Planetary Radio • Dec 29, 2021

A good year for space: Planetary Society all-stars review 2021

On This Episode

Bill Nye

Chief Executive Officer for The Planetary Society

Casey Dreier

Chief of Space Policy for The Planetary Society

Kate Howells

Public Education Specialist for The Planetary Society

Rae Paoletta

Director of Content & Engagement for The Planetary Society

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan and six Planetary Society colleagues review a year full of accomplishments, firsts and exciting discoveries. Society CEO Bill Nye opens the show with a celebration of the James Webb Space Telescope’s launch. Next is a round robin discussion with Jason Davis, Casey Dreier, Kate Howells, and Rae Paoletta. We close with Bruce Betts’ recap of the LightSail 2 mission right after he offers a new What’s Up space trivia contest.

Related Links

- The Planetary Report®: The Year in Pictures: 2021 in Perfect Focus

- James Webb Space Telescope, the world's next great space observatory

- Every mission to Mars, ever

- LightSail, a Planetary Society solar sail spacecraft

- The Downlink

- Subscribe to the monthly Planetary Radio newsletter

Trivia Contest

This Week’s Question:

How many deep space launches were there in all of 2021? (Launches, not spacecraft!)

This Week’s Prize:

A 2022 International Space Station wall calendar.

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, January 5 at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

Pluto was the first trans-Neptunian object discovered. Not counting Pluto’s moon Charon, when was the second trans-Neptunian object discovered? What is it now named?

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the Dec. 15, 2021 space trivia contest:

Who do we have to thank for suggesting the planet name “Uranus?”

Answer:

We can thank German astronomer Johann Bode for suggesting that the planet Herschel wanted to call George be named Uranus.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: Looking back over a great year for space exploration, this week on Planetary Radio. Welcome. I'm Mat Kaplan of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond.

Mat Kaplan: If you've been in deep cryogenic hibernation all year, well, you might be thankful. You missed much of what's happened here on Earth, but that is not true for the world of space science, development and exploration. In fact, space has been one of 2021's great success stories.

Mat Kaplan: We'll tell that story as six of my Planetary Society colleagues me for our annual review beginning with Society CEO, Bill Nye. At the other end of the show waits Bruce Betts with another great What's Up review of the night sky, a random space fact this week in space history and a new space trivia contest, of course.

Mat Kaplan: I can always recommend our free weekly newsletter, The Downlink. But this week, I'll direct you first to the latest issue of our wonderful quarterly magazine, The Planetary Report. Why? Because it does what we can't do on the radio or in a podcast. It proudly displays our favorite space images from 2021, along with a great beginner's guide to night sky photography.

Mat Kaplan: There's more, but my favorite feature is an interview with my first boss at the Society. Charlene Anderson was also the first person hired by our three founders. She created with them The Planetary Report and served for many years as our associate director. Our members received the printed version, but the free digital addition of The Planetary Report is available to all at planetary.org/planetary-report.

Mat Kaplan: Bill, happy New Year to you and happy new era of astronomy. I hope as that big new telescope unfolds, I really wanted to get you on the show, not just to help us close out the year, but to help us celebrate the beginning of this new mission of discovery, the James Webb Space Telescope.

Bill Nye: It's fantastic, everybody. Hearken to our founder at The Planetary Society, one of our founders, Bruce Murray, he talked all the time about the so-called unknown horizon. You might say, "What does James Webb going to discover?" Well, it's going to look at light coming from the most distant reaches of the universe that we know of. It's a time machine looking back in time, and these are wonderful things. It's going to fill in paragraphs in the story of our solar system.

Bill Nye: These are all wonderful astronomical terms of phrase, but it's ultimately, "What are you all going to find with this telescope?" We don't know. That's why we built it, to see what's out there. It really is an unknown thing, but it is the next logical step in cosmology or cosmological exploration in astrophysics and looking farther and deeper into the past.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you. I suspect in the conversation I'm about to have with a bunch of our colleagues that we're going to talk about what a great year it has been for planetary science. And if you would like to address that, because I think it's also been a good year for The Planetary Society.

Bill Nye: Well, we've had a great year at the Society, even though there's this doggone pandemic. We've grown. Thank you out there for your support of The Planetary Society. We have at last a microphone on Mars, and that's from 20 plus years of work.

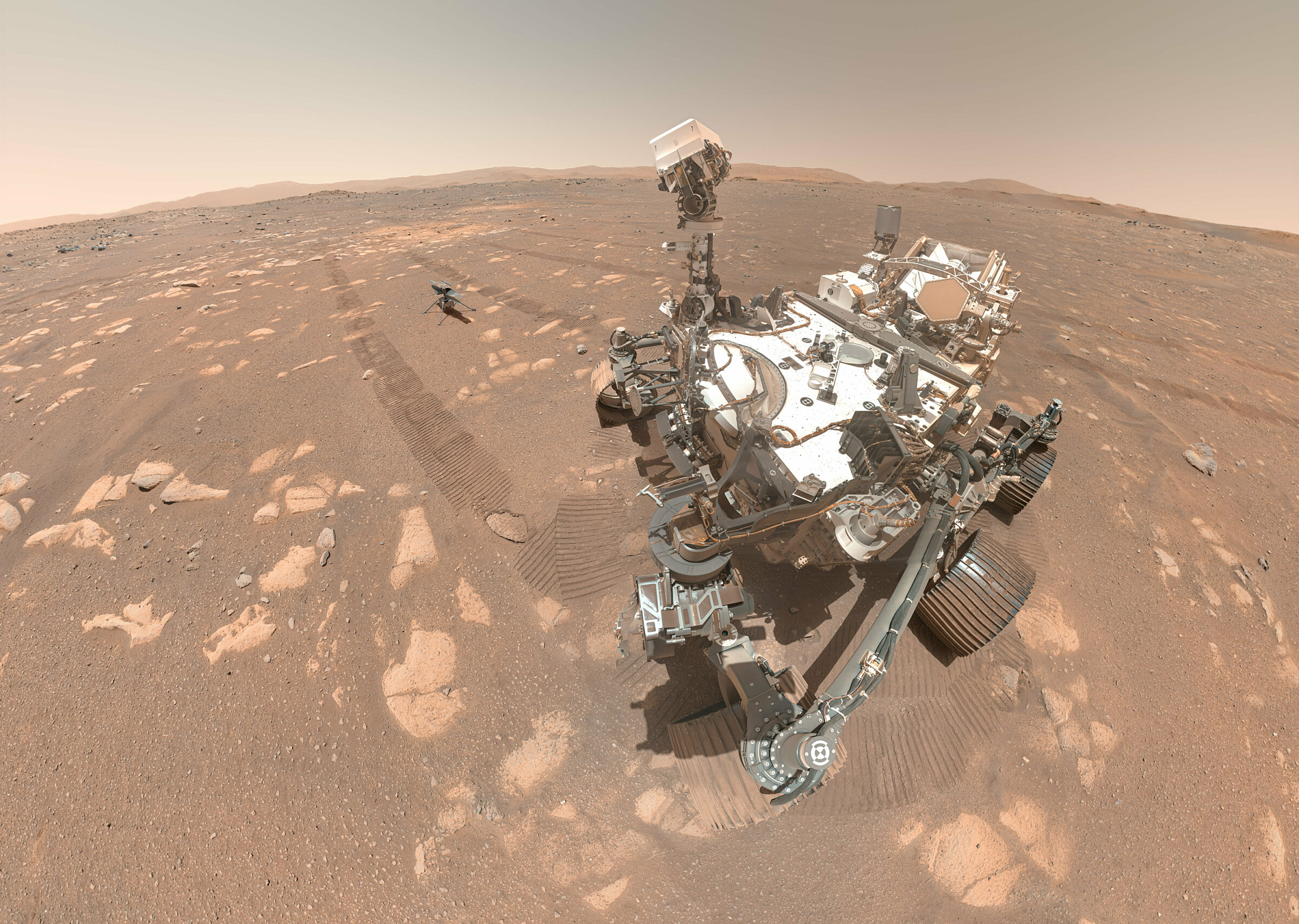

Bill Nye: I was a member when the Mars microphone was proposed in the 1980s. And then it got put on the Mars Polar Lander, which became the Mars crash into the surface of martian south polar. There was already a microphone on Mars. Unfortunate in 1999. Curiosity Rover is still doing amazing stuff. The Perseverance Rover is doing amazing things.

Bill Nye: The Ingenuity Helicopter, everybody. We all might take it for granted. It's been the holidays, gift giving season. Many of you received a drone. You got a drone as a gift. And now, you're taking pictures of your neighborhood from the sky. And you say, "Oh, this is great. This has all worked out."

Bill Nye: Well on Mars, there's no air. To get the rotors to support the weight of this extremely lightweight spacecraft in very, very thin air, it's got to run at like mach 0.6. It's got to be just whirring all the time, and it works. The thing takes extraordinary pictures.

Bill Nye: You talk to any geologist. First of all, they want to know what the rocks look like. They want to know what's inside the rock and they also want to know where to go. They want what they call mobility. They want to be able to go from where they are to where they see a cool or interesting set of rocks to go examine them.

Bill Nye: And so, everybody, it is very reasonable. I am not guaranteeing it, but it's very reasonable that in the next decade, we'll have samples back from Mars. So, in the next decade and a half, somebody will have found evidence of life on Mars. Or found a rock with fossilized, Martian pond scum. This will change everybody's view of what it means to be a living thing. The world will change. It's a very exciting time, and this year has been an exciting time in space exploration.

Bill Nye: Meanwhile, Juno spacecraft out of Jupiter is finding new amazing stuff about what goes on in the middle, the core of Jupiter. You would say, "Well, how does this affect me?" Well, people have wondered, "Is there such a thing as metallic hydrogen in large quantities?" And by that, I mean the size of the Earth's moon. What does that mean? How does that stuff behave? In other words, it's not like a metal that you and I might be familiar with. Maybe it has this other extraordinary properties, and then maybe ... I'm just making this up, but maybe it will lead to fusion here on Earth, because we'll understand the properties of hydrogen and protons that much better.

Bill Nye: You just don't know what you're going to find. And, for sure, the Europa Clipper is on the books. That's going to fly to Europa, the moon of Jupiter with twice as much seawater as the earth. Who knows what we're going to find there. Are there living things like the deep ocean vents here on Earth? Whoa, dude.

Bill Nye: Anyway, these are extraordinary, but not out of the question ideas that are worth pursuing. And I remind everybody, the cost of planetary missions is so low compared to all the other stuff we spend our intellect and treasure on. Spend intellect. Apply our intellect and spend our treasure on.

Bill Nye: You guys, my listeners, Mat's listeners, thank you for your support. It's been an extraordinary year. And if you're listening and you're enjoying this podcast and you're, for some reason, not a member of The Planetary Society, well, get on board people, because we give you access to the people who make the decisions. We had another great year of engaging the public with members of the US Congress and Senate.

Bill Nye: By doing it virtually, we had more people from more states engaged in a sense more directly than actually being there the way we were a couple years ago. And when the pandemic resolves, we will be back. By that, I mean, we'll be back in the City of Washington, DC, and we will go from office to office, and really tell our representatives what we are interested. It's a big doggone deal, everybody. It's been a big year, Mat. Back to you, as they say.

Mat Kaplan: It has been a terrific year. I am thrilled to have spent it with you and all of our colleagues, Bill. And I look forward to another turnaround the sun. Maybe we'll have a few, and to that great moment when we discover that we answer that second of your questions and discover that we're not alone.

Bill Nye: So everybody, if you're out there, these are the two questions that Bruce Murray used to ... And Lou Friedman. "Are we alone in the universe? And where did we come from?" To answer those questions, you've got to explore space.

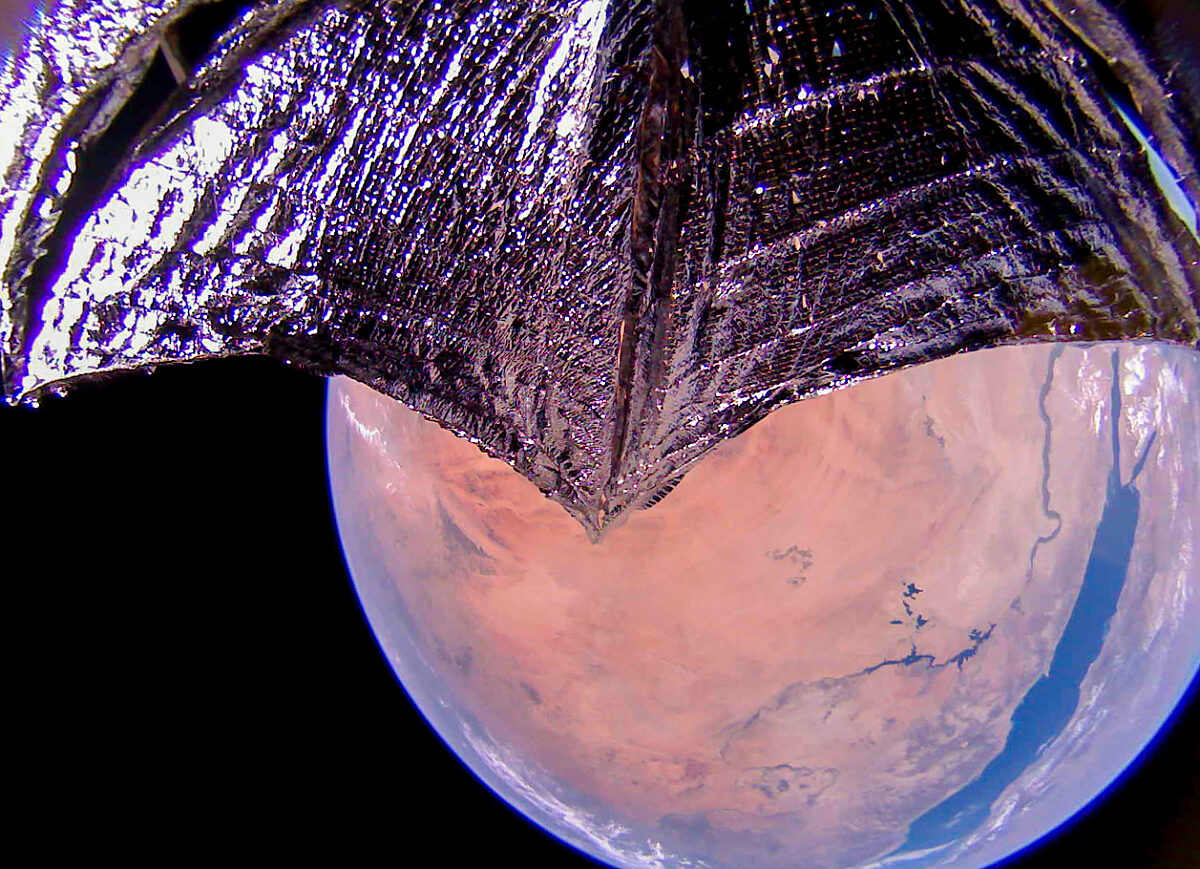

Bill Nye: Our own LightSail 2, which is in orbit right now and still taking amazing pictures and still demonstrating that if you figure out how to fly it, as the team has done, you can keep the thing aloft an extra two years, far beyond its original mission. For you Planetary Society members and listeners everywhere, whether you're members or not, thank you. Thank you. Thank you. Let's get out there and change the world.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, Bill. We'll return to LightSail when we bring Bruce in for this week's edition of What's Up.

Bill Nye: Hey, ask him what's going on. One boom has got a kink in it.

Mat Kaplan: Okay.

Bill Nye: And do you know why?

Mat Kaplan: No.

Bill Nye: Nobody knows why. That's why it's worth investigating to try to understand it. All right, you guys. Happy New Year. Thank you all for your support.

Mat Kaplan: Happy New Year, Bill. That is the CEO of The Planetary Society, Bill Nye. We've got a lot to share today, so let's go straight to my conversation with four more of my talented colleagues. You've heard them before on Planetary Radio. Editorial Director, Jason Davis. Senior Space Policy Advisor, and Chief Advocate, Casey Dreier. Communication Strategy and Canadian Space Policy Advisor, Kate Howells. And Editor, Rae Paoletta.

Mat Kaplan: We gathered around a virtual water cooler on Monday, December 26. Welcome one and all. I know that you are all celebrating just as I have been. I mean, now that people are hearing this when it's published, the JWST, the James Webb Space Telescope has been up there. And at least as we speak, everything is going great. And so, yay, everybody.

Rae Paoletta: Yay.

Kate Howells: Yay. Thank goodness.

Rae Paoletta: Great job, little telescope.

Mat Kaplan: Casey, you probably know better than anybody, at least in this group, what it has taken to get to this point with this big telescope. It's quite a milestone, isn't it?

Casey Dreier: I mean, this is literally a once in a generation event that we've witnessed. It has taken a quarter of a century to build and launched this incredible capability. And as I keep emphasizing to people, this isn't just like slapping two Hubbles together and making a better telescope. It's fundamentally going to provide a new pathway to insight to the earliest periods of the cosmos and to other areas of the universe that we just literally cannot get from existing tools. There's a reason why it took so long and cost so much to build this, because it's a fundamentally new technology. So, it's going to be truly game-changing in terms of how we view the cosmos.

Mat Kaplan: It was a very, very busy year, and we have a lot to cover. So, we'll do this in a little bit of a round-robin. Jason, let's go to you first for a busy year at Mars, especially for stuff coming down to the surface, but in orbit as well.

Jason Davis: To me, this was the biggest event of the year until the final five days of the year when JWST just completely overshadowed everything else, rightfully so. But earlier in the year, we had three new Mars missions arrive at Mars and that was a really big milestone.

Jason Davis: It was the first time three countries, three different countries had launched three different missions during the same launch window opportunity. NASA's Perseverance Rover, which is its next gigantic SUV sized Rover. That one is a big mission because it officially starts the process for sample return. It's going to be collecting samples and leaving them for future missions to collect. And we got some amazing imagery from perseverance as it landed. There's some cool cameras that took pictures of its parachute and its jet pack and all of that.

Jason Davis: Around the same time, we also had Tianwen-1 arrive at Mars, and that's China's new Mars mission. Nobody has ever been successful on their first try, the way that China was. Just really pulled it off really well. Sent back some incredible pictures of its own and is now exploring Utopia Planitia, which is the same area of Mars that NASA's Viking missions originally explored.

Jason Davis: And then you also had Hope, the UAE's, the United Arab Emirates' Mars mission. It was their first mission in partnership with some US universities. They put an orbiter in orbit around Mars, and that's going to look at the climate of Mars over time to see how ... They try to build this holistic picture of Mars' atmosphere. So, really big Mars year earlier in the year.

Mat Kaplan: Kate Howells, not surprisingly, we were celebrating the landing of perseverance, but also these other missions that arrived at Mars and the ones that were already there. Tell us about that big celebration early in 2021.

Kate Howells: Yeah. The Planetary Society has a history, a tradition, I would say, of when there's some huge monumental moment in space exploration like a Rover landing on another planet. We tend to throw a party and we call these Planetfest.

Kate Howells: Normally, in the past, we've done these in person. And I think almost always, if not always in Pasadena, California, where we're headquartered. But this time because of the pandemic, we had an entirely virtual celebration, which I think wound up being kind of a blessing in disguise. I think people were disappointed not to be able to get together in person and party, like dance in celebration when the Rover lands. But being able to do it virtually meant that people around the world could take part. And we were able to bring in a lot of speakers that I think we wouldn't have been able to get if we were doing something in person.

Kate Howells: So, we had a pretty epic two-day celebration. We had over 1,500 people take part altogether virtually, which was just phenomenal. We had 61 experts talking during 21 different sessions. So, it was kind of like this big conference and people could tune in live, ask their questions. All of the video recordings are still available on our YouTube channel. So, anybody can go and watch them, learn a ton about Mars exploration, science fiction, video games, all kinds of stuff related to space exploration.

Kate Howells: And then we had a live watch party for the actual landing of the Perseverance Rover, which was very, very exciting. So, it was great to be able to mark all of these arrivals at Mars, the sort of new era of Mars exploration with new countries taking part, and this incredible new Rover. Being able to celebrate all of that with people around the world was just fantastic.

Mat Kaplan: Lest anybody think that we are totally and only devoted to Mars, ignore the T-shirt that I'm wearing, my Mars Rover T-shirt. Let's go to Rae Paoletta. Ray, tell us about a couple of other places that were in the process either of exploring or preparing to explore Juno and Bepi Colombo.

Rae Paoletta: Yeah. Just a hop skip and a jump away from Mars, no biggie. We've got Juno still out there. I mean, it's amazing to think that it launched in 2011 and it is still kicking. We are still getting scientific information and amazing pictures back. And this year, it did not disappoint.

Rae Paoletta: Just before it wrapped its primary mission in July of 2021, in June, it took the most stunning picture of Ganymede, I think, I've ever seen. I think a lot of us probably considered to be one of our favorite space pictures of the year. It's the closest view that we've gotten of Ganymede, the largest moon in our solar system. For the last 20 years, it's just amazing.

Rae Paoletta: It kind of looks like a big jack-o'-lantern that got maybe pushed over a bit. I don't know. Maybe some people could say it looks like a bowling ball, but you could see all sorts of cool craters. I want to think it's a pumpkin, like a jack-o'-lantern, because I'm a space goth. I like Halloween.

Rae Paoletta: I'm looking towards seeing what Juno does next in this extended mission where it's going to do all its side quest and bonus features going to all the different moons of Jupiter and seeing a few of the really cool ones.

Mat Kaplan: It occurs to me that we didn't put in our little outline here, the mission that's headed toward Jupiter, to explore those icy moons. Does anybody able to say a word or two about juice?

Jason Davis: JUICE, the Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer. It's an ESA mission from the European Space Agency. And I believe we just heard that it got pushed back until 2023 at this point. That they're looking at a launch opportunity around then.

Jason Davis: Anyway, whenever it launches, it's going to go into Jupiter orbit first and then it's going to slowly spiral in and explore the outer three moons and make some really close passes of those and really try to unpack in a way that no other mission has done before. Really try to see what's going on with their surfaces and maybe try to determine whether they have subsurface oceans or get some more data on that. Yeah, that will be a really cool mission happening just a couple years before Clipper launches, NASA's Clipper mission. So, some good times to come.

Mat Kaplan: And maybe if they get lucky, fly through a plume or two. Rae, back to you and back to Mercury.

Rae Paoletta: Yeah. Who else is doing it like Bepi Colombo right now, right? Nobody. It's really cool to see Bepi Colombo on its way to Mercury after it performed the second of two Venus flybys this year. It will need all the help it can get, so it can get on its way to the planet.

Rae Paoletta: I took some really cool pictures of Venus though. It's almost like a radioactive cue ball from a distance. It's really, really bright. You couldn't get that many amazing, up close and personal details, but it was so cool to see the planet. I think what's next for Bepi Colombo is it's got to do six Mercury flybys before it actually can enter the correct orbit. So, we'll be watching and cheering it on from afar.

Mat Kaplan: Speaking of in there, close by the sun, how about flying right into the sun's atmosphere? I had to throw you another curve because another one we didn't talk about is the Parker Solar Probe, which had those just, good Lord, mind-bogglingly stunning, that video flying through the corona. What did you guys think?

Rae Paoletta: That video was just one of the coolest things I've seen all year. Probably in years. I mean, seeing the Milky Way through the sun's corona. I don't even think my brain could have understood that sentence 10 years ago. I could not have fathomed that coming to life.

Kate Howells: Another thing I loved about that is it really captured people's imaginations. I know all of us, we're always talking about space to all of our friends and family, regardless of whether they're interested in hearing about it.

Kate Howells: When I shared the video of the Parker Solar Probe footage, everybody I know who normally is pretty quiet when I post space stuff was piping up with questions and just expressing their amazement at what they were seeing. Not only is it amazement that this is what the sun's corona looks like, but also that humans have constructed a craft that can get that close to the sun, that can touch the sun. That's astonishing and very impressive.

Kate Howells: I know one of the things that we all love about space exploration is the human ingenuity that makes all of it possible. So, I think that was a really great example of just a very, very impressive mission doing something really cool that is very easy to appreciate.

Mat Kaplan: Let's stick with that theme of generating all kinds of interest from our friends and family who maybe get tired of us talking about space. Because if you're like me, the big thing that they all wanted to talk about was billionaires going into space and other people as well, as well as research. Casey, I want to turn to you. Do you think we've now seen finally the real start of commercial space tourism?

Casey Dreier: Yeah. We saw three different companies provide private access to space for three different ... Well, multiple different crews with one company launching three different times in one year, Blue Origin. I look back to SpaceShipOne from Burt Rutan launched in 2004 and won the XPRIZE.

Casey Dreier: It wasn't until 2021 this year that we saw Virgin Galactic actually begin its commercial operations for commercial customers, and it only flew once. It was a long time coming. This is what has been promised for a long time, and we're just starting to see the realization. And also, the kind of emerging complexities of the overall increase in access to space means there's all types of people now going into space that we have classically not associated with.

Casey Dreier: I think that's an interesting thing to see culturally, but also more broadly. We're seeing companies like SpaceX, not just do suborbital flights, but orbital flights with the Inspiration4 crew. And we will soon, theoretically, see tourist flight around the Moon. Also, on a Dragon.

Casey Dreier: In addition, we have the Russians launching multiple private crews to the space station, including a film crew to beat Tom Cruise. The first professional film crew in space as part of their movie. So, we're seeing this big burst of activity.

Casey Dreier: The big question is, how long and how sustainable is this going to be? Obviously, some of these first crews are not necessarily paying customers. They're high profile owners of the capital, so to speak. And then we are also seeing a lot of, theoretically, kind of promotional activities like sending William Shatner up in the space that we don't believe he necessarily paid a full ticket price.

Casey Dreier: So, we're seeing the start of this capability. And I think, again, this is one of the reasons why I think this next decade in space is going to be so profoundly interesting, because it's, in a sense, A, historical. We do not have a historical comparison to draw from to help us understand what is going to be happening. And so, seeing the start of multiple commercial tourist flights into space this year, to me, is really this opening period of this unpredictable new frontier that we're seeing unfold before us.

Mat Kaplan: To say nothing of everybody from high schools to small plucky nonprofits sending their own CubeSats up and keeping them up there for a couple of years. Something we'll be talking with Bruce Betts about when we talk about the status of LightSail 2, which is still sailing overhead. Let's turn back to planetary science now. And Jason, come back to you and talk about some notable successes related to visiting asteroids.

Jason Davis: Yeah. One of my favorite missions of the past few years, just the way it has a very can do spirit, a very unique way of doing things. It's been the Hayabusa 2 mission. It just had all these neat little innovative tricks that it used to get samples off of asteroid Ryugu, including firing a metallic plate into the surface, which was then watching plume come up off of it, which is just one of the neatest ideas I've seen in a long time.

Jason Davis: It returned its samples of asteroid Ryugu in December of 2020. However, we kind of considered an honorary 2021 event, because our best of awards at the end of the last year didn't account for it. So, we included it in our best of awards for this year. Right now, after it dropped off its samples, it headed on to a couple other asteroids. It won't get there until closer to the end of this decade, but it has a couple more asteroids to explore.

Jason Davis: And then OSIRIS-REx, NASA's asteroid sample collection mission. It did successfully collect its samples on October of last year, and it stuck around for a little while. And in May of this year, it began its long journey back to Earth. It should arrive in 2023 and drop the samples off for us.

Jason Davis: We heard a little bit about earlier this year that OSIRIS-REx might possibly be redirected on an extended mission to visit asteroid Apophis, which is kind of doing this really close flyby of Earth in April 2029. That hasn't been confirmed or approved yet, but it's something that the mission team kind of discovered earlier this year that, yes, this trajectory might be possible after the Earth drop off. So, fingers crossed. We'll get to see a really cool mission to asteroid Apophis towards the end of this decade as well.

Mat Kaplan: Kate, let's stick with small bodies out there near the Earth and not so near the Earth with a couple of other missions that got underway.

Kate Howells: I love when a year like this has missions arriving at their destinations and missions launching. And we kind of get this nice cadence. So, we have some things to look forward to that launched this year, the Lucy mission and the DART mission, both launched. Both very cool, very exciting, doing things that have never been done before.

Kate Howells: Lucy is one that I'm particularly fond of. And I got to say, I didn't know how cool it was until I listened to the Planetary Radio episode of out the mission where I discovered all kinds of incredible things about this very cool little mission. It's heading out to the Jupiter Trojan asteroid. So, it's asteroids that are in the same orbit as Jupiter, but actually so far away from Jupiter itself that I think the closest the spacecraft will ever be to Jupiter is when it launched or maybe when it does its first Earth flyby, because [crosstalk 00:25:08].

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. I think we were told. Yeah.

Kate Howells: Yeah. The Jupiter orbit is just so huge. So, that's kind of cool and mind-boggling to begin with. This little spacecraft is going to visit several asteroids over the course of many years. It doesn't arrive at its first asteroid, which isn't even one of the Jupiter Trojans. It's a main belt asteroid in 2025.

Kate Howells: And then two years later, in '27, it will get to its first Trojan asteroid. And over the course of its 12-year mission that it's got planned, it will only actually be doing scientific observation of asteroids for a total of 24 hours. That's another tidbit I learned in that Planetary Radio episode. Everyone who hasn't heard it should go listen to it, because it's such a killer episode. A mind-boggling thing.

Mat Kaplan: Checks in the mail, Kate.

Kate Howells: Yeah, thanks. 12 years of travel for 24 hours of science. And it's such important science that it's worth all of that waiting. It's such a cool mission. Once it's done, its observations of the asteroids, it's going to continue orbiting the sun forever, basically. It's going to be out there, presumably, unless something happens for millions of years.

Kate Howells: And so, one of the other things that I love about this mission is that it has a plaque on it. And unlike the Voyager and Pioneer plaques that are intended for extraterrestrials to discover somewhere in interstellar space, this one, because it's staying in the solar system, it's intended for far future humans to recover it and then find a sort of time capsule of Earth at this time.

Kate Howells: So, it's that poetry that we love. The beautiful, thoughtful visionary stuff of space exploration, when we think about what it means that we're sending something out into the solar system that could be there for millions of years. So, you got to love that. But we do have quite a lot of waiting to do before Lucy starts delivering science back down to Earth.

Kate Howells: We have a sooner payoff for the DART mission, which launched this year and is going to be arriving at its asteroid destination in September of 2022. So, not too long to wait at all. And it is going to smash into a tiny moonlet asteroid that is orbiting a larger asteroid, and it's going to hit that moonlet and see if it can change the moonlet's orbit around the asteroid enough to be noticeable.

Kate Howells: This will be our first time ever trying to change the trajectory of an asteroid. It's our first real demonstration of a planetary defense deflection technique. So, it's a huge step forward in developing our ability to protect our planet from impacts, which is obviously very important. And I think it's going to be a cool mission. There's going to be a companion spacecraft that documents the impact. So, we can see what's happening. All of that is going to be really fun and we're going to get that payoff in 2022. So, lots to look forward to there.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. That little companion, a little Italian CubeSat, hope that works out. And DART, of course, Double Asteroid Redirection Test. Casey, I'm going to go to you for a second, because this is ... I won't say the culmination, but it is certainly something that The Planetary Society has been working toward for a very long time, right?

Casey Dreier: Yeah. There's two prongs of planetary defense. There's the active deflection, and then there's the detection aspect that we're also pushing forward too with future missions like NEO Surveyor, which I would also add as an important marker this year being approved for future development, officially becoming a project mission this year.

Casey Dreier: Planetary defense, this is something ... Just broadly to step back, this is the first planetary defense mission. And planetary defense missions are unique. They're not science missions. They're not human space flight missions. They're not even really technology demonstration missions. This is a new category of mission, and this is one of the reasons why it took so long to start seeing missions like this happen. They didn't have a place to be slotted into within NASA's existing structure.

Casey Dreier: So, we're seeing this development. We're seeing, in a sense, the bureaucratic process work by creating a new home for these very specialized, critically important types of missions. And it's taken decades to really establish and convince people, and also establish the science and importance behind this. We forget too, I think, establishing that there was planetary threats from large asteroids.

Casey Dreier: We only started determining this 40, 50 years ago. Really understanding the scope of the asteroids out there in the last few decades. This is all very new. And so, this is NASA adapting too, and also the US Congress mandating responsibility to NASA in various pieces of legislation to do things like this. So, DART is this kickoff, I hope, of a very bright future of planetary defense missions. And these very, again, specialized, dedicated missions to ensure our long-term survival, which again, as Kate said, I think we take the bold stance as a good thing.

Mat Kaplan: Rae, back to you to talk a little bit about what's still ahead of us. Neglected sister no more, Venus. Not good just for giving a gravity boost, but worthy of sending several new missions to.

Rae Paoletta: Yes, Matt. I'm so excited for this. The end of the decade, we are going to get some bonkers missions to Venus. And all of us who are Venus fans have been waiting for this moment. There just hasn't been a mission like this to Venus before, and we're getting three unprecedented admissions. It was announced back in June that NASA is going to send two spacecraft, DAVINCI+ and VERITAS to uncover literally all of the secrets about Venus.

Rae Paoletta: They're set to launch sometimes between 2028 and 2030. So, again, we are going to have to wait a little, but I think it will be well worth the wait. We're supposed to learn more about Venus' plate tectonics or lack thereof. That's kind of a strange mystery of Venus.

Rae Paoletta: The tesserae, which are just these extremely deformed regions. You know when you're like at an ice skating rink and everyone is done ice skating, but you kind of look at the ground and it's all scratched up and wild? That's basically the tesserae, but like on an actual planet. So, it's going to be really cool.

Rae Paoletta: Then we got news shortly after. And how could I forget? Sorry, I have to interrupt myself there. We're also going to learn about the potentially active volcanoes on Venus. It's just the best planet. It's so spicy. I can't wait.

Rae Paoletta: We also got news later about the European Space Agency sending its own mission called EnVision, which is going to do some really cool high resolution radar mapping. It's going to study the atmosphere. I believe that launches in the early 2030s, but a firm date has not been said.

Mat Kaplan: Casey, listening to all of this, one might be led to think that these are good times for planetary science and maybe for all of space science. Tell us the current status of things briefly as you often do on the monthly space policy edition of Planetary Radio. But particularly, looking at the end of the first year of the Biden administration.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. Well, we've seen some really promising starts in terms of allocating resources for NASA science and NASA just in general. The Biden administration took power this year in the United States and put out its first budget proposal for NASA for fiscal year 2022. It exceeded our recommended growth levels by a few percentage, so it's 7% growth for NASA. Record levels of funding for planetary science. Increases for Earth science, astrophysics.

Casey Dreier: NASA science just does very well in this budget and has generally been supported by Congress as it has been, so in the last few years. I think back to when I first started at The Planetary Society, when we were fighting this rare guard action just to try to prevent cuts or to prevent cuts from being as bad as they were originally proposed. Now, we're seeing continued growth as almost universal acceptance that NASA science is important and worth funding.

Casey Dreier: And we're enabling all of these types of missions that we're talking about today, not just the ones that we're seeing finally happen. But as Rae was talking about, the ones that will be happening now, thanks to these long-term budget commitments from the past and current administrations and multiple types of US congresses.

Casey Dreier: So, this is really good times for NASA science. And it's enabling the types of stuff we wanted to see. It enables NASA to take risks with big missions like James Webb. It enables NASA to attempt to send humans back to the Moon, to work with other companies, and industry, and other nations to achieve that goal. And then also to really pursue these ambitious missions like Mars sample return, the Roman Space Telescope, and then these future commitments for long-term efforts to search for life in the universe.

Casey Dreier: And none of this happens without the money to do it. The one thing that doesn't get cheaper with time is people's salaries. People are at the core of enabling NASA science and NASA missions in general. You can't replace them, and that's why you cannot just do more with less. In space, you do more with more. And thankfully, we've been seeing the Biden administration support that.

Mat Kaplan: Much more of our 2021 space review is just ahead here on Planetary Radio.

Bill Nye: Hi, everybody it's Bill. 2021 has brought so many thrilling advances in space exploration. Because of you, The Planetary Society has had a big impact on key missions, like the Perseverance landing on Mars, including the microphone we've championed for years.

Bill Nye: Our extended LightSail 2 mission is helping NASA prepare three solar sail projects of its own. Now, it's time to make 2022 even more successful. We've captured the world's attention, but there's so much more work to be done.

Bill Nye: When you invest in the Planetary Fund today, your donation will be matched up to $100,000, thanks to a generous member. Every dollar you give will go twice as far as we explore the world's of our solar system and beyond. Defend Earth from the impact of an asteroid or comment and find life beyond Earth by making the search a space exploration priority. Will you help us launch into a new year? Please donate today. Visit planetary.org/planetaryfund. Thank you for your generous support.

Mat Kaplan: I think we have time to broaden the home world scope a little bit, because we are seeing so much happen around the world, including from nations that are still new to planetary science. I mean, Hope. Jason, you mentioned its success from the United Arab Emirates, which has now announced this even more ambitious asteroid mission that's a few years off.

Mat Kaplan: India, of course, with the MOM, the Mars Orbital ... What is it? Mars Orbital, I forget what the second M stands for.

Casey Dreier: Mission.

Jason Davis: Mission.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you. Mars Orbital Mission. Wouldn't you know? Let's talk about some of our bigger partners and more active partners. I don't know who can talk about ESA, but Kate, we sure can turn to you to talk about what's happening in Canada with the Canadian Space Agency.

Kate Howells: Canada's space program is going strong. We've got a lot of commitments to participate in the Artemis program, returning humans to the Moon and all of the various components like technological components that play into that overall mission architecture. And a Canadian astronaut is slated to be on the first orbital mission. Not a Moon landing, but orbiting the Moon.

Kate Howells: We're very excited about that. Canada has a long history of being a reliable contributor to international missions. We're seeing more of that. We've also got Canadian instruments on the JWST mission. So, really looking forward to highlighting and celebrating that. We do what we can in Canada to remind Canadians that, yes, we do have a space program.

Kate Howells: The Canadian Space Agency doesn't have the same name recognition as NASA yet, but we're working on that. But anytime we can remind Canadians that we all have made significant contributions to some of the most exciting missions happening out there. So, it's really exciting to see stuff on the horizon for Canada and to celebrate what we've already accomplished. So, yeah, I'd say things are looking bright for Canadian space policy.

Mat Kaplan: And I know this is throwing all of you yet another curve, but anybody who wants to chime in about activity by the European Space Agency and how it's funding of space science, planetary science is progressing? I mean, it's obviously come up several times already in this conversation.

Casey Dreier: Europeans have a very different process for allocating funds, and they have a certain amount of money for the European Space Agency allocated for science over time as a percentage of its budget. It's a much smaller budget overall. I think the European Space Agency's annual budget is in the $6 to $7 billion range total.

Casey Dreier: Their science budget is a portion of that, smaller than the US one, but they can do so much with it because they have this very long-term stability that allows them to do very tight planning and maximizes the overall commitments that they make. In addition to contributions by their member states over and above the minimum contributions that they all make to ESA.

Casey Dreier: So, we have seen actually a very big commitment from the European community with Mars sample return. That's probably the most important development that we've seen in the past few years that they're coming in at a very high level. Not only are they committing to XMRs, which has turned out to be a roughly two billion Euro project that we'll hopefully see launch next year, but we're seeing with the Mars sample return, they're providing a fetch rover and the Earth return orbiter. These are not small projects. We're talking about a multi-billion Euro commitment by them. And that's, again, on top of and above the minimum level of contributions for ESA itself.

Casey Dreier: So, we're seeing them really step up for that. We're seeing them step up with Hera, speaking of planetary defense, flying by asteroid Didymos a few years after the collision by DART to really characterize the impact rate and to help really refine those models of planetary defense and deflection capability.

Casey Dreier: They're putting in a lot of effort and support for this. And again, not to mention their large contribution to the JWST, which just launched on an Ariane rocket. So, we're seeing a lot of contributions from them. I would add just broadly too that the whole astrophysics side of things, their deep space telescopes contributions. We're seeing, I think, a broad increase in funding. Not necessarily the levels we're seeing in the US, but continued commitment that has been, again, really fundamentally enabling and making these smart partnerships.

Casey Dreier: I think we're seeing similar commitments by the Japanese aerospace industry as well. Jack says, launching their mission, MMX to Phobos sample return. They're just really, really killing it in these small asteroid, small body missions. The Japanese have been really specializing in those.

Casey Dreier: And then also, of course, we're seeing China's incredible capabilities, as Jason mentioned at Mars. We're seeing continued commitments to the Moon. Now, announcing a second lunar sample return from the south pole of the Moon, additional lunar landing, and more broad commitments to planetary exploration in general.

Mat Kaplan: Good times indeed. Jason, take us up there one more time to that place where that little outpost of humanity, where people have been living for over 20 years now. How was the year for the International Space Station?

Jason Davis: It's safe to say that this is the year that NASA was able to fully realize the power of the International Space Station for research. They've been wanting the additional capability to get an extra crew member up there for a long time. They've been relying on the Russian Soyuz to transport its astronauts. SpaceX launched the Crew-1 mission with two astronauts back in 2020. That crew came home in May of this year, and that was very quickly followed by a second crew that was on the station from April to November. A third crew SpaceX Dragon mission launched in November. And that crew is still aboard right now.

Jason Davis: I would say it's a major win for NASA in terms of finally getting this capability up and running that they've been trying to get up and running since the end of the Space Shuttle program in 2011.

Jason Davis: At the same time, one of their astronauts, Mark Vande Hei started a year long mission. He went up on a Russian Soyuz. So, we're continuing to see some NASA astronauts flying aboard the Soyuz. He will get there for about a year and even surpass Scott Kelly for that long duration ISS mission.

Jason Davis: At the same time, Russia finally got its Nauka module launched and installed. They had been working on that for a very, very long time. That module has been through a lot of problems on the ground. They finally got it into space. There was a lot of drama as they got it docked to the station and its thrusters began firing unexpectedly and knocked the ISS out of its correct orientation. Finally got all that under control and that module is now up and running on the station for them as well.

Jason Davis: As Casey had said, we're getting these commercial tourism missions, or maybe tourism is not always the right word where we had the film crew come up and shoot part of a movie on the space station. This is a Russian crew. A director and an actor. Yeah. Really seeing a lot of activity at the ISS. It's just busy as it's ever been right now.

Jason Davis: At the same time, China has done the same thing. It's Tianhe core module launched back in April. This is the core for their brand new space station. They sent their first crew up from June to September. There's a new crew in orbit right now. And in fact, they just went on a space walk. So, China is really getting in and swinging things too with their space station.

Mat Kaplan: A lot going on. And I noted a cargo mission just went up with a whole bunch of new science for that national laboratory that orbits over our heads. Let's now turn to pop culture. Space and pop culture, which Rae is something that you suggested that we add to this conversation.

Mat Kaplan: I got to say yesterday, I finished the ninth and last book in The Expanse series. Wow, what a finish. For any of you who have not gone through it, I've been waiting for that book for a very long time. One heck of an ending. Pardon my French. It was a pretty good year overall for representations of space in pop culture. Rae, you suggested the topic. So, you want to get us going?

Rae Paoletta: Yeah. I mean, I feel like a lot of the space pop culture moments maybe just snuck in at the end of the year. I'm thinking of Dune and Don't Look Up specifically, which I really loved both of them, by the way, but I feel like I have to give a very special shout out to Dune for providing me with my new soundtrack to my life.

Rae Paoletta: Also, just blowing my mind, man. I didn't know anything about Dune going in. Like I went into this movie knowing nothing about the lore. I just didn't know anything about it, and I came out profoundly changed. In fact, I wanted my Halloween costume to be the Shai-Hulud so badly, I tried to make it happen. I was going to buy one of those big hoop things that cats and children stuff crawl through. And I was going to put it over my end. Did not come to fruition, unfortunately, but there's always next year.

Mat Kaplan: With big crystal teeth, no doubt that you'd glue into place.

Rae Paoletta: Yes.

Mat Kaplan: Anybody else have thoughts about Dune? Or what else did you enjoy where pop culture turned to outer space?

Jason Davis: Yeah, I'll second Dune. I went and managed to see that in the theater. I've read maybe three of the books and I've seen the first movie, or at least one with Patrick Stewart and Sting and everybody. It was really satisfying to see. It was such kind of a meme, almost a meme movie. It wasn't really taken seriously outside of the core niche group of people who were really big Dune fans.

Jason Davis: And then going and seeing it in theater, it was just like, "Wow." They're going for it. They're taking it seriously. They're going full. This is a very dramatic, epic story that we're telling here. I absolutely loved it. I can't wait for the second part.

Mat Kaplan: We got to turn to Don't Look Up. I know not all of you have seen it yet. Of course, we had that conversation with the director, Adam McKay, and our friend Amy Mainzer, who was the science consultant right here on Planetary Radio just a couple of weeks ago.

Mat Kaplan: I loved it. I don't think it's done as well in theaters as I thought it deserved to do. But my god, has anybody ever seen, for those of you who've seen it, a movie that did such a good job of getting the science right?

Rae Paoletta: I think it did a good job of getting the panic right, more than anything. I was like, "Hmm, this is the appropriate level of anxiety I think we should all feel about a climate change," which is the movie I guess was really an allegory about climate change.

Rae Paoletta: Yeah. I mean, from a planetary defense level, I thought it definitely hit all the right notes. I thought it was appropriately spooky and scary. There was a lot of laughs too. I personally thought Jonah Hill was hysterical in that movie. I think he really, for me, he was the winner, except for, of course, Meryl Streep who I'm obsessed with also.

Mat Kaplan: I thought everybody in it was just great.

Rae Paoletta: Yeah. Everyone.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Anybody else have any pop culture highlights to bring up?

Kate Howells: I was just going to say, I'm woefully behind on all the pop culture stuff. I didn't see Dune, because I haven't felt comfortable yet going back into theaters. And I feel like it's a movie you have to see on a big screen, but I'm missing my chance, so I'm going to have to just watch it at home.

Kate Howells: I also was a huge fan of the David Lynch Dune. So, I have to try to put that out of my mind and not compare the two when watching it. And I haven't seen Don't Look Up yet, but I'm going to watch it with my family who are all gathered for the holidays still so that I can teach them about planetary defense, because that's always going to be the angle is when there's a pop culture moment and you can use it to teach people about the true important stuff. That's what I'll try to do. So, I have lots to look forward to.

Mat Kaplan: As I said to Amy Mainzer and Adam McKay, the only feature film I've ever seen that talked about the benefits of peer review. It's a key point in the movie. Kate, I'm so glad to finally meet somebody else who actually kind of enjoyed the David Lynch film. It's at least a noble effort.

Kate Howells: I loved it. I was introduced to it as an undergraduate when I was late teens. I definitely joined that cult following. I've seen it a bunch of times. It's so bizarre. I appreciate what Jason said that it's good to see Dune being taken seriously by this new movie, but I loved the weird, weird, weirdness of the Lynch version. Like I said, I just have to separate them in my mind and not compare them, because it's definitely two different treatments.

Mat Kaplan: So, I would feel bad if I didn't at least mention our friend, Andy Weir's great book, Project Hail Mary, which is absolutely outstanding. A laugh, a page and probably a fascinating, innovative idea per page. So, good on you, Andy. Rae, did you want to close this out?

Rae Paoletta: I did just want to mention one last thing for the Dune heads out there, which is, I guess, the fan army that I've now made up. It's a shame that we did not get Jodorowsky's Dune, and I feel like we just need to mention that for a quick second, because that would have been wild. I think it was like supposed to start like Mick Jagger or David Bowie was supposed to be in, I think. Can you imagine?

Kate Howells: Yeah. There's a really good documentary.

Rae Paoletta: The doc is great. Highly recommend documentary.

Mat Kaplan: Documentary about that never to be completed production of Dune by that terrific director. I got to say, my wife, when she said, "Well, is Sting in the new Dune?" And I said, "No." She said, "Well, why would I want to see it?"

Rae Paoletta: Love that.

Mat Kaplan: Lightning round. We have about five minutes. Everybody set. Jump in as you will. Human landing system award controversy. Casey, I guess we better start with you.

Casey Dreier: I think that was quite notable. NASA awarded the first contract for a lunar lander for humans in 50 years and was immediately challenged in court by Blue Origin. It was given to SpaceX. Blue Origin challenged it, delayed it for a bunch of time and ended up given it to SpaceX anyway. And so, they succeeded in further delaying Artemis human return to the Moon for no clear benefit of their own. You're seeing represented in this type of activity, egos now being clearly engaged in space exploration in addition to national symbolism. And so, this is something we will get used to more going forward in the near future.

Mat Kaplan: And maybe that's another positive sign of the progress that we've made. Somewhat in connection with that, Space Launch System and other Artemis program delays, including the space suit, which we'll be talking about on this show next week with one of the major contractors for that new Moon suit.

Jason Davis: It was absolutely stunning to see the Space Launch System finally stacked this year in the vehicle assembly building. That rocket, it's been through so much. People love it and people hate it. But just seeing the sheer scale of that thing in the VAB was really a site to behold. Now, it sounds like one of the engine controllers is bad for one of the engines and we won't be able to see it fly until March or April possibly. So, just another delay, wait a little bit longer to see that gigantic thing fly.

Mat Kaplan: But then there's Starship from Elon and other commercial launchers that are proceeding, but we'll stick with Starship for this lightning round. There is a great cover on the current issue of Ad Astra from our friends at the National Space Society that shows these two giant rockets next to each other. It's a pure fantasy, of course, at the moment, but who knows, maybe someday. Starship, look like we're going to maybe see it happen soon, go into space at least.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. I mean, I think this is one of those, A, historical moments that we're seeing. This is a super heavy launcher that could fundamentally transform access to space, or it could not. It could fail, right? I think we should not dismiss the intense technological challenge it will take to build a functional, reliable, super heavy lift, reusable, two-stage spacecraft, but we shouldn't throw it away either. They have probably some of the best people in the world working on it.

Casey Dreier: It's one of these issues that could be profoundly exciting, but we also need to temper our expectations and understand that this is still operating in the realm of physical realities that have limitations and issues just like everyone else. But what's so exciting about it is that they're doing it all in the open, and it seems to be happening so rapidly.

Casey Dreier: And it is a fascinating contrast to the more stayed process of the SLS construction where, again, the fundamental difference is when NASA does a project like the SLS, it's fundamentally a NASA project. Even though Boeing is building it, they have the burden of national symbolism. They have to deliver, and that makes it a very conservative development process. It's easier to take the hit in the development as long as the ultimate thing succeeds.

Casey Dreier: When you have a company doing a project and particularly the way that SpaceX has set it up, they're allowed and allow themselves to fail, and they can fail publicly, and that's okay. They don't get Congress breathing down their neck if that happens. That gives them a lot of freedom to experiment and try things out. And we're seeing, again, the two things really compared to each other is very interesting thing to look at. And Starship again, we will see which one will launch first. Starship or SLS in 2022.

Mat Kaplan: Europa Clipper got a quick mention earlier in our conversation. Were any of you also relieved when we saw that it's going to head out to our Jupiter on top of a Falcon Heavy and won't have to wait for Space Launch System rocket and SLS? Rae?

Rae Paoletta: Yeah. I think it was the right call. It's going to just be an easier timeline, to be honest. I'm super excited for that mission, by the way. Remembering correctly, it's like 2024 that it launches, right? So, we still have a couple more years.

Casey Dreier: No one wanted a repeat of Galileo waiting for its ride on the Space Shuttle and then having a hardware fault as a consequence of that. It also saved literally a billion dollars for the program in multiple ... Not just the cost of the SLS, but the cost to adapt it to launch on what turned out to be a very rough ride on an SLS for a science mission.

Casey Dreier: NASA made the right call, but it wasn't NASA's call to make. Congress made the right call, but they had to change legislation. Previously, NASA had been mandated by law to launch in the SLS. That changed this year to the right consequence, and NASA was able to make the right call based on that.

Mat Kaplan: We're in our last few moments. What else do you folks want to bring up before we close this conversation?

Kate Howells: I'll just say that I cannot believe how much has happened in one year. When we started to put down notes of what we would talk about this episode, I was astonished. I mean, I think everyone has found the passage of time a little strange the past couple years, but it certainly feels like the year has gone by quickly and yet so much has happened. I mean, the fact that all the Mars arrivals this year, that seems like such a long time ago. So, I'm just astonished. I'm impressed at what the world is able to accomplish. I'm amazed at the things that we're learning. It's been such a great year.

Casey Dreier: It just further goes in my feeling that the 2010s were a transition decade in space. And now, we're seeing the outcome of that long extended transition where there just wasn't as much happening. And it's going to continue seeing stuff like this over the next few years based on a lot of work that's been happening for more than 10 years. So, this is an exciting time to really be on the end period of that long and painful transition.

Rae Paoletta: Similar to Kate, I feel that these last couple years have been really difficult, but I think that space and space exploration does a really good job of providing hope. I don't know about you all, but I feel like we really need that optimism more than ever right now, so it is really great. I think stop and reflect. That's what I think all end of the year celebrations do well. So, I'm really glad we did this. Thanks everyone.

Mat Kaplan: Jason Davis, we'll give you the last word.

Jason Davis: Great year in space exploration as everyone has just said, and I'm looking forward to 2022. It doesn't let up. As Casey said, it's just the beginning of this exciting decade that's to come. Next year, we've got things like DART reaching its asteroid. ExoMars is going to launch. Psyche is going to launch. Just more of the same and a lot of other stuff happening. Let's do it again.

Mat Kaplan: Lots to look forward to. I look forward to continuing to work with all of you, my dear colleagues, over this next year at The Planetary Society. You will be seeing great content and great activity from all of them. Thank you so much. Editorial Director, Jason Davis. Kate Howells, Communication Strategy and Canadian Space Policy Advisor. Editor, Rae Paoletta. And Senior Space Policy Advisor, Chief Advocate, Casey Dreier. I look forward to talking to all of you, again, across the year right here on Planetary Radio as well. Happy New Year, everybody.

Kate Howells: Thanks, Mat. Happy New Year.

Jason Davis: Thanks.

Rae Paoletta: Happy New Year.

Mat Kaplan: It is time for the last What's Up of 2021. So, we welcome the chief scientist of The Planetary Society, also the Program Manager, I think it is for LightSail 2, the whole LightSail program, actually, that's Bruce Betts. Welcome, happy New Year.

Bruce Betts: Happy New Year, Mat. Welcome to you.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you. Lots of wonderful holiday wishes from so many of you out there. Thank you one and all. Here's one from Michael Reitmeier in the State of Washington where it does tend to be cloudy. He says hello from the Pacific Northwest. I'll have to take Bruce's word for his What's Up segment. All I see lately is the great dihydrogen monoxide nebula.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, sorry. I don't, I don't mention that every week because it doesn't change.

Mat Kaplan: Be careful, Michael. Watch out for the dihydrogen monoxide. It can be very dangerous if it's in high enough concentrations.

Bruce Betts: And if you're underneath it for an extended period of time.

Mat Kaplan: So, what's up?

Bruce Betts: What's up? We got our last views of the beautiful planetary lineup in the early evening, low in the west. From lowest and hardest to see, but brightest is Venus up to Saturn and then up to bright Jupiter. We got Mercury hanging out with the gang right now. And in fact, it is above Venus for the next week or so. And the Moon, the crescent Moon. If you've got your crazed low horizon view to the western horizon, you're looking as soon as you can after sunset. Look for the Moon to pass on the 2nd of January, Venus on the 3rd, Mercury on the 4th. Saturn, and on the 5th, Jupiter. Party on.

Mat Kaplan: Party on indeed.

Bruce Betts: Don't miss that meteor shower that's happening. The one with the Q.

Mat Kaplan: The one you don't want to say the name of?

Bruce Betts: The Quadrantid. Oh, that wasn't bad.

Mat Kaplan: That was good. Well done.

Bruce Betts: I'll leave it at that. It can be one of the best showers of the year, but it tends to have a pretty sharp peak. So, check it out as close to the peak, which is the night of January 2nd to the 3rd. You can stare up and see tens of meteors per hour from a wonderfully dark site. We got Mars, but Mars will be getting better in the morning later in the year.

Bruce Betts: We move on to this week in space history. No, it's going to be 2022, that will make it three years ago in 2019. New Horizons did the farthest fly by of an object from earth ever when it flew by the 50 kilometer diameter Kuiper belt object, Arrokoth.

Mat Kaplan: And I was out there. I was with the crowd at the Applied Physics Lab in Maryland, and it was a heck of a great event. We had quite a party.

Bruce Betts: I thought you were out there with Arrokoth. Wow.

Mat Kaplan: It was just a quick visit.

Bruce Betts: And 120th anniversary of the discovery of Ceres, which now would be the first discovery of a dwarf planet at the time it was a planet, and then it became an asteroid or even occasionally was a comet, and became a dwarf planet. And so, it's had a real identity crisis, but happy 120th anniversary.

Mat Kaplan: I had no idea that it was considered for any period of time as a comet.

Bruce Betts: Well, I may have made that part up. No, that's what I've read. I couldn't find anything concrete on that. So, you might be right. Everything else is true, I swear it.

Bruce Betts: Speaking of truth, I go on to random space fact. At the end of 2021, which it is, we have the most craft operating at Mars ever. By my count, 13 of them. Eight orbiters, three rovers, one lander and one helicopter.

Mat Kaplan: Well done. Well done. I was waiting for the five golden rings, of course.

Bruce Betts: It's a totally different song. Totally different. Shall we move on to the trivia contest? I said, who do we have to thank for suggesting the planet name Uranus? How did we do, Mat?

Mat Kaplan: This was quite a response. A near record response partly because we heard from a lot of young people who are lucky enough to be in Mr. Chris Midden's 6th grade science class in good old Carbondale, Illinois, where by the way, they are just over two years from their second total solar eclipse in seven years, because Carbondale, that's where the paths of these two eclipses happen to pass each other or cross over each other.

Mat Kaplan: So, hello, all you boys and girls out there and hello to Chris, who we got to meet when we were there for the first of those total solar eclipses. I have an entry here, a first time entry, or at least a first time winner from Brian Gott in Ohio. He says, it was German astronomer, Johann Bode who suggested calling it Uranus in keeping with the tradition of using names from mythology.

Mat Kaplan: William Herschel, who discovered it, we've talked about this before, wanted to name it after King George III. Imagine, says Brian, sending a probe to planet George. I don't know. I kind of like that, I think. Is he right though?

Bruce Betts: He is indeed correct. Bode came up with the name that was seen elsewhere than Great Britain as less offensive as George's city is, George's star, named after George III. So, eventually, Uranus got taken as the name and we've been discussing pronunciation and making cheap jokes at its expense ever since, at least for the English language speakers of the world.

Mat Kaplan: And we are not done with those cheap jokes. We'll have a few in a moment.

Bruce Betts: I thought not.

Mat Kaplan: Congratulations, Brian. We are going to send you that beautiful 2022 International Space Station wall calendar. We'll get that in the mail to you very soon from our Pasadena headquarters.

Mat Kaplan: Before we get to the bad jokes, Barry Olson, Alberta, Canada, and a bunch of other people said, "Bode or Bode based that name, Uranus, on the name of the Greek god of the sky, Ouranos. But [Setapong 01:02:43] in New York, Astronomer Claude Plymate, old friend of the show, and some other folks said, "As all planets before this were named for Roman god, so it would have been more proper to name the planet Caelus, the Roman equivalent of Uranus.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. Uranus, my impression, is sort of a Latinized version of Uranus, and I don't know how to pronounce either. So, yeah, it's confusing, but it happened.

Mat Kaplan: Dursten Zimmer in Germany. "Bode probably didn't speak English well enough to understand that calling it Uranus would cause countless versions of the same lame joke, forever harming the sincerity of missions to explore the planet."

Mat Kaplan: Carlos Perez also in Germany. "I guess I didn't see this episode of Futurama, only the greatest science fiction TV series in history. Professor Farnsworth apparently said that in 2620, the name Uranus was finally changed to put a stop to all those 3rd grade jokes. They changed it to Urectum."

Bruce Betts: Well, that will be interesting to see if that develops.

Mat Kaplan: Yes. Well, we'll have to hang around for 600 years to find out.

Bruce Betts: Okay.

Mat Kaplan: Okay. I'll see you there. Norman [Kasun 01:04:01] in the UK. "The Georgian name did not catch on among European astronomers. In France, Jérôme de Lalande called it Herschel." Which would be kind of nice. "And Louis Poinsinet de Sivry tried Cybele, the great mother. The Swede, Erik Prosperin, suggested, are you ready for this, Neptune." Yeah. You knew that, that it almost became Neptune, or at least it had a shot?

Bruce Betts: Well, that it was suggested.

Mat Kaplan: Devon O'Rourke in Colorado. "As usual with Dr. B's questions, I learned not just about Bode or Bode, but also limb darkening, the invariable plane, and a value for the internal heat flux of Earth, 0.075 watts per square meter, if you're curious. Thanks for the rabbit holes, Bruce."

Bruce Betts: You're welcome. If there's any consolation, I go deep down them myself when I'm coming up with these. I was almost late to our recording, because I had ended up in a LightSail related rabbit hole. Happy rabbit hole hunting.

Mat Kaplan: We'll close this contest with this poem from Jean Lewin in Washington, our poet Laureate. Day Fairchild taking the week off. "Georgium Sidus was the name chosen by Herschel himself. Alternatives, though, were soon proposed. So, George's name was shelved. Neptune, once it made the list, but was not yet to be 70 years transpired before everyone could agree. Given the name Uranus named for Saturn's pop proposed by Johann Elert Bode, his suggestion we would adopt."

Bruce Betts: Yeah, it does make a nice thematic thing that you've got a Saturn as Jupiter's father and Uranus or Ouranos as the Greek equivalent. Anyway, Greek and Roman ... You got father, father, father. Speaking as a father, I like it.

Mat Kaplan: Hey, dad, what do you have for next time?

Bruce Betts: Well, dad, I've got a simple question, but I've got caveats to try to prevent the trick question confusion. In 2021, how many deep space launches were there? Deep space, defining as to the Moon or beyond and, yes, count JWST as one of them. Go to planetary.org/radiocontest. Launches, not spacecraft. Such a simple question with so many potential confusing places to go.

Mat Kaplan: Let's see how people can find other holes to dig themselves into out there. They have to do that though by the 5th of January. January 5, that's Wednesday at 8:00 AM Pacific time to get us the answer for this one. It's just the beginning of the year. Let's give away another one of those ISS International Space Station wall calendars. They're beauts. They really are. All right. We're through that. It's your contribution now to the best of 2021, and who would be better to tell us about the status of LightSail.

Bruce Betts: LightSail, The Planetary Society's solar sail spacecraft launched in 2019 is still flying. We're still working with it. I'm still taking pretty pictures when I can. Teams still working to make it sail as efficiently as possible. I think I quoted Charles Dickens in a recent webinar. I'll do it again. It was the best of sailing. It was the worst of sailing in 2021.

Bruce Betts: We, really, over the summer, had some of our best sailing where generally the solar sailing propulsion is balanced by the atmospheric drag. And typically, we lose altitude every day, but we lose less when we're sailing. We actually gained altitude on several days during the summer when after we had done some calibration changes of the gyros. Basically figured out how to sail the spacecraft better.

Bruce Betts: And then solar storm started hitting, and those inflate the atmosphere. They heat the upper atmosphere and that increases the drag. And so, it's been rather dragged for the last two or three months. We're fighting it, but losing more altitude than ever before. So, as we always knew, we will end up in a fiery reentry of glorious destruction. Not sure when. At least several months off, but we will keep flying it and doing our best.

Bruce Betts: It's still working. Nothing new is broken. We're still going. We're still getting the most of it, and we're still putting our information out there. And we've also been working, especially this year, with some upcoming NASA emissions that are using solar sails. So, NEA Scout, and Solar Cruiser, and ACS3, which is in future Earth orbiting solar sail. NEA Scout, of course, going to a near Earth asteroid. And Solar Cruiser going out to Earth's sun L1 Lagrange point and also going to higher inclination doing an exciting stuff a few years off. But NEA Scout will launch on the first launch of SLS. So, whenever that happens, we're looking forward to NEA scout and taking solar sail technology to the next level.

Mat Kaplan: Quite a legacy for LightSail and all of you who've been involved in this project. And that of course includes all the members of The Planetary Society and everybody who gave to the LightSail program. So, good on all of you.

Bruce Betts: I just want to, once again, thank everyone who supported this. This was completely supported by individual donations of really unprecedented in space, how much support we got over the 10 years, 11 years now of the program. Well over seven million, which is still operating on a shoestring budget for a spacecraft, but enough to make it work, and we appreciate it.

Mat Kaplan: So, I got to ask because the boss, Bill Nye asked me to. What's the story with that one boom arm that maybe malfunctioned a little bit?

Bruce Betts: So, we have four booms that are metal. They're made of an alloy called elgiloy. They're four meter long booms that pull the sails out. And when we first deployed in 2019, one of those booms didn't deploy all the way. And over the first two to four months of the mission, we found the sail moved enough that we could see a bend in the boom. So, there's a Z shaped bend in the boom. The good news is it has not particularly changed since the first few months of the mission. So, we're still in a stable sailing configuration.

Mat Kaplan: I think we've satisfied Bill's request. I think we've finished another week. The last one, as I said, of 2021 of What's Up.

Bruce Betts: Excellent. All right, everybody. Go out there, look up the night sky and think about 2022 and all the cool space stuff that's going to happen. Thank you. Good night.

Mat Kaplan: And we'll be reporting all of it to you including here on What's Up with the Chief Scientist of The Planetary Society, Bruce Betts. Looking forward to another year with you, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: And I with you, Mat. Thanks for big fun, once again, this last year.

Mat Kaplan: Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and has made possible by its members. Thank you one and all. Mark Hilverda and Jason Davis are our associate producers. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. Thank you to you guys too, and happy New Year everyone. Ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth