Planetary Radio • Oct 11, 2023

Celebrating the OSIRIS-REx sample return

On This Episode

Rae Paoletta

Director of Content & Engagement for The Planetary Society

Michael Puzio

Winner of the contest to name asteroid Bennu

Larry Puzio

Father of Michael Puzio

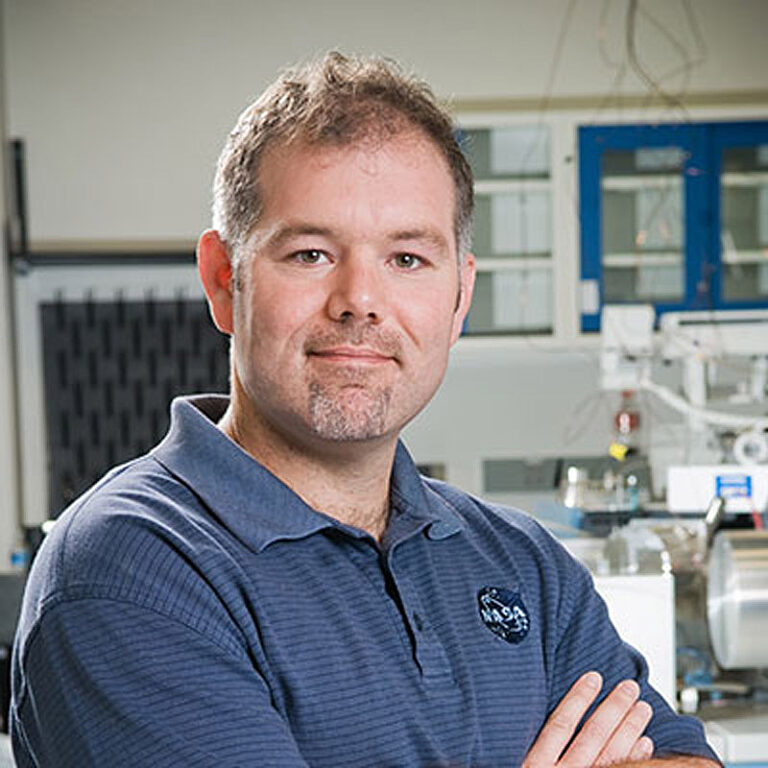

Daniel Glavin

Astrobiologist and sample integrity scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, co-investigator for OSIRIS-REx

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

On September 24th, NASA's OSIRIS-REx spacecraft triumphantly delivered a sample from asteroid Bennu to Earth. Rae Paoletta, the Director of Content and Engagement at The Planetary Society, joins Planetary Radio to recount her firsthand experience of the sample's return in Utah. She introduces us to Mike Puzio, the young man who named asteroid Bennu, and his father, Larry Puzio. Then Danny Glavin, the co-investigator for OSIRIS-REx, shares the next steps for the asteroid samples and the spacecraft. Stick around for What's Up with Bruce Betts, the chief scientist of The Planetary Society, as we digest this huge moment in space history.

Related Links

- OSIRIS-REx returns sample from asteroid Bennu to Earth

- The boy who named Bennu is now an aspiring astronaut

- OSIRIS-REx, NASA's sample return mission to asteroid Bennu

- Planetary Radio: A Deep Dive into Asteroid Bennu With Dante Lauretta

- Find your OSIRIS-REx Messages from Earth Certificate

- Cost of OSIRIS-REx

- Make your gift to LightSail’s Legacy

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Say Hello

We love to hear from our listeners. You can contact the Planetary Radio crew anytime via email at [email protected].

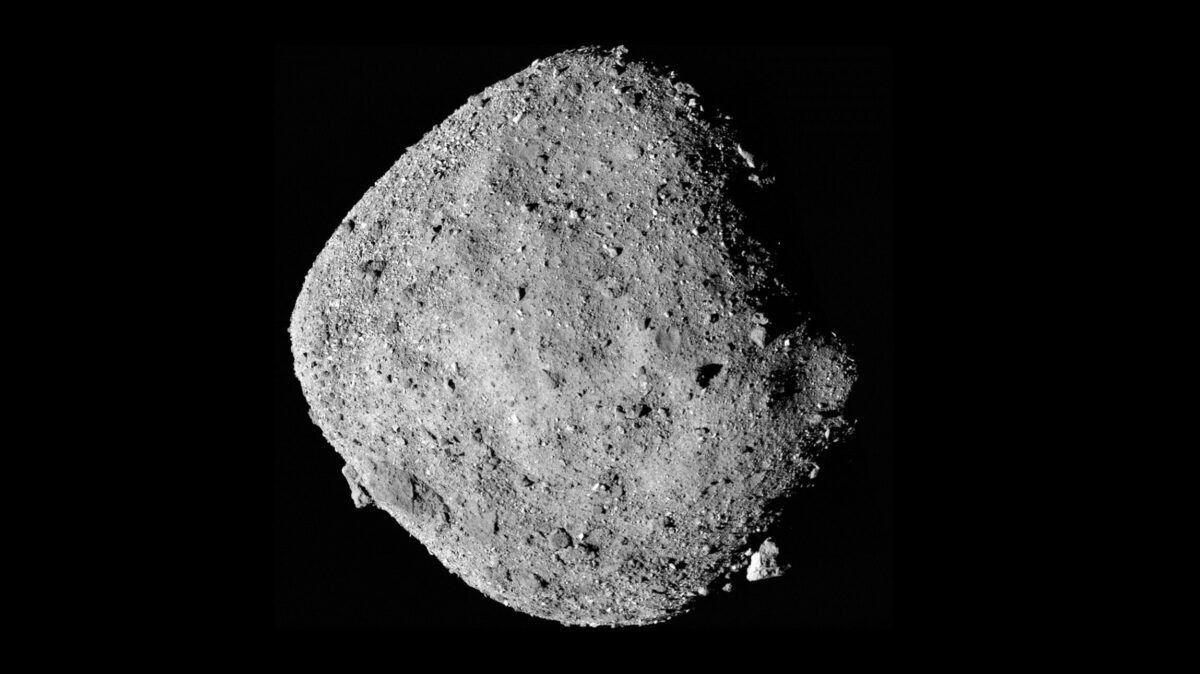

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed: OSIRIS-REx returns samples to Earth, this week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society, with more of the human adventure across our Solar System and beyond. On September 24th, after traversing a staggering 7.1 billion kilometers over seven years, NASA's OSIRIS-REx spacecraft triumphantly delivered a sample from asteroid Bennu to Earth. Joining us to recount her firsthand experience at the sample return in Utah is Rae Paoletta, the director of content and engagement at The Planetary Society. She'll introduce us to Mike Puzio, the young man who named asteroid Bennu, and his father Larry Puzio. Then Danny Glavin, the co-investigator for OSIRIS-REx, will share the next steps for the asteroid samples and the spacecraft. Make sure you stick around until the end for What's Up? with Bruce Betts, the chief scientist of The Planetary Society, as we digest this huge moment in space history. If you love Planetary Radio and want to stay informed on the latest space discoveries, make sure you hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcasting platform. By subscribing, you'll never miss an episode filled with new and awe-inspiring ways to know the cosmos and our place within it. OSIRIS-REx's mission launched in September 2016 with a primary goal, to retrieve a sample from asteroid Bennu. Samples of asteroids like Bennu can teach us a lot about the early Solar System and potentially about the origins of life on Earth. These primordial relics have remained largely unchanged since the early days of our Solar System over 4.5 billion years ago. The tricky part is snagging the samples from the asteroid and then bringing them back to Earth for analysis. After reaching Bennu in December 2018, OSIRIS-REx faced the challenge of collecting a sample from a terrain that was far rockier than anticipated. Of course, in October 2020, the spacecraft team succeeded in high-fiving the asteroid with its TAGSAM device, gathering pristine material from the asteroid and then preparing to make its way back to Earth with the precious cargo. And now after an intense journey through space and the Earth's atmosphere, the sample return capsule bearing bits of Bennu touched down in the Utah desert on September 24th, 2023. Rae Paoletta, our director of content and engagement at The Planetary Society took a trip to the Utah Test and Training Range to witness the historic moment that the samples came down. Hey, Rae.

Rae Paoletta: Hey. How's it going?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Doing well. Welcome back from your epic adventure to go see OSIRIS-REx sample return. That sounds like so much fun.

Rae Paoletta: It was epic. It was surreal. It was all the things. I'm really happy. I'm really, really thrilled about it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Where did you have to go to see these samples come down?

Rae Paoletta: I was staying in Salt Lake City, Utah. And in order to go see the samples, we actually had to drive about an hour and 15 minutes into the Utah Desert to the Dugway Proving Ground which is an active US military base. And it was just a really interesting experience because I ended up going there. I left my hotel at 4:00 AM, and driving into the desert at 4:00 AM was something I don't think I will forget anytime soon. It was completely pitch black, could barely see the road in front of me. It was just an unreal experience.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How many people were with you as you went out there?

Rae Paoletta: Just the driver was the only other person with me. By the time I ended up getting to the base, I think it was about 5:15 in the morning. And I just remember looking up and the only thing I could see was all the stars, every constellation. It was no light pollution, really. So it was really cool. As somebody who doesn't get to see that very often, it was just beautiful. Just taking a minute to look up at the sky and see that was pretty surreal. The place that I was dropped off was not the final destination of the journey. I actually had to go to a different part of the base that all the media, myself included, we had to go on this bus that took us there. And because it was so dark outside, I actually can't even tell you really where I went. I have no idea. I couldn't point it out to you on a map. I forgot to mention that it was also 38 degrees Fahrenheit so I'm really glad I wore layers that day because oh my gosh, the way that the temperature fluctuated throughout the day was so extreme. I was not prepared for that at all. But it was all worth it because it was one of the coolest experiences I've ever had in my whole career. Getting to actually see... No one really saw the sample actually drop out of the sky. Even the NASA reporters who were closer to it didn't see it because it was so tiny. But when the helicopters that left the military base that I was at, when they came back with the sample, all of us could see this helicopter just soaring through the sky with this little thing dangling from it, and that little thing was the sample capsule. And so everyone was cheering and it was just like watching your favorite sports team win times a thousand. The energy was absolutely incredible. I will never forget that moment.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It feels like it was such a short time ago that OSIRIS-REx was actually gathering these samples, but it was actually three years ago that the whole TAG sample return thing happened. And then now this moment of the samples finally returning to Earth and us getting to test them, that just seems like such a culmination of so many people's careers. And I can't wait to find out what's inside there.

Rae Paoletta: I know. I was actually one of my favorite moments from the whole experience was watching Dante Lauretta, the principal investigator on OSIRIS-REx, get out of his helicopter which is really cool. He got a little helicopter for himself as he deserves. And watching him get out after we got the samples back and everybody just cheering and going nuts and he was pumping his fist, I was so happy for him. I think everybody felt super emotional. And we all felt involved in a weird way, and it was just a wonderful moment. I'm sure it was full circle for him and for the whole team, really, just so many people. It took a village. And we're just getting started in a way.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That must've been really cool to be with that many people for that moment. Because I know so many of us were watching the live stream online and cheering at home, but just being there with the people in that moment in history and feeling all their emotions and energy.

Rae Paoletta: I was so overwhelmed when I saw, like I said, the sample capsule in the sky. I was so fixated on it and all I could think about was, "What is in there?" We are literally getting essentially the rocky material from something that is 4.6 billion years old. I was just stunned and all I could think about is, "Wow, I cannot wait until they open this thing up. I cannot wait until they look and see what's inside there." There's so many questions that could be answered. There's so many new questions that could sprout from it. One thing that I was also thinking about this parallel moment I had is the day before the sample return, I went to the Great Salt Lake, because as I said, I was staying in Salt Lake City. And the Great Salt Lake is almost like an alien world. What can live in an area that has such high salinity are these kind of extremophiles, right? It's bacteria that can live in there and not only live but thrive under those conditions. And so I think it was a really interesting experience for me to have that the day before because I was thinking about asteroids and I was thinking about, "Well, what can they tell us about life outside of Earth and what can persist elsewhere?" I think that the exciting thing is that none of us know the answer right now, but I think we're going to get a little bit closer.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. We're about to be showered in papers as people analyze these things with spectroscopy, just really get on in there. Oh, man. Just to feel one of those pieces in your hand. I know I'd contaminate it, but it'd be so cool.

Rae Paoletta: I know.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: While you were there, you got to talk to a lot of cool people too, right? Who were the really exciting people that you got to interact with?

Rae Paoletta: Yeah. Of course I was one of many people who was sitting in the media pool, getting to chat with Dante Lauretta. I didn't speak with him directly but I was there when he came back, so that was really awesome to see how excited and how relieved he was. I also got to speak to Daniel Glavin, who's a senior scientist with NASA Goddard, who is working on OSIRIS-REx and is also involved with Mars sample return. Really, really smart guy, very friendly, has a lot of really interesting thoughts about Mars sample return. Definitely go check out his work. I got to talk with a lot of different reporters too, a lot of media friends, old and new. And I do want to give a very special shout out to all my friends at Utah State who kindly drove me to not only the place I was supposed to go to the military base, but on the way back drove me all the way home to Salt Lake City. And we went on this epic adventure through the mountains. It was a very Lord of the Rings, very fun mountain adventure times among friends. So shout out to all of you if I hope you're listening to this. That was so kind of you. I will never forget that kindness of complete strangers.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's my experience, especially at these science conferences and science events. The people there are just in this state of such joy and comradery and celebrating what we were doing together in space exploration, and the kindness of strangers in those scenarios is something that definitely sticks with me.

Rae Paoletta: Yeah, it really makes me feel like we're all part of this cosmic big space family, and that's really nice to see too. It's just a wonderful group of people. I think the funniest part though is honestly when I got home. Because I had been awake for so many hours and because I was in the literal desert, when I got back to my hotel, I looked in the mirror. My eyes were so red from all of the dust. My face was so red from the sunburn. It was truly a sight to behold.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: The hazards of going to see samples return from another world.

Rae Paoletta: Totally worth it. 10 out of 10 would do again.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I'm really excited to share some of your conversations with people on the show and hear that we're going to hear from Mike Puzio who has a lot of history with The Planetary Society and gives us a really deep connection with this mission.

Rae Paoletta: Mike and his dad Larry are phenomenal. They're like ambassadors of Earth to other planets. They are shining examples of human beings, wonderful people. And I'm really glad that I got to speak to them both. They have such a rich and deep connection to space. And there's something so wholesome about the way that space brings people together, and I just think it's such a cool story about a father and son who had this shared love of space going off into the world and getting other people excited about it too. It's what we try to encourage here at The Planetary Society, and I think that they really embody that.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, we're about to share that conversation. And I'm so glad you got to go on this adventure because we can't send everyone on the team to go see this thing fall out of the sky. But someone had to, and you just have this just infectious enthusiasm. So thanks for sharing your experience with us.

Rae Paoletta: Oh, it's my pleasure. Thank you so much.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: In 2013, before OSIRIS-REx began its epic sample return adventure, The Planetary Society ran one of our classic naming contests. 8,000 entrants from around the world submitted new names for what was then known as asteroid 101955, 1999 RQ36. A young man named Mike Puzio submitted the name Bennu after an Egyptian deity typically depicted as a heron. He said that the OSIRIS-REx solar panels looked like wings and that its touch-and-go sample mechanism or TAGSAM arm resembled the curved neck of an aquatic bird. For Mike, naming Bennu was the beginning of something bigger than an asteroid. He spent the last 10 years serving as an ambassador for the OSIRIS-REx mission, inspiring people from all walks of life to get excited about space. Rae caught up with Mike and his dad Larry Puzio in Salt Lake City, Utah, the weekend of the OSIRIS-REx sample return. They discussed how missions like this can change lives for the better.

Rae Paoletta: Before we even talk about Bennu or anything, I would love to know what your space origin story is. When did you first catch the space bug?

Mike Puzio: That would probably be when my father took me to my first what was then called Astronaut Rendezvous back in I was about eight at the time. So it was just a bit after I had submitted the name, which is honestly incredible that it all panned out that well.

Rae Paoletta: And then I would love to ask you the same, Larry.

Larry Puzio: Oh, I've really been into space since I was a kid and grew up watching Star Trek. Gave it up through college and med school thinking, "Wow, I got the bad eyes. I couldn't be an astronaut." And the last decade, I've really gotten back into it. When Mike was learning to read, I want to make sure he had lots of books about space and science.

Rae Paoletta: I think that the books and all of this learning has definitely paid off or at least been really relevant in this chapter of what we're talking about here with coming up with the name for Bennu. I actually watched an interview with Emily Lakdawalla, our former senior editor, and she conducted that with you and you, Larry, as well when you were about nine, I think. And so the contest that The Planetary Society helped to run, Name That Asteroid, if you remember, it had around, I think, 8,000 entrants. What made you decide to enter?

Mike Puzio: Well, my father said for me to give it a shot, and it was the worst thing that could happen is that they would say no to my name. And it turns out that didn't happen, which I'm very grateful for. So why not is really the only reason why.

Rae Paoletta: And I thought what was so cool about the name is I also was, I just loved Ancient Egypt when I was a kid. And so I'm wondering, did you read books about Ancient Egypt? What inspired that for you?

Mike Puzio: I've been a big Rick Riordan fan since around the third grade when I was reading the Percy Jackson series which was about the time that I named the asteroid. And then later I found The Kane Chronicles which was about Egyptian mythology, and that was even cooler now that I had the whole Bennu named asteroid to work with. So I had a little piece of investment in Egyptian mythology. Well, after the mission name had been announced as OSIRIS-REx, I recognized the name Osiris as an Egyptian deity and I went on Wikipedia to look up stories about him. And one of them that stood out was his return to Earth as a Bennu or a heron, and I figured that would be fitting as the asteroid would be returning a sample to Earth.

Rae Paoletta: Do you remember what it was like the moment you won? Can you describe what did... Did people at school find out? Did you tell them? How did that all go?

Mike Puzio: When I found out, I didn't quite know how to take it because I had never had this experience. I'd never seen this experience from anybody else. And so eventually at some point, I asked our principal if that would be okay for it to be part of the morning announcements, which she had. And she said, "That would be phenomenal." That was just how a lot of my classmates found out.

Rae Paoletta: Over the morning announcements, very cool. What was it like working with The Planetary Society during that time? Did somebody from our team actually contact you personally to tell you?

Mike Puzio: There was this lovely individual named Emily Lakdawalla who's in EMO CAHOOTS with my parents. Initially, she had told them that I had been one of the semi-finalists, but of course my parents didn't tell me then because they didn't want to get my hopes up, which thank you. But I was eventually told by her that I had in fact won the competition, and I was just dumbfounded.

Rae Paoletta: That's so cool. What a great surprise that you kept it. How did you manage to keep the secret that long?

Larry Puzio: Oh, it was just I didn't show him all the emails. But really, I didn't want to get him disappointed at that age. Since it was just by email and he didn't know it, never let him found out until he was approved as the winner.

Rae Paoletta: That's awesome. Looking back at that time, did it feel like winning that contest had ripple effects on other parts of your life? For example, did it inspire you to become more interested in space or science?

Mike Puzio: Well, it did thrust me into the whole space thing. And initially I was a little bit reluctant to actually get into space beyond that because it was more of my dad's thing at the time. But upon realizing how cool space was and after my dad had taken to me to a few space events, I decided that it would be really cool to stick with it. So I decided to get more involved with it, doing all sorts of things such as going to the launch back in 2016 and then becoming an OSIRIS-REx ambassador and giving lectures on it.

Rae Paoletta: Yeah, really it jumpstarted something. So that's really interesting too. And I think that a lot of us in space had these moments too where maybe we didn't come from a formal space science education or something, but there's just these lightning bolt moments in our lives that bring us into the industry, right? So right now, you're at school at North Carolina State. Is that right? And you're studying engineering. What do you want to do with that? Do you eventually want to go into the space sector?

Mike Puzio: Eventually, I'd like to be an astronaut. I'm still clinging onto that little eight-year-old Mike dream.

Rae Paoletta: Repair space shuttles or...

Mike Puzio: Just be on the crew to any mission really. As I think it was John Glenn said, "Any space flight is a good space flight."

Rae Paoletta: Very well said, yes. Couldn't agree more. And it seems like you've given some talks, as you mentioned, about OSIRIS-REx over the years. Can you tell me a little bit about that?

Mike Puzio: It's opened a lot of doors for me to meet and talk to really some really cool people so I'm pretty glad about it. And honestly, it got me to be able to talk to a big crowd.

Rae Paoletta: Yeah, a lot of public speaking experience. What do you hope your personal contribution can be to the field of space now that you've had this once in a lifetime opportunity?

Mike Puzio: All I can hope to do is to inspire other people to do something about space because it's for everyone, and I mean everyone, to get involved in. And it's a really cool part of my life and I hope it can be a cool part of their lives too.

Rae Paoletta: I couldn't agree more. I have a similar experience myself, and I just think that a lot of people, we almost box ourselves out by feeling like it's a gate kept kind of thing that only this small amount of esoteric people with this highly technical understanding were ever going to get into. And then when you realize that there really is space for everybody. There's a lot of meaning in that. So it's been about 10 years now. We're sitting here in Salt Lake City, if you can believe it, ages 9 to 19 though may as well be a hundred years in terms of how much your life changes in that decade. How does it feel to be here now, just a couple of days away from the sample actually dropping, a sample from the asteroid you actually named?

Mike Puzio: It honestly feels amazing because it's just been something for so long, it's just been a big part of my life for that huge amount of time, relatively speaking. Just the whole culmination of it here in this last weekend is something that it's bittersweet thing because I've been looking forward to NASA getting all the data back and getting it to analyze the asteroid sample. However, it's almost over.

Rae Paoletta: And Larry, I'd actually like to ask you the same because I feel like this is a full circle moment for you as well when you were at the launch. How does it feel now?

Larry Puzio: Oh, it's really phenomenal because 10 years ago when he was that young, I figured, "Wow, it'll be a decade before it comes back. I can't imagine what things we'll be doing by then." And it's just been an amazing journey of watching him grow up and watching him get excited about things that I don't even understand all the time, like electrical engineering. But it's really, it's had a great impact on his life. I love how many opportunities we've had because of this and still look forward to even the next part of the mission to catch up with Apophis.

Rae Paoletta: Yeah, I wanted to ask about that too. Because it's like Sunday is obviously a big milestone, but the spacecraft will still be hard at work. So one thing I wanted to ask you that I just think is hilarious is I'm like, did you predict the future? Because now it's going to study Apophis, which was the ancient Egyptian deity associated with darkness and disorder and chaos. And I'm like, how did you pick such a perfect name?

Mike Puzio: It isn't too hard. It's only appropriate that the next asteroid that it goes and collects data from is named Apophis.

Rae Paoletta: Yeah, definitely makes sense with the storyline. So what are you personally most excited to learn about from the Bennu samples?

Mike Puzio: Personally excited for where is the origin of life? Where did we come from? Where are we going possibly even?

Rae Paoletta: And then Larry, I'd like to ask you the same because I think that one aspect of learning about asteroids that I think a lot of people associate them with is planetary defense, of course. And we had the DART mission a year ago, right? Very much in the popular zeitgeist. But a lot of people, I think, don't realize how much asteroids are almost like time capsules of the Solar System.

Larry Puzio: Yeah, it's really amazing. Dolores Hill, one of the University of Arizona specialists, really got us turned onto meteorites. She gave us a tour and that's one of her passions. And meteorites really provide pristine samples because on Earth, everything has been recycled or gone devoured and digested. So there's no way to really study our origins well here. Beginning a pristine sample is a really good basis to start with. And a bit of a change of subject, it also makes me think of one of my favorite T-shirts from the ESA, which, "Dinosaurs didn't have a space program."

Rae Paoletta: Yes, that's excellent. Looking back on your own experience with Bennu and the whole contest, why is it so important to get kids excited about space?

Mike Puzio: Well, those kids are eventually going to grow up. And if they have a love for space when they're a little kid, then they're going to want to do something with it when they grow up. And even then, if they don't do it, then they'll have that nostalgic feeling when a big space mission does occur and then they'll remember how NASA made them feel. So I feel like it's important to always develop a love for space in everyone, especially youngsters though.

Rae Paoletta: Yeah. And Larry, I'd like to ask you the same. Looking back at your experience with this contest and with Mike, why is it important for kids to get excited about space? Where do kids and families fit within this vast space of space, frankly?

Larry Puzio: Well, I've really come to learn how much all of our daily lives are really impacted by developments from the space program. Both the very idea of cell phones, tiny cameras, and even integrated circuits are just from the Apollo program. So much of our modern lives is shaped by that field and nobody seems to be aware or appreciate it. So educating the public really helps.

Rae Paoletta: Absolutely. And just my final question is, do you have a message for our Planetary Society members, maybe something or on some thoughts or reflections since winning the contest?

Mike Puzio: Well, if you have the opportunity to do something that you want to do, take it. I did that and don't think it turned out too bad.

Larry Puzio: I'd say make sure that along with supporting space exploration or The Planetary Society, take the time to write notes to your legislators and really get involved with decisions about space policy. If it's done right, it'll really benefit the entire planet.

Rae Paoletta: And other planets.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll be right back with the rest of our celebration of the OSIRIS-REx sample return after this short break.

Bill Nye: Greetings. Bill Nye here, CEO of The Planetary Society. Thanks to you, our LightSail program is our greatest shared accomplishment. Our LightSail 2 spacecraft was in space for more than three years, from June 2019 to November 2022, and successfully used sunlight to change its orbit around Earth. Because of your support, our members demonstrated that highly maneuverable solar sailing is possible. Now, it's time for the next chapter in the LightSail's continuing mission. We need to educate the world about the possibilities of solar sailing by sharing the remarkable story of LightSail with scientists, engineers, and space enthusiasts around the world. We're going to publish a commemorative book for your mission. It will be filled with all the best images captured by LightSail sale from space, as well as chapters describing the development of the mission, stories from the launch, and its technical results to help ensure that this key technology is adopted by future missions. Along with the book, we will be doing one of the most important tasks of any project. We'll be disseminating our findings in scientific journals at conferences and other events and we'll build a master archive of all the mission data. So every bit of information we've collected will be available to engineers, scientists, and future missions anywhere. In short, there's still a lot to do with LightSail, and that's where you come in. As a member of the LightSail mission team, we need your support to secure LightSail's legacy with all of these projects. Visit planetary.org/legacy to make your gift today. LightSail is your story, your success, your legacy, and it's making a valuable contribution to the future of solar sailing and space exploration. Your donation will help us continue to share the successful story of LightSail. Thank you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What's next for the samples from Bennu and the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft? We turn next to Dr. Daniel or Danny Glavin, the co-investigator of NASA's OSIRIS-REx mission. He's an astrobiologist and a sample integrity scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. He's leading the team that will unravel the mysteries contained within the samples returned from Bennu. He's delved into samples from the moon and meteorites and he's also involved in the Mars sample return mission. I spoke with him just a few days after his return from Utah. Hi, Danny. Thanks for joining me.

Danny Glavin: Hey, it's great to be here. Thank you for inviting me.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I have to say, huge congratulations to you and everyone that's been working on OSIRIS-REx. This is, for me, I feel like the biggest space moment of the year.

Danny Glavin: Yeah. It was incredible. I was out at Dugway at UTTR for the landing. And like everyone, I was just like, "Please work. I want this parachute to open, this precious sample. Please come back safely and uncontaminated." And after putting close to 15 years into this mission, it was really very emotional and stressful until that chute opened, and then I was able to relax for a second. But yeah, it's just incredible that we can do these things. Going all the way out to an asteroid, collecting a sample over 200 million miles away from Earth fully autonomously, pick up a sample from the surface, stow it, and then bring it back to Earth, survive atmospheric entry and landing, and now the sample's going to be literally distributed to labs around the Earth to analyze. So it's really a very exciting time for planetary science.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It is, and that just puts it all in context. Working on this mission for 15 years, that's got to be just so satisfying to see how successfully it came down.

Danny Glavin: Yeah, no doubt. I'm actually honestly still in disbelief about this whole thing. I was telling people it felt like I was a cast member in a science fiction film. We're really doing this. But now samples are back. We've confirmed everybody's seen the images of the sample container open. There's clearly Bennu dust in there, and we're getting ready to open it up further here over this next week. But there's sample there. And so this is real. We have this pristine four and a half billion-year-old asteroid fossil from the early Solar System to analyze. It's just incredible.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I feel too like this mission has had to leap over so many interesting hurdles just because we're beginning to understand things about asteroids and sample return that we've never really had to encounter before. There was that moment where it was actually trying to grab that sample, the touch-and-go maneuver. And when I read how close that spacecraft got to literally almost being engulfed by this rubble pile, I was really amazed.

Danny Glavin: It was scary. And of course we were, because of the time delay, it was I think 18 1/2 minutes or something before the signal could come back to let us know that everything worked. Everything had already happened by the time we're looking at it. But yeah, we went down and we thought it would be more like a pogo stick kind of thing off a hard surface, and it was more akin to literally jumping into a plastic ball pit. We sunk into the asteroid. And none of the mechanisms, we had a spring that was going to activate so that would trigger the back away thruster, none of that went off. So there was no resistance of the asteroid as we plunge the sampler in. And fortunately, the code, there was a timer that triggered the back away thrusters, and we were able to back away and get out of there. But if that hadn't have gone off, if the thrusters didn't work, like you said, we would've been swallowed up by Bennu. It would've been end of mission. But fortunately, these engineers are incredible. They plan for every contingency and they made it happen.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And then immediately after that, you get the samples into the actual sample container. And it was so much sample, it couldn't even close its mouth. I keep trying to liken it to a game of Chubby Bunny. It ate too many marshmallows and just couldn't keep its mouth shut.

Danny Glavin: Yeah. We swallowed a lot of Bennu which was exciting because we got deep and we packed the we call it the TAGSAM collector full. And that was another really frightening, exciting, I don't know what moment of the mission where we're taking images of the sampler head before it was stowed away and there were particles, Bennu particles coming out. As you mentioned, one of the flaps was jammed open by a small stone. And I think the PI of the mission, Dante Lauretta, said at the time, "Every single particle coming out is somebody's PhD thesis." And he was right. He put it in perspective. This is opportunity loss. So that initiated a very accelerated stowage. Originally, we had planned to basically extend the arm with a sample in it and spin the spacecraft around a merry-go-round to make a moment of inertia, basically, measurement to really precisely determine the mass of the sample in the head. But you don't do that if it's a leaking sample. And so it was within days that we were able to get the thing tucked away, accelerated scheduled to get it stowed and safely sealed in the sample return capsule. So good news is we know we didn't lose everything. We know that. We've got I think the mass estimates were something like 250 grams with an error of 100 grams, but we were convinced we met our requirement of 60 grams. Yeah, we'll know soon here, hopefully in the next this week or so, what the actual mass was. But there's definitely a sample in this collector.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's got to be really cool for you because I understand that you've just been gearing up to check out these samples for a while. This is your bread and butter.

Danny Glavin: Oh, yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What are you most excited about finding in these samples?

Danny Glavin: Yeah. For my career over the last, I would say, 20 years or so, I've been studying organic compounds, the building blocks of life in meteorites. So amino acids that make up all of our proteins and enzymes, nucleobases. These are the components that make up the genetic code in DNA and RNA. And so we've been searching for these building blocks of life in meteorites, basically trying to test this hypothesis that meteorites from asteroids like Bennu could have delivered the seeds of life to the earlier Earth and maybe other planets, which then helped give rise to life. So we're going to be testing that hypothesis one full swing with Bennu for sure. And one of the frustrating things analyzing meteorites is that they've been contaminated. As soon as they hit the atmosphere, they're heated. They're exposed to the atmosphere. They hit dirt or ice or wherever they land on the Earth and immediately start being contaminated by terrestrial organics. And we don't have that problem with Bennu, especially now after the successful soft landing of the sample return capsule. These samples are going to be very clean. And what that means is if you did start detecting organic compounds, you can really trust the results, that these are organics that were formed in space on this asteroid and it isn't contamination that came into the sample later. So I'm really excited about that testing. Again, this hypothesis that the prebiotic organic compounds that led to life on Earth and maybe elsewhere like Mars could have come from asteroids like Bennu.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Wouldn't that just be such a realization? Everything we're testing out there seems to have these organic compounds on them, but actually getting to analyze them in a lab, see how complex they are. One of my friends was even like, "I wonder if there's RNA on that asteroid."

Danny Glavin: Yeah, we'll see how far we go. And again, I think because these samples are likely to be very clean, that if we do detect more complex RNA-like peptide structures, we can maybe start to trust the results. So far with meteorites, we've never seen anything that complex that wasn't contamination. So we see the building blocks, the amino acids, nucleobases. We see sugars like ribose, but nothing as complex as a nucleic acid or a nucleotide. But we'll certainly be looking for those more complex polymers in these Bennu samples.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I think what's cool too is that this isn't the first time we've actually successfully brought samples back to Earth. Of course, it was the Japanese space agency, but we already have samples of asteroid Ryugu. So now that we have these things, we can begin to compare the makeup of these and see how organic compounds compare between these two different bodies.

Danny Glavin: Yeah, this is really important. And I was following social media during the landing, and I know there were a lot of people getting outraged with, "This is the first asteroid sample return," and all that boasting when, as you pointed out, JAXA, Japan did it first with Hayabusa, the first one from asteroid Itokawa. Only returned about a milligram of sample so a small amount of material. And then more recently, the Hayabusa2 mission which went to Ryugu returned about 5.4 grams. And of course, with OSIRIS-REx and Bennu, we're hoping for maybe a couple of hundred grams. We'll see. We'll know for sure. But my whole point is let's not talk about who's first and this and that. This return of samples from Bennu is really going to enhance the science value of all of these missions, Hayabusa, Hayabusa2, and O-REx for exactly the reasons you said. We're going to be able to compare these asteroids to each other and compare the organic chemistry. And if we detect, see how common these compounds are. So I'm really excited about that comparison actually as well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: This is just one of the things that OSIRIS-REx has accomplished. But now we're off on a whole new adventure after this starting into OSIRIS-APEX, and then we'll get to go take a look at asteroid Apophis, which I am super excited about. I don't know about you, but this is really exciting for me because I think the whole world is about to be completely wowed by Apophis in 2029 and they don't even know it yet.

Danny Glavin: Yeah. Apophis, just to clarify, I'm not part of the APEX mission. I'm fully on OSIRIS-REx sample analysis, but I have friends that are involved in the mission. But indeed, it's going to be really exciting in 2029. I'm told that you'll be able to see Apophis moving across the sky with your eyes at night, and so it's going to be that close. It won't hit us. We know that for sure. But yeah, we're going to be taking OSIRIS-REx spacecraft. We don't have a sampler system so we're not going to be able to sample Apophis and bring back sample, but we have all the instruments that we used to analyze Bennu and we're going to be able to make those comparisons between Apophis and Bennu from the spectroscopy measurements. And it's also kind of cool. After Apophis passes by Earth, OSIRIS-REx or APEX will rendezvous with Apophis and actually go down to the surface and fire the thrusters to spray the dirt, if you will, from the surface and make measurements to try to see what it looks like underneath the top surface as well, investigate space weathering and all that kind of stuff. So yeah, it's going to do some really cool science and yeah, I'm glad it's not the end for OSIRIS-REx. It's another asteroid to go to, so that makes me happy as well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: When is it actually going to rendezvous with the asteroid? Is it possible to get images of the asteroid and the Earth together?

Danny Glavin: Yeah, that's a good question. I would assume it would be cool to have an image of Apophis in the Earth. But yeah, just I don't know enough about the details to comment on that. You have to talk to somebody else on the APEX team to find out.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We have a few years to figure it out. I just know what that image would mean for planetary defense. That would be so cool.

Danny Glavin: Yeah, no doubt. No, planetary defense, that's the other side of this. We talk a lot about the science and learning about the origin of the Solar System from the sample's return from Bennu. But the other aspect of this is planetary defense. It's no joke. Bennu is characterized as a potentially hazardous asteroid. I think in, what is it, September 24th, 2182, if I get that year right, there's a very small chance it could hit the Earth. And Bennu is big. This is the size of the Empire State Building. It would be a bad day if Bennu hit there. But by studying these samples and studying the makeup of Bennu, the physical properties of the rocks, we'll be able to put ourselves in a better position to design a mission if we have to deflect the asteroids so that it doesn't hit the Earth.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I'm really glad. I feel like when I was younger, I was absolutely terrified by the idea that there were all these asteroids and comets out there and we weren't actively doing anything to really make a plan for what to happen if something came in. But we're actually at this point now where we're getting samples back from asteroids. We're getting up close to these asteroids with imagery. We even had the DART mission that went and slammed into an asteroid. So now I feel like we're actively in a good place here.

Danny Glavin: It is important. The DART was an extremely important mission. It showed that we can actually change the orbit of an asteroid by hitting it. That was unknown, actually. And I think they were actually even more successful than they thought. They deflected it even more. But yeah, it's really the approach is we got to be studying these materials in the lab. We got to be looking for asteroids, especially the smaller ones. So there's a whole survey that needs to happen so that we can find them. And that's really the key with planetary defense. You need to find them early so that you have a decade, 10, 20 years to plan how you're going to move it if needed. And so that's really the key. I know NASA's really been focused on just the survey aspect, just finding these things out there. But I'm with you. I'm glad we're paying attention to this. You look at our history on Earth and just look at the moon. Our history is a series of impacts. It happens and they can wipe out, man. Wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. We need to pay attention to this. And just to clarify that your audience should not be worried about Bennu hitting us in the next 150 years. There's basically no chance that Bennu can hit us. So we're really looking, again, many years down the road. But still, we need to be prepared for the possibility that something like this could happen sometime in the future.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, got to protect the creatures of Earth. And we're doing a pretty good job, I feel.

Danny Glavin: Absolutely, yep.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: What was it actually like for you there at the actual sample return? Did you guys celebrate afterwards? What was that like?

Danny Glavin: I think everybody had their own individual experience. I guess one of the things that was surprising to me is everybody was emotional, and especially after the parachute opened. And I hugged a lot of people, people that I wouldn't normally hug, and we were just hugging and it was great. We were just that moment of just relief, all this time put into the mission just let go. I know that the PI, he said this to the team but when the shoot opened, he cried on the helicopter. He got teary-eyed. And I know Dante very well and I don't think I've ever seen him cry. So that I think for him, it was just a release as well of all the stress. And we made it. We did it. And it was a great celebration. When the chute went open, there was a huge cheer, a huge roar. Everybody knew that at that point we were safe, that this really worked. The seven-year journey really worked. So it was a big relief.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's got to be. It's such a complicated feeling. It's one part relief that it actually worked, but also just the culmination of so many people working together on such a complex task. And having it come together, that's a beautiful moment.

Danny Glavin: Yeah, no doubt. And just so excited about what's to come. In some ways, even though I've been involved in this mission for almost 15 years, it feels like it's the start of it for me now as a sample analyst. This is what I've trained for and what our team of, we've got over 200 laboratory scientists that have been just ready for this moment, ready to go on these samples. And I can't tell you how excited I am, not only for the two years we have to analyze, but just decades to come. I'm going to be reading even after I'm retired, I'm sure I'm going to be reading about something new that was found from asteroid Bennu. And just to know I played some small part in making this happen is just really gratifying.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: All these decades later, we're still seeing papers written about the moon samples. It's going to be decades and decades. We're going to be talking about Bennu. Where are the samples now? I know you said they're going to be parceled out to different labs around the world, but where are they in this moment?

Danny Glavin: Right now, the samples are at Johnson Space Center. Most of the stuff, that's in one of these giant nitrogen glove boxes because we don't want to contaminate. So it's just clean nitrogen that these samples are being exposed to. And the curation folks are busy sweeping the material off the deck and collecting a sample. A small part of that has been allocated to the, we call it the Quick Look Tiger Team for just some basic mineralogy analysis, some basic optical ,just looking at it under the microscope, understanding its meteorology, the different types of rocks. And that work is happening now. And maybe some of that I think will be presented at the October 11th NASA reveal event at 11:00 AM Eastern time. So certainly they'll probably brief. There'll be a briefing on some of those findings, but we can't talk about any of that now. We'll have to wait until October 11th. But I can tell you these samples will be going out. I think we've got, as I mentioned, 200 scientists, something like 35 labs around the world who will be getting these materials to study using the best techniques available. And these samples, probably by end of this month, November timeframe, most of these folks will have samples, and it's going to get really exciting at that point and I think the data's just going to start flooding in.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That is really exciting, and I'm glad you brought that up. We're recording this early. So for us, we actually have to wait for those results to be public. But everybody listening to this will be able to go and immediately watch that press conference because it comes out on the day that this episode airs on October 11th. So it's perfect timing.

Danny Glavin: I think with the amount of sample we've returned, what we're able to do on very just tiny amounts of material, we can make measurements on micrograms, a millionth of a gram. There are techniques that can look at very small particles. So we're going to have sample mass available for generations of scientists to look at, and I hope some of your listeners thinking about getting into research and scientists someday maybe be looking at this material as well in their own labs with techniques that weren't even around today. That's one thing that I think people forget is that these sample return missions, it really is a gift that keeps on giving. There are limits to what we can do now, but 10, 20, 30 years later, there's a new technique, a new instrument technology, and we can look at the samples in different ways and honestly ask questions we didn't even know how to ask right now. I love that about sample return. The bottom line is this is just so much bigger than the OSIRIS-REx team. This is really for humanity and inspiring the next generation and just learning new things over generations. So it really is exciting to me.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It really is. And we saw it with the young gentleman who named Bennu when he was younger through one of our competitions, Mike Puzio, just seeing the arc of someone's life getting interested into space when they're younger and then seeing them carry that into a career when they're older. I'm totally sure that there are kids these days that are hearing about this mission and are gearing up to test those samples someday. It's beautiful.

Danny Glavin: Yeah, no doubt. And you mentioned Mike Puzio. I'll just say a little side story. So we were at the OSIRIS-REx celebration event this last Saturday at the South Shore Harbor in Texas near Houston. And Mike Puzio was there. And I'm like, "Oh man, I got to meet this guy." Asteroid Bennu was not always asteroid Bennu. It was 1999 RQ36, and he won a contest to name Bennu. He was nine years old at the time. And so here we are. That was back in 2013. Here he is as an adult, a 19-years-old guy. So I met him, we got a funny picture together, and he's actually wants to be an astronaut. I thought that was really cool. So he's been inspired to pursue space in that way. But yeah, it was just really nice seeing him there and chatting with him.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I just can't wait. There's so many things to look forward to in the future for sample return. This is just one more asteroid, but we're looking at a future where we'll be able to return samples from hopefully Mars someday. And when we get all these samples together, start comparing across the Solar System, the things we'll be able to learn about our Solar System's history will be just probably far beyond what we're imagining right now.

Danny Glavin: Well, there's no question. And I can tell you every sample return mission, we learn something new and exciting and different. And I'll go back to the Stardust mission, return samples from comet Wild-2, this is NASA's Stardust mission from the tail. Just dust grains, something like a milligram. And just from that milligram of dust from the comet, we learned that material was flying all over the place in this Solar System. We found grains. These mineral grains that could have only formed at high temperature near the sun out where comets are near Jupiter. How did that stuff get out there? So the entire Solar System is just this giant mixing, and that led to new models about the outer planets moving around, flinging stuff in, and stuff going out. And this is all from one milligram of sample. And so there's no doubt that I think the analysis of the Ryugu materials, the analysis of samples from Bennu, we're going to be literally rewriting the textbooks on Solar System formation and evolution.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We really are. It's just a really great, exciting time to be a space fan. And I'm just so relieved that the samples came back. Well, they're safe. We're about to do all this awesome science, and it's just a good time to be alive. Thank you so much to you and everybody who made this mission possible because this was a triumph.

Danny Glavin: Yeah, you're welcome. I don't even know how to express my emotions right now. It's just we're in the middle starting the sample analysis. This mission worked. Like you said, there's so many other things to do and look forward to, Mars sample return. Maybe one day we'll get a sample of a comet nucleus back to Earth as well. But it is. It's no doubt it's a really exciting time to be in planetary Science right now.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks for joining me, Danny, and for taking the time. I'm sure you and everyone are very busy gearing up to test these samples, so I appreciate it.

Danny Glavin: You're welcome, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Now, let the science begin. Happy analysis to all the scientists around the world that have been looking forward to these samples. And again, a huge congratulations to everyone that's worked on the mission over the years. Now, let's check in with Bruce Betts, the chief scientist of The Planetary Society for What's Up? What's up, Bruce?

Bruce Betts: Hey, Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's so cool to finally see the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft deposit its samples back on Earth. And I feel like timeline-wise in my brain, I started working with you guys just a little bit before that TAG sample return snatchy maneuver.

Bruce Betts: That's the official term, I believe.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But definitely, yeah. No, the fact that they called it TAG. Come on, touch-and-go.

Bruce Betts: No, it's true. They did.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I think that's what that stood for.

Bruce Betts: Yes, it is. Yes, it is. No, it's super exciting. And you've been involved since then and I've been involved since, well, school books were written on stone. But I've been involved since they started proposing this mission a very long time ago. And when I say I, I mean The Planetary Society did some education outreach with this and naming contests and sending names that have gone out and come back and are going and flying around. And there's really great signs and it's really exciting, and they made it back and it looks great, and they got rocks and they're from another place. And it could tell us about the early Solar System and the formation of everything and what came to Earth in terms of water and in terms of organics, and it's really exciting.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: There is though. It's nice to hear you so excited about something. I feel like we succeeded so hard at this. I'm so excited to see what they find in those samples and then compare them to the samples that JAXA got and see what's going on there. We could learn a lot.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, it's awesome. And they have a really long acronym, and now they're transforming into OSIRIS-APEX and going to make all those little people at Planetary Defense Conference and also the Apophis workshops that happen every year now happy that at least a spacecraft will be going to Apophis when it comes super close to the Earth in 2029. At the very least, we've got a really cool functional spacecraft going there so check it out and see what happens to an asteroid, a 300-meter asteroid, when it flies closer than the geostationary satellites and what gets shaken around and what happens.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I can't wait for that to scare everyone. Not because I like people being scared, but because we need to be doing more for planetary defense. We've done a lot, but there's still a lot that can be left to accomplish.

Bruce Betts: Oh, yeah. No, we have a long way to go. And by the way, as far as I can tell, you do enjoy scaring people.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Maybe a little.

Bruce Betts: But yes, there's a noble goal behind this one. Last week we talked about favorite conferences. There are now Apophis workshops every year. Just counting down the years until the fly by because of the science, try to make sure we get the science and planetary defense potential out of such an awesome opportunity. You can road trip to Europe to see it in the night sky.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I would love to. I would absolutely do that. That would be-

Bruce Betts: Or somewhere else. I don't remember exactly where all it...

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, I think Europe was the location, Europe and Northern Africa. I'll have to look that up but I think that's right. But I have to ask you this.

Bruce Betts: Uh-oh.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Who do you think is behind the ridiculous OSIRIS names? Not because I don't love them, but going from OSIRIS-REx to OSIRIS-APEX is very Jurassic Park.

Bruce Betts: Very Jurassic Park?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. They had those new Jurassic World movies where they took a Tyrannosaurus Rex and turned it into an Indominus Rex, like the whole next level. I feel like that's what we did with the spacecraft.

Bruce Betts: Now, that was the product of some people looking. They had an opportunity and could they make the orbital dynamics work out with the fuel onboard to be able to do it. So yes, they've transformed into a different kind of space-o-saurus. There is precedent for this with other spacecraft already, including name changes, although I don't remember all the name additions that they use. But Stardust dropped off samples of a comet and went off and checked out the Ask The Comet. That Deep Impact had hit with an 800-kilogram ball of copper and Deep Impact after it dropped his 800-kilogram ball of copper went and looked at another comet. People who've gotten creative this way before, and I just never imagined that they were dinosaurs.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I just really liked dinosaurs when I was a kid, and I feel like that's part of why I'm so in love with planetary defense. We owe it to them. They didn't have a cool space agency. They didn't have multiple cool space agencies. They didn't have any way of knowing how to protect themselves.

Bruce Betts: I don't know that we'd be here if the dinosaurs were still chomping around. So way to go, us.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's a fair point. We might not have a-

Bruce Betts: Planetary Radio.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right. Planetary Radio would not be here without the Chicxulub impact. You heard it here.

Bruce Betts: What a headline.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Sorry, dinosaurs.

Bruce Betts: All right. I've got complex facts so maybe we should... Wait, large dog coming by. You want say it? My dog does look remarkably like Scooby. All right. He says, "Get on with it." All right, all right. Dude, I'm trying to do a show here. We've talked about this. So the moon, that thing in the sky, that disc thing, it passes in front of planets. It passes in front of stars. It's cool. It's called an occultation. It occults them. But what's seen here is always interesting to me is that you can see those from one part of the world but not another part. Well, it turns out the moon is so close to us, so to speak, compared to the sky, that the moon actually, the position of the moon in the sky varies by as much as two degrees on the sky from one part of the world to the farthest other part of the world. Considering the moon is about half a degree in diameter, that's like four moon diameters difference and where it appears. So this is why it's particularly localized. I relatively localized these occultations of things because I've wanted to share those in various media of, "Hey, you can go see an occultation." But then I realized, "Oh, well not two thirds of the world, so nevermind." But you can look them up. It's cool. Things disappear. People get cool pictures. There you go.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. Sometimes I like to watch those live streams, or I've even worked some of those live streams in the past from Griffith Observatory. So if you can't watch it from where you are, if there's an occultation coming up, you can always find someone's live stream online, which is the power of the internet.

Bruce Betts: Wow. I did not see that turning into an ad for the internet. Is that internet thing going to stay, do you think?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: All right, let's take this one out.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody. Go out there, look up the night sky and think about your mind expanding into the universe and then pulling it back in because Sarah's got too scary. Thank you. Good night.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week to talk about diffraction solar sailing. You can help others discover the passion, beauty, and joy of space science and exploration by leaving a review and a rating on platforms like Apple Podcasts. Your feedback not only brightens our day but also helps other curious minds find their place and space through Planetary Radio. You can also leave us your space thoughts, questions, and poetry at our email at [email protected]. Or if you're a Planetary Society member, leave a comment in the Planetary Radio space in our member community app. Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by our patient sample return-loving members. You can join us as we support sample return missions like OSIRIS-REx at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor. Josh Doyle composed our theme which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. And until next week. Ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth