Planetary Radio • Dec 30, 2020

Planetary Society All-Stars Review 2020 Space Milestones

On This Episode

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Casey Dreier

Chief of Space Policy for The Planetary Society

Kate Howells

Public Education Specialist for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

Chief Scientist Bruce Betts, Editorial Director Jason Davis, Chief Advocate and Senior Space Policy Advisor Casey Dreier, and Communications Strategy and Canadian Space Policy Advisor Kate Howells join host Mat Kaplan for our annual look back at the closing year’s accomplishments in space exploration. They also predict 2021’s biggest events on the final frontier. A very cool prize awaits the winner of the new What’s Up space trivia contest.

Related Links

- Your Guide to Crew Dragon's First Astronaut Flight

- LightSail

- Defend Earth

- Artemis: NASA’s human lunar exploration program

- Chang'e-5: China's Moon Sample Return Mission

- Your Guide to Hope, the United Arab Emirates' Mars Mission

- Your Guide to Tianwen-1

- Your Guide to NASA's Perseverance Rover

- NEA Scout unfurls solar sail

- PlanetVac

- The Downlink

Trivia Contest

This week's prizes:

A cool device called Time Since Launch (TSL) from CW&T. Pull the pin and it begins counting up to 2,738 years.

This week's question:

How many crewed launches to space were there in 2020?

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, January 6th at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

What is the approximate ratio of the average density of Jupiter to the average density of Saturn? In other words, how many times denser is Jupiter than Saturn?

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the 16 December space trivia contest:

In what feature is the lowest point on Mars?

Answer:

The lowest point on Mars is in the vast Hellas Planitia impact basin.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: Planetary Society All-Stars Look Back at 2020 this week on Planetary Radio.

Mat Kaplan: Welcome, and happy new year, everyone. I'm Mat Kaplan of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. It's a tradition, four of my colleagues are here with a review of the past year and a look ahead. 2020 wasn't so bad once you got off the surface of our world. Bruce Betts is part of this quartet. He'll stick around for the last What's Up before 2021. We'll offer one of the coolest prizes ever in the new Space Trivia Contest. Here's the program note.

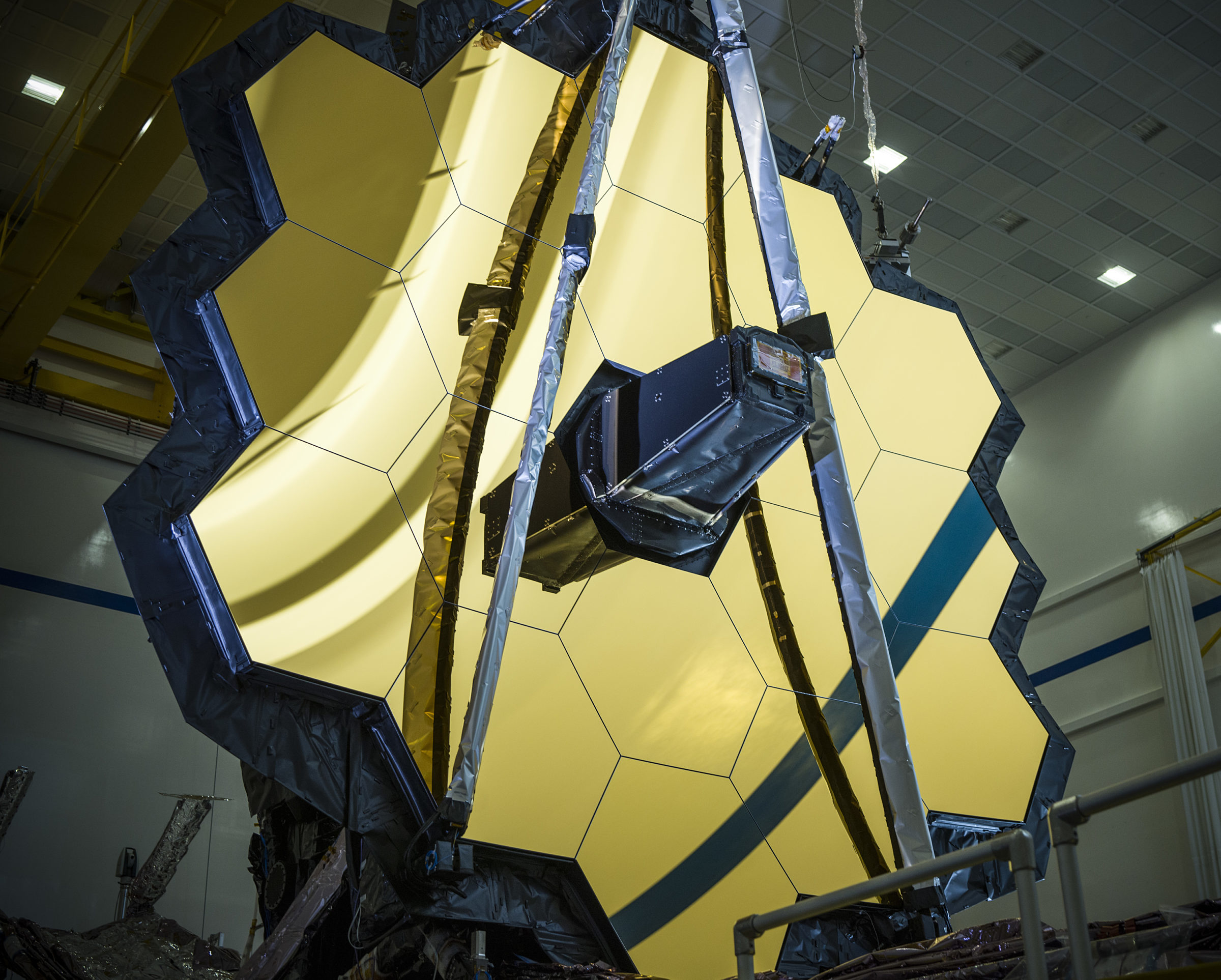

Mat Kaplan: In view of the holiday, Casey Dreier and I have decided to push the next Space Policy Edition show from new year's day to the following Friday, January 8th. I hope you'll join us. I also want to thank each of you who has given us a review or a rating in Apple Podcasts or elsewhere. Also, for your many wonderful holiday greetings, they are much appreciated. The December 25 edition of The Downlink, The Planetary Society's weekly newsletter, shares a very cool image of the James Webb Space Telescope. The giant eyes multi-layer sunshield was successfully deployed for the last time before its planned launch in October of 2021.

Mat Kaplan: You'll hear more about the JWST later in the show, along with what China's Chang'e 5 will be up to now that it has dropped off its collection of lunar material, the spacecraft might become a solar observation platform. The Planetary Society is celebrating NASA authorization for the missions that will bring samples from Mars to earth. You'll hear us talk about this major story as well in the next few minutes. Details and more are on planetary.org/downlink. I'm lucky to work with some of the smartest, most passionate people on the planet.

Mat Kaplan: Each of them is dedicated to the mission and vision of The Planetary Society. You've almost certainly heard from four of them in earlier Planetary Radio appearances or elsewhere, but we've never before gathered for a plan rad conversation. We had a lot to talk about. Here's our new year's present for you. Bruce Betts is The Society's chief scientist. Jason Davis is our editorial director. Casey Dreier is chief advocate and senior space policy advisor, and Kate Howells is our communication strategy and Canadian Space Policy Advisor.

Mat Kaplan: Let's start with what is probably the thing that made the most news in this year of 2020. Jason, I would guess that that was SpaceX flying humans up to the ISS.

Jason Davis: That was definitely the most memorable moment for me personally. I think in terms of general news, it really caught a lot of the public's attention. This was the first crewed orbital space flight and the first commercial flight to the ISS on SpaceX's Dragon vehicle, that was Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley. They launched in May, came back in August. That was a pretty exciting moment. It was also, just from a programmatic standpoint, a huge milestone for both SpaceX and NASA. It paves the way to have more people on the International Space Station at any given time. They've already done a second launch at this point and a full fledged crew is up there now. So, pretty big moment in 2020.

Mat Kaplan: Kate Howells, as our international representative, is this something that made as much of a splash elsewhere around the world as it did here in the USA?

Kate Howells: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, every time American astronauts do something spectacular, the rest of the world pays attention. We saw this in the Apollo program. It wasn't just Americans landing on the moon, although perhaps in the States, that was the perspective, but everywhere else, we saw it as humans landing on the moon. Likewise, this advancement in commercial space flight is very important for everybody around the world who's interested in getting people out into space. Plus, on a practical level, having more spacecraft that can take people into orbit and bigger spacecraft that can carry more people. That opens up spots for international astronauts to fly to the ISS as well, so that's good for everybody.

Mat Kaplan: With a Canadian scheduled for an upcoming flight, right?

Kate Howells: Indeed, yes. Well, upcoming a little ways in the future.

Mat Kaplan: Casey, certainly not a new topic for us on the Space Policy Edition of Planetary Radio, but this really says that something is paid off, right? It was a big gamble.

Casey Dreier: It was. We can go back 10 years. There was a big policy fight about whether to go all in on commercial crew as a way to replace the capability loss from the shuttle. This was the Apophis of that gamble, or that effort, was to send people into space using this new way of doing business. Even more importantly, I would add the second flight, the first operational flight that launched six months later right on time, seems to be doing perfectly well with a full crew compliment of four astronauts, including one Japanese participant going up to the International Space Station, to add on what Kate was saying.

Casey Dreier: This is a big deal policy-wise. It proved this new way of doing business with commercial partners. It also reduces US reliance on Russia to get to its own space station. That will fundamentally, I think, change the dynamic between the US and Russian space programs, and particularly for the Russian space program, which has benefited financially, significant financial assistance from the US in order to maintain this launch capability to the Space Station. So, they're going to have to really reevaluate and reconsider how they are going to fund their own program.

Mat Kaplan: Follow up on this, Jim Bridenstine, on this show, and I'm sure elsewhere, said that we will see more American astronauts on Soyuz flights, Russian flights, even with him flying up on crew Dragon, and soon the Boeing spacecraft. Does that still look like it's going to happen? Do we have American scheduled for Soyuz flights?

Casey Dreier: They want to maintain a large set of options, right? If there's a failure in any one launch system, you don't preclude access to the station. This is why they always wanted to have at least two commercial providers, and then I think it will depend on the overall relationship between US, and Russia, and space agencies to continue that relationship going forward as well.

Mat Kaplan: Lots of stuff going on in low earth orbit. I think we're all to be congratulated for not leading with this next topic since it is the one that is nearest and dearest to all of us. Bruce, how is LightSail 2 doing?

Bruce Betts: It's doing well. It's still flying around up there. We're trying to keep sailing and learn from what we're doing as we go around the earth. We are gradually coming down as we expected, but very gradually coming down due to drag from what little atmosphere is up there. We're taking all sorts of pictures to record, not only the engineering of the sail and the booms, but also pretty pictures that are inspiring and keep the idea out there that solar sailing is a viable propulsion technique for the future, including for small spacecraft like CubeSats, which is what we've demonstrated for the first time.

Mat Kaplan: Remind us of a couple of things. Where can people see the pictures and follow along with the mission?

Bruce Betts: sail.planetary.org.

Mat Kaplan: That's easy. Okay, here's the second one. It's pretty much steering itself now, right? How much human intervention is there in what LightSail 2 is up to?

Bruce Betts: It's always executing the commands automatically, but we're up linking the commands. So, there's actually a fair amount of interaction in terms of uplink and downlink and planning different activities, and trying to figure out the standard, you get a glitch here, you get a glitch there, why to do this, how's our performance over time, which is gradually degrading as batteries, the rechargeable batteries. So, just like any rechargeable batteries, they're getting less and less efficient, so we're having more to think about power and the like. Daily, we communicate with it, or at least we try to, usually a few times a day, but in terms of executing imaging, executing turns, that's all automated for any given 24 hour period.

Mat Kaplan: What's the outlook? Weeks, months, decades to go?

Bruce Betts: It's at least months. At the rate it's going, it's hard to predict because the atmosphere varies and also we're flying something that people haven't flown up at that altitude. So, we're actually learning something from how long. It is staying up there, much longer than predictions originally. Partly that's due to solar sailing and partly it's to the complexity of modeling a big shiny sail in a low mass spacecraft.

Mat Kaplan: Jason Davis, it would seem that LightSail 2's legacy is assured because we see its influence over other upcoming missions.

Jason Davis: Yeah, it's funny, I was watching a video of our event for the LightSail 2 launch in Florida. Dave Spencer, the project manager, David mentioned that a lot of people ask about LightSail 3. He said in this video I was watching, he always points to NEA Scout, and this is a NASA's Near-Earth Asteroid Scout mission. It is a small CubeSat mission, just like a LightSail 2. It's about double the size of LightSail with a core which is still pretty small for the spacecraft itself. It has a bigger sale as well.

Jason Davis: If all goes well, it will launch in 2021. So, we'll actually get to see a fly. It'll go on the maiden mission of the Space Launch System, which is sending the Orion capsule out to the moon and back, and there's a little flotilla of CubeSats there, NEA Scout will pop off. It's going to use its solar sail to actually leave lunar orbit and go visit a Near-Earth Asteroid, do kind of a slow fly by. It really is a beautiful add on to the LightSail 2 mission. There's a Space Act agreement between the folks working on that mission at NASA and The Planetary Society, so there's a lot of information exchanged.

Jason Davis: That'll be really neat to see, and a good demonstration of how these little missions can do some actual science using both small spacecraft and solar sailing propulsion. But then, we just got word at the end of the year, or near the end of the year here, that another NASA mission was just approved called Solar Cruiser. It's slated for launch in 2025. The same principal investigator, Les Johnson at Marshall Space Flight Center, he's going to be working on that one as well. This is an even bigger sale, 1700 square meters.

Jason Davis: It's going to fly out to the L1 point, and that's this point between earth and the sun, where the gravity kind of balances in a way that lets your spacecraft orbit one an imaginary point in space without using too much fuel. It's going to do some really neat orbital maneuvers out there that you'd only be able to do with solar sailing. We're going to have a lot more cool stuff on that to come out in January, but you heard it here first, the plan rad sneak peek. It's really neat. I think all of us are just really excited to see these future missions that just are taking the technology a step further and building on LightSail 2.

Mat Kaplan: You're going to see Les Johnson or hear Les Johnson returned to planetary radio before long, the PI for both of these upcoming sale projects and other coverage that will be coming from Jason at planetary.org. Casey.

Casey Dreier: I just want to emphasize here, and I'm pretty sure this is correct, so Bruce jumping in and correct me if I'm wrong. But LightSail is still the only successful spacecraft that has been funded through Kickstarter and through people, right? No other spacecraft has launched that has gone through a Kickstarter process. All those other projects did not launch, and probably don't exist anymore. I just want to emphasize that good job all of you listening who funded LightSail because you backed the right horse. You trusted us on this and we got you into space, and it's still going.

Bruce Betts: As far as I know, that is quite correct. We should always thank and mention over 50,000 people between Kickstarter and other methods donated to support LightSail, and that's entirely supported by those people from over a hundred countries around the world.

Mat Kaplan: I think that we've fulfilled the innovation portion of The Planetary Society mission with LightSail and more in 2020, but another big part of that is planetary defense. Casey, we'll stick with you. What's the status of defending our planet?

Casey Dreier: Well, Mat, I don't know if you notice this year, but there was this thing, a global pandemic that was happening.

Mat Kaplan: I don't know. I haven't left the house much, so I probably missed it.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. For some reason, I didn't leave the house much either this year, but there's an interesting relationship between those two things, right? A global pandemic as a high impact, low probability event. They occasionally happen. We know that they occasionally happen, but we don't exactly know when they will happen. This year, we got the short straw and we had the global pandemic. We've learned a lot. We've seen various countries react in different ways, and we've seen the value of the countries that have gone through similar scares in the past, particularly in the Asia Pacific region who are much more set up to manage the consequences and public health needs of a sudden exponentially growing virus.

Casey Dreier: There's a lot of things that we can take from coronavirus and apply it to planetary defense in terms of how we approach this as a problem. That was this fundamental relationship that we made to this upcoming Decadal Survey Process, which is from the National Academy of Sciences here in the United States. We're saying like, look, there is no example of a higher impact event than an asteroid collision. Just like with viruses, you have to make sure you're looking ahead to see, are there dangers coming your way?

Casey Dreier: Do you have ways to inoculate or to rapidly create the equivalent of vaccines, AKA planetary defense, or being able to change the course of an asteroid? Do you have the technology ready for that if a threat arises? And how do you manage the public response to that? What we've seen from coronavirus is that we are woefully unprepared for a serious threat from planetary defense. We've definitely made progress over the years in finding new Near-Earth asteroids. In fact, one of our Shoemaker Grant fellows found a new kilometer sized one, that we'd almost found all of this year, but there are tens of thousands of smaller ones that still pose a threat that we are not able to look for because we don't have basic things like a space-based telescope.

Casey Dreier: NEO surveyor mission that we're trying to support this year. The Planetary Society has been really kicking up its advocacy for planetary defense. We see a lot of general support for it and we really need to turn that general support into specific action, get our space-based telescope, NEO surveyor out there looking for these things. We need to continue our ground-based observations, and we need to be really investing in deflection technology. We're seeing a step forward with that, with the dart mission that should launch next year, very exciting mission, but we need to be thinking bigger and longer term, and of course, in an entire government and global sense of how we organize these things, and that's an ongoing process that we will continue to support.

Mat Kaplan: Kate, it's called planetary defense, not United States defense or UK defense or anything else that would be specific to any one nation. What is the general feeling across the world? Are we getting through to people around the world as well as in the United States about the importance of this?

Kate Howells: Yeah, that's a good question, and I loved Casey's analogy to the pandemic because similarly, if there is an incoming asteroid, it's going to take a ton of global collaboration and coordination to deal with it because this is never going to be a really localized event, even if it's a small enough astroid that the physical damage is localized. There's still going to be huge repercussions globally. Coordinating around the world is super important, and raising public awareness around the world is also super important.

Kate Howells: Among our members who are distributed around the world, we do see a lot of support for planetary defense initiatives. We get great participation whenever we're raising funds and awareness for the Shoemaker Grant program. We have resources in our action center on our website where people can go and get tools to teach others in their community about the asteroid threat and what can be done about it, but there's always more work to be done because I think, for the most part, people who aren't already members of The Planetary Society and hearing all the things that we say all the time, I don't think people really are aware of the reality of the asteroid threat.

Kate Howells: I think it seems more like something out of science fiction. Speaking of which, there's an interesting LightSail connection. I was doing some very important research over the holidays for an article that I'll be writing soon. I had to watch the movie Armageddon for this very important research. I found that, in one of the scenes where NASA is floating ideas of what they can do about this incoming asteroid, they suggest a solar sail as a way of shifting its course, so I thought that was kind of cool, worth mentioning, it all comes back together.

Kate Howells: But anyway, it's our job to take this from being in the realm of science fiction and movies and into reality for people and drive home that this is a real threat that people can do something about. I think there's going to be a really interesting opportunity with the Apophis fly by which I'm hoping Bruce can talk a little bit more about, but I think that's going to be a really cool opportunity to get the public more aware of the reality of asteroids and channel that awareness into advocacy and action.

Jason Davis: I also did some important Bruce Willis research this holiday season, but I was watching Diehard because that is a classic-

Casey Dreier: That's a Christmas movie.

Jason Davis: Classic Christmas movie.

Mat Kaplan: Too far fetched.

Kate Howells: I'm sure there are applications you can find to our work as space [crosstalk 00:18:10].

Jason Davis: Yes.

Kate Howells: I'm sure there's a connection.

Mat Kaplan: Bruce, you just were a virtual attendee at an Apophis workshop, were you not?

Bruce Betts: I was, and we had hoped that Hans Gruber would give one of the talks, but apparently someone let him go.

Casey Dreier: [crosstalk 00:18:25] disposed.

Bruce Betts: Sorry. Yes, I participated. Casey and I had a presentation at the Apophis T-9 Years nine years workshop. Apophis is a roughly 300 meter asteroid that would cause massive regional damage if it impacted. Good news, not hitting in 2029. Better news, flying by closer than our geostationary satellites. Will be visible from Europe and Africa with the naked eye. We basically were emphasizing this is an opportunity to do exactly what Kate said, which is to raise awareness of the asteroid threat and what we're doing about it and integrate it into advocacy and all sorts of things. That was a good experience.

Casey Dreier: This is a perfect opportunity to say, can we scramble and send a series of small missions to Apophis as it flies by? This is a perfect way to integrate new technologies with small SATS, with a rapid public private partnerships, and with university consortiums to say, what can we do on a small scale on a fast pace to better understand something if it's going to be coming by us? Notably, I think it's important. You do this without altering its trajectory so it doesn't inadvertently come and hit us later. But it's a really great opportunity to say, these things whiz by as all the time. Again, this is a Rick Binzel's from MIT's classic phrase, "Right now we've depended on luck for all of human history, not to get hit by one of these, but luck is not a plan."

Mat Kaplan: Bruce, you want to say another word about this round of Shoemaker funding, Shoemaker NEO Grant funding?

Bruce Betts: For 23 years, we've been doing the Shoemaker NEO Grants, Near-Earth object grants funding, mostly really advanced amateurs around the world to upgrade their telescopic systems, to do mostly critical follow-up observations to find orbits of asteroids. Then also do characterization, whether it's one asteroid or two asteroids comes out of things like these observations. This year, we had six grant winners over the course of the program. We've now given about 60 grants to roughly 20 countries around the world, funded about a half million dollars.

Bruce Betts: This year, we also had kind of an interesting thing that Casey to, which is at Leonardo Amaral, who's one of our recent winners in Brazil actually discovered a one kilometer asteroid, and that is rare these days to find them at all. They've been mostly found. Typically, they're found first by the professional surveys, but the advantage that Leonardo has, and part of the appeal to funding him, is he's in the Southern hemisphere in Brazil and was able to see a part of the sky that the professional surveys currently can't see.

Mat Kaplan: Congratulations, once again, Leonardo, and to all of you members of The Planetary Society who are making these discoveries possible. Who knows, we might just save the world, as the boss likes to say, my colleagues and I will be back with more about the year in space and our view of 2021 and beyond. This is Planetary Radio.

Kate Howells: Hi, I'm Kate from The Planetary Society. For all its troubles, 2020 has still seen some terrific space accomplishments. We asked our members and supporters to vote for their 2020 favorites. You can see the results at planetary.org/bestof2020. We're talking about the best solar system image, the most exciting moment in planetary science and much more. That's planetary.org/bestof2020. Happy holidays from The Planetary Society.

Mat Kaplan: Let's do something that no other humans have done for nearly 50 years now and head for the moon. Casey, Artemis, there were supposed to be a big test, right? A big noise down South. Is that happening?

Casey Dreier: The Green Run, the static fire test of the first stage of the Space Launch System rocket has not yet happened as we are recording this. We seem to be getting closer to it, maybe as methodically as we will, maybe perhaps never approach it at this rate. Frustrating. Jason and I were just talking about how we were down there at Mississippi Stennis Space Center four years ago now, a little over four years ago.

Jason Davis: Yeah. 2016, I believe. Yeah.

Casey Dreier: They were talking about doing the Green Run the next year, 2017. They were building all this ... This is a big, huge infrastructure effort, very complicated. They're running into a number of things. It's designed to find the problems, right? It's okay to find problems, but the Green Run hasn't happened yet. It seems to be imminent. If everything goes okay with that, then they are set up to do the first uncrewed test flight of the Space Launch System in Orion next year.

Mat Kaplan: What about the HLS? The human landing system got short shrift recently, didn't it?

Casey Dreier: Yeah. When we talk about Artemis, it's a number of things. They took the existing programs of the SLS and Orion. Those predated Artemis, those are almost 10 years old now. Orion's even older. It's 15 years old, and they call that part of Artemis because that's what you send humans to the vicinity of the moon with. You have the Gateway, space station still moving forward. It was hitting its own series of issues and delays. Then, of course, to land on the moon, you need something to land on the moon with. Right now, they're taking the lessons of commercial crew in low earth orbit and testing it, trying it out to say, can we do the same types of partnerships to land on the moon?

Casey Dreier: No one knows that this will work by the way. We don't know where the proper realm of public private partnerships is. We've only done a few of them. It could work. It'd be great. It could also not work. What they're trying to do is right now have three different companies or consortiums of organizations that NASA is partnering with to develop lunar landing systems for humans. NASA had requested this year, in the final year of the Trump administration, to spend about three and a half billion dollars on that project in 2021.

Casey Dreier: Congress ultimately gave them 850 million, so about 25%. Now we can say for sure right now that the president signed this into law, not happening in 2024, there's no possible way we can get a human landing system ready funded at that level, no matter how deep pockets are with Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk in three years, three and a half years. Basically, congress did not really believe or was not convinced that it was worth the money now to spend on those systems. In the same vain though, if you think about it, this is another chunk of money for lending people on the moon, which has not been a project that has had money spent on it since the 1960s.

Casey Dreier: It's still important, but we need to have a realistic timetable, and that's what the new Biden administration will get to decide.

Mat Kaplan: NASA has also proudly trumpeted the international collaboration that is shaping around Artemis. Kate, your nation, Canada, big part of that, but many others as well.

Kate Howells: Yeah, I mean, from a Canadian perspective, it's very exciting. Just a couple of weeks ago, we announced a treaty between the Canadian Space Agency and NASA to have Canada contribute another Canadarm, which famous in Canada, at least we love it, the Canadarm, we had those on a space shuttle and on the international space station, it's this fantastic robotic arm that facilitates all kinds of critical functions for these spacecraft. We're going to be contributing one of those to the Gateway. This will also help, whenever the Gateway is not occupied by astronauts, the Canadarm3 will be able to autonomously perform its function.

Kate Howells: It's a cool, exciting new piece of technology. In return, Canada is going to be able to send astronauts on two Artemis missions, including Artemis 2, which will be the first crude mission, and it will orbit the moon. What's really exciting about this, not just for Canada, but for the world, is that this will be the first time that a non-US astronaut enters deep space. It's a different trajectory than has been done before in the Apollo program, so it's technically taking the astronauts further beyond the lunar far side than ever before.

Kate Howells: A Canadian astronaut will be among the people to go further than anyone's ever gone. That's, of course, very exciting. There's also the possibility that other base agencies will make similar treaties. Maybe we won't be the only international participants. Maybe we'll tie with some European astronaut or something. That's all right with us. It's still exciting.

Mat Kaplan: Rest assured, Kate, we love Canadarm are down here as well. Casey.

Casey Dreier: I just wanted to add, this is one of the reasons why I think Gateway is such an important element of Artemis. This is where you have seen the majority of the international agreements come in on, is not the landing on the moon aspect of Artemis, it's at the Gateway station. Canada's on it. They've had an agreement with Australia. They're about to sign an agreement with Brazil. European space agency has a big commitment to Gateway. They'll be adding a module. Japan will be adding a module, and then they also get their share of astronaut slots going out there as well.

Casey Dreier: This is one of the big advantages. This is really, again, building off of the International Space Station model of international shared and joint exploration, that you can have these immense complicated, but fundamentally peaceful projects of exploration that bring people together for these great endeavors. This is why I think you will see things like the Gateway stand a much more likely chance to continue under a new administration than some people, I think have given it credit for, because of these types of agreements.

Casey Dreier: You don't want to now pull the rug out from under Canada and disappoint everybody by saying, "Sorry, you don't get to have your astronaut go out anymore because we don't have a Gateway station." That's just kind of rude. Not that Americans are ever known for doing that, but we have, I think a commitment from the incoming Biden administration. One of their tenets is to rebuild the international relationships, and so I see this as being a very strong sign that this would continue.

Kate Howells: Also, as a stepping stone, towards sending humans to Mars, I think the process of establishing how to cooperate internationally in deep space is super important. The things that we're going to learn, I mean, like we learned so much about working together in space with the International Space Station, we're going to learn so much through Gateway and then be able to carry those lessons forward to do Mars human space flight to Mars in a sustainable way, because it's always going to have to be international for it to be sustainable. So, this is great practice for that.

Mat Kaplan: Jason, in the meantime, as we prepare for this return of humans to our natural satellite, thanks to China, at least 2020 was a pretty busy place, lunar-wise, and more to come in 2021. What is the status?

Jason Davis: As the year went on, Chang'e-4 is still operating on the far side of the moon. It launched back in 2018. It's easy to forget what a huge milestone that was at the time. No one had ever landed on the far side of the moon like that before. That requires a relay satellite. It was a big accomplishment for them, but the rover, still going. They've also done some interesting science from that mission. It has a ground penetrating radar that has been able to look underneath the surface and discern some of the subsurface layers.

Jason Davis: A similar version of that is actually flying to Mars on the Tianwen-1 spacecrafts rover. In the meantime, they also launched Chang'e-5, which is over already. It was very quick by space mission standards to fly to the moon, land, get samples and return to earth. That was the first sample return since the Soviet Union's Luna 24 mission back in 1976. So, it's hard to believe that it's been that long since we brought anything back from the moon, but China did it.

Jason Davis: That was a hugely ambitious mission. It used Apollo style docking techniques. It had the spacecraft wait in orbit, and then launched back off the surface and rendezvous in Luna orbit. That had never been done before, an automated rendezvous like that. The Apollo missions all had people in orbit helping control it. That was hugely ambitious. That really paves the way for their technologies going forward. To top it up, they got 1.7 kilograms of samples that was slightly less as I understand it than they had hoped to get because their drill encountered some rocks underneath the surface that they couldn't get past, or at least, because it was such a short mission, they did want to risk damaging the drill.

Jason Davis: Wanted to get the samples and get out of there before anything else went wrong. A big success for them, and that was the major activity around the moon, these robotic missions. If you look back to see when China started all of this, I think Chang'e, the first Chang'e mission was like in 2007. It's just been astonishing to see their very step-wise methodical progress. now they have a mission going to Mars right now. It's really exciting in terms of the science return, these international contributions that are coming in.

Casey Dreier: What else goes into space and needs to come back like sample return? People, right?

Jason Davis: Yeah.

Casey Dreier: This is a dry run in a sense, or practicing the same types of techniques and things. This is why sample return tends to be expensive robotically and this is why human spaceflight is expensive because you need to bring your payload back alive and in good shape. To Jason's point about the step-wise approach that China's been taking, this feeds into, I think, a clear, larger goal, but then, at the same time, we just have to acknowledge that this was a spectacular success. I have just been so impressed with the speed at which they've been developing this very advanced capability and just nailing it.

Casey Dreier: We saw the previous year multiple attempts to land on the moon. India and Beresheet from the Israeli private organization, both of those failed landing on the moon is really hard. Here China does that, and then takes off, rendezvous in space, comes back and succeeds in that entire mission. That's not an easy thing to do and this is a real statement of capability by this upcoming space power.

Mat Kaplan: Bruce, China will have company before too long up there, including a spacecraft carrying a project that The Planetary Society had a role in.

Bruce Betts: Yes, PlanetVac, which is one of our great success stories of Planetary Society of Science and Technology enabled by our members and donors, because PlanetVac, Planetary Vacuum, which is a surface sampling technique that basically sucks the material up or blows it into a sample container attached to a lander leg. PlanetVac had funding issues first, in 2013, and then in 2018, where in their development of this Honeybee Robotics, it needed infusion of money at key times, and our members provided that. So, it advanced to the next level. First, with a vacuum chamber test, and then a test on a Masten rocket in the California desert.

Bruce Betts: Now, it's been selected to go to the moon, launching nominally in 2023 as a technology demonstration for NASA. Then also, in 2024, it's going to be flying to Phobos, Mars's moon on the Japanese MMX mission, which is a Phobos sample return. It'll be one of the two methods of collecting samples that will come back to earth, so we're excited.

Mat Kaplan: Very exciting stuff. Yeah. Onward to Mars, which we still believe the moon is a stepping stone too, that's what a lot of people say. Lots to look forward to. Maybe this is the most exciting stuff coming up in 2021, certainly early in the year. Jason, take us through it.

Jason Davis: In pandemic time, everything has been such a blur. I feel like I can hardly remember some of these missions, but at the time, this was huge. We had three big Mars launches all in July, all at once to meet the small window when Mars and earth are optimally aligned to send a spacecraft there. In July, we had the Hope orbiter launch. It's a mission from the United Arab Emirates, and there's also some other international collaboration on that as well.

Jason Davis: That's the Arab world's first Mars mission, and that was successful and it's on its way. Tianwen-1, the orbiter and rover that we already mentioned, that was China's mission. It's their first mission that they've launched to Mars, fully on their own. They did have a ride along spacecraft on the Phobos' grant mission that sadly did not make it all the way to Mars, didn't even make it out of earth orbit, sadly. Perseverance also launched in the same window. That was NASA's big flagship rover. It's basically an advanced upgraded version of the Curiosity rover. All of those are going to arrive in February.

Jason Davis: Just to run through some cool highlights of each Hope, it's going to do the first complete picture of Mars's atmospheric processes from top to bottom. Tianwen-1 is another huge leap for China in terms of a technology demonstration. It's basically like a miniature Viking mission for them. They've got an orbiter, and then they'll drop a lander as well after arrival. I mentioned before that subsurface radar that might be able to detect pockets of water under the surface. Then Perseverance, which also has a radar, ground-penetrating radar instrument on it. perseverance is going to directly search for signs of past life, which is just hugely exciting.

Jason Davis: It's going to land in this River Delta, and we know on earth River Deltas just preserve signs, past life, and they're good places to find indicators of life. It has a couple of instruments to look. There's an instrument called pixel that can look for microscopic fossils. There's these raman spectrometers that use ultraviolet light to find organics. Then, of course, there's the other main function of Perseverance, which is that it's going to collect samples and store those and return those to earth. It won't be returning them to earth, but other future missions will, so big Mars year.

Mat Kaplan: Casey, sample return from Mars, still the holy grail, isn't it?

Casey Dreier: But we're one step closer. We've gotten to the cave that holds it, like in Indiana Jones. There's no need to walk the path and answer all the riddles correctly.

Mat Kaplan: Just watch out for that rabbit.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, and we have to choose wisely how we proceed. Yeah, sample return. 1978 budget request for NASA has a line in it, right after Viking that says, we're looking into pursuing sample return. We were requesting $10 million to study this effort, hopefully for some time in the late 1980s. Did not happen, obviously, right? Did not return samples. Not even try. We didn't have a Mars mission after Viking until Mars observer in the mid to late '80s. Late 1990s, we had this whole new Mars program where we were sending small missions to Mars all the time with this goal, Mars sample return early 2000s. Then of course, you had the failures of Mars Polar Lander and Climate Orbiter. There goes your Mars sample return.

Casey Dreier: Reformulated the entire program. Wanted to do Mars sample return in the 2010s. Budget collapsed again, got pushed back. With Perseverance, taking these samples, dropping them on the surface of Mars, we are taking the first step in this multi-mission effort that has been a goal for almost 50 years now. This is a huge deal, and we're not just leaving them there to rot, right? We actually got, in this latest budget that just passed less than 24 hours ago as we're recording this, $263 million to begin the first phase A, the first formulation, the formal start of the second mission to grab those samples and launch them off the surface.

Casey Dreier: We have signed an agreement with the European Space Agency who has stepped up with billions of euros on their side to create the Mars earth return spacecraft, and to create their fetch rover on the surface. This is a big deal that has been years in the making, and we actually secured the funding in both space agencies and they're starting working on it now. It's a huge win for us and for the Mars community and for planetary exploration in general.

Mat Kaplan: Kate, that ESA role, it is really key to making this happen, to bringing back those bits of Mars.

Kate Howells: Yeah. I'll say this again and again all the time that there's so much more that you can accomplish when you work together. The more nations and space agencies and companies develop their own independent capabilities, the more opportunities we have to work together to accomplish things that would be impossible, or at least very, very difficult as individual nations. Sample returned from Mars is a great example of something that it's so important, but it's so difficult. It's expensive. It requires sustained funding over the course of many administrations. We know in the US that's difficult to assure that you'll have that.

Kate Howells: So, having international agreements really helps, and having just more space agencies pitching in, that really helps a lot. Likewise, when we're seeing like the Hope mission and Tianwen-1, these are really great advances for other countries in their space programs and it's also just bringing them closer to the level where they can collaborate and contribute and just make so much more happen. I'm all for all this collaboration, everybody coming to the table,

Mat Kaplan: You bet. Let's return to perseverance for a moment before we move on. I will remind listeners, most of you probably heard it, our guests, Mike Hecht, just in the last week or two here on Planetary Radio, talking about MOXIE, and this experiment to create oxygen on the surface of Mars, which probably is going to be key to getting humans there, and even more important, back again, but not just that, because Bruce, Perseverance is also the fulfillment of something we at The Society have been pushing for, for years. Can I hear you on this?

Bruce Betts: Yes, you can.

Mat Kaplan: Through a microphone.

Casey Dreier: It sounds like a good idea to me. I know, I've heard some good things.

Bruce Betts: Planetary Society has been pushing for puns for its entire history and for microphones since at least the mid 1990s when Carl Sagan, as one of our founders, wrote a letter to NASA recommending this. The concept being, that in addition to the science you might do, we're actually adding a second sense, but beyond pictures and sight, to actually make this a real world to people, an experiential activity. We flew on Mars Polar Lander, which crashed in 1999. And we were selected for the French NetLander mission, which was canceled.

Bruce Betts: We almost were selected for several additional missions, but now microphones are flying, and there are microphones from NASA for entry, descent, and landing. Hopefully we'll hear the pyro charges going off and the wind rushing by, and then the super cam instrument has got a microphone integrated into it to not only listen, to sounds for recreational purposes and excitement, but also to integrate into their laser zapping instrument that's zaps a rock with a laser, vaporizes it, looks at the spectra from it.

Bruce Betts: Well, they can actually determine some things from the loudness of the crack when it does that vaporizing of rock materials. We're very excited that we're finally going to hear Mars.

Jason Davis: I cannot wait to see the video because I believe we're having, once again, good entry descent and landing video, or it's still images that will be spliced together to look like high definition video. That synchronized with the audio of the charges firing and all of the separation noises. I'm ready to have my mind blown. I can't wait.

Mat Kaplan: Stay tuned to this conversation because we're going to talk about how The Planetary Society is going to make it even easier and more exciting for all of you out there to participate in this arrival at Mars with Perseverance. You might think from this conversation, Jason, that sample returned from Mars and elsewhere, this might actually prove to be a big deal. 2020 gave us lots more evidence of that.

Jason Davis: It was the year of sample collection. No, sorry. It was the year of sample turn. We already did the collections. Well, we did a collection in 2020. Hayabusa2 returned its samples from Ryugu. It had collected them already and finally got them back to earth in December. They've just now, in the past few days, opened the sample container and discovered that they did get a lot of good samples, including there was some fun on Twitter. I don't know if any of you saw that there was a mysterious metal object in one of the containers that, to me, it looked like a gum wrapper almost, but what actually probably happened was it's a piece of aluminum that came off the inside of the collection tube when they fired the little bullet into Ryugu.

Jason Davis: Yeah, we got those samples back. That's really exciting. At the same time, OSIRIS Rex, NASA's mission to Bennu, that collected its samples. It was so successful. It was almost actually too successful when they collected the material. We're getting ready to stow the container. Took some photos of it. They noticed they were leaking pieces of Bennu outside of the container. One of the flaps was jammed open. There was actually a little bit of concern for them that they weren't going to be able to store the samples correctly because they had too much. But they did get it in safely and it will be departing from earth next year. Then we already mentioned Chang'e 5 returning its moon samples. Yeah, big year for sample return.

Mat Kaplan: Especially from asteroids, Bruce, why is this so significant? Remind us.

Bruce Betts: Well, asteroids are like time capsules from the early solar system. They're mostly on altered depending on your astroid, and they preserve the early history of the solar system. So, it's useful in learning about that and what was coming to earth in terms of material early in the process. The other thing to keep in mind is how important sample return is scientifically, wherever you're collecting from, you collect, and you have context of where you've brought it from, and then you bring the samples back to earth. Well, despite all the advances in instrument technology for spacecraft, there's still instruments that we can't fly easily on spacecraft, notably radio isotope dating instruments, and so being able to bring them back and use the full capabilities of earth laboratories and allow multiple scientists to get samples and do the studies to make sure everyone's in agreement or not, as the case may be, is incredibly important.

Mat Kaplan: Let's turn back to advocacy. For that, we'll go to the chief advocate because that is such a big part of what The Planetary Society does, and maybe the biggest event of 2020 in that area. Casey, would you say that about the day of action?

Casey Dreier: It was, but I think by default, because coronavirus hit basically three weeks later after the day of action in 2020, but we did. It was a great day of action. We inadvertently timed it perfectly. Everyone was safe. We had 115 people from 28 different states across the United States all fly themselves right on their own dime to Washington DC, or drive, or take the bus, or however they traveled. We met with 168 offices. We pushed for our top priorities from our sample return for the restoration of funding for the Roman Space Telescope for support for planetary exploration, for planetary defense.

Casey Dreier: They just did a great job. It was so much fun. It was the biggest crowd that we had ever had. It was just a great experience. Again, the timing was couldn't have been better. It was one of the last trips I ended up physically taking last year, and probably also for a lot of people, but again, just if we had put it much later, it would not have happened in the same way. Grateful that it worked out the way it did.

Casey Dreier: We are just seeing the results of their work now, so this is the delayed satisfaction aspect of advocacy, right? We had to go through this whole thing, but what we advocated for, we largely got in the final budget for NASA this year, we got the funding from our sample return. We helped restore funding for the Roman space telescope. We got a commitment to a 2025 launch date for the NEO Surveyor mission. We saw increased funding for planetary science and critically for two operating Mars missions, Odyssey and Curiosity, that were both looking at very significant cuts to their operations, to the point of basically canceling Odyssey, both those missions are restored.

Casey Dreier: Our advocates did that work, and then we followed up on it for the rest of the year and we got the results that we were looking for.

Mat Kaplan: I was just enjoying the latest edition of The Planetary Report, our quarterly magazine, and there was a little piece in there about the success of the day of action. Two significant things, representative Judy Chu commenting because The Planetary Society was commended last year, and she was talking about the importance of hearing from people like the folks who show up for the day of action. But also, the quote from one of the people who had made their way to Washington on their own dime and said, they had always thought, up until now, of Congress and what goes on Inside the Beltway as them, and now she knew it was us, which I found rather touching myself.

Mat Kaplan: Kate, we're The Planetary Society. We're not going to get any minor irritant like a pandemic get in the way of a day of action for 2021, are we?

Kate Howells: Absolutely not. We are not going to let a pandemic stop us from advocating for what we believe in. On March 31st, 2021, we will be doing another day of action, and it will, of course, be virtual this time around, because we can't send people to DC like we used to. But we will be organizing virtual visits for people who sign up to participate. If you go to planetary.org/dayofaction, you can find out all about that and register. I definitely encourage every US citizen listening to do that. Now, if you're not a US citizen, or if you are, but you just don't really have the time to do this full on day of action, there are definitely other ways that you can participate and we outline those at that same website.

Kate Howells: We give you instructions for calling your representative in Congress, writing a letter. If you live outside the United States, we provide talking points on these same priorities that people are going to be advocating for to Congress. You can advocate for them to your representatives in government, to your community, your friends, your family, just spreading the word of what we think is the most important things to be working towards in space science and exploration. The more we can get the word out about those, the more we're able to make them actually happen. There are lots of ways for people to get involved, whether signing up for the official day of action or participating from home.

Mat Kaplan: Let's continue this look ahead at, not just 2021, but maybe beyond that. Jason, beginning with the James Webb Space Telescope, boy, have we been waiting a long time for that.

Jason Davis: Yes, quite a long time and we might finally see it happen next year. Yeah, the December of TPR, actually, we opened with a picture of the James Webb Space Telescope. We were looking for something to put in that little blurb about it. I went back looking for, well, when did it actually start? Conceptually, scientists had been wanting a new telescope, even when Hubble was getting built and launched, but NASA finally announced the name in 2002, and I was able to find a good press release from them. At that time, they said it was going to launch in 2010.

Jason Davis: It's common for these big one of a kind projects to go over budget, fall behind. That happens quite a bit. But it's been particularly rough for James Webb. However, if all goes well, right now, it is on track for launch on October 31st, 2021, Halloween, if you celebrate, or you want to make it particularly scary because I think everybody is going to be terrified when this giant billions of dollars invested in this observatory flies. Once it gets up there, boy, it's just going to be incredible.

Jason Davis: There's so many. We could go on and on about all the astrophysics functions it's going to have in planetary science. One of the things I'm really excited about personally is exoplanets. I know there's already a proposal to use it to image the TRAPPIST-1, which has a bunch of habitable zone planets. Really cool, and we're keeping our fingers crossed that it happens next year.

Mat Kaplan: The Planetary Report, which of course, the digital version of that is available to everybody for free at planetary.org. Members get the beautiful print edition, which I was enjoying. Casey, what are you looking forward to?

Casey Dreier: Well, again, I don't know if you've heard, but we will have a new president coming in, new administration, January 20th. I'm absolutely looking forward to their space policy development that'll be happening, and of course we'll be part of that discussion with them. I'm looking forward to who the new NASA administrator is going to be and where they're going to try to take the agency. We do also have a new Congress coming in. We still don't know exactly which party is going to control the Senate, and we're going to have a much closer, much narrower democratic majority in the house of representatives.

Casey Dreier: So, there's a lot more people to engage, a lot of new people to engage. The Planetary Society is planning an aggressive effort to really push our priorities and your priorities, the planetary defense search for life and planetary exploration. Always with advocacy, there is never an end to it, right? There's always new people to advocate to. There's always change. There's always people you have to introduce to these ideas for the first time. That's why we have to do this on a year round schedule every day, day in, day out. That will be keeping us quite busy as we go forward in the next year.

Mat Kaplan: Bruce, there's a big announcement coming up from your side of The Planetary Society, that innovation side, what? Building on Shoemaker NEO?

Bruce Betts: Building on that and just literally, since the beginning, we have been doing science and technology grant funding, since the beginning of The Planetary Society within a year after its founding. We'll be launching a new grant program, The Step Grant, Science and Technology empowered by the public around the beginning of February. We'll be putting out a request for proposals and calling for anything that fits within our core enterprises, basically within the purview of The Planetary Society. You'll be able to learn more about that in a little over a month.

Mat Kaplan: Kate, much going on around the world for us to look forward to as well. We'll continue to look to you to fill in the international side of this.

Kate Howells: I can't possibly cover all the things that everybody's doing around the world, but I'll pick my favorites. I'm definitely looking forward to James Webb Space Telescope launching. Crossing my fingers that, that happens next year because I too have been watching that launch date just slide and slide and slide, but that is going to be such a spectacular instrument. Even though it's a NASA mission, there's going to be a lot of international participation. Lots of scientists around the world are going to be able to use that instrument to do amazing research and discover incredible things. I just cannot wait to see what we're going to see with that.

Kate Howells: We've got some really cool missions coming from the European Space Agency launching in 2022, so not directly on the horizon, but coming up real soon. Their Rosalind Franklin Mars rover will be launching, and their JUICE Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer spacecraft is going to be launching. I am personally a humongous fan of the cool moons, and I guess also hot moons of Jupiter. I'm really excited to, to study those up close. I know it's going to be several years before it actually arrives, but still looking forward to all that.

Casey Dreier: One thing that we should acknowledge, just looking back to the year, just a big thing, is how successful NASA and other space agencies were in continuing their program despite the pandemic. I think that's worth acknowledging that we saw Mars launch, multiple Mars launches, right? We saw commercial crew happen. We saw a number of missions continue development where there was no guarantee that would happen. If they had missed those lunch windows, we'd be waiting two more years and spending hundreds of millions of dollars.

Casey Dreier: I just want to take this moment, I mean, this was not a guaranteed outcome, but NASA and their partners and aerospace companies and agencies around the world really stepped up and did it as safe as they could and continued this opportunity to explore despite this incredible unpredicted challenge.

Mat Kaplan: Absolutely. Thank you for that. All right, let's call this next round in the few moments we have left, a lightning round, as I'll give each of you a chance to look forward one more time. I'll get us started. We already mentioned the EM1 launch, that first launch of that big rocket, the Space Launch System, hopefully carrying, well, it will be carrying the NEO Scout solar sail, but it's going to be a big year on the commercial side. We have high hopes for Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin's, New Glenn rocket may actually take to the skies in this coming year.

Mat Kaplan: I think they're talking about late in 2021 now. And of course, Starship from SpaceX is all ready. It may not have ended successfully, but it sure was an impressive flight watching that gigantic rocket fly horizontally. I don't know, folks. It reminded me of something out of an old Flash Gordon serial watching that thing.

Jason Davis: It was like the space shuttle only without the big wings and actually a rocket.

Casey Dreier: I'll never grow tired of watching SpaceX blow up their rockets.

Kate Howells: Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: Apparently, Elon doesn't either.

Kate Howells: As much as you wish for success, it is exciting to see a huge explosion.

Casey Dreier: Particularly, again, best timing at the end. Right? They got all the data they needed and then just toss in an explosion. Just a perfect finish.

Jason Davis: Just for fun.

Casey Dreier: Just for fun.

Mat Kaplan: Bruce, you've got anything else so that we should be putting on the calendar.

Bruce Betts: LightSail 2, still going, still flying, still doing good stuff. We also funded part of Debra Fischer at Yale, her 100 Earths program searching for earth-sized planets around other stars. They'll be continuing to search, including using equipment provided by The Planetary Society. We've got another planetary defense conference that The Planetary Society is a primary sponsor for, the one conference that brings together all the experts from all sorts of different areas in planetary defense. We also have a new Shoemaker NEO Grant round call coming in a few months, and farther in the future, I'm excited that Apophis fly by in 2029 and what we can make out of it.

Mat Kaplan: Kate, you'll get the last word. We've hinted at it here in there. We've got big plans to celebrate around Perseverance. Tell us about planet fest.

Kate Howells: Yes, so mark your calendars for February 13th and 14th. It's a weekend. You might have to sacrifice some of your Valentine's day plans, but it'll be worth it because we are doing a planet Fest throughout The Planetary Society's history. We've tended to mark major mission milestones like landings on Mars with planet fest, so it's always a huge celebration. Normally, we do this in-person in Pasadena where we're headquartered. Because of the pandemic, obviously we're not doing that, which is actually, in my opinion, as someone who doesn't live in Pasadena, this is fantastic, because then people from around the world can participate.

Kate Howells: It's going to be a virtual event, two days of excellent panels, fascinating topics being discussed by world-class experts, workshops where you can learn things yourself that will be useful to you as a space lover, a space advocate, and culminating with a watch party of the landing itself, which we are going to see and hear. For the first time, it's going to be absolutely phenomenal, so mark your calendars. We're going to be talking about it lots more in the coming weeks. I'm sure Mat will talk about it on Planetary Radio. Make sure you sign up for our email newsletter at planetary.org/connect. It's going to be a heck of a party.

Mat Kaplan: And how? I happen to know, I don't think we're prepared to reveal the names just yet, but we have some terrific people lined up to participate in that two day virtual celebration planet fest followed on February 18th by our ... We'll be complimenting NASA own coverage of seven more minutes of terror as Perseverance descends to the Martian surface. The rumor is that we might actually be joined by Bill Nye, the science guy. Can you confirm that, Kate?

Kate Howells: I mean, he's got a busy schedule, but I think he'll make the time for us.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, folks. Thank you, colleagues. It has been a wonderful year serving with all of you and all the rest of our colleagues. I sure am looking to 2021, which is going to kick off with a bang with all that activity out at the red planet. Jason, Kate, Casey, Bruce, look forward to working with you.

Kate Howells: Thank you.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, cheers to fewer plagues next year.

Kate Howells: [crosstalk 00:59:32] first.

Bruce Betts: Cheers to it. Thank you.

Jason Davis: What if we see each other in person? What will we ... Ah, let's not get crazy. Really. Really.

Kate Howells: That's the dream.

Casey Dreier: I'm used to everyone being posted sized heads in boxes. I can't deal with the stimulus.

Kate Howells: I can't see you in three dimensions. That's too much.

Casey Dreier: Yeah.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah. Get yourself a VR headset. Bruce Betts is The Planetary Society's chief scientist. Jason Davis is our editorial director. Casey Dreier is chief advocate and senior space policy advisor, and Kate Howells is our communication strategy and Canadian Space Policy Advisor. Bruce and I will right back with What's Up and that very cool contest prize.

Jennifer Vaughn: Hi, this is Jennifer Vaughn, The Planetary society's chief operating officer. 2020 has been a year like no other. It challenged us, changed us, and helped us grow. Now we look forward to a 2021 with many reasons for help. Help us create a great start for this promising new year at planetary.org/planetary fund. When you invest in the Planetary Fund, your year end gift will be matched up to $100,000, thanks to a generous member. Your support will enable us to explore worlds, defend earth, and find life elsewhere across the cosmos. Please learn more and then donate today at planetary.org/planetaryfund. Thank you.

Mat Kaplan: Bruce is back. Of course, he stuck around for this week's What's Up, the last one of the year that we will not fondly remember as 2020. Welcome back.

Bruce Betts: Thank you. I'm back and better than ever.

Mat Kaplan: Well, you may be, but I'm looking forward to the next year and doing another whole bunch of these with you. I guess we'll do 52 or so in 2021, at least that's the plan.

Bruce Betts: Wait, is there a leap week in ... No, I guess not.

Mat Kaplan: I got a message to read from Emily [Sanzon 01:01:33] in Colorado. She said, if you read this, can you shout out to my engineering teacher, Ms. King? I'm a high school student and she got me a membership to The Planetary Society as an award. We both love space, and I just want her to know how much I appreciate her. Well, Emily, we did it. You know why? Normally, because we don't want to be inundated with these requests for shout outs and testimonials, but Ms. King did the right thing. She made you a member. So, welcome.

Bruce Betts: Yay.

Mat Kaplan: That's it. What's up.

Bruce Betts: We got Jupiter and Saturn are getting lower and lower, disappearing over the next very short time that's still relatively close together, lower in the West soon after sunset, Jupiter being the much brighter of the two. You'll miss them, but they'll reappear in the predawn east by around March. Meanwhile, check on Mars, really easy to see, that reddish bright thing that looks like a star high above in the South in the early evening, and check out to over to its left towards the East in the early evening.

Bruce Betts: Now you can tell it's Northern hemisphere winter or Southern hemisphere summer, because Orion making its appearance looking, like Morion with a bunch of bright stars. Check that out over in the evening East. Then in the pre-dawn we've got Venus, still in the pre-diabetes through most of January, but also it's starting to disappear. Don't worry. It'll be back. I get to try to pronounce it again. The Quadrantids meteor shower, hardest to pronounce of the year for Bruce, peaking on the night of January 2nd and 3rd has a pretty sharp peak. Most of the meteors within a few hours of January 3rd at 1430 UTC.

Bruce Betts: That means Western North America, that's you, Mat, has a good shot at viewing the shower at its best during the predawn hours, probably counts me out, January 3rd.

Mat Kaplan: I love Orion. I love having it come back every winter, and I don't like saying goodbye to it in the spring.

Bruce Betts: Aw. It always comes back for you, Mat. Onto this week in space history, it was 15 years ago, Mat, that we were celebrating wild about Mars over a two to three day period. Stardust flew through the coma of comet Wild 2, and the Spirit rover landed on Mars.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, that was a great party.

Bruce Betts: Onto [inaudible 01:04:07] space fact. The difference between Mars is highest and lowest points is nearly 30 kilometers. That's from the top of Olympus Mons to vertically to the bottom of what we'll talk about in the trivia question in just a moment. In comparison, earth is only a little less than 20 kilometers of a difference between Mount Everest and the bottom of the Mariana trench. Mars, it's kind of rougher. Rough, rougher.

Mat Kaplan: High relief, as Norman [Cassoon 01:04:43] said in response to your trivia question, but go ahead, what was that question?

Bruce Betts: In what feature is the lowest point on Mars? I assume we did well, is that correct?

Mat Kaplan: We did very well. Yeah, not quite as big a response as last week, which was off the charts, but I already mentioned Norman Cassoon and he had discovered this term that replaces sea level on Mars and was also noted by Laura Dodd, Hudson Ansley and others. Do you know the word I'm talking about?

Bruce Betts: The reference datum?

Mat Kaplan: Well that, but areoid, or I guess it's areoid.

Bruce Betts: Oh yeah. It's like the GOA for earth, but using Aries as the adjectival version of Mars derived from the Greek Aries.

Mat Kaplan: Here's a poetic answer from Jean [Lewin 01:05:30] in Washington, from the lofty Heights of Olympus Mons to the depths of Hellas crater, one, a sloping volcano, the other, a planitia. Determined, not by C-level. C is gone since its formation. It's measured through the Mars areoid, a reference, elevation. First of all, is he right about that with Hellas, and is it okay to call it a crater?

Bruce Betts: Yeah. Usually, it'd be referred to as an impact basin because it's so dang huge, but it is indeed an impact crater. It's one of the largest in the solar system. Over time, it's been filled in forming a relatively flat floor that's deep down about 2300 kilometers wide. It's big.

Mat Kaplan: Very big. [Ola Franzen 01:06:15], long time listener, first time winner. He's in Sweden. Ola said, yeah, Hellas planitia. For that Ola, you have won yourself a brand new design, Planetary Society baseball cap, the one you can get from the chop shop, Planetary Society store at a planetary.org/store, so congratulations. A few people pointed this out, that even within Hellas, there's something lower, apparently Badwater crater inside the Hellas plain, the hell plain. He says he found this in a book about Mars typology that his partner got him for his birthday this year.

Mat Kaplan: Fun to look at, but also good for prizes maybe. Well, not this time, Sam. Keep trying. But had you heard of that one? It's basically, I guess a crater inside a giant crater.

Bruce Betts: There are lots of craters inside a giant crater, especially since we tend to get more small impacts later in the solar system history. I had not heard of that, but Badwater is the lowest point in the U S and Death Valley.

Mat Kaplan: I love this one from Darren Richie, also in Washington, the 0.0124 bar of predicted atmospheric pressure at Hellas, wait for it, it's worth it, is 90,870 times less than the 1126.79 bar measured in 2019 at Earth's lowest point, the Challenger Deep in the Marianas Trench, which Bruce already mentioned. Here's the kicker, Venus and the Gas Giants find this fact cute.

Bruce Betts: I love the music by that band, Venus and the Gas Giants.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, and Venus, man, I wish her solo career had gone better. We'll close with this poem from Dave Fairchild in Kansas. Hellas Planitia, the Martian and Death Valley was carved by an asteroid back in the day making the basin. It sinks six kilometers down from the surface. Oh, that's what they say. Just for the record, the sea level now, Bruce, is 6.1 millibars pressure. It's true. Since there's no ocean of water, we substitute measuring pressure of Mars' CO2.

Bruce Betts: Nice.

Mat Kaplan: Well done. Well done. We're ready for another one of these

Bruce Betts: Looking back on 2020, here's your question, how many crewed launches to space were there in 2020? How many launches launched people to space in 2020? Go to planetary.org/radiocontest.

Mat Kaplan: That's fascinating. I started working it and out of my head, but I will wait for one of you to answer this by Wednesday, January 6, 2021 at 8:00 AM, Pacific Time, and appropriately for the start of a new year, a really special prize that's all about things started, it's a device called Time Since Launch. It's from this cool little company, CW&T, that are just a bunch of design, interesting people. I won't say geeks. They make all this really amazing stuff. They're at a CWANDT, or cwandt.com. One of their devices is this thing called Time Since Launch. It is a burrow silicon glass tube with well sealed aluminum ends, and a pin. There's a counter inside. When you pull the pin out, it immediately starts counting. And it will count, are you ready, Bruce?

Bruce Betts: How long?

Mat Kaplan: Glad you asked, 2,738 years.

Bruce Betts: Wow.

Mat Kaplan: It's like to mark an event. They apparently thought of this because they were looking at the time since launch for Apollo 11 and every other space mission. They thought, oh, we could do that in a tube and people could buy it. Can't stop it. Once you pull the pin out, it's going, they did make it easier to replace the batteries, although you don't have to do that very often, but there it is, a Time Since Launch device will go to the winner, the one who correctly answers this week's question and is chosen by random.org. Well, Time Since Launch of this What's Up, I think is complete.

Bruce Betts: We've got a Time Since Launch for LightSail 2 on our website.

Mat Kaplan: That is where again?

Bruce Betts: Sail.planetary.org.

Mat Kaplan: I'm nothing, if not a shill for my organization.

Bruce Betts: Thank you.

Mat Kaplan: We're done.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody. Go out there, look up the night sky, and think about the top three and a half fun things you look forward to doing in 2021. Thank you, and goodnight.

Mat Kaplan: I'm going to get a fast food hamburger. I won't mention the company I want to get one from.

Bruce Betts: Beef.

Mat Kaplan: Not beef. No. He's Bruce Betts. He's the chief scientist of The Planetary Society who joins us every weekend for What's Up. Happy New Year, Bruce.

Bruce Betts: Happy New Year, Mat, and everybody out there listening.

Mat Kaplan: Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by its members who join me in wishing you the best of New Years. Mark Hilverda is our associate producer, Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Peter Schlosser. Ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth