A.J.S. Rayl • Dec 02, 2018

The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Team Continues Search for Opportunity’s Signal as Windy Season Begins

Sols 5252-5280

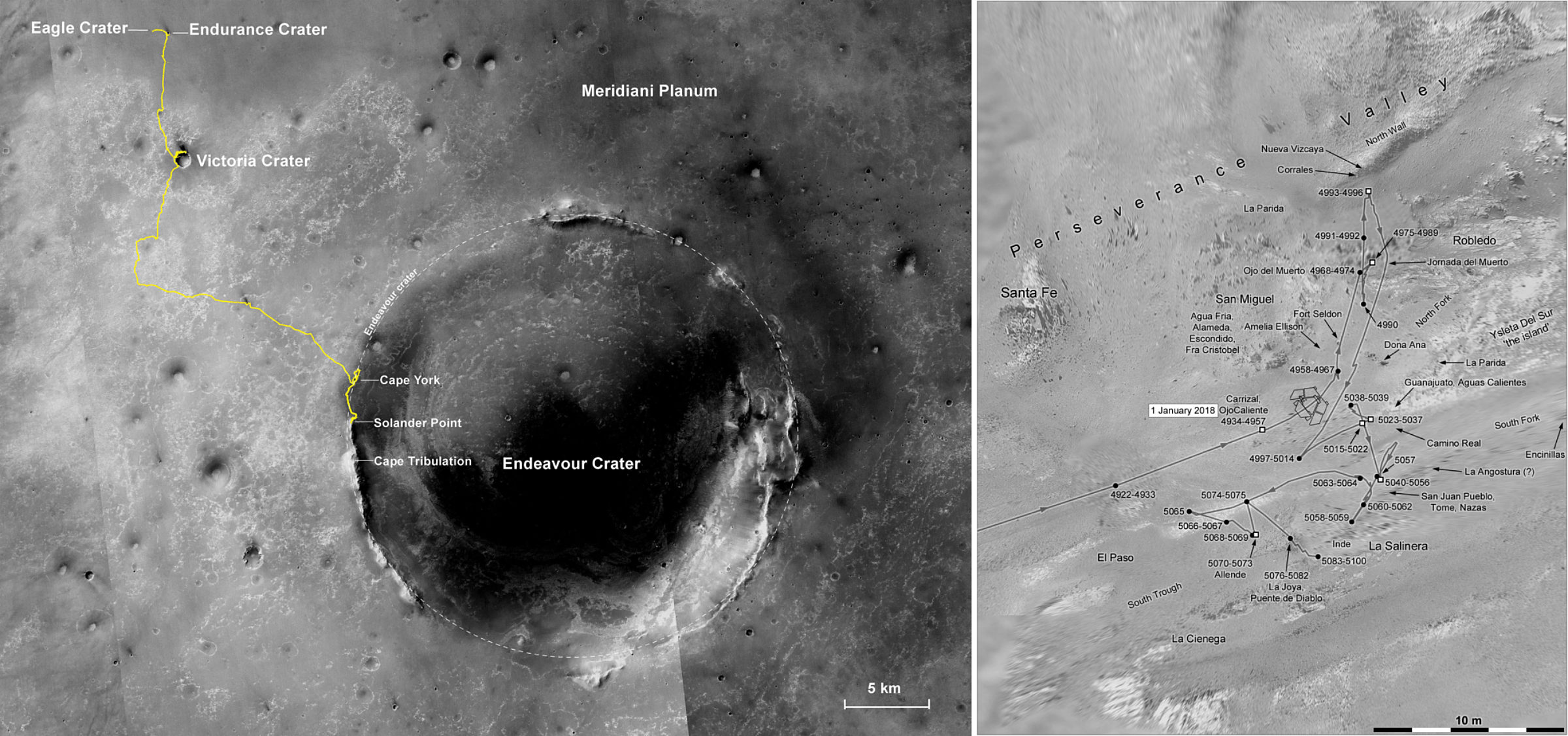

While InSight closed in on the Red Planet and NASA and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) focused on getting that lander down on the surface safely in November, the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) team, working with operators at the Deep Space Network (DSN), spent the month continuing to search for a signal from Opportunity. Despite a host of false alarms, the rover that shattered virtually every robot record on Mars, completed the first-ever marathon on another planet, and is the longest-lived Martian explorer remained silent, presumably still sleeping at her site halfway down Perseverance Valley, along the western rim of Endeavour Crater.

The end of November marked 173 days since the MER team has heard from its rover. The last downlink received from Opportunity arrived June 10, 2018, and the minimal amount of data the rover returned revealed the planet encircling dust event (PEDE) was blotting out the Sun in a way the mission had never before experienced, reducing the solar-powered rover’s energy to the lowest ever recorded on the mission and forcing the ‘bot to shut down and enter into a kind of hibernation mode.

Along with the team, countless thousands of followers around the world have been waiting too, hoping that Opportunity will phone home soon. “We miss her,” said MER aficionado, author, and astronomy outreach educator Stuart Atkinson, who has been blogging about the rover’s mission for the last decade.

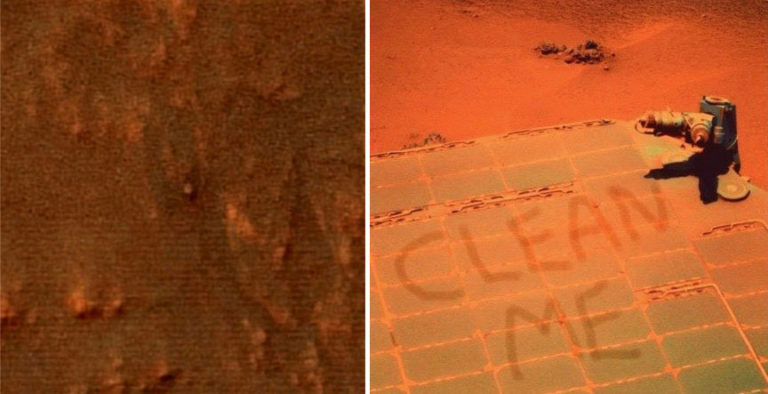

Although it’s been five and a half months, the sound of silence was still not all that surprising to members of the MER operations team and they have not lost hope, not yet. The mission’s long history on Mars indicates the dust-cleaning season that comes every Martian summer has begun, and that gave the team a sense of renewed optimism that in coming weeks their rover will be gifted with gusts of wind that will clear some of the accumulated dust on the solar arrays and enable the ‘bot to recharge her batteries, power up, and phone home.

“It has been a long time since we’ve heard from Opportunity,” said JPL’s MER Power Team lead Jennifer Herman, at month’s end. “But it’s still summer in the southern hemisphere of Mars and it’s not that cold. There’s a lot of cause for optimism, because we’ve only been in dust-cleaning season for 12 days at best.”

With the approval of NASA headquarters in late October, the MER operations team continued its two-pronged strategy to make contact with the beloved veteran robot field geologist throughout November. The strategy includes what JPL mission operations engineers call sweep-and-beeps, a procedure of actively listening and searching for the Opportunity’s signal multiple times a day during the mission’s assigned time slot on the DSN, on both wavelengths of the signal on which the rover may be trying to communicate. If they find their ‘bot’s signal and can lock on it, the engineers would then command or ‘nudge’ the rover to respond.

Additionally, the team continued listening passively for Opportunity on “virtually every DSN track” from Mars, as MER Project Scientist Matt Golombek put it, using the network’s highly sensitive Radio Science Receivers that record all signals from Mars at the network’s sites around the world.

Meanwhile, the sky over Endeavour cleared a bit more; the MER thermal team ran some new simulations that showed the Martian temperature at Opportunity’s site is not so cold that the rover is in imminent danger of having to turn on her heaters; and the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) took another image of Opportunity in Perseverance Valley that doesn’t appear to show any significant change at the site, which in turn would seem to indicate that the windy season has not really kicked up yet at Endeavour, or at least in Perseverance Valley where Opportunity is hunkered down.

As it turned out, November was essentially “a repeat of October,” according to JPL Spacecraft Systems Engineer/Flight Director Michael Staab.

Signals that looked like they might be from Opportunity did pop up periodically on the DSN board throughout the month. “But they have all been false positives, mostly from MRO, and there isn’t a lot new right now,” said JPL’s Chief of MER Engineering Bill Nelson.

“It has been a bit of a quiet November,” added MER Deputy Project Scientist Abby Fraeman, of JPL-Caltech. “We’re happy for our new neighbor, InSight, and we’re continuing the sweeping-and-beeping and passively listening, and hopefully, we’ll get a gift from the Martian winds picking up.”

Anxious as the MER team is to get their rover roving again, the beginning of dust season has lifted spirits among scientists and engineers alike. “I think the team is hopeful, but realistic,” offered Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis. “And excited about possibilities that we could continue driving and exploring.”

Deep Dive into November

As November dawned at Endeavour Crater the atmospheric opacity or Tau over Opportunity’s site in Perseverance Valley was estimated from orbit to be at typical seasonal levels between 1.0 and 1.2, according to Bruce Cantor of Malin Space Science Systems (MSSS), who produces the weekly Mars Weather Reports with the Mars Color Imager (MARCI) camera onboard MRO.

The monster planet encircling dust event (PEDE) that stopped the rover and the MER mission in their tracks in mid-June was officially deemed over in September. But the secondary or decay phase – wherein all the dust that was kicked high into the atmosphere settles out and down to the surface – lingered into the first sols of November.

By the end of the first week of the month however, the Tau, as estimated from the MARCI orbital data and modeling by Cantor, had dropped to 0.8. Dust activity across much of Mars was “relatively uneventful,” and the sky over Endeavour Crater would be storm free throughout the month.

The ops team continued planning as they have since Opportunity checked into hibernation. “We’re still building the plans so all the tools still flow and the team stays in the routine of operations,” noted Herman.

Once Opportunity does phone home, if she does, the ops team assumes they will have to address a number of faults, including a mission clock fault, a low-power fault, and an up-loss timer fault, and they are well prepared for that.

The MER science team has continued working too, even as most of the scientists have also worked on other missions and/or devoted time to things they put on the back burner. “As a science team, we are forging ahead,” said Fraeman.

Arvidson started work in November on the draft for MER’s 12th mission extension, which is due February 14th next year and would keep Opportunity roving for three more years if the team succeeds in recovering their charge.

“We’ve had some science discussions to help frame out the 12th extended mission proposal and to keep the morale up,” said Arvidson. The rover and her human colleagues would continue, of course, exploring Perseverance Valley, and then head into Endeavour Crater, as previously reported in The MER Update.

“One of the insights is that we’re in the upper half of the Valley and if this was a valley where sediment was brought downhill, most of it should be at the bottom half, which we haven’t been to yet,” Arvidson noted. “Well that’s pretty exciting. So, we would probably continue down the hill, finish Perseverance Valley, get into the moat, and then keep driving up until the central mound,” he said.

The moat that Arvidson is talking about is what he describes as “a gentle valley that is a couple of kilometers wide hugging up against the eastern and western sides of the crater, beginning in the south and then kind of bifurcating around the mound.”

If you look down at the interior or the crater, imagine a horseshoe. Place the imaginary horseshoe with the rounded end on the southern side, and the would-be imprint of the horseshoe is where this bifurcating valley or moat is located.

“So you have this general valley extending down from Perseverance Valley into what we think are the sulfates, and then it continues east and goes up gradually to this subtle mound in the center of the crater that is pushed up a little bit against the northern side,” said Arvidson.“As you go downhill and uphill, you go through different strata of what appear to be sulfates from CRISM.”

To clarify: this moat is not believed to be some ancient, water-filled remnant like those that surrounded old castles and fortresses in the days of King Arthur, but rather was likely excavated by wind. Mackenzie Day, who as a doctoral student at the University Texas worked on Curiosity and is now an Assistant Professor in the Earth, Planetary and Space Sciences department at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), published the wind excavation theory for a similar moat at Mt. Sharp, where Oppy’s younger cousin Curiosity, is working.

In essence, Day and her colleagues proposed that wind vortices close to the interior rim of Gale Crater, excavated the softer materials on the inside of the crater to form a moat and central mound. Their peer-reviewed paper titled “Carving intracrater layered deposits with wind on Mars,” was published in Geophysical Research Letters in 2016. “Although this paper is not specifically about Endeavour, it’s the same process,” said Arvidson.

The MER proposal for a 12th mission extension then, as it is shaping up now, would finish off Perseverance Valley, the rocks, the structures, evidence for water alteration, and any potential deposits created by water flow. Then, once inside the crater, the rover and the team would conduct what Arvidson colloquially calls ‘Burns in a Bucket’ or ‘Burns in a Bowl’ to determine how sulfate-rich sandstones are generated in a bowl-shaped object, and in a crater that is 22 kilometers for Endeavour versus 150 kilometers for Gale, where there is also a section of hydrated sulfates, sulfate sandstones likely, on Mt Sharp.

“This research would provide a nice kind of contrast,” said Arvidson. “Are the sulfate sandstones in Endeavour spring deposits because the walls or so steep? Or are they lake deposits where the groundwater is coming up, or what the heck is going on? There’s a lot to do.”

Members of the MER science team agree that there is a lot more exciting science research to be done. At the same time, as they look back along the tracks Opportunity has made and think about what they have done to this point and what the rover and the team have found, “we have done so much,” said Fraeman. “Even if we don’t recover the vehicle, this is still a good use of our time, thinking ahead to what’s next.”

A number of signals that various mission followers believed were from Opportunity lit the Twittersphere in November, but they all turned out to be from another spacecraft. “MRO is our primary culprit,” said Staab.

Remember, MRO has a spare Spirit radio that broadcasts on a channel that is very close to Opportunity’s channel. Since everyone thought that the MERs would both be gone by the time MRO arrived in orbit, the orbiter took with it one of Spirit’s spare radios. When MRO aerobraked into orbit and Spirit was still going strong, the teams had to work together to adapt to the unique issues around commanding Spirit. Basically, the problem was resolved with the creation of a commanding procedure that came to be known as the Mars Uplink Keep Out Window [MUKOW].

The term “keep out” refers to scheduling the DSN uplink to MRO to be turned off at an agreed-to time, to keep it out of the MER Small Deep Space Transponder (SDST) receiver when MER uplinking is required, and to scheduling the uplink to MER to be turned off to keep it out of the MRO SDST receiver when MRO uplinking is required, as Jim Taylor, Dennis K. Lee, and Shervin Shambayati explained it in a 2006 paper on MRO’s Telecommunications for JPL’s Deep Space Communications and Navigation Systems Center of Excellence (DESCANSO). “The scheduling was required as an agreement between the projects both for the projects’ planning purposes and because the DSN stations allocated to different projects are operated separately,” they wrote.

These days, with the Doppler shift created as MRO moves around in orbit, “MRO’s signal can very easily look like Opportunity and people can get faked out,” said Staab. “So whether we’re listening passively or actively commanding, we get false alarm hits from MRO all the time. But we can tell very quickly whether it’s us or whether it’s the orbiter. I remember one incident in August that you covered where it appeared Opportunity was in lock and transmitting 6 megabits per second. Well, we knew very quickly that that was not us, because Opportunity’s maximum data rate on its X-band system from the surface is 28 kilobits not 6 megabits – that’s a big difference,” he said.

On November 25th, Principal Investigator of the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard MRO Alfred McEwen, a professor of planetary geology and director of the Planetary Image Research Laboratory at the University of Arizona, distributed the latest orbital image of Opportunity and Perseverance Valley, reportedly to be released soon.

“It appears to show little change in Opportunity’s brightness, although Alfred relays that you can’t say that absolutely without doing some calculations, because of the different light and viewing conditions,” said Arvidson. “Visually however nothing seems to have changed in the scene. Even the delicate wind streaks have not changed. So, if the windy season has begun, it doesn’t seem to have impacted Perseverance Valley or Opportunity yet.”

Given that the HiRISE images are taken from an altitude that varies from 200 to 400 kilometers (about 125 to 250 miles) above Mars, these orbital images do not have the resolution that enable the team, or anyone for that matter, to actually see Opportunity close up or detect how much dust may be coating her solar arrays, or even a reliable view of the amount of dust on the surface.

“The HiRISE images can only tell us if something major happened, so Opportunity could have gotten a little bit of dust cleaning and we just can’t see it yet at this spatial scale,” Staab noted. “The image could also be telling us that we’re just at the beginning of the time of year when the winds should pick up and it could be the fact that we don’t see any major changes is a good thing.”

This much is certain: the new HiRISE image doesn’t indicate that a major wind event has occurred in Perseverance or Endeavour yet. “We really are going to be looking for major changes,” said Staab. “If, when we see those and we still haven’t heard from the vehicle, that, I think, would be the most concerning scenario that could happen.”

The science team meetings and the onset of the dust-cleaning season have buoyed the MER team’s inherent optimism. Still, “it’s been tough,” said Fraeman. “It’s easy to feel that with every passing day we haven’t heard from Opportunity, that something else is more seriously wrong, and that it’s going to be extremely difficult to recover the rover. We’re trying to be realistic. We really want to get the vehicle back, but we understand that MER is an old mission, and Opportunity is an old rover,” she said.

At the same time, the science team knows and honors the challenge that the MER ops engineers are confronting. “We definitely give a shout out to the engineering team. If Opportunity is recoverable, we will recover this rover, I have no doubt in my mind that the engineering team will be able to do that.”

Theoretically, the prospects for Opportunity phoning home still look good and the MER team has forever been fueled by its optimism and “a lucky star,” as MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres called it way back when. It’s still summer at Endeavour Crater so the rover is not freezing past the point of no return, and the batteries should be resilient enough to be recharged, as reported in the last issue of The MER Update.

Now if Mars will just whip up some gusts of wind to clear some of the dust from Opportunity’s solar arrays, the rover should be good to go, provided, of course, there hasn’t been a mission catastrophic event on the nearly 15-year old robot.

“I do feel hopeful that we will hear from Opportunity soon,” Herman said. “Ls 290 is when historically we’ve seen dust cleaning due to wind. That just started November 17th, so in December and January there are lots of chances for wind gusts to clear off some of the accumulated dust on Opportunity’s solar arrays.”

Of course, she noted that the onset of the dust-cleaning season is not like flipping a switch. “Historically, Ls 290 is the earliest we’ve seen cleaning events, but it doesn’t mean that the winds automatically pick up on November 17th,” Herman said. “Sometimes they start later.”

The windy season generally lasts through Ls 330, which this Mars year falls on January 26, 2019. There was one year (Mars Year 3 for the mission) when there was a short burst of dust cleaning from Ls 345 to Ls 350 (which is coming up in March 2019). “But most of the time the winds blow a lot until Ls 330, and then the bulk of dust cleaning is over,” said Herman. “I’ve reviewed the historical data, and consistently by Ls 335, the rover is accumulating dust.”

Overall, the MER ops team has experienced “a kind of a resurgence of enthusiasm” in November, as Nelson viewed it. “Hope still springs eternal here. But it’s been a long wait and anticipation does run high at this point.”

The team is as prepared, rehearsed, and ready, as it is eager to recover Opportunity. “We have pretty much completed all our planning and we continue to do some low level work in preparation for recovery, most everything is in place,” Nelson said. “We’re now just playing a waiting game, hoping for something to break for us. I know that’s not very exciting, but that’s where we’re at.”

Not leaving anything to chance, the ops engineers are beginning to talk about their Hail Mary planning scenarios and MER Project Manager John Callas is working with the Mars Program office to determine when they might start deploying those, according to Staab. [More on that next month.]

“If we get into the first couple weeks of January and we haven’t heard anything, then I would say that at that point I will probably start getting worried that the arrays are just not getting cleaned off and we may be in trouble, which is why we would then enact Hail Mary scenarios,” Staab said. “But we’re less than two weeks into cleaning season, so I wouldn’t say there is any cause for real alarm just yet.”

No matter what happens, a little bit of MER lives on in all missions to Mars these days. Every planetary mission, especially landed missions on the Red Planet stand on the shoulders of the giants that went before them.“There’s a lot of MER experience that went into making sure InSight could be successful, which I think is pretty cool,” said Fraeman.

As November fades and December begins, the Tau at Endeavour is “definitely below the 0.8 level,” said Cantor. The Tau actually got “too low” at Endeavour Crater for him to continue modeling. “So I’m back to the visual monitoring,” he said. His decades of observational experience, as well as his work on the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) have helped. “Opportunity’s Tau usually runs a couple tenths lower than Curiosity’s.”

It’s important to note however that dust-cleaning season is a season within the Mars spring-summer dust storm season. Therefore, Cantor is keeping an eye out for any new, potentially threatening dust storms that may blow Opportunity’s way. “Mars is pretty quiet these days,” he said. “The big storms don’t pickup again until the latter half of December into January. Now is a good time for a dust devil cleaning event.”

It can’t happen soon enough. At this point, the MER team will keep on keepin’ on, with fingers crossed Mars steps up once again and delivers life-saving winds to Opportunity.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth