A.J.S. Rayl • Nov 02, 2017

The Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Pops Wheelies Over Etched Rocks in Perseverance

Sols 4886-4896

As the brutally cold weather got even colder at Endeavour Crater in October, the depths of winter gripped the Mars Exploration Rovers mission, Opportunity decelerated, and ‘life’ on Mars slowed. But the robot field geologist continued to work on through the doldrums of the season, quietly giving her all to investigating a new site in her historic science campaign inside Perseverance Valley, the most anticipated geological feature in this chapter of the mission’s expedition.

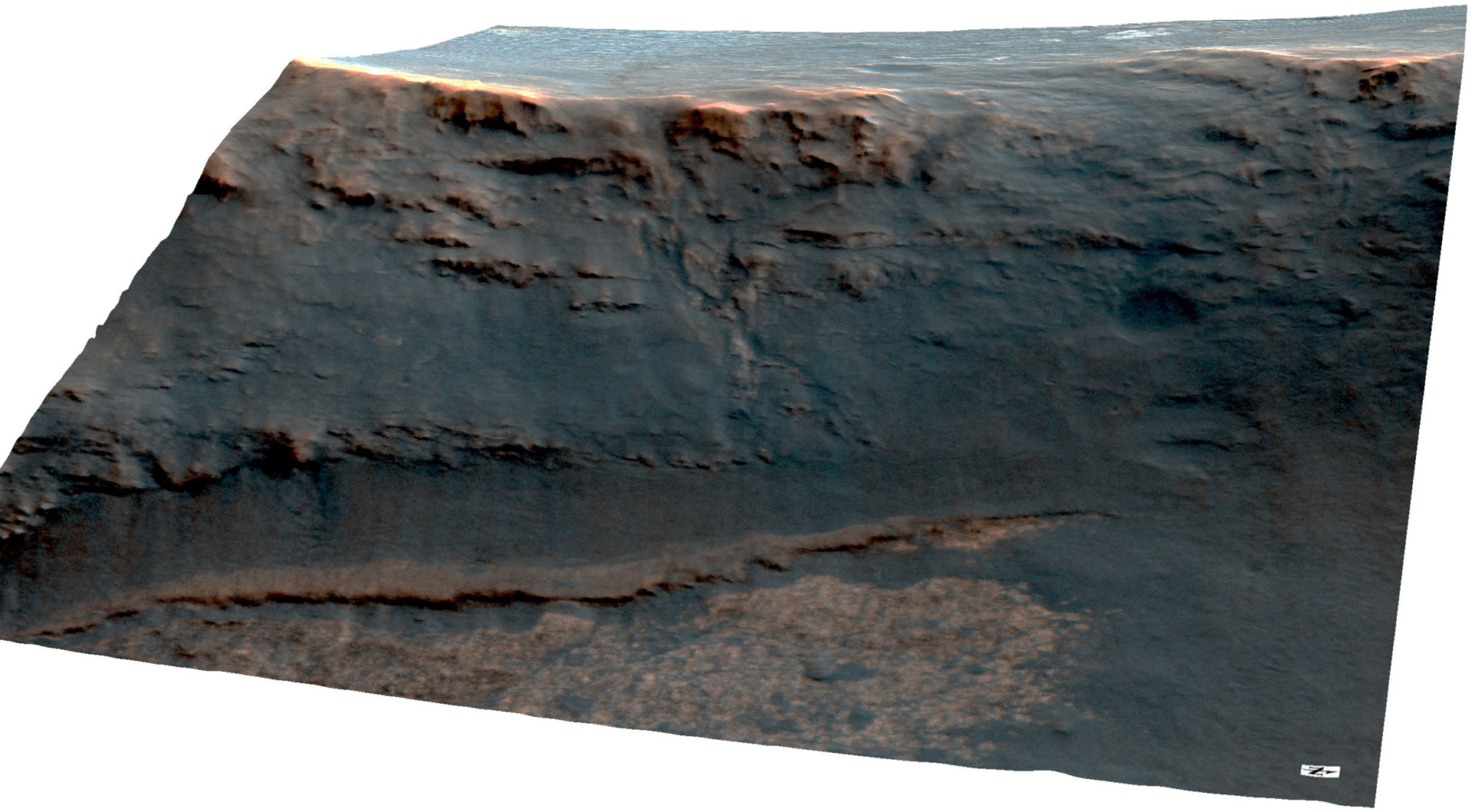

Opportunity is inside this valley that cuts into the west rim of Endeavour Crater to figure out what it was more than 3 billion years ago that caused it to form. The first assumption and still the seemingly favored hypothesis is that Perseverance was carved by water. But the scientists are also floating theories that wind or ice or a muddy debris flow or some combination of those elements could have also done the job.

While the Halloween spirit began to put pumpkins everywhere on Earth, the rover struggled dutifully to climb back up a slippery slope of rubbly terrain in the southern wall of the valley to reach some rocks with mighty little ‘tails’ to tell. In the process, Opportunity surprised her colleagues with a little trick, an October surprise all her own. She popped a wheelie. Boom!

It broke the doldrums of the Martian winter, that’s for sure. Even if the robot had to start the challenge over.

A few sols later, as creatures great and small on Earth took out their costumes of legend and lore in preparation for All Hallows’ Eve, the rover took a new approach on Mars to inch up on the targets. A short, brisk climb it would be – and zip, she made it with aplomb this time. But then Little Miss Perfect, as Opportunity is known in the small circle of Mars rovers, perhaps just for the fun of it, popped another wheelie. Boom! Again.

Opportunity aimed her rear Hazard Camera (Hazcam), freeze-framed her achievement and sent it home. With the day of tricks and treats about to begin on Earth, the veteran Mars rover was on Mars with one rear wheel still “getting air.”

“This is the most difficult driving we’ve done in a long time,” said MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University. “We have some really important science targets and they’re really hard to see and they’re really hard to get to, and we’re just busting our butts getting this done.”

Although the work pace reduced speed and despite the frustrations that popped up in the dreariness of this Martian winter, the team’s sense of humor was never lost. “The rover is just so excited to be where it is,” chuckled MER Project Scientist Matt Golombek, of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), birthplace of all NASA’s Mars explorers.

Maybe she is. Opportunity and her high-flying wheel certainly have quite the view. The rover is positioned at “about 23.5 degrees” on a slope in the southern wall of Perseverance, “with a downhill direction of ~69.5 degrees east-northeast,” said JPL’s Chief of MER Engineering Bill Nelson. So much to see. So much to do.

This is the MER mission’s eighth Martian winter and although experience accounts for a lot, it does nothing to make it any more pleasant. “We’re in the deepest darkest part of the winter,” said MER Project Manager John Callas, of JPL. “And the rover is doing okay.”

As winter months on Mars go, October 2017 may not have been the breeziest, but it could have been be so much worse. Perhaps not to be outdone by Opportunity’s October surprise, Mars delivered a surprise of its own, a gust or two of winds that cleared some of the accumulated dust from the rover’s solar arrays, as MER Power Lead Jennifer Herman, of JPL, had last month hopefully, cautiously predicted might happen. “We've had a little dust cleaning,” she confirmed “And we are hoping for more.”

Considering that Opportunity is entering the 166th month of what started out to be a mission “warrantied” for just three months, the forecast is about as bright as it can get. The day of the least amount of sunshine in this Martian year, minimum insolation the scientists call it, just passed on Halloween and winter solstice arrives precisely at 5:44 Pacific Standard Time November 19th / 1:44 UTC November 20th.” The worst should be behind us in a few weeks,” Callas said.

It was on October 9th that Opportunity backed up the valley and into La Bajada to check out the bright outcrop that lured the scientists to return to the site upslope. “There is something different between the bright, flattish rocks on the northern side and the lumpy, darker rocks on the southern side, so it is probably a geologic contact,” said MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis (WUSTL). “However, we went back uphill because the outcrop on the northern side, the lighter-toned outcrop, had some features that look like they were etched, maybe by winds going up and out of the crater.”

At La Bajada, the rover is not even one-third of the way down the length of Perseverance so Opportunity’s research is still very much a work in progress. “We just don’t have enough information yet to make any slam dunk case for anything yet,” said Golombek.

In all fairness, the rover has quite a ways to go before she complete her journey through Perseverance, and chances are the sites Opportunity will study in the middle of and at the bottom of the valley are harboring richer evidence that will factor into, maybe confirm for once and for all, how Perseverance came to be. “We are open-ended in terms of hypotheses — wind, water, ice,” said Arvidson. “And in October we’ve been documenting how much wind has been involved.”

The notion of past water however remains ever present. “The mantra that NASA has used to describe our mission, to describe a big part of the Mars Program for a very long time is ‘Follow the Water,’” said Squyres. “As we head down Perseverance now, we’re literally doing that.”

And the scientific “hits” just keep on coming. At the Geological Society of America meeting, held October 22nd-25th in Seattle, Opportunity was still a robot star drawing conference attendees and delivering geological news. In well-attended presentations, JPL’s Tim Parker offered up research on the “Geomorphology of the ‘Spillway’ Area at the Head of Perseverance Valley,” while Arvidson summed up the Athena Science Team’s findings at the valley to date in “Orbital and Rover-Based Exploration of Perseverance Valley,” and his graduate student at WUSTL, Madison Hughes, delivered recent research into the “Degradation of Endeavour Crater Based on Orbital and Rover-Based Observations” and the timing and nature of water, wind, and weathering in shaping the crater.

When Halloween finally commanded the calendar, Opportunity had stopped with the wheelie “tricks” and was taking close-up pictures of the mission’s treats. “We popped two wheelies in the space of a week,” Squyres mused. “It’s been pretty crazy.”

Crazy productive, odds beaten. Opportunity got her left rear wheelie down by “rotating the left middle wheel forward causing a torque that brought that rear wheel to the ground,” said Arvidson. The deft maneuver left the robot in perfect position to reach the chosen targets with her Microscopic Imager (MI) and her chemical sniffing Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS).

Most importantly, Opportunity got the scientists to where they wanted to go and spooky as Mars can be any time of year, by the time the ghosts and goblins from around the Universe took to the neighborhoods all around Earth, everything was alright in the world of rovers on Mars. “The key point right now,” said Squyres, “is the rover is performing beautifully as we ask it to do some very complicated things.”

Deep Dive into October

When October dawned on Endeavour Crater, Opportunity was working at station 2 in Perseverance Valley, conducting surface chemistry surveys of the rock named Bernalillo with her Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS).

The ultra cold, low-light conditions of winter continued to limit the robot’s workdays. By keeping her arrays angled to the north where the Sun in the southern hemisphere of Mars rises and sets in winter, Opportunity managed to produce acceptable levels of power. But it gets so cold during Martian winters that the rover has to expend energy to keep warm first and so her science assignments would be limited, as expected.

In fact, Opportunity spent most of the first two days of the month, Sols 4866 and 4867 (October 1 and 2, 2017) recharging.

Sporting energy levels upwards of 285 watt-hours, Opportunity got to work under lightly hazy skies on Sol 4868 (October 3, 2017). The ‘bot then spent the ensuing four sols taking extensive Pancam and Navcam stereo panoramas of the area surrounding station 2, as well as working in a Microscopic Imager (MI) finder frame for an off-set APXS target location on Bernalillo and taking care of all the usual routine operations business.

The rover ended the first week of the month on Sol 4872 (October 7, 2017) much as she began it, taking a Tau and doing little else aside from soaking up the sunlight, and then she began the second week on Sol 4873 (October 8, 2017) recharging.

On Earth, the MER scientists had been scrutinizing the Pancam pictures that Opportunity took as she departed station 1 for station 2 back in August. In those pictures, the MER scientists saw what may be a contact point, where a light and a dark outcrop are separated by a band of terrain, through which the rover had driven. “It looks like it has two different color or tone rocks with this kind of linear soil contact in the middle,” said Golombek.

What drew their interest and attention though are what appear to be tiny wind tails on the bright or light tone outcrop. “They appear to be little directional tails that show which way the erosional flow was going that caused the scouring we see on the bedrock here,” said Squyres. What the rover might find could give the scientists more depth in understanding what happened in Perseverance over the last 3 billion years and how it came to be what it is now.

Given that the slope back up hill is favorable to the winter Sun, the rover’s energy wouldn’t be as much of a concern. More to the scientific point, since these rocks seemed even from a distance to have been scoured by something, there is certainly evidence to be logged that would factor into the story of Perseverance. “So after we finished the work at station 2, the team voted to go back to that bright outcrop, primarily to do MI work to get more of the details of these wind-etched features,” said Arvidson.

On Sol 4874 (October 9, 2017), Opportunity, boasting 45.02 kilometers (27.97 miles) on her odometer, backed upslope 18 meters (about 59.05 feet) in the approximate direction of station 1 to check out the bright, etched outcrop in the presumed contact area. The robot came to a stop on a 25-degree slope with 45.04 kilometers (27.98 miles) on her odometer.

“We are now giving names to the stations and this station is called La Bajada, after a stop on El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro,” said Golombek.

When the robot field geologist entered Perseverance in July, the team decided to adopt this new naming theme and christen targets after stops along the old, 2,560-kilometer (about 1,591-mile) trade route between Mexico City and San Juan Pueblo, New Mexico, known in English as The Royal Road of the Interior Land.

“The thought was to go back uphill to this place, get detailed close ups with the Microscopic Imager (MI), take a lot of Pancam color and twilight stereo images, and look at the chemistry with the APXS,” said Arvidson.

Scientifically, the objective was “to document the erosion” and determine what did the eroding in this particular location,” said Golombek. What Opportunity found was “pretty strong evidence for Aeolian abrasion of the rock,” he said. That is, the surface of the rocks of La Bajada appear to have been eroded by being bombarded with loose particles carried by the wind.

The evidence seemed to be right there, features the geologists believe are wind tails. “You can see them, little nobs and little tails that point in the outflow direction,” said Arvidson. “You have this little nubbin’ poking up and then this tail of material behind it that has not eroded because it’s been protected,” elaborated Golombek. “It’s kind of like a horizontal hoodoo or something, and it’s sort of sculpted, so it’s got a streamlined form. They’re pretty obvious at this location.”

Obvious – and yet new to the MER mission. “We haven’t seen wind tails before until we entered the valley,” said Arvidson. “The first rock we did IDD work on inside Perseverance, Parral, showed little wind tails. Now the outcrops here at La Bajada are showing wind tails at the centimeters to tens of centimeters outcrop scale.”

The rock here in this area of Endeavour’s western rim and inside Perseverance Valley is impact breccia. “It’s made up of a jumbled up bunch of chunks of stuff and some of those chunks are harder than the other materials and so when a little hard chunk sticks up, it’s harder for the erosion to erode it away, and so if the erosive flow is in a particular direction, you can get a little shadow in the down-flow direction from it,” explained Squyres. “You can see a little ridge that points in one direction from these little nobs.”

The MER scientists are “pretty convinced” that they are seeing little wind tails pointing uphill in the Pancam images,” Squyres continued. “Water flows downhill, so if these windtails are pointing uphill, whatever etched these rocks had to be something that was moving in that direction – and we believe that has been the direction of the prevailing winds for a very long time,” he said.

The wind tails, if that’s what they do turn out to be, and the characteristics of the outcrop will confirm that Perseverance Valley rocks have been shaped by winds on the centimeters to maybe the tens of centimeter scale.

Although the wind tails will likely say nothing about the role of water in forming the valley, this ground data will enable the MER scientists to better understand how much of the valley has been shaped by wind, said Arvidson. “Think of a continuum: on one end, the valley is shaped by water, modified a little bit by wind; and on the other end, the valley was formed entirely by wind and we’ve just been fooled because the terrain is highly fractured here.”

To determine where on that continuum Perseverance Valley is, Opportunity and the MER team will continue to look at these outcrops and their shape to see if they have been overall scoured in an uphill direction,” said Arvidson. “This is science, exploration.”

At La Bajada, Opportunity was able to better angle her solar arrays to the Sun in the north, which in turn helped improve her power production to levels above 335 watt-hours. With this bump in power and the team’s increased number of communication links with the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) to downlink daily data, the rover could work, get her data sent down in a more timely manner (rather than having to wait until after dark for the Mars Odyssey orbiter), and retire early. She was also able to avoid having to dedicate any sols to battery recharging through the end of the second week and into the third week of October.

“Earlier this month, we had to pull almost all of the activity because we didn’t have power,” said Golombek. “The power curves are showing that we’re starting up again and we don’t know if that’s because of a small thing or if it’s going to be semi-permanent.”

In any case, the rover spent seven consecutive sols, from 4876 to 4882 (October 11 to 17, 2017), taking Pancam images of the rocky scene at La Bajada and the view from this station, sending home 40 color stereo image pairs. The rover also managed to work in other assignments beyond the routine ops tasks, including an evening atmospheric argon measurement with the APXS on Sol 4876.

“Power has improved,” said Callas. Actually, as Opportunity wrapped that imaging assignment, her power production went up another 25 watt-hours, upwards of 355 watt-hours.

Although Mars historically has gifted the MER mission with dust-cleaning gusts around this time of the Martian winters, as Herman noted in the last MER Update, she is not entirely convinced it was because of wind this time. “I don't know yet the cause of the dust cleaning – may be wind or may be due to motion,” she said. The rover had just driven backwards uphill.

During the third week of October, Opportunity attempted to drive a little bit farther upslope onto the northern part of the bright outcrop at La Bajada on Sol 4883 (October 18, 2017. “It’s a move the robot needed to make “to get to the targets we were trying to get to,” said Squyres, and to get her IDD over those targets.

“We planned to put the vehicle in a location where we could get the MI down on some of these wind tails and do APXS,” said Arvidson.

But the terrain was steep and slick with rubble, and the going was tough for Opportunity. “It was like a 1.5-meter (about a five-foot) plan, and the rover went 10 centimeters (3.93 inches), and then stalled out – and popped a wheelie,” said Arvidson. “A major wheelie. It put the rover’s right rear wheel in the air and the vehicle in “an untenable situation,” he said.

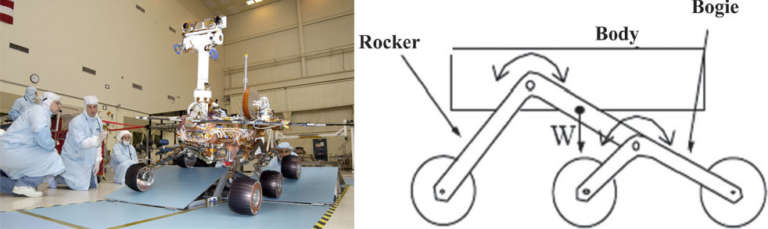

When Opportunity “pops” a wheelie, either a middle wheel or a rear wheel lifts up and off the Martian ground. To understand how that wheel gets ‘air,’ it helps to understand the basics of the MERs’ suspension system.

Opportunity and twin Spirit feature an ingenious chassis design that incorporates wheel bogie assemblies on rocker arms. Dubbed a rocker-bogie suspension, it was invented by renowned JPL engineer Don Bickler, who for years led the Advanced Mechanical Systems Team at the Lab. This design, U.S. Patent 4,840,394, was used successfully on Mars for the first time on Mars Pathfinder’s Sojourner and currently, in addition to Opportunity, the Mars Science Laboratory’s Curiosity also rolls on a rocker-bogie suspension system.

The term "rocker" comes from the rocking aspect of the larger links on each side of the suspension system that connect to each other and the vehicle chassis through a differential. This design enables rovers to "rock" up or down depending on the various positions of the multiple wheels.

One end of the rocker is fitted with a drive wheel and the other end is pivoted to a “bogie,” a term long used to describe a train undercarriage with wheels that can swivel to curve along a track. On the Mars rovers, the bogie refers to the links on the suspension system that have a drive wheel at each end. Basically, the rocker connects the rovers’ front wheels with a pivot on the bogie, which connects the middle and rear wheels.

All the Mars rovers have two fixed middle wheels, and four steering wheels, two in front and two in back. The steering wheels each have individual steering motors that allow the vehicles to turn in place, a full 360-degrees, and also swerve and curve, kind of like a train, making arcing turns.

This “unsprung” rocker-bogey suspension reduces the motion of the main MER vehicle body by half compared to other suspension systems, according to JPL data. Additionally, the suspension allows for exceptional mobility, enabling the rovers to travel over the Martian hills and dales, drive into craters and scale small mountains, as well as efficiently climb over rocks larger than their wheel diameters and, most importantly, do it all safely.

Wheelies, as Opportunity typically “pops” them, can happen in a few different ways, but they all require the wheel on the bogie that stays in contact with the surface to make substantially more or less progress than the other four wheels in contact. “Knowing this, we can ‘induce’ wheelies if needed,” said RP Ashley Stroupe, of JPL. “For example, we have considered lifting one of the wheels to help improve northerly tilt to improve power in the winter, but fortunately we haven’t had to resort to that.”

“A wheelie is not inevitable, but is at least a plausible outcome of some of the maneuvers we were trying,” said Squyres.

The causal hypotheses were the usual suspects: the rubbly terrain and angle of the slope. Whatever the cause, they needed Opportunity to put all her wheels on the ground.

“The rover [was] not in an unsafe position,” RP Paolo Bellutta assured. “Except it’s winter,” said Arvidson, “and we were tilted east, and we want to be more northerly.” In other words, the team needed Opportunity to move sooner rather than later so the solar-powered rover could reposition herself to the north and take in more sunlight.

On Sol 4885 (October 20, 2017), Opportunity worked with the commands from the MER ops engineers to "flatten" her suspension. The robot turned the middle wheel to drive away from the pivot point. This allowed the force from the rocker on the bogie pivot to push the bogie downwards. As a result, the rear wheel lowered to the ground. “This typically takes a-half-to-a-whole wheel rotation,” said Nelson. Opportunity then drove downhill 3.27 meters (10.72 feet), bringing her total odometry to 45.039 kilometers 27.98 miles), completing the “recovery” of her high-flying wheel.

There was good news that spread via email among MER team members on October 24, 2017). It was official: Opportunity had a dust cleaning or perhaps a series of little lifts with a cumulative noticeable impact.

The MER scientists meanwhile stayed focused on the wind tail features at La Bajada and wanted Opportunity to get up close enough to them to do an in-depth examination. So the ops team regrouped to contemplate a new approach for their field geologist.

“We’re in Perseverance Valley, a feature that on the large scale we suspect was carved by flowing water in some form, maybe a debris flow, maybe a stream, we don’t know,” said Squyres. “But when we look at it at the fine scale, when we look at it really close up, we see this pervasive parallel grooving that runs in the uphill-downhill direction. Because it runs uphill-downhill, you look at this and think, ‘Is this the result of water flow coming from the east, or something else?’”

To answer that question, the team needed for Opportunity to get to these tiny features. “We have seen them abundantly in Pancam images, but they are so tiny — millimeters in size — and are very difficult to image with Pancam,” said Squyres. “Our tool for investigating these kind of very fine-scale textures is the Microscopic Imager and so the plan was to get the MI on these features,” he said.

“This [research at La Bajada] is fundamental to understanding the nature of the erosion that has taken place at Perseverance Valley,” said Squyres.

That’s why Opportunity was spending the time and energy on this slippery slope.

“If you believe the fine-scale scouring is the result of downhill flow of water you can some to conclusions very different than if you believe it’s due to uphill blowing wind,” Squyres pointed out.

The science team is “just about convinced” that these wind features are revealing that the fine-scale grooving, the scouring that we are seeing in the valley was actually “caused by wind that came much later,” Squyres said. “It kind of overprinted the original erosion [and carving] of the valley. But we want to be able to prove that so it stands up to peer review. We want to really nail this issue and do it in a way that is definitive. If we’re right about this all it says is don’t interpret these grooves as in terms of flowing water, because that ain’t what did it,” he said. “If we’re wrong, then the MI pictures might show us that too, so we’ll see.”

From her location about 3 meters downslope from the cluster of wind tail targets on the bright outcrop at La Bajada, Opportunity put it into gear on Sol 4890 (October 25, 2017) and climbed back up the slope. She managed to put 4.18 meters (13.71 feet) in her rear view mirror before she stopped, her odometer clicking up to 45.044 kilometers (27.98 miles).

Success! The robot field geologist pulled up into the perfect position on the outcrop with “a beautiful one of these features we think is a wind tail right within reach of the arm,” said Squyres. And – she popped another wheelie. This time, the left rear wheel.

“It’s up in space,” Golombek said, deadpan.

“Mars is making our life hard,” reported RP Paolo Bellutta.

Or it could be that Opportunity is just putting a mechanical exclamation on the point.

Either way, the vehicle is “perfectly stable,” assured Bellutta. However, he added: “It makes a bit tricky to use the IDD in this configuration.”

That of course would be out of the question. “None of us wants to try start waving the arm around with one wheel in the air,” said Squyres. “That is not a prudent thing to do with a half-billion-dollar rover.”

So the MER ops team spent all day Friday, October 27th trying to figure out a way to unwind the wheelie without moving the vehicle. “We’re trying to get all six wheels back on the ground and still have that target we’re after still be in reach,” said Squyres. “And we’re on very steep terrain and unwinding the wheelie without moving the vehicle is not an easy thing to do, so we wanted to have a lot of eyes on the screen, a lot of eyes on the code and everybody taking their time and thinking it through carefully.”

It was a long, long and particularly challenging day.

The plan, as always with rover wheelies, was to "flatten" the suspension. But the rover would not drive or do much of anything else because limited power. And the MER scientists didn’t want the rover to move, because she was ideally positioned to begin close-up research on an ideal target.

The RPs would have the difficult task of adjusting the position of the vehicle after returning the left rear wheel to the ground. “Very accurate maneuvers are always quite challenging, even a tiny pebble can make a big difference,” said Bellutta.

That task was slated for the final weekend of October. It was a simple plan: undo the wheelie on the right rear wheel on sol 4893 (October 28, 2017), rest and recharge. During the final sol of October, as ghosts and goblins donned their finest and began to hit the streets and cobblestone roads here and there on Earth, Opportunity will focus on wind tails at La Bajada.

On Earth, the MER scientists are working the working hypotheses and things are evolving. Remember talk of a possible lake or catchment in previous editions of The MER Update, to the west of Endeavour’s west rim?

Well, scratch that.

“Never existed,” said Arvidson. “There was not a big lake to the west. There is not a source of water coming to the rim from the west. We have now finished all the calculations and demonstrated that you just can’t have anything to the west that would produce a local lake.”

Whatever water was involved had to be local. It had to come from right there, right at the rim crest, Arvidson proffered. “I think what is clear now, from all the analyses that we’ve done, is that any water that was involved in making Perseverance Valley would be local, and that’s a take-home point.”

So what local source off water could there have been?

How about ice? Packed on the top of the rim?

In coming weeks, Arvidson and planetary geologist and geophysicist Mike Mellon, a Mars ice expert at the Applied Physics Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University who worked on the Phoenix mission, are planning to make a thermal model of the Perseverance area. By taking the surface temperatures in various locations to the north, south, east, and west of Perseverance Valley, they will be looking to see if the valley gets “preferentially cold as a result of the planet’s spin axis” and/or “to see if it preferentially accumulates frost or preferentially freezes ground water that would be coming up along the fractures,” said Arvidson.

While the MER scientists have found the evidence that clearly shows wind modified the rocks at the centimeter to tens of centimeter scale, the question remains: what produced the overall shape of the valley and the shallow ‘channels’ extending from the top of Perseverance to the west?

“The evidence from our walkabout on top of Perseverance and having this trough or so-called ‘spillway’ in that top area leading directly to the valley is fairly suggestive that water was involved,” said Golombek. “Certainly the anastomosing pattern is consistent with water being involved. But the actual channel, if you want to call it that, or the trough, is so subtle that we’re just not seeing much there. Certainly not enough to say one-way or another what’s happened in this exact location. So far, no smoking gun.”

It may be a complicated set of processes that brought Perseverance into being and to its current state now, perhaps involving fluvial action along with other forces. Or, there are rumblings that Perseverance could have been created by a one-time, singular event.

“The fact that this is not a super entrenched, deep channel suggests it may have been this one-time erosional thing that occurred and then not much has happened before or after,” said Golombek. “That’s a possibility. We just don’t have a slam dunk case for anything yet.”

Interestingly and perhaps not at all surprisingly, most all the rumblings, whether of a complicated series of processes or of a singular one-off event, still suggest water was involved and likely integral in carving the valley. The smoking gun could be waiting for Opportunity farther down, toward the bottom of the valley in deposits at or near the floor of Endeavour.

“These potential deposits would tell us whether water is involved or not,” said Golombek. “If we can find and interrogate and look at these deposits — there are ‘fingerprints’ left various events — we ought to be able to decide if it was a debris flow versus clear, flow of water.”

All that noted, Perseverance is really, really ancient, dating to the late Noachian Period on Mars more than 3 billion years ago. All kinds of things could have happened here in over the millennia. “That, the idea that Perseverance is Noachian, gives some people queasiness,” said Golombek. “But there are two or three strong pieces of evidence that suggest the formation of Perseverance likely did occur during the late Noachian.”

One is that the entire Meridiani area experienced quite a bit of water erosion in the late Noachian Period, something that is fairly well documented in topographic analyses. The second is that in the HiRISE image of the valley itself, the anastomosing channel goes down this valley and then disappears at the contact with the Grasberg Formation. On top of Grasberg is Burns “and the channel never shows up there as either,” Golombek pointed out.

That suggests that the erosion or event that carved the valley occurred prior to both of the Grasberg and the Burns Formation strata being deposited, which scientists suggest happened during the Hesperian Period. And that is consistent with the valley being late Noachian.

The conundrum is: how come we still see it?

“How come it hasn’t been smushed to smithereens by subsequent impact?” asks Golombek. “The whole thing is so subtle when we’re there, really shallow slopes, probably less than a meter deep. Probably the signal-to-noise in the HiRISE images is so good that we are seeing these incredibly subtle variations in the scene that we almost cannot see on the surface. The topography in the HiRISE, the digital elevation models, are just not good enough though to resolve the individual channels that we’re seeing on the ground. That you get from higher resolution.”

Time and more imaging and more research will no doubt unleash more Martian secrets.

Meanwhile, Opportunity, on command, unwound her wheel gracefully and put it back on the Martian ground at La Bajada, and then spent All Hallows’ Eve taking close-up pictures of tiny little wind tails on the bright outcrop rocks with her MI. The rover and her handlers made it look easy.

As the calendar turns to November, Opportunity is scheduled to analyze the chemical composition of the wind tail(s). Once her work at La Bajada is done, likely within the first week of November, “we’re going to boogie back down the valley,” said Nelson.

Although Bellutta and the RPs, with the input of the scientists, have charted a tentative route down Perseverance, this is and forever will be a science-driven mission. And, given the rover is on a hill and “you can only see about 20 to 25 meters ahead,” as Bellutta pointed out, choosing the next station is a collaborative MER effort.

“The stations are placeholders,” said Arvidson. “When we’re ready to head downhill, we make stereo maps showing the next lily pad, and then we then pick out a lily pad that looks the best in terms of getting to it without incident, in terms of tilt and in terms of imaging and IDD work.”

The slow pace of winter may be a bit annoying for some of the team members and the legion of humans on Earth who are still onboard the expedition, but it’s better than the alternative of the rover having to just park for winter. “We’re doing the best we can under really, really challenging circumstances,” said Squyres. “It would have been nice if Mars would have cooperated and we would have arrived at Perseverance at the beginning of [the Martian] summer. It didn’t work out that way.”

So the MER team must keep an eye on their rover’s energy, though that comes with the territory of winter and the outlook is good this winter shall pass soon. “We have to be very mindful of northerly tilts,” Squyres said. “The energy boost [this month] helps,” acknowledged Herman. “But I am still recommending at least a 5-degree northward tilt, revised down from 10 degrees, until winter solstice on November 19th.”

Undaunted as usual, Opportunity was keeping her focus on the work and the road ahead as November marks another new beginning.

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth