Planetary Radio • Oct 31, 2018

Celebrating Kepler

On This Episode

William Borucki

retired Kepler principal investigator

Padi Boyd

Project Scientist for NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite for NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

Jessie Dotson

Kepler Project Scientist for NASA’s Ames Research Center

Paul Hertz

Astrophysics Division Director for NASA

Charlie Sobeck

Kepler project system engineer for NASA's Ames Research Center

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

The Kepler mission has ended. Listen to highlights of the October 30th media briefing that included the father of the fantastically successful planet finder, William Borucki. Then catch the thoughts of Planetary Society editors and commentators Jason Davis and Emily Lakdawalla. Director of Space Policy Casey Dreier explores what’s at stake in the US November 6th midterm election. And we’ll give away another copy of Bruce Betts’ Astronomy for Kids in a spooky edition of What’s Up.

- Kepler and K2 Missions

- NASA Retires Kepler Space Telescope, Passes Planet-Hunting Torch

- Farewell, Kepler

- TESS: Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite

- A Joyless First Man

- Planetary Radio theme song

This Week’s Prizes:

A trendy Planetary Radio t-shirt from the Planetary Society Chop Shop store, a 200-point iTelescope.net astronomy account, and a signed copy of Bruce Betts’ new book, Astronomy for Kids.

This week's question:

Before the Parker Solar Probe broke the records for closest spacecraft to approach the sun and fastest spacecraft relative to the sun, what spacecraft held both of those records?

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at http://planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, November 7th at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

In an unrelated coincidence, what sequence of events that will occur for the BepiColombo mission can be characterized by the first three primorials, 1, 2 and 6?

Answer:

The answer will be revealed next week.

Question from the October 17 space trivia contest question:

On a typical pair of binoculars, what do the two numbers mean?

Answer:

The first number provided on binoculars is the magnification factor, while the second is the diameter of the objective (larger) lenses in millimeters. So, 7x35 binocs are 7x power with 35 millimeter objectives.

Transcript

[00:00:00]

[Mat Kaplan]: Long Live Kepler, this week on Planetary Radio. In the words of Paul Hertz, NASA Astrophysics Division Director, the Kepler exoplanet hunter has...

[Paul Hertz]: Run out of fuel. This is not unexpected and this marks the end of spacecraft operations for Kepler and the end of the collection of science data.

[Mat Kaplan]: Welcome, I'm Mat Kaplan of the Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our Solar System and beyond. The announcement was made in a media briefing on the morning of Tuesday, October 30th. Stay with us for highlights of that emotional and triumphant briefing along with thoughts about Kepler and more from our own Emily Lakdawalla and Jason Davis. Someone is going to win Bruce Betts' new book today and we'll offer you another chance to pick up a free copy when we get to the What's Up? space trivia contest. We open with the [00:01:00] Planetary Society's Director Of Space Policy, Casey Dreier. Casey, welcome back to the weekly version of the show. A very important announcement that we need to make this time is that we are delaying, from its usual first Friday of the month, November's Space Policy Edition because we want to get past a certain fairly significant event so that we can talk about it.

[Casey Dreier]: Yeah, Mat, have you heard that there's midterm elections happening in the United States on November 6th? Is that something that's come up?

[Mat Kaplan]: (laughing) Oh, you must be kidding. No, of course, and I'm ready. I'm ready with my sample ballot.

[Casey Dreier]: Because a significant amount could change in politics and space politics and space policy, we're going to delay our usual Space Policy Edition until well after the elections have happened so we can bring you post-election analysis looking at any implications (if any) from the elections about what could be happening with space and NASA going forward and so it's going to be [00:02:00] a really interesting discussion. We're going to have some good external guests to bring their perspective as well. And we just figured it would be more interesting than just sitting and speculating about what might happen. It's always nicer to talk about what did happen and then maybe talking about what might happen because of that.

[Mat Kaplan]: And so now we're looking at Friday, November 16, so halfway into the month. As we look forward and as we speak, Casey, it is exactly one week. We speak on the day before Halloween, maybe appropriately. What's at stake here? And what are some of the more interesting races from space advocate's point of view?

[Casey Dreier]: Well, probably the most relevant single race is going to be in Texas's 7th District. That's John Culberson, who is a big supporter of Europa and NASA and Johnson Space Center. He is in a very tight reelection, about a 50-50 toss-up right now with the Democrat running there. There's also the potential of the Democratic party picking up control of the House of Representatives and if that happens it's not just the [00:03:00] new Democratic members of Congress that will be coming in, the entire leadership structure will switch over to the Democratic party. So you'll have new heads of the committees that run NASA's oversight, scientific investigations. You'll have new heads of the committees that fund NASA, and they'll bring with them their own sets of priorities and focuses and efforts there. And all it takes is one extra Democrat than a Republican in the House of Representatives, every single committee chair flips to Democratic control. So we can have big changes even if you retain a lot of the Republicans and Democrats who are already in Congress, even if you have a different majority, so that could be big implications for the future of NASA.

[Mat Kaplan]: What is the good news regardless of of this outcome? I'm going to bet it's that we have discovered that there's so many members of Congress who love space exploration. Casey Dreier That's true, yeah. I'm not particularly afraid of any particular outcome. It's just that the fundamental political balance is going to shift, or could shift. Everyone likes NASA, but unfortunately NASA doesn't drive [00:04:00] politics; NASA tends to get caught up in politics, and that's what we can examine going forward based on what happens on 6th.

[Mat Kaplan]: All right, Casey, Friday, November 16 for the next Space Policy Edition of Planetary Radio. Hope you will join us then, but before I let you go I'm going to look back to October 15 when you posted to the blog at planetary.org really what amounts to a movie review. It made me a lot less enthusiastic about seeing First Man. You called it a "joyless" First Man. Gee, did you have some fun?

[Casey Dreier]: Yeah, I mean, they're part of the movie that are certainly really visceral and exciting. I thought some of the ways that it depicted rocket launches, particularly, the Gemini launch was really spectacular. And normally I really like the director of that movie and the actors in it. I just felt that the overall emotional tone was pretty one note, you know, it was a pretty mopey movie, kind of a downer of a movie about a person [00:05:00] who, like any other human being, has a wealth of emotional experiences. And I'm pretty sure enjoyed walking on the Moon, wasn't all upset about it when he did that. And I just would have liked to have seen a slightly more nuanced, or at least just show some joy of the first man on the Moon. And you know, he was at least happy once on the Moon—we have a picture of you can prove it with—it's just sad that the movie didn't express that side of things.

[Mat Kaplan]: I'm so glad you mentioned that image. I'm looking at it right now, and here is Neil Armstrong back in the Lunar Module after that first walk on the Moon. He is probably exhausted, and yet he has one of the most satisfied smiles probably on the face of, well, I guess on the face of the Moon in this case.

[Casey Dreier]: Small sample size but probably also on the Earth at the time, too. But that's the point, right? Like you can ... Bill always talks about the joy of discovery, right?There's joy in this too and it's important to express that. Not everything [00:06:00] has to be very serious.

[Mat Kaplan]: You bet. Hopefully we will get another telling of this story on the big screen someday that expresses some of that Passion, Beauty, and joy, the PB&J that our boss likes to talk about. In the meantime Casey, I will wish you well and look forward to talking on November 16th.

[Casey Dreier]: Absolutely, and if I can put in one plug: if you live in the United States, please vote on November 6th. It's a great thing to do as a citizen, it's a, you know, minimal responsibility that your democracy asks of you. And no matter which way your politics persuades you if you don't vote no one's going to listen to you. So voting is kind of the minimum activity of democracy, and I encourage you to do it.

[Mat Kaplan]: I'm going to go even further than that. If you are eligible to vote in this country and you are a listener to this program and you don't vote then you are suspended from listening to Planetary Radio for a month. How's that for incentive?

[Casey Dreier]: I all right Mat. I voted already so I can keep listening.

[Mat Kaplan]: Good [00:07:00] for you. Thank you Casey, and thanks for all the other good work you do.

[Casey Dreier]: Always happy to be here Mat.

[Mat Kaplan]: That's Casey Dreier, the Director Of Space Policy for the Planetary Society. We're going to talk now about the end of one of the most successful missions of exploration of all time: the Kepler exoplanet mission.

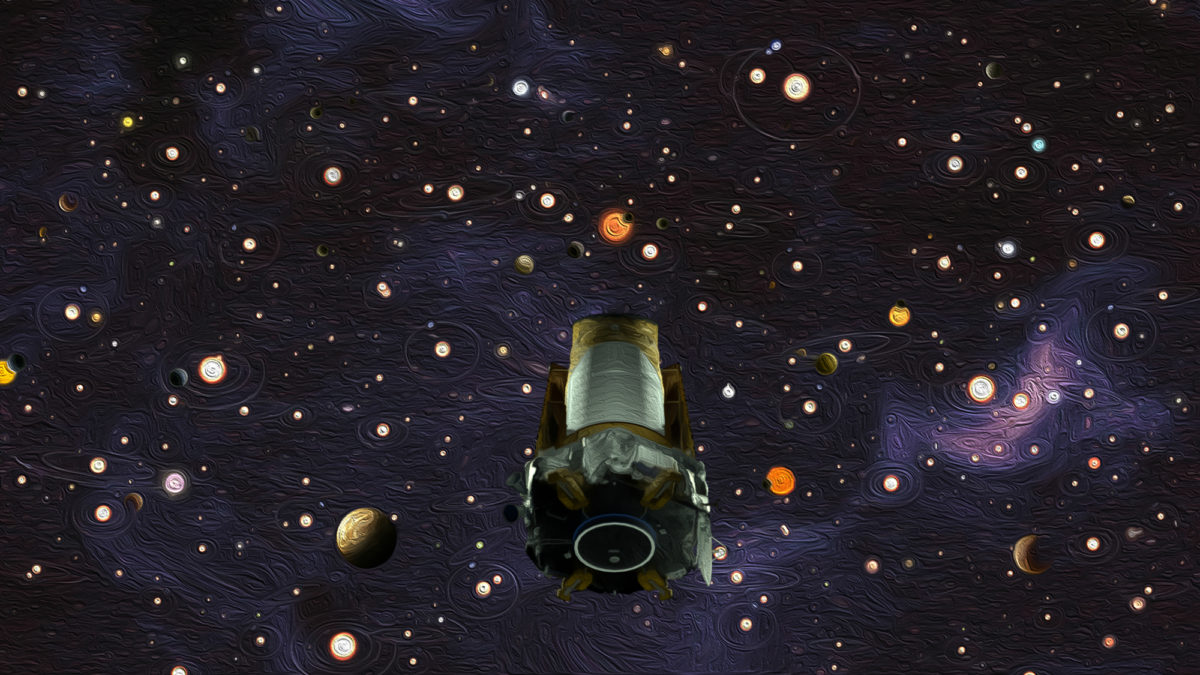

[Padi Boyd]: The launch of the Kepler space telescope in 2009 was a great night for astronomy and for exoplanets. It was an unforgettable, beautiful night launch and I was honored to attend that event with both Bill Borucki and Jessie Dotson, and I'm delighted to join them again here today, when we're discussing the end of a stunningly successful space telescope operation. Bill's intense focus and dedication was an amazing example for all of us. He envisioned and made real a mission to answer a [00:08:00] fundamental question that we've been asking for generations about our place in the universe: how common are small planets like Earth? Are they common or are they rare? And the answer that Kepler gave us is that planets are incredibly common and now because of that we're poised to take the next steps to bring Kepler's exoplanet discoveries closer to home.

[Mat Kaplan]: That was Padi Boyd, honoring the Kepler Mission and its creator on the morning we learned that the spacecraft had run out of fuel. Padi is Chief of the Exoplanets and Stellar Astrophysics Laboratory in NASA's Astrophysics Science Division. She's also a project scientist for the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS, an even more powerful follow-up to Kepler that has now picked up the hunt for worlds circling other stars. Padi participated in a media briefing that celebrated Kepler's enormous success: about 2700 [00:09:00] confirmed planets discovered by Kepler and the follow-on K2 Mission with an almost equal number yet to be confirmed. Of those confirmed worlds, hundreds are Earth-sized, or nearly so. Tens of these are in their star's habitable or Goldilocks zone. Extrapolate that number and you learn that there may be as many as 40 billion such planets in the Milky Way Galaxy. Charlie Sobeck is the Kepler project system engineer at NASA's Ames Research Center in California.

[Charlie Sobeck]: We knew when we launched that the spacecraft would ultimately be limited by its fuel load. That fuel is used to offset the pressure of sunlight that affects the telescope's precision pointing. We began seeing clear indications of fuel exhaustion in late June and took steps to ensure that the science data we had collected onboard was safely returned to the ground. And then whatever fuel was left over would be used to collect some last data and return to Earth as well. [00:10:00] The final end to the spacecraft fuel was seen just two weeks ago when the fuel pressure drop by 75% in a matter of a few hours, indicating that its ability to continue collecting science data had come to an end. Ultimately the team managed to end-of-fuel with precision. They were perfect the way they did that. We collected every bit of possible science data and returned it all to the ground safely. In the end, we didn't have a drop of fuel left over for anything else. Kepler's currently trailing the Earth by about 94 million miles and will remain a safe distance from the Earth for the foreseeable future. As our final spacecraft activity, we will disable the onboard fault protection and turn off the radio transmitters. The spacecraft will then be left on its own to drift away in a safe and stable orbit about the Sun.

[Mat Kaplan]: Bill Borucki earned the kudos he got at the briefing. The retired Kepler principal investigator fought long and hard for a space telescope that could scan a section of the sky for evidence of exoplanets. I've been honored to [00:11:00] have Bill as my guest on four previous episodes of Planetary Radio. Here are his opening remarks at the October 30 briefing.

[William Borucki]: I've always been interested in astronomy. At Ames I've had the opportunity to contribute to a NASA strategic objective to determine the extent of life in our galaxy. Clearly the first step must be to determine if planets are common or rare. In 1983, when I started my search for methods to detect planets orbiting other stars, the only planets that were known were those in our solar system. After several years of investigation, I decided the best approach to find small planets, like the Earth, would be to build an instrument to detect the slight dimming in the brightness of a star that occurs when a planet passes in front. These dimmings are called transits. This dimming is only about one part in 10,000 in star brightness, so I would have to build an instrument that was a thousand times better than anything previously built. [00:12:00] It would also need to be very sensitive and precise to detect those small changes in dim stars. It was like trying to detect the flea crawling across the car headlight when the car was a hundred miles away, and the instrument must do it for a hundred and fifty thousand stars simultaneously. Before I could convince NASA to fund the mission, I had to prove this approach would work. I assembled a team of scientists and engineers and we proved that CCD detectors had the necessary sensitivity and precision. Then we built an observatory that demonstrated that we could monitor thousands of individual stars simultaneously. Next we built a prototype instrument that demonstrated we could meet all the requirements and could do so aboard a spacecraft, and that our team could analyze all the data from all the stars and detect these very small signals. In 2001, we submitted our fifth proposal to NASA. [00:13:00] This time NASA was satisfied that the mission would be successful and gave us the go-ahead to develop the Kepler spacecraft. In 2009, the Kepler Mission launched and immediately our team began detecting a wide variety of planets. In its nine and a half years of operation, the Kepler Mission has been an enormous success. We've shown that there are more planets than stars in our galaxy, that many of these planets are roughly the size of the Earth, and some—like the Earth—are at the right distance from their star so there could be liquid water on their surface, a situation conducive to the existence of life. Kepler's also provide the statistics that are needed to build future, much more capable missions that will determine whether such planets have atmospheres, water, and a possibility of life. Kepler has truly opened a new vista in astronomy.

[Mat Kaplan]: The mission might have ended very differently, and much earlier. In May of [00:14:00] 2013, the spacecraft had the second of four spinning reaction wheels fail. During the briefing, Kepler project scientist Jessie Dotson explained that this meant the spacecraft had lost the critical ability to precisely focus on a patch of sky for the long periods required. It looked like the end of Kepler's planet-hunting.

[Jessie Dotson]: However, our team figured out an extremely clever way to keep operating the spacecraft and taking data. The amazing spacecraft engineers we have the privilege to work with on our team at Ball Aerospace figured out that we could use the solar pressure to provide pointing stability. In addition, to make the most out of our new operating mode, we decided to transition to a fully-open mission where everyone around the world was given immediate access to the latest data. This modern approach lowered the barrier for researchers, particularly early career researchers and even citizen scientists, to enter the growing and exciting field of exoplanet science. Over the [00:15:00] past four years, the number of researchers using data from the Kepler spacecraft has doubled. In our extended mission, Kepler expanded and diversified its data set by observing another 20 patches of sky, increasing the number of stars observed with the Kepler spacecraft to well over half a million. While the science results are still emerging from this expanded data set, it enabled new investigations by observing celestial objects which were not the focus of the original mission. For example, the extended mission studied a large number of bright and nearby stars. Bright stars are scientifically valuable since they are much easier to observe using other telescopes. We found many small, potentially-rocky planets around some of these bright stars. And those are now Prime targets of current and future telescopes so we can move on to characterize what these planets are made of, how are they formed, and what their atmospheres might be like. In addition, we have found exoplanets around [00:16:00] both young stars and old stars allowing us to begin understanding how planetary systems evolve. Scientists are using the results from these 20 fields to probe the history of stars in our galaxy, and are even studying the early evolution of supernova in other galaxies. While we have ceased spacecraft operations, the science results from the Kepler data will continue for years to come. These ongoing discoveries will be enabled by the powerful combination of new software tools, new data analysis methods such as machine learning, and new data both from missions like TESS and upcoming missions like the James Webb Space Telescope.

[Mat Kaplan]: Padi Boyd return to talk about how TESS, which started its hunt last April, is building on Kepler's achievements.

[Padi Boyd]: TESS is designed to look for planets that are orbiting around bright nearby stars, typically ten times closer than the stars that Kepler found planets around. And TESS will observe nearly all of the sky. We're hoping to find our near-neighbor [00:17:00] planetary systems. Now, already, the team is beginning to analyze the first data that's coming down to the ground and we're finding exciting planet candidates and teams are following those up with telescopes on the ground. And we're confident the TESS is going to find thousands more plants just like Kepler did.

[Mat Kaplan]: I was among the many reporters waiting to question the media briefing participants. Bill Borucki was asked if he had favorites among Kepler's many discoveries.

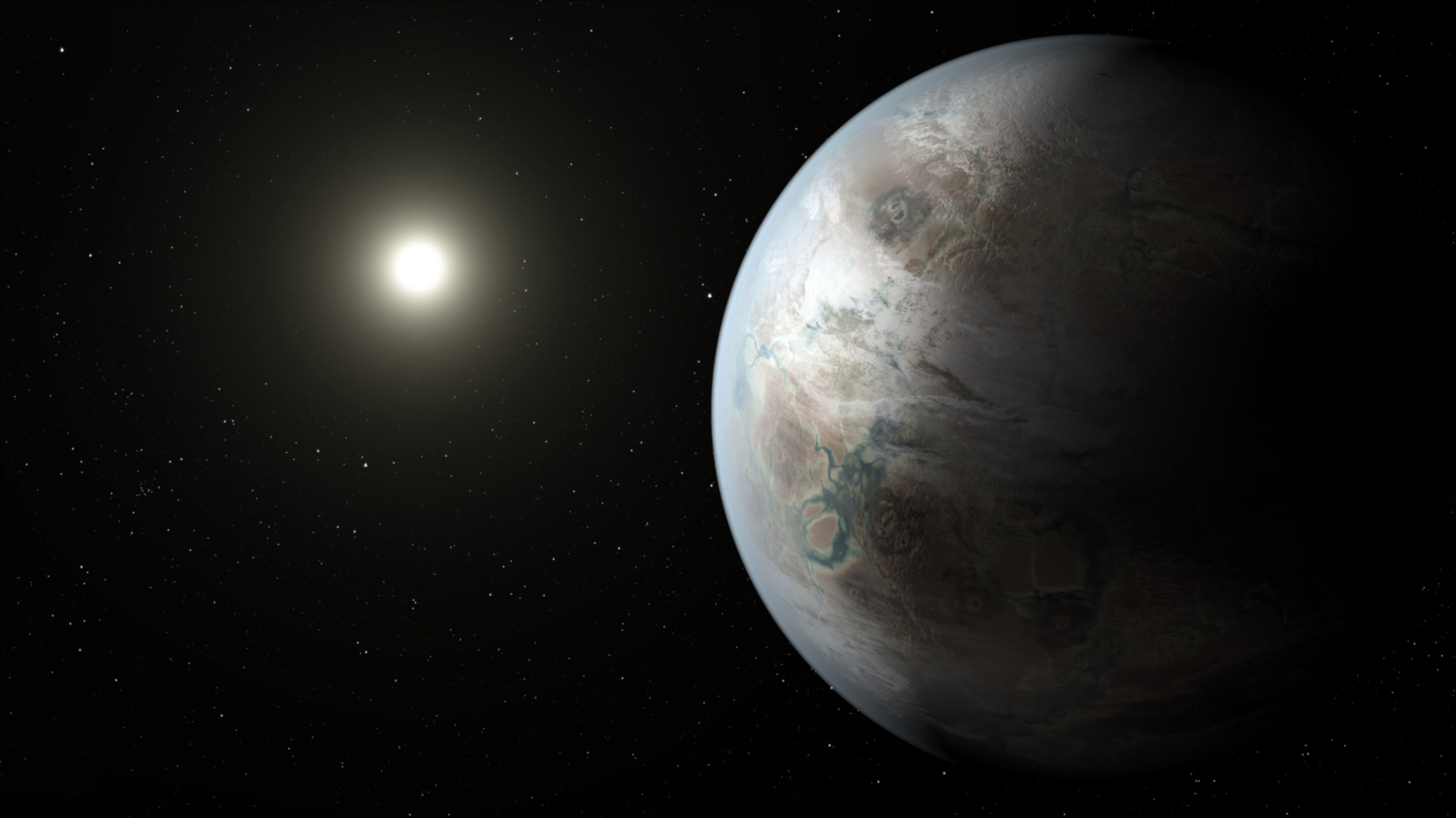

[William Borucki]: Certainly one of the most interesting plants we found is Kepler-22b. It's a planet in between the size of the Earth and Neptune, unlike any planet in our Solar System. It's a planet that may very well be a water world, a world cover with an ocean, and its the habitable zone which implies of course that it's got an ocean and liquid water, it's going to evaporate, it's going to have a water atmosphere, water vapor atmosphere. There's lots of nitrogen, CO2. And in our Solar System you might very well have an atmosphere on water [00:18:00] planet that could lead to life. So it's an extremely interesting planet, it's one of my favorites. But another one is the Kepler 444 system of planets. These are small rocky planets and they were formed around a star that's some six and a half billion years older than our own star, than our own planetary system. If life has been developing over the six and a half billion years before Earth was formed, there may be some very interesting life forms for us to find as we search these early planets.

[Mat Kaplan]: Hello, everyone. Congratulations to you and your teams. A question, probably mostly for Bill, Jesse, and/or Padi: if you could say something about the importance of your partnerships with the ground-based astronomers who have taken from the data from Kepler and I assume now from TESS and are making these confirmations of of all these worlds around our portion of the galaxy.

[William Borucki]: I'd like to answer that one, this is Bill Borucki. They've been absolutely [00:19:00] essential to our discoveries. Kepler finds the signs of these planets, but we really want to know are they rocky planets, gas plants, or something else? So the ground-based people with their telescopes, with the use of the Keck telescope and several other telescopes, give us some mass and that had been tremendously helpful. And what that means of course is they have to get time on these big telescopes. They have to make the measurements and that's difficult. It's difficult to get that time. It's difficult to have the state-of-the-art systems they use and reduce the data and say, "yes, indeed, that particular signal—although it's tiny—is of a planet, you do have a mass now." So the ground-based people who've done radial velocity, the ground-based people who do adaptive optics, and so on, are a huge help in terms of understanding the data that Kepler has brought down.

[Jessie Dotson]: I think Bill absolutely nailed that perfectly. Without the complementary data [00:20:00] from the ground telescopes, there are a lot of questions about what we find. But with that ground data, we can know that we see planets and we can measure the masses.

[Unknown]: Maybe Padi could talk about the follow-up programs for TESS.

[Padi Boyd]: Sure, I'd love to. This is Padi. It's a very smooth continuum between what we're discovering with the space telescopes, such as TESS, and then a large community of ground-based follow up that is going to help us turn those discoveries into something that is a confirmed planet. We fund this activity from NASA. It's very well coordinated and that's very important too because you know, ground-based telescope time is a is a very precious asset. So the team's work together to make sure that the best planet candidates are being sent to the right types of telescopes. There's new instrumentation that's being developed with an eye towards even, you know, improving our ability to make these confirmation measurements from the ground. And I think it's just essential for us all to remember that we make exciting [00:21:00] discoveries with these NASA space telescopes but it's so important for us to also have a very engaged, active, ground-based community so they can really confirm those results and get the most science out of these NASA missions.

[William Borucki]: I'd like to add a little bit more to that, this is Bill Borucki again. One of the things that we talked about is the size of the planet. What Kepler gives us is a ratio of the size of the star to the size of the planet. It's absolutely essential for the theoreticians and the people who work with radial velocity and spectra to tell us what truly is the size that star. We have a group, a very large group of people who do asteroseismology in Europe, and they used the pulsations of these stars to actually tell us the diameter of the star within a couple of percent, far far better than any other method that we have. And now we have our European colleagues who have the Gaia Mission and they can for the first time determine accurately how far away the stars are. Again, that gives us more [00:22:00] information about how big our planets are and whether they're in a habitable zone or not. So it's really a big international team that provides the data that we give to the public.

[Mat Kaplan]: We'll close our coverage of the Kepler end-of-mission briefing as we began, with Padi Boyd.

[Padi Boyd]: The Kepler results are also informing our future mission designs so that we can take the step even beyond that with much larger glass. So I believe the world will remember the Kepler telescope for generations to come, because Kepler gave us the very best answer to that question that we could have hoped for: we live in a galaxy that's teeming with planets and we are ready to take the next step to explore those planets.

[Mat Kaplan]: Highlights of the October 30th media briefing that marked the end of the nine and a half year Kepler mission. Within hours of the briefing, I was joined by Planetary Society Senior Editor Emily Lakdawalla and Digital Editor Jason Davis. It's an honor to have the two, count 'em two editors from the Planetary Society to [00:23:00] talk about this this milestone that we reach today with the end of this amazingly successful mission. Emily, it has taken us, not quite single-handed because of course there was good work being done down here on the surface before Kepler, it has taken us from a day decades ago when we wondered if there were planets around other stars. And now now we kind of have answered that haven't we?

[Emily Lakdawalla]: We really have and you know, it's such a striking contrast to think that when I was a kid, we didn't know if we were the only solar system out there in the universe. And now I love telling, in my public talks I love telling people to look up at the sky. Look at every star you can see and imagine the fact that we now know that there are roughly as many planets as there are stars. Now, not every star has a planet but many planets—I'm sorry many stars have multiple planets. And so there is really a kind of an equivalence in number and if you just think [00:24:00] then of all the varieties of different kinds of planets there have to be out there all the varieties of different systems, you know that there are other Earth-like worlds out there and it just seems so much more possible that there could be life elsewhere in the universe after a mission like Kepler. We still don't know if that's true yet, of course, but we're looking.

[Mat Kaplan]: We're working on it. Jason, you just this morning as we speak on October 30th published this this great farewell Kepler blog post at planetary.org, which I definitely recommend to anyone out there. You even updated it since the announcement was made during this media briefing that we just heard excerpts from. What really stands out to you about this mission?

[Jason Davis]: Like Emily said, the big discovery and the big result that there are as many planets out there as stars in our own galaxy. But I think also some of the individual contributions that it made to exoplanet science. We've not only found that there are a lot of these worlds, but we found that they're very diverse. And you know, it's funny how we kind of look at everything through the [00:25:00] lens of our own Solar System, so we call things like hot Jupiters, and super-Earths, and sort-of-Neptunes, and Uranus, and things like that. But the fact that this mission finally confirmed for us not only are there all these exoplanets but some of them are sitting in other stars' habitable zones. So that means that liquid water could theoretically exist on their surfaces and that there are some of them out there that are the same, roughly the same mass and size as Earth. That happened in the past, just what, the past nine years and it's really cool to think about that, that now we know that there are these very good places to look for life and hopefully in some of the next-generation telescopes we'll be able to look at them a little bit closer.

[Emily Lakdawalla]: Of course a lot of us want to find other Earths and find places where there could be life and habitable zones, but the the other cool thing about Kepler is how many strange worlds it's revealed. Places where there is like atmosphere made of vaporized rock and things with [00:26:00] winds that are blowing at practically the speed of sound from one side of the planet to the other because the orbit's so close to their stars. Other worlds that have all different kinds of weird hazes, others that have raining drops of metal. There's just, it's bizarre. There's so many strange places out there. There's lots of fuel for good science fiction stories.

[Jason Davis]: Yeah, I wonder what it says about our ability to imagine things, that science fiction had all of these cool worlds in it and then we found that they basically exist. I mean, it's a pretty cool testament to the human capacity for imagination that we figured, yeah, all these things are probably out there. And now we know that a lot of them are.

[Emily Lakdawalla]: But a lot of the things that we found are things that we never imagined like hot Jupiters in particular just upended all ideas of planetary system formation. We've had to go back to the drawing board multiple times, thanks to results from Kepler, to imagine just how some of these systems could have formed.

[Mat Kaplan]: And then those things that, as Arthur Eddington said, that we can't imagine until we find them. We're not capable of imagining them, [00:27:00] that happens over and over. We heard in at least one of the clips, and we've talked about on this show in the past, how Bill Borucki was called by one of the participants—and very accurately—the father of the Kepler Mission, about the years that he spent in the wilderness trying to convince NASA and others that this would be a good investment. And then, to look back on it now at the end of the mission and see how it is paid off so terrifically. I just wonder if you have any thoughts about that as an approach to doing planetary science. It's not typical is it?

[Jason Davis]: Yeah, it definitely has this same origin story as missions like New Horizon where there was one person who spent a lot of effort at the beginning trying to convince people that it was a doable mission and that it could be done affordably in a lot of cases.

[Emily Lakdawalla]: One thing that's problematic about requiring a lot of missions to propose multiple times and get rejected multiple times before [00:28:00] getting selected is that then you really only have very senior established people proposing new missions. You don't bring in, you know, new people, new in the field with creative ideas, recently educated knowing new ways of doing things, and so it tends to kind of perpetuate the sort of same people leading missions over time and NASA has fixed this slightly through participating scientists programs that can add new early career scientist later on in the process, but it is kind of a selection pressure for older people leading these what are supposed to be these new and riskier kinds of missions.

[Mat Kaplan]: That's an excellent point, Emily. Jason made me think of something else and that is, how much this mission depended on the equally-fantastic advancements we have seen in camera technology over the last, I was going to say 50 years but let's say even 20 years.

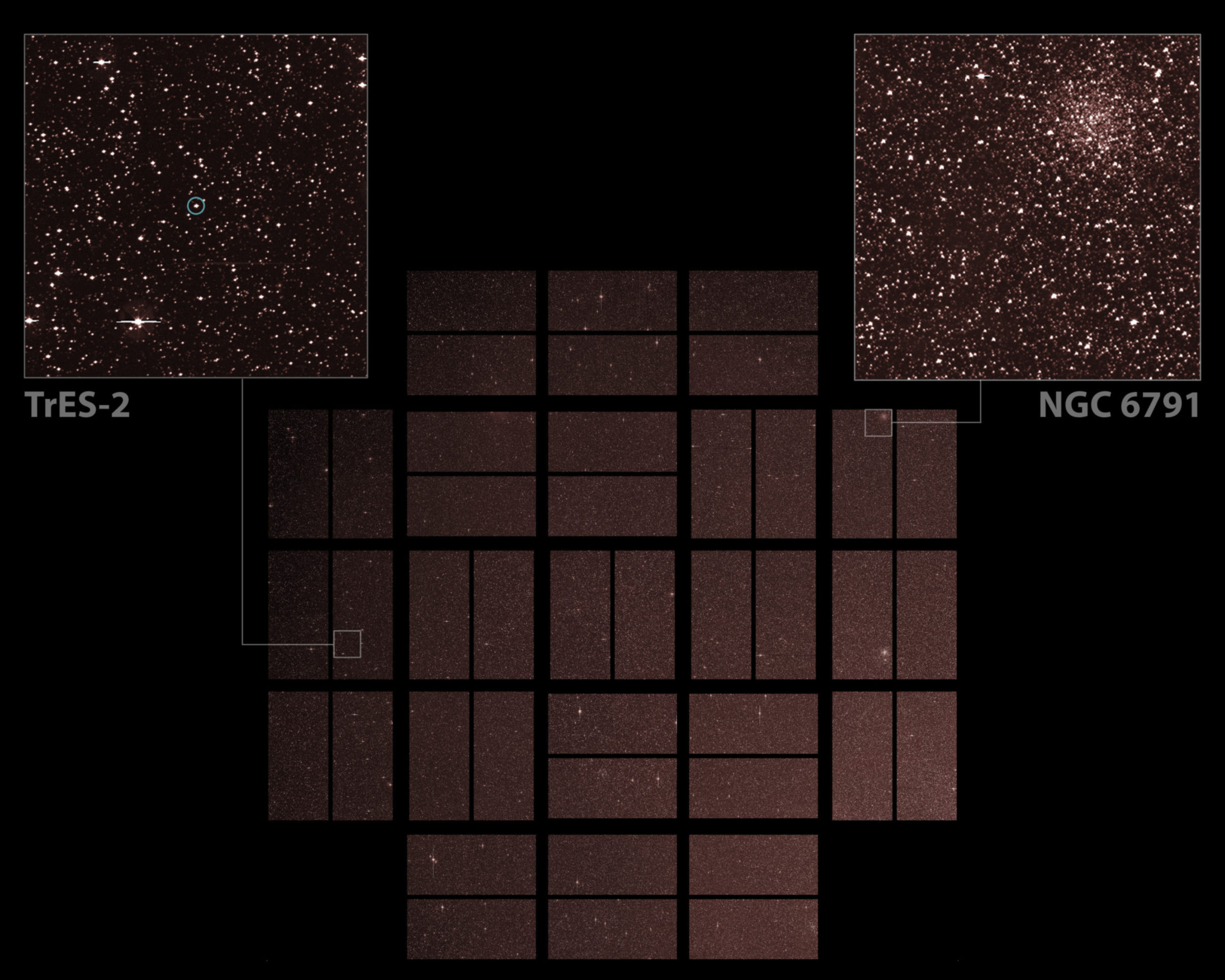

[Jason Davis]: A single a Kepler image is 95 megapixels, which I don't know what smartphones are up to these days... [00:29:00]

[Mat Kaplan]: Not that many

[Jason Davis]: ...12, 14 megapixels. Yeah, and this thing launched in April 2009. At the time, it was the largest space camera ever flown. In researching for this article doing the background on I was trying to figure out if it's still the largest space camera ever flown, maybe Emily knows the answer to that, but this is very difficult to pull off, and it really was groundbreaking in a lot of ways for future missions to use this kind of technology.

[Emily Lakdawalla]: It's true that most deep space cameras, most camera scent beyond Earth and Moon orbit, are really a shockingly-small number of pixels. So I don't actually know the answer to your question—I'm sure somebody listening to this will be able to tell me the correct one—but I'd be willing to bet it's still the the biggest detector ever sent beyond Earth-Moon orbit.

[Mat Kaplan]: I wanna close with one more thing that came out of the discussion, and that was how the Kepler mission was rescued. I mean it really could have ended somewhat prematurely if it hadn't been for some very clever action by the Kepler team back here on [00:30:00] Earth, some brilliant engineering that saved it when that second reaction wheel went out. And this does seem to be a recurring theme, almost a rule, that no matter how well a mission is prepared it goes out there and we run into problems. And maybe more often than not, I won't I won't make a firm claim to that, people find ways to keep them trucking along.

[Jason Davis]: I think you're on the right track. You know, whenever I hear that there's a problem with a space mission—and not talking about just Kepler, say there's a problem with curiosity where it switches to its backup computer—I never worry, and I don't know if that's a bad thing, if I have too much confidence in the scientists behind these. But it just, I think we're spoiled. It started kind of with, well back in the early days of planetary science, but it for me following missions, you know, it started with Hubble that we went up there and fixed the thing like four or five times. And Kepler, no exception, you know, they were able when some of the reaction wheels failed they were able [00:31:00] to use solar radiation pressure to point it in the correct direction. And yeah, I do tend to get spoiled. I think that I'm like, yep, no they'll figure it out though. The engineers always have a solution to the problem.

[Emily Lakdawalla]: As long as you're in communication with the spacecraft, there's hope. It's when the spacecraft falls silent that it suddenly gets a lot more dire. But even when a spacecraft goes silent for months, there's several stories of spacecraft coming back to life, being re-located as they pass closer to Earth, or is it an antenna points in the right direction, then all of a sudden they're recoverable. So even loss of contact isn't a death knell for a mission.

[Mat Kaplan]: I'll only add that this solution via solar radiation: we don't miss a chance to talk about solar sailing do we?

[Jason Davis]: Yes, this is the same force of course that propels solar sails like LightSail. You have a history of space missions using solar radiation pressure in unusual ways, or at least having to account for it. If you don't account for it, it is a legit [00:32:00] force that will push your spacecraft in the different orientations that you wanted it to be in. In this case, of course, the Kepler Mission managers manage to evenly distribute that force across the spacecraft and kind of use that as the third reaction wheel. So, yep, go LightSail, of course.

[Mat Kaplan]: Brilliant. I want to thank you both. It is always fun to talk to you individually. So, of course, it's at least two and a half times as fun to talk to you together, and I look forward to doing it again soon.

[Jason Davis]: Yep. Thanks Mat.

[Emily Lakdawalla]: Thank you, Mat.

[Mat Kaplan]: Emily Lakdawalla is the Senior Editor and Planetary Evangelist for the Planetary Society. Jason Davis is our Digital Editor. Another of our colleagues coming up now as we turn to Bruce Betts for this week's edition of What's Up?. Time for the Halloween 2018 Edition of Planetary Radio.

[Bruce Betts]: (spooky cackling)

[Mat Kaplan]: Yeah, I know most of you are probably hearing this after the big spooky day, but just the same that's when it becomes available and that's when I'm greeting Bruce Betts. Welcome back, Chief Scientist. [00:33:00]

[Bruce Betts]: Good to be back, Mat.

[Mat Kaplan]: I have an upfront comment for you. What we're doing contradicts him. It's George Turner in Boulder, Colorado. He says, "thanks for keeping the show not only interesting and informative and inspirational but a special thanks for not going to the immature humor side. Too many science shows have fallen into that trap, unfortunately." Do you think he's actually heard our show? Rude noises indeed, yeah. Highbrow humor and things high in the sky.

[Bruce Betts]: Woohoo, and the most amazing segues on radio.

[Mat Kaplan]: So tell us what's up there?

[Bruce Betts]: So in the evening, we're losing Jupiter. We're losing Jupiter, man!

[Mat Kaplan]: Oh, no!

[Bruce Betts]: But you still might be able to check it out low on the horizon shortly after sunset in the West, and Mercury is joining in. But also again you'll have to have a pretty clear view to [00:34:00] the Western horizon. But if you look as sunset just starts to fade, Jupiter will be very very bright and Mercury will also look like a bright star but not nearly as bright. But hey the good news for you up early in the morning people is it's going to become the new party in planets and it's starting with Venus. Venus looking super bright in the pre-dawn East and you can check it out hanging out near the star Spica which will look bluish and look like a bright star but not nearly as bright as Venus, Spica the brightest star in the constellation Virgo. Oh and by the way, they'll both be near the Moon on November 6th.

[Mat Kaplan]: Thank you.

[Bruce Betts]: All right. We move on to this week in space history. It's our yearly remembrance of the dog that didn't have a choice but operated bravely, the first creature in space: Laika on Sputnik 2. Dog in space.

[Mat Kaplan]: A Street dog who made good, gave his life, or her life wasn't it, for space exploration.

[Bruce Betts]: Less [00:35:00] conflicted news: 45 years ago, Mariner 10 was launched. Mariner 10 the first spacecraft to give us our close-up views of Mercury. Also the first spacecraft ever do a gravity assist fly by in this case of Venus, which was crafted as we talked about I think last week by the astronomer Bepi Colombo, who now has a spacecraft headed off to Mercury. Okay we now move on to ‘Random Space Fact’. That wasn't really terrifying was it?

[Mat Kaplan]: But it was entertaining.

[Bruce Betts]: All right. On October 29th, 2018, just happened, the Parker Solar Probe broke the record for the closest spacecraft to the Sun, approaching to within 42.73 million kilometers of the solar surface—or what we call the surface, the photosphere—and it broke the record for the [00:36:00] fastest spacecraft relative to the Sun at 246,960 kilometers per hour. Parker Solar Probe will keep breaking its records, culminating in 2024 when it will go about seven times closer than it is now, getting within 6.16 million kilometers of the Sun surface.

[Mat Kaplan]: Wow, and I thought about this, it's like 5% of the distance Earth is from the Sun, roughly in that in that range. So a hot time in the old town in 2024. Yeah, right.

[Bruce Betts]: And way to add a tag-on random space fact.

[Mat Kaplan]: Yes. Absolutely. Okay, we're ready for the contest I believe.

[Bruce Betts]: All right. We asked you: on a typical pair of binoculars, what do the two numbers mean? For example, 10x50 binoculars. How'd we do, Mat?

[Mat Kaplan]: Great response to this, and a lot of people who expressed interest in your book, the book is...

[Bruce Betts]: Really? Cool!

[Mat Kaplan]: Yeah, Astronomy For Kids and we're giving away the first copy of [00:37:00] that with this winner, to the winner of this week's contest I should say. But there will be another one awarded in the new contest. So stay tuned. We're going to let our Poet Laureate Dave Fairchild in Shawnee, Kansas provide the answer. He's not the winner, though. Here we go. "Check your binoculars. Look for the numbers. You'll find that there are two that you really should know. The first is the power that brings things up closer, the magnification of stellar tableau. And as for the second, the aperture number, it's true that in this case the bigger is best. It measures the width of the objective lenses, the light they can gather will here be expressed." Not bad, huh?

[Bruce Betts]: Not bad.

[Mat Kaplan]: I like all of Dave's work, but I think this was particularly, particularly good. Nice rhymes there, Dave.

[Bruce Betts]: A particular challenge to write a poem about numbers on binoculars.

[Mat Kaplan]: No question, and there was no question that therefore that our winner is a first-time winner, Cameron Landers [00:38:00] in Houston, Texas. He indeed said that you were talking about magnification and the second number being the lens diameter of the objective lenses on the, you know, the opposite end, the end you don't look through except for fun. And he adds, "love the show." And he had said, "and its enthusiasm for human exploration of space. Keep up the great work." Well Cameron we'll do our best and you are the winner of a Planetary Radio t-shirt from the Planetary Society's Chop Shop store. You can check it out at chopshopstore.com and a 200 point iTelescope.net astronomy account from iTelescope, that worldwide network of telescopes that anybody can make use of if you have an account. And, maybe most significantly this time, a signed copy of Bruce's book. Brand-new book, Astronomy For Kids, a terrific introduction to the night sky and how to enjoy it. [00:39:00]

[Bruce Betts]: And I talk about things like binocular numbers in there and I've heard it's of interest to adults as well as kids.

[Mat Kaplan]: You heard that from me and probably other adults. But yeah, you heard it here first. TJ Griscoviak, he says, "love the show. Listen every week." He says, "I've been interested in a set of binoculars to help my five-year-old son get more interested in the sky. So thanks for making me dive down the binoculars wormhole online." So we gave them a good start there. I know a good book that your five-year-old might also enjoy their there, too TJ. James Buffamonte in Allegheny, New York. He says, "my old Golden Field Guide says you want to select a pair of binoculars with the best relative light efficiency or RLEs. Are you familiar with that?

[Bruce Betts]: Yeah a little bit, yes.

[Mat Kaplan]: He says, "take the aperture divided by the power squared. So in a pair of 7x50, binoculars the RLE is [00:40:00] 1.02." Says, "you want an RLE of one or more for the best viewing. 7x50s are best for that reason." I don't know that maybe a little bit subjective that recommendation at the end there but I thought that was interesting. From Naharari Rao in Sugarland, Texas, with a decent set of binoculars, 7x35—which is pretty common, that's what I've got. You can see he says roughly about 100,000 stars as opposed to 3,000 stars with your naked eye. I assume this is, you know, in a pretty dark place and under clear skies, Bruce?

[Bruce Betts]: And I assume he counted. Yeah, that would be under dark sky conditions.

[Mat Kaplan]: We'll send that to our crack fact-checking squad, as soon as we hire one. Finally this from Martin Hajaski in Houston, Texas. He says, yeah, okay, that's what most people think the numbers mean, but he says "though I guess we could also refer to the first number as the Kaplan number and the second number is the Betts [00:41:00] number but then the universe would be more perfect than it already is, right?"

[Bruce Betts]: Right! And my number is bigger.

[Mat Kaplan]: Thank you Martin. That's it. We're ready to go on.

[Bruce Betts]: All right. So before the Parker Solar Probe broke the records for closest spacecraft approach to the Sun and fastest spacecraft relative to the Sun, what spacecraft held those records? Held both of those records? Go to planetary.org/radiocontest.

[Mat Kaplan]: You have until Wednesday, November 7, at 8 a.m. Pacific Time to get us the answer to this one. And if you are chosen by random.org and have the right answer, well there's a copy of Bruce's book waiting for you along with a 200 point iTelescope.net account And a Planetary Radio t-shirt. A pretty wonderful prize package, if I do say so myself.

[Bruce Betts]: Everybody go out there, look up in the night sky, think about the inverted view through [00:42:00] binoculars when you are upside down. Thank you, and good night.

[Mat Kaplan]: That's Bruce Betts, the Chief Scientist for the Planetary Society. He knows which way is up and he joins us right side up every week here for What's Up? Here's something new: you can now read complete transcripts of new episodes of Planetary Radio. We actually started this with last week's show they are on the individual episode pages at planetary.org/radio. Planetary Radio is produced by the Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by its farsighted members. MaryLiz Bender is our Associate Producer. Josh Doyle composed our theme which was arranged and performed by Peter Schlosser. And for the first time you can listen to the entire theme; same place, planetary.org/radio. I'm Mat [00:43:00] Kaplan. Ad Astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth