Planetary Radio • Jun 15, 2022

Portrait of a Scientist: A Conversation with Psyche mission leader Lindy Elkins-Tanton

On This Episode

Lindy Elkins-Tanton

Foundation and Regents Professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration at ASU

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

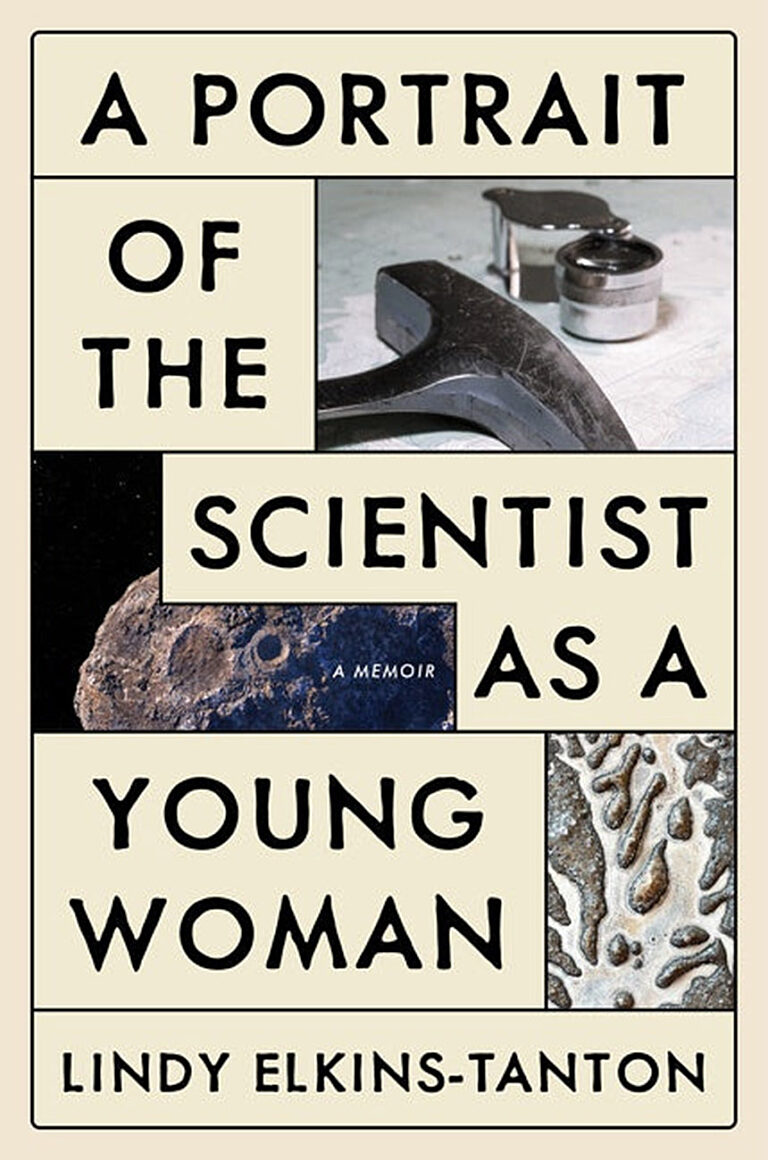

Lindy Elkins-Tanton’s wonderful new memoir is titled, “A Portrait of the Scientist as a Young Woman.” Host Mat Kaplan talks with Lindy about this sometimes harrowing, often heroic, and adventurous chronicle of her path toward leadership of the Psyche asteroid mission. This new conversation follows their brief encounter in a Jet Propulsion Lab clean room that we presented last May. Your chance to win Lindy’s book arrives in this week’s What’s Up segment with Bruce Betts.

Related Links

- Lindy Elkins-Tanton’s memoir, “A Portrait of the Scientist as a Young Woman.”

- Psyche mission

- Arizona State University School of Earth and Space Exploration

- Planetary Radio: Heavy Metal: An encounter with the Psyche spacecraft

- The Downlink

- Subscribe to the monthly Planetary Radio newsletter

Trivia Contest

This Week’s Question:

Who was the first woman to fly in space twice?

This Week’s Prize:

A copy of Lindy Elkins-Tanton’s “Portrait of the Scientist as a Young Woman.”

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, June 22 at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

What unofficial, but common, name for a type of feature on Venus sounds like it would be delicious for breakfast?

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the June 1, 2022 space trivia contest:

On the Apollo 11 goodwill messages disc, messages from the leaders of how many countries other than the USA are included?

Answer:

73 leaders of countries other than the United States added messages to the goodwill disc left on the Moon by the Apollo 11 astronauts.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: A Portrait of the Scientist as a Young Woman, this week on Planetary Radio.

Mat Kaplan: Welcome. I'm Mat Kaplan of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. With a tip of the space helmet to James Joyce, that opening line is the title of a great new memoir about the making of a scientist and leader. We last met Lindy Elkins-Tanton in our May 4 episode when I suited up for a clean room visit with the Psyche spacecraft. Lindy is principal investigator for that first ever mission to a metal asteroid. I told her at the time how much I loved her new book and how much I looked forward to talking with her about it. Stay tuned for some dramatic surprises. And you'll want to stay tuned even longer for a chance to win the book when Bruce Betts arrives with the new space trivia contest.

Mat Kaplan: Bruce also has a rare cosmic lineup for us to celebrate. Seeing the image that leads the June 10 edition of the down link, you might be forgiven for thinking of spacecraft had landed on The Little Prince's B612 asteroid. It's actually a fisheye selfie taken by that Mars exploring pioneer, Pathfinder back in 1997. Yeah, 25 years ago. Pathfinder and its Sojourner Rover are also featured on the cover of the June solstice issue of The Planetary Report, our great magazine, that you can read for free at planetary.org, just like the down link. And it's in the down link that you'll also learn about the big event plan for July 12. That's when NASA will share the first science images from the James Webb Space Telescope. My society colleagues and I can hardly wait to see what will be revealed.

Mat Kaplan: Lindy Elkins-Tanton is a Foundation and Regents Professor in Arizona State University's School of Earth and Space Exploration. She's also the vice president of the ASU Interplanetary Initiative and was elected to the National Academy of Sciences last year. Google Asteroid (8252) Elkins-Tanton, it's not the one her Psyche spacecraft will arrive at in January of 2026, if all goes well, that object is also called Psyche. Here's my new conversation with Lindy. So let's get something out of the way right away. And that is the status of your mission, Psyche, at which at this point, I guess, is really the status of the spacecraft since you're not launching for a while yet.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: That's right. We are definitely gunning to make it a launch in 2022. We did slip our launch readiness date out into September because we're having challenges with our flight software. You have to build a test bed in which you can test the flight software because you can't actually test it on the spacecraft. You can't thrust and do attitude control when the spacecraft is in a clean room on earth. And so you need a test bed. And so our test bed, it turns out, was imperfect. And suddenly we have to fix our test bed and then recheck our flight software. And of course, we can't launch until we know that the flight software's going to work. This is not where we hope to be. We hope to be clean and ready to go. But mission success is the number one priority, and the team is just doing an amazing job. And so keep your fingers crossed. We are still hoping to go in 2022.

Mat Kaplan: You said it in the book and we say it all the time, space is hard, but this is the kind of thing you run into.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: It is. It just is. And I have to tell you, building the spacecraft during COVID, that's been something else. And needless to say, you could imagine that when we wrote all of our budgets and our schedules and were selected back in 2017, we didn't have global pandemic schedule margin built in. So the fact that we even are is in good shape as we are actually just fills me with pride and gratitude for this team of people.

Mat Kaplan: And we're going to talk more about your pride in this team and how it was brought together largely by you, because that's really key to what the book builds to I think. But just one more question about the mission. How critical is your launch date? Do you have, it sounds like a good deal, more leeway than a lot of other missions?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: We have a longer launch period in 2022 than a mission normally has. It extends into October, which is great. Let's hope that is sufficient. And if it's not, we definitely can go in two years and we hope to be able to go in one year. But all those things are TBD, and we're really focusing on 2022 for now.

Mat Kaplan: All right. Let's move on to the real topic for today. I already said, outstanding book. I don't think I have ever read a memoir that does a better job of demonstrating how someone's life and lessons learned prepared them for leadership while also describing how others can take advantage of these lessons, because correct me if I'm wrong, but it seemed that was one of your purposes. There are rules, if not to live by, at least to consider in this book.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: That is so lovely of you to say. And to the extent that anyone would agree that I'm prepared for leadership, that was certainly the goal. And I hesitate to ever say that I have advice, but I have examples. Here's what I tried and here's what happened. And I hope that is really helpful to people. And that is indeed one of the purposes of the book.

Mat Kaplan: There are so many wonderful passages in the book. There is great inspiring prose. Here's an example, just two sentences. There is great beauty in the depth of knowledge humans have collected. I wish with all my heart that every person could in at least one discipline pursue and come to know through a long path traveled all that has been discovered right to the edge of human understanding. What a lovely thing to say.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: I feel that so deeply. It's the kind of magic that people who go the academic route often don't encounter personally, viscerally until they're well into their PhD. But wouldn't it be great if everyone on earth understood the limits of human knowledge, what it is to be an expert, how to decide your opinion? We grew up in a kind of a school created miasma, believing that things are known. You look in a textbook, you think it's known. You look in a textbook, you think there's no room for me in that story. But it turns out, most things that we think we know are going to be at least altered by future knowledge and the things we don't know are so outnumbered the things that we know. And I think that perspective, which I know that you have clearly with your own work changes how you see the world and humanity and the choices that we make.

Mat Kaplan: What about the title of the book? I assume you took your inspiration from James Joyce, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which is another story of how someone matures and grows into their potential.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Yes. I'm such a literary writing kind of groupie. I have to admit, I did not think of this title. It was my brilliant editor, but I really loved it when he thought of it. There's a lot less Catholic angst in my book than there is in Joyce's book. But I think the point of it also is to point out the fact that even still in the current day, most people don't immediately think of a young woman as a scientist. And so that's part of the purpose of the title as well.

Mat Kaplan: You ran into a challenge caused merely by the fact that you were a woman over and over and over, but I do now want to go back to the beginning of the book because it begins with a shock. You would think reading just the first few paragraphs that maybe this is just going to be a story of a idyllic upper middle class childhood in a rural area. And then we hear these sentences, you were unsupervised in the woods, someone repeatedly raped me. How old were you when this started?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: I was a very little girl and this went on for a limited amount of time. And by the time I was out of elementary school, it was over.

Mat Kaplan: That's a long time.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Yeah, it was a couple of years. And what can I say? Physically I survived this. And so people have been through much worse. But I think part of the reason that I brought it up is that it did cause me tremendous emotional problems. And also sadly, this is not an uncommon story. If only it was an uncommon story, more people are feeling that they can tell this story these days, but there's so many people who are still silenced. I thought it might help to have one more story that shows the damage that occurs in the ways that it can be overcome.

Mat Kaplan: It was a courageous thing to do. It was a shock, but it does make the rest of the book. It helped me appreciate much more what you faced and challenged and overcame in the rest of the book, because let's face it, yes, this is all too common. And yes, it's also all too common for the scars from an experience like this to haunt someone to the point that during the rest of their life, you would not expect to hear that they had become an accomplished academic and the leader of a mission, a billion dollar mission.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: I wondered as I wrote this book, whether it was just that the people who do attain leadership or whatever level of success they consider a success in their lives don't usually talk about this. It's overcome. It's in the past. I don't know. Of course, I don't suppose anybody really knows. But yeah, those scars stay with me to the present day. And thank goodness I was able to with some really great help get past all the ones that were really destructive to my process during my twenties.

Mat Kaplan: We have a mutual friend. You knew him far better than me, Gregg Vane at JPL, who you write about in the book. Obviously you were close to him. Maybe he was something of a mentor as well. Fascinating man, amazingly capable, and yet it wasn't until I read your book because he shared some of his early experiences with you that I learned that he had also had some major challenges as a kid.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Gregg is such an incredible person and it was lovely to see him visiting Psyche that same day, or the day before that you were visiting. This has struck me so profoundly. I don't know how common it is, but it was very easy for me to collect three of us who had quite difficult childhoods and were unbelievably calmed and comforted by the size and scale and the time, the length of time in our solar system and in our universe. And I have no profound analysis really of why this is, why it is so viscerally comforting for so many of us, but how fascinating that it was for Gregg as well.

Mat Kaplan: I flagged that quote that you mentioned from Gregg, "There's so much more out there than just us."

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: In other words, more than our little problems are.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: That's right. That's how it feels, right? It puts into perspective one's daily sufferings.

Mat Kaplan: You at least got to have some fun doing some horseback riding.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Totally, yeah. That was a lot about my childhood that was great. And I was loved by my family and I had great friends and many of whom I stay close with to the present day. And indeed, maybe my greatest comfort growing up was animals. And I just loved horseback riding. And I haven't ridden very much recently, but that love persists.

Mat Kaplan: I want to go forward a little bit. It seemed that you realized that you wanted to do something bigger. You wanted to ask really big fundamental questions. Did this set off a little bit of a shift in your plans?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: This thought really came strongly into my mind in my late twenties when I'd been working in business for a while and I was lecturing in mathematics at St. Mary's College of Maryland. What a lovely school that is by the way. What a great job to have. And I realized the incredible gift of being allowed to ask the questions that you think are most interesting and most important and pursue them. And that's a gift that is given to us in most professorships and in very few other places in life. That is part of what propelled me back to get my PhD. So I knew I couldn't have a permanent position in academia in the same way without a PhD.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. And I've skipped over there a good deal of other experience, including your private sector experience, which all came before this return to academia.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: That's right. Yeah. I worked in business for about eight years before I went back to academia, which is not the normal sequence of events, I guess.

Mat Kaplan: No, not in my experience. Jumping forward again to chapter five, which you titled, Every endeavor is a human endeavor. You were already a post-doctoral fellow when you put together a team, because there was this really puzzling issue in geology that I would love for you to tell us a little bit about. In fact, why don't you do that before we move on to talking about putting together this team as a postdoc, which was not a typical thing to do at that level from what I read and some of the challenges that you faced? But what was this that you were so curious about?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Well, two of the largest events in geologic history on the earth seem to have happened at the same time. And the first one is the End-Permian Extinction. This is the largest extinction that we have recorded in earth history. It's way back before the dinosaurs. So this one was 252 million years ago. And at that time, more than 90% of the species in oceans went extinct and more than 70% of the species on land. It was almost the end of multicellular life on earth. Now here's the part that blew my mind as a graduate student, nobody really agreed on what caused this. At that same time, we thought, although we didn't know for sure because the age dating was not accurate enough yet, the largest volcanic eruption on earth also occurred, the Siberian flood basalts. This is a kind of vulcanism that is not happening on earth right now, where fissures open and magma pours out.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: And so you might think, of course, a gigantic event like that would cause a global extinction, but actually the Siberian flood basalts were thought to be much like say some of the recent eruptions in Hawaii where they're not actually explosive and they're not pumping lots of toxic gases into the atmosphere and you can kind of walk right up and look at them and go home and you haven't died as long as you didn't do a stupid thing. And so if Siberia was like that, you would've thought it could have killed things locally, but not globally. And I just couldn't believe that we didn't really understand what caused that eruption and we didn't really understand what caused the extinction or even if they were related. And so I've been working on that during my PhD. And then when I was a postdoctoral fellow at Brown University, my great friend, Sam Bowring at MIT who we've lost in the intervening years.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: But he said to me, "One day, Lindy, you've thought an awful lot about the Siberian flood basalts and the End-Permian Extinction, why don't you try to put together a big team to actually solve this problem?" And this is just the sign of what a mentor can do for you because it had never occurred to me up to that point that I was qualified or capable or that it would be possible in any way for me to lead a project like that. But then as soon as he said it, I kind of couldn't get it out of my head. And that was the beginning.

Mat Kaplan: So you proceeded. I mean, you managed to get some support for this from the National Science Foundation and proceeded to put together a team. And I think, I mean, you must have had some exposure to the difficulties of human behavior before that. You certainly [inaudible 00:17:10], of course. But as a manager and as someone who needed to put together a team with a goal, shall we say that it was a learning experience?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Absolutely. I had already in my mind this idea that the reason that we didn't know the answer to these questions, what caused the extinction, what caused the vulcanism, were they related, was because, and I read hundreds of papers about it, it's not like no one had studied it, was that every person had gone after it from their own narrow disciplinary point of view not really combining the data sets, not putting together the big picture, because of course we're rewarded in academic science for making progress in our narrow discipline and becoming the leader and owner of our narrow discipline. And so that reward structure keeps us kind of in those silos. I went into this quite determined that we needed to bring people from all the needed disciplines to think about it together.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: And of course, I'm not the first person in science to try to do this kind of thing, but it was the first time in my life I tried to do it. And trying to figure out some tricks that would keep people from doing what I call taking their slice of the pie and rushing home with it to their lab to do what they would've done anyway and ignoring the bigger team. That's what I said about trying to do, figuring out how to make this team work better. And it was my first time really trying to blend people of many disciplines where they didn't have a huge motivation to stay blended. It was very interesting.

Mat Kaplan: And you met with a good deal of success, I think, but not entirely. I mean, there was at least one really challenging participant in this.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Yeah, there were a couple. One person that comes to mind as someone who... Well, while I was at Brown, I managed to get a little bit of seed funding from the National Science Foundation to help me start up this team to write the proposal that would be required. And I'm so grateful forever to Leonard Johnson for making that possible from the National Science Foundation. He's so visionary about trying to do bigger science. So he supported me to have this workshop. And one of the people who came to the workshop basically went home, did the ideas we discussed in the workshop by himself and never joined the team. It was fascinating because I had to become my better self in that moment and not just hate him forever for his bad behavior and recognize that it actually didn't matter because we could do it better.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: We could do it better together. We could get a better answer. And a couple of years later where we ran into each other face to face at a meeting, the first thing he says, he said to me was, "Well, I completely gave you credit and I cited all of your work," which to me was the perfect admission that he knew exactly what he'd done. So anyway, that didn't matter. We got past it. And there were people who didn't play as nice as others. One person who went through the draft of the proposal and crossed out someone else's name and wrote in his name every place that it occurred through the proposal like we were in kindergarten.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: And so there were some challenges there. And that's really what led me to think, every endeavor is a human endeavor. We can only do as well as we humans can do when we try to do it together. And so part of the trick, and I know that you have run into this in your own life too, is figuring out who plays nice. Who is actually going to bring their A game and actually care about the success of others and the greater project and not just about themselves?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. I'm a firm believer in picking people who play nice is as important as picking the people with the greatest skills and knowledge because there are plenty who have the greatest skills and knowledge who also like to get along with others.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Exactly.

Mat Kaplan: The theme also that you expressed about the value of bringing together people from different disciplines, it of course comes up all the time on this program because it's in a sense, the essence of planetary science, isn't it?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: The essence, yes. Yeah. We have to, right? I'm fond of saying that the days when you could make fundamental chemistry discoveries in your kitchen are largely over. That was a couple hundred years ago. Now we've really got to get together in groups in order to answer the largest, most important, most pressing questions in front of us.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. And big, deep space planetary science missions are another good example of that.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Absolutely.

Mat Kaplan: So the meeting of this team and the result of this team, I would guess was a necessary step toward a great adventure that you document pretty much next in the book. And that was the first of your trips to Siberia is a fascinating and thrilling section of the book.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: I made four trips actually. And yeah, no, we had a bunch of trips and I was not on every single one. One of them I missed because of my mother's terminal illness actually. And the rest of them, I was there. So I went between 2006 and 2012. And oh my gosh, I am so grateful to the universe for allowing me to have these adventures and to fantastic Russian colleagues who went so far out of their way to make it possible for us to go to these places. And so we did have not on all of these trips because people did all kinds of different things in their own expertise, but we had about 30 scientists from eight different countries working on this project. Traveling in Siberia was absolutely life changing in the most wonderful ways.

Mat Kaplan: It's as good as any section from a travel book that I have read. It reminded me of some more difficult stories of travel because it wasn't all easy. I mean, it may have been gorgeous scenery that you were seeing. And you did manage to get the results that you were or the data that you were looking for. But I think it was also another lesson in human behavior, right? I think because you saw a lot of stuff. I mean, there were things happening between senior scientists and less experienced junior scientists. And particularly with women that could really only be described as bullying. And it was a lot of it had been trained into these senior scientists.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Absolutely. It's absolutely a way of life for some people and it's not viewed as a negative thing. You just have to toughen up and get the job done. And their job is to help you toughen up. And as much as I disagree with bullying people to their breaking points, I don't personally think that is a productive practice. Pushing somebody a little bit past their what they feel like they could do in that moment can be great if it's done in the right way. And so there were these moments on these trips. There were very few of us women on the trips where that did happen, but I'm very glad to say that in general, the trips were spectacular examples of teamwork and support and patience with each other.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: You have to be so patient when you're in the field. And you have to just swallow your words and not let them out because you're going to be living with this person 24 hours a day in a super remote location. And it could, it never did for us, but there could be life and death situations. And you can't have broken your relationship to the point where you can't help each other. It actually is a little bit like space travel. You're out there and you got to get along.

Mat Kaplan: You may not have reached the level of life or death, but there certainly were big physical challenges. And I only like to think that I would've been up to it if I'd been on a trip like that. But you had to come out of something like that feeling like you had shown that you could achieve that. I mean, that there was a real physical accomplishment.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: I always felt, throughout, I just hate to even admit this, but throughout all those Siberia trips and also some big bicycle trips I took earlier in my life when I was 17, we rode, I forget 1200, 1800 miles or something like that on our bikes and I always felt like I wasn't quite up to it. I always felt like I was holding people back a bit and I was struggling. And a lot of times it was because I was a shorter legged woman next to these long-legged men. I'm not such a specimen that I can completely keep up. In retrospect, I'm much prouder of what I did than I was at the time or in the years around that time. I felt like I had just squeaked through during those trips.

Mat Kaplan: We can't leave people in suspense. What did the data you were able to gather because of these trips, what did it tell you about-

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Oh my goodness.

Mat Kaplan: Not long ago era?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: It took us about 10 years to put all the data together and we're still publishing results from this.

Mat Kaplan: Wow.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: And so the first most, it was sort of like a three-legged stool. The first leg of the stool is through the work of Sam Bowring and Seth Burgess, who've got his graduate degree with Sam. They proved that the flood basalts and the extinction happened at the same time, that the flood basalts erupted for a while and then the extinction happened. And that was necessary to show that they, to prove that the flood basalts caused the extinction, if indeed, that was... Because if it had been the other way, if the extinction happened first, we could have written it off. That was not causal, right?

Mat Kaplan: Sure.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: So first you have to show that the eruption started first. Then the second leg of the stool is to find out what kinds of gases were given off by these magnets, something that wasn't expected. So we found that there was a vast area of explosive magnetism, not just this calm effusive kind, where you can walk up and glance at it, but hook tremendous explosions that would drive toxic climate change and gases into the stratosphere where they would circle around the earth and cause global climate change instead of just local climate change. And that was also the second really critical leg of the stool. It was so exciting when we found that horrifying and exciting that these eruptions, and this is a largely work of Ben Black, who's now at Rutgers, and then Sverre Planke and Henrik Svensen in Oslo and others, of course, that the magnetism had given off enough sulfur dioxide to cause acid grains so acidic that parts of the oceans would have the acidity of lemon juice. Also, so much CO2 that the heating would've been very significant. This has been worked on by many teams.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: And then the astonishing thing that Henrik and Sverre first discovered is that when these particular rocks were baked by the heat of the magma, this particular rocks that existed in Siberia, they gave off naturally occurring halocarbons like the chlorofluorocarbons that humans make as refrigerants. And so many have been banned because they destroy the ozone layer and they're also extremely powerful greenhouse gases. So we were able to prove that these were created by mother nature at this one particular time. So that was the second leg of the stool. And then the final leg of the stool was to take all of that data about the gases and the volumes and the tempos, and put them into giant climate models to see what would've happened globally. And I think this is the best version of scientific proof that was possible to do with this great distance through time looking into the past. The excitement and the terror of this result is that the End-Permian is the closest analog to what is happening in the present day earth that we have in the geologic record.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: And it really was almost the end of multicellular life on earth at that time. And of course, a great moment of evolution immediately followed in the rise of many more kinds of life. But here on earth today, we would like to keep it comfortable for us humans. And it just underscores the importance of the work that so many are doing now.

Mat Kaplan: I'm so glad that you made that tie to the climate change challenges we face today when we have still and sadly encouraged by some who know better people who doubt the data that can be pulled from under the ground or under the ice that may only be tens of thousands of years old rather than hundreds of millions of years old.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: That's right.

Mat Kaplan: It certainly says something about the relevance of science done at what may seem impossible distance from us in time having great relevance for today, which I think we can-

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: I think that's fascinating.

Mat Kaplan: We can also see it in your mission, can't we in Psyche?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: I hope so. I mean, I believe strongly and I'm sure that you do that space exploration has vast and irreplaceable benefits to humans here on earth.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely. All right. We'll move on to another portion of your life that I think helped prepare you for where you are now. You had to deal with mistreatment harassment and worse many times, not just when you were the target of these. There was a job you took, a very high level position at an organization that you don't name in the book, and you immediately started hearing from lower level staff about an abusive manager. And you went to bat for these other individuals. The result was less than one might have hoped to get from top management. I think I can see why you called the chapter, expanding courage. Can you say something about that?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Yeah. What an adventure that was. I've been fortunate that in my adult life I've had very little harassment or bullying, but unfortunately I certainly have witnessed it happening to others as most of us have. This example that you're talking about, it was a real eye opener for me, because I think that I still held this naive childlike view that if we identified something that was absolutely unequivocally wrong, that leadership would take action to correct it. And of course, as soon as I say these words, I'm intended to say who could be so naive as to think that could be true. As we see, we know history, we look around us. People have so many different motivations for the things that they do or do not do. And this was a classic example where the person who was doing wrong also brought in a lot of money for the organization, was in a high leadership position, was also famous scientifically.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: And for those reasons, explicitly I was told was protected by our common manager. Oh my gosh. I mean, it's tempting for me to just say this is all because of my personal history, but I absolutely couldn't stand for that. I just couldn't stand for it. It made me crazy. Every day I thought to it myself. My every day was taken up with how do we fix this? I'm watching the people suffer. They're coming and asking me for help. I'm doing my best and nothing is happening. How can this be true? So I had long conversations. Well, really with everybody in my life, bless their hearts. But especially with my husband, James, and we talked about this. Well, I could put up with it as others had before me and coexist, or I could quit and go elsewhere or I could keep fighting.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: And I knew that I couldn't just coexist just because constitutionally, I wasn't capable of that. It would've eaten me up. I didn't want to quit and go elsewhere, first of all, because I loved the organization and the job, and I also would never have forgiven myself. And so I was really left not having a choice. I had to keep fighting. From a career point of view, probably not my best choice for myself. I was really quite worried that I was going to be fired and really damaged my career in a substantial way and/or never be able to make any change and still have to leave. And so it was in some senses, a really stupid decision. And in the end, though I was a much more successful even than I had thought I might be because some members of the board finally saw how important this was and that person was forced to step down. So that was a huge success. I'm really happy about that. Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: I disagree with you that it was a stupid move. I think it was a profile in courage, not to coin a phrase. I mean, you did put your job on the line, right, at that one point.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: I did, yeah.

Mat Kaplan: Person or me. That certainly was in my book, courageous.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Thank you.

Mat Kaplan: It also led to your creation of some guidelines or rules, there are five of them, you list them. And I think this is a good example of where you try to in this book to share some of the lessons that you picked up. I don't expect you to go through the five now. In fact, that's a good incentive for people to pick up the book and read it. But it's one example of where you do this in the book where you do try to crystallize what you've learned I assume in the hope that others might be saved from making some of the same, I won't say mistakes, getting some of the same challenges or dealing with them better when they inevitably come up.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Yeah, that's right. I can't help, but be that metacognitive person all the time. What do I do with this information? What have I learned? How could I have done it better? And certainly I learned that to create change in an organization, you need both the determination of the people who make up the organization and the determination of the people who leave the organization. Both of these groups are needed to create change. Who knows more about this than the great Ruth Bader Ginsburg. And she made the point, I think very correctly that you have to try to create change in a way that makes other people want to join you in making change. And I don't know that I did the best job I could have done in this circumstance. I think I've gotten better at that over time.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: But I can't stress how important that is because for many of us who are coming at it, say I'm a staff member somewhere, I don't have the leadership capacity. I don't have the necessarily that kind of authority to make change, but I desperately want change. Mostly, I would come in with a sense of rage. I'd sit down with a leader and I would be angry and I would be accusatory. Those would be the feelings in my heart. Those are not emotions that bring out the best in the person you're talking to. And so attempting to make change in a way that others want to join you is such a hard rule to follow, but I think it's really important.

Mat Kaplan: And again, it comes up as we get closer now to dealing with how this mission, Psyche, came about. Much more of my conversation with Lindy Elkins-Tanton is just ahead here on Planetary Radio. By the way, if you like what you hear, please give us a review in Apple Podcasts.

Bruce Betts: Hi, it's Bruce. Will you help defend earth? The Planetary Society is advancing the global endeavor to protect our world from an asteroid impact. It's the one large scale natural disaster we can prevent, but we're not ready yet. Please become a planetary defender and power our crucial work. You can double your support for planetary defense when you make a gift today. When you do, a generous member of the society will match your gift up to a total of $15,000. It's a great opportunity to make a difference. Visit planetary.org/defendearth. Thanks.

Mat Kaplan: You refer at one point to what you call the ego economy. What is that about?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: This is something that I've even written about outside the book as well in this essay I wrote a couple of years ago that we call, Is it Time to Say Goodbye to Our Heroes? Back even in 18th century in Germany and in some other places in Europe where universities were really developing, it became obvious to administrators that a sense of charisma and fame in a professor really added to the prestige of the university and brought in lots more students. And so we began to develop an ego economy, because if you did better and were more valuable, the more charismatic and famous that you were, then people began to spend some time trying to become more charismatic and famous. Even if it wasn't a conscious calculation, it became this way that people would see success in their senior professors, not the ones who were super quiet, sat by themselves in their offices, working on the whiteboard. But instead, the people who are talking head on the news or who advised the government.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: And the way you get there is by parlaying your knowledge and your visibility. And you do get into this ego economy. I see some of the uses of it. And it would be disingenuous if I didn't say being able to talk to you about my book is a part of this economy, right? I hope that I'm doing it for the right reasons is really the goal of this. Instead of just feeling like I, myself, am a more important person, could we always be thinking about what can we do in service of whatever we're serving: society, the future of humanity, the breadth of human knowledge? Keeping your eye on the thing that actually matters instead of just yourself, because what happens when we're just dealing in the ego economy is the people who work with us suffer because one of the ways that we are more famous is if the people around us are less famous. And so it makes it really difficult to be a graduate student in that economy or any other junior member of the academic pyramid.

Mat Kaplan: And I would expand that maybe to include it makes it more difficult just to get the very best work out of people who may be lower on a team. And so now, I mean, maybe we are coming to talking about Psyche. You came up with a list of standards in this case that I think you wanted to meet as a team leader. And I'm very impressed by them. Almost worth bringing them up, except that I was reading this as an ebook. And so I don't know what page they are. I know what location number they are on my iPad. Putting them into effect seems to have taken you back to how you also believe the nature of education should change, from the classic sage on the stage, the professor who might naturally develop a certain sense of entitlement and superiority.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: That is really true in education. And sometimes it's great fun to listen to a lecture by someone with that kind of charisma and self-confidence, but that doesn't mean it's necessarily the best way to learn things.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: The way a person is successful in your average school, K through 12 and in college is that they are willing to sit passively and receive information and then give it back on an exam in an uncritical way. That is the way to get A-pluses. However, I would argue that all of those skills are not very useful later in life. And in fact, they're the opposite of the skills you actually need to make positive change in our world. We need to have a sense of self agency that we can decide and find the information we need to make the best decisions, also that we can recognize unsolved problems and go after solving them.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: And we can criticize in a constructive and thoughtful way the information that comes to us. Those are all the skills that we need to be more effective as humans. And so maybe it comes from having spent parts of my life feeling powerless, as I think most every human has. This is not necessarily a gendered issue. That sense of powerlessness that we each have had at some point in our lives makes me want to give everyone in the world a sense of agency, that they have the power to see something that needs to be solved around them and to solve it. And so that is really my motivating vision that makes me want to change education and go through these experiments we're going through. And the way that I've tried to influence the team and all of these things I'm trying are just little partial successes, failures, successes, up and down on that scale, but trying, all the time trying.

Mat Kaplan: It's always a journey, right?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: So this is a whole section of the book, playing, experimenting with education and some practical exercises that you did that caused enormous enthusiasm and excitement. Probably not something we have a great deal of time to talk about now, but I thought you might at least want to mention one of the results of this. And that's something that you've created with some colleagues called Beagle Learning.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Yeah. We have a small tech company called Beagle Learning. And we've built a software platform that allows you to do inquiry education, where the students leave the questions and do their own research online, even asynchronously online. It's been very successful. And we use it among many other things at Arizona State University in the Interplanetary Initiative. We created a new undergraduate degree called Technological Leadership. You can get a bachelor of science in three years and you learn how to identify and solve problems, which I think is the major skill that people need going forward into life and work.

Mat Kaplan: That's the major I should have had. Boy, I wish it had been around million years ago. All right. So you learn, you practice, you lead, and as a result, you find yourself... Well, no, you put yourself in the lead of creation of a proposal for this mission to a kind of asteroid that has never been visited before. You pull together this tremendous team. And the first proposal, the step one proposal is coming together, and you learned you have cancer.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Yeah. Geez! It was unbelievable.

Mat Kaplan: Were you tempted once you got into this and learned what it was going to take and what you had to go through to deal with it? I mean, were you ever tempted to push aside this mission, hand it off, or maybe also your new job at Arizona State University?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Yeah. I wasn't and I don't think that this speaks totally to my complete sanity because it really wasn't. I came into this new job to be the Director of the School of Earth and Space Exploration at Arizona State University. I moved from Washington, DC and Boston out to Arizona. And big school, about 350 people on payroll. We're in 10 different buildings. By the time I stepped out of the directorship, our research volume was about $65 million a year. So it was a big endeavor. And six weeks after I arrived, I learned I had ovarian cancer. And I had it just this ovarian cysts, which is very common thing, but mine kind of was a bit troublesome. So we decided just take it out and did that, not a difficult surgery. I was at home recovering when the doctor called me and said, "Actually we found cancer in your cyst and you have to come back for another surgery tomorrow."

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: I forget, like immediately. I was already just recuperating from abdominal surgery. I had to go straight back in. And I thought, okay, we can get past this, and how serious this is. And luckily it was very early stage. So I was super lucky. It was the great doctors at Mayo who've caught it for me because otherwise that would've been it eventually. And so at that moment, I was still completely focused on the great new job and writing the proposal. And I'm going to get over the surgery and I'll be all better. What I didn't anticipate was how hard chemotherapy was going to be. At that moment, we weren't even confident I needed chemotherapy. In the end, we decided I would. Everybody has different reactions and there are many kinds of chemotherapy. And I had a hard time with mine. Long story short, I was a mess physically.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: So I should have thought, could I step down from this job or at least go on hiatus? Or could I just hand over the proposal to someone else? But in the end, the thing I really wanted to just not do was the chemotherapy and worry about the cancer because what I really cared about, what motivated me every day was the job and the proposal. And so my unbelievably lovely family, especially my husband, James who cooked for me every day and even drove me to work to let me keep doing this thing that was so emotionally motivating for me. I mean, he would've been so within his rights to say, okay, stop it. Just to him and rest, it always so much easier on both of us. But instead he would drive me to work and he would let me pursue this passion, knowing that it was what got me up and got me going every day.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, it was part of your therapy.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: It was totally a part of my therapy. And so thank God for the proposal and the job. And thank God for my family and friends.

Mat Kaplan: And you had this tremendous team that you had put together too to carry on as you did the best you could, resulting eventually in this 218 page step one document, which was obviously pretty successful considering where you are now. How do you feel as you look back on that document today?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: I'm really proud of the work that we did. And yeah, I got to pick on a higher level kind of our partners and a bunch of our team members. And then within each partner they would choose teams. And I would always talk with them about what we were trying to do to create teams where the junior people could speak up and tell us about issues and that everyone's voice would be heard. And it began to pull in better and better people. And that step one proposal was beautiful. And we all loved it and we celebrated it. Different team members had different amounts of faith. But I think on the whole, we did not expect to win. You don't expect to win the first time through. There were 28 proposals competing. And then we found out we were one of five selected to go on. And boy, that was a great moment. That was like a giant birthday that I never even knew I had coming. That was great.

Mat Kaplan: There were other challenges ahead. Before I get to an anecdote about one of those, I think it's at the end of that chapter, will you talk about the need for meaning in your life that it's not enough to be a leaf, as in a leaf on a tree or a leaf flying through the air? Do I have that right? What did you mean by that?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Well, I think that with the challenges that are facing humanity, of which there are many, take your pick, whatever is your personal favorite challenges. Is it pandemics? Is it climate change? Is it the economy? Is it poverty? There are so many things we need to do, to do better. I think it's incumbent upon each of us to think with the gifts that I've been given in my life, what can I do to be of greater value? And so that's something that weirdly my husband and son and I have talked about for many years. We talk about it all the time. What would be the best next step where I could make a positive difference, not just to grow on that limb, but to plant the orchard?

Mat Kaplan: That was just a brief detour back to the mission.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: The mission.

Mat Kaplan: You're one of five. And I think it says a lot that these five: Veritas, DAVINCI+, Lucy, NeoCam, and your mission, Psyche, they would all eventually be selected for development by NASA to go to space. I think it says something about the competition that you were up against. You have this wonderful story of how you prepared for, boy, maybe it may beat Siberia as the most dramatic episode in the book, the presentation that you and your team needed to make in person that could really make or break the mission and the preparations that you made for it, which are just mind boggling. I mean, just one example, you had the chairs in the room oiled.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Yeah. This was like a Hollywood super production. It was for many of us, we commented on this, one of the most dramatic, if not the most dramatic episodes of our working lives. All of us moved to Palo Alto to be there next to Maxar a week ahead. And we get encoded email with the questions we need to answer.

Mat Kaplan: Maxar was your private sector partner.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Thank you, yes.

Mat Kaplan: You were actually basing the spacecraft on their bus that they used to build lower orbit satellites.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: So important, yes. Yeah. So Maxar, at the time Space Systems/Loral, we chose them for our industry partner for the Psyche mission way back I think in the end of 2013, because we could use their smallest regular production model satellite bus and a solar electric power system at a huge cost savings to having something built bespoke from scratch. And they've been a fantastic partner to us, but they had not yet ever been a prime with NASA on a deep space mission. And so we needed to show the review panel that they really deserved this. And so we held the site visit at their unbelievable manufacturing facility in Palo Alto with the world's... It's not the world's gigantic, most gigantic, but to me it was the world's most gigantic high bay. Just filled with satellites all being built one after the next, because we wanted the review panel to see what this company could do.

Mat Kaplan: I have to ask you to tell this anecdote about what happened during this meeting, when your plane host, you have key participants on the mission team arrayed around you. You had done everything you could to prepare. So you went into it I think feeling fairly confident, but then there were some curve balls thrown. And one of those you had to sort of, what do they call it on those game shows where somebody has to make a call out to a friend? You had-

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Phone a friend.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. You had to bring in somebody who we know very well at The Planetary Society, Jim Bell, your colleague at ASU. The guy that I think even when you and I were in the clean room together, where I called the Ansel Adams of planetary photography or Mars photography. You had to bring in Jim to respond to this. So could you tell that story briefly?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: We of course spent literally years thinking about what were our weak points and how do we make them stronger and how are people going to receive this proposal. And we were certain that the review panel was going to be filled with questions about our Gamma-Ray and Neutron Spectrometer, this gorgeous instrument that applied physics lab has built for the mission. And so David Lawrence, the lead of that instrument had a suit so he could present and he was showed up early and he is all ready. And what we were not expecting was that instead almost all the questions would come in about the imagers, which Jim Bell leads and the magnetometers led by Ben Weiss. And so we had to call them when the questions came in and said, "You need to get here right away. You need to get here early. You need to have your suit because you're going to be presenting."

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: And so Ben even had to ask his wife, fabulous scientist, Tanja Bosak to FedEx his suit out. They were not ready. And so there's Jim Bell suddenly presenting to the team, to the review panel and big room full of a million people on well-oiled chairs. And he was kind of under attack from one of the review panel people who had a lot of really pointed questions for him. Not all of those questions even made perfect sense. Some of them were great questions, some of them not so much. And we were nervous about how Jim was going to be able to handle this in real time. And he spent a lot of time just walking back and forth thoughtfully asking for the question to be restated, handling it in the most professional and amazing way, and getting through that part of the review. But that was a moment where I think everyone's hair was standing on end. That's quite a moment.

Mat Kaplan: Tell me about that day when you expected the call to come from NASA, but you didn't know which way it would go.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Oh my goodness. My husband and I, and often our son and his wife, Liz spend our Christmas holiday up in a little house in Western Massachusetts. And so that's where I was in 2017, Christmas 2016, beginning of 2017. We got the word that NASA was going to be calling and telling people who won and who lost. And I had to tell them that in the house where we were up in Massachusetts, I don't really get cell phone coverage and we have a landline, but no answering machine. So I had carefully arranged that they would call on the landline and we had a time and a date. I knew exactly when they were going to call me and say yes or no. So I spent sort of a week in therapy with James preparing to be told no, so that I would be okay with it and life would go on.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: And I felt so much responsibility for everybody. And so I slept really well the night before. And then I was awakened by my cell phone ringing early the next morning. And I could hear it was Thomas Zurbuchen from NASA on the other end. And all I could say was, "Call in the landline. Call in the landline" because we'd get cut off. And then he would call back, "Call in the landline." I think it took like two or three times before he understood he had to call in the landline. And he'd wakened me. And it was a couple hours before I was expecting a call. And for whatever blessed reason I was sound asleep. And he could tell, I couldn't. You can't immediately clear your voice and sound alert. And so it was super embarrassing in many ways, but then as soon as he could speak clearly, he said, "I think I've awakened you, but I think you're going to be glad." And then I knew that we'd won.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely marvelous. You finished the book or very nearly the end of the book back in the room where you and I last met, all bundled up to protect that spacecraft, which was sitting right in front of us and was much bigger than I expected it to be.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: It's huge, I know.

Mat Kaplan: And so now you're at the Cape. You're going to be ready for launch, resolve those software problems, right? When do we reach this fascinating object out there, this asteroid like nothing else that has ever been visited?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Well, launching in 2022 gets us there 3.4 years. And then we will go into orbit around this amazing asteroid. And we don't really know what it is. All of our data from earth says that it's largely made of metal. It'll be the first metallic surface that humans will ever see or investigate. And the thing I especially want all the people kind enough to listen to us to know is that Jim Bell has led the development of a pipeline that will put the images from the cameras out on the internet within a half hour of our receipt. We're not going to edit them. We're not going to censor them. We want everyone in the world to share in the wonder of exploring a new kind of body all at the same time.

Mat Kaplan: Wonderful. And there's another thing that makes us sort of a mission for the people and it's not something we talked about in our previous conversation. You have an art program connected to [inaudible 00:56:34]. Tell us about it.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: We do. One of the things that Thomas Zurbuchen said to me on that very first phone call was we want to redo the way student collaborations are done on these missions and we want to do much more bold things. And so I was like, "Yes, I'm up for this." So the great and the good Cassie Bowman, who's a research professor here at Arizona State University and PhD in education, she and I worked out a menu of 10 different programs that we could run with Psyche mission. And we talked about them extensively at NASA headquarters, especially with Sarah Noble, who's our mission scientist at headquarters and the whole team there and worked out which ones to do. And one of the ones we selected is called Psyche Inspired. It's so close to my heart to bring more art into the science and the engineering, because the truth and you know this so well, is that no matter what you do for your vocation, your avocation in this world, there's a place for you in space exploration.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: People tend to think it's just astronauts and engineers, but it's everyone. And one of the groups we need most of all is artists. So every year we run a competition for undergraduates and we choose 16 artists from any major and work in any genre of art. And they become our interns for the year. And they're each funded to create four original works of art. You can see them all online. You can listen to music. You can read poetry. You can see the artworks. You can look at people make baked goods. They make jewelry. They're marching band competitions. Anything you can imagine, we have someone who's done this. And we're so proud of this program.

Mat Kaplan: I think it says a lot about your approach, not just to this mission, but to life. I can only say that it is captured beautifully in this book, which I highly recommend. Once again, the book is A Portrait of the Scientist as a Young Woman. It is published by William Morrow. David Brown, there's a blurb from that author as well. He called it "One of the finest scientific memoirs ever written." I am inclined to agree.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Thank you. You've made my day. Thank you so much. I really appreciate it.

Mat Kaplan: I got just one more question and maybe it's the most important one. Is your favorite restaurant still this place called Elmer's Store in Ashfield, Massachusetts?

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: Oh, Elmer's Store. Elmer's Store is under new management and it's really quite lovely and I recommend it highly, but it's not quite the same place where we had our formative Eggs Benedict breakfast back in the day. What a great place it is though. Way out in Nashville.

Mat Kaplan: I'll make a stop next time. I'm in the neighborhood. Thank you, Lindy. This has absolutely been a delight.

Lindy Elkins-Tanton: I appreciate your time and thought so much, Mat. Thanks so much.

Mat Kaplan: It's time for What's Up on Planetary Radio. Here's the chief scientist of The Planetary Society, it's Bruce Betts. Welcome once again.

Bruce Betts: Thank you, Mat. Welcome to you.

Mat Kaplan: You know what? I wasn't going to mention it because we're not going to give it away till next week, but you recognize this, don't you?

Bruce Betts: I sure do, Mat. He's showing me on the video a picture of my newest book.

Mat Kaplan: Solar System Reference for Teens: A Fascinating Guide to Our Planets, Moons, Space Programs, and More. Yeah, it's about to come out. It's already out on Kindle, right?

Bruce Betts: Yes.

Mat Kaplan: And maybe probably is from other people as an ebook. Fair mentioned to others as well. But anyway, we'll have more to say about it next week when we give away a copy. What would you like to say this week about the sky?

Bruce Betts: I'd like to return to that thing and keep returning to, because it's so cool, which is the pre-dawn east. Pre-dawn east has all five of the planets you can see with just your eyes all lined up in a beautiful line going from low down on the horizon up to upwards. They're even in order from the sun to make it even more exciting. So lowest down is bright Mercury. Up higher than that is super bright Venus. Then up to, well, if you look down at your feet, you'll see Earth. And then if you look then up to the upper right, you'll see reddish Mars, and then bright Jupiter and yellowish Saturn all strung out. And we get the moon joining during this timeframe. So on this June 17th, the moon will be hanging out at the upper end by Saturn, and over this the 11 days or so after that, it'll keep moving down till it's hanging out near Mercury on the 28th, and mercury will be quite low.

Mat Kaplan: I think it's so cool that they're all in order.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. It took me a while to arrange that.

Mat Kaplan: Good work.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. And it's been I think 20 years since they played this game and being in order in a line. I don't know.

Mat Kaplan: Extremely cool.

Bruce Betts: All right. Let us move on to this weekend space history. It was the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova this week in 1963. And this week, 20 years later, the first American in space, Sally Ride.

Mat Kaplan: American woman in space.

Bruce Betts: Eh, picky. Yes, I forgot a key word. Sorry about that. Thank you for catching that.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, yeah. Sally Ride, who is mentioned very prominently plays quite a role in Lori Garver's new book, which we will be talking about on this show in a couple of weeks.

Bruce Betts: We move on to Random Space Fact.

Mat Kaplan: Hey, that K-pop group still wants to talk to you.

Bruce Betts: Nice. It's not Nine Muses, is it?

Mat Kaplan: No, it's only eight.

Bruce Betts: It's about all I knew about K-pop and they're all women. So maybe if BTS is looking, I'm so hip. I use the word hip. Let us get to the cool fact. We're talking Psyche mission. And from NASA's Psyche mission website, not so random today, the size of the spacecraft with its solar panels, they say picture a smart car in the middle of a singles tennis court. The solar panels are huge. They are almost as big as the singles tennis court. And the smart car represents the spacecraft in the middle of all that.

Mat Kaplan: They are huge.

Bruce Betts: You've seen that spacecraft.

Mat Kaplan: I did. They no longer had one of the solar wings deployed. You can see pictures of this on the website. They didn't have room in that huge JPL clean room to unfold both of them at the same time. That's how big it is.

Bruce Betts: That's a big clean room with some big solar cells. Oh wait, they're not solar cells. They're solar cells. They're solar panels, I think I heard squeaking from the dog toy that was correcting me.

Mat Kaplan: Let's go onto the contest.

Bruce Betts: I pointed out and then asked you a question on the Apollo 11 goodwill messages disc left on the moon. This was a disc with a bunch of messages from heads of state, et cetera. According to NASA at the time, messages from the leaders of how many countries other than the US are included on that disc that was left on the moon? How do we do map?

Mat Kaplan: Got a good response to this one. I think it took off in people's imaginations, just imagining this little disc sitting up there on the moon waiting for somebody to come by and pocket it, I suppose. I hope not. Here's the answer provided as we often get it from our poet laureate, Dave Fairchild in Kansas. NASA took a small white pouch and launched it to the moon. And when the Eagle landed there, they founded opportune to drop the disc of silicon from countries here on earth that leaders count them seven, three had signed for what it's worth. 73.

Bruce Betts: 73 leaders of countries other than US sent messages along.

Mat Kaplan: Here's our winner. He's a past winner. It took a year and a half for his name to come up again. But congratulations, Hudson Ansley who had that magic number 73. Hudson, congrats again. We're going to send you a rubber asteroid, a Planetary Society Kick Asteroid, rubber asteroid. Dave Fairchild added that 116 nations were contacted, but only 73 responded in time to be engraved and carried along by Buzz and Neil. Cody Rockswold in Florida, Russia or as it was known then the USSR was not one of them. No need to be a sore loser on the race to advance all humankind, says Cody. Sam Lee in Washington, 71 if Estonia and Latvia are excluded. They of course were closely affiliated with the USSR at that time. 71, if messages not attributed to specific leaders are excluded, Thailand and the Maldives. Mel Powell in California, one country is now led by the son of the original contributor. Can you guess who?

Bruce Betts: Kaplan land.

Mat Kaplan: You're close. You're very close. Except it starts with the C, Canada. It was Pierre Trudeau. Now of course led by Justin Trudeau. Claude [inaudible 01:06:03] mentioned something you told me as well. Four US Presidents contributed to this medallion, Eisenhower, Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Baines Johnson and Richard Nixon, who had the honor of actually being president at the time. And finally this from Edwin King, who is a UK resident, citizen himself, Elizabeth II is the only signatory who is still in the job she held when this was done. In 1969, she was still queen of 15 countries, but she only signed for the UK. And we just, all of us at The Planetary Society, we wish Liz a happy 70th anniversary on the throne.

Bruce Betts: You're on a Liz basis with her.

Mat Kaplan: I was just there. I was at Imperial College London.

Bruce Betts: I did not understand quite why you were there apparently. That's really neato. It's pretty keen. Well, thank you to the listeners. I was aware of some of those complexities, but not all of them. It did make fascinating reading to look at who sign, who provided quotes. And because it was exactly because there is this confusion, I said how many it was according to NASA at the time, their statement of 73, because you could interpret things differently.

Mat Kaplan: I think we're ready to move along.

Bruce Betts: This one's straightforward. I was surprised that as far as I can tell, I've never asked this, who was the first woman to fly in space twice? Go to planetary.org/radiocontest.

Mat Kaplan: Okay. You have until the 22nd, June 22nd at 8:00 AM Pacific time to get us this one. And can you guess the prize? It's a copy of A Portrait of the Scientist as a Young Woman published by William Morrow. That terrific memoir by today's guest, Lindy Elkins-Tanton. And that can be yours if you're chosen by random.org and come up with the right answer for Bruce when we get together again next time. We're done.

Bruce Betts: Very cool. All right. Everybody go out there. Look up in the night sky and think about what your favorite dog squeaky toy is or would be or could be or you want it to be. Thank you and goodnight.

Mat Kaplan: Does this mean I have to leave the squeaky toy noise in the show in the segment, maybe-

Bruce Betts: No, I think it's flexible. It depends on how it works out. If you include it, then it's connected. And if you don't include it, it seems like I've done my job to be random.

Mat Kaplan: I'm not sure what you're... Are you saying the squeaky toy is flexible? That's good to know, of course.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. It's okay. Gracie will get you a squeaky toy soon.

Mat Kaplan: And by the way, we won't have that winner for two weeks, obviously, because that's how it works around here, where we do What's Up every week with the Chief Scientist of The Planetary Society and his squeaky dogs, Bruce Betts. Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California and it's made possible by its steely-eyed members. We've got an ironclad offer for you at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Rae Paoletta are our associate producers. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. Ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth