Planetary Radio • Jan 27, 2021

The Mysterious Case of Interstellar Visitor ‘Oumuamua

On This Episode

Avi Loeb

Frank B. Baird, Jr. Professor of Science at Harvard University

Bruce Betts

Chief Scientist / LightSail Program Manager for The Planetary Society

Mat Kaplan

Senior Communications Adviser and former Host of Planetary Radio for The Planetary Society

Could the first object shown to have originated outside our solar system be a light sail built by an alien civilization? That’s the very controversial hypothesis put forward by distinguished Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb in his new book Extraterrestrial. The book is about much more than ‘Oumuamua, and so is Avi’s conversation with Mat Kaplan. Bill Nye pays tribute to a fallen member of The Planetary Society’s space family, and the biggest coincidence in the history of Planetary Radio surfaces during What’s Up.

Related Links

- Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth

- Planetary Radio: A Visitor from the Stars

- Planetfest ’21: To Mars and Back Again

- Register for the 1 February 2021 webinar: U.S.-U.A.E. Business Council presents Her Excellency Sarah Al Amiri in conversation with Mat Kaplan

- The Downlink

Trivia Contest

This week's prizes:

The brand new and beautiful Planetfest ’21 t-shirt!

This week's question:

What person’s name has to do with both Earth’s and Mars’ prime meridian?

To submit your answer:

Complete the contest entry form at https://www.planetary.org/radiocontest or write to us at [email protected] no later than Wednesday, February 3rd at 8am Pacific Time. Be sure to include your name and mailing address.

Last week's question:

What did Galileo want to name the Galilean moons after?

Winner:

The winner will be revealed next week.

Question from the 13 January space trivia contest:

Imagine if the Huygens probe had landed on Earth at the same latitude and longitude at which it landed on Titan. It would have come down in an ocean. Name one of the islands or island groups closest to its splashdown.

Answer:

If the Huygens probe to Titan had landed on Earth at the same latitude and longitude it would have come down in the western Pacific Ocean not far from several Polynesian islands and island systems including the Solomons.

Transcript

Mat Kaplan: Avi Loeb says we may have had an interstellar visitor from another civilization. That's this week on Planetary Radio. Welcome. I'm Mat Kaplan of The Planetary Society, with more of the human adventure across our solar system and beyond. You may have heard of Professor Lobe's new book, Extraterrestrial. In it, he presents his theory that the best explanation for that strange object called 'Oumuamua is that it was neither a natural asteroid or comet, but a light sail. One launched by a civilization from another star system.

Mat Kaplan: As you might imagine, this has generated a lot of controversy. Even if you find his theory hard to accept, I think you will agree that our conversation this week is fascinating. The greatest coincidence in the history of Planetary Radio will also come to light in this week's What's Up with Bruce Betts. And we'll hear a special tribute from Bill Nye in a couple of minutes.

Mat Kaplan: First though, a couple of special announcements. Registration is open for Planetfest '21: To Mars and Back Again. It's our virtual celebration of the three space craft about to arrive at the red planet. We'll have scores of certified Martians for you to enjoy, including Bill, of course. You can check out the full program at planetary.org/planetfest21.

Mat Kaplan: One of those missions now approaching Mars is the Hope orbiter from the United Arab Emirates. I've been asked by the US-UAE business council to host another conversation, with the mission's science lead, Sarah Al Amiri. Sarah is now also state minister for advanced sciences in the UAE. We'll talk with each in a live webinar on Monday February 1st at 9:00 AM Eastern, 2:00 PM UTC. Registration is free and we've got the link on this week's show page, planetart.org/radio. I hope you can join us for both of these events.

Mat Kaplan: Just time for one news item from the January 22nd edition of the Downlink, our weekly newsletter. Planetfest '21 will climax on February 18th, as the Perseverance Mars rover lands. You can simulate all seven minutes of terror in NASA's Eyes on the Solar System program. We've got the link at planetary.org/downlink.

Mat Kaplan: The Planetary Society lost a dear member of our space family a few days ago. I asked Society CEO, Bill Nye to help us remember and pay tribute to Wally Hooser. Bill you had many more opportunities to talk with Wally Hooser than I did, but I could say that every conversation I had with him was absolutely delightful.

Bill Nye: The guy was a joy, he was a joy. He was guy that had faced death for decades with his crazy autoimmune intestinal thing, and he just did not take life for granted. He was really something. But the big thing you know, he was a radiologist. He was a medical professional, but he has passion for planetary exploration. He talked all the time about living on another world, knowing what other worlds are like. What it must be like out there. There must be somebody else beyond our solar system, and are those entities wondering about us, and so on. He was a charming, passionate guy who loved science.

Mat Kaplan: And I think in this, not a scientist, not an engineer, he represented so many of the members of The Planetary Society, including me.

Bill Nye: Well, you say not a scientist, he was a radiologist. He relied on nuclear medicine, but I know what you mean, he was not a full-time research scientist [inaudible 00:03:47] other people on the board of directors of The Planetary Society. But he had a deep appreciation for the scientific method, discovery. And he loved the big fundamental questions: are we alone? Where did we all come from? He loved those questions.

Mat Kaplan: I'm glad that you were able to take a couple of minutes to pay tribute to Wally, and we will miss him.

Bill Nye: Oh Mat, I miss the guy everyday. And everybody out there, Planetary Society members, Wally transformed the organization. He joined the board in, let me think, 2012. He apparently came from a family that had lost their fortune. He asked us, "When you guys ran around in the summer, did you have shoes?"

Mat Kaplan: What?

Bill Nye: He apparently grew up not wearing shoes in the summer to save money. And so they wouldn't have to replace kids' shoes as the kids grew. He just did not take it for granted, and he brought this passion to the board and he really encouraged us to focus on fund-raising, because people want to support an organization like ours. People were passionate about understanding the cosmos in [inaudible 00:04:59] want to support the planetary side. So let's engage them. This was Wally's vision. I miss the guy every day, Mat. He was a great guy.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, Bill.

Bill Nye: Thank you, Matt. Carry on.

Mat Kaplan: Bill Nye is the CEO of The Planetary Society. Let me tell you a little bit about our special guest. It's more important than usual that you hear all of this upfront. Because what Abraham, or Avi Loeb has proposed is on the face of it, like the sort of thing that is found in the dark corners of the net, and that we would never cover on planetary radio. Avi is the Frank B. Baird Jr, Professor of Science at Harvard University, where he chaired the Astronomy Department, is the founding director of Harvard's Black Hole Initiative, and director of the Institute for Theory and Computation within the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Mat Kaplan: He also chairs the Advisory Committee for the breakthrough Starshot Initiative, and serves as the science theory director for all initiatives of the Breakthrough Prize Foundation. He chairs the board on physics and astronomy of the National Academies. Avi has authored four books and over 700 scientific papers, and is an elected Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Physical Society and the International Academy of Astronautics. Now, Avi would tell you that none of these credentials mean a thing. Only the evidence, the data gathered about something, is worth considering.

Mat Kaplan: What he has concluded from the data surrounding 'Oumuamua is at odds with what many other astronomers and physicists believe. Many have not been shy about saying so. Avi has now written Extraterrestrial, The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth. It is about much, much more than 'Oumuamua. And it led to the wide ranging conversation we had a few days ago. Professor Loeb, Avi, welcome to Planetary Radio and congratulations on the publication of Extraterrestrial this week.

Avi Loeb: Thanks for having me.

Mat Kaplan: You have, I'm sure you know, received a good deal of criticism, even ridicule, ever since you and Shmuel Bialy published your 2018 paper about 'Oumuamua in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. You even got a mention, that I heard by chance, from Stephen Colbert a few nights ago. I suspect that few, possibly none of these critics have read Extraterrestrial. It's about so much more than your thoughts about 'Oumuamua, and I enjoyed it tremendously.

Avi Loeb: Thank you.

Mat Kaplan: You say in the book, and this is a quote, "I believe that my life's unusual path prepared me for my encounter with 'Oumuamua." And you did have an unusual childhood for someone who would become, later, a leading astrophysicist. Can you explain why a goat farm in Israel's Negev desert felt like a comfortable place to write about reaching the stars with solar sail, or light sail technology? By the way, thanks for including an image of The Planetary Society's light sail in the book.

Avi Loeb: Yes, in fact, nature was always much more appealing to me than people. Even though people can be regarded as part of nature, they often behave in a way that deviates from the pleasant existence of nature. I grew up on a farm, I used to collect eggs every afternoon, we had chickens. I used to drive the tractor to the hills of the village and read philosophy books, I was mostly interested in the deepest questions we have. Then circumstances brought me into astrophysics. I didn't know the vocabulary of astrophysics when I got to a postdoctoral long-term fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton. Took me a few years to learn that.

Avi Loeb: Eventually, I ended up with a 10-year-old appointment of a professor at Harvard. A decade later, the chair of the Harvard Astronomy Department for nine years. But my upbringing was quite different than a typical Harvard professor, especially different than an astronomer. Perhaps that explains why I do not pay too much attention to how many likes I get on Twitter. What I really care about is whether the evidence is telling us something new or not. If someone would show me a photograph of 'Oumuamua that would indicate that it's a rock, or demonstrate through a simple model and explanation, for all the weird facts that it exhibited, I would accept that.

Avi Loeb: I have no problem with that. I pay attention to evidence. Just like basketball coaches often say, keep your eyes on the ball, not on the audience. I don't care what people say. It really is irrelevant. I don't care also about all the titles that they have, all the leadership titles. I just want to figure out what the world is, just like a kid, the way I grew up. I'm curious about the world and I want to figure it out. I'm willing to entertain a possibility that others are not. Frankly, I don't fully understand that. And some of my critics, I'm willing to bet, deep down I'm sure that many of my critics are very intrigued by the possibility that 'Oumuamua was a technological relic.

Mat Kaplan: I promise, you and the audience, we are going to talk more about this odd object itself, but I'm going to get into there a little bit gradually. I hope you and the audience won't mind. I'm really proud to have been one of the people who helped create Yuri's Night, the annual celebration of Yuri Gagarin becoming the first human in space. I'm hoping that you can say something about why you were on stage with Freeman Dyson and Stephen Hawking for the 2016 celebration of Yuri's Night.

Avi Loeb: Yes, the story starts in May 2015, when Yuri Milner, an entrepreneur from Silicon Valley, came out of a black limousine, next to the Center for Astrophysics, where my office is. Entered my office and said, "Avi, would you be willing to lead a project to visit the nearest star within our lifetime?" Now, Yuri and me have almost exactly the same age. And so what it meant is, within two decades. I said, "Sure, that sounds fascinating." Then I told him, "It will take me six months to figure out what technology could do that." Of course, I thought about it with my students in postdocs.

Avi Loeb: After six months, I got a phone call. I was actually in Israel at the time, at a hotel in Tel Aviv, and on the way out of the hotel room to a weekend in the Negev, to visit a goat farm, as you mentioned. Because that's what my wife wanted us to do that weekend. And then I get a phone call from Pete Warden, who was the executive director of the Breakthrough Foundation, the assistant to Yuri. He told me that Yuri would like to know the answer, what technology can we use? I said, "Okay, I'll make the presentation."

Avi Loeb: Then I got to the goat farm, there was no internet connectivity anywhere, except for the office. So at 6:00 AM the following morning, I was sitting with my back to the office door so that I can get reception, and starting to work on the presentation that I'll make. And looking at the goats that were just born the day before in front of me. It was surreal, because contemplating the first visit to the nearest star, while looking at goats in the southern part of Israel was not the thing that the goat farm or owner would have ever imagined.

Avi Loeb: And then I went to Yuri's home two weeks later in Palo Alto and presented it and he got excited. So we then worked for about four months, back and forth, discussing all the possible pitfalls, all the possible risks for such a project. And then came out with the announcement. Stephen Hawking also came for that announcement, and a few weeks later, we also inaugurated the Black Hole Initiative at Harvard, that I'm the founding director of. Stephen Hawking came for Passover dinner at my home, which was a very memorable event that I also mention in the book.

Mat Kaplan: And your conclusion, of course, and we have talked about Breakthrough Starshot several times previously on the show, with some of the people that you've just mentioned. Was that, a solar or a light sail, was a practical way to get among the stars, at least if a limited number of light years are involved. Am I right?

Avi Loeb: Yeah. The nearest star is four light years away, Proxima Centauri. If you want to reach it within two decades, the spacecraft needs to be launched to about a fifth of the speed of light. What else can launch a spacecraft to such a high speed, than light itself? Because only light can chase the spacecraft and continue to accelerate it to that speed. And the concept is a light sail, which is similar to the sail on a boat, which is pushed by wind. Except here, it's pushed by reflecting light. This concept was entertained about a century ago. And then after the laser was discovered, Robert Forward suggested that maybe one can reach high speeds using a laser that is collimated on a sail.

Avi Loeb: And our concept is pretty much along these lines. Except, the reason it's practical now is because lasers are much more powerful and they are at much lower costs right now. Also the miniaturization of electronics reached a high level due to cell phone technology. We can basically pack a camera, a navigation device, a communication device within a spacecraft that weighs only a gram, and then attach it to a sail. And then focus 100 gigawatt of laser beam on the sail that has roughly the size of a person. Within a few minutes, if the sail is in space, it could reach a fifth of the speed of light across a distance of five times the distance to the moon. This is pretty much the concept.

Mat Kaplan: There is a method to my madness here. Looking back now to 2017 when astronomers discovered that interstellar visitor that we now know as 'Oumuamua, when did you begin to suspect that we had found more than a typical asteroid or comet?

Avi Loeb: Well it took me, I would say, about half a year. Because when it was discovered, there wasn't any data on it that indicates that it's weird. But as time went on, more and more data was collected. At some point, it crossed the threshold. At some point it was the straw that broke the camel's back in a way, for me. I realized, look, there are so many anomalies about this object, definitely doesn't look like a comet. Because it didn't have a cometary tail. In fact, the Spitzer Space Telescope looked very deeply and couldn't see any carbon-based molecules surrounding it. So that puts a very tight limit. The object, on the other hand, showed an excess push away from the sun. And the force declined inversely with distance squared.

Avi Loeb: In principle, such a push can be provided by cometary tail through the rocket effect. But there was no cometary tail. So the only thing I could think of was reflected sunlight, which drops also inversely with distance squared. Moreover, it was fully consistent with the data, if the object was a sail, a light sail. So we wrote this paper in a highly respected scientific journal, Astrophysical Journal Letters. The paper was accepted for publication within a few days. And then the media caught the story and it became viral. The unfortunate aspect of all of this, and I discuss it in the book, is that the scientific community is not ready to discuss technological signatures.

Avi Loeb: I can illustrate it with one example. I was contacted by an astronomer that said in the next American Astronomical Society meeting, let's arrange a debate, a great debate, to celebrate 100 years to the Great Debate between Harlow Shapley and Curtis, about the nature of the nebulae. And Shapley, who was the director of the Harvard College Observatory, held the wrong opinion that nebulae are part of the Milky Way galaxy. But there was a great debate about it. So this colleague, from a different institution, wanted to establish a debate about the nature of 'Oumuamua. All the debaters agreed to participate including the moderator, and everyone was ready and excited about it.

Avi Loeb: But then the organizing committee of the conference gave it the red light. Basically said, it will attract too much attention. We don't want to discuss this subject. Now, the problem is two-fold. First, we now know from Kepler satellite data that half of the stars in the Milky Way galaxy that look like the sun, have a planet the size of the earth, roughly at the same separation. And that, to me, implies that if you arrange for similar circumstances, you should get similar outcomes.

Avi Loeb: So we probably are not alone. That should be the mainstream view. The default view should be that we are not special or unique. That's a sense of modesty. And we should show it. Why should we assume that everything we have here is unique and special? My daughters, when they were infants, thought that they're special and unique. But when they went to the kindergarten, they realized that there are many others that have qualities even better than theirs. So the only way for us to mature would be to search for evidence for others.

Avi Loeb: That, to me, sounds like 180 degrees away from where the current scientific community is. It's not just a small nuance, it's a complete opposite, the way things are treated right now. But there is the bigger context, which is that the public is extremely interested in this question. And the public funds science and the scientists have the instruments to detect anomalies related to technological signatures. So how can they put a taboo on discussing this subject? How can they starve it from any funding and then bully or ridicule anyone that considers that possibility? It's like stepping on the grass and then saying, look, it doesn't grow.

Mat Kaplan: And this is a good deal of what the book is about as well. I have some questions for you about that. Harvard professor, Avi Loeb, has much more to share with us after a break.

Bill Nye: Greetings, Bill Nye here. Saturday, Sunday, a fleet of space craft, including NASA's Perseverance rover is arriving at Mars. Join our live online celebration, Planetfest '21 is February 13th and 14th. I'll be there with explorers, including Jim Bell, Katie Mack, author of The Martian and the [inaudible 00:20:14] NASA JPL chief engineer Rob Manning, and my old friend Phil Plait, the bad astronomer. Get your tickets at planetary.org/planetfest21. We are going to Mars!

Bill Nye: Mat, was that too much? I got into it there.

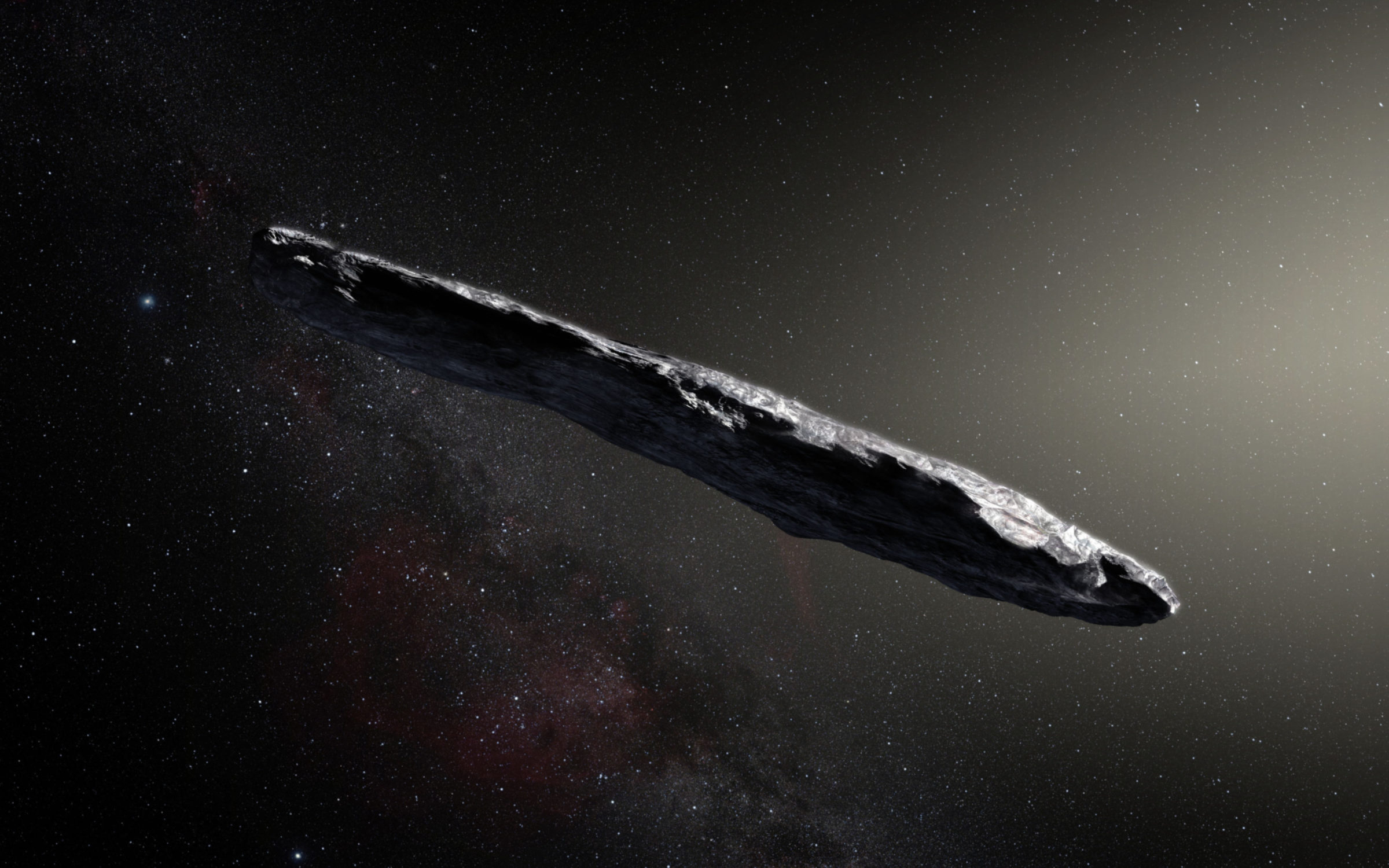

Mat Kaplan: No, you nailed it boss. To return to 'Oumuamua, and it's a shame that we can't physically return to it, it's far too far away and far too fast now. You've no doubt seen the famous artist conception of the object, that depicts it as cigar-shaped, for lack of a better comparison. I'm sure you wish that that was a different sort of visualization.

Avi Loeb: Yes, because there is actually a paper published in December 2019, by Sergei [Marchenko 00:21:01], from the UK, that they analyzed the light curve, the amount of reflected light by 'Oumuamua, as a function of time, as it was tumbling, as it was spinning. They demonstrated at a 91% confidence level, that it must have been a flat object, disc-like object, pancake-like, not cigar-shaped, the way it was depicted in this cartoon. Of course, we don't have an image. But it must have been an extreme geometry, because the brightness varied by a factor of 10. That means that the area projected on the sky of the object was changing by a factor of 10.

Avi Loeb: Imagine a piece of paper tumbling in the wind, and the area that you see in front of you changing by a factor of 10. That's a lot, and it means that the object must have been very long compared to its projected width on the sky by by at least a factor of 10.

Mat Kaplan: A very thin disc, is what do you think answers these observations best?

Avi Loeb: Yes. And most likely, something that is as thin as needed for it to feel this extra push from reflecting sunlight, so similar to a sail. Now, it could be that it's not something that was designed to be a sail, it could be, for example, a layer, a surface layer of a bigger object like a spaceship that was torn apart. But at any event, in my mind, it has so many anomalies. There are six of them that I detail in the book, and each of them makes it something that we have never seen before. Now, some astronomers, mainstream astronomers try to explain those anomalies. Most of the mainstream astronomers simply ignore the anomalies, or say, I can explain one of the anomalies, and do not even refer to the others. And they say business as usual.

Avi Loeb: But anyone that attempted to explain came up with something that we have never seen before, like a hydrogen iceberg, frozen hydrogen, which would explain why we don't see the cometary tail, because it's hydrogen that is transparent. But on the other hand, such an object would evaporate very quickly along its journey by absorbing starlight. I wrote a paper about it with Thiem Hoang, so it wouldn't survive the journey.

Avi Loeb: And then there was another suggestion, a collection of dust particles, sort of a dust bunny, a big porous object, a cloud of dust, 100 times less dense than air. As a result, it gets pushed, it's so light, it's so porous, that it gets pushed by reflecting sunlight. Again, the problem is would something like that maintain its integrity, and be able to survive the journey of millions of years through interstellar space?

Avi Loeb: To me, it sounds much more likely that if it's something that we have never seen before, it's something different. It's an artificial object. And besides, I'm not claiming that I have 100% proof that it is, but I'm just saying, let's discuss it as a viable option and search for the next one that shows anomalies of this type. People are upset about even mentioning this possibility.

Mat Kaplan: Here's what may be a dumb question and in some ways, I hope it is. If 'Oumuamua is an interstellar light sail, why isn't it going faster? I mean, as you said, the target for Breakthrough Starshot is 0.2c, 20% of the speed of light. 'Oumuamua was fast, but it's certainly not that fast.

Avi Loeb: Right. That may relate to a selection effect related to what we were looking for. So Pan-STARRS is looking for Near-Earth Objects.

Mat Kaplan: The Pan-STARRS astronomical survey, that is surfing the entire sky-

Avi Loeb: Yeah, the [crosstalk 00:24:44] that discovered this object, 'Oumuamua, was intended to survey for Near-Earth Objects. And that's a task that Congress gave to NASA, to find 90% of all the objects larger than 140 meters, a few 100 feet. Which is roughly the size of 'Oumuamua. So Pan-STARRS was designed to find rocks from within the solar system moving at 10s of kilometers per second in the vicinity of the earth. Given that charter, it would find only objects that move at 10s of kilometers per second of that size or above near the earth. That's what it will find. That's what it was designed to find.

Avi Loeb: Suppose an object that is one meter in size, flies at a fifth speed of light through the solar system, do you think that Pan-STARRS would detect it? No. The astronomers would see something moving so fast, they would say, wow, that must be just noise in the detector, or they would not even notice it. Because it's too small, it doesn't reflect enough sunlight. My point is, you see what you are expecting. If you're not expecting to find wonderful things, you will never discover them. Given the capabilities of Pan-STARRS, the survey, it could find objects of size larger than 100 meters, that move at 10s of kilometers... And that's what 'Oumuamua was. No surprise here.

Avi Loeb: Now, 'Oumuamua, indeed, may not represent a functional device. But it could still be... It's just like going along the beach and most of the time you see natural rocks and seashells. But every now and then you stumble across a plastic bottle. And most of these plastic bottles that you find on the beach that indicate an artificial origin, most of them are not functional anymore. In the context of space, that would be space junk. There might be a lot of junk out there, who knows?

Mat Kaplan: Throughout this book, Extraterrestrial, you keep coming back to the absolute necessity of data, of evidence, to base theory on. And you say that where there is no data, it is, well, I don't know, irresponsible to theorize? And you were applying this to some of the theories regarding cosmology, including string theory, that there really is not much evidence for. On the other hand, you're not a big fan of something one of the planetary societies' founders, Carl Sagan said, extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof. Where do you find a middle ground there?

Avi Loeb: Well, my point is, in physics, the only way for us to learn something new, is to discover anomalies. And anomalies mean, something doesn't quite line up with what you expected. There was a seminar about 'Oumuamua at Harvard. And when I left the room together with a colleague who worked on solar system rocks for his entire career, decades, he said to me, "This object is so weird, I wish it never existed." Foe me, that's appalling to hear that, because a scientist should always be ready, and in fact, most excited about things that don't line up with what he or she expected.

Avi Loeb: Because we discover new things, it's nature's way of educating us. Telling us, look, you have to learn something new here. If we are not willing, if it bothers us because it moves us out of our comfort zone, that's pretty bad. A good scientist should not feel the need to always stay within the comfort zone. If you look at quantum mechanics, that was not within the comfort zone of Albert Einstein, the best scientist that we had in the 20th century. And he claimed that it cannot have spooky action at a distance. But it does, it does! We did experiments afterwards, he was wrong. And the fact that it didn't line up with his comfort zone doesn't matter. Reality is whatever it is, irrespective of how humans respond to it.

Avi Loeb: That's why I don't care about the likes on Twitter, I care about the evidence. My point is in this case, there is evidence that indicates something that we have never seen before. And on that, everyone that tried to analyze the data and explain it, even with natural origins, would agree with me, that it's nothing that we have seen before. Because these are the papers that were published, they were all saying that. Except for a group of people that decided to come together and write a review for Nature Magazine, just saying it's natural, and that's it, period. They were trying to establish their view by authority.

Avi Loeb: Why would they need a large number of collection of authors to do that? I mean, it reminds me of the story about a book written in 1930s, that argued that Einstein's theory must be wrong. Einstein's theory of relativity. And there were 30, or more than 30 scientists signed on the book. And then when Einstein was asked about it, he said, "Why do you need 30 scientists to be signed on such a book? If if there is a simple argument, one would be enough." The reason is that people want to establish their authority. There are experts on a subject, and they will tell you what nature is supposed to be, and you are supposed to listen. To me, that's very similar to what the philosophers in the days of Galileo did.

Mat Kaplan: You remind me of something you quote in the book, an unnamed physicist that you heard at a conference who, while talking about some out there theory apparently said, "These ideas must be true, even without experimental tests to support them, because thousands of physicists believe in them. It is difficult to imagine that such a large community of mathematically gifted scientists could be wrong."

Avi Loeb: Well, that's exactly the other part of my frustration, which is, at the same time, that the discussion on technological signatures is suppressed. At the same time, there is a large chunk of the theoretical physics community working on ideas that not only were not tested, like extra dimensions, supersymmetry, string theory, the multiverse. Supersymmetry, for example, was tested by the Large Hadron Collider, which didn't find it. So all the natural parameters of supersymmetry have to be revised. And people gave awards and honors and respected each other, and felt quite as if they're carrying the torch of physics forward by discussing these ideas as part of the mainstream. And they're still doing that.

Avi Loeb: In most of those cases, like extra dimensions, the multiverse, string theory, if you think about the next decade, two or more, there is no clear path to testing them experimentally. On the one hand, you have this culture of physicists that claim not only that they work on something that cannot be tested, they work also on anti-de Sitter space, which is not our spacetime, the one that we live in, it's some other spacetime where they can actually solve their equations. And they say, let's solve our equations there. It's just like, you losing keys and saying, I can only search my keys under the lamppost.

Avi Loeb: So they just search their keys on the different spacetime that doesn't represent ours. And then they do intellectual gymnastics. The only way I can understand it, is that they want to convince others that they're smart. They're gifted mathematically. And that's the way that the job market allocates positions and honors and so forth, to those people. So you can create a culture where you're working on something that has no relevance to nature, no clear path to describing experiments, but nevertheless, you can impress your colleagues and get a reward for doing that. To me, that's a distortion of the purpose of physics, which is to describe nature.

Avi Loeb: Nature may be simple, it may not require mathematical sophistication. If you look back at Aristotle's idea of the sphere surrounding us as the model for the universe, that was very sophisticated, very clever, he was a very wise person, but he was wrong. The fact that you can reach great heights in mathematical sophistication, doesn't mean... Nature may be quite simple. It is our duty as physicists to understand the world, not to engage in mathematical gymnastics. That is my second frustration, that you find the mainstream in theoretical physics endorsing these discussions. Whereas something to do with evidence, like the possible existence of a technological civilization, is being suppressed and pushed to the sidelines.

Mat Kaplan: Here is another quote from you in the book, Extraterrestrial. It's, I think, right in line with what you're saying, "Physics is not a recreational activity intended to make us feel good about ourselves. Physics is a dialogue with nature, not a monologue. We are supposed to have skin in the game and make testable predictions. This requires that scientists put themselves at risk of error." I take it that this is one of those risks that you're not concerned about in your own life.

Avi Loeb: That's right. Because I look at the history of physics. So Albert Einstein, once again, in the last decade of his career, he was supposed to be the most experienced. But he made three mistakes. He argued that black holes don't exist, gravitational waves do not exist and quantum mechanics doesn't have spooky action at a distance. He was wrong on all three. What is the lesson from that? If you work on the frontiers, you could be wrong. I mean, that's part of the business, of your job description. If you want to discover something new, you're taking a new path into the unknown and you can never be sure that you're right.

Avi Loeb: You're doing your best, of course, you're following what is known, but sometimes you're wrong. And you should accept that. If you are after preserving your image, then you will just repeat things that were already found by others or by yourself, and you will maintain it very respectable image. You will get honors and awards, but what's the point? You will be very boring also, because you will keep repeating things that are already known. If you want to discover something new, you will take risks. And by the way, the commercial sector realizes that there are parts of Google and SpaceX and Blue Origin and many other endeavors, including Facebook, that have blue sky research.

Avi Loeb: They take risks, because they realize that one of them might be successful, and then increase their profits significantly. If the commercial sector is doing that, how can the academic world be more conservative, and basically put a taboo on the possibility of discovering technological signatures, if we have the telescopes to do so?

Mat Kaplan: We already mentioned Freeman Dyson, and his appearance with you on stage for Breakthrough Starshot. I know he was a mentor to you, how did his approach to science help shape your own?

Avi Loeb: Well, he was actually the first person I met when I went to visit Princeton, the Institute for Advanced Study. The administrator there said, "Everyone is very busy." And she said, "Okay, there is only one person that might have time to speak with you. And that's Freeman Dyson." So I went to his office and then he introduced me to John Baker. At that time, I knew his name from books on quantum electrodynamics, and I really admired him. But over the years, I appreciated his brilliant mind and independence of mind, and sense of innovation. And good book writing skills. It really served as a role model for me, because I enjoy thinking independently of others, that's why I don't have any footprint on social media.

Avi Loeb: My wife asked me not to have when we got married, and I kept my word. I actually told that to Lex Friedman, when he interviewed me on a podcast a couple of weeks ago. His response was, I need to get married. Another anecdote about social media, I asked the students in my class, suppose a spaceship would land and ask you to get into it, would you do it, given the risks? To my surprise, all of them said, yes, but under one condition. That they will be able to share their experience on social media. I found that very surprising, because I would just go in for the experience, I don't care how many people share my experience. And the younger generation is all about sharing.

Mat Kaplan: I wonder how you feel, in general, about the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, which Yuri Milner has also done so much to support lately, and how we've conducted it so far.

Avi Loeb: I would like to bring it to the mainstream. I think it deserves to be in the mainstream of astronomy, not only because it's not a speculative notion that we are not unique and special, but also because the public is so interested. Some people say, oh, yeah, science should be elevated on a pedestal. Because there are all these unsubstantiated reports about unidentified flying objects and stuff like that. My response to that is in the Middle Ages, there were all kinds of false statements about the human body. People thought, in the dark ages, that it has some magical powers, or the soul, and you shouldn't dissect the human body, you should have an operation. Okay, and suppose scientists would say, we don't want to discuss this subject of the human body, because there is all this nonsense being said about it. Would that make any sense?I mean, we wouldn't have modern medicine.

Avi Loeb: My view is that science should address whatever it can, with a scientific methodology. Especially a question that is of so much concern to the to the public, which is, are we alone? I wrote not only this popular level book that we are discussing, that will come out...

Mat Kaplan: This week, as people hear this, right.

Avi Loeb: I have also a textbook of 870 pages, for a scientific audience, laying the foundation for the search for life, both microbial life and technological civilizations. This is a book written with my former postdoc [inaudible 00:39:38] that will come out from Harvard University Press at the end of June 2021, in half a year.

Mat Kaplan: You mention, in your discussion of [SETI 00:39:49], a term for an object that I had never heard, green dwarfs. What do you mean?

Avi Loeb: As you reduce the mass of a star, the surface temperature goes down. For example, the nearest star to us is Proxima Centauri, it has 12% of the mass of the Sun, and roughly half the surface temperature. But if you continue to consider objects smaller and smaller, and by the way, the dwarf stars are the most common in the Milky Way. Sun is an unusual star, it's not the most common one. The most common is like Proxima, and it's a red dwarf. And there is a habitable planet next week, Proxima B, which is 20 times closer. So even though the star is faint, that planet could have liquid water on the surface. But the light emitted by Proxima Centauri is mostly in the infrared. It's red light. And the grass on Proxima B, if there is grass, if there is life there, the grass is not green, it's dark red.

Avi Loeb: This may explain, if most of the civilizations form near dwarf stars, and they have infrared eyes, why would they ever come for a vacation on earth? All the interstellar travel agencies would never advertise earth, because it has green grass. They want to see dark red grass, that's the view that is enjoyable for them. In order for us to entice a civilization near a dwarf star to come here, we should go there and share water-based drink with them. And try to convince them to come over.

Mat Kaplan: I hope that they would show curiosity about systems that are based on a different visible spectrum than their own. I want to ask you this last two-part question. Do you think we are likely to see another visitor to our solar neighborhood like 'Oumuamua? If so, how should we prepare?

Avi Loeb: I think we're very likely, because it took 'Oumuamua more than 10,000 years to cross the Oort cloud of the solar system. And so there must be many more. I mean, we detected it over a few years. So we had a very short window over which we observed and were sensitive to such objects. Therefore there should be many more of them. That means good news, that the Vera Rubin observatory that will start the operation in about three years, should be able to detect one such object every month. If 'Oumuamua was a member of a population of objects on random trajectories through the solar system. And that means we will find many more of the same.

Avi Loeb: My point is if we see an object approaching us, we don't need to chase it, we can just send a camera that will cross its path. And we can take a close-up photo. A photograph is worth 1,000 words.

Mat Kaplan: Avi before I say goodbye, there is a paragraph toward the beginning of the book, Extraterrestrial. I wonder if you would read it for us. It starts, when I look out into the cosmos...

Avi Loeb: When I look out into the cosmos, I'm awed by the order, by the fact that the laws of nature that we find here on Earth, seem to apply out to the very edges of the universe. For a long time since well before the arrival 'Oumuamua, I have harbored a corollary thought. The ubiquity of these natural laws suggest that if there is intelligent life elsewhere, it will almost certainly include beings who recognize these ubiquitous laws, and who are eager to go where the evidence leads, excited to theorize, gather data, test the theory, refind and retest. And eventually, just as humankind has done to explore.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you, Avi, I think that is a wonderful way for us to end this conversation about your new book, Extraterrestrial, The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth. It has just been published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, and is available from all the usual places. And if you stay tuned, you might get a chance to win it, when we go to this week's space trivia question with Bruce Betts. Avi, best of luck with the book and I hope we can talk again before long.

Avi Loeb: Thank you so much

Mat Kaplan: Time for What's Up on planetary radio. Once again, we are joined by the chief scientist of The Planetary Society, I almost said Mr, Dr. Bruce Betts. What, I don't know why almost made that slip. Anyway, he's here, he's here to tell us about the night sky. And tell us where Huygens would have landed on earth if it had been headed to earth. Welcome back.

Bruce Betts: Thank you, good to be back.

Mat Kaplan: What's up?

Bruce Betts: Mars is up. It's looking bright still and reddish in the evening sky up in the south. I've chased the other planets away. So now you can really focus on the stars. Orion looking beautiful in the evening east. And it's a good opportunity to find the Winter Hexagon, made up, not surprisingly, of six bright stars, including one in Orion. I suggest looking that up, or turn to the right page in Bruce Betts' Astronomy For Kids. But you can also just look it up online, Winter Hexagon and learn to identify bright stars and their constellations.

Mat Kaplan: Good book, by the way.

Bruce Betts: Hey, thanks. We move on to this week in space history. It is our week of remembrance of the honored dead. All of the deaths in the NASA program and involving spacecraft, occurred during this week. So 1967, three Apollo astronauts, 1986, the seven Challenger astronauts and 2003, the seven Columbia astronauts. So we think back and honor them this week.

Mat Kaplan: We do indeed.

Bruce Betts: On to random space fact. I thought I'd talk about longitude because I know we're going to be talking about it. The location of the Prime Meridian, which is where you define longitude equals zero, is arbitrary, basically, for all the planets and many of the other objects: asteroids, comets and the like, in the solar system. And many of those moons, but lots of the moons are synchronously locked to their parent bodies. So they always face the same side to that parent body. In which case longitude zero, the Prime Meridian is defined as the points facing the planet, or the other body in the case of some objects.

Mat Kaplan: Read Longitude, by our friend Dava Sobel, because it's a great book about how you figure out where your longitude is, what your longitude is, on whatever world you happen to be sailing across. That's two books I've recommended this show.

Bruce Betts: Didn't the sailing ships of the 15, 1400s, they carried GPS, right?

Mat Kaplan: Oh, yeah. Yeah, they had it, but they had to have backup.

Bruce Betts: Oh, okay. Otherwise I was thinking, that's a short book. All right, we move on to the trivia contest. Speaking of such things, I said, if the Huygens probe landed on earth at the same, so to speak, latitude and longitude, it landed on Titan, it would have landed in an ocean. In that case, name one of the closest islands or island groups to its splashdown. How'd we do Mat?

Mat Kaplan: People had a good time with this.

Bruce Betts: Oh, good.

Mat Kaplan: Although not everybody got it right, possibly because of this confusion about measuring longitude on earth and on Titan, which we'll get to in a moment. But the answer is packed away neatly here in our [inaudible 00:47:47][de Fairchild's 00:47:48] response, Titan's, the place where the Huygens probe landed, but put those coordinates here on the earth, Santa Cruz islands. And also Duff islands are in the vicinity for what it's worth. They're in the ocean where fishes are swimming, the Solomon Islands are spread in the sun. Much better place to retire than Titan, at least when your space faring days are all done.

Bruce Betts: Nailed it!

Mat Kaplan: And here's the winner who nailed it. And as I told you, when we were getting ready to do this, here is maybe the greatest coincidence in the history of Planetary Radio.

Bruce Betts: Oh, I think it is.

Mat Kaplan: Our winner is John Turtle, a first time winner in Massachusetts. His response was more specific. He said, if it came down at about 10 and a half degrees latitude, 192.3 degrees west longitude, remember that number. That would put it a little east of Tuamotu Island north of Vanuatu, in the western Pacific Ocean. Of course, did he come close enough?

Bruce Betts: Definitely, nailed it.

Mat Kaplan: John, congratulations. You have won yourself a Planetary Radio T-shirt from The Planetary Society store. You can reach that at planetary.org/store or chopshopstore.com, because that's where it's all located. Please explain to people why we talk about this being such a coincidence, related to John's last name?

Bruce Betts: Because his daughter is Zippy turtle, the principal investigator.

Mat Kaplan: I didn't get that. This is Zibi's father?

Bruce Betts: Yeah, what were you talking about?

Mat Kaplan: I just thought they just shared the same last name.

Bruce Betts: No. No, that's why it's the greatest coincidence in the history of Planetary Radio.

Mat Kaplan: It's even better, okay.

Bruce Betts: He is her father. I've interacted with him in email. Yes, so this is Zibi Turtle, the person leading the mission that next goes to Titan. It's her father winning a trivia contest randomly about Titan and the last probe to go there, Huygens. And if you don't believe it's random, one, Mat didn't realize it was actually her father. And two, even if you can't trust me, which you can't, you can always trust Mat.

Mat Kaplan: Thank you. Thank you so much. I'm going to go buy a lottery ticket or two, I think right now.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, I think so. But that is going to be a super cool mission, with a flying machine on Titan.

Mat Kaplan: This gets better and better. And here's even more, Michael [Kesbol 00:50:28] in Germany, said that, Huygens would have to swim, if it came down up that spot on the Pacific Ocean, would have to swim about 42 kilometers toward Taumako of the Duff Islands to get dry feet. Of course, it had to be 42 and hopefully have a towel at hand.

Bruce Betts: To dry up.

Mat Kaplan: Yeah, well, not just that, towels are good for everything.

Bruce Betts: That's what I've heard.

Mat Kaplan: We miss you so much, Douglas Adams. Darren Ritchie, Washington, I was a little perplexed by the published coordinates for Huygens landing site. Like we said earlier, it's 192 degrees or so, a little bit more than that, west longitude. He says, longitude is usually quoted from 180 east to 180 west, so any idea why they give 192 west rather than 168 degrees east?

Bruce Betts: Definitions like that are, of course, pretty much arbitrary, which direction you go and how far around you go. Earth is often done as plus and minus, I didn't think it odd, because nearly all the planetary map coordinates are done from zero to 360. Sometimes they've even changed the default. So for Mars, back in the old days when I was researching it using stone tablets, Mars was measured in one direction in the west and then in 2000 or so, they measured it to the east. But they used slightly different subtleties of planetocentric versus planetographic. We won't go into all of that now, but stand to reason, people think about this and people have to agree. Because longitude, unlike latitude, even latitude, longitude is arbitrary in pretty much every sense, and latitude varies depending on whether you consider it a spherical object or a non-spherical object, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera, babble, babble, babble. That's all I'm going to say.

Mat Kaplan: This reminds me of, as documented in the book Longitude, the fight over where to put the Prime Meridian. Because there were so many cities that wanted to host it. And London finally won out over Paris and others, very interesting stuff. Andrew [Colosi 00:52:39] in Chile, Maryland, talking about Tuvalu. He says, judging from the clear waters, palm trees and relaxing aura, it's a place that would seem as alien to me as Titan itself.

Bruce Betts: Yeah, it was interesting. I love these rabbit holes. I learned about the Duff islands. I mean, where else can you go where you're learning about space and the Duff Islands?

Mat Kaplan: And in total agreement was Hans Christian Nielsen in Norway. He says, he hopes there would have been a pina colada waiting for Huygens.

Bruce Betts: It would have been very frozen, despite the alcohol.

Mat Kaplan: Maybe they make them with liquid methane there.

Bruce Betts: Ooh, tasty, and so good for you.

Mat Kaplan: We're ready to move on.

Bruce Betts: Here's another one, we're going to tie Earth to Mars in longitudes, it's going to be fabulous. Going to have to dig a little and think a little. What person's name has to do with both Earth's and Mars's prime meridian? So there is a person's name that has to do with both of those, not necessarily in the same way. Go to planetary.org/radiocontest.

Mat Kaplan: You have until Wednesday, February 3rd at 8:00 AM Pacific Time to get us this answer. And a never before offered prize, because of course, we've never offered Planetfest '21 before. It is the brand new Planetfest '21 T-shirt. So if you can't be there in-person, and by the way, no one will be there in person because it's a virtual event, for obvious reasons this year, you can still win the T-shirt. And it's really cool. It's a great design. We're done.

Bruce Betts: All right, everybody go out there, look in the night sky and think about what magical weird coincidence will happen in your life. Thank you. Good night.

Mat Kaplan: Well, coincidentally, that's Bruce Betts, the chief scientist of The Planetary Society who joins us every week. What a coincidence for What's Up. Planetary Radio is produced by The Planetary Society in Pasadena, California. And it's made possible by its skeptical yet enthusiastic members, join them at planetary.org/membership. Mark Hilverda is our associate producer, Josh Doyle composed our theme which is arranged and performed by Peter Schlosser. Ad Astra.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth