A.J.S. Rayl • Dec 31, 2011

Mars Exploration Rovers Update:Opportunity Climbs to Greeley Haven for Winter, and We Look Back at 2011

As New Year’s Eve moved from time zone to time zone across planet Earth, the Mars Exploration Rover (MER) team looked to 2012 and wrapping its eighth Earth year of exploring, while up on the Red Planet Opportunity settled into the “saddle” at Greeley Haven preparing for the onslaught of its fifth Martian winter.

“We’re in position for the winter,” announced Steve Squyres, principal investigator for rover science, during an interview New Year’s Eve.

Opportunity is currently parked on a 15-degree slope on bedrock called Saddleback, a part of Shoemaker Ridge at the northern end of Cape York, the "port" that forms part of the rim of Endeavour Crater. Here, the rover can angle its solar arrays to the north toward the Sun, so it can take in as much sunlight as possible through the bleakest months of the Martian winter.

Winter solstice in the southern hemisphere of Mars, where Opportunity is located, passes on March 30, and the point in the orbit [of Mars] where it is the farthest distance from the Sun, known as aphelion, is the end of February. "We're coming up within a couple of months to very low energy conditions,” noted Ray Arvidson, the MER deputy principal investigator. “We just want to get settled.”

The MER team made the decision that the rover would park on Saddleback and winter at Greeley Haven about a week and a half ago. “It wasn’t a crisp decision," said Arvidson, of Washington University St. Louis. "It was a realization."

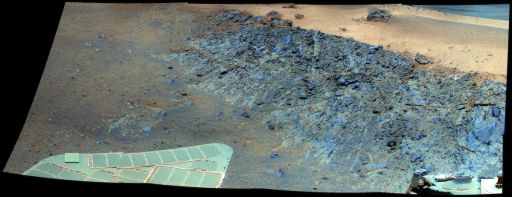

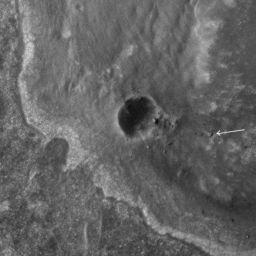

Greeley Haven

Greeley HavenPhotographed in false color to emphasize differences in composition, the rocks of Greeley Haven stand out in blue-gray tints. In the background at right lies a tan patch of sand. While Opportunity is parked here for several months, scientists plan to direct the rover to investigate interesting targets on the outcrop using the instruments on its arm.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell/Arizona State University

"We try to pack as much science in as we can before we stop for the winter," said Bill Nelson, chief of the rover engineering team at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where the rovers were "born" and are being managed. "In the process, there is always the tension between how much margin do we need to get settled in for winter versus how much science can we do before we have to shut down for the winter."

The team had been contemplating two winter site possibilities at Cape York where Opportunity could hunker down for the next several months: a slope called Turkey Haven on the southern part of the Cape York “port”, and the northern site that is Greeley Haven. The rover needed to be on at least a 10-to-12 degree slope to survive and work through the winter according to projections, so once Opportunity achieved a 15-degree angle and the science team agreed that Saddleback offered a good target where the rover could place its Mössbauer spectrometer down for many hours at a time, the decision was realized.

Because of its current position, Opportunity may not move "until after winter,” said John Callas, MER project manager, of JPL, and. “Of course, if we get a dust-cleaning event and power levels go up,” Squyres cautioned,” then all bets are off.”

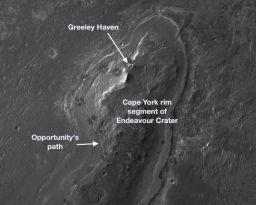

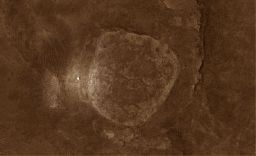

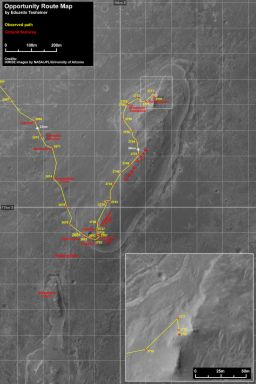

Greeley Haven on the map

Greeley Haven on the mapOpportunity will spend its fifth Martian winter working at Greeley Haven. This site features an outcrop near the northern tip of the Cape York segment of the western rim of Endeavour Crater. It provides a north-facing slope of 15 degrees or more to help maintain energy output from the rover's solar array. It also presents geological targets of interest for investigating during months of limited mobility while the rover stays on the slope.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA

In any case, from the looks of things now, the rover will be able to work through the season, parked or not. At least the team is planning for that, and actually Opportunity’s winter science campaign is a trio of experiments that benefit from, or can only be conducted with the rover in a solitary position:

Before Opportunity could launch her winter science campaign however, the rover had to prove all its systems were ‘go,’ after giving the team a bit of a scare. On December 17, the rover’s Sol 2808, Opportunity tripped a current limit on its right front wheel while trying to position itself and stopped the drive.

“This is the wheel that has always showed the elevated currents and we were concerned,” said Callas. Diagnostic tests showed that the wheel and its actuator or motor looked fine. The rover is on a steep slope, positioned such that its right front wheel has to push a lot harder, and so we think it was just naturally a result of the terrain and the geometry of the rover,” he explained.

For the first time during the MER mission, Opportunity’s handlers utilized the Adams Rover Terramechanics and Mobility Interaction Simulator, known better by its acronym, ARTEMIS, to model a "live" event, the rover's drive termination, in a computer on Earth. This multi-element, dynamic, 3D computer simulation modeling tool has been under development for a couple of years at Washington University, under the direction of Ray Arvidson, and previously reported on in the MER Update last March.

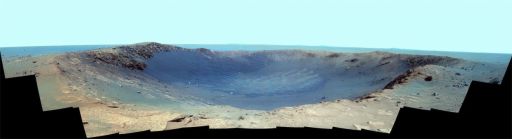

Approaching Greeley Haven

Approaching Greeley HavenOpportunity used its navigation camera to capture this view of a northward-facing outcrop, "Greeley Haven," where the rover will work during its fifth Martian winter. The rover team chose this designation as a tribute to the influential planetary geologist Ronald Greeley (1939-2011), who was a member of the MER science team and many other interplanetary missions. The rover took this southward-looking image during its Sol 2790(Nov. 29, 2011), as it approached the outcrop.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

ARTEMIS “predicted this behavior,” said Callas. “We gave it the geometry of the situation, the position of the rover, and it then calculated what it would expect to find for torque on the wheels." Indeed, it showed that Opportunity's right front wheel would draw higher current than the others. “It was a nice validation," he said.

Good to go, Opportunity got to work on Mars even as Earthlings reveled during the New Earth Year’s Eve weekend, initiating the winter science campaign by placing the Mössbauer down on the target called Amboy on Saddleback, and taking the first of what will be a couple thousand images for the Greeley Panorama. The rover has been commanded to turn on the radio - science experiment that is on New Year’s Day.

"From the science point of view the big return is radio science," said Arvidson. "There's a mystery about how big Mars' core is and its density; therefore, what it's made of, and there are a number of permissible models."

“This work will produce data that could help us narrow down our uncertainty about the size and density of the core,” added Bruce Banerdt, MER project scientist, who is involved in the planning of this experiment led by JPL’s Bill Folkner.

For this experiment, Opportunity will use its transmitter and high gain antenna to track the dynamics of Mars’ spin axis over a number of months, collecting data that will allow planetary dynamicists “to back-calculate the planet’s interior density as a function of depth that is needed to produce the spin axis dynamics,” as Arvidson explained it.

This is not to suggest that the investigation of Saddleback and the Greeley Panorama are in any way less significant. “We’re going to be doing all three experiments in parallel over the next couple of months,” said Squyres.

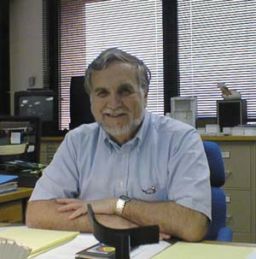

Dr. Ronald Greeley 1939-2011

Dr. Ronald Greeley 1939-2011Dr. Ronald Greeley was involved in lunar and planetary studies for more than four decades. His latest research focused on understanding planetary surface processes and geological histories, utilizing a combination of spacecraft data analysis, laboratory experiments, and geological field studies on Earth of features analogous to those observed on the planets. He was a mentor and friend to so many planetary scientists.Credit: Arizona State University

Greeley Haven was named for MER science team member Ron Greeley, of Arizona State University (ASU). Highly respected and honored, the much loved planetary scientist passed away suddenly at home in Tempe, Arizona last October. “We’ve decided to name our current location in honor of him, and so the panorama will of course be the Greeley Panorama," Squyres said via telephone from his base of rover operations at Cornell University. "And the spot we’ve chosen for our Mössbauer integration we’ve named after the Amboy Crater in the Mojave Desert, one of Ron's favorite field sites. He took generations of students there,” remembered Squyres.

It is a bittersweet end to a productive, some might say mission-changing year for Opportunity. The expedition literally began anew in August when the rover pulled into Spirit Point and onto the Noachian crust at the edge of the rim of Endeavour Crater after a near-three year journey from Victoria Crater. "Then there's all the spectacular science we’ve found since getting there – the Shoemaker Formation and all the wonderful impact related geology of that, and Homestake, the gypsum vein running through the Bench that surrounds Cape York, probably the single most solid piece of evidence of Martian water that this rover has discovered," Squyres said. "It’s been a really good year,” he added, pausing. "I think you have to rank it was one of Opportunity’s best years.”

As 2011 comes to a close, Opportunity is ready for its fifth Martian winter. The skies overhead are pretty hazy – the rover reported a Tau (measurement of opacity) ranging from 0.645 to 0.755 in December. With a solar array dust factor bouncing within a small range of 0.469 and 0.487, it's clear that the rover's solar arrays did not experience the benefit of a dust-clearing gust of wind during the last month, but the dust accumulation didn't get much worse either.

Now, with 34,361.37 meters (34.36 km, 21.35 miles) on the odometer, and power levels fluctuating around 300 watt-hours (about one-third full power for this model rover), Opportunity will greet the New Earth Year with its mast held high.

In other MER news, NASA presented its 2011 Software of the Year award to JPL and the team that created the Autonomous Exploration for Gathering Increased Science (AEGIS) software. Operational on Opportunity since December 2009, AEGIS was created to make the targeting process involving scientists on the ground more efficient by enabling the rover to autonomously take pictures of interesting rocks and formations.

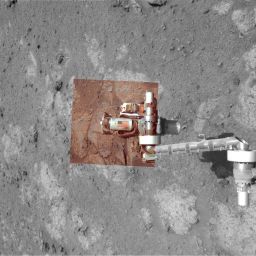

A rock for the AEGIS

A rock for the AEGISOpportunity selected this rock as a target and took this image autonomously using the AEGIS software, which was recently honored as NASA's Software of the Year for 2011. On the left is shown the selected rock target, captured in three color filters with the Pancam. On the right is the original target selection in a wide-angle image taken by the rover's navigation camera.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

The picture taking process traditionally requires the rover to stay in place for a day or more, waiting while data is transmitted to Earth, waiting for scientists review the data and select targets, and then for engineers to uplink commands. With AEGIS, Opportunity can analyze images onboard in real Mars time, detect, and prioritize science targets in those images (based on pre-specified criteria set by the mission science team), and autonomously obtain novel, high-quality science data of the selected targets within 45 minutes, without requiring communication from Earth.

Developed as part of a larger autonomous science framework called OASIS (short for Onboard Autonomous Science Investigation System), the AEGIS system takes advantage of the OASIS ability to detect and characterize interesting terrain features in rover images. AEGIS is the second software developed for MER to earn NASA's software of the year award. In 2004, MER's Science Activity Planner, the intuitive interface for the rovers that features cutting-edge visualization, as well as sophisticated planning and simulation capabilities, was deemed that year’s "best of the best."

Looking Back at MER: 2011

January

As 2011 rang in at Meridiani Planum, Opportunity was in the midst of her exploration of the 80-90 meter (262-295 foot) diameter Santa Maria Crater on Mars, the last major geologic feature on her long journey to Endeavour Crater. While fireworks exploded around the Earth, the rover was shooting rich pictures with both her navigation camera (Navcam) and panoramic camera (Pancam) from several points around the rim of the youngest, freshest crater she’d ever seen.

Santa Maria in false color

Santa Maria in false colorOpportunity spent its seventh anniversary of its landing on Mars investigating a crater called Santa Maria, which has a diameter about the length of a football field. This scene looks eastward across the crater. Portions of the rim of a much larger crater, Endurance, appear on the horizon. The panorama spans 125 compass degrees, from north-northwest on the left to south-southwest on the right. It has been assembled from multiple frames taken by the panoramic camera (Pancam) on Opportunity during the 2,453rd and 2,454th Martian days, or sols, of the rover's work on Mars (Dec. 18 and 19, 2010). The view is presented in false color to emphasize differences among materials in the rocks and the soils. It combines images taken through three different Pancam filters admitting light with wavelengths centered at 753 nanometers (near infrared), 535 nanometers (green) and 432 nanometers (violet). Seams have been eliminated from the sky portion of the mosaic to better simulate the vista a person standing on Mars would see.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell University

Over on the other side of the planet, at Gusev Crater, Spirit sat silently, parked on the west side of Home Plate, where she’d been since April 2009 when her left wheels slipped along the edge of a shallow, hidden sand-filled crater, trapping her. Spirit tried to rove out, but her left wheels only dug in deeper and in May 2009 she was ordered to stop. After more than six months of effort and work with a replicate rover on the ground, the campaign to Free Spirit began on Mars in November 2009.

During the extrication attempts, Spirit’s rear right wheel stopped working, further handicapping it as a four-wheeled rover. Even so, the rover began making progress when the team changed the drive strategy in January 2010. But time was not on Spirit's side. Winter came on hard and cold and the rover, ostensibly, tripped a low power fault, and went into hibernation sometime after her last communiqué on March 22, 2010. The Radio Science Team at JPL had been listening and sending radio "nudges" ever since. In January 2011, they stepped up the effort using every available time and slot at the DSN and with the orbiters.

February

Near the end of January Spirit and Opportunity each headed into solar conjunction. This approximate two-week period when the Sun is directly in between the Earth and Mars occurs every 26 months and disrupts communications between the two planets. As a result, Earth-to-Mars communication moratoriums are imposed for all spacecraft at Mars.

Simulation of Spirit's predicament

Simulation of Spirit's predicamentThis artistic image -- in which Astro0 has placed a two-dimensional MER into a scene created by pictures taken by the real rover -- illustrates Spirit's predicament at the location in Gusev Crater known as Troy. Although the angles are admittedly a little off and the disturbed soil isn't quite right, it offers the general reader a glimpse into where the rover got stuck, and remains now a part Mars.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / ©Astro0 2009

By mid-February, the moratorium was lifted. Opportunity was parked along the southeast rim of Santa Maria in an area the team nicknamed Yuma, where the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) detected evidence for hydrated sulfate minerals, checking out a target called Luis de Torres. With the solar conjunction over, Opportunity drove on, counter-clockwise around Santa Maria Crater, to Ruiz Garcia, a slate blue colored boulder.

On the other side of the planet, at Gusev Crater, Spirit remained silent.

March

In March, the radio science team at JPL and the DSN upped the ante in an intensive strategy to establish contact with Spirit, systematically sending electronic "nudges" over a wider range of frequencies, at more local solar times on Mars to try and get even just a "beep" out of the rover.

“We are doing everything we can do to shake this spacecraft every way we can think of to try and get it to respond to us," reported Bill Nelson, chief of the MER engineering team, at JPL. "There are so many things that will keep us from ever hearing from this vehicle again – that lack of signal is not diagnostic of any one thing."

The middle of the month would present the period of maximum solar insolation at Mars, the time of the Martian year between spring and summer where the Sun is at its highest in the sky and the rovers can produce the most energy. It seemed like now or never. The month marched on. Ultimately, lack of signal could mean one thing for certain.

"They're not immortal," reminded Squyres. “We've known that all along.”

Endeavour hills close-up

Endeavour hills close-upMER aficionado Stuart Atkinson, the Poet Dude at UnmannedSpaceflight.com, offered up this close-up of the hills along the rim of Endeavour Crater. "Don't read too much into the detail visible on those distant slopes, there's quite a bit of noise in that image," he noted. "Just enjoy the view." How can we not?Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell University / S. Atkinson

"We are right now at the time of highest probability of hearing from the rover," Callas noted then. "Everyone's a grown-up here, and we are all recognizing the realities of the situation." A ‘death’ announcement could come as early as late April, he ventured.

At the same time, Opportunity was finishing her science assignments at Santa Maria, and getting back on the Meridiani highway to the big crater, then just under 6 kilometers (about 3.73 miles) to the south.

"We are on the road again to Endeavour," Squyres announced as March came to a close.

The MERmission had miles to go and it was going to cross those miles. That seemed to be the unspoken philosophy among team members. "The terrain ahead is just as flat as a pancake and we expect to be able to go full steam ahead from here on out," said Maxwell.

April

Full steam ahead might have seemed an overstatement – except it wasn't. Opportunity drove out of March and into April, pedal to the metal, veritably clicking off meters on her trek toward Endeavour Crater, and living up to her reputation as "Little Miss Perfect."

The rover crossed the 28-kilometer mark on April 19th, besting the Apollo 15 lunar rover’s established record of 27.76 kilometers. [Lunar rovers, better known as Moon buggies, were used on the last three Apollo missions and were driven by astronauts.]

Rove on, Opportunity

Rove on, OpportunityThis rendered image of Opportunity is produced with "Virtual Presence in Space" technology, developed at JPL. It combines a photorealistic model of the rover and a false-color mosaic taken by the rover on Sol 134 (June 9, 2004) with its panoramic camera while in Endurance Crater. We at The Planetary Society liked it for the symbolism it imparts of the robots that just wanna rove. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell Rover model by Dan Maas / synthetic image by Zareh Gorjian, Koji Kuramura, Mike Stetson and Eric M. De Jong

Just seven sols or Martian days after later, on April 26th, Opportunity logged the longest backward drive ever,152.18 meters. The only two remaining roving records for this rover to beat are: the Apollo 17 Moon buggy's record of 35.89 kilometers, and Lunokhod 2's record of 37 kilometers, the longest any robotic rover has driven on another celestial body. Considering that nearly 7.5 years after landing, she had just driven more than a half-mile in one month alone, bringing the gargantuan 22-kilometer (13.70 mile) diameter Endeavour Crater to within 5 kilometers (3 miles), those records seem within reach.

"Opportunity is demonstrating that she can sprint," added Callas. "This is far beyond anything we thought the rover could do during the prime mission." Summed up Arvidson: "To be here now with this rover, it is remarkable."

Soon, Opportunity would claim title to being the longest-lived robot on Mars.

As April gave way to May, the MER engineers still held out "a little hope," that Spirit would respond soon, said Nelson. "We have pretty well exhausted the seven primary strategies – and we're continuing down our list." Added Scott Maxwell, rover driver lead: "Given everything she has done for us, Spirit has certainly earned the right to have every possible chance."

The last of the potential dust-cleaning wind gusts could kick up as late as July, the end of the Martian summer, so there still was a chance Spirit could suddenly clear her presumed dust congestion and phone home. Hope was alive. But barely. It was competing now with reality. “That we haven't heard from Spirit by now says that something is seriously wrong," admitted Callas.

Spirit shines on at Troy

Spirit shines on at TroyIn this picture of Home Plate, taken by the HiRISE camera onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter in early 2010, you can see the stark white figure that is Spirit to the left (west) of the geologic formation in this image enhanced by rover poet Stuart Atkinson. "It's just a screengrab from the excellent HiRISE IAS Viewer," he said. "I added some colour, then highlighted the position of Spirit. If you look carefully you can actually see bright trailing leading to Spirit - this is the result of the (right front) broken wheel being dragged through the dirt, unearthing brighter material beneath." For more of Atkinson's work, check out his blog, Road to Endeavour at: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / S. Atkinson

May

The intensified effort to recover Spirit continued to the last week in May. But after a year of listening, and more than 1300 electronic "nudges" sent through the Deep Space Network X-band, and the ultra-high frequency (UHF) relay communications systems with the Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, after numerous recent attempts to reach the rover trough the auxiliary solid-state power amplifier (SSPA) – and not so much as a single beep from Gusev Crater, NASA Headquarters decided Spirit's mission was over.

Maybe her solar arrays were just too thick with dust. "Dust is always accumulating, because Mars is a dusty place," Nelson reminded. If it weren't for cleaning events, both rovers would have died a long time ago. Maybe a wire somewhere broke. Maybe Spirit just got too cold and a lot of things gave out. Maybe the thousands of thermal cyclings finally took their toll. No one in this lifetime will likely ever know for sure.

In any case, NASA and JPL officials decided to conclude the official recovery effort with the last of the intensified strategy sequences already prepared and scheduled to be sent early May 25, 2011 Pacific Time. Despite plans for a televised press event at NASA headquarters in early June to announce Spirit's decommissioning, the official declaration of the end came abruptly, even before those last signals were sent, in an impromptu press teleconference on May 24th. It marked, however unceremoniously, the end of one of the greatest planetary exploration stories ever told.

"We lost contact with Spirit better than a year ago. We've been trying everything we can, but the prospects of regaining contact with the vehicle have been diminishing gradually and steadily with time," a resigned Squyres said later.

Despite an admitted emotional attachment to the little golf-cart-sized robot field geologist, what surprised team members more than anything, the said, was how good they felt in spite of their grief. " I really expected to be feeling sad, and at some point I do expect to be feeling very sad about this, but my immediate reaction is dominated by pride instead. Spirit accomplished a great deal, a tremendous amount in an environment that was much harsher than her sister's, and she fought so hard for so long that I really just kind of want to say, "Job well done, baby."

Spirit at Troy

Spirit at TroySpirit appears tiny on the shoulder of Home Plate in this artistic image created by MER poemster artist Glen Nagle. It shows the rover's position where she became bogged down at Troy. The panorama was taken by the rover back on her Sol 743, as she descended from Husband Hill toward Home Plate. Home Plate is the plateau occupying the center of the image; the rover is in the valley to its right.NASA declared Spirit's mission over in May 2011 after more than a year sp[ent trying to recover the rover. Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / G. Nagle

Spirit was the first rover to climb a Martian hill, to snap a picture of the legendary dust devils, to inadvertently use her adversity to make one of the mission's greatest scientist discoveries. All told, she put 7730.50 meters (7.730 kilometers, 4.803 miles) on her odometer, sent home more than 124,000 images from the surface, and worked for more than six Earth years (more than three Mars years). In the process, as Callas has often pointed out Spirit sent Mars home. "Spirit made Mars familiar. She put Mars into our neighborhood.”

And, as Squyres had always hoped, the little rover has left a legacy in the inspiration she gave to young people of several generations. The inspired ones turn up everywhere, and in some cases, these students have never known a time when there weren't rovers on Mars.

Thus, there was grieving. Spirit always was and will be, after all, a team member, the robot that was up there on Mars doing our bidding. “We have come to feel very deeply for these rovers," acknowledged Squyres. "This sadness is expected." Squyres reflected. “

Endeavour hills getting closer

Endeavour hills getting closerPictured here are Tribulation hills that lie to the south of Cape York. A range of hills forms the western rim of Endeavour. Opportunity is headed to Spirit Point at the south end of Cape York, still out of view from the rover's location this month.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / processed, colorized by S. Atkinson

As NASA transitioned the mission to a single rover operation, the MER team members moved on and Opportunity moved on too, blasting across the plains of Meridiani in May, slowing only to take a brisk tour of a small field of young impact craters, and ending the month just 3.5 kilometers (2 miles) from the much-anticipated Endeavour Crater.

Opportunity'sright front wheel continued to show modestly elevated motor currents, something the engineers watch daily, "like a hawk,” Callas said. This is the wheel that has the failed steering actuator (which causes Opportunity’s right front wheel to be toed by about 7 degrees), and is also the same wheel that failed some six Earth years ago on Spirit. Team Opportunity has successfully mitigated the "hot" wheel issue by having the rover warm up the wheel before driving, and then driving backward most of the time, with scheduled rest stops in between drives.

Still the rover's prime directive – indeed, its mantra since leaving Victoria Crater in September 2008 – “Drive, drive, drive" – intensified as May turned to June. Endeavour was really within reach now. “Look at the map and do the math," Squyres enthused. Although Squyres declined to make any predictions, the rover was now weeks, not months or years away.

June

Despite – or maybe because the last of the pre-programmed recovery signals that Mars Odyssey sent to Spirit on June 8th went unanswered, bringing an anti-climactic final curtain down on her twin – Opportunity kicked things up a notch again in June, setting more records, including a new longest backward drive ever by a rover on Mars, and putting more than a kilometer behind it in a matter of two weeks. "We're thrilled," said Ashley Stroupe, a MER rover driver who recently had transitioned from Spirit to Opportunity.

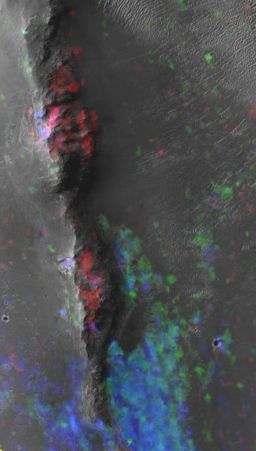

Mineral map of Endeavour's western rim

Mineral map of Endeavour's western rimCRISM spectral maps of Endeavour's western rim show smectite (red) associated with the upraised rim rocks and hydrated sulfate minerals (blue) associated with the lower-elevation sedimentary fill. The image is roughly 1.5 kilometers wide.Credit: NASA / JPL / UA / JHUAPL

No kidding. In addition to having to drive backwards because of that “hot” right front wheel, Opportunity suffered a broken shoulder joint a few years back, and that means she has to leave her robotic arm slightly deployed, hanging like a fisherman would position his fishing pole out the front, which is now the rear. Anyway, the rover now drives like that. Most of her equipment is in good shape, except for her rock composition detecting miniature thermal emission spectrometer (Mini-TES), which was declared lost this year.

“There are specific aches and pains we've managed to work around, but Opportunity has been an incredibly robust and productive rover this month," reported Nelson. “This vehicle is operating almost as well as she did on landing.”

Well, if mileage is any indicator – yeah. Opportunity all but "burned up" the Meridiani plains in June as she raced ever southward. “We’re driving as fast as we can to Endeavour Crater,” confirmed Squyres. Remember, on a good day, even back when she was brand sparkling new, Opportunity's top speed is about 1 meter a minute, mind you, so all things in perspective. But by the end of the month, the rover was just 2-kilometers (1.24-miles) away from the huge, 22-kilometer (14-mile) diameter crater.

Endeavour and its western rim exposes outcrops that harbor clues of environments much older than any the rover has found to date. Being the biggest hole in the ground that Opportunity's had the opportunity to check out, this crater promises to take the rover and the MER science team farther back in Martian time than any other site on this expedition … back to that time, billions and billions of years ago, when Mars was warm and wet and rich with habitats from which life could emerge and thrive.

Better still, the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) instrument (for which Arvidson is leader of the Surface Geology subteam) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) had detected phyllosilicates, specifically iron-magnesium smectite, a family of clay minerals that form in near neutral water along Endeavour's rim. Phyllosilicates are “planetary gold." If Opportunity can find some of this smectite, then it will have found the best evidence yet found that an alkaline water once pooled or flowed on Mars, and a potential past habitat that would be much more suitable for the emergence of life than any past environment it had found previously.

Since finding phyllosilicates is one of the objectives given to NASA's next-gen rover, Curiosity, Opportunity's discovery of smectite would be another stellar accomplishment to add to the MER mission’s long list of achievements in planetary exploration and another feather in this rover's mast, which now metaphorically resembles the headdress of a Lakota chief. Past that, the discovery would give Opportunity the race, and effectively challenge the new rover soon to be on the block.

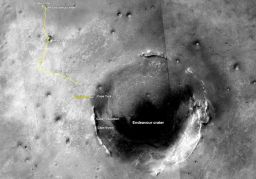

Eagle to Endeavour

Eagle to EndeavourThe yellow line on this map shows where Opportunity drove from the place where it landed in January 2004, inside Eagle crater (at the upper left end of the track) to a point about 2.2 miles (3.5 kilometers) away from reaching the rim of Endeavour crater. In honor of Opportunity's rover twin, the team has chosen Spirit Point as the informal name for the site on Endeavour's rim targeted for Opportunity's arrival at the big crater. Spirit, which worked halfway around Mars from Opportunity for more than six years, ceased communication in March 2010.The base map is a mosaic of images from the Context Camera on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. It is used by MER team member Larry Crumpler of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Albuquerque, for showing the regional context of the rover's traverse.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / MSSS

With Endeavour clearly in view the engineers were amped and the scientists were over over the Moon, the MER Update reported in June. "I'm close to really excited," admitted Arvidson, the team’s resident stoic Swede.

July

Opportunity sailed from June right into July, as if propelled by an invisible wind, as if nothing could stop her. The idea of getting rover wheels onto ancient Noachian crust "charged up" everybody, Squyres said. Including, it seemed, the rover.

Opportunity seemed to pull out all the stops in July, driving backward as fast as possible and putting nearly a mile in the rear view mirror. "We're almost there," Squyres marveled then. "We are close enough to smell it."

The MERs were designed and built to survive and work on Mars, noted John Wright, one of the rover planners. That Opportunity has gotten this far he didn't find too surprising. "These rovers will do a lot more than we give them credit for," he assured.

The only pause in July came during interludes mid-month when team members gathered in Pasadena for the MER annual meeting, and to say 'good-bye' and 'thank you' privately and publicly, to Spirit, first over dinner together at Caltech's Athenaeum [where Einstein briefly lived], and then following day before a crowd of hundreds of invited guests at JPL.

A dozen team members and a couple of agency officials offered stories and anecdotes and memories during the Spirit Celebration at JPL that reviewed Spirit's achievements in words, pictures, and videos. They represented some 4000 individuals, each of who made some contribution. Hindsight is 20/20, they say. In a business where every part matters, where there is usually little to zero margin for error, uniting that many engineers and scientists for one common vision may well be one of Spirit's most enduring successes. [Ed. note: A tribute to Spirit will appear as an MER Special Update later this month.]

Opportunity on Endeavour's rim (detail)

Opportunity on Endeavour's rim (detail)This HiRISE image, taken on September 10, 2011, shows Opportunity sitting atop some light-toned outcrops on the rim of Endeavour Crater, near a smaller crater informally named Odyssey. Opportunity travelled nearly three years to reach this rim. Credit: NASA / JPL / UA

Up on Mars, Opportunity took a day of rest, after putting another 124 meters behind her. Then as August peaked over the horizon, on her Sol 2673 (August 1, 2011), taking care of routine engineering and science business, and the rover took care of the usual business, and used her AEGIS software to look for interesting outcrops.prepared for the last stretch into Endeavour.

August

On August 9th, after a journey that took 1047 Martian days – nearly three Earth years – Opportunity crossed the geologic boundary from the plains of Meridiani Planum into the rim area of Endeavour Crater, pulling into Spirit Point and the rock-strewn southern tip of Cape York to complete what turned out to be a 21.5-kilometer (13.35-mile) journey from Victoria Crater.

As luck and scheduling would have it, veteran rover driver Frank Hartman, who has been with MER since the beginning, was 'at the wheel,’ metaphorically speaking. “It's one of those events that allows you to look back and reflect a little,” he said.

Back when Opportunity landed at Eagle Crater in January 2004, Endeavour wasn’t even an impossible dream destination. But since then, the rover had driven 33.5 kilometers (20.8 miles) – impressive to say the least, given that the rovers only had to drive 600 meters between them to complete its original primary objective. “It's just amazing to be here after setting out almost three years ago,” Squyres told the MER Update "It feels like a new mission all over again.”

September

Tisdale 2

Tisdale 2This close-up of Tisdale 2, the first rock Opportunity examined in detail on the rim of Endeavour crater, has textures and composition unlike any rock the rover has ever examined. Its characteristics are consistent with the rock being a breccia, a type of rock in which broken fragments of older rocks are fused together. Tisdale2 is about 30 centimeters (12 inches) tall. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

In September, that feeling became reality. Less than three weeks after arriving at Endeavour Crater, Opportunity found a rock that was "different from anything else it had seen on Mars," said Squyres. "I remember vividly press briefings [in 2004] where we presented new results that raised more questions than they answered," Squyres said. "And we have some strange stuff going on here. You're coming along with us to a brand new field site.”

Apparently excavated by an impact that dug a small crater the size of a tennis court into Endeavour's rim, the rock, dubbed Tisdale 2, is flat-topped, about the size of a footstool, and boasts so much zinc it’s got the scientists giddily scratching their heads. “I am totally excited,” offered Arvidson “This really is a brand new mission.”

Opportunity roved on to begin making detailed measurements of the chemicals and minerals it could find in another chunk of bedrock, christened Chester Lake, on the inboard side of Cape York. After looking at the rock in its natural state, it brushed the surface coating off and looked at it again, then ground into with its rock abrasion tool (RAT) and took another look. In contrast to Tisdale2, Chester Lake offered the scientists no hint of water alteration. "It looks like an impact breccia," concluded Squyres and Arvidson. In other words, the rover had found a rock composed of broken fragments of minerals or rock formed from the impact and cemented together by a fine-grained matrix.

10th Anniversary of 9/11 on Mars

10th Anniversary of 9/11 on MarsThis picture shows an American flag on metal recovered from the site of the World Trade Center towers after their destruction on September 11, 2001. The aluminum component bearing the image of the flag serves as the cable guard of the rock abrasion tool (RAT) built and operated by Honeybee Robotics of New York. Opportunity took the component images that went into this picture on Mars on the 10th anniversary of the attacks on the towers, September 11, 2011, using its stereo panoramic cameras to record several exposures during its Sol 2713. Those images were then combined into this one picture. The picture is approximate true Martian color, or color as the human eye would see it on Mars. The black-and-white portion of the view, providing context, comes from the rover's navigation camera.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / ASU

On Opportunity's Sol 2713 – September 11, 2011 down on Earth, the 10th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York – the rover took a color photograph of the American flag fixed on the aluminum plate that covers the cabling for the RAT, located at the end of the rover's arm.

These aluminum plates were actually recovered from the New York World Trade Center in the days after the tragedy in 2001, affixed in perpetuity on Opportunity and on Spirit and taken to Mars … in peace for all humankind.

October

Opportunity roved on in October, driving alongside the rim of Endeavour Crater toward the northern end of Cape York, in search of anything interesting and places to hunker down for winter.

As it continued ever onward, the robot field geologist set new robot records, helped the Mars Exploration Rover mission take home another award, and, in the 11th bewitching hour as All Hallow’s Eve descended on Earth, sent home a postcard of something the science team had been hoping to find before the brutal cold of winter arrived, a feature the team immediately dubbed Homestake. And it even looked kind of spooky.

With the difficulties presented in finding the smectite clay minerals – which in this area of Endeavour’s rim were detected in the inboard side at Cape York – the scientists decided to try to find one of the light-toned veins they'd noticed running through the Bench when the rover first drove across it in August. The Bench is the smooth apron that surrounds the ancient Noachian terrain. “The veins are easy features to spot,” Squyres said then, "while the smectites would have been more of a fishing expedition."

Rich Morris

Rich MorrisJohn Richard "Rich" Morris

Credit: The Morris Family

Homestake proved to be “a real triumph of geology,” as Squyres put it. “We drew a mental geologic map and found a unit where those veins had been, traced it all the way up to the northern end of Cape York … headed to the northwest, intersected that unit and – bingo!"

The triumph of Opportunity's discovery was tempered by the tragic news that the MER team had lost two of their own. JPL engineer John Richard “Rich” Morris, who had held several positions on the MER team, including that of mission manager, passed away on Tuesday, October 18th at his home in Altadena, California as reported in the November MER Update. He was just 37.

Just 10 days later, on October 27th, MER science team member Ron Greeley, the Regents Professor in the School of Earth & Space Exploration at Arizona State University (ASU), and Director of the NASA Regional Planetary Image Facility, passed away unexpectedly at his home in Tempe, Arizona. He was 72. A MER science team member and science team member of the European Space Agency’s Mars Express mission, Greeley had been involved in lunar and planetary studies since 1967, and was a beloved planetary scientist. “We miss Ron’s wisdom and guidance on the rover team,” says Planetary Society President Jim Bell, lead scientist for the Pancam on the rover, ASU professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration. [See October MER Update for previous coverage.]

MER science team member Dr. Ron Greeley

MER science team member Dr. Ron GreeleyDr. Ronald Greeley -- the Regents Professor in the School of Earth & Space Exploration at Arizona State University, and Director of the NASA Regional Planetary Image Facility --was a beloved planetary scientist and geologist, involved in space exploration since 1967. He passed away unexpectedly on Oct. 27, in Tempe, Arizona.Credit: Tom Story / Arizona State University

November

As Opportunity “crunched” Homestake apart in November and chalked up yet another “exciting” textbook discovery, NASA’s next generation, $2.5 billion rover Curiosity lifted off from Cape Canaveral on an 8.5-month flight to Mars and commandeered the news headlines around the world.

The Mars Exploration Rover pressed on, continuing north at Cape York on a mission to check out two chosen sites where it might spend its fifth Martian winter. "There's a southern candidate and a northern candidate winter haven within about 20 meters of one another, and they both have slopes of 10 to 20 degrees north," said Arvidson, who is the science lead for Opportunity's winter campaign.

Just before Thanksgiving, the rover arrived at the southern candidate site and settled in for the long holiday weekend at the location, which was quickly dubbed Turkey Haven, not surprisingly for most Americans. There, the rover examined another Noachian Period rock the team named Transvaal. It ended up looking very similar to Chester Lake, according to both Squyres and Arvidson, or in other words an impact breccia, leading them to hypothesize that the whole of Shoemaker Ridge is breccia formed from whatever created Endeavour.

November was “pretty much business as usual,” offered Nelson. “Opportunity is driving fine." The rover is producing less power though, as expected this time of year. "We haven't had any cleaning events and the dust factor continues to deteriorate, which means the rover is getting less sunlight and producing less energy," confirmed Callas. Still, all things considered, the rover's prospects as it nears its 8th anniversary of exploring Mars are bright.

December

As December dawned at Meridian Planum, Opportunity was exploring the north end of Cape York and the second candidate for a winter haven. The rover moved into December on her Sol 2792 (December 1, 2011) with a backward bump of about 2.7 meters (9 feet) to get a better view of Saddleback and increase her tilt toward the Sun, from 6 degrees to 9 degrees. Three sols later, 2795 (December 4, 2011), the rover bumped further to approach other targets on Saddleback, which science team members wanted the rover to check out with her scientific instruments on her instrument deployment device (IDD) or robotic arm. The rover finished out the first week of the month on Sol 2798 (December 7, 2011) investigating one of those targets up close.

Homestake

HomestakeOpportunity took this picture of Homestake, the striking vein running through bedrock, and Stuart Atkinson, of UMSF.com, the MER poet dude and a frequent image contributor to the MER Update, processed it here in rich color. "This is different than anything we've ever seen with either rover," said MER PI Steve Squyres last month. On Dec. 7, at the American Geophysical Union fall meeting, he and Ray Arvidson will announce what Homestake is harboring.Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / S. Atkinson

On December 7th, during a press conference at the American Geophysical Union (AGU) fall meeting being held in San Francisco, Squyres, Arvidson, and other members of the MER team announced that Opportunity had found gypsum in Homestake. "This is the single most powerful piece of evidence that Opportunity has found for liquid water on Mars," Squyres said.

Intriguingly, Opportunity hadn’t seen anything like Homestake anywhere around the 33 kilometers (20 miles) of crater-pocked plains that it explored for 90 months before it reached Endeavour, nor in the higher ground of Endeavour's rim. Rather, it found Homestake and other veins like it only in the Bench area that surrounds part of the rim of Endeavour, a zone where the sulfate-rich sedimentary bedrock of the plains meets older, volcanic bedrock of the crater's edge.

Opportunity route map

Opportunity route mapThis Opportunity route map was porduced by Eduardo Tesheiner, of UnmannedSpaceflight.com, and created from images taken by cameras onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. It shows the rover's travel to its Sol 2790 (Nov. 29, 2011) and its last drive of the month. The rover officially reached the rim of Endeavour Crater on Aug. 9, 2011 and is currently scouting locations in which to seek haven during the worst of this Martian winter.Credit: Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / UA / MSSS / E. Tesheiner

About the width of a human thumb, 1 to 2 centimeters (0.4 to 0.8 inch), 40 to 50 centimeters (16 to 20 inches) long, Homestake protrudes slightly higher than the bedrock on either side of it. In November, Opportunity used its microscopic imager (MI) and alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS), as well as multiple filters of the panoramic camera (Pancam) on its mast to examine the vein. "As far as we can tell that vein is almost pure calcium and sulfur," Arvidson told the MER Update. "And it's water bearing. The best bet is that it's gypsum, which is calcium sulfate with 2 waters in the unit cell," he explained.

"This is the first time that we have found anything like this that's really in situ, in place," Squyres expounded. "All of the sulfates that we have found, all the gypsum that's been found elsewhere is stuff that was transported from where it was originally deposited. This is where it was deposited."

The veins are there, Arvidson proffered, "because it's basically a boundary layer effect, where we're looking at the sedimentary unit that is sitting right on the Noachian outcrop. It's another piece of the puzzle of the chemistry of rising groundwater."

There is, however, more work to be done. "This is an emerging story," Squyres said.

As the second week of December progressed, Opportunity managed to position herself at a tilt of about 15 degrees, with her solar arrays pointed north, and continued her close-up investigation of Saddleback. On Sol 2800 (December 9, 2011), the rover conducted a set of compositional investigations on Boesmankop, named for the greenstone belt in southern Africa, collecting microscopic imager (MI) pictures and following that task by placing her alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) on the target for an overnight integration.

On Sol 2801 (December 10, 2011), Opportunity used her rock abrasion tool (RAT) to brush Boesmankop, and then collected another MI mosaic and a Pancam image, and then put her APXS on the target for another overnight integration, this time on the brushed surface.

Spotting an interesting rock clast on the outcrop, dubbed Komati, the rover performed a small 9-degree counter-clockwise turn on Sol 2803 (December 12, 2011) to better position herself to look at it with the instruments on her IDD. The rover began, with the MI as usual, and followed that picture-taking session with an up-close look at the clast's composition with the APXS.

Komati

KomatiWhen the MER scientists saw this intriguing little rock clast, they dubbed it Komati and directed Opportunity to check it out. So far, the data the rover sent home indicates that it, like Saddleback, Transvaal, and and Chester Lake before it, is impact breccia.

Credit: NAA / JPL-Caltech / S. Atkinson

Opportunity continued collecting APXS data into the third week of December. On Sol 2808 (December 17, 2011), the rover then initiated a rotation drive to move in closer to a different target. Suddenly, the right-front wheel experienced high enough electrical currents that the rover tripped a fault response and stopped the drive.

The telemetry the rover sent home suggested the elevated current was due to the wheel's orientation with respect to the terrain and not an actuator or motor failure. To verify this, the engineers commanded Opportunity to perform diagnostic tests on Sol 2810 (December 20, 2011), which indicated the actuator is in good health.

In addition, the team was able to model exactly why that drive tripped the fault with ARTEMIS, "the computer modeling program Arvidson and other have been working on. “It alleviated some concern as to whether or not one of the wheels got hung up when the vehicle was on that very rough tilted parking lot that you find on Saddleback," said Arvidson. "The rover experienced this kind of stick slip motion as the cleats went over the clast, and with the right front wheel in the down position, it just faulted out because the currents became too high, because [that wheel] was trying to do all the work.”

As the holidays lit up the Earth in the fourth week of December, Opportunity moved slightly, 3 centimeters (1.2 inches) in the opposite direction on her Sol 2812 (December 22, 2011) to clear her right front wheel from any potential obstacles that may have hooked the wheel. Successful, this bump further indicated that the right front wheel’s actuator was fine, pointing to the terrain as the cause for the high current.

On Sol 2816 (December 26, 2011), Opportunity performed a 0.2-meter (8-inch) diagnostic backward drive, maneuvering into its winter position, and maintaining its 15-degree northerly tilt as it began to conduct more contact science. "What we’re seeing I think is the rock that holds up Cape York and it’s probably an impact breccia and it’s the Shoemaker Formation," said Arvidson.

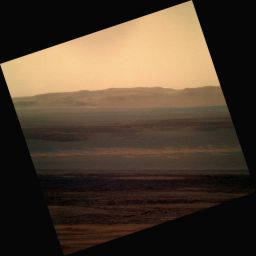

A view to the east

A view to the eastOpportunity took this image with her Pancam this month, December 2011. It shows the view the rover has to the hills on Endeavour's eastern side. It would take years to drive over there, so the rover is not likely to ever get the chance to explore over there. But everyone agrees, there's plenty of stuff on this side of the crater to keep the rover busy for months, even years to come. For more of Atkinson's work, visit: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/

Credit: NASA / JPL / Cornell / S. Atkinson

“We don’t have the APXS data [on Amboy] down [on Earth] yet, but the nearby targets, Boesmankop and Komati, look to the APXS very similar to Chester Lake, which means this really is the dominant rock type of Cape York," Squyres continued. "We saw this stuff way down at the south and here we are at the north end, and so we are seeing essentially the same composition. There is one dominant rock type here and this is it. That’s why it’s so important to characterize Saddleback as best we can. We’ve done a good job on with Pancam, MI, and APXS, and now we’re going to find out what it looks like to the Mössbauer.”

“The plan that we’re implementing right now – the one for the next 3 sols starting with Sol 2821 (December 31, 2011) – is a 3-sol plan that kicks off the Greeley Pan, the Mössbauer on Amboy, and radio science and so those are all beginning now,” informed Squyres.

Opportunity’s priorities are in place. “The radio science experiment will be the first priority, and the second priority will be Mössbauer data to get at the iron mineralogy of the Shoemaker Formation, and then the third priority is to get a beautiful Pancam panorama of Greeley Haven,” said Arvidson. “If it turns out that after 40-60 hours the Mössbauer data looks really neat then we’ll probably continue the integration, go into the winter low time, and then come out the other side and get even more hours.”

For each of the experiments in its winter science campaign, it's best if Opportunity stays parked in place, although the rover can move a little, up to a meter, Arvidson pointed out, “as long as we track locations within centimeters using visual odometry."

Despite being in a good position for the season, this is Opportunity's fifth Martian winter, not a time for the faint of robot heart. “There are always concerns,” said Callas. “We have to be vigilant against deteriorations in dust factor and increases in atmospheric opacity during this time and of course colder environments."

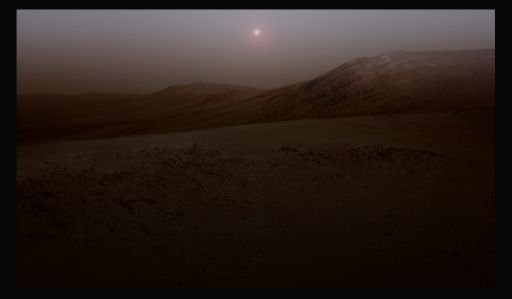

Endeavour at Twilight

Endeavour at TwilightThis is art, as in it's not really real. Stuart Atkinson of UMSF.com worked some of his pictorial magic and rendered this " Opportunity imagined" view of Endeavour at twilight. For more of Atkinson's work, visit: http://roadtoendeavour.wordpress.com/

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Cornell / S. Atkinson

Right now though Opportunity is as high as she's been in a long, long time, physically and other wise, and sitting pretty after an incredibly productive and successful year. "If I had to rank years for Opportunity in order of the importance and significance of the science that’s come out of it," Squyres said, reflecting on 2011, "I would probably put 2004 first and 2011 second."

The low point of the year was of course the loss of Spirit. "But," Squyres resolved: "She died an honorable death. And we all knew this had to happen sometime."

Only time will tell how long Opportunity will be at Greeley Haven. “We’ll see how it goes,” said Squyres. "We’ll keep an eye on the power, and we’ll keep an eye on the dust in the sky and the dust on the arrays, and we’ll move away when it’s safe to do so. Not before and not after.”

Support our core enterprises

Your support powers our mission to explore worlds, find life, and defend Earth. You make all the difference when you make a gift. Give today!

Donate

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth