Planetary Radio • Oct 02, 2020

Space Policy Edition: Divining Biden's Space Policy with Jeff Foust

On This Episode

Jeff Foust

Senior Staff Writer, Space News

Casey Dreier

Chief of Space Policy for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

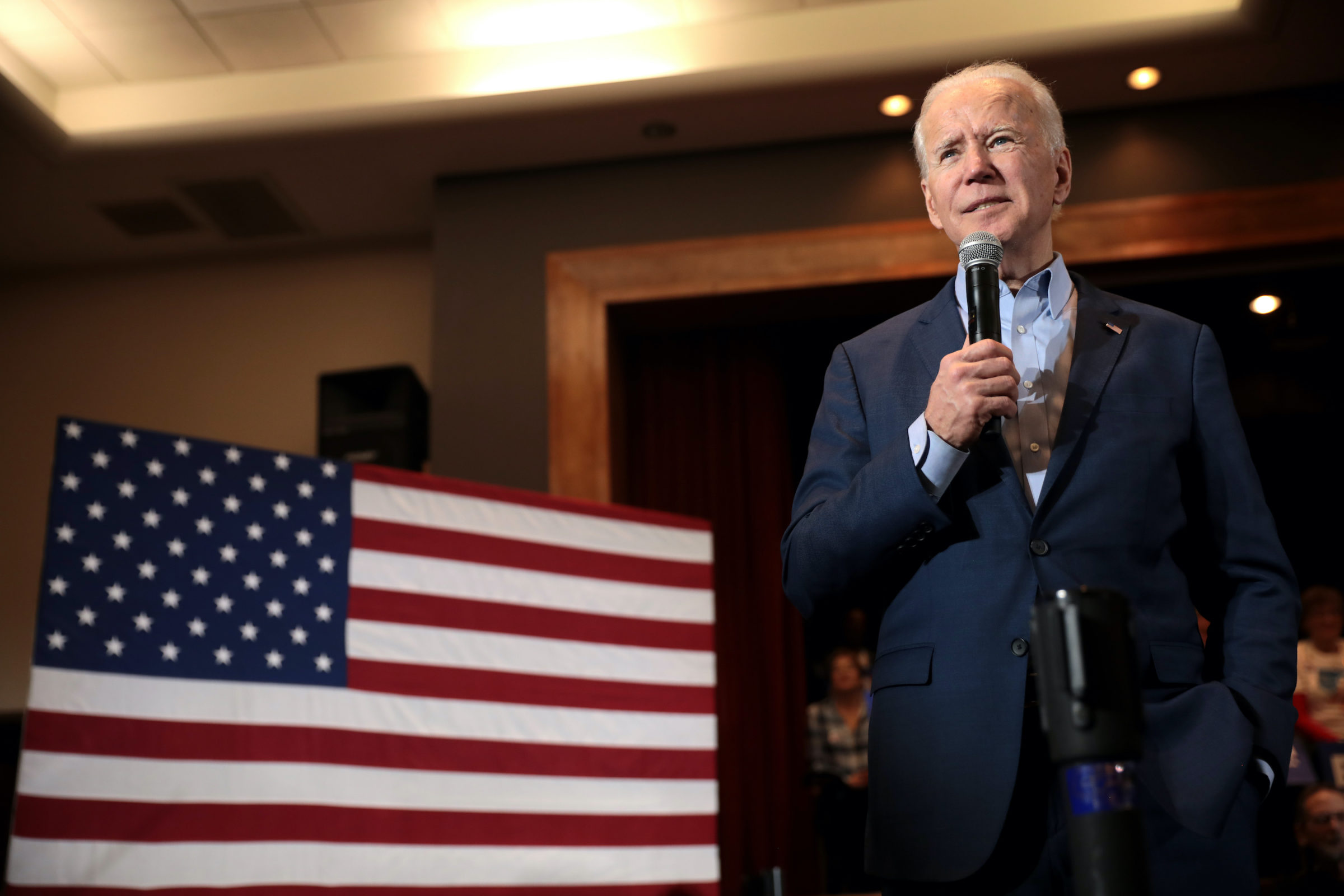

A month before the U.S. election Joe Biden's campaign has yet to state its goals for space and NASA. We asked Jeff Foust, one of the best space reporters in the business, to help us piece together a working model of a potential Biden Administration space policy. We comb through the available evidence, combining insights from Biden's history in the Senate, his 8 years as vice president, and current activities in the Democratic House of Representatives and party platform to create a prediction of what might be the same, and what might differ from the Trump Administration's approach to NASA.

The Planetary Society, as a nonprofit organization, cannot endorse individuals for elected office. We offer this episode as a service to our members as part of our commitment to providing non-partisan insight and analysis for space politics and major issues.

And if you live in the U.S., don't forget to vote by November 3!

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: Welcome to the October 2020 Space Policy Edition of Planetary Radio. We are so glad to have you back. I'm Mat Kaplan, the host of Planetary Radio. Doesn't seem like it's been long does it, Casey? Because it hasn't. After delaying the last one, we're back in fairly short order.

Casey Dreier: How lucky that we just get to talk more soon than we would have otherwise.

Mat Kaplan: And that we get to have this conversation, as the voting is already underway in the United States to pick the next president and everything else that's happening at the federal level. Welcome Casey.

Casey Dreier: Thanks, Matt. As always, I'm happy to be on the show with you.

Mat Kaplan: That, of course, is Casey Dreier, our senior Space Policy Advisor at the Planetary Society and our chief advocate. We will be meeting his guests. It is perfectly timed. Casey, you have invited Jeff Foust, who is one of my heroes in our business.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. Jeff Foust is a prolific, I think it's fair to say writer on SpaceNews literally and it for the magazine, SpaceNews, and also covered space politics for a long time on his old website, spacepolitics.com. He writes the FIRST UP newsletter for SpaceNews, that's a daily summary of all the things happening in space. And I asked him on the show to help me kind of divine and suss out Joe Biden's Space Policy, should he be elected for the next four years? Just to kind of compile all the various bits and pieces of information we have, because the campaign has at the time of this recording, not put out a formal statement on what its Space Policy will be. So this is an attempt to try to combine what we know and lay that out for our listeners in advance of the election.

Mat Kaplan: It is another terrific conversation, Casey. Of course, we've already got it in the can as we say and so I got to monitor it as you were talking with Jeff. And as I've said before on the show, I start every workday with FIRST UP that Jeff Foust puts together for all of us in this business and you can subscribe too. It's put up by SpaceNews and I highly recommend it.

Mat Kaplan: Let us also recommend to those of you who are not yet members of the Planetary Society, come on, you knew this was coming, that you go to planetary.org/membership, check us out, look at the different levels at which you can come in, look at all the things we will do for you as a member. And that primary among those is representing you in Washington, DC and elsewhere around the world and making Space the place for all of us through tools like this, the Space Policy Edition and Planetary Radio and our website and Facebook and everything else that we are up to. Please take a look and join this merry band at planetary.org/membership.

Casey Dreier: Mat, you should also say that we are in the midst of a membership drive at the Planetary Society.

Mat Kaplan: We sure are. Trying to find 400 new members of the society, that's nothing. You can become one of those. I think we ought to be going for 4,000 new members and we are, but in this current drive-

Casey Dreier: That's true Mat.

Mat Kaplan: Giant leaps, Casey.

Casey Dreier: Yes, there you go.

Mat Kaplan: Why not help us reach this current goal? This is a very short campaign. I'm hoping, I'm certainly expecting that we will make this goal of 400. Help us exceed the goal. Help us get way beyond and really demonstrate that you are one of those who believes in what the Planetary Society is doing in the best way that you can do that, which is by becoming one of us becoming part of our society.

Mat Kaplan: Casey, let's go back to, well, a little bit of what you'll be talking with Jeff today, actually a lot of that. But it also brought back to me your great conversation with Scott Pace, the executive secretary of the National Space Council, that was this September Space Policy Edition of course. You've continued to write about this. You've written about the positions of the candidates and I think this is something you wanted to say a little bit more about.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. Well, obviously this election is a pretty intense time for the country and talking a little bit about why we're really focusing today on Joe Biden's Space Policy as his campaign. There's two reasons for that. One, I think the space policy of the Trump administration is quite clear. We've been living through it for the last four years and really kind of succinctly summarized by what Scott Pace discussed in our last episode.

Casey Dreier: So if you really want to dive down into the details of that, I recommend listening to that episode, that interview with Scott Pace. And to probably just summarize it, they're taking again, from focusing on the civil space side here, a whole of government approach to integrating space. It's a relatively high priority within the administration. It's a personal interest of Vice President Mike Pence. And you see that being reflected in the administration, that there is an awareness up and down the administration, whether it's in NASA or outside of NASA, that space is an important issue.

Casey Dreier: You've seen a reasonable request go out this year for budget increases to NASA, about 12% to support the Artemis program that came after a few years of flat and small cuts being proposed to NASA, but relatively, again, a high priority for the administration. High priority in terms of human spaceflight, a very symbolic approach to returning humans to the moon. And you're seeing that, again, kind of reflected in the rhetoric of President Trump and the administration more broadly.

Casey Dreier: And so I think, again, we kind of know what the President's Space Policy would be going forward. They have the 2024 goal for returning humans to the moon, which again, would be the last year of a second Trump term if he wins re-election.

Casey Dreier: Today, I really wanted to look at kind of the flip side of that. Joe Biden, who is the Democratic nominee hasn't really said much about space. There's no formal campaign document about space and I'll emphasize here that we did contact the Biden Campaign Press Office asking for details and someone to actually come on the show to discuss this with us and we never heard back from them.

Casey Dreier: As a service to the community and to our listeners and to our members here at the Planetary Society, I thought it would be an important and useful thing to do to try to explore what we can piece together, to really dive into can we find public statements about Biden himself and what he said about NASA over the years, to look at previous behavior under the Obama administration when he was Vice President, and to look at current activities done by the Democratic leaders of the House of Representatives for space. And again, try to compile all these together and say here's what we can maybe predict based on this but again, acknowledging that there is no clear Space Policy being set forward, so that these are in a sense, broad ideas and I'd say informed speculation, perhaps of a potential Biden administration Space Policy.

Mat Kaplan: We get questions now and then about why with all of our activity in DC, the Planetary Society doesn't endorse candidates. And I think that's explained by our status as a nonprofit. But even more to it than that.

Casey Dreier: There are two answers to this. The first is just a legal one, where the Planetary Society is what's called a 501(c)(3) nonprofit. And that's a line in the US tax code that says for our nonprofit status to be, if you want to donate to us, people can deduct donations to us as a tax write off.

Casey Dreier: In order to be that status, we cannot take active positions in electoral politics. The key is electoral. So we can't endorse candidates, we can't help certain candidates get elected over others and there's a legal reason we do that. We can talk about issues. Obviously, we do talk about issues. But in terms of candidates themselves, we're not allowed to and so we cannot endorse any president. And then the second part of that answer is to our DNA, I'd say as an organization, we talk about space being for everybody.

Casey Dreier: Electoral politics has a way of being somewhat divisive, particularly right now. But also, we're committed as an organization to working with whoever is in power. We do not take a position of preferring one party or one candidate over another because we are committed to making good progress and sharing and expanding our space exploration, space science endeavors with them. We want to be an open and inclusive organization. And that includes politically.

Casey Dreier: Even if we could endorse a candidate, I would predict that we would not in order to preserve our, again, this open door of saying... Space is about what unites us, right. No matter your political persuasion, if you think space is a wonderful, beautiful, exciting thing, if you're moved by the concept of exploring the unknown, if you want to search and seek out what is out there, you have a place here at the Planetary Society. And so that's again, one of the reasons we don't dive into politics.

Casey Dreier: And that's again why I want to just be careful when we are talking about this kind of episode, that this is not an endorsement of either candidate, what we're doing here. This is purely trying to provide information from what we know from as dispassionate position as we're capable of being. That's why I invited Jeff Foust onto the show today, because Jeff, I think is...

Casey Dreier: One of his superpowers in addition to being incredibly prolific is that he has a very wonderful journalistic neutrality that he brings with him, a very clear analytical mind without injecting his own passions into it. I thought that would be a useful neutral perspective to bring to this. He's not an advocate for the Biden campaign, he's not an advocate for the Trump campaign, he's a journalist for SpaceNews who's been in the business for a long time.

Mat Kaplan: I have seen how hard we and our colleagues at the society work at maintaining that position of neutrality for all the reasons that you've talked about. I think it's extremely important. And I guess, I could take some pride in that. Every now and then I'm either called a mouthpiece for the left or an apologist for the right.

Mat Kaplan: And if I get those in roughly equal number I figure well, I guess I'm probably doing okay with the radio show. I am very impressed by the society's performance. I'm biased, perhaps. But we're going to continue to strive for exactly that because we do want this to be the place where we can all come together. Space is the place as the boss says.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, couldn't agree more, Mat. Again, this is our attempt to suss out and define and give you in a sense the tools for putting together what we know about the Biden campaign and a potential Biden administration. And that is information for you as you go forward in the next month. But maybe I'll just add on top of that, space should not be your single issue vote in general.

Casey Dreier: Citizens should have a broad number of things you use to evaluate who you vote for. I'm a space advocate. I do it professionally and I'm not a single issue voter for space. I take a broad number of inputs. This is an input into your process for choosing how to vote. And again, we hope it's a useful service that we provide for you.

Mat Kaplan: All right. Here is Casey's terrific conversation with Jeff Foust of SpaceNews, creator of the FIRST UP column, newsletter, I should say. We will be back at the other end of this conversation to wrap up.

Casey Dreier: Jeff, thanks, again for being here today on the Space Policy Edition.

Jeff Foust: Thanks for the invitation Casey. It's great to be on.

Casey Dreier: We just had a presidential debate last night. By the time that we're recording this, maybe people notice that Space did not come up as one of the prime topics that Chris Wallace asked both Biden and Trump. This is something that we I think, deal with every four years or so about Space Policy and presidential campaigns. I want to take a big picture of how we approach this both as space advocates in mind and journalists in your end. Is this something that we're used to seeing that space policy is generally in the background here?

Jeff Foust: Yeah, 2020 is an outlier for many reasons. But the lack of attention to Space Policy is not one of them. Space is a very low-level issue traditionally for presidential campaigns among both Republicans and Democrats. There are simply just so many bigger issues from the economy, to foreign policy to social issues to this year, the pandemic that affect far more people than Space exploration or NASA in general too. It's just not something that attracts a lot of votes, it doesn't sway that many voters. So it just simply doesn't get a lot of attention.

Casey Dreier: I think that's always good to remember. It's not a visceral issue, I think, for a lot of people and it doesn't change our day to day life or I'd say just in general voter's day to day life much. And so it tends to be treated as such. But I was kind of wondering if the Biden campaign in particular is providing less than even usual or maybe we'll just say that less, kind of judgmentally. Is there a difference in how you're seeing the two campaigns talk about space, this time, compared to your experience with past campaigns?

Jeff Foust: I remember going back to the Democratic primary season way back last year when there were 20 or more candidates running. Around this time last year, I tried to reach out to as many of the candidates as I could including the Biden campaign, to ask them just a few very basic Space Policy issues, including what they thought about NASA's plans to return to the moon. You probably won't be surprised that none of the campaigns actually provided any sort of substantial policy on it.

Jeff Foust: In fact, very few even provided any sort of response at all, other than the occasional PR person saying, "I don't know. I'll look into it." And then not hearing from that campaign again before that candidate dropped out. It was a very low-level issue and this was back before the pandemic and certainly now with the pandemic occupying so much of our attention regarding the response to it and the economic fallout from it, space is even a much lower priority issue.

Jeff Foust: The Trump campaign can point to what the Trump administration has done in the last four years on space. If they want to, they can point to a lot of the space policies they've done. They can bring up Space Force, of course, as the President often does on the campaign trail. But the Biden campaign just doesn't really talk much about space at all, because again, when Biden is out giving campaign speeches or talking with people, there are a lot of other bigger issues on people's minds than whether we're going to return to the moon by 2024 or not.

Casey Dreier: We talked a little about the primaries, which kind of makes sense to me. I think in the time that I've been observing space politics and policy, it makes sense that during the primary stage, there's not a lot of highly developed policy for these broader topics beyond the really big issues that the candidates are kind of identifying themselves with by choice. But by the time you get to, maybe the month before the election, generally, I've seen in places like SpaceNews, that there is some at least written statement from campaigns outlying just some broad approaches to space.

Casey Dreier: I usually associate that with the campaign's themselves kind of staffing up, anticipating a potential transition. But I haven't seen that yet. Are you anticipating any further clarification from the Biden campaign or is there any other kind of information that you've been able to hear from that campaign representatives themselves on any kind of issues of space?

Jeff Foust: We certainly haven't heard anything. I would certainly love to hear more from the Biden campaign about what they would do on space. They just really haven't said a lot. And I think that just gets back to the overwhelming crush of other issues taking place right now and the focus that are on those issues. We look back to May, around the time of the Demo-2 commercial crew launch.

Jeff Foust: The Biden campaign actually did arrange a brief media event with a couple of their campaign surrogates, Bill Nelson, the former senator from Florida and Charlie Bolden, the former NASA Administrator. They were really just talking about commercial crew and mentioning Biden when he was vice president playing a role behind the scenes to try and win congressional support for the program back in the 2010 time period when the Obama administration was trying to make its own stamp on Space Policy.

Jeff Foust: They were a little reticent though to comment much to what a Biden administration would do when it comes to space. And after the successful Demo-2 launch, the Biden campaign actually put out a statement, expressing their congratulations to NASA for the successful launch, noting that the commercial crew program dated back to the Obama administration or the Obama-Biden administration, as they would put it, and their support for that that program. But there really hasn't been too much then.

Jeff Foust: The democratic party platform that came out around the time of the virtual democratic party convention this summer does include one paragraph about Space Policy, specifically NASA. It suggests really a sort of continuity of policy in that it's not calling for any major changes. It expresses support for what it terms NASA's work to return Americans to the moon and go beyond to Mars. It doesn't explicitly support a 2024 human return to the moon that the Trump administration is seeking. But it does support human space exploration beyond Earth orbit.

Jeff Foust: It specifically calls out support for Earth observation missions, which is something the Trump administration has tried to cut unsuccessfully in its budget proposal over its first term. And it also calls for continuing the ISS, which is something that both Republicans and Democrats in Congress have long expressed support for.

Jeff Foust: Just by reading that one paragraph of a roughly 90-page document, you get a little bit of an indication of what a Biden administration might do in space. And that is the first order pretty much stay the course with maybe taking the foot off the gas when it comes towards returning humans to the moon but not swerving off into a completely different direction.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, I thought that was interesting seeing this. I think the democratic party platform and we'll include a link to this in the show notes for our listeners is, to my knowledge, the most I think explicit statement on Space Policy, not just of the campaign, but just in a democratic party platform in recent years. It seems like a beefier statement, even though again, it's a platform statements was kind of broad. But that did give some context.

Casey Dreier: I would say again, to emphasize this in terms of how we as observers or fans of Space Policy are trying to stitch together what little information we have. We're kind of trying to connect these dots, right. I thought it was at least helpful last night during the debates that Biden clarified. He stated and I have this quote here. It says, "The platform of the Democratic Party is what I approved of." He clarified like, "This is something that I personally signed off on." And then implies then a certain level of you could tie it maybe more clearly to what a potential administration would then look at.

Jeff Foust: Yeah, that's correct. He's really taking ownership of this document and saying, this policy platform, this party platform is his blueprint for what he would try to do in broad strokes in a Biden administration. You can look at that and then look at that one paragraph on NASA and conclude that he would not immediately make a lot of changes to what NASA is doing.

Jeff Foust: And to some degree, that makes perfect sense. If he takes office in January, there going to be a lot of other things to deal with. He's not going to have a lot of bandwidth to deal with NASA and making a lot of changes. As long as he doesn't see anything that needs to be seriously changed at the space agency, I would expect a lot of NASA programs would continue pretty much as they are now but perhaps at some cases, like a human return to the moon at a slower speed.

Casey Dreier: Right. Let's talk about kind of how you as a journalist and I would say just me too as a policy, analytical perspective, how we try to build this out. How are we trying to integrate this information that we have? Because the fundamental problem is we don't have a clear statement from the Biden campaign. For our listeners, if we want to encourage them, how can they themselves try to use these tools to analyze what a potential policy would look like? Where do you look?

Casey Dreier: You've looked here, you've stated for a democratic party platform, you referenced kind of the history of Joe Biden in the Obama administration. How else do you try to integrate limited data to create some kind of coherent analysis for how to interpret this?

Jeff Foust: You look at what's available publicly. And besides his time in the White House, Biden does have a Space Policy track record. He spent decades in the Senate but he wasn't involved with any of the major committees that deal with either authorizing or appropriating funds for NASA.

Jeff Foust: Delaware is not a space state in the same way that Florida or Texas is. It's not really a front of mind issue for him. So he's not really involved in Space Policy during his time in the Senate. You look at what we do have available.

Jeff Foust: You sort of put feelers out behind the scenes to people who do know what's going on, who may have contacts with the campaign. They may not know much more than what's publicly available, but you at least sort of try and open those additional avenues of discussion and insight into what the campaign is thinking about and what they might be thinking about looking ahead to an administration.

Casey Dreier: I was personally looking through the Senate record. And something that's actually kind of a frustration, which I think is on purpose function of the Senate is that a lot of relatively non-controversial legislation gets passed by either voice vote or what's called unanimous consent. And when they do that, there's not what's called a roll call vote that actually puts a yay or nay vote to a particular senator.

Casey Dreier: Going back the last 25 years or so 30 years of NASA authorization votes, there's not a ton of NASA legislation that's really focused on NASA. There's so little actual roll call votes. You can't tie it one way or another to Joe Biden or really any other particular senator. You can say that he unanimously consented, he didn't descend off of many NASA authorizations. But as you point out, just his role in the senate didn't naturally intersect with space issues.

Casey Dreier: Maybe to really state what a basic takeaway is, maybe Space is in a sense, kind of an idiosyncratic interest of an individual politician in that case, right. Delaware is not a space state in a broad sense, like Texas or Florida, then to have an opinion on NASA while serving as the representative of that state, you would actually have to have a personal interest, almost.

Casey Dreier: Maybe the lesson that we can learn from this is that, despite the kind of his lack of information says that there's maybe not a strong personal interest in space, but that doesn't necessarily drive policy outcomes. That just means he hasn't gone out of his way to engage on the issue.

Jeff Foust: Yeah, I think that's a pretty fair assessment. I think you've seen over the years in Congress, the real champions for the Space Agency or specific programs at the Space Agency have been individual members that either have a stake because of what's going on in their state or district or simply because for one reason or another, they really like it. Like John Culberson, the former congressman from Texas, was a big supporter of the Europa Clipper Mission and ensured that mission got funding well beyond what NASA and the administration would ask for over the years, simply because he thought it was a really interesting and important mission to find out whether Europa might be potentially habitable.

Jeff Foust: That may be sort of an extreme example. But I think that's a point that for an issue like space, which also isn't particularly partisan. You see a lot of working across the aisle between Democrats and Republicans on space issues traditionally. The divisions tend to be more parochial than partisan over the years. You don't see that sort of obvious lineup of democratic versus Republican in a lot of aspects of that.

Casey Dreier: And I wonder if that's actually why you don't see space as an issue in a presidential campaign as much. It reflects in a sense that more parochial non-ideological, in a sense, almost by definition, if it was a major issue, if there was a big Trump policy and a big Biden policy, that would almost imply that there's an ideological component that would then be defining it. Perhaps we should be grateful that there's no big space issues being discussed at the campaign level in a presidential campaign.

Jeff Foust: Certainly it voids the sort of ideological partisan tug of war. But it also sort of ensures space keeps a lower profile because it is not something that's going to drive one particular party over another on a particular issue and drive, say votes on an issue. It is a much lower level issue. It is something where you see a lot more cooperation, behind the scenes, particularly on Capitol Hill, on space issues.

Jeff Foust: It really comes down to, as you mentioned earlier, sort of individual interest. And we've seen that this administration, where the Vice President Mike Pence has taken a personal interest in space, and he is chaired all these meetings of the National Space Council, in fact, reconstituting the National Space Council, which has been dormant for a quarter century, pushing out a series of space policies on various issues including a human return to the moon. But you didn't see that when Biden was vice president or for that matter, when Dick Cheney was vice president in the George W. Bush administration.

Jeff Foust: It was Pence's personal interests that became a driving force for space policy in this administration. And I don't think we can expect Kamala Harris to have that same sort of interest, because she also has not been very public out there about space policy in one way or another during her limited time in the senate so far.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. Why don't we expand on that from the Senator Harris's perspective. She's from California which can be argued as a somewhat of a space state, even though the just the size, the economic footprint of California is so massive that having three NASA centers and a bunch of aerospace contractors is a relatively minor contribution to it. What do we know about Kamala Harris's background in engagement with space?

Jeff Foust: Her background in space has also been very limited. She has not been involved in a lot of the policy debates in Congress on these issues so far. And again, as you mentioned, there's a lot of things going on in space in California between the NASA centers and the space companies large and small in the state. But that tends to get dwarfed by the much bigger issues that are going on, the much bigger industry is going on.

Jeff Foust: Again, it's not something that she has shown much of a particular personal interest in. And it's not something that's really caught up in a lot of her committee activities. We'll have to wait and see if she becomes Vice President Harris, if she will take any sort of role in space policy that has from time to time in the past been something that has been a vice presidential responsibility.

Mat Kaplan: Casey and his guest, Jeff Foust of SpaceNews. We'll be back after this short break.

Jennifer Vaughn: Thanks for listening to planetary radio. Hi, I'm Jennifer Vaughn, Chief Operating Officer at the Planetary Society. Want to support this show and all the other great work we do? Help us reach our goal of 400 new members by October 6. When you become a Planetary Society member, you become part of our mission. Together we enable discoveries across the solar system and beyond.

Jennifer Vaughn: We elevate the search for life and reduce the threat of a devastating asteroid impact here on Earth. Carl Sagan co-founded this nonprofit 40 years ago for all of us who believe in exploration. Can we count on you? Please join us right now at planetary.org/membership2020. Thank you.

Casey Dreier: Before you worked at SpaceNews, you ran a number of very interesting websites. One of those was spacepolitics.com, something I used to read every day. How long did you run spacepolitics.com just briefly?

Jeff Foust: I started spacepolitics.com in 2004. I put it on hiatus when I joined SpaceNews in 2014. I ran it about 10 years, probably a little over 10 years to be exact. I've seen a lot of ups and downs in Space Policy during the Bush and Obama administrations during that decade.

Casey Dreier: I kind of chuckled when I was doing some research for this podcast. Again, looking through this history of what can we find about Biden just any statements with NASA, the most relevant pieces I found were actually archived on spacepolitics.com back in 2008. Do you remember those? This is the Biden on Space post that you had from then-

Jeff Foust: Right. Yeah. This was back when he was... He was trying to make a... He was involved with the Obama campaign back then. Yeah, it was long time ago.

Casey Dreier: And that's about the most relevant we have. But it was interesting reading through that, it was reacting at that point to the planned end of the space shuttle and the economic and particularly job impact that it would have in Florida and a number of other key states. That actually kind of raised this idea with me if this idea what we're saying earlier, this space doesn't really move many votes.

Casey Dreier: That may be true. I can see that from a national perspective. But do you think that's actually true for a state like Florida or a state like Texas? Texas isn't so much of a... Maybe it's becoming more purple-ish, but Florida is known classically as a swing state. You would think at some level by the number of jobs in the kind of the preeminence of space in Florida, that that would actually play into electoral politics at some point. Is that surprising that we don't see that in these recent cycles?

Jeff Foust: Yeah. And I think part of that is that we call Florida a space state, but most of that space activity is limited to one very small part of the state, the space coast around Cape Canaveral, [inaudible 00:31:44] county and environs. That's where the concentration of the space activities and the space employment is. And that tends to be actually... Has increasingly become a Republican area.

Jeff Foust: Even though, it's part of what's considered the I-4 corridor, which is the swing area of the swing state between the more republican Northern part of Florida and the more democratic southern part of Florida. But if you're trying to swing that corridor, you're much more likely to spend time in places like Orlando and the Tampa Bay area, which are much larger, have much greater populations, but have less involvement in space.

Jeff Foust: The idea that space can be a swing issue, I don't think is nearly as strong... I don't know if it's necessarily that strong in 2008. I think it's even less strong now simply because of the shifts in voting patterns in the state. And so the idea that some of the space community have put forward that space is this big swing issue in a big swing state, has really never come to fruition. And I think it's going to be even less true this year simply because people are going to be much more concerned about much bigger issues regarding the pandemic and the economic impacts of it, then a space program that seems to be doing pretty good at this point in which neither party is talking about making major changes one way or the other in space policy in the next four years.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, I guess we can ask Bill Nelson, how his connection to space helped him on his reelection attempt back in 2018 in Florida. Rick Scott unseated him, and Rick Scott was never a strong space advocate the way that Bill Nelson had. Hard to compete though with Bill Nelson for-

Jeff Foust: Bill Nelson is a whole other tier when it comes to the space advocacy in part because he got to go to space himself, in part because he was in Congress at the time back in the 1980s. Although, as Governor, Rick Scott did do some work to help lure space companies to Florida, especially as the Space Coast region was recovering from the 2008 recession and the end of the shuttle program. So he did play a role in that. He actually does today in the Senate, sit on the Senate Commerce Committee, the same committee that Nelson was once the top democrat on.

Casey Dreier: Again, we've kind of discussed a couple of ways of evidence that we can use to kind of create the likely predictive model, let's say or a reasonable predictive model for a possible Joe Biden administration on space policy. Where do you see the recent activity in the House of Representatives which swung back to the democrats in 2018, they released their NASA authorization bill, which had a number of changes compared to the Trump proposal for NASA, particularly with human spaceflight returning to the moon. Where do you see that legislative activity fitting into in terms of influencing a potential Biden an administration?

Jeff Foust: Well, it's interesting that early this year, that got the house version of a NASA authorization bill, which had co-sponsorship by both the top Republicans and the top Democrats on the House Science Committee. It got a lot of attention because it was taking a very different direction towards that return to the moon, which for NASA is relying on a similar public private partnership that the agency used for commercial cargo and commercial crew.

Jeff Foust: The house when it's something that was a little bit more of a traditional procurement program that would be government-led with the government owning and operating the landers. They're also looking for a lander that could launch as a single piece on the Space Launch System rather than allowing companies to come up with solutions where landers are launched in modules on commercial rockets and then assembled in lunar orbit or at the gateway for lunar missions.

Jeff Foust: That got a lot of attention in January and into February and then the pandemic hit and all that discussion really shut down. And it's notable that we haven't seen any public activity on that authorization bill since early this year. It was supposed to, at one point go before the Full House Science Committee for what they call a markup and approval and send it up to the Full House. In March, that got put on hold by the pandemic. There really hasn't been any action on that bill since then.

Jeff Foust: It's an open question whether that would have much of an influence on a Biden administration. When it comes towards reshaping a Artemis program for human return to the moon. By the time that Biden takes office, if he wins election in November, and is inaugurated in January 20th, NASA will be very close to making a decision on which of the three companies that selected for the human landing system program in April, the one team led by Blue Origin, the one led by Dynetics and then SpaceX, which one of those they want to continue into development. And part of that decision is going to depend on what sort of funding NASA gets for fiscal year 2021, if that decision is in fact, made by February and obviously, the progress that companies have made on the proposals.

Jeff Foust: It would start to get a little bit more difficult to change direction significantly in that approach. Although if you're not rushing to get back to the moon by 2024, you might be able to step back and slow down on that for a while. Certainly, we've got that House bill. But I don't necessarily see that as an obvious template for what a Biden administration would do for a human return to the moon if they take office next year.

Casey Dreier: Yeah, I've been trying to kind of compare those two things. The question is basically to what degree is the House bill a reflection of kind of a group of, again, maybe potentially idiosyncratic House Democrats who are writing it primarily versus what would fit best with a potential Biden administration. Just to kind of unify a couple of these themes that we've been discussing.

Casey Dreier: Again, let's just say should the election swing towards Biden and he comes in January of next year, I see a lot of echoes back to 2009 where Obama came in during a pretty tumultuous time for the country economically. So there's going to be economic issues. You're going to be taking in the presidency in the context of the virus. And as you pointed out, space is going to be very low on the list of immediate priorities. And then kind of working into that with Biden sets a general lack of personal interest in space, that's not going to kind of help bump it up at all.

Casey Dreier: In that context, it strikes me as it almost works towards consistency for particularly the human spaceflight program, because as you kind of point out, you're probably not going to see any major reshuffling because that would create a political battle where you don't really want one. If you need all of your political chips being put down for virus or economic response, you don't want NASA to be taking up much energy. Is that something that seems like a good way to kind of think of this?

Jeff Foust: Yeah, I think that's a good assessment. I think the big difference between 2009 and what a Biden administration might see in 2021, is that the Obama administration in 2009 was effectively on the clock. The shuttle was in it's final couple of years of operations, it was down to a final handful of missions. There was pressure to see whether NASA's current approach to the future of human spaceflight, the Constellation Program was the right approach or not that had been underway for a few years. There are questions, not surprisingly, about costs and schedule overruns that prompted the Augustine committee in 2009, bringing together a blue ribbon panel to look at it and make its recommendations.

Jeff Foust: That prompted the changes that the Obama administration made or at least tried to make in 2010 regarding human spaceflight. The difference now is that there is no real urgency. The space station is going to be operating barring any sort of unfortunate incident probably through most of the 2020s.

Jeff Foust: So there's no sort of short term deadline to deal with the ISS there, you've got a plan to return humans to the moon but if you don't get to the moon by 2024, it's not like the program falls apart. If you get there in 2026 or 2028, there might actually be a bit more technically reasonable approach, maybe a more fiscally reasonable approach depending on how things work. You don't have the same level of urgency that the Obama administration face, which I think would bolster the argument that you're making for a greater degree of continuity, that instead of making wholesale changes to NASA's programs, you look at refining some of those.

Jeff Foust: Maybe that means refining the human landing system program and how the landers are procured. Maybe that means moving away from a 2024 goal, maybe we get something closer to what actually NASA was pursuing a couple of years back when it was talking about setting up the gateway first and then landing humans on the moon around 2028 until Vice President Pence's speech in March of last year that moved up the deadline to 2024 and took up that policy. You might see changes like that but you would not see sort of the wholesale disruption otherwise.

Casey Dreier: And I guess to add to that list of differences from the Obama transition to a potential Biden transition, the SLS and Orion are far further along programmatically than the constellation hardware was at that point. In a sense, it'd be much more disruptive, I would think to attempt to say there's always the ongoing issues with SLS and large contingents of the space advocacy world that says to cancel the SLS or so forth and so on.

Casey Dreier: But I always considered a pretty stable program and particularly again, during a transition here, it'll have been going on for 10 years at that point. That seems like it'd be much harder to pull off than what they tried to do with constellation.

Jeff Foust: Yeah, I think that's a fair assessment in that there are a lot of criticisms of the SLS in particular in parts of the space community but Congress still funds it, whether it's Democrats or Republicans in charge. The house actually added money to the SLS program in its fiscal year '21 spending bill that with a democrat controlled house, because they were members, particularly some of the Republican leadership of the Appropriations Committee pushing for that money, it was very easy to say, "We'll go ahead and we'll add that money to that. We'll just add money for science as well."

Jeff Foust: You don't have any obvious sign that a Biden administration would come in and say, "We're just going to shut down the SLS on the eve of its first launch." That doesn't seem to be a likely outcome simply because it's not going to be a priority for them. And to try and make a move like that would prompt a lot of opposition probably among members of both parties, depending on where they represent in their roles and in the program if they tried to do something like that.

Casey Dreier: We've talked a lot about implicitly here, human spaceflight side of NASA, which tends to be the shorthand for when people talk about what a president wants to do with space exploration. But your background, I should note, is in planetary science. In addition to being a great journalist on space, you just picked up your doctorate in that area too. But let's talk about on the robotics side and the science side of NASA, what are ways that a Biden administration would approach this if any way differently than what we're seeing now under the Trump administration?

Jeff Foust: Yeah. I don't see any signs that they would make major changes to the robotic exploration, the science program. As you noted, the platform specifically calls out continued, in fact, increased support for Earth science, which has been a part of NASA that the Trump administration in its various budget proposals has tried to cut. And Congress has opposed those cuts, and basically kept the Earth Science Program pretty well funded, despite those efforts to in particular kill some of the Earth science missions.

Jeff Foust: We've seen the same thing in astrophysics, the [inaudible 00:44:21] now the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope has been on the chopping block for a couple of years in NASA budgets and Congress has continued to provide funding for that mission. There are signs that that will continue to be the case as the FY-21 preparations continues to work its way through Congress. I don't see any signs that the Biden administration would try and do anything like that but again, that's a sort of a lower level issue than even the human spaceflight program, which is we previously discussed, it's not a particularly high priority issue likely for a Biden administration.

Jeff Foust: It'll be interesting to see how much they commit to as administrator Bridenstine often does, he says, "Well, we're going to follow the cadle. Whatever the recommendations in the cadle are, we'll continue to follow them." And certainly, that's going to be important as the Astro 2020 decadal survey wraps up and gets published early next year as the planetary science decadal survey starts to ramp up right about now for publication in 2022 in terms of what priorities it sets for future astrophysics in planetary science missions and the funding requirements.

Jeff Foust: I expect to see a fair amount of continuity in that as well, some of the big flagship missions like Europa Clipper and Mars Sample Return and programs like that that take years to execute, and billions of dollars and require some degree of policy stability in order to successfully execute.

Casey Dreier: Yeah. And that's where I think the value of having those decadal surveys, I mean, that's the advantage in a sense of the science side of NASA, where you have these 10-year agreed upon priority documents that help design specifically for these types of transitions. And of course, human spaceflight doesn't have that. Doesn't have that kind of same process by which to forge that kind of broad policy agreement. And so you just tend to see less, I would say, and maybe it's more kind of what you were saying there, a matter of degree of support.

Casey Dreier: What's the relative priority in terms of funding to pursue some of these various aspects of science? And I think, just looking at Joe Biden's campaign literature in terms of how he talks about climate change and of course, the relative prioritization of Earth Science under an Obama administration back when we saw that, you would likely see, I would say, more funding directed towards Earth science as a priority and then kind of given the overall economic status, everything else would be kind of slotted in based on that. But that would seem to strike me as a priority based on these intersections with Biden campaign priorities.

Jeff Foust: Yeah, I think that that's true. Like I said, it's not a high priority for them. But certainly he's... Biden has talked about supporting what the scientists say whether it comes to climate change or developing responses to the pandemic, might as well keep supporting scientists when they come up with recommendations about planetary science and astrophysics and other missions.

Casey Dreier: Right. In a sense, I think we're both kind of circling around in a sense, it's not very newsworthy in a way, that it seems like there'll be a lot of consistency. But what would you say, just to kind of really state it clearly here at the end of our discussion, the most likely areas of change or of disagreement or let's say divergence between the two potential administrations in the next four years, what do you see that the most likely deviations happening from the current path?

Jeff Foust: I think the biggest deviation is going to be in the pace of human space exploration. We've got the policy to return humans to the moon by 2024. That is a very challenging goal. If you talk privately to people at NASA, they know it's going to be tough to achieve, but if you don't set that sort of audacious goal, you're not going to achieve it. But I would expect the Biden administration to come in and say, "We can save money in the near term, to push out that deadline, keep going with the Artemis program in general, SLS, Orion, develop human landers at a slower rate, do more robotic missions to the moon, work on the gateway, but push off the expense of the human landing system program," which is if you look in the strategy that NASA put out recently about its lunar exploration plans, a big chunk of the money that it expects to spend on it over the next five years is on the human landing system program, simply because a lot of the other elements like SLS and Orion are nearing the end of their development.

Jeff Foust: I could see a Biden administration coming in and say, "Let's slow down on that. We support returning humans to the moon, but it doesn't have to be done by 2024. It can be done at a slower pace." We may see again, some of the things that NASA has been trying to do with low Earth orbit commercialization gets slowed down as well if the administration thinks that spending money on supporting commercial space stations could be funding better spent elsewhere in the agency, or outside of the agency. Those might be areas where we'd see the biggest change.

Jeff Foust: But I think again, as I said, it's more sort of not a veering off in a completely different course, but slowing down a little bit, taking the foot off the gas rather than taking a sharp turn at the next exit, sort of approach to space policies. I think those would be the most likely large changes that we would see in NASA.

Jeff Foust: I don't see big changes in the science program or space technology or aeronautics. Space technology and aeronautics tend to be smaller programs anyway, don't get a lot of attention, even in the best of times. I wouldn't expect a lot of changes there. Where I would expect to see changes are some of the big ticket exploration programs, particularly if the administration comes in and says, "We've got a lot of other higher priorities to deal with the economy and the pandemic and so on. A human return to the moon could wait a couple of years."

Casey Dreier: All right. Jeff Foust is the senior staff writer at SpaceNews and he also writes the daily newsletter, which I strongly recommend, FIRST UP. You can subscribe at spacenews.com. Jeff, thanks so much for joining us today and helping us work through this.

Jeff Foust: Well, thanks, Casey. It was a great discussion and I was glad to be on the show.

Mat Kaplan: Planetary Society Senior Space Policy Advisor Casey Dreier talking with Jeff Foust of SpaceNews, and the FIRST UP newsletter and you can check that out by the way, it's free from spacenews.com. As I've said, that's how I start my work day every day, reading Jeff's stuff. It's quite a comprehensive collection of everything that's going on above our heads and a lot of it down here on the ground. Casey, great job.

Casey Dreier: Thanks, Matt. And again, just thanks to our guest, Jeff Foust for joining us today. Next month, I believe Matt, we will be recording after the election. So we can discuss whether these predictions or analyses are going to be more or less relevant at that point. And hopefully, there'll be some exciting... We'll be celebrating the launch of the first full commercial crew complement to the space station, which is now set for October 31. So something inspiring to look forward to.

Mat Kaplan: Very exciting. If the first Friday in November weren't after the election, it's November 6, I think we'd want to push the show back a week, but we don't have to. We hope that you will all rejoin us again on the first Friday in November for the next Space Policy Edition. Of course, I'll be around weekly with the regular Planetary Radio and lots of great stuff coming up there.

Mat Kaplan: In fact, I will mention our poetry Space Poetry Spectacular coming up on October 14. Join me and the editors of a terrific new collection of poetry about space and space exploration and a whole bunch of celebrity poem readers. One more plug, visit us at planetary.org/membership. Please take a look. Look at all the great stuff that we have underway. Look at all the benefits for you as a member of the society and how inexpensive it is to become part of the society.

Mat Kaplan: Again, it's planetary.org/membership. Casey, I look forward to our interacting over the next month and to joining you for the next space policy edition.

Casey Dreier: Me too Matt. I always look forward to it. First Friday of the month.

Mat Kaplan: To all of you, have a great month. Those of you who are in the United States. Please vote if you haven't already. We will see you on the other side of the election. This is Mat Kaplan. Ad Astra everyone.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth