A.J.S. Rayl • Mar 06, 2013

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Begins Wrapping Science on Matijevic Hill

Sols 3209 - 3235

Mars Exploration Rover

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Maas Digital

As February turned to March, Opportunity was conducting some of its final science investigations on Matijevic Hill, the MER team was making preparations for the robot field geologist's trek south for the next winter, and the Mars Exploration Rovers mission was checking off another month of exploration.

The current hope is for Opportunity to wrap-up work on Matijevic Hill in the next couple of weeks, depart Cape York and be roving southward to Solander Point no later than May 9th, where - if everything goes as hoped - the rover will spend the next Martian winter. But the exact day and time have yet to be determined and there is no official route yet.

"Everybody's eager to get moving and there's still a lot of science to be done at Cape York. We have to balance those two against each other," Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell University told the MER Update. "We don't have a fixed departure date, because the mission right now is still discovery driven and I can't promise nothing else will pop up. But, unless we find a dinosaur bone sticking out of a rock" he added, "we're going to have to get out of here pretty soon."

The ninth of May is the "last possible date" that Opportunity can leave Cape York and get to Solander Point "safely and with plenty of margin," according to John Callas, MER project manager of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where all the American Mars rovers were "born." Waiting that long however means the rover won't be stopping anywhere long enough en route to study much of anything.

"If we want to do science along the way, we want to depart earlier, so there's flexibility - we're trading science now for science later," said Squyres. "We're going to make our decisions based on balancing the science we have in front of us against the science we have off in the distance."

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / Arizona State University

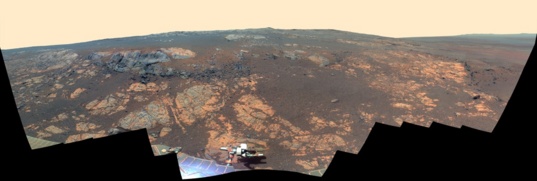

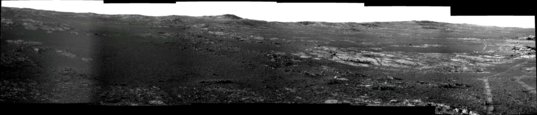

Matijevic Hill Panorama

Opportunity took the hundreds of component images for this panorama with her stereo panoramic camera (Pancam) from Nov. 19, 2012 through Dec. 3, 2012. Named in honor of JPL's Jake Matijevic, one of the creators of Spirit and Opportunity and a Mars rover pioneer, the hill is an area within the Cape York segment of Endeavour's rim. Jake passed away on Aug. 20, 2012, shortly after Curiosity landed. "It's still very hard," said Ashley Stroupe, one of the rover planners, during an interview this month. "We're here exploring Matijevic Hill, so his name is in our minds every day. A day doesn't go by when we have a question and know the person who would know that answer off the top of his head was Jake. We miss him tremendously. It's a terrible loss for everybody and Mars exploration in general. He was one of the incredible people behind the whole program."The timing of Opportunity's departure is also being influenced in part by solar conjunction, which occurs in April. This event happens every 26 months or so, when Mars and Earth are aligned on opposite sides of the Sun. During this biannual, two to three-week period, the Sun can disrupt radio transmissions between the two planets, so the team stops commanding the rover, and directs Opportunity to go on autopilot and work a 'science-light' campaign, standing down from all but a few minimal communications.

There's no hiding the driving desire among team members. "The bulk of the team says: 'We've done it. It's time to get on to Solander Point,'" said Ray Arvidson, MER deputy principal investigator, of Washington University St. Louis. "We have to be there by August, and the longer we stay here, the fewer things we'll be able to do along the way."

The general plan is for the rover to follow the western rim of Endeavour Crater south for approximately 2 to 2.5 kilometers depending on the trail blazed to Solander Point. With steeper, north-facing slopes than Matijevic Hill - slopes that Arvidson described last month as "beautiful" - Solander Point offers a bounty of new rocks and layers that should keep the scientists busy through the six months of the Martian winter.

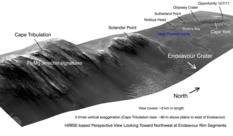

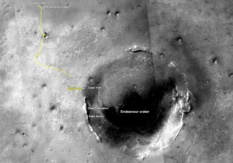

Endeavour Crater's west rim

Although Opportunity is not quite finished with her work at Matijevic Hill in the Cape York area of the Endeavour Crater rim, a lot of the talk this month among team members was focused on getting the rover back on the road, heading south for Solander Point. "Everybody's eager to get moving and there's still a lot of science to be done at Cape York. We have to balance those two against each other," Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, told the MER Update. Solander Point can be seen in this image to the south of the rover's current location at Cape York. This graphic was put together with an image taken by the HiRISE camera onboard MRO.NASA / JPL-Caltech / University of Arizona

"We want to get to those slopes for winter," said Bill Nelson, chief of rover engineering at JPL. From the engineering perspective, those northern slopes offer Opportunity numerous places to park at a 15-degree tilt, so she can angle her solar arrays to the winter Sun in the north and soak up as much sunlight as possible. With so many slopes, it's possible the solar-powered rover won't have to stay parked but could produce enough energy to rove around Solander, from slope to slope, through the harsh season.

A number of MER team members are charting routes for consideration, each knowing that once the rover embarks on it trip anything could happen. The route will likely change here and there, because Opportunity, as Squyres pointed out, is on a discovery-driven mission.

At a team meeting this past week, JPL's Tim Parker, a sedimentologist and originator of the Mars Ocean hypothesis, presented a route that he put together with geologist Matt Golombek, senior research scientist, also of JPL. It would take Opportunity on a 2.5-kilometer trek that would begin with a zig-zag drive out of Cape York, through Botany Bay and to Nobby's Head, by a few craters, and on to its winter destination. Another route, referred to as the "rapid transit," would take the rover straight to Solander, said Arvidson, by the shortest, most direct route possible.

Whichever route is ultimately chosen, as Arvidson summed it up: "Solander Point is beckoning us."

Even as the MER team contemplates the journey south, the focus for now remains on having Opportunity finish its science investigations on Matijevic Hill and consider if there's anything more to see or do before the team decides it's time to go. To that end, the rover had a workaday schedule in February, making "short hops from one science target to another," said Ashley Stroupe, rover planner, and packing in as many scientific observations as possible at each stop.

"Things have been moving ahead at a very regular pace," said Callas. "The team is addressing the objectives that [it] wants to at this site on Matijevic Hill. We're knocking off the things we need to do before we begin to head south."

During the first week of February, Opportunity finished an examination of the newberries at Flack Lake. The robot field geologist first discovered the small mystery spherules as it roved up to Kirkwood, the fin-bearing outcrop that lured the mission to the base of Matijevic Hill late last August. Since then, the rover has photographed them all around the hill, although their numbers diminish toward the crest.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / Ant103

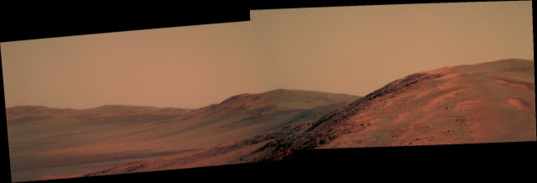

The view south from Cape York

This image, processed into a painting by Ant103 of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, shows Opportunity's view to the south from Cape York. The rover took the raw image that went into this picture with her Panoramic Camera (Pancam) back in November 2011."Crunchy on the outside and soft on the inside," as Squyres initially defined them, the mystery spherules are nothing like the hematite-rich blueberries the rover found shortly after landing and throughout her travels around Meridiaini Planum. At this point, the newberries appear to be more like the clay-bearing rocks where the bulk of them are found, according to Arvidson. Given that the rover's two mineral detecting instruments are no longer working, it's hard to determine their exact composition, but maybe not impossible.

Opportunity pressed on, driving north a ways to look for the contact or boundary between the Shoemaker Formation impact breccias and the Kirkwood/Whitewater Lake/Copper Cliff outcrops. "The month was devoted mostly to trying to understand how the clay bearing stuff we see at Whitewater Lake, with all the newberries in it, is related to the Shoemaker-like stuff further up the hill," said Squyres.

After stopping at a place called Fecunis Lake, the rover then drove west and further up hill to another possible contact, an outcrop called Maley, but Opportunity wasn't able to find any defined boundary. "What we've found is that there is not a sharp contact anywhere between the two. It's sort of a gradational contact," said Squyres. "At the bottom of the hill, you have Whitewater Lake, at the top you have Shoemaker Formation breccias, and as you ascend the hill we see a sort of gradual transition from one to the other." That means that there was some "mixing of materials" as the crater ejecta were emplaced. "You can head up the hill into what are clearly impact breccias and still see a few newberries mixed in. The farther up you go, the fewer the berries there are, but clearly these two materials got kind of jumbled up together when the impact took place. That's been the main finding from that," he said.

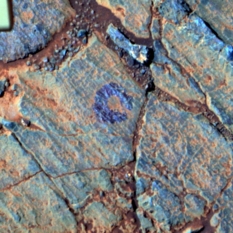

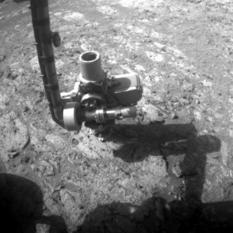

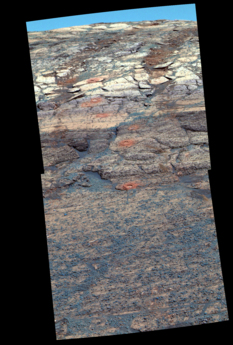

Maley up-close

This picture shows the spot Opportunity brushed with her Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT) on the outcrop called Maley. The robot field geologist took this image with her Pancam around February 20, 2013, the rover's Sol 3227. It was processed and presented in color here by the Pancam team so scientists can better discern materials and components of the outcrop. The false color images can also appear artistic.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

From Maley, Opportunity drove southeast to Big Nickel, a rock noted during the rover's survey of Matijevic Hill last October-November for its boxwork structures. The rover was to grind one of the structures with its wheel, but because of its positioning on a 12-degree slope and the loose terrain, the rover just kept slipping. So on Monday, February 25th, the team commanded its charge to reposition itself, take pictures of the target area, now called Boxwork, with the microscopic imager (MI), then place its chemical detecting spectrometer on it, and call the study done.

The plan had then been for Opportunity to drive into March and conduct one more experiment with the newberries, perhaps back at Kirkwood, where the rover first began the study of Matijevic Hill late last August. But on Sol 3235 (February 28, 2013), it experienced another Flash memory fault and remained at the Boxwork target Lihir, said Nelson. "The rover is fine," added Stroupe. The only loss was a "couple of days."

Other than the few "aches and pains" Opportunity has suffered over the years - a broken heater that forces the rover to shut down every night, a locked right front wheel, two unusable spectrometers, and a broken shoulder joint - "the rover is in excellent health and has experienced no new operational issues," Nelson said. "Opportunity is a real trooper and she's doing a great job," agreed Stroupe, one of three women rover planners (RPs) now at the 'wheel.'

Speaking of women drivers, in acknowledgement of Women's History Month in March, here's a MER factoid worth noting: Since Curiosity touched down on Mars last August, Opportunity has been driven almost exclusively by three women: Julie Townsend, who began on MER during the development phase in 2001, Tara Estlin, who was the leader of development for the rover's AEGIS software system that took NASA's 2011 Software of the Year award, and Stroupe, who has been a staff engineer at JPL since December 2003. For Baby Boomers and even the Lost Generation, reading this, that's remarkable. It wasn't planned that way. It just happened and, as it happens, it's about to change. "John Wright [one of the first MER drivers] is coming back from Curiosity and in time Paolo Belutta, who has also been on Curiosity, is coming back," noted Stroupe.

Still, since the days of the Space Race, when Margaret Hamilton was the lone woman in a sea of male engineers, directing the blackbox development and designing key elements of the flight software for the Apollo command modules and Lunar Exploration Modules (LEMs) for NASA from the Charles Stark Draper Lab at MIT, women have made so many critical and often unsung contributions. Having all that "girl power" commanding Opportunity is a sure sign that women have come a long, long way in the once male-dominated world of space exploration. It's also testament to - women drivers.

NASA / JPL-Caltech

Women of MER

In recognition of Women's History Month in March, we note in the story a little history made on MER over the last six months by women drivers. And it's not the first time women have made history on this remarkable mission. on February 22, 2008, the entire tactical operations team for the MER, both onsite at JPL and offsite at remote institutions, was female. We present the JPL ops team here. Standing left to right: Jennifer Herman (Power Subsystem); Cindy Alarcon-Rivera (Security); Brenda Franklin (Engineering Camera Payload Uplink Lead); Caroline Chouinard (Tactical Activity Planner / Sequence Integration Engineer); Sharon Laubach (Engineering Team Lead); Pauline Hwang (Tactical Uplink Lead) Colette Lohr (Tactical Uplink Lead); Tara Estlin (Rover Planner); Dina ElDeeb (Tactical Downlink Lead / Systems Engineering). Sitting left to right: Diana Blaney (Deputy Project Scientist); Cindy Oda (Mission Manager); Ashley Stroupe (Rover Planner) who has her hand on the rover (and lived to smile about it); Julie Townsend (Rover Planner) Alicia Fallacaro Vaughan (Tactical Activity Planner / Sequence Integration Engineer) Manju Kapoor (Telecom Subsystem). Since Curiosity landed in August 2012, Opportunity has been driven on Mars by a trio of women drivers that includes Julie Townsend, Ashley Stroupe, and Tara Estlin. Fair to say, women are rockin' rocket science.And speaking of rover drivers, "we need some," sighed Nelson. "The MER team and the Mars Science Laboratory team working with Curiosity are a little short-staffed now with the recent departure of RPs Scott Maxwell and Chris Leger, for Google. If you're considering applying, you must be robot qualified. In other words, you've got to have serious experience with robots. And, know the training can take as long as a year and a half. This is a little more intense than the Lettuce Amuse You Traffic School in Los Angeles. But any way you look at it, this need for drivers on Mars is another testament to JPL engineering and the remarkable longevity of Opportunity.

Overall, February was a month of science by the book. No big discoveries but more pieces for the big picture puzzle. Importantly, Opportunity suffered no new mechanical issues and no life-threatening incidents to hold her back.

With spring giving way to summer in the southern hemisphere of Mars, the dust in the atmosphere lightened a little and even though the solar-powered rover was taking on some of that dust as it settled out, it still was able to maintain production of 500+ watt-hours, about half her full capability, plenty of energy to work and drive on to Solander.

"'Boring theater is bad theater,' as they say. 'But boring life is good life,'" offered Callas.

In that context, Opportunity had a good life on Mars in February 2013.

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

When February dawned at Meridiani Planum, Opportunity was completing her check-out of the newberries at Flack Lake on a target the team labeled Fullerton2. The investigation consisted of the rover making multiple off-set observations from a high concentration of newberries to a low concentration "to try and tease out their composition," as Squyres put it, much like the team did with the tiny white veins in Whitewater Lake in January.

From Eagle to Endeavour

This image of Endeavour Crater was taken by the Malin Space Science Systems' Context Camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). The yellow line on this map shows the route Opportunity took from Eagle Crater, where the robot field geologist landed in January 2004 (upper left) to a point about 3.5 kilometers (2.2 miles) from Endeavour Crater. Solader Point, where the teams hope Opportunity will spend her next Martian winter, which begins later this year, is more than half-way from Cape York to Cape Tribulation, where a motherlode of clay minerals were discovered by the CRISM instrument onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and which the rover will likely groundtruth later in its mission at Endeavour.NASA /JPL-Caltech / MSSS

On Sol 3209 (February 1, 2013), the rover used her Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT) to brush Fullerton2 and then took a series of pictures with her microscopic imager (MI) for a mosaic, following it with the usual overnight integration with her alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) to analyze their chemical composition.

"It looks like the newberries are not distinctly different and as far as we can tell from that investigation are compositionally similar to the matrix," said Arvidson. "The blueberries are hematitic concretions in the Burns Formation, but the newberries seem to have much more of an affinity for the rock around them, which are all basalts and variations on basalts. The issue is we don't have a controlled laboratory experiment because we have dust on them and they're rough and we can't brush them. What we can tell is the null hypothesis works. They're not that different compositionally than the matrix, and not like the Shoemaker Formation, more like the Whitewater Lake stuff," he said, where the most newberries have been found.

Although Squyres is advocating maintaining an open mind, Arvidson, for one, still believes these mystery newberries are accretionary lapilli that have just rained out of the atmosphere during a volcanic eruption. But they could be concretions of a different kind than the blueberries, or impact spherules, or perhaps devitrification spherules as previously reported in the MER Update. Time and more research will tell.

What's really interesting is, if you look at the pictures that Curiosity has been sending home of Glenelg and Yellowknife Bay, it would appear that it is roving around an environment that is very similar to Opportunity's present digs.

Once her work was done at Flack Lake, Opportunity went in search of the contact between the Whitewater Lake stuff and Shoemaker Formation breccias, said Arvidson, first driving north for 35.5 meters (about 116 feet) on Sol 3212 (February 4, 2013) toward an outcrop the team nicknamed Fecunis Lake. The following sol, the rover bumped into position with a short 4.5-meter (15-foot) drive to position herself for some in-situ work there, brushing the target with her RAT, then taking a series of pictures for an MI mosaic on Sol 3214 (February 6, 2013), and following that with the usual multi-sol APXS placement to analyze its chemical composition.

As the second week of the month was underway, Opportunity bumped back on Sol 3216 (February 9, 2013), to image the brushed Fecunis Lake with her Panoramic Camera (Pancam) and then logged a 16-meter (52-foot) drive to the west, toward another new outcrop called Maley on Sol 3216 (February 9, 2013). Three sols later, 3219 (February 12, 2013), the rover bumped in 1.8 meters (about 5.9 feet) to better position herself.

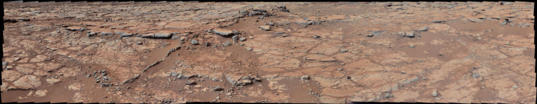

Flack Lake

Opportunity spent the first part of February 2013 finishing up work on an outcrop dubbed Flack Lake, where it condiucted an investigation into the newberries, small mystery spherules that look somewhat like the hematite-rich blueberries the rover found on landing in eagle Crater, and all over the Meridiani plain – except, so far they appear to be nothing like them at all.NASA / JPL-Caltech

The robot field geologist was to have performed a very small turn to position her instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm on Sol 3221 (February 14, 2013) so that she could reach a chosen surface target on Maley, but a Deep Space Network issue prevented the command sequences from reaching the robot field geologist.

When the MER scientists subsequently viewed the pictures Opportunity sent home, they found an acceptable target within reach, negating the need for a turn. So, on Sol 3224 (February 17, 2013), the rover used her RAT to brush that surface target, and then followed with an MI mosaic and APXS integration.

"Both Fecunis Lake and Maley look transitional between Shoemaker stuff we saw a while ago on other parts of Cape York, and Whitewater Lake. The higher up you get in this section [of Matijevic Hill], the more it looks like a breccia and the newberries disappear," said Arvidson, elaborating on what Squyres said. Interestingly, he added: "It looks like Shoemaker Formation texturally, but the composition is a little bit different. That's what we have in terms of observations."

This kind of transitional or gradational contact reveals something about the dynamics of the emplacement of the ejecta. "It's a very violent process, lots of rock moving around at very high speeds in a very short period of time, and some things get mixed up together," said Squyres.

Added Arvidson: "It tells me we are looking at a complicated chunk of the ancient crust that has been faulted [fractured] and it's not all the same composition or same texture."

The search for a defined contact on Matijevic Hill ended with Opportunity's work at Maley. From there, the rover drove to the southeast approximately 36.5 meters (120 feet) on Sol 3227 (February 20, 2013), toward the rock the team dubbed Big Nickel during the rover's geologic survey of Matijevic Hill in October-November of last year.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS

From the other side of Mars

Curiosity used its right Mast Camera (Mastcam) to take the telephoto images combined into this panorama of geological diversity, from her position in the shallow Yellowknife Bay depression in Gale Crater, on the other side of the planet from Opportunity. The mosaics have been white-balanced in this picture to show what the rocks would look like if they were on Earth. Look familiar?On Sol 3230 (February 23, 2013), Opportunity turned her wheels for 5 meters (approximately 16 feet) attempting to scuff, or basically drive over the surface target appropriately named Boxwork. "Big Nickel has beautiful boxwork veins we had a plan to try to grind some of these veins with a wheel, but because we were on 12-degree slope there was too much slip and we missed the target," said Arvidson.

It was a little like Spirit's struggle at Pot of Gold back in 2005 when that rover was hiking up Husband Hill and first rolled into West Spur. "It was a mess, because we were slipping all over the place," remembered Arvidson. "This was a similar situation, so we decided, to approach it, do MI and APXS, and then get out, because we need to get on the road."

That's exactly what Opportunity did. On Sol 3233 (February 26, 2013), the rover made a 1.3-meter (4-foot) bump to set up for some in-situ work with a specific target called Lihir on Boxwork in the area that was to have been scuffed and began work. By Sol 3234, she was analyzing the chemical composition of the target with her APXS, said Nelson.

The following sol, 3235, (February 28, 2013), however, when the rover was to wrap up on Lihir and move on, she experienced another "amnesia" event or fault in her Flash memory; therefore, postponing that plan until Monday, March 4th, according to Stroupe. "The rover is fine," she added. "We're just set back a couple of days."

The good news and the bad news on the amnesia issue, as reported in last month's MER Update, remain the same: it can be fixed, but not now. "The fix is to reformat the Flash and that's what we did on Spirit, but the problem is it's intermittent," Nelson reiterated from last month. "So, if at the time you do the reformatting that troublesome sector is working just fine, then even after reformatting it will continue to fail because the software didn't read it as bad," he explained. It has to get really bad before we can reformat the Flash successfully."

Boxwork on Earth

Opportunity began investigating some boxwork structures at a rock called Big Nickel during the last week in February. This picture shows boxwork that formed on Earth, in Wind Cave, Hot Springs, South Dakota. Boxwork is an uncommon type of mineral structure on Earth. It is created by the removal of bedrock, specifically erosion, rather than as a secondary deposit or accretion.USGS

"Right now, Opportunity's "amnesia" is "mild," said Callas. "We have medicine on the shelf if we need it."

So as February came to a close, Opportunity stayed put at Big Nickel and took her medicine. The plan had been for the rover to drive that same first sol in March back to Kirkwood or a place like Kirkwood with a varying array of blueberries to conduct one more experiment to try and determine more about their composition. That will likely happen once the Boxwork scuff is finished. "We want to test the idea that there might be a little bit of hematite in the newberries, said Squyres. "We know that the blueberries out on the plains are very rich in hematite. The newberries aren't anywhere near that rich in hematite but they could have a little."

With the Mini-TES and M"ossbauer now out of commission, it's more difficult to discern hematite. But hope is not lost. "If you go back to geology 101, one of the very first things they teach is a streak test," said Squyres. "You take different minerals and rub them on a hard white surface and as you grind them you get different colors. Some minerals don't leave a streak and others leave a streak that looks like the mineral. Hematite is an interesting one, because gray hematite leaves a red streak, a brick red color. The reason for this is you're producing very, very fine grain particles and fine grain hematite is reddish in color," he explained.

Way back, nine years ago, in Eagle Crater, Opportunity would occasionally encounter a blueberry during its first RAT grinds into the sulfate-rich sandstones at Eagle Crater and other rocks at the Meridiani site and in the process wound up conducting kind of accidental streak tests. "After grinding up even a single blueberry, we saw that the RAT cuttings around the RAT hole were this vibrant brick red," Squyres noted. "So we know from experience that if you use a RAT to grind into the material containing hematite, you get cuttings that are bright red. So we're going to do a little light RAT grind into a dense concentration of newberries and we're going to take a pic of the cuttings with Pancam and we'll see what we see. It's a streak test. It's geology 101."

Why look for hematite in the newberries if they're so different than the blueberries?

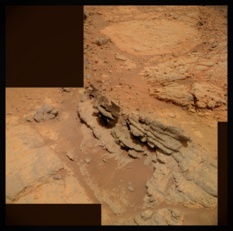

Kirkwood-Whitewater Lake

This picture is one of the first Opportunity took on arriving at the base of Matijevic Hill. The layered, sinuous-shaped outcrop the team dubbed Kirkwood dominates the center of the image. Just behind it, in the top part of the image is the fainter, circular, "slabby" flatter rock called Whitewater Lake, which Opportunity groundtruthed and the MER scientists concluded is part of a larger unit and the bearer of the phyllosilicate or smectite clay mineral signature detected by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU / S. Atkinson

"The idea is that something is cementing the outsides preferentially and it might be hematite or it might just be silica or some kind of sulfate but at such a low concentration we won't be able to tell," said Arvidson. "If there is hematite in the crunchy outside layer, it should turn bright red."

The question of how the newberries formed is still open for debate. "Imagine you have a lot of melt moving through the atmosphere from an impact or a volcanic eruption that produces the same kind of cloud of dispersed material, a crunchy exterior could mean conditions got a little cooler and conductive to formation of a little oxidation and you just dumped out a little tiny bit of iron oxide or silica or gypsum at the end," offered Arvidson. "We'd have to go through the calculations to kind of simulate this, but just changing the conditions, the temperature, the oxygen fugacity, the kinds of gases that were present, you can concoct a story that will make crunchy outsides and soft insides."

"The boxwork and the newberries are currently the main items still on our to-do list," said Squyres. Which, of course, doesn't mean Opportunity won't find something else that the scientists want her to check out before leaving Cape York. But the exit plans for Opportunity are in the works.

At JPL, Tim Parker and Matt Golombek have been working on a proposed 2.5-kilometer route for Opportunity that zig-zags across Cape York, through Botany Bay, then diverts to the west for the rover to take in Nobby's head, and by some craters en route to Solander Point. A first "draft" was reviewed at the end of sol meeting on Wednesday, February 27. "It's a little further than the 2-kilometer distance we thought previously, but well within the envelope of the capability of the vehicle," said Callas.

Other team members want Opportunity to put the pedal to metal and get to Solander as quickly as possible, supporting a more direct route that's been dubbed the "rapid transit."

"These are "just proposals," underscored Parker. "There is a handful of people who are looking at various ways that we might go. And, like always, whatever route we take, we will be reactive to what we find as we go, just like when we left Victoria and headed toward Endeavour."

RAT tailings

Way back in the early days of the MER mission when Opportunity would grind into a "blueberry" it would leaves red tailings, as visible in the image above. While the science team believes the "newberries" at Endeavour Crater are distinctly different than the blueberries, it also plans on conducting a streak test on the "newberries" to see if by any chance they leave even a tiny bit of red tailings behind. That would mean the outer "crunchy coating of the newberries contains a bit of hematite. Stay tuned for the results.NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

This much is certain: a route will be chosen soon if the MER team is to have Opportunity on the road and driving south by May. "The only alternative is Greeley Haven," said Squyres. "But nobody's keen on doing that because we spent a whole winter there and we'd like to go some place new and different. There's pretty strong sentiment to wrap up Matijevic Hill soon and be on our way," he acknowledged. "I'm not making any promises, but that's the desire of the team."

What could stop the team and keep Opportunity at Cape York?

"We could find something puzzling or fascinating that could cause us to linger here for a while," said Squyres. "I always, always have to stress that our decisions are discovery driven and new information could cause plans to change. It's always good to have a plan, but you've got to be flexible."

Solar conjunction comes around in April and Opportunity will stand down for much of the month, from April 8th-26th. "We're going to send up a minimal science campaign for the rover to do during conjunction, probably mostly imaging, and after that we'll be able to really get on the road," said Stroupe.

The rover may hang out around Cape York during conjunction, although, depending on what happens during the first half of March, there is some talk of heading down Matijevic Hill to check out a few other targets before the stand down. "The scientists are still not quite sure of all they want to do on the way out of here," said Stroupe. "It's possible we could be completely done in a couple of weeks ready to start the long trek just prior to conjunction." Or not.

In any case, from the looks and talk of things, Opportunity should pretty much be done with her work on Cape York before conjunction, leaving her ready, willing, and able to hit the road the last week of April.

At February's end, Opportunity only had about 307 meters to go to overtake the driving distance record of 35.89 kilometers (22.03 miles) established by Apollo 17 in 1972. It would seem that the "silver medal" for the longest distance of surface travel of any extraterrestrial vehicle is well within reach, even though no rover ever set out to set a record.

"If our goal had been to break distance records we would have done it a long time ago," Squyres pointed out. "What you do is you operate these vehicles as best you can in the service of the science and whatever happens is what happens. If in the end the distance we cover is greater than some other vehicles, well it's testimony to the quality of the hardware that was built by our JPL engineers. But we're doing the same thing the Apollo guys were doing and the Lunokhod guys were doing and that's exploring. Nobody was out to set a record."

In any case, Opportunity is expected to take "the silver" in the not too distant future, leaving the MER with only the Russian Lunokhod 2 record of 37 kilometers (23 miles) to best, which the rover can do en route to Solander Point. "This is something we've been really looking forward to as sort of that stretch goal for a long, long time now and now it looks like it's really within reach and that's just remarkable," said Stroupe. "We are incredibly excited and very proud."

NASA / JPL

Solar conjunction coming soon

About every 26 months, when Mars and Earth are on opposite sides of the Sun, communication between the two planets is disrupted. During the days surrounding such an alignment, which is called a solar conjunction, the Sun can disrupt radio transmissions between the two planets and so the MER team will stand down from all but a few minimal communications, from April 8-16th this year, and Opportunity will go on 'autopilot' working a science light campaign.As the Martian summer heats up Endeavour, the dust of spring is beginning to dissipate and the Tau or opacity of the sky overhead, dropped in February from around 0.926 to 0.817. While the rover's dust factor worsened, from 0.643 to 0.594, the robot field geologist was still producing upwards of 500 watt-hours at month's end and so the future for now continues to look bright for this explorer.

The rover handlers, for their part, are making sure Opportunity will be "warmed up" and ready for the long traverses to come. "We started babying that right front wheel a little more to try to protect it," said Stroupe. "The steering motor is broken so the wheel is locked in the steering angle and has to work harder than the others. We're babying it to make sure it lasts as long as possible."

It's a good thing, because Opportunity seems bent on having places to go, things to see, and miles of terrain to go at Endeavour. From orbital imagery, the terrain between Cape York and Solander Point looks like it will make for good driving, somewhat like the plains between Victoria Crater and Endeavour. "Mars could always throw a surprise at us, but at this point we don't anticipate this journey to be much different than the one we made to get here," Stroupe offered. "It'll be nice to do nice long drives again, day after day."

NASA / JPL-Caltech / S. Atkinson

The vista from February 2013

This photograph was processed from a series of images that Opportunity took in mid- February 2013 with her navigation camera (Navcam). Stuart Atkinson, of UMSF.com, processed it and we present it here as a visual tribute to another solid month of MER exploration.Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth