Planetary Radio • Jul 05, 2023

Humans to Mars by the 2030s? NASA Associate Administrators weigh in

On This Episode

Nicola Fox

Associate Administrator for NASA’s Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate for NASA

Jim Free

Associate Administrator for NASA’s Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate for NASA

James Reuter

Former Associate Administrator for NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

It's going to take a lot of collaboration to get humans to Mars, but we're up for the challenge. This week on Planetary Radio, Mat Kaplan, senior communications adviser at The Planetary Society, takes us to the 2023 Humans to Mars Summit in Washington, D.C. We'll share his conversation with three NASA Associate Administrators, Nicola Fox, James Free, and James Reuter about the international, commercial, and robotic collaboration it will take to put the first humans on the Red Planet. Then Bruce Betts and Sarah Al-Ahmed share What's Up in the night sky and a chance to win a grab bag of prizes in one of our last space trivia contests.

Related Links

- Explore Mars homepage

- Humans to Mars Summit

- Every mission to Mars ever

- NASA CLPS Moon landing missions

- The Night Sky

- The Downlink

Trivia Contest

This Week’s Question:

Who was the oldest person to go to space?

This Week’s Prize:

Space prize grab-bag.

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, July 12 at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Question from the June 21, 2023 space trivia contest:

What is the closest nebula to Earth?

Answer:

The Helix nebula is the closest nebula to Earth.

Last week's question:

Approximately how thick is the heat shield that protects the Parker Solar Probe?

Answer:

To be revealed in next week’s show.

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's going to take a lot of collaboration to get humans to Mars, but we're up for the challenge. This week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of the Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. A few weeks ago, Mat Kaplan, the creator of this show and now senior communications advisor at the Planetary Society, took an adventure to the Humans to Mars Summit. It's hosted by our friends at Explore Mars. We'll share his conversation with three NASA associate administrators, Nicola Fox, James Free and James Reuter about the international commercial and robotic collaboration that it's going to take to get the first humans to Mars. Then Bruce Betts and I will share what's up in the night sky and a chance to win a grab bag of prizes in one of our last space trivia contests. And now for some space news, the James Webb Space Telescope or JWST has found signs of an essential carbon molecule in a planet forming disc, methenium, also known as methyl cation, is a carbon compound thought to play an important role in our organic chemistry by building more complex carbon molecules, which are the foundation of life as we know it. JWST once again proved its astonishing sensitivity when it detected methenium in a proto-planetary disc in the Orion Nebula. Researchers have found an object that blurs the lines between planet and star. The object is a brown dwarf, a class of celestial objects that typically is hotter than a planet, but cooler than the coolest red dwarf stars. This particular brown dwarf has temperatures hotter than those of the sun, although it's just on one side. This is because that side of the brown dwarf faces an near nearby white dwarf star. This new discovery is shedding light on classes of objects that defy our usual categorization. Meanwhile, in Europe, ESA is taking big steps to reduce orbital debris. The European Space Agency and three European satellite manufacturers recently announced plans to address the issue of potentially dangerous debris in Earth's orbit. They're developing a zero debris charter that would hold signatories responsible for deorbiting their satellites at the end of their operating lifetimes. And lastly, the Mars sample return Mission is facing challenges. The NASA program, which aims to collect and return to Earth the samples of Martian regolith that the perseverance rover has been selecting and caching, is undergoing a second independent review amid growing cost estimates and daunting technical and managerial challenges. Planetary Society Chief of Space Policy, Casey Dreier unpacks this issue and explains how it could affect other planetary science missions in one of our newest articles. You can read Casey's article and learn more about any of these stories in the June 30th edition of our weekly newsletter, the Downlink. Read it or subscribe to have it sent to your inbox for free every Friday at planetary.org/downlink. And now for our main topic of the day, how do we get humans to the Red Planet. Explore Mars' annual conference, the Humans to Mars Summit, was held on May 16th through 18th at the National Academy of Sciences Building in Washington D.C. U.S.A. The conference brought together leaders from NASA, commercial and industrial space companies, international leaders and STEM professionals to think about the next steps that it's going to take to get humans to the Red Planet. And if possible, accomplish this mind-blowing feat by the mid 2030s. It's going to take a lot of teamwork to get the first humans to Mars, but can you imagine what it would mean for humanity? Our friend Mat Kaplan, who created this show and is the former host of Planetary Radio, is now our senior communications advisor at the Planetary Society, and he hosted a panel at the conference with three NASA associate administrators, Nicola Fox from the Science Mission Directorate, James Free from the Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate, and James Reuter from the Space Technology Mission Directorate. During the conversation you'll hear them refer to NASA's CLPS or CLPS program that stands for the Commercial Lunar Payload Services program. With the CLPS initiative, NASA has been competitively funding commercial companies to build spacecraft that autonomously land on the Moon, taking NASA science and technology payloads along with them.

Mat Kaplan: I assume that is for the very distinguished panel that I'm honored to bring out today. To start, to my immediate left, Nicola Nicky Fox of the Science Mission Directorate. Then Jim Free, who is the ESDMD, exploration Systems Development Mission directorate, and Jim Reuter who, there's something special that has to be said here, space technology mission directorate, of course. But what was it, two weeks ago, I think I got the release from NASA that you are ready to retire after over 40 years with the agency rising to associate administrators. So congratulations and thank you Jim. Please.

James Reuter: I do want to say thank you, I really appreciate the sentiment. But what I would say is, I think you said I was ready to retire, a more accurate way to say it is probably that I've decided to retire. We'll determine whether I'm ready.

Mat Kaplan: It's coming. Coming soon. And we may come back to that because I may want to hear about some highlights from you. It's not strictly speaking the title or fit the theme of this particular session, but I have to ask because it's what we're talking about overall. And we're following that panel of experts on, can we get humans to Mars or at least around Mars by 2033? Can we put footprints on Mars by 2040? I'll throw it out to all of you, Nicky?

Nicola Fox: Oh, I think we're certainly very supportive of doing it. We're doing all the pre-work that we can to do it, but I think that would be a bit ambitious. Jim?

James Free: Yeah, I mean you've heard our deputy administrator talk about 2039 mission, and I think when we back that up and connect it with what we're trying to do on the Moon, that is going to be tough. Really, we have to start launching things in probably 2032/2035 to head out to the Moon, to pre-position things for the crew with the current architecture that we would have in place. We also need some time to learn on the Moon in that reduced gravity environment of how our systems work, including our human systems. So it absolutely is aggressive to do that, but that's the timeline that I worry about and getting stuff done in time to meet those launch dates.

James Reuter: And I'd say that is an audacious goal for us to meet. And as Jim said, and what 2039 implies is that you really start the transit there, the logistics train in the early 2030s. So the audaciousness of the 2033 discussion you just had is about when you'd have to start accomplishing that. And for me, we run technologies, so a big part of this is well, do we have the technologies ready for that? And while 2039, that's 17 years or 16 years from now. It may sound like a lot, but it's a very short time in terms of many of the technologies that we need to develop are really need to be going strongly.

Mat Kaplan: You've already brought up something that I wanted to mention and I puzzle over why we still have some people asking why the Moon as a stepping stone to Mars. Why don't we just go straight to Mars? I would think by now anybody who's really looked at this would know, let's get our feet wet or dusty on the Moon before we tackle the red planet. I think I'm right about that?

James Free: I mean I think that's where I was going with we need some time to understand. If I take the ISS analogy, we use the ISS to test, we tested systems for the ISS on the ground and then we launched them and I think the gentleman to my left here had had something to do with it. And we learned that they stopped when they got in microgravity for a variety of reasons, the fluid behavior, whatever it might be, we learned that lesson on ISS of the analog. So we don't want to get to go right to Mars and then have everything gunk up, to use a technical term, and not having tested it on the Moon. But the connectivity for the Moon to Mars is important of the systems, but don't lose sight of what there is to learn scientifically on the Moon. So we're going to go and test our human systems, but our priority is to do the science that we can do on the Moon that's outlined by Nicky and by the Moon Mars objectives as well. So they're connected system wise, but I think don't overlook the science as well.

Mat Kaplan: Jim Free, I'm going to stick with you, but please everybody jump in as you wish. It's only been what, six, seven weeks since I got the press release about the creation of the Moon to Mars program office. Which seems like it very much fits the theme of this session, the collaboration that is going to be absolutely necessary among your directorates and others if we're going to have success in all of this. Can you tell us a little bit about that office and how it represents that collaboration?

James Free: Sure. So we actually have three offices that report to the associate administrator, currently me. One is our strategy and architecture office, which is really tasked with planning the long term missions. So you think Artemis VI and out, they're really focused on that architecture connecting Moon to Mars. And then the Moon to Mars program office is really down and end, think near term missions, Artemis V through Artemis II, but they both have interfaces to these two mission directorates. Both of those offices I talked about. We want to plan that strategy and architecture with technology infusion in mind, with science in mind, and then the Moon to Mars program office, those near term missions. How are we running the technology that's on there and how are we doing the science? But the scope of that office Moon to Mars I think is important because the Mars element of that office is pulling the technologies, it's providing requirements to the lunar missions, to the lunar systems to develop the hardware that we need and keep that connectivity. So we're not developing a life support system that has no connectivity to what we want to use on the surface of Mars or on the way to Mars. So the scope of that office is great for that reason, but it's also very much focused on the near term missions to get it done.

James Reuter: And for us, when Jim formed the Moon to Mars strategy analysis office, it really aligned us well and it gives us a path towards having an understanding that key technology gaps we have to satisfy and which ones the highest priority. Because we can't afford to fund everything, so we've got to be really judicious about what we do and do as much partnerships as we can.

Nicola Fox: And for the science, I think it gives us a really easy interface into the other mission directorate and we obviously we're scientists, we want to do everything everywhere all of the time. And these missions we have, it's a place to really get the requirements ironed out and who's responsible for them and what's actually possible on the various missions. Obviously we're starting early, we're sending our CLPS landers to the Moon, commercial partners, and they'll be starting to launch later this year. We're really excited about that. We're working on that. But we're also looking at what we can do with Artemis II. Obviously we had science on Artemis I, we had the biological and physical science inside the Orion capsule itself. So what are we going to do with Artemis II? And then for me, it's, what's the really exquisite science that we're going to do with astronauts who can actually make decisions right there. Focusing our efforts and giving us a partner to really eye in these things out with.

Mat Kaplan: We got a lot of great science out of Apollo, still getting great science out of Apollo. But there was always that push and pull between, we got to get the astronauts there and back safely and how much science can they do. They were all pretty busy on the Moon. How has that evolved? I got to tell you something that struck me yesterday when we had a SpaceX representative on stage who said that the crew compartment in the Starship lander is about double the size of this stage. And I thought, "Oh, that's room for a lot of science."

Nicola Fox: Yes, that's exactly what I would think too. But there's still going to be that push and pull. Either you have an astronaut safety, you have to get them there safely and back home safely, and that's obviously the prime objective. But making sure that we're using the time while they're there most effectively. If anyone doubts just the real need to bring samples back from whichever destination, looking, we're still doing amazing science with the Apollo samples. And I was out at Johnson a couple of weeks ago and was able to actually tour the labs where they do all the experiments, and you see these just huge mass spectrometers. There's no way you could fly that to the Moon or fly that to Mars. So you bring the samples back and you have your incredible equipment here, but also if you just compare the type of equipment we had even here on Earth 50 years ago with what we have now, you can keep those samples and you can mature your technology and do more and more and more with those samples. We'll still be doing a lot more with Apollo samples for decades to come. And as we bring samples back from Mars, clearly I'm excited about bringing samples back from Mars, there's going to be just decades and decades of work with those Mars samples and more samples from the Moon. First time we're going to the South Pole, they're very different types of samples we'll be bringing back.

Mat Kaplan: No better example than those lunar samples brought back by Apollo of the gifts that keep on giving. It was also just recently the announcement within the solar system Exploration Research Virtual Institute of five more teams that have been selected to do more science on the Moon, once those samples are brought back here. And I know that this is, Jim Free, this is a collaboration between your directorate and Nicky's, it seems like this also represents the collaboration we're seeing within the agency.

James Free: Absolutely. I think it's essential that we maintain that connectivity to science in everything that we do. That's been a funding source, I think that's been around since Bill Gerstenmaier was the AA, because when I was a deputy, I remember that. But I think it's important to enable the science however we can. And at every level, it's not just about for us, it's our big international partners providing elements. It's making science available to everyone. To Nicky's answer to Nicky's last question to add to that, we're going there. We have to establish a human presence to test the systems, but we're doing it to enable science and we enable science through the samples we bring back. Nicky, I know, develops that with the science definition teams that she puts together. It's great inroads at every level for folks that take advantage of that science and what we're able to provide in samples.

Nicola Fox: And I'll also note, our biological and physical sciences division, they're starting out on something called CERISS, which is Commercially Enabled Rapid Space Science. And looking at what they're doing with that right now, obviously we send an experiment up to space, you wait, you get your samples back and then you test it. What they're doing with this is really looking at just accelerating the science. So scientists, astronauts would actually then be preparing samples, doing the testing, making the determination. Do we want to do it differently? And just so we'll be taking years off some of the timescales for the science we can do as well.

James Reuter: I'll add to that too actually, because we're really excited about the survey teams that have been formed because we have a lot of touch points. One of the key things we're trying to do in terms of understanding how we can take advantage of the resources of the Moon and process it, is to really understand what they are and the prospecting things and so on. So I think we have our Lunar Surface Innovation Consortium and I think we'll have strong touch points with the survey as they come forward.

Mat Kaplan: That takes me right to the next question I was hoping to ask, to talk to you about and that's the kinds of things that the most critical steps in terms of preparing to do the science, but also the technologies, the technology demonstrations that the Moon is going to enable for us and Gateway is going to enable for us that we really have to see. I know we're partway there, there's been good progress, but we still have a ways to go before we can get humans to Mars and back safely.

James Free: I would say, I talked about the systems on the surface that we can test and use at Mars, Gateway's incredibly important. We can run analog missions from Mars, analog missions from Gateway, so we can send the crew there, have them spend six months on Gateway in some of our later expeditions out there, like they're flying to Mars for six months and get deconditioned as you do in microgravity. Then send them down to the lunar surface for 30 days, have them operate, test themselves out and then come back to Gateway and stay for six months and then come back to Earth. So we can simulate a Mars mission from microgravity to partial gravity back to microgravity, which will help inform how the human responds. But we'll be doing science all the way through that and we'll need the technologies that Jim and his team are developing to make that happen. Some of the advanced ECLSS from radiation protection as an example of things that really drive our systems. So I think the connection is clearly there for me.

Mat Kaplan: Jim, that's a great example, radiation. You'd be outside the Van Allen belts so it's going to be a lot like a trip to Mars on Gateway.

James Reuter: Yeah, it absolutely is. And there's a lot we'll learn from Mars. Some of the technologies that we have working on is the Gateway, the propulsion elements of the Gateway that the electric thrusters are an advanced size design that we actually have just delivered the qualification unit as part of our development for activity for it. The solar arrays that will power the Gateway is a long time development that we had in technology that has on the rollout solar arrays that are now also the replacement array for [inaudible 00:18:49] use in missions as well as Gateway. When you look at the surface, there's so many things that we're going to be doing there and operating and establishing an infrastructure is one of the key elements that you can do in terms of establishing a base here, a foothold on Moon, and then that activity is understanding how we do that from Mars. Reliable power source, the life support and advanced habitation systems and all these things, we can learn a lot from being on the Moon first.

Mat Kaplan: Whole new technologies that are in development, not only across directorates but across NASA centers. One of my favorite people on earth, Rob Manning, the chief engineer at JPL, loved to talk with him and sit videos of him, of tests of parachutes and aero shells being tested in earth's atmosphere. And then just watching his reaction, which he almost is delighted when they get shredded. But very promising technology, one that some of your staff people have talked about, and I'm thinking of this program, is it LOFTID, am I saying it correctly? Low-Earth Orbit Flight Test of an Inflatable Decelerator.

James Reuter: I'm sure glad you told me what the name was because I could never remember it. Yes, I think we've had it in development a inflatable heat shield to help land through the hypersonic deceleration per missions. When you get missions, you're trying to add extremely large cargo in both in any planet that has an atmosphere, including earth. The big challenge is how do you do that, slow it down. And you need a lot of drag area, one of the best ways to get a drag area is to have it be an inflatable. So back on November 10th, we flew in a public private partnership with Yole, no exchange of funds. They contributed their part, we contributed ours. It's a potential for large return to earth activities and as well as Mars. And for us, we've got to find those kind of partnerships as we go forward. So anyways, we flew onto JPSS-2 mission, we were a ride-share for that. So after the JPSS-2 completed its mission, it was an Atlas V out of Vandenberg, then we were released and we did the demonstration of an inflatable decelerate back to Earth, and it could not have worked better as we went through it. Extremely stable, we saw the inflation was extremely stable. It landed right where it was supposed to just off the coast of Mars. We had a injectable data recorder that we ejected before we got to the ground because that would be something we knew would float and would've a beacon. But we were hoping that we cover the whole system, which we did. It landed within a few miles of where our boat was. When you look at it, the shell itself, the aero shell itself, inflated shell looks almost pristine, like you could just fly it again. The only place that there's there was damage was at the nose cap, the thermal protection system up there had some water damage when it hit.

Mat Kaplan: We also heard a little bit about AeroShield development from a Jacks representative yesterday since they also see great promise in this. Which I should go straight to talking about international collaboration, but before I do, I mentioned the centers collaborating with each other and among the directorates as well. Talk about how critical that is to doing science on Mars and putting footprints up there.

Nicola Fox: It ties to the centers as well as international, but if you look at something as ambitious as Mars sample return, we're doing that with a lot of partners. There's many centers at NASA with JPL, AGARD and Marshall all producing really critical pieces for Mars sample return. But also we have full partnership with the European Space Agency. We are flying some of our NASA hardware on their orbiting system. They're providing a robotic arm on the actual lander that we'll put down that NASA's designing. So it's really critical that we have these really tightly coupled partnerships that the same, we're making contributions to their Rosalind Franklin mission as well. So I think it's in the whole spirit of our exploration and the Artemis Accords moving forward. We just have just innate collaboration, yes between the NASA centers but also out into the world.

Mat Kaplan: Science side, but also I think of maybe the most obvious example of the kind of global collaboration Artemis Accords, but there are even deeper relationships than that. I'm thinking of that ESA service module for Orion, which did a pretty good job not long ago, right?

James Free: Yeah, it absolutely performed, all the vehicles performed well, all elements of the vehicles. The ESA service module absolutely did with a lot of subsystems, propulsion, power, cooling on Artemis II, it'll have all the gases and liquids for the crew. But we build only from there, you talked about Gateway. We have the international Hab that will fly on Gateway, that's part of that, the ESPRIT refueling module that's going to be on there. Jacks is building the ECLSS for the I-Hab module. We're obviously working with other countries, the Japanese on the pressurized rover, the Canadians announced that they have approved for a medium-sized utility rover that we'll be working with. We're flying a Canadian crew member on our first crew. And we have a whole number of partnerships in work as well, on study agreements, talking about how folks can participate big and small. It's not just about the multi-billion dollar elements. The Germans and the Israelis flew the radiation vest on Artemis I, I think you talked about that. So science, collaboration, international science collaboration, great themes, all the CubeSats that we flew that had science on them as well as international. And it really transcends the Accords. So the Accords are great in terms of their thematic about how we're going to operate, how we're going to share data. And then there's how do people participate in the individual missions, sharing science being one of them. We have partners like the Israelis and the Australians who've taken our objectives and given them to their industry and say, "Hey, respond how you can be part of these objectives." So it's building off of their participation in the Accords that now moves over to the programmatic side.

James Reuter: I'll just add, we're also doing a lot of inter-agency collaborations as we go through it. You had a session yesterday, I think here, that talked about the recent agreement we had with DARPA on the DRACO flight demonstrator for a nuclear thermal propulsion system. We're really excited about that and while NASA and DARPA are the major players there, there's also roles outlined for Space Force and DOE it's a multi-agency activity and we're looking for more of those as we go forward.

Mat Kaplan: Industry participation already come up, commercial side has been a pretty notable success in recent years. Can you talk a little bit more about how these relationships have evolved and are also going to help us get out to the red planet?

James Free: For us, obviously we're building off the success of commercial cargo and commercial crew, and those models that have been put in place. We're buying services for our landers, so our first two lander awards were to SpaceX for the first lander for Artemis III and then their more sustainable lander, and we have a competition that will make the announcement here very soon.

Mat Kaplan: Tomorrow. You're among friends care to tip us off?

James Free: It's out there now. So tomorrow for our other lander provider, which is a service, we're buying our space suits as a service as well, which has started off good for us. And then we're looking at things like our lunar train vehicle, our unpressurized rover to buy as a service. Also we had our draft RFP about that, so it's going well. There's challenges, we all see that we need Starship to launch and be successful, to be successful for our first lander. It's a great process. It's a good contract structure in terms of cost savings, but we still need to hit schedule. And that's driving me right now is hitting schedule and buying services no matter what we're getting. But those are the three I'd highlight as our prime examples.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll be right back after this short break.

LeVar Burton: Hi you all, LeVar Burton here. Through my roles on Star Trek and Reading Rainbow, I have seen generations of curious minds inspired by the strange new worlds explored in books and on television. I know how important it is to encourage that curiosity in a young explorer's life and that's why I'm excited to share with you a new program from my friends at the Planetary Society. It's called the Planetary Academy and anyone can join. Designed for ages five through nine by Bill Nye and the curriculum experts at the Planetary Society, the Planetary Academy is a special membership subscription for kids and families who love space. Members get quarterly mail packages that take them on learning adventures through the many worlds of our solar system and beyond. Each package includes images and factoids, hands-on activities, experiments and games and special surprises. A lifelong passion for space, science and discovery starts when we're young. Give the gift of the cosmos to the explorer in your life.

Mat Kaplan: Nicky, you started to address this with commercial participation in science activities. Expand on that.

Nicola Fox: So we have a couple, so one is obviously the CLPS, the Commercial Luna Payload that we're sending to the Moon. So we've actually been touring and visiting some of our providers, the industry partners who are actually providing the landers. It's really cool to actually see the lander and see the science on the side of it, but really looking forward to getting those up to schedule to go this year. Many more to schedule to go after that. Going to very challenging areas, things like landing, landing at the South Pole, landing in total shadow and having to survive the night. They're some pretty exciting things. One that will be, these are sort of the tech demos that Jim might talk more about, but one that's actually going to hop, so it'll land and then it'll hop into the shadow and then the plan is anyway, it'll hop back out again. But they're just really, really cool things that we're doing and we're taking advantage of maturing these commercial capabilities, but putting science on them wherever we go. Also, as we transition from the ISS to commercial LEO destinations, starting to plan what can we do with these new facilities and I mentioned CERISS as one example of actually being able to do science on the spot, as opposed to having to take years. But even looking at what we can do with biological and physical sciences, can we put some of those experiments on CubeSats and launch them, as Jim said, launch them with Artemis or launch them with one of our other commercial providers. Instead of always waiting for an opportunity on ISS, can we take advantage of some of these other commercial partnerships just to get more science into space? That's my goal, is more science into space, so taking advantage of every single piece of the Moon to Mars initiative. So starting with the ISS, commercial lunar destination, flying stuff in Orion, putting experiments on the Gateway. We have external payloads on the Gateway, looking at what kind of science can be done inside the Gateway. Then we've got CLPS going to the lunar surface, then we've got astronauts going to the lunar surface, we've got Mars sample return. We're taking advantage of every single opportunity to do science.

Mat Kaplan: I can't wait for those spacecraft to reach the South Pole and start digging down to that wet stuff, that's going to be so cool.

James Reuter: Absolutely, we're excited for it too. What I'll say is, we're increasingly pushing for partnerships in the investments we make, which isn't always intuitive when you're working with technology developments sometimes at a very low technology readiness level. But this is an exciting time to be working in space with all the in interest in investments as we go forward. And Nicky alluded to it, we have a tipping point and some announcement of collaborative opportunities or ACO type solicitations that we do about every other year and we've just recently announced our ACOs and we're about ready to announce our tipping point selections. But these are very, oftentimes, key technology developments that we would demonstrate as part of it on the Moon. An example of that is the intuitive machine second mission, as we go through it is actually pretty much almost all a technology mission, and Nicky alluded to hopper that goes at a mile at a time or something around the surface, hops into a permanent shadow region and can hop out and stuff. With that we are demonstrating a 4G LTE network, a wireless network on the Moon, and we also have the first demonstration of a drill looking for ice water. And so we go through it. That same drill or a second copy of that drill is going to fly on the VIPER mission that Nicky leads. And we have all kinds of places like that in [inaudible 00:32:27] interspace as well, we flew the CAPSTONE mission as a way to get to the NRHO orbit early. And we had a goal a couple years ago of, let's come up with a way to fly a CubeSat in the NRHO orbit that Gateway does and do that in enough time that it can help influence things. And it's now spent 120 or so days on the Moon in the orbit and stuff, it's working extremely well now. And it's in actually the experiment phase of autonomous navigation that you're going through it. So we have lots of examples and they're very strong examples of the industry, academia and the government working together.

James Free: Probably know we're kind of partial to CubeSats at my organization.

Nicola Fox: But I actually think that the tech demos that we're doing with CLPS, I know I'm supposed to get excited about the science, but the tech demos are really cool and there's something on every single one. We have the advanced solar arrays and then the precision landing, which is going to be so cool. So things like doing the precision landing with a CLPS land that is going to immediately help and inform as we do things moving forward.

James Reuter: I'll just add one more that's a nice example like that, is the Terrain Relative Navigation system that we flew on Mars Perseverance to land accurately in the Jezero crater. What we've done since then is we developed it for that in concert with science, and then what we've done since then is developed a commercialized product or the industry has developed a commercialized product that we've helped them with. And so that technology is now flying on some of these CLPS lands.

Nicola Fox: We've got partnerships with everybody, it's commercial, it's academia, it's industry. It's going to take those kind of partnerships and those kind of relationships to do these big hairy, audacious goals that we want to do. I think honestly, it'll be hard to think of an example that doesn't include a really, really important critical partnership in every aspect.

James Free: And I'd highlight the architecture that we just rolled out a couple weeks ago, we have the Moon to Mars objectives, those 63 objectives that were developed by the entire agency, developed by the mission directorates. We have the document that explains those that came out just a week or so before the architecture, talks about the meaning behind each one. Then we have our architecture definition document, which is, we and ESDMD have the responsibility to shepherd through, but it's developed with all the mission directorates. And then the specific elements that come out of that architecture are collaborations between all of us. So from the strategy at the objectives level to the implementation, I said publicly several times, I'm so proud of the fact that we can connect our strategy to requirements. There's not a lot of companies that can do that, let alone a government agency. And is it perfect the first time out? Probably not, but this is a yearly process we're going to go through and we go through it as a group, all the mission directorates together and the centers by the way, to your earlier point.

Nicola Fox: And even just the cross pollination between the various tracks that we had. So there's a science track, there's a sustainability, there's the transportation, and we were all dropping into one another's, all the way through, to just make sure that, again, you're taking advantage of it or you understand what the other ones are doing. And so that was just seamless even as we were putting the architecture together.

James Reuter: And we did it ourselves, we've been developing over the last few years is our way to help guide our investment strategy and we call it our Strategic Technology Framework that we developed. And with that we were developing objectives in parallel basically to the activity of the Moon to Mars and it mapped extremely well. We were able to do that really well. So now naturally there's some things, Moon to Mars objectives are broader than just technology items, much broader, but also our scope is more than just Moon to Mars, it's supporting other science missions and multiple other places. So it's not a complete one-to-one, but everything that we have it maps really well. And then with the Moon to Mars objectives and the follow on technology gaps, then we can feed that into our investments strategies going forward.

Mat Kaplan: You don't quite go far enough back to be able to say, you were there for Apollo when it was pretty much, we're going alone at NASA, if you ignore some rather large cost plus contracts. Can you even imagine today taking on the goals, the objectives that are currently in place at NASA without doing the sorts of collaborations that you've been describing, Nicky?

Nicola Fox: No, I really can't. We certainly go together as we return to the Moon and I think that's a really important thing that we're doing. It's also really great, it's great to be collaborating and actually having a lot of the new partners, people that are new to space, and that's actually, that's something we've been helping in the science mission director. It is finding new ways for some emerging partners to come in and do something meaningful and grow their space capabilities too. No, I can't imagine it and I don't want to imagine it either.

Mat Kaplan: Jim Free.

James Free: I can't imagine it at all. And we just had Space Symposium where we met with all of our international partners, because everybody's there so it's a great chance to meet with everybody. I have the privilege of really going around the world, working with all of our international partners on their future plans, seeing their excitement. If I just look at the excitement of having a Canadian astronaut on the crew, by the way, the crew is in D.C. today and tomorrow-

Mat Kaplan: And what a great guy, Jeremy Hansen.

James Free: Yeah, fantastic. But you see the enthusiasm that the entire crew brings, but one astronaut from that country, it shows you the excitement that it brings and the really commitment and not around the world to work together. So I can't even imagine it, nor could I imagine trying to afford it all ourselves either. There's a practical nature to this, but it is truly about going together for all humanity this time.

James Reuter: This is the only way we could do it. We would not succeed if it wasn't together.

Mat Kaplan: My boss, the science guy, Bill Nye says a lot of cool things, but one of the things she says is that space brings us together and brings out the best in us. And this seems to be a great example of what that's capable of. Let's go out to you folks. Hi.

Eric Anson: Hi. Eric Anson, Baylor College of Medicine. Thank you very much for this talk. It's been fascinating. One of the things if you've been watching NASA for the last few years is there's a significant shift towards commercial services contracts in the way that you've handled your business. Can you talk a little bit about the benefits of that and also some of the challenges that you've found? I think, I believe CLPS is a commercial services contract now and it seems to be a changing business model over the last decade.

Nicola Fox: Yeah. I mean CLPS is a great example. It's certainly enabling, it's enabling us to get more science onto the Moon, it's enabling technology developments. There are challenges, for sure, it's the first time we're really doing these things. Certainly my predecessor, Thomas said, "We don't expect all of them to succeed. We're willing to reach out and if some don't work, they don't work, but it's part of doing business." Certainly we want them all to succeed and this is landing on the Moon, it's not easy. So there were definitely challenges, even practices and best practices and different ways of that we would normally do missions and the challenge of even integrating science. But there's certainly challenges, but I'm hoping it's going to be worth it when that first CLPS lander touches down on the Moon.

Mat Kaplan: Gentlemen?

James Free: Just highlight maybe a little bit more what I said earlier, the commercial cargo and commercial crew, I look at what that has enabled to bring launches back to the U.S. It obviously enables a lot for us on Space Station, but brought that back to the U.S. The three I mentioned, suits, landers and LTV, those are markets that don't exist today and we're buying services in them. So we're trying to enable services so that it enables other things, perhaps on the lunar surface elsewhere in space. But on the lunar surface, our ultimate goal is to not be the only one there and seeing commercial on the surface. So we're hoping that the trend of commercial cargo and crew and now with what we're trying to do enables things further.

James Reuter: And I'll just add, I think that whenever you create an environment that encourages innovation in order to get ahead and in the process being competitive as it brings out the best almost all the time.

Mat Kaplan: Hi sir.

Bruce Jakosky: Hi, Bruce Jakosky, University of Colorado.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, it's Bruce. Hi Bruce.

Bruce Jakosky: Let me follow up with a question to Nicky on the CLPS comments. Can you envision a scenario where a Mars equivalent commercial type of partnership might work?

Mat Kaplan: And you want to say anything about the MAVEN mission while we're at it?

Bruce Jakosky: Go MAVEN.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, go MAVEN.

Nicola Fox: Yes, MAVEN is going strong. We haven't planned for that, I think we'll probably see how the model works on the Moon. I'm taking a leaf out of Jim's comments of, we hone things on the Moon and then we move them to Mars. I think we'll have to see how successful it is at the Moon, but I certainly could envisage doing that type of thing and seeing how we can put more infrastructure on Mars. Getting back to what both of my colleagues said about, if we're going to do humans to Mars in a 17 years, we'd have to be really starting to think about the infrastructure that we'd have to have in place for them at Mars. But it's certainly something to consider. But I do want to see how well we do at the Moon first.

Mat Kaplan: And for those of you who aren't familiar with it, MAVEN, helping us to understand where all that air went on Mars that once upon a time had Mars much more looking like Earth than it does now. There is one other kind of collaboration, which I'm going to go back to that announcement from the institute that you collaborate on, and it's the collaboration between humans and robots. And asking you how essential is that going to be as the humans are right there with the robots helping to get the work done?

James Free: I mentioned the Canadian utility rover, that's an example where that will work autonomously when the crew's not there but can follow the crew along. The crew can only carry so much with them when they leave the habitat or the lander or the LTV. We can have the robots going with them to carry things with them or carry them back. We want to take some of the samples and keep them at cryogenic, I'll say cold temperatures, cryogenics going to be a whole new reach. But we want to keep them cold so that we can preserve as many of the volatiles that we can in the sample. And getting them back in a condition that we can use them as we go through all the chain of custody as we're starting to talk about it, that starts on the Moon and we can have them work closely with the astronauts. We can have robots scout and the astronauts control them, much like you see soldiers controlling drones today, we can help them explore without taking risks perhaps down into a permanently shadowed crater. So to me it's both a safety and a science return that benefits those two working together.

James Reuter: And I'll say Moon is an obvious place, because the crew will come in and out, people will come in and out, but there'll be activities that we want to extend too. But Mars actually, if you think about it, almost any scenario getting to Mars prepositions a lot of supplies and logistics or creates fuel, and all that would have to be done robotically before the crew is there.

Krystal Puga: Hi, Krystal Puga, mission architect with Northrop Grumman. So I think we all agree that the Moon is laying the foundation for getting us to Mars and there's a component of the Moon where we're continuing to evolve, we can continue to do more science, we can grow our habitat, add modules. But at what point does continuing to evolve and learn on the Moon become a detriment to getting us to Mars? Or do you think that we can handle to run both in parallel?

James Free: I defer to the scientists for the science side of things, but from a practical aspect, we want to set it up so that the work on the Moon continues. And if again, I go to the ISS and the commercial LEO destination model, we'd love to see that model happen on the Moon. Where we're obviously a strong upfront investor, and I say we with all our international community, and we'd love to see that continue on with others doing things on the Moon that they like to do but we can still benefit from. And maybe we're not flying an entire vehicle there like we will be for the foreseeable future, but we can buy services, we can send our crews there and live in someone else's habitat or go somewhere else on the surface, so that we can afford go onto Mars off of the Moon. So I think it's this balance of everybody wants to say, "When do we stop at the Moon?" The answer is, we don't stop at the Moon. We continue working on the Moon and doing science on the Moon while we go onto Mars. We're just hopeful that the business model changes like we're trying to do in ISS and commercial LEO destinations today.

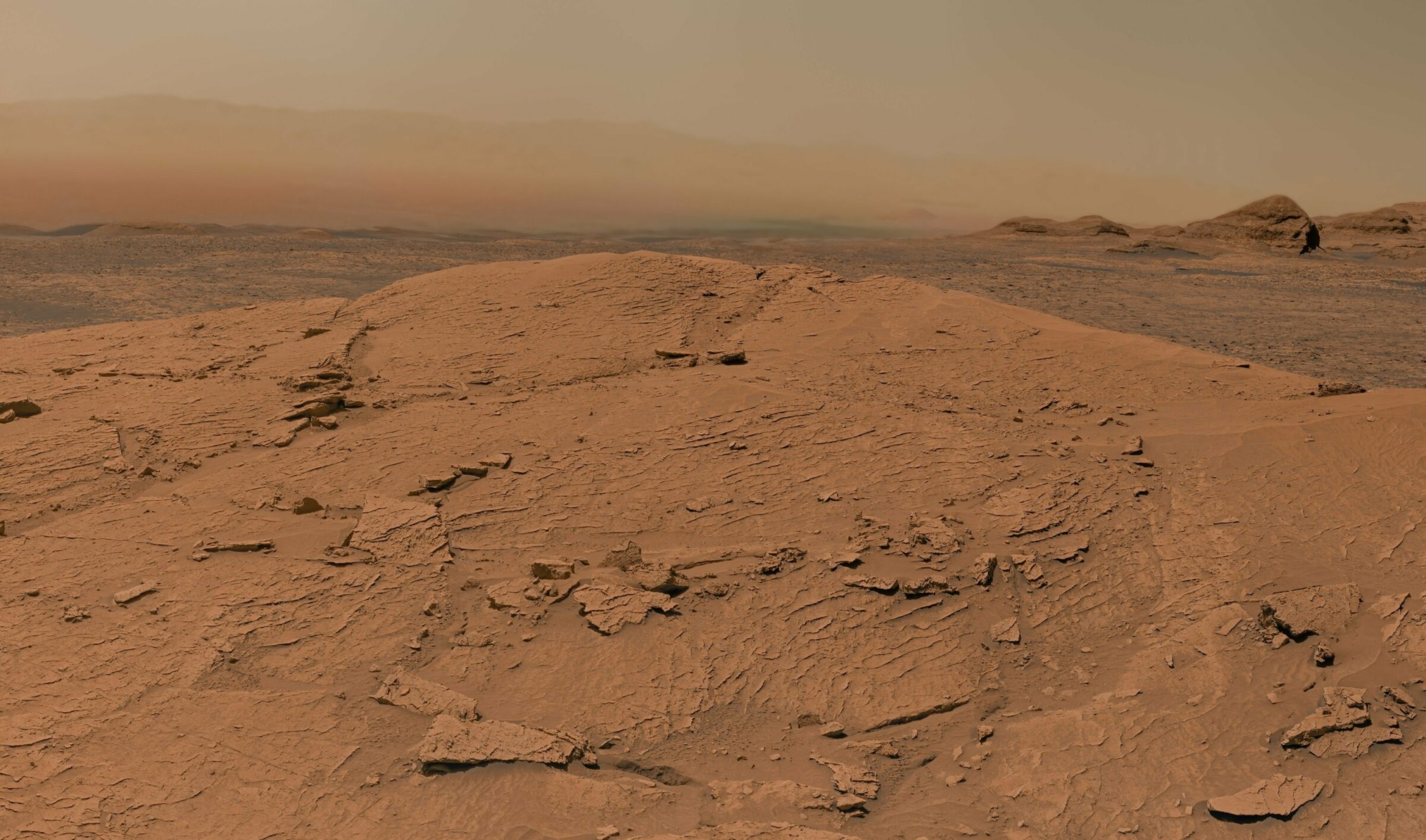

Nicola Fox: From a science point of view, there's always going to be science to do on the Moon. You think of any destination you go to, there's always... You get more questions than you get answers with every single thing you do. And we've got really strong, obviously lunar science we want to do, but there's also astrophysics we can do from the Moon, there's heliophysics, learning about the ancient sun. There's so much to do and so many places to explore that I certainly don't think from a science perspective it will hold us up. And we're already doing amazing science on Mars, which actually, if anything wants me to accelerate being able to do more. I'm sure you will saw the Perseverance results earlier, can't remember if it was earlier this week or last week, with taking the rock sample that's clearly been washed down from a different region, showing that we've had flowing water on Mars. And that just makes me absolutely desperate to go to Mars right now actually and go and find out what's going on. But I think from a science point of view, whatever we study, we get more questions than answers every time we do it.

James Reuter: I think that a key question that the Moon to Mars objectives try to answer is, it's not Moon or Mars, it's Moon and Mars.

Nicola Fox: Correct.

James Reuter: And so for us, a key part is to create a environment, as Jim talked about, that's a sustainable presence on the Moon. The sustainable presence does not mean NASA going once or twice a year, it's that we're enabling the entire community across the world to be able to go and you can take advantage of that.

Mat Kaplan: You going to get a big radio telescope someday on far side?

Nicola Fox: I'm sure somebody's going to propose one.

Mat Kaplan: I know I NIAC, there seem to be three or four every year proposals for building those things out in radio silence. We've only got a couple of minutes left and I don't see anybody at the microphone. So Jim Reuter, I'm going to come back to you as I said I would. Looking back over your more than four decades, highlights, things you're most proud of and what are you most looking forward to as you watch what happens after your exit?

James Reuter: Yeah. Well first thing I'll say is Robert Lightfoot, when he retired from NASA, said he was going to run through the tape. I'm going to run through the tape, so my focus is really on executing my job over the next month and a half or so. I've been at NASA, my 40-year anniversary was just a couple weeks ago, and that means I've been at NASA for a little over 60% of NASA's existence. When I came to NASA, we had just flown the sixth shuttle mission out of the 135, and that sixth one was the first shuttle mission that was after Columbia, I think it was challenger as we go through it. So I had the privilege of working a lot of places around the agency, mostly in human space flight. During those early formative years, it was working payload integration on shuttle. I was part of the International Space Station from the start to the time we went permanently occupied and running the life support systems as we went through that. After Columbia, I was brought in a leadership position to help figure out how to keep the water a tank. And then over the last eight years I've had the extreme privilege of being working in space technology with the last five years leading it. So I just can't say enough how lucky I am on the best place to work. But what I'd say in terms of exciting me, I don't know that there's ever been a more exciting time in space than now. FY22 was an incredible year for NASA and for the world, but just the breadth of the types of things we're doing, the interest in engagement of industry and academia, other partner, other international agencies and internationals themselves, we've never had that before and it's one of the most exciting things I think that we do is working it together. It always boils down to the people you work with.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you for your service. I look to the other members of the panel, Jim Free, Nicky, if you have any closing thoughts, now's the time.

Nicola Fox: I think Jim's absolutely right, there's such an energy and such an excitement through the whole community, I think, certainly at the agency. I used the term, just before we were coming out, I feel like we're standing in the time before. We're going to remember this as the time before everything just really happened. And so it's an incredibly exciting time to be at the agency and to be a leading science.

Mat Kaplan: Jim Free you got the last word.

James Free: Yeah, well it's hard to top those two. I said before we came out here that I had some revelation over the weekend, that we're doing what Apollo was asked to do, to take humans to the Moon, and we can get caught up in the budget fights or what's this or what's that, but ultimately that's what we've been asked to do. And that is an extreme privilege for me and an extreme opportunity frankly for all of us to change history forever.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, all three of you. Keep it up and onward to the Moon and Mars. And please one more round of applause for our three associate administrators.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I've yet to go to the Humans to Mars Summit myself, but it's definitely on my bucket list. And whether or not we can send humans to Mars by the 2030s, the fact that it's within reach is beautiful. There were a lot of wonderful panels and conversations at the Humans to Mars Summit this year. And events from all three days of the conference are available to watch online for free. You can learn more about the Humans to Mars Summit and our friends at Explore Mars at their website at exploremars.org. All right, now let's check in with Bruce Betts, the chief scientist of the Planetary Society, for What's Up. Hi Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hi Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: How's it going?

Bruce Betts: Hunky-dory, spiffy, keen, swell and you?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Or should I say, what's up?

Bruce Betts: Planets, stars, stuff. But all right, we'll just get right into it. Venus still over there hanging out in the west after sunset, looking super, super bright. If you look above Venus, you'll see the much dimmer Mars, and Mars will be hanging out with a similarly bright, slightly brighter star, Regulus, the brightest star in Leo. I'll be particularly close to it on the night of July 10th, so that's fun. And then the Moon in the predawn east on July 11th, the Moon will be next to bright Jupiter. So Jupiter is in the predawn east looking very bright. Saturn's running away off into the west, so you can see it high in the sky by dawn, it's actually rising in the middle of the night. You might be able to catch maybe Mercury, but there's a lot of other good stuff. On the night of July 20th, we've got the Moon near Mars. So Mars looking dimish, they're off in the west all the time. But the crescent Moon joins Mars on July 20th and that's what's up.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I usually keep listener comments for later, but we actually had someone write in this week to say thank you to you Bruce. Laura Dodd from Eureka, California wrote in to say that because of your what's up segment and what wasn't going on in the sky, that she was able to keep her friends looking for Mars to appear in the dusk sky on the solstice specifically because of what's up. And that it made a really pretty triangle with Venus and the Moon.

Bruce Betts: Oh, cool. Excellent, excellent. Wonderful. Always good to hear stuff like that. And speaking of good stuff, we'll go on to this week in space history, 1979, Voyager 2 flew past Jupiter, and we grabbed a bunch more cool imagery and data about the big planet that's big old moons and little ones. And then 20 years ago, 20 years ago the Mars Rover Opportunity launched, headed off to do its thing at Mars and find all sorts great stuff.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know it was 20 years ago, but it doesn't feel like 20 years ago.

Bruce Betts: Yes, I know this feeling. I know it well. On to random space fact.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Do you need a cough drop?

Bruce Betts: Yeah, probably. No, I'm good. Good. Just wanted to share that lunar material returned by the Apollo astronauts probably no 382 kilograms or 842 pounds of lunar material brought back in 2200 individual specimens, which have been processed into more than 110,000 individually cataloged samples, hanging out and distributed by the curators at Johnson Space Center.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's a lot of samples.

Bruce Betts: Let us move on to the trivia contest. Why I asked you what is the closest nebula to Earth, how'd we do and did people agree?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: People agreed on this one, although they had all kinds of fun names for it. One person, Julie Kelly from Copperas Cove, Texas called it the creepy eyeball nebula.

Bruce Betts: Ah, yes. It's original name.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Looks like the Eye of Sauron or something, but it's the Helix Nebula.

Bruce Betts: Indeed.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Which when we say it's the closest one to Earth, close is relative, but in space we're talking about an object that's about 700 light years away. So it's actually quite distant but close when you think about the universe.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, it's all relative, but relative to us it's really far away.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Really far away.

Bruce Betts: Relative to the size of the galaxy, pretty darn close. Size of the universe, practically touching it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's funny too, because it's hard for me to remember because I was so young, but I'm pretty sure the Helix Nebula was the first thing I ever looked at through a telescope. Because I remember running back to my mom and calling it the space Cheerio. Considering that it's probably closer than the Ring Nebula or something, it's probably the thing I saw. But our winner this week is Darcio Cordera from Taubaté, Brazil. I haven't gotten to give anything to someone in Brazil yet, so I love this. Your prize Darcio is a collection of orally NASA, JWST, nail polishes and nail stickers. So if you don't personally use nail polish, highly recommend giving these as a gift to someone. I'm giving them to a bunch of my friends, because who doesn't love putting the Carina Nebula on everything?

Bruce Betts: Huh? Yeah. Okay. Yeah, that makes sense.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And I'm sure people are wondering this in their brains because last episode we announced that we were going to be moving the space trivia contest from What's Up into our member community. And since then I've gotten some questions from people asking how they can send in their questions and comments, so we can continue to share them on the show. And don't worry everyone, we've got you. So you can send us any of your cool stories or comments or questions for Bruce, if you've got cool space questions, you can email them to us at [email protected]. And to make it easier, on our website for each planetary radio page where we usually have the section that links to our contest page, we're going to be linking to this email. So it'll still be just as easy for you to send us all your comments, because I love reading them. I love all the poetry and the messages that people send us, it's part of the highlight of my week getting to read people's messages.

Bruce Betts: It's good stuff.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. Oh, this was so cool because months ago, I want to say it was May, we had a space trivia contest winner named Aquiel Gado. And at the time we had a conversation about whether or not the name Aquiel came from that Star Trek, the next generation episode called Aquiel. And she actually wrote in this week to answer the question. The answer is yes, she was named for that episode of Star Trek. I wish my name had such a cool origin. What about you, are you secretly named for Bruce Wayne or something?

Bruce Betts: There was thought of renaming me, the Gorn, it's a original series obscurity.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So what's our next trivia contest question, Bruce? We only have two questions left.

Bruce Betts: Oh, it's a good one? Who is the oldest person to have flown in space? Suborbital is okay, half past the von Kármán line at a hundred kilometers. And to be really specific, who is at the oldest age when they flew in space? Not necessarily who's oldest now. Anyway, who's the oldest person to have flown in space? Go to planetary.org/radiocontest.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And you have until Wednesday, July 12th at 8:00 AM Pacific Time to get us your answer. And since we're down to the last two space trivia contest questions on the show before we move it into the community, I'm giving away some giant prizes. I'm not going to go through the whole list, but I'm throwing in stickers and patches and posters and all kinds of cool stuff that I have on my desk just waiting to be prizes. But the thing that everyone's going to be happiest about, I think, is that we track down a few extra rubber asteroids. So our next two winners will receive some of the last squishy stress ball asteroids we have.

Bruce Betts: Awesome. Excellent for demonstrating asteroid impact.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It makes me feel a little, better because I have one on my desk that I'm unwilling to give away. And for a moment there I was considering giving it away as one of the last trivia contest prizes, but now I get to keep it.

Bruce Betts: Now you don't have to, that's nice. All right, everybody go out there, look on the night sky and think about dental floss. Thank you and goodnight.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with even more space, science and exploration. Planetary Radio is produced by the Planetary Society in Pasadena, California and is made possible by our dedicated members. You can join us as we work together to explore the Red Planet and others at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. And until next week, ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth