A.J.S. Rayl • Oct 03, 2012

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Finds Thrill of Newberries on Matijevic Hill

Sols 3060 - 3088

On reconnaissance of Matijevic Hill, Opportunity has driven right into another Martian mystery, compete with new kinds of "berries," tiny white veins running through two distinctive outcrops of rock, and orbital data indicating that somewhere here clay minerals are hiding, all of which has put the Mars Exploration Rover (MER) mission back in the science spotlight and made for another September to remember at Meridiani Planum.

The discovery of the tiny spherules or "berries" in the close-up images and detailed color panoramic pictures have had the science team brimming with theories and almost effervescing with excitement for the past two and a half weeks. "These are something different," said Steve Squyres, MER principal investigator, of Cornell University. "We have a wonderful geological puzzle in front of us."

Other than their shape, these "berries" bear no resemblance to the hematite "blueberries" that Opportunity found throughout her trek across the plains of Meridiani, and which are evidence for the past water the rover came to find. "They are not hematite blueberries," Squyres said with assurance. "I've been calling them 'newberries,' for lack of a better term.

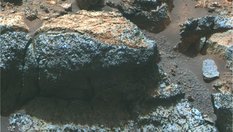

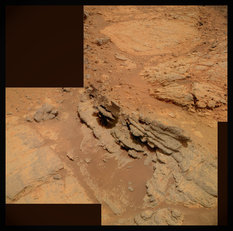

Newberries discovered at Kirkwood

Opportunity took the pictures that went into this close-up mosaic with her microscopic imager (MI) on her Sol 3064 (Sept. 6, 2012). This mosaic combines four images, and the view covers an area about 6 centimeters (2.4 inches) across, at an outcrop called Kirkwood in the Cape York segment of the western rim of Endeavour Crater. The individual spherules are up to about one-eighth inch (3 millimeters) in diameter. Stuart Atkinson processed the raw data, enhanced it, and produced this striking picture that shows the berried newberries that has the scientists shaking their heads. For more of Atkinson's work, please see his Road to Endeavour blog.NASA / JPL-Caltech / S. Atkinson

Opportunity began its reconnaissance of the recently christened Matijevic Hill about four weeks ago, at a finned outcrop the team finally named Kirkwood. Actually, it was this wild looking, sinuous-shaped bedrock that lured the scientists and Opportunity off their path. The rover had been on a scouting trek, driving south along the inboard side of the Cape York segment along of the western rim of Endeavour Crater, looking for just the right outcrop that might be the bearer of the clay minerals detected from orbit.

With the fin, the feel, the orbital data highlighting this particular area as the "sweet spot," as Ray Arvidson, deputy principal investigator, put it, the MER team decided in late August that the rover should detour from the survey campaign, "take a hard right turn," as Squyres described it, and head west, up into an area that overlooks the 22-kilometer (14-mile) wide Endeavour Crater. It is this area, the MER team announced September 28th, that is named in honor of Jake Matijevic (1947-2012).

Jake Matijevic (1947-2012)

Jacob "Jake" Matijevic, one of the original Mars rover pioneers. He worked at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) since 1981 and was involved in the creation and success of every American Mars rover. He led the engineering team for the first Mars rover, Sojourner that landed in 1997; was a member of the original group that proposed MER and then led the engineering team for Spirit and Opportunity for several years before and after their landings. And at the time of his death in August, he was chief engineer for surface operations systems for Curiosity.JPL-Caltech

Jake led the engineering team for MER for several years before and after their landings, and was, in effect, one of the creators of Spirit and Opportunity. As the systems engineer, he had been deeply involved in the evolution of MER and knew everything about how the twin robot field geologists work. He worked at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where all of the American Mars rovers have been designed and 'born,' from 1981 until he passed away unexpectedly in August, at the age of 64. Jake had been a part of every American Mars rover team, leading the engineering group for the first Mars rover, Sojourner. At the time of his passing, he was serving as chief engineer for surface operations systems for Curiosity.

"If there is one person who represents the heart and soul of all three generations of Mars rovers – Sojourner, Spirit and Opportunity, Curiosity – it was Jake," noted John Callas, MER project manager at JPL.

"It had to be some place really special," said Squyres before the announcement was made public. "We wouldn’t have gotten to Matijevic Hill, eight-and-a-half years after Opportunity’s landing, without Jake Matijevic."

Situated on the oldest Martian terrain the rover will traverse, Matijevic Hill is already proving to be one of, if not the most scientifically significant places the MER mission has visited in eight years, eight months and counting of roving Mars. Already there are rich hints that this place will offer a window deeper into Mars past and reveal secrets about a more ancient Mars, a Mars that was, by most planetary scientistists' accounts, wetter and warmer and more like Earth.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU/S. Atkinson

A partial view of Matijevich Hill

On September 28, 20912, NASA-JPL announced that the scientifically rich site that Opportunity is now exploring is being called Matijevich Hill in honor of Jake Matijevich. "We wouldn't have gotten to Matijevic Hill, eight-and-a-half years after Opportunity's landing, without Jake Matijevic," said MER P.I. Steve Squyres.Although Opportunity has been relegated of late to the shadows of the bigger, badder, Curiosity, the newberries represent an important science finding, especially coming this long into an expedition that was originally scheduled to last three-months. And on September 14th, NASA-JPL issued a press release on to announce the strange new discovery.

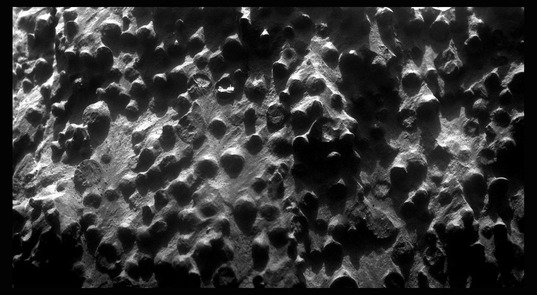

"Kirkwood is chock full of these little spherules," Squyres said. "We've never seen such a dense accumulation of spherules in a rock outcrop on Mars."

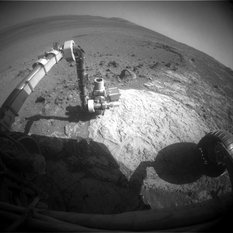

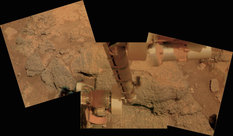

Opportunity focuses on newberries

Opportunity managed to snap the images for this self-portrait with her stereo panoramic camera (Pancam), which in effect are the rover's "eyes' atop her mast. The picture shows that she is positioned for taking close-up pictures of the newberries on Kirkwood with her microscopic imager. Stuart Atkinson processed the raw data and produced this color picture, in near to true Martian color.NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU/S. Atkinson

The newberries, which measure as much as 3 millimeters (one-eighth of an inch) in diameter, appear to be "crunchy on the outside, and softer in the middle," he said. They are different in concentration, structure, distribution, and composition from the blueberries. Their apparent basaltic nature precludes the presence of iron oxide. “But everything on Mars is close to being basaltic, so that doesn't tell us a whole lot,” he noted.

One possibility is that the newberries are concretions, but of a different kind than the hematite concretions or blueberries. Another theory is that they were formed by an impact, and not necessarily from whatever made Endeavour Crater. Or they could be accretionary lapilli, little volcanic hailstorms that form in the cloud of debris that develops in a volcanic explosion. “Pompeii is buried in the stuff,” Squyres pointed out.

"We're very much in the mode of multiple working hypotheses right now – a bunch of different ideas for what they could be," continued Squyres. "We're not pursuing any one but making observations that will enable us to distinguish among all of them, and I'm advising the team to keep an open mind and let the rocks do the talking."

Meanwhile, nothing much, save a planet encircling dust storm in 2007 maybe or the last Martian winter, has ever kept Opportunity from roving. Mystery or not, during the second week of the month, the robot field geologist moved on, just a little ways up and around Kirkwood to a flatter, somewhat circular, lighter toned outcrop called Whitewater Lake.

"A reconnaissance of the site is the first thing you do in geologic fieldwork you do, and that's what we're doing," Arvidson explained. "We've done the initial reconnaissance on Kirkwood and then we bumped uphill to the west, and we're now sitting on an outcrop called Whitewater Lake. But we're still in the reconnaissance mode. We’re getting a taste of Kirkwood and now a taste of Whitewater Lake."

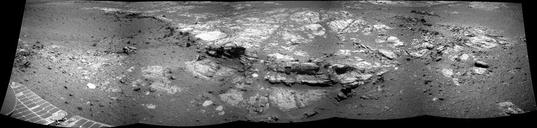

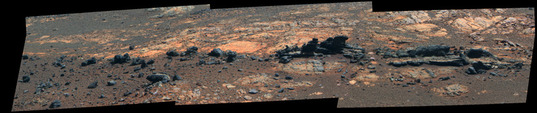

Kirkwood and Whitewater Lake

Opportunity took the images for this rich photograph of her September 2012 worksites. In the middle of the picture, you can see a part of the layered, sinuous-shaped outcrop the team dubbed Kirkwood. Just behind it, in the top part of the image is the fainter, circular, "slabby" flatter rock called Whitewater Lake, which Ray Arvidson, the MER deouty principal investigator, believes may be the bearer of the phyllosilicates or clay mineral signature detected in recent years by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) on board the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU/S. Atkinson

This slab of rock may be harboring the clay minerals. "We bumped up to Whitewater Lake, because this is a pretty extensive outcrop – and it might be – we thought – because it's aerially extensive, might be the carrier of this phyllosilicator clay mineral signature we're seeing from CRISM," confirmed Arvidson, who is also a co-investigator on the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars, which is onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). Plus, earlier Panoramic Camera (Pancam) imagery indicates there is mineral hydration, a sign of water, in this rock.

Last week, Opportunity used its rock abrasion tool (RAT) to grind into Whitewater Lake. As for the presence of clay minerals?

"It’s too early to say," said Squyres.

And so the mystery plot thickens. And with "very small, light-toned veins" running through the Kirkwood and Whitewater Lake outcrops, it thickens some more. "Those tiny veins are on our list too – we have a long to-do list here," Squyres said. “We're going to work our way through Matijevic Hill very carefully and figure it out."

There is good news in the fact that the RAT is still functioning "quite well,” reported Gale Paulsen, who is working on RAT-ops on Opportunity and is a systems engineer at Honeybee Robotics, the New York-based company that made the instrument. The specific grind energy during the latest grinds, he noted, "is similar to most rocks we've ground with Opportunity, which bodes well for the RAT bit."

The plan ahead is for Opportunity to check out other sites around Matijevic Hill and "move back and forth and up and down along the outcrop to really understand the structure and the stratigraphy and how the layers combined, and the composition and the variation in composition," Arvidson said.

Opportunity, for her part, is apparently feeling fine, certainly enough, it would appear, to compete with Curiosity for the science spotlight. "This rover is chugging along wonderfully," said Bill Nelson, chief of the rover engineering team at JPL. "The temperatures have come up a bit, to where we like to see them – up to about 20 degrees Celsius (68 Fahrenheit) in daytime and dropping to -10 C (14F) or so overnight, which is a nice place to operate."

It helps when Mars cooperates. The atmospheric opacity of haze from dust in the sky overhead "has been pretty well behaved," Nelson noted. "The dust factor [on the rover] is continuing to go down, as you would expect, but not at anything out of the ordinary rates. We've got plenty of power, the rover is running 550 watt-hours per sol," which is more than half of its full capability. "And we’re entering what is traditionally a fairly benign part of the year. We have no new failures. The vehicle is in as good health as one could expect, and everything looks really good."

With the focus heavy on science, Opportunity didn't really drive much in September, and its odometry remains at 35,047.47 meters (21.78 miles), Nelson added. "We’ve done our periodic maintenance sequences and so forth, but it has really been science’s show and we’ve been happy to have it so bland, if you will," he said. "Bland is good."

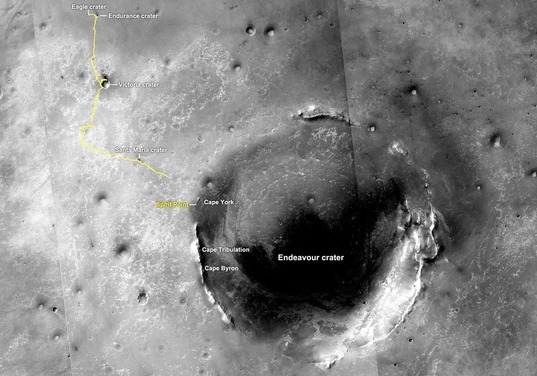

The path to Endeavour

The yellow line on this map shows the route Opportunity took from Eagle Crater, where the robot field geologist landed in January 2004 (at the upper left end of the track) to a point about 3.5 kilometers (2.2 miles) away from the rim of Endeavour Crater. The rover arrived at the 22- kilometer (14-mile) diameter hole in the ground in August 2011, after a three-year journey from Victoria Crater and entered by way of Spirit Point, an area named after her twin "sister," which stopped communicating in March 2010.NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

With the spring equinox in the southern hemisphere of Mars occurring September 30, the amount of sunshine that Opportunity can access for solar power will now continue increasing for several months. "We are looking forward to productive spring and summer seasons of exploration," said Callas.

That doesn't necessarily mean the rover will be putting the pedal to the metal anytime soon. "We always knew the mission would begin again when we got to Endeavour and ever since then – more than a year now – it's been one new thing after another," Squyres reflected. "Matijevic Hill is such a scientifically interesting and important place that we're going to be here until we've done the best job we can do with it."

In other MER News

MER Mission Team Honored with Haley Award

The MER Mission Team was awarded the Haley Space Flight Award for developing "new techniques in extraterrestrial robotic system operations to explore another world and extend mission lifetime." MER Project Manager John C. Callas, accepted the award on Sept. 12, 2012, during the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) Space 2012 Conference and Exposition, held in Pasadena, CA.AIAA

The MER mission team was awarded the Haley Space Flight Award on September 12th for developing "new techniques in extraterrestrial robotic system operations to explore another world and extend mission lifetime."

"On behalf of the many hundreds of scientists and engineers who designed, built and operate these rovers, it is a great honor to accept this most prestigious award," said Callas, who received the award for the team during the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) Space 2012 Conference and Exposition, held in Pasadena, CA.

"It is especially gratifying that this comes right as Opportunity is conducting one of the most significant campaigns in the eight-and-a-half years since landing," Callas told the audience. "We still are going strong, with perhaps the most exciting exploration still ahead."

The award is presented for outstanding contributions by an astronaut or flight test personnel to the advancement of the art, science or technology of astronautics and the MER mission team is in the best of company. Past recipients include Alan Shepherd, John Glenn, Thomas Stafford, Robert Crippen, Kathryn Sullivan and the crew of space shuttle mission STS-125, which flew on the last shuttle mission to the Hubble Space Telescope in 2009.

In related news: Bobbie Has Left the Lobby

Bobbie has left the lobby

Bobbie J. Fishman, who served as "the face of JPL" and a gatekeeper in JPL's Visitor Center and lobby for 33 years, retired this month. A friend and supporter of the MER Update, Bobbie was always the first best thing about going to JPL and her absence will be conspicuous for a long time to come.JPL

On September 28th, Bobbie J. Fishman – known variously as "JPL's own diva," "rock star," "artist formerly known as a symbol," and "the face of JPL" – walked out of the center's visitor lobby doors for the last time as a full-time Lab employee into retirement and the next chapter in her life.

The afternoon before her departure, JPL employees, including Director Charles Elachi, and other invited guests packed into Von Karman Auditorium for a celebration of her service. There were so many people that the overflow spilled into the museum and the patio – and it's no wonder.

Bobbie arrived at the Lab in May 1979 and soon became a fixture known as Bobbie in the Lobby. For the next 33 years, almost every single visitor – from scientists to journalists and authors, rock stars and celebrities to American heroes and members of student tour groups – each was greeted by Bobbie, "processed" with her calm efficiency, and directed into the inner sanctum of the Lab with a signature wave and smile. All told, more than 250,000 people are estimated to have been admitted through this heralded JPL gatekeeper.

"Bobbie owned her job," noted one of her supervisors. Indeed, she did. Past that, she became "arguably JPL's greatest ambassador," as another boss put it.

Through all the years of launches, landings, interviews, demonstrations in Mars Yards, press conferences, and special events, for this rover scribe and so many other regular visitors, Bobbie was always the first best thing about going to JPL.

Now life marches on. It's almost impossible right now to imagine what going to JPL without Bobbie in the Lobby will be like. But this much is true: the essence of her subtly profound presence for so many years will linger there in the lobby, for a long, long time.

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

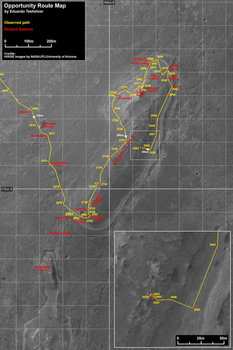

Opportunity route map

This route map shows Opportunity's travels up to its Sol 3071 (September 13, 2012), and the rover's approximate current location at Kirkwood, a wild looking outcrop on the inboard side of Cape York. This image was produced by Eduardo Tesheiner, of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, who created it from images taken by cameras onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. As this map indicates, September 2012 was devoted mostly to scientific and not driving.NASA/JPL-Caltech/UA/MSSS/E.Tesheiner

As September dawned at Meridiani Planum, Opportunity was on approach to Kirkwood, the finned outcrop.

The rover had been driving south surveying all the exposed outcrops, first with her navigation camera (Navcam) and then in detail with the Pancam. That fin was the geologic intrigue that caused the scientists to call for a detour from the rover's survey trek along the inboard edge of Cape York segment of the western rim of Endeavour Crater. Not only was the fin "cool looking," as Arvidson describe it, but because orbital data from CRISM had detected phyllosilicates right in this particular area. It was a logical move to the heart of the "sweet spot." So, on Sol 3056 (August 28, 2012), the team decided to have Opportunity turn to the right and head west to the outcrop that has since been dubbed Kirkwood.

The weather was fine enough in Meridiani Planum, if a little hazy – an atmospheric opacity or Tau of 0.658, and the rover began the month with plenty of energy, registering power levels hovering around 550 watt-hours.

On Sol 3060 (September 1, 2012), Opportunity drove the final 6-meters (20-feet) to complete her approach to Kirkwood. The next sol, the robot field geologist lifted her instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm so that she could get an unobstructed view of potential in-situ targets with her Pancam.

Then, on Sol 3063 (September 4, 2012), Opportunity bumped into place with a short 1.7-meter (5.6 foot) move, so that she could easily reach the chosen surface targets. She finished out the first week of the month by taking pictures needed for an MI mosaic of Kirkwood on Sol 3064 (September 6, 2012), and then placing her APXS on the target to try and determine its composition.

The plan called for Opportunity to continue with her in-situ science campaign at Kirkwood in the second week of September, but on Sol 3066 (September 8, 2012), the robot field geologist experienced an X-band fault. The X-band, which basically consists of radio waves at a much higher frequency than radio waves used for FM stations, is the way Opportunity communicates directly with Earth and it is the primary pipeline for the team's commands.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU

Kirkwood in false color

Opportunity took the images that went into this panorama of the sinuous-shaped Kirkwood outcrop in the area now known as Matijevich Hill with her Pancam. This photograph was processed by the Pancam team at Cornell and Arizona State University (ASU).Because of the seasonal geometry, time of day and rover tilt, the ops team at JPL knew there was a risk that Earth might be too low on the horizon for the rover's high-gain antenna to track. Turned out that a small error in the rover's tilt knowledge resulted in the track of the Earth dropping too low at the end of the X-band pass.

"Since the rover can be pretty tilted and was, the deck was the controlling factor here," said Nelson. "We went partway through our comm window before this was identified. That gave us time to get most of the bundles [of rover commands] up. In a case like this, if it determines it can't move, it stays there, but does not declare the fault for another 4 minutes. And, during those 4 minutes it's expected to downlink the e-v-r's [event records] before it declares the fault and stops the window. The response in this case is to stop the window, but not to stop all the sequences."

The combination of not having the fault until partway through the window and having these other 4 minutes enabled the team to get all the plans up and onboard the rover before the window was terminated. "We had all the sequences onboard and they were running, so we were able to get everything accomplished that we wanted to get accomplished," confirmed Nelson. “We brought the data back through the UHF [via the Mars Odyssey orbiter] so we didn’t have problems getting that data. We then recovered from the fault on Sol 3069 (September 11, 2012, before the next uplink, with real-time commands; therefore, this was kind of invisible to science team members, though it created some consternation among the engineering side," he said, with a wry smile.

Newberries on Kirkwood

Opportunity used her Pancam to take the images for this mosaic of part of the Kirkwood outcrop, which the rover checked out in early September 2012. Stuart Artkinson rendered it here in near Martian Technicolor. Click to enlarge to see the newberries embedded all around the outcrop. For more of Atkinson's work, please see his Road to Endeavour blog.NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU/S. Atkinson

Since Opportunity received the MER team's commands successfully, the rover kept on keepin' on, not so much as missing a beat. That same sol of the fault, 3066 (September 8, 2012), the robot field geologist raised her robotic arm to get a clear camera shot of the targets right in front of her, and began taking the pictures that would soon have the scientists on the edges of their seats.

On the next sol, she brushed the target with her RAT, took the necessary pictures for another MI mosaic, and then put her APXS on the brushed surface. "We just attempted a brush on that," said Honeybee's Paulsen. "It was a pretty difficult target and it looked like we were making some contact, but it was hard to see how much of a brush we got."

Even so, the MI image Opportunity sent home had the researchers almost giddy with wonderment. "This is one of the most extraordinary pictures from the whole mission," Squyres said of the close-up, black and white image showing dozens of spherules, each on average about 3 millimeters (one-eighth of an inch) in diameter. "You've seen the images. We immediately thought of the blueberries."

These newberries, however, differ in several ways from the spherules forever to be known as "blueberries," which the rover found at her landing site in early 2004 and in many other locations to date. These spherules, for starters, do not have the high iron content of Martian blueberries and thus are not comprised of hematite.

The high iron content is what led the scientists to the hypothesis that the blueberries are actually concretions, small little spheres formed by the action and motion of mineral-laden water inside rocks. It was a big deal discovery, because hematite is what brought the MER mission to Meridiani Planum, and the blueberries are solid evidence of an ancient wet environment on Mars, which the MER mission was charged with ground-truthing.

"But these newberries are not rich in hematite; otherwise, we would have seen a high iron signal in the APXS. And the matrix in which they are embedded is not [made of] sulfates; otherwise, we would have seen high sulfur in the APXS," Squyres said, recounting the analyses.

"They're not hematitic concretions, not like the concretions that we've seen in the regular Burns Formation with the sulfates," Arvidson concurred. "And they're embedded, lots of them, in a matrix that's a lot brighter. Their composition seems to be basalt, so they're not enriched in iron oxide by any means."

That doesn't necessarily rule out the concretion hypothesis though. Concretions are the end result of minerals precipitating out of water and becoming hard masses inside sedimentary rocks. "Concretions can form in all sorts of different kinds of rocks with water precipitating out minerals," Squyres said. The newberries then could be, theoretically, "concretions of a different kind."

They could have formed as a result of an impact, though not likely the impactor that created Endeavour. "There is nothing that we see suggests that these are from the Endeavour impact," said Squyres.

Yet another theory maintains the newberries were formed by wind and erosion. Many of the Kirkwood spheres are broken and noticeably etched away by the wind leaving, ostensibly, the concentric structures that are evident.

Still another hypothesis defines the newberries as accretionary lapilli, "little volcanic hailstorms that form in the cloud of debris that develops out of a volcanic explosion," as Squyres described it. Another notion is that they could be "devitrification spherules that form when glassy materials crystallize producing radiating crystals in spherical structures," he added.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU/S. Atkinson

Kirkwood in Martian Technicolor

Opportunity took the images that went into this panorama of the finned and richly layered outcrop on her approach to the site late in August. The rover took the picture that went into this panorama with her stereo Pancam, and Stuart Atkinson processed them to give us this stunning view."We have multiple working hypotheses, and we have no favorite hypothesis at this time," Squyres continued. "It's going to take a while to work this out, so the thing to do now, what I'm hammering on the team to do, is keep an open mind and let the rocks do the talking. Each of these hypotheses has distinct predictions regarding what you should observe. They're all testable. We will slowly, methodically test our way through all the hypotheses until we've got the one that makes sense."

At this point, Squyres pointed out, the MER scientists don't even know if these rocks are older or younger than the Endeavour impact. "That's one of the hypotheses we have to test too. Are these rocks that were in place before Endeavour or were these rocks that formed after the impact? We've got a long way to go on this one."

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU/S. Atkinson

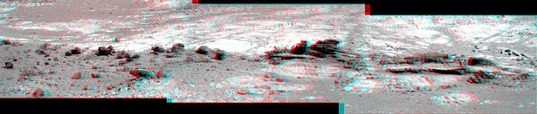

Kirkwood in 3D

Get your blue red glasses and check out Kirkwood in 3D, produced by Stuart Atkinson. Formore of Atkinson's work, check out his blog Road to Endeavour.While the definitive answer to the mystery of the newberries remains to be found, the accumulation of ground-truthing evidence that Opportunity, and twin Spirit in previous years, have returned are bearing out the conventional 'truth.'

"The older you look in the geologic record on Mars, the wetter it seems to have been," said Arvidson. “This is complicated outcrop with a really interesting story to tell about the early crust and crustal processes and also water, so this will take a while," he agreed.

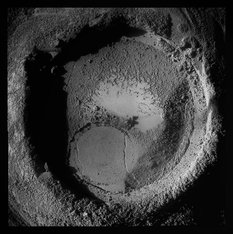

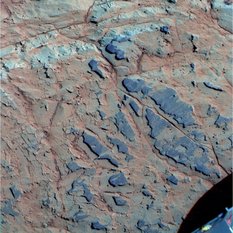

Whitewater Lake up close

Opportunity took the pictures that went into this Pancam image in mid-September 2012. This picture was processed in false color by the Pancam team at Cornell and Arizona State University (ASU) to better show the MER scientists the texture and detail in the rock.NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU

Meanwhile, Opportunity continued with her reconnaissance of Matijevic Hill. "Here's the thing: if you and I were out in the western desert of Egypt and we were doing field work, the first thing we'd do is walk around and scope out what's there," Arvidson offered. "In effect, that's what we're doing at Matijevic Hill. Once we scope out the area and recognize the important components of the outcrops and targets to focus on, then we will go back and begin be the second phase of this campaign," he informed.

"We will undoubtedly come back to Kirkwood, undoubtedly, and move along the length of the outcrop, looking for variations in the density and the patterns of the spherules and trying to find a big aerial exposure of the brecciated part of it, and trying to find a big aerial exposure of these veins so we can get the turret in there to do MIs and APXS' of these different parts of Kirkwood," said Arvidson.

"If you look to the lower part of the Kirkwood outcrop, you can see what appears to be breccia, broken off pieces and there's a matrix of brighter material," Arvidson pointed out. "The outcrop is also fractured and there are slightly brighter veins filling the fractures. We're really interested in these fractures and the vein fillings – that's probably [a sign of past] water. But we don't know what the composition of the veins is yet. We haven't found a fracture that's thick enough to do an APXS on."

Opportunity's most obvious next stop on her immediate reconnaissance mission of Matijevic Hill was a flatter, roughly circular, lighter toned rock just behind Kirkwood from the rover's approaching direction, a rock the team calls Whitewater Lake. "Having completed our initial investigation of Kirkwood, which showed the spherules and told us a few things on what they are not, the next thing to do was to go over and take a look at this light-toned, kind of slabby outcrop just immediately uphill," said Squyres.

On Sol 3070 (September 12, 2012), Opportunity took the short, 3-sided drive around the exposed fin-like outcrop to get to Whitewater Lake. "We're only talking north a little bit and west a little and then came south, kind of like a square U turn," said Nelson. "The rover actually drove, from end point to end point, a very small amount. We looped up through the area."

The next sol, the rover performed a very small turn-in-place to position a high-valued target within reach of her arm. "We bumped to a place that's nice and flat so we could do APXS, brush, APXS, grind APXS," Arvidson recounted.

Despite the ever-present dusty haze in the sky, the rover was producing upwards of 565 watt-hours mid-month with an atmospheric opacity or Tau of 0.689.

Opportunity stayed hunkered down at Whitewater Lake during the third week of September and is there still. "We've been working our way through this one very carefully – that involves APX, MI, RAT brush and more APXS and MI, and RAT grind and more APXS, and MI," said Squyres. "Only when we get the grind done, I think, will we truly know what this stuff is made of. We've got MI images down and so far it looks like a sandstone, a very fine-grained, 100-micron grained, very well sorted sandstone. But, remember, sandstone just means the particles are sand sized. It says nothing about what they're made of."

On Sol 3073 (September 15, 2012), Opportunity took more close-up pictures for another MI mosaic of the surface target dubbed Azilda1, and followed that by placing her APXS on the same target for a multi-sol integration. Three sols later, 3076 (September 18, 2012), the rover used her RAT to brush the surface of a target called Azilda1, then switched to her MI to collect another mosaic, and followed that, once again, with another placement of the APXS.

"The scientists decided the brush wasn’t as good as they had hoped, because there was more surface relief to the rock than thought, so we had the rover move a little closer about one centimeter and repeated the process on a target called Azilda2 on Sol 3078 (Sept. 20, 2012)," said Nelson.

Whitewater Lake post brushing

Opportunity took this picture of the target spot, called Azilda2, on Whitewater Lake after she brushed the spot with her RAT. Stuart Atkinson processed the raw images into this color photograph that shows just how dusty things can get on the Red Planet.NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/ASU/S. Atkinson

As usual, Opportunity took the needed post-brushing pictures for an MI mosaic, then positioned her APXS on the target for an integration to analyze the composition. Again, the results were still not exactly what the team had hoped for. "Although this target did not have a lot of relief, on a microscopic scale it has this ridge down the middle of it, and they were hoping to find a spot that was a little flatter."

So, two sols later, 3080 (September 22, 2012), Opportunity repositioned her RAT by 2.5 centimeters (0.98 inch), and brushed another surface target on Whitewater Lake, slightly offset from the previous Azildas, called Azilda3. Subsequently, the team decided the best of the three was Azilda2, and commanded the rover to re-adjust her RAT for grinding on that spot.

"Whitewater Lake is a soft rock, and it seems to have a dust cover because the composition kind of changes as you brush it and then do the APXS on the brush surface,” Arvidson explained. "We're trying to figure out what it's trying to tell us."

Opportunity went in for the grind on Azilda2 on Sol 3083 (September 25, 2012), successfully boring 0.8 millimeters (0.03 inches) into the rock, then ground another 2.8 mm (0.11 inch) this past weekend, producing a 3.6 mm (0.14 inch) depression overall.

Remarkably, this rover’s RAT is working so well that it seems to have miles and targets to go before it wears out. "Our [previous] bit imaging was a few weeks ago showed that the last grind we did [in Grasberg] didn't cause any noticeable wear, at least based on the way we did the analysis," Paulsen pointed out. "That was good news, because that rock was a harder target than we had seen in a while."

After the Grasberg imaging and analysis, Honeybee Robotics was predicting that Opportunity has "somewhere in the ballpark of eight or 10 grinds, and 20 more brushes," said Paulsen. "There’s plenty more brushes than grinds. Brushes don’t wear down as fast, and brushing can reveal a lot of good information."

Consider the last grind Opportunity conducted on Azilda2. "You can see in the Pancams that [the RAT] did a pretty job of cleaning that target with the brush." Moreover, during grinding into Whitewater Lake this past weekend, the RAT performed at essentially the same energy levels as "most rocks we've ground with Opportunity," something that also "bodes well" for the RAT," said Paulsen. "We will confirm bit wear with images within the next few weeks," he added in a last-minute email.

The RAT's performance would seem to also bolster Arvidson's conclusion that Whitewater Lake is a fairly soft rock.

Interesting – and adding to the mystery of Matijevic Hill – are the multitude of light-toned veins, "tiny little things," as Squyres described them, running through Kirkwood and Whitewater Lake – "which is really interesting," said Arvidson. "We have not yet made a measurement of these things and we don't know what those are made of," Squyres said. "Those are on our to-do list too."

In the midst of her work on Whitewater Lake, Opportunity took a bit of break during the third week of September to look skyward and try to capture pictures of the transits of the Sun of Mars' moons Phobos and Deimos. On Sol 3076 (September 18, 2012), the rover looked up and snapped Phobos – err, tried to. The rover missed the transit "due to ephemeredes" [a table of coordinates of a celestial body at specific times during a given period] "from Eagle Crater instead of the current location," said Nelson.

Opportunity tried again on Soil 3078 (September 20, 2012), this time in hopes of visually recoding both Deimos and Phobos. The Deimos observation, projected to be a kind of grazing transit and marginal at best, didn't happen because "random factors" did not operate in MER's favor. But her second attempt at capturing the Phobos transit was "wonderfully successfully," reported Nelson.

Now, as September falls to October and another sol ends on Mars, Opportunity, who in rover years, passed centenarian status sometime ago, roves on, "the wiser, older sibling who has a lot to teach Curiosity," as Callas puts it. Certainly, this robot field geologist is keeping her team and legion of followers around the world engaged and amazed even after all these years, and the latest Martian mysteries are keeping smiles on the faces of the science team members and engineers alike.

"Everything is going really well," said Squyres. "People are going to have to be patient with us on this one though. I don't want to rush. I don't want to make the mistake of thinking we know what we're looking at because it sort of looks like something we've seen before, and then making a few slap-dash measurements and heading off to the next thing," he said, pausing.

"It's when you see something you don't understand," Squyres added, "that the opportunity for discovery arises."

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / S. Atkinson

Another sol sets at Endeavour Crater

This is art, as in it's not really a real photograph. Although the base image is real, Stuart Atkinson of UMSF.com worked some of his illustrative magic and rendered this imagined view of Endeavour at twilight.Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth