Planetary Radio • Oct 06, 2021

Why didn’t Dawn land on dwarf planet Ceres?

On This Episode

Marc Rayman

Chief Engineer for Mission Operations and Science, Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

It started with a question from a listener. The answer comes from Dawn mission chief engineer and mission director Marc Rayman. Marc also tells us about his new job as chief engineer for mission operations and science at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and shares his love of space exploration with Mat. LightSail 2 is still going strong! Program manager Bruce Betts opens this week’s What’s Up segment with a mission status report.

Related Links

- Dawn mission

- Asteroids, comets and other small worlds

- Marc Rayman’s TEDx talk: If it isn’t impossible, it isn’t worth trying

- Video: At home in space: Marc Rayman gives us a tour

- LightSail, a Planetary Society solar sail spacecraft

- The Downlink

- Subscribe to the monthly Planetary Radio newsletter

Trivia Contest

This Week’s Question:

What major political event happened in the USSR while the Voskhod 1 mission was in space?

This Week’s Prize:

A safe and sane Planetary Society Kick Asteroid r-r-r-rubber asteroid.

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, October 27 at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

What moon of a planet has an orbital period closest to 24 hours or one Earth day (sidereal period).

Winner:

The winner will be revealed November 3, 2021.

Question from the Sept. 22, 2021 space trivia contest:

What currently functioning Mars orbiter has the longest orbital period?

Answer:

India’s Mars Orbiter Mission, also known as Mangalyaan, has the longest orbital period of currently functioning Mars orbiters at just under 73 hours.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: Dawn did not attempt the first landing on a dwarf planet. Marc Rayman will tell us why this week on Planetary Radio.

Mat Kaplan: Welcome. I'm Mat Kaplan of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. I only meant to pass along a simple question from a listener, but conversations with Marc Rayman are just too good to abbreviate. That's why we'll spend a few extra minutes talking with JPL's new chief engineer for mission operations and science. More than 27 months sailing on sunlight and our LightSail 2 is still up there.

Mat Kaplan: We'll get a mission update from LightSail program manager Bruce Betts, just before he treats us to a great night sky and much more, including a special extended deadline for the new space trivia contest. Have you seen the newest closeups of Mercury? The European Space Agency's Bepi-Colombo snapped them on October 1st as it zipped past the planet in a slingshot maneuver. You can read about the mission in this week's edition of The Downlink, The Planetary Society's weekly newsletter.

Mat Kaplan: The spacecraft will finally enter orbit around that hot and cold world in 2025. Stand down, Mars fleet. It's solar conjunction time, when earth is blocked from the red planet by the sun. I don't expect much work to get done until Mars comes out the other side around the 16th. NASA has successfully put the latest Landsat in orbit. Landsat 9 continues a 50 year tradition of earth observation by this series. Let's see. What else is happening? Oh yeah! Captain Kirk is going into space.

Mat Kaplan: The real Captain Kirk, you know, the original model William Shatner will be onboard next week when another Blue Origin New Shepard takes flight. Warp factor O let's say .00000000001. New additions of The Downlink every Friday at planetary.org/downlink. What does the chief engineer for mission operations and science do? I think you'll enjoy Marc Rayman's answer to that question. But first, you'll hear him answer a question that came from someone else.

Mat Kaplan: Marc has been dropping by Planetary Radio for a long time, beginning at about the time he became chief engineer and mission director for Dawn, the spacecraft that orbited and revealed both Vesta and Ceres in the main asteroid belt. Marc arrived at JPL in 1986 after working as a post-doctoral researcher with John Hall, co-winner of the 2005 Nobel Prize for Physics. Marc used much of what was learned from the Deep Space 1 Mission to make Dawn the enormous success it became, including reliance on ion engine propulsion.

Mat Kaplan: He's the only person to have received both JPL's Exceptional Technical Excellence Award and its Exceptional Leadership Award. Marc Rayman, welcome back to Planetary Radio. I realized just last week we had to have you on. This began when New York listeners set upon wondered why you left Dawn on orbit instead of attempting to land on Ceres. And I assume that [inaudible 00:03:32] was probably thinking of what Rosetta did at comet 67P, or better yet, looked back 20 years to NEAR Shoemaker's little bump down onto asteroid Eros.

Mat Kaplan: I wasn't surprised to hear from you soon after we talked about this on the show, but I thought that [inaudible 00:03:51] and other listeners might like to hear the answer directly from the mission director and chief engineer. So again, welcome.

Marc Rayman: Thank you, Mat. It's always fun to be here. As you know, I'm a regular listener to your show and I always enjoy it. Your shows are informative and fun. It's always a treat to be here and to discuss [inaudible 00:04:13] insightful question of why didn't we do this clever thing.

Mat Kaplan: I want to know. In fact, you've already told me, but we have to share this with everybody, but there's something else that's really eerily serendipitous about this. Tell me the anniversary that you just mentioned before we started recording.

Marc Rayman: You and I are having this discussion on September 27th, which truly by coincidence is the 14th anniversary of the launch of Dawn. It embarked on its mission from Cape Canaveral on this date in 2007. So that's a nice connection.

Mat Kaplan: I'll say, is this perfect or what? [inaudible 00:04:52] thank you for setting this in motion. I assume you were there at the Cape?

Marc Rayman: No, actually I was not. I haven't been there for the launches of my missions because I'm in mission control at JPL. As soon as the spacecraft separates from the launch vehicle, JPL takes over and that's where I need to be at launch.

Mat Kaplan: All right. Doing your job.

Marc Rayman: That's okay. I don't get to see the cool launch live, but I get to do other cool things. So that's okay.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, you think? Why didn't you just siddle up to Ceres the way we saw NEAR Shoemaker do in an unplanned rendezvous with that asteroid 20 years ago?

Marc Rayman: Well, the first thing I could say is, why didn't anybody think of this when Dawn was at Ceres? I mean, [inaudible 00:05:45] why didn't you send this suggestion to us? Maybe we never thought of it. But in fact, of course, we did. There are two parts to the answer, but part of it is contained in your description of series. Yes, in some sense, it's an asteroid, but it's a dwarf planet. That's an important distinction.

Marc Rayman: I think when people think of asteroids, they think of these small bodies like Eros, Ryugu, Itokawa, Bennu, Churyumov-Gerasimenko. I'm not saying that size is a measure of importance or interest, but still it's an important physical parameter and Ceres is not at all like those. There are millions, literally millions of objects in the main asteroid belt. 35% of the total mass is in dwarf planet Ceres.

Mat Kaplan: I love that statistic. That's just fantastic. Random space fact, as Bruce would say.

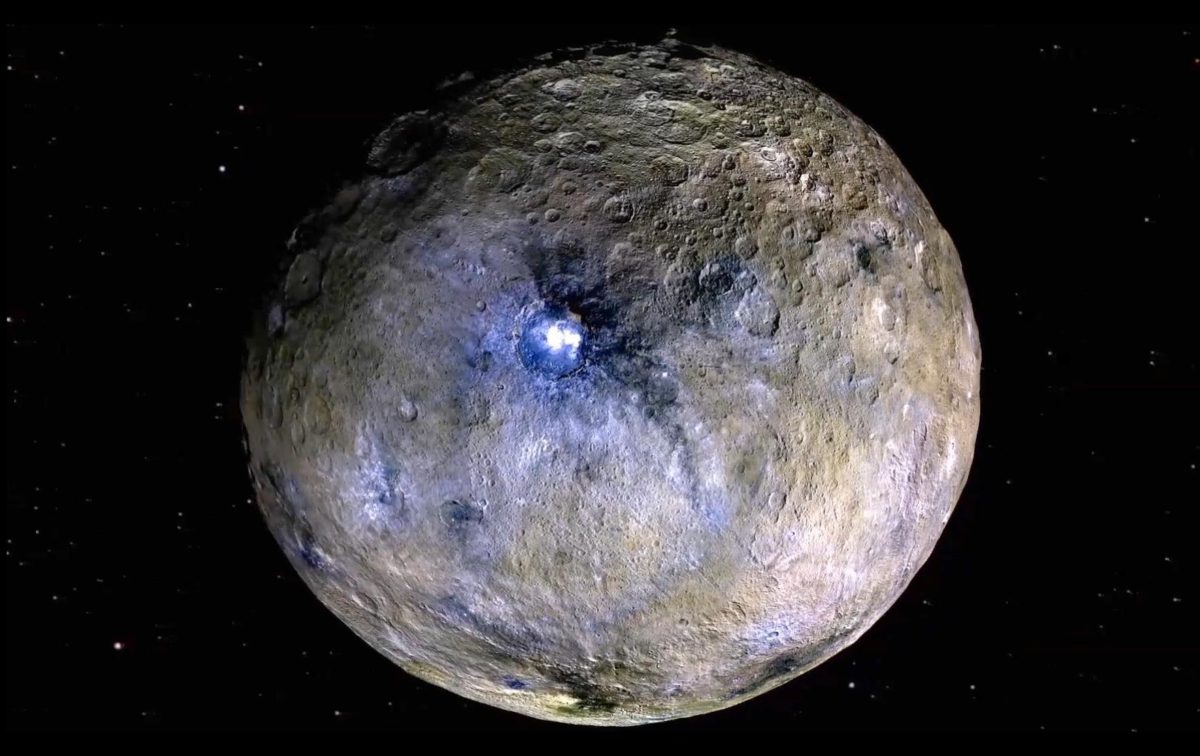

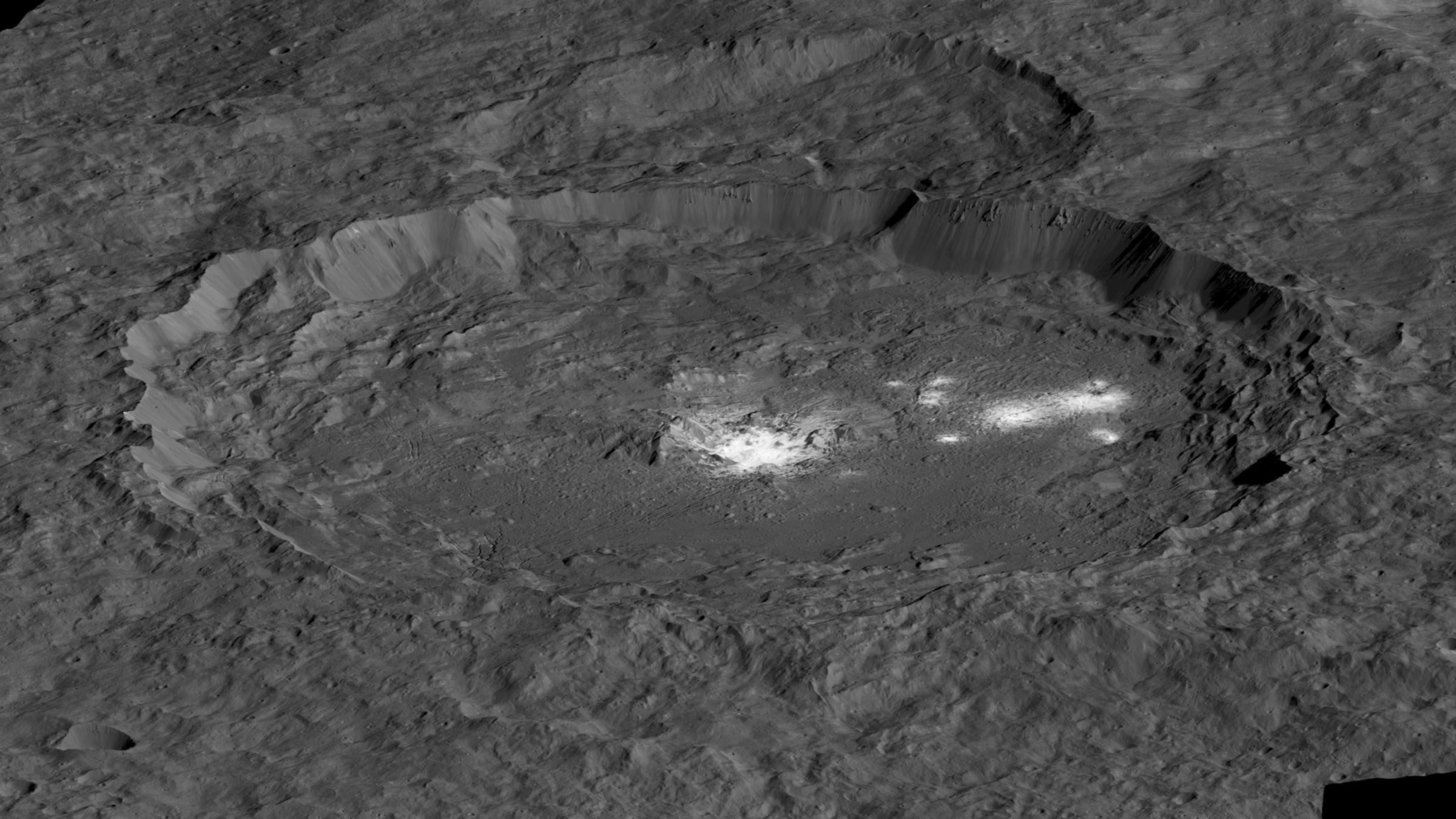

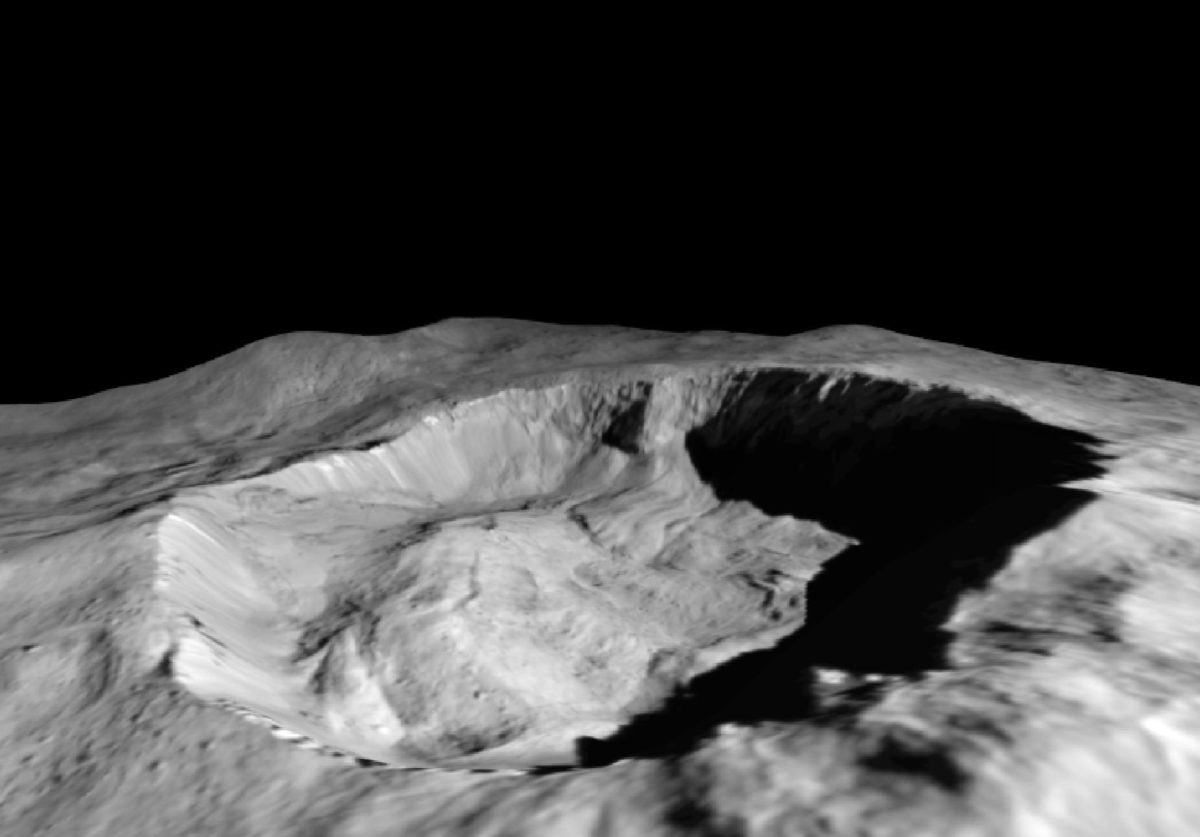

Marc Rayman: That's right, but this one wasn't random. It was... Well, what would you call it? A CCSF, carefully chosen space fact, maybe. Ceres is subject to planetary protection, which is a set of standards that NASA subscribes to, designed to ensure the integrity of extraterrestrial bodies, including this alien world Ceres. We were not allowed to let Dawn come in contact with Ceres because this exotic alien world was once covered with an ocean of liquid water.

Marc Rayman: We know from Dawn's exploration that it's still harbors a vast inventory of water. Most of it is ice, but there are some liquid still underground. It has a supply of heat. Dawn discovered organic materials and a rich inventory of other chemicals with all these ingredients. Ceres could have undergone some of the chemistry related to of the development of life and we don't want to contaminate that pristine environment with Dawn's terrestrial materials.

Mat Kaplan: Much like we saw Cassini end up crashing into Saturn instead of taking the chance that it would run into Titan or Europa or whatever. Sorry, not Europa, Enceladus.

Marc Rayman: We knew what you meant.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you.

Marc Rayman: But you're absolutely right. Our requirement was to ensure that Dawn would be in an orbit for at least 20 years, and preferably longer, would not change enough that Dawn would actually crash into Ceres even after the mission was for. Two decades is long enough. There's a common misconception here that I hear often, that the 20 years was so that the space environment would sterilize any microorganisms on Dawn. That's not at all the reason. 20 years is most assuredly not long enough to sterilize it.

Marc Rayman: Rather the requirement is intended to allow enough time for a follow-up mission. That is to allow enough time to conduct possible future biological exploration of this dwarf planet. Two decades is long enough that we could mount a mission to build on Dawn's discoveries and we wouldn't wanted to be misled by microorganisms or non-biologic organic chemicals that might have been deposited there by our spacecraft.

Mat Kaplan: That's one good reason. What's the other one?

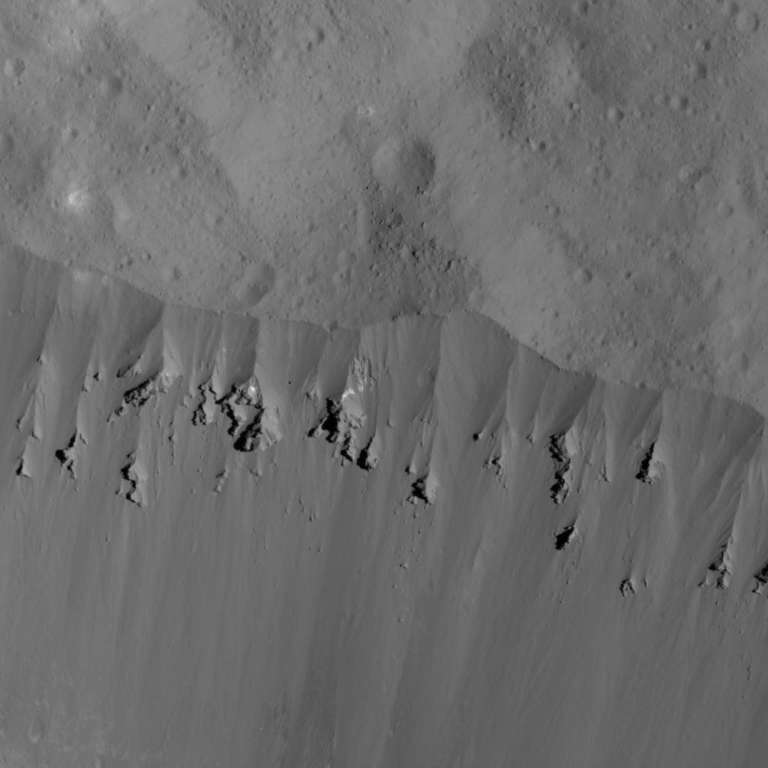

Marc Rayman: Well, the other one is Dawn was not physically capable of accomplishing a controlled landing. Once again, Ceres is not just one of these chunks of rock. It's a big place and its gravity is significant. Now, when missions like the ones you and I have mentioned, which I should say are incredibly cool missions, you and I and essentially everybody listening, we're all enthusiastic space buffs.

Marc Rayman: These other missions, which are super neat, which accomplish their landings or their contact with these bodies did so because the gravitational attraction was exceedingly low. It's much more like... That is for those missions. It's much more like when two spacecraft rendezvous in orbit. You think of a spacecraft flying up to the Space Station. The gravitational attraction is almost entirely negligible, not quite but very close. You just fly up next to the body and go from there.

Marc Rayman: Ceres' gravity was much too great for that. For reference, if Dawn had gone to a very low altitude orbit, even lower than we did, its orbital velocity would have been 800 miles per hour. Well, you can't just gently drop out of orbit like that. And even if we could have, you need a rocket engine to slow your descent, right? To make a controlled landing.

Marc Rayman: Well, Dawn had its famously efficient ion propulsion system, uniquely efficient actually, without which this mission would have been not just difficult, but truly impossible, would have been impossible with any other propulsion system. But as I think another one of your listeners wrote in, the thrust from the ion engine is comparable to what you would feel if you hold a single sheet of paper in your hand. One way to think of this is imagine you had a balance, a scale, where on one side, you have the piece of paper.

Marc Rayman: On the other side, you have Dawn's weight in the Ceres gravitational field. That weight would have been about the equivalent of about 50 pounds on earth. Well, the weight of a single sheet of paper is not going to be very effective against a 50 pound weight. On earth, of course, Dawn would have made weighed much more, but it wasn't at earth so that doesn't matter. Would have been 50 pounds in Ceres' gravitational field.

Marc Rayman: The ion propulsion system, which propelled Dawn from earth past Mars into orbit around Vesta, allowed us maneuver in orbit extensively at Vesta, break out of orbit, fly for another two and a half years to get to dwarf planet Ceres. Go into orbit around Ceres. Fly to 10 different orbits at Ceres. That ion propulsion system would've been totally ineffective in controlling the spacecraft's dissent to that intriguing alien surface.

Marc Rayman: It would not have been physically possible. But if not for those two reasons, sure, it would've been fun.

Mat Kaplan: And all of this, of course, goes along with the enormous success of this little spacecraft. Don't you like to call it the first true interplanetary craft, because it is still the only one to ever orbit two different bodies.

Marc Rayman: Right. As a detail, it's the only spacecraft ever to orbit two extraterrestrial destinations.

Mat Kaplan: Got you.

Marc Rayman: But once again, for all of us who were space enthusiasts, spacecraft have orbited two solar system bodies many times. Orbit the earth and then the sun, or the earth and then the moon. Even Mariner 9 and then many others after it orbited the sun and then Mars, but the sun, while it's an extraterrestrial body, wasn't an extra terrestrial destination.

Marc Rayman: Dawn is the only one that had the capability to go to a distant body, go into orbit around it, maneuver extensively, break out of orbit, and then go to another body and do that. Maybe that's more than you care about, but I think among space enthusiasts, these details are fun.

Mat Kaplan: They're just fun, they're impressive is all get out. It's also, of course, along the way after visiting those destinations, Vesta and then Ceres, the body that we've been talking about, doing tremendous science and returning all of those great images.

Marc Rayman: And a wealth of other data. But if I could just add, as long as we've mentioned Vesta, Vesta is the second most massive object in the main asteroid belt. Vesta and Ceres combined contain about 45% of the total mass in the main asteroid belt. Dawn single handedly explored a tremendous fraction of the mass, although of course, there's a great deal of diversity and other ways to characterize the nature of the asteroid belt other than just mass. But it's a fun bit of trivia. It's another carefully chosen space fact.

Mat Kaplan: What'd you say? CCSF. It's also an interesting way, again, to think about how very massive Ceres is even compared to number two, to Vesta, because you said Ceres on its own was 35% and Vesta only adds another 10% of all the massive, all those rocks out there.

Marc Rayman: And everything else is smaller and lower mass. But you're right. I mean, we've discussed this before. When Ceres was discovered and subsequently Vesta in 1801 and then 1807, they along with two other bodies in the main asteroid belt were described as planets. There were only four of them known until the middle of the 19th century. And then as science and technology advanced, more and more bodies started to be discovered in that part of the solar system, and eventually they were no longer called planets.

Marc Rayman: But you and I and most of the people who are listening grew up during a narrow window in human history when the planetary status of Vesta and Ceres had been forgotten, but Pluto still had planetary status. Now we're in a time where Pluto and Ceres and other bodies are collectively described as dwarf planets. And with the category of dwarf planets was defined, Ceres was the first body to have been discovered that fit that category because it was discovered 129 years before Pluto.

Mat Kaplan: Dare I ask, dare I drag you into the great debate, the planetary definition debate, which...

Marc Rayman: Mat, you can ask me anything.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. You could choose whether to answer or not. Seriously, seriously, do you believe that we need to go back to the old classification that would make Pluto a planet, but along with it bodies like Ceres?

Marc Rayman: I will answer the specific question you asked and then we can ramble from there. Do we need to? No, not at all. We don't need to because it's a matter of vocabulary. We could make intelligent choices of what the vocabulary, the terminology should be, but there's no need to. The universe is the way it is. We choose our terminology. Sometimes well. Sometimes not as well. And sometimes we don't choose it. Sometimes we allow it to evolve. The way I think of this is the following.

Marc Rayman: First of all, in 2006 when many people thought, "Oh my gosh, this is so awful. Pluto got demoted. Earth is an interplanetary bully. How could we be so inconsiderate? Poor Pluto's feelings. This was just terrible." The way I think of it is this was a wonderful missed educational opportunity to help people understand, again, that it doesn't matter how you want the universe to be. It is the way it is.

Marc Rayman: And our job as scientists, engineers, explorers, and communicators is to understand what that reality is and to find clear ways to communicate it. The underlying motivation for the debate about whether to call Pluto, and hence these other bodies like Ceres a planet or a dwarf planet, was because scientific knowledge had advanced, right? When Pluto was discovered now 91 years ago... It was discovered 1930.

Marc Rayman: This debate was in 2006. When it was discovered, it was the only body known in an orbit like the one it was in. But now we know of many, many, many bodies there. Let's not decide on the basis of Pluto's feelings, nor I think on the basis of the feelings of people who grew up during that time in new human history, but rather let's talk about it in terms of what is the modern scientific understanding of the nature of our solar system and others. And that's my answer.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you. Thank you. Good answer. We will provide equal time to the other side as we have often done on this show.

Marc Rayman: Although I'm not sure frankly what the other side is because I wasn't saying whether all of those bodies should be called planets or they should be called dwarf planets or something else.

Mat Kaplan: I think that your point that merely labeling them or relabeling Pluto as a dwarf planet didn't suddenly turn it into a munchkin. It didn't lose any stature. In fact, we now know from wonderful missions like New Horizons and Dawn that these minor worlds, these dwarf planets, are as fascinating as pretty much any place else we might want to go in the solar system.

Marc Rayman: Right. We should be careful about ascribing different kinds of significance to the name. It should have a good name. Your listeners won't be able to appreciate this, but look, this is a glass of water.

Mat Kaplan: And it's half full. That's how I see it.

Marc Rayman: It is or it's twice as big as it needs to be, right? But the point is, it's just a name to the now... There's a lot more to the body than the noun and the adjective that goes with it. Sorry.

Mat Kaplan: As long as we're going this long, Marc, you have a different job now at JPL, the Jet Propulsion Lab, chief engineer for mission operations and science, as I said up front. What does the chief engineer for mission operations and science do?

Marc Rayman: Mostly I just get to keep having fun getting involved in missions that are in operations, missions that are preparing for operations, missions that are, of course, doing science. JPL has so many exciting missions that it's, for me, just more of my life as a kid in a candy shop.

Mat Kaplan: Well, that's good. I'm glad you're having fun, and that's a great overview. But I mean, I assume this is allowing you to use your experience. You've been at this a long time to benefit people who are working on new missions that are constantly in development at JPL.

Marc Rayman: Right. New missions and not so new missions. I've spent a very enjoyable and significant amount of time recently working with the Voyager team. Because it, as you know, is in operations. You said I have a fair amount of experience. Much of the experience is mostly things like me saying, "Oh, this is so cool," but I do have some other experience as well.

Marc Rayman: Where missions might benefit from some of that experience, then I work with them either, again, while they're in operations or preparing for operations, because we want missions to have the best chance of success because all missions are challenging. But for ones that have some additional challenges, it's a great opportunity for me to get involved if you care. It's fine if you don't. To me, the coolest thing is getting to work on the missions. But I've done that for a long time.

Marc Rayman: And as you well know, I have very broad interests. You and I have discussed them right here in my space room at home together. And when I work on a project, I put all of my cognitive and energy into that project. That's great. It's wonderfully rewarding. In fact, my most gratifying professional experiences have been on projects. I even talked about that in my TED Talk. But at the same time, I feel like I miss out on the rest of the universe.

Marc Rayman: My biggest disappointment about my JPL career is that it interferes with my hobby of learning about and studying space exploration. Now that JPL has kindly created this position for me, because I didn't want to work on another project, so I get to be involved with more projects. Probably more than you care about, but that's how it came about.

Mat Kaplan: A lot of other questions and comments come to mind, including the fact that at another old friend of Planetary Radio Linda Spilker was back on the show not long ago. She is delighted. I mean, she's still Cassini project scientist, but she is now back on the Voyager mission, deputy project scientist for those two spacecraft, which are likely for a very long time to be the farthest out there, emissaries of humanity. Have the two of you crossed paths since you're working with Voyager folks?

Marc Rayman: We have, and it's been a delight. I'm as big a fan of Linda as you are, and it's been lovely to see her join the project. Looking forward to continuing to work with her.

Mat Kaplan: I'm glad you mentioned that TED Talk again, because we talked about it last week. I mentioned it and it didn't show up on the website, which I apologize for. But this time for sure... As Bill Winkel used to say, this time for sure. I think it's called If It Isn't Impossible, It Isn't Worth Trying.

Marc Rayman: Right. I mean, let's be realistic. That's sort of a grabber. Maybe now that you've mentioned it enough, people will be grabbed that they'll listen to it. You can find it at tinyurl.com/tedmarc or at the Planetary Radio webpage.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, on this week's episode page at planetary.org/radio. I'll just mention one more thing because you point it out to me not too many days ago that that wonderful tour you provided some years ago of your home, which is a bit of a space memorabilia museum and library as well, that that video had somehow become private. It is available again. We'll put that link up as well so that people can see that amazing collection you have, which I'm guessing has grown since I was last there.

Marc Rayman: It has. But let's be clear, you made the video and you made the video fun.

Mat Kaplan: Oh good. I'm glad. Well, I try only to talk to fun people because that makes it a lot easier for it to come off that way. Thanks, Marc, for being a fun person to talk to for a long time, fun and informative. If we get a nice statement of gratitude from [inaudible 00:26:37] I will pass that along as well.

Marc Rayman: Good. Well, as always, it's a pleasure to talk with you and with your listeners. I will listen to this show as I do all of them.

Mat Kaplan: That's MarC Rayman, solar system Explorer, scientist, engineer. His title now at JPL, NASA JPL, is Chief Engineer for Mission Operations and Science. I'll be right back with Bruce who is standing by with his LightSail report and much more.

Bruce Betts: Hi, again, everyone. It's Bruce. Many of you know that I'm the program manager for The Planetary Society's LightSail program. LightSail 2 made history with its launch and deployment in 2019, and it's still sailing. It will soon be featured in this Smithsonian's New Futures exhibition. Your support made this happen. LightSail still has much to teach us. Will you help us sail on into our extended mission? Your gift will sustain daily operations and help us inform future solar sailing missions like NASA's NEA Scout.

Bruce Betts: When you give today, your contribution will be matched up to $25,000 by a generous society member. Plus when you give $100 or more, we will send you the official LightSail 2 extended mission patch to where with pride. Make your contribution to science and history at planetary.org/sailon. That's planetary.org/sailon. Thanks.

Mat Kaplan: Time for what's up on Planetary Radio. Here's the chief scientist of The Planetary Society. He is also the program manager for LightSail, LightSail 2, that is still orbiting above us right now. Welcome. How is that great bird doing?

Bruce Betts: The great bird's doing very well in general. LightSail 2 still orbiting, flying, two and third years into the mission, something like that. We have things that go well and things that don't go as well. We had a power outage that shut down our ground systems and caused little software hiccups. We're still recovering from that, but we're getting data again from the spacecrafts. Spacecraft is fine and healthy and happy.

Mat Kaplan: I was just reading, because I'm going to be talking to people in charge of the Lucy mission next week on next week's show. They've put a plaque on the spacecraft, because it's going to be orbiting for possibly tens of thousands of years. Maybe we should have done that with LightSail. It just seems to keep going.

Bruce Betts: Oh, well, we do have a mini DVD on there.

Mat Kaplan: That's true.

Bruce Betts: It has all the members' names and people who signed up and selfies from space and all sorts of good stuff. But yes, LightSail 2 is the spacecraft that keeps going and keeps staying up. Now we're starting some degradation of the sail over time from the space environment. But we actually over the summer had the best sailing we've had so far because of changes and modifications and things we've learned.

Bruce Betts: We actually gained altitude for a while a little bit, and now we're back in the drag pulling us down, but we keep fighting and sailing and keep learning.

Mat Kaplan: Sail on! Tell us about the night sky.

Bruce Betts: All right. Well, besides LightSail, which usually is not very bright, the evening sky is really cool, Mat. Have you been checking it out?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, now and then. Been too cloudy and rainy and even thundery down here the last few days, but it's been beautiful nevertheless.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, we had weird thunderstorms last night, but that's not important. What is important is when you don't have clouds. Venus super bright over in the West after sunset. It's that really bright starlike object. And then over in the East, rotate yourself towards East and you'll see another really bright starlike object. That's Jupiter, and to Jupiter's right is yellowish Saturn. We got the moon wanting to come and play. The crescent moon hanging out with Venus on the ninth, looking lovely.

Bruce Betts: Red Antares, Antares is the reddish star in Scorpius, lining up with Venus and the moon on the ninth, but then lining up in general with Venus and hanging out near it for the next week or two. The moon then gets up to hang out with Jupiter and Saturn around the 14th

Mat Kaplan: So much to see. That's wonderful. Thank you.

Bruce Betts: It's good stuff. Some interesting things as well in this in space history. 1959, Luna 3 became the first spacecraft to take pictures and return them, pictures of the far side of the moon, our first mediocre views, but the first views of the far side of the moon.

Mat Kaplan: Quite a milestone when you think how long humans have been looking up at that single side of the moon, that one hemisphere. It took that long. Nice work the Soviets did way back then.

Bruce Betts: Indeed. They also did in 1964 with Voskhod 1, which I'll come back to in just a moment. Voskhod 1's mission was this week in 1964, which leads us to random space fact.

Mat Kaplan: [Russian 00:31:53]

Bruce Betts: [Russian 00:31:55] Voskhod 1 in 1964 was the first space mission with more than one person aboard. Hurray! There were three, rather than two as originally designed for apparently due to political pressure. They also had the distinction of becoming the first to fly without spacesuits because there wasn't room for them.

Mat Kaplan: Gosh. I don't even want to think about this. I mean, all I have to do is look at how they cram three people into [inaudible 00:32:30] now and think what? It was even tighter than that? Oh my!

Bruce Betts: Yeah. There's just a lot of intriguing things with Voskhod 1 that we will come back to even more in just a few moments. But first, let's go to the previous trivia question. I asked you the somewhat challenging question, what currently functioning Mars orbiter has the longest orbital period? How did we do, Mat?

Mat Kaplan: You know what was surprising this time is how many people got it wrong, at least by the determination that I believe you made. I would say half of the entries said Mars Express or the Emirates Mars, mission Hope, even some that went to like Maven and things like that, which I guess has a fairly eccentric core. But here's the answer we got from Martin Hajosky, MOM, the Mars Orbiter Mission from India, also known as Mangalyaan, with an orbital period of 72 hours, 51 minutes and 51 seconds.

Bruce Betts: That is correct. It is significantly longer than everyone else, although the Hope mission is also in the really long category of 55 hours, but everyone else is pretty much under say eight hours.

Mat Kaplan: I would say Hope definitely came in second, and a lot of people did note that also long orbital period. But yeah, couldn't touch MOM. Congratulations, Martin. I know how that sounds. Wait, there's more. It has been almost four and a half years since Martin, who regularly enters the competition, has won the contest by my records. Again, congratulations and we are going to send you, Martin, a Planetary Society kick asteroid rubber asteroid. We're going to send it to Texas.

Mat Kaplan: Why not? That's where he lives. This is cute. He says, "Heads much farther away from ours each time around, allowing it in a sense to watch over the other seven functioning Martian orbiters. Exactly what you might expect MOM to do."

Bruce Betts: I never thought of it that way. Yeah, yeah, that makes sense.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, similar response from Kent Merley in Washington, "Like my mom, she swoops in every 72 hours for close inspection. And while slowly stepping back out, claims not to be judgmental." Finally, we'll just do one poem this week. It's a fairly long one from Gene Lewin in Washington. You need to know up front that SHAR, S-H-A-R, that's the Sriharikota range in India, and it's where the MOM mission was launched by the Indian Space Research Organization. Here's the poem.

Mat Kaplan: To Basum from the Bengal Bay, Mangalyaan left from SHAR, achieving orbit on its first attempt. The ISRO has set the bar. This mission plan for just six months continues to this day, traveling around the crimson orb. MOM still has things to say. Its orbit takes about three days, well, three and a skosh more, around the fourth rock from the sun named for the God of War.

Bruce Betts: Impressive.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Nice work, Gene. Thank you very much. We are ready to move on and this is going to be something special in more than one way

Bruce Betts: From my side of special, here's a question, what major political event in the USSR happened during the only 24 hour long Voskhod 1 mission? A major political event in the Soviet Union occurred during Voskhod 1 mission while it was in space. Go to planetary.org/radiocontest.

Mat Kaplan: You said this was in 1964?

Bruce Betts: Yes, 1964.

Mat Kaplan: All right, everybody. Here's the other special thing about this contest. You have no excuses because I'm going to be going on vacation and therefore we have to...

Bruce Betts: What?

Mat Kaplan: Yes, I've earned it.

Bruce Betts: All right.

Mat Kaplan: We have to mess with the contest somewhat. You're going to have not one, not two, but three weeks to respond to this one. You have until Wednesday, October 27 at 8:00 AM Pacific Time to get us the answer to this one and win yourself, what else, a beautiful, safe and sane rubber asteroid.

Bruce Betts: Excellent. Well, have a lovely vacation, Mat, when that happens.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you. I'm really looking forward to it. It's been a long time since I've been away for... This'll be just short of two weeks. There's a lot of stuff to get ready before then, but boy, is it going to be fun.

Bruce Betts: All right. Make sure you let me know what I need to pack.

Mat Kaplan: Wait a minute. Hey, honey? Oh, no. I'll tell her later. It's okay.

Bruce Betts: She'll be so happy.

Mat Kaplan: Say goodnight, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody. Go out there and look up for the night sky and think about what you'd pack if you went on vacation with Mat Kaplan. Thank you and good night.

Mat Kaplan: Hey, honey. Put a couple of extra cans of coffee in there. Anyway, he's Bruce Betts, the Chief Scientist for The Planetary Society who joins us every week here for what's up.

Bruce Betts: Cans?

Mat Kaplan: Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California and is made possible by its members who don't mind revolving around any world. Take a spin with them at planetary.org/join. Mark Hilverda and Jason Davis are our associate producers. Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Pieter Schlosser. Ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth