A.J.S. Rayl • Jun 05, 2014

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Hunts Ancient Clays along Murray Ridge

Sols 3650-3680

At the western rim of Endeavour Crater, Opportunity spent the month of May exploring a new clayground along Murray Ridge and the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) mission trundled into the 125th month of what was originally to be a short, 3-month tour.

The veteran rover – clean as a whistle after her winter “blow-off” – pulled into the clay hunting ground during the first days of May and likely will be investigating the rocks, ripples, and veins there through the month of June, working to zero in on clays the MER team knows are here. So far, the ancient clays haven't been visibly, immediately obvious, but Opportunity is gathering all the necessary data and taking a ton of images in what has turned out to be a picturesque trek south along Murray Ridge and back in time to the "stone" ages on Mars billions of years ago.

“Describing the clays and how the clays got here, and putting together a comprehensive story is something we’ll be working on for a number of sols to come," said Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell University.

Since Opportunity’s two mineral detectors are no longer working, the robot field geologist has come to rely on the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), a visible infrared spectrometer onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), to guide her to the mineralogical “goldmines” around Endeavour. It’s been a good match, already led to major discoveries at Cape York, and it's what brought the rover to this ridge.

Designed to look for signs of water past and present, CRISM has detected a number of significant clay mineral sites in Endeavour’s western rim. Beyond this current area along Murray Ridge is a much larger area some 2 kilometers further south, in the Cape Tribulation section of this part of the crater's rim. The team knows a “mother lode” of all kinds of clay minerals await them there.

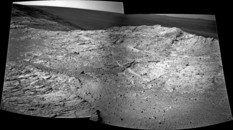

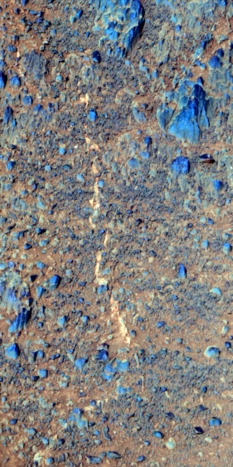

Crest full of montmorillonites

This image shows part of what will be a larger, color panoramic view of a crest along Murray Ridge where Opportunity hunted for montmorillonites (clay minerals) in May 2014. The rover took the pictures that went into this image with her panoramic camera (Pancam) in mid-May. Stuart Atkinson, author, MER poet, planetary science educator, and member of UMSF.com, processed them, producing this glorious black & white postcard from Mars. For more of Atkinson's work, check out his blog, "The Road to Endeavour."NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

In a very scientifically studious way, Opportunity is purposefully passing through the 240-meter long, 30-to-40 meter wide clayground that lit up in the CRISM data with the signature of montmorillonite, an aluminum-rich clay mineral of the smectite group also containing sodium and magnesium. Months ago, it was chosen as a prime rover destination on the route south to Cape Tribulation. "We're now exploring the place montmorillonite clays have been detected by CRISM and seeing what Opportunity can add to the story," said Ray Arvidson, deputy principal investigator of Washington University St. Louis, who is also a co-investigator on CRISM.

So far, the story tells of an ancient Noachian Period environment where there was probably a substantial amount of near neutral water – water a human could drink – flowing through the area, transforming rocks, and enabling the formation of clays.

For MER, the mission science objective was to look for past potentially habitable environments. As far as we know, where there is water, there is life; therefore, water has long been the scientific Holy Grail in Mars research. Spirit and Opportunity were dispatched with all the right equipment to detect mineralogical evidence of past water in NASA's "Follow the Water" strategy for exploring the Red Planet. And both rovers found water and past potentially habitable environments long, long ago. It's just that most of the evidence indicated water that was highly acidic.

Now at Endeavour Crater, the robot field geologist is roving back to a time when Mars probably looked a lot like Earth. The evidence is in the phyllosilicates or clay minerals that usually form from fine-grained soils with one or more clay minerals and traces of metal oxides and organic matter, in water of neutral to high pH or alkaline, as opposed to highly acidic water.

Geologic clay deposits on Earth are mostly composed of phyllosilicate minerals containing variable amounts of water within the mineral structure and Opportunity is ground-truthing that holds true of the found phyllosilicates on Mars. Adding to the intrigue in the evolving story of early Mars, clays play a starring role in theories on the emergence of life as we know it. Various hypotheses of abiogenesis, the natural process through which life emerges from non-living matter like simple organic compounds, involve clays.

Rover nose to the grindstone, Opportunity put in a work-a-day month in May, maneuvering through impact breccias, rocks, boulders, and slabs that the MER scientists believe were hurled up by whatever impacted Mars and formed Endeavour Crater some 4 billion years ago, when this was a different place.

The rover’s work during the past several weeks successfully confirmed some of the findings made in the Cape York section of the crater’s western rim. But Matijevic Formation rock, the oldest rock layer that Opportunity discovered when studying Matijevic Hill in 2012, remained elusive here, just as it had at Cook Haven, buried beneath meters of the impact breccia or Shoemaker Formation layer.

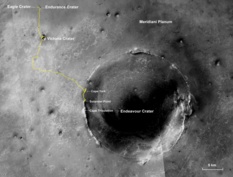

Opportunity's claygrounds

This map shows part of the eroded western rim of Endeavour Crater and Opportunity's most recent and future clay mineral hunting grounds. It features a base image taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) over which MER Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson and his graduate student, Valerie Fox, a MER science team member, both of Washington University St. Louis, mapped and color coded the area where the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), has detected clay mineral signatures. Montmorillonite signatures (Al-smectite) are highlighted in green at Moreton Island, which Opportunity investigated in November 2013, and in blue along Murray Ridge, where the rover was working in May 2014. CRISM also detected nontronite (Fe-smectite) and saponite (Mg-smectite) clay signatures further south, in the rim section called Cape Tribulation, specifically from a place MER team members have been calling Smectite Valley, shown in red. "The valley is likely to be a very rich hunting ground for us," said Arvidson, who is also a co-investigator on CRISM.NASA / JPL-Caltech / ASU / R. Arvidson, V. Fox, WUSTL

The MER science team had anticipated this based on orbital data, so the rover pressed on conducting routine investigations on chosen targets. From the mission that established an Earth presence on Mars more than 10 years ago, where it seems almost every month is highlighted by a major discovery or event or coincidence or new record, that may seem – well, a little boring. But for Mars research, it is necessary and anything but boring.

“We are in a work-a-day mode here," agreed Matt Golombek, MER project scientist of JPL. "But if you think about it, that's really the way we've been for more than 10 years and in some ways, we're just now getting to the most exciting part of the entire mission.”

Most exciting, and scientifically, arguably, the most relevant. Opportunity is poised to resolve the big question in Mars science for once and for all: was there an early period in the planet’s history when it was warmer and wetter and more like Earth, “a time perhaps during the earliest part of the Noachian Period, pre-3.8 billion years ago, when neutral pH water was abundant and life could have emerged?” as Golombek asked. “At Endeavour Crater, we are looking at ancient Noachian, phyllosilicate-bearing rocks that can address that big question.”

What Opportunity finds in Endeavour’s rim will also likely touch on the question of how that water-rich, life-friendly environment then segued into the more acid rich environment during which the Burns Formation sulfates were deposited, the rocks and deposits over which the rover roved for much of its mission so far – and, perhaps, to some extent explain what happened to the large areas of liquid water that have since disappeared, transforming the planet into a harsh and desolate world. “Right now, we're on the rim of this ancient impact basin and looking at the most critical part of Mars' history,” said Golombek, “and MER is the only surface mission that's doing this.”

When May dawned at Endeavour Crater, Opportunity was en route to the new clayground. With 39.22 kilometers (24.37 miles) on the odometer and producing 624 watt-hours of power (about 2/3 of its capability), the robot field geologist drove out of April and into May. She logged 70 meters (230 feet) on Sol 3649 (April 30, 2014) and more than 95 meters (312 feet) on Sol 3650 (May 1, 2014), putting Cook Haven, her winter home, far behind.

Opportunity emerged from her sixth Martian winter cleaner and able to produce more solar power during a winter since the first winter MER spent on Mars in 2005. That’s because Cook Haven proved to be a "scour zone" as Arvidson first described it in the March MER Update. "If I went up there in a spacesuit with a dust rag, I don't think I could get it this clean," said Squyres.

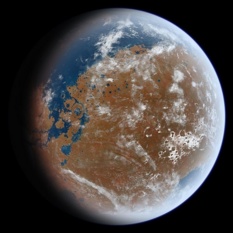

Noachian Mars imagined

Opportunity is currently roving over Noachian terrain at Endeavour Crater. This is an artist's impression of what the Noachian Mars might have looked like. Late Hesperian features (outflow channels) are shown, so this is not an exact impression of Noachian Mars, but the overall appearance of the planet from space may have been similar to the impression and to Earth. The artist, Ittiz, created this image using knowledge of Martian geologic history and data from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter, an instrument on the Mars Global Surveyor, which was de-commissioned in January 2007.Ittiz

Opportunity positively glistened in May. As Mars would have it, the rover's energy would only increase as the month progressed and she climbed the crest of Murray Ridge. "We seemed to have found the Fountain of Youth on Mars – it’s like we've become a teenager," beamed Bill Nelson, chief of MER engineering at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), home to all NASA's Mars rovers.

Perhaps the most jaw-dropping bit of data that had the MER ops team members marveling in May was the steadily improving dust factor on the solar-powered rover’s arrays. Perfectly clean solar arrays would boast a dust factor of 1.0, so the larger the dust factor, the cleaner the arrays, and the more sunlight is transformed into power. The rover's power production and the Tau and the dust factor all fluctuate throughout a given month, but in May Opportunity's solar array dust factor went from 0.832 to 0.962, which is close to as good as it can get and a record for a rover more than 10 years into its mission.

“It's great. It's Sol 1," said John Callas, MER project manager, of JPL. “It's the good part of Ground Hog Day.”

Since Opportunity's first drive in May conveniently put her within reach of a ripple crest the robot conducted a touch-and-go on that target, named Mulgrave Hills, on Sol 3652 (May 3, 2014). Following routine, she took pictures with her microscopic imager (MI) for a close-up mosaic, and then placed her alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) on the ripple for an overnight integration to determine its chemical make-up. The next sol, the rover took off, driving more than 60 meters (199 feet) to the southwest and into the destination region of montmorillonite clay minerals.

"There are a gazillion different clays," noted Golombek. What makes the clays different are their molecular structures, which vary slightly, giving each group its 'identity.'

"CRISM has detected montmorillonite in this area through an infrared vibration of aluminum in the crystal structure interacting with an attached hydroxyl (an oxygen atom connected to a hydrogen atom)," said Arvidson. "The exact wavelength detected is indicative of montmorillonite, as opposed to many other types of clay minerals," he said.

On Sol 3655 (May 6, 2014), Opportunity bumped 5.5 meters (about 18 feet) to reach an exposed rock outcrop called Ash Meadows. As Arvidson anticipated during the last MER Update, it looked like the montmorillonite site is a rocky field of impact breccia.

That same sol, Opportunity began the first step of a process to correct for spacecraft clock drift. Just like your basic wristwatch, the rover's clock has drifted "maybe a second per sol" during the rover's decade on Mars, according to Nelson and is now 18 to 20 minutes off, so it must be adjusted.

Simple as it may seem to just reset the clock and correct the time all at once, the way you would on your watch, the team intends to correct the clock very, very slowly, eventually removing all of the clock drift over the course of a year. "If we were to do it all at once, just reset the clock, then all of our UHF and X-band windows would suddenly be mis-timed," explained Nelson. "We don't get a lot of DSN track and the orbiters are only overhead for about 16 minutes. If you jump the windows by 20 minutes, suddenly either those communication assets haven't risen above the horizon or they have come and gone. Either way you'd suddenly be without downlink communication."

Even one minute per sol is too big a jump. "We've got some rather tight timing when we do the uplink sweep to get our radio aligned with our uplink frequency," Nelson said. "And if you mess around with it by more than a minute, then you mess up that timing and if you mess up the timing then you run the risk of not being able to communicate. So, we're reversing the process by adding 1 to 2 seconds per sol," he said. On Sol 3656, the rover made a 1-second correction.

After taking it easy on Sol 3656 (May 7, 2014) conducting routine tasks and using the APXS to measure atmospheric argon, Opportunity got up close and scientific with Ash Meadows. As usual, the robot took a series of pictures with its MI for a mosaic of the surface, and then placed her chemical-sniffing APXS on the rock for a multi-sol integration leading into the weekend of May 10-11. "It's part of the Shoemaker breccia," confirmed Arvidson.

On Sol 3659 (May 10, 2014), Opportunity drove just under 26 meters (about 85 feet) to the east, approaching a region of extended outcrop that looked promising for clay hunting. She also tested the new 2-second spacecraft clock correction sequence. During the next two sols, the rover took atmospheric argon measurements with her APXS and performed two more 1-second clock corrections.

Opportunity then bumped 2 meters (about 6.6 feet) forward on Sol 3662 (May 13, 2014), to approach an intriguing vertical vein, dubbed Bristol Well. The robot field geologist spent the next four sols there examining the vein with her MI and APXS.

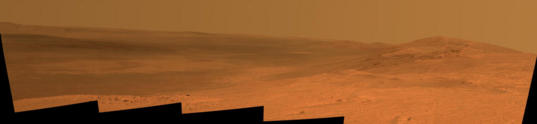

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Arizona State University

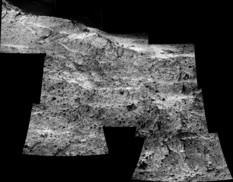

Peeking into Endeavour

Opportunity took this view into Endeavour from the southern end of Murray Ridge, located in an eroded rim section on the western side of the crater. The image is comprised of several exposures the rover took with its Pancam on its Sol 3637 (April 18, 2014). The view extends from the east-southeast on the left, to southward on the right. It encompasses the far rim of Endeavour Crater on the left and the crater's western rim on the right. Endeavour is 22 kilometers (14 miles) in diameter. The small impact crater visible in the distance on the slopes of the far rim is about 225 meters (about 740 feet) in diameter and is 21 kilometers (13 miles) away. The high peak in the distance on the right is informally named Cape Tribulation and is about 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) to the south of Opportunity's position when this view was taken. On Sol 3662 (May 13, 2014), Opportunity approached the dark outcrops about halfway down on the right side of the image."It turns out to be calcium sulfate," said Squyres. "We've seen calcium sulfate veins here before, so it wasn't a new finding or any kind of surprise, but it was a good confirmation and we nailed it."

Beyond its vertical positioning, the most interesting thing about Bristol Well is that it is "really high up topographically," said Arvidson. "We're just now trying to make sense out of the data, but this vein is topographically the highest sulfate vein we've seen. That means a lot of water, maybe even that these calcium sulfate bearing waters went all the way to the top of the rim – or maybe it was buried – we don't know yet."

The adventure so far

The gold line on this image shows Opportunity's route from her landing site, Eagle Crater, upper left, to the areas has been recently investigating on Murray Ridge in the Solander Point section of the western rim of Endeavour Crater. The base image for the map is a mosaic of images taken by the Context Camera on MRO, built and operated by Malin Space Science Systems. This traverse map was made by Larry Crumpler, a MER science team member, of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science, Albuquerque.NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS / NMMNHS

Once Opportunity finished work on Bristol Well, she did another 2-second spacecraft clock correction sequence on Sol 3666 (May 17, 2014). The rover then settled in for a couple of sols to focus on taking pictures for a panorama of the crest where she was exploring and the breathtaking views all around her.

Offering a glorious view into Endeavour, the first pictures, the pieces, if you will, of the panoramic puzzle – are hauntingly reminiscent of any number of national parks in the western United States. As Stuart Atkinson pointed out in his "The Road to Endeavour" blog, this site feels like the kind of place that could be a tourist destination on Mars someday, a place visitors might go to sit, take in the serenity of the scene, and perhaps ponder the marvels of Mars and humanity's first arrival there.

In addition to her imaging assignment, Opportunity also took atmospheric argon measurements with her APXS for the ongoing, mission-long study, and did two more 1-second clock corrections.

Although the motor currents on the rover's right-front wheel had been consistently elevated during driving in April, as Opportunity kept on truckin' in May, driving mostly backwards to alleviate the issue, the currents returned to lower levels. "They're not normal, not nominal because they are elevated," said Callas. "But it's not at an aggravated elevated level. I use the term it's 'well behaved.'"

Since this "hoit" wheel issue first appeared, the rover engineers have suspected it was a lubricant issue, that the lubricant wasn't well distributed in the motor-actuator system. But now they're thinking differently. "We're now wondering if there is actually debris on the brushes that sometimes gets between the rotor and brush creating a higher resistance path and hence elevated current to overcome that extra resistance," said Nelson. It's a theory, he added, that is "gaining support."

Bristol Well

Opportunity took this picture of a vertical calcium sulfate vein in May 2014 with her Pancam. Yes, it is shown in the right orientation here. The light-toned vein is clearly visible in the middle of the picture. In addition to it being so high up in the rim, "the interest is in the bright vein running vertically through the image," said Ray Arvidson, deputy principal investigator of Washington University St. Louis. The image is processed here in false color, a technique that enables scientists to better distinguish the different elements in an image.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell /ASU

As May marched on, Opportunity produced increasing amounts of power, reporting 761 watt-hours as the second week of the month came to a close. Although the skies were hazy, with Tau recorded at 0.621, the rover's dust factor was nearly stupefying at 0.964.

"We've spent a lot of time thinking what's the magic formula – what is the approach you take to getting a rover clean?" mused Squyres. "The answer is: you climb a hill. Pure and simple. We saw this with Spirit too, where the big cleaning events came at the summit of Husband Hill, the ridge crest. This is the first mountaineering we've done with Opportunity and we climb to the top of the Murray Ridge and – ka-boom! So the magic formula is -- climb a hill, get up on a ridge crest that exposes you to the winds and you get cleaned off. We've seen it on both sides of the planet now."

On Sol 3669 (May 21, 2014), the robot field geologist drove a short 2.89 meters (about 9.5 feet), south-southeast from Bristol Well to a flat, slab of outcrop dubbed Sarcobatus Flat. There, Opportunity conducted a close-up inspection, brushing the rock with her Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT), taking pictures with her MI, and of course analyzing its chemical content with the APXS during overnight integrations. Then, on Sols 3674 and 3675, the rover made the same inspections on a clast, or smaller rock called Sarcobatus Clast, located on the slab.

All in all, May 2014 was a producitve, if work-a-day month. The only "bummer" came when Opportunity suffered an amnesia event on Sol 3675 (May 27, 2014). "It happened during the overnight wake-up, which is where all of them have happened for Opportunity," said Callas. "We are familiar with this issue and there is no health or safety issue for the vehicle," he said.

The rover engineers are confident that the amnesia is caused by a corrupted sector in the rover's Flash memory and there is a fix – reformatting the memory. But the amnesia events must increase before it makes sense to reformat, as previously reported in past MER Updates. In the meantime, Opportunity has "a special amnesia detector," reminded Callas. "Essentially the rover writes a note to itself and that's how we know when these things happen," he said.

Since the APXS has its own flash memory and the instrument is programmed to automatically record its measurements, when amnesia strikes, after getting the rover back under master sequence control, the team has the rover read out the data from the APXS' memory the next morning. "So, although we missed some engineering data records known as EVR's [for Event Reporting Service], no science data was lost," Callas said.

Field of breccia

This image is another compelling black and white postcard from Mars processed by Stuart Atkinson, author, MER poet, planetary science educator, and member of UMSF.com. It shows another part of the larger, color panoramic view to come, taken from the crest along Murray Ridge where Opportunity hunted for montmorillonites (clay minerals) in May 2014. For more of Atkinson's work, check out his blog, "The Road to Endeavour."NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

"Typically, we experience these amnesia events the late evening – we'll put down the APXS, let it integrate while the rover naps, then wake-up, usually around 11:18 pm, do a little bit of housekeeping, turn off APXS, and then shut down," explained Nelson. "That puts us into a DeepSleep. It's that wake-up and shut down where the amnesia occurs. It was like rinse and repeat this time, with the same symptoms as all the other amnesia events this rover has had. But it did not affect sequencing, so Opportunity's activities were unaffected."

Once Opportunity was back in the saddle, the MER team, realizing that the APXS positioning on Sarcobatus Clast on Sol 3674 "was not centered well," as Nelson put it, had the rover redo the chemical analysis on Sol 3676 (May 28, 2014). With that task finished, she headed southwest on Sol 3677 (May 29, 2014), putting another 20 meters (about 65.6 feet) behind her as she explored the montmorillonite site along Murray Ridge.

Although the skies overhead remain hazy with dust raining down and the winds of the Martian spring are on the horizon, Opportunity is one sparkling clean machine and she's roving well. As May began to fade, the solar-powered robot was producing 764 watt-hours of energy with a dust factor of 0.942. "With such a high dust factor, we are in wonderful shape as far as energy," said Nelson. "Opportunity is doing remarkably well in its senior years," summed up Callas. "We all wish we could be this healthy at that stage of our life.

In June, the veteran Mars explorer will continue her journey south paralleling the crest along Murray Ridge, "looking for other things to investigate," Squyres said.

"We're just beginning to study this montmorillonite ridge and I think there's no question we're seeing plenty of calcium sulfate veins here, so we've got that," said Squyres. "When we look at the rocks with APXS, preliminary indications are they are enriched in aluminum and silicon, which is sort of what you'd expect if there was a component of montmorillonite here, but we're just getting started.”

At the moment, the MER science team has yet to determine where exactly the montmorillonite signature CRISM detected is coming from. "We're on the ridge and you can see from the images sent back that we're in the Shoemaker Formation, which is the impact breccia," said Golombek. "Right now we don't know what the carrier of this signal is, but we have a couple hundred meters of what looks like really good, exposed outcrop to figure it out."

"We want to go along the ridge to see if we can find the equivalent of the boxworks that we saw on Matijevic Hill at Esperance, for example, where water would have percolated through at a high rate and really altered the rocks," elaborated Arvidson. "That's really the direct evidence that Opportunity can get to show the presence of clay minerals. It's a work in progress."

"We could actually make much faster progress down this ridge if we wanted, but this is such an important science target that we want to really understand it, so we're working our way very slowly and methodically down the length of it, documenting it as we go with Navcams and Pancams and occasional IDD work," Squyres said. "By the time we get to the southern end of it, we hope to have really good understanding of this."

It would seem safe to predict the really big clay mineral payoff will come when Opportunity roves into what some MER team members are calling the Smectite Valley, which is still 2 kilometers to the south in Cape Tribulation. "But what's so exciting about a rover on the surface," reminded Golombek, "is that you never know what's around the corner."

In other related news

Colin Pillinger, the British planetary scientist and professor at the Open University who championed the U.K.'s Mars lander Beagle 2 in 2003 and was awarded the Commander of the British Empire medal (CBE), passed away on May 7, 2014 in Cambridge England. In 2005, Pillinger had been diagnosed with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (MS), which meant he was probably confronting a steady physiologic decline. His death came suddenly however, following a brain hemorrhage the day before. He was 70 years old.

Colin Pillinger and Beagle 2

Colin Pillinger, a professor at the Open University in England and the scientist who championed the Beagle 2 lander, died on May 7, 2014, after suffering a brain hemorrhage. He is pictured here with a model of the Beagle 2, which was lost in December 2003. "His loss is affecting us all," said Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator.Beagle 2 / Open University / ESA

Perhaps the most amazing thing about the Beagle 2 is that it came into being at all. There were times that it seemed to eke ahead on Pillinger's hopes and dreams alone. Named after the H.M.S. Beagle, the ship on which Charles Darwin sailed while doing the research that led to his theories of evolution, Beagle 2 was produced on a budget of $120 million, $40 million of which came from the British government, the rest from private interests. The small, clam-shaped lander hitched a ride on Mars Express, which dispatched it onto a trajectory to land on December 25, 2003. No one knows exactly what happened and there are a number of theories, but the Beagle 2 never phoned home. Despite his naysayers, Pillinger succeeded in rallying people in the UK to support space exploration.

During his career, Pillinger distinguished himself as an expert in chemical properties of extraterrestrial, geologic objects. He worked with NASA on Moon rocks collected during the Apollo missions, as well as on Martian meteorites. He wanted to take his expertise to Mars and uncover life there and he believed he could...he would. And after spending a little time with him, you were jolly well agreeing – why not?X!

"I've got huge respect for Colin Pillinger," reflected Squyres. "I always admired the passion and energy he brought to Beagle 2 and I have a pretty good feel for the challenges Colin and his team faced. We were both trying to do similar things, but Beagle 2 was an attempt to do something very ambitious on a shoestring budget. And, as you recall, Beagle 2 was trying to land on Mars during the exact same opportunity as we were and they attempted their landing only a week before the Spirit landing."

While the media played up a rivalry between Squyres and Pillinger, backstage it was quite the opposite. The "conventional wisdom" then was Beagle 2, Spirit, and Opportunity would all likely fail. The odds were clearly stacked against them, two in three missions to Mars didn't make it, and these three were all risky, landed missions. Few people outside the teams really believed any of them had a chance.

The last picture of Beagle 2

The European Space Agency's Mars Express dispatched Beagle 2 in December 2003. It was slated to land and phone home on December 25, 2003. But the Beagle 2 was silent. While there are several theories as to what happened to the lander, no one knows for sure what happened.Beagle 2 / ESA

Just as that pressure bonded MER team members, it also bonded PIs across The Pond. "Behind the scenes, Colin and I became good friends," Squyres said. "I remember very well the night we landed with Spirit – being in my office at JPL a couple of hours after the landing, and getting a very gracious, congratulatory phone call from Colin. This was just a week after he had attempted with his spacecraft to land and they were still trying to recover Beagle 2 at that point. That was classy. I was really sad when Beagle 2 didn't work. Now, Colin passing away – it's a terrible loss."

Word spread a couple of weeks ago that a particular spot along the crest of Murray Ridge has been named for Pillinger. That is not official. Those who follow MER know that Squyres has a specific, respectful way of handling the naming of such honorary sites that includes an official press release along with a panorama of the site, and some biographical background and memories of the site's namesake.

"It is important to me personally and to our team that we name something in Colin's memory," Squyres said. "The ridge we're driving along, there are just spectacular views, gorgeous views with a marvelous vista into Endeavour Crater, and rocks all around. We took a beautiful panorama, but it has not completely come down yet – and I want to do this right. It's in Colin's memory."

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth