Planetary Radio • Nov 30, 2022

20th Anniversary of Planetary Radio

On This Episode

Louis D. Friedman

Co-Founder and Executive Director Emeritus for The Planetary Society

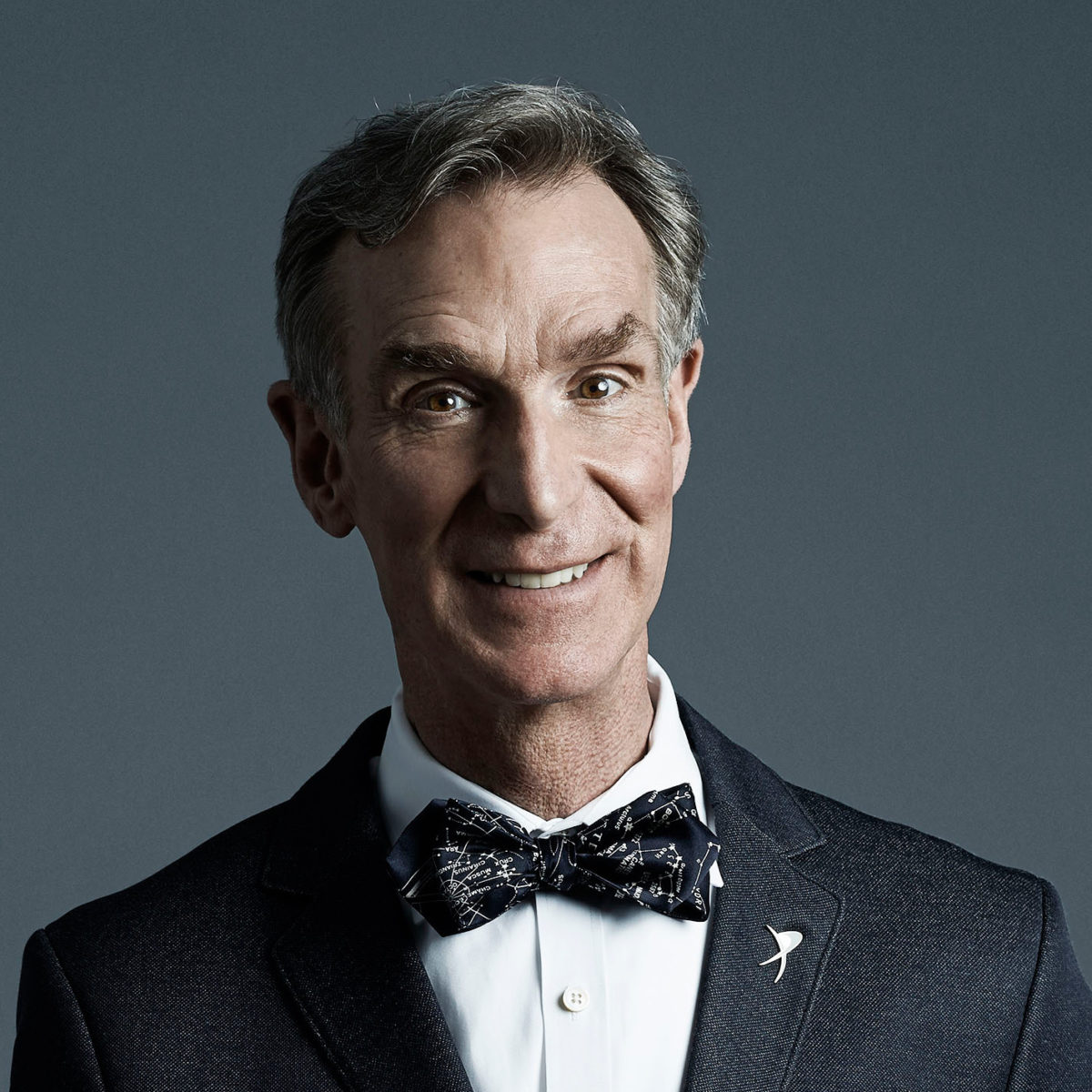

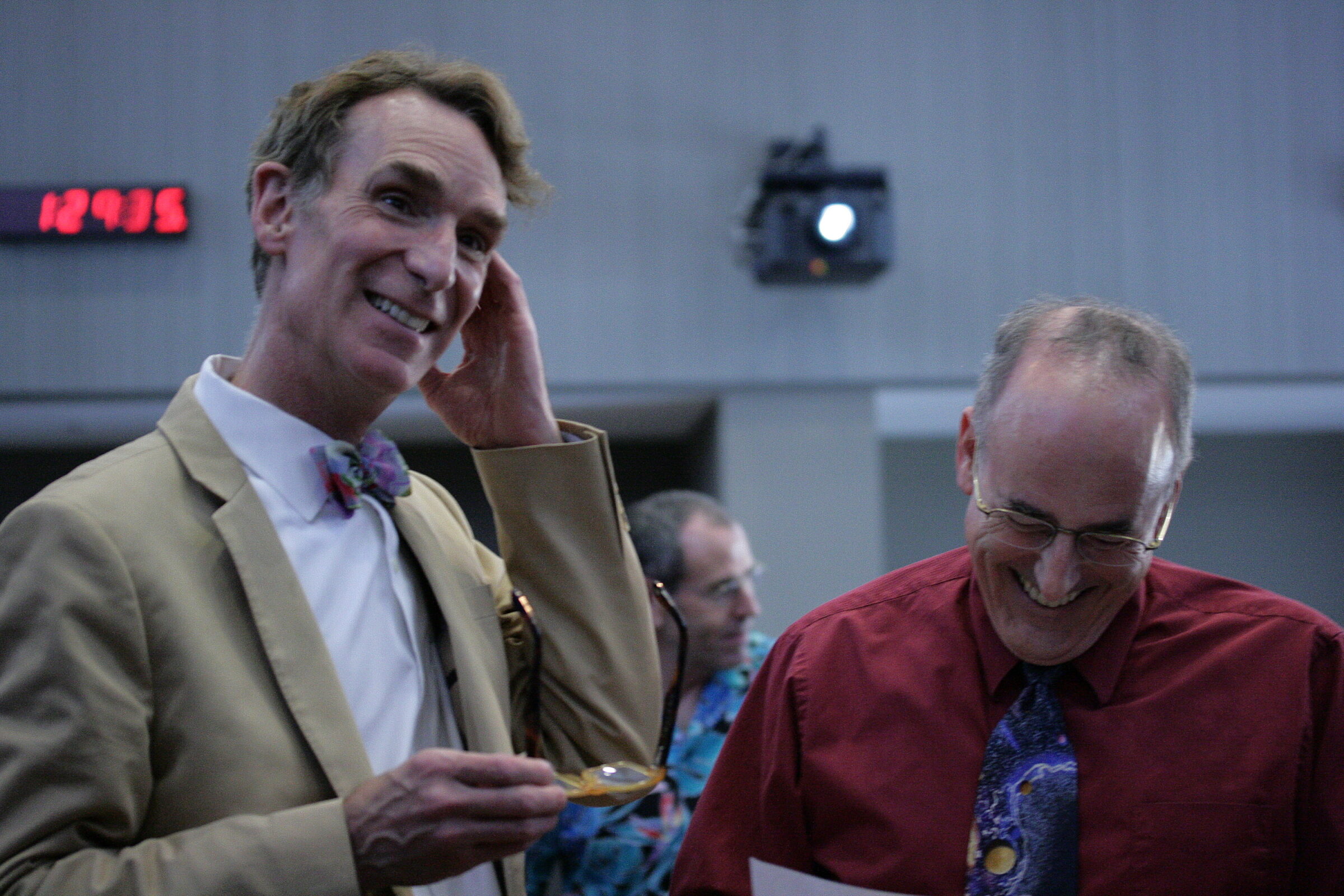

Bill Nye

Chief Executive Officer for The Planetary Society

Jennifer Vaughn

Chief Operating Officer for The Planetary Society

Sarah Al-Ahmed

Planetary Radio Host and Producer for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

Join our celebration with Planetary Society Chief Executive Officer Bill Nye, Co-Founder Louis Friedman, and Chief Operating Officer Jennifer Vaughn. Incoming Planetary Radio host Sarah Al-Ahmed calls our attention to several of the Society’s biggest accomplishments in 2022, and Bruce Betts shares not-so-random space facts about our public radio show and podcast.

Related Links

- Nov. 25, 2002: The first Planetary Radio episode

- Planetary Radio web page

- Planetary Radio has a new host

- Planetary Radio: 10 Must-Listen Episodes About Space Exploration

- The Planetary Society’s 2022 impact report

- The night sky

- The Downlink

- Subscribe to the monthly Planetary Radio newsletter

Trivia Contest

This Week’s Question:

Planetary Radio is 20 Earth years old. Approximately how old is it in Mercury years?

This Week’s Prize:

A Planetary Society Kick Asteroid r-r-r-rubber asteroid!

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, December 7 at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

Zeus was Artemis and Apollo’s father in Greek mythology. Who was their mother?

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the November 16, 2022 space trivia contest:

20th wedding anniversaries are typically celebrated with gifts of china. What would be an appropriate gift for the 20th anniversary of Planetary Radio?

Answer:

Listen to this week’s episode to hear three listeners’ responses to our request for suggestions of 20th anniversary gifts that are appropriate for a space show.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: Celebrating 20 years of Planetary Radio with Bill Nye and others this week on, well, you know. This is the premier of Planetary Radio. Hi everyone. I'm Mat Kaplan of The Planetary Society and host of Planetary Radio. Part of The Planetary Society's mission is to explore new worlds. You could say that's what we're doing with this new radio series. Another part of our mission is to share news and advocacy of space exploration with a world full of space enthusiasts. Whether you're hearing us live on KUCI in Orange County, California, live via the KUCI website or on The Planetary Society's website, planetary.org, we welcome you to this experiment. We also hope you'll be with us every week as we explore the exciting potential of this series, and we think we've got a great beginning planned with today's show. We'll talk with Dr. Lewis Friedman, executive director and one of the founders of The Planetary Society. Later in the half hour, you'll hear Bruce Betts the society's Director of Projects tell us what's up in the sky in his regular segment called just that What's Up? Have you heard about the Society's contest that will allow a young person to name NASA's new Mars rovers? Bruce will have that story too. But first, let's get underway with another of our regular features. I'll be back in just a minute. That's how it began on November 25th, 2002. A very special show this week as we mark two decades of Planetary Radio and begin a third. You'll hear Planetary Society co-founder Lou Friedman, chief Executive Officer Bill Nye, chief Operating Officer Jennifer Vaughn. Well, would it really be Planetary Radio without Chief Scientist, Bruce Betts and What's Up? We'll forego the usual space headlines in this already long episode. You can always find the latest in our free weekly newsletter, the Down Link. It and so much more are at planetary.org. This is also the time of year when we celebrate The Planetary Society's accomplishments across the last 12 months. Sarah Al-Ahmed is ready to help us acknowledge the biggest among these. Sarah, it has been a productive year well for us, for our colleagues at The Planetary Society, for all of our members and donors. We're going to be telling people how they can find out a lot more about some of our major accomplishments, but I know you've got a few that you want to go through just in a couple of minutes here today. Where do you want to start?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah. Well, it has been a really exciting year and as we approach the end of 2022, it's always good to look back on all the things that we've accomplished together. One of the major things that I'm really excited that we finally got to do this year is, award our first ever STEP grants. That's our Science and Technology Empowered by the Public Grant Program and this year we award our first two projects. So those are shaping up awesome, and we're really looking forward to seeing the outcome of those projects. We also awarded our Shoemaker NEO grants this year. We award those grants to help advance amateur astronomers who like to help protect Earth from asteroids so they can upgrade their technology and have better ways of tracking these objects. So we had eight winners this year from seven different countries, and already they've made huge strides in finding new near Earth objects to protect us, which is amazing.

Mat Kaplan: Of course, the Shoemaker NEO grants have a long history of benefiting amateur and even professional astronomers and terrific results that they've been able to achieve with these grants, these little bits of assistance that The Planetary Society has been able to provide. Where do you want to go next?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Well, next would be our Day of Action. This is something we do each and every year. It's our largest annual advocacy event, and it's also the largest of any independent pro-space organization in the world. In the United States alone, we met with 161 different congressional offices to advocate for different NASA programs. These moments have a huge impact on the funding for space missions. So if anybody wants to join us for next year's Day of Action, highly encourage it because it makes a huge impact.

Mat Kaplan: I so look forward to going back in person to Washington, which I know Casey's planning to do. We're going to go back to doing in-person Day of Action in the fall of 2023. Not quite ready for that for a variety of reasons in the spring when we'll do a virtual one. Got to bring up LightSail, right?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Got to bring up LightSail. Was a huge year for LightSail. Yeah, this, our crowdfunded LightSail, solar sailing spacecraft really exceeded our expectations. We only really thought it was going to be up there for maybe a year or so, but this year, it celebrated its third anniversary in orbit around Earth, and we got to put a model of our solar sail in Smithsonian Futures Exhibit in Washington D.C., which was a really wonderful moment for us. We got together with a bunch of our members there to actually see the exhibit and celebrate, which was a great moment. But of course, LightSail came to an end just a few weeks ago when it deorbited and burnt up in Earth's atmosphere, which of course was something we planned for. We actually learned a lot of great science about how to deorbit spacecraft with drag sails. So that was cool, but also a kind of bittersweet moment for us because our LightSail mission is now over.

Mat Kaplan: I remember when we thought it was almost impossibly optimistic to think that it would last in orbit for a year. Well, we did pretty well. Okay, bring us back home. How do you want to close?

Sarah Al-Ahmed: For me, the biggest thing and for you as well is that Mat, you're retiring after 20 years of amazing shows here on Planetary Radio. As we turn over into the new year, I'm going to be stepping up as the new show host. So I think that's a big moment for both of us.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely. Hopefully, for our audience as well, although we hope it'll be a more or less seamless transition. I think everybody out there, you probably have just heard great evidence of why we are turning over the show to Sarah. Sarah, thanks so much. Great review. I should mention that for our members and donors, we will be doing our annual review of the Society's big accomplishments. That'll be a live webcast with the boss CEO, Bill Nye, and a bunch of other great folks. I'll be moderating it once again. Keep an eye on your mail. We will let you know when that's going to happen. It will probably be in mid-December. There is an article you can look for at planetary.org that also goes through all of this. Sarah, thanks again.

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Thanks, Mat.

Mat Kaplan: Bill, Jennifer, a pleasure to have you on this 20th anniversary program for Planetary Radio. It's not the only thing we'll talk about, but I'm honored to have you sitting at the microphones here in The Planetary Society studio ready to talk about, well, I don't know. What else would you like to talk about?

Bill Nye: Well, we've been around 42 years and you've been broadcasting, making the showing for half of that. That's really amazing, man.

Jennnifer Vaughn: I'm going to jump in and make a slight correction because we're celebrating the 20th anniversary on November 30th. November 30th happens to also be the incorporation date of The Planetary Society. So it's two in one, so it's 43 years-

Bill Nye: I was going to say-

Jennnifer Vaughn: ... of The Planetary Society and 20 years for Planetary Radio.

Mat Kaplan: I was going to bring it up if you didn't.

Bill Nye: So just notice this is what you get by having Jennifer Vaughn as Chief Operating Officer. She has corporate memory. So it was November 30th, 1979. We keep saying 1980. It's like about the time somebody bought a desk or something.

Jennnifer Vaughn: Exactly. Because not much work happened in that last month of '79.

Mat Kaplan: And I went on the payroll 22 years ago, so 21 years into the existence of this organization. For two years, I was doing other stuff, but I had this dream, which we're going to talk to Lou Friedman in a few minutes and find out why he let me make it real.

Bill Nye: So while we're talking about making it real, when I... Just changed the subject back to-

Mat Kaplan: Me.

Bill Nye: When I first took over 11 and some years ago, went on for a few months, this and that. I said to Jen Vaughn, "You know we should hire Mat full-time." She said, "Yeah, I did that a couple months ago." You were part-time, everybody.

Mat Kaplan: That's great.

Bill Nye: Mat was part-time here at The Planetary Society and part-time at California State University Senate-

Jennnifer Vaughn: Long Beach.

Mat Kaplan: Long Beach.

Bill Nye: ... Long Beach. You were going back and forth doing both teaching, video production and maybe radio production down there. We stayed down there south of here.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, we taught a little bit, but mostly I ran a television studio that had the cable channel and did the professional production work for the organization for the university.

Bill Nye: You did professional production?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, I tried. I had good people. I had good people. Like you, I had good people and it was a lot of fun. I was part-time here at the Society, longer than I have been full-time still. Lou Friedman tried to get me to go full-time very early on and I kind of went-

Bill Nye: What were your responsibilities at the beginning?

Mat Kaplan: Oh, this and that.

Bill Nye: Oh yeah. There's a lot of-

Jennnifer Vaughn: You were working on the website.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Jennnifer Vaughn: You were writing a lot.

Mat Kaplan: I had no idea what I was doing. I was made webmaster the day after I think I arrived on the payroll part-time, and I had never... I didn't know any html. I didn't know what I was doing because the webmaster had just left and she was the one who had said, "Hey, you should hire this guy." I was just going to write. I was going to do content. Maybe somewhere in the back of my mind I was thinking of doing this radio show, because who knew from broadcasting back then? And I did. I commuted up for a long time. You were here, Jenny, it just, the timing wasn't right. I stayed part-time at the Society and went back pretty much full-time at the university and they gave me more stuff to do there, community relations. I had the IT group, which was kind of a laugh, but I knew how to talk IT even if I couldn't do it.

Bill Nye: So that's information technology?

Mat Kaplan: Yes, sir. Yes, yes.

Bill Nye: For us old guys?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Jennnifer Vaughn: So I remember, I'm glad this came up about the part-time status, because one of the things that we just marvel at today with you and trying to think about how do we move along with Planet Radio without you is that you do it all.

Bill Nye: You do so much, man.

Jennnifer Vaughn: You're a one-person band, you do it all. Then to think back and think that you were doing it all on a part-time, that's amazing. I'm not sure how you're doing it on a full-time position, but wow, you were managing Planet Radio as a part-time version. That is amazing.

Mat Kaplan: It's been interesting. It's-

Bill Nye: We'll go with that.

Jennnifer Vaughn: Of course, it's developed a lot too. Your role has developed as well. So you've always had the radio show, but you've become the voice ambassador for The Planetary Society. So you are [inaudible 00:11:29]-

Mat Kaplan: Present company excepted I think because, yeah... We were doing an event a couple of weeks ago and somebody was so excited to see me and I said, "Hey, you know Bill Nye is coming. You're excited to see me?"

Jennnifer Vaughn: Sure excited to see you, Mat.

Bill Nye: Mat, you've grown this audience of people that love you.

Jennnifer Vaughn: Yeah, that's [inaudible 00:11:47].

Bill Nye: But the other thing that I find striking is, you book all the interviews, interviewees and the people generally want to come back. They want to come back on your-

Jennnifer Vaughn: They do.

Bill Nye: ... show because you do such a good job preparing and how to say, letting them talk.

Mat Kaplan: That's the part I love the most. It's meeting and getting to talk to and share conversations with heroes every week. Heroes that are famous that have walked on the moon, heroes that maybe have never been heard of outside of their own university or lab until they come on this show. That's the great joy of doing this.

Bill Nye: So did you, Mat, really, what got you hooked on Planetary Science? How did you find The Planetary Society?

Mat Kaplan: Well, here's the secret I shouldn't reveal. I was a member of the National Space Society before I was a Planetary Society.

Bill Nye: Well, this is different bunch.

Mat Kaplan: And I did a little bit of stuff for them. We even had a TV project with the NSS. I knew The Planetary Society was out there. I don't know if I read a Carl Sagan book or if I got something in the mail and I joined up and then there was this search for Planet Fest volunteers. I thought, "Oh yeah, maybe I can help out." I ended up running all of the media stuff for that Planet Fest.

Jennnifer Vaughn: Wait, so that was Planet Fest '99 then.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. That's right. That's right.

Jennnifer Vaughn: I have some pictures of you.

Mat Kaplan: No kidding.

Jennnifer Vaughn: I remember seeing with, running the AV for Planet Fest '99.

Bill Nye: This was in the Pasadena Civic Center?

Mat Kaplan: Yes.

Bill Nye: This had Buzz Aldrin, this had Mars Polar Lander, [inaudible 00:13:23] except on Mars, we don't know quite what it would sound like. And Mars Climate Orbiter, which also crashed.

Jennnifer Vaughn: Yeah, tough time.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. We still had a good time [inaudible 00:13:34].

Jennnifer Vaughn: We did. It was great party even though we didn't know what we were celebrating other than just being together and loving space.

Mat Kaplan: Being together. Well, that's it. You asked me how did I fall in love with planetary science? I'm old. I go back to Mercury. I'm remember running to see a Mercury launch, to watch an Atlas take off.

Bill Nye: On television.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, on television, black and white television. I caught the bug then and never lost it. Got my first telescope when I was 10. Still don't really know how to use it nearly as well as most people who have telescopes, but I do love digging it out now and then. I quote you all the time. I always credit you the PB&J, the passion, beauty and joy.

Bill Nye: Love the PB&J.

Mat Kaplan: We have been through changes over the last 20 years, 22 from my start. The organization has certainly evolved a lot. What'd you say? 11 years for you now, Bill?

Jennnifer Vaughn: I think it might be 12.

Bill Nye: Yes. I believe it is 12.

Jennnifer Vaughn: 2012. Yeah.

Bill Nye: It was September of 2010. Yeah, so it's been 12 years. And Tempest Food get, man.

Mat Kaplan: There were some difficult times and-

Bill Nye: Really?

Mat Kaplan: You would know better than me. I am very grateful because everybody stood by, if not me, at least by Planetary Radio through thick and thin. Times are-

Bill Nye: Well, the thinness, everybody, we had overinvested in a spacecraft that was not working. This would be the early versions of LightSail. You can't run an organization like this without some money and people working. So we had to think carefully about where we were spending our money and redirect it. Thanks to you all listening, we found supporters who thought that the solar sail spacecraft would be pretty great and we pulled it off. This is after... You were there for both failures, right? Jen, you were there?

Jennnifer Vaughn: Oh, yeah. Oh yeah.

Bill Nye: Cosmos 1.

Mat Kaplan: Me too.

Jennnifer Vaughn: Yeah. And I remember we were all living that together, waiting for those signals that never came.

Mat Kaplan: Well, I'm glad you went in this direction because this of course is the other thing we want to talk about. We're late if anything, talking about this because by the time people hear it, LightSail will have met its demise, its glorious demise for a couple of weeks. This is another just wonderful success story to come out of those difficult times. I think that's the word I used a few moments ago, right, to become this truly glorious success. I thank and congratulate the two of you. I mean, I'm a member and so I had that, my little piece of that spacecraft and I just couldn't be more proud of what we have been able to accomplish.

Bill Nye: We did. We accomplished the mission. We raised altitude, increased orbital energy using sunlight. We took these pictures. I keep going off with the pictures. They're astonishing. I know it's a radio show, but the LightSail pictures, everybody thought they'd be good, but they're so impressive to me and it's because of everybody listening. So thank you. Thank you for supporting LightSail. So we have advanced our mission, advanced space science and exploration. The same day, maybe the same 24 hour period, that LightSail burned up, Artemis 1 launched carrying near Earth Asteroid Scout, NEA Scout. The solar sailing community is a small one. Everybody sees each other at the conferences and stuff. So Les Johnson, who will be on the podcast pretty soon-

Mat Kaplan: Very soon.

Bill Nye: Yeah. He finally got his dream solar sail to launch the same day that ours burned up. It's a passing of the atmospheric incineration torch so, feel good about that. But as of this recording, we haven't heard from it. Well, maybe it'll get hit with a cosmic ray and it'll fire up. So everybody, one of the things they told me, and by they, I mean the engineers on LightSail 1, it wasn't working. We couldn't hear from, couldn't communicate with it. They said, "Oh, don't worry. It'll get hit with a cosmic ray and the computer will reboot." I don't know how else to express it. Are you high? What do you mean it's going to get hit with a cosmic ray? Apparently it did.

Jennnifer Vaughn: Then it did.

Bill Nye: And it rebooted. But then on LightSail 2, everybody, Bruce and the crew made sure that there was a system that didn't need a cosmic ray to reboot.

Jennnifer Vaughn: Exactly. We could manually reboot.

Bill Nye: So, Near Earth Asteroid Scout may, maybe by the time this airs, it'll have gotten a jolt. Who knows?

Mat Kaplan: I sure hope so.

Bill Nye: But well, hope's not a plan, but I'm sure people are working on it real hard. We nudged space exploration along because everybody thinks, this goes back to Carl Sagan and Lou Friedman, everybody thinks that solar sails have their place in exploring the solar system especially and perhaps way, way out there beyond the solar system.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Well that's what we've always heard from Lou Friedman solar sails or at least LightSails, maybe driven by lasers, the only practical technology we have for reaching the stars.

Bill Nye: And Voyager's out with 22 light hours?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, something like that.

Bill Nye: That's what she said?

Mat Kaplan: That's right.

Bill Nye: Last week?

Mat Kaplan: That's right, that's right.

Bill Nye: Wow. That's a long way, everybody, at the speed of light. So I'm not changing the subject, it just shows you that space exploration is where we accomplish mighty things and that's what Charles Elachi, who was the head of JPL for a while, liked to quote Teddy Roosevelt, "Dare mighty things."

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, it's a good motto. Jennifer, were there times before we started to see LightSail 1 coming together and the troubled, but successful test. Were there times when you wondered whether we'd be able to achieve this great success?

Jennnifer Vaughn: So, so many times? Going back to what Bill just said, dare... What did you say? Dare mighty.

Bill Nye: Dare might things.

Jennnifer Vaughn: Dare mighty things people. Yes. Yeah. We knew what we were trying to do was difficult, was complex. It was audacious, it was all those things. It was going to cost a lot of money and take a lot of time. There were so many times along the way where we were at a crossroads and having to ask the hard questions of, do we continue? And-

Bill Nye: Everybody, we talked about giving the hardware, this is the CubeSat, 10 centimeters by 10 centimeters by 30 centimeters less... It really is literally smaller than a loaf of bread. We're going to give it away to the Air Force Research Lab. Maybe those guys want it. Is there a university in Utah who'd want to take it apart and see if they could make it work? This went around and around for a while, [inaudible 00:20:43].

Jennnifer Vaughn: Yeah, it's part of the job of having to question all the time, are you the right ones to be doing what you're doing? Or, is it really better to be involving someone else or partnering? And so we had to examine it a lot.

Bill Nye: Anyway, this is all whiskey under the bridge, as we say in country music, but it's really gratifying. Mat, you've been through the thin and then now, the pretty thick. I mean, we're not out of control, but things are pretty good right now for the organization, because you have engaged so many listeners. So thank you for that. People love your show, man.

Mat Kaplan: You're very welcome. Takes one to know one. It has been the thrill. It has been the greatest professional thrill of my life. I am also thrilled to know who's coming in to take over this microphone [inaudible 00:21:36].

Bill Nye: Oh, Sarah's going to be great, everybody. Yeah, we had listed 400 applicants for [inaudible 00:21:41].

Sarah Al-Ahmed: Yeah, I think it's about like that.

Mat Kaplan: It was close. It was something like that. It was over 300 for sure.

Bill Nye: That's a lot. That's a lot. Anyway, Sarah has the creds. She-

Mat Kaplan: She won fair and square.

Bill Nye: Yeah, yeah, and-

Jennnifer Vaughn: She did. She did.

Bill Nye: ... she has the enthusiasm and the professional expertise and that, the thing you want is this academic experience being real astrophysicist and then science communication coming from the Griffith Observatory. Everybody, if you've seen the movie, what is it? Rebel Without a Cause, they drive the Griffith Observatory like the real deal in Los Angeles. For those of you around the world who've never seen the Griffiths Observatory, go on the electric internet and see where it is. It's perched on this hillside, which in the 1920s was this extraordinary way above the clouds. I use the word perch, placement-

Mat Kaplan: It's a good word.

Bill Nye: ... of this beautiful facility. She worked under all the real deal people over there.

Mat Kaplan: And we were able to get her to come here. So yeah, Rebel Without a Cause. Don't forget the Rocketeer, key scene in that wonderful [inaudible 00:22:47].

Jennnifer Vaughn: Yeah, yeah. Absolutely.

Mat Kaplan: What a great movie. I think there have been a few others-

Bill Nye: Is there anybody in the space business that you haven't interviewed?

Mat Kaplan: Oh yeah. Yeah. You know-

Bill Nye: How many times you had Homer [inaudible 00:22:58], right?

Mat Kaplan: Oh, only a couple. Only a couple.

Bill Nye: A couple.

Mat Kaplan: We haven't talked to Homer in a long time.

Bill Nye: Well, it's really-

Mat Kaplan: As I told Anne Druyan two, three weeks ago at this desk, at this virtual desk-

Bill Nye: I was going to say she wasn't here.

Mat Kaplan: No, she wasn't here.

Bill Nye: All that is.

Mat Kaplan: But my greatest professional regret... Well, there are two people, Neil Armstrong. But that's an easy one to understand because he hardly talked to anybody in the media business. But Carl, and I'm really sorry that I missed out on talking to Carl. I came close. I was in the same room once in 1976 as Viking 1 landed on Mars. I've told this story, it's in my newsletter that, here I was, this scruffy college kid-

Bill Nye: Oh, the Viking. It was '76.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Bill Nye: Absolutely. It was '76.

Mat Kaplan: There he was across the room surrounded by network people and major newspaper people and we were these college punks. We did kind of ask, but it was clear that we just did not measure up and it would not have been a good use of his time to talk to us.

Bill Nye: But he loved talking to everybody. When you're in love, you want to tell the world, as he so often said. So Mat, he would've talked to you a few more times.

Mat Kaplan: Well, and then Anne said that thing, which just blew me away and will be with me the rest of my life, that she was sure that he'd have been as fond of me as she is.

Bill Nye: Oh, come on. Come on. That's fabulous. No, I heard that. That was great.

Mat Kaplan: That was great. What does it mean where we are? I'm going back to LightSail now and away from me, where the organization is now, that we were able to achieve this, what it says about this organization, that we made this happen and we're moving on to other things?

Jennnifer Vaughn: Well, I'm actually going to bring it back to you too, in that answer, which I wanted to share that kind of emotionally where I've been sitting for a while with both LightSail and the recognition of this 20 year mark and this shift of handing the baton over to Sarah and seeing you move into different roles. It is this moment of deep pride for the organization and what we've been able to accomplish. So often you don't know what you're accomplishing in the moment. You only see it when you're looking back sometimes and you recognize in the case of Planetary Radio, how valuable it's been to people around the world, the people that you have touched and inspired and motivated to become more deeply involved with space. It's countless. We have no idea how many people you have touched over this period of 20 years. It's astounding to look back on that. And I feel so proud and excited and so sad all at the same time. It really has a bitter sweetness to it all. And LightSail does the same thing. LightSail outdid itself. It performed so much better than we ever imagined. It lived two and a half years longer than ever anticipated. It's such a beautiful thing that it's coming to an end in the right way and it's so sad all the same time. So, I've just been contemplating this a lot, I think recently and this shift for the organization on multiple fronts. We are starting anew. We're starting anew with Planetary Radio, we're starting anew with new projects. We don't yet know how those are going to develop. We might not know the impact that we're having until we're looking back at it one day saying, Wow, that was really good stuff."

Bill Nye: But with all that in mind and the bitter sweet nature of this week, Mat, two things. First of all, none of it would've happened without Bruce Betts and you have him on the show every week.

Mat Kaplan: Every week.

Bill Nye: He is a character. Every week, and he'd led the science and technology of both LightSails so shout out-

Jennnifer Vaughn: And those cameras. Those pictures.

Bill Nye: ... to Bruce or gentle voice talk out to Bruce. This is natural. That is to say, I will miss holding up my phone, waving in people's faces, "Look at LightSail. Here's the map, here's where it is." The app. We had a phone app where you could see the map of where LightSail was at any time. I'm going to miss that badly, but on the other hand, it's a stepping stone. The best I still think is yet ahead and if you're going to pass the baton to anyone, we picked a good person. Sarah is going to do fine.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, she is.

Bill Nye: You'll never be forgotten, but it's part of the growth or change of the organization. As Jenn and I have mumbled to each other from time to time, we want The Planetary Society to be thriving next century.

Jennnifer Vaughn: Absolutely.

Bill Nye: So things have to change. Change has to be built in and you're going to have Lou Friedman on this podcast, right, in-

Mat Kaplan: Moments.

Bill Nye: Yeah, I took over from Lou, I mean the guy wanted to get on with his life. The organization's changed a little bit, how, it couldn't help it, but that it has to change. So, I'm sorry, LightSail's burned up. I'm going to miss it. It does bring you to this thing. Well, what are you going to do next? What's next? Well, the STEP grants are pretty cool.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, they are.

Bill Nye: And I just tell everybody again, yes, I want to explore planets writ large. Yes, but I thought about that interview that you went with Ann, that you did a couple weeks ago talking about Carl Sagan and his message to Mars. You guys, I want to be alive when life is found elsewhere.

Mat Kaplan: Oh gosh. Oh gosh. Please let it be so worth.

Bill Nye: I want to be alive for it. If I'm not, I did my best. Then I want to have the Earth not get hit with an asteroid. That's a really important thing to me as a science educator.

Jennnifer Vaughn: Those are very good goals.

Bill Nye: Well, as a science educator, the mystery and the story of what happened to the ancient dinosaurs is amazing. It's compelling. There was no explanation for it, no good explanation, my whole life. As I say, in the 1980s, I was a productive member of society, paying taxes and all that stuff. I was in the workforce when it was discovered that it was almost certainly an asteroid that finished them off. So the only preventable natural disaster and very reasonable to me that solar sails will have a role in finding them, going way out, looking, station keeping with the earth at an orbit closer to the sun than we are and looking for asteroids. I can just see it. Ooh, I can see it. So anyway, are we rambling or are we staying focused on the future?

Mat Kaplan: This is the future. There's so much more that I'm looking forward to and I'm glad that I'm not going to disappear. Some of the stuff that-

Bill Nye: What are you going to be? Sticking around?

Mat Kaplan: A little bit. I'm going to camp outside. Some of the stuff that Jennifer has very kindly generously asked me to become involved with is very exciting. In particular, some of the work that we're going to be doing with our member community, which people will be hearing more about soon is very exciting. You know, planetary defense. There's another planetary defense conference coming up. I know. We're going to be involved with that.

Bill Nye: It's every two years, everybody. I am very excited about Planetary Academy getting kids and-

Mat Kaplan: Oh yes, of course.

Bill Nye: Yeah. So I was in meetings when I first joined the board in the 1990s where Bruce Murray would slap the table and do, "Young people, we've got to get young people." It's pretty clear, we got to engage people before they're about 10. So that's what we're going to do now, finally. I'm excited. I'm so excited about the future.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. If only we had a leader who has done more than any other individual that I can think of to introduce young people to the-

Bill Nye: Well, it's right. Just took a few years-

Mat Kaplan: ... [inaudible 00:31:03].

Jennnifer Vaughn: You're well positioned.

Bill Nye: ... to get revved up.

Mat Kaplan: I have seen these materials. My grandson and his new stepsister, they're going to be members. They're going to be part of the academy. I am thrilled to go through all that material with them. It's going to be fun.

Bill Nye: It's going to be fun. We're going to grow. That's key to the future. We're going to grow. Tell all your friends. If you tell five people, and they tell five people, pretty soon we'll be huge.

Jennnifer Vaughn: And so on and so on.

Mat Kaplan: I think that's illegal. I think that that [inaudible 00:31:33]-

Bill Nye: Well, telling them's not illegal. It's getting their cash.

Mat Kaplan: Now, we're rambling. I want to close by thanking the two of you because of what you have done for this organization and what you have done for Planetary Radio.

Bill Nye: We hired you full time and what? You grew it to within the top 1%-

Jennnifer Vaughn: Oh, brilliant.

Bill Nye: ... of science podcasts, right? You did that, Mat, with your diligence.

Jennnifer Vaughn: Yeah, it's you. You did that.

Bill Nye: You're finding the interviewers, interviewees, interviewing them expertly and you did all the editing, taking all the mm, uh, ah, out. It's took a lot of your time for years and years, 20 years.

Jennnifer Vaughn: You've been the voice of The Planetary Society-

Bill Nye: So thank you.

Jennnifer Vaughn: ... in a very personal way. So you've been part of people's lives for 20 years.

Mat Kaplan: Well, fortunately that the voices of The Planetary Society will carry on. Your two are among them. You've proven that again just in the last few minutes. Thank you both.

Jennnifer Vaughn: Thank you.

Bill Nye: Thank you.

Jennnifer Vaughn: Thank you, Mat.

Mat Kaplan: A quick break and then I'll be back with the man who gave me this dream job. Planetary Society co-founder and solar system explorer, Louis Friedman.

Bill Nye: Hi everybody. Bill Nye here, CEO of The Planetary Society. Everything we do from advocacy for missions that matter, to funding new technology to grants for asteroid hunters, and sharing the wonder of space exploration with the world only happens thanks to friends like you who share our passion for space. When you invest in the Planetary Fund today, a generous member will match your donation up to $100,000. Every dollar you give will go twice as far as we explore the world of our solar system and beyond, defend Earth from the impact of an asteroid or comet, and find life beyond earth by making the search for life a space exploration priority. With you by our side, we'll continue to advocate for missions that matter for years to come. How about powering our work in 2023? Please donate today. Visit planetary.org/planetaryfund. Thank you for your generous support and happy New Year.

Mat Kaplan: Lou, thanks very much for being the first and very appropriate first guest on this broadcast version of Planetary Radio.

Louis Friedman: Well, thanks, Mat. I'm certainly glad to be here and certainly glad to talk about things Planetary and The Planetary Society. I really love the name Planetary Radio and let's make that our goal, to make this a Planetary Radio show.

Mat Kaplan: 20 years later, we're still trying to make this a truly Planetary Radio show each week. It is a pleasure and an honor to welcome back that first guest, Planetary Society co-founder and our executive Director Emeritus, Dr. Lewis Friedman. Lou Friedman, my first boss, the man who-

Louis Friedman: First boss at The Planetary Society.

Mat Kaplan: Yes. First boss here. First boss of any note. I hope my old boss at Cal State Long Beach isn't listening. The man though, who got this started, who allowed me to begin this experiment 20 years ago, almost to the day, not quite, and two years before that, brought me on the payroll. I think I'd been a volunteer for about two months. So I guess I've owed you for at least that period of time. Thank you.

Louis Friedman: You owe me your career.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Louis Friedman: Now I can think about how you should pay me back.

Mat Kaplan: Yes. Give that a lot of thought.

Louis Friedman: Well, Mat, I'm certainly very glad I did it. As we were kind of talking at another time, I wasn't sure what I was doing at that time. I wasn't sure that Planetary Radio was a thing that would have any legs to it. It was an experiment for the organization and I wasn't its biggest backer. There was people on the staff who much more, and of course you, but there were people on the staff who much more strongly supported the idea. But I think one of the things I did right was, allow things that I wasn't sure of to continue. It wasn't doing any harm that's for sure and it did very well. I congratulate you on the 20 years of producing it and doing it. It certainly has become terrific with a lot of legs.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you. As I said to Bill and Jennifer minutes ago, as people are listening to this, it has been the greatest joy of my professional life to be able to do this show for 20 years and meet the people that I have met because of this program. It started with you. You were also the first guest.

Louis Friedman: Well, thanks.

Mat Kaplan: I also think about how I felt when I was allowed to join the organization. At least from my viewpoint, it worked out pretty well all around.

Louis Friedman: Well, it was a good time for The Planetary Society. As you know, at that point, and this is all history, but we were full of optimism about the Cosmos 1 solar sail effort we were doing. That was a big venture. That was the first time any private organization was trying to do its own space mission. It had a lot of complicated interfaces with the Russians, of course and we were in testing programs with them. I think that was the year... Well, 2002 I think was the year we had our test launch with them. It was also a time of optimism about getting the Mars program to recover from the 1998 mission failures and The Planetary Society had played a significant part in getting a redefined Mars program. Of course, with the help of Dan Golden, the administrator, and Wes Hunters, the Associate Administrator for Space Science, but a commitment to sustain continuing Mars exploration, which of course, resulted in a spirited opportunity going a couple of years right after that. So it was a turn of the century, but it was also a turn of lot of things in Mars exploration for the society and the conducting a solar sail mission and in your activity, in getting Planetary Radio started,

Mat Kaplan: I think back even further too, well before my time with the Society, except maybe as a member, as Jennifer pointed out a few minutes ago, 43 years on the day that this show comes out, 43 years since the three of you, Carl Sagan, Bruce Murray, and you got together and said, "We need this organization." You make me think of it again when you talk about what was happening 20 years after that, or 23 years after that when we were still in the business of making sure that NASA stayed in the business of exploration.

Louis Friedman: Well, that's right. The society was formed at a time when NASA was actually the very highest level, was making a decision not to do planetary exploration and to get out of it. That's why we were formed. That was the basis of our advocacy. So that was a crucial time. I think we played a role in keeping planetary exploration in front of the nation as the program got rebuilt. It was also a crucial time in world affairs. The U.S. and Soviet Union were in the middle of the Cold War then, or not the middle, but... It was very early in the first couple of years that we took on the challenge of international cooperation, not just as a way because international cooperation is good, but as a way of stimulating interest in planetary science and planetary exploration. Soviets at that time were doing Mars missions and Haley's Comet mission and had a space station. U.S. had none of those things. We were trying to accelerate our program by bringing international cooperation into it and we were very successful in that too.

Mat Kaplan: And there's great documentation of this in your book. We're going to talk about your new book too, that's not out yet, but the one called Planetary Adventures, and your personal role in all of this, including all those trips to what is now Russia, was still the Soviet Union back then.

Louis Friedman: Well, Planetary Adventures from Moscow to Mars that I wrote is really a book that's written for you and me. It's not a best seller. It doesn't have that broad appeal to the general public, but it does document in a way that I think means a lot to those of us in here what was going on in the world and what was going on in the organization at that time. I was very fortunate, extremely fortunate to have adventures like that as part of my job here.

Mat Kaplan: Do you know my colleague, Casey Dreyer, our Chief Advocate CEO Space Policy?

Louis Friedman: He actually started work while I was here, so I brought him on too.

Mat Kaplan: I forgot that that was still happening. It was after we had the place on Catalina, that beautiful old house and we had our interim facility on Grand Avenue here in-

Louis Friedman: Pasadena, right.

Mat Kaplan: ... Pasadena. I think of how Casey, he's the embodiment of the advocacy work that you three founders begin way back in 1979 and just how that role continues for the society. I mean, that must make you pleased.

Louis Friedman: Well, it's grown a lot. I can remember the first tentative move when I went to Bruce and Carl and I said, "I think we need a Washington consultant." And, [inaudible 00:41:27], then we get recommendations from all our advisors, "Well, you need to have a Washington office." I said, "No, we're not going to do that, because people who have Washington offices get diverted right away. They get sucked up by politics." Knowing me, I would get sucked up by politics instantly. So I said, "I know better than that." So we hired a Washington consultant and then we hired a couple of others and we had various people who worked with us for years. That was the extent of our advocacy. Bill Livingston was our first Washington consultant. Then of course Lori Garver, who became deputy administrator of NASA. She was our Washington consultant for a while.

Mat Kaplan: One of my favorite people, one of my favorite guests.

Louis Friedman: Of course, I spent a lot of time in Washington in the political world, even though I was living here in California, but now you have several people here at the organization involved in advocacy and I'd say that it's different. When I was executive director, when Bruce and Carl were here, we didn't want it to be the dominant part. It was important, but we didn't necessarily think of it as the dominant function of the Society. That's probably good. I'm not sure, but it is a difference now.

Mat Kaplan: I'd love to ask Bill Nye or Jennifer Vaughn if they agree with you that it's the dominant part of what we do now. I'm not sure, but it really big, right?

Louis Friedman: You don't have things like the Mars Rover testing and the Mars balloon testing and the major kind of big activities we were doing like that and of course, ultimately the solar sail, but that was starting. It started even back in 2008 and '09 and continues to that day. So I think the projects that, I mean, you have good projects, but I think, right now advocacy is a bigger part of the organization.

Mat Kaplan: I see what you mean. What about the outreach side of what we do, which Planetary Radio, I hope is still a good example of this?

Louis Friedman: Sure. Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: There's so many channels that we have available to us now, which just nobody even dreamed of back then.

Louis Friedman: We didn't. We were very proud of the planetary report, which got out-

Mat Kaplan: Of course.

Louis Friedman: ... to between 60,000 and 100,000 over its time, and so over the years it's gotten out to over a million people in many ways. That was our outreach, of course, before the internet. Now, you have many more other things. That's a whole subject way beyond the scope of this show, Mat, with all due respect, way beyond maybe the scope of any such show, the whole notion of how different it was in the days when there were four or five broadcast channels and dozens of newspapers in various cities, several science magazines, and there was no such thing as the internet. Was that outreach more effective, less effective, or is there too much noise now? I could argue this, there's too much noise now and it's not as effective, but I could also argue the other way is, that it reaches people that it never reached before.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, yeah. I absolutely see your point. How did solar sailing fit into the mission of the Society? Was it there from the beginning at least as a dream?

Louis Friedman: That's a very hard question to answer succinctly. Bruce Murray as my boss at JPL was an enthusiast of solar sail. When I was working on solar sail at JPL, he was like the chief advocate. He made me go on trips with him to make the pitch to NASA management. He saw that as a great opportunity, of course, in the context of rendezvous with Haley's Comet at that time.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, very ambitious solar sails that [inaudible 00:45:26].

Louis Friedman: So, Bruce was in that sense an enthusiast. Carl was always enthusiastic about... I think a lot of people don't realize this. First place I ever met Carl was as a chair of a technology committee for NASA and not as a scientist. He was looking into the ways of using advanced technology in missions. So he was also enthused with the idea of it, but none of us had saw any practical role that the Society could play in its development. There were a whole lot of private groups in the 1990s trying to do solar sails and we didn't have any part of that for, there was no clear case that it fit our mission, which after all isn't about technology, it's about going to the planets. But what happened was opportunity. The opportunity was, we were working with the Russians by this point in the late 1990s on a number of innovative ideas, including the microphone that ultimately went on the 1998 Mars Mission. And in one of those meetings with the Russians, they said they had these inflatables they were developing and they could make inflatable booms. If we could provide sail material, they would do all the work of getting the launch and developing the spacecraft for us. So we had a job of just providing the sail material. Well, that's something we knew how to do because we actually had done that in connection with the Planet Fest in cooperation with the World Space Foundation years earlier. It looked like a good opportunity so we jumped on it. I remember Carl and I walking, I think it was here in downtown Pasadena, and he looks at me one day, he says, "We're doing pretty good. We got this program and we have this thing and the organization seems okay. We might possibly someday get to the point where we could do privately-funded space mission of our own."

Mat Kaplan: Really? This was from Carl?

Louis Friedman: Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: That's great.

Louis Friedman: I said, "Well, Carl, that's pretty ambitious."

Mat Kaplan: It was.

Louis Friedman: This was before commercial space flight talk and all these other things. I said, "But you know, it... " So immediately then, 1998 or 1999 when the Russians made this thing, and I talked to Bruce about it, and Carl sadly was no longer with us, we said, "Okay, it's worth a try." We got funding for it. We got some key funding. Here's a story I don't know that you know very well. There's a group here in Pasadena called IDEA Lab with two Caltech founder, people from Caltech who had founded it and they were trying to do a private mission to the moon. Tom [inaudible 00:48:23], who ultimately was our LightSails spacecraft designer, was actually their chief engineer working on this lunar mission. So he introduced me to Bill and Larry Gross. I made the pitch that the Russians had this idea, and if we could get a $50,000 study to see how much substance was behind it, it might go somewhere. So they said, "Well, okay, that sounds interesting. Well, let us think about it." Well, they had a board meeting and on their board happened to be a guy by the name, maybe you heard of him, Elon Musk. Well, and I knew Elon because he had been very interested in Mars exploration at that time.

Mat Kaplan: Still is.

Louis Friedman: Well, we might argue that. Anyway-

Mat Kaplan: Well, maybe not exploration, but yeah.

Louis Friedman: Okay. So I went up to Elon at a thing we were at, and I said, "Elon, it really would help if you could push the solar sail idea with Bill and Larry Gross, because I think they'll come up with the seed funding for us to look in and whether there's any substance behind us." Elon was interested because he was also flirting with the Russians to figure out if they could do launch vehicles for his idea from private Mars missions. So he said, "Oh, maybe." And he did. So Elon was, I give him a little credit for pushing the idea with them. We got the study and the study came back quite positive. A couple of us went over to Russia. Bud Shermer was a key guy and Jim Cantrell and I, and we went over and we were impressed with what we thought would be the good work that could be done on the spacecraft. We came back with a positive report. Unfortunately, the person who took over as CEO at... Anyway, he didn't want to do it and so we had to come up with other funding, but we did. That worked out. Of course, among our great funders on the whole Cosmos 1 effort was Annie, Anne Druyan and Cosmos Studios and she got behind it. That made the whole thing a go.

Mat Kaplan: I am still very proud of my windbreaker, my Cosmos 1 windbreaker.

Louis Friedman: Oh, I almost wore it today.

Mat Kaplan: I thought about it too. It has a wonderful Cosmos Studios logo on it in addition to some others. I had never heard that story about Elon, that Elon Musk helped get some of this-

Louis Friedman: And he joined the board. He was on our board in-

Mat Kaplan: Yes, [inaudible 00:50:50].

Louis Friedman: ... Planetary Society for several years as well.

Mat Kaplan: I still remember with tremendous fondness and with great pride that day in 2005, even though it didn't come out the way we had hoped, wasn't the spacecraft's fault, when we were all in the carriage house at the old headquarters.

Louis Friedman: Lucky you, I was over there.

Mat Kaplan: I don't know. I'd say lucky you with your satellite phone in your hand on that ship-

Louis Friedman: No, I never had a satellite phone. Oh, that was 2002. The satellite phone on the ship was the 2002 launch of the test flight.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, of the test flight. Wonderful [inaudible 00:51:30].

Louis Friedman: In 2005, I was in Moscow at the Mission Operation Center.

Mat Kaplan: Boy, that shows you how bad my memory is. But yes, we were talking to... we were in touch because that was the control center for the mission in that old carriage house, a hundred year old carriage house. At that time, a hundred years old. As I said, I'm still very proud to have been part of that. I do wonder if it had not been for that Cosmos 1 effort, would we have gone on with this revolutionary idea of doing it as a CubeSat, which you also got underway?

Louis Friedman: I'll tell you that story too, because I came back from Russia, very unhappy.

Mat Kaplan: Of course.

Louis Friedman: Not just unhappy because I've had a lot of missions associated with, I know about missions failing. I was at JPL when the Mars missions failed. I saw delays on missions. That didn't bother me, but what bothered me is there was some flimflam in our launch vehicle situation that I write about in Planetary Adventures. I won't repeat it here. So I was pretty unhappy. I came back and I said, "We're not going to do this again, no. First of all, we don't have a plan to do it again. We're not going to do it again under the same situation. Everything's different." Furthermore, the Japanese had already launched a Carlos, and so I knew we wouldn't be the first solar sail. So I was kind of negative. Charlene was pumping me up.

Mat Kaplan: Charlene Anderson-

Louis Friedman: Charlene Anderson who was [inaudible 00:52:55] our editor of the Planetary Report.

Mat Kaplan: And your deputy, right? As Executive [inaudible 00:53:02]?

Louis Friedman: Yes. Yeah. So we talked and then everybody was saying, "We got to try, got to try." And Anne Druyan was, bless her heart, she was strong. "We'll raise money. I know this. I'll try this. I'll do that." So what was I going to say? "No, no, we're not"? Then out of the blue, the folks at Marshall Space Flight Center call us up and say, "NanoSail-D failed," also on launch from a NASA launch. Ironic, isn't it? Marshall Fox called us up and they said, "Well, NanoSail-D, we have a spare spacecraft. If we give you the planetary site, if we give you the spare spacecraft, you're pretty good at getting launches, maybe from the Russians, maybe from the French, or maybe even commercially here. Would you take the responsibility of launching it because our programs being discontinued?" So I thought about it for a day. I talked to the staff, I talked to the board, and I called them back and I said, "Yes, we'll take it." We spent nine months talking to them and they never could figure out how to take yes for an answer. They never could figure out the transfer mechanisms. Then they decided to give it to DOD or something like that. I don't know what happened. But meanwhile, Jim Cantrell, Tom [inaudible 00:54:21] and I were meeting going over the NanoSail and we said, "This is just nothing more than a CubeSat. It doesn't have a radio, it doesn't have cameras, it doesn't have a good altitude control system. So it's not that good a spacecraft. We could do that. We can build the cubes. We can get a CubeSat and build these things ourselves." So that's what led to the decision to do LightSail.

Mat Kaplan: And the road ahead was still long and hard. Now, here we are speaking about two weeks after the end of that LightSail 2 mission, three and a half years in space in orbit, constantly reoriented itself, proving that a solar sail even of the scale of the CubeSat could raise its orbit as it circled the earth. I sure hope that you take some pride in all of this, this long, long road that led to this success.

Louis Friedman: Pride, and humility, I mean, because I didn't predict anything like this. I predicted it would have a few months in orbit, it would do its little energy maneuver and then it would be done. We didn't think of it as a resilient spacecraft. We thought of it as a fragile spacecraft. We also knew that it had donated Mylar sails that we had to do a lot of deployment tests on. We knew it was built in a small facility up in San Luis Obispo. There was a lot of things that we had to make. We were doing it as not an amateur effort, well in a sense, an amateur effort, but by professionals, but a privately funded effort. So I never predicted it would be this resilient and long. So hat's off to the team that did it and the team that operated it and everybody else. I was talking to Dave Spencer just a week ago about it. It remarkably well also proved something about solar sails that we didn't know when we first got into business. Both Icarus and LightSail, the only two solar sails that have ever flown missions, solar sailing missions, worked longer and better than expected. They were resilient. Space is benign once you get up there. You have to get up there and there's a long arduous road that you referred to, but once you get up there, if you have a good vehicle, it's fairly benign. I think there's a lot of lessons to be learned from LightSail. One of the disappointments, not disappointments, one of the jobs remaining to be done, if I can still task The Planetary Society to do anything is, they got to do better at getting the word out about it. It's not that well-known in the professional community. I had a leader in the space agencies come up to me say, "Did that LightSail ever fly?"

Mat Kaplan: Oh my goodness. Really?

Louis Friedman: This was just a few months ago. I go to meetings now, I'm doing some work already now in a different area, but also involving solar sails and they show pictures of NEA Scout and they show pictures of NanoSail, which is not a solar sailing vehicle. Then they mention The Planetary Society is doing one also, but this is the one with results and it hasn't hit much of the professional community, engineering community the way I think it should. So that's a job to be done.

Mat Kaplan: Okay. I'm just the radio guy, but I'll pass it on. And then it's so interesting that we may have done a better job with the general public than we did within the space community.

Louis Friedman: That's true. The general public doesn't know the first thing about NEA Scout or NanoSails and they do know the LightSails. The leadership here will tell you, just as I told people in my day, our constituency is the public, not the engineers. That's correct. So I'm not saying anything is being done wrong. Don't misunderstand that. I'm just saying I want to see it more recognized technically.

Mat Kaplan: I'm with you on that. There's one more thing I want to bring up regarding solar sailing, LightSail. That is, the guy who has been the program manager for quite a few years now. You were just in his office and he was updating you on LightSail 2. It's Bruce Betts. Why? Because he's another guy that you brought into the organization. He could not be prouder of his project there, LightSail 2.

Louis Friedman: Well that's great and give credit where credit is due again. Yes, I did bring him into the organization, but again, it wasn't my idea to bring him into the organization. It was Bruce Murray's idea to bring him into the organization. Bruce and Charlene at that time too, advocates of getting that kind of help and Bruce was known and very good. I always say about myself, I never have good ideas. I know what to do with other people's good ideas, and that's what I think my strength was.

Mat Kaplan: It sounds good in principle. I probably would only say, I think I could name a couple of good ideas that originated from you, but hey, even if you are right about that, that's something to be proud of in itself. You have another reason to be proud. You have a new book coming out, which I know next to nothing about because I searched the internet, there's no word about it yet. What is this book and when and where are we going to see it?

Louis Friedman: Well, it's going to be published a year from now. It's being published by the University of Arizona Press. I just got the page proofs today, so I know it's real.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, congratulations.

Louis Friedman: The title of the book is Alone, but Not Lonely: Exploring for Extraterrestrial Life. I have also got the very good news today that a very dear colleague of mine May Jemison-

Mat Kaplan: Oh yeah, of course.

Louis Friedman: ... is writing the forward for the book, and she's written it.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, that's lovely.

Louis Friedman: I just read it today and so I'm in a good mood.

Mat Kaplan: Well, we picked the right day for this conversation

Louis Friedman: And anyway, but the book is Alone But Not Lonely. It started out in my mind with a negative thought. Because of solar sailing, I used to think that solar sail was the segue to interstellar flight. But as I got into the subject more and more deeply, both from a point of view of what solar sails can do, but also what laser sails, which was going to be the way to do interstellar flight could do, I realized that's just not the case. Laser sails, there's a effort by Starshot, this-

Mat Kaplan: Sure. Breakthrough Starshot.

Louis Friedman: ... called Starshot Breakthrough Initiatives. I'm on their advisory committee, so I'm supportive of the study, but you think about it, the mission they came up with can send one gram, not one ounce, nothing as big as one ounce, one gram to the nearest star, not to the desirable star, not to the best exoplanet, not to the most habitable exoplanet, just to the nearest one. So one gram to the nearest planet. It takes a 500 gigawatt laser operating on a farm in the southern hemisphere to do that. So it's not a way to explore, it's a way to do a one shot mission. At that, it's one gram that'll pass by that planet at 30% of-

Mat Kaplan: 20% of the speed of light. Yeah.

Louis Friedman: ... the speed of light. 20% of the speed of light. It's trying to see the light. It's probably not going to see much of anything. So I realized that's the best interstellar flight can do. That's not the future. Meanwhile, I got working on project with Slava Turyshev at JPL, looking how the solar gravity lens, which is caused by the bending of light, goes around the sun, comes to a focal point. If you fly at that focal point, which is really a line, a focal line, you can magnify an exoplanet by a hundred billion times. That's the way to explore exoplanets. So that's why the title of the book is Alone. We're not going to get there. I don't think also that there's no likely ever discovery of intelligent life in the universe, but what we do know, or what we're pretty sure of, the universe is teaming with habitable planets and we have a lot to learn there. So the whole book is basically, starts out with the negative idea about interstellar flight and the negative idea about no other intelligent life in the universe, and comes up with a whole new field of comparative astrobiology, studying exoplanets for the different forms of life that are in the universe.

Mat Kaplan: And haven't you been working the last few years on concepts that could get us out to that focal point on that focal line using sail technology so the-

Louis Friedman: Yeah, that's where the solar sail work has come in. Stayed active in [inaudible 01:03:33] and consulting with JPL and Slava Turyshev and the Aerospace Corporation on that. Yes.

Mat Kaplan: I'm going to have to dig up the coverage that we've done of this in the past with you and Slava, and we'll put those links on this week's show page at planetary.org

Louis Friedman: Well, I think you were at the NIAC and you interviewed him-

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, we sure did.

Louis Friedman: ... in connection with the NIAC study.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. This was funded by NIAC, the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts group that you have advised right for [inaudible 01:04:01]?

Louis Friedman: Yeah, I'm on their external council.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Yeah. Exciting stuff. Lou, I don't know who you'll be talking to about that book when it comes out in a year. I hope it will be me, but it could be my replacement, Sarah. Sara Al-Ahmed, who is just going to do a terrific job carrying on this show. I doubt that you've me

Louis Friedman: Yeah, I don't think I have.

Mat Kaplan: Well, you will. You will, and I think you'll be pleased.

Louis Friedman: Good.

Mat Kaplan: She certainly represents my hopes for the future of this organization, the organization that you helped to create those 43 years ago.

Louis Friedman: Well, that's great. I'm very proud of this organization. It's like a baby that's grown up and now is doing things that different than I might have, but that doesn't matter. They're doing great, and I'm very proud.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, Lou. Thanks for getting it all underway. By the way, thanks for again for the job.

Louis Friedman: Okay. Enjoy your retirement.

Mat Kaplan: Such as it is.

Louis Friedman: I should have said that to you. Enjoy your retirement.

Mat Kaplan: They're going to keep me busy here. They're going to keep me doing [inaudible 01:05:09].

Louis Friedman: All right.

Mat Kaplan: We're back with Planetary Radio and Dr. Bruce Betts. Bruce Betts is the Director of Projects for The Planetary Society. We actually had a little trouble deciding how do we introduce this guy, because he's done a lot of things and continues to do a lot of things. Bruce Betts, welcome to Planetary Radio.

Bruce Betts: Well, thank you very much.

Mat Kaplan: Of course, we hope to make this a regular thing because this segment, which is at least tentatively called What's Up, not to say what's up, doc, because somebody else owns that. But what's up? Because one of the things we're hoping you're going to be able to talk about every week is what's up? What's up in the sky? And we're going to talk about what's up in the sky in a moment. But I think you've also got a little bit of space history for us.

Bruce Betts: I do indeed. This week we are lucky enough to have a truly unusual space history note. On November 30th, 1954 in the state of Alabama, a 10 pound meteorite slammed through a roof and hit Elizabeth Hodges in the stomach while she slept. She was okay, only bruises and scrapes, but it does represent one of the only times in known history that a meteorite actually hit a person, fortunately for her, after coming through the roof.

Mat Kaplan: Bruce, I just played the first time I introduced you for What's Up, back there in 2002, November of 2002. That was fun. You'll have to listen in.

Bruce Betts: No, I fooled you before. Earlier today, I listened to the whole show.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, I'll be darned.

Bruce Betts: Because I knew you were going to try to be tricking me.

Mat Kaplan: There's no fooling him. He's the chief scientist of The Planetary Society. What's up?

Bruce Betts: Oh, there's so much up in the sky. I'd love to gush about our anniversary and I will, but first Mars. So Mars is getting closer to earth their orbits. So the closest approach of Mars to Earth this time around is on December 1st. Those of you may know the opposition, the opposite side of the earth from the sun for Mars is December 8th. Those indeed can vary and not be the same date by up to two weeks because of the elliptical nature, particularly of Mars's orbit. So anyway, go out and see it. It's almost as bright as Jupiter. It's the brightest star in the sky because it's at opposition. It'll be rising around sunset in the east and setting around sunrise in the west. It's that really bright reddish thing. There are all sorts of bright stars in its area, but nothing as bright as Mars. Well, unless you catch it when the moon's nearby. In fact, let's talk about that, because we're going bold. For our 20th anniversary, I'm going to discuss something that I may have discussed before, but not giving you directions. That's an occultation of a planet by the moon. So the moon will pass in front of Mars as seen by most of North America and most of Europe. If you're on the southeastern side of either of those, nevermind. But if you're not, you can check it out. You can learn more about how to do that if you go to planetary.org/night-sky, and then follow the link to the things that are up in the night sky this month, and we'll give you some links to find out exactly what time on the night of December 7th into the 8th, it will be disappearing and then reappearing. Binoculars will help with checking that out so you can actually watch it disappear behind the moon. We also have Jupiter and Saturn up in the evening sky in the Gemini's meteor shower, but we'll come back and talk about that next week. It peaks December 13th and 14th, all sorts of stuff going on. Happy anniversary, man. We move on to this week in space history. I will mention the same thing I mentioned in that very first show, 1954, Elizabeth Hodges becomes one of the only people in history known to be hit by a meteorite. A several kilo meteorite crashed through her roof, fortunately, slowing it down and just caused bruising, but yeah, it's like, "How'd you get that bruise?" "Oh, I got hit by a meteorite." "Yeah. Okay, sure." A couple other quick things. 1998, Unity and Zaria modules were connected starting the construction of the International Space Station. 2014, you know that Orion capsule that's out hanging out around the moon, right about now? It's first test flight with no humans, of course. First test flight was 2014, 8 years ago. On to random space fact to Mat. Happy anniversary, Mat. Here's where I get to talk about you. Over its 20 year history, Planetary Radio has had more than 1000 unique shows. Mat has a thing about not feeding out repeats, so there have been hardly any in the history of the show. It airs on over a hundred radio stations last I checked, via podcast, has a gazillion people listening. I just checked, has over 1100 reviews on iTunes with a 4.8 out of five average. I expect you to improve that over the next few weeks.

Mat Kaplan: I'll do my best.

Bruce Betts: Every single show, this is the amazing thing. This just doesn't happen out there and for normal people, but for our Mat, he produced, edited, hosted every single show. He did everything except for those of us who drop in and blather with him and the talented guests. He did everything. You're awesome, Mat. I will never say that again.

Mat Kaplan: Once is enough.

Bruce Betts: Dang, you're recording. Shoot.

Mat Kaplan: Let's go on to a terrific 20th anniversary contest.

Bruce Betts: I asked you what would be an appropriate gift for a Planetary Radio. I thought I'd change the pronunciation. Now, Planetary Radio 20th anniversary for weddings, 20th anniversaries, it's China, traditionally. What did we find out? We found out all sorts of great things. Man, I've read through them myself, and it's one of those cases where it truly is too bad. We only can read a few on air because they're cool.

Mat Kaplan: That is so true. We got tons of great ones. We apologize. It's already a long show. We just don't have time for more than three. I will get us started. This one came from Devin O'Rourke in Colorado. Here goes, I'll do my best. "Although it isn't celebrating matt-rimony, I suppose a good gift could be a mattress or maybe a ticket to the matt-inee. A good matt-ch could be some aromatt-ic tomatoes, or-

Bruce Betts: I believe that's to-matt-oes.

Mat Kaplan: You say, yeah, nevermind. Light scale schematic? Really, none of this matters. The real gift has been unmatt-ched talent of the ultimatt-e host of Planetary Radio. I just wish I could remember his name right now." Thank you [inaudible 01:12:12].

Bruce Betts: Wow, that's very impressive.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, you take the next one.

Bruce Betts: We move on to this one from Mel Powell in California. He suggests a t-shirt that says in big letters, "Go out there, look up in the ice sky and think about," and then in smaller print, "every single one of the things, I have told people to go out there, look up in the ice sky and think about for 20 years." But wait, he didn't forget you. And a Planetary Society themed doormatt, because you know matt." You probably have never heard that before, huh?

Mat Kaplan: You know what's cool about this? I have a door mat that says, "Hi, I'm Mat." Thanks, Mel. All right. Here's the last of the ones that we'll read, and it happens to come from our poet laureate in Kansas, Dave Fairchild. "Back in the decades 2002, that's back before podcasts were cool, a guy named Mat Kaplan decided to host a session that took us to school. We learned about planets and random space facts with Bruce as his trustee sidekick. So if you are thinking-

Bruce Betts: Side kick.

Mat Kaplan: ... appropriate gift, I'd go with engraving a brick." And why have we chosen this? For self-serving reasons. You want to explain?

Bruce Betts: Yes. If you'd like to memorialize someone like Mat or someone you actually like, I got to make up for saying nice things earlier, you can go to somewhere on planetary.org. You can probably put a link in, but go check out how to Buy a Brick that will be installed with your words on it and probably at Planetary Society headquarters. Either that or Matt's backyard.

Mat Kaplan: No, I think we'll stick with headquarters. I got one for my family. Yeah, there are a whole bunch of them out there. I'll walk all over them. We're going to get, for all three of these guys, we said a Voyager t-shirt from Chop Shop. Chopshopstore.com, where all The Planetary Society merch is. Great place. We're going to give each one of them, all three of these guys a Voyager Mission t-shirt. So congratulations one and all.

Bruce Betts: Congratulations. Shall we move on to the next contest, Matt?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, let, let's do that.

Bruce Betts: I wouldn't want to leave the 20th anniversary behind quite yet. Planetary Radio is now, I can't believe it, 20 years old earth years. How old is Planetary Radio in Mercury years?

Mat Kaplan: Ooh.

Bruce Betts: In Mercury years and approximately, you don't have to get the fraction of a year, but like we say, ages on Earth, in Mercury years, go to planetary.org/radio contest. Get us your entry by?

Mat Kaplan: Let's say by December 7, Wednesday. December 7 at 8:00 AM Pacific Time. You might just win yourself... Hey, we've only got a few more of these to go, at least during my tenure here. How about a rubber asteroid, a kick asteroid, rubber asteroid from The Planetary Society?

Bruce Betts: Ooh, very traditional. Very nice. I like it very much.

Mat Kaplan: Bruce has already given me the greatest anniversary prize anybody could hope to get. He gave me, and I think some other people may have been involved, correct me if I'm wrong, a montage, a whole bunch of wonderful still photos from my 20 years of Planetary Radio. You are featured in many of them, and there is a story behind almost every one of them. Maybe we'll figure out a way to present this in a tangible way online. I absolutely love it, and I want to thank you from the bottom of my heart, from the top to the bottom of my heart. I really loved it. I have a 20th anniversary gift for you, but it's taking longer to get it made than I thought it would so it may end up being a last show Mat hosts gift at the end of December.

Bruce Betts: Oh my God.

Mat Kaplan: In the meantime, I hope you will accept this bar of Meteor Shower Soap that I am showing to Bruce right now. It says, "Get impact crater clean. Feel airburst fresh. Scrubs away particles of Haley's Comet." And in the ingredient list after all the legitimate ingredients, it says, "May contain material from the [inaudible 01:16:35] and or [inaudible 01:16:42]."

Bruce Betts: Wow.

Mat Kaplan: Happy anniversary.

Bruce Betts: Thank you. I am both touched and a little bit scared what actually is in that, but for you, I will consider taking a shower at some point. No promises when.

Mat Kaplan: I'm glad to hear that. So is everybody else who comes in contact with you. Our audience doesn't need to worry about you showering, but you should probably call this to a close.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody. Go out there, look out the night sky and think about 20 years of Planetary Radio. Thank you, and good night.

Mat Kaplan: That's what I'm thinking about, and 20 years of doing What's Up with the chief scientist of The Planetary Society, Dr. Bruce Betts. Bruce Betts with What's Up?, what we hope will be a regular feature here on Planetary Radio. We'll end as we begin this special 20th anniversary episode with the close of that first show. By the way, the woman you'll hear was my then 17-year old daughter, Laura. Thanks so much for joining me on this 20 year trek across the solar system and beyond. I'll be back next week with astronaut and former head of NASA's Science Mission directorate, John Grunsfeld, ad astra. Thanks for listening. Have a great week everyone.

Laura: Planetary Radio is a production of The Planetary Society, which is solely responsible for its content. Our producer is Mat Kaplan. Other contributors include Charlene Anderson, Monica Lopez, and Jennifer Vaughn. The executive producer is Dr. Louis Friedman. The opinions expressed of those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect those of the Society or this station. This edition of Planetary Radio is program number 0201 and is copyrighted by The Planetary Society. All rights are reserved. Your questions and comments are always welcome. Write to [email protected].

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth