Planetary Radio • Oct 07, 2020

Protectors of Earth! (and Other Worlds)

On This Episode

Mike Gold

Executive Vice President for Civil Space and External Affairs at Redwire

Lisa Pratt

NASA Planetary Protection Officer

Alan Stern

New Horizons Principal Investigator

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

Protecting worlds like Earth and Mars from microscopic invaders carried by human and robot visitors was just one of the scores of topics covered at this year’s Humans to Mars summit. Mat Kaplan moderated a panel featuring planetary scientist and New Horizons mission principal investigator Alan Stern, NASA associate administrator Mike Gold, and NASA planetary protection officer Lisa Pratt. Planetary Society digital editor Jason Davis shares the fascinating 40-year timeline that can be found in the Society’s September equinox edition of The Planetary Report, and Mars shines bright in our What’s Up segment.

Related Links

- NASA’s Office of Planetary Protection

- NASA’s Planetary Protection Review Addresses Changing Reality of Space Exploration

- NASA's Office of International and Interagency Relations (OIIR)

- Explore Mars 2020 Humans to Mars Summit videos

- The Downlink

Trivia Contest

This week's prizes:

A Planetary Society KickAsteroid r-r-r-r-rubber asteroid!

This week's question:

To celebrate its 40th anniversary, how many 25-meter dishes make up the Very Large Array in New Mexico? There could be 2 possible answers, either of which will be accepted.

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, October 14th at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

What 3 Apollo spacecraft call signs were later used as names of Space Shuttle orbiters?

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the 23 September space trivia contest:

What is the largest rock returned from the Moon by Apollo astronauts? Either its official name or nickname is acceptable.

Answer:

The largest rock returned from the Moon by Apollo astronauts was officially Lunar Sample 61016, but is also known as Big Muley.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: An all star panel protects earth and Mars, this week on Planetary Radio.

Mat Kaplan: Welcome, I'm Mat Kaplan of The Planetary Society, with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. There's planetary defense, which we talk about a lot because it's important, but that's about protecting just one world from catastrophe, our own. Whereas planetary defenders worry about big rocks, planetary protectors focus on microscopic threats and they consider all worlds, or at least all that have even the tiniest chance of supporting life. We'll talk with three heroes in this evolving field, including NASA Planetary Protection, officer Lisa Pratt. Also, Acting Associate Administrator of NASA's Office of International and Interagency relations, Mike Gold, and old friend of the show, Alan Stern.

Mat Kaplan: Alan recently chaired a NASA Independent Review Board that looked long and hard at planetary protection. Of course, we've also got another fun session with the chief scientist, Bruce Betts, and we are moments from a quick visit with Planetary Society Editorial Director, Jason Davis. It's a whole lot of show. Jason is also one of the prime movers behind the Downlink, our weekly newsletter. The October 2nd issue starts with a shot of Jupiter that you might swear was captured by Voyager Galileo, or Juno. No, it was the venerable Hubble Space Telescope that snapped this stunning image a couple of months ago. Europa makes a cameo appearance. Here's a very brief sample of other Downlink stories. A new look at radar data from the European space agencies, Mars Express orbiter helps the case for saltwater lakes hiding under the red planet, Southern pole ice.

Mat Kaplan: Back at NASA, the agency has been forced by the pandemic to delay the launch of Dragonfly toward Saturn's moon, Titan, by a year to 2027. The agency and its partners are still looking for the source of a small air leak on the International Space Station. The men and women living there aren't in danger, but this is got to be irritating. Much more a way to at planetary.org/downlink. Let's go to Jason Davis. Jason, yet another beautiful issue of The Planetary Report, but this one really is special because it's a celebration, isn't it?

Jason Davis: Yeah, it's our 40th anniversary. We've been celebrating all year and we wanted to dedicate an entire issue of The Planetary Report to our 40th, and this is the one, our September issue. We've got a lot of things that we hope members, especially long time members will join this one.

Mat Kaplan: I am told that you are responsible for, what is sort of the core of the star of this issue, and it is this multi-page timeline, that traces, not only the history of The Planetary Society, but the history of planetary exploration.

Jason Davis: Yeah. We had a brainstorming meeting and it's in pandemic time. Everything is shifted in my brain, so it seems so long ago, but we had a meeting to talk about the way we were going to go about this for this issue. There were so many stories we wanted to tell. Everyone was just pitching ideas and we only have so many pages in the magazine. Finally, we said, you know what? Let's just lay all the stuff out in a timeline. That's something that would really be helpful on our website to have for years to come, just a high level overview of all the cool stuff we've done. Then we started to realize, well, it needs context. Can't talk about what The Planetary Society was doing at any given time without talking about what was going on in the world of space exploration.

Jason Davis: That's where we came up with this idea of this running timeline, two pages per decade, and we would put beneath it all the events that were happening in the space world and everything that was happening at The Planetary Society. I should say, by everything, that is not actually the case. There's just so much. We had to be selective and I'm sure I might get a few emails or letters. That's okay. Unfortunately, we couldn't fit everything.

Mat Kaplan: I like how you mentioned upfront when you introduced this, that there were at least 35 missions, that there wasn't room to mention here. On the other hand, above the timeline, this show, Planetary Radio, made the cut and I'm very proud to be represented there.

Jason Davis: Well, we had to represent our flagship podcast and radio show. Of course, Mat.

Mat Kaplan: Your only podcast and radio show, we have to mention. It's great reading though. Yes, it is for our members, but it is also available of course, to everybody in digital format at planetary.org. You can look for The Planetary Report there. There's one other thing. It is clearly just a reprint. It is lifted right out of some early issue of this magazine. You know what I'm talking about.

Jason Davis: Yeah. We plagiarized ourself here. Easy way to feel content in this thing. No, Bill always has a column that says, is your place in space column? He writes a little intro. In our very first issue of The Planetary Report in 1980, Carl Sagan wrote this beautiful essay called The Adventure of the Planets. It really lays out a lot of the justification for why The Planetary Society exists, what we're going to be doing as an organization. We were like, let's reprint that and put it next to Bill's column. So, it's like this full circle 40 year moment. Also, while we were at it, we noticed, on the very first issue of The Planetary Report, we had this beautiful picture of Saturn from Voyager 1 on the cover. We went back into our archives and we were looking to see if we can find that same image, and we couldn't find it.

Jason Davis: As far as we knew, it had not been reproduced digitally. I wrote to Bjorn Johnson, he's an image processor, and said, "Hey, can you go back in the Voyager archives, look for that original shot that we used on the cover and see if you can reprocess it somehow," and he did. I have to say, I mean, I'm biased here, but I think he did a fantastic job in that. So, we put that same picture on the cover, but it's a lot sharper and crisper than the one that appeared in 1980.

Mat Kaplan: It's gorgeous, and it's another example of how planetary science missions keep on giving long after the spacecraft are gone. I got to make one other comment about this essay by Carl Sagan. It is, of course, wonderful because it's written by Carl, but I love the closing. There is an address, we can be contacted at, and there's a P.O. BOX 3599. Don't write to us here. That's like three headquarters ago, but somebody added in brackets, like many proposed interstellar radio messages, the post office box number is the product of two prime numbers, 59 and 61. Are we not nerds?

Jason Davis: Yeah, you can really see the evidence there from the beginning of the scientists, the nerds, the geeks at work, and it's just great. There's just so much of that in our history that was there from the beginning. You can see.

Mat Kaplan: And on into the future, because even though it doesn't have anything for The Planetary Society, because we're not there yet, you continue the timeline right off into the future with lots of planetary science highlights to look forward to. Again, this is all at planetary.org. Our members, the members of The Planetary Society should now, by now already have gotten their beautiful print versions. Thank you for putting this together, Jason. It's great, and I'm honored to be a fellow nerd.

Jason Davis: Thanks, Mat. Always honored to be a fellow nerd with you too.

Mat Kaplan: That's Jason Davis, Editorial Director for The Planetary Society, and responsible for this terrific timeline in The Planetary Report. Long-time listeners know how much I enjoy attending and contributing to the Humans to Mars Summit, the big annual gathering produced each spring by Explore Mars in Washington, DC. Then came 2020, after delaying H2M to the fall, CEO and co-founder, Chris Carberry and his team were reluctantly forced to make this year summit virtual. That happened during the first week in September, and it still attracted hundreds of leaders and explorers. I got to moderate some terrific virtual panel discussions.

Mat Kaplan: You're about to hear most of one, it starts with brief presentations by the panelists and then moves into a terrific wide ranging discussion of planetary protection. Here's a little glossary that might be helpful. COSPAR is the International Committee on Space Research. ISRU is In Situ Resource Utilization, that is making what you need for exploring and exiting a world out of the stuff you find there. BSL is Biological Safety Level with BSL for the highest. PSR is reference to those permanently shaded regions found in features of the poles of the moon, where we found water ice, and IRB is Independent Review Board, like the one Alan Stern was asked to head by NASA. Okay, here's my session with Alan, Mike Gold and Lisa Pratt on the morning of September 3rd, 2020.

Mat Kaplan: I am thrilled. I'm very proud to be once again, part of the Humans to Mars Summit and very proud to be able to talk about this topic. Like most of you, I get a lot of newsletters, including updates from wired magazine, and there is an item that caught me by surprise last week. It summarized the surprising results of The Tanpopo astrobiology mission on the International Space Station that was a Japanese effort. Several species of bacteria survived three years in space, not inside the warm, airy confines of the ISS, but exposed to hard vacuum and radiation. This reminded me of that famous quote from renowned planetary scientist and astrobiologist, Jeff Goldblum, Life Finds a Way. That, of course, is the fervent hope of all astrobiologists and the recurring nightmare for anyone who wants to protect our own and any other biospheres from contamination.

Mat Kaplan: Planetary protection has been in the news for other reasons in recent months. It promises to continue as a major concern. So, we have brought together three outstanding leaders to talk about it. First is Lisa Pratt, biogeochemist and astrobiologists, Lisa Pratt, became NASA's Planetary Protection Officer. In 2018, rumor has it that about 1400 candidates applied for that job, maybe partly because it has the coolest title in the solar system. She leads NASA's Office of Planetary Protection. Lisa is also provost professor emeritus of earth and atmospheric sciences for Indiana University Bloomington, where she has been a member of the faculty for over 30 years, so welcome Lisa.

Lisa Pratt: Hey, thank you very much. Chris, Mat, wonderful introductions to a topic that for a long time seemed somewhat forgotten, and now it's really front and center. I think with the launch of the Mars 2020 mission per se, we really are no longer talking about if sample-return is going to happen. We're talking about when, and we'll be excited to watch that mission land in February and get started on the first leg of the integrated NASA-ISA return campaign. Our obligations to the international community and our responsibility to NASA as an agency derive from the Outer Space Treaty. We often point to two articles in particular, Article Six and Article Nine as the two areas where we keep an eye on the original treaty language. Then we pay particular attention to the guidance that comes from COSPAR. COSPAR is the designated official arm of COPUOS in the UN for dealing with planetary protection, as well as a number of other space exploration issues.

Lisa Pratt: Within the COSPAR organization, there is a panel on planetary protection that operates in both public sessions and executive sessions to formulate international guidelines. NASA, as an agency, participates in the COSPAR process, and currently, Jim Green, the NASA chief scientist is our representative to the COSPAR panel sometimes. We are following COSPAR, and sometimes COSPAR is following NASA in terms of responding to changing technical capabilities and scientific discoveries. As Mat mentioned a minute ago, there's a great deal of change taking place at NASA, trying to make sure that we're synchronized with the changes occurring around us, and that we're balancing our scientific exploration with all of the new stakeholders and players in space exploration.

Lisa Pratt: You'll see the two new NASA interim directives, known as NIDs, one for the moon and one for Mars. These documents have a one year lifespan, and both of those documents, now that they've been reviewed and officially approved and released by the agency, they will now be looked at in-depth, not only by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, but any number of organizations that have scientific expertise on either the moon or Mars. By the end of the lifetime of those two documents, next July, we will be in a position as an agency to either fully flesh out those documents as a complete policy and implementation documents, or we will hold them back and take another look at them. It's an ongoing process. Below that, a first ever NASA standard for planetary protection, so again, lots of review and lots of change.

Lisa Pratt: Of course, so I think we're all aware, and we've had a little bit of an introduction just in the first few minutes to the excitement around the MSR, the Mars sample-return mission architecture. This is our first time since Apollo to really begin to wrap our arms around and come to grips with backward planetary protection. We have a lot of experience, particularly for Mars with forward contamination and how we reduce the risks if we carry a hitchhiker with us, and introduce it into a habitable Martian environment. But we have very little recent experience with backward planetary protection, and we've never, this will be the first time we bring a sample back from a planet that we consider to be habitable for earth life. Therefore, a planet that could Harbor present day life as we know it on earth. So, lots of excitement around that campaign and understanding how we will handle that right hand leg of this architecture.

Lisa Pratt: Once we launched samples from Mars, rendezvous with a European Return Orbiter, and then do the landing of the sample canister on earth. This is just a snapshot of the moon NID, which lays out two new NASA Planetary Protection categories termed 1_L for lunar, and 2_L, again, the L representing lunar. These are not COSPAR categories, but they are being looked at by The Planetary Protection panel, and they will either move in a similar direction or develop their own revision of the current categorization scheme. With that, welcome, happy to be part of this wonderful group.

Mat Kaplan: Another great introduction to this topic. Thank you very much, Lisa, and I hope that we can talk a little bit more about those so-called NIDs, the NIDs later in the conversation, let's go on to our second member of the panel today, someone that many of you have probably heard of because of his many activities in deep space exploration, mostly robotic exploration, but has a deep interest in human exploration as well. Planetary scientist, Alan Stern, is associate VP for the Southwest Research Institutes Space Science and Engineering Division. He's a member of The National Science Board, and of course, is principal investigator for the triumphant New Horizons mission that is now speeding toward interstellar space. He served as chair of NASA's 2019 Planetary Protection Independent Review Board. Alan, welcome.

Alan Stern: Thanks, Mat. Great to be a part of this great panel. I think Lisa really did a great job of kicking it off and framing it. I'll give a little bit of background. As Mat said, a little over a year ago, the administrator delegated the job of taking a thorough new look at Planetary Protection to Thomas Zurbuchen, the associate administrator, for science at the agency. This Planetary Protection Independent Review Board was formed. I was asked to chair it, and we operated a group of about a dozen scientists and engineers, and some folks from Commercial Spaceflight. We operated from late June until early October. Had several in-person meetings around the country and a large number of telecoms.

Alan Stern: In addition, we met with dozens and dozens of experts and took a thorough look across the board at planetary protection and how it could be brought, really up into the 21st century, because there hadn't been a thorough look at all the aspects of how planetary protection is mechanized and handled the new technologies, the new players that on board, that whole landscape, there hadn't been a look at that in decades, believe it or not. We made about 80 findings and recommendations to the agency reporting out last October. Then since then, we've gone and explained in detail to the NASA Advisory Council, to NASA advisory groups, to COSPAR to ISA, to JAXA, to other agencies as well what our findings and recommendations are.

Alan Stern: Maybe as a headliner, particularly for framing the conversation today, one of the things that we found is that Dr. Pratt, who we just heard from and her Planetary Protection Organization have really made great strides forward in just the last few years already, even before the work of the PPIRB, to really move Planetary Protection forward into this new era with new players and new technologies, and to take a very pragmatic look at how we can do it better, and we complimented what Lisa and her team, complimented the agency for this forward-looking approach that involved forming the PPIRB and the subsequent work that's taken place since then as well.

Alan Stern: As I said, we made a wide variety of findings and recommendations and everything, from how we should categorize different worlds and different terrains on those worlds, to the new technologies that should be involved, to new processes and to how the new players ranging from new countries participating in planetary exploration, to private entities, can be brought into the fold, if you will, so that we do this as well as we possibly can. Then we also recommended that it not be very long, again, it shouldn't be decades, but that NASA set up a process to re-evaluate planetary protection from time to time each decade, perhaps twice a decade so that we don't get in a position where a lot of the thinking is actually from a previous generation.

Alan Stern: The development of spaceflight and the development of technologies, both for spaceflight and for doing biology are just moving too fast for that. With that introduction amount, Mat, I'll give it back to you and say how much I'm looking forward to this morning's panel.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, Alan. That was great. I'm going to take us right to the last of our three panelists today, and that's Mike Gold, who is the Acting Associate Administrator at NASA's Office of International and Interagency Relations. He is also responsible for providing strategic direction to the Office of the General Counsel, and supporting NASA's low earth orbit commercialization efforts. Before joining NASA, Mike was the Vice President of Civil Space at MAXAR Technologies. I first met him during his 13 years at Bigelow Aerospace.

Mike Gold: Thank you, Mat. Appreciate the opportunity to address Human to Mars Summit. Thanks to everyone from Human to Mars and Chris Carberry and the team for setting this up, and of course, my panelists. You know that, fellow panelists, Lisa mentions that she's a professor. I learn from her every day. I don't have to pay tuition, so it's a great deal for me. I've been complimenting Alan. I do just want to begin by setting some context that part of the reason, and look, Lisa, and Alan and I, we always thought that planetary protection is cool, but part of the reason that it's getting so much more attention now is because of the Artemis program, and that we are moving forward to the moon. By 2024, we'll have the first woman and the next man on the lunar surface.

Mike Gold: This is where ISRU is going to become very important, that any successful exploration program really depends upon the ability to live off the land, particularly if it's going to result in a permanent sustainable presence, which is the goal of Artemis. If we're going to have successful ISRU, planetary protection actually becomes very important to ensure that those resources can be utilized for everything from drinking water to fuel, etc. we just want to provide that context, and again, point out ISRU because it's a piece of planetary protection that sometimes doesn't get all the attention that it should. I think the progress that we've made on this issue was a great example of how federal advisory committees can play an important role in discussing policy and in making progress on very important issues.

Mike Gold: Let me tell you, not easy getting industry, scientists, academics together in a room to all agree on what needs to be done on an issue like planetary protection. This is where Alan Stern just did a singular, an exemplary job in herding all of those cats to come up with some extremely productive and helpful recommendations for the agency, and eventually the world to implement. But I think we shouldn't take for granted that kind of success, that not only did you have a diversity in the kinds of organizations being represented from again, scientific to industry, to academia, but even among the industry participants, there are a wide variety of views from traditional established companies, to new space entities, and again, kudos to Alan for working through all of these issues, and kudos to his team.

Mike Gold: We shouldn't take this for granted, that there was a lot of time spent by the Planetary Protection Independent Review Board on this topic. As Alan mentioned, there were meetings throughout the country, and no one's making money off of this. I just want to say thank you to the members of the PPIRB from academia, from the private sector, from the scientific community who donated their time to support this incredibly important activity that I think had a terrific result. That result were the NIDs. Lisa did great job describing those, and again, she's forgotten more about this than I'll ever know, so let me just say that I think the NID did a terrific job, relative to Mars, in ensuring that we are going to take a balanced approach that takes account of absolutely science, but also sustainability and safety, human exploration, commercial activities, just like it was challenging to take all of these using the PPIRB, it will again be challenging to balance all of these views as we move forward, but absolutely necessary.

Mike Gold: We'll need more cooperation in the public and private sector, science and academia, as we move forward to Mars, because really what the Mars NID was, in the end, was saying that we need to balance, we need to establish a process based on what we've learned in the past and move forward and we'll be gaining a lot more information and having many more conversations in the future. Again, Lisa did a great job describing what we're doing on the moon. My one other comment relative to the moon is, and you'll note in the moon NID, that there was a reference to space heritage sites as we look at the Apollo landing sites. I do just want to point out because there's been discussion in this issue, that the reason that those human heritage sites, space landing sites appeared in the NID was due to science, that there are biologics potentially that would be worth studying, and that's why it was mentioned.

Mike Gold: Relative to preserving space history and the space artifacts, that's more in the purview of what we're trying to accomplish with Artemis Accords, where due to their historical importance, we want to preserve and protect historic landing sites, historic artifacts on the moon and other celestial bodies. Whereas the NIDs mention these sites, but are doing so because of the potential importance to science. I just wanted to clarify that. Also, when the Artemis Accords, we won't specifically mention, or at least I don't believe when we have final texts, that there will be explicit call-outs to the sections of the Outer Space Treaty that Lisa had mentioned, but I do want to emphasize that it's very important that the Artemis Accords are there to reinforce our commitment to all aspects of the Outer space Treaty, including preventing harmful contamination, but rather than spill a lot of ink in Artemis Accords on that topic, we've already got a great process with COSPAR to go through, and we thought our time and resources would be better spent dealing with the issue there because there's a terrific existing framework.

Mike Gold: Of course, I can't go through any presentation without making a science fiction reference. When you look at sci-fi, there's often a lot of conflict. As a matter of fact, for those of you who saw the National Geographic, Marsho, a lot of it is about the conflict between the private sector and the government and science versus commercial as we explore Mars. That's why so grateful and appreciative of all the efforts that Lisa has done, that Alan has done, that the members of the PPIRB did to come together as a community, because we're going to do better when we work together. The more science that's done, the better our commercial activities will be. The more human exploration that's done, the more science will be able to do. The more commercial applications that are done, the more discoveries we will have, the more we will learn, fueling both science and exploration.

Mike Gold: We're a false dichotomies. The question isn't science or human exploration or government or private sector, it's both. We need to all work together and we will all enjoy the benefits. That way, we can create a world that is much less like Star Wars and more like Star Trek. With that, let me just say live long and prosper, and I look forward to the conversation.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, Mike, LLAP to you as well, even better stuff for my Human to Mars Planetary Protection panel, including opening up lunar exploration is coming right after a break. I hope you'll stay with us.

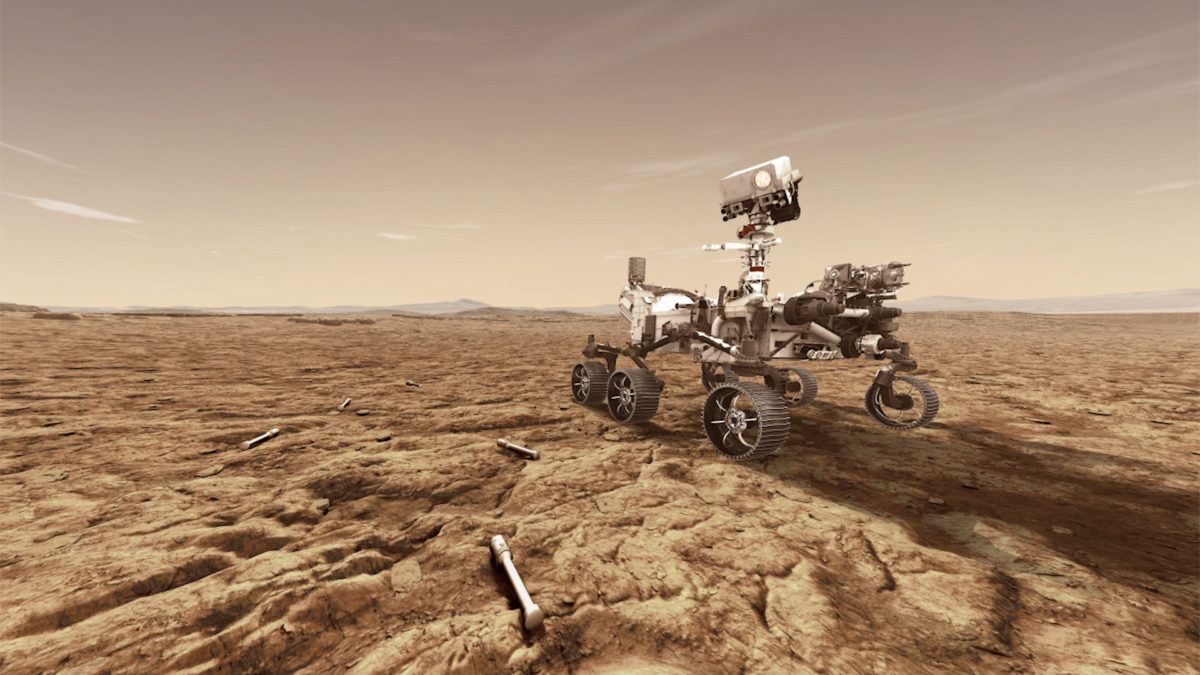

Bill Nye: Perseverance is on its way to Mars. Bill Nye, the Planetary guy here, I'll be watching when this new Mars Rover arrives at the red planet on 18, February, 2021. Would you and a friend like to join me? We'll put you up in a four star hotel, enjoy a great lunch conversation about space exploration and share our excitement as the rover descends to the Martian surface. Then we'll send you home with a Mars MOVA Globe sign, why me? Visit omaze.com/bill to enter and support The Planetary Society. That's omaze.com/bill. I look forward to welcoming you as we return to Mars.

Mat Kaplan: Before we talk a little bit more about some of the topics that our panelists have brought up, one of them, Mike, you talked a lot about the difficulty of reaching consensus among all the different parties involved within the United States. Then of course, there are international, both partners and competitors around the world, and we have a question that came in from Jeremiah Hennigan that directly addresses that. So, I'll throw this to you, but Lisa, Alan, please feel free to jump in. How will the USA ensure and guarantee that our near peer competitors, think China, he says, will adhere to the rules and regulations that the rest of the global community, or at least that we feel, are appropriate for protecting the solar system and ourselves?

Mike Gold: Yeah. Before we get to the rest of the world, I think we always need to begin by getting our own house in order. That's why, again, I appreciate the great work that Lisa and Alan and everyone in the PPIRB did to ensure that constantly updating our policies. We're never going to be done with that. We're always going to have new technologies, we're always going to have new programs and new possibilities, and that's why we have to treat these rules as ultimately organic, and we're always going to be learning and building new regulations. What I always fear is regulations dropping behind technology, so I appreciate everyone working on that, and I think we've done that successfully here in the US. Then when you go outside to organizations like United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, or to COSPAR, I think we've enjoyed a good relationship, and that US leadership has been welcomed there.

Mike Gold: However, ultimately, in terms of people abiding by the rules and trying to preserve the environment, it's a question we get all the time in international law, is how do you enforce anything? In the end, as we turn to the Outer Space Treaty, and it comes down to consultation that we can talk to each other and we can be transparent in terms of what we think needs to be done and what others are doing. This is where there are concerns, that we are very public relative to what is being done, relative to planetary protection and the science that has gone into our determinations. It would be terrific if China and every other nation would do so. That's not occurring now completely. Our hope is that all of those processes have been followed, but public presentations, public verification, transparency is so important. All we can do in the end is lead by example. We will embrace our values of transparency, of protecting science, and hope that others will follow. But I'm very interested in Lisa's thoughts on the issue as well.

Lisa Pratt: Mike, I really like what you just said, and I'll add one new piece of information to NASA ensuring that we're doing what we say others should do tomorrow, on Friday. We will have the first meeting of the new Committee on Planetary Protection, the CoPP at The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. That group will now serve in an oversight and advisory role for the Office of Planetary Protection. That's really important because that includes access to individuals who have expertise in medicine and across the health sector and going forward. When we start to think about particularly what we're bringing back to earth. This is way outside NASA's normal realm of expertise, and we need to involve that wider community. With regard to the international settings, I think Mike also got that just right.

Lisa Pratt: We have COSPAR, and COSPAR has been in place and has been a wonderful safe haven for conversations across international boundaries that are often barriers to communication. The most recent public meeting of the Planetary Protection panel, COSPAR's panel, that was held on the campus of The United Nations in Vienna, and I sat next to the delegation from China. There are opportunities through our shared science values and goals to talk in ways that are in the interest of all nations all of humanity. I think the science platform provides that venue in a way that almost no other platform can.

Mat Kaplan: Alan, did you want to get in on this discussion of the international aspects?

Alan Stern: Well, I'll just said a couple of words because I think Lisa and Mike handled it very well. I will say that, first of all, and we just heard this from Lisa, the Chinese are participating in COSPAR, and I think that's very important. Unlike in some other domains, in the case of planetary protection and planetary exploration, we don't really have nation states that are real players. I think everybody's on board and has been on board for a long time. Although there are differences in implementation, I don't think that they're deep differences in intent, and that's a very good starting place to be at. So, we can work to improve, but we don't have really deep problems to try and solve. I'm an optimist on this. I think the wound is going in the right direction with regard to both planetary exploration and planetary protection aspects of that exploration.

Mat Kaplan: Lisa, I want to go back to those NIDs, the NASA Interim Directives, and particularly the second one there. Mike talked about that may be the key word is balance, that finding that balance, striking a balance between the need to explore and discover new science, including the search for life on Mars, of course, maybe primarily, and protecting that biosphere. I just wonder, in particular, about what we will be able to do now that we have Perseverance on its way there, how has this new balance being struck as we look at Perseverance that will actually actively be looking for places that might have evidence of past or dare we say, current life on Mars and eventually returning it?

Lisa Pratt: Mat, I don't know where to start on that sequence of questions and topics, but let me just say that we have a remarkable opportunity right now to use the moon as a proving ground before we go to Mars with humans. We almost couldn't design a better place to test technologies and to close knowledge gaps. Then, at the moon, with regard to the contamination that isn't inevitably carried by humans and their agriculture. We've got perhaps 30 years, maybe a little bit less, depending on the activities in the commercial and private sector, but we can do things at the moon to understand how microbes, and potentially even viruses or just biological agents like toxins and prions, how do they hold up if they get outside the comfort zone that is created by the habitat or the interior of a space suit or a roving vehicle?

Lisa Pratt: We've got a little time, and that approach, the moon as a proofing ground on the way to Mars, is now deeply embedded in the planning and architecture for the Artemis campaigns once we get past the robotic phase and we're ready to do human landing systems to the surface of the moon. It's very much a part of the agency, and I anticipate a great deal of funding now flowing into the research community, not just at NASA, but at National Science Foundation, maybe even over on the human health side to really help us get better at understanding how the human microbiome and the health of our astronauts responds to low gravity environments like the moon or Mars, or responds to zero gravity environments such as in transportation, and then how we would detect and monitor any leakage or release of those microbes into the Martian environment. We can land at the moon. It's a really important opportunity.

Mat Kaplan: I'm so tempted to ask now, and I think I will just for humor value. The Martian, that great book and film, wouldn't he have been prosecuted when he got home for his gross contamination of the Martian surface?

Lisa Pratt: I hope you're not asking me. Mike Gold's the lawyer. Mike Gold would be the prosecutor.

Mike Gold: I think you've just come up with the perfect sequel to The Martian. It's a space law movie, all about Article Six in the Outer Space Treaty. It will be a huge hit in the Box Office, I'm sure.

Mat Kaplan: I have no doubt. I'll wait for the movie.

Mike Gold: [crosstalk 00:37:50] if I can answer that question subjectively, just briefly, because I think Lisa touched upon it, that the reason that he's not going to be thrown into Outer Space Treaty jail is, I hope in that future time that we learn from our experience on the moon, develop policies and procedures that make sense, which is why, by the time Matt Damon got to Mars, that he did not get prosecuted on the way back. We talked about uniting government and industry, uniting public and private sector, uniting human exploration and science, but also uniting the moon and Mars that, that's so important, not just for planetary protection, but for development of technology, for the entire exploration of architecture.

Mike Gold: We are very fortunate to have a moon to practice on, to get to Mars, and it's through that experience that, not only the subsedent technology of Artemis will be developed and our substantive experience, but also the policies, the rules, even the business cases moving forward.

Mat Kaplan: Lisa, I want to come back to also something else that you mentioned, backward contamination. I'm still somebody who is haunted by watching The Andromeda Strain, the film version of that book, what? I don't know, 40, 50 years ago. You mentioned prions. They are specifically mentioned in the second NID as a possibility. What did we learn? What lessons were we taught by the experience of Apollo in making sure that we take very good care of any samples that are brought back to earth? As we've been asked by a couple of our participants today, should samples be brought back to the surface of earth, or maybe they should end up on something like the ISS?

Lisa Pratt: That certainly is a debate that has played out repeatedly at NASA and in the wider scientific community. I think the majority of evidence points towards the safest activity being to keep the samples contained, contained, contained, contained, four layers of containment, which is the current Mars sample return architecture, and to get those samples as quickly and safely as possible into an advanced receiving facility, a facility designed specifically for extraterrestrial materials. This is not the typical BSL-4 type of sample, although it will take a BSL-4 type of facility in terms of safety and security. But again, I absolutely concur with the current architecture, which is the only place we have the sophisticated tools, the containment systems, the air handling systems, and the power to do the analytical work to characterize those Martial materials for any evidence of a biological activity in the past or in the present is here on earth.

Lisa Pratt: Every place else, we make do with minimal power, we make do with instruments and techniques that can be transported to someplace else. We need to do it here. We need to have those samples available to the broadest possible subject matter expertise, that's the International Community. I think we're doing the right thing. Let's face it. Better to have the first samples returned from Mars, small contained materials, because if we don't look first at a robotic MSR, then the first samples we return from Mars will be astronauts. I don't think that's a good idea.

Mat Kaplan: Mike, Alan, anything to add?

Alan Stern: I would like to add something. I'd like to add a little bit of planetary science perspective on this whole problem. We've known now for decades that the earth and Mars exchange samples through natural processes, primarily impacts, large energetic impacts onto the surface of Mars, that blow material, not only off the surface, but into orbit around the sun, and then we find some of that material in the form of Martian meteorites on the earth. That's completely uncontrolled by any planetary protection protocol. It's been going on for billions of years, and the earth has been doing pretty well in response to that. It doesn't replace the need for the work the Planetary Protection Office under Lisa is doing, and the care that we want to take from Mars sample-return first robotic, and then with humans.

Alan Stern: But it does provide some important context, because these kinds of sample exchanges have been taking place through natural processes, no controls of planetary protection. As I said a few minutes ago, the earth has been doing just fine.

Mat Kaplan: Which makes me think of the possibility that we're all really Martians, but we won't get into panspermia in this session.

Mike Gold: That being said, if Mars does violate any of our NIDs, as a lawyer, I will go after it.

Mat Kaplan: This guy will have something to say about that.

Mike Gold: There you go. Yeah, we got so far without a Marvin the Martian reference. Can I just say one other point?

Mat Kaplan: Sure.

Mike Gold: Another debate that we've often heard in the space community is human space exploration versus robotics. This is another example where it should be human space exploration and robotics, and it's appropriate I went after Lisa, because all I'm doing is just echoing what she said, that it's so good that we're going to do a robotic mission before the human mission, because that informs the human mission, and here again, we see that it's not an either or, it's an and. There's such tremendous energy and importance between our robotic missions and what we're learning from that, to help inform and ensure the safety of our human spaceflight operations.

Lisa Pratt: In fact, it's one of the basic tenants of science. We do science sequentially. Every experiment, every observation prepares us for a better experiment and to predict the next observation. We need to be sequential so that we don't have a misstep somewhere along the way, and I think that's exactly what the NASA ISA Mars sample return campaign is all about. We're ready to do this. We have the technology, we have the capability. As Alan very wisely pointed out, we've been swapping material with Mars for a long time. If the sun's gravity has any influence on where things land, there's a lot more Martian material coming at us in this direction, than there is earth material being thrown back in the other way. Wouldn't it be great if we could find both Martian and earth meteorites on the moon and have a look at how they record those original environments in a very cold, if they're in the cold spots on the moon, to see what those meteoritic materials look like if they're not landed on earth, where earth contamination immediately overprints the extraterrestrial signature, because we're awash in organic matter on the earth.

Lisa Pratt: It's very hard to get a pristine meteorite samples so that we can really give it our best in-depth evaluation for evidence of extraterrestrial organic matter or extra terrestrial biology.

Mat Kaplan: I'm glad you brought us back to the moon, Lisa. I want to go back to the first of those two NIDs, those NASA Interim Directives. The one that did talk about the moon, I read it, and it sounded like except for the poles, which need to be given greater consideration, greater protection because of those permanently shadowed areas, where we know now there's water, and those historic sites that Mike talked about that are being protected in other ways as well. It sounded like the rest of the moon is more or less, I'm exaggerating a bit, fair game under these new directives?

Lisa Pratt: That is the proposal. That is out there now for the rest of the community to respond to. That will be the very first ask NASA has for the new Committee on Planetary Protection. What is the current scientific consensus on the sensitivity of the moon as a whole, and in particular, the sensitivity of the permanently shadowed regions with regard to the activities that are created by both robotic and human missions to the moon? It's been discussed. COSPAR and ISA had been serving the lunar experts in Europe. The Academy will dig in deep and talk to the US Scientific Community. COSPAR is the place where the international community can drive their opinions back into the system. if the NID has it right, I think it strikes a balance. We've we've been to the moon, or we've been down on the surface, both soft landed and crashed quite a number of times.

Lisa Pratt: We have a wonderful reservoir of lunar samples here at the Johnson Space Center that are curated and available for the whole world to seek materials for scientific research. I think we know enough about the moon to let a wide range of activities occur over more than 95% of the surface, and then we lay out those two small areas that encircle both the PSRs and the areas where the neutron instruments show additional water outside the PSRs. We need to get in there very carefully. We need to know what's there. We need to know what kind of a record it might provide. If those are layered deposits that accumulate from the top, then we could have archives of billions of years of volatile addition to the earth moon system, and we need to know before we do crazy stuff there. This is a step in that direction. It's a one year interim directive. An interim directive asks for input from the broader community.

Mat Kaplan: These expire, currently, expire in July of 2021, I think I saw. Alan, do you have any other comments about the first of these two NIDs?

Alan Stern: I do. In fact, both of those NIDs came directly out of findings and recommendations that the PPIRB made to NASA. I think all of us on the review board were very happy to see the policy implementation in terms of these interim directives. Frankly, I look forward to this new panel that's just been constituted that Lisa spoke to, taking a close look with new expertise and new eyes, and those interim directives evolving into a more permanent regime. Because one of the things that we felt very strongly about on PPIRB is that planetary protection should not be an impediment to the exploration and development of our solar system. That we should take more of a scalpel type approach than a bludgeon, and that, where we can, the moon is a great example, we should relax planetary protection protocols.

Alan Stern: So, we took the approach that the moon is not just a point source, it's a very large body. We have sent dozens of missions there. We have literally a wide variety of samples from a wide variety of places. Remember, they're not just from Apollo sites and Soviet robotic lander sample-return missions. Lunar meteorites that come from literally hundreds of other places on the surface of the moon. We know that the moon is both living in a sterilizing environment, and none of the samples that have come to the earth naturally, or by human return have shown any biological potential. We said very specifically that we should protect those regions of high scientific interest, like the permanently shadowed regions, but the vast majority of the moon, as Lisa was describing, we can relax those concerns and help unleash this new era of 21st century exploration of the agency, and for that matter, our international partners have been in agreement with that. I think it's an important step forward.

Lisa Pratt: I want to really thank Alan and the IRB. They took some bold steps, and of course, the initial reaction of an agency when they constitute an independent review board, that is truly independent in the way this one was, and pulled in representatives very clearly from the commercial and private stakeholders, it'd get a little territorial. Don't tell us what we should be doing, but they did just that. Frankly, they created some momentum towards change. Then my goal was a fresh voice inside the agency. I think we're in a very good place. If there's really a strong rebound in the other direction, we'll hear it, we haven't heard it yet. Trust me, we're listening. We're listening for a response and we're looking forward to hearing what comes out of the next COSPAR activities, then we'll see where we are.

Mat Kaplan: This is all very encouraging for those of us who want to see exploration across the solar system moving ahead as expeditiously as possible. We only have a little bit more than five minutes left in this session. I want to get back to some of the questions that are coming in from some of the many people who have joined us today. Some of these we've touched on to a great deal. I want to get to one though from [Tapa Sweeney 00:51:47] Sharma, who I believe is one of Janet [inaudible 00:51:50] young proteges, who's participating in the summit from India. Tapa Sweeney says, what will be the material of the storage container that will carry the samples back to earth? Why was it selected? I think, Lisa, we'll go to you. Talk about those marvelous tubes that Perseverance is carrying to the red planet.

Lisa Pratt: Yeah, there was tremendous effort put into thinking about material properties, both the material as its strength, its durability, as well as its minimal contamination of the science for the types of things we wish to learn from the sample. It's a titanium material, and then it is coded, is passivated with a titanium oxide, and that's largely to control the temperature of the tubes, is to create a light colored exterior, but again, a lot of time and effort and a number of working groups participated in discussions about what that material might be. We are still in the process of working on the seals and materials for those additional layers of containment. The tube is containment one, the oz, which the samples are placed into on the surface of Mars and then launched into Martian orbit. That's another material with a specific type of seal.

Lisa Pratt: Then there is, once the oz is swallowed by the return orbiting vehicle, the European vehicle, there will be a high temperature braised seal that will not only create some sterilization because of the high temperature, but it will create a very, very fine torturous path that will act as a nanometer scale, filter for anything getting in or out. Then there's an outer layer, so excellent question, but the material that will be intimately in contact with the samples has been treated at very high temperature to remove any organic contaminants, then it is a very inert material in terms of interaction with the samples. Even if the samples should contain a hydrated mineral, if there's any possibility for acquiesced chemistry occurring outside the solid state in the sample tubes.

Mat Kaplan: Here's a question from Lisa Mae. Very interesting, takes us forward to when those samples have been returned. Can you comment on the allocation of return-samples for hazard analysis versus science investigations? Do we have to prove samples are safe before we can address other science objectives? All of that should be in the future tense, of course.

Lisa Pratt: Sure. I can jump in on that very quickly, although Mike might certainly have something to say about this. I think we all realize that backward planetary protection and the determination of the safety of the samples for release from a high containment biologically secure facility is a process that has to be developed between now and when we get ready to go bring the samples back. NASA won't be the only agency that has an opinion about what happens with those samples once they're back here on earth. I don't think we have an answer yet. I think lots of conversations, lots of interagency considerations have to take plates, not to mention the fact that this is a joint NASA, ISA sample-return campaign, so there will be players on the European side as well, who will want to have a part in the decisions about how we investigate and who ultimately gives the checkered flag. They're safe to be studied outside BSL-4 level security and containment.

Mat Kaplan: Only got two comments there. One is I sleep very well at night knowing that Lisa's there protecting our nation and our planet, so thank goodness, and thank you, Lisa. Second, you mentioned that MSR, Mars sample-return is a NASA-ISA activity. I think that's fantastic and so important because the processes that we develop are then inherently international. The hope that, even for the many nations that aren't directly participating is that we establish norms of behavior that are adopted by COSPAR and elsewhere to again, protect the entire globe.

Lisa Pratt: As we've mentioned before, if we think decisions about the safety of robotically returned samples is complicated, scale that up by orders of magnitude for deciding whether or not a returning astronaut is safe for boots on the ground back at earth.

Mat Kaplan: Alan, I'm going to turn to you, because I'm sure that you have lots of colleagues who cannot wait to get their hands, or at least their glove boxed hands on those samples when they make it back here to the laboratories available to us on earth.

Alan Stern: That's absolutely the case, and the sample-return community is fortunately getting a chance to practice with samples that we never had before, like those coming back from OSIRIS-REx being collected later this year to come back to the earth from a year of asteroid. This is going to be so powerful for the field of planetary science to be able to apply all the modern analytical techniques to do the chemistry, the isotopic chemistry, the age dating, to understand the mineralogy of Mars and added a set of documented samples from known places along the rover. Sure, is going to just propel the field of planetary science forward by light years to use a metaphor. Remember, everything we're talking about is about first sample-return for Mars, from the moon, and from asteroids, and eventually, from places like series, and hopefully Venus and Mercury. Many of their locales across the solar system, we're going to be bringing samples back to advance our knowledge. This is just the beginning. It's so exciting to see it underway, and to see it handled so responsibly from planetary protection standpoint. That's what excites me.

Mat Kaplan: Mike, with just a few seconds left, any closing thoughts?

Mike Gold: Just that Alan, I think what Lisa and I are saying is that the robotics come first, so thank you for setting us up for that human mission to Pluto. We're looking forward to that.

Mat Kaplan: Well, I'll settle for an orbiter. How's that, Alan? Lisa, we'll give you the last word.

Lisa Pratt: No, just an absolute pleasure to be here with Mike and Alan and Mat to have you moderating. It's an extraordinary period of time right now. We are stepping away and we are transforming the future of humans.

Mat Kaplan: Well said, all of you. Thank you so much for being part of this planetary protection session. Our guests have been Lisa Pratt, Alan Stern, and Mike Gold.

Mat Kaplan: You have also been our honored guests for this planetary protection panel discussion at the virtual Humans to Mars Summit. There were scores of panel speakers and special events this year, and you can watch it all at exploremars.org. We'll have a link on this week's show page at planetary.org/radio. I am deeply grateful to everyone at Explore Mars. I hope to see you in person next year, folks. Bruce is next.

Mat Kaplan: Time again for What's Up on Planetary Radio. Bruce Betts is the chief scientist of The Planetary Society. He is back with us to tell us about the night sky. I'm going to tell you about my night sky. That very night that I told you I had not yet seen Mars, it was clear, Mars was rising, and it seemed to me a little earlier, and I got off the telescope. Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and the moon all in one night, that's a good night for me.

Bruce Betts: That's a great night. Good job.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you. Yeah, they were all gorgeous.

Bruce Betts: Cool. Well, everyone can see all those things. Well, the moon depends on when you look in the next week, but the others are a sure thing. You can check out Jupiter and Saturn in the early evening west, Jupiter being brighter, Saturn being yellowish to its left, but the real crown jewel that you don't want to miss is Mars, because it was at its closest approach to earth on October 6th. It is in opposition on October 13th, the opposite side of the earth from the sun. Those two dates, interestingly, are different, closest approach and opposition. I've mentioned it before, so I can't cheat and use it as a random space fact, but I will mention, if the orbits were circular, those dates would be the same. It's the elliptical nature of the orbits that make it work out such that you can be on the opposite side of the earth from the sun and not be the closest approach date, but it's always close. It's always within days or within a couple of weeks. In the pre-dawn, Venus is calling.

Mat Kaplan: Don't keep her waiting.

Bruce Betts: I can't reach the phone right now, I'm busy. Take a message. All right. Venus is in the pre-dawn east looking super bright, but again, Mars, Mars and Mars. We'll come back to Mars, oddly enough. Onto this week in space history, it was 1968 that Apollo 7 was launched, and 40 years ago, 1980, the very large array was dedicated in New Mexico doing great radio astronomy ever since.

Mat Kaplan: That was one of the greatest moments I've ever had doing this job. There've been a lot. After interviewing the people running the VLA, I went out and walked among those big dishes, and it was well past twilight. There was just a little bit of light left in the sky, beautiful sky. I did get asked what the hell I was doing by a security guard, but that gave me permission to go out and walk around. Anyway, he left me alone, and I just was out there. If I'd had headphones, I could have been just like Jodie Foster.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, because that was totally realistic.

Mat Kaplan: Right.

Bruce Betts: I've always thought of you as just like Jodie Foster, just as a side note.

Mat Kaplan: Most people do.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. Move quickly on to random space fact. I will talk more about Mars because, although Mars was closer to us at its 2018 opposition, this week, this week at about 62 million kilometers away, Mars is the closest and thus brightest it will be until 2035. Every couple of years, every 26 months, it'll come around and brighten, but the way the elliptical orbits work, not until 2035, will it be this bright again. It's maximum brightness right now is around minus 2.6 magnitudes, and that makes it brighter than Jupiter, which is a rare, rare occurrence.

Mat Kaplan: I'm going to put that on the calendar so that I'll remember in 15 years to take the telescope out again, right after we do What's Up.

Bruce Betts: I can get you that exact date if you want for your calendar, but maybe after this job.

Mat Kaplan: Okay.

Bruce Betts: We move on to the trivia contest. I asked you, what is the largest rock returned from the moon by Apollo astronauts? I said I will accept either the rocks as official designation and/or its nickname. How'd we do?

Mat Kaplan: We got both from most of our entrants this week, and there were a lot of them. I think people enjoyed this one. Let me also add that many, many of you who took the time to write down to the contest, or separately wrote, Emily is grateful for all of your wonderful messages that came in as she starts this new phase of her professional life. I am passing all of those along to her, so thank you very much. Here's an answer from Dave Fairchild, our poet Laureate in Kansas, lunar samples brought to earth were fairly different sized, nothing bigger than your fist is what was really prized. But when they found Big Muley shocked anorthosites, we're told, they brought it back and found that it's about 4 billion old.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, I like it. I like it. Big Muley.

Mat Kaplan: Here is the answer that won this one for a long time listener, first time winner, [Aaron 01:04:22] Gordon in Florida. Congratulations. Aaron, lunar samples 61016, or better known as Big Muley was found on the Apollo 16 mission, named after Bill Muehlberger, the Apollo 16 field geology team leader and principal investigator, I guess for geology, for both Apollo 16 and 17. He added special farewell to Emily Lakdawalla, may she continued to reach for the stars. Godspeed, Emily. Special shout out goes to the space community and fellow labbies at FamiLAB Hackerspace in Orlando, Florida, which Aaron lives very close to. I've seen some pictures of FamiLAB. Looks like a cool place to hang out.

Bruce Betts: As cool as the VLA at sunset?

Mat Kaplan: No, no, but I bet they have a decent excuse for a maker lab there as well. That official name, that sample number, we had a bunch of people write about that. Mark Dunning, Cody Rockswell, both in Florida as well. Florida made out big time this week. Noted the Big Mulley sample number, here it is again, 61016, is a palindrome. As Mark said, ooh, a palindromic number, cool, but not as cool as Mat and Bruce. Is that pandering? I'm pandering, aren't I?

Bruce Betts: We encourage pandering as you know.

Mat Kaplan: Pandering. To bad it's a palindrome. Mel Powell, who misses Emily, but already follows her on Twitter, of course, she says, I'm a map nerd, so I looked up the location of US Postal Zip code 61016 ... wait, there's more. In a small city called Cherry Valley, Illinois, which seems to be a suburb of, you can't make this stuff up, Rockford.

Bruce Betts: Wow. That is wonderfully random space trivia.

Mat Kaplan: Ian Gilroy, who said, "Boy, it was a pretty big rock. It's lucky that they were on the moon." He says, "I'd rather be doing the loading than the unloading." Finally, another poem from [Jean Lewin 01:06:22] up in Washington. Charlie Duke complained about this plum crater sample, told rocks about the size of his fist were going to be ample. Once spotted by the LRV, Muehlberger ignored preset restriction, and this football size specimen started out 16's collection. Returned to earth by an Apollo team, something we know is truly the largest sample rock affectionately called Big Mulley. Two great poetry previews because next week is our poetry spectacular on this show. All this wonderful stuff from the new collection beyond or sedge, and some great celebrity poem readers. Don't miss it next week. I didn't yet say what our winner Aaron Gordon won.

Mat Kaplan: You would not forgive me if I don't, Space Exploration for Kids: A Junior Scientist's Guide. Did I miss something here? Because it's all garbled on my seat. Space Exploration for Kids: A Junior Scientist's Guide by Bruce Betts. That is the full title, isn't it?

Bruce Betts: Nope.

Mat Kaplan: Okay. What is it?

Bruce Betts: Space Exploration for Kids: A Junior Scientist's Guide to Astronauts, Rockets and Life in Zero Gravity.

Mat Kaplan: I don't how this got so garbled. It's out, right? It's available for all the usual places.

Bruce Betts: It is indeed.

Mat Kaplan: This time we're going to go back to a rubber asteroid, because a whole bunch of you have been asking for them. I guess, once in awhile is simply not enough. Once is not enough. Go ahead and take us into a new contest.

Bruce Betts: We will celebrate the 40th anniversary of the very large array in New Mexico by asking you how many 25 meter antennas are at the very large array. There's actually, it turns out like every trivia question I come up with, it's never a simple answer. There are a couple answers. I'll take either. Go to planetary.org/radiocontest. But the formal question is how many 25 meter antennas are at the very large array?

Mat Kaplan: My answer would be a lot, and they creep around the desert.

Bruce Betts: It will be more specific. I'm going to need a number.

Mat Kaplan: You have until the 14th. That'd be October 14th at 8:00 AM Pacific Time to get us this one, and win yourself that rubber asteroid, specifically a Planetary Society kick asteroid, rubber asteroid. With that, I believe we're done.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody. Go out there, look up in the night sky and think about, if Mat were a military pilot, what would his call sign be? Thank you, and goodnight.

Mat Kaplan: Hey, if you want to throw that into your entry, well, they would stencil on the side of my F-22, go ahead. Give us that. I suspect we'll get a few votes for big mouth. I think that'd be a good one. I wonder if anybody's ever gone do that. Big mouth, put it on the helmet too. He's Bruce Betts, the chief scientist of The Planetary Society, and he joins us every week here for What's Up.

Bruce Betts: Big Bill, over and out.

Mat Kaplan: Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California, and is made possible by its very protective members. You can protect your interest in space exploration by joining us at planetary.org/membership. Mark Hilverda is our associate producer, Josh Doyle composed our theme, which is arranged and performed by Peter Schlosser. Ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth