A.J.S. Rayl • Nov 04, 2014

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Images Comet, Ducks Storm, Departs Ulysses

Sols 3800 - 3829

As winds whirled and converged to the west of Endeavour Crater, spewing rust red dust upward and obscuring the skies, Opportunity's power dropped dramatically in October, but the Mars Exploration Rover (MER) pressed on. By month's end, the robot field geologist had completed her assignments – including capturing the first close-in shot of a comet from the surface of the Red Planet – and was roving onward through the darkness, driving the mission into the 130th month of what started out more than 10-and-a-half years ago to be a 3-month tour.

The veteran Mars rover spent most of October on the western rim of Endeavour, studying the "somewhat different" rocks hurled up by whatever impacted Wdowiak Ridge's southern end and carved out the small crater called Ulysses there. As important as the robot's work-a-sol science is to understanding the bigger picture of Mars' past, the picture of comet Siding Spring and the menacing regional dust storm proved to be the big stories of October 2014.

In years past, Opportunity and her twin, Spirit, tried to take pictures of comets without success. But in mid-October 2014, comet Siding Spring would zoom in closer to Mars than any previous known comet flyby of Mars or Earth and the prospects of Opportunity being able to freeze-frame the iceball would be better than ever. So, over the past year, a team of MER scientists, led by Mark Lemmon, of Texas A&M University (TAMU), considered and calculated the timing and positioning of the rover, and in October would conduct preliminary tests and a dry run.

"This is something that we never planned at the beginning of the mission, something that we thought we'd never have the chance to do," said Lemmon, an atmospheric scientist and associate professor at TAMU, who coordinated Opportunity's precision comet shoot. "It's excitingly fortunate that this comet came so close to Mars to give us a chance to study it."

Besides Opportunity, NASA Mars orbiters – Mars Odyssey, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), and MAVEN – as well as the Curiosity rover and other assets in space and on Earth are also studying the comet that is making its first visit this close to the Sun from the outer solar system's Oort Cloud. The hope is that this concerted campaign of Sliding Spring observations will yield fresh clues to our solar system's earliest days more than 4 billion years ago.

During the wee hours of October 19th, Opportunity snapped away slowly from her Martian stage near Ulysses Crater for nearly 30 minutes, taking long exposures, ranging from 10 seconds to 50 seconds. When the first of the images came streaming to Earth, the rover delivered several suitable-for-framing images of the comet, dead center in a few frames, against a backdrop of a pre-dawn Martian sky, no special effects or processing needed. "We got it," said Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell University.

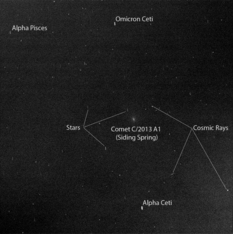

Comet Siding Spring

"Isn’t that cool?" asked MER Principal Investigator Steve Squyres, of Cornell University, several days after the images Opportunity took of comet Siding Spring streamed down to Earth. This two-image blink shows a comparison of two exposure times in images from the panoramic camera (Pancam) showing comet C/2013 A1 Siding Spring as it flew near Mars on Oct. 19, 2014. The veteran rover took the images about two-and-a-half hours before the closest approach of the comet's nucleus to Mars when the sky was still relatively dark and before Martian twilight turned to dawn. The duration of the exposure resulted in a 2.5-pixel smear from rotation of Mars.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / TAMU

It was a first. No other robot has ever taken a picture of a comet from the surface of another planet. "It was a hard, hard observation and I am very proud of the team for pulling this off," Squyres said.

Although the images are hardly the most spectacular comet pics, the special thing about Opportunity's images of Siding Spring is obvious and it touches the heartstrings of every explorer. "The images Opportunity took show us what we would have seen if we had been there," said Lemmon. "It’s that knowledge that makes them such interesting pictures."

The comet pictures also enabled the aging rover to once again show her MER mettle. But even as Opportunity was snaring the images of Siding Spring and making a little more history for MER, a number of dust storms that had blown down from the north, riding the Acidalia storm-track across the Martian equator, had joined forces to the west of Endeavour and merged into one large regional storm. The atmosphere was getting thicker with dust by the sol, and the skies over the rover had already begun to "rain" some of that dust back down, depositing who knows how much of the rusty red powder on the rover's nearly clean solar arrays. In just a couple of weeks, Opportunity's power would drop nearly by half.

The storm wasn't exactly a big surprise. The Martian springtime is the season of dust storms and dust devils and Mars is infamous for its planet circling storms that from time to time completely blanket it with a shroud of the insidious powdery stuff. Although Opportunity survived a planet circling dust storm in June-July 2007, she was not designed to withstand a Martian dust storm and the rover doesn't necessarily have to be in the middle of a storm for its robot-life to be threatened. While the storm in October was well to the west of the rover, it was big enough and close enough for the rover to seriously feel the effects – because' its all about the dust.

"There always is a concern about dust storms," said John Callas, MER project manager, at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), home to all NASA's Mars rovers. "These storms kick up dust and eventually that dust comes back down. It's kind of like trying to clean your house with a leaf blower. We are seeing more dust falling out of the air now."

Despite her continued power drop, Opportunity was still producing approximately 1/3 her full capability near month's end, plenty enough power to continue driving, said Bill Nelson, chief of MER engineering at JPL. But the plan for the rover to hightail it away from Ulysses and Wdowiak Ridge and hit the road for some serious distance driving once her work in the crater's ejecta field was done had to be tempered.

"Our pace was slowed down considerably because of the dust situation," said Squyres. "We are working our way away from the crater, but we're moving slowly – and we continue to monitor the storms very, very carefully."

For the last several months, Opportunity has been following a fairly direct path to its next big destination, Marathon Valley. Now as November begins, that destination is only 1250 meters (about 0.77 mile) to the south. It's where a varied and abundant mix of clay minerals – sure signs of past water – have been spotted in orbital data taken by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), a visible-infrared spectrometer aboard MRO searching for mineralogic indications of past and present water on the Red Planet.

Clay minerals, in particular the smectite clays detected by CRISM, are hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates that form in the presence of near-neutral or more alkaline water. More intriguing, clays star as key players in various scientific theories on abiogenesis, the emergence of life on Earth, the only place in the universe known, so far, to harbor life.

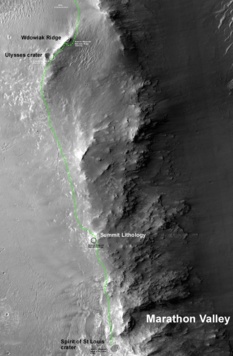

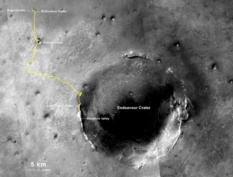

Opportunity's path south

Opportunity's planned route south to Cape Tribulation and Marathon Valley is charted here in green. As October 2014 came to an end, the rover had departed Wdowiak Ridge and Ulysses Crater, where it has found an intriguing diversity of rocks. The rover has now embarked on the "long haul," as MER Deputy PI Ray Arvidson calls it, to the area marked Summit Lithology, the next intermediate stop on the journey to Marathon Valley.NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / NMMNHS

Quietly, hope springs and the Martian plot thickens with musings that maybe, just maybe the clays Opportunity will uncover in Marathon Valley will hold long hidden evidence of more than a habitat but a life, however tiny, that lived long, long ago on this planet so far from and yet so close to Earth.

As the only robot traversing the most ancient Noachian Period landscapes, the time when Mars is thought to have been more like Earth, there is still so much more for Opportunity to discover – and it's just waiting down the rim apiece. Yet "dust is extremely dangerous to a solar-powered rover because it's life-threatening," the late Jake Matijevic, one of the Mars rover pioneers at JPL, told the MER Update back in 2007.

Dust is what the MER creators years ago assumed would "take out" the robots, because it would limit and eventually block access to the sunlight solar-powered rovers need for "fuel" to carry on. Actually, the accumulation of dust on Spirit's arrays may well have been the primary cause of that rover's demise in March 2010. We may never know. One thing that the MER team has experienced during the last decade however is that what Mars deposits, it also lifts away.

Opportunity has lived long and prospered for more than 10 years on Mars, and Spirit for seven years, mostly because of the wind gusts and dust devils that blew by from time to time to clear the rovers' solar arrays again and again and again. It's all up to Mars – or just plain luck – as to what happens when.

During the last Martian winter at Cook Haven, MER's sixth winter of surface operations, Opportunity found herself in a "scour zone," as Ray Arvidson, MER deputy principal investigator of Washington University St. Louis, described it. When she emerged from that winter in March-April of this year, the robot was pretty much clean as a whistle. Not anymore.

"We didn’t take a direct hit, but we saw significant increases in the amount of dust as a consequence of this storm," said Squyres. In fact, Opportunity's measurement of atmospheric dust, called a 'Tau,' pushed over 2, which is darker than the worst pollution days in Beijing and the highest Tau this rover has measured since the global event in 2007 that sat on her and threatened her robot life.

And it’s one of the highest Taus recorded during this mission. "Atmospheric opacity levels like this have not been seen since August 2009, about 1 Mars year after the global storm, when Spirit suffered dust darkness "approaching the ballpark of 3," recalled Lemmon. "Spirit's Tau reached 2.74 at that time, and was above 2 for Sols 2005-2009," he elaborated.

Remarkably, Opportunity remained in generally good health throughout October despite the storm – and three more bouts of amnesia and an unexpected reboot. The amnesia events, where the rover's computer fails to mount her Flash memory before she shuts down and goes to sleep at night, and the sudden, unexpected reboot, are the same issues the rover had before a Flash reformat was done in September. "We didn't lose any science," said Nelson, "and none of them really affected operations or the rover's health."

Still, theses glitches are a concern, especially given the recent reformat of that drive. In addition to reformatting again, the MER ops engineers made progress in October on possible responses and workarounds to these continued Flash issues. "We do have a couple of arrows in our quiver and we can use them as we need them, if we need them," said Callas. "For now, we can live with this."

Once the dust storm ceases to be a threat, Opportunity's pace will pick up, said Squyres. "We’re going to pretty much make a beeline to Marathon Valley. Obviously, if there are significant science opportunities along the way, we’ll take advantage of them. But Marathon Valley is the next big stop. No question."

But as October turns to November, the dust storm still has the attention of the MER team. The MER team is getting "regular updates," Callas said, from Bruce Cantor and the Mars Color Imager (MARCI) team at Malin Space Science Systems (MSSS) in southern California. [MARCI is a camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter that the team is using to take pictures used to monitor the planet's weather. It observes the entire planet every day at 5 visible and 2 ultraviolet wavelengths.]

The storm appeared to be starting to weaken, Cantor told the MER Update at presstime. "But the Martian atmosphere is very dynamic and dusty at this time," he cautioned, "so any additional perturbation in the next few sols, say from another regional dust storm coming south along the Acidalia storm-track and across the equator into the southern tropics, could reinvigorate the storm activity into possibly something much larger."

"We’re doing okay," said Squyres as All Hallow's Eve unleashed some "fright" on Earth. "But we're not out of the woods yet."

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

Ulysses Crater ejecta field

Opportunity took this image with her Panoramic Camera (Pancam) just as October 2014 got underway. It shows the diversity and number of rocks that the robot field geologist spent the month maneuvering around and studying. This image was processed by the Pancam team in false color, which gives the MER scientists a way of better distinguishing differences among the rocks and other parts of the terrain.October 2014 began calmly enough. When the month dawned at Endeavour Crater, Opportunity was in the midst of a close-up look at a fine-grained rock called Lipscomb, just outside Ulysses Crater at Wdowiak Ridge, along Endeavour's western rim.

The plan called for the veteran robot field geologist to examine a few rocks representative of the diversity in the ejecta field of Ulysses, the small, approximately 30-meter diameter crater that is sunk into the southern portion of Wdowiak Ridge, and then get back on the road and do some serious driving south to Marathon Valley. "It was kind of business as usual," said Ray Arvidson, MER deputy principal investigator, of Washington University St Louis.

The robot field geologist was also preparing for her forthcoming attempt to image comet Siding Spring. The rover's stereo Pancam lenses are, effectively, the rover's eyes. Still, pointing those eyes at something in the sky that moves during the day or night from the surface of Mars is tricky. "We’d analyzed this quite a while back and identified about +/- one week around the comet's close approach when conditions would be good for us to get the image," said Lemmon. Eventually, they went all in on the date of the comet’s closest approach to Mars, October 19th.

Wdowiak Ridge - Ulysses Crater

This overhead view taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) shows part of the western rim of the 22-kilometer diameter Endeavour Crater, on the right, and Wdowiak Ridge and Ulysses Crater at the ridge's southern end, toward the left side of this image. Opportunity spent the month of October 2014 studying a sampling of diverse rocks she found in Ulysses' ejecta field, taking a picture of comet Siding Spring and waiting out a potentially deadly dust storm.NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA

As Siding Spring's arrival date got closer, Lemmon scheduled various tests and the team even held a dress rehearsal. The first test took place in the evening hours of the rover's Sol 3799 (October 1, 2014), when Opportunity took a series of images with her Pancam to see how bright the twilight was, and to see the exact position of the Sun. Assuming the comet would be performing according to its predicted brightness, they defined "with pretty high confidence" a time window during the middle of Siding Spring's close approach time when Opportunity might actually be able to see it.

The following sol, the robot field geologist got back to work on Lipscomb, beginning her inspection of a curious flake or rind on the rock that the team dubbed Victory. Using the instruments on her Instrument Deployment Device (ID) or robotic arm, she first collected the pictures needed for a Microscopic Imager (MI) mosaic, and then placed her Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer (APXS) near the flake to measure its elemental composition. Two sols later, 3802 (October 4, 2014), she repositioned her APXS Victory for a second integration and analysis.

"There was a lot of variety in terms of the appearance of the rocks in Ulysses ejecta field," said Squyres. "There were a number of rocks that showed this sort of continuous surface material that sort of looked like flakes or exfoliating portions of the rock. We wanted to determine how those formed and if they really different from the underlying rock or if they're just a weathering process."

The next sol, the rover drove over Lipscomb and turned around to face the other side and on Sol 3805 (October 7, 2014), she bumped a little more than a meter to get closer to a target spot on the rock that the team nicknamed Margaret. "It’s a pretty small rock, so in order to brush it, we went around to the other side," said Squyres.

Opportunity spent the second week of the month trying to get close to Margaret and preparing for Siding Spring's close approach. In another preliminary test, the rover took another late evening set of Pancam images on Sol 3806 (October 8, 2014).

The next sol, the rover bumped 13 centimeters (5 inches) to get off of some small rocks under the wheels. But in images Opportunity sent home on Sol 3809 (October 11, 2014), there looked to be a small rock underneath the left front wheel that might cause her to shift if she pressed her arm against a surface target for a Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT) brush.

To test that possibility, the rover engineers commanded Opportunity to conduct a basic set of MI mosaics and an APXS placement but without making actual surface contact, and then prepare the RAT for use, also to see if the rover was stable. She was. So the robot got the green light to proceed with a RAT brush of Margaret at Lipscomb on Sol 3812 (October 14, 2014).

But first, on October 12th, one week before Siding Spring's close approach, the MER team conducted its dress rehearsal. Nothing would be easy for Opportunity. "The comet had not brightened as much as expected and was therefore about a factor of 5 fainter than expectations," said Lemmon. "On top of that, the dust storms passing to the west of the Opportunity site were putting a bunch of high altitude dust in our air."

Margaret

Opportunity used her Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT) to brush this spot, called Margaret on the rock dubbed Lipscomb during her science research in October 2014. The robot field geologist spent much of the month checking out the various rocks hurled up by whatever hit the Martian ground and created Ulysses Crater at te southern end of Wdowkiak Ridge. The scientists found an intriguing diversity among the rocks, or crater ejecta as geologists call them, and found them to be "a little different," than other rocks the team has studied on Endeavour's rim, as Ray Arvidson, MER deputy principal investigator, put it. The MER scientists are still looking at the data. This image was processed by the Pancam team in false color.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

The preparations paid off and the mission lucky star was shining, because the dry run was just about perfect. The comet, while not yet visible, was in the pictures geometrically as seen by the presence of nearby stars. What wasn't perfect was the twilight. "It was significantly brighter than predicted by the previous tests and so the comet was there but it was not bright enough to see, because the twilight was that bright," Lemmon said.

Comet Siding Spring was racing in-bound from a much greater distance than it would be during the "real" photo-op attempt, but the main purpose of the dry run was not to see or image the comet. Rather, it was to test the entire system and everything worked. Lemmon and his MER colleagues took the knowledge learned in the rehearsal, along with everything else and fine-tuned the timing and the positioning of Opportunity's Pancam "eyes."

In the meantime, Opportunity was beginning to feel the effects of the now regional storm raging to the west. The rover has started the month producing levels of power hovering around 630 watt-hours, but by the middle of the month had lost a good 25 watt-hours and the Tau or atmospheric opacity was steadily increasing.

The good news was that the robot made it through the first two weeks of the month with no Flash memory-related anomalies, which had been occurring in recent months and which had gotten so bad in August that the MER team had the rover reformat that drive in early September. That was about to change.

After Opportunity successfully brushed Margaret on Sol 3812 (October 15, 2014), she collected another MI mosaic and placed her APXS down on the spot for a multi-sol integration. On that evening of Sol 3812, however once the APXS observation was done, the rover suffered an 'amnesia' event. Like most all previous ones, this amnesia event occurred, during the rover's wake-up after APXS work for a DeepSleep. And like the other bouts, it was benign to operations, because the rover has a kind of built-in workaround.

"The APXS data on Margaret is automatically saved on the APXS instrument and it was read out [copied] the following morning, so no science was lost," reported Nelson. But then, just one sol later, 3813 (October 16, 2014), the robot had a second bout of amnesia, again during wake-up for DeepSleep after APXS work on Margaret, and again the data was retrieved from the APXS.

Why Opportunity is still having these amnesia events is bewildering, especially since the reformatting in September was hoped to correct the issue. "We don't have a lot of information," said Nelson. But the rover's software engineers continued in October working on ways to get more information.

Otherwise, Opportunity was just fine and a few bouts of amnesia certainly weren't about to stop this rover. The following sol, 3814 (October 17, 2014), the robot field geologist left Lipscomb to continue her survey of Ulysses' ejecta at a rock dubbed Birmingham. She would hunker down there through Sol 3820 (October 23, 2014) and effectively completed the research at Ulysses.

"The campaign is done and it went well," Squyres said. "We got everything we came for. We’ve done a pretty thorough job of studying the different types of ejecta that are present there. Clearly what we’re seeing are rocks that are impact ejecta, hardly surprising considering the fact that we’re on the rim of a major crater. Clearly, we’re seeing rocks that originated via igneous processes that have a fundamental basaltic character, hardly surprising considering the fact that we’re on Mars. The interesting stuff is in the intricate details of the elemental patterns in the chemistry and the specific processes that led to the variety of rock types that we see there, but it is too early to give you a concise summary. We really need to sit down and look carefully at the systematics of the APXS data in particular."

The rocks in Ulysses ejecta field are "a little bit different, but not a lot and the team is still "puzzling" as to what that means, agreed Arvidson. "Everything pretty much looks the same, just a little bit different than some of the rocks that we've been looking at on the rim. That may just indicate there is diversity in the rocks on the rim and there's not much else to say right now."

Siding Spring still

"It’s something not a lot of people notice, but if you look carefully at this image, this was a long enough exposure that the stars move," said MER PI Steve Squyres. "Instead of perfect little dots for the stars, what you see is a little parallel bunch of lines that are the tracks of all the stars. They’re all parallel to each other, of course, because Mars is rotating and the stars all appear to move in the same direction. The comet appears as a track also, but it’s not parallel. It’s at a slightly offset angle, because the comet was moving across the sky so fast that it moved perceptibly relative to the stars in this exposure. Its track winds up offset and it winds up tilted a little bit at an angle to all the stars. I think that's kind of cool." The image has been processed by removal of detector artifacts and slight twilight glow. The duration of the exposure resulted in a 2.5-pixel smear from rotation of Mars.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / TAMU

By October 17th, Opportunity's Sol 3815, the focus turned to the close approach of comet Siding Spring. Opportunity was to begin shooting at 3 o’clock in the morning, local Mars time, on Sol 3817. "At that time in the morning, the temperatures are extremely cold on Mars," said Squyres, "too cold for the rover to actually physically move anything." So at on noon on Sol 3816, the rover pre-pointed her Pancam to the place in the sky where the team anticipated the comet would be and left it there, pointing skyward.

The actual closest approach of Siding Spring's nucleus to Mars would be at about 139,500 kilometers (87,000 miles), but if Opportunity waited until that moment, the Sun would already be up. So the rover had to start early, two-and-a-half hours before the actual closet approach.

Even then, since the early morning skies were so bright during the dry run, Lemmon and the MER team moved up Opportunity's photo session by 15 minutes. "The Sun [was] more than 20 degrees below the horizon, but there [was] so much dust being kicked up in the Acidalia Storm Track and in various stormy regions on Mars that the high altitude dust [gave] us a long, bright twilight," said Lemmon. That's because light scatters in the dust, "all the way around the rim of the planet," he pointed out. "It's sort of like when a volcano erupts on Earth and you have long twilights. That’s what we got on Mars."

Opportunity's comet shoot, as it turned out, went like clockwork. Around 3 am, the rover woke up and was soon taking pictures as Siding Spring flew in. The robot field geologist spent a little more than half-an-hour taking images at a range of exposure times to take into account the lingering uncertainty of exactly where the comet would be. "We took long exposures, from 10 seconds to 50 seconds long." That's because 50-second exposures are sensitive to the faintest things, and the 10-second exposures would give better detail if the comet’s coma was really bright.

On Earth, just before 2 am Texas time, Monday, October 20th, Lemmon opened the door to his office to wait for the rover's downlink. To capture a comet in a picture is a pretty cool feat from Earth. Some professional photographers and other lucky skygazers have managed to freeze-frame some spectacular images and space artists have certainly enhanced our imaginations with glorious, breathtaking works.

Lemmon, however, had realistic expectations – and the knowledge that Opportunity had tried this before unsuccessfully. It was a tough assignment. He knew for many people the rover's pictures, if she got them, probably wouldn't look all that exciting. But for him, for the MER team, for any explorer, catching this comet would mean something far grander.

"I remember just really wanting to see a comet in the middle some of the images," Lemmon said.

As the first images streamed in, he spotted the comet right away, right in the middle of some frames. The twilight was indeed bright. Even with their last-minute adjustments, the twilight that morning was a few times brighter than expected. "You'd think that if it’s an hour and 20 minutes before the Sun comes up, that it’s going to be dark," said Lemmon. "Yeah, it was pretty dark. But as you see in the images, there’s skylight and you can see the brightness levels increasing dramatically in those images as time passed."

Even so, despite the odds and the difficulty, comet Siding Spring was distinctly visible and Lemmon didn't have to do any special processing. "We got it. We actually nailed it! " enthused Squyres.

"There are not that many firsts that we can manage with Opportunity now… it feels really good to be able to do something like this," said Lemmon. "I'm thrilled."

The MER team plans to issue a second Siding Spring release that "puts together the whole set of images that we got," Lemmon said. "It will be as nice a package as we can put together," added Squyres. "But the real news, the real story is in that first image."

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Malin Space Science Systems

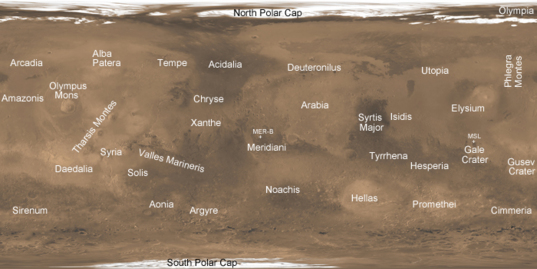

Mars reference map

This reference map, labeled by the folks at Malin Space Science Systems shows many of the Martian place names commonly mentioned in Mars Weather Reports, which can be found here.While the NASA/JPL 'blink' image, presented in this MER Update, began making the news on Earth, up on Mars, Opportunity, still hunkered down at Birmingham finishing up the science survey of Ulysses Crater ejecta rocks, suffered yet another amnesia event on Sol 3817 (October 20, 2014), just one sol after snaring Siding Spring. It was the third such event in October and it happened as the others have, during the wake-up to DeepSleep. "But this one was unusual because it's the earliest we've ever seen an amnesia event," noted Nelson. "Most happen later than 2200 hours. This is the first one we've seen at 18:18 (6:18 pm Mars time) and that's the wake-up for a standard DeepSleep."

Then about 14 hours later, on Sol 3818 (still October 20, 2014), at 8:38 am local Mars time Opportunity suddenly experienced a Flash write failure anomaly and power cycling or, more simply put, a sudden reboot during her solar array wake-up. "There were no apparent adverse effects and the retry was fine, but that was not good to have those," said Nelson.

"We reformatted Flash and since that we have had these amnesia events and one reset," said Callas. "All the events have been benign and have not effected operations," he reiterated. "These events do indicate that something is not right with the Flash memory, but we still do not know the direct connection between the events and the health of Flash – only that they're related." At this point, he added: "If this is as bad as it gets, every once in a while we have amnesia events, this is totally livable."

Nevertheless, the MER engineers are now ready to launch strategic inquiries and soon could launch a solution, if and when necessary. To learn more about what's happening during one of these amnesia events, the MER engineers have come up with a strategy they call Amnesia Instrumentation. Basically, it is comprised of scripts that the rover can run anytime it has an amnesia event, essentially saving a duplicate copy of the event records (EVRs) in its non-volatile memory drive, EEPROM, as discussed in last month's MER Update.

"When Opportunity has an amnesia event, there are EVRs, event records, basically a log of all the events that the CPU is going through, complete with time-tags and that goes into RAM memory, which goes poof when we shut down," explained Nelson. "We're going to take all the EVRs that are stored in RAM and move them to EEPROM [Electrically Erasable Programmable Read-Only Memory] before the rover shuts down for the night."

The amnesia EVR data will be preserved on EEPROM until the rover copies the data from EEPROM back onto Flash and then downlink the data. This will let the engineers see the EVRs from an amnesia event. "We hope it will give us a clue to exactly what's happening," Nelson explained. "We don't know if there will be any information. But this is one way to find out."

Since EEPROM has a limited lifetime, the software engineers have set a flag in the system so that if the rover should have a second amnesia event, it won't save the second copy. "You can only make so many writes to EEPROM and so we don't want to write every amnesia event and we really don't need every amnesia event," Nelson pointed out.

Amnesia Instrumentation has been tested and approved and the scripts have been installed on the rover. "Now we just wait for another amnesia event," said Nelson.

The MER ops engineers are also working on a solution. Since all the rover's Flash write errors and all the things they know about have been isolated to Flash Bank 7, they are considering masking off that bank entirely. The rover's Flash memory, made by SanDisk, has a total of 8 Banks, numbered 0 through 7. With 0 being reserved for uses other than data, that would mean the rover would lose one of the 7 banks it now has for storing science and engineering products.

The loss of that bank translates to a loss of 1/7th or about 14% of the current amount of Flash memory. "We'd like to hang onto that memory as much as we can," Nelson acknowledged. "But we can envision scenarios where it's more important to be trouble free than it is to have more memory … like if the rover has to get to a winter haven to survive." Testing on this possible solution was underway in October.

"We will be able to exercise these options with great flexibility," said Callas. "We can pretty much pull the trigger on these things quickly, get them done in a day, and get moving again. Right now, I'm not alarmed with the amnesia events. If, however, we begin seeing resets more frequently, that could change."

Opportunity performed without any additional Flash issues for the rest of October and it's anyone's guess as to when she might suffer another Flashbug. "We’re doing fine with the Flash and the amnesia events," summed up Squyres. "The biggest concern recently has been the power system and the dust. We’ve been watching the dust storms very, very carefully."

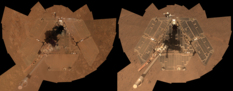

Dusty – again?

Opportunity took a self-portrait in late March 2014 (on the right) that shows that much of the dust on the rover's solar arrays had been removed since a similar portrait from just three month earlier in January 2014 (left). In its sixth Martian winter, the rover wound up with cleaner solar arrays than in any Martian winter since its first on the Red Planet in 2005. Cleaning effects of wind events in Cook Haven, where the rover spent the winter have been credited with clearing the solar-powered rover's arrays and boosting her energy.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

The large regional dust storm impacting Opportunity is one of the more major episodes of regional dust activity that MER has seen in a while. The robot field geologist had finished the Ulysses Crater ejecta campaign and was ready to hit the road, but the dust became an ever more noticeable and increasingly menacing presence at Endeavour that would slow her down.

"This is the first of the Acidalia storm-track seasons where storms originate as small regional storms in the north, cross the equator, and kind of blow up in the south briefly, and trigger heating of the atmosphere in both hemispheres and then go away," said Lemmon. "We’re getting a lot of high altitude dust imported. We’ve had what – outside of a global dust storm – are record dust levels at Opportunity's site, because of how close we are to the regional storms."

"We saw Taus as high as 2.15 and that's getting into an uncomfortable level of dust," said Sqyures. "We had several regional storms blow up individually and then join and merge into a much larger storm. That’s the kind of storm that you really kind of worry about, because you don’t know when they’re going to stay regional and when they’re going to turn into something bigger. In October, the Taus got high enough to get our attention."

Interestingly, the Taus, from Spirit and Opportunity, have surpassed a measurement of 2 only a handful of times, said Lemmon. Both MERs recorded Taus higher than 4 during the planet-circling storm of June, July 2007. "For Opportunity, the Tau was likely around 5 on sols we could not even measure," he said, noting that these are also higher than Viking measured. "But Viking likely faced Tau closer to 9." Then Spirit registered a 2.7 Tau during a regional storm in August 2009.

What does all that mean to a rover?

Opportunity's yellow brick road

The gold line – or Yellow Brick Road for those with imaginations – scrawled on this image shows Opportunity's route from her landing site inside Eagle Crater, upper left, to the rover's approximate location on Endeavour Crater's western rim. The base image for the map is a mosaic taken by the Context Camera, onboard MRO. The rover is en route to Marathon Valley, but will be making stops along the way to "smell the roses," which translates to check out weird rocks and stuff. The veteran MER set the new off Earth distance record for a robot on another planet in July 2014 and is still going strong despite having to hunker down to wait out a raging regional dust storm in October.NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS / NMMNHS

Simply put, "it means the dust is cutting out a fair amount of sunlight, which is what we live on," said Callas. But it's not exactly that simple. "Atmospheric opacity is an exponential term and so each unit of Tau is a factor of 2.7 so if you take 2.7 squared, it's a factor of 7 reduction in a direct attenuation of the sunlight, we still get a diffuse component of sunlight because dust scatters light. So it's not a 1-for-1 loss in power. But it is concerning."

Opportunity's pace slowed as the dust rained and October wound down and the MER ops team began carefully tailoring rover operations to maximize the safety of the rover in the lowered power state. "That’s the reason that once we finished up our investigations on Birmingham, the last rock that we looked at in Ulysses ejecta field, we just didn’t hit the gas and go," said Squyres. "Our departure from Ulysses was delayed significantly by the dust storm, but having the updates from Bruce Cantor and the tracking that the MARCI team is doing for us of the dust from orbit has been incredibly valuable in planning continued operations," he said. "This is spring on Mars, the season for dust storms and we just have to be vigilant. Every year, we've got to be careful."

Finally, on Sol 3821 (October 24, 2014) and the rover did drive away from Birmingham and Ulysses, stopping at rocks dubbed Alabama and Red Mountain, more to reposition herself than make tracks. "We wanted to position the rover and use the rover in a fashion that was going to maximize our ability to ride this storm out," said Squyres.

"We had an unfavorable northerly tilt," elaborated Nelson. "Since dust particles absorb some of the sunlight and also scatter it, so it's actually better to be flat during a dust storm than be tilted. By flattening out our tilt, we pick up more of the scattered light."

That night Opportunity got back on time, resetting local midnight on her clock. "That mostly zeroed out the drift in our Generic Sol Time," said Nelson. The process of resetting the clock – which had drifted 18 to 20 minutes – began in May 2014.

The rover stayed in the area of Alabama/ Red Mountain through Sol 3822 (October 25, 2014) as the fallout from the storms continued darkening the skies, then on Sol 3825 (October 28, 2014) Opportunity put 7.08 meters (23.22 feet) in the rear view mirror. "The energy is still acceptable to drive and do what we need to do," said Nelson. "Rather than being energy limited, we're still probably data volume limited as much as anything – that is, how much we can get back and how much we can store. But it is something we're watching very carefully."

Although the skies were much dustier and the rover's power way down from just one month ago, hovering in 380s as of October 30th and 31st, the weather overall seemed to be improving. The regional storm appeared to be weakening and as Halloweeners took to the streets, the Tau was down to a you-can-breathe-again 1.85. But, as Cantor told the MER Update: "We’ll just have to wait and see what happens."

The rover and her team seemed anxious to drive. "We want to put some odometry behind us," said Callas. "We've laid out a timeline to get to Marathon Valley before the next winter, and to meet that timeline we need to pull up chalks and start driving."

That's exactly what Opportunity did. The rover that loves to rove then roved out October with short drives on Sols 3827-3828 (October 30-31, 2014), for 11.61 meters and 12.03 meters respectively, getting back on the path south to the Summit Lithology, the next intermediate stop, some 750 meters away, and putting her odometer at 40.85 kilometers (40,848.71 meters or 25.38 mile).

Now, as the calendar page turns, Opportunity is slated to drive into November and her marching orders for the next several weeks ones she likes to hear. "Drive and drive and drive some more," as Arvidson put it.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

Wdowiak Panorama

As Opportunity bid adieu to Wdowiak Ridge and its Ulysses Crater in October 2014, we revisit the panorama the rover took in honor of MER Science Team Member Tom Wdowiak, Associate Professor Emeritus at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), and a member of the Mössbauer Instrument team for MER, who passed away on April 27, 2013, at the age of 73. "When we saw this vantage point, we all went: 'Oh yeah, this is the place,'" said MER PI Steve Squyres. "It's a beautiful view of Wdowiak Ridge from the south looking north, and beyond that you can see the Meridiani Plains, Murray Ridge, and into Endeavour," said MER Deputy PI Ray Arvidson. Stuart Atkinson, MER poet, planetary author, and member of UMSF.com, "stitched" the panels of images together and processed them in his Martian Technicolor version, which we present here.Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth