Planetary Radio • Jan 18, 2023

Martian Mic Drop

On This Episode

Jason Achilles

Musician, Investigator for NASA’s Perseverance Rover’s EDLCam microphone, President of Zandef Deksit Inc.

Rae Paoletta

Director of Content & Engagement for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

Jason Achilles, a musician who partnered with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to help put one of the first microphones on Mars, shares his journey and the joy of listening to the sounds of Mars. We also highlight an upcoming opportunity to view comet 2022 E3 (ZTF). Stick around for more on the night sky and our space trivia contest with What’s Up.

Related Links

- Jason Achilles website

- Mars Microphones

- How to see Comet 2022 E3 (ZTF)

- Carl Sagan's Message to Mars

- The night sky

- The Downlink

- Subscribe to the monthly Planetary Radio newsletter

Trivia Contest

This Week’s Question:

Whose voice was the first to be broadcast from space?

This Week’s Prize:

A 2023 International Space Station calendar

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, January 25 at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

Where in the Solar System is Doom Mons, named after Mount Doom in the Lord of the Rings?

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the January 4, 2023 space trivia contest:

What planetary system was the setting for the majority of the original Doom video game?

Answer:

The Doom video game took place in the Mars system, primarily on the moon Phobos.

Transcript

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Listening to the sounds of Mars, this week on Planetary Radio. I'm Sarah Al-Ahmed of The Planetary Society. With more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond, have you heard the recordings from the Red Planet? After decades of effort to put a microphone on Mars, we can finally listen to the sound of the Martian wind thanks to NASA's Perseverance rover and the teams who work to make its two microphones a reality. In a moment, you'll hear my interview with Jason Achilles, a musician with a passion for space, who used his audio prowess to help put one of the first successful microphones on Mars. We'll also share a rare upcoming opportunity to view a comet that hasn't swung by earth in over 50,000 years. Stick around for what's up with Bruce Betts and this week's Space Trivia Contest. In SpaceNews, Virgin Orbit's first launch from the UK hit a major snag after it lifted off from Spaceport Cornwall on January 9th. Virgin Orbit, not to be confused with its sister company, Virgin Galactic, is a company that provides launch services for small satellites. Their LauncherOne rocket suffered an anomaly sometime after it was released from its carrier plane. It was supposed to deploy nine satellites, but sadly, none of them made it into orbit. We aren't yet sure what caused the anomaly, but hopefully, we'll know more soon. Meanwhile, in the United States, Representative Frank Lucas has been named chair to the US House Science Space and Technology Committee. Lucas, a Republican from Oklahoma, has served as ranking member of the science committee since 2019. You can learn more about these stories and glimpse a beautiful image of frost around a crater on Mars, captured by the European Space Agency's Mars Express Orbiter in the January 13th edition of our weekly newsletter, The Downlink. Read it or subscribe to have it sent to your inbox for free every Friday at planetary.org/downlink. The coming weeks hold a special treat for anyone with their eyes on the skies. A comet from the outer solar system will be passing close to earth for the first time in 50,000 years this month, and you might be able to see it. Rae Paoletta, associate producer for the show and Director of Content and Engagement at The Planetary Society joins us next with the icy details. Hi Rae, welcome back on Planetary Radio.

Rae Paoletta: Thanks so much. It's always great to be here. I am thrilled to be here chatting about the night sky.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, and I hear there's like an exciting opportunity to see a new naked eye comic coming our way, right?

Rae Paoletta: Yeah, this one's going to be really interesting. So, the comet is called Comet 2022 E3 with ZTF in parentheses, because it was found at the Zwicky Observatory, I believe. We're still working on that name. It's a really interesting comet. It's taken 50,000 years to get this close again to Earth. It's fast-approaching. The last time we were able to see it, and I say we as in the human race, was actually during the Stone Age, I believe. So, this should be really cool.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's always really interesting to think about what was happening the last time that a comet swung by Earth and that context is really interesting because now I'm just envisioning early humans staring up at the sky and I'm sure being very weirded out.

Rae Paoletta: Right? Did we have tools at that time? I mean, I suppose we did, right? We were making some pretty rudimentary tools, but it's wild to think how much has changed from the last time that this comet approached Earth in close enough fashion that you could see it with the naked eye, but this time around, probably best to use binoculars if you can. I know that I'll be doing my best to take a grainy terrible iPhone picture, which is my astronomy fashion is to take horrible iPhone pictures of the moon. You can check it out online, and I'm really excited to see this. This time around though, if you're interested in seeing the comet, it will probably appear at the closest, if you're in the Northern Hemisphere, around February 1st. The closest it's going to come is about 42 million kilometers, so that's roughly 26 million miles, and if you're in a spot where it's low light pollution, great, always easier to see. Of course, with comet brightness though, it's always a little bit difficult to tell how bright it's going to be. We don't think it's going to be necessarily the same kind of pronounced tail that we saw in NEOWISE back in 2020. It'll be more of like a greenish smudge as my colleague Kate Howells wrote in the article about it. So, it'll still be really cool, nonetheless, just setting expectations.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And I'll make sure to share the article on our Planetary Radio page for this week. So, if anybody wants to read the article and find out more about how you can see this comet, you can find that at planetary.org/radio. I was going to ask Rae, have you ever seen a comet before?

Rae Paoletta: You know what? I don't actually think I have, which is so embarrassing and horrible for me to... As a space editor, I don't think I've seen one.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: No, that just means this is your chance. The only one I got to see really clearly was when I was a child, I saw Hale-Bopp and it blew my mind. I don't know if it was actually as spectacular as I remember it, but my little kid brain remembers it being so huge and amazing. So, anytime I can encourage people to go out and check a comet, I'm so happy.

Rae Paoletta: Oh yeah. Totally. No, this is my chance. I'll be looking up for sure.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks for sharing that with us, Rae, and hopefully, I'll have you back on Planetary Radio soon.

Rae Paoletta: Absolutely. Take care. Thanks.

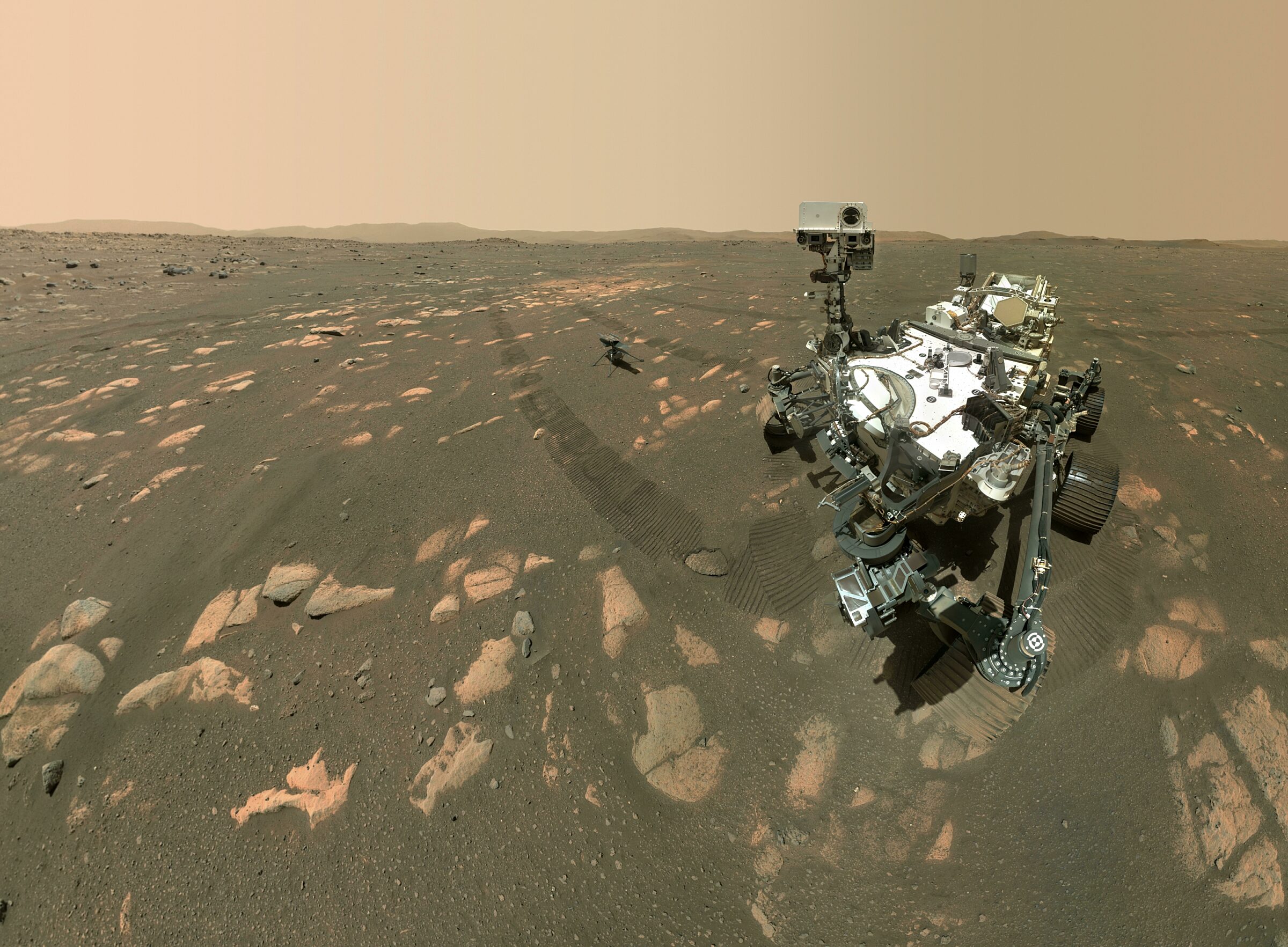

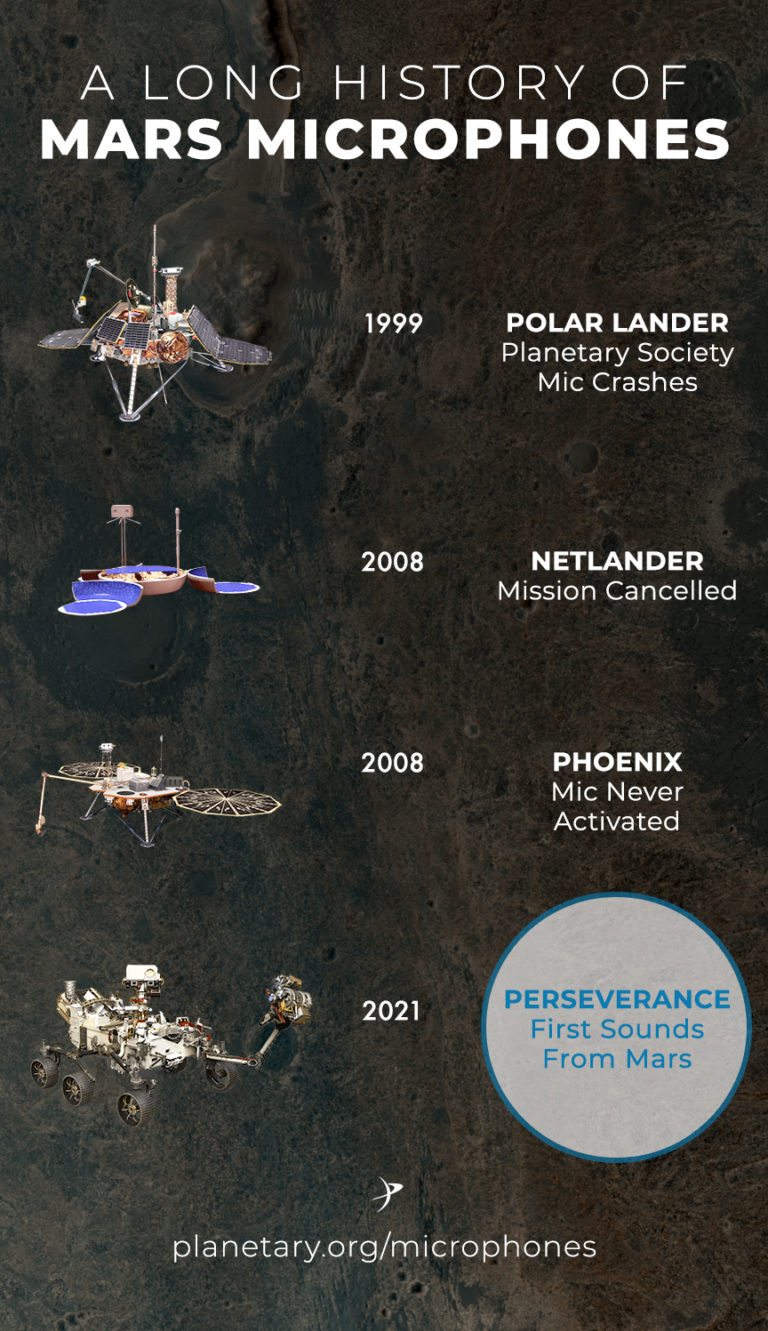

Sarah Al-Ahmed: In 1996, Planetary Society co-founder Carl Sagan wrote a letter to NASA, urging the agency to include a microphone on their next Mars mission. It began a 25-year-long campaign here at The Planetary Society to try to get a microphone on Mars. There were several attempts to make it happen over the years, but it wasn't until the triumphant moment that NASA's Perseverance rover touchdown on the Red Planet in 2021 that the dream finally became a reality. Perseverance included not one, but two microphones on board, the SuperCam mic, which records the rover's lasers apps on the Martian rocks among other things, and the entry, descent and landing or EDL microphone, which was meant to capture audio from the rover's landing along with other sounds. Unfortunately, the EDL microphone didn't successfully record the landing noises, but the two mics have returned a wealth of Martian and rover noises to earth. My guest this week is Jason Achilles, a self-proclaimed extraterrestrial audio engineer and president of Zandef Deksit Incorporated. He's a composer, producer and musician whose passion for space led him on a mission to partner with NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California to make the EDL Mars microphone a reality. Thanks for joining me, Jason.

Jason Achilles: I'm very happy to be here.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, it's really cool to get to talk to you again because the last time I saw you in the real world, it was actually at Astronomy On Tap in Pasadena, and you were rocking out on a guitar and it was right after a really long day for me. It was the 240th American Astronomical Society. So, to cap off that adventure, it was really cool to just chill out and watch you play your guitar.

Jason Achilles: Yeah, I guess to explain to people, Caltech holds an astronomy lecture every month in Pasadena. My band plays in between the speakers and it's a very cool experience and it was great that you came.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And I was very struck by your music style. You call it what? Cosmic rock, right?

Jason Achilles: Other people call it that, and then they ask me and I'm like, "I don't know. That sounds as good." Yeah, cosmic space rock or something. It's all instrumental. It's definitely got some atmospheric Pink Floyd kind of qualities, and then there's more upbeat, I don't know, Jeff Beck meets Stevie Wonder-ish kind of... I don't know. As long as people like it and buy the t-shirts, I'm happy.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, I definitely enjoyed it. I kept thinking, "I need to pick up that guitar and learn more."

Jason Achilles: Well, take some financial planning classes if you want to be a musician. That's what I tell everybody. Playing your instrument is nearly as important as knowing how to afford to keep doing it.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But you've managed to not just play music, but find a way to apply what you learned from your musical career to something that you're very passionate about, which is space exploration and that's part of why I wanted to talk to you because ever since I learned that I was going to be the new host of Planetary Radio, I've been making these schemes to talk to you about this because I feel like that's so relatable and inspiring that you went from rockstar to this Mars microphone program. How did that happen?

Jason Achilles: Yeah, well, I tell people I basically have started an aerospace career just to pay for the music one, which is honestly how it's been working out lately. It's been going pretty well. Basically, I cold-called NASA in the middle of... I think it was summer of 2016, something like that, and I'd heard that there was going to be a microphone flowing a couple months, and I thought, well, if I'm ever going to get into the space world, this is actually something I know something about, which is audio, and I had a cursory working knowledge of rover systems and things like that just from being a fan of that stuff. So, I pitched myself as an audio consultant and said like, "Hey, if you guys need anybody, I'm in," and it turned out they actually did. They had recently specked out they were going to have a mic as part of the EDL system, the entry, descent, and landing system, which is separate from SuperCam, which is a microphone that at least at the time of this recording just released some more audio, but there's two different microphones on Perseverance. So, then I had to put together a team of engineers to basically do the more technically specific aspects of that study that I didn't know how to do. I understood enough about what I'd seen on the specs and thought, "Okay, I think I can be of value here," but then how do you apply fluid dynamics equations to acoustic research and stuff like that? I had no idea. So, I've got an idea now, but I had them teach me as we went through it. So, I found these couple brilliant audio engineers, Brad Evanson and Cesar Garcia, who also just happens to be a former Olympic diver, one of these complete underachievers in life. So, we got hired beginning of 2017. We did a two-month study. We were initially hired to create something from scratch, and then we said we could do it. We told them how much it would cost. They said, "Okay, well, we can't afford that, but now we would like your help to basically choose an off-the-shelf component," and so that's what we did. We were brought back in to help Dave and the team, David Gruel, who hired us at JPL. He was our supervisor at JPL, and he was the one spearheading everything and he had a couple ideas. There was a company that had released this new product that was a good contender for various technical reasons, but actually what the microphone I'm talking to you on now is a flight analog of the Mars EDL mic. So, this is the exact same microphone. This was one of the test models that I still have. This is a flight analog. This is a DPA 4,006 capsule into an MMA preempt, which is the exact same thing that was flown on Perseverance. They had a few very minor modifications, but acoustically, it's identical and if you'll notice, my voice sounds very clear, and that's why when people check out the audio recordings, you'll hear there's a clarity to these recordings. That's incredible. Especially if you check out Soul 16, which is a drive sequence. I mean, it's like your ear is right there. It's not muffled or anything. We did have to process the audio a bit to remove some background noise, but the actual sound is untweaked as it were.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, and it's absolutely astonishing. I mean, I know it's just the sound of wind and things like that, but I mean, getting sound from the surface of another world is so mind-blowing.

Jason Achilles: It's pretty cool. Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I had this deep emotional moment listening to it, and I know it resonated with other people because I'm like I need to share this with everyone, and at the time I was working as digital community manager at The Planetary Society, so I took that first bit of audio and I slapped it over a picture of a Perseverance panorama and put it up online and to this day, it is still the most watched video I have ever created in my entire career and that is... I mean, that just speaks to the interest.

Jason Achilles: It's funny because audio is discarded very readily as scientific validity sometimes. I think people think of audio maybe the way they think of a painting or something. It's like this arbitrary collection of... It's more thought of as being beautiful than useful, right? But then the imagery that we've been getting for decades from space that's scientific imagery is clearly regarded as such, but now that we're getting potential scientific use audio, it's still a hard sell, I think, for some people and it's also... The problem is audio's tricky. There's a lot of work we've done to make sure that everything we're doing is very authentic with how we're treating this stuff. I tell people, if you want to understand the importance of audio, just put earplugs in and walk around for a day and you'll rapidly realize how much more frustrating it is, just not hearing normal audio cues. I don't know. We think of it as enjoyment, but it really is... There's a reason it's a sensory system.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Absolutely. There's so much that we can learn about Mars because the conditions there in the air chemically and the atmospheric density, it's very different from what we have here on earth and how does that impact the sounds that we're hearing from this microphone?

Jason Achilles: Well, I mean, ultimately, I think people would ask me before this thing landed, okay, assuming this thing works, what do you expect to hear? And the analogy I like to give is that it's like if you were walking through the middle of Death Valley, what would you hear? You would hear yourself walking through the middle of Death Valley and not much else and you hear a little bit of atmospheric stuff, but really to me, I think the exciting part is hearing the sound of your own footsteps on Mars, except in this case, it's rover wheels, but one day it will be our footsteps, and then the audio becomes more useful if you're working on the surface, if you're drilling something or you're in loose terrain and you can hear these things, it's going to increase mobility. It'll increase your mental stability because you can actually... It's one of the few sensory awarenesses that we can give you a pretty accurate perception of. You're never going to smell Mars. Not really. You're never going to feel a gust of Martian wind on your face, but you can hear the audio. We can treat the audio in such a way where it's absolutely what you would hear if you were to hold your breath, not depressurize... horribly die and it was sticking your head out the window on Mars, but it'll be one of the few sensory experiences that will be accurate. You'll never feel the unfiltered sunlight touch your face on Mars the way you do when you walk out your porch. It's a different experience. Audio is one of the few things we can give you that will be absolutely correct.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I think what's cool for me about recording sounds on Mars is, yes, the wind is beautiful, but we can learn some really cool things just by listening to the sounds of the lasers pew-pewing ping off the rocks there, learn more about their chemical makeup and density and things like that. So, there are scientific applications for this, and that's why it's fun for me because as someone that works at The Planetary Society, we've been advocating for Mars microphones for literally over 25 years and it finally happened.

Jason Achilles: Yeah, that's actually when I first got this gig and did all the research and realized that you guys had been the ones supporting this since before Carl Sagan passed away, supported the first microphone, which flew on Mars Polar Lander. That was when I reached out to Jim Bell, who was the president at the time, and that's how I think probably what eventually how you and I met. Yeah, anytime I give one of those history talks, I champion The Planetary Society and everyone cheers. You got a lot of fans out there.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That makes me so happy, and I know you've got to feel really happy about your role actually getting this Mars microphone there because correct me if I'm wrong, but you've been a Planetary Society member since you were very young, right?

Jason Achilles: Well, I'll be fair. It actually did expire, but I was a member of The Planetary Society when I was like eight years old.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That's wonderful.

Jason Achilles: My parents had signed me up and I still have... Like somewhere, I've got a newsletter or something, and I was a member of two fan clubs as a kid, and it was you guys and the Weird Al Yankovic, close personal friends of Al.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yes. Got a lot of fans of Weird Al here at The Planetary Society.

Jason Achilles: It's hard to beat Al, but I did want to say though, because you mentioned the laser. So, something that I really want people to hear that are listening to this, we recently posted a sound file that's really, really cool because as far as I'm aware at least, it's the first publicly released Sound of Mars in stereo. There's two microphones on there, and the team that's responsible for SuperCam at one point, they told me about this earlier this year that they had activated both microphones during one of those laser firing sequences, and they never released it because they weren't able to get the audio from our microphone enough to where people would be able to hear it, but we've been using this really high-end audio processing software. It's very surgical and very intensive, but we were able to clean up the sound enough where we could hear these pops. So, then we were able to reconstruct and match up these two different audio files, which were in two totally different places online. So, we put them together at 30 popping sounds in succession, which are these tiny little laser ablations over a 13-second period or something like that. They go pretty quick, but basically the EDL mic is on the left. The SuperCam mic is on the right. Positionally, I think, their microphone is in a much better spot because it has to be. So, ours was a lot quieter, but we were able to balance it out, and yeah, it's stereo on Mars. It's pretty darn cool.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It is, and I love going back to all these websites and hearing these. I don't know. I want everyone to get an opportunity to just close your eyes, listen to the Sounds of Mars, but I did want to ask you about the EDL camera, actually, because I know the original plan was to try to get some sound from the Landing on Mars to go along with that beautiful footage that Perseverance captured of the landing, and then I just never heard anything else about that audio, and then heard later that it just didn't get captured. So, what happened there?

Jason Achilles: That one was a big bummer, and it was funny because... So, Dave Gruel who was our supervisor, as I had mentioned before, was the one who... If folks might remember, Perseverance landed on a Thursday, and then press conference was the following Monday and so they were really scrambling to get all that multimedia stuff back by then. That's when they shared the video with the up and down cameras on the skycrane and all that incredible stuff. What had happened? Yeah, basically the mic was activated and it recorded what I was told is that basically there was a communications issue between the digitizer and the computer onboard Perseverance, which is essentially like for people that work in a recording studio or have ever used analog digital converters that you hook up to a laptop. Every once in a while, you turn them on and they just don't work, and you turn it off and turn it on again, and as I say, it's like 100% of the time, it works right the second time, but this was a problem. I guess I wasn't aware that this was something they'd experienced and I guess it had happened infrequently. It happened a few times during testing and just the nature of the mission. There wasn't really any opportunity to get it straightened out and so it was an unfortunate occurrence that happened then.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: But that's okay. It just means we're going to have to do it again.

Jason Achilles: Right. Well, that's-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Send microphones to other worlds, at least the ones that have atmospheres that we can listen to.

Jason Achilles: Well, and what Dave did that weekend, which was really cool, is he managed to get another recording event before that press conference, and it worked fine that time. So, when Monday came along... I actually re-watched it again. It was really interesting. He sold it really well where he is like, "Well, we didn't get the audio. Sorry, but here's some great video," and then everyone forgets about the audio, and then he brings it back. He's like, "Now, however, we did get this," and he plays 17 seconds and it's that first little gust of wind that came back that was captured on Sol 2 from this mic, and somehow I thought everyone was going to be super disappointed, but now everyone was like, "Oh, it's amazing," and kudos to Dave for making that work and getting it done.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I know. Space is hard.

Jason Achilles: Space is hard. You know, kids, they say that, and you think, "Oh yeah, yeah," but then you do it and you're like, "Oh God, yeah, space is really hard."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It took several attempts for us to actually get a microphone to Mars. So, if you could, if you had infinite resources, what other worlds would you want to send microphones to?

Jason Achilles: Well, I lobbied really hard to become part of the Dragonfly mission to Titan.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh, yeah, because we did get a little bit of sound from European Space Agency's Huygens Probe when it landed on Titan, but I mean, Dragonfly, it was-

Jason Achilles: Kind of.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It was kind of. We'll count it.

Jason Achilles: It was a sonification of acoustic pressure data.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's not the same.

Jason Achilles: It's not the same. It's definitely better than nothing, but I did talk to them. I don't know officially, but my understanding is that they are working to include an audio component. I offered my services most diligently, but they're basically like, "Nah, we got this." I am working with some other folks on a couple different missions for Venus, and we're going to see if we can get some audio going there, which is not the first time. The Russians actually did do this back right in 1981.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: In the Venera missions,

Jason Achilles: Venera 13, yeah, had a microphone, which I would guess that mic that that they flew on that thing probably weighs close to what the whole probe is going to weigh. Like Russian '70s engineering, weren't the probes like five tons or something like-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh gosh, I don't know, but I believe it

Jason Achilles: ... insanely heavy and the microphone I've been... It's really hard to find any literature about this. As far as I can tell, it was just all completely solid stainless steel. I'm guessing based on pictures I saw. It looked like it was maybe about the size of a large beer can or something like solid metal and we're hoping to send something much similar to this, and I've been working with Rocket Lab who's sending a private mission there. We've been preemptively cleared to include a mic on that mission, but the whole mission just got delayed for a few years. So, we'll see what happens, but actually, I've already purchased the flight hardware and hopefully that'll go, and then there's the DAVINCI probe to Venus. We'll see if we can get something going there.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Oh, that's so exciting. I would love to hear the sounds of Venus.

Jason Achilles: Well, I think those are both atmospheric probes, so they're basically falling very fast through the atmosphere, right?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: You get the whoosh on the way down.

Jason Achilles: Yeah, you get the whoosh and you get some mechanical sounds, but the ones that... What I really would like to do is get something flight qualified so that next time we send hot air balloons, it can float in that 50-kilometer high weather balloons basically, and then you can really just listen, and maybe if you can hear the thunder from those lightning storms, that the theorized lightning storms on Venus, something like that would be I think just the coolest thing ever.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll be right back with the rest of my interview with Jason Achilles after this short message.

Ambre Trujillo: There is so much going on in space science and exploration, and we're here to share it with you. Hi, I'm Amber, digital community manager for The Planetary Society. Catch the latest space exploration news, pretty planetary pictures, and Planetary Society publications on our social media channels. You can find The Planetary Society on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and YouTube. I hope you'll like and subscribe so you never miss the next exciting update from the world of planetary science.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Any sound from a lightning storm on any other world would be amazing, but you just know it would be terrifying on Venus because everything is terrifying on Venus.

Jason Achilles: Everything is terrifying. Venus wants to kill you even more than Mars, and Mars really wants to kill you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It's so exciting that we're at a place and time when we can even begin to imagine and to build these missions that are going to be not just landing on a place like one of Saturn's Moons like Titan, but sending back audio and video as well. It's next level and every time we take one of these steps, it feels like, well, of course, we were going to do that, but no, it's mind blowing to me every time. I can't tell you how many times I've cried just watching that Perseverance landing video. I should be over it by now, but I'm not.

Jason Achilles: Well, you know what gets me every time is scientists crying. There's the landing, but I think what really tears me is when you hear the voice of the announcer. I made the mistake of like the day before Perseverance landed, Rob Manning, who he's worked on everything over there. Rob Manning's, he's amazing, right? He put together this video or podcast where he is basically talking about entry, descent, landing, and it's basically just so terrifying because he basically takes you through how actually hard all this is. Before I watched this video, I'm like, "This would probably be okay. We did this before, skycrane, yeah," and you watch that video on the end of it and you're like, "There's no way. There's absolutely no way. There's 20,000 things that are going to go wrong," and then when you're listening to the landing the next day, when that thing touched down, yeah, I broke down, actually. I can't believe it, and at that point, we didn't even know if the mic worked or not. It was just like the fact it didn't smash into a million pieces was like... People have no concept of how hard this stuff is. It's just very cool.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right, and to go from there to capturing sounds on Mars and then actually having a little helicopter roll out of the belly of the rover and land and just-

Jason Achilles: Yeah, it's ridiculous.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... took it around Mars like it was easy.

Jason Achilles: And it's still doing it. It's still flying. Thing's crazy. As far as I know, it's still flying.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, I believe so. It's wild. I was surprised it worked at all, let alone into the changing seasons.

Jason Achilles: Wow. I'll tell you what, that's something else I've been laboring towards is trying to get some audio on the next round of helicopters that they fly out. Just get something strapped onto that little tiny little mic and you can hear it flopping around, bouncing off the ground. It'd be amazing.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, I was going to ask about how much does your microphone from Mars weigh? Would it add a lot if you added it on Dragonfly, for example?

Jason Achilles: So, there's a lot of different kinds of mics, right? Like the one I'm talking to now is probably, it's on the heavier side. For Perseverance, it was okay because we had a mass limit of... I think they wanted to be under about 50 grams, which is it's light, but you can feel it in your palm. It's not a feather or something, but the mass constraints on that Mars helicopter, basically, it literally must weigh nothing, but like there's the kind of microphones you have in cell phones and things like that. MEMS microphones and even the SuperCam microphones are much smaller. The actual active element in it is much lighter than ours, but there's trades for these things and so there's some new technologies of MEMS-style mics that I think would be... That's what I'm actually working right now towards getting thermally and radiation tested to see if we could fly one of those as a tech demonstration on the next Mar's mission because you really don't know until you get there. I mean, you can put things in test chambers, but you don't really know until you get there and especially with some mics where you're flying through deep space for six months. I mean, you evaluate the materials and we make sure we don't have any materials that are going to exhibit off gassing and the vacuum of space, things like that, but at the same time, you're like, "This was not made for this." Like this mic I'm talking to you guys on was not made to go into space. For example, the factory will say, "Okay, this thing's been tested to negative 40 degrees Celsius." I don't know why, but that's what they tested to. That doesn't necessarily mean it stops working in negative 40. It just means that's what it's been tested to. So, you got to put it in your own chambers, and then you have to put it through vibe tests and all these things some of the audience might be more familiar with, but one of the worst parts about getting anything into space is just when it's got to go up on the rocket and it gets shaken to pieces, and that washes out a lot of tech. Then there's cosmic radiation and all these other things that, again, want to kill you.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Right, and your original speck for this microphone was very different. You had to go with these kind of off-the-shelf components, but is there anything from your original design that you really wish you could have had on this mission?

Jason Achilles: Well, the actual capsule itself was the identical.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Cool.

Jason Achilles: Yeah. We would've bought this capsule anyway and integrated into a custom pre-amplification system. The only thing that would've been very cool that we had built into our initial design is that there was going to be a second mic of a different design, mainly for... So, if one fails, hopefully the other one works because they're different technologies and being affected differently by the environment, but ideally if they both worked, you'd have a built-in stereo mic. We did put together that one stereo audio, but that was a fluke that even got recorded and it technically isn't stereo, but it doesn't sound very good compared to what it'll sound like when we do proper stereo on Mars and that's the biggest I don't want to say regret because it will happen, but it would've been wonderful to have that capability the first time around. Just gives you something to go back for. Or incorporating a small speaker on there for tonal calibration and playing some David Bowie or whatever work in the-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I was going to say, "Are you going to sing to the rover?"

Jason Achilles: I got an idea, a couple things. It's actually something I want to have talk to you guys about, but we'll discuss that at another time.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll discuss. I'm excited to hear this. I know that once your time working at JPL ended, you were still seeking ways to still be involved in space exploration and you're working on a whole new project now, right? What's going on with that?

Jason Achilles: When I knew my space career was going to come to an end if I didn't start something up soon, and I really didn't want it to come to an end because this is the coolest, exciting... Yeah, it's awesome. I love this stuff and so the whole idea for recording audio on Mars or any other planet came from was actually initially wanting to see the skycrane maneuver, but from a remote perspective and so the initial idea was to take a camera and as the skycrane maneuver was happening, we would eject this little camera ball with a camera inside it in a protective housing basically and it would be recording. From before you ejected it, it would hit the ground, bounce a little bit, but not too far, and you'd be able to watch the skycrane maneuver, but you'd actually be able to see it from the perspective of all the animations we've seen, which nobody's ever seen. We've seen the top view, the down view, but it's a totally different thing when you can be looking at it from a short distance away. It's like watching a rocket launch. If you're on the rocket versus standing next to it and that's where the audio component thought came from, because at the time, the friend of mine that I shared that with at JPL was like, "It's too close to the mission. There's no way they're going to go for this kind of wacky new technology that nobody's done before," but then we're like, "Well, what about audio?" And then it turned out, "While we were having that discussion, NASA was planning to include audio, so it all worked out." But I went back to that idea a few years ago while we were waiting for Perseverance to land basically and got together a team of this engineering company named Honeybee Robotics who is now actually part of Mars Sample Return. They just got a huge $20 million contract or something. It's an engineering company in Altadena right down the street there from JPL, and I pitched this idea to them and they loved it, and so they got behind it and sunk some money into supporting it, and we built an early prototype, and then we were able to get funded through NASA for a little over half a million dollars for an early development grant, which allowed us to test it on an actual rocket flight, but on earth, like a suborbital rocket test and so we did that about a year ago, I think. Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, I saw the footage of that in the Mojave Desert, right?

Jason Achilles: Yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: It was really wild to just see these little GoPros and balls essentially just jettisoning-

Jason Achilles: Basically, yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... off the side of rockets and then just looking back at the landing. I mean, anytime you get one of those moments when you can see a spacecraft doing its thing, that's just wild and I imagine what it would be like to just watch a lunar landing with one of these things.

Jason Achilles: Yeah, that's what I want the current five-year-old future astronauts of this world to see that and like, "Wow." I want that to be normalized. It's like, "Oh, another rocket landing on another planet that we get to watch." Yeah, that's the point. The video for that, if people want to go to my website, jasonachilles.com, and you can see the video that we got in the desert, and basically you can imagine... You would see exactly what you're seeing in this video, except instead of in Mojave, it would be on Mars or the moon. That's what we're doing now. We're basically looking at more funding to get this thing flight qualified for space travel. There's a lot of private landers going to the moon in the next few years. There will be bigger missions to Mars coming soon and so we want on board and we'll see what happens.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Just one more way to make space more accessible and exciting for everyone.

Jason Achilles: I think exciting is... Yeah, that's the key, right? I mean, probably you guys are all like this. A lot of engineers in the aerospace world are like this too, where you say, "Well, when did you get excited in space?" It's like, well, they were about five, six years old, and it was something, depending on how old they are, maybe it was the Apollo landings, or maybe it was the space shuttle or this stuff is... People's like, "Well, why do we send people to other worlds?" Because it's inspiring, and why would you not do something like that? Yeah, it costs a few bucks, but so does a lot of other way dumber stuff that we do.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: And yes, it's money, and yes, that money goes into a lot of jobs here on earth, but-

Jason Achilles: It does.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: ... how do you put a price tag on that level of hope and inspiration and international collaboration? I mean, I was six years old when I decided that I wanted to dedicate my life to space.

Jason Achilles: See, there you go. Five, six years old, boom, and here you are, educating, inspiring kids and adults, and how do you put a price tag on it? I mean, I guess you could work it out in terms of like tax revenue and support, public support and funding for things, but I mean, nobody says it better than Carl Sagan, right? He talks about us being a nomadic species by definition, and he says this much more poetically than I do. If we didn't have the intrinsic desire to explore, we would never have survived this long. Exploration is a necessary fundamental part of our existence, just the same as procreation. You can't stay sedentary as a species. We're exercising our evolutionarily implied right to explore, and this time we don't have to subjugate anybody or step on anybody's heads, or maybe there's some microbes that might be a little mad at us, but for the first time, humanity can exercise these feelings of exploration and you could even say conquest of this new terrain, but without actually doing anything terrible to other humans and there's something really, I think, deeply honorable about that level of exploration and taking a lot of technologies that were developed for warfare, rocketry and all these things and putting them towards exploration and science and imagination, and it's good stuff. Go humans.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well said. Just personally, I'd like to thank you for the role that you played in bringing us Mars microphones and helping bring to life this thing that Carl Sagan wanted back a few years after our founding. I think he would've been really excited to listen to the sounds of Mars, and that's a thing now. We get to look forward to a future where that's just a thing now. It's amazing.

Jason Achilles: People should do themselves a favor and just go to YouTube and google "Carl Sagan messages to Mars," and if you're not tearing up at the end of that, you might want to see a therapist because it's really... It was recorded just the same year he died. I mean, that's a true poet and science communicator saying all the things that we've been stumbling through, but it really is beautiful and he outlines it all pretty well and thank you for doing this. I mean, science communication is so vital now, and now's the right time to inspire all these kids. You know?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Absolutely, and that's part of why I'm so, so happy that after years of work, we finally launched our Planetary Academy Program for kids. It's our kids' membership program. I know you joining The Planetary Society as a kid was already exciting, but just imagine having that packet that's just for you. I feel such pride just being even a little part of that because I know how much that would've meant to me as a kid. So, I'm hoping that there's a whole new generation of kids out there that are getting excited about space, and maybe someday the next person who takes on Planetary Radio will be one of those kids that read one of those packets as a child. That would blow my mind.

Jason Achilles: I'll tell you, the last couple years with all this going on with the Mars audio, I've spoken to a lot of classrooms and a lot of young kids and space is just... It seems to be a level of cool that even like jaded high schoolers can't really turn away from. It was just pretty impressive. I think anything less than an astronaut and they're like, "Eh," but astronauts still wins.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, making more astronauts one recording at a time.

Jason Achilles: Heck yeah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, thanks for being with me, Jason. I really appreciate it, and hopefully, I'll hear more from you in the future when some other cool, amazing microphone gets put on another world. Thanks so much, Jason. I can't wait to see Jason's next Astronomy On Tap concert, but more importantly, before we move on to this week's what's up, please enjoy the short clip of the wind on Mars. Usually, I am not super happy about the wind buffeting a microphone here on earth, but when I sit back and really think about the fact that we have recordings of the breeze on another world, it's just one more reminder of the amazing things that can happen when we work together to explore the universe around us and now it's time for what's up with Dr. Bruce Betts, the chief scientist of The Planetary Society. I am joined once more by the ever-amazing Bruce Betts. Welcome back, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Hello. Incredible Sarah.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: See, I like this, being nice to each other.

Bruce Betts: It confuses me very much, but I like it as well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: So Bruce, what's up?

Bruce Betts: Well, planet's coming together. Venus and Saturn going to snuggle up next to each other, but they're low in the Western horizon. Shortly after sunset, Venus looking super bright like it does. Saturn looking yellowish, and they will get closer until the 22nd, and then they'll grow apart with Saturn slipping out of sight and Venus coming up higher and being with us for several months of me telling you, "Hey, it's super bright Venus." So, we're low on the West in the early evening, although it'll get higher, and if you follow a line from those guys up, you'll get to Jupiter looking bright and follow that line across to almost the other side of the sky and high up above, you'll find Mars, which is making a nice pairing with Aldebaran on the reddish star in Taurus, with Mars being the brighter one for now anyway. It continues to dim as it gets farther away from the earth. That was just outside in between torrential rainstorms and back in the normal clear skies of Southern California last night, and the winter constellations are looking lovely in the evening. We've got Orion and all of its friends up high in the evening, so check those out as well.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Are you one of the people that goes outside and just points up at the shiny object and says, "Look, it's Mars"? Because I am frequently that person and I wonder if I'm alone.

Bruce Betts: No, I am totally that person and my dogs are like, "Oh, cool."

Sarah Al-Ahmed: See, at least your dogs are in some way related to you. I'll be out there talking to total strangers. "Hey, you see that shiny thing?"

Bruce Betts: Yeah, no, I like to do that. People usually stay interested at least through what? One or two bright planets, and then they get scared and walk away.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Let me give you my full TED Talk on the Pleiades.

Bruce Betts: I'd watch that. All right, we move on to this week in space history. 1986, Voyager II flies past Uranus, giving us our one and only spacecraft flyby so far of Uranus and its friends. By friends, I mean, moons and rings, and well, you get it. 2006, headed to the outer solar system, another spacecraft launches new horizons off towards Pluto and Erikoff in deep, deep space and so that's this week in space history this week.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: I remember that day that the first images from Pluto came back. I literally had them printed and I was running around my work just like, "Have you seen Pluto?"

Bruce Betts: Have you seen Pluto?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: To this day, I still encounter people that have no idea that we flew by Pluto and took images of it. So-

Bruce Betts: No, it's actually the outline of the Disney character Pluto. Let's go on to-

Speaker 6: A random space fact.

Bruce Betts: So, I just want to mention for those who aren't familiar with how important explosive bolts are in space exploration. It just sounds terrifying, but these pyrotechnic systems or pyros are on pretty much every rocket and spacecraft out there to separate things. So, I know the Perseverance and Curiosity had 76 pyros that had to successfully blow to break the connections at the right times as they landed. SLS, Orion, they're everywhere. They're omnipresent, these little explosives inside bolts and nuts to make them break at the right time. I just think it's cool and I wanted to make sure the world knew.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, what's interesting about space exploration is that there are so many ways that things can explode and only a few of them are the good ones, but they're the ones that we need to actually do the thing. It's like that and fireworks are my favorite types of explosions.

Bruce Betts: Well, yeah. Yeah, these are very small. They're just enough. They're very localized shaped to break apart a connection, holding a rocket down, holding fairings on or holding upper stage thingies to lower stage thingies. That's the technical term. All right. We go on to the trivia question, in deference to the gamers out there, I asked you about an old-timey video game that was related to the solar system in such an important way. I asked you what planetary system was the setting for the majority of the original Doom video game? How'd we do?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We did really well. Actually, better than expected. It took me quite a while to go through just the massive amounts of people that came in for the trivia contest this week. Of course, people who are gamers are fans of old video games will know that the original Doom video game was actually set on Mars, or rather, I think it was partially set on one of its moons, Phobos. Is that correct?

Bruce Betts: Yes. It was mostly on Phobos, I believe, some on demos and parts of the games I never got to, but I believe it was a Space Marine. I don't know. That's usually the thing stationed on Mars who went up to Phobos, and of course, his entire group got killed and he had to work his way for some reason through level after level of hideous monsters, which is totally the way Phobos.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Totally, but the dice have spoken, and this week we have two winners. First winner is Jean-Marc Bernard from Lausanne, Switzerland, and winner number two is Tim Johnson from Walnut Creek, California, who wrote in longtime listener, first-time caller. Classic. There are two things I loved in my childhood in the '90s, outer space and video games, which I relate to a lot. So, I hope both Jean-Marc and Tim Johnson enjoy their beautiful images of Matt Kaplan that are signed by him. Matt Kaplan, of course, Planetary Radio's creator and former host.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, I've got a huge poster of him on my wall, but he refuses to sign it. Anyway, moving along. What else you got?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, well, we also had a bunch of different messages come in from people. Many of them gaming-related, but I did really like this one. It's from longtime listener, Mel, briefly Frogger Master Powell, from Sherman Oaks, California who said in law school, X years ago, a bunch of us went to a Westwood Village arcade one evening, and for about two hours while surrounded by teens, I had the high score on Frogger, still a career and life highlight.

Bruce Betts: Wow. That is-

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We also got a message from Neil Ashelman from Bettendorf, Iowa, who says, "For the first time ad astra, Sarah. Congrats on a wonderful first episode, and thanks for including me in the audio welcome. It was a treat," and if anybody out there hasn't listened to my first show that came out on January 4th, we added a cute compilation of all the wonderful audio messages that we got from people who called into our hotline. So, thank you, Neil. I really enjoyed your message and all of the other messages from people who called in.

Bruce Betts: Excellent.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: All right. I think it's time for this week's space trivia question.

Bruce Betts: All right, speaking of sounds from Space, whose voice was the first to be broadcast from space? Whose voice was the first to be broadcast from space? Go to planetary.org/radiocontest.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: We'll see how many people get this one right and this week we will be selecting two winners, and the prize is a NASA International Space Station 2023 calendar, and of course, by the time you receive it, January will probably be over, but there are still 11 more months in this trip around the sun for you to use the calendar, but if you would like to join the Space Trivia contest for this week, you have until Wednesday, January 25th at 8:00 AM Pacific Time to get us your answer.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody go out there, look up the night sky and think about your favorite date on a calendar. Thank you and goodnight.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: That was Bruce Betts, the Chief Scientist of The Planetary Society. We've reached the end of this week's episode of Planetary Radio, but we'll be back next week with Scott Bolton, the principal investigator for NASA's Juno mission to Jupiter. Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California and is made possible by our Mars-crazed members. You can join us as we continue to cheer for microphones on space missions at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Andrew Lucas is our audio editor. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser, and until next week, Ad Astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth