A.J.S. Rayl • Oct 04, 2018

The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Team Initiates Plan to Recover Oppy, Orbiter Sends Postcard, Storm Ends

Sols 5193–5222

As the global storm that wrapped the Red Planet in a cloud of dust since late June finally gave up the ghost in September, the sky continued to clear over Endeavour Crater and the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) mission initiated the NASA-approved two-step plan to reestablish contact with Opportunity.

The mission operations team at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), home to all of NASA’s Mars spacecraft, launched the first phase of the strategy on September 11th, by increasing attempts to search for Opportunity’s signal from three times a week to multiple times each day and electronically nudge the rover awake. The team also began listening and looking for the rover’s signal over a broader range of times and frequencies recorded by the Deep Space Network’s (DSN’s) most sensitive radio receivers. But the nearly 15-year-old pioneer explorer has not yet phoned home.

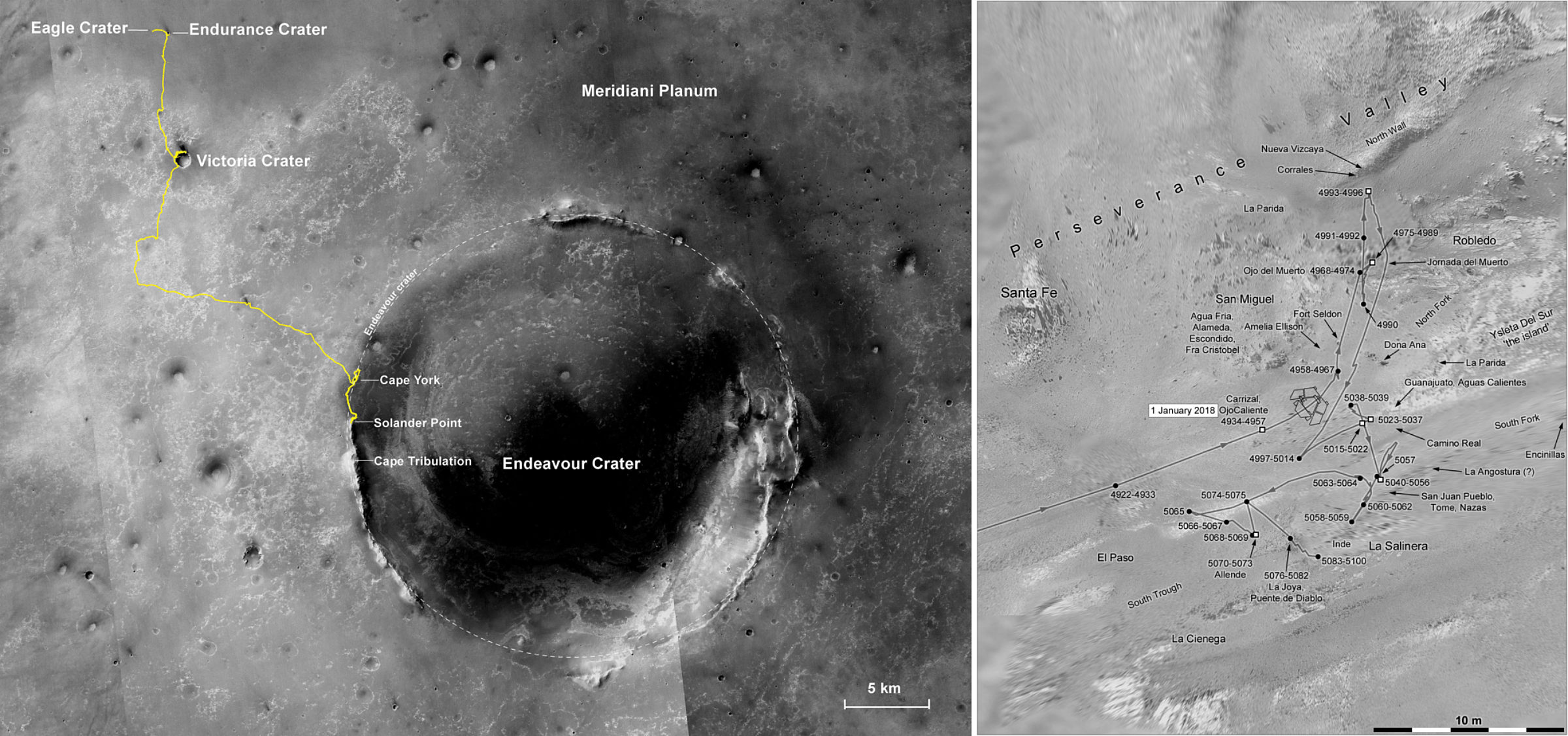

The world was able to see Opportunity in September though, in an image taken by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). From 267 kilometers (about 166 miles) above the surface, the golf cart size robot, looking like a boulder on the landscape, is visible about halfway down Perseverance Valley, tucked inside the western rim of Endeavour Crater. It helped make for another September to remember in this mission’s storied history.

“It was really nice to see Opportunity again,” said MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University. “The rover is right where we left it before the storm and now there it is after the storm, exactly what we were expecting. If it looked different than what we see, that would’ve been a huge surprise.”

The rover appears to almost blend right into the valley, which would seem to imply the rover is about as dust-covered as her surroundings. “But it is very hard to judge just how dusty the rover is from a handful of pixels,” said Squyres.

Obviously, no one can say with certainty from this orbital photograph how much dust is in Perseverance Valley now that wasn’t there before the storm. Still, like gravity, Occam’s Razor applies on Mars too, so far as we know anyway, and all that dust settling out from the atmosphere had to go somewhere.

The last time the MER team heard from Opportunity was in a communiqué she sent home on June 10th, presumably just before the dust storm caused her to shut down all her systems and go into survival mode. That missive revealed the rover was producing a mind-bendingly low 22 watt-hours of energy, about what it takes to power the rover’s clock each day, and the sky overhead was so densely dust-infused it gave the MER mission cause for pause, not to mention an immeasurable record they would have rather not attained.

Most mission operations team members quickly concluded then that they would be waiting for a good long while. “We knew a few days after we lost contact that it was going to be three, four, five months before we might her from Opportunity again,” said JPL System Engineer Michael Staab. One of the mission’s four flight directors, he was tapped to be lead engineer for dust storm ops a couple of weeks before the “mother of all dust storms,” as he described it, stopped the rover in her tracks.

Some MER scientists and engineers have for months now suggested mid-September as the first possibility for a phone call from this rover. It all depends on how much dust the rover had taken on during the storm and during its decay phase when all the dust that was lofted high into the atmosphere settled out on the surface. But, “the dust factor is an absolute unknown,” underscored Mission Manager Scott Lever, of JPL. “Until we get data from the Opportunity, we don’t know. All we can do is speculate.”

Opportunity’s silence in September is not the death knell, not yet anyway. As MER Athena Science Team member and atmospheric scientist Mark Lemmon, Senior Research Scientist of the Space Science Institute (SSI), put it: “It doesn’t tell me that the rover isn’t functioning.”

From what little data the MER ops team has to work with, there is an ardent belief – based mostly on the sheer intensity of the planet-encircling dust event (PEDE) and the mission’s history with Martian storm seasons – that Opportunity is one dirty rover, as reported in the last issue of The MER Update. “The images we have gotten from HiRISE seem to show that the rover is very dusty, which would be indicative that it is not producing a lot of power, and probably hasn’t woken up yet,” said Staab, who with other ops team members have been scrutinizing the pixels that make up the images.

While it isn’t possible to quantify the dust on the rover’s panels from a few pixels, they are seeing more red than blue in the pixels around the area, “even in the few pixels of Opportunity,” Staab said. And red translates to dust. “If the rover was relatively clean, we would see more blue in the rover pixels than red, and so we can at least interpret from this image that the rover and surrounding area is much dustier than it was before the dust storm started.”

Given the tenacity of this PEDE and that fact that Opportunity was effectively at one of its grounds zero, near one of the most intense dust lifting centers, it seems to stand to reason that the rover must be dusty.

“It is still too early.” A sigh seemed to accompany the email from another member of the MER team who agreed. Understandably however, anxiety rose to do battle with the team’s characteristic optimism in September as team members felt the pressure of time begin bearing down.

September’s end marked 112 sols or Martian days without communication. Over the past 14 years and nine months, this team has never gone long without communicating with Opportunity, and never this long. They have no idea of the rover’s current state of health or how many faults she has tripped, or the state of her batteries, or how dirty her solar arrays are. “The team is very worried about the future of Opportunity,” acknowledged MER Project Manager John Callas, of JPL.

The second step of the strategy to recover the rover, known as passive listening, an expanded version of what the ops team has been doing since losing contact in June, is currently scheduled to begin in a few weeks, near the end of October. This phase – which will run at least through January 2019 – will essentially continue ‘keeping an ear out’ for Opportunity through the DSN’s global array of sensitive radio receivers around Earth.

“Walking away anytime before the end of January would mean we could be leaving a potentially perfectly working spacecraft on the surface because we’re impatient,” said Staab, an assessment that Lemmon has also made.

Beyond January 2019, if Opportunity still has not phoned home, the receivers on the DSN are always listening when Mars is in the field of view. “Anytime there is a deep space telescope on the DSN pointing toward Mars, we will hear or see the signal from the rover if it comes, even past January,” said MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis.

At that point, however, it really will be a race against time. The mission’s history shows that good gusts of dust clearing winds have blown across Meridiani Planum through March, which is, arguably, the official end of the dust season, and there is a desire on the part of many team members to keep reaching out for Oppy until then. After that fall will be moving in and the team would need to begin preparing the rover for winter. That, however, is then.

In the meantime, if Opportunity is as dust-laden as many team members believe she is, the rover, after so many months in silent solitude, may well need an actively commanded electronic nudge in the weeks following the 45-day intensive outreach. Especially considering that from July through the southern summer solstice on October 16th the rover is most likely, taking on dust as Jennifer Herman, MER’s power team lead pointed out in the last MER Update.

“We have been discussing this in our team meetings and there is a feeling that the dust loading on the solar arrays might be a little too much for expectation of anything within 45 days,” said Arvidson.

Simply reviewed, as the mission’s history on Mars has shown and considering the intensity of the planet-encircling dust event (PEDE), Opportunity is likely in serious need of dust cleaning. Team members are hanging their hopes on the windy season they know is coming.

If the mission’s lucky star is still shining, Mars will produce the needed dust devils and wind gusts to whisk some of the recently accumulated layers of dust from the rover’s solar arrays and that could make all the difference in the world of MER. “I think we have a very good engineering case that our commanding attempts will have a higher probability of working then, rather than right now when the rover is dusty and probably not waking up,” said Staab.

Therein lies the rub, which, in essence, is at the crux of what caused so much consternation and confusion after NASA-JPL first announced the two-step plan by press release on August 30th. The winds will arrive during the second step of the two-step strategy, when the team members are slated to only be passively listening for Opportunity.

Social media twizzled and whirled with talk that NASA was going to pull the plug on the world’s beloved rover and that message became the buzz. “It is unfortunate that people thought the agency was trying to find an easy way to not do much to recover Opportunity,” said Richard Zurek, Chief Scientist of the Mars Program Office at JPL and MRO. “That is not the case,” he added, reiterating what he said in the last issue of The MER Update.

In fact, Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA's Associate Administrator for the Science Mission Directorate,who, along with Mars of course, holds the rover’s fate in his hands, showed his support on Twitter in early September when he posted a message that read in part: “Rest assured we are not giving up. We are listening and working to recover Oppy. The mission is funded through end of FY19.”

Said Callas at month’s end: “NASA continues to keep saying to me that they fully support the recovery of this rover. And they want us to do all we can to try to recover Opportunity.”

The plan for Opportunity is flexible, Zurek said, noting that the team may be allowed “to recommence” active commanding during the windy period, “based on the assessment at that time.”

The other good news to emerge from this September is that the monster dust event that stopped Opportunity and the MER mission in their tracks finally stopped itself.“The 2018 PEDE is officially over,” Mars weatherman Bruce Cantor, of Malin Space Science Systems, told The MER Update. “It’s dusty, but within the seasonal normal range now.”

Even if Mars cues the winds in next few months and assuming Oppy gets a cleaning or two or three and is able to produce enough solar energy to recharge, wake up, and phone home, she won’t be roving on immediately. It will take a month, maybe two for the team to recover the ‘bot. And beyond the challenge of recovery, there are environmental conditions and upcoming season changes with which they must contend.

The insulation provided by dust cloud that blanketed the planet and effectively kept the Martian surface warmer at night during the storm event, for example, has disappeared; therefore, the surface is slowly getting colder at night than it has been during the last few months. Opportunity is however benefitting from the fact that Mars just passed through perihelion, the closest the Red Planet will get to the Sun in its eccentric orbit until the next perihelion in 2020. And, the summer solstice in the southern hemisphere of Mars where Endeavour Crater and Opportunity are located, is coming up October 16th.

So, the outlook in terms of the planet’s wicked freezing temperatures will continue to be pretty good for a while. “We’re just going into summer and so the temperatures aren’t going to be cold enough to break anything on the rover,” said Staab. “The real concern is the dust.”

There are plans in the works now, Arvidson said, to try and look at all that darn Martian dust and monitor the surface changes over the next few months with MRO instruments, including the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), HiRISE, and the Context Camera (CTX), which provides wider context for the data collected by the other two instruments.The efforts, spearheaded by Arvidson, may enable the scientists to determine how much darn dust is darkening MER’s doorstep at Endeavour, and perhaps even infer how dirty Earth’s longest-lived robot explorer on Mars actually is.

“We probably do have a fair amount of dust on the arrays and we probably also need the dust in the sky to clear more before we are likely to hear from the rover,” said Chief of MER Engineering Bill Nelson, of JPL, as September came to an end. “But I’m still optimistic.”

So too is his team of MER ops engineers who are ready as ever to recover their rover. “We’re just in a holding pattern waiting for the spacecraft to talk with us,” said Staab, who developed the listening strategy and the recovery strategy everyone everywhere hopes they will be deploying soon.

“What we have to do is the active commanding and listening campaign we are doing right now,” said Squyres. “We’re doing all the right things and we’re keeping our fingers crossed.”

Deep Dive into September

When September popped over the horizon at Meridiani Planum Mars, the PEDE was still on a path of decay. The dust cloud that had blanketed the planet was continuing break apart, the dust was settling out, and the opacity or Tau, the measurement of dust in the atmosphere over Endeavour Crater and the rover’s site in Perseverance Valley had dropped from an all time high of 10.8 in June to below 1.6.

While their robot field geologist was still presumably sleeping, the MER team was working. The op team members were either listening for the rover during the expected fault communication windows and trying to actively command a signal to ping her three times a week or passive listening over a Deep Space Network Radio Science Receiver that records all signals from Mars.

The Mission Planning Team, which Lever leads, built the communication windows for Opportunity, the direct-from-Earth X band comms and the UHF communication relays with NASA’s Mars orbiters. “Even though we cannot command those to the rover until it wakes up, we have to be prepared to command those when it does wake up in case we deem it necessary to get those onboard,” Lever explained.

Thus, the MER ops team continued to build the full complement of comm windows just as they do when Opportunity is awake. This part of the mission actually only changed in that the engineers were choosing contingency fault windows instead of active guaranteed windows, since the rover has likely tripped three faults: low-power fault; an up-loss timer fault; and a mission clock fault, which would mean the rover if it had awoken doesn’t know what time it is.

In the chosen communication windows, the team sent beep requests one to three times a week, as they have since Opportunity hunkered down and went into survival mode. “We have been commanding the rover roughly around 11:30 Local Solar Time (LST) every morning if we had a DSN track that lined up with that,” said Staab. “There were some constraints on whether we would use these DSN tracks or not, because we didn’t think at that point we would hear from it. There was just too much dust in the atmosphere for the rover to wake up.”

In a move back to tradition and to help boost morale, the team has returned to using wake-up songs just like the original crew did when this overland expedition began and the team dropped the needle on The Beatles “Good Morning Good Morning” for Spirit’s Sol 2. on “We use songs every day,” Staab said. The flight director of the day picks the song, which is then usually played around the time they are to begin commanding. Since the team often posts the song choices on Twitter, they have gotten notice. Not long after they used Kansas’ 1977 smash hit, “Dust in the Wind,” for example, band members reached out in acknowledgment and gratitude.

Social media, meanwhile, was still pulsating in the early days of September as a result of the NASA-JPL press release on August 30th that announced the strategy to try and recover Opportunity. “I know people are worried,” Zurek told The MER Update. “There was a misunderstanding – ‘What? They just want to cut it off?!’” he said summarizing the public response. “There was a breakdown in communication, and something people often don’t understand is that NASA is working to fit this effort into a whole program of activities on Mars that extends to the new missions, as well as our continuing missions.”

NASA’s next Mars lander, InSight, is scheduled to land November 26th and arrivals at Mars always get DSN priority, with other missions standing down when necessary. The DSN is the only international network of antennas that provide the communication links between the scientists and engineers on Earth to the spacecraft and rovers on Mars. It is comprised of three deep-space communications facilities placed approximately 120 degrees apart around the world: at Goldstone, in California's Mojave Desert; near Madrid, Spain; and near Canberra, Australia. This strategic placement allows for constant observation of spacecraft as the Earth rotates on its own axis.

“The 45 days is not the whole story,” Zurek continued. “That’s one interim period of activity scheduled within the scope of things happening around it, and when that’s over we’re going to do an assessment. If we start to see things that indicate, either from past data or our current observations, that there may be cleaning events in the vicinity of Opportunity, that may trigger another round of activity,” he said.

The team has been on it. MER Power Lead Jennifer Herman and other MERtians have been reviewing cleaning events in previous Mars years, as reported in the last issue of The MER Update. “Assuming that the weather system hasn’t been so affected by the dust storm that this seasonality changed, these cleaning events would probably happen more in the December-January timeframe,” said Zurek. “And there will be other periods of wind activity. We just don’t know when.”

While there has been no decision about continuing the active commanding past October, “we are talking about it,” Zurek said. “The bottom line is that we have not given up and we’re not going to give up as long as there are reasonable things to try.”

The NASA-approved two-step plan called for the intensified 45-day outreach to begin once the Tau dropped to 1.5 or lower over a consecutive number of sols or Martian days. Since Opportunity is still sleeping, the estimates of dust are still coming from orbital observations. Using imagery data from the Mars Color Imager (MARCI) onboard MRO, Cantor determined that the Tau at Endeavour had dropped below 1.5 for two consecutive measurements during the first week and a half of September.

Quietly, while Americans on Earth were remembering and honoring the 2,977 people who lost their lives during the four, coordinated Al-Qaeda terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the MER ops team launched the outreach and listening strategy on Opportunity’s Sol 5202,increasing the frequency of commands it beams to the rover via the DSN from three times a week to multiple times per day in a protocol they call sweep-and-beeps.

“Now that the Tau is decreasing, we basically command everyday,” said Staab, who is overseeing the sweep-and-beeps that are part of the listening strategy he developed.

Essentially, they are scanning the frequencies coming from Mars and searching for Opportunity’s radio receiver frequency and trying to lock onto it. “We sweep the frequencies, try to get a coherent link, and then we send a beep sequencewhich is basically a five-minute carrier to force the rover to talk to us,” Staab explained.

It works like this: Opportunity has a transmitter and a receiver for radio waves, and she knows how to interpret the information received and act on it.“The sweep-and-beep is a process of trying to get a signal into the rover’s receiver,” said Nelson. “The radio has a particular frequency that it naturally goes to, called a rest frequency, also known as the best lock frequency or BLF.”

If you think about tuning an old analogue radio, as you tune across the dial you hear stations blip in and blip out. “Each one of those stations is in effect on its own BLF,” said Nelson. That’s where the analogy breaks down because we don’t do two-way with our radio stations on Earth. With Opportunity, we want to hit the frequency that the rover is on and we don’t know quite where it is.”

Opportunity’s frequency is generated by an onboard oscillator that responds to temperature changes, which makes the BLF temperature sensitive. “So what we’re doing is sweeping the frequency,” Nelson continued.

The sweep is actually a programmed phase lock tracking loop. “It’s a templated change for the transmitter on Earth, called the MAC Sweep, for Magellan Acquisition, and named after the Magellan spacecraft of course,” Nelson said. “It calls for the frequency to be driven high, to wait for a dwell and then drop low, wait for another dwell, then come back to a midpoint to rest. While it’s at rest, we then tell it to do the commanding we want to do. We give the parameters we want and tell the DSN station to configure for the MAC template with those parameters.”

Once one sweep is completed, they start another send another and the process repeats over and over. “We do that for as long as we have the uplink, which for us varies from about an hour to an hour and a half and typically getting between four and seven cycles on every uplink,” said Nelson.

The primary objective with the actively commanded sweep-and-beeps is to address the potential that the rover could be in what the engineers call a “checkmate scenario,” where, for example, Opportunity wakes up to phone home autonomously, but shuts down immediately because the day is ending or because it’s the middle of the night or because she doesn’t have the energy to wake-up and phone home. In each of those scenarios, the rover would be trying but unable to communicate with Earth. “The active commanding is to try and get us out of one of these potential checkmates,” Staab said.

“We’re trying to catch the rover while it’s awake, before it shuts down,” summed up Nelson. “If we can command a beep while the rover is up, then we have a chance of actually provoking a response and we’re working on that.”

Since the clock likely faulted, there is a good chance that Opportunity doesn’t know what time it is; conversely, team won’t know what time the rover may be waking up. Therefore, during their DSN pass, the MER ops team sweeps-and-beeps over the entire period they have available to see if they might be able to catch the rover in that mode, if it is in that mode. If they do get Opportunity to respond in this way, they would then know the rover is in this checkmate mode. “We can then take action to get out of that mode, and then we will better know how to further communicate with the rover,” Callas said.

The mission has its regular, original allocations on both 34 and 70-meter stations in the DSN complex of dishes in Goldstone, California, Canberra, Australia, and Madrid, Spain. Because Mars is in a particular part of the sky and the team only listens at a particular time of day, their signals beam from one station for a period of several days until Mars moves across the sky and then they switch to another complex.

During their assigned timeslots, the team members have been sweeping-and-beeping as much as they can and the pace increased significantly in September. Indeed, the team has been sending commands to the rover almost since the sol after they lost contact, in what Callas called “a simplified version” of sweep-and-beep. “What we’re doing now is sweeping over a larger frequency range than the original beeps that we were sending early on,” he said.

Moreover, the ops engineers are actively commanding every time they have the chance. “We are sending as many sweep-and-beep cycles as we can on every uplink, so we have gone from one to three commanded beeps a week to about 28 or 30 beeps a week,” Nelson pointed out. “We’re trying to kind of pepper the sky with these things.”

At the same time, team members have given plenty of thought to why Opportunity might not be responding if the dust on her solar arrays is not as thick as they think. “It has been suggested that we are commanding just a little too late in the day, that we should be commanding earlier in the sol,” said Nelson. “And there is some rationale for that.”

Therefore, the mission is now trying to move some of their dish time earlier and/or negotiate their timeslot to pick up the Martian mornings at Endeavour. “We’re trying to widen our pattern,” Lever said. “We figure that we’re on a nice easterly tilt and when the Sun comes up, chances are we could get a solar array wake up in the morning instead of at noon. We’re massaging our strategies in different ways to try to be effective and broad.”

While everyone on the team, and fans around the world for that matter, are hoping Oppy will wake up and autonomously beep one of these days, the engineers are doing everything but waiting around. They spent time in September working on “some Hail Mary type commanding strategies,” as Staab described them. “If we get close to that end of that soft 45thday end date and haven’t heard from it yet, we may try some of those,” he said.

For now, the expectation is that the sweep-and-beeps will continue pretty much to the end of October, according to Zurek. “There’s not a specific date. It still depends on what we’re hearing and if the dust in the atmosphere clears out more or not,” he said.

In addition to the sweep-and-beeps, JPL and the MER team are expanding the passive listening effort for Opportunity. Basically, the Lab’s Radio Science Group monitors and records all the radio frequencies emanating from Mars with the DSN’s most sensitive broadband receiver, which is called the Very Long Baseline Science Receiver, “the VSR as we call it,” said Callas.“We give them the times where we would like them to listen, which is typically a four-hour time period every day in the middle of the day for the rover.”

From that comes a spectrograph or a time sequence of the spectra collected that can be replayed. The members of the radio group then send these recorded VSR plots via daily emails to the MER team.

The MER flight director on duty scours these records looking for any possible signal from Opportunity. “Every morning we come in to check to see if any of our recordings from the last night pinged anything,” said Staab. “We’ve gotten into the routine for doing the sweep-and-beep commanding and we know what to look for in the VSR recordings, and we’re now we’re just waiting hopefully for that signal we want to see pop up.”

Just to dot the i’s, MER ops team took one of these recordings from Curiosity and conducted a test. “We spit out a Curiosity signal, then listened for it in the radio science recording, and sure enough we could see its signature and it’s very clear that that was Curiosity based on our knowledge of its signature,” said Lever.

Although they have begun to listen with the VSR over a much wider time range, as well as over a much wider frequency range, “so far the flight directors in their reports have all said something to the effect of nothing received today,” said Nelson.

The most unnerving unknown, beyond the dust factor, is that the MER team really has no idea of what Opportunity’s current health status is. Technically, they don’t even know if the rover can wake up. Other than the orbital image, Cantor’s orbital Tau estimates, they’ve got next to nothing. Importantly, they do not know the state of the rover’s batteries.

“We’ve had some discussions about that and on what happens to batteries when they’re at a low state of charge and sit cold for months at a time,” said Staab. “There is the possibility that the electrolyte in the batteries could begin to precipitate out of solution and damage the capacitance of the batteries, but we don’t know that and we don’t have any data to tell us that’s what’s going to happen.”

For a number of reasons however, including Herman’s power models, the predictions hold that the robot and her instruments should have made it through the Martian nights without anything breaking or getting damaged. This, despite the wrath of the storm, and in a way because of it, since the blanketing dust cloud insulated the planet kept the nights warmer than they would have been otherwise.

If Opportunity survived the PEDE intact – that is, nothing broke or degraded to the point of mission over – and is just in need of a serious dust cleaning or two, then there is every good chance that sought-after signal will come.

While all was quiet on the Meridiani Planum front in September, the team members never skipped a beat, spending what spare time they had reviewing strategies, the mission’s own history with Martian dust storms, and working on more unique commanding activities to try and connect with the rover if they get to the end of the 45-day period and haven’t heard the signal they’re wanting to hear. In addition, they are evaluating all of the MER flight rules, subsystem by subsystem, using an MSL software tool called RuleHub, and working to close out Incident Surprise Anomalies or ISAs, analyzing and addressing little issues that have come up with solutions.

On September 20th, MRO flew over Endeavour and HiRISE took the shot of Oppy in Perseverance Valley. Five days later, NASA-JPL released one of the best images. It was greeted with sighs and awwws around the world and the media covered it in a way that caught Squyres. “I was surprised it got so much press coverage,” he said. “And kind of amused that some of that coverage was ‘NASA has found the lost Mars rover,’” he chuckled. “It’s right where we left it. It would have been news if we moved.”

The response was yet another indication of how loved this marathon-running, crater-diving, longest-lived little rover is.

“It’s too bad we can’t see it on a scale where we could say something about what’s on Opportunity’s solar arrays,” mused Zurek. “The rover is big in our heart, but it’s not that big on the surface of Mars. Even so, the image is important because we can see the region around there had brightened and there is dust falling out. That is not a surprise, but it is confirmation that our thinking here is consistent with the known facts.”

“The solar arrays should be producing energy unless they are completely clogged with dust,” said Callas. “If we have a thick layer of dust on the arrays, then the rover is not getting enough energy. That could be the reality. It’s a reasonable speculation at this point.”

Most of the team is pretty confident at this point that the rover is really dusty, maybe dustier than it’s ever been. Given that Opportunity was right in the midst of a dust-lifting center that hung around for days pummeling her with the fine, powdery dust, unlike Curiosity on the other side of the planet, one could argue – how could it not be?

“There is no reason to believe that Opportunity is not very filthy dirty right now,” said Staab. “We’re going to need a lot of cleaning to even have a chance for it to wake up so we can command into it. But the Tau, the amount of dust in the atmosphere continues to drop, and we are entering windy season, so there is no reason to completely lose hope at this point. It’s just that we still have a ways to go.”

In coming weeks, MRO will be gathering more data with CRISM, HiRiSE and the CTX. “We’re planning on making observations over next several months to monitor the surface changes over Endeavour as the storm subsides,” said Arvidson.

With CRISM, which is a little better calibrated and a little more sensitive to dust cover,they may be able to get a better idea of how much dust there might be on the ground. “It would be a way of trying to estimate whether the dust on the arrays is high, medium or low,” said Zurek. “We’re trying things. We’re going to try with CRISM. We don’t know if we can get something out of that, but it’s worth a try and we’re going to give it a try.”

“Obviously we’re not going to be able to resolve the rover in CRISM data, but it could give us a better handle on what’s going on with the dust environment,” Squyres agreed.

The big concern remains the dust. “In talking to some of the atmospheric scientists, it sounds like this storm kicked up a lot of very large particles and there are probably large particle sitting on the arrays,” said Staab.

“Many papers suggest this, and show that the larger particles settle close to the lifting area,” confirmed Lemmon. “Since Opportunity was in a lifting area for some time, if big stuff was lifted, it would likely have settled on and around the rover. It is still in the 'model' area, not the 'data' area, but I think it is likely,” he said.

So maybe all they do need is for Mars to step up, and whip up some winds. It’s still dust storm season of course, and everyone in the Mars community is keeping an eye out for dust devils, signs of gusting winds, and local dust storms. It’s what they do during this life-threatening season.“Most of the time those local storms pass through very quickly and they can move dust around,” said Zurek. “What we’d really like is to have one last little storm to blow the dust off the arrays and then we think we’d be home free.”

They’ve been watching of course, but nothing yet. As it turns out, “right around this period there is a kind of seasonal gap,” Zurek noted.

Even though MER ops team members knew they would be out of touch with Opportunity for months, “it’s been a long haul,” said Nelson. But, he added, “I’m not overly concerned that we haven’t heard from the rover yet.” Most, but not everyone, agrees and some team members vacillate day to day.

Waiting is always the hardest part, but missing Mars is also part of the equation. “After almost 15 years spent looking at images from Mars, I have gotten so used to it that I no longer feel Mars is a distant and harsh place, but now that I have no new pictures, I feel a bit homesick,” said MER-MSL Rover Planner Paolo Bellutta. “It makes me realize how much of my life revolves around Mars, much like Phobos and Deimos.”

While the ops team members are each keeping their noses to the grindstone, the silence and the time pressure of the plan have taken a toll. “Morale has been shaky,” admitted Staab. “We have a very challenging engineering problem to work and we do feel the pressure.”

“Time is the enemy here,” said Callas. “And the longer things go, the more worried you become. As time has gone on, people are getting more concerned and more worried.”

The MERtians are easing the stress by taking in a happy hour here and there, celebrating special occasions together, hanging out and working out. Lever, for example, just held an “all-call” for an evening of diversion at a local karaoke bar. He also began growing a beard the day after the rover shut down to wait out the storm, and will continue to let it grow “until we hear from Oppy or give up trying,” he said.Others who are working more than one mission are turning their attentions to the other project when not working MER. “The thing about JPL that is so sweet – the people,” said Lever. “It’s just such a privilege to work with these people, the cream of the crop of the planet.”

At the end of the sol, the team members are still ‘one for the rover, all for the rover’ and pressing on. It’s garnering them plenty of kudos. “The engineers are doing amazing work,” said Arvidson. “They’re sticking with it and developing plans for recovery assuming we hear from the vehicle. So I give them A+ pluses.”Added Zurek: “It is heartening to watch this team.”

Although this silence from Opportunity could never be considered golden, that’s not stopping the most experienced rover ops team on Earth from having thoughts in those quiet, challenging moments about the prospects and the golden achievement it would be to recover this champion rover. And they’re going for it.

So yes, hope is still floating around MER. “It’s all speculation, but I would say a lot of us are comfortable saying that we’re not going to get too excited until the Tau gets down to 1.0,” said Lever.

Well, the time to get excited arrived at month’s end, on September 30thwhen the Tau came in at 1.0 +/-10% “That is pretty much at the top of the range that MER experienced at this date in past Mars years, Cantor said, “which is basically a hazy summer day on an L.A. beach.”

All Opportunity and this team need now is wind. “If we can just get some dust devils, some gusts of wind to come through and knock this stuff off the arrays, we should be good,” said Staab. “We know if we get above a dust factor of .5 or .6, then we have a good chance, a really good chance of being able to make contact with the rover again. We still have any seven weeks until mid-November when dust-cleaning season starts. We’re working with what we’ve got and we’re just going to keep pushing forward and do the best we can.”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth