe perseverance, but having something that lasts that long and having that motive of exploring and going new to places was, yeah, it may never break that record for a while.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And now we're in this place where United States has an incredibly successful group of rovers and orbiters. But it's not just the United States. We have Russia, China, India, the United Arab Emirates; so many different nations are now at Mars. And just the pride I felt in my heart in 2021 when three different nations missions reached that planet all at once, I don't know if the public is as aware or as excited, but I feel like they should be because that was amazing.

Matt Golombek: Yeah, yeah. I still remember the day that the Zhurong Chinese were over landed. And the only "real time," in quote, you could get was a blogger in India that had people texting him from... It was so different from the way NASA does it, which is like, "Here it is. We're showing it to you in real time."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, I've got a couple pictures from Zhurong and a miniature of it near my desk. That's so funny. But up next, one of the biggest things that we're talking about in Mars exploration is this Mars sample return mission. And we're not sure whether or not the samples are actually going to be brought back yet. It's a very complex subject. But what do you think those samples might tell us about the things that we learned from Spirit and Opportunity? How could that expand our understanding of what we already learned?

Matt Golombek: I'll step back and try to do the broad Mars. Spirit and Opportunity found without question that water was present early on Mars. Curiosity has found that there all the ingredients you need to form life as we know it were present in a lake in Gale crater at the time, and that there are organics there. All of the things that you might need to form life existed on Mars at the same time that life first got started here on Earth. If there ever was a compelling scientific question to ask, Mars is the place to do it. But to know and to truly answer a question... What is it? Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof. If you're going to prove that life was there, you probably need the rocks back. You need to see in the rocks something that life produced to know that that actually happened or not. And I think at that level, I don't know if you could even do it remotely. It would be very difficult to get that level of proof that you need. And so I think the fact that Jezero had this broad assortment of rocks and that they've collected them all and already put a cash down with everything from basement rocks to rocks deposited in a delta where on Earth deltas are teaming with life, one of the most biologically rich places suggests that we have a pretty compelling suite of samples to return. The hard part is it's a really hard engineering job to get those samples back. And it's tough, just a tough thing to do.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It really is. But I think we've proven that we are up for these kinds of challenges. Yes, it's something we've never really done before, but look at all that we've accomplished on Mar so far.

Matt Golombek: Yeah. And I think we're closer than we've ever been, so I'm hopeful.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yep. And with our international partners, I think all of us working together, even if it gets delayed, even... Who knows what's going to happen, but one of these days we're going to get those samples even if we have to go to Mars ourselves to pick them up off the dirt. Before I let you go, I wanted to ask you a question that was also posed by one of our members. Carrie Hennigan basically said online that one of these days they would like to see a museum on Mars that's full of all of our robotic emissaries so that we can go celebrate Earth exploration. But I wanted to ask you how would you like to see them memorialized? If we could go to Mars and do something with those rovers, what would you like to see us do with those?

Matt Golombek: Wow. It's almost like you want to make each one a national park, right?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Exactly.

Matt Golombek: With little step paths you could watch and see what it did at which point and... I never thought about it. We've left an awful lot of stuff on Mars. There's a lot of rovers and all kinds of things. And not only that, there's air shells and heat shields and parachutes. And there's quite a bit of stuff left around. I hadn't ever thought about that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I would still go to the museum for the Perseverance back shell just to go see that. Well, I know it's not necessarily my place as a random human to say this to you, but I feel like I need to be the voice of so many people out there who wish they could thank you personally for the role that you've played in Mars exploration. None of this would be possible without the people that have dedicated their lives to it, and your life has been wrapped around this for decades.

Matt Golombek: Yeah, I'm a martian; no question about it. And I've had an awful good time with it too.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks for coming on and for sharing all of this and for literally everything and everything it's done for Planetary Exploration. You've made this case that these subsequent missions wouldn't have happened without these bits of Martian history. And I think it's absolutely true.

Matt Golombek: Thank you very much. And it has been a total blast.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Thanks, Matt. Those rovers are always going to have a really special place in the hearts of Planetary society members. Those who have been around with us for a while might remember our involvement with the Red Rover Goes to Mars Project. We teamed up with the Lego company to provide hands-on opportunities for students around the world who wanted to participate in Mars missions. And in 2004, a team of Red Rover Goes to Mars student astronauts worked inside operations at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. They got the chance to actually work on the Mars Exploration Rover program. If you get a chance to watch Amazon's documentary called Good Night Oppy, which I highly recommend if you want to ugly cry about Spirit and Opportunity, you can see some of the Red Rover Goes to Mars students in the background. We also gathered submissions from around the world and to this day, the names of every Planetary Society member prior to the MER launch and the names of over 4 million other people of Earth still sit on the martian surface. The disc with all of the names on it is actually bolted to one of the pedals on the MER lander. We'll hear from one of the students whose lives was totally changed by the Red River Goes to Mars program in the coming weeks. Now let's talk with Bruce Betts, the chief scientist of The Planetary Society, for what's up. Hey, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hey Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Man, this is just me in the moment, but I just found out a few hours ago that the Ingenuity mission on Mars, that cute little Mars helicopter has now ended its operation and is now just unable to fly on Mars. What a moment. I didn't expect that Mars helicopter to go so long.

Bruce Betts: No one did. Well, maybe the people who built it, I don't know. But it was far, far, far beyond the original expectation, which was only a few flights. And in fact, then they approved it to do more and they had many tens of flights; I lost track. But no, it did great. Apparently it's a bit damaged, but the fact that it did it that long and it did it in the Mars atmosphere, which is ridiculously thin, it's equivalent, depending on whether you're talking about with gravity or not, of 100... Sorry for the units, 100,000 to 130,000 feet up in the Earth's atmosphere. And imagine flying a helicopter. It's amazing.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Plus, they had to contend with martian winter. They weren't even planning to deal with the air that thin. They had to learn how to spin the rotors even faster to make it fly in those conditions. That team really knocked it out of the park.

Bruce Betts: They did indeed. Very impressive.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's funny too because I feel like there's just this constant kind of pattern because I've been thinking about Spirit and Opportunity about these missions really exceeding their expectations time-wise given Spirit and Opportunity were only supposed to be operating for 90 sols, and Oppy went on for 15 years.

Bruce Betts: They lasted. And in some cases when something would break, they'd figure out how to work past it. But generally, things just didn't break and last a long time. The trick seems to be getting and successfully flying in space or then successfully on the ground. And then oftentimes, at least these types of things work longer than expected, which is wonderful because we get so much more science return than was originally hoped for.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Here's hoping the same thing happens for Curiosity and Perseverance in 20 years from now we're still talking about them.

Bruce Betts: Well, they're already beyond their primary mission. Certainly Curiosity is way beyond its primary mission. Mars Odyssey, it was named Odyssey because it got there in 2001; still working. And of course, Voyager's still eeking things out way out there. It's amazing how long some of these things last, especially considering how nasty the environments are, whether it be surface of Mars or space. It's almost like people think about how to keep them working,

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But they had to do some really wild workarounds: Driving rovers backwards, turning it off and on again repeatedly. It's in part due to the really creative thinking of the people on the teams, but also-

Bruce Betts: Definitely. But I think the whole thing with the jump ramp and the going up on three wheels, I don't think that was necessary, they just acted like it was.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What I can't believe is that they actually managed to land Spirit and Opportunity with that amalgamation of these airbags. I made a joke when I was talking to Matt Golombek that we basically wrapped them in bubble wrap. And I still feel like that. That's remarkable it works.

Bruce Betts: They did. They wrapped them in very bulletproof bubble wrap. And in fact, when they originally used that with Pathfinder, and then they adapted it to these, but then one of the many times they realized, oh... Not that they were surprised by having more mass, but that that actually caused some issues, and so they had to work through them on the ground to figure it out. No, I've successfully failed to predict success on all of the last US Mars landings because every time I go, "Airbags. All airbags weren't weird enough. Sky crane? Yeah, no way." And every time, they nail it. And it's awesome. But yeah, airbags; and it bounced around. Opportunity was particularly entertaining because it bounced along for kilometer or two and ended up going into a small crater, so it was a hole in one.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Did we have any planet fests around the time that Spirit and Opportunity landed?

Bruce Betts: Yes, yes. We had one for Spirit, the Spirit landing. It was called Wild about Mars because also on that same 48 hour period anyway, the Stardust flew through the coma of Comet Wild, spelled for English type people Wild 2, and collected samples. And then we had a huge number of other things partnering as part of our Red Rover Mars program. But we had people from the mission come down to the Pasadena Convention Center and speak, and it was all very exciting.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I was today years old when I learned that I was pronouncing Comet Wild 2 incorrectly. Comet Wild. Were there any things that Spirit and Opportunity discovered that really surprised you?

Bruce Betts: No, not a specific thing, but certainly the confirmation of what people have been thinking about, the flow of water, the amount of detail they were able to extract from information, the stunning views and vistas that we got as they traveled along and went by larger and larger craters, the finding possible hydrothermal deposits right about where Spirit kicked off. And of course the hematite was confirmation of things. They learned all sorts of stuff and did what they were supposed to. And I was always intrigued. Because I think we talked earlier about that you had two landers, and they were chosen one primarily for the shape of where they were, the geomorphology at the end of a [inaudible 01:00:10] in a crater. And then the spectroscopy telling us that, of course, grained hematite, which hangs out in liquid water, usually on Earth was there. It was a good time. I don't know, did you think they were successful? You're usually pretty critical of these things.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: No, they totally failed. No, honestly, of the Mars missions, it's hard to say what's the most successful. But the things that they confirmed for us, how long they went on, it's really hard to not think that Spirit and Opportunity weren't some of the most successful space missions of all time, in my opinion.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, you say that about every mission.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, they're all my favorite. All right, what is our random space fact?

Bruce Betts: I just don't have the energy. No, I do.

Speaker 6: Random space fact.

Bruce Betts: This is a thought experiment because physics get a little broken down, but it's a concept of how big is the sun? And trying to even barely wrap your brain around that. We start at the Earth. And something like ISS or Light Sail or any number of other spacecraft and low Earth orbit orbit in about an hour and a half. And that's how fast they're going to go around the Earth. If you went that fast by the sun, well, you'd get sucked into the sun by the gravity, which is why it's a little bogus. But picture going orbital speed takes you around the Earth in an hour and a half, you're trying to go around the sun, nearby the sun; takes you a week. It's about a week to go all the way around the sun, whereas it's an hour and a half to go around the Earth at those speeds. It turns out, I don't want to shock you, the sun is really, really big.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: The sun is really, really big. And it's funny, just this morning someone I knew asked me whether or not the sun was a big star or an average star. And when I started explaining the sun is not that big of a star, they full shock Pikachu faced me. They were just like, "Really?" I started describing how big other stars are compared to the sun, and they were so surprised. That puts it in context. Man, we are so small.

Bruce Betts: Were you talking to Pikachu?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I was not. I was at the gym.

Bruce Betts: But they made a shock Pikachu face.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yep.

Bruce Betts: Oh. All right, well, anyway, back to the sun. Don't make it mad, please. Don't call it average. It's actually a little bigger than average, it turns out, now that we find more red dwarves. But it's not average, it's our friend, it's our sun, and it could toast you if you make it mad.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It could toast you just stepping outside your door.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, it's just a sunburn.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Still, think about the fact that it can burn you from that many miles away. That is just the power of stars, man.

Bruce Betts: Yes, yes indeed.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: All right, let's take this out.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody go up there and look out in the night sky and think about whether you can speak more coherently than I can. Oh wait, the answer is yes. Thank you, and goodnight.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week to talk about the field of archeo astronomy. We'll talk a bit about the ways that cultures have interpreted total solar eclipses throughout history. Love the show? You can get Planetary Radio T-shirts at planetary.org/shop, along with all kinds of other cool spacey merchandise. Help others discover the passion, beauty, and joy of space science and exploration by leaving a review or a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Your feedback not only brightens our day but helps other curious minds find their place in space through Planetary Radio. You can also send us your space thoughts, questions, and poetry at our email at Planetary Radio at planetary.org. Or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the Planetary Radio Space in our member community app. Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California and is made possible by our members who always stop to stare at Mars when it's shining overhead. You can join us and help shape the next generation of Mars missions at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which was arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. And until next week, ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth