A.J.S. Rayl • Dec 01, 2017

The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Returns Fundamental Finding in Perseverance, Cruises Through Winter Solstice

Sols 4896-4925

Opportunity continued the historic winter science campaign inside Perseverance Valley and delivered the goods that confirmed an important discovery in November, and then cruised through winter solstice, driving the Mars Explorations Rovers (MER) mission closer to its 14th anniversary of surface operations coming up in January.

“We conducted a fascinating campaign to acquire one of the most difficult and beautiful microscopic image mosaics in the history of this project,” said MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University. “We got it. And we made a fundamental finding, one that was enabled by some very, very tough driving.”

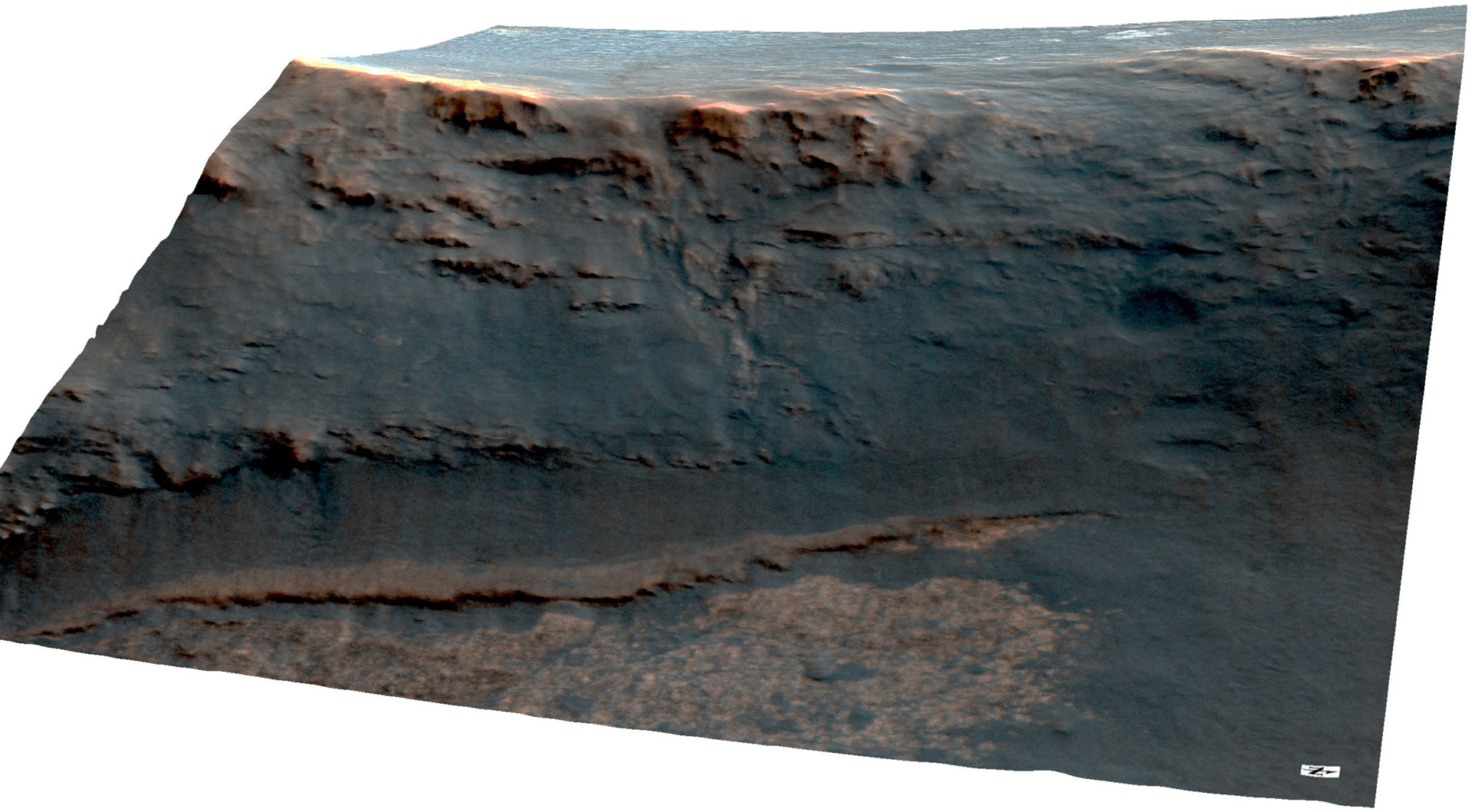

Perseverance Valley, which cuts into the west rim of Endeavour Crater, a 22-kilometer (13.7-mile) diameter hole in the ground, was for years one of, if not the most anticipated geological features, not just of Opportunity’s expedition around Meridiani Planum, but of the entire mission. It was formed billions of years ago sometime after the crater was created, during the Noachian Period, an epoch when planetary scientists generally believe the planet was more like Earth, with lakes, rivers, underground water, hot springs, and volcanoes, and perhaps even an ocean.

Guided by her team of human colleagues on Earth, the robot pressed on through the depths of the mission’s eighth Martian winter in November still on the quest to ‘Follow the Water,’ as NASA directed so many years ago. The robot field geologist is starring as a Crater Scene Investigator in a kind of CSI Mars at Perseverance, sleuthing to uncover ancient clues to find out what exactly carved this unique valley feature into Endeavour’s rim billions of years ago, what formed its braided grooves or channels, and what scoured its outcrops.

Opportunity found signs of near neutral water in remnants of clay minerals in 2012-2013 at Cape York’s Matijevic Hill. Hopes are high that the rover’s forensic findings in Perseverance will uncover critical clues the scientists need to determine how much water was once here and whether it could have fed potentially habitable environments. “We’re doing the same thing we’d do if we were there as astronauts – walking around and looking for evidence,” said MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis. “What we’re after is any indication of process.”

The MER scientists officially are considering multiple hypotheses – from flowing water to a muddy debris flow, ice, ice melting into water, water coming out of fractures, or wind or a combination of these forces – to explain how the valley and its distinctive features came to be. Perched over one of the bright, flat rocks on the northern outcrop of a site the team named La Bajada, the rover scored a small one for wind this past month.

La Bajada features “two different bedrock units in direct proximity” separated by rubbley terrain, “perhaps broken up rock that’s been filled in by sand,” said MER Project Scientist Matt Golombek, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the birthplace of all of NASA’s Mars rovers. While the southern outcrop is darker in tone and lumpy with rocks, the northern outcrop is flatter and lighter toned.

Opportunity shot pictures of the site with her stereo Pancam “eyes” back in August as she drove by it on her way to the next, planned stop. The scientists were struck by what they saw: scouring on some of the northern outcrop rocks, specifically what appeared to be erosional tails, geological signs of an erosive force that seemed to be pointing up hill. “It looks pretty convincing in the Pancam images that these little tails actually are pointing uphill, though I wouldn’t say it was bulletproof,” said Squyres.

Since the favored theory is still that Perseverance itself was carved by water in some form, and since water doesn’t flow up hill, at least not a hill as steep as the grade of this valley, which descends from Endeavour’s rim to the crater floor, these little tails were just too intriguing to ignore. So in the final sols of September, the team decided to have Opportunity back up to La Bajada in October, as reported in last month’s MER Update.

“These erosional tails were the primary reason we decided to drive back up hill,” said Arvidson. “We wanted to really pin these down.” But even for the rover that loves to rove, backing upslope in Perseverance wasn’t easy. Opportunity popped two wheelies in October and struggled to get into a safe position over the chosen scoured rock and a target the team named Mesilla.

“The biggest trouble with this terrain is that it’s very steep,” said Rover Planner Ashley Stroupe, of JPL. Even so, if the scientists were going to effectively solve this scientific puzzle, they needed their robot to take close-up pictures of these erosional tails with her Microscopic Imager (MI) camera.

“Aside from the wheelies, Mesilla also had some gravel on the surface and we were afraid that could cause unexpected sliding,” said Rover Planner Paolo Bellutta, who helped develop the software with which the team charts the rover’s routes. “We needed to be very careful.”

“It was the Battle of La Bajada,” as Squyres called it. “But in the end, the team absolutely nailed it. We have a mosaic that very clearly shows multiple erosional tails pointing up hill.”

Knowing that winds blow up from Endeavour’s floor and through the rim, it would seem that the most likely force that created these tails is wind, as Arvidson put forth last month. Now, with Opportunity’s work in November, there is enough evidence to strongly defend that conclusion.

“Perseverance Valley is billions of years old and it’s been sandblasted through the years, probably by a prevailing wind that’s blowing from the east, up and out of the crater,” Squyres pointed out. “So this distinctive scouring that we’re seeing, we believe, is not related to the original carving of Perseverance Valley, but was something that came along later.”

Significant as this finding is, it reveals nothing about water and nothing how the valley itself was created. Most of the MER science team members remain confident in the early, favored hypothesis that the broader scale topography of the valley, which can be seen from orbit, was carved by water in some form.

Considering that Opportunity is not yet halfway through Perseverance, there is much more to be seen and done before the MER scientists will be able to complete the puzzle of Perseverance Valley. “If we had all the pieces,” said Arvidson, “then we wouldn’t have to go down Perseverance Valley, right?”

With the La Bajada assignment in the can, Opportunity roved on in mid-November, driving back down the valley and onto another north-facing slope or “lily pad,” as the team calls them. There, the solar-powered robot was commanded to tilt toward the north so that her solar arrays pointed toward the Sun. During the ensuing two weeks, the rover soaked up as much sunlight as possible, cruised through winter solstice without batting so much as a Pancam eye.

“We passed the winter solstice on November 20th and power levels have been improving,” said MER Project Manager John Callas. “We’ve had some dust-cleaning events and so there is less dust on the solar arrays, which is helping increase power.”

Opportunity worked through the Thanksgiving holiday, taking as many pictures as possible while most of her human colleagues took a break. Then, the robot trekked farther downhill to another north-facing slope deeper in the valley, stopping about 15 meters away from an area where a large trough splits, a bifurcation zone in geologist jargon. “There’s discussion about what branch of the trough should we take,” said Callas. “We keep quoting Yogi Berra: ‘When you come to a fork in the road, take it.’”

Beyond the MER humor, something else awaits Opportunity. At this bifurcation zone, separating the two branches of the trough, is a mesa or “raised, lozenge shaped area,” as Arvidson described it, that is about 10 meters wide. “It could be a bar. It could be a resistant outcrop,” he said. For now, it is the mission’s next Martian mystery.

Opportunity is slated to drive to the next lily pad in December to get a closer look. From that vantage point, the robot will shoot the images the team needs to decide whether to follow the trough to the north or the south. Whatever the team decides, their field geologist on Mars is ready, willing, and, despite her accumulated signs of aging, still very much able.

“The rover is doing fine,” said Squyres. “Opportunity is in good health and everybody on the team seems to be as well. We’ve got a lot to be thankful for this year.”

Deep Dive into November

When November dawned on Endeavour, winter was putting the freeze on Opportunity’s workload, forcing the robot to use a lot of her energy just to keep warm and carry out the most basic of routine tasks. With the winter solstice arriving in less than three weeks, the team on Earth knew this too would pass. In the meantime, the rover was ‘feeling’ temperatures around minus -96 degrees Celsius [minus -141.01 degrees Fahrenheit], wind chill not factored, the kind of cold that meant the robot would occasionally have to devote entire sols to recharging her battery.

Opportunity had successfully made it to the scientists’ desired spot on the northern outcrop at La Bajada near the end of October, after “a real tough set of drives to get into position on that thing,” said Squyres. “And at the end of the drive, the rover popped a wheelie, the second in a week’s time.”

After performing a maneuver to gently relax her right-rear wheel back onto solid Martian ground on Halloween, Opportunity was in place, over the chosen wind tail target when November began. The team named it Mesilla, after a stop on El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, the old, 2,560-kilometer (about 1,591-mile) trade route between Mexico City and San Juan Pueblo, New Mexico, the naming theme adopted once the rover entered Perseverance.

The first week of November was remarkably productive considering the challenge of the brutal, freezing cold, the rover’s limited power, and a comm glitch that was out of the MER mission’s control.

On Sols 4896 and 4898 (November 1 and November 3, 2017), Opportunity managed to shoot a few Panoramic Camera (Pancam) mosaics of the area to the north, while devoting the sols in between those imaging assignments, 4897 and 4899 (November 2 and 4, 2017) to recharging. The robot took another mosaic of Mesilla on Sol 4900 (November 5, 2017), and placed her APXS on the target, though power did not allow for an integration in the same plan. Then, on Sol 4901 (November 6, 2017), the robot devoted the Martian day to recharging.

The MER ops team planned for Opportunity close out the first week of November on Sol 4902 (November 7, 2017) taking images so the team could plan the next drive – drive direction imagery, as team members call it. But the plan was not sent due to technical difficulties at the Deep Space Network (DSN) station. So without those commands, the rover went into “run-out,” an activity-light extension of the existing master sequence intended to keep the rover in a benign, sequence-controlled state, just in case the next commands don’t get onboard in a timely manner.

Even though Opportunity had to spend half of the first week of November recharging, Mars was “cooperating,” as team members are wont to say. The small gusts of wind that cleared some dust from the solar-powered rover’s arrays in October continued into November. As the second week of the month got underway, the rover was sporting a slightly improved 377 watt-hours of power and solar array dust factor, 0.624, under slightly hazy skies, with atmospheric opacity or Tau recorded at 0.445.

The robot field geologist took advantage of the good numbers. On Sol 4903 (November 8, 2017), Opportunity continued a multi-sol APXS integration of Mesilla. “It looks like regular Shoemaker Formation breccia,” said Arvidson. In the sols that followed, she continued to collect extensive Pancam panoramas for what will be used to create a comprehensive digital elevation map (DEM) of the length and scope of Perseverance.

On Earth, the MER scientists reviewed the images of Mesilla that Opportunity was sending home and, said Squyres, “found “what we were looking for.”

“The little nubbins’ poking up from the outcrop rock with tails of material behind them that had not eroded because they were protected,” as Golombek described them, are “unquestionably erosional tails,” said Squyres.

Some scientists might argue otherwise, Squyres admitted, “But water couldn’t have caused these erosional tails and I think that wind erosion is by far the most straightforward explanation of what we see here.”

Arvidson went further. “We’ve nailed the fact that wind has modified the rocks on the centimeters to tens of centimeters scale,” he said.

The broader scale topography at Perseverance Valley, however, is not what you would expect from wind, Squyres maintained. “Wind erosion doesn’t produce braided channels like we see here,” he said. “So we still believe the original hypothesis of a fluid-carved channel is the correct one for the origin of the topography we can see from orbit. But since whatever erosion took place to form the valley in the first place, Perseverance has been subject to a significant amount of erosional overprinting, if you will.”

With the Mesilla investigation wrapped, Opportunity spent Sol 4906 (November 11, 2017) recharging. The following sol the rover drove 9.09 meters (29.82 feet) to the northeast, with a downhill component, to acquire MI and APXS data on a rock called Durango over the Thanksgiving holiday.

Along the way, Opportunity stopped to look back at La Bajada, taking images that would allow Arvidson, working with the rover engineers, to “sort out all the tracks and all the kind of stumbling blocks that the rover ran into that caused the wheelies,” he said.

“The imaging of La Bajada was taken to carefully examine the terrain to see if we can precisely model all the issues we had during the drives at La Bajada, where Opportunity popped two wheelies and experienced large values of slip,” Bellutta explained. The ultimate objective is to “try and refine a numerical model to precisely simulate Opportunity’s – as well as Curiosity’s – vehicle performance,” he said.

When Opportunity came to a stop on Sol 4907 (November 12, 2017), she was on another lily pad, parked and tilted at about 10 degrees north. Despite the coming winter solstice, with her arrays pointed toward the Sun and with Mars’ helpful little wind gusts, the rover looked to be able to produce the power needed to continue working and roving through the month without so many recharge sols.

The rover has been making tracks pretty well since the MER officials implemented a new drive strategy in June, just before she was to drive into Perseverance. Her right front steering wheel stuck while she was making a turn and although the team managed to get the wheel unstuck, no one wanted to take any chances with the long-awaited Perseverance investigation about to begin. So the robot was commanded to steer only with her rear wheels and turn like a tank and with that, she drove into the valley.

For Opportunity, steering with her rear wheels was just something else to which she had to adapt. “The rover drives now like a car backing up, kind of like a forklift,” said Callas.

The driving actually has been better than one might have expected. It helps, of course, that the terrain inside Perseverance is fairly firm, but it is also steep. So beyond the engineering marvel that Opportunity is, this successful strategy is another testament to the care and extreme, forward-thinking expertise of the rover’s human colleagues and ops engineers.

But there are new challenges, especially in this steep valley and during this season of brutal, bitter cold. Opportunity’s MER mettle notwithstanding, driving down hill has caused a bit of stress on the rover’s front wheels, something Bellutta is bent on alleviating.

“When we are pitched down and driving, there is more weight on the front wheels, and if we try to turn, we can easily get a fault, because it’s stressing those wheels too much,” explained Stroupe. “Basically, the current goes up and the rover faults out. Right now, that’s our biggest challenge in steering with the rear wheels.”

Turning, therefore, is something the MER rover planners now have to consider more carefully. “We’re trying to design the drives to minimize the amount of turning and when we do have to turn, we try to do it in small pieces to avoid the currents getting too high,” she said.

One thing the MER team is not worried about is the impact on the rover’s wheels. “Opportunity’s wheels are incredibly robust compared to Curiosity’s,” said Stroupe. “Remember, with Spirit we dragged that right front wheel without steering it at all, over terrain almost as rugged as what Curiosity has encountered, up hills, over rocks and stuff. At the very last minute, before that winter set in and Spirit went into hibernation, we managed to get that wheel to turn a half a turn and we could see the bottom.”

Believe it or not, after Spirit had dragged her bum wheel over rocky terrain and through sand and silica for years, there was barely a scratch. “So we don’t have any concerns like those we have about Curiosity’s wheels,” Stroupe said. “Our concern is how much we stress the wheel motors and the impact that could have on the motors’ lives. That’s a big concern right now.”

It’s a concern the rover engineers have been and continue to work on. As Bellutta said last August: “We will come up with another rabbit out of the hat to minimize stress to the vehicle.”

Given that the MER team has become famous in planetary exploration circles for their masterful workarounds, it is no surprise that they are already in succeeding to some degree in helping the rover handle the stress.

Other than the new driving issues, the team is focused on making sure Opportunity continues to achieve a decent northerly tilt as she makes her way down the valley and through the rest of this Martian winter. At her new, unnamed lily pad, just northeast of La Bajada, the robot settled in for two weeks of imaging.

In view from the rover’s site just northeast of La Bajada is “one of the main troughs coming from the top and winding toward the middle of Perseverance Valley,” said Arvidson. “We wanted to see what the rocks look like and if there was any indication of erosion on the southern wall of this trough. So we did a lot of imaging at this location. Whether these troughs are water channels or fractures filled with sand remains to be seen.”

By mid-November, the rover’s power had improved a little more, up to 393 watt-hours; solar array dust factor improved to 0.619, under the same slightly hazy skies, with Tau recorded at 0.410.

It was good enough that on Sol 4912 (November 17, 2017) Opportunity woke up via solar power for the first time this Martian winter. “That was pretty exciting,” said Stroupe. “That means our power is on the way up and soon we should be able to start relaxing the requirements for how much northerly tilt we need to have to get good power.”

In October, MER Power Team Lead Jennifer Herman reduced the winter north-facing slope requirements for rover safety, from tilts of 10 degrees to 5 degrees. “But that is basically what it takes for the rover to be safe,” reminded Stroupe. It does not necessarily allow for much extra power to drive or use the Instrument Deployment Device (IDD). “If we can do better than that, then we can keep a better pace for the science activities. We are trying actually to stay about 5 degrees above that 5-degree minimum when we can.”

The winter solstice in the southern hemisphere of Mars finally blew through Meridiani Planum and Endeavour Crater on Sol 4915 (November 20, 2017). The rover passed the sol quietly, recharging. Her power levels that day rose to 401 watt-hours, and her dust factor of 0.628 showed a bit more improvement. The atmospheric opacity cleared a bit with Tau registering 0.404. It was a good sol on Mars.

Empowered, Opportunity got back to work, focusing on a rock the team called Durango on Sol 4916 (November 21, 2017), while most of her human colleagues on Earth were taking leave for the American Thanksgiving holiday. The robot took the series of images with her MI for a mosaic of a surface target, and then placed the APXS on the target for a multi-sol integration to glean its chemical composition.

While the APXS was integrating, Opportunity did a little multitasking, using her Pancam to take more extensive color panorama images of the surrounding terrain. The team will add these images to the databank team members will use to create the comprehensive DEM of Perseverance.

This lily pad turned out to be “a really nice spot for Thanksgiving holiday imaging,” said Squyres. Opportunity’s efforts produced a “fairly sizable Pancam mosaic.”

Meanwhile time – and the Martian winter – have been marching on and good news continued to ride in on the gentle winds. “The power has been increasing a little bit over the last month and a half or so and we seemed to have gotten a little more improvement in recent sols,” said Callas. “We are on an upward trend with a small amount of cleaning still happening every once in a while.”

“Typically the end of winter coincides with raising winds and therefore cleaning events,” added Bellutta, echoing what MER Power Team Lead Jennifer Herman said in the September issue of The MER Update. “This means we usually regain power after winter much more quickly than the loss of power going into winter. While this is good, we really cannot count on this when planning strategically,” he said.

As November wore on, the rover’s energy levels continued to hover between 390 and 400 watt-hours, aided by those small gusts of wind that had been, little by little, whisking dust off the solar arrays, as well as sites that offered a good northerly tilt.

Getting more downlink time with the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) also helped improve MER life on Mars in November. The rover’s mainstay comm orbiter, Mars Odyssey, has for some time now been making the rounds later in the day. With sunset occurring around 5 p.m., local Mars time, and with Odyssey orbiting by usually between 5 and 6 p.m., the rover’s UHF connection often takes place after dark these sols.

Complicating the situation, the best time for Opportunity work, especially to take images, is when the lighting is good, between Noon and about 2 p.m. Since the robot lost the use of her Flash drive or long-term memory a couple of years ago, and has since been working in RAM mode, storing her findings and data in this short-term memory bank, she must downlink each day’s work that same sol. That’s because RAM is volatile memory of course, and once the robot shuts down for the night, the data, which won’t be saved, disappears.

So despite the winter cold, when Opportunity is slated to downlink through Odyssey, the robot has no choice but to complete her work and then stay awake for that orbiter to come and get the data. “That really takes a big power hit on us,” said Stroupe.

The team, as Callas noted previously, has been negotiating for Opportunity to downlink her data a little more often during this challenging season via MRO, which comes by earlier in the Martian day. “I think we are now getting passes every other day, so every other day we don’t have to stay awake as long. We can shut down and go to sleep and not have to worry about waiting for that Odyssey pass,” said Stroupe. “That helped tremendously this past month.”

During the final sols of November, Opportunity finished up the visual survey of the surrounding landscape, taking extensive Pancam stereo color panoramas, as well as the requisite drive direction imagery. Then, on Sol 4922 (November 27, 2017), she drove 14.4 meters (47.24 feet) northeast to the next lily pad down the valley, “toward a split in the valley,” said Bellutta. “The rover’s azimuth was about 70 degrees as predicted.”

The drive bought the rover’s odometer 45.067 kilometers (28.00 miles), another rover record for MER. But perhaps the best news was that the telemetry confirmed that “the steering actuators [or motors] did not suffer and we reached a decent northerly tilt,” Bellutta said.

The plan, as of November’s end, is for Opportunity to drive closer to the head of the trough, the bifurcation zone, in December, image it, and then the science team will have to make a choice: take the left trough or the right trough. “We’ll be looking for erosional features or depositional features like sediment,” said Arvidson

“While the terrain slope and side walls of these troughs should not be too difficult to traverse, we should not count on being able to ping back and forth between these two as it would require large heading changes at moderately high slopes of 20-25 degrees,” said Bellutta. And, while the notion of driving down the middle, on the bar or resistant outcrop or mesa and hopping between the troughs is inviting, ”I don’t think we can traverse through that and still be able to see the details of both troughs,” he said.

With the deepest depths of winter past and an exciting new geological scene ahead, the future is about as bright as it could be 13 years and almost 11 months on an expedition that was to initially have lasted just three months. “We’re past the worst of the winter and so we’re looking forward to power to continue gradually increasing,” said Stroupe. “This valley has been really interesting and we’re getting a lot of stuff out of it. But we’re definitely looking forward to being able to exploring parts of the area that we haven’t been able to look at because they weren’t safe for power.”

It will take time for the scientists to write the story of Perseverance Valley. With many roves to go, there is still much for Opportunity and the MER team to explore and investigate. “And remember, we’ve been drinking through a soda straw, so it’s going to take a long time to get all the data we need to put it all together,” said Arvidson.

In the weeks ahead, Opportunity may be taking the journey down through Perseverance a bit slower. “We’re trying to go down the valley in very small, measured steps,” said Squyres. “The thing about this kind of valley exploration with a rover on Mars is that it’s pretty much a one-way trip down. We don’t want to drive by anything interesting. While we did back up to get to La Bajada. We clawed our way back up slope to get to there. That’s not a process I want to repeat.”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth