A.J.S. Rayl • Mar 31, 2012

Mars Exploration Rovers Update: Opportunity Gets Energy Boost and Works Through Depths of Winter

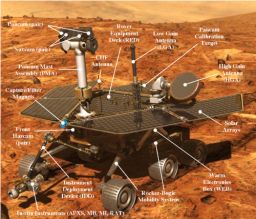

Mars Exploration Rover

NASA / JPL-Caltech / Maas Digital

March came in like a lion and went out like a lamb at Meridiani Planum, Mars: Opportunity felt the cold wind on her solar panels, then "settled" in a little more, working through the depths of its fifth Martian winter, as the team honored one of its own up there, and the Mars Exploration Rover mission logged month number 99 of exploration.

Gentle winter gusts noticed in the last days of February allowed March to literally blow in, clearing off some of the accumulated dust from the rover's solar arrays. The gusty sols gave Opportunity a measurable "bump" in power, boosting the rover's levels to nearly one-third full capacity, allowing the team to breath easy for the next couple of months, at least as far as power levels go.

Opportunity is still parked at the north end of Cape York, along the rim of Endeavour Crater, ensconced in an area the team named Greeley Haven, tilted at about 15 degrees to soak in as much of the Sun as possible. While the projections estimated that the rover's power levels would drop down to less than one-quarter full capacity, the winds of Mars changed that and the robot field geologist was able to work nearly a full schedule throughout the month.

"We're doing a lot better than we thought because of that cleaning event," said Bill Nelson, chief of the rover engineering team at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the birthplace of and mission control for Spirit and Opportunity. "It turned into a series of very small cleaning events, a little every day for several days."

"They were small gusts, totaling up to an 8% improvement in energy production," added John Callas, MER project manager, of JPL. "But we'll take them. It's all moving in the right direction. We're not out of the winter yet, but the worst power levels do seem to be behind us now."

Click to enlarge >

Click to enlarge >Morris Hill

Opportunity took this picture of Morris Hill back on Sol 2827 (Jan. 6, 2012) shortly after parking for the winter in Greeley Haven. Morris Hill is named in remembrance of JPL engineer and MER team member Rich Morris , who passed away last October just one month before his 38th birthday. This image was produced here in color by James Canvin. For more of Canvin's work, go to: http://www.nivnac.co.uk/mer/ Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / J. CanvinMeanwhile, the point of minimum solar insolation – the time of the least sunshine in a Martian year – passed on March 9-10, and winter solstice – the time at which the Sun is at the northernmost point in the southern hemisphere of the planet – occurred this past week and Opportunity can see the light of spring at the end of the proverbial tunnel. "Things will continue to be really cold for a while yet, but I think we'll get through this winter just fine," Nelson said.

Although winter is receding and power levels are above what they were anticipated to be at this time – theoretically at levels where the rover could drive – Opportunity isn't going anywhere for a while. "The plan is to move as soon as we are able to in terms of power, and June is a possibility," said Ray Arvidson, the deputy principal investigator of Washington University St. Louis, who is overseeing the winter science campaign. "It's still winter, and we still have things to do, plus we are parked at a tilt, and we want to have a sufficient amount of power once we move, just in case [the weather] should suddenly change."

In terms of work, March was a near duplicate of February: Opportunity continued conducting radio science tracking passes as a priority, and also focused on taking dozens of close up pictures of the foreground, or bedrock area before it. The robot took every advantage to snap some more of those haunting, Ansel-Adams-like, low-light late afternoon pictures with her panoramic camera ( Pancam ) while waiting to track signals for the radio science study.

Click to enlarge >

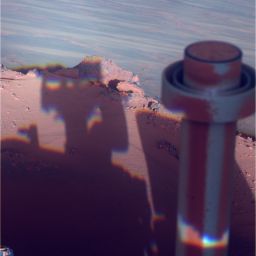

Click to enlarge >Opportunity reflection

Opportunity managed to capture this self-shadow portrait on March 9th, as Mars was just about at the point of minimum solar insolation -- essentially the time in the Martian year of the least sunshine in the southern hemisphere of the planet. The rover appears to almost be reflecting as it looks out over the falsely colored landscape. The following sol, Opportunity took pictures of Morris Hill, as the team reflected on their colleague, Rich Morris, lost last year. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell"Radio science is going gangbusters," said Arvidson of the rover's science achievements for the month.

The longest-awaited experiment in the mission, the radio science or radio Doppler study is tracking Mars' orbit to deduce more about the planet's core. Since this research requires the robot to be stationary and rovers are designed to rove, the MER model robot was never really designed to do this kind of research. But physicist, technologist, and MER science team member, Bill Folkner, of JPL, the principal investigator of this experiment, has submitted proposals again and again for landers to do just this kind of study among others, and he's still waiting for the stars to align, so to speak.

Folkner's latest proposal is part of a Mars mission designed specifically to further advance understanding of the formation and evolution of terrestrial planets. Called InSight, it would carry three experiments, of which Folkner's radio science would be one.

This proposed Mars mission however is competing against a comet hopper and a Titan lake lander to be the 2016 Discovery mission. The "winner" will be decided later this year.

Folkner has pressed on as he always has, piggybacking his research onto the other landed Mars missions, and he's made it worth every effort. His experiments to measure radio signals from the Mars Pathfinder lander confirmed, for the first time, that Mars has a dense core as expected. The radio Doppler tracking work with Opportunity will add to that knowledge, as well as data gained from the Viking landers in 1976.

Spirit was initially to have undertaken the radio science tracking after emerging from hibernation during the last Martian winter. But Spirit never phoned home. With Opportunity being in a planned long-term parked position for the first time in its eight years of roving, this, the mission's fifth Martian winter, provided Folkner with his first chance to gather radio data on the MER mission.

The goal set a couple of months ago was for Opportunity to get one hour of tracking data each week. It's a simple effort: the rover basically points its high gain antenna (HGA) as commanded and establishes a 2-way radio link with the Deep Space Network (DSN) radio telescopes.

Click to enlarge >

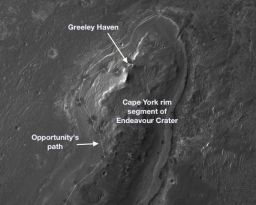

Click to enlarge >Greeley Haven on the map

Opportunity will spend its fifth Martian winter working at Greeley Haven. This site features an outcrop near the northern tip of the Cape York segment of the western rim of Endeavour Crater. It provides a north-facing slope of 15 degrees or more to help maintain energy output from the rover's solar array. It also presents geological targets of interest for investigating during months of limited mobility while the rover stays on the slope. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA"When the rover sends data directly to Earth on its HGA, if it's also locked to an uplink signal from the DSN, we can measure the roundtrip Doppler shifts," as Folkner explained it. "If the rover is stationary, then we can use the daily or weekly estimates of the longitude and spin radius (distance from Opportunity to the Mars spin axis) to determine the direction that the Mars spin axis points in inertial space. The spin axis direction changes slowly with time due to precession." For more, see discussion in the January 2012 issue of the MER Update.

Since using the HGA is somewhat power intensive, the rover has been generally tracking for 30 minutes in any given session, two to three times a week, and sometimes in March it managed four passes in a given week. "The data quality is good and we've been getting at least an hour a week, and it may be closer to an hour and half," Folkner reported during a recent interview.

After conducting simulations moving forward in time, Folkner found that Opportunity should have enough data by the end of March "to improve the precession rate estimate by a factor of 2. "A factor of 2 improvement is good," he assessed. "That means this has all been worthwhile."

Indeed. Improving the precession by a factor of 2 throws out about half of the Mars interior models considered reasonable just six months ago.

Folkner is, however, admittedly disappointed that he won't be able to get data on another constraint, such as the nutation signature. This signature is derived from tracking the subtle wobble in the planet's orbit. That would likely give scientists the data they need to confirm once and for all if Mars' core is liquid, as is generally believed.

Searching for a way to shave off time, Folkner did more simulations only to find that there is just no way getting around the reality that he would need Opportunity to stay parked for a half Martian year. That's nearly one Earth year, and the rover isn't going to stay put for that long. Never say never though. If the rovers have taught its crew and followers anything, it's that piece of ancient wisdom. The team has already asked Folkner to investigate the possibilities for next Martian winter, so his hopes of getting that other constraint haven't been completely quashed. It will just take longer.

Click to enlarge >

Click to enlarge >"Wheel drop" animated

This animation created from images that Opportunity took with its navigation camera was animated to show the event of March 2012 that has come to be known as the "wheel drop," a mysterious slight movement of the rover's left front wheel. The animation is by MER poet Stuart Atkinson, of UMSF.com and a frequent picture contributor to the MER Update . For more of Atkinson's images and musings: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / S. Atkinson

Other than the small gusts of winds that blew in at the top of the month, March was becoming so routine, so "lamb-like" by mid-month that it was threatening to become boring. And then a little excitement turned up.

Sometime between March 15th-20th, Opportunity 's left front wheel moved. It seemed to have happened right after the rover's instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm stalled while the rover was preparing for a Microscopic Imager ( MI ) picture assignment. The MER ops team began investigating both anomalies immediately even though the rover managed to complete both assignments that same sol.

Most curious was the wheel movement. "The left front wheel is a steering wheel and it is on one of the rockers, and the rocker dropped by less than a centimeter," reported Callas. "It's barely perceptible and it hasn't changed the position of the rover much."

"We don't know for sure when the wheel moved and we don't know why the wheel moved," added Nelson. "We know there is a difference between earlier images taken a few days before and images taken right after the stall, and later pictures for visodom.* The wheel appears to have slid downhill slightly." [*Visodom is short for visual odometry, a technique of analyzing pictures taken after a given time or event to look for subtle changes when compared with images taken before the event.]

There is nothing wrong with the wheel, far as anyone can tell. That is to say, nothing fell off. "If the wheel had disassembled, then you would have seen either a tilt or a drop in things we do not see," assured Nelson. "It just moved a little bit."

"Nothing that indicates any change in the health or the stability of the rover," Callas summed up.

Click to enlarge >

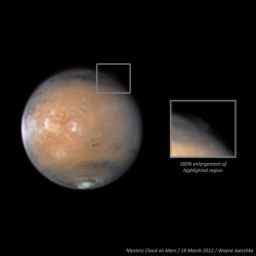

Click to enlarge >Mystery cloud on Mars

This is the image that shows an unusual cloud over the Martian plain Acidalia, taken by amateur astronomer Wayne Jaeschke and published in mid-March 2012. According to Bruce Cantor, of Malin Space Science Systems, the Mars missions' "weatherman," the cloud is most likely a condensate cloud made up mostly of water. For more, visit Jaeschke's website at: http://exosky.net/exosky/?p=1606Credit: Wayne Jaeschke

Nevertheless, the team continues its investigation. "It's enough that we know something changed and we want to know exactly what," said Nelson.

Since came the "wheel drop," as it's come to be known, occurred right around the same time that amateur astronomers announced their discovery of an unusual cloud on Mars, one wild and crazy notion that floated around was that a large meteorite hit the planet and caused seismic waves to move the rover. Never mind that Opportunity was on the other side of planet.

For the record, that notion is not true, despite its "entertainment value." [According Bruce Cantor at Malin Space Science Systems, who is also known as the weatherman for Mars, that cloud was likely was a condensate cloud or haze mostly H2O in composition.]

It appears Opportunity did suffer a loss in March, the integration use of the Mössbauer spectrometer . The instrument's signals are now so weak that it takes an extraordinarily long time to get any useable data.

"The instrument still works, but when we looked at the data we were getting we concluded that the source strength is so low that we probably wouldn't have accumulated a useful spectrum by the time we were ready to move the rover," Steve Squyres, the MER principal investigator of Cornell University said Saturday after returning from Washington DC, where he has been working with the National Advisory Committee on behalf of NASA. "That meant that it's better to use the IDD on other things."

The Mössbauer isn't completely out of commission. The instrument is still used to set up placement of other instrument's IDD instruments.

Rich Morris

John Richard "Rich" MorrisCredit: The Morris Family

As Opportunity settled into her winter location on Saddleback Ridge last December, the team renamed the winter site Greeley Haven, after team member Ron Greeley, who passed away unexpectedly last October. The team also lost Rich Morris that same month, and in March, it became official. The hill to the south of the rover is now Morris Hill, in remembrance of the JPL engineer, who died just a month shy of his 38th birthday.

"Once we got in place with the winter campaign, we wanted to name features after Ron and Rich," said Arvidson. "What formerly was known as Saddleback Ridge where we're currently located became Greeley Winter Haven, and the outcrop and hill immediately to our south, which is a likely target for exploration after we leave Greeley, is named Morris Hill, for Rich Morris.

The team chose this hill, this area to name in remembrance of Morris, because," said Squyres, "it's a beautiful feature that we can see very well from our winter haven."

Now as March turns to April, Opportunity is no doubt counting the weeks to roving. Sitting now in a haven named Greeley with a view to Morris Hill, the rover is completing her final assignments for the winter science campaign and all looks bright on the horizon. "We're looking forward to springtime," said Callas.

Opportunity from Meridiani Planum

The gusts of wind that first appeared in the last few days of February continued to whirl and whisk around Endeavour Crater into March, and Opportunity 's parked position on the north end of Cape York on the rim put her in the right place at the right time to reap the Martian reward.

Click to enlarge >

Click to enlarge >Simulation of Opportunity at Greeley Haven

Michael Howard, the creator of the heralded Midnight Mars Browser software, put together this simulated image of Opportunity . It shows the rover in her (approximate) winter parked position at Greeley Haven, which is located on the northern end of Cape York, along the rim of Endeavour Crater. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / M. HowardAs March roared in, the rover's power levels rose to 305 watt-hours, a little less than 1/3rd full power, with the atmospheric opacity over Meridiani Planum registering a Tau of 0.557, and the rover's solar array dust factor maintaining around 0.487.

"We had a little cleaning event on Sol 2827 (February 26, 2012) one day, and a little the next," said Nelson. "It now appears that the wind apparently was blowing enough to clear some dust for several days running."

Winter projections indicated that Opportunity 's power would likely drop to around 240 watt hours in March, but the Martian winds changed that. "We were expecting it to get down perhaps as low as 240 during the worst of the winter," said Nelson, "but it never got much below around 270 watt-hours. And that is just fine with us."

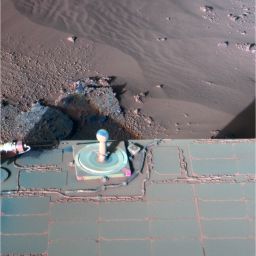

Click to enlarge >

Click to enlarge >Mars . . . Two Worlds

Opportunity took this picture with her panoramic camera on March 9, 2012. The Pancam team rendered it here in false color so scientists can better distinguish the various elements and textures in the terrain. The recent cleaning events caused by gusts of wind dusting the rover's solar arrays seemed to make a visible as well as measurable difference. You can actually see the word 'Mars' on the MarsDial, as well as 'Two Worlds,' from the motto Two Worlds, One Sun . The idea of using the calibration target as a Martian sundial was the brainstorm of Planetary Society Executive Director Bill Nye the Science Guy, then a Planetary Society board member. After all these sols, all these years, the MarsDial is still serving the mission as calibration targets for the high-resolution Pancams.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell

Opportunity used that newfound energy to step-up the radio Doppler tracking passes. During the first week of the month, the rover pointed her high gain antenna every other Martian day – on Sols 2882, 2883, 2885 and 2886 (March 2, 4, 6 and 7, 2012) – to support the ongoing geodynamic study of the Red Planet.

The robot field geologist also worked on the in-situ or contact science investigations of the bedrock target, Amboy, including taking series of MI pictures on Sol 2882 (March 2, 2012), to be used in the oversize, long mosaic.

This mosaic, as Arvidson tells it, is being done in strips, with the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer ( APXS) observations being taken in the center in the center between the two MI strips. "In the end, we'll have this long 2 x n MI mosaic, and going down the middle we'll have the APXS measurement along an array," he explained.

Here, there and between this and that, Opportunity continued placing the Mössbauer spectrometer on Amboy for long integrations, as well as took more 13-filter pictures with her Panoramic Camera ( Pancam ), homing in on the foreground. This close-up of the area right before her will be an added enhancement of the Greeley Pan. In addition, and as always, the rover snapped various color photographs of the rusty red surroundings throughout the month.

As the second week of the month got underway, Opportunity kept at the winter science campaign, tracking radio Doppler on Sols 2890 and 2893 (March 11 and 14, 2012); and taking MI pictures on Sol 2887 and 2889 (March 8 and 10, 2012), and placing the Mössbauer spectrometer r down on the surface target Amboy as often as possible.

On Sol 2888 (March 9, 2012), the rover took full color pictures of Morris Hill. It was, intentional or not, meaningful. The period of minimum solar insolation – the Martian day of least sunshine – passed the next sol.

Three sols later Sol 2892 (March 13, 2012), Opportunity used her Pancam to take a low-light, late afternoon photograph and managed to sneak in an atmospheric argon measurement with the APXS .

Click to enlarge >

Click to enlarge >2001 Mars Odyssey

Artist's conception of the 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft in orbit around Mars. This orbiter named for Sir Arthur C. Clarke's 2001: A Space Odyssey , has been one of the unsung heroes of Mars exploration, but this workhorse spacecraft continues to play a vital role as the primary communication conduit for MER .Credit: NASA / JPL

Opportunity headed into the third week of March with plenty of power to conduct three more radio Doppler passes, spend quality on the MI mosaic assignment, and send data home every sol via UHF link to Mars Odyssey , something the team hadn't planned on being able to do.

By this point, Bill Folkner knew that if all went as planned then he would have the data he needed by the end of March to improve the current estimated precession rate of Mars. After conducting simulations and crunching the numbers, he estimated that he would be able to improve the rate by a factor of two, basically throwing out half of the Mars models currently considered. As good as that was, he also discovered that was about as good as it was going to get.

"In 90 days, the precession rate uncertainty comes down a factor of 2, and then for the next 9 months of the year the precession rate doesn't improve very much . . . That's because with 90 days of data we're getting the spin axis direction in 2012 to some accuracy and we’re comparing it to Mars Pathfinder spin axis direction, and I'm not sure if the Mars Pathfinder or Viking spin axis direction is more accurate because I just use them both. So if I get the spin axis direction after 90 days I get a precession rate. And if I take another 90 days of spin axis direction data, then I determine the spin axis direction of 2012 better, but I don't know it any better in 2007," he said.

"Even if I knew 2012's spin axis direction perfectly – because I didn't know perfectly in 1997 – I cannot get a perfect precession rate," Folkner continued. "So what happens is if we will take data going forward into April and May, we're improving the spin axis direction in 2012 but not 1997, so the precession rate is not improving."

Folkner had been hoping to improve another constraint, to better understand the composition and state of the core. "I've known from previous simulations it would take half a Martian year if I just had one lander to get the nutation signature," he said. "I was hoping that with the 90 days of data from Pathfinder, if we had MER Opportunity data appropriately phased in the nutation cycle, then we could combine them and get something quicker than 12 months."

Click to enlarge >

Click to enlarge >A rover's eye view of the Pathfinder lander

This image of Pathfinder – renamed the Carl Sagan Memorial Station – was captured by Sojourner's left front camera on its Sol 33. The Pathfinder camera (on the lattice mast) is looking at the rover. The airbags form a billowy mass around the lander, and the meteorology mast sticks up to the right. The lowermost rock is Ender, with Hassock behind it and Yogi on the other side of the lander. Credit: NASA / JPLBut the analysis last month revealed that doesn't happen. "For some reason, the Pathfinder data and the current MER data are not phased differently enough in nutation to complement each other and I don't know why – I haven't figured that out yet," he said. "But when I put them all together I find that it takes a half a Martian year of Opportunity data to get the nutation signature, which is like we didn't have Pathfinder at all."

So that's the end of that constraint. For now anyway.

Okay, there is the remotest of remote possibilities the nutation signature is "a little non-linear," confirmed Folkner, so when they really start to look at the data, there is a far out 1% chance they could see a nutation signature. "It's a 99% chance we won't," he underscored.

There may be another chance down the road, next Martian winter, and the team is looking ahead optimistically. "They've asked me to look at next Martian winter and whether another 90 days in that timeframe would be properly phased," said Folkner, who is happy to oblige.

Back on Mars, Opportunity conducted Radio Doppler tracking passes on Sols 2895, 2897 and 2899 (March 16, 18 and 20, 2012), took more MI pictures on Sols 2894 and 2899 (March 15 and 20, 2012), and placed the APXS was placed on target Amboy3 on Sol 2894 for a multi-sol integration.

On March 20th, the rover's Sol 2899, Opportunity was preparing for the MI mosaic imaging when she experienced a safety stall in her IDD. The rover managed to finish the imaging successfully, and subsequently placed her Mössbauer spectrometer on the target Amboy as planned, but as per protocol the MER ops team launched investigations immediately, commanding the rover to begin diagnostic activities on Sol 2901 (March 22, 2012).

Click to enlarge >

Click to enlarge >MER body parts

The Mars Exploration Rovers are robot field geologists that were designed with parts to substitute for the organs all living creatures would need to stay "alive" and able to explore, as well as some super-human powers. Spirit and Opportunity , for example, each have a body that protects its "vital organs;" brains to process information; temperature controls, including internal heaters, a layer of insulation, and more; a "neck and head" formed from a mast for the panoramic cameras for a human-scale view; eyes and other "senses," such as cameras and instruments that give the rovers information about their environment; an arm to extend its reach; wheels and "legs," necessary parts for mobility; and energy sources in the form of batteries and solar panels; and antennas for "speaking" and "listening." Credit: NASA / JPL-CaltechThere are two types of stall that could have occurred on Opportunity in this scenario: a current stall and an encoder stall. "A current stall happens when you start loading up the motor," explained Nelson. "In other words if I tried to push the Mössbauer into the terrain, once I make contact, the harder I push, the more current that motor draws, until eventually the current reaches a high enough value that the motor trips what is known as a motor stall. That did not happen," he said.

The other stall occurs on the encoder. In Opportunity 's case, the encoder stopped moving, Nelson pointed out. "That's indicative of reaching the extension limit that is allowed. Well, maybe we shoved this thing toward the terrain and we reached the extension limit we had programmed into the arm, so it went as far as we allowed it to go and simply never contacted the surface, and it generated a stall. We had moved to a new location to do this new MI stack. The fact that it didn't generate a current stall and the contact switches did not trip does suggest that we drove it into a shallow area. That is in fact our leading hypothesis, although not the only one, for what's gone on here," he said.

In the images that Opportunity sent home after the IDD stall however, something more surprising and unexpected, even a little disconcerting was seen. Sometime between Sol 2894 and Sol 2899 (March 15 and 20, 2012), the rover's left front wheel dropped or slipped or settled just a bit. It was pretty clear in the first pictures taken after the stall with the front hazard-avoidance camera – the left-front wheel dropped roughly 1 centimeter (half an inch).

"There was a very small change in the left front wheel, and it is viewable in the imagery, but it looks like the rover itself hasn't moved," said Callas. "We are taking it cautiously, but there may not be much story here. The rover is safe, healthy and stable, and there is no indication of risk to Opportunity."

Still, the small drop in the left-front wheel is curious. "We don't know when it happened or whether it has any relationship to the IDD and the joint stall," said Nelson. "The thing we do know is that we were attempting to do a MI stack, and the first thing we do for that is to flip around and use the Mössbauer as a surface sensor. We have the rover do what we call a Mössbauer touch. The Mössbauer touch should push the instrument into the terrain until the contact plate trips what are called the microswitches called contact sensors, but instead it stalled.

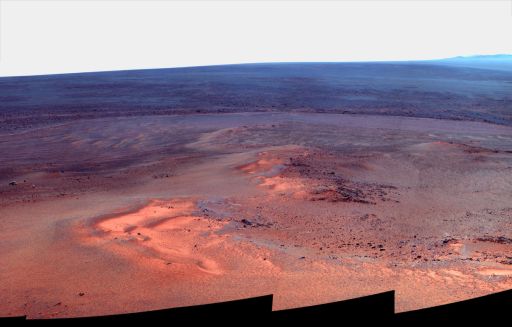

Click to enlarge >

Click to enlarge >Greeley in Winter

This mosaic of images taken in mid-January 2012 shows the windswept vista northward (left) to northeastward (right) from the location where Opportunity is spending its fifth Martian winter, an outcrop informally named Greeley Haven. The rover used her Pancam to take the component images as part of full-circle view being assembled from Greeley Haven. The view includes sand ripples and other wind-sculpted features in the foreground and mid-field. The northern edge of the Cape York segment of the rim of Endeavour Crater forms an arc across the upper half of the scene. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASUAmong the hypotheses:

Opportunity's left front wheel was on a small rock that crumbled:

"Was there a pebble under the wheel that we just slipped off of after several months of sitting?" mused Callas. "Maybe we're working the surface and a little rock finally fractured and collapsed. It may have relieved tension in the mobility system without actually causing the body of the rover to move."

The continued movement of the arm caused a slight change in wheel loading:

"The arm is only about 5 to 6 pounds and the rover is 380 pounds, so even though the IDD extends out a little distance, it's not a lot of weight and it only makes subtle changes if any in the rover [status]," said Nelson. "But after doing this a number of times, it could conceivably have caused the surface to give way or compress a bit."

The rover's left front wheel simply settled:

"The vehicle is tilted at 15 degrees and it's on an irregular surface, so the left front wheel probably just settled a little bit," suggested Arvidson. "Gravity pulls on all of us. Perhaps that led to just a very slight change in the orientation and position of the vehicle, barely measurable at all."

Click to enlarge >

Click to enlarge >A sunset postcard from Mars

Near sunset on her Sol 2847 (Jan. 27, 2012), Opportunity gazed backward to the east-southeast and the distant line of peaks that mark the far rim of Endeavour crater. The setting Sun throws long shadows from the low-standing ridge that the rover, is standing on. In fact, Opportunity's own shadow is visible, a blurry speck standing on the ridge's shadow. Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / color mosaic © Don DavisThis past week, Opportunity took more pictures with its cameras , so the team could do ground-based visual odometry or visodom to better understand the nature and extent of the rover's movement, and the event now known as the "wheel drop."

"Visodom is a technique wherein we take stereo images before-and-after to see if there is a change in the rover position or in targets being studied," reminded Arvidson.

"We've got older images and with new images, we take the difference between them and from that deduce how the vehicle moved," added Nelson. "Since we have cameras attached to the rover body and not the wheel, these images can tell us whether the vehicle itself has moved or just the wheel."

The wheel was not commanded to turn and it did not turn, it merely shifted on the terrain, Nelson clarified.

For the visodom imaging, Opportunity took a series of pictures on Sols 2901, 2904 and 2906 (March 22, 25 and 27, 2012), of its position and detail imaging of the Mössbauer spectrometer on the end of the IDD, and carried out a series of diagnostic IDD/arm motions. The IDD moved without any problems. Motor currents and actuator motion were all nominal.

"The wheel for sure moved," said Arvidson. "You can see the change. But it led to a minor change if at all in the vehicle tilt and or location."

After careful review of the left-front wheel in the visodom pictures the team now believes that the wheel actually probably moved more than one time, "although these are very small motions, a few millimeters," noted Nelson. "Both motions are very small and may be a relaxation of stress in the mobility system. The overall vehicle also moved although it was very tiny. No other wheel has shown any indication of motion," he said.

The detailed images of the Mössbauer spectrometer , meanwhile, showed no evidence of any off-nominal contact with the ground. The team continues to assess the left-front wheel stability.

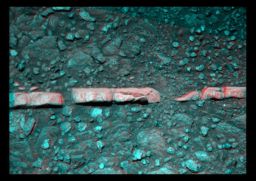

Click to enlarge >

Click to enlarge >Homestake up close and in 3D

Get your blue-red glasses and check out this close up of Homestake, rendered here in 3D. Opportunity discovered this "vein" to be gypsum in December 2011. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / S. AtkinsonUpcoming plans call for Opportunity to reorient herself, performing a "quick fine attitude" to zero out uncertainties in her position. "This is done by imaging the Sun and comparing its expected versus actual positions," Nelson reminded. "We are also taking more imaging to better quantify the motions and to detect further motion, if any," he added. "Since motions to date are near the limit of what we can measure, we want to use multiple methods and take multiple samples to improve our estimates."

Once this is done, the engineers are planning on having the rover wiggle her left front wheel, which should relax any further stress on that wheel. "Separately, we are now imaging at least twice a day to detect further motion and to try to bound when it happens to it can be correlated to other activities (if such a correlation exists)," said Nelson.

Neither the cold of winter nor the annoyance of stalls or "wheel drops", nothing is slowing down Opportunity 's pace. The rover conducted radio Doppler passes on Sols 2903 and 2904 (March 24 and 25, 2012), then with her IDD/arm in its partial stow position, pointed her APXS skyward and took some atmospheric argon measurements on Sols 2904 and 2905 (March 25 and 26, 2012), and at some point most every sol, she managed to find the time to take more Pancam images, either close-ups of the foreground, or vista landscapes of the surrounding area.

With energy levels consistently hovering around 300 watt-hours, Opportunity has been able to send data home almost every sol. "For the better part of a month, we have been doing UHF passes every day," reported Nelson. "Then we've been scheduling on average three radio science passes a week in addition, because we've got the energy to do that."

Onboard data is something the engineers need to constantly manage. "We're basically sitting there with about 500 megabits worth of unsent data and about 600 megabits worth of available space, which means there's a small amount of sent data that's still on board to make up our total of 1024 megabits," explained Nelson.

Click to enlarge >

Click to enlarge >Triple crunch

After checking out the vein dubbed Homestake in December 2011, Opportunity was instructed to perform a "triple crunch," as Deputy PI Ray Arvidson called it. "We backed over the vein, drove forward, then turned in place and left. We crunched it," he said. It turned out to be filled with "sparkly bits." Stuart Atkinson processed the image here in "retina burning false color." What a mess, but what a mix of stuff. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / S. AtkinsonIt's typical for Opportunity to keep a certain amount of backlog on the rover, because if unsent data gets too long, the team runs the risk of "having the well run dry," as Nelson puts it. And when the well runs dry, then the rover just sends fill data, which means they're not getting really efficient use of the radio link. "We like to have enough backlog so that never happens," Nelson noted.

"On the other hand, we can't let it build up too high, because then there's no room for new data," Nelson continued. "Right now, we're in a pretty good spot. We've got plenty of room for the next little while – 600 megabits are available to us. We seldom take more than 100 megabits, maybe as much as 150 in each plan and we clean out all the stuff that we have previously sent periodically, so data management is not a concern."

Radio science, for now, remains the "number one priority," said Arvidson. "We will continue the radio Doppler tracking passes through the end of April."

The value in taking data for another month or so is in the fact that it allows Folkner to trim 30 months off beginning or end and see if he gets the same answer. "In other words, it will allow me to test for systematic errors in the data processing," he said. "There's a little bit of software work we're going to do in the next few weeks so we can start looking at real numbers, and get an actual estimate," he added. "Hopefully a month from now we should be grinding numbers out and trying to see if we believe the answers or not. By the end of April we should have a preliminary precession rate."

As March turns to April, Opportunity is producing more than 305 watt-hours of power, plenty of energy to put in good sols' worth of work. "Once we're finished with radio science in April, we want to continue the MI and APXS campaign and all that's being debated right now," said Arvidson.

The APXS argon measurements aside, Opportunity has been more or less resting her arm while the crew continues to try and figure out the cause for the stall and whether or not it had anything to do with the "wheel drop." But the rover will likely be back to work soon.

Click to enlarge >

Click to enlarge >Opportunity on Endeavour's rim

This HiRISE image, taken by the camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter on September 10, 2011, shows Opportunity sitting atop some light-toned outcrops on the rim of Endeavour Crater, near a smaller crater dubbed Odyssey. The rover traveled nearly three years to reach this crater, because it contains rocks even more ancient than the rocks of Meridiani Planum, which the rover had been exploring since January 2004,offering potential discoveries that may teach us something about an even more ancient era in Martian history. Credit: NASA / JPL / UAThe best guess is the rover will be cleared to use her arm again without restriction late next week or early the week following, according to Nelson.

"It depends on both direct activities such as our QFA, imaging, wheel wiggle, and updating of terrain meshes, and on indirect activities, like radio science, which compete for the available power and limit how fast the direct activities can happen," he said.

The rover is also resting her Mössbauer . Whether or not that instrument will be used to record any more compositional data from integrations is looking doubtful. Although the instrument still actually works, to get useful data it now requires the kind of time Opportunity doesn't have to give. So the rover will focus on using other instruments on her IDD.

"A few weeks ago we experienced a drive electronics problem that is still being investigated," recollected Nelson. "We're in sort of a race because the Cobalt-57 source used to illuminate targets is into its 12th or 13th half-life, which means it's very, very weak. If the Mössbauer is out of service for too much longer, the source will decay into virtual unusability regardless of whether the electronics can be made to work or not. We're depending on the Germans – they built it and remain its official operators – to tell us what's wrong and the only word we hear so far is that the data are no longer showing peaks."

The drive electronics problem was mitigated by having the rover do Mössbauer integrations only when the temperature was -50 C or higher. "This wasn't great because the Mössbauer provides better data when the target is colder," Nelson said. "However while the Mössbauer does self-heat a bit, it has no heater, so we have to operate it at warmer ambient temperature, and on warmer targets."

Warmer targets translates into more thermal noise and less well-defined peaks in the energy spectra. Coupled with a weak source, it all adds up to very noisy data. Now something else has gone wrong. Stay tuned.

With Opportunity 's fifth Martian winter soon to be in the rear-view mirror, the team has already begun considering the plan ahead. "Once winter passes and energy levels rise, there are important things to do," said Arvidson. "We need to go back to the Bench, where we saw the gypsum vein Homestake and find a bigger one that we can grind into, remove any coating, and redo the measurements."

While Opportunity performed a triple crunch on Homestake, there was not time before winter set in for the rover to hang out and make any in situ measurements. And Homestake is too small to revisit for a grind. "The width is too small, so it doesn't fill the field of view of the APXS ," Arvidson explained. "Once we start moving, we'll pop out to the Bench either on the east side or the west side, and find a thicker wider vein, grind that, and look at it before and after with the APXS.

Click to enlarge >

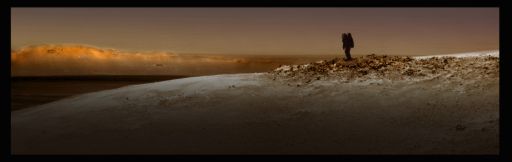

Click to enlarge >The Guide

"Somesol a so-tired tour guideWill lead vacationing families

To this place one final time,

Their faces beaming behind gold-plated visors -

Some sun-starved and pale,

Betraying their Martian birth ..."

This artistic image, created by Stuart Atkinson from some of Opportunity 's Pancam bounty with a little special effects accompanies Atkinson's latest astropoem, The Guide , which he introduced and which is available on his Road to Endeavour blog . The scene here simulates a human visitor or guide looking out over what the rover Opportunity is currently looking out, with a little Earthling flourish. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / S. Atkinson

There is also talk of Opportunity roving up to Morris Hill. That adventure is still "undecided" right now, according to Squyres. "It's pretty steep, so we still have to evaluate whether we can actually drive onto it, or just look at it from a safe distance," he said.

For now, Opportunity 's odometer remains unchanged at 21.35 miles (34,361.37 meters). "We'll move when we're ready to move," said Squyres. "June is a reasonable guess, but that could change depending on tau, dust factor, etc. General plan is to head south, performing more investigations on Cape York and then heading toward Cape Tribulation."

All in all, the best news of all in March came naturally, as the winds blew in at the top of the month and winter solstice passed this week. "We'll have continued low temperatures before it starts to get warmer," said Nelson. "But it looks like we're past the most difficult part of the winter," finished Callas. "The winter risks to the rover are almost behind us now."

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth