At a Glance

- The Fiber-optic Improved Next generation Doppler Search (FINDS) project was an effort to improve exoplanet detection techniques using ground-based telescopes.

- The Planetary Society's members provided $45,000 to a team led by Dr. Debra Fischer at Yale University to demonstrate the feasibility of this system in observatories in California and Hawaii.

- The project improved a key observational metric helpful for detecting exoplanets by a factor of 2 and reduced data error rates by 30%.

In 2009, The Planetary Society helped a group of exoplanet hunters improve the way we search for other worlds.

Telescope spectrographs can detect the tiny wobbles of other stars, which indicate the presence of unseen planets. Wobbles created by Jupiter-like planets have speeds of several meters per second, but Earth-like planets might only shift their star by 10 centimeters per second.

It’s a tall order for spectrographs to look at stars thousands of light years away and detect motions slower than the pace of a person walking down the street. High-resolution spectrographs have lowered the exoplanet detection threshold to about a meter per second. But these instruments come with big price tags.

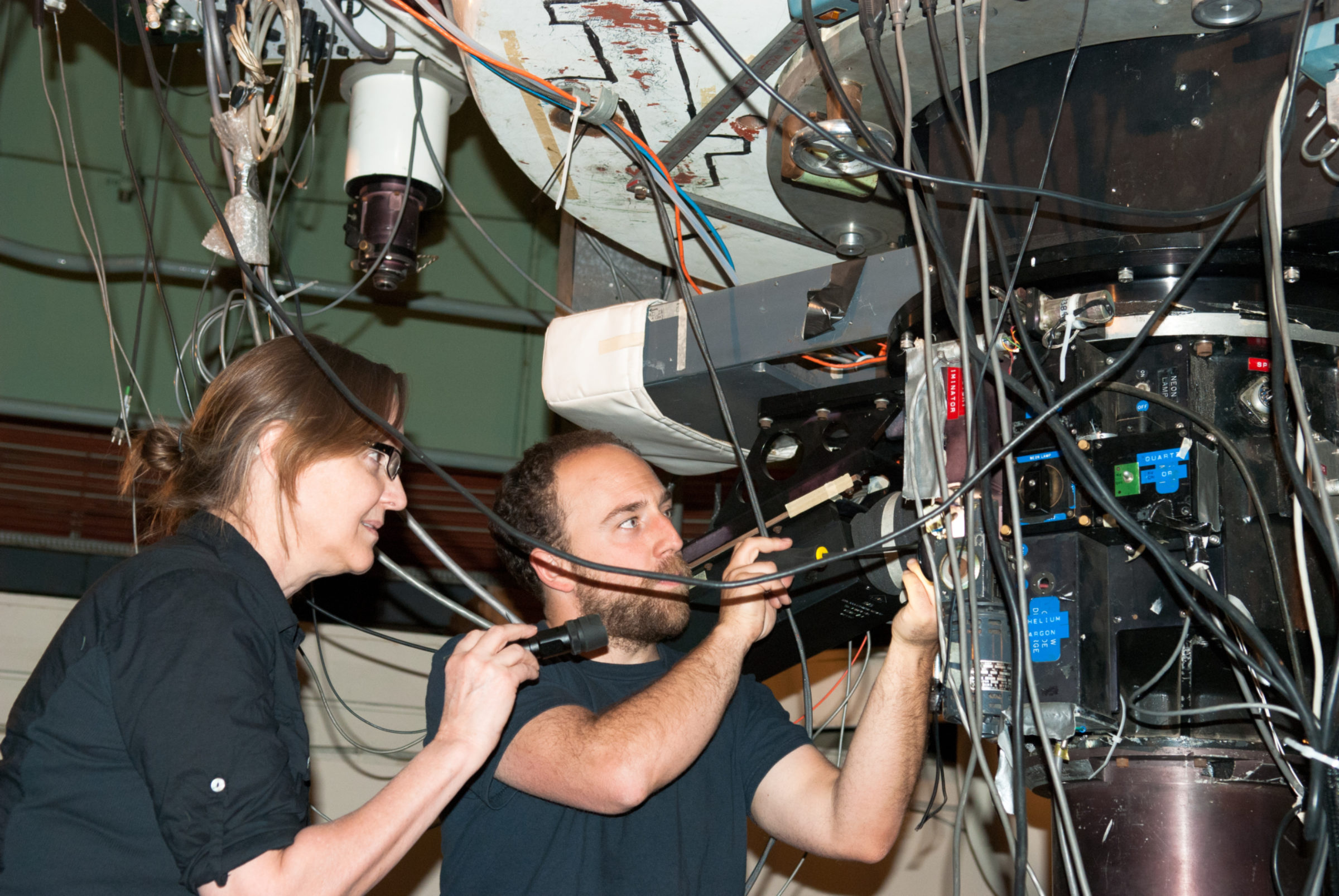

At Yale University, a team led by Debra Fischer, set out to improve existing spectrograph technologies. Spurred by a $45,000 grant from The Planetary Society, the team built FINDS (Fiber-optic Improved Next generation Doppler Search) Exo-Earths, a spectrograph add-on device.

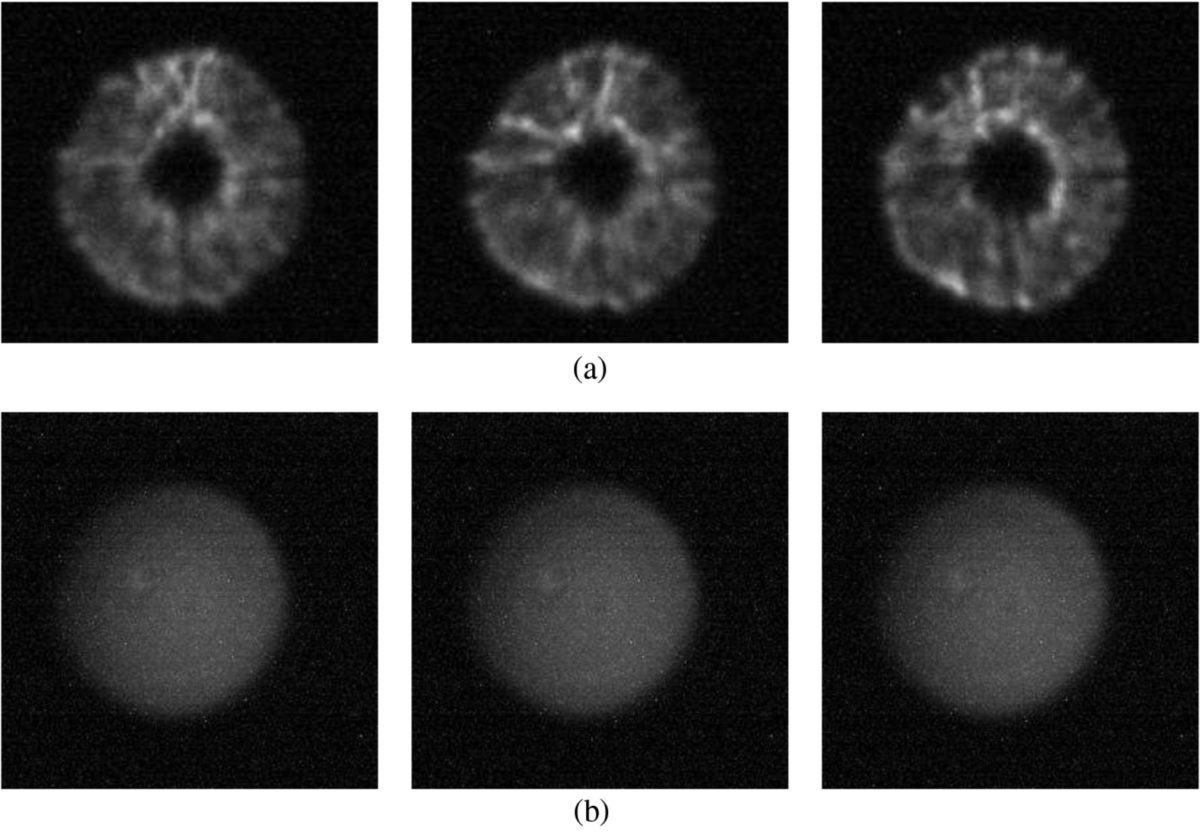

A telescope collects starlight and focuses it on a lens that leads to a spectrometer. The light must be precisely focused at the center of the lens to obtain consistent, accurate measurements. This means a sudden gust of wind at the observatory or a vibration in the telescope’s guidance system can jiggle the starlight, causing data errors. One way to alleviate these errors is by sending the starlight through a fiber-optic cable. Fiber-optic cables have cores made of glass or plastic. Light entering the cable scatters, emerging into the spectrograph as an even cone. As a result, small telesccope variations won't have such a negative effect on the data. The tradeoff is that some of the starlight will be absorbed by the cable's insulation, but the net result should still be an improvement in resolution.

The FINDS prototype was a 2-by-1 foot box containing the fiber-optic cable and a system of mirrors and lenses. It was installed on the 3-meter telescope at Lick Observatory near San Jose, California, and saw first light in July 2009. The FINDS team, led by Fischer, measured stars with well-known wobble rates to check the system's performance. The results were promising: FINDS had reduced data errors by 30 percent, with a light loss of just 20 percent.

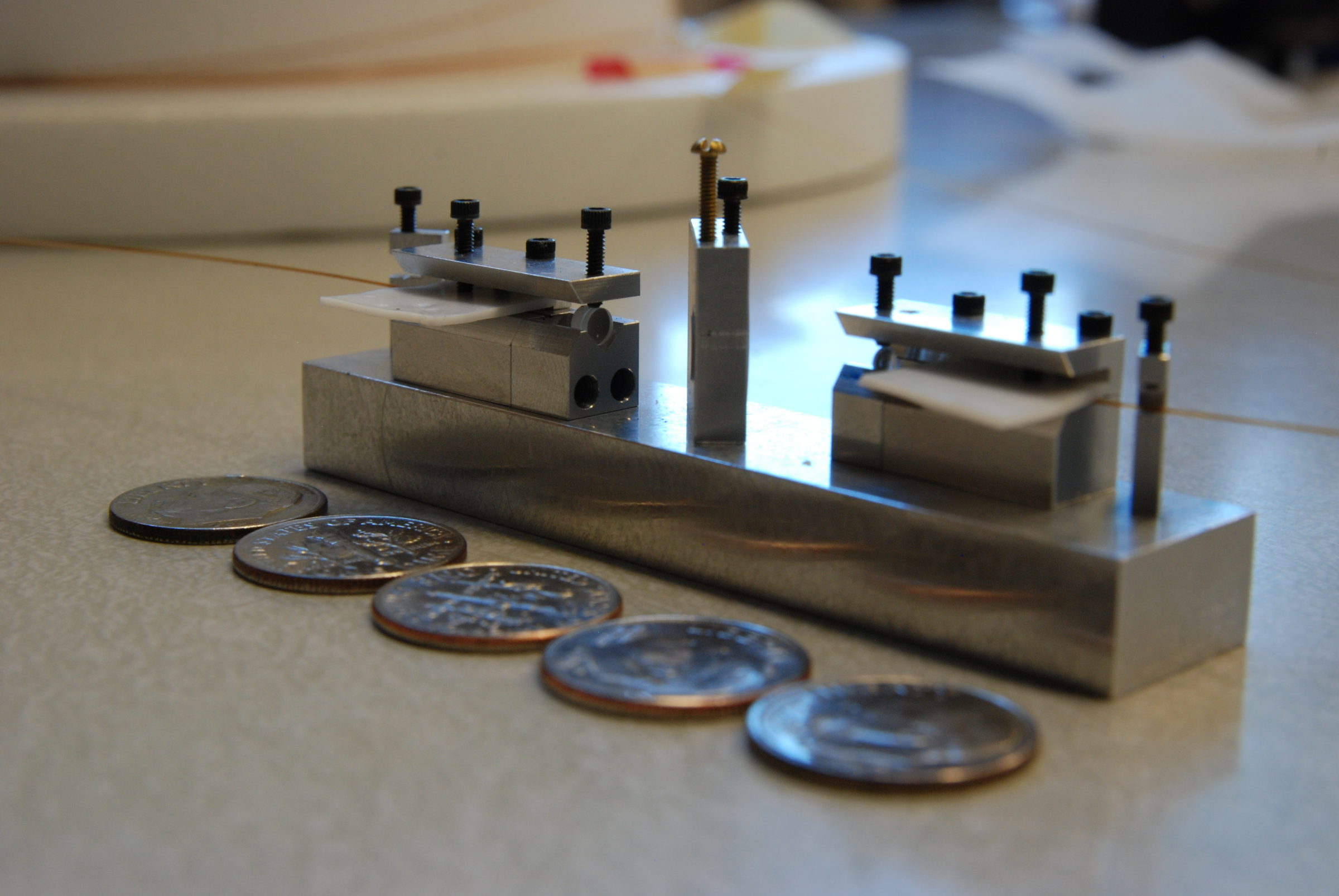

Fischer and Spronck built another version of FINDS for one of the

10-meter Keck Observatory telescopes in Hawaii. The telescope's design

could not accommodate the original 2-by-1 foot box, so Spronck built a

tiny 3-by-1 inch version of the technology, which was called Matchbox

FINDS.

FINDS showed that fiber-optic systems are an effective way to increase the spectral resolution of telescope spectrographs. Similar systems have been used by exoplanet hunters around the world.

The team published 2 peer-reviewed technical papers outlining their experiment and results:

As for Fischer's team, they next took the technology to the Southern Hemisphere to search for exoplanets around our nearest stellar neighbor, Alpha Centauri.

Our Exoplanets Projects

Since 2009, Planetary Society members have supported work by Debra Fischer, one of the world's top exoplanet researchers. These projects have greatly improved our ability to search for Earth-like exoplanets.

Explore Worlds

Explore Worlds Find Life

Find Life Defend Earth

Defend Earth