Planetary Radio • Sep 30, 2020

Exploring the Cosmos With Heidi Hammel and AURA

On This Episode

Heidi Hammel

Vice President, Board of Directors of The Planetary Society; AURA Vice President for Science

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

AURA, the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, is the organization that oversees operation of many of our world’s most powerful telescopes, including the Hubble Space Telescope. Veteran astronomer and planetary scientist Heidi Hammel is its Vice President for Science. Listen to her passionate argument for exploration by ground and space-based instruments and what they may tell us about ourselves. Only one cat has gone to space! You might win a tribute to that feline in the new What’s Up space trivia contest.

Related Links

- Heidi Hammel

- AURA: The Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy

- NOIRLab: The National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory

- National Solar Observatory

- Space Telescope Science Institute

- Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics 2020 (Astro2020)

- The Downlink

Trivia Contest

This week's prizes:

A poster from Matthew Serge Guy, creator of the successful Félicette space cat Kickstarter campaign. Félicette was the only cat to visit and successfully return from space. Posters were designed by distinguished artist and illustrator Louise Zergaeng Pomeroy.

This week's question:

What 3 Apollo spacecraft call signs were later used as names of Space Shuttle orbiters?

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, October 7th at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

What is the largest rock returned from the Moon by Apollo astronauts? Either its official name or nickname is acceptable.

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the 16 September space trivia contest:

Who is the only man who has a feature on Venus named after him?

Answer:

The only man who has a feature on Venus named after him is James Clerk Maxwell.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: Heidi Hammel's aura shines a light across our solar system and toward other worlds, this week on Planetary Radio.

Mat Kaplan: Welcome, I'm Mat Kaplan of The Planetary Society with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. Great missions, powerful telescopes, you'd think we must now know our solar system like the back of our collective hand. Ha! We've mostly revealed more profound and exciting questions. Astronomer and Planetary Scientist, Heidi Hammel, is a leader in the search for answers largely through her work at AURA, the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy.

Mat Kaplan: She's back with lots of inspiration and news to share. That will be our focus until we check in with The Planetary Society's chief scientist. You might win the spitting image of the only space cat in history when Bruce Betts offers another space trivia contest. The Planetary Society went loony a few days ago. We celebrated International Observe the Moon Night with lots of special features. There's a nice guide to them at the top of this September 25 edition of the downlink available to all for free at planetary.org/downlink.

Mat Kaplan: It also includes these headlines, NASA says it is on track for the first flight of a space launch system rocket. The uncrewed Artemis I mission will send an Orion capsule to the moon and back next year. Can a rock throw rocks? Asteroid Bennu does, and the OSIRIS-REx team may have figured out how. It seems to be connected to the afternoon sun heating the surface. Bennu's aggressive behavior is a bit more understandable with the revelation that its own surface may have boulders hurled from asteroid Vesta. They are called, what else? Vestoids.

Mat Kaplan: And astronomers have, for the first time, found a planet orbiting a star that died long ago. It's a Jupiter-sized giant called WD 1856b, and there's a surprising artist concept in the downlink.

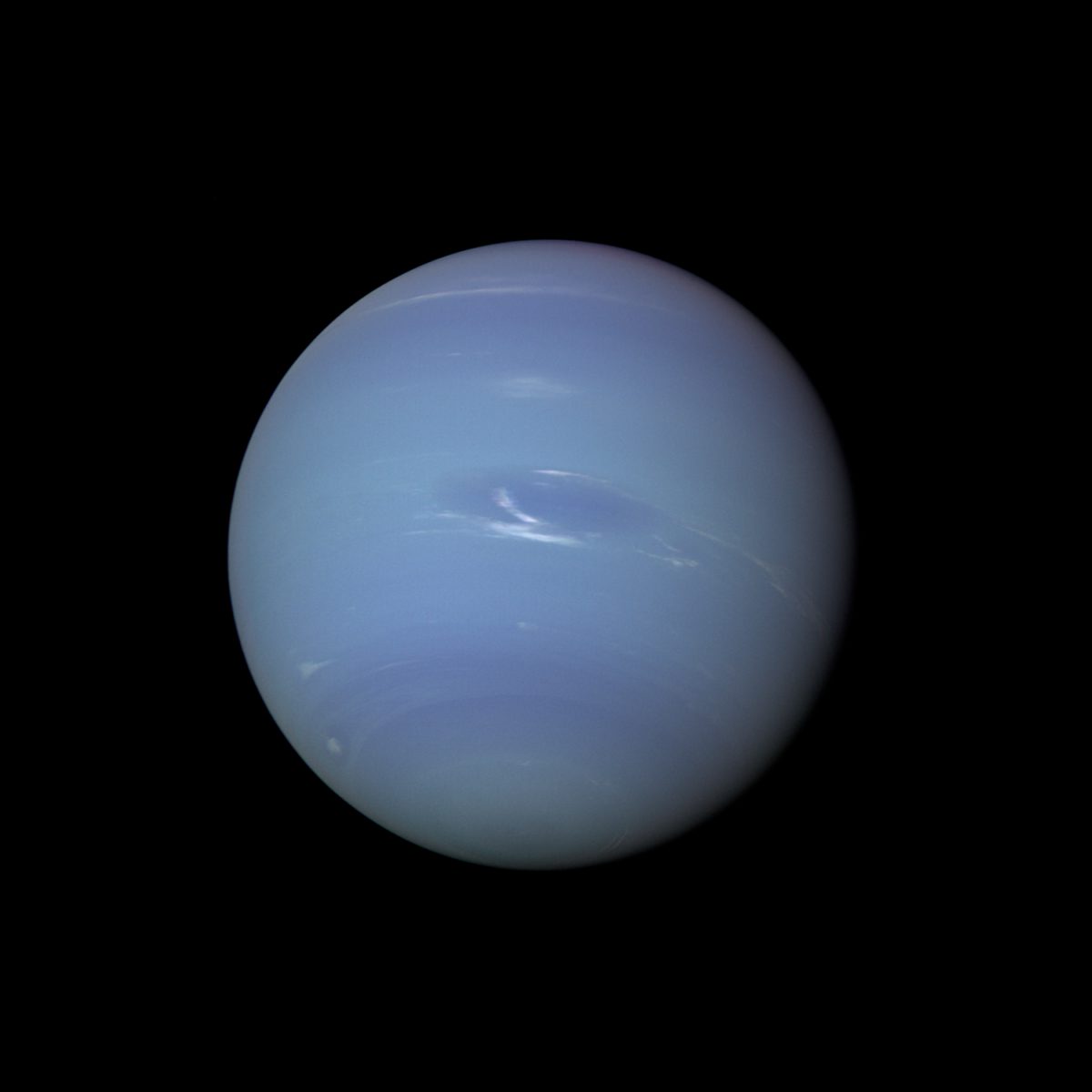

Mat Kaplan: Heidi Hammel has been utilizing humanity's most powerful telescopes for many years. She was on the imaging team when Voyager 2 encountered Neptune in 1989. That began a lifelong fascination with the so-called ice giants, Uranus and Neptune. Five years later, she led the team that used the Hubble Space Telescope to investigate Jupiter's atmosphere as comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 hurled into it. She was a principal research scientist at MIT and spent years with the Space Science Institute.

Mat Kaplan: Now, she is the vice president for science at the organization that oversees many of the instruments she has used in her own research. The American Astronomical Society has just given her the 2020 Harold Masursky Award for meritorious service to planetary science. That's one of the reasons I so look forward to welcoming her back to our show.

Mat Kaplan: Heidi, welcome back to Planetary Radio.

Heidi Hammel: Hi, Mat. It's great to talk with you again.

Mat Kaplan: Always great to talk with you. Do you realize that your first time as my guest on this show was nearly 15 years ago in 2005? Guess what we talked about, Uranus and Neptune.

Heidi Hammel: Not surprising. I love those planets. Maybe we'll talk about them some more today.

Mat Kaplan: Oh, we definitely will although it may be a few minutes before we get to them. But on that topic, the last time you were heard on the show was on that great New Year's Eve, which is now almost two years ago when New Horizons flew past what we now called Arrokoth. In that brief conversation, you said, "Every world deserves to be celebrated and explored." I bet you haven't changed your mind?

Heidi Hammel: I have not. I stand by that statement. Our solar system is filled with fabulous worlds of all sizes and compositions and types of atmospheres and interesting geology, and each one of these worlds has something to teach us about planetary science. Of course, now, we know of thousands of worlds orbiting other suns and those worlds too all have their own unique stories to tell. What a rich time to study planetary science.

Mat Kaplan: And I would say that that philosophy probably had something to do along with your accomplishments in your being presented the Masursky Award by the DPS, Division of Planetary Sciences, that division of the AAS as we said in your intro. So, congratulations on that.

Heidi Hammel: Thank you very much. It's really an honor to be recognized by my peers especially for service to the community. That's something that sometimes these rewards and honors tend to go for fabulous science results and that's great. But I also believe that we owe it to our peers to serve our communities and do what we can to advance our field.

Mat Kaplan: Well, you know we stand behind that at The Planetary Society. Let's get to how you spend your time nowadays. Beginning with AURA, I bet a lot more of our listeners have heard of the Space Telescope Science Institute than they've heard of AURA even though AURA operates the STSI. I'll bet you even fewer have heard of NOIRLab. In fact, I only learned about it because you appointed an old friend of Planetary Radio, Patrick McCarthy, to head it. That's surprising considering the amazing group of telescopes that are part of NOIRLab.

Mat Kaplan: But we'll talk about that in a second. First, tell us about AURA.

Heidi Hammel: Sure. When I started working for AURA, people asked me, "What is AURA?" And I respond, "It's the best-kept secret in Astronomy."

Mat Kaplan: Here you go.

Heidi Hammel: AURA is a managing organization. AURA manages for the United States government very large telescopes in space for NASA. We are the managing organization of Space Telescope Science Institute. As you said, you don't think many people heard of AURA. More have heard of Space Telescope Science Institute. But in fact, I think many people haven't even heard that. But they have heard of Hubble.

Heidi Hammel: And Hubble Space Telescope is this amazing tool that we've been using for over 30 years now, but the science interface for that comes through the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland. When astronomers want to use Hubble, they write proposals once a year typically and they all go to Space Telescope, and they're evaluated and they're eventually turned into observing proposals for that telescope.

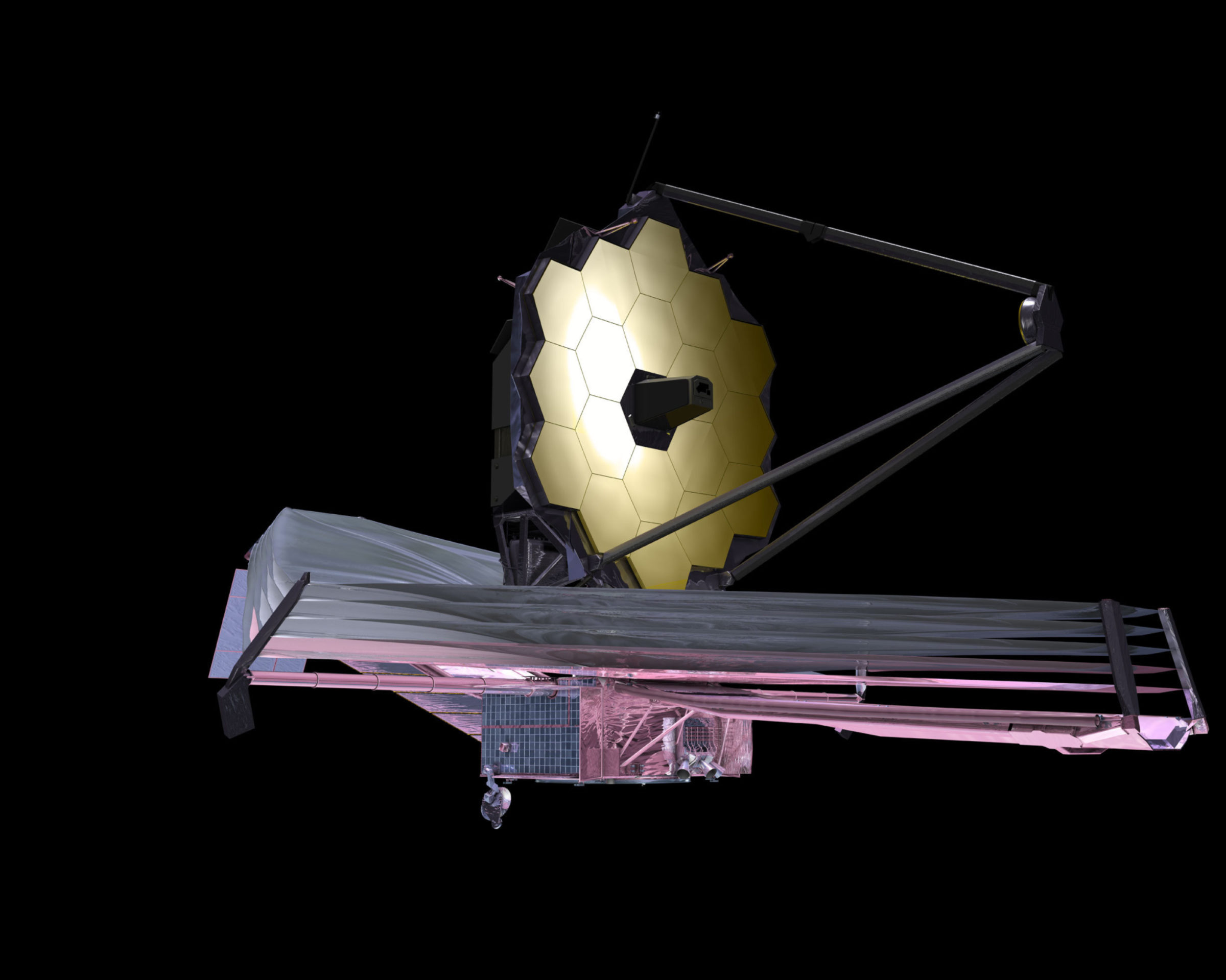

Heidi Hammel: The Space Telescope Science Institute will also be the managing organization and the operating center for James Webb Space Telescope once it is up and operational at Earth-Sun Lagrange 2-point. That's the space side and there are other things we do in the space side there. We run a big archive of lots of space astrophysics data from Hubble, from the test spacecraft, and other assets.

Heidi Hammel: On the ground-based side, for the National Science Foundation, AURA is the managing organization for the optical and near-infrared telescopes that are run on behalf of US community. And I make that distinction because there's another group that manages the radio telescopes like the VLA. That's in the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. That's a different group.

Heidi Hammel: But the optical telescopes, those are managed by AURA and they used to be run by AURA somewhat independently. We had what we called NOAO, National Optical Astronomical Observatories that ran Kitt Peak and Cerro Tololo. We also separately, we're running the Gemini Observatories for NSF, the managing organization and those are two 8-meter telescopes. One in Hawaii and one in Chile on Cerro Pachón.

Heidi Hammel: And we were also separately building the Rubin Observatory, formerly called the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope. It's under construction right now in Chile. And the entity you mentioned, NOIRLab is a new managing organization that just takes all of those disparate pieces and combines them into one managing organization. And so, it is a new structure, a new name for people but it is many of the same telescopes that we've been operating for many, many years. We're just operating them in a different management style.

Heidi Hammel: We're doing that for a lot of different reasons. One of them is to be able to more effectively share resources across the different centers. If you have someone at Gemini, but they're needed on a project for Rubin operational activities, then if they're in the same organization, it's much easier to transfer them. You don't have to fire them from one and hire them in another.

Heidi Hammel: And since all of these groups were being managed by AURA, it made sense to bring them all together. National Science Foundation asked AURA to do that and so we've spent a lot of time and energy doing that and making sure it's going to be a robust and exciting new organization, kind of the center of ground-based optical astronomy for the United States. That just kind of raison d'être if you will.

Mat Kaplan: I mentioned Patrick McCarthy who has been on the show several times, but in the past to talk about that other big telescope that's currently going up in Chile, the Magellan Telescope. Well, now, he is running NOIRLab. Because I know Patrick, I can say he's quite a catch.

Heidi Hammel: Thank you. We are very pleased that he decided to come to AURA, into the AURA fold to be the leader of NOIRLab. He's a terrific manager. He's a great scientist. He has all the attributes that we look for in the leaders of our organizations. So, we're very, very pleased that he has joined us.

Heidi Hammel: And someday, you can bring him back to talk about NOIRLab and some of the exciting projects that are going on with NOIRLab. Mostly, looking forward to what we're going to do with the current facilities and then also with Rubin Observatory, the amazing science that it will do when it is operating. That will be under the auspices of NOIRLab.

Mat Kaplan: We could spend the rest of this time we have together talking individually about each of the instruments, each of the observatories, but there are a couple I want to call out. And by way, Patrick is welcome any time. I hope you're listening, Patrick.

Mat Kaplan: You've mentioned the Vera Rubin, formerly the LLST. I think I have that right. What is so special about this telescope? We've actually heard it mentioned a few times on previous shows.

Heidi Hammel: Yeah. It's going to be a new kind of telescope for us. It's going to be doing a very deep wide survey of the southern sky. Basically, the entire southern sky will be imaged every three days. So it will tile its way across the sky, and then three days later, it will go back and tile that piece of sky again.

Heidi Hammel: That will allow us to study the sky in a new way, in a way that we called time domain science. We won't just be looking at one particular object in the sky and study how it may change with time. We'll be able to study all of the objects available to this telescope in the southern sky. Every day, it will send out alerts that people will have defined saying, "This object has changed." People will define their own alerts.

Heidi Hammel: There may be people who were looking for a certain kind of variable star, and they'll craft an alert that will alert them that one star has varied in the way that they're looking for. So they'll be able to go and follow it up right away with other telescopes. It's going to be a different way of doing astronomy. You won't apply for time on it, like you do for Hubble.

Heidi Hammel: Like Hubble, if I want to look at Neptune, I just write a proposal. Once a year is my opportunity. I want to look at Neptune. Somebody else may want to look at the Crab Nebula. Somebody else want to may look at the Red Rectangle. That's not how we're going to do things with the Rubin Observatory. It is going to be conducting a major survey and that survey is going to be the input to the science that the community will do with it. That's going to be fun.

Mat Kaplan: There are a lot of people in the Planetary Defense Community or people who study asteroids, comets who are very much looking forward to this telescope even though it will also be looking out toward the ends of the universe.

Heidi Hammel: Yeah, that's right. It's being crafted with four themes in mind and one of those themes is, in fact, a census of the solar system. Near-Earth Objects which are objects that are close in their orbits to the Earth and some of them may, at times, interact with the Earth in ways that could potentially be dangerous.

Heidi Hammel: A lot of effort is being put into thinking about the best ways to use the Rubin Observatory and its survey to build up the population of bodies that we know are Near-Earth Objects. So it will work in conjunction with other activities that are already ongoing for Near-Earth Objects, things that NASA is organizing. There are many surveys right now, but this will be a really robust survey. It will, of course, last for 10 years. That's the prime operating mission of the LSST survey.

Heidi Hammel: This little thing that kept the LSST name, it used to stand for Large Synoptic Survey Telescope. That was the working name. Now, of course, it is called the Vera Rubin Observatory. But it will be conducting the legacy survey of space and time, LSST.

Mat Kaplan: I love that. What a great repurposing of that abbreviation.

Heidi Hammel: Yeah. So the LSST, if you hear that from here on out, that will refer to the survey itself, the data. There are other spacecraft that NASA is thinking about that will also do survey work and The Planetary Society has been supportive of that work and also supportive of this Rubin Observatory's LSST survey.

Heidi Hammel: So it's going to really help us understand the population of these bodies in our vicinity which, you know what, I think we all ought to care about. We have a lot of challenges we face here on earth but there can be challenges from outside the earth as well. But those are challenges that we can actually identify and prepare for. And so, that's what this will do.

Mat Kaplan: Before we leave the Vera Rubin Telescope coming together in Chile and we should also say that that new name acknowledges one of the greatest astronomers of the 20th century, Vera Rubin, of course. Can you say a word or two about the amazing camera that will sit at the focus of this instrument?

Heidi Hammel: Yeah. It's astonishing. It's a huge camera. I don't think I can do justice to that conversation. I think that I'm going to suggest you get Pat McCarthy on here and have him talk to you about that camera, because it's a scale beyond any camera that we've ever built before.

Heidi Hammel: When I say "we", I want to be clear, this telescope is a collaboration between the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy. And the Department of Energy Office of Science and particularly SLAC, they are the ones who are specifically building the camera. It's a great collaboration between their camera and then the telescope system that is being built by NSF.

Mat Kaplan: There's just one other telescope within the NOIRLab family that I want to mention. You brought it up briefly but I have always had been fascinated by what this two-telescope combo accomplishes and it is appropriately called Gemini.

Heidi Hammel: Yeah, the Gemini Observatory, the two twin 8-meter telescopes. They are terrific telescopes. I myself have used them to do work in the outer solar system and what they're doing now with them is they're positioning them for this new era of science that we're moving into with the Rubin Observatory. They are optimizing the adaptive optics system on Gemini. They both already have adaptive optics systems. And for your listeners who may not be aware what I mean by that, all of our ground-based telescopes have to look through Earth's atmosphere.

Heidi Hammel: But astronomers had become very clever in the last 15 to 20 years. We have developed systems that involved shooting lasers into the sky that make guide stars that we can track. And by tracking those guide stars, we can take out the effects of our Earth's atmosphere to a large degree, and we call that adaptive optics. They are upgrading the adaptive optic systems on the Gemini Observatories to make them even more powerful.

Heidi Hammel: I'm really excited about Gemini and where it's going to be going. I want to mention that Gemini is an international collaboration. It's not just the US. There are other international partners including Canada, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, the host country. South Korea is the newest partner and a very valuable partner as well. Terrific international collaborative organization that we operate on behalf of the international consortium through NOIRLab. It's a great telescope system.

Mat Kaplan: And we will put up links to AURA, to NOIRLab, and everything else that AURA is up to at planetary.org/radio on this week's show page. You can learn a lot more by visiting that page. There is a wonderful montage by the way at the top of the NOIRLab website that combines all of these telescopes in one beautiful image. There is one other observatory before we leave the surface of Earth that AURA also operates and you probably know what I'm talking about, the National Solar Observatory.

Heidi Hammel: Yeah, NSO. The headquarters is in Boulder, Colorado, but the flagship facility is being built on Haleakala, which is a volcano in Hawaii and that is the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope. This is a 4-meter class telescope that will do but one thing, it will study the sun. Any of us who have ever done this experiment as kids where we took a little magnifying glass and then burn little bits of paper by focusing our little magnifying glass sunlight on little bits of paper. You might wonder how you could focus a 4-meter telescope mirror on the sun and not burn your building down.

Heidi Hammel: And the answer is it's a stunning piece of technology that involves something of the equivalent of seven miles of cooling pipes running through the building, the telescope itself, the instrument area. All of it is continuously cooled so that we don't overheat everything, don't melt our instruments, et cetera. It's really pretty amazing. And this telescope has seen some first light already with one of the instruments. You can probably put a link to that. It was the highest resolution image of the surface of the sun ever taken, truly astonishing.

Heidi Hammel: People might say, "Well, wait a minute, hasn't NASA's spacecraft liked to orbit the sun and take pictures?" I'm like, "Yeah, but those are relatively small spacecraft compared to this telescope." And so, the images are the highest resolution images we've ever gotten, and that was just our test images taken late last year.

Heidi Hammel: When the telescope becomes fully operational with all of its instruments, it's going to really change our understanding of the magnetic fields within the sun's surface. And it will work in tandem with the NASA Parker Solar Probe which is out there right now studying the sun, and also ESA's Solar Orbiter Mission which is launched pretty recently.

Heidi Hammel: So these three facilities, they are really going to change our understanding of the sun. This is going to be a really interesting solar cycle because we're going to have a whole new raft of information about our local star that we've never had before. We talked earlier about protecting our planet from near-earth objects, another thing that we worry about in the space is solar storms, space weather, impacts of the sun on our Earth environment and understanding the sun and what drives coronal mass ejections and major solar flares.

Heidi Hammel: That's very important for us to be able to plan to protect our assets in space and on the ground from some potential future major solar flare. People often think of astronomy as just sort of esoterics studying the universe. But we also think of it in terms of protecting our species, protecting our planet from a hostile universe.

Mat Kaplan: You know what that boss says at The Planetary Society, we're just trying to save the world.

Heidi Hammel: Just trying to save the world, absolutely.

Mat Kaplan: That's astronomer and Planetary scientist, Heidi Hammel. Much more is ahead. We haven't even talked much yet about Uranus and Neptune, but we will.

Jennifer Vaughn: Thanks for listening to Planetary Radio. Hi, I'm Jennifer Vaughn, chief operating officer at The Planetary Society. Want to support this show and all the other great work we do? Help us reach our goal of 400 new members by October 6. When you become a Planetary Society member, you become part of our mission. Together, we enable discoveries across the solar system and beyond. We elevate the search for life and reduce the threat of a devastating asteroid impact here on Earth.

Jennifer Vaughn: Carl Sagan co-founded this non-profit 40 years ago for all of us who believe in exploration. Can we count on you? Please join us right now at planetary.org/membership2020. Thank you.

Mat Kaplan: Let's leave the surface of Earth where yes, adaptive optics do make miracles happen, but there's nothing like getting out there beyond the atmosphere. You mentioned Hubble. I think we're all pretty familiar with what it's accomplished. It sounds like we are finally getting close to seeing the James Webb Space Telescope unfold that big mirror and build on what Hubble has done.

Heidi Hammel: Yeah, no one is more excited than I am about that. I've been working on this project for over 20 years, something like 18 or 19 years formally and then a couple of years before that in sort of a volunteer fashion. It's been a long road, but I'll tell you this, when we designed Webb back more than 20 years ago, it was so revolutionary that it is still revolutionary today. That's why we are so excited about getting to the point where we're at now.

Heidi Hammel: We now have an integrated spacecraft. The optics are connected to the spacecraft bus and that's all connected to the giant sun shield that will protect this telescope from sunlight, earthlight and moonlight and keep it cold. That's altogether, we're doing the final rounds of testing of all these things. As of today, we are looking towards an October 2021 launch date. That's right around the corner as far as I'm concerned.

Heidi Hammel: All of our proposals are already in. When I say "our", I mean, those of us who are working on this project. I'm one of the interdisciplinary scientists for this project. I'd served on a science working group, one of the team members who are, like I said, about 18 years now. We have some guaranteed time to do science with this and all of our guaranteed time proposals are already submitted and are in the queue. We had to do that early because we have to make sure that people know what those proposals are so they don't try to replicate them or reproduce them. We want to make the most efficient use of this telescope.

Heidi Hammel: And so, my observations with my guaranteed time are focused on our solar system. I have a very large team, many dozens of scientists around the country and in other countries who put together subprograms, if you will. There's a team specifically looking at comets. There's a team specifically looking at near-earth asteroids. There's a team specifically looking at Saturn's rings and small moons. Another team is looking at Uranus and Neptune.

Heidi Hammel: So you get the idea?

Mat Kaplan: Yeah.

Heidi Hammel: Sort of a sampling across the solar system. All of the time that is within my program that is not shared with other teams, all of that time is going to be immediately available to the Planetary Science community. None of it is being held super secret, and we're going to skim the cream off the top and you guys can look at what's left. All of this time is going to the Planetary Science community so that they can better prepare for their own proposals for future cycles with James Webb Space Telescope.

Heidi Hammel: That was in part what the Masursky Award was for, for being open with that time, not holding it to myself or to my science, but to really just giving it all back to the community and making sure that the whole Planetary Science community has the opportunity to see what James Webb Space Telescope will do in our solar system.

Mat Kaplan: Well, that was certainly worthy of recognition, that policy. I cannot wait for first light. But even as we look out still a year to the launch of Webb, you mentioned in passing, there is this follow on to the web which will do something else up these. We used to know it as WFIRST, just a word or two, please, about it.

Heidi Hammel: Yes, this facility has now been named the Nancy Roman Telescope. We call her the mother of Hubble. She was the chief scientist at NASA during the formative stages of the Hubble Space Telescope, very, very long time ago. And it was her vision and her perseverance that allowed that facility to come to fruition. So this new facility, the Roman Space Telescope, it's going to be like Hubble. It uses the same size of mirror as Hubble, but instead of being a pencil beam like a tiny piece of sky like Hubble is, it's going to be a wide field telescope.

Heidi Hammel: So, things that normally would take hundreds of pointings of Hubble to build up into an image, this telescope can do in basically one or two pointings. One or two pictures, and it will be the equivalent of a hundred Hubble pictures. It's going to be great because that's going to be a space-based survey that will complement the Rubin ground-based survey. We have Rubin and Roman, both going to be doing this survey mode of the sky. It's going to be a really fascinating time to be doing astrophysics and planetary science when both of these survey telescopes are operational.

Heidi Hammel: Roman still has ways to go. It's moving forward but it's nowhere near as complete as Rubin is right now. But, boy, looking forward to it.

Mat Kaplan: It is such an exciting time with all these new instruments and other telescopes that are coming together here down on the surface looking forward to JWST and so on. I know there is this phrase that astronomers like to use, "Great Observatories." It's kind of what we've been talking about, isn't it?

Heidi Hammel: Yes and no. We don't consider every large telescope a great observatory. That phrase was coined specifically to refer to a suite of telescopes of which Hubble was one, something like 23 years ago while we were trying to have a suite of facilities that covered multiple wavelengths of light. Hubble is an optical telescope primarily, UV optical, near-infrared. But astronomers also are very interested in x-rays from the universe and they're also interested in very long infrared wavelengths.

Heidi Hammel: And so the concept of the Great Observatories would be to have a suite of telescopes that are working together to do the infrared, the optical, the x-ray even maybe the gamma rays, all working together so that we get a holistic picture of what the universe is like. And we did that. I mean, Spitzer Space Telescope was an infrared telescope. Chandra was an x-ray telescope. Hubble was our UV optical telescope. But they're all either done or they're aging. I have been so pleased with the Hubble Space Telescope and how well it has been operating since the last servicing mission.

Heidi Hammel: But the last servicing mission was 2009. And we're now 2020. We are not looking at a forever for Hubble. There's going to be an end time. Spritzer Space Telescope has ended. Chandra just had a scare recently, but it is back and so that's good. But it is an aging spacecraft as well.

Heidi Hammel: What some of us had been thinking about is a future where there is a new great observatory suite. We're not talking about next year. We're not talking even like maybe 10 years from now but we're talking about maybe 20, 25 years from now whether or not we can put together a strategy to develop a suite of next generation great observatory. So, a very large UV optical telescope, a new generation x-ray facility, a next generation infrared telescope beyond James Webb Space Telescope.

Heidi Hammel: The more we learn, the more questions we have. And the more questions we have, the closer we get to deeper understanding of the universe. So, we do tend to want to continue onward and beyond what we have.

Heidi Hammel: We have a process in astrophysics. You have a similar process in planetary science as well. We call it the decadal survey process. It's run by our National Academy of Sciences and every decade, large groups of astronomers brainstorm and come together and debate and analyze what we know and what we still need to know, and what the tools may be to learn what we want to learn.

Heidi Hammel: So that process is going on right now for astrophysics. This Great Observatories idea is something that has been discussed and floated. It will be up to the decadal steering committee to evaluate all the input they're getting from all of the community and lay out a path for the future. That will be likely coming out sometime early to mid next year, early to mid-2021.

Heidi Hammel: So, we're all looking forward to that, waiting with bated breath, hoping that it is ambitious and visionary and wonderful because certainly our dreams are visionary and ambitious and wonderful.

Mat Kaplan: Great Observatories, the next generation, I love that. As you know, Heidi, there is also a decadal survey that has begun, the current decadal survey to consider planetary science. And the missions that may take us in the coming years up close and personal to these objects in addition to the importance of looking at them from a distance with these wonderful telescopes.

Mat Kaplan: That process, of course, has a lot to consider. We'll have a lot to consider. It's seeming as we've heard in recent days, maybe Venus is going to get some of the love that it's been lacking. But I know that while you applaud that, you're also looking out there toward those ice giants and getting a mission back to them to follow up the only one that has ever reached Neptune and Uranus. Talk about that. Is this still something that you and others very much want to see?

Heidi Hammel: There are a lot of people in the community who would love to see coordinated mission to the deep outer solar system, either Uranus or Neptune. As you said, there's only ever been one short flyby of each of those. That was a very long time ago and with far less capable instrumentation and computational ability than we have today. So, there is a huge richness awaiting us out there.

Heidi Hammel: We tend to get engaged with the planets that we have been studying because we know so much about them. And so there's more ... As I said with the universe, it's same with planets, the more you explore, the more you learn, and the more questions you have and the more you want to explore.

Heidi Hammel: The way I have been kind of thinking about the coming decades of planetary exploration is I've been trying to think of them more holistically and not necessarily just destination based, like making sure we check a box with every single planet. Certainly, Uranus and Neptune require some checks because very little has been done out there with modern technology. But I've been thinking a lot about all of the planets that we now know of, the thousands ... 4,000 last I checked, over 4,000. And thinking about what we know about planets in general from that knowledge.

Heidi Hammel: I've been kind of framing in my own head knowing what we now know about the broad continuum of planets that exist from the largest super Jupiters to regular Jupiters, to Uranus and Neptunes, to sub-Neptunes or super Earths down to Earths and now the even smaller objects. That's a continuum and we have some samples of that continuum in our solar system. We have studied some of those samples in our solar system to greater or lesser degrees. But there are questions about objects that we haven't addressed yet in our solar system that I think will really be valuable for exoplanets.

Heidi Hammel: Let me just give you a couple of examples, certainly as you may guess. The fact that we have so little information about the ice giant class. This is not giant but not terrestrial, Uranus and Neptune class, give so little information about their interiors, their magnetic fields, how they interact with the solar wind. To me, it's an obvious thing that we want to fill that piece of the continuum in.

Heidi Hammel: Something that may not be as obvious to people though is on the smaller end, there's been a lot of talk and fun speculation about lava world. Remember Anakin Skywalker on that lava world, right? But people are talking about that for real, planets that are very close to their suns and what their surfaces will be like, would they be covered with lava flows?

Heidi Hammel: We have a lava world in our solar system, and that's Jupiter's moon, Io. That's the only lava covered world we have and it's a doozy. I mean it's erupting hundreds of volcanoes continuously. That might be an interesting place to build into this continuum. And then as you alluded to, the terrestrial planets that we have are trio of Earth, Mars and Venus, all kind of more or less the same size. Yes, I know Mars is a little smaller but the same class of planet and yet so different in our solar system.

Heidi Hammel: How will that help us understand the terrestrial sized planets that we're seeing around other stars? We want to have kind of an equal level of knowledge of these and surely know a lot about Earth. We live here. Earth is a deeply studied planet. We have been doing extensive studies of Mars, rovers and orbiters. And we want to bring back a sample? Yeah, yeah.

Heidi Hammel: But Venus, as you alluded, it hasn't gotten quite as much love, certainly gotten more love than Uranus and Neptune [crosstalk 00:38:27] I have to say that. But nevertheless, there are many questions about Venus that are not addressed yet. The very recent announcement of the discovery of phosphine in the upper atmosphere of Venus, many people heard about it. It triggered some speculations about whether or not that phosphine could be created by life. People had talked about phosphine as a potential biosignature on exoplanets.

Heidi Hammel: I think that there's a lot of work to be done yet in our solar system with Venus to really pin that down. I'm not a Venus expert, but I do have a degree in earth and planetary science. And so, I could imagine pathways given that Venus is an active world. There is increasing evidence for active volcanoes there now. One can perhaps imagine some scenarios. It and needs to be studied and it needs to be really explored. But one can imagine some scenarios where that phosphine could be generated by geochemical processes, not necessarily by life.

Heidi Hammel: We see phosphine on Jupiter. We see phosphine on Saturn. We speculate there's phosphine on Titan. Yes, those are different kinds of atmospheres than you find on Venus but nevertheless, phosphine is not a really totally out of the blue random thing to find.

Heidi Hammel: That's important because when we then want to be looking at exoplanets, perhaps it was one of those next generation Great Observatories that I mentioned, we want to look at an exoplanet and if we see phosphine there, we want to know. Well, what did we learn about phosphine in our solar system? Was it life? Is there something floating in the clouds that is bacteria? Or is it a process related to the volcanoes on the surface and their interaction with the Venusian winds? That's important to know.

Heidi Hammel: So, there's lot of rich areas of exploration in our solar system right now. So it's going to be fascinating to see what planetary decadal survey comes up with and see how they frame their explanation for what they want to do.

Mat Kaplan: You have been very generous talking about Venus. And I will refer anyone who hasn't heard it to our episode of a couple of weeks ago where we really focused on this discovery of phosphine in the atmosphere, the Venusian atmosphere. But let's not leave the realm of the ice giants just yet. What would you like to see come out of the decadal survey? Which of these worlds ... I'd hate for you to have to pick a favorite though. And an orbiter, one with probes that drop down into the atmosphere, what do you want?

Heidi Hammel: Well, I think that a robust study of either of the ice giants would be best served with an orbiter, first and foremost, because the atmospheres and the moons, the rings, the interior, the magnetic field structure, all of that can be far better characterized if we have some time in the system rather than just a brief flythrough like we had with Voyager.

Heidi Hammel: So, I think an orbiter would be very, very useful. I do think that both of the ice giants have different stories to tell us, so I wouldn't turn down one or the other. In the case of Neptune, Neptune first of all always has a dynamic and beautiful atmosphere. There are always clouds, dark spots, things to see. So the planet will tell us about itself from an orbiter.

Heidi Hammel: Neptune also has this large moon, Triton, which is almost certainly a captured Kuiper Belt object. In other words, it's a large body like Pluto that just got too close to Neptune at some time in its past and was captured in orbit. Its orbit is retrograde. It's tilted. And Triton is a fascinating world. It has active cryovolcanoes. Voyager saw them. Even during Voyager's brief flyby, it was able to capture these glimpses of these huge columns of material erupting from spots on the south pole of Triton.

Heidi Hammel: What does that mean? Does it have an ocean under there like the other worlds do? Maybe, we don't know. The stuff that was coming out was black in nature, dark colored, so it's probably carbon-bearing materials. So fascinating, very intriguing. And then Neptune also has a really interesting interior structure, offset tilted, quasi-dipole magnetic field, lots of little small moons, chunky ring systems that are not whole. They're like arcs of rings, great stuff there.

Heidi Hammel: Uranus, also though is fascinating. This idea that Uranus has a bland, uninteresting atmosphere, we know is no longer true. We know that that is in part seasonal and in part due to the wavelengths that Voyager was looking at. To modern near-infrared cameras, it's going to be a fascinating planet with all kinds of belts, zones and clouds. So that's going to be very cool to see. It also has a very interesting moon system, five relatively large moons and then many, many small moons and a really dense packed ring moon system.

Heidi Hammel: So, Uranus is going to be great too. Either one of those will fundamentally change our understanding of planetary science because just like with every spacecraft, we are going to be inundated with all kinds of new information that does not fit into our current models and current paradigms. We're going to have to rethink a lot.

Heidi Hammel: And as I said before, this class of planet is pretty well represented in our studies of planets around other stars. Maybe the sub-Neptunes, smaller Neptunes could be more populous but there are still plenty of Neptunes, more Neptunes than there are Jupiters. So, I really love to see us go back with an orbiter and with a probe to sample the atmosphere itself to really get at the fundamental primordial building blocks that made those planets. You need a probe to do that.

Heidi Hammel: Some of these things you can't sample remotely. You have to have an in-situ measurement. That would be my dream. Orbiter with probes to either Neptune or Uranus. I think it would be a fantastic scientific return on investment.

Mat Kaplan: Take note, people conducting the decadal survey. I was going to bring up Triton if you didn't. We only have a couple of minutes left. Full disclosure, we of course mentioned that you are a vice president for science at AURA, but you're also vice president of the Board of Directors at The Planetary Society. And so, I'm going to guess that you have some strong feelings about our organization.

Heidi Hammel: That's right, Mat. I have been a supporter of The Planetary Society for many, many years. I give my time to the Board of Directors and as vice president because I believe in the mission of The Planetary Society. I share the values of The Planetary Society. I believe that we should be exploring our cosmos, that we should be learning our place in the cosmos. I believe that we should be trying to protect our planet from near-earth objects.

Heidi Hammel: Everything that we do in The Planetary Society is aligned with my own personal beliefs of why we should be studying the skies around us. And so, I'm a very proud supporter of The Planetary Society and I'm honored to be able to work with the team at headquarters, Bill Nye and Jen Vaughn and you and Casey, and formerly Emily Lakdawalla. I'm sorry, she's taking a hiatus.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, you and me both.

Heidi Hammel: ... tremendous asset to The Planetary Society ... And I hope that someday we may see her back in the fold again as after she explored some of the other things she's exploring.

Mat Kaplan: Heidi, thank you so much. We are honored and happy to have you as part of the organization, and wish you and AURA the greatest of continued success in exploring our cosmos and our own little solar neighborhood. It has been a great pleasure to talk with you and I hope we can do this again, maybe as we look out toward and get close to that planned launch of the James Webb Space Telescope now only about a year away.

Heidi Hammel: I'm looking forward to that, and I'm happy to come back and talk at any time. So let's get out there and dare I say it, change the world.

Mat Kaplan: Change the world. That's Heidi Hammel, vice president for science, Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy; otherwise known as AURA, and the vice president of the Board of Directors at The Planetary Society. I'll be right back with Bruce Betts in this week's What's Up.

Mat Kaplan: Time for What's Up on Planetary Radio. We are joined again by the chief scientist of The Planetary Society, that's Bruce Betts. What's up, Doc?

Mat Kaplan: At first, I thought why have I never said that? And then I thought, no, I think I did like probably 15, 16, 17 years ago. But it's been long enough that I think it's okay to use it again. So indeed, what's up, Doc?

Bruce Betts: Hunting wabbit.

Mat Kaplan: That qwazy wabbit.

Bruce Betts: Apologies to Mel Blanc. Mars, I cannot emphasize Mars enough. Did you pull out the telescope, Mat?

Mat Kaplan: I did. But because we're in the canyon and the canyon runs north to south, by the time Mars was high enough for me to see, it had clouded over. But I sure had a great view of Jupiter and the moon.

Bruce Betts: Jupiter and Saturn are still hanging out in that evening sky over in the west.

Mat Kaplan: And Saturn, how could I forget Saturn?

Bruce Betts: It has rings.

Mat Kaplan: Yes, I saw them.

Bruce Betts: Jupiter, super bright. Saturn, yellowish to its left. And if you go farther over the left in the earlier evening, in the east, you will find Mars. And it is almost at its brightest. In fact, it will be at its brightest on October 6th. That's when it is closest to the Earth, brightest for this time around, which is a pretty good opposition. So, it's as bright as Jupiter roughly right now. It also will be in opposition opposite side of the Earth from the sun on October 13th.

Bruce Betts: And don't forget, October 2nd and almost full moon, the same one, this is miraculous. The same one you saw by Jupiter is going to be by Mars. It's like it moves. And so full moon next to Mars on October 2nd, don't miss it. If you're up in the pre-dawn, Venus, super bright over in the east. Exciting.

Bruce Betts: On to this week in space history. Speaking of exciting, man, 1957, Sputnik launched, flew. 1958, this week, NASA was founded. Not unrelated.

Mat Kaplan: Deeply related.

Bruce Betts: On to a random space fact.

Mat Kaplan: That was snappy. That was like a little commercial jingle from the 1950s.

Bruce Betts: Nice. That was not too far off from what I was trying to do. I was trying to get you in the mood for comics.

Mat Kaplan: I love comics.

Bruce Betts: I've been a little obsessed, which is weird because this is not a very deep subject. But a little obsessed with Apollo call signs lately. They're so varied. I guess it's because the astronauts came up with them. Three Apollo spacecraft call signs were named after characters from the comics. Apollo 10 had Charlie Brown and Snoopy. Apollo 16 command module is called Casper after Casper the Friendly Ghost because the white suits worn by the astronauts looked kind of shapeless on the television screens at that time. Or at least that's the story.

Mat Kaplan: Children love him the most.

Bruce Betts: Casper the Friendly Ghost. Let's go on to the trivia contest. And I ask you, who is the only man that has a feature on Venus named after him? How did we do, Mat?

Mat Kaplan: People had such fun with this. Before I get to the winner, Mark Little in northern Ireland, one of our regulars, he got it right but he also said he's adding the Portuguese explorer, Ferdinand Magellan, for whom the Venus explorer Magellan probe was named because it's on Venus now. It was crashed into the planet, so it's a feature of Venus. Didn't think of that one, did you?

Bruce Betts: Oddly enough, no. But other trivia, did you know Magellan the spacecraft was named based on a Planetary Society led contest?

Mat Kaplan: I did not know that. It was before my time, so I had no idea. I'll be darned. Boy, we are everywhere.

Bruce Betts: You're just a twinkle in your parent's eyes.

Mat Kaplan: I think I was a bit more than that. I don't know if they ever twinkled anyway. Here's the answer hidden away in this week's submission from our poet laureate, Dave Fairchild, in Kansas. "Venus has mountains, Magellan has shown with radar to map out their height. And they may be coated with metal and stuff while hiding in sulfurous night. The tallest of these, above sea if you will, 11 kilometer stands. It's named for James Maxwell, a scientist and the only spot named for a man."

Bruce Betts: Nice.

Mat Kaplan: And correct, right?

Bruce Betts: Correctomundo. James Clerk Maxwell of Maxwell's equations. He also partied with solar system on occasion including Saturn's rings, figuring out they wouldn't be stable unless there were a bunch of particles.

Mat Kaplan: We heard from a whole bunch of people including [Norman Kissoon 00:52:51] and others that there were some discussion over this in the IAU and that they decided to stick with it because he basically laid out the basic principles in electromagnetism for radar, which is how his mountains were discovered. Great story.

Bruce Betts: Yeah. It was one of the features discovered before that wasn't discovered by spacecraft. And radar imaging is from earth-based radar as per the alpha and beta ratio. So I guess if there are guys named alpha or beta ... Never mind, you go back to what our listeners had to say.

Mat Kaplan: Here's something from Elijah Marshall in Australia. He says, "I tell my physics classes that when Maxwell was at Cambridge, he was told there was a compulsory 6:00 a.m. chapel service." "Aye, I suppose I could stay up that late," was his reply. He was Scottish, unlike me which is probably obvious. Here's our winner finally, and this is going to make some of our veteran non-winners crazy. Mike Zuber, as far as I can tell first time entry and he won.

Mat Kaplan: Mike Zuber in Pennsylvania who said, "Sure, it's James Maxwell." Mike, we're going to send you a Planetary Society Kick Asteroid, rubber asteroid for your trouble. Congratulations.

Bruce Betts: That would be great.

Mat Kaplan: I got more here, Pavel in Belarus. Name is actually mentioned in the episode in which you post this question because we were talking about Venus and the phosphine layer. One of the telescopes with which phosphine was found in the atmosphere of Venus is also named after James Clerk Maxwell. Is it Clerk or Clark? For some reason, I think it's pronounced Clark, but I could be wrong about that.

Bruce Betts: It could be pronounced Clark. It's spelled Clerk, so Clerk.

Mat Kaplan: William Malcolms in Pennsylvania also submitted Maxwell but first suggested, the great anthropologist, Margaret Mead, who has Mead crater named after her. At first, I thought, "No, he didn't get what we were after here," and then I remembered a visual joke in the Broadway musical, Hair, that I won't go into but somebody else out there gets it. I know, makes no sense to you at all, does it? But it does if you've seen the play.

Bruce Betts: I'd rather not.

Mat Kaplan: You may not want to. Yeah, it's not for primetime. And finally, this from Jean Lowin. With women all around him where goddesses abound, in the Montes of the Ishtar Terra, the [inaudible 00:55:27] eponym is found, this physics unifier who wrote poetry as well, Einstein stood upon his shoulders. His name, James Clerk Maxwell.

Bruce Betts: Nice.

Mat Kaplan: We're ready to move on.

Bruce Betts: I don't know if I mentioned that I was a little obsessed with Apollo call signs, but I am. So here's the question. What three Apollo spacecraft call signs were later used as the names of space shuttle orbiters? Go to planetary.org/radiocontest.

Mat Kaplan: This shouldn't be too hard to figure out, right? You have until the 7th. That will be Wednesday, October 7, at 8:00 a.m. Pacific time. We tend to follow that pattern pretty carefully here. We have a very interesting, a pretty special price, I would say because I heard from Matthew Serge Guy, or Guy. He's from France although he's in the UK now. Matthew heard about the only cat that ever went into space, Félicette, and actually survived the trip unlike some other animals we know about, had really kind of been ignored. It was set up on a French rocket, came back and I assumed lived happily ever after.

Mat Kaplan: Well, Matthew thought that Félicette should be honored. And so he came up with this idea of creating a bronze statue which is now in fact at the International Space University in Strasbourg, France. He put together a Kickstarter campaign to fund the creation of this because it's not cheap to make stuff out of bronze. But sure enough, it all worked out. It got 1,141 backers. You can check it out on Kickstarter. The campaign is still there along with a cool video.

Mat Kaplan: Well, he has some leftover rewards for people who pledged. And he said, "Would you guys like a poster of Félicette to give away on the trivia contest?" And I said, "May we?"

Bruce Betts: Wow. I didn't know you spoke French.

Mat Kaplan: Maybe I should have said, "Meow we?"

Bruce Betts: I didn't know you spoke cat.

Mat Kaplan: Neither one, really. There you go. We've got a great poster for you which will come from Matthew, and we are grateful to him. So, put a space cat on your wall, yeah, at least a poster of one.

Bruce Betts: Oh, wait, I don't want to wake the dogs. All right, everybody. Go out there. Look up the night sky and think about space litter boxes. Thank you, good night.

Mat Kaplan: Can you imagine a litter box in the ISS? I would probably cut the astronaut cadre in half because of the chance that you might end up sharing that space. Anyway, he's Bruce Betts. He is the "What's Up, Doc" that we talked to every week here on Planetary Radio.

Bruce Betts: (singing)

Mat Kaplan: Planetary Radio is produced by the Planetary Society in Pasadena, California. And, it's made possible by its members who celebrate first light, and all the light that reaches our world from the cosmos. Mark Hilverda is our associate producer, Josh Doyle composed our theme which is arranged, and performed by Peter Schlosser. Ad astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth